Abstract

Permanent supportive housing is an effective intervention for stably housing most people experiencing homelessness and mental illness who have complex support needs. However, high-risk behaviours and challenges are prevalent among this population and have the potential to seriously harm health and threaten housing tenures. Yet, the research on the relationship between high-risk issues and housing stability in permanent supportive housing has not been previously synthesized. This rapid review aimed to identify the housing-related outcomes of high-risk behaviours and challenges in permanent supportive housing settings, as well as the approaches used by agencies and residents to address them. A range of high-risk behaviours and challenges were examined, including risks to self (overdose, suicide/suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, falls/fall-related injuries), and risks to multiple parties and/or building (fire-setting/arson, hoarding, apartment takeovers, physical/sexual violence, property damage, drug selling, sex trafficking). The search strategy included four components to identify relevant academic and grey literature: (1) searches of MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, and CINAHL Plus; (2) hand searches of three journals with aims specific to housing and homelessness; (3) website browsing/searching of seven homelessness, supportive housing, and mental health agencies and networks; and (4) Advanced Google searches. A total of 32 articles were eligible and included in the review. Six studies examined the impacts of high-risk behaviours and challenges on housing tenancies, with overdose being identified as a notable cause of death. Twenty-six studies examined approaches and barriers to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH programs. These were categorized into eight types of approaches: (1) clinical, (2) relational/educational, (3) surveillant, (4) restrictive, (5) strategic, (6) design-based, (7) legal, and (8) self-defence. Consistent across all approaches was a lack of rigorous examination of their effectiveness. Further, some approaches that are legal, restrictive, surveillant, or strategic in nature may be used to promote safety, but may conflict with other program objectives, including housing stability, or resident empowerment and choice. Research priorities were identified to address the key evidence gaps and move toward best practices for preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in permanent supportive housing.

Keywords: Permanent supportive housing, Housing first, Risk management, Mental illness, Safety, Violence, Overdose, Apartment takeovers, Fire, Review

Introduction

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) is a best practice intervention for stably housing people experiencing homelessness and mental illness who have complex support needs [1–3]. PSH involves the provision of permanent affordable housing, along with community-based mental health recovery-oriented supports, such as intensive case management or assertive community treatment. Research has demonstrated that 80–90% of people remain stably housed in PSH after up to six years [1, 4–9]. Yet, supporting people’s mental health recovery journeys can be challenging and there remains a small group of individuals who experience difficulties in PSH that can result in housing loss, relocation, recurrent homelessness, or rehospitalization [10–13]. Given the deleterious effects of housing loss among people with mental illness and histories of homelessness, it is critical to identify the risk factors that may lead to negative outcomes in PSH.

A sizeable body of research over the past decade has focused on predictors of housing outcomes in PSH. However, these studies have yielded limited evidence on the factors associated with PSH housing loss. In an early examination of data from a multisite randomized controlled trial of Housing First, an intervention often delivered as PSH, findings were only able to predict 3.8% of the variance in housing instability outcomes after 12 months using sociodemographic, clinical, and housing history variables [14]. Subsequent analyses from the same trial with a more stringent definition of housing stability and set of predictors produced an improved model, but ultimately yielded the same conclusion: Although certain individual characteristics are risks factors associated with difficulties establishing housing stability, the researchers concluded that it was not possible to accurately predict who would be unsuccessful in Housing First after 24 months [15]. Studies examining associations between service use and housing stability have also produced relatively small effect sizes [16]. An implicit assumption of these studies is that individual characteristics and behaviour patterns can be used to predict a trajectory of future housing stability problems. However, a person’s housing stability is dynamically shaped by their housing and supports, as well as the broader environment [17]. These contextual factors are only partially captured in research examining predictors of housing outcomes in PSH. In particular, sudden, unplanned, and acute events that may alter a housing trajectory have not been studied. Further, the interventions used by PSH service providers, either successfully or unsuccessfully, to mitigate the potential harms of such events have not been thoroughly examined in research on PSH housing outcomes. Accordingly, acute events and the accompanying risk management approaches used by PSH service providers may hold promise for potentially identifying at-risk individuals and intervening to prevent housing loss.

A range of high-risk behaviours and challenges may seriously harm the health of residents and threaten their housing tenures in PSH. These may include risks to self (e.g., overdose, suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, and falls), or risks to multiple parties and buildings (e.g., fires, hoarding, apartment takeovers, violence, property damage, drug selling, sex trafficking). Some of these incidents may also involve PSH residents being victimized by other people. High-risk behaviours and challenges are prevalent among people with mental illness, substance use problems, and histories of homelessness, and in PSH settings. For example, in an examination of over 12,000 supportive housing applicants in Toronto, Canada, 20.3% had a history of suicide attempts, 17.7% were perpetrators or victims of physical assault, 14.7% had engaged in non-suicidal self-injury, 8.0% had fire safety concerns, 7.9% had damaged property, and 5.9% engaged in hoarding behaviours [18]. Another study with a more rigorous observational assessment found that 18.5% of formerly homeless individuals in PSH exhibited hoarding behaviours [19]. Further, in a study of supportive housing programs for formerly homeless older adults aged 45–80 years, most have experienced a fall in the past year, many of which resulted in a serious injury requiring medical care [20]. The overdose crisis has also disproportionally affected homeless and precariously housed populations. In San Francisco, overdoses were found to be nearly twenty times higher among residents of single room occupancy hotels, including some supportive housing programs, than non-single room occupancy residents [21]. Given both their prevalence and severity, many high-risk behaviours and challenges are burdensome for service providers in the supportive housing sector to manage and may be important intervention targets [22, 23]. These types of problems can also threaten program fidelity and sustainability of PSH programs due to loss of key relationship connections and knowledge among support teams [24, 25].

Several studies have examined the effects of PSH on high-risk behaviours and challenges. Housing First was found to reduce violent and nonviolent victimization, whereas the intervention had minimal effects on suicide attempt rates [26–30]. Yet, there are key evidence gaps with regard to other high-risk behaviours and challenges. For example, few studies have examined severe substance use-related harms, including overdoses, in PSH [31]. Other housing challenges, such as hoarding and apartment takeovers, have also not been studied in the context of PSH. Further, the extent to which high-risk issues affect housing stability in PSH has not been previously synthesized. As the research on high-risk behaviours and challenges suggests that some of these types of issues may be preventable or modifiable in the context of PSH using evidence-based approaches and best practices, a rapid review was undertaken to understand the practices that PSH programs use to manage high-risk behaviours and challenges, and the effectiveness of these approaches.

This rapid review aimed to identify the approaches and barriers to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in supportive housing settings, with a focus on how these issues affect housing tenancies. Rapid reviews provide a streamlined approach to synthesizing evidence that can be efficiently disseminated to and used by sectoral decision-makers and service providers [32]. A rapid review was selected given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, worsening overdose crisis, affordable housing shortages, and inaccessible mental health services in many communities, which have exacerbated service delivery challenges in PSH settings [22, 33]. In this context, a timely synthesis of evidence can produce needed information on research gaps and inform service delivery approaches. The two research questions were: (1) What impacts do high-risk behaviours and challenges have on housing tenancies in PSH? and (2) What are the approaches and barriers to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH programs? For this rapid review, high-risk behaviours and challenges were defined as any critical events or serious behaviours that are potentially life-threatening and/or jeopardize a person’s housing tenure. The latter may be due to eviction or other causes, such as prolonged hospitalization, justice system involvement, or new support needs caused by an injury that cannot be met by individuals’ current supportive housing programs. The rapid review was not prospectively registered.

Method

This rapid review followed guidelines by King and colleagues [34], with additional considerations for grey literature searching by Godin and colleagues [35]. Two sets of high-risk behaviours and challenges were examined: (1) risks to self (overdose, suicide/suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, falls/fall-related injuries); and (2) risks to multiple parties and/or building (fire-setting/arson, hoarding, apartment takeovers, physical/sexual violence, property damage, drug selling, sex trafficking). Additional high-risk issues not identified at the outset of the review were also considered. A PICO framework was used to further establish review parameters, define key terms, and inform the search strategy (Table 1).

Table 1.

PICO framework

| P | Population | People exiting homelessness |

| People with mental illness and/or who use substances | ||

| I | Intervention | PSH with onsite or offsite supports for single adults |

| Alignment with a Housing First approach was not required | ||

| Single room occupancy models were included if they offered some form of supportive services | ||

| C | Comparison | Not applicable |

| O | Outcome | Primary research question: approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges used by service providers; service providers’ experiences in supporting residents with high-risk behaviours and challenges; residents’ experiences of high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH |

| Secondary research question: housing retention and loss; returns to homelessness; death |

PSH Permanent supportive housing

Three academic databases were subsequently searched on November 14, 2022: (1) MEDLINE, (2) APA PsycINFO, and (3) CINAHL Plus. The following string of keywords was used: (homeless* OR mental illness OR mental disorder* OR psychiatric disorder OR substance use disorder OR drug* OR alcohol OR dual diagnosis OR dually diagnosed OR concurrent disorder*) AND (Housing First OR Pathways to Housing OR supportive housing OR supported housing) AND (suicid* OR self-harm OR self-injur* OR fire OR arson OR pyro* OR hoard* OR overdose OR poisoning OR toxicity OR adverse OR withdrawal OR intoxicat* OR drunk* OR inebriat* OR violen* OR assault* OR takeover* OR unwanted OR unwelcome OR cuckooing OR risk OR injur* OR death OR dying OR died OR fall* OR traffick* OR sexual exploitation OR property damage OR property offense* OR drug dealing OR drug trade OR drug selling). A multi-purpose field search was used with the MEDLINE and APA PsycINFO databases. Three journals with aims specific to housing and homelessness that are partially or not indexed in the three academic databases were also hand searched: (1) European Journal of Homelessness, (2) International Journal on Homelessness, and (3) Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness.

Grey literature was searched using a modified search strategy informed by Godin and colleagues [35]. This included: (1) website browsing/searching and (2) Advanced Google searches. Seven websites of homelessness, supportive housing, and mental health agencies and networks (Australian Alliance to End Homelessness, Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, Corporation for Supportive Housing, FEANTSA, The Homeless Hub, National Alliance to End Homelessness, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) were searched between November 2022-January 2023. An abbreviated list of keywords was used for the website and Advanced Google searches. Up to 200 consecutive records were reviewed in the Advanced Google searches.

Articles in both the academic database and grey literature searches were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) had findings specific to one or more high-risk behaviours and challenges in the context of PSH, which were linked to either personal experiences of residents, support approaches or experiences of service providers, or housing tenure (including death); (2) were a peer-reviewed journal article, book or book chapter, or technical report; (3) involved original research, case study, a review, or program evaluation; and (4) were published between January 1, 1992-October 31, 2022 (advanced publication articles were permitted). Exclusion criteria were: dissertations, conference abstracts, newspaper media, and blogs; studies examining transitional housing programs; and studies examining supportive housing for families or individuals experiencing interpersonal violence.

Academic articles were first screened by the lead author for relevance at the title and abstract levels. A highly conservative approach for exclusion was used during the screening phase so that all articles with slight applicability to the review were retained and further assessed. A full-text review was then completed to determine and summarize relevant findings from the articles that met the review eligibility criteria. A similar approach was used with the grey literature searches. Document titles and any accompanying summarizations were screened. A full-text review of potentially relevant documents was then completed. The lead author performed the searches, screening, and full-text reviews. A co-author (CM) reviewed 15% of the articles’ data extractions in the full-text reviews for accuracy, which demonstrated high consistency in assessments. Eligible articles were then narratively synthesized, and approaches for addressing high-risk behaviours and challenges were categorized thematically. The lead author completed the initial labelling and defining of the thematic categories, which were then reviewed by and discussed with a co-author (CM), producing consensus assessments.

Results

Description of articles in rapid review

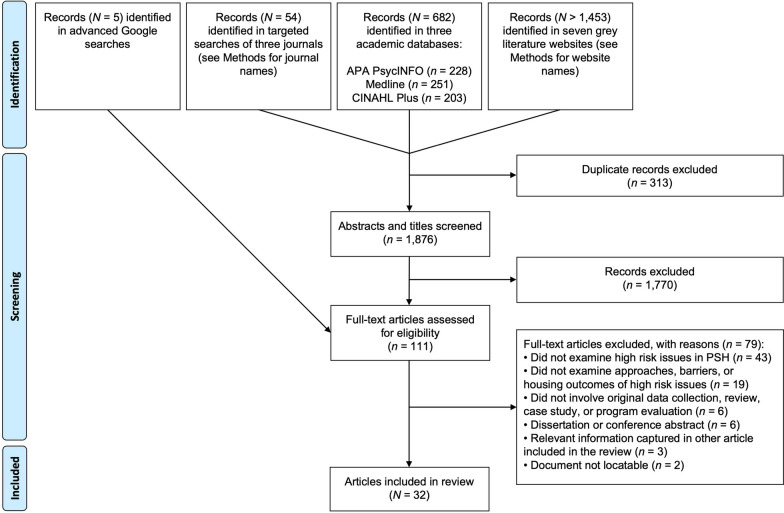

A total of 32 articles were eligible and included in the review (Fig. 1). Six studies examined the impacts of high-risk behaviours and challenges on housing tenancies (research question (1), whereas twenty-six studies examined approaches and barriers to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH programs (research question 2). Most studies were conducted in North America, with 15 from the United States and 12 from Canada. Two articles were from a single study in France, two articles were from a single study in Australia, and one article was from Norway. There was variability in PSH models across the studies and details about support models were inconsistent, making it unfeasible to examine differences in findings by program model and philosophy (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Search summary and article selection process. Note. Records could not be enumerated for a part of the grey literature website search that involved browsing relevant webpages. Hence, N > 1,453

Table 2.

Summary of articles in rapid review

| Year | References | Article type | Location | Housing and support model | High-risk issues examined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Ivsins et al. [36] | Qualitative study | Vancouver, Canada | PSH program for people with physical, mental health, and substance use problems; primary care and substance use services (opioid agonist therapy and prescribed safer support) available onsite, as well as a drug consumption site and managed alcohol program | Overdose |

| 2022 | Nixon & Burns [37] | Qualitative study | Western Canada | 70-bed PSH program for older adults (> 55 years) with experiences of homelessness and complex health problems; health services provided onsite, including managed alcohol and tobacco programs, and onsite opioid agonist therapy dispensing | Falls caused by alcohol intoxication |

| 2022 | Wood et al. [38] | Program evaluation | Perth, Australia | Housing First program with a collaborative support model that involved over 30 participating organizations and had fairly good adherence to Australian Housing First principles | Property damage; interpersonal threats |

| 2021 | Bardwell et al. [39] | Qualitative study | Vancouver, Canada | Women-only, single room occupancy-based supportive housing program with wireless overdose response button system installed in residential units | Overdose; violence |

| 2021 | Chavez et al. [40] | Study protocol | Large Midwestern city, United States | Housing First for youth (model not described) with adjunct intervention of cognitive therapy for suicide prevention | Suicide attempts |

| 2021 | Corporation for Supportive Housing [41] | Cross-sectional survey | New York State, United States | Various supportive housing programs, including scattered- and single-site models | Overdose |

| 2021 | Milburn et al. [42] | Exploratory mixed-methods study | Los Angeles, United States | Various PSH programs, including scattered- and single-site models | Trespassing; uninvited guests; weapons possession |

| 2021 | Roebuck et al. [43] | Implementation and outcome program evaluation | Ottawa, Canada | Scattered-site, condominium-based Housing First program, with slight deviations from the Pathways Housing First model | Apartment takeovers |

| 2021 | Tinland et al. [44] | Randomized controlled trial | Paris, Marseille, Toulouse, and Lille, France | Scattered-site Housing First with assertive community treatment for people with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder and fidelity to the Pathways Housing First model | Suicide and overdose as causes of death |

| 2020 | Vallesi et al. [45] | Program evaluation | Perth, Australia | Housing First program aligned with the core principles of European Housing First | Threatening neighbours and violent relationships; apartment takeovers |

| 2019 | Bardwell et al. [46] | Qualitative study | Vancouver, Canada | Single room occupancy hotels with adjunct peer-led overdose response intervention | Overdose |

| 2019 | Brar et al. [47] | Case report | Vancouver, Canada | Single room occupancy-based supportive housing program | Overdose |

| 2019 | Friesinger et al. [48] | Ethnographic qualitative study | Southern Norway | Seven supported housing programs for people with mental illness of variable size; mix of single-site buildings and small houses | Fire |

| 2019 | Katz et al. [49] | Randomized controlled trial | Moncton, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver, Canada | Housing First with fidelity to the Pathways Housing First model | Suicide attempts |

| 2018 | Addictions & Mental Health Ontario et al. [50] | Multiple case study | Ontario, Canada | Various supportive housing programs, including two single-site models that employ a hoarding specialist on the support team | Hoarding |

| 2018 | Gutman et al. [51] | Exploratory mixed-methods study | New York City, United States | Two supportive housing programs for formerly homeless adults | Falls |

| 2018 | Henwood et al. [52] | Ethnographic qualitative study | Los Angeles, United States | Various PSH programs, including scattered- and single-site models | Guest-based victimization, including violence and stalking; drug selling and availability |

| 2018 | Rhenter et al. [53] | Qualitative study | Paris, Marseille, Toulouse, and Lille, France | Scattered-site Housing First with assertive community treatment for people with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder and fidelity to the Pathways Housing First model | Violence |

| 2018 | Tiderington [54] | Multi-method qualitative study | Large urban city, United States | Two scattered-site PSH programs, one of which had a transitional housing feeder program | Apartment takeovers |

| 2017 | Chang [55] | Docent method qualitative study | San Francisco, United States | Ten supportive housing buildings operated by an agency that uses a Housing First approach | Drug selling and availability |

| 2017 | Cusack & Montgomery [56] | Retrospective administrative data analysis | United States | HUD-VASH PSH program for veterans | Suicide and self-injury |

| 2017 | The Dream Team [57] | Community-based participatory, multi-methods research study | Toronto, Canada | Non-specific (participants lived in carious supportive housing programs or social housing) | Apartment takeovers |

| 2016 | Kriegel et al. [58] |

Explanatory sequential mixed-methods study |

California, United States | Forensic and non-forensic full-service partnerships, with variable fidelity to Pathways Housing First | Neighbourhood crime and drug availability; threatening neighbours |

| 2015 | Henwood, et al. [59] | Observational study | Philadelphia, United States | Pathways Housing First program | Substance and fire-related causes of death |

| 2014 | Distasio et al. [60] | Multiple case study | Canada | Various supportive housing programs | Violence; pedophilia; property damage; hoarding; unwanted visitors |

| 2014 | Silva et al. [61] | Description of adverse events and responses in randomized controlled trial | Moncton, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver, Canada | Housing First with fidelity to the Pathways Housing First model | Stovetop fires; violence; weapon offences; uninvited guests |

| 2013 | Collins et al. [62] | Nonrandomized controlled trial | Seattle, United States | Single-sited Housing First program for chronically homeless adults with severe alcohol use problems | Hostility |

| 2012 | Krüsi et al. [63] | Qualitative study | Unspecified city in British Columbia, Canada | Two minimal-barrier, high-tolerance supportive housing programs for chronically homeless women engaged in sex work | Violence; rape |

| 2009 | Lee et al. [64] | Cross-sectional study | Philadelphia, United States | Supportive independent living program for people with serious mental illness that required sobriety and treatment compliance | Neighbourhood crime against people and property |

| 2009 | Pearson et al. [65] | Exploratory, longitudinal study | New York City, Seattle, San Diego, United States | Three Housing First programs serving people experiencing homelessness and mental illness that are operated by three different agencies (Pathways Housing First, DESC, and REACH) | Interpersonal abuse; property damage |

| 2005 | Campanelli et al. [66] | Program description and evaluation | New York City and Montgomery County, United States | Housing with various structures and supports for people with mental illness | Violence; arson |

| 1996 | Sohng [67] | Process evaluation | Urban county in Washington State, United States | Two-bedroom apartment-based housing program with onsite supports for older adults with mental illness | Sexual and verbal aggression |

PSH: permanent supportive housing

A range of high-risk behaviours and challenges were examined across the two research questions. These included: apartment takeovers, trespassing, and uninvited guests (n = 7); overdose and substance-caused fatalities (n = 7); non-specified violence and hostility (n = 7); suicide and self-injury (n = 5); fires and arson (n = 4); interpersonal threats and abuse, including from neighbours (n = 4); drug availability and selling (n = 3); property damage (n = 3); sexual violence, including assault, harassment, and stalking (n = 3); falls and fall-related injuries (n = 2); hoarding (n = 2); neighbourhood crime toward people and property (n = 2); and weapons possession (n = 2). Pedophilia and verbal aggression were each examined in a single article.

Outcomes of high-risk behaviours and challenges on housing tenure

Six studies examined housing-related outcomes associated with various high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH (Table 3). Four studies examined correlates of PSH exits. Greater hostility, as measured by distress caused by emotion dysregulation, interpersonal arguments, and violent urges, was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of leaving a single-site Housing First program for chronically homeless adults with severe alcohol use problems [62]. In contrast, suicide or self-injury, neighbourhood crime (offences against property and people), interpersonal abusiveness, and property damage were not significantly associated with PSH exits in three other studies [56, 64, 65]. Two studies examined causes of death in Housing First. In a randomized controlled trial of Housing First conducted in France, overdose was the leading cause of death (n = 8, 34.8%) among the 23 residents of the intervention group who passed away – a rate higher than the treatment as usual group, which had no overdose deaths [44]. In an earlier observational study of 41 residents who died while participating in a Housing First program, a smaller proportion of deaths were the result of alcoholism or drug intoxication (n = 4, 9.8%) in comparison to the French study, and no residents died from fire-related causes [59].

Table 3.

Housing-related outcomes associated with high-risk behaviours and challenges in permanent supportive housing

| Year | Authors | High-risk issues examined | Housing outcomes examined | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Tinland et al. [44] | Suicide and overdose as causes of death | Death |

34.8% (n = 8) of Housing First resident deaths were from overdose, whereas no participants in treatment as usual group died of overdose 13.1% (n = 3) of Housing First resident deaths were from suicide, whereas 9.1% (n = 1) in treatment as usual group died of suicide |

| 2017 | Cusack & Montgomery [56] | Suicide and self-injury | Exits due to incarceration and returns to homelessness | Suicide or self-injury was not significantly associated with either supportive housing exits due to incarceration or returns to homelessness |

| 2015 | Henwood et al. [59] | Substance and fire-related causes of death | Death |

9.8% (n = 4) of Housing First resident deaths were from alcoholism or drug intoxication No Housing First residents died from fire-related causes |

| 2013 | Collins et al. [62] | Hostility | Housing retention | Greater hostility was significantly associated with increased likelihood of leaving the Housing First program |

| 2009 | Lee et al. [64] | Neighbourhood crime against people and property | Supportive housing departures | Neighbourhood crime level was not significantly associated with departures from supportive housing |

| 2009 | Pearson et al. [65] | Interpersonal abuse; property damage | Housing tenure | No significant differences were found between leavers and stayers in interpersonal abusiveness and property damage |

Approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges

The approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH programs, as described in 26 studies, are summarized in Table 4. Each approach was also categorized as being clinical, relational/educational, surveillant, restrictive, strategic, design-based, legal, or self-defence (see Table 5 for descriptions and examples of each type). Almost all studies (n = 25) examined organizational and support approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges, with five studies also describing how PSH residents responded to such problems. These are described in more detail below.

Table 4.

Approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in permanent supportive housing

| Year | Authors | High-risk issues examined | Risk management approach (type category) | Approach effectiveness and perceptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Ivsins et al. [36] | Overdose | Development and access to an onsite supervised consumption room and safer supply program (clinical and design-based) | Qualitative experiences of residents, including non-use of the consumption room due to interpersonal safety concerns and preference to use alone, and feelings of safety and less use of street-acquired drugs due to access to safer supply |

| 2022 | Nixon & Burns [37] | Falls caused by alcohol intoxication |

Increased monitoring of residents (surveillant) Removal of excess alcohol (restrictive) |

Not meaningfully examined |

| 2022 | Wood et al. [38] | Property damage; interpersonal threats |

Liaise and advocate with housing providers about damage debts (relational/educational) Develop safety strategies (clinical) Provide support to apply for restraining orders (legal) |

Not examined |

| 2021 | Bardwell et al. [39] | Overdose; violence | Installation of overdose response button technology in residential units (design-based) | Qualitative experiences of use by residents, including minimal use of the technology as intended, but use for other emergencies, such as gender-based violence |

| 2021 | Chavez et al. [40] | Suicide attempts | 10-session cognitive therapy for suicide prevention (clinical) | Outcome analyses are planned, but not yet examined |

| 2021 | Corporation for Supportive Housing [41] | Overdose | Naloxone training for staff (clinical) | Not examined |

| 2021 | Milburn et al. [42] | Trespassing; uninvited guests; weapons possession |

Use of a security team to patrol buildings (surveillant) Possession of weapons for self-protection (self-defence) |

Qualitative experiences of residents, including perceptions that patrols were infrequent and inconsistent, yielding minimal effects on trespassing |

| 2021 | Roebuck et al. [43] | Apartment takeovers |

Acquisition of housing units not located on the ground floor (strategic) Case managers support residents to develop healthy support networks and set boundaries with other people (relational/educational) |

Not meaningfully examined |

| 2020 | Vallesi et al. [45] | Threatening neighbours and violent relationships; apartment takeovers |

Transfer residents to more suitable accommodations (strategic) Staff intervene with uninvited guests on behalf of residents (relational/educational) |

Not meaningfully examined |

| 2019 | Bardwell et al. [46] | Overdose | Development of a tenant-led overdose response team to provide naloxone training and distribution (clinical) | Qualitative experiences of residents and staff, demonstrating intervention acceptability and empowerment; however, residents also reported increased emotional distress due to the severity of the overdose crisis and need to administer naloxone to friends |

| 2019 | Brar et al. [47] | Overdose | Implementation of onsite injectable opioid agonist therapy (clinical) | Drug use outcomes over nine months, but no findings specific to overdose |

| 2019 | Friesinger et al. [48] | Fire |

Use of fire detection, alarm, and extinguisher systems (design-based) Staff check-ins (surveillant) Prohibition of lighters for residents with histories of causing fires (restrictive) Automatic timed switches to turn off stoves and temperature sensors (design-based) |

Qualitative experiences of staff and residents, including disablement or misuse of fire safety measures (e.g., bringing in unapproved visitors via emergency and fire exit doors), and concerns about surveillance and restrictiveness |

| 2019 | Katz et al. [49] | Suicide attempts | Use of the MINI Suicidality Subscale as a tool to predict suicide attempts (clinical) | Instrument had high predictive validity of suicide attempts among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness over a 24-month period |

| 2018 | Addictions & Mental Health Ontario et al. [50] | Hoarding | Use of a hoarding specialist on support teams (clinical) | Not examined |

| 2018 | Gutman et al. [51] | Falls | Standardized safety assessment conducted during home visits (clinical) | Identification of environmental fall risks |

| 2018 | Henwood et al. [52] | Guest-based victimization, including violence and stalking; drug selling and availability |

Residents’ isolation at home to avoid drug use (restrictive) Enforcement of visitation program rules (restrictive) |

Qualitative experiences of residents including risk of loneliness associated with the isolation approach and preference among women to be alone due to past traumas involving violence and stalking |

| 2018 | Rhenter et al. [53] | Violence | Residents’ engagement in sedentary behaviours to protect against street violence (restrictive) | Not examined |

| 2018 | Tiderington [54] | Apartment takeovers |

Single-use language in occupancy policies (restrictive) Discouragement of social relationships (restrictive) Surveillance of apartment units and use of drop-ins (surveillant) |

Not examined |

| 2017 | Chang [55] | Drug selling and availability | Widespread presence of security cameras in buildings and surrounding neighbourhood (surveillant) | Not meaningfully examined |

| 2017 | The Dream Team [57] | Apartment takeovers |

Police, security, support worker, or family/friend involvement (relational/educational and legal) Use of screening tools to assess risk for apartment takeovers (clinical) |

Qualitative experiences of residents, which indicated that police involvement was a last resort due to mistrust, concerns about effectiveness, and fears about housing loss |

| 2016 | Kriegel et al. [58] | Neighbourhood crime and drug availability; threatening neighbours |

Courts exert influence on release decisions based on housing models and location (legal, restrictive, and strategic) Selectiveness by service providers as to where to appropriately house residents (strategic) |

Implementation challenges described, such as tension for service providers between court requirements and Housing First principles |

| 2014 | Distasio et al. [60] | Violence; pedophilia; property damage; hoarding; unwanted visitors |

Exclusion policies for applicants with histories of violence and pedophilia (restrictive) Behaviour agreements that outline rules, rights, and consequences (relational/educational) Increased visitation to residents’ homes (surveillant) Eviction notices as a “wakeup call” (strategic) Retention of leaseholder rights by PSH agency, with units sublet to residents, to enable staff to enter units and expel guests (strategic) Peer support focusing on the challenges of visitor management (relational/educational) Transitioning residents to a shelter for respite (strategic) |

Not meaningfully examined |

| 2014 | Silva et al. [61] | Stovetop fires; violence; weapon offences; uninvited guests |

Installation of motion detectors on stoves (design-based) Police involvement and pressing charges (legal) Provision of education and mentorship to residents about who should be allowed to enter apartments (relational/educational) |

Motion detection technology on stoves decreased stovetop fires; outcomes not examined for other two approaches |

| 2012 | Krüsi et al. [63] | Violence; rape |

Women-only buildings (design-based) One-guest maximum policy and registration logs (restrictive and surveillant) Bad-date reports (strategic) Camera surveillance (surveillant) Staff and police involvement (relational/educational and legal) |

Qualitative experiences of residents, with approaches generally being perceived positively and contributing to a sense of safety |

| 2005 | Campanelli et al. [66] | Violence; arson | Screening assessment for applicants with histories of violence and arson (clinical) | Tenancy outcomes of applicants accepted following the screening assessment were presented, but few details on why residents were no longer housed in the program |

| 1996 | Sohng [67] | Sexual and verbal aggression |

Rehospitalization (clinical) Transition to respite care (clinical) |

Not meaningfully examined |

Table 5.

Types of approaches to managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in permanent supportive housing

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Use of existing or augmentations to professional support services for the purpose of assessment and intervention |

Establishment of specialized services, such as hoarding specialists and harm reduction supports Development and implementation of risk-related screening tools |

| Relational/educational | Use of working relationships and informational strategies between PSH staff, often case managers and other direct service providers, landlords, and residents to address high-risk behaviours and challenges |

Advocacy with landlords about damage debts Provision of education and mentorship to residents about who should be allowed to enter apartments |

| Surveillant | Implementation of measures to monitor PSH residents and visitors |

Installation of video cameras in and around PSH buildings Staff drop-ins on residents |

| Restrictive | Use of PSH policies and practices that limit program access, and the behaviours of residents and visitors, as well as choices made by residents to refrain from specific behaviours and locations |

Program policies that exclude applicants with histories of high-risk issues Resident-initiated isolation in housing unit to avoid conflict, access to substances, or another type of threat |

| Strategic | Use of pragmatic strategies to reduce the likelihood of high-risk behaviours and challenges or facilitate their cessation |

Placement of residents in non-first floor housing units to prevent apartment takeovers Transfer of residents in unsafe buildings to new housing |

| Design-based | Built environment and program design decisions and adaptations to reduce the risk of critical events |

Installation of stovetop motion sensors to reduce fire risk Development of women-only PSH programs |

| Legal | Engagement with legal systems in response to high-risk behaviours and challenges |

Pursuit of charges and justice system-based protections following offences Provision of emotional and practical support to report crimes |

| Self-defence | Actions initiated by residents for the purpose of self-protection | Acquiring and carrying weapons in response to safety concerns |

PSH Permanent supportive housing

Resident experiences with high-risk behaviours and challenges

Of the five studies examining how PSH residents responded to high-risk behaviours and challenges, two discussed avoidance of potential threats, including people and drugs [52, 53]. Gender-based violence was the focus of another study, which showed that women who experienced chronic homelessness and engaged in sex work accessed support from program staff and police, a combined relational/educational and legal approach, to address safety concerns [63]. A similar method was also described with apartment takeovers, with residents involving police, security, support workers, or family and friends to resolve the situation [57]. Although the study did not examine the effectiveness of this approach, police involvement was perceived to be a last resort due to mistrust, concerns about effectiveness, and fears about housing loss [57]. Lack of responsiveness by PSH programs to safety threats could also lead residents to consider self-defence strategies. A study of Black PSH residents in Los Angeles found that some carried weapons for self-protection, making this both a type of high-risk behaviour and a response to victimization [42].

Organizational and support approaches

Violence, aggression, and interpersonal threats and abuse were a set of related high-risk behaviours and challenges for which a variety of preventive and reactive approaches were described. Restrictive approaches were commonly used to prevent violence, such as exclusion policies for PSH program applicants with histories of violence and enforcement of visitation program rules to prevent exploitation of residents by guests [52, 60]. There were mixed perceptions among residents of the latter strategy, though women with histories of abuse and sexual victimization viewed that the visitation rules created a sense of safety in their housing [52]. Strategic approaches typically focused on housing location, with service providers being selective about where to appropriately house residents or supporting their transfer to more suitable accommodations [38, 58]. Neither study examined the effectiveness of the strategic approaches. One other study examined a design-based intervention, overdose response buttons in residential units, with findings showing that this technology was used more often for other emergencies, such as violence, than the intended purpose [39]. Approaches could also be combined as part of a multifaceted safety model. For example, to prevent sexual violence in two supportive housing programs for chronically homeless women engaged in sex work, the organizations made use of women-only buildings (design-based); a maximum one-guest policy, registration logs, and security cameras (restrictive and surveillant); and bad-date reports (strategic) [63].

Legal and clinical approaches were also discussed in response to past or ongoing violence. Legal approaches involved case managers supporting residents to obtain restraining orders against threatening individuals, or programs pressing charges or pursuing eviction proceedings in response to violence [38, 60, 61]. The latter approaches highlight how attempts to manage risk may also counter efforts to sustain tenancies. Clinical approaches to addressing violence and aggression included: the use of screening assessments with prospective PSH applicants, the development of safety plans, and transfers of residents to other service settings (e.g., hospital, respite care) [38, 66, 67]. None of these studies measured the effectiveness of the legal or clinical approaches.

Apartment takeovers and trespassing were primarily addressed using relational/educational, strategic, and surveillant approaches. Relational/educational approaches involved PSH staff intervening directly (i.e., engaging and confronting uninvited guests) or indirectly (e.g., supporting residents to strengthen boundary-setting skills, offering peer support focused on visitor management) to problem-solve the issue [43, 45, 60]. Strategic approaches involved not acquiring ground floor housing units where there would be fewer barriers to apartment takeovers, retaining leaseholder rights by the PSH agency to permit direct intervention, and temporarily transitioning residents to shelters for respite as the problem is addressed [43, 60]. Surveillant approaches were used by security, who conducted patrols of PSH buildings to prevent trespassing, as well as by staff who tracked residents’ occupancy violations and dropped in on apartments unexpectedly to enforce visitor policies [42, 54]. Restrictive strategies to prevent apartment takeovers, such as single-use language in occupancy policies and discouragement of social relationships, were also identified in one study [54]. Use of screening tools to assess risk for apartment takeovers was a clinical approach that was proposed in one study but not studied [57]. Only one of the six studies examined outcomes associated with these approaches, with PSH residents perceiving that security patrols were ineffective in deterring trespassers due to inconsistency issues [42].

Five studies examined approaches to preventing and intervening with overdoses. Most of these involved clinical interventions, such as onsite supervised consumption rooms, opioid agonist therapy and safer supply programs, and naloxone training and distribution [36, 41, 46, 47]. Qualitative experiences associated with the approaches were examined in two studies; both of which were generally positive, but limitations with the interventions were also noted [36, 46]. The other two studies did not report outcomes specific to overdose [41, 47]. The fifth study found that overdose response buttons in residential units were used minimally by residents to report imminent drug use [39].

Approaches to preventing fire and arson, as described in three studies, varied. These included design-based strategies, such as fire detection alarms and technology to automatically turn off stoves [48, 61]. The latter approach was reported to reduce stovetop fires in one article, whereas some residents experienced this as disempowering in the other study. Surveillant and restrictive approaches were also used to promote fire safety, which residents experienced as privacy intrusions and potential triggers for paranoia [48]. One other study described a screening tool that assessed PSH applicants for past incidents of arson; the effectiveness of this clinical approach in supporting individuals with fire-setting histories and preventing reoccurrence was not discussed [66].

Suicide risk was the focus of two studies. One found that the MINI Suicidality Subscale was a valid tool for predicting suicide attempts among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness in a Housing First trial [49], whereas the other was a study protocol for a co-intervention involving cognitive therapy for suicide prevention in a Housing First for youth program [40].

Prevention of falls involved clinical (home visit safety assessment), surveillant (increased monitoring of intoxicated residents), and restrictive approaches (removal of alcohol during intoxication) [37, 51]. The structured safety assessment effectively identified environmental fall risks, but no other outcomes were reported for the fall prevention strategies.

Two studies described approaches for managing drug selling and availability risks in PSH buildings and the surrounding neighbourhood. One qualitative study described the widespread presence of security cameras, a surveillant approach [55], whereas another mixed-methods study highlighted how forensic Housing First programs had to navigate competing priorities of the court system that exerted its influence on release decisions based on residents’ substance use histories and the drug presence in communities (legal) [58].

Several approaches to addressing property damage were discussed in two studies, without describing outcomes. These included relational/educational interventions, such as advocacy with landlords related to damage debts, and surveillant approaches (increased visitation to residents’ homes to monitor for damages) [38, 60]. The use of a hoarding specialist was a clinical approach to managing hoarding described in one article [50] and program exclusion policies for PSH applicants with histories of pedophilia was identified in another [60]. Neither study discussed any relevant outcomes.

Discussion

The rapid review findings demonstrate that a range of approaches are used to prevent and manage high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH settings. The approaches were categorized into eight types, which were used in different ways or in combination to address various high-risk behaviours and challenges. Overdose was somewhat of an exception, as it was primarily addressed using clinical interventions. Consistent across all approaches was a lack of rigorous examination of their effectiveness. In studies that presented outcomes, these primarily focused qualitatively on the experiences of PSH staff and residents. Although the qualitative findings highlight key barriers with some approaches, the paucity of outcomes research represents a critical evidence gap that prevents the identification of evidence-based practices for addressing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH programs.

It is important to note that, beyond the PSH literature, there are only a few effective interventions for some high-risk behaviours and challenges, such as arson and fire-setting [68], and apartment takeovers [69]. PSH programs could be well-positioned for pilot interventions related to these high-risk issues, given the vulnerability of residents. In contrast, best practice interventions have been established for other high-risk behaviours and challenges, such as hoarding [70], suicidality [71], and overdose [72]. Although lessons can be drawn from this evidence base, the transferability of the approaches and potential implementation barriers warrant some cautiousness. For example, despite an onsite supervised consumption room being established in a PSH building, most residents continued to use drugs alone in their rooms [36]. Other studies highlighted how safety features in PSH units were misused, disabled, or used for alternative purposes [39, 48]. Thus, there is a need to not only identify effective practices and policies for preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH but also to determine how acceptable these are to residents. Co-designing interventions with PSH residents may be beneficial for maximizing their utility and value.

Effective risk management approaches are a necessity for ensuring safety in PSH. Yet, these approaches require balance with other objectives of PSH programs so as to not become sites of social control [73]. An emphasis on safety and security may also conflict with other priorities. For example, legal approaches that involve initiation of eviction proceedings and police involvement could be used in response to violence and weapon offences [61]. Although PSH programs may take such actions as a final measure, these can threaten the resident’s housing stability. Accordingly, it is important that evictions from PSH use procedurally just processes and that residents be supported to obtain new housing in the absence of prolonged hospitalization or incarceration. These practices are necessary for balancing safety in PSH with a right to housing. Restrictive and surveillant approaches also have the potential to infringe on tenets of some PSH programs, such as individual choice, empowerment, and self-determination, and undermine privacy and mental health recovery [74]. Strategic approaches that involve relocating residents to new buildings in response to high-risk issues may similarly limit agency when such actions are misaligned with the preferences of residents. It is also important to note that PSH residents do not experience these strategies uniformly. For example, women with histories of trauma, abuse, and sex work appreciated the protection yielded from surveillant and restrictive approaches, leading to generally positive perceptions of these practices [52, 63]. This likely reflects the diversity of PSH residents and differences in their support needs based on past experiences, including trauma. Thus, the rapid review findings underscore the importance of engaging PSH residents in the development of risk management approaches, so that they may promote safety without impeding other program objectives and values.

Despite the prevalence of high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH and their potential for serious consequences, only six studies have examined housing-related outcomes. Substance use-linked causes of death, including overdose, were reported as occurring in two studies of Housing First programs. These findings align with recent research that has identified overdose as a serious concern in supportive housing programs [23, 41]. More broadly, substance use problem severity has been identified as a risk factor associated with housing instability in PSH and continued connections to people who use substances may present eviction and apartment takeover risks [15, 75]. The latter findings highlight the complexity of social networks among people who use substances in PSH, as both potential sources of important support and risk [76, 77]. Greater integration of harm reduction services and peer support, as well as more landlord collaboration and education, may be beneficial for reducing preventing eviction risks and substance use-related harms, including overdose, in PSH [78–80]. Beyond substance use, studies in this review mostly produced non-significant results on the associations between high-risk behaviours and challenges, and exits from PSH. Conclusions are premature given the variation in studied issues and the preliminary state of the evidence, though the findings raise the prospect that high-risk behaviours and challenges can be effectively managed in PSH to prevent housing loss. Understanding how this can be done and documenting practice-based knowledge remains a critical need.

Given that there are key evidence gaps with regard to the prevention and management of high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH, it is necessary to identify research priorities that have key implications for future practice and policy. First, few studies examined the outcomes of approaches to preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH and, of the ones that did, most focused on the qualitative perceptions of program staff and residents. Thus, there is a need to investigate effective approaches for preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH and the acceptability of these practices to residents. Second, six studies examined the housing outcomes associated with high-risk behaviours and challenges; however, analyses have mostly been descriptive or limited in scope. This raises the importance of examining if and how high-risk behaviours and challenges mediate the relationship between clinical characteristics and PSH housing outcomes. Third, research on staff training in risk management was notably absent from the review, with the exception of two studies that discussed naloxone training for overdose prevention. Future research is needed to identify the foundational training competencies for risk management in PSH settings. Fourth, screening and assessment tools were described or used for specific types of high-risk behaviours and challenges in four studies. Despite the dearth of research on risk assessment instruments, clinical assessment is a core component of PSH service delivery, which may include an examination of risk-related behaviours [81, 82]. More investigation is warranted into the risk assessment tools currently being used to assess high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH, and the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of these instruments. Fifth, hoarding behaviours are prevalent among people with histories of homelessness, but approaches to addressing hoarding in PSH have been minimally examined, with no interventional studies having been conducted. A key research priority is to determine if evidence-based treatments for hoarding, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, are effective for PSH residents and how feasible it is to deliver these interventions in these settings. Lastly, PSH models and philosophies may shape the types of risk management approaches used by programs. For example, PSH agencies that function as both the landlord and support team, as well as single-site programs, may experience greater tension in balancing the needs of the individual, other residents, and the building, leading to greater risk aversion on the part of the organization. It was not feasible to analyze how program models shaped the types of risk management approaches given the variability in PSH programs and populations presented in the rapid review articles. Because of this, future research is needed to determine how PSH models and philosophies affect the types of approaches used to prevent and manage high-risk behaviours and challenges.

There were several limitations to this rapid review. First, high-risk behaviours and challenges were defined as critical events or serious behaviours that had the potential for deleterious health and housing consequences. This high threshold may have omitted other key issues that threaten housing tenancies or are precursors to potential high-risk behaviours. Second, studies examining adjunct interventions in PSH that have implications for preventing high-risk behaviours and challenges, but which did not measure the specific outcomes of interest to the review, were excluded [83–85]. Nevertheless, these articles may describe additional approaches that could be beneficial for preventing high-risk issues and associated harms. Third, in clustering a range of high-risk behaviours and challenges into a single group, there is an underlying assumption that each of these behaviours and challenges have the potential to cause serious injury, death, or eviction. However, it is likely that some of these behaviours and challenges pose a higher risk of negative outcomes than others. Fourth, website browsing/searching for grey literature was restricted to well-known organizations and networks that offer resources to the supportive housing sector. As a result, relevant documents, especially technical reports of small program evaluations, not listed in these large website registries, may have been missed. Fifth, rapid reviews are not required to include a risk-of-bias assessment [34] and this review did not have one. Thus, some studies included in the review may have produced more methodologically rigorous findings than others. Nevertheless, very little evidence exists on the effects of high-risk behaviours and challenges on housing-related outcomes in PSH, regardless of study quality, making this is a critical area for future research.

Conclusions

High-risk behaviours and challenges are prevalent among people with mental illness and histories of homelessness. This rapid review examined the housing-related outcomes of high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH, and how agencies and residents addressed them. Findings showed that few studies have explored the relationship between high-risk behaviours and challenges, and housing outcomes in PSH, though overdose has been identified as a notable cause of death. As for how PSH programs manage risk, a range of approaches are used, yet their outcomes have also been minimally examined. The lack of evidence on outcomes prevents the identification of evidence-based practices for preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH. Further, some approaches that are legal, restrictive, surveillant, or strategic in nature may be used to promote safety, but conflict with other PSH objectives, including housing stability, or resident empowerment and choice. Accordingly, there is a need to better understand if and how these approaches can be used in a person-centred and mental health recovery-oriented manner. Six research priorities were identified to address the key evidence gaps and move toward best practices for preventing and managing high-risk behaviours and challenges in PSH.

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviation

- PSH

Permanent supportive housing

Author contributions

NK conceptualized the review, in collaboration with SAK and VS. NK developed the review protocol, with input from SAK, JS, BFH, AO, CAM, TA, and VS. NK screened articles for eligibility and led the narrative synthesis, with input and review from CM. NK drafted the manuscript, with feedback on study implications from all other authors. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved of the final version.

Funding

This review was supported by a peer-reviewed grant from Employment Support and Development Canada. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the review; analysis; or manuscript preparation and final approval. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the work.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aubry T, Bloch G, Brcic V, et al. Effectiveness of permanent supportive housing and income assistance interventions for homeless individuals in high-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e342–e360. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng Y, Hahn RA, Finnie RKC, et al. Permanent supportive housing with housing first to reduce homelessness and promote health among homeless populations with disability: a community guide systematic review. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26:404–411. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pottie K, Kendall CE, Aubry T, et al. Clinical guideline for homeless and vulnerably housed people, and people with lived homelessness experience. CMAJ. 2020;192:e240–e254. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubry T, Roebuck M, Loubiere S, et al. A tale of two countries: a comparison of multi-site randomised controlled trials of Pathways housing first conducted in Canada and France. Eur J Homeless. 2021;15:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch-Geertsema V. Housing first Europe – results of a European social experimentation project. Eur J Homeless. 2014;8:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padgett D, Henwood B, Tsemberis S. Housing first: ending homelessness transforming systems, and changing lives. New York: Oxford Press; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stefancic A, Tsemberis S. Housing first for long-term shelter dwellers with psychiatric disabilities in a suburban county: a four-year study of housing access and retention. J Prim Prevent. 2007;28:265–279. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stergiopoulos V, Mejia-Lancheros C, Nisenbaum R, et al. Long-term effects of rent supplements and mental health support services on housing and health outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness: extension study of the at home/Chez Soi randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:P915–P925. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF. Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:487–493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adair CE, Streiner DL, Barnhart R, et al. Outcome trajectories among homeless individuals with mental disorders in a multi-site randomized controlled trial of housing first. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:30–39. doi: 10.1177/0706743716645302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne T, Henwood BF, Scriber B. Residential moves among housing first participants. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2018;45:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lachaud J, Mejia-Lancheros C, Nisenbaum R, et al. Housing first and severe mental disorders: the challenge of exiting homelessness. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci. 2021;693:178–192. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerger S, Pridham KF, Jeyaratnam J, et al. Understanding housing delays and relocations within a housing first model. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43:38–53. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volk JS, Aubry T, Goering P, et al. Tenants with additional needs: when housing first does not solve homelessness. J Ment Health. 2016;25:169–175. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1101416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roebuck M, Agha A, Nelson G, et al. Predictors of housing instability and stability among housing first participants: a 24-month study. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2023 doi: 10.1080/10530789.2023.2174565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerman N, Sylvestre J, Aubry T, et al. The effects of housing stability on service use among homeless adults with mental illness in a randomized controlled trial of housing first. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:190. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sylvestre J, Ollenberg M, Trainor T. A model of housing stability for people with serious mental illness. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2009;28:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirotich F, Rakhra K. Examining the need profile of supportive housing applicants with and without current justice involvement: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2021;44:291–298. doi: 10.1037/prj0000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greig A, Tolin D, Tsai J. Prevalence of boarding behavior among formerly homeless persons living in supported housing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208:822–827. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henwood BF, Rhoades H, Lahey J, et al. Examining fall risk among formerly homeless older adults living in permanent supportive housing. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:842–849. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowe CL, Riley ED, Eagen K, et al. Drug overdose mortality among residents of single room occupancy buildings in San Francisco, California, 2010–2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107571. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerman N, Ecker J, Tiderington E, Aykanian A, Stergiopoulos V, Kidd SA. “Systems trauma”: a qualitative study of work-related distress among service providers to people experiencing homelessness in Canada. SSM-Mental Health. 2022;1(2):100163. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerman N, Goodwin JM, Tiderington E, et al. Towards the quadruple aim in permanent supportive housing: a mixed-methods study of workplace mental health among service providers. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:e6674–e6688. doi: 10.1111/hsc.14033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aubry T, Bernad R, Greenwood RM. “A multi-country study of the fidelity of housing first programmes”: introduction. Eur J Homeless. 2018;12:11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson G, Caplan R, MacLeod T, et al. What happens after the demonstration phase? The sustainability of Canada’s at home/Chez Soi housing first programs for homeless persons with mental illness. Am J Commun Psychol. 2017;59:144–157. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aquin JP, Roos LE, Distasio J, et al. Effect of housing first on suicidal behaviour: a randomised controlled trial of homeless adults with mental disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:473–481. doi: 10.1177/0706743717694836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernad R, Yuncal R, Panadero S. Introducing the housing first model in Spain: first results of the Habitat programme. Eur J Homeless. 2016;10:53–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mejia-Lancheros C, Lachaud J, Stergiopoulos V, et al. Effect of housing first on violence-related traumatic brain injury in adults with experiences of homelessness and mental illness: findings from the at home/Chez Soi randomised trial. Toronto site BMJ Open. 2020;10:e038443. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panadero S, Vázquez JJ. Victimization and discrimination: forgotten variables in evaluating the results of the “housing first” model for persons experiencing homelessness. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2022 doi: 10.1080/10530789.2022.2159617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petering R, La Motte-Kerr W, Rhoades H, et al. Changes in physical assault among adults moving into permanent supportive housing. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP8643–NP8652. doi: 10.1177/0886260519844775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerman N, Polillo A, Bardwell G, et al. Harm reduction outcomes and practices in housing first: a mixed-methods systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:109052. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mejia-Lancheros C, Lachaud J, Gogosis E, et al. Providing housing first services for an underserved population during the early wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0278459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King VJ, Stevens A, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. Paper 2: performing rapid reviews. Syst Rev. 2022;11:151. doi: 10.1186/s13643-022-02011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, et al. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015;4:138. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivsins A, MacKinnon L, Bowles JM, et al. Overdose prevention and housing: a qualitative study examining drug use, overdose risk, and access to safer supply in permanent supportive housing in Vancouver. Can J Urban Health. 2022;99:855–864. doi: 10.1007/s11524-022-00679-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nixon LL, Burns VF. Exploring harm reduction in supportive housing for formerly homeless older adults. Can Geriatr J. 2022;25:285–294. doi: 10.5770/cgj.25.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood L, Vallesi S, Tuson M, et al. Zero project: a housing first response to ending homelessness in Perth. Findings from the 50 Lives 50 homes program. Final evaluation report 2022. 2022. https://assets.csi.edu.au/assets/research/50-Lives-50-Homes-Final-Evaluation-Report.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2023

- 39.Bardwell G, Fleming T, McNeil R, et al. Women’s multiple uses of an overdose prevention technology to mitigate risks and harms within a supportive housing environment: a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21:51. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chavez L, Kelleher K, Bunger A, et al. Housing First Combined with Suicide Treatment Education and Prevention (HOME + STEP): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1128. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corporation for supportive housing. Supportive housing and the opioid crisis. 2021. https://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SUPPORTIVE-HOUSING-AND-THE-OPIOID-CRISIS-update.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2022

- 42.Milburn NG, Edwards E, Obermark D, et al. Inequity in the permanent supportive housing system in Los Angeles: scale, scope and reasons for Black residents’ returns to homelessness. 2021. https://www.capolicylab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Inequity-in-the-PSH-System-in-Los-Angeles.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2022

- 43.Roebuck M, Aubry T, Agha A, et al. A study of the creation of affordable housing for housing first tenants through the purchase of condominiums. Hous Stud. 2021 doi: 10.1080/02673037.2021.1900549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tinland A, Loubiere S, Cantiello M, et al. Mortality in homeless people enrolled in the French housing first randomized controlled trial: a secondary outcome analysis of predictors and causes of death. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1294. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11310-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallesi S, Wood L, Gazey A, et al. 50 Lives 50 Homes: a housing first response to ending homelessness in Perth. Third evaluation report. 2020. https://assets.csi.edu.au/assets/research/50-Lives-50-Homes-Third-Evaluation-Report.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2023

- 46.Bardwell G, Fleming T, Collins AB, et al. Addressing intersecting housing and overdose crises in Vancouver, Canada: opportunities and challenges from a tenant-led overdose response intervention in single room occupancy hotels. J Urban Health. 2019;62:12–20. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0294-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brar R, Sutherland C, Nolan S. Supervised injectable opioid agonist therapy in a supportive housing setting for the treatment of severe opioid use disorder. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e229456. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friesinger JG, Topor A, Bøe TD, et al. The ambiguous influences of fire safety on people with mental health problems in supported housing. Palgrave Commun. 2019;5:22. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz C, Roos LE, Wang Y, et al. Predictive validity of the MINI Suicidality subscale for suicide attempts in a homeless population with mental illness. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;46:1630–1636. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Addictions & mental health Ontario, Canadian mental health association Ontario, Wellesley Institute. Promising practices: 12 case studies in supportive housing for people with mental health and addiction issues. 2018. https://amho.ca/wp-content/uploads/Prom-Prac-Resource-Guide-Final03.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2022

- 51.Gutman SA, Amarantos K, Berg J, et al. Home safety fall and accident risk among prematurely aging, formerly homeless adults. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72:7204195030. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2018.028050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henwood BF, Lahey J, Harris T, et al. Understanding risk environments in permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless adults. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:2011–2019. doi: 10.1177/1049732318785355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhenter P, Moreau D, Laval C, et al. Bread and shoulders: reversing the downward spiral, a qualitative analyses of the effects of a housing first-type program in France. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:520. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15030520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiderington E. “The apartment is for you, it’s not for anyone else”: managing social recovery and risk on the frontlines of single-adult supportive housing. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2018;45:152–162. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang JS. Health in the Tenderloin: a resident-guided study of substance use, treatment, and housing. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cusack M, Montgomery AE. Examining the bidirectional association between veteran homelessness and incarceration within the context of permanent supportive housing. Psychol Serv. 2017;14:250–256. doi: 10.1037/ser0000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The dream team. Safe at home: an exploration of housing unit takeovers (HUTs) in the city of Toronto and recommendations for the future. 2017. https://www.thedreamteam.ca/safe-at-home. Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

- 58.Kriegel LS, Henwood BF, Gilmer TP. Implementation and outcomes of forensic housing first programs. Commun Ment Health J. 2016;52:46–55. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henwood BF, Byrne T, Scriber B. Examining mortality among formerly homeless adults enrolled in housing first: an observational study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1209. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Distasio J, McCullough S, Havens M, et al. Holding on!: supporting successful tenancies for the hard to house. 2014. https://winnspace.uwinnipeg.ca/handle/10680/786. Accessed 15 Nov 2022.

- 61.Silva DS, Bourque J, Goering P, et al. Arriving at the end of a newly forged path: lessons from the safety and adverse events committee of the At Home/Chez Soi project. Ethics & Hum Res. 2014;36:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Collins SE, Malone DK, Clifasefi SL. Housing retention in single-site housing first for chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:S269–S274. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krüsi A, Chettiar J, Ridgway A, et al. Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: a qualitative study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1154–1159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee S, Wong YL, Rothbard AB. Factors associated with departure from supported independent living programs for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Serv. 2009;60(3):367–373. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pearson C, Montgomery AE, Locke G. Housing stability among homeless individuals with serious mental illness participating in housing first programs. J Commun Psychol. 2009;37:404–417. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campanelli PC, Cleek EN, Gold PB, et al. Screening offenders with histories of mental illness and violence for supportive housing. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:279–288. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sohng SSL. Supported housing for the mentally ill elderly: implementation and consumer choice. Commun Ment Health J. 1996;32:135–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02249751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyler N, Gannon TA, Sambrooks K. Arson assessment and treatment: the need for an evidence-based approach. Lancet. 2019;6:808–809. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]