Abstract

The aim of this observational study was to examine differences in milk fatty acid (FA) concentrations for different metabolic health statuses and for associated factors—specifically to examine with which FA concentrations an increased risk for developing a poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS) was associated. During weekly visits over 51 wk, blood samples were collected from cows between 5 and 50 days in milk. The farmer collected corresponding milk samples from all voluntary milkings. The analysis was performed on n = 2,432 samples from n = 553 Simmental cows. The observations were assigned to five different cow types (healthy, clever, athletic, hyperketonemic, and PMAS, representing five metabolic health statuses), based on the thresholds of 0.7 mmol/L, 1.2 mmol/L, and 1.4 for the concentrations of β-hydroxybutyrate and nonesterified fatty acids and for the milk fat-to-protein ratio, respectively. Linear regression models using the predictor variables cow type, parity, week of lactation, and milk yield as fixed effects were developed using a stepwise forward selection to test for significant associations of predictor variables regarding FA concentrations in milk. There was a significant interaction term found between PMAS cows and parity compared to healthy cows for C18:1 (P < 0.001) and for C18:0 (P < 0.01). It revealed higher concentrations for PMAS in primiparous and multiparous cows compared to healthy cows, the slope being steeper for primiparous cows. Further, an interaction term was found between PMAS cows and milk yield compared to healthy cows and milk yield for C16:0 (P < 0.05), revealing a steeper slope for the decrease of C16:0 concentrations with increasing milk yield for PMAS compared to healthy cows. The significant associations and interaction terms between cow type, parity, week of lactation, and milk yield as predictor variables and C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 concentrations suggest excellent opportunities for cow herd health screening during the early postpartum period.

Keywords: metabolic health status, milk fatty acids, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome

The significant associations and interaction terms between cow type (healthy, clever, athletic, hyperketonemic, and poor metabolic adaptation syndrome, representing five metabolic health statuses), parity, week of lactation, and milk yield as predictor variables and C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 concentration suggest excellent opportunities to improve cow herd health screening during the early postpartum period regarding metabolic health.

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic disorders, especially after calving, are a major factor when considering animal health and the economic aspects of modern dairy farming (Geishauser et al., 2001; Suthar et al., 2013; Gohary et al., 2016). Among other terms, the term “poor metabolic adaptation syndrome” (PMAS) was introduced to describe the complex metabolic status during a metabolic disorder, rather than ketosis, which, per its definition, is limited to an increase in ketone bodies, mostly β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA), in the blood (Tremblay et al., 2018). Differences among high-, moderate-, and low-risk PMAS, mostly characterized by the nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) concentration in blood, as well as different cow types, referring to different metabolic health statuses are described (Tremblay et al., 2018; Mandujano Reyes et al., 2023). The PMAS risk can be predicted using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) data from milk (Tremblay et al., 2018).

Models predicting concentrations of NEFA and BHBA, as well as PMAS from concentrations of milk ingredients, have reached reasonable prediction accuracies (Tremblay et al., 2019); nevertheless, it is important to further understand the metabolic changes in the body after parturition to derive refined management instructions for cows with metabolic disorders and herd health management.

Fatty acids (FA) are promising because they reflect the extent of body fat mobilization (Rukkwamsuk et al., 2000; Oetzel, 2004). Concentrations of FA or FA ratios can be examined in blood and in milk (Mann et al., 2016; Melendez et al., 2016; Dorea et al., 2017; Reus and Mansfeld, 2020). Metabolized adipose tissue, which is present in the blood at higher concentrations and is used for milk production during a state of energy deficiency, consists of long-chain fatty acids, while FA directly synthesized in the mammary gland consist of short-chain fatty acids (Bauman and Griinari, 2003). Additionally, since milk is a substrate that is easy to obtain, it has a possible use in routine diagnoses using high-throughput technologies (Enjalbert et al., 2001; Mann et al., 2016).

The prevalence of metabolic disorders and the severity of the cases are influenced by environmental and management factors, such as feed and herd health monitoring, as well as by cow factors, such as the number of lactations, milk yield, days in milk (DIM), and the ability to tolerate hyperketonemia (Herdt, 2000; Gordon et al., 2013).

The aim of this observational study was to examine differences in the milk FA concentrations for different metabolic health statuses and for associated factors, such as parity, week of lactation, and milk yield in early postpartum cows—specifically to examine with which FA concentrations an increased risk for developing PMAS was associated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The official number of the approved animal experiment proposal for the Government of Bavaria was ROB-55.2Vet-2532.Vet_03-17-84. All used animal procedures apply to § 7-10 Tierschutzgesetz (TierSchG) and § 31-42 Tierschutzversuchstierverordnung (TierSchVersV).

Data Collection

Eight Bavarian dairy farms were selected to participate in the observational study. Selection criteria were location in the region of South Bavaria, use of an automated milking system (AMS) implying a minimum number of 50 lactating cows, herds consisting mainly of Simmental cows and willingness of the farmer to participate.

During weekly visits over 51 wk between January and December 2018 on the farms, blood samples were collected from all cows between 5 and 50 DIM from the coccygeal vein into a blood collection tube (BD-Serum-Gel-Vacutainer, SST 2 advanced, 8.5 mL, BD, Heidelberg, Germany).

Farm and cow identification, date, breed, DIM, and parity were recorded and assigned to the respective blood collection tube identifications.

One farm used DeLaval (De Laval GmbH, Glinde, Germany), two farms used Lely (Lely Industries N.V., Maassluis, The Netherlands), and five farms used Lemmer-Fullwood (Lemmer-Fullwood GmbH, Lohmar, Germany) AMS. The farmer connected a milk sample shuttle ORI-Collector (SAYCA Automatizacion, Alcalá de Henares, Spain) for 12 to 24 h, alternating over the day or the night before the visit, to collect composite milk samples from all voluntary milkings from cows between 5 and 50 DIM.

For the milk sample collection, sampling bottles of type 6845-xx (Bartec Benke GmbH, Gotteszell, Germany) containing 2 mL of preservative gel consisting of <4% sodium azide, <3% bronopol (2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol), and <0.2% chloramphenicol were used. If the sample collection from a cow over one sample period resulted in multiple milk samples, the milk sample with the shortest time distance to the blood sampling was assigned to the blood sample.

Milk yield was measured by the standard equipment of the respective AMS, transmitted to the Dairy Herd Improvement Association of Bavaria (LKB Bayern e.V.) and assigned to the respective milk sample.

Blood samples were analyzed for concentrations of BHBA and NEFA in the laboratory of the Clinic for Ruminants, LMU Munich, using a Cobas c311-Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Milk samples were transported at 4 °C and analyzed in the laboratory of the Bavarian Association for raw milk testing (MPR Bayern e. V., mpr, Wolnzach, Germany) for concentrations of fat, protein, urea, lactose, BHBA, and NEFA using the MilkoScan FT-6000 (FOSS GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). The somatic cell count (SCC) was determined using Fossomatic FC (FOSS GmbH), and the milk fat-to-protein ratio (FPR) was calculated.

The milk FA concentrations were calculated using milk FTIR data (Schwarz et al., 2021) by mpr using the FOSS-AN0064r7 package (FOSS GmbH).

Data Editing and Analysis

From n = 3,552 total observations, observations without standardization, blood BHBA or NEFA information, and FA panels with DIM < 5 or DIM > 50 and from other breeds were removed.

After removing observations without information on FA concentrations in milk, assuming the missing values to be random, n = 2,432 observations from n = 524 cows with a mean value of n = 4 observations (SD = 1.70) per cow were used for linear models for the outcomes of the milk FA concentrations. The analyses were performed using R software, versions 3.6.1 and 3.6.3 (R Development Core Team, 2013).

Cow Type Determination

Every observation was assigned to one of five different cow types (healthy, clever, athletic, hyperketonemic, and PMAS) following the decision tree in Figure 1 based on the description in Mandujano Reyes et al. (2023) (Figure 2). This implies that cows can be assigned to various cow types over time after parturition. Elevated cutoff values were set at 0.7 and 1.2 mmol/L for NEFA and BHBA, respectively, and the cutoff value for a reduced FPR was set at 1.4.

Figure 1.

Decision tree to classify observations into the athletic, hyperketonemic, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS), healthy, or clever cow types. Elevated cutoff values were set at 0.7 and 1.2 mmol/L for nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) and β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA), respectively. The cutoff value for an elevated milk fat-to-protein ratio (FPR) was set at 1.4.

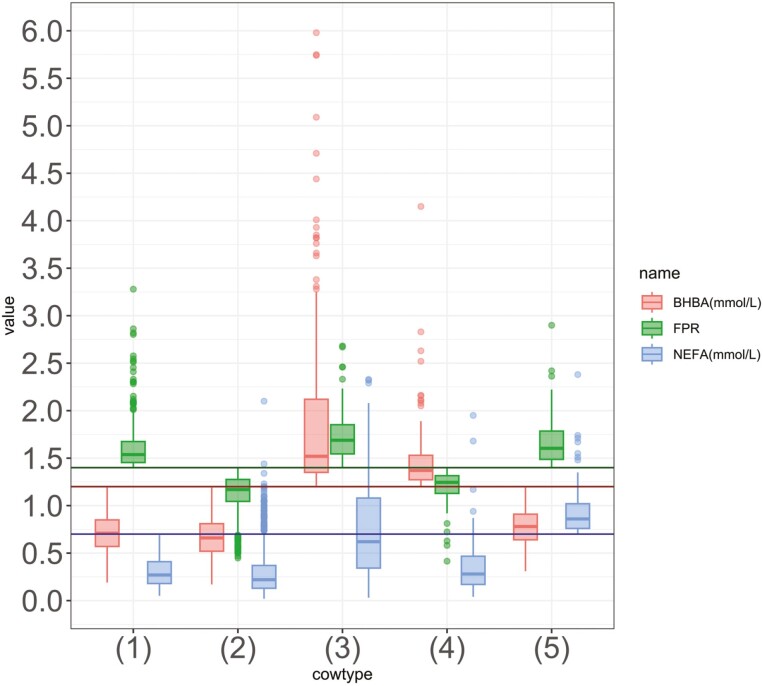

Figure 2.

Boxplot of the nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) and β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) concentrations in mmol/L as well as the fat-to-protein ratio (FPR) of the five cow types in the data set (n = 2,432 observations from 521 Simmental cows from eight Bavarian herds sampled at 5 to 50 days in milk). Cow types of observations are classified following the decision tree shown in Figure 1 resulting in the following group sizes: healthy: n = 539, clever: n = 1,584, athletic: n = 146, hyperketonemic: n = 82, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS): n = 81. Cowtypes: (1): healthy, (2): clever, (3): athletic, (4): hyperketonemic, and (5): poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS).

The healthy cow type was defined by normal BHBA and NEFA concentrations as well as a normal FPR. The clever cow type was defined by a normal BHBA concentration and a reduced FPR. Athletic cows were defined by an elevated BHBA concentration and a normal FPR, while hyperketonemic cows were defined by an elevated BHBA concentration and a reduced FPR. The PMAS cow type was defined by a normal BHBA concentration and a normal FPR and, in contrast to the healthy cow type, by an elevated NEFA concentration.

Linear Models

Days in milk were transformed into a categorial variable: week of lactation. Weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 of lactation were defined as DIM ≤ 7, 8–14, 15–21, 22–28, 29–35, 36–42, 43–49, and 50, respectively.

Four predictor variables were defined: cow type (healthy, clever, athletic, hyperketonemic, and PMAS), parity (primiparous or multiparous cow), and week of lactation (week 1 to 8) as categorial, as well as milk yield in kg (milk yield) as a continuous variable. Milk yield was log transformed and milk yield and FA concentrations were scaled. Collinearity was checked between the predictor variables cow type, parity, DIM, and milk yield using an identity matrix created using the ggpairs function.

Three milk FA concentrations (palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and oleic acid (C18:1)) were defined as outcome variables. Histograms were used to assess whether FA concentrations were normally distributed within the cow types. The one-way Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test for differences in concentrations of FA in milk between cow types, and pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test with a Bonferroni correction were conducted to test for differences between each cow type (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of cow production variables from the data set of eight dairy herds in Bavaria sampled between 5 and 50 days in milk. Data set (n = 2,432 observations)

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Lactation number | 3.2 | (1.9) |

| Days in milk |

28.3 | (12.8) |

| Milk yield per day, kg | 33.2 | (8.0) |

| Fat, % | 4.2 | (0.9) |

| Protein, % | 3.3 | (0.4) |

| Lactose, % | 4.9 | (0.2) |

| Urea, mg/100 mL | 24.4 | (7.3) |

| SCC, 1,000 cells/mL | 187.2 | (618.4) |

| BHBA, mmol/L | 0.80 | (0.48) |

| NEFA, mmol/L | 0.34 | (0.29) |

| FPR | 1.30 | (0.30) |

SCC, somatic cell count in milk; BHBA, β-hydroxybutyrate in blood; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids in blood; FPR, fat-to-protein ratio in milk.

The models were built using the package lme4. Linear regression models using the four predictor variables and interaction terms between cow type and the other predictor variables as fixed effects, farm identification (ID) and cow ID as random effects and the FA concentrations as outcome variable were developed with the data set using forward stepwise selection. This resulted in three models for C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 in milk, respectively.

A goodness-of-fit evaluation was performed by plotting residual over fitted values for each model. The resulting graph showed that the residual values were distributed symmetrically over the horizontal line at 0. The distribution of the residuals was normal.

Visualization

Effect plots were created using the allEffects function of the effects package to visualize the association of the predictor variables with the cow types regarding FA concentrations.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics have been summarized in Table 1. Of n = 2,432 total observations, n = 539, n = 1,584, n = 146, n = 83, and n = 81 were assigned to the healthy, clever, athletic, hyperketonemic, and PMAS cow types, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean milk fatty acid concentrations and standard deviation per cow type (n = 2,432 observations) in g/100 g milk for palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and oleic acid (C18:1) as calculated using milk FTIR and the standard error (SE) of the prediction

| Healthy (n = 539) |

Clever (n = 1,584) |

Athletic (n = 146) |

Hyperketonemic (n = 82) |

PMAS (n = 81) |

Total (n = 2,432) |

SE (prediction) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C16:0 | 1.30a (0.22) |

1.07b (0.19) |

1.22c (0.20) |

1.01b (0.20) |

1.23c (0.22) |

1.13 (0.22) |

0.11 |

| C18:0 | 0.59a (0.11) |

0.41b (0.10) |

0.70c (0.15) |

0.45d (0.11) |

0.68c (0.14) |

0.48 (0.15) |

0.05 |

| C18:1 | 1.40a (0.33) |

0.90b (0.25) |

1.73c (0.44) |

0.98b (0.31) |

1.74c (0.42) |

1.09 (0.41) |

0.07 |

PMAS, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome;16:0, palmitic acid; C18:0, stearic acid; C18:1, oleic acid.

a–d Letters indicate mean fatty acid concentrations differ as determined by pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test with a Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05).

The C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 concentrations varied significantly (P < 0.05) between cow types as determined by Kruskal–Wallis test. Significant differences in concentrations between each cow type determined by pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon rank sum test with a Bonferroni correction are indicated in Table 2. The standard error (SE) for each parameter prediction is also indicated.

Linear Models

The final models varied in characteristics (Tables 3–5). All three final models used parity as a fixed effect and interaction terms between cow type on the one hand, and parity and log(milk yield) on the other hand. Models for C18:0 and C18:1 also used week as fixed effect and the model for C18:0 additionally used the interaction term between parity and log(milk yield). The results for the respective effects are described below.

Table 3.

Summary of the linear regression for palmitic acid (C16:0) in milk in g/100 g fat without random effects, observations: n = 2,432

| C16:0 | Mean (SD) | Coefficient (95% CI, P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Cowtype | ||

| Healthy (= ref) | 0.8 (1.0) | — |

| Clever | −0.3 (0.8) | −1.04 (−1.13 to −0.95, P < 0.001) |

| Athletic | 0.4 (0.9) | −0.36 (−0.53 to −0.20, P < 0.001) |

| Hypket. | −0.6 (0.9) | −1.31 (−1.52 to −1.11, P < 0.001) |

| PMAS | 0.5 (1.0) | −0.30 (−0.51 to −0.09, P < 0.005) |

| Parity | ||

| Multip. (= ref) | −0.0 (1.0) | — |

| Healthy × Multip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Multip. | −1.06 (−1.14 to −0.97, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Multip. | −0.34 (−0.51 to −0.17, P < 0.001) | |

| Hypket. × Multip. | −1.32 (−1.51 to −1.13, P < 0.001) | |

| PMAS × Multip. | −0.19 (−0.39 to 0.01, P < 0.057) | |

| Primip. | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.11, P < 0.722) |

| Healthy × Primip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Primip. | −1.03 (−1.18 to −0.87, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Primip. | 0.05 (−0.27 to 0.37, P < 0.740) | |

| Hypket. × Primip. | −0.98 (−1.67 to −0.30, P < 0.005) | |

| PMAS × Primip. | 0.15 (−0.52 to 0.22, P < 0.433) | |

| log(milk yield) [−11.3, 3.0] | 0.0 (1.0) | −0.21 (−0.25 to −0.18, P < 0.001) |

| Healthy × log(milk yield) (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × log(milk yield) | −0.22 (−0.27 to −0.17, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × log(milk yield) | −0.12 (−0.26 to 0.01, P < 0.065) | |

| Hypket. × log(milk yield) | −0.11 (−0.35 to 0.12, P < 0.346) | |

| PMAS × log(milk yield) | −0.21 (−0.40 to −0.03, P < 0.026) |

ref, reference; hypket., hyperketonemic; PMAS, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome; primip., primiparous; multip., multiparous.

Table 5.

Summary of the linear regression for oleic acid (C18:1) in milk in g/100 g fat with random effects (cow ID, farm ID), observations: n = 2,432

| C18:1 | Mean (SD) | Coefficient (95% CI, P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Cowtype | ||

| Healthy (= ref) | 0.8 (0.8) | — |

| Clever | −0.5 (0.6) | −1.23 (−1.30 to −1.16, P < 0.001) |

| Athletic | 1.5 (1.1) | 0.78 (0.65 to 0.91, P < 0.001) |

| Hypket. | −0.3 (0.7) | −1.03 (−1.20 to −0.87, P < 0.001) |

| PMAS | 1.6 (1.0) | 0.80 (0.64 to 0.97, P < 0.001) |

| Parity | ||

| Multip. (= ref) | −0.1 (1.0) | — |

| Healthy × Multip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Multip. | −1.13 (−1.19 to −1.07, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Multip. | 0.71 (0.59 to 0.83, P < 0.001) | |

| hypket. × Multip. | −0.92 (−1.06 to −0.78, P < 0.001) | |

| PMAS × Multip. | 0.37 (0.23 to 0.51, P < 0.001) | |

| Primip. | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.44 (0.35 to 0.54, P < 0.001) |

| Healthy × Primip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Primip. | −1.19 (−1.30 to −1.08, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Primip. | 0.16 (−0.07 to 0.38, P < 0.248) | |

| Hypket. × Primip. | −0.72 (−1.21 to −0.24, P < 0.014) | |

| PMAS × Primip. | 0.69 (0.43 to 0.95, P < 0.001) | |

| Week | ||

| 1 (= ref) | 0.3 (1.2) | — |

| 2 | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.20 (0.00 to 0.40, P < 0.047) |

| 3 | 0.2 (1.0) | −0.08 (−0.27 to 0.12, P < 0.441) |

| 4 | −0.0 (0.9) | −0.33 (−0.52 to −0.13, P < 0.001) |

| 5 | −0.1 (1.0) | −0.40 (−0.59 to −0.21, P < 0.001) |

| 6 | −0.3 (0.9) | −0.58 (−0.77 to −0.39, P < 0.001) |

| 7 | −0.3 (0.8) | −0.61 (−0.81 to −0.42, P < 0.001) |

| 8 | −0.4 (0.8) | −0.76 (−1.09 to −0.42, P < 0.001) |

| log(milk yield) [−11.3,3.0] | 0.0 (1.0) | −0.17 (−0.21 to −0.13, P < 0.001) |

| Healthy × log(milk yield) (= ref) | ||

| Clever × log(milk yield) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02, P < 0.684) | |

| Athletic × log(milk yield) | −0.29 (−0.38 to −0.20, P < 0.001) | |

| Hypket. × log(milk yield) | −0.04 (−0.21 to 0.13, P < 0.707) | |

| PMAS × log(milk yield) | −0.13 (−0.26 to 0.01, P < 0.120) |

Ref, reference; hypket., hyperketonemic; PMAS, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome; primip., primiparous; multip., multiparous.

Associations for Cow Type

All associations for cow type were significant (P < 0.01). Associations for C16:0 revealed lower concentrations for PMAS cows compared to healthy cows (P < 0.01) and descending in the following order: athletic, clever, and hyperketonemic compared to healthy cows (P < 0.001, Table 3, Figure 3). For C18:0, associations revealed lower concentrations for hyperketonemic and even lower for clever compared to healthy cows (P < 0.001) and higher for PMAS and even higher for athletic compared to healthy cows (P < 0.001, Table 4, Figure 4). Finally, associations for C18:1 revealed similar association to C18:0, only PMAS cow type concentrations were higher than athletic cow type concentrations and all associations were significant (P < 0.001, Table 5, Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Effect plots of the linear model for scaled palmitic acid (C16:0) concentration in milk (n = 2,432 observations, originally in g/100 g fat) with 95% confidence intervals. Effects: (a) parity and (b) log(milk yield), originally in L/d. The cow types are as following: (1): healthy, (2): clever, (3): athletic, (4): hyperketonemic, and (5): poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS).

Table 4.

Summary of the linear regression for stearic acid (C18:0) in milk in g/100 g fat without random effects, observations: n = 2,432

| C18:0 | Mean (SD) | Coefficient (95% CI, P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Cowtype | ||

| Healthy (= ref) | 0.8 (0.8) | — |

| Clever | −0.5 (0.7) | −1.25 (−1.32 to −1.17, P < 0.001) |

| Athletic | 1.5 (1.0) | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.83, P < 0.001) |

| Hypket. | −0.2 (0.7) | −0.94 (−1.11 to −0.77, P < 0.001) |

| PMAS | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.58 (0.41 to 0.76, P < 0.001) |

| Parity | ||

| Multip. (= ref) | −0.1 (1.0) | — |

| Healthy × Multip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Multip. | −1.01 (−1.17 to −1.03, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Multip. | 0.61 (0.47 to.75, P < 0.001) | |

| Hypket. × Multip. | −0.86 (−1.02 to −0.70, P < 0.001) | |

| PMAS × Multip. | 0.23 (0.06 to 0.39, P < 0.007) | |

| Primip. | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.53, P < 0.001) |

| Healthy × Primip. (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × Primip. | −1.14 (−1.27 to −1.02, P < 0.001) | |

| Athletic × Primip. | 0.13 (−0.13 to 0.38, P < 0.341) | |

| hypket. × Primip. | −0.74 (−1.30 to −0.19, P < 0.009) | |

| PMAS × Primip. | 0.40 (0.10 to 0.70, P < 0.009) | |

| Week | ||

| 1 (= ref) | 0.4 (1.1) | — |

| 2 | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.18 (−0.01 to 0.38, P < 0.068) |

| 3 | 0.3 (1.0) | −0.15 (−0.34 to 0.04, P < 0.120) |

| 4 | 0.0 (0.9) | −0.41 (−0.60 to −0.22, P < 0.001) |

| 5 | −0.1 (1.0) | −0.53 (−0.72 to −0.34, P < 0.001) |

| 6 | −0.3 (0.9) | −0.74 (−0.93 to −0.55, P < 0.001) |

| 7 | −0.4 (0.8) | −0.80 (−0.99 to −0.61, P < 0.001) |

| 8 | −0.5 (0.8) | −0.92 (−1.25 to −0.59, P < 0.001) |

| log(milk yield) [−11.3,3.0] | −0.0 (1.0) | −0.17 (−0.21 to −0.13, P < 0.001) |

| Healthy × log(milk yield) (= ref) | — | |

| Clever × log(milk yield) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05, P < 0.590) | |

| Athletic × log(milk yield) | −0.19 (−0.29 to −0.08, P < 0.001) | |

| Hypket. × log(milk yield) | −0.04 (−0.23 to 0.15, P < 0.678) | |

| PMAS × log(milk yield) | −0.07 (−0.22 to 0.08, P < 0.363) | |

| Multip. × log(milk yield) (= ref) | — | |

| Primip. × log(milk yield) | −0.07 (−0.16 to 0.02, P < 0.151) |

ref, reference; hypket., hyperketonemic; PMAS, poor metabolic adaptation syndrome; primip., primiparous; multip., multiparous.

Figure 4.

Effect plots of the linear model for scaled stearic acid (C18:0) concentration in milk (n = 2,432 observations, originally in g/100 g fat) with 95% confidence intervals. Effects: (a) week after parturition, (b) parity, (c) log(milk yield), originally in L/d, and (d) parity × log(milk yield), originally in L/d. The cow types are as following: (1): healthy, (2): clever, (3): athletic, (4): hyperketonemic, and (5): poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS).

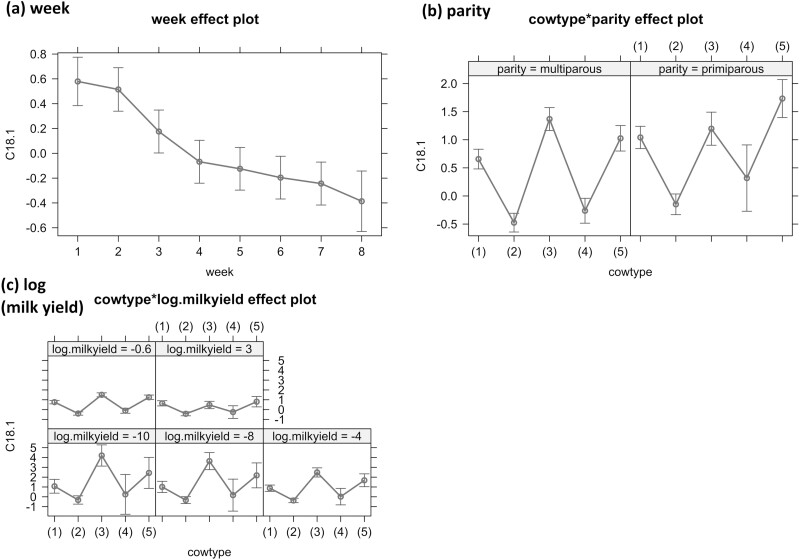

Figure 5.

Effect plots of the linear model for scaled oleic acid (C18:1) concentration in milk (n = 2,432 observations, originally in g/100 g fat) with 95% confidence intervals. Effects: (a) week of lactation (week), (b) parity, and (c) log(milk yield), originally in L/d. The cow types are as following: (1): healthy, (2): clever, (3): athletic, (4): hyperketonemic, and (5): poor metabolic adaptation syndrome (PMAS).

Associations for Parity

All FA showed associations for parity revealing higher concentrations in primiparous compared to multiparous cows. These associations were significant only for C18:0 and C18:1 (P < 0.001, Tables 3–5, Figures 3–5).

Significant interaction terms between parity and cow types were found for all FA. The slopes between cow types were similar between the associations for cow type only and the interaction term between parity and cow type for multiparous cows for C16:0 and C18:0 and for primiparous cows for C18:1. Apart from PMAS cows within C16:0 and athletic cows within C18:1, this was statistically significant for all mentioned slopes (P < 0.01). For C16:0, the slopes for primiparous cows were different for athletic cows revealing higher concentrations in athletic compared to healthy cows and a less steep slope for hyperketonemic than for clever cows, both showing lower concentrations, compared to healthy cows. In primiparous cows, only the associations between clever and hyperketonemic on the one hand compared to healthy on the other hand are statistically significant (P < 0.01). For C18:0, the slopes for primiparous compared to multiparous cows were different for the interaction term with athletic and PMAS cows, PMAS cows revealing a steeper slope and athletic cows revealing a less steep slope, both showing higher concentrations than healthy cows. The association between parity and cow type was statistically significant for clever (P < 0.001) and hyperketonemic cows and PMAS cows (P < 0.01). The slopes within C18:1 in multiparous compared to primiparous cows were different for athletic and PMAS cows, revealing a less steep slope for PMAS than for athletic cows, both still showing higher concentrations compared to healthy cows. All interaction terms between multiparous cows and cow type were statistically significant for C18:1 (P < 0.001).

Associations for Week of Lactation

There were significant associations between week of lactation and C18:0 and C18:1 concentrations (P < 0.05, Tables 4 and 5, Figures 4 and 5), revealing a peak during week 2, that was only significant for C18:1 (P < 0.05) and a following decrease over increasing weeks of lactation that was significant for C18:0 beginning in week 3 (P < 0.001) and for C18:1 beginning in week 4 (P < 0.001).

Associations for Milk Yield

All FA concentrations decreased with increasing milk yield (P < 0.001, Tables 3–5, Figures 3–5).

An interaction term between milk yield and cow type was used for all FA and revealed increasingly steep slopes in the following order for C16:0: hyperketonemic, athletic, PMAS, and clever compared to healthy cows. These findings were significant for PMAS (P < 0.05) and clever cows (P < 0.01). For C18:0 and C18:1, the order was as following: clever, hyperketonemic, PMAS, and athletic compared to healthy cows and statistically significant only for athletic cows (P < 0.005).

There were no significant findings for the interaction term between parity and milk yield within C18:0.

DISCUSSION

Examined Fatty Acids and Effects

Milk short-chained fatty acids (C5–C15) decrease with increasing blood NEFA or ketone bodies as a biomarker for metabolic disorders, while long-chained fatty acids, for example, oleic acid (C18:1), increase during metabolic disorders in blood (Bauman and Griinari, 2003; Van Haelst et al., 2008; Mann et al., 2016). The present results, for example, higher concentrations of C18:0 and C18:1 in the milk of PMAS cows, are in accordance with the finding that long chained fatty acids increase with an increased risk of a metabolic imbalance. It was found that stearic acid (C18:0) is the predominant fatty acid in the uptake through feed (Glasser et al., 2008; Loften et al., 2014), while oleic acid is the main fatty acid in adipose tissue and the first FA released during NEB (Rukkwamsuk et al., 2000; Loften et al., 2014). Palmitic acid (C16:0) was shown to be the predominant fatty acid in milk fat, with C18:1 representing the second highest concentration (Loften et al., 2014). This is in accordance with the results of this study for the total set of data and for the clever and hyperketonemic cow group. For healthy, athletic, and PMAS cows, the concentration of oleic acid was higher than the concentration of palmitic acid.

When comparing blood and especially milk FA concentrations of primiparous to multiparous cows during early lactation, several reports can be found in the respective literature. It has been reported that C18:0 and C18:1 would be higher in primiparous than in multiparous cows (Van et al., 2020). In accordance with these findings, our results indicate that C18:0 and C18:1 milk fat concentration were significantly (P < 0.001) higher in primiparous than in multiparous cows. Multiparous cows suffer more often from metabolic diseases than primiparous cows (Gordon et al., 2013).

The associations for C16:0 concentrations (P < 0.001) revealed very similar concentrations for multiparous compared to primiparous cows when not considering different cow types. The findings for C16:0 and C18:0 are in accordance with Van et al. (2020).

It is well known that cows suffer from NEB after parturition (Bell, 1995). Furthermore, milk FA and FA group concentrations physiologically decrease over increasing weeks of lactation (Gross et al., 2011). These facts agree with our results, as C18:0 and C18:1 concentration decreased over time after parturition.

Interaction terms between cow type and milk yield revealed decreased concentrations of milk FA in association with increased milk yield for every cow type. This contradicts previous findings, showing that high-yielding cows were exposed to higher metabolic stress (Nogalski et al., 2015). The interaction terms revealed significantly steeper slopes of decrease for PMAS compared to healthy cows for C16:0 (P < 0.05) and steeper slopes of decrease for PMAS compared to healthy cows for C18:0 and C18:1, although these findings were not statistically significant, leading to a greater difference between PMAS compared to healthy cows associated with lower milk yield and more similar concentrations associated with higher milk yield. The findings support the reports in the literature that, during a high milk yield, all cow types are exposed to metabolic imbalances (Nogalski et al., 2015), and show that PMAS cows are more severely affected than healthy cows when associated with lower milk yield compared to higher milk yield. Consequently, these findings support the idea of analyzing the response patterns to NEB by cow type, or these different patterns could go unnoticed and improve the differentiation between PMAS and non-PMAS cows when associated with lower milk yield.

Application

There were significant associations and interaction terms between the predictor variables cow type, parity, week of lactation and milk yield and the outcome variables C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 concentration.

These findings represent excellent opportunities for cow herd health screening during the early postpartum period. Transition cow management aims to prevent the consequences of NEB to improve productivity, cow health, and longevity. Preventing the consequences of NEB in PMAS cows by applying early detection followed by intervention could prevent animal suffering. Therefore, cow typing contributes to cow health and welfare while guarding the economic interests of producers, particularly when informed by the predictor variables parity, week of lactation, and milk yield.

Contributing to the opportunity to use cow types for early lactation herd health screening is the availability of high-throughput FTIR technologies, which minimize the costs and time needed for milk sample analysis.

Limitations

Various technical challenges, such as the high number of people involved in taking, shipping, and analyzing the samples or non-analyzable samples, led to observations that missed relevant information, such as blood BHBA or NEFA concentrations or milk FA panels. These observations had to be removed from the data analyses. Since the missing values were assumed to be at random and each observation was considered as standing on its own, no effects of the missing values on the results were to be expected.

CONCLUSIONS

There was a significant interaction term found between PMAS cows and parity compared to healthy cows for C18:1 (P < 0.001) and for C18:0 (P < 0.01). It revealed higher concentrations for PMAS in primiparous and multiparous cows compared to healthy cows, the slope being steeper for primiparous cows. Further, an interaction term was found between PMAS cows and milk yield compared to healthy cows and milk yield for C16:0 (P < 0.05), revealing a steeper slope for the decrease of C16:0 concentrations with increasing milk yield for PMAS compared to healthy cows. The significant associations and interaction terms between cow type, parity, week of lactation, and milk yield as predictor variables and C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1 concentration suggest excellent opportunities for cow herd health screening during the early postpartum period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung), the Bavarian Association for Raw Milk Testing (MPR Bayern e. V.) and the Dairy Herd Improvement Association of Bavaria (LKV Bayern e. V.) for financial support of this study. A special thanks goes to the dairy farms participating in this project. Furthermore, the support of the team of the laboratory of the Clinic for Ruminants at Ludwig-Maximilian-University Munich is highly acknowledged.

Contributor Information

Anne M Reus, Clinic for Ruminants with Ambulatory and Herd Health Services, LMU Munich, 85764 Oberschleissheim, Germany.

Franziska E Hajek, Clinic for Ruminants with Ambulatory and Herd Health Services, LMU Munich, 85764 Oberschleissheim, Germany.

Simone M Gruber, Clinic for Ruminants with Ambulatory and Herd Health Services, LMU Munich, 85764 Oberschleissheim, Germany.

Stefan Plattner, Clinic for Ruminants with Ambulatory and Herd Health Services, LMU Munich, 85764 Oberschleissheim, Germany.

Sabrina Hachenberg, Deutscher Verband für Leistungs- und Qualitätsprüfungen e.V., 53113 Bonn, Germany.

Emil A Walleser, Department of Medical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Srikanth R Aravamuthan, Department of Medical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Rolf Mansfeld, Clinic for Ruminants with Ambulatory and Herd Health Services, LMU Munich, 85764 Oberschleissheim, Germany.

Dörte Döpfer, Department of Medical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA SHARING

Given that the data belong to the producers, it is not possible to share the data set widely. The data and software code may be shared upon request.

Literature Cited

- Bauman, D. E., and Griinari J. M... 2003. Nutritional regulation of milk fat synthesis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 23:203–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A. W. 1995. Regulation of organic nutrient metabolism during transition from late pregnancy to early lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 73:2804–2819. doi: 10.2527/1995.7392804x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorea, J. R. R., French E. A., and Armentano L. E... 2017. Use of milk fatty acids to estimate plasma nonesterified fatty acid concentrations as an indicator of animal energy balance. J. Dairy Sci. 100:6164–6176. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjalbert, F., Nicot M. C., Bayourthe C., and Moncoulon R... 2001. Ketone bodies in milk and blood of dairy cows: relationship between concentrations and utilization for detection of subclinical ketosis. J. Dairy Sci. 84:583–589. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74511-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geishauser, Leslie T., K., Kelton D., and Duffield T... 2001. Monitoring for subclinical ketosis in dairy herds. Compend. Contin. Educ. Pr. Vet. 23:S65–S71. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, F., Schmidely R., Sauvant D., and Doreau M... 2008. Digestion of fatty acids in ruminants: a meta-analysis of flows and variation factors: 2. C18 fatty acids. Animal. 2:691–704. doi: 10.1017/S1751731108002036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohary, K., Overton M. W., Von Massow M., LeBlanc S. J., Lissemore K. D., and Duffield T. F... 2016. The cost of a case of subclinical ketosis in Canadian dairy herds. Can. Vet. J. 57:728–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J. L., LeBlanc S. J., and Duffield T. F... 2013. Ketosis treatment in lactating dairy cattle. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 29:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J., van Dorland H. A., Bruckmaier R. M., and Schwarz F. J... 2011. Milk fatty acid profile related to energy balance in dairy cows. J. Dairy Res. 78:479–488. doi: 10.1017/S0022029911000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt, T. H. 2000. Ruminant adaptation to negative energy balance. Influences on the etiology of ketosis and fatty liver. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 16:215–230, v. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30102-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loften, J. R., Linn J. G., Drackley J. K., Jenkins T. C., Soderholm C. G., and Kertz A. F... 2014. Invited review: palmitic and stearic acid metabolism in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 97:4661–4674. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-7919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandujano Reyes, J. F., Walleser E., Sawalski A., Anklam K., and Dopfer D... 2023. Dynamics of metabolic characteristics in dairy cows and their impact on disease-free survival time. Prev. Vet. Med. 210:105807. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2022.105807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S., Nydam D. V., Lock A. L., Overton T. R., and McArt J. A. A... 2016. Short communication: association of milk fatty acids with early lactation hyperketonemia and elevated concentration of nonesterified fatty acids. J. Dairy Sci. 99:5851–5857. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-10920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez, P., Pinedo P. J., Bastias J., Marin M. P., Rios C., Bustamante C., Adaro N., and Duchens M... 2016. The association between β-hydroxybutyrate and milk fatty acid profile with special emphasis on conjugated linoleic acid in postpartum Holstein cows. BMC Vet. Res. 10:50. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0679-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogalski, Z., Pogorzelska P., Sobczuk-Szul M., Mochol M., and Nogalska A... 2015. Influence of BHB concentration in blood on fatty acid content in the milk of high-yielding cows. Med. Weter. 71:493–496. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel, G. R. 2004. Monitoring and testing dairy herds for metabolic disease. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 20:651–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2004.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Reus, A., and Mansfeld R... 2020. Predicting metabolic health status using milk fatty acid concentrations in cows – a review. Milk Sci. Int. 73:7–15. doi: 10.25968/MSI.2020.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rukkwamsuk, T., Geelen M. J. H., Kruip T. A. M., and Wensing T... 2000. Interrelation of fatty acid composition in adipose tissue, serum, and liver of dairy cows during the development of fatty liver postpartum1. J. Dairy Sci. 83:52–59. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(00)74854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, D., Rosenberg Bak M., and Waaben Hansen P... 2021. Development of global fatty acid models and possible applications. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 75:4–20. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12820 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suthar, V. S., Canelas-Raposo J., Deniz A., and Heuwieser W... 2013. Prevalence of subclinical ketosis and relationships with postpartum diseases in European dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 96:2925–2938. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M., Kammer M., Lange H., Plattner S., Baumgartner C., Stegeman J. A., Duda J., Mansfeld R., and Dopfer D... 2018. Identifying poor metabolic adaptation during early lactation in dairy cows using cluster analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 101:7311–7321. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M., Kammer M., Lange H., Plattner S., Baumgartner C., Stegeman J. A., Duda J., Mansfeld R., and Dopfer D... 2019. Prediction model optimization using full model selection with regression trees demonstrated with FTIR data from bovine milk. Prev. Vet. Med. 163:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van, Q. C. D., Knapp E., Hornick J. L., and Dufrasne I... 2020. Influence of days in milk and parity on milk and blood fatty acid concentrations, blood metabolites and hormones in early lactation Holstein cows. Animals. 10:2081. doi: 10.3390/ani10112081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Haelst, Y. N., Beeckman A., Van Knegsel A. T., and Fievez V... 2008. Short communication: elevated concentrations of oleic acid and long-chain fatty acids in milk fat of multiparous subclinical ketotic cows. J. Dairy Sci. 91:4683–4686. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]