Abstract

Early T-cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL) has a unique immunophenotype with very early T-cell differentiation. The current study summarises the distinct clinicopathological aspects of ETP-ALL and compares them with non-ETP-ALL. Twenty-nine ETP-ALL and 191 non-ETP-ALL cases were retrieved between 2018 and 2021. A P value was determined for each of the patient charaterisics (Table 1) to see for any significant relationship (P < 0.05) with ETP-ALL versus non-ETP-ALL. Kaplan–Meier log rank test was applied to look for any significant differences in OS for both the ALLs. ETP-ALL had an incidence of 12.6% out of total T-Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL/LBL) in the past 3-years. Compared to non-ETP-ALL, ETP-ALL cases were associated with lower median age and male-to-female ratio. There was no statistically significant difference in the complete remission rate between both the subtypes. ETP-ALL was seen to be associated with high induction failure and relapse rate compared to non-ETP-ALL. To summarise, since the 2-year OS was poor compared to western research (for both ALLs), an intensive chemo-regimen should be implemented in the current situation. Some unusual markers were observed on flow-cytometry (ETP-ALL), which can be useful for MRD quantification, prognosis, and further trials for newer targeted therapies.

Keywords: ETP-ALL, Non-ETP-ALL, Complete remission, Relapse, Induction failure

Introduction

The immunophenotype of ETP-ALL is distinct, with very early T-cell differentiation. It constitutes around 10% of all T-ALL/LBL cases. Previously T-ALL/LBL cases were classified based on stage of differentiation (pro, pre, cortical and medullary). Recent 2016 classification includes the pre and pro categories into ETP-ALL [1, 2].

Prior research has shown that this unique subtype has higher risk and higher likelihood of induction failure than non-ETP-ALL, thus requires a more aggressive treatment strategy [1, 3]. The current study's goal is to compare both the subtypes and summarise the distinct characteristics of ETP-ALL in the Indian population.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-nine ETP-ALL and, for comparison, 191 non-ETP-ALL cases were retrieved between 2018 and 2021. All relevant clinical and laboratory data were collected and reviewed. A P value was determined for each of the patient charaterisic (Table 1) to see for any significant relationship (P < 0.05) between ETP-ALL versus non-ETP-ALL. Either Mann Whitney U-test or the Chi-Square test were applied, based on the type of characteristic.

Table 1.

All important patient characteristics for ETP-ALL and non ETP-ALL along with a comparative analysis

| ETP-ALL (n-29) | Non ETP-ALL (n-191) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female ratio | 1.07:1 | 2:01 | |

| Median age | 24 yrs (6–46 yrs) | 14 yrs (2–32 yrs) | |

| Mediastinal mass | 10/28 (36%) | 85/157 (54%) | 0.072 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 17/27 (62.9%) | 108/157 (69%) | 0.549 |

| Generalised lymphadenopathy | 14/22 (64%) | 99/131 (76%) | 0.238 |

| CSF involvement | 4/23 (17.3%) | 42/142 (29%) | 0.226 |

| Hb (median) | 8.05 gm/dl (1.6–13 gm/dl) | 8 gm/dl (5.9–15 gm/dl) | .0251 |

| WBC (median) | 15.32 × 103/L (0.66–380 × 103/L) | 149.5 × 103/L (0.31–685 × 103/L) | < .00001 |

| Platelets (median) | 95 × 103/L) (12–410 × 103/L) | 31.5 × 103/L (4–187 × 103/L) | < .00001 |

| BM aspirate blast % (median) | 80% (51–95%) | 91% (25–98%) | 0.00076 |

| LDH (median) | 489 IU/L (192–3828 IU/L) | 2156 IU/L (159–9528 IU/L) | < .00001 |

| Aberrant cytogenetics | 3/16 (19%) | 10/92 (11%) | 0.371 |

| CR | 16/29 (55%) | 109/191 (57%) | 0.847 |

| Induction failure | 6/29 (21%) | 13/191 (7%) | 0.04 |

| Relapse | 6/16 (38%) | 27/191 (14.2%) | 0.014 |

All the parameters with significant P values have been highlighted

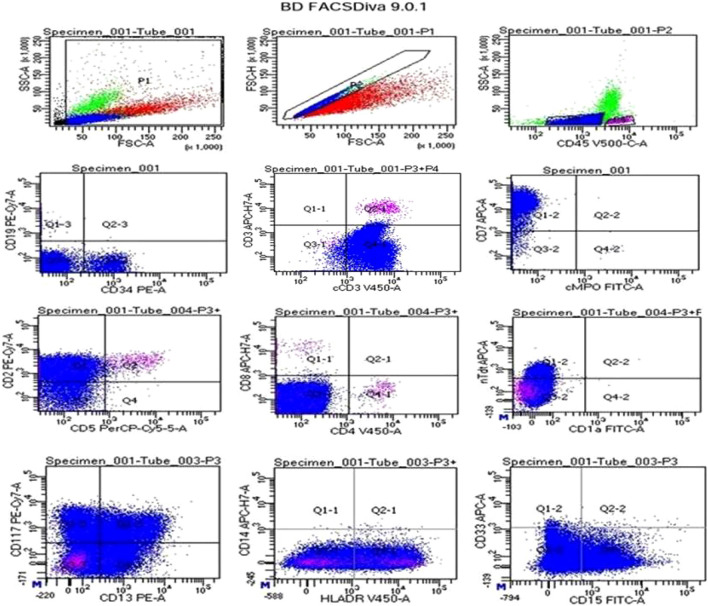

Flow cytometry (FACS-Canto eight colour, with BD Diva software) was done either on BM aspirate or peripheral blood (PB). Two panels of antibodies were used, with the primary panel consisting of cCD3, cMPO, cCD79a, CD34, CD19, CD7, sCD3 and the secondary panel comprising HLA-DR, CD64, CD14, CD20, CD13, CD15, CD117, CD33, CD14, CD4, CD1a, CD99, CD5, CD2, CD8 and Tdt. Diagnosis was made using the following criteria: (1) absent/ < 5% cells positive for CD1a and CD8 expression, (2) absent/dim CD5 expression (< 75% of cells positive), and (3) at least 25% cells positive for > = 1 myeloid/stem cell markers but cMPO negative. Along with cCD3, the lymphoblasts may also express other immature T-cell markers [2]. Near-ETP-ALL (CD5 expression of > 75%), a new subtype that had been proposed lately, was also explored [3]. Short-term culture technique was used for cytogenetics followed by phase-contrast microscopy.

Post-induction BM was done on the 28th day to look for treatment response. As per NCCN guidelines, CR was defined [4]. During follow-up, patients with peripheral blasts or persistent pancytopenia were subjected to a second BM examination. On the 8th day of induction, a CSF examination was performed to look for involvement.

The Berlin, Frankfurt, Muenster (BFM-90) protocol was most commonly used. The hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (hyper CVAD) protocol were administered to patients planned for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or who did not respond to BFM-90. HSCT was mostly opted in patients with relapse. Lastly, for both the groups (ETP-ALL and non-ETP-ALL), Kaplan-meir log rank test was applied to look for any significant differences in OS.

Results

Table 1 represents the essential patient characteristics as well as a comparative analysis for both T-ALLs. After comparison, all the parameters with a significant P value have been highlighted.

In flow cytometry (ETP-ALL), we had two patients with near-ETP-ALL immunophenotype. Additionally, we observed positivity for a number of unusual markers, including CD20 with coexpression of CD38(1), CD66c(1), CD11c(1), CD56(1), and CD79a(2) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow-cytometry (ETP-ALL): lymphoblasts gated using dim CD45 expression, had moderate to bright expression for CD34, cCD3, CD7, CD2, Tdt, CD117, CD13, HLADR, and CD15 while negative for sCD3, CD19, cMPO, CD5, CD4, CD8, CD1a, CD33 and CD14

Various cytogenetic aberrations seen among ETP-ALL cases were translocation (2; 22)(1), trisomy 8(1), and 13q deletion(1). Likewise in non-ETP-ALL, hyperdiploidy(4), complex karyotype(2), 9p gain(1), 11p gain(1), 11q deletion(1), and 16q deletion(1) were seen.

Although the CR rates for the two ALLs were comparable, we observed a substantial variation in the rates of relapse and induction failure. Among the patients with relapse we encountered 2 and 3 patients with multiple instances of relapse in ETP-ALL and non-ETP-ALL, respectively. In two cases of relapsed ETP-ALL, allogenic HSCT was performed. There were no significant differences in survival for either T-ALL.

Discussion

The Indian incidence (13%) and the median age (14-years) for ETP-ALL were lower compared to western studies (17% and 24-years) [1, 3, 5–8]. We also saw that ETP-ALL cases had a higher median age than non-ETP-ALL, which was consistent with the literature [1, 5, 6].

The association of higher incidence of mediastinal mass with non-ETP-ALL was similar to previous research [1, 5–8]. Like Genesca et al., no significant correlation was seen between CSF involvement and ETP-ALL (P > 0.05), although this was not concordant with Jain et al. and Coustan-Smith et al. findings [1, 6, 9]. Hepatosplenomegaly and generalised lymphadenopathy were found to be equally common in both the ALLs and had no significant association, similar to previous studies [6].

Like previous research, significant association of lower WBC counts, lower LDH levels, and higher platelet counts were seen with ETP-ALL [5, 6, 8]. However contrastingly, ETP-ALL subjects showed association with lower BM blast percentage than non-ETP-ALL (P < 0.00076) [1, 8]. On morphometric analysis we saw ETP-ALL lymphoblasts to be larger, with more cytoplasm, and more open chromatin than non-ETP-ALL, and they were frequently PAS negative (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a The lymphoblast of ETP-ALL appeared larger with more cytoplasm and open chromatin than b non-ETP-ALL lymphoblast. c PAS staining showed no block positivity in most ETP-ALL lymphoblast compared to d non-ETP-ALL lymphoblast which showed strong block positivity (all images ×1000 oil immersion)

Despite sharing transcriptional similarity with ETP-ALL, the near-ETP-ALL immunophenotype is considered to have a better prognosis. The outcomes of earlier studies for near-ETP-ALL and non-ETP ALL were comparable [3]. Two such cases were seen, of which the one had CR post first induction and the other had multiple induction failures [3]. However both the cases attained CR and had a good OS.

We also saw positivity for few uncommon markers like, CD66c, CD11c, CD56, CD79a, and CD20 with CD38 coexpression. Recently, anti-CD38 targeted therapy and CD56 based MRD risk stratification had been used for T-ALLs, which can be applied in current situation [10, 11].

Recurrent cytogenetic aberrations mostly associated with T-ALLs are hyperdiploidy, hypodiploidy, pseudodiploidy, partial chromosome loss, and translocations (involving 7p, 7q, and 14q) [2]. Among 3 ETP-ALL cases with cytogenetic aberrations 2 were in the paediatric age group, and all had a dismal prognosis. However, no significant association (P-0.371) was seen in both present and previous studies [1, 8]. Although the St. Judes cohort, revealed multiple chromosome gains and losses, along with 13q abnormalities among ETP-ALL patients [9]. Unlike ETP-ALL, non-ETP-ALL cases with cytogenetic abnormalities did well, and no clustering was observed in any age group.

ETP-ALL cases were associated with a high relapse rate (> 80% cases relapsing within a year of remission), however both the subtypes had a similar CR rates. Similar findings were also observed by Zhang et al. [8] ETP-ALL cases were also seen to be associated with high induction failure rate (21%, 6/29) like Genesca et al. and Coustan-Smith et al. [6, 9]. However, Patrick et al. and Jain et al. didn't find any significant difference in induction failure rates among both the ALLs since they followed a more intense regimen based on MRD stratification [1, 12].

Similarly to present study, Zhang et al. and Jain et al. reported no significant difference in OS rates for both the ALLs [1, 8]. Whereas other western studies reported a substantial difference in the survival rates [6, 9, 13, 14]. The 2-year OS for present study for both the ALLs were lower compared to the Western counterparts (ETP-ALL-14.2% and non-ETP-ALL-16.2%) (Fig. 3) [1, 6, 8].

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival for both ETP-ALL and non-ETP-ALL

In recent advances, multiple targeted therapies are on trials, like, Dasatinib (targeting NUP214-ABL1), anti-CD123 antibody, Ruxolitinib (JAK-2 inhibitors), daratumumab (anti-CD38 antibody), CAR-T cells targeting CD5 and CD7 and, anti-CD33 antibody [10, 15–19]. Furthermore, personalised chemoregimens are being developed based on computer based analysis of genetic signatures [20].

To summarise, since the 2-year OS was poor compared to western research (for both ALLs), an intensive chemo-regimen should be implemented in the current situation. Cytogenetic aberrations conferred a poor outcome among ETP-ALL and were more common among the paediatric population, implying the need of a comprehensive cytogenetic workup. Near-ETP-ALL had a comparatively better outcome, therefore a qualitative and quantitative CD5 flow analysis is essential. Some unusual markers were positive in ETP-ALL highlighting the need to explore various markers with their expression patterns, which may be useful for MRD quantification, prognostication and paving the way for trials of newer targeted therapies.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Immanuel Paul Thayakaran (Senior Resident; Dept. of Oncopathology, Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute, Ahmedabad).

Author Contributions

The manuscript has been read thoroughly and contributed by all the concerned authors. The requirement for authorship as mentioned in the instructions has been met duly. Authors are responsible for correctness of the statements provided in the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Internal Ethics Committee Approval

All the approvals had been taken from the Institutional review board. Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of institute in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.All the necessary permission has been taken for collection and analysis of materials and data from the concerned authorities.

Consent to Participate

All necessary informed written consent have been taken priorly.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anurag Saha, Email: anurag.afmg@gmail.com.

Beena Brahmbhatt, Email: beena.brahmbhatt@gcriindia.org.

Varnika Rai, Email: vrachievers@gmail.com.

Sneha Kakoty, Email: dr.snehakakoty@gmail.com.

Jyoti Sawhney, Email: jyoti.sawhney@gcriindia.org.

References

- 1.Jain N, Lamb AV, O'Brien S, et al. Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ETP-ALL/LBL) in adolescents and adults: a high-risk subtype. Blood. 2016;127(15):1863–1869. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-661702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowitz MJ, Chan JKC, Bene MC, Arber DA, et al. T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoetic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4. Lyon: International agency for research on cancer (IARC); 2017. pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita K, Jain N, Kantarjian H, et al. Outcome of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: focus on near-ETP phenotype and differential impact of nelarabine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):589–598. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ALL response criteria. In: NCCN guidelines for patients. 2021. p 33. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/all-patient.pdf

- 5.Chopra A, Bakhshi S, Pramanik SK, et al. Immunophenotypic analysis of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A CD5-based ETP-ALL perspective of non-ETP T-ALL. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92(3):211–218. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genescà E, Morgades M, Montesinos P, et al. Unique clinico-biological, genetic and prognostic features of adult early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2020;105(6):294–297. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.225078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iqbal N, Sharma A, Raina V, et al. Poor response to standard chemotherapy in early T-precursor (ETP)-ALL: a subtype of T-ALL associated with unfavourable outcome: a brief report. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2014;30(4):215–218. doi: 10.1007/s12288-013-0329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Qian JJ, Zhou YL, et al. Comparison of early T-cell precursor and non-ETP subtypes among 122 Chinese adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1423. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coustan-Smith E, Mullighan CG, Onciu M, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukemia: a subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):147–156. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tembhare PR, Sriram H, Khanka T, et al. Flow cytometric evaluation of CD38 expression levels in the newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and the effect of chemotherapy on its expression in measurable residual disease, refractory disease and relapsed disease: an implication for anti-CD38 immunotherapy. J Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000630. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuhrmann S, Schabath R, Möricke A, et al. Expression of CD56 defines a distinct subgroup in childhood T-ALL with inferior outcome. Results of the ALL-BFM 2000 trial. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(1):96–103. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick K, Wade R, Goulden N, et al. Outcome for children and young people with Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated on a contemporary protocol, UKALL 2003. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(3):421–424. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haydu JE, Ferrando AA. Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2013;20(4):369–373. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283623c61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEwan A, Pitiyarachchi O, Viiala N. Relapsed/refractory ETP-ALL successfully treated with venetoclax and nelarabine as a bridge to allogeneic stem cell transplant. Hemasphere. 2020;4(3):379. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelova E, Audette C, Kovtun Y, et al. CD123 expression patterns and selective targeting with a CD123-targeted antibody-drug conjugate (IMGN632) in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104(4):749–755. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.205252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Zhang L, Huang J, et al. Dasatinib and chemotherapy in a patient with early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and NUP214-ABL1 fusion: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(5):3979–3984. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maude SL, Dolai S, Delgado-Martin C, et al. Efficacy of JAK/STAT pathway inhibition in murine xenograft models of early T-cell precursor (ETP) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(11):1759–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-580480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mamonkin M, Rouce RH, Tashiro H, Brenner MK. A T-cell-directed chimeric antigen receptor for the selective treatment of T-cell malignancies. Blood. 2015;126(8):983–992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khogeer H, Rahman H, Jain N, et al. Early T precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma shows differential immunophenotypic characteristics including frequent CD33 expression and in vitro response to targeted CD33 therapy. Br J Haematol. 2019;186(4):538–548. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frismantas V, Dobay MP, Rinaldi A, et al. Ex vivo drug response profiling detects recurrent sensitivity patterns in drug-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(11):e26–e37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-738070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]