Abstract

BACKGROUND: Chronic migraine (CM) is a common neurologic disorder that imposes substantial burden on payers, patients, and society. Low rates of persistence to oral migraine preventive medications have been previously documented; however, less is known about persistence and costs associated with innovative nonoral migraine preventive medications.

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate real-world persistence and costs among adults with CM treated with onabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA) or calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies (CGRP mAbs).

METHODS: This was a retrospective, longitudinal, observational study analyzing the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare databases. The study sample included adults with CM initiating treatment with either onabotA or a CGRP mAb on or after January 1, 2018. Persistence and costs over 12 months after treatment initiation were evaluated using chi-square and Student’s t-tests. Persistence to onabotA was compared with CGRP mAbs as a weighted average of the class and by individual CGRP mAbs. Mean pharmacy (acute and preventive), medical (inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient), and total costs are reported. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to generate adjusted estimates of persistence and costs after controlling for potential confounders (age, sex, region, insurance type, number of baseline comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and number of previously used oral migraine preventive medications).

RESULTS: Of 66,303 individuals with onabotA or CGRP mAb claims, 2,697 with CM met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In the total population, individuals were primarily female (85.5%), lived in the South (48.5%), and had a mean (SD) age of 44 (12) years, which was consistent across the onabotA and CGRP mAb cohorts. Common comorbid conditions included anxiety (23.9%), depression (18.2%), hypertension (16.5%), and sleep disorders (16.9%). After adjusting for potential confounding variables, persistence to onabotA during the 12-month follow-up period was 40.7% vs 27.8% for CGRP mAbs (odds ratio [OR] = 0.683; 95% CI = 0.604-0.768; P < 0.0001). Persistence to erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab was 25.5% (OR = 0.627; 95% CI = 0.541-0.722; P < 0.0001), 30.3% (OR = 0.746; 95% CI = 0.598-0.912; P = 0.0033), and 33.7% (OR = 0.828; 95% CI = 0.667-1.006; P = 0.058). All-cause ($18,292 vs $18,275; P = 0.9739) and migraine-related ($8,990 vs $9,341; P = 0.1374) costs were comparable between the onabotA and CGRP mAb groups.

CONCLUSIONS: Among adults with CM receiving onabotA and CGRP mAbs, individuals initiating onabotA treatment had higher persistence compared with those receiving CGRP mAbs. Total all-cause and migraine-related costs over 12 months were comparable between those receiving onabotA and CGRP mAbs.

DISCLOSURES: This study was sponsored by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie), they contributed to the design and interpretation of data and the writing, reviewing, and approval of final version. Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Dennis Stancavish, MS, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by AbbVie. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. The authors received no honorarium/fee or other form of financial support related to the development of this article.

Dr Schwedt serves on the Board of Directors for the American Headache Society and the American Migraine Foundation. Within the prior 12 months he has received research support from Amgen, Henry Jackson Foundation, Mayo Clinic, National Institutes of Health, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, SPARK Neuro, and US Department of Defense. Within the past 12 months, he has received personal compensation for serving as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Allergan, Axsome, BioDelivery Science, Biohaven, Collegium, Eli Lilly, Ipsen, Linpharma, Lundbeck, and Satsuma. He holds stock options in Aural Analytics and Nocira. He has received royalties from UpToDate. Dr Lee and Ms Shah are employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock. Dr Gillard was an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock. Dr Knievel has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Biohaven; conducted research for AbbVie, Amgen, and Eli Lilly; and is on speaker programs for AbbVie and Amgen. Dr McVige has served as a speaker and/or received research support from Allergan (now AbbVie Inc.), Alder, Amgen/Novartis, Avanir, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, and Teva. Ms Wang and Ms Wu are employees of Genesis Research, which provides consulting services to AbbVie. Dr Blumenfeld, within the past 12 months, has served on advisory boards for Allergan, AbbVie, Aeon, Alder, Amgen, Axsome, BDSI, Biohaven, Impel, Lundbeck, Lilly, Novartis, Revance, Teva, Theranica, and Zosano; as a speaker for Allergan, AbbVie, Amgen, BDSI, Biohaven, Lundbeck, Lilly, and Teva; as a consultant for Allergan, AbbVie, Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Teva, and Theranica; and as a contributing author for Allergan, AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Novartis, Lilly, and Teva. He has received grant support from AbbVie and Amgen.

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the United States and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvieclinicaltrials.com/hcp/data-sharing/.

Plain language summary

Individuals living with chronic migraine who started preventive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA were more likely to continue treatment compared with those starting calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody treatment. The total health care costs were similar for all patients.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

Results from this study demonstrate that initiating preventive migraine treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with a higher rate of persistence than initiating preventive migraine treatment with a calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody, although the costs were comparable. These results are expected to help payors make better informed decisions on formulary development for branded preventive treatments in chronic migraine.

Migraine is the most frequently occurring neurologic disorder in the United States, with approximately 40 million people experiencing migraine and approximately 1.3%-4.1% of the overall US population experiencing chronic migraine (CM).1-3 Episodic migraine (EM) is characterized by individuals experiencing fewer than 15 headache days per month, whereas CM is characterized by individuals experiencing at least 15 headache days per month for more than 3 months, of which at least 8 days per month are migraine days.4,5 Migraine imposes a substantial economic burden for payers, patients, and society, accounting for an estimated $30 billion annually in direct and indirect health care costs in the United States.6

Several oral migraine preventive medications (OMPMs) are used for the preventive treatment of migraine, including anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antihypertensives.7 However, among individuals with CM there is low adherence and tolerability of OMPMs, with worsening persistence as individuals cycle through different OMPMs.8

Recently approved medications for the preventive treatment of migraine might address some of the efficacy and tolerability issues seen with OMPMs.9 OnabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA) was approved in October 2010 for the preventive treatment of CM.10 Additionally, several calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies (CGRP mAbs), including erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab, were approved between May and September 2018 for the preventive treatment of migraine.11-13 The CGRP mAbs offer a novel therapeutic approach to migraine, and their efficacy has been demonstrated in clinical trials of individuals with EM and CM.14-18

In the current study, we evaluated the real-world persistence and costs among adults with CM treated with onabotA or CGRP mAbs (erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) in the first year after treatment initiation.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

This was a retrospective cohort study using medical claims data, pharmacy claims data, and enrollment information from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental databases from July 1, 2017, through February 29, 2020 (Supplementary Figure 1, available in online article). Patients diagnosed with CM and treated with onabotA, erenumab, fremanezumab, or galcanezumab were analyzed. All definitions of variables used to identify study cohorts and outcomes were measured based on inpatient medical, outpatient medical, and outpatient pharmaceutical data using enrollment records; service dates; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes; Current Procedural Technology, Fourth Edition, codes; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes; and National Drug Code (NDC) numbers.

The Commercial Claims and Encounters section of the IBM MarketScan database contains fully adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims for more than 225 million unique patients from 300 contributing employers and 40 contributing health plans across the United States, representing approximately 62.9 million covered lives per year. Additionally, since 1995, MarketScan Medicare Supplemental Data are available and represent 6.4 million lives containing enrollment and health care claims of retirees and disabled persons with Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap coverage) and Medicare (captured in Coordination of Benefits Amount), as well as 9.3 million lives with Medicaid coverage. The Medicare Supplemental Database allows for a comprehensive and longitudinal view of the insured older adult population.

STUDY SAMPLE

The study sample comprised individuals aged at least 18 years with at least 1 prescription claim of a CGRP mAb (the NDC numbers are included in Supplementary Table 1) or 1 administration claim of onabotA (the HCPCS code is included in Supplementary Table 1) with a CM diagnosis (ICD-10-CM code G43.xxx) after January 1, 2018. The first date associated with an index treatment claim and no previous claims in the past 6 months was considered the index date.

Patients were required to have continuous insurance plan enrollment for at least 6 months prior to the index date (baseline period) and at least 12 months post-index date (follow-up period) and a CM diagnosis within the 6 months on or prior to the index date. Patients were excluded from the study if they initiated more than 1 CGRP mAb or onabotA on the index date, had any claims for onabotA or a CGRP mAb within the baseline period, had a diagnosis claim for an onabotA indication other than migraine at any time in the study period, or had an NDC number for onabotA in the follow-up or baseline period for the onabotA group.

OUTCOMES

The primary outcomes of the study were persistence, all-cause costs, and migraine-related costs over a 12-month period. Secondary outcomes included persistence over 6-month and 9-month follow-up periods. Additional treatment patterns were assessed as exploratory outcomes. Outcome definitions are described below.

Persistence. Persistence rates for onabotA, individual CGRP mAbs (erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab), and CGRP mAbs (as a weighted average of the therapeutic class) were evaluated at 12 months. Treatment persistence was defined as continuous treatment with no gaps greater than 30 days from the end of a fill/administration date plus days supply and the next chronological fill/administration date. Early refills were accounted for by adding the overlapping days supply to the end of the next fill/administration date plus days supply. Individuals were considered to have been nonpersistent if there was not a subsequent prescription or administrative claim within 30 days after the end of the previous prescription coverage or if the subsequent prescription or administrative claim was more than 30 days after the end of the previous prescription coverage (Supplementary Figure 2).8 Individuals who initiated a CGRP mAb were also considered nonpersistent if they switched to a different CGRP mAb. The secondary outcomes included persistence rates at 6 and 9 months.

Costs. All-cause and migraine-related costs were evaluated for onabotA or CGRP mAbs (as a weighted average of the therapeutic class). Costs were calculated during the 12-month follow-up period and during the 6-month baseline period. Medical costs were evaluated as the total medical costs and further evaluated as inpatient, emergency department (ED), and outpatient costs. Pharmacy costs were evaluated as the total pharmacy costs and individually as the acute and preventive pharmacy costs. Migraine-related costs were defined as costs with a migraine diagnosis in any position and treatment-related costs for onabotA, CGRP mAbs, and acute and preventive treatments.

Treatment Patterns. Treatment patterns were further characterized among patients who did not have continuous index treatment (ie, those who had a gap >30 days) into the following groups: re-initiation of the index treatment, addition of another treatment, switch to another treatment, and discontinuation without a switch to another treatment. Re-initiation of the index treatment occurred when an individual was considered to not have maintained continuous index treatment throughout the entire follow-up period but was actively being treated with index therapy within 30 days from the last day of follow-up. The addition of another treatment occurred when an individual initiated a different branded treatment other than the index treatment while still being continuously treated with the index treatment. Additions must have been initiated at least 28 days prior to the end of continuous index treatment and must have had an overlap for at least 28 days. Additions were not permitted between 2 different CGRP mAbs. Switching to another treatment occurred when an individual initiated a different CGRP mAb other than the index CGRP mAb within 28 days before or any time after the end of the continuous index treatment. If the nonindex treatment initiation occurred prior to the end of the continuous index treatment, it must have extended past the end of the continuous index treatment to have been considered a switch. Discontinuation without switch to another treatment occurred when an individual had neither a switch nor an addition and was not actively being treated with the index treatment within 30 days from the last day of follow-up. The discontinuation date was defined as the last day of any index treatment.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All study variables were analyzed descriptively using the onabotA group as the reference. Means and SDs were reported for continuous variables, and Student’s t-tests were used to detect differences. Percentages were reported for categorical variables, using chi-square tests to detect differences.

For persistence rates, generalized linear models were used for multivariate analyses. The following demographic and baseline characteristics were included in the model: age (continuous); age2; sex; region; insurance type; number of baseline comorbidities; Charlson Comorbidity Index; and number of prior OMPMs (categorical), including β-blockers, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers. Age2 was included as a variable to account for the peaking of disease severity during middle age as opposed to contrasting disease states in which greater age may be associated with greater disease severity. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were calculated for individual CGRP mAbs and the total CGRP mAb group compared with the onabotA group.

For costs, generalized linear models with gamma distribution (assigning $1 to patients with $0 cost) and log link were used to estimate the mean cost for onabotA- and CGRP mAb–treated individuals along with the mean ratio and 95% CI.19,20 In addition to the demographics and baseline characteristics listed above, baseline all-cause/migraine-related costs were adjusted for in the costs model. All costs were inflation-adjusted to 2022 US dollars. Because of the small sample size and a large proportion of zeros in costs (Supplementary Table 2), Tweedie regression analyses21 were used to generate P values for inpatient, ED, acute medication, and preventive medication costs.

For all the adjusted models, P values and 95% CIs between the onabotA group and the CGRP mAb group were reported without adjusting for multiplicity.

Results

STUDY POPULATION

A total of 66,303 individuals who received a migraine-related onabotA administration or CGRP mAb prescription on or after January 1, 2018, were identified. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2,697 adults with CM were eligible for enrollment in the final cohorts (Supplementary Table 3). A large percentage of patients were excluded because of noncontinuous enrollment.

Most individuals were female (85.5%), lived in the South (48.5%), and had a mean (SD) age of 44 (12) years (Table 1). Common comorbid conditions included anxiety (23.9%), depression (18.2%), hypertension (16.5%), and sleep disorders (16.9%). A total of 2,222 (82.4%) and 2,256 (83.6%) individuals received acute medication and prior preventive medications at baseline, respectively. The most common prior acute medications were triptans (64.0%), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (32.2%), and opioids (21.3%); the most common classes of prior preventive medications were antidepressants (60.7%), anticonvulsants (52.9%), and β-blockers (23.5%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (N = 2,697) | OnabotulinumtoxinA (n = 1,455) | Erenumab (n = 798) | Fremanezumab (n = 233) | Galcanezumab (n = 211) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 44 (12) | 44 (12) | 44 (12) | 45 (11) | 43 (12) |

| Sex, (%) n | |||||

| Female | 85.5 (2,307) | 87.1 (1,267) | 82.7 (660) | 87.1 (203) | 83.9 (177) |

| Male | 14.5 (390) | 12.9 (188) | 17.3 (138) | 12.9 (30) | 16.1 (34) |

| Region, % (n) | |||||

| Northeast | 12.1 (327) | 10.8 (157) | 16.2 (129) | 7.3 (17) | 11.4 (24) |

| North Central | 22.7 (611) | 24.7 (359) | 21.1 (168) | 19.3 (45) | 18.5 (39) |

| South | 48.5 (1,309) | 46.9 (683) | 47.0 (375) | 57.9 (135) | 55.0 (116) |

| West | 16.5 (444) | 17.5 (255) | 15.3 (122) | 15.5 (36) | 14.7 (31) |

| Unknown | 0.2 (6) | 0.1 (1) | 0.5 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.5 (1) |

| Database, % (n) | |||||

| Commercial | 98.6 (2,659) | 98.1 (1,427) | 99.1 (791) | 99.6 (232) | 99.1 (209) |

| Medicare | 1.4 (38) | 1.9 (28) | 0.9 (7) | 0.4 (1) | 1.0 (2) |

| Baseline comorbidities,a % (n) | |||||

| Anxiety | 23.9 (345) | 25.0 (364) | 22.8 (182) | 22.8 (53) | 21.8 (46) |

| Depression | 18.2 (491) | 19.2 (279) | 17.3 (138) | 16.3 (38) | 17.1 (36) |

| Hypertension | 16.5 (445) | 16.0 (232) | 17.0 (136) | 17.2 (40) | 17.5 (37) |

| Asthma | 7.2 (194) | 7.6 (110) | 5.4 (43) | 11.6 (27) | 6.6 (14) |

| Diabetes | 5.7 (155) | 6.8 (99) | 4.1 (33) | 4.3 (10) | 6.2 (13) |

| Sleep disorders | 16.9 (459) | 17.3 (251) | 14.9 (119) | 19.3 (45) | 9.4 (41) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 0.26 (0.79) | 0.27 (0.8) | 0.24 (0.75) | 0.27 (0.61) | 0.25 (0.74) |

| Acute prescription medication use, % (n) | |||||

| Triptans | 64.0 (1,725) | 60.1 (875) | 67.9 (542) | 66.1 (154) | 73.0 (154) |

| NSAIDs | 32.2 (868) | 32.0 (465) | 32.6 (260) | 33.0 (77) | 31.3 (66) |

| Opioids | 21.3 (574) | 22.1 (322) | 21.6 (172) | 18.9 (44) | 17.1 (36) |

| Ergotamines | 1.6 (44) | 1.5 (22) | 1.9 (15) | 0.9 (2) | 2.4 (5) |

| Butalbital-containing medications | 13.9 (376) | 14.7 (214) | 12.0 (96) | 12.0 (28) | 18.0 (38) |

| Preventive prescription medication use, % (n) | |||||

| β-blockers | 23.5 (633) | 24.1 (351) | 24.2 (193) | 18.9 (44) | 21.3 (45) |

| Anticonvulsants | 52.9 (1,426) | 53.7 (781) | 52.8 (421) | 50.6 (118) | 50.2 (106) |

| Antidepressants | 60.7 (1,637) | 62.0 (902) | 57.1 (456) | 63.5 (148) | 62.1 (131) |

| ACE inhibitors | 5.2 (141) | 5.2 (76) | 4.5 (36) | 6.0 (14) | 7.1 (15) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 6.5 (176) | 6.7 (98) | 6.4 (51) | 6.4 (15) | 5.7 (12) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 11.5 (311) | 11.8 (171) | 11.3 (90) | 9.9 (23) | 12.8 (27) |

| Number of prior acute prescription medications, % (n) | |||||

| 0 | 17.6 (475) | 20.9 (304) | 13.4 (107) | 15.5 (36) | 13.3 (28) |

| 1 | 37.7 (1,017) | 35.0 (509) | 39.6 (316) | 44.6 (104) | 41.7 (88) |

| 2 | 26.1 (704) | 26.0 (379) | 27.7 (221) | 23.6 (55) | 23.2 (49) |

| 3+ | 18.6 (501) | 18.1 (263) | 19.3 (154) | 16.3 (38) | 21.8 (46) |

| Number of prior preventive prescription medications, % (n) | |||||

| 0 | 16.4 (441) | 16.8 (244) | 17.5 (140) | 14.2 (33) | 11.5 (24) |

| 1 | 24.9 (672) | 22.6 (329) | 25.8 (206) | 30.9 (72) | 30.8 (65) |

| 2 | 25.0 (675) | 24.9 (362) | 24.1 (192) | 24.9 (58) | 29.9 (63) |

| 3+ | 33.7 (909) | 35.7 (520) | 32.6 (260) | 30.0 (70) | 28.0 (59) |

a Baseline comorbidities greater than or equal to 5% are reported.

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

At baseline, the mean migraine-related total ($2,641 vs $2,103: P < 0.01) and pharmacy ($1,395 vs $893: P < 0.0001) costs were significantly higher in the CGRP mAb–treated cohort than in the onabotA-treated cohort (Supplementary Table 4). Mean migraine-related medical costs were comparable between both cohorts for inpatient and ED costs. Mean migraine-related pharmacy costs were significantly higher in the CGRP mAb–treated cohorts than in the onabotA-treated cohort for acute pharmacy ($791 vs $486; P < 0.0001) and preventive pharmacy ($603 vs $408; P < 0.01) costs.

PERSISTENCE

At 12 months, patients treated with onabotA had significantly higher persistence rates compared with the combined CGRP mAb (as a weighted average of the class) group (39.5% vs 26.7%; P = 0.000) (Supplementary Figure 3). Results were similar at 9 (51.0% vs 36.9% for onabotA vs CGRP mAbs; P = 0.000) and 6 (67.4% vs 46.7% for onabotA vs CGRP mAbs; P = 0.000) months. The persistence rates at 12 months were significantly lower for each individual CGRP mAb compared with onabotA (erenumab, 24.4%; fremanezumab, 29.6%; galcanezumab, 32.2%; P = 0.000). The results were similar at 9 (erenumab, 33.4%; fremanezumab, 38.5%; galcanezumab, 43.2%; P = 0.000) and 6 (erenumab, 43.9%; fremanezumab, 47.8%; galcanezumab, 50.4%; P = 0.000) months.

After adjusting for potential confounding variables, the persistence rates at 12 months for onabotA and CGRP mAbs were 40.7% and 27.8%, respectively (OR = 0.683; 95% CI = 0.604-0.768; P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Persistence rates for erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab were 25.5% (OR = 0.627; 95% CI = 0.541-0.722; P < 0.0001), 30.3% (OR = 0.746; 95% CI = 0.598-0.912; P = 0.0033), and 33.7% (OR = 0.828; 95% CI = 0.667-1.006; P = 0.058), respectively. Persistence rates at 6 months and 9 months are presented in Supplementary Table 5.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted 12-Month Persistence Rates for OnabotA vs CGRP mAbs

HEALTH CARE COSTS

During the 12-month follow-up period, the mean total all-cause ($23,204 vs $22,025) and total migraine-related ($9,502 vs $10,446) costs were similar in the onabotA cohort and the CGRP mAb cohort (Supplementary Table 6). Migraine-related total pharmacy costs were significantly lower ($2,066 vs $8,165; P < 0.0001), and migraine-related total medical costs were significantly higher ($7,436 vs $2,281; P < 0.0001) in the onabotA cohort compared with the CGRP mAb cohort. Compared with CGRP mAbs, onabotA was associated with lower 12-month migraine-related inpatient costs ($250 vs $794; P < 0.01) and comparable migraine-related ED costs ($163 vs $140). Compared with CGRP mAbs, onabotA was associated with lower 12-month acute medication ($836 vs $1,360; P < 0.0001) and preventive medication ($752 vs $1,089; P < 0.01) costs.

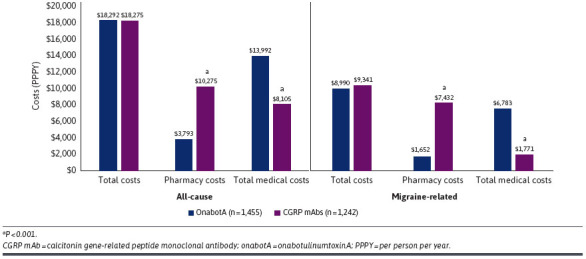

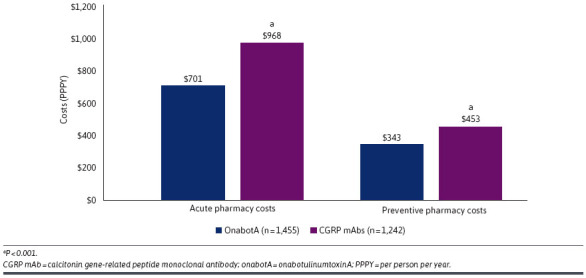

After adjustments were made for confounding covariables, onabotA and CGRP mAbs were associated with comparable 12-month all-cause ($18,292 vs $18,275) and migraine-related ($8,990 vs $9,341) costs (Figure 2). Migraine-related pharmacy costs were significantly lower in the onabotA cohort compared with the CGRP mAb cohort ($1,652 vs $7,432; P < 0.0001). Compared with CGRP mAbs, onabotA was associated with significantly lower migraine-related inpatient costs ($123 vs $370; P < 0.01) and comparable ED costs ($119 vs $93) (Table 2). OnabotA was also associated with significantly lower annual migraine-related acute medication ($701 vs $968; P < 0.0001) and preventive medication ($343 vs $453; P < 0.0001) costs compared with CGRP mAbs (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted All-Cause and Migraine-Related Total, Pharmacy, and Medical Costs Over the 12-Month Follow-Up Period

TABLE 2.

Adjusted Migraine-Related Inpatient and Emergency Department Costs Over the 12-Month Follow-Up Period

| OnabotA (n = 1,455) | CGRP mAbs (n = 1,242) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted migraine-related inpatient and emergency department costs, PPPY | ||

| Inpatient costs | $123 | $370a |

| Emergency department costs | $119 | $93 |

a P ≤ 0.01.

CGRP mAb = calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody; onabotA = onabotulinumtoxinA; PPPY = per person per year.

FIGURE 3.

Adjusted Migraine-Related Acute and Preventive Pharmacy Costs Excluding Cost of OnabotA and CGRP mAbs Over the 12-Month Follow-Up Period

TREATMENT PATTERNS

Among individuals within the CGRP mAb cohort who did not have continuous index treatment (n = 872), 39.2% discontinued treatment without switching to another treatment, 29.0% reinitiated the index treatment, 25.1% switched to another CGRP mAb, 3.9% switched to onabotA, and 2.8% added onabotA (Supplementary Table 7). Among individuals within the onabotA cohort who were considered nonpersistent (n = 896), 50.1% discontinued treatment without switching, 21.9% reinitiated onabotA, 15.5% switched to a CGRP mAb, and 12.5% added a CGRP mAb.

Discussion

In this retrospective observational cohort study, we analyzed persistence rates and health care costs among adults with CM. The results from this study demonstrated significantly higher persistence at 12 months among individuals treated with onabotA compared with those treated with CGRP mAbs. Despite the difference in persistence, total costs were similar between onabotA and CGRP mAbs. These results suggest that treatment with onabotA may offer improved persistence without increasing overall costs for individuals with CM.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess persistence and costs in a cohort of adults with CM receiving branded preventive medications. Previous studies have individually evaluated persistence, costs, and health care resource utilization among patients with CM.8,22-25 However, those studies did not include recently available medications approved for the preventive treatment of CM. Additionally, data evaluating the persistence of branded migraine preventive medications are limited. One study that evaluated persistence to migraine preventive treatment found poor adherence to OMPMs, including any preventive medication, β-blockers, antihypertensives, antiepileptics, antidepressants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers.8 Almost three-quarters of patients initiating OMPMs discontinued treatment at 6 months.8 Of patients cycling through OMPMs, almost 90% discontinued their first, second, or third migraine preventive treatment at 12 months.8 The most common reasons for nonpersistence with OMPMs are lack of adequate effectiveness and intolerable side effects.26

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to this study that are worth noting. First, given that the sample is largely composed of patients with commercial insurance in the United States, these results may not be generalizable to patients with other types of insurance or those without health insurance. Second, as with all retrospective claims analyses, administrative claims data are subject to coding errors, which may result in a potential misclassification of migraine/CM/EM status, covariates, study outcomes, or a combination of these factors. Third, costs were assessed based on index treatment and patients may have switched from a different treatment or added a treatment during the follow-up period, potentially impacting these results. Patients may have switched between CGRP mAbs following a short treatment cycle to seek a more rapid treatment response. In contrast, onabotA has a well-established compulsory 3-month treatment cycle. Fourth, the measure of persistence used assumes that a claim represents administration of the medication; however, this cannot be confirmed using only claims data. Persistence may be overestimated if individuals filled CGRP mAb prescriptions without using all the days supply dispensed. Fifth, onabotA is typically administered every 12 weeks, whereas CGRP mAbs are commonly administered every month (although fremanezumab can be administered every 12 weeks). The impact of these different treatment intervals on persistence rates cannot be directly assessed in this analysis, although there is a suggestion that administration every 12 weeks might be associated with higher persistence compared with monthly administrations.27 These differences in treatment intervals contributed, in part, to the decision to focus on 12-month persistence rates in this analysis, an amount of time that is well beyond the typical trial period for determining the effectiveness of treatment (eg, a 6- to 9-month period for onabotA, a 3-month period for CGRP mAbs administered monthly, or a 6-month period for CGRP mAb administered quarterly). Moreover, a consistent less than 30-day gap between treatments was used to confirm continuous treatment across both cohorts. This approach may have resulted in a further underestimation of persistence within the onabotA cohort. Sixth, this study does not account for recently approved treatment options (ie, oral gepants and eptinezumab) that were not available at the time of this analysis. Future studies should evaluate the impact of these new treatment options on persistence to preventive treatment options. Finally, although this analysis can determine discontinuation of treatment, the reasons for discontinuation cannot be determined based on the claims data. Therefore, treatment discontinuation in this analysis reflects nonpersistence, which may be due to both medical and nonmedical reasons (eg, insurance coverage changes requiring that a patient discontinue their medication or switch from one CGRP mAb to another).

Conclusions

Among individuals with CM undergoing treatment with onabotA or CGRP mAbs, individuals initiating onabotA treatment had significantly higher persistence rates and comparable total all-cause and migraine-related costs over 12 months compared with those initiating CGRP mAbs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF; AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343-9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(5):599-609. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, Smitherman TA. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: Updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55(1):21-34. doi:10.1111/head.12482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goadsby PJ, Evers S. International Classification of Headache Disorders - ICHD-4 alpha. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(9):887-8. doi:10.1177/0333102420919098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Headache Society. IHS classification ICHD-3: Migraine. 2019. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazard E, Munakata J, Bigal ME, Rupnow MF, Lipton RB. The burden of migraine in the United States: Current and emerging perspectives on disease management and economic analysis. Value Health. 2009;12(1):55-64. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD. Migraine prevention. Pract Neurol. 2007;7(6):383-93. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.134023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: A retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470-85. doi:10.1177/0333102416678382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1-18. doi:10.1111/head.13456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botox. Package insert. Allergan USA, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emgality. Package insert. Eli Lilly and Co.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajovy. Package insert. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aimovig. Package insert. Amgen Inc. and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: Evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(3):445-58. doi:10.1177/0333102418821662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: A Phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(6):1026-37. doi:10.1177/0333102418759786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2113-22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):425-34. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30083-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, Friedman DI, Selzler KJ, Aurora SK. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2211-21. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel-Nitz NM, Sander SD, Harley C, Rey GG, Shah H. Costs and outcomes of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke in a managed care population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:905-13. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S10851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griswold M, Parmigiani G, Potosky A, Lipscomb J. Analyzing health care costs: A comparison of statistical methods motivated by Medicare colorectal cancer charges. Biostatistics. 2004;1(1):1-23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurz CF. Tweedie distributions for fitting semicontinuous health care utilization cost data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):171. doi:10.1186/s12874-017-0445-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messali A, Sanderson JC, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Direct and indirect costs of chronic and episodic migraine in the United States: A web-based survey. Headache. 2016;56(2):306-22. doi:10.1111/head.12755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stokes M, Becker WJ, Lipton RB, et al. Cost of health care among patients with chronic and episodic migraine in Canada and the USA: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Headache. 2011;51(7):1058-77. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloudek LM, Stokes M, Buse DC, et al. Cost of healthcare for patients with migraine in five European countries: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). J Headache Pain. 2012;13(5):361-78. doi:10.1007/s10194-012-0460-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonafede M, Sapra S, Shah N, Tepper S, Cappell K, Desai P. Direct and indirect healthcare resource utilization and costs among migraine patients in the United States. Headache. 2018;58(5):700-14. doi:10.1111/head.13275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delussi M, Vecchio E, Libro G, Quitadamo S, de Tommaso M. Failure of preventive treatments in migraine: An observational retrospective study in a tertiary headache center. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):256. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01839-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krasenbaum LJ, Pedarla VL, Thompson SF, Tangirala K, Cohen JM, Driessen MT.. A real-world study of acute and preventive medication use, adherence, and persistence in patients prescribed fremanezumab in the United States. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):54. doi:10.1186/s10194-022-01413-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]