Abstract

Background

The importance of advance care planning (ACP) has been highlighted by the advent of life-threatening COVID-19. Anecdotal evidence suggests changes in implementation of policies and procedures is needed to support uptake of ACPs. We investigated the barriers and enablers of ACP in the COVID-19 context and identify recommendations to facilitate ACP, to inform future policy and practice.

Methods

We adopted the WHO recommendation of using rapid reviews for the production of actionable evidence for this study. We searched PUBMED from January 2020 to April 2021. All study designs including commentaries were included that focused on ACPs during COVID-19. Preprints/unpublished papers and Non-English language articles were excluded. Titles and abstracts were screened, full-texts were reviewed, and discrepancies resolved by discussion until consensus.

Results

From amongst 343 papers screened, 123 underwent full-text review. In total, 74 papers were included, comprising commentaries (39) and primary research studies covering cohorts, reviews, case studies, and cross-sectional designs (35). The various study types and settings such as hospitals, outpatient services, aged care and community indicated widespread interest in accelerating ACP documentation to facilitate management decisions and care which is unwanted/not aligned with goals. Enablers of ACP included targeted public awareness, availability of telehealth, easy access to online tools and adopting person-centered approach, respectful of patient autonomy and values. The emerging barriers were uncertainty regarding clinical outcomes, cultural and communication difficulties, barriers associated with legal and ethical considerations, infection control restrictions, lack of time, and limited resources and support systems.

Conclusion

The pandemic has provided opportunities for rapid implementation of ACP in creative ways to circumvent social distancing restrictions and high demand for health services. This review suggests the pandemic has provided some impetus to drive adaptable ACP conversations at individual, local, and international levels, affording an opportunity for longer term improvements in ACP practice and patient care. The enablers of ACP and the accelerated adoption evident here will hopefully continue to be part of everyday practice, with or without the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, advance care planning, policy, rapid review, barriers, enablers

1. Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) has come into sharp focus, particularly given the severe impacts of COVID-19 on those who are older and frailer or who have high levels of comorbidity, with high fatality in these groups, as well as the notable pandemic-associated strains on resources (1–4).

ACP is “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care”, aiming to ensure that medical care received is aligned with values and goals during serious and/or chronic illness (5).

Pre-pandemic, rates of ACP were not high. Population-based estimates of ACP prevalence in Australia hovered at 14% (6), while the US and UK had reported ACP engagement at ∼50%, and documentation at only 33% (7, 8). Rates of ACP pre-COVID-19 have been found to be lower in certain population subgroups, with lower rates, for example, amongst those of black, Asian and other “minority” American ethnicities, those identifying as LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer and Intersex), as well as amongst homeless persons, incarcerated persons and those with limited health literacy (9–14). On the other hand, pre-existing disability and female sex may increase ACP uptake (15).

The relevance of ACP in the context of a global pandemic, featuring a life-threatening disease, and over-stretched healthcare resources, may seem self-evident. Yet factors which may positively or negatively impact on ACP, and options to support ACP in the context of COVID-19, have not been fully explored.

In this context, we conducted a rapid review of the literature, both to investigate barriers and enablers of ACP in the COVID-19 context, and to identify recommendations to facilitate ACP, in order to inform future policy and practice.

2. Methods

Given the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we adopted the WHO recommendation of using rapid reviews for the production of actionable evidence (16).

2.1. Search strategy

We searched PUBMED for the period January 2020–April 2021, using MeSH terms “advance care planning”/“advance directive” plus “COVID-19”/“sars-CoV-2”. We screened reference lists of identified peer-reviewed articles with a focus on ACP during COVID-19.

2.1.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included papers which described or discussed ACP in the context of COVID-19, including rates (prevalence, incidence) of ACP, enablers and barriers, types of ACP, conduct of ACP, impact of the pandemic on ACP, and ACP-related outcomes. All study designs were eligible for inclusion, including commentaries and policy papers. Preprints, unpublished data and Non-English language articles were excluded.

2.2. Study selection

SY completed the literature search. MC and SY screened abstracts and reviewed all full texts. DNC, SY and MC reached consensus on all eligibility discrepancies. SY performed data extraction using a pre-defined table [author, publication year, country, study design, publication type, objectives, target population (if applicable), main conclusions]. MC cross-checked eligibility for inclusion. Given a rapid review, we did not formally conduct quality appraisal and risk-of-bias assessment.

2.3. Data synthesis and reporting

AS and EW reviewed data extraction tables and selected articles. Data were presented using simple descriptive statistics and tables complemented by a narrative synthesis.

3. Results

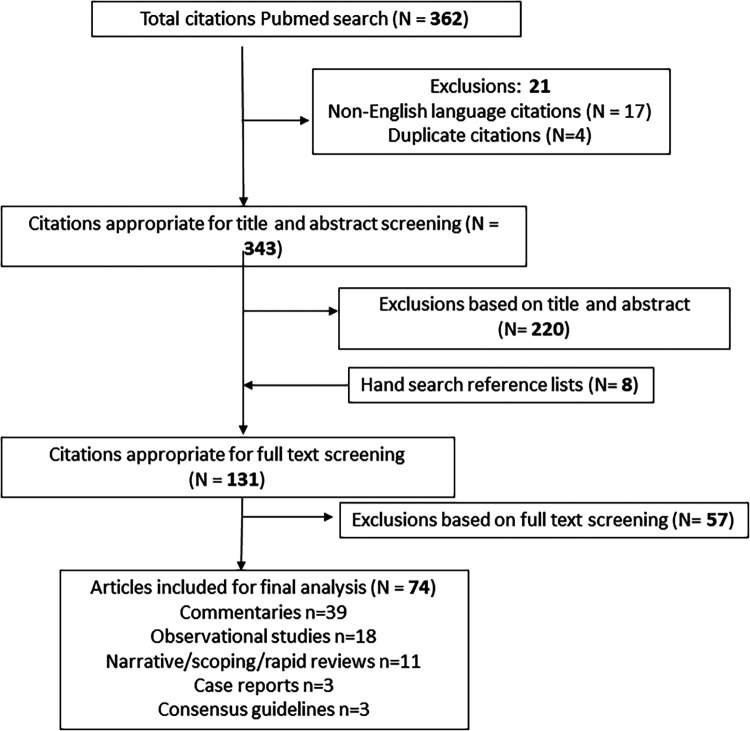

Overall, 343 studies were screened, with 123 full-text papers assessed for eligibility. After full-text screening, 74 were included, comprising commentaries (N = 39) or primary research studies (N = 35) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram depicting outcomes of search and screening, full-text reviews, exclusions and final included studies (N = 74).

Table 1 presents characteristics of included studies; Supplementary Material (online) gives further details. One-third (34%; n = 12/35) of the primary research studies focused on older adults, the remainder (66%; n = 23) targeting mixed age groups.

Table 1.

Article details for primary studies and commentaries.

| Primary research (n = 35) | Commentaries (n = 39) | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| United States of America (USA) | 23 | 26 |

| United Kingdom (UK) | 5 | 5 |

| India | 2 | 1 |

| Taiwan | 2 | 0 |

| Japan | 1 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 0 |

| South Africa | 1 | 1 |

| Australia | 0 | 2 |

| Canada | 0 | 1 |

| Italy | 0 | 1 |

| New Zealand (NZ) | 0 | 1 |

| Singapore | 0 | 1 |

| Study design | ||

| Commentaries | – | 39 |

| Cohort study—retrospective | 9 | |

| Cohort study—prospective | 8 | |

| Narrative review | 9 | |

| Consensus guidelines | 3 | |

| Rapid review | 1 | |

| Scoping review | 1 | |

| Case report | 2 | |

| Case series | 1 | |

| Cross-sectional study | 1 | |

| Study participants/focus | ||

| Patients + Aged Care Clients | 14 | |

| Policy makers/Guidelines/Ethics | 13 | |

| General ACP users in the community | 4 | |

| Clinicians only | 2 | |

| Mixed: clinicians + patients | 2 | |

There was significant overlap of key discussion points across commentaries and primary research studies, with themes and sub-themes identified as in Table 2. We explore these themes below.

Table 2.

Emerging themes and Sub-themes.

| Overarching themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Enablers of ACPs during COVID-19 |

|

| 2. Barriers to ACP during COVID-19 |

|

| 3. Recommendations for effective delivery of ACPs |

|

IT, information technology.

3.1. Enablers of ACPs during COVID-19

We identified several enablers of ACP from the included studies (Table 2).

3.1.1. Targeted public awareness and ACP engagement

Three studies noted that COVID-19 had increased awareness and importance of completing ACD and legal documentation relating to dying (17, 18); one commentator reported a 3.5-fold increase in ACP requests leading to a surge in palliative/supportive care services (19). Several commentaries highlighted that the media focus on COVID-19, with daily mortality statistics, and stories of dying alone, brought ACP to the forefront of public attention and increased demand for ACPs (19–21).

Primary research studies indicated increasing emphasis on ACP for vulnerable groups, such as older adults (22–33), and high-risk groups with pre-existing life-limiting and/or chronic conditions, such as HIV (34), cancer or organ failure (23, 29, 35), cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease (36) or severe mental illness (27). The evidence from these primary research studies was supported by perspectives in multiple commentaries (37–39).

Commentaries noted that in many aged and acute care settings, ACP was recommended for all patient (or resident) admissions (40, 41). Mooted options to increase uptake included sharing the ACP role with non-medical staff- social workers (42), nurses, or volunteers (19, 40, 43). Some primary research studies highlighted the value of opportunistic ACP discussions, in outpatient clinics (44, 45), prior to surgery (29) and/or at hospital admission.

3.1.2. Online platforms and telehealth programs facilitating ACP

Studies highlighted that clinicians, patients and families used on-line platforms and telehealth technology to facilitate ACP. Several primary research studies and commentaries reported on uptake of outreach telehealth services and/or tool development (23, 37, 46–51).

Telehealth enabled socially/geographically isolated COVID-19 patientsand carers to maintain contact with healthcare professionals (HCPs), engage in ACP conversations, seek psychological support and symptom management (23, 50–52). Telehealth was also described as potentially offering benefits for those in financial difficulties (51), facilitating family e-meetings (50, 53) and enabling carers to engage in virtual farewells with dying patients (37, 46–49, 54, 55). Some authors noted that patients seemed relaxed in their home and more willing to engage in ACP discussions (45).

Telehealth communication reportedly increased satisfaction rates for clinicians and families (50). Telehealth also aided ACP upskilling and education for clinicians. While clinician ability to initiate ACPs may have been unchanged, one study noted junior doctors' confidence decreased and anxiety in undertaking ACP rose, possibly a Kruger Dunning effect, where increasing skill acquisition may increase awareness of incompetence (45).

3.1.3. Easy access to online tools to guide ACP

Both primary research studies and commentaries noted accessible online/web-based ACP tools facilitated the development or adaption of COVID-specific end-of-life resources (17, 38, 56, 57). Existing tools such as Serious Illness Conversation guide (58) and online workshops (59, 60) were adapted to context. The available data suggested that online users were relatively young (mean 48 years) and largely female (67%) (18). A narrative review (57) also suggested that patient access to online health records might facilitate ACP documentation.

3.1.4. Adopting a person-centred approach and respecting patient autonomy and values

Proponents of ACP argued that effective end-of-life care planning leads to treatment which was better aligned with patient wishes, and that ACP by its nature respects human rights; ACP might also be associated with reduced depression and anxiety among bereaved relatives, prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and reduce therisk of dying alone (21, 40, 49).

Several narrative reviews suggested ACP should and can embrace a person-centred approach to care, involving “effective” or “adequate, sympathetic” communication (26), and needs to be culturally appropriate (32). ACP was considered an opportunity to respectpatients’ autonomy and reflect their values, choices, and preferences (24, 26, 29, 32).

Several studies highlighted the importance of identifying a patient's surrogate decision-maker in emergency situations (24, 61). A narrative review cautioned that firstly, critically ill COVID-19 patients may be ill-disposed to make their wishes known, and should not be pressured to make decisions based on conserving resources, and secondly, physicians should not pre-emptively ration or pressurise older adults to reconsider their ACP or resuscitation preferences due resource availability (24).

3.2. Barriers to ACP during COVID-19

3.2.1. Nature and novelty of the disease

Both primary research studies and commentaries identified that the rapid evolution of COVID-19 and uncertain clinical outcomes impeded ACP (46, 48, 62–67) A lack of prognostic clarity and varied treatment responses delayed ACP (66). Consensus guidelines, by the European Respiratory Society, reported that patients were too ill or anxious to participate in ACP, exacerbated by family absence. Rapid patient deterioration and/or clinical recovery added further complexity to timely discussions about ACPs and/or its currency (66).

3.2.2. Cultural and communication difficulties

A narrative review reported that ACP language can be complex, which may impair communication and lead to inaccurate representation of patient goals (57). Three studies noted that comprehension of ACP forms is influenced by health and literacy levels (44, 61, 66); this finding was supported by several commentaries (15, 19, 20, 58, 68, 69).

Both primary research studies and commentaries highlighted that ACP uptake is lower in ethnic minorities or lower SES groups (12, 54, 57, 70). A rapid review identified an inverse relationship between ACP and socioeconomic status (SES) (32); with lack of trust in the healthcare system amongst people from certain population sub-groups a point echoed in the commentaries (32, 71). Furthermore, a narrative review (57) identified that some minority groups may be more likely to appoint a formal “Next of Kin”, but less often document ACP, which may increase burden for such substitute decision makers. Commentary papers highlighted that minority groups may lack familiarity with the health system, and that this may be exacerbated by limited access and communication/language barriers (12, 19, 20, 58, 69, 72). Two narrative reviews highlighted potential cultural taboos on discussing death (57, 61), while a commentary from Sub-Saharan Africa- where ACP is not recognized- noted a focus on efforts to “preserve” life (73). These views may change across generations or time, and may not reflect individual preferences even within specific sociocultural groups, highlighting the importance of adopting an individualised, patient-centred approach to ACP.

Evidence suggested that families, and not just patients, may also experience communication difficulties. Several commentators reported on family values, perceptions and understandings that may differ from those of clinicians (54, 64, 70, 71, 74, 75). Clinicians were reminded that familial conflict may compound these differences (52), and that individual preferences can change over time (76, 77). A US retrospective cohort study reported that families were more likely to change life support preferences when they attended in-person bed-side meetings, due to improved understanding of the patient's condition/prognosis (53). Commentators also noted that not all population groups have ready access to, or facility with, communication technologies such as telehealth, and that these may in turn be affected by language or SES (12, 70).

Clinicians also experience impediments to communication, for example, lack of confidence in communicating bad news (57) and difficulties in making speech heard when wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) (61). Clinicians may experience difficulties initiating ACP discussions with patients/families (57, 61) or hold concerns surrounding topic sensitivity and family grief (44, 61, 66). For example, clinicians may delay end-of-life conversations, reluctant to “take away” hope when prognosis is uncertain. A European Taskforce suggested a constant review process will maintain alignment of ACP to the patient's evolving condition (66). Three primary research studies, and several commentaries, recommended the need for improved clinician ACP training and access to palliative care education (57, 61, 66). Mitigating strategies proposed included ACP integration at all training levels (20), the integration of specific frameworks such as VitalTalk (63) or the use of other conversation guides to ensure equitable access and goal-aligned management (39, 40, 73), and ACP upskilling for allied health providers (67).

3.2.3. Barriers associated with legal and ethical considerations

ACP laws and guidelines differ across countries and jurisdictions. Difficulties range from accessing lawyers (71), to differing legal terminology (15), to identifying who is entitled to initiate conversations. In some jurisdictions, only medical staff may initiate ACP conversations, with limited/no input from other multidisciplinary team members (67, 78). Mandated (over-)reliance on medical personnel may impede ACP- a large cohort study conducted in the US, found engaging social workers in ACP resulted in a 13% increase in patients nominating a medical POA (78). A Taiwanese study noted local legal obligations to have two witnesses and associated costs might impede ACP (79). A narrative review during the pandemic (26) identified seven documents that described core ACP issues to be discussed with nursing home residents: POA (Enduring Guardian equivalent), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), admission to hospital, intubation, non-invasive ventilation, fluids, antibiotics, etc. Supplementary Table S1 includes related resources, including a positionstatement by the American Geriatric Society (24).

A Canadian commentary argued that ACPs are less useful for COVID-19, lacking situational value, and difficulty fully informing individuals regarding treatment options, benefits and risks (65). They suggest patients should rather be asked about values, noting that ethical and legal issues are of serious concern during a pandemic. In particular, the ethics of blanket age- or residence-based protocols need to be considered when making advance care plans in the context of COVID. One commentary noted that some standardized protocols, e.g., in the UK, suggested that residential aged-care residents should not be admitted to hospitals (80). Such “one-size fits-all” approaches do not account for the uniqueness of individual presentations, prognosis and values (80). A US consensus guideline encouraged decision makers to focus on short-term outcomes and avoid age alone as a determinant of care. Other recommendations included avoiding ancillary criteria such as predicted long-term life expectancy (disadvantages older people), formation of triage committees and development of transparent resource-allocation strategies to facilitate appropriate ACP (24).

3.2.4. Restrictions due to COVID infection control procedures

Almost all studies identified that COVID-related restrictions impacted peoples' ability to connect with clinicians and access ACP-related support. Infection control protocols governing the spread of COVID (social distancing, mask-wearing) impacted on communication between patients, families and HCPs. This, in turn, decreased the uptake of ACPs, as outlined in primary research studies (66, 79, 81) and commentaries (41, 58). For example, a UK based cohort study identified a decline (from 75.4% to 50.6%) in Do-Not-Attempt-Cardiopulmonary-Resuscitation due to restricted family visiting (81). The use of PPE and restricted visiting were hurdles to building trust required for effective ACP discussions (45, 66). These findings were ratified overwhelmingly by the commentaries (19, 46, 49, 52, 54, 62, 64, 69, 72, 75, 76).

Lack of interpersonal access increased family and patient distrust/suspicion towards HCPs (70), and/or the healthcare system (41, 82). Isolation, travel restrictions, and visitor limitations made shared decision-making extremely difficult. This was seen from descriptions of the potentially-dying patient deprived of in-person visits (41, 46, 48, 52, 58, 62, 64, 69), to reported feelings of being abandoned by medical staff (76). Stigma surrounding COVID, reinforced by the infection control protocols, exacerbated these difficulties and created barriers to ACP (73).

3.2.5. Lack of time, resources and support systems

The enactment of ACP was identified as enabling fairer and more transparent resource allocation during periods of constraint, potentially reducing unnecessary life-sustaining treatments and streamlining the use of intensive care resources (1, 25, 35, 36). This was seen to alleviate the need for healthcare rationing, by avoiding aggressive treatment for those who do not want it, engaging patients in shared-decision making and avoiding blanket decisions based on age or comorbidity. Four commentaries noted that ACP also potentially reduced clinician exposure to avoidable infection and risk (e.g., with CPR), and assisted in planning for surges in healthcare demand (19, 21, 49, 77).

Nonetheless, the process of formulating ACP was recognised to be time intensive. Several primary research studies highlighted that clinicians are time poor, with little time for lengthy discussions or to develop clinician-patient relationships and trust (26, 35, 36, 57, 61). Numerous commentaries supported this finding (46, 58, 64, 67, 69, 70, 76). Commentators noted a lack of appropriate policies highlighting ACP's importance, a failure to prioritize it (46, 49, 54, 62, 63), and either poor or overly-cumbersome documentation, as well as failure to remunerate clinicians appropriately for time invested e.g., with dedicated billing codes (46).

Despite these barriers, requests for ACP have reportedly increased since the pandemic across varied settings: aged-care, terminal neurological patients, and prisons (17, 32, 38–41, 44, 82), with goals of care discussions ranging from 36% (53) to a 3.5-fold increase from baseline (19).

3.2.5.1. Recommendations for effective ACP delivery

The available evidence highlighted a number of recommendations to facilitate effective ACP delivery (Table 2).

3.3.1. Appropriate ACP design and structure

Various commentators suggested a need to develop or adapt tools specifically to the COVID context (17, 38), and, given the emotional impact of the diagnosis, to deliver small chunks of information at a time (15, 42, 63, 75). Three editorials suggested that current ACP tools are targeted towards non-communicable chronic illnesses rather than the COVID experience (52, 64, 70), and thus may require adaptation to best serve the COVID-19 context. Other authors provided specific ACP tools, approaches or frameworks to guide clinicians and facilitate standardization (58, 83, 84). Similar suggestions were made in primary research studies, but specific recommendations for design and structure of ACPs were limited.

3.3.2. A collaborative approach

Multidisciplinary collaboration was encouraged, guided by specialists trained in ACP or palliative care (22, 43, 82), although it was noted that specialist teams are not universally available (39). Other suggestions included that non-medical team-members should assist with ACP, e.g., nurses and social workers (40, 67), or spiritual carers (19). Frameworks and tools were seen to address such concerns and to improve clinician confidence (39, 40, 42). A commentary by Ballantyne et al. (64) suggested that interpersonal barriers of social distancing could be overcome by increasing pre-illness ACP discussions.

3.3.3. Increasing community ACP education/literacy

The importance of promoting and increasing ACP education and literacy for the wider community was frequently recognised (20, 42, 61, 66, 85), including relationship-building with community, ethnic and religious groups (19, 68).

One commentary suggested that hospital-based policies, jurisdictional legislation and community campaigns needed to accompany the broadening ACP education for HCPs (67). Death education/literacy may be best embedded across all health curriculum levels (20). Other options proposed included templates and tools to facilitate ACPs, videos and telehealth to facilitate remote ACP, and creation of an integrated web-based system linked to electronic medical records (eMR) to facilitate ACP in the community (18, 48, 60, 61, 85).

Several other studies indicated a need to promote ACP literacy, but specific strategies were lacking (28, 56, 79, 86).

3.3.4. Upskilling and training for clinicians

Upskilling clinicians to improve ACP confidence was a recurring theme, highlighted by at least two narrative reviews (57, 87) and a consensus guideline (66). Proposed teaching strategies were varied, e.g., role-play, interactive multimedia, virtual training, online communication, and telephone debriefing (45, 85). One review suggested that training HCPs in assisted living communities could help communication across services (31).

3.3.5. Addressing legal and ethical issues which may impede ACP

Legal and ethical issues featured predominantly in commentaries. Suggestions included temporarily pausing stricter legal requirements for ACP during COVID (15). Several studies addressed resource utilization and most studies argued that ACP should be prioritized to reduce unwanted intensive/life-sustaining treatment in a stretched healthcare system (88). Clinician concerns regarding the ethics of CPR in COVID-19 patients were also noted (47). Nevertheless, one institution highlighted that resource availability and patient/family goals of care need to be balanced when making resuscitation decisions (74).

4. Discussion

This rapid review of ACP implementation in the initial phase of the pandemic (until April 2021) suggests a high level of worldwide interest since COVID emerged. ACP may benefit overwhelmed healthcare systems, and decision-making for patients, caregivers and clinicians, and improve bereavement experiences. A sense of urgency and eagerness to make recommendations was apparent, often without supporting high-quality evidence, as evident from the large proportion of commentaries (39), consensus guidelines (3) and case series/reports (3) included in this review. Most publications were from the USA and UK ─ severely affected countries, but also nations which are better resourced to produce and promote research, compared, for example, to economically developing countries, from which data were scarce. Settings spanning acute hospitals, community, aged care and outpatient services showcased the breadth of the locations affected, and the need for ACP in a diverse range of contexts.

We were not surprised by the focus on barriers and enablers of ACP during the pandemic. Many of these may be familiar to clinicians and health services managers in their own place of work. Some of the enablers were specific to the nature of a pandemic, such as the improved public awareness in the context of a life-threatening communicable condition. Others may seem intuitive, e.g., embracing a patient-centred approach to care (89), but are not always evident in practice. The variety of proposed solutions was reassuring in terms of timeliness and feasibility, with standardization, collaboration, education and ethical-legal considerations underpinning implementation into practice.

Two main lessons surfaced from this rapid review. First, the prevalence and clarity of goals of care discussions were often touched on as a priority issue for patient management, prevention of unwanted (non-goal-aligned) care, or transfer decisions, across the range of study types (31, 34–36, 50, 53, 57, 82, 90). Next, frequent references to online tools or resources (18, 56, 58, 83, 87) and virtual learning for clinicians and families including online family meetings (45, 50, 53, 57, 59, 60, 66), reflect rapid embracing of innovative approaches to facilitate ACP completion and circumvent face-to-face interactions. Both are reassuring findings which indicate that patient/family wishes on end-of-life care were not neglected in the chaos of the unanticipated demand for health services, although frequency and equity of access were not always optimal (53, 57), and absence of communication was perceived to lead to complex bereavement (61, 91).

A poignant aspect of COVID-19 was the vision of people dying in alone in hospital, unable to be with family and suffering respiratory discomfort. For families, this led to a complicated grief experience characterized by survivor guilt, anger and distress, while the true impact on the patients themselves who did not survive has not been well-captured. An obvious mitigating strategy in such circumstances was to increase ACP so all stakeholders were prepared, patients received the care they desired and symptoms were managed in line with individualised goals (40, 68, 76, 91, 92).

This review also identified several recommendations which were mooted to facilitate effective ACP: appropriate ACP design and structure, adoption of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to ACP, increasing public and community education and literacy in relation to ACP, upskilling of clinicians, and addressing legal and ethical issues which may be impede ACP. While existing frameworks may provide some foundation, these may require adaptation, not only for the context of the pandemic, but also to account for local population needs and resources. Related to this, embracing technological advances and online ACP platforms must be balanced against patient preferences and acceptability, and cognizance of potential consumer concerns, such as those identified, for example, regarding use of personalized health records, aspects like ease of use, usefulness and security risk (93).

The ethics of ACP, and the need to balance principles of autonomy, beneficence, maleficence and justice (94), are not unique to the pandemic context, but particular aspects have come to the fore in the context of resource strains (4). Furthermore, ACP is now, in contrast to its former documented-directive focused origins, acknowledged to be a largely communicative process (94). This brings with it rich opportunities to maintain a dynamic conversation with patients and their loved ones as values and preferences, and physical status and related prognosis, change over time.

4.1. Implications for practice

Our pandemic-related experience has pushed us to re-evaluate existing healthcare policies and practices, overcome new and longstanding barriers, and embrace new solutions, in ACP as in other areas of practice. Recommendations to improve ACP delivery were highlighted by this review, as above. Our findings suggests the pandemic has provided some impetus to drive adaptable ACP conversations at individual, local, and international levels. It has provided capacity, opportunity and motivation to review and enhance our existing ACP practices, the three ingrediaents for successful behavioral change (95). Hopefully the changes instituted and lessons learned have afforded an opportunity for longer term improvements in ACP practice and care that is respectful of, and responsive to, the values and needs of the individual patients we meet every day. Institution and maintenance of any such changes should be combined with assessment in order to identify ongoing gaps and opportunities for improvement.

4.2. Limitations of the review

Given the nature of a rapid review, we only used limited number of search terms which were specific to our objective, confined to searching English language publications in the early stages of the pandemic and from a single (but the largest) database, anticipated to contain the majority of relevant articles. Half of the publications reflected perception, early reactions and proposed solutions and were not interventions or evaluations of policies or practices. Our intention was to illustrate all perspectives given the uniqueness of this serious pandemic experience, and thus we included a broad range of literature, but also highlighted the empiric evidence from primary research studies separate to that from commentaries. A future review of subsequent publications in the late stages of the pandemic may report similar or different findings, and it would be interesting to compare our results with emerging lessons after longer exposure to the global threat, as well as in the non-English based literature. Findings from nations which were under-represented in the current search ad review would also be of interest.

5. Conclusion

Despite high demand for healthcare services, the pandemic provided opportunities for rapid implementation of ACP. Both barriers and enablers of ACP influence its uptake, and these need to be considered at all levels of healthcare planning- local, national and international- if ACP is to achieve wider reach. Evidence suggests clinicians, patients and families support the recent cultural shift that fosters positive ACP uptake; this may contribute to reduced overtreatment near end of life and improve patient and family experiences of severe illness and care (96). Ongoing evaluation of policy changes, effectiveness, acceptability and patient and family satisfaction of ACP implementation are warranted in order to guide best practice moving forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our institutional librarians for their assistance finding full texts.

Author contributions

SY, MC, and DN conceived and designed the study. SY completed the literature search. MC and SY screened abstracts and reviewed all full texts. DN, SY, and MC reached consensus on all eligibility discrepancies. SY performed data extraction. AS and EW reviewed data and assimilated findings. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2023.1242413/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180(11):1436–47. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. (2020) 323(18):1775–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. (2019). Retrieved 11 July from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html

- 4.Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A, Gristina GR, Livigni S, Mistraletti G, et al. Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances: the Italian perspective during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care. (2020) 24(1):165. 10.1186/s13054-020-02891-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2017) 53(5):821–32.e1. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White B, Tilse C, Wilson J, Rosenman L, Strub T, Feeney R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of advance directives in Australia. Intern Med J. (2014) 44(10):975–80. 10.1111/imj.12549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, Laux JP. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 46(1):65–70. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, Kent S, Kim J, Herbst N, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). (2017) 36(7):1244–51. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi S, McDonough IM, Kim M, Kim G. The association between the number of chronic health conditions and advance care planning varies by race/ethnicity. Aging Ment Health. (2020) 24(3):453–63. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1533521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekaireb R, Ahalt C, Sudore R, Metzger L, Williams B. “We take care of patients, but we don’t advocate for them”: advance care planning in prison or jail. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66(12):2382–8. 10.1111/jgs.15624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, Smith AK. Low completion and disparities in advance care planning activities among older medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. (2016) 176(12):1872–5. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes M, Cartwright C. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people’s attitudes to end-of-life decision-making and advance care planning. Australas J Ageing. (2015) 34(Suppl 2):39–43. 10.1111/ajag.12268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan LM, Sudore RL, Arellano Cuervo I, Bainto D, Olsen P, Kushel M. Barriers and solutions to advance care planning among homeless-experienced older adults. J Palliat Med. (2020) 23(10):1300–6. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Sun F, Liu Y, Kong D, De Fries CM. Attitude toward family involvement in end-of-life care among older Chinese Americans: how do family relationships matter? J Appl Gerontol. (2022) 41(2):380–90. 10.1177/0733464821996865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block BL, Smith AK, Sudore RL. During COVID-19, outpatient advance care planning is imperative: we need all hands on deck. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68(7):1395–7. 10.1111/jgs.16532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. (2017). Available at: https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/rapid-review-guide/en/

- 17.Morrow-Howell N, Galucia N, Swinford E. Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on older adults. J Aging Soc Policy. (2020) 32(4–5):526–35. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1759758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portz JD, Brungardt A, Shanbhag P, Staton EW, Bose-Brill S, Lin CT, et al. Advance care planning among users of a patient portal during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective observational study [observational study research support, N.I.H., extramural]. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22(8):e21385. 10.2196/21385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, Zhang LK, Smeltz RL, Cohen SE. A vital layer of support: one safety net hospital’s palliative care response to the pandemic. J Palliat Med. (2021) 24(10):1474–80. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAfee CA, Jordan TR, Cegelka D, Polavarapu M, Wotring A, Wagner-Greene VR, et al. COVID-19 brings a new urgency for advance care planning: implications of death education. Death Stud. (2020) 46(1):1–6. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1821262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinclair C, Nolte L, White BP, Detering K. Advance care planning in Australia during the COVID-19 outbreak: now more important than ever. Intern Med J. (2020) 50(8):918–23. 10.1111/imj.14937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berning MJ, Palmer E, Tsai T, Mitchell SL, Berry SD. An advance care planning long-term care initiative in response to COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69(4):861–7. 10.1111/jgs.17051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas S, Adhikari SD, Bhatnagar S. Integration of telemedicine for home-based end-of-life care in advanced cancer patients during nationwide lockdown: a case series. Indian J Palliat Care. (2020) 26(Suppl 1):S176–8. 10.4103/ijpc.Ijpc_174_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell TW, Ferrante LE, Brown T, Francis L, Widera E, Rhodes R, et al. AGS position statement: resource allocation strategies and age-related considerations in the COVID-19 era and beyond. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68(6):1136–42. 10.1111/jgs.16537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell TW, Francis L, Brown T, Ferrante LE, Widera E, Rhodes R, et al. Rationing limited healthcare resources in the COVID-19 era and beyond: ethical considerations regarding older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2020) 68(6):1143–9. 10.1111/jgs.16539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Unroe KT, Van den Block L. International COVID-19 palliative care guidance for nursing homes leaves key themes unaddressed. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(2):e56–69. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotze C, Roos JL. End-of-life decision-making capacity in an elderly patient with schizophrenia and terminal cancer. S Afr Fam Pract (2004). (2020) 62(1):e1–4. 10.4102/safp.v62i1.5111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuzuya M, Aita K, Katayama Y, Katsuya T, Nishikawa M, Hirahara S, et al. The Japan geriatrics society consensus statement “recommendations for older persons to receive the best medical and long-term care during the COVID-19 outbreak-considering the timing of advance care planning implementation” [practice guideline]. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2020) 20(12):1112–9. 10.1111/ggi.14075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivet EB, Blades CE, Hutson M, Noreika D. Chronic and sudden serious illness, COVID-19, and decision-making capacity: integrating advance care planning into the preoperative checklist for elective surgery. Am Surg. (2020) 86(11):1450–5. 10.1177/0003134820965957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valeri AM, Robbins-Juarez SY, Stevens JS, Ahn W, Rao MK, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2020) 31(7):1409–15. 10.1681/asn.2020040470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vipperman A, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD. COVID-19 recommendations for assisted living: implications for the future. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2021) 22(5):933–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West E, Moore K, Kupeli N, Sampson EL, Nair P, Aker N, et al. Rapid review of decision-making for place of care and death in older people: lessons for COVID-19. Age Ageing. (2021) 50(2):294–306. 10.1093/ageing/afaa289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye P, Fry L, Champion JD. Changes in advance care planning for nursing home residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2021) 22(1):209–14. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen AL, Davtyan M, Taylor J, Christensen C, Brown B. Perceptions of the importance of advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults living with HIV. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:636786. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.636786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salins N, Mani RK, Gursahani R, Simha S, Bhatnagar S. Symptom management and supportive care of serious COVID-19 patients and their families in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2020) 24(6):435–44. 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao CT, Chang WT, Yu WL, Toh HS. Management of acute cardiovascular events in patients with COVID-19. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 21(4):577–81. 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.04.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reja M, Naik J, Parikh P. COVID-19: implications for advanced care planning and end-of-life care. West J Emerg Med. (2020) 21(5):1046–7. 10.5811/westjem.2020.6.48049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kluger BM, Vaughan CL, Robinson MT, Creutzfeldt C, Subramanian I, Holloway RG. Neuropalliative care essentials for the COVID-19 crisis. Neurology. (2020) 95(9):394–8. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000010211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prost SG, Novisky MA, Rorvig L, Zaller N, Williams B. Prisons and COVID-19: a desperate call for gerontological expertise in correctional health care. Gerontologist. (2021) 61(1):3–7. 10.1093/geront/gnaa088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desai AS, Kamdar BB, Mehra MR. Special article—palliative care considerations for cardiovascular clinicians in COVID-19. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 63(5):696–8. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon AL, Goodman C, Achterberg W, Barker RO, Burns E, Hanratty B, et al. Commentary: COVID in care homes-challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery. Age Ageing. (2020) 49(5):701–5. 10.1093/ageing/afaa113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh AG, Deodhar J, Chaturvedi P. Navigating the impact of COVID-19 on palliative care for head and neck cancer. Head Neck. (2020) 42(6):1144–6. 10.1002/hed.26211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell VD, Silveira MJ. Palliative care for older adults with multimorbidity in the time of COVID 19. J Aging Soc Policy. (2021) 33(4–5):1–9. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1851436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin CT, Bookman K, Sieja A, Markley K, Altman RL, Sippel J, et al. Clinical informatics accelerates health system adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic: examples from Colorado. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27(12):1955–63. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mills S, Cioletti A, Gingell G, Ramani S. Training residents in virtual advance care planning: a new twist in telehealth. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2021) 62(4):691–8. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bender M, Huang KN, Raetz J. Advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Board Fam Med. (2021) 34(Suppl):S16–20. 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeFilippis EM, Ranard LS, Berg DD. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a view from trainees on the front line. Circulation. (2020) 141(23):1833–5. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.047260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galbadage T, Peterson BM, Wang DC, Wang JS, Gunasekera RS. Biopsychosocial and spiritual implications of patients with COVID-19 dying in isolation. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:588623. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho EP, Neo H-Y. COVID 19: prioritise autonomy, beneficence and conversations before score-based triage. Age Ageing. (2021) 50(1):11–5. 10.1093/ageing/afaa205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuntz JG, Kavalieratos D, Esper GJ, Ogbu N, Jr, Mitchell J, Ellis CM, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of inpatient palliative care E-family meetings during COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(3):e28–32. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osterman CK, Triglianos T, Winzelberg GS, Nichols AD, Rodriguez-O’Donnell J, Bigelow SM, et al. Risk stratification and outreach to hematology/oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. (2021) 29(3):1161–4. 10.1007/s00520-020-05744-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moorman S, Boerner K, Carr D. Rethinking the role of advance care planning in the context of infectious disease. J Aging Soc Policy. (2020) 44(4–5):1–7. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1824540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piscitello GM, Fukushima CM, Saulitis AK, Tian KT, Hwang J, Gupta S, et al. Family meetings in the intensive care unit during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2021) 38(3):305–12. 10.1177/1049909120973431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan EYY, Dubois C, Fong AHY, Shaw R, Chatterjee R, Dabral A, et al. Reflection of challenges and opportunities within the COVID-19 pandemic to include biological hazards into DRR planning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(4):1614. 10.3390/ijerph18041614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dattolo PC, Toccafondi A, Somma C. COVID-19 Pandemic: a chance to promote cultural sensitivity on advance care planning. J Palliat Med. (2021) 25(5):646. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auriemma CL, Halpern SD, Asch JM, Van Der Tuyn M, Asch DA. Completion of advance directives and documented care preferences during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [research support, N.I.H., extramural]. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3(7):e2015762. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta A, Bahl B, Rabadi S, Mebane A, 3rd, Levey R, Vasudevan V. Value of advance care directives for patients with serious illness in the era of COVID pandemic: a review of challenges and solutions [review]. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2021) 38(2):191–8. 10.1177/1049909120963698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paladino J, Mitchell S, Mohta N, Lakin JR, Downey N, Fromme EK, et al. Communication tools to support advance care planning and hospital care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a design process [research support, non-U.S. Gov’t]. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. (2021) 47(2):127–36. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rabow MW, Keyssar JR, Long J, Aoki M, Kojimoto G. Palliative care education during COVID-19: the MERI center for education in palliative care at UCSF/Mt. Zion. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2021) 38(7):10499091211000285. 10.1177/10499091211000285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith GM, Hui FA, Bleymaier CR, Bragg AR, Harman SM. What if I get seriously ill? A virtual workshop for advance care planning during COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(5):e21–4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, Marshall S, Chamberlain C, Koffman J. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(2):e81–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adams C. Goals of care in a pandemic: our experience and recommendations. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(1):e15–7. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Back A, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills in the age of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 172(11):759–60. 10.7326/M20-1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ballantyne A, Rogers WA, Entwistle V, Towns C. Revisiting the equity debate in COVID-19: ICU is no panacea. J Med Ethics. (2020) 46(10):641–5. 10.1136/medethics-2020-106460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heyland DK. Advance care planning (ACP) vs. advance serious illness preparations and planning (ASIPP). Healthcare (Basel). (2020) 8(3):218. 10.3390/healthcare8030218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Janssen DJA, Ekstroem M, Currow DC, Johnson MJ, Maddocks M, Simonds AK, et al. COVID-19: guidance on palliative care from a European respiratory society international task force. Eur Respir J. (2020) 56(3):2002583. 10.1183/13993003.02583-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raftery C, Lewis E, Cardona M. The crucial role of nurses and social workers in initiating end-of-life communication to reduce overtreatment in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontology. (2020) 66(5):427–30. 10.1159/000509103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughes MC, Vernon E. Hospice response to COVID-19: promoting sustainable inclusion strategies for racial and ethnic minorities. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2021) 64(2):101–5. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1830218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, White P. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(1):e70–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moore KJ, Sampson EL, Kupeli N, Davies N. Supporting families in end-of-life care and bereavement in the COVID-19 era. Int Psychogeriatr. (2020) 32(10):1245–8. 10.1017/S1041610220000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan HY. The underappreciated role of advance directives: how the pandemic revitalises advance care planning actions. Eur J Health Law. (2020) 27(5):451–75. 10.1163/15718093-BJA10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Block BL, Jeon SY, Sudore RL, Matthay MA, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Patterns and trends in advance care planning among older adults who received intensive care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180(5):786–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Essomba MJN, Ciaffi L, Etoundi PO, Esiene A. Palliative and end-of-life care in COVID-19 management in sub-Saharan Africa: a matter of concern. Pan Afr Med J. (2020) 35(Suppl 2):130. 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.130.25288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fausto J, Hirano L, Lam D, Mehta A, Mills B, Owens D, et al. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID-19-the UW medicine experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60(1):e21–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hopkins SA, Lovick R, Polak L, Bowers B, Morgan T, Kelly MP, et al. Reassessing advance care planning in the light of COVID-19. Br Med J. (2020) 369:m1927. 10.1136/bmj.m1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Janwadkar AS, Bibler TM. Ethical challenges in advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Bioeth. (2020) 20(7):202–4. 10.1080/15265161.2020.1779855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosenberg AR, Popp B, Dizon DS, El-Jawahri A, Spence R. Now, more than ever, is the time for early and frequent advance care planning [research support, N.I.H., extramural research support, non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38(26):2956–9. 10.1200/JCO.20.01080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Singh S, Herrmann K, Cyriacks W, Youngwerth J, Bickel KE, Lum HD. Increasing medical power of attorney completion for hospitalized patients during the COVID pandemic: a social work led quality improvement intervention. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2021) 61(3):579–84.e1. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lin MH, Hsu JL, Chen TJ, Hwang SJ. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of advance care planning services within the veterans administration system in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. (2021) 84(2):197–202. 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iacobucci G. COVID-19: don't apply advance care plans to groups of people, doctors’ leaders warn. Br Med J. (2020) 369:m1419. 10.1136/bmj.m1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Coleman JJ, Botkai A, Marson EJ, Evison F, Atia J, Wang J, et al. Bringing into focus treatment limitation and DNACPR decisions: how COVID-19 has changed practice. Resuscitation. (2020) 155:172–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bolt SR, van der Steen JT, Mujezinović I, Janssen DJA, Schols JMGA, Zwakhalen SMG, et al. Practical nursing recommendations for palliative care for people with dementia living in long-term care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 113:103781. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gaur S, Pandya N, Dumyati G, Nace DA, Pandya K, Jump RLP. A structured tool for communication and care planning in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21(7):943–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roberts B, Wright SM, Christmas C, Robertson M, Wu DS. COVID-19 pandemic response: development of outpatient palliative care toolkit based on narrative communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2020) 37(11):985–7. 10.1177/1049909120944868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL. Deconstructing the complexities of advance care planning outcomes: what do we know and where do we go? A scoping review. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69(1):234–44. 10.1111/jgs.16801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Funk DC, Moss AH, Speis A. How COVID-19 changed advance care planning: insights from the West Virginia center for End-of-life care [observational study]. J Pain Sympt Manage. (2020) 60(6):e5–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Selman L, Lapwood S, Jones N, Pocock L, Anderson R, Pilbeam C, et al. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/advance-care-planning-in-the-community-in-the-context-of-covid-19/ Advance care planning in the community in the context of COVID-19. (2020). Retrieved 20/03/2021 from:

- 88.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA. (2020) 323(18):1771–2. 10.1001/jama.2020.4894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ashana DC, D’Arcangelo N, Gazarian PK, Gupta A, Perez S, Reich AJ, et al. “Don’t talk to them about goals of care”: understanding disparities in advance care planning. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2022) 77(2):339–46. 10.1093/gerona/glab091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burke RV, Rome R, Constanza K, Amedee M, Santos C, Leigh A. Addressing palliative care needs of COVID-19 patients in New Orleans, LA: a team-based reflective analysis. Palliat Med Rep. (2020) 1(1):124–8. 10.1089/pmr.2020.0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy. (2020) 32(4-5):425–31. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1764320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cavalier JS, Maguire JM, Kamal AH. Beyond traditional advance care planning: tailored preparedness for COVID-19 [letter]. J Pain Sympt Manage. (2020) 60(5):e4–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alsyouf A, Lutfi A, Alsubahi N, Alhazmi FN, Al-Mugheed K, Anshasi RJ, et al. The use of a technology acceptance model (TAM) to predict Patients’ usage of a personal health record system: the role of security, privacy, and usability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20(2):1347. 10.3390/ijerph20021347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Westbye SF, Rostoft S, Romøren M, Thoresen L, Wahl AK, Pedersen R. Barriers and facilitators to implementing advance care planning in naïve contexts—where to look when plowing new terrain? BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23(1):387. 10.1186/s12877-023-04060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Social Change UK. COM-B_and Changing_Behaviour. (2019). Available at: https://social-change.co.uk/files/02.09.19_COM-B_and_changing_behaviour_.pdf

- 96.Cardona M, Anstey M, Lewis ET, Shanmugam S, Hillman K, Psirides A. Appropriateness of intensive care treatments near the end of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breathe (Sheffield, England). (2020) 16(2):200062. 10.1183/20734735.0062-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.