Abstract

MITF, a basic-Helix-Loop-Helix Zipper (bHLHZip) transcription factor, plays vital roles in melanocyte development and functions as an oncogene. To explore MITF regulation and its role in melanoma, we conducted a genetic screen for suppressors of the Mitf-associated pigmentation phenotype. An intragenic Mitf mutation was identified, leading to termination of MITF at the K316 SUMOylation site and loss of the C-end intrinsically disordered region (IDR). The resulting protein is more nuclear but less stable than wild-type MITF and retains DNA-binding ability. Interestingly, as a dimer, it can translocate wild-type and mutant MITF partners into the nucleus, improving its own stability and ensuring an active nuclear MITF supply. Interactions between K316 SUMOylation and S409 phosphorylation sites across monomers largely explain the observed effects. Notably, the recurrent melanoma-associated E318K mutation in MITF, which affects K316 SUMOylation, also alters protein regulation in concert with S409, unraveling a novel regulatory mechanism with unexpected disease insights.

Keywords: Mitf, melanoma, protein stability, nuclear export, suppressor, transcription

Introduction

Transcription factors play a crucial role in gene regulation, and most of them have large unstructured domains termed intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) in addition to their DNA-binding domains1. Due to the lack of tools and links to phenotypes, understanding the structure-function relationships of IDRs and their specific contributions to in vivo activity and disease has proven challenging. The basic Helix-Loop-Helix-leucine zipper (bHLHZip) transcription factor MITF is the master regulator of melanocyte development and pigmentation. It also plays a critical role in melanoma, a highly aggressive skin cancer originating from melanocytes2, 3. Importantly, MITF protein activity can be modulated either transiently through environmental signals or permanently by mutations leading to critical effects on the phenotype. In melanoma, MITF activity mediates phenotype plasticity such that high MITF activity promotes differentiation and proliferation, whereas low MITF activity results in a stem cell-like phenotype and enhances migration2. MITF binds to E- (CACGTG) and M- (TCATGTG) box motifs as a homodimer or as a heterodimer with its closest relatives, TFE3, TFEB, and TFEC4, 5. A unique 3-amino acid sequence in the zipper domain restricts dimerization of these proteins such that they do not dimerize with other bHLHZip proteins6–8. Outside the bHLHZip domain, MITF consists of N-terminal and C-terminal IDRs, located on either side of the bHLHZip DNA-binding and dimerization domain, largely of unknown function.

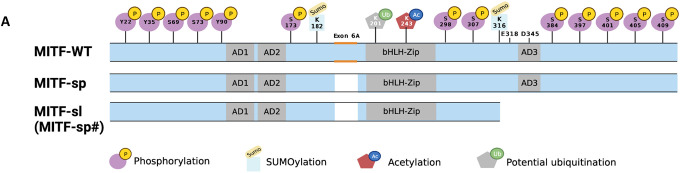

Importantly, multiple phosphorylation sites have been mapped in the IDRs of MITF9, and some (including S69, S73, and S173) have been suggested to lead to nuclear export or retention of MITF in the cytoplasm, some (S73 and S409) to affect transcription regulation and other sites have been proposed to affect protein stability (S73, S397, S401, S405, and S409) (Figure 1A)9. Interestingly, the S73 and S409 residues have been shown to be priming sites for GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of downstream residues (S69 in the case of S73 and S397, S401 and S405 in the case of S40910, 11. MITF has also been shown to be SUMOylated at K182 and K31612, 13 and potentially ubiquitinylated at K201 and K26514, 15. However, the biological function of the different post-translational modifications (PTMs) is largely unknown.

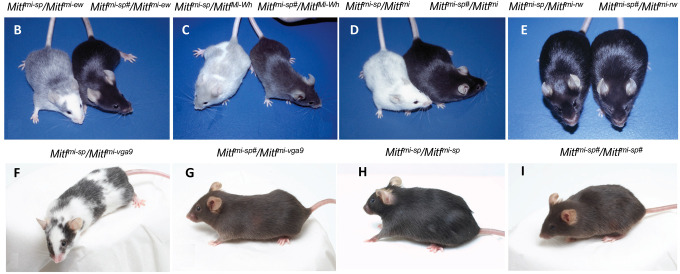

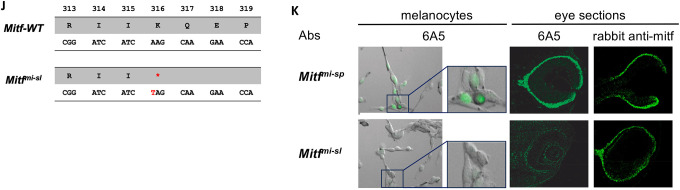

Figure 1: Coat color phenotypes and molecular alteration associated with the induced Mitfmi-sp# suppressor mutation (Mitfmi-sl).

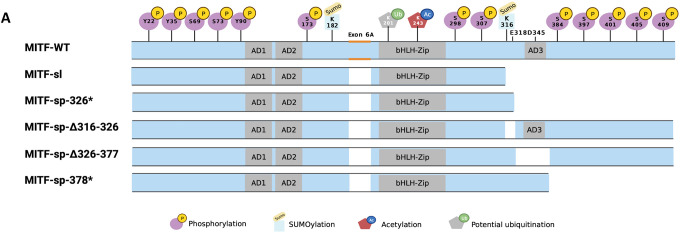

(A) Graphical depiction of the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl (MITF-sp#) proteins indicating the domains affected. Also shown are the post-translational modifications that have been reported in MITF.

(B) NAW-Mitfmi-ew/B6-Mitfmi-sp and NAW-Mitfmi-ew/B6-Mitfmi-sp# compound heterozygotes.

(C) B6-MitfMi-Wh/B6-Mitfmi-sp and B6-MitfMi-Wh/B6-Mitfmi-sp# compound heterozygotes.

(D) B6-Mitfmi-sp/B6-Mitfmi and B6-Mitfmi-sp#/B6-Mitfmi compound heterozygotes. Notice the dramatic suppression of the phenotype from near-white to black coat color.

(E) B6-Mitfmi-sp/B6-Mitfmi-rw and B6-Mitfmi-sp#/B6-Mitfmi-rw animals.

(F) B6-Mitfmi-sp/B6-Mitfmi-vga9.

(G) B6-Mitfmi-sp#/B6-Mitfmi-vga9.

(H) B6-Mitfmi-sp/Mitfmi-sp.

(I) B6-Mitfmi-sp #/Mitfmi-sp#.

(J) Graphical depiction of the Mitfmi-sl mutation.

(K) Antibody staining of melanocytes and eye sections from Mitfmi-sp and Mitfmi-sl tissues. The antibodies are 6A5, which recognizes the C-end of MITF, and a polyclonal rabbit anti-MITF antibody.

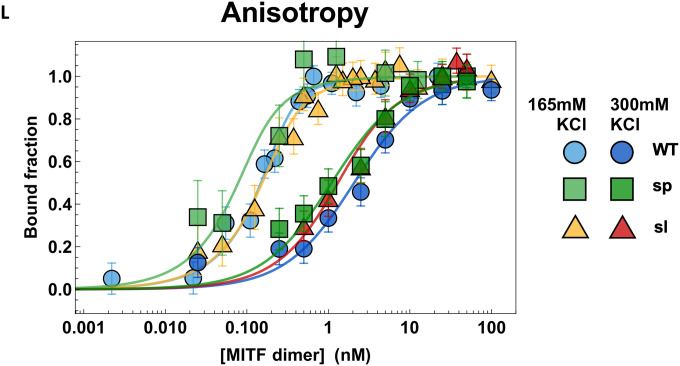

(L) DNA binding curves of recombinantly expressed human MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins to M-box probe measured by Fluorescence anisotropy at 165 mM KCl and 300 mM KCl. MITF-WT protein in light and dark blue circles, MITF-sp light and dark green boxes, and MITF-sl in yellow and red triangles. Error bars represent two standard deviations of fit error at each point.

Individuals carrying the E318K germline mutation in MITF are predisposed to melanoma16, 17. Carriers of a single allele have increased nevus count and are predisposed to melanoma; one of the initial reports also showed an increased risk of renal cell carcinoma16, and a link to uterine carcinosarcoma has also been described18. The E318K mutation abolishes SUMOylation of the MITF protein at K31616, 17, 19, and ChIP-seq studies have shown that the MITF-E318K protein has increased occupancy at known MITF-target genes compared to the wild type protein but also binds to an increased number of genes.

However, transcriptomic studies did not reveal major changes in gene expression16, 17. Mice carrying the E318K mutation exhibited slightly reduced pigmentation in both homo- and heterozygous conditions, whereas MitfE318K/+; BrafV600E/+ mice had an increased number of nevi. While the E318K mutation did not affect the latency or morphology of BrafV600E tumors, it accelerated tumor initiation in BrafV600E/+; Pten−/− mice19. Currently, it is not understood how the E318K mutation affects protein function or how it predisposes to melanoma.

Due to its obvious effects on pigmentation, MITF provides an excellent sensitized system for searching for suppressor mutations. In mice, over 40 different mutant alleles have been found in Mitf that can be arranged in an allelic series according to the severity of their phenotypic effects as evidenced by coat color changes20. At one end of the spectrum is the original and most severe allele Mitfmi (Table S1; deletion of one of four arginines in the DNA-binding domain), which leads to a white coat, severe microphthalmia, and osteopetrosis and results in death at 3–4 weeks of age. At the other end of the spectrum is the mildest Mitf mutation, Mitfmi-spotted (Mitfmi-sp), which has no visible phenotype even when homozygous. The Mitfmi-sp mutation lacks the alternative 18bp exon 6A that encodes six amino acids upstream of the DNA-binding domain (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the Mitfmi-sp allele induces a white spotting phenotype when combined with other mutations at the locus21, 22. For example, when the Mitfmi-sp allele is mated to the original Mitfmi mutation, the offspring exhibit a white coat with occasional grey areas and no microphthalmia. The intermediate coat pigmentation alterations obtained in compound heterozygotes with Mitfmi-sp made this allele ideal for an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen for dominant suppressors or enhancers of the Mitf phenotype. Using this approach, we expected to find mutations in novel genes participating in the molecular pathways through which Mitf regulates pigment cell development and melanogenesis. We isolated a mutation that suppressed the Mitf phenotype, but intriguingly, it is a derivative of the Mitfmi-sp allele that lacks 104 residues of the carboxyl end (C-end). The induced Mitf suppressor mutation highlights the critical role of the IDR at the C-end of MITF in determining its stability, subcellular location, and transcriptional activity. Importantly, it also sheds light on the molecular effects of the E318K mutation in melanoma.

Results

Generation and analysis of an Mitf suppressor mutation

To screen for dominant mutations that suppress the Mitf phenotype, we crossed NAW-Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-ew females with C57BL/6J-Mitfmi-sp/Mitfmi-sp males that had been treated previously with the mutagen N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU). We screened for coat pigmentation changes in the F1 offspring (Figure S1A). While Mitfmi-sp homozygotes have no visible coat color phenotype, animals homozygous for the Mitfmi-ew mutation are white, severely microphthalmic, and exhibit mild hyperostosis23 (Table S1). Compound heterozygotes for these two mutations have a “salt-and-pepper” body color with a white head, belly, and feet (Figure 1B, left). ENU-treated F1 Mitfmi-sp/Mitfmi-ew heterozygotes were screened for coat pigmentation changes (Figure S1A). Of 63 NAW-Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-ew females, less than 50% produced progeny, resulting in a total of 470 offspring. In one of the matings, a deviant offspring female, marked by a ‘#’, showed a considerably darker coat (near-black coat with pale ears, tails, and toes) compared to its littermates, suggesting the presence of a mutagenized chromosome (Figure 1B, right).

When this Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp# female was bred to a C57BL/6J-Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-ew male, two classes of offspring resulted: white microphthalmic mice of the genotype Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-ew and mice of the genotype Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp# with the darkly pigmented phenotype of their mother (Figure S1B, right). This confirmed that the ‘#’ mutation altering the Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp phenotype is dominant, at least for the combination of these two alleles. Also, because the above crosses did not yield mice with the phenotype expected for Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp mice, the novel suppressor mutation is likely closely genetically linked with Mitfmi-sp or lies within the gene itself rather than on a different chromosome. Crossing the near-black Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp# mice to C57BL/6J animals only resulted in black offspring.

When the near-black Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-sp# mice were mated to white microphthalmic MitfMi-Wh/MitfMi-Wh homozygotes (Table S1), there were again two classes of offspring: the expected white mice with average eye size (Mitfmi-ew/MitfMi-Wh heterozygotes) and “steel”-colored mice with pale ears, tail, toes, and a belly spot (MitfMi-Wh/Mitfmi-sp# animals, Figure 1C, right). The coat color of the latter animals was much darker than that of the corresponding MitfMi-Wh/Mitfmi-sp animals (Figure 1C, left). The color was even darker than MitfMi-Wh/Mitf-WT mice, suggesting that the new mutant represents a gain-of-function compared to the wild type. Similar effects were also seen when animals carrying the new Mitfmi-sp# mutation were crossed to the dominant-negative Mitfmi (Figure 1D), MitfMi-or, and MitfMi-b mutations (Figures S1C–E) or the null mutation Mitfmi-vga9 (Figures 1F and 1G; Table S1). These observations showed that the suppressing effects of the new mutation were not restricted to the Mitfmi-ew allele and did not depend on the genetic background of the alleles tested (compare Figure 1B to S1B and S1C to S1D). However, the new mutation did not affect the coat color of the recessive Mitfmi-rw allele when compared to Mitfmi-rw/Mitfmi-sp animals (Figure 1E), reflecting the fact that the latter animals are already black and no further improvement in coat color is possible. Similarly, no effects were observed on eye size or bone development in any of the combinations since both phenotypes are normal in Mitfmi-sp homozygotes or their compound heterozygotes.

Intercrosses of Mitf-WT/Mitfmi-sp# heterozygotes produced two classes of offspring: normal non-agouti (black) mice and mice with a diluted “brownish” coat color in a 3 to 1 ratio (compare Figure 1H to 1I). Genotyping showed that the “brownish” animals were homozygous for Mitfmi-sp#. Thus, intriguingly, the new mutation suppresses the spotting phenotype of most combinations of Mitf alleles but causes the Mitfmi-sp# to express a partial loss-of-function, altering the coat color from black to brown.

Molecular analysis of the Mitfmi-sp# mutation

From the various crosses described above, it was clear that the new mutation is either tightly linked to Mitf on chromosome 6 or is an intragenic mutation. We, therefore, performed RT-PCR and sequencing studies of Mitf in total RNA isolated from homozygous Mitfmi-sp# heart and kidney. Consistent with the induced origin of the mutation, sequencing of the cDNA revealed the previously characterized Mitfmi-sp mutation (the lack of the 18 bp alternative exon)24. In addition, an A to T transversion was detected at nucleotide 1075 of the cDNA of the MITF-M isoform25, replacing the codon for K316 with a stop-codon resulting in premature truncation of the protein in the last exon, exon 9 (Figure 1J). The mutation was confirmed by genomic sequencing. The # mutation is, therefore, an intragenic re-mutation of the Mitfmi-sp allele, now termed Mitfmi-spotless (Mitfmi-sl), that leads to a protein, MITFmi-sl, that lacks 104 residues of the C-end, including the K316 SUMOylation site12, 13, a caspase cleavage site (D345)26, phosphorylation sites implicated in the mTOR, GSK3β, and MAP kinase signal transduction pathways (S384, S397, S401, S405, and S409)9 and the proposed transcription activation domain 3 (AD3)27 (Figure 1A).

To confirm that the C-end of MITF is missing from the Mitfmi-sl mutant, we stained primary melanocyte cultures generated from homozygous Mitfmi-sl and Mitfmi-sp embryos and eye sections from Mitfmi-sl and Mitfmi-sp mutants with the monoclonal antibody 6A5, which reacts with the C-end of MITF28 and should not stain cells or tissues from Mitfmi-sl animals. As shown in Figure 1K, the antibody did not give a signal in Mitfmi-sl melanocytes or eye sections, whereas Mitfmi-sp melanocytes and eye sections exhibited clear nuclear staining. In contrast, eye sections from both genotypes stained positive with a polyclonal rabbit anti-MITF antibody. This shows that the carboxyl-end (C-end) of MITF is absent from melanocytes and eyes of Mitfmi-sl homozygotes.

Mitfmi-sl/Mitfmi-sl homozygotes show normal melanoblast development but delayed onset of pigmentation

To determine if the suppressor mutation affects cell proliferation, we performed a BrdU incorporation assay in the non-melanocytic HEK293 cells after overexpressing the MITFmi-sp or MITFmi-sl proteins (in the discussion below, we simplify the nomenclature of the mutants to MITF-sp, MITF-sl and so on). All the MITF mutants in this study were generated with the mouse MITF-M isoform. No significant difference was observed (69 ± 2% BrdU positivity in MITF-sp expressing cells versus 71 ± 2% BrdU positivity in MITF-sl expressing cells) (Figure S2A). IncuCyte live cell imaging also showed no significant changes in the proliferation of the human A375P melanoma cells (which express little endogenous MITF) upon overexpressing MITF-WT, MITF-sp or MITF-sl proteins over time (Figure S2B).

To count melanoblast numbers during development in vivo, we generated Mitfmi-sp and Mitfmi-sl homozygous embryos carrying a melanoblast marker transgene, Dct-LacZ29. In wild-type C57BL/6 embryos, an increased number of Dct-LacZ-labeled cells was observed with developmental time, as expected. Similar increases were seen in Mitfmi-sp and Mitfmi-sl homozygotes, although the total number of X-gal labeled cells seemed, on average, reduced compared to wild type (Figures S2C and S2D). The analysis of X-gal staining in the respective embryos suggests that there are generally fewer melanocytes in the two mutations, although there may be some region-specific differences.

In Mitfmi-sp ex vivo neural crest cell cultures, pigmented melanocytes appeared on day 10 after explantation and increased steadily through day 17 (Figure S3A), whereas in ex vivo cultures from Mitfmi-ls embryos, they first emerged on day 14 and had a lower average count by day 17 than was observed in Mitfmi-sp embryos (Figure S3A). Nevertheless, in both Mitfmi-sp and Mitfmi-sl cultures, cells positive for the MITF protein (melanoblasts) were detected as early as day 1 of culture (Figure S3A, inset, for day 3 of culture), suggesting that the delay in pigmentation is not due to a delay in melanoblast appearance. Consistent with these observations, Mitfmi-sl homozygous pups develop pigmentation later than Mitfmi-sp pups (Figure S3B, the difference is particularly striking on postnatal days 2 and 3). However, this difference was only seen when the mice were homozygous for these alleles and not when the alleles were combined, for instance, with Mitfmi-vga9 (Figure S3C, compare mice labeled #1 and #3) or with Mitf-WT (Figure S3C, compare mice labeled #2 and #4). Hence, the delayed onset of pigmentation in culture and the “brownish” color seen in adult Mitfmi-sl homozygotes suggest that the mutation leads to a partially functional protein. However, it is not caused by prolonged cell proliferation affecting differentiation initiation.

The MITF-sl protein forms stable dimers and binds DNA

We determined the dimerization and DNA-binding ability of the MITF-sl protein. For this, we co-expressed Flag-tagged versions of the non-DNA binding mutant proteins MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew (Table S1) together with the MITF-WT-GFP, MITF-sp-GFP, or MITF-sl-GFP proteins in A375P melanoma cells followed by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) using FLAG-antibodies. The results showed that the non-DNA binding MITF mutant proteins successfully immunoprecipitated all three GFP-labeled proteins (Figure S4A). We further confirmed the interactions between MITF-mi-Flag and GFP-tagged MITF-WT, -sp, and -sl proteins by Blue native PAGE30. The results suggest that the MITF-mi protein as well as the MITF-WT, -sp, and -sl proteins can form both hetero- and homodimers (Figures S4B and S4C). We observed that in cells co-expressing MITF-mi and MITF-sl, heterodimers predominate over homodimers. Additionally, MITF-sl was found mostly as a dimer in cells expressing only MITF-sl (Figure S4B and S4C). Our findings suggest that MITF-sl may have a stronger dimerization affinity than MITF-WT.

We measured the DNA binding affinity of recombinant human MITF-WT, -sp, and -sl proteins to a fluorescently labeled M-box probe by measuring changes in anisotropy on individual molecular complexes with single-molecule spectroscopy. Quantification gave dissociation constants for all constructs at 300 mM KCl that were within one standard deviation from each other (Figures 1L, Table S2), while the affinities at 165 mM KCl (KD<250 pM) were too high to compare accurately. We also used single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) as two additional and independent measures of MITF interactions with DNA (Figures S5A–D). All three methods yielded similar dissociation constants for all constructs at 300 mM KCl (Figures 1L, S5A–D and Table S2), and similar to that reported for the DNA binding domain alone31. From the FCS data, we observed a smaller change in diffusion time upon DNA binding of MITF-sl than -sp and -WT, consistent with its smaller size (Figure S5A, Table S2). The electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) also showed similar steady-state affinity binding to M-box DNA of mouse MITF-WT, -sp, and -sl (Figure S5E). Co-translating the non-DNA binding MITF-mi with MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl, thus allowing heterodimerization before EMSA showed that increasing amount of the MITF-mi protein interfered with the DNA binding of all three proteins. However, MITF-mi was more effective at interfering with MITF-WT than with either of the mutant proteins lacking exon 6A (Figure S5E), which is consistent with previous observations6. A slightly different picture emerged when the proteins were translated separately and subsequently mixed together before the EMSA. Again, the MITF-mi protein was more effective at interfering with the DNA binding of the MITF-WT protein than with that of the MITF-sp and MITF-sl proteins. However, it was even less effective at interfering with the DNA-binding of the MITF-sl protein (Figure S5F) than MITF-sp. This suggests that the MITF-sl homodimers are more stable than either the MITF-WT or MITF-sp homodimers and, thus, less prone to interference by a dominant negative protein such as the MITF-mi protein.

The MITF-sl protein differentially affects gene expression

To determine if Mitf RNA expression was affected by the Mitfmi-sl mutation, we quantitated Mitf RNA expression in the heart, an organ that is not overtly involved in any of the extant Mitf mutant phenotypes. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that expression of Mitf RNA is reduced to 66% in Mitfmi-sp hearts compared to wild-type controls but remains above wild-type levels (116%) in Mitfmi-sl hearts (Figure S6). Similar observations were made when RNA obtained from the skin was quantitated (Figure S6).

To investigate the effects of the Mitfmi-sl mutation on gene expression, we induced the expression of mouse MITF proteins at an equal level in A375P cells and harvested RNA at regular intervals for qPCR analysis. The fold change of MITF target genes was first normalized to EV and then to the proportion of MITF proteins retained in the nucleus. Consistent with previous work32, 33, our results showed that the expression of the endogenous human MITF mRNA was considerably reduced over the 36 hours sampling period upon overexpressing mouse MITF-WT and MITF-sl proteins (Figure S7A). The expression of the CDH2 and NRP1 genes, both of which have been shown to be repressed by MITF (Dilshat et al., 2021), was also significantly reduced upon overexpression of MITF-WT and MITF-sl (Figures S7B and S7C). While MITF-WT activated the expression of PMEL and TRIM63, MITF-sl exhibited about half the activating ability of WT (Figures S7D and S7E). Interestingly, the MITF-sl protein was severely impaired in activating the expression of the pigmentation genes TYRP1, MLANA, TYR, and DCT (Figures S7F–I). Our results suggest that the 316–419 domain is critical for selective transcriptional activation, whereas the repressive activity of MITF remains intact, at least for the genes tested.

The Mitfmi-sl mutation affects protein stability and localization.

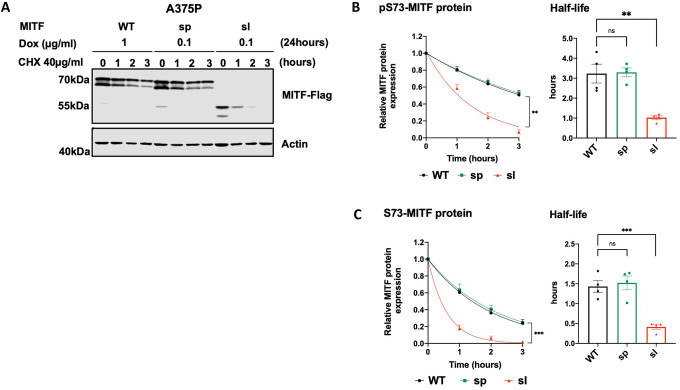

We also investigated the effect of the Mitfmi-sl mutation on protein stability by expressing Flag-tagged (at C-end) MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins in a doxycycline (dox)-inducible vector transfected into A375P melanoma cells. Expression of the proteins was equalized by treating the cells with varying concentrations of dox for 24 hours. The cells were then treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) for different periods and harvested to visualize MITF protein by Western blotting. The MITF protein is observed as two bands where the upper band is phosphorylated at S73 (hereafter referred to as pS73-MITF), and the lower band is not phosphorylated at S73 (hereafter referred to as S73-MITF)10, 34. The bands on the Western blot were quantitated, and the changes in protein concentration were plotted over time. This data was used to calculate protein half-life, defined as the time required to reduce the initial protein abundance to 50%. The MITF-WT and MITF-sp proteins had comparable half-lives of 3.2 hours for pS73-MITF and 1.2 hours for S73-MITF (Figures 2A–C). Critically, the MITF-sl protein was considerably less stable, with half-lives of 1.2 and 0.4 hours for the pS73 and S73 forms, respectively (Figures 2A–C). To confirm that exon 6A does not contribute substantially to MITF stability, we measured the stability of the pS73 and S73 versions of MITF-Wh with and without exon 6A and found that they were not significantly different (Figures S8A and S8B). When overexpressed in the 501Mel and SKmel28 melanoma cell lines (which express high levels of MITF), the MITF-sl protein was also less stable than the MITF-WT and MITF-sp proteins, regardless of the S73 phosphorylation status (Figures S8C–F). We also tested the stability of proteins carrying the Flag tag at the N-end or GFP tag at the C-end. In all cases, MITF-sl protein was less stable than MITF-WT and MITF-sp, regardless of the fusion tags and their location (Figures S8G–I). Our finding, therefore, suggests that the absence of the 316–419 domain significantly reduces the stability of MITF. Furthermore, in all cases, the S73 MITF (lower band) protein was degraded faster than the pS73 form (upper band). Alternatively, the S73 protein may be phosphorylated and thus become pS73 during the experiment.

Figure 2: The carboxyl-domain of Mitf controls RNA and protein levels as well as its subcellular localization.

(A) Western blot analysis of the Mitf-Flag proteins upon cycloheximide treatment. The dox-inducible A375P cells expressing the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins were treated with doxycycline for 24h to induce similar expression of the indicated mutant MITF proteins before treating them with 40 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours. The blots were stained using Flag antibody and protein quantitated using the odyssey imager and ImageJ. Actin was used as a loading control.

(B), (C) Non-linear regression (one-phase decay) and half-life analysis of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF proteins over time after CHX treatment in A375P melanoma cells. The relative MITF protein levels to T0 were calculated, and non-linear regression analysis was performed. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(D) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced for 24 hours to overexpress different MITF mutant proteins. MITF-WT, MITF-Wh, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl protein in whole cell lysate (W), cytoplasmic (C), and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. Actin and γH2AX were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

(E) Intensities of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF protein bands in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction from the western blot analysis in (E) were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

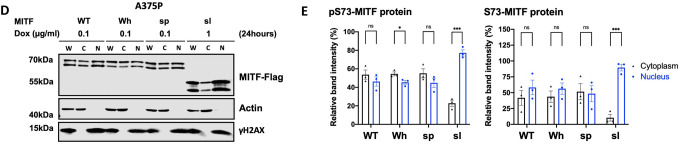

(F) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P cells transiently co-overexpressing the MITF-sl protein with the MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew mutant MITF proteins. MITF proteins in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. Actin and γH2AX were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. The MITF-sl protein migrates as a doublet at 50–55 kDa, whereas the other mutants migrate at 65–70 kDa.

(G) The intensities of the pS73- and S73- MITF-sl protein in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from western blot analysis (G) were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(H) Quantification of band intensities of the pS73- and S73-versions of the MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew proteins as determined from western blot analysis (G) in the nuclear fractions of A375P cells transiently co-overexpressing the MITF-sl protein with the indicated MITF mutant proteins. The intensities are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(I), (J), and (K) Western blot analysis of the degradation of the MITF-sl protein in the presence of non-DNA binding MITF mutations (MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew). The A375P cells were transiently co-transfected with MITF-sl and either MITF-mi, MITF-ew, or MITF-Wh for 24 hours before being treated with 55 μg/ml CHX. The amount of MITF protein was then compared by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(L) and (M) Non-linear regression (one-phase decay) and half-life analysis of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF proteins over time after CHX treatment. The relative MITF protein levels to T0 were calculated, and non-linear regression analysis was performed. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

To determine the effect of MITF-sl on subcellular localization, we used dox-inducible A375P melanoma cells overexpressing MITF-Flag fusion proteins and performed cellular fractionation. After inducing expression of MITF for 24 hours, the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were separated as described35, 36, and MITF proteins were characterized by Western blotting. For the MITF-WT and MITF-sp proteins, both pS73 and S73 bands were observed at similar ratios in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (Figures 2D and 2E). However, for MITF-sl, both pS73 and S73 bands were predominantly located in the nucleus (Figures 2D and 2E). The same results were observed when the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins were overexpressed in the 501Mel and SKmel28 melanoma cell lines (Figures S9A–D). Flag-tagging the MITF protein at the N-end or replacing the C-end Flag with GFP also resulted in a significantly increased nuclear presence of the MITF-sl protein (Figures S9E and S9F). Co-IP showed that nuclear accumulation of MITF-sl protein was not due to effects on interactions with 14–3-3 protein (Figure S9G), which has been shown to interact with MITF phosphorylated at S173 and lead to the retention of MITF in the cytosol in osteoclasts37. To determine if the six amino acids encoded by exon 6A were able to mediate nuclear localization, MITF lacking (−) or containing (+) this exon was transiently expressed in A375P cells. No difference was observed in the distribution of MITF between the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of the MITF-Wh and MITF-Wh(−) or MITF-sl(+) and MITF-sl constructs (Figures S9H and S9I). Taken together, we conclude that residues 316–419 of MITF, but not exon 6A or the tags, affect MITF subcellular localization.

MITFmi-sl translocates its Mitf partners into the nucleus and improves its own stability

Consistent with previous reports34, 38, stably expressed MITF-mi and MITF-ew proteins were primarily present in the cytoplasm (Figure S10A, compared with Figures 2D or 2E for MITF-WT or MITF-Wh proteins). To determine if the MITF-sl protein might affect the subcellular localization of the above non-DNA binding mutant MITF proteins, they were transiently co-overexpressed with the MITF-sl protein. As before, a significant portion of the pS73- and S73-MITF-sl proteins was observed in the nucleus (Figures 2F and 2G). In contrast to stably expressed proteins (Figure S10A), transiently expressed MITF-mi or MITF-ew showed equal distribution between cytoplasm and nucleus; no significant difference was noted between stable and transient expression of the MITF-Wh protein (Figures 2D–H). However, when co-expressed with the MITF-sl protein, they were all significantly translocated into the nucleus (Figures 2F–H). Similar results were observed in cells co-expressing MITF-sl and MITF-WT (Figures S10B–D). Our data, therefore, strongly suggest that the MITF-sl protein can dimerize with both mutant and WT proteins and induce nuclear localization of its partner by either translocating the dimer to the nucleus or keeping it from leaving the nucleus.

We assessed the stability of the MITF-sl protein in cells also expressing either MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, or MITF-ew. Interestingly, the stability of both pS73 and S73 MITF-sl was considerably increased in the presence of the MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew proteins, with the most pronounced effect observed in cells also expressing MITF-mi and MITF-ew (around 2.5-fold increase for pS73 and 3.5-fold increase for S73) (Figures 2I–M). However, the stability of the MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew dimeric partner proteins themselves remained unchanged upon co-expression of MITF-sl as compared to the condition when they were expressed in the absence of MITF-sl (Figures 2I–M). The stability of pS73 and S73 versions of MITF-sl was also significantly improved when co-expressed with MITF-WT (Figures S10E and S10F). To eliminate the possibility that we saturated the degradation machinery in the cells, we co-transfected the cells with MITF-sl-GFP and MITF-sl-Flag and measured the stability of MITF-sl-Flag protein. The results showed that the stability of MITF-sl-Flag was not affected by the presence of MITF-sl-GFP (Figure S10G). Taken together, our data suggest that the MITF-sl protein forms dimers with the MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew proteins which then drags them into the nucleus or prevents them from leaving the nucleus, leading to increased stability of the MITF-sl protein itself (without, however, changing the stability of the partner proteins). On balance, this may increase the formation of DNA-binding MITF-sl homodimers after dissociation from their dimeric partners, and so explain the genetic suppression effect observed in vivo. The effects on protein stability and gene expression changes induced in the presence of MITF-sl alone might explain the hypomorphic effect in Mitfmi-sl homozygotes. That this hypomorphic effect is not seen in compound heterozygotes with the non-DNA binding mutants may be due to the balance between nuclear import/export, effects on stability, and the rate of dissociation of MITF-sl from its dimeric partner and subsequent effects on transcription.

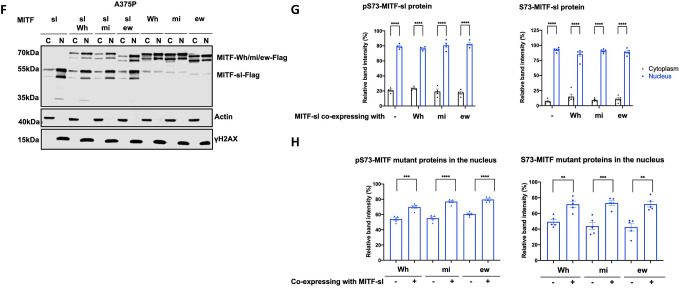

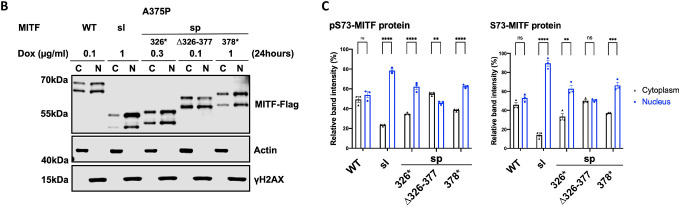

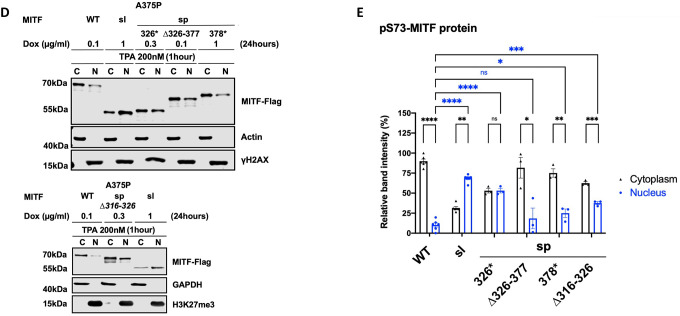

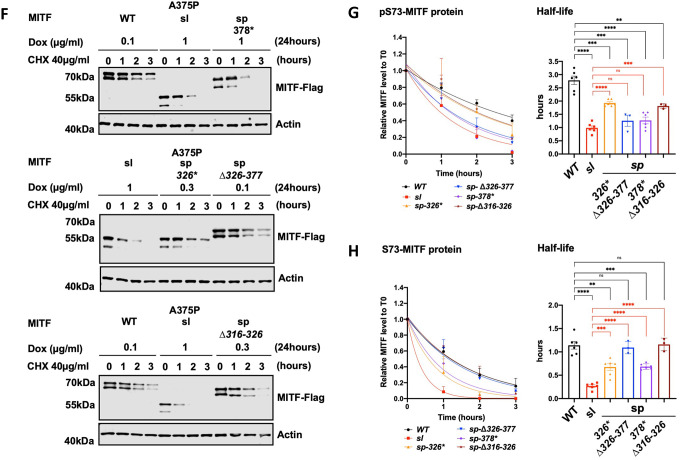

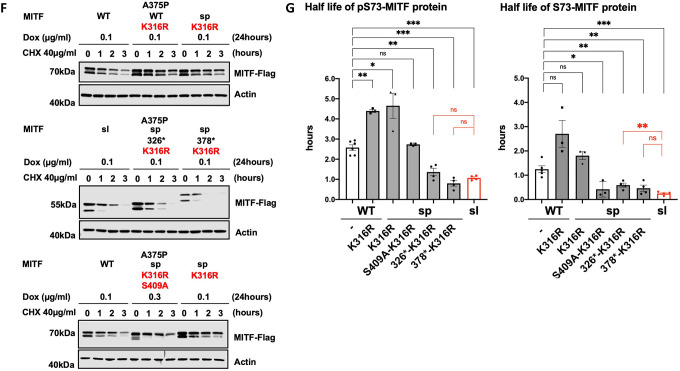

Effects on nuclear localization and stability are encoded in the carboxyl-domain

To determine which regions within the C-end of MITF contain its nuclear retention properties, we generated truncated versions of MITF-sp with Flag-tag fusion at the C-end in our inducible vector system (schematic diagram in Figure 3A). The S73-MITF-WT and S73-MITF-sp-Δ326–377 proteins are distributed equally between the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions; the pS73-MITF-sp-Δ326–377 was slightly more cytoplasmic (Figures 3B and 3C). In contrast, a significant portion of the MITF-sp-326* and MITF-sp-378* proteins was present in the nuclear fraction (Figures 3B and 3C), suggesting that the 378–419 domain, including the phosphorylation sites indicated in Figure 3A, plays an essential role in controlling the nuclear localization of MITF. Interestingly, the non-phosphorylatable alanine mutation at S409 led to slightly more nuclear localization of the pS73 MITF form, whereas the single S384A, S397A, S401A, and S405A mutations did not alter MITF nuclear localization (Figure S11A and S11B). However, the quadruple S397/401/405/409A mutation in MITF-sp (MITF-sp-4A) or MITF-WT (MITF-WT-4A) led to increased nuclear localization of the respective proteins (Figure S11A and S11B). This suggests that the phosphorylation cascade at the C-end may be involved in the cytoplasmic retention of MITF but that other elements within the C-end must also be involved.

Figure 3: The carboxyl-domains of Mitf control its nuclear localization and stability.

(A) Schematic of MITF-sp truncation constructs. C-term truncations were generated by introducing stop codons at position Q326 or L378 or by deleting fragments 326–377 or 316–326. MITF-sp-326* introduces a stop-codon at residue 326 and therefore contains the SUMo-site at 316; MITF-sp-Δ326–377 lacks the tentative activation domain AD3; MITF-sp-Δ316–326 lacks the SUMo-site and adjacent amino acids; MITF-sp-378* lacks the series of phosphorylation sites at the carboxyl-end of the protein.

(B) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced to overexpress the different MITF mutant proteins fusioned with Flag-tag at C terminus for 24 hours. MITF-WT, MITF-sl, MITF-sp-326*, MITFmi-sp-378*, and MITF-sp-Δ326–377 in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. Actin and γH2AX were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

(C) The intensities of the indicated pS73 MITF and S73 MITF proteins from the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of the western blot analysis in (B) were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(D) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced for 24 hours to overexpress the different MITF mutant proteins before treatment with TPA at 200nM for 1 hour. MITF-WT, MITF-sl, MITF-sp-326*, MITF-sp-Δ326–377, MITF-sp-Δ316–326, and MITF-sp-378* protein in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. Actin or GAPDH and γH2AX or H3K27me3 were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

(E) Intensities of the indicated pS73-MITF proteins from the western blot analysis in (D) in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from the cell treated with TPA were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(F) Western blot analysis of the MITF proteins from dox-induced A375P cells after treating them with 40 μg/ml CHX for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours. The MITF proteins were visualized by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(G) and (H) Non-linear regression (one-phase decay) and half-life analysis of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF proteins over time after CHX treatment. The MITF protein levels relative to T0 were calculated, and non-linear regression analysis was performed. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

The MITF-sl protein was more nuclear than the MITF-sp-326* and MITF-sp-378* proteins (Figures 3B and 3C), suggesting that the 316–326 domain must also be involved in regulating nuclear localization. However, the MITF-sp-Δ316–326 construct, which lacks the K316 SUMO-site and adjacent residues, did not alter the cytoplasmic-nuclear distribution of MITF (Figures S11C and S11D). This suggests that residues 326–419 contain a major signal for mediating nuclear export of MITF and that residues 316–326 also contribute. Intriguingly, the MITF-mi and MITF-ew proteins containing the 316*, 378*, or Δ316–326 mutations were more nuclear than their full-length counterparts (Figure S11E and S11F).

Previous work has shown that treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), an agent known to induce ERK kinase activity, leads to phosphorylation of S73 of MITF and shifts the protein to the cytoplasm10. Consistent with that, TPA treatment promoted S73 phosphorylation (as seen by the almost exclusive presence of the upper MITF-band) of MITF-WT and shifted the protein out of the nucleus (Figures 3D and 3E). The MITF-sl protein was also phosphorylated at S73 but, as before, it mostly stayed in the nucleus. The MITF-sp-Δ326–377, MITF-sp-Δ316–326, and MITF-sp-378* proteins were also phosphorylated at S73, but a large proportion of these proteins was located in the cytoplasm after TPA treatment. The MITF-sp-326* protein was equally distributed between the two compartments (Figures 3D and 3E). These data suggest that MITF has more than one nuclear export domain, one involving S73 and S69 and another located in the C-end, which may act independently. The LocNES algorithm39 predicts a couple of nuclear export signals (NESs) in the C-end of MITF spanning residues 350–366 (NES1) and 374–388 (NES2). To test their role, we generated a fusion of MITF-sl to either NES1 or NES2 or both NES1 and NES2 (schematic diagram in Figure S11G) in our inducible vector system and performed cell fractionation. All the fusions slightly increased the proportion of MITF-sl in the cytoplasm, regardless of S73 phosphorylation status (Figures S11H and S11I). Upon TPA treatment, pS73-MITF-sl-NES1, -NES2, and NES1-NES2 were significantly exported to the cytoplasm, as opposed to pS73-MITF-sl (Figures S11J and S11K). Our findings suggest that NES1 and NES2 are involved either in nuclear export of MITF or in blocking its import.

To determine which regions within the C-end of MITF are essential for mediating effects on stability, we performed protein stability assays using the MITF deletion constructs in the presence of CHX. The results showed that, again, the pS73 form of MITF-WT, MITF-sl, MITF-sp-326*, MITF-sp-Δ316–326, and MITF-sp-378* proteins was considerably more stable than the corresponding S73 proteins (Figures 3F–H). It also showed that the MITF-sp-326*, MITF-sp-378*, and MITF-sp-Δ316–326 proteins were less stable than the MITF-WT protein. However, MITF-sl still showed the most rapid degradation upon CHX treatment of all proteins tested (Figures 3F–H). The results suggest that the 316–326 and 378–419 domains are important for nuclear localization and MITF stability. The effects of the 378–419 domain on MITF localization are not due to a single phosphorylation site at the C-end since S384A, S397A, S401A, S405A, and S409A did not significantly affect the stability of MITF-sp, nor did their combination in the 4A mutant construct (Figures S11L and S11M).

To further investigate the role of the 316–419 domain in mediating MITF protein stability, we determined the stability of the non-DNA binding MITF-mi, MITF-mi-316*, MITF-ew, and MITF-ew-316* proteins. Although the pS73-MITF-mi and pS73-MITF-ew proteins were slightly more stable than pS73-MITF-WT, the stability of S73-MITF-mi and S73-MITF-ew did not significantly differ from MITF-WT (Figures S11N and S11O). Meanwhile, the double mutant proteins (i.e., MITF-mi-316* and MITF-ew-316*) exhibited increased presence in the nucleus (Figure S11E) yet had similar stability as MITF-WT (Figures S11P and S11Q). This suggests that the ability to bind to DNA in concert with MITF C-end might be important for controlling MITF stability and triggering the degradation process.

MITF is mainly degraded through a ubiquitin-mediated proteasome pathway in the nucleus.

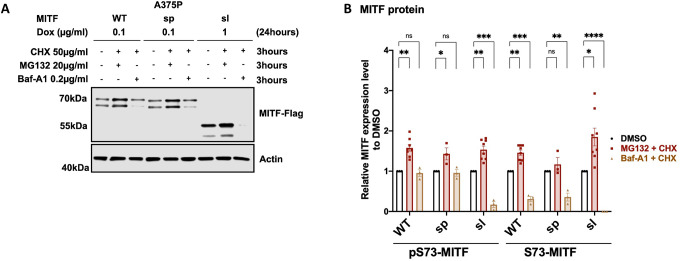

To determine which degradation pathway is responsible for MITF degradation, we treated the cells with the ubiquitin-proteasomal inhibitor MG132 and the lysosomal inhibitor Baf-A1 together with CHX for 3 hours. Treatment with MG132 and CHX increased the stability of the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins, whereas Baf-A1 and CHX treatment did not (Figures 4A and 4B). Treatment with MG132 or Baf-A1 without CHX showed a significant increase in the intensity of the pS73 band of the MITF-sp and MITF-sl proteins, though not MITF-WT protein (Figures 4C and 4D). Interestingly, the S73 bands of MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl showed a considerable increase after MG132 treatment (approximately 2.4-, 2.7-, and 6.7-fold increase respectively), but the increase was much less pronounced or even non-significant (in the case of S73-MITF-sl) upon Baf-A1 treatment (Figure 4D). This suggests that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is the primary degradation machinery for MITF.

Figure 4: MITF is mainly degraded through the proteasome pathway in the nucleus.

(A) Western blot analysis of the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins. Expression was induced for 24 hours in A375P cells treated with 50 μg/ml CHX in the presence of either DMSo or 40 μg/ml MG132 or 0.1 μg/ml Baf-A1 for 3 hours. The MITF protein was then visualized by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(C) Western blot analysis of the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl proteins. Expression was induced for 24 hours in A375P cells treated with either DMSo or 40 μg/ml MG132 or 0.1 μg/ml Baf-A1 for 3 hours. The MITF protein was then visualized by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(B) and (D) The indicated pS73- and S73-MITF protein band intensities from western blot analysis (A) and (C), respectively, were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted relative to DMSo. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

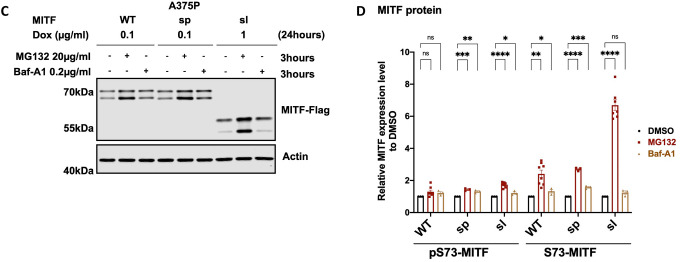

(E) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced to overexpress MITF-WT protein before treating with either 200nM TPA for 1 or 4 hours or 40 μg/ml MG132 for 3 hours or 200nM TPA for 1 hour and then adding 40 μg/ml MG132 for the next 3 hours. MITF-WT protein in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. GAPDH and γH2AX were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

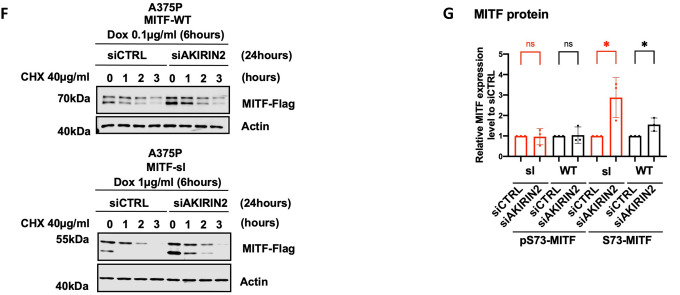

(F) Western blot analysis of the stability of the MITF-WT and MITF-sl mutant proteins after knocking down AKIRIN2, a key regulator of the nuclear import of proteasomes, for 24 hours and then inducing MITF expression using dox for 6 hours. The inducible A375P cells were treated with 40 μg/ml CHX for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours. The MITF proteins were then visualized by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(G) The intensities of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF protein bands were quantified from western blot analysis in (F) with ImageJ software and are depicted as relative protein expression to DMSo. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

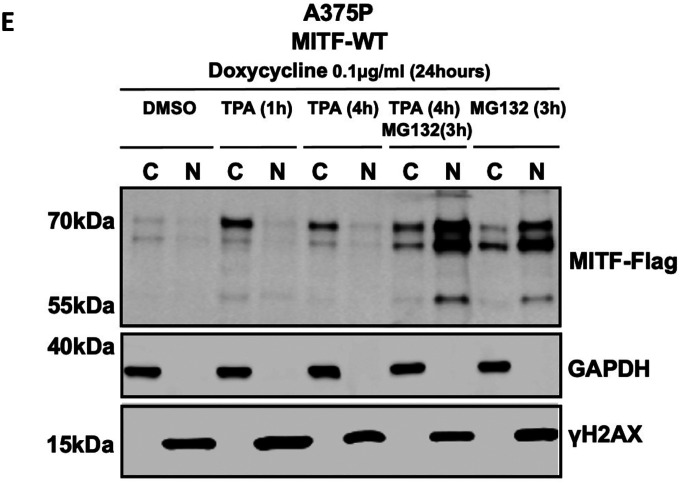

To test whether the proteasomal degradation pathway takes place predominantly in the nucleus or the cytoplasm, we treated MITF-WT expressing cells with both MG132 and TPA. As shown in Figure 4E, TPA treatment significantly increased the total MITF protein compared to vehicle controls, suggesting that shutting the protein out of the nucleus increases stability. Treating the cells for 3 hours with MG132 in the presence of TPA revealed a significant increase of MITF, primarily in the nucleus (Figure 4E).

Dox-inducible A375P melanoma cells expressing MITF-WT, MITF-sp, and MITF-sl were exposed to CHX and the nuclear export inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB)40 for different time points before harvesting for Western blotting. The results showed that the stability of pS73-MITF-WT and pS73-MITF-sp was significantly reduced upon LMB treatment, whereas the stability of S73 was not changed, and the stability of both pS73- and S73-MITF-sl was decreased upon LMB treatment (Figures S12A and S12B). AKIRIN2 is essential for proteasomal degradation in the nucleus, and we hypothesized that its removal would increase MITF stability41. We thus knocked down AKIRIN2 in our dox-inducible A375P cells expressing MITF-WT and MITF-sl prior to CHX treatment. After treating the cells for 24 hours with siAKIRIN2, the expression of the mRNA AKIRIN2 was significantly decreased (Figure S12C), and the expression of both S73-MITF-WT and S73-MITF-sl was significantly increased (Figures 4F, 4G, and S12D). Our results show that MITF is degraded in the nucleus through the proteasomal pathway. The increased nuclear presence of the MITF-sl protein may explain its reduced stability.

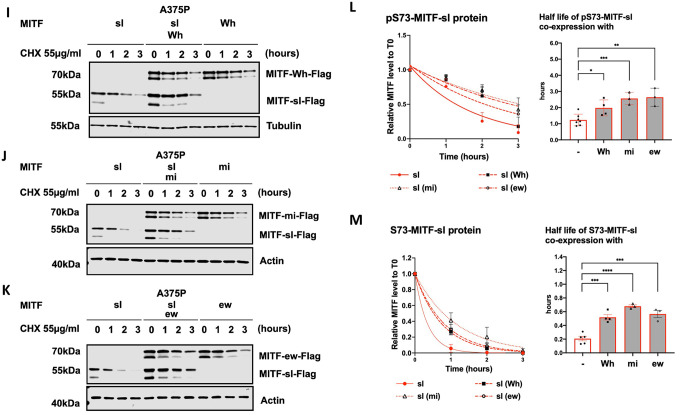

The K316R and E318K mutations together with the S409A mutation reduce MITF stability and increase its nuclear presence

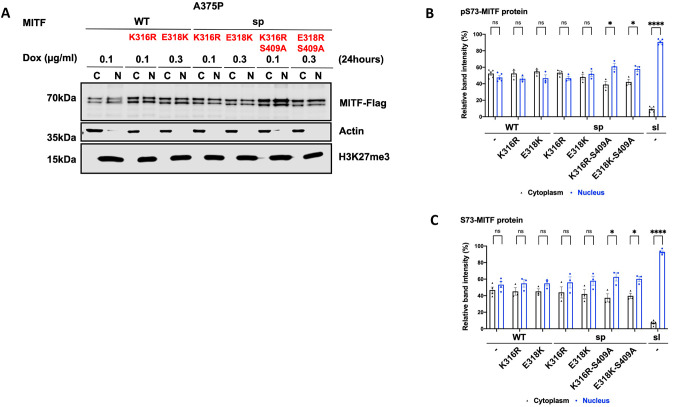

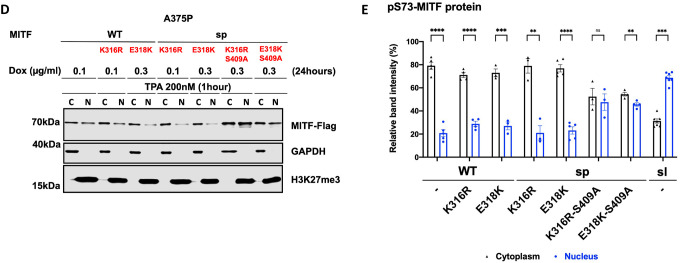

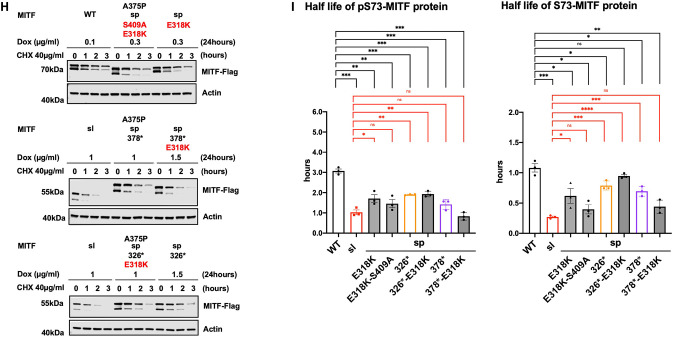

To determine if the SUMOylation site at K316 was involved in mediating MITF subcellular localization, we replaced the K316 residue with arginine in MITF-WT and MITF-sp. We also determined the effects of the E318K mutation since individuals carrying this mutation in MITF are predisposed to melanoma, and the mutation abolishes SUMOylation at K31616, 17. Alone, neither the K316R nor the E318K mutations altered the localization of the MITF-WT or MITF-sp proteins (Figures 5A–C). However, the double mutant proteins K316R-S409A and E318K-S409A were more nuclear, regardless of the S73-phosphorylation status (Figures 5A–C). Critically, both double mutants were able to override the effects of TPA on nuclear export, resulting in equal distribution between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figures 5D and 5E). However, the K316R and E318K mutations did not alter the nuclear localization of MITF or nuclear export upon TPA treatment when together with the S384A, S397A, S401A, or S405A mutations, (Figures S13A and S13B). Taken together, this suggests that a specific interaction between the SUMOylation site at K316 and the phosphorylation site at S409 is important for mediating MITF export. However, since these double mutants do not fully replicate the effects of the MITF-sl protein on localization, additional regions within the C-end must be important as well.

Figure 5: The interplay between SUMoylation at K316 and phosphorylation site at S409 in regulating MITF protein stability and localization.

(A) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced for 24 hours to overexpress the indicated MITF mutant proteins. The MITF proteins in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. Actin or GAPDH and H3K27me3 were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

(B) and (C) The intensities of the indicated pS73- and S73-MITF proteins in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from western blot analysis in (A) were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(D) Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions isolated from A375P melanoma cells induced for 24 hours to overexpress the indicated MITF mutant proteins before treatment with 200nM TPA for 1 hour. The mutant MITF proteins in cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were visualized using FLAG antibody. GAPDH and H3K27me3 were loading controls for cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

(E) The intensities of the indicated pS73-MITF proteins bands in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of the western blot analysis in (D) and (F), respectively, were quantified separately with ImageJ software and are depicted as percentages of the total amount of protein present in the two fractions. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

(F) and (H) Western blot analysis of the stability of the MITF proteins. The inducible A375P cells were treated with doxycycline for 24h to express the indicated mutant MITF proteins before treating them with 40 μg/ml CHX for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours. The MITF protein was then compared by western blot using FLAG antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

(G) and (I) Half-life analysis of the pS73- and S73-MITF proteins over time after CHX treatment. The MITF protein levels relative to T0 were calculated, and non-linear regression analysis was performed. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (Student’s t-test) are indicated by * p< 0.05, *p< 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.00, and ns not significant.

To clarify the role of the SUMOylation site on MITF protein stability, we tested the stability of the MITF-WT, MITF-sp, MITF-sp-378*, MITF-sp-326* proteins, and MITF-S409A in the presence of the K316R mutation. The pS73-MITF-WT-K316R and pS73-MITF-sp-K316R proteins were significantly more stable than pS73-MITF-WT; the stability of the S73-MITF-WT-K316R and S73-MITF-sp-K316R proteins was slightly but not significantly increased (Figures 5F and 5G). Interestingly, the pS73-MITF-sl protein was significantly less stable than the pS73-MITF-sp-326* protein (Figures 3F–H), whereas the stability of MITF-sp-378*-K316R was comparable to pS73-MITF-sl (Figures 5F and 5G). This suggests that in the presence of residues 326–419, the K316R mutation increases the stability of MITF, whereas in its absence, K316R mimics the effects of the MITF-sl mutation and reduces stability. Furthermore, the double mutation K316R-S409A appears to have a specific effect on the stability of the S73-MITF-sp protein. However, the stability of pS73-MITF-sp forms remained unaffected by this mutation.

We also determined the stability of MITF-sp, MITF-sp-326*, MITF-sp-378*, and MITF-sp-S409A constructs carrying the E318K mutation. The stability of these proteins was significantly reduced in the presence of the E318K mutation (Figures 5H–I). The MITF-sp-378*-E318K protein showed similar stability as MITF-sl (Figures 5H–I), whereas MITF-sp-326*-E318K and MITF-sp-326* proteins were equally stable and both more stable than MITF-sl, regardless of phosphorylation at S73 (Figures 5H–I). The E318K-S409A mutation resulted in reduced stability of both pS73- and S73-MITF-sp. Taken together, our findings suggest that the E318K mutation reduces the stability of MITF. Interestingly, the K316R and E318K single mutations have different effects on stability even though both eliminate SUMOylation at K316. We hypothesize that the carboxyl domain (aa 378–419) of MITF interacts with the SUMO-site at K316, determining the stability of MITF.

The carboxyl end IDRs are dynamic and are proximal to each other in the dimer

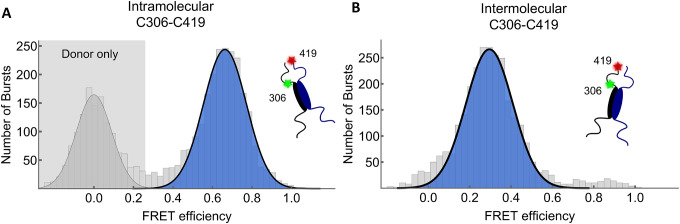

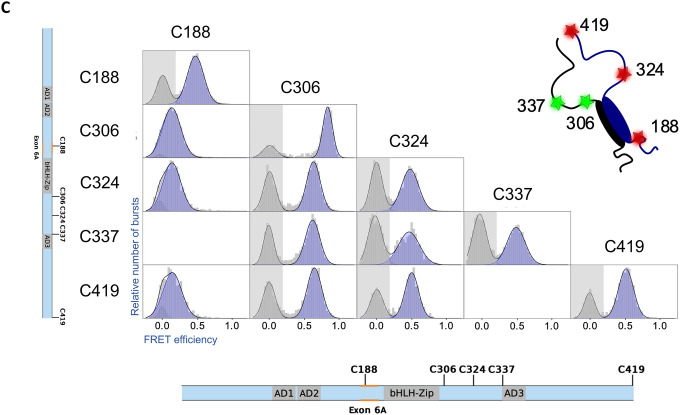

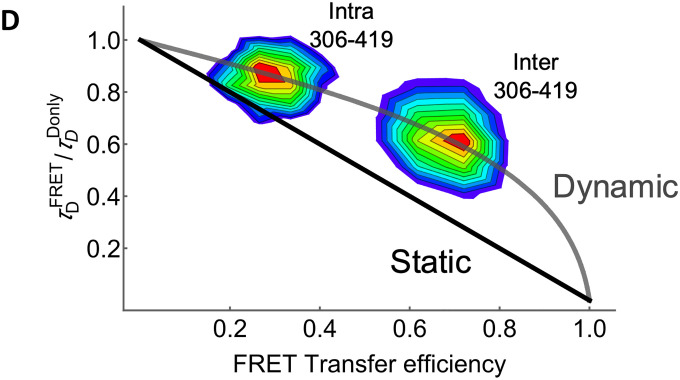

To probe the interactions between the regions containing the SUMOylation site at K316 and the phosphorylation site at S409, the distance between these domains was measured using smFRET42. To enable site-specific labeling, recombinant MITF constructs with only one or two native cysteines were used for inter- and intra-molecular FRET, respectively. When probed intramolecularly, the mean transfer efficiency, denoted as ⟨E⟩, between positions C306–C419 showed a slightly expanded chain with ⟨E⟩=0.30 (Figure 6A). However, when probed intermolecularly, C306–C419 showed a much higher mean transfer efficiency of ⟨E⟩=0.66 (Figure 6B), indicating that the S409 phosphorylation site of one chain is closer to the K316 SUMOylation region of its partner molecule than it is to its own K316 site. All intermolecular distances between different positions in the C-end region were consistently in proximity with mean transfer efficiencies of 0.48–0.85 (Figure 6C). These results suggest that crosstalk between the K316 SUMOylation and S409 phosphorylation region may be between the different monomers of MITF rather than within each monomer. Analysis of the donor fluorescence lifetimes shows that distances between and within the C-terminal IDRs are dynamic on the μs timescale, suggesting the C-terminal IDRs probably do not directly interact with each other to form stable tertiary structures (Figure 6D).

Figure 6: Inter- and intramolecular FRET indicates MITF C-end IDRs are proximal.

(A) and (B) Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer histograms of dimeric MITF fluorescently labeled at residues C306 and C419. Intermolecular FRET (A), fitted Gaussian population mean, E=0.66, and intramolecular FRET (B), fitted Gaussian population mean, E=0.3. (C) Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer histograms of MITF single-labeled pairs, labeled with acceptor or donor as indicated. FRET population fitted with a Gaussian distribution in blue with donor-only events in grey.

(D) Fluorescence lifetime analysis of inter- and intramolecular distances of the C-terminal IDR of MITF. The 2-D plot shows the lifetime of the donor in the presence of the acceptor (), relative to the donor fluorescence in its absence (), plotted against the FRET transfer efficiency for each burst. The solid black line shows the expected relationship for a static distance, while the grey line shows the expected relationship for a dynamic chain with a Gaussian distribution of distances.

Discussion

Suppressor mutation screening is an important approach to providing valuable information about gene function, molecular pathways, and protein-protein interactions43, 44. Suppressor screens are commonly performed in yeast, Drosophila, and C. elegans but rarely in mice or other mammals. Here, we generated a novel intragenic suppressor mutation at the Mitf locus in the mouse and showed that it is a re-mutation at the Mitf locus, which results in a truncation of the already mutated MITF-sp protein.

In the homozygous condition, the Mitfmi-sl mutation leads to brownish coat color compared to the normal black coat of Mitfmi-sp homozygotes. However, in compound heterozygous conditions with other Mitf mutations, including severe dominant-negative or loss-of-function mutations, the Mitfmi-sl mutation restores the coat color phenotype compared to combinations of the same alleles with the original Mitfmi-sp mutation. At the molecular level, we show that this suppressor mutation increases the nuclear localization of the MITF-sl protein and reduces its stability. The “brownish” phenotype of Mitfmi-sl homozygotes is likely to be due to the reduced stability of the MITF-sl protein and the consequent reduction in expression of some pigmentation genes, including Pmel, Tyrp1, and Mlana (Figure S7)45. Interestingly, mutations in Tyrp1 lead to mice with brown coat color. The total concentration of active MITF-sl protein in the nucleus at any given time will depend on the relationship between effects on nuclear import on the one hand and stability on the other hand. Expression of the MITF-partner proteins TFEB and TFE3 is limited in melanocytes, so they are likely to have negligible effects on MITF activity in the homozygous situation. Importantly, when the Mitfmi-sl mutation is combined with any of the various other Mitf mutations (Figures 1 and S1), its ability to dimerize and translocate its partner proteins (MITF-WT or mutant MITF) into the nucleus help to explain the suppressor effects of the Mitfmi-sl mutation. When in the nucleus, dimers between MITF-sl and any of the defective DNA-binding proteins MITF-Wh, MITF-mi, and MITF-ew slow down MITF-sl degradation but these dimers cannot bind DNA or activate gene expression4. Eventually, however, MITF-sl monomers will be released from their non-DNA-binding dimeric partner, thus leading to the formation of MITF-sl homodimers, which can bind DNA and regulate the expression of target genes. Here, the combined effects of nuclear import, rate of nuclear degradation, DNA binding, and dimerization properties are likely to determine the final outcome; the steady-state levels of nuclear MITF-sl are likely to be determined by the rate of heterodimer dissociation and rate of degradation. The near-normal coat color phenotype of Mitfmi-sl/Mitfmi compound heterozygotes suggests that together these effects result in almost full MITF activity during critical stages of melanocyte development and function. This is a novel mechanism of genetic suppression and may partly explain the normal phenotypes observed in humans carrying deleterious mutations on both alleles of genes46.

In addition to providing an explanation for the phenotypic outcome of the suppressor mutation, the mutation provides novel insights into how both stability and nuclear export of the MITF protein are regulated. Nuclear localization of MITF has been shown to involve a balance between import and export that depends on a number of domains, including a nuclear localization signal in the DNA-binding domain of MITF and an export signal that depends on the S69 and S73 phosphorylation sites10, 34 (Figure 1A). In wild-type cells, MITF is approximately equally distributed between the nucleus and cytoplasm as determined by western blotting, although, due to differences in nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes, it is more concentrated in the nucleus than in the cytoplasm, as evidenced by immunocytochemistry34. Our observations show that the C-end of MITF has major effects on nuclear localization and that residues 316–326, 350–366, and 374–419 are major factors in mediating the nuclear export of MITF. Interestingly, simultaneously mutating the SUMO-site at K316 and the phosphorylation site at S409 increased the nuclear localization of MITF compared to either single mutant alone, suggesting that these two post-translational modifications are necessary for nuclear export. Importantly, the effects of the nuclear export signal mediated by the S73 and S69 phosphorylation10 are less efficient when missing the C-end.

Our results show that MITF is mainly degraded through a nuclear ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation pathway. Again, the effects on stability are mainly mediated by the domains encoded by residues 316–326 and 378–419 where K316 and S409 play an important role. However, since all our deletion constructs showed some effect, most regions within the C-domain seem to affect protein stability. This suggests that the entire domain may be important, as is often observed for IDRs. Since the MITF-sl protein is quickly degraded in the nucleus, it is likely that truncation at the C-end activates a degradation signal. A degron motif was recently discovered in the amino end of the A isoform of MITF47, but as this is not present in the melanocyte-specific M-isoform studied here, the degradation signal must be located elsewhere in the protein. The fact that the effects on nuclear localization and stability are primarily encoded by the same domains suggests that these events may be related. The effects on nuclear localization are likely dominant since the protein will be degraded by the nuclear proteasome machinery if located in the nucleus. As another layer of regulation, when in the nucleus, MITF stability will also further be regulated by other factors, including SUMOylation at K316 and phosphorylation at S409; DNA binding may also be important, potentially by mediating structural changes. However, how DNA binding contributes to MITF-sl stability is not clear. Importantly our work suggests that the interaction between the SUMOylation site at K316 and the phosphorylation site at S409 is important for regulating MITF localization and stability. Our smFRET results show that these two regions are near each other in space, suggesting that direct interactions between the different protomers are involved.

In contrast to previous literature48, our work shows that the S73 form of MITF-WT is much less stable than the pS73 form. In our model, there is an almost 3-fold difference between the two forms. Interestingly, the Mitfmi-sl mutation reduced the stability of both the pS73 and S73 forms of MITF about 3-fold in each case (Figures 2B and 2C), suggesting that the effects of the C-end on stability are independent of the effects of pS73. It is possible that the difference between the pS73 and S73 forms is due to continuous phosphorylation of the S73-form, possibly mediated by doxycycline treatment, thus affecting the ratio between the two forms of the protein and leading to nuclear export. The observation that pS73-MITF is exported from the nucleus10 suggests that the kinetics of S73 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation may determine subcellular location and thus mediate protein stability. Currently, there is limited information on the kinetics or pathways involved.

Independent reports have shown that the E318K variant in human MITF predisposes to melanoma17, 49. This variant alters an essential residue in the SUMOylation motif ΨKXD/E which includes K316, the actual SUMOylation site. We show that the E318K mutant protein, which cannot be SUMOylated at this site, exhibits normal nuclear localization. However, when the S409A mutation is also present, the protein is more nuclear, regardless of S73 phosphorylation status. The E318K mutation resulted in reduced MITF stability both in the presence and absence of the S409A mutation. S409 has been suggested to be phosphorylated by the MAP-kinase p90Rsk48 or by AKT50. The gain-of-function BRAFV600E mutation and loss-of-function PTEN mutations might accelerate the p90Rsk or AKT kinase activity, respectively, and promote S409 phosphorylation. These effects might promote cytoplasmic retention of MITF-E318K, which subsequently would increase the stability of MITF and maintain the level of MITF protein at steady-state levels. Thus, depending on environmental signals (e.g., sun exposure), the medium-risk allele E318K16, 17 may mediate disease predisposition.

Based on our data, we propose a model where the two regions of the C-end of MITF, the SUMOylation site at K316 and the phosphorylation site at S409, are impacted by SUMOylation and phosphorylation, leading to effects on nuclear localization and stability. In the absence of SUMOylation at K316 and phosphorylation at S409, these residues are close in space and may collapse around the zipper domain, thus hiding nuclear export signals while at the same time exposing degradation signals. However, SUMOylation and phosphorylation may change the conformation leading to an extended version of the C-end, thus exposing nuclear export and hiding degradation signals. Although the signals which mediate SUMOylation of K316 and phosphorylation of Ser409 are presently not clear, it has been reported that the unphosphorylated S409 MITF is required to maintain the association of MITF and PIAS3, which enables SUMOylation at K31613, 51. This may represent a feedback loop to limit the activity of MITF at any given time based on environmental signals. We, therefore, conclude that generating suppressor mutations in the mouse is an exciting and feasible option for studying gene function and may reveal unexpected aspects of protein function and regulation, leading to novel insights into protein activities in the living organism.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains used, mutagenesis and genotyping:

The following Mitf mutants were used in this study: C57BL/6J-Mitfmi-sp, C57BL/6J-Mitfmi-eyeless white (Mitfmi-ew), NAW-Mitfmi-ew, C57BL/6J-MitfMi-Wh, C57BL/6J-Mitfmi-red-eyed white (Mitfmi-rw), C57BL/6J-Mitfmicrophthalmia (Mitfmi), 82UT-Mitfmi-Oak ridge (MitfMi-Or), C57BL/6J-MitfMi-or, 82UT-Mitfmi-brownish (Mitfmi-b) and a [C3H/C57BL/6J]-Mitfmi-vga−9 (Table 1). The Mitfmi-ew mutation arose on the NAW background52, and the MitfMi-Or mutation on the 82UT background53 both were subsequently backcrossed for 10 generations to C57BL/6J. To screen for Mitf suppressor mutations, homozygous B6-Mitfmi-sp males were treated four times at one-week intervals with 100 mg/kg ENU. After a 6–8-week recovery period, the males were mated to NAW-Mitfmi-ew/Mitfmi-ew females. The resulting offspring, which all should show an identical phenotype, were screened for abnormally pigmented deviates. DNA-HPLC was used to confirm the presence of the Mitfmi-sp mutation.

Cell culture, reagents, and antibodies:

Melanocyte cultures were obtained from trypsin-digested P0–P3 skin using microscopic selection of pigmented cells. Neural crest cultures were prepared following the previously described protocol54. The number of pigmented melanocytes was counted for each mutant in four independent cultures. MITF-positive cells were detected by immunofluorescence using the C5 anti-MITF antibody and anti-mouse FITC secondary antibody.The cell lines HEK293, A375P (CRL-3224), and SkMel28 (HTB-72) were purchased from ATCC. 501Mel melanoma cells were obtained from the lab of Dr. Ruth Halaban (Yale University). The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, #5240025) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco #10270–106) at 5% CO2 and 37oC in a humidified incubator. Cycloheximide (CHX – 50 mg/ml) (Sigma, #66819), 20 mg/ml MG132 (Sigma, #474790), 10 mg/ml Doxycycline (Dox – Sigma, #324285), 10 mg/ml TPA (Merck, #P1585), 1mg/ml Baf-A1 (Merk, #88899–55-2), 5 mM Leptomycin B (Merk, #L2913), 5 mM PLX4032 (Selleckchem, #S1267) stock solutions were prepared in DMSO. The primary antibodies used for all western blot (WB) experiments and their dilutions were as follows: Anti-FLAG (Sigma, #F3165) at 1:5000 dilution; Anti-β-Actin (Cell Signaling, #4970) at 1:1000 dilution; Anti-γH2AX (Abcam, #ab2251) at 1:2000 dilution, Anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, #5174), at 1:1000 dilution; Anti-H3K27me3 (Cell Signaling, #9733) at 1:1000 dilution; Anti-GFP (Abcam, #ab290) at 1:2500 dilution.

Generation of plasmid constructs for stable doxycycline-inducible overexpression:

Fusions of wild-type and mutant mouse MITF-M cDNA with the 3XFLAG-HA tag at the C- or N-terminus or fusion with the GFP-tag at the C terminus were generated in the piggy-bac vector pPB-hCMV1. The cDNAs were subcloned downstream of a tetracycline response element (TRE) using the Gibson Assembly Cloning kit (New England Biolabs, # E5510S). Mutations were introduced by in vitro mutagenesis using Q5 Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, #E0554S) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of stable doxycycline-inducible MITF:

Inducible A375P, SKmel28, and 501Mel cells were generated as described before55. Briefly, the wild-type and mutant mouse MITF fusion constructs with the 3XFLAG-HA at the C- or N-terminus or fusion with GFP at C-terminus or a pPB-hCMV1-EV-3XFLAG-HA empty vector was transfected into 70–80% confluent A735P, 501Mel or SKMel28 cells using Fugene HD reagent (Promega, #E2311) together with the py-CAG-pBase and pPB-CAG-rtTA-IRES-Neo plasmids at a 10:10:1 ratio. After 48 hours of transfection, the transfected cell lines were selected with 0.5 mg/ml of G418 (Gibco, #10131–035) for two weeks. A ‘mock plate’ of no transfected cells was also included in each case. To equalize the expression of MITF proteins, the dox-inducible A375P, 501Mel, and SKmel28 melanoma cell lines were treated with varying concentrations of doxycycline, and the doxycycline concentrations leading to similar MITF protein levels were used for future experiments.

Incucyte live cell imaging:

Dox-inducible A375P melanoma cells overexpressing MITF-WT, MITFmi-sp, and MITFmi-sl were seeded at 2000 cells per well in triplicate onto a 96-well cell culture plate (Falcon 96-well Clear Flat Bottom TC-treated Culture Microplate, CORNING, Cat#353072). Images were recorded with Incucyte S3 Live-Cell Analysis System (Sartorius, Essen BioScience) every 2 hours for four days. Collected images were then analyzed using the Incucyte software by measuring the percentage of cell confluency.

qRT-PCR and sequencing:

Total RNA was isolated from hearts of wild type and mutant mice using the RNAwiz kit (ThermoFisher, #Am1925). The RNA was reverse transcribed by SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and the resulting cDNA phenol/chloroform was extracted. Alternatively, RNA was isolated using the Macherey Nagel RNAII kit. The entire Mitf cDNA was amplified by PCR using overlapping primers. The resulting PCR products were sequenced directly using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (ABI) and the ABI 377 sequencer.

The day before inducing MITF expression by doxycycline, cells were seeded on 12-well plates at a density of 12×104 cells per well. MITF expression was induced for 6, 12, 24, and 36 hours and harvested for RNA isolation using TRIzol reagent (ThermoFisher, #15596–026) High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, #4368814) was used for cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The SensiFAST SYBR Lo-ROX Kit (Bioline, #BIO-94020) was utilized for the qRT-PCR. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using 0.4 ng/μl cDNA in triplicates. The relative foldchange in gene expression was calculated using the D-ΔΔCt method56. The geometrical mean of β-actin and hARP expression was used to normalize the target gene expression.

Subcellular fractionations:

The day before inducing MITF expression by doxycycline, cells were seeded on 6-well plates at a density of 3.5×105 cells per well for 24 hours, after which the cells were either directly harvested or treated with TPA at 200nM for 1 hour, 4 hours, or treated with TPA at 200nM for 1 hour and MG132 40 μg/ml for the next 3 hours in the presence of TPA before harvesting by trypsinization. Cells were washed with PBS before washing twice with swelling buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors). The cells were then lysed by incubation at 4°C for 15min in cell lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1% NP40). Approximately 30% of the sample was collected and set aside as whole cell lysate. The remaining cell lysate was spun down at 3000 rpm for 5min at 4oC, and the supernatant was collected as the cytoplasmic fraction. At the same time, the pellet, representing the nuclear fraction, was washed with cold PBS before resuspension in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% (v/v) NP40, 0.5% (m/v) sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% (m/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors) for further experiments including Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation:

Cells were seeded on 6-well plates at a density of 3.5×105 cells per well the day before transfection. The following day, FuGENE HD reagent (Promega # E2311) was used to conduct the co-transfection of MITF-WT, MITFmi-sp or MITFmi-sl-GFP-tagged constructs together with MITFmi, MITFmi-ew, MITFMi-Wh, 14–3-3-Epsilon or 14–3-3-zeta Flag-tagged proteins. After 24 hours, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed by adding 200 μl of RIPA buffer with freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The cell lysate was then ready for immunoprecipitation (IP); 30% of the sample was collected as an input fraction.

For each IP sample, 20 μl of Dynabeads Protein G magnetic beads (Invitrogen, # 10004D) were washed twice with 1ml PBS using a magnetic stand before resuspending in 300 μl of PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20. The magnetic beads were then conjugated with anti-FLAG antibodies by adding 1 μg anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, #F3165), followed by a 30-minute incubation at RT with rotation. The magnetic beads were washed twice with PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20 to eliminate non-conjugated antibodies and then resuspended with 20 μl of PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20. The IP samples were incubated with the coated beads overnight at 4°C with rotation. Samples were then placed on the magnetic stand, and supernatants were removed and saved as an unbound fraction (UnB) in each case. The beads were washed twice with 1ml PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20. The protein was eluted from the beads by incubating with 150 ng/μl 3X Flag peptide in PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20 for 30 minutes at 4°C with rotation. The samples were placed on the magnetic stand, and supernatants were saved as an immunoprecipitation fraction (IP). The collected fractions were then subjected to Western blot analysis.

EMSA DNA binding studies:

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays were performed using proteins expressed in the TNT T7 Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega, WI), according to the manufactureŕs recommendation. DNA binding reactions were performed in 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% ethylene glycol, and 5% glycerol. Ten μL of 2X buffer were combined with 2.5 μL of TNT translated MITF protein, 1.4 ng of labeled probe (5’-AAAGTCAGTCATGTGCTTTTCAGA-3’), 4 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA)57 and water, adjusting the reaction volume to 20 μL. For supershifts, 0.5 μL of C5-monoclonal MITF antibody (Neomarkers) was added to the reaction. The samples were incubated on ice for 30 minutes to allow binding to proceed. The resulting DNA-protein complexes were resolved on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels, placed on a storage phosphor screen, and scanned on a Typhoon Phosphor Imager 8610 (Molecular Dynamics) for analysis.

Protein degradation assay:

The dox-inducible A375P cells were treated with doxycycline to express MITF WT and MITF mutant proteins for 24 hours and then treated with 40 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma #66819), in presence or absence of 200nM TPA, 2μM PLX, or 5nM LMB for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours before harvesting. For protein degradation pathway analysis, the dox-inducible A375P cells were treated with doxycycline to express the respective MITF constructs for 24 hours at density of 8×104 cells and then treated with either 40 μg/ml MG132 or 2 μg /ml Bafa1 in the presence or absence of 40 μg/ml CHX for 3 hours before harvesting. FuGENE HD reagent (Promega, #E2311) was used for the co-transfection. After 24 hours, the cells were treated with 55 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma, #66819) for 0, 1, 2, and 3 hours. The cells were finally lysed in SDS sample buffer (2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 63 mM Tris-HCl, 0.0025% bromophenol blue, pH 6.8), and the expression of the MITF protein determined by Western blot using FLAG antibodies.

Western blot analysis: