Abstract

Key Clinical Message

Understanding the circumstances, leading to unmasking of hidden Brugada syndrome is essential for the practicing clinician and the patients so that they are informed adequately to seek prompt medical attention.

Abstract

Brugada syndrome is a genetic arrhythmia syndrome characterized by a coved type of ST‐segment elevation in the ECG. The patients are usually asymptomatic, with unmasking of the disease under certain conditions. We are reporting the case of a patient diagnosed with Brugada syndrome, which was unmasked during an attack of dengue fever.

Keywords: Brugada ECG pattern, Brugada syndrome, dengue fever, febrile illness, India

1. INTRODUCTION

Brugada syndrome, described in 1992 by brothers Josep and Pedro Brugada, is a genetic arrhythmia syndrome caused due to gene defects involving the cardiac musculature's sodium, calcium, and potassium channels, among others. Around 18%–30% of defects are attributed to SCN5A gene mutation affecting the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel. 1 This syndrome is characterized by a typical ECG pattern of >0.2 mV of ST‐segment elevation with a coved ST segment and negative T‐wave in more than one anterior precordial leads (V1–V3) along with Right bundle branch block (RBB) in a structurally normal heart. 2 This is accompanied by a risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to ventricular fibrillation or syncope resulting from polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (pVT).

Most patients with this syndrome are asymptomatic. Nevertheless, diagnosing the syndrome by its specific ECG pattern is essential, as the first manifestation of the disease may even be SCD. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is indicated for patients who have had unexplained syncope or have been resuscitated from cardiac arrest. 3 Antiarrhythmic drugs like quinidine and catheter ablation of abnormal regions have been beneficial in suppressing VT. This help to reduce the incidence of SCD to an extent.

The characteristic ST‐elevation crucial for diagnosis may not always be present. It fluctuates with time and is precipitated by various factors. 3 Most important among them are acute illnesses and fever. The syndrome can unmask itself in the event of a febrile illness, and as a result, the disease may present itself for the first time during such an episode.

2. CASE REPORT

A 56‐year‐old male presented with a 3 days history of intermittent fever associated with non‐productive cough. The fever was initially controlled with anti‐pyretic medications. The patient also had headache which was generalized and continuous in nature. He had no history of syncope, palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, or any other cardio‐pulmonary symptoms. The patient is a known case of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and systemic hypertension (SHTN), and was non‐compliant with medications. There is no family history of SCD or any other cardiac diseases. This case has been reported according to the SCARE criteria. 4

The patient was febrile (102.7 F) and tachycardia on examination. A tourniquet test was done on the first day of admission, and approximately 15 petechial spots were noted on the left forearm (The rash was not clearly visible due to skin color). Otherwise, the findings were unremarkable. The laboratory findings showed positive Dengue NS1 antigen and IgM tests, with a platelet count of 187 × 103/μL. Blood investigations done on various days are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Blood investigations performed on various days following admission.

| On the day of admission | Day 2 | On discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 103 F | 102 F | 100 F |

| Platelets | 29 × 103/μL | 26 × 103/μL | 56 × 103/μL |

| Trop T | 0.01 ng/mL (normal) | ||

| CK‐MB | Normal |

The patient was admitted and managed with intravenous fluids, broad‐spectrum antibiotics (IV ceftriaxone 1 g BD for the first 3 days), and acetaminophen. Subsequently, the complete blood count was repeated, showing a platelet count of 29 × 103/μL, hematocrit 45.4%, hemoglobin 15.8 g/dL, WBC 8.24 × 103/μL, and lymphocytes 60.2% with suspected thrombocytopenia, large immature cells, and atypical cells. On Day 2 of admission, complete blood count showed a platelet count of 26 × 103/μL, hematocrit 42.6%, hemoglobin 14.8 g/dL, WBC 8.56 × 103/μL, and lymphocytes 65.2% with suspected thrombocytopenia, lymphocytosis, and large immature cells. Serum electrolytes, urea, and creatinine were all within the normal range.

The patient had relapsing fever during his hospital stay, which was managed with IV and oral acetaminophen. The sequence of ECG findings was documented, showing RBBB with ST‐segment elevation. The patient was stable at discharge and remained asymptomatic at 3 months of follow‐up. ECG findings were suggestive of Brugada syndrome type 1, which was unmasked by dengue fever (Figures 1 and 2).

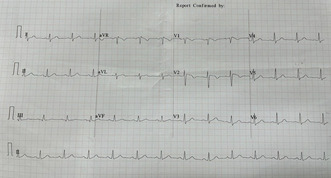

FIGURE 1.

ECG taken at the time of admission (J point elevation of 2 mm from PQ with rectilinear ST depression with T inversion, satisfying the criteria for Type 1 Brugada syndrome, similar pattern seen in aVR, sinus rhythm at 78/min, QRS axis normal, QRS narrow complex, no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy pattern, QTc interval—350 ms).

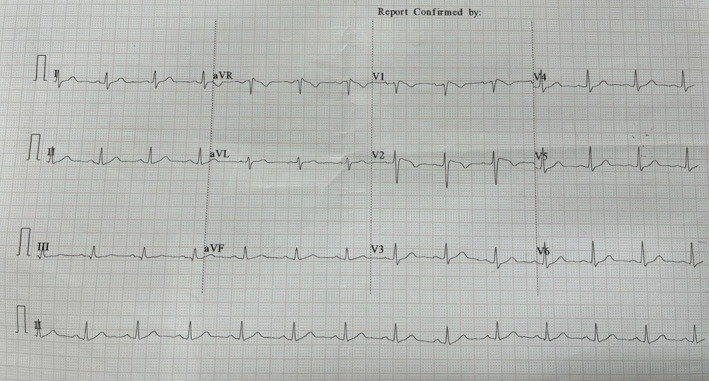

FIGURE 2.

ECG taken at the time of discharge (J point elevation of 2 mm from PQ with rectilinear ST depression with T inversion, satisfying the criteria for Type 1 Brugada syndrome, similar pattern seen in aVR, sinus rhythm at 70/min, QRS axis normal, QRS narrow complex, no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy pattern, QTc interval—350 ms).

3. DISCUSSION

Brugada syndrome is an inherited sodium channel defect that gives rise to fatal ventricular arrhythmia and sudden death. 5 Brugada disease is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that runs in families. However, more than 60% of cases are sporadic. The gene involved is SCN5A which encodes the alpha portion of the sodium channels in cardiac muscles. 6 There's not enough evidence to connect this disease with structural changes in the heart. 5

There are three types of Brugada syndrome, which differ in their ECG presentation. Only Type 1, when present, is considered a diagnostic criterion, whereas the other two suggest the disease rather than diagnostic. 7 Type 1 is characterized by ST‐segment elevation ≥2 mm in more than one lead in the pericardial leads (V1, V2, V3), followed by T inversion. 8 Type 2 is the same ST elevation criteria but followed by biphasic or normal T wave, and Type 3 where ST elevation is ≤1 mm. 9

Brugada syndrome can be considered a differential diagnosis when there is a family history, previous cardiac arrhythmia, previous syncope, previous ventricular tachycardia, or fibrillation. 10 A new scoring system was made to diagnose Brugada syndrome, namely the Shanghai Score System; this score used previous clinical research and data available to make the criteria. 11 This score gives points for each: ECG change, past medical history, genetics, and family history. If the score is 2–3, Brugada is a possible diagnosis. A score of ≥3.5 is a definite diagnosis. 12

The Proposed Shanghai Score System for diagnosis of Brugada syndrome 12 :

| Points | |

|---|---|

| I. ECG (12‐lead/ambulatory) | |

| A. Spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3.5 |

| B. Fever‐induced type 1 Brugada ECG pattern at nominal or high leads | 3 |

| C. Type 2 or 3 Brugada ECG pattern that converts with provocative drug challenge | 2 |

| *Only award points once for the highest score within this category. One item from this category must apply. | |

| II. Clinical history* | |

| A. Unexplained cardiac arrest or documented VF/ polymorphic VT | 3 |

| B. Nocturnal agonal respirations | 2 |

| C. Suspected arrhythmic syncope | 2 |

| D. Syncope of unclear mechanism/unclear etiology | 1 |

| E. Atrial flutter/fibrillation in patients <30 years without alternative etiology | 0.5 |

| *Only award points once for the highest score within this category. | |

| III. Family history | |

| A. First‐ or second‐degree relative with definite BrS | 2 |

| B. Suspicious SCD (fever, nocturnal, Brugada aggravating drugs) in a first‐ or second‐degree relative | 1 |

| C. Unexplained SCD <45 years in first‐ or second‐degree relative with negative autopsy | 0.5 |

| *Only award points once for the highest score within this category. | |

| IV. Genetic test result | |

| A. Probable pathogenic mutation in BrS susceptibility gene | 0.5 |

| Score (requires at least 1 ECG finding) | |

| ≥3.5 points: Probable/definite BrS | |

| 2–3 points: Possible BrS | |

| <2 points: non‐diagnostic | |

Abbreviations: BrS, Brugada syndrome; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Several studies linked the new discovery of Brugada syndrome with fever. 13 , 14 Fever is one of the precipitating factors for developing arrhythmia in Brugada patients. Brugada will be unmasked in different diseases, such as tonsillitis or pneumonia, when accompanied by fever, which may lead to fatal arrhythmias and possible death. 15 18% of Brugada patients who died from cardiac arrest had documented fever. 16 It has been discovered that the gene SCN5A encodes Thr1620Met, which forms the alpha unit of the sodium channel in the heart, is affected by temperature. The higher the temperature, the faster the decay of this protein, and that's what reveals the syndrome. 17 Another study indicates that Brugada ECG changes are 20 times more obvious when associated with high fever. 18

The only definite treatment for Brugada is an ICD, but ICD has limitations and cannot be used in all cases. In such cases where fever unmasked Brugada syndrome, supportive treatment is recommended, using antipyretic and antiarrhythmic quinidine. 19

The list of published case reports (Table 2):

TABLE 2.

Showing the list of published case reports with similar presentation.

| First author | Title of the study | Demographic features | Past history | Duration of illness | Investigation | Treatment given |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kivanç Yalin 20 Istanbul |

Brugada type 1 ECG unmasked by a febrile state following syncope | 24 years, male | None | 1–2 days fever | ECG serum troponin electrocardiography | Antipyretics |

|

Scott P Grogan 21 Germany |

Brugada syndrome unmasked by fever | 20 years, male | None | 5 days | Complete blood count, chemistry, cardiac biomarkers, urinalysis, chest x‐ray, ECG | Broad‐spectrum antibiotics, intravenous fluids, acetaminophen, ICD |

|

Sandhya Manohar 16 USA |

Fever‐induced Brugada syndrome | 74 years, female | Urinary tract infection | 3 days | ECG, echocardiogram, blood work | 48 h of intravenous antibiotic |

|

Hiroki Nakamure 22 Japan |

A successfully treated Brugada syndrome presenting in ventricular fibrillation preceded by fever and concomitant hypercalcemia | 46 years, male | Ulcerative colitis | 3 days | ECG, CT, CBC, provpcalcitonin, electrolyte | Acetaminophen, tazobactam‐piperacillin, vasopressors, meropenem, and vancomycin on Day 5. ICD in 30 days |

|

Carolina Isabel Silva Lemes et al., 23 Brazil |

Brugada pattern unmasked during COVID‐19 infection | 66 years, male | None | 9 days | Complete blood count, electrolyte levels, metabolic panel, troponin, D‐dimer, CT, coronary CT angiography, ECG | Ceftriaxone, antipyretics |

|

Gandhi S et al., 24 Canada |

The management of Brugada syndrome unmasked by fever in a patient with cellulitis | 74 years, male | Hypertension, dyslipidaemia, BPH, cellulitis | 6 days | Complete blood counts, electrolytes, renal function tests, troponins, CXR, blood, and urine culture, ECG | Cefazolin, acetaminophen |

|

Orhay Mirzapolos et al., 25 USA |

Fever unmasked Brugada syndrome in pediatric patient | 5 years, female | None | 2 days | Complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, electrolytes, troponins, CXR, ECG, echocardiogram | Antipyretics |

|

Frenchu K et al., 26 USA |

Brugada syndrome: death reveals its perpetrator | 50 years, female | Essential hypertension, hyperlipidemia | – | Complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, electrolytes, ECG | Hydration, electrolytes, antipyretics, quinidine, isoproterenol, automatic implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (AICD) |

4. CONCLUSION

The characteristic ECG findings of Brugada syndrome are more pronounced in febrile illnesses such as dengue fever. It could be that the inflammatory response and electrolyte imbalances seen in dengue fever potentially triggers or unmasks the Brugada syndrome ECG patterns in susceptible individuals. Increased sympathetic activity and temperature‐dependent ion channel dysfunction could also play a role. Patients presenting with arrhythmias can be managed accordingly to prevent progression and complications. In conclusion, Doctors treating patients with febrile illnesses should have a high index of suspicion and be ready to manage it. Febrile illnesses need to be managed adequately. Further studies should be done to understand more about the degree of association, other precipitating factors, and treatment modalities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lokesh Koumar Sivanandam: Conceptualization; formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; resources; software; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Hima Bindu R. Basani: Investigation; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Vivek Sanker: Investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Shamal Roshan: Methodology; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Marah Hunjul: Project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Umang Gupta: Investigation; methodology; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was not required for the case report as per the country's guidelines.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report.

Sivanandam LK, Basani HBR, Sanker V, Roshan S S, Hunjul M, Gupta U. Brugada syndrome unmasked by dengue fever. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e8005. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8005

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting this article's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659‐670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brugada P, Brugada J. Persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome: a multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391‐1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Vol 2. 12th ed. McGraw‐Hill Professional; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, et al. Guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020;84:226‐230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oliva A, Grassi S, Pinchi V, et al. Structural heart alterations in Brugada syndrome: is it really a channelopathy? A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campuzano O, Brugada R, Iglesias A. Genetics of Brugada syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25(3):210‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Z, Chen PS, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Why is only type 1 electrocardiogram diagnostic of Brugada syndrome? Mechanistic insights from computer modeling. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15(1):e010365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Priori SG, Blomström‐Lundqvist C. 2015 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death summarized by co‐chairs. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(41):2757‐2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilde AAM, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(21):1648‐1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brugada R, Campuzano O, Sarquella‐Brugada G, Brugada J, Brugada P. Brugada syndrome. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014;10(1):25‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kawada S, Morita H, Antzelevitch C, et al. Shanghai score system for diagnosis of Brugada syndrome. JACC: Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4(6):724‐730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Antzelevitch C, Yan G‐X, Ackerman MJ, et al. J‐Wave syndromes expert consensus conference report: emerging concepts and gaps in knowledge. Europace. 2016;19(4):665‐694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ortega‐Carnicer J, Benezet J, Ceres F. Fever‐induced ST‐segment elevation and T‐wave alternans in a patient with Brugada syndrome. Resuscitation. 2003;57(3):315‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Porres JM, Brugada J, Urbistondo V, García F, Reviejo K, Marco P. Fever unmasking the Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(11):1646‐1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Antzelevitch C, Brugada R. Fever and Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(11):1537‐1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manohar S, Dahal BR, Gitler B. Fever‐induced Brugada syndrome. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2015;3(1):2324709615577414. doi: 10.1177/2324709615577414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dumaine R, Towbin JA, Brugada P, et al. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the electrocardiographic phenotype of the Brugada syndrome are temperature dependent. Circ Res. 1999;85(9):803‐809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Postema PG. Fever and the electrocardiogram: what about Brugada syndrome? Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(9):1383‐1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roomi SS, Ullah W, Abbas H, Abdullah H, Talib U, Figueredo V. Brugada syndrome unmasked by fever: a comprehensive review of literature. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020. Jun 14;10(3):224‐228. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2020.1767278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yalin K, Gölcük E, Bilge AK, Adalet K. Brugada type 1 electrocardiogram unmasked by a febrile state following syncope. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2012;40(2):155‐158. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2012.01725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grogan SP, Cube RP, Edwards JA. Brugada syndrome unmasked by fever. Mil Med. 2011;176(8):946‐949. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakamura H, Sato Y, Ishii R, Araki Y. A successfully treated Brugada syndrome presenting in ventricular fibrillation preceded by fever and concomitant hypercalcemia. Turk J Emerg Med. 2022;22(3):163‐165. doi: 10.4103/2452-2473.348439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lemes CIS, Armaganijan LV, Maria AS, et al. Brugada pattern unmasked during COVID‐19 infection‐:a case report. J Cardiol Cases. 2022;25(6):377‐380. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2022.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gandhi S, Kuo A, Smaggus A. The management of Brugada syndrome unmasked by fever in a patient with cellulitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009063. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mirzapolos O, Marshall P, Brill A. Fever unmasked Brugada syndrome in pediatric patient: a case report. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2020;4(2):244‐246. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2020.2.44418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frenchu K, Flood S, Rousseau L, Poppas A, Chu A. Brugada syndrome: death reveals its perpetrator. JACC Case Rep. 2019;1(1):55‐56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.