Abstract

Objectives

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a severe complication of leptospirosis. This review focuses on the current evidence of AP in patients with leptospirosis.

Methods

Data on clinical characteristics, biochemical parameters, diagnosis, complications, critical care, fluid management, operative management, and outcomes were analyzed. This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022360802).

Results

We included 35 individual case reports and 4 case series involving 79 patients. Sex was reported for 48 (60.7%) patients; 38 (48.1%) were male and 10 (12.6%) were female. The patients’ mean age was 45.13 (15–83 years). Acute kidney injury, thrombocytopenia, hypotension, and liver injury were the most common complications reported. Complete recovery was reported for 36 (45.5%) patients. Biochemical and radiological recovery was reported for 10 (12.6%) and 9 (11.3%) patients, respectively. Death was reported in 18 (22.7%) patients.

Conclusion

A high degree of clinical suspicion and different modalities of investigations are essential in the diagnosis of AP in leptospirosis. AP can be easily missed in leptospirosis because both conditions share similar clinical presentations and complications. Because of the high prevalence of acute kidney injury, judicious fluid management and close monitoring are mandatory.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, leptospirosis, hyperamylasemia, peripancreatic necrosis, multiorgan failure, acute kidney injury

Introduction

Leptospirosis is a common zoonotic illness caused by Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae and other subspecies. 1 It has a significant impact on health expenditures in developing countries. 2 Leptospirosis has a wide spectrum of presentations ranging from asymptomatic self-limiting illness to fatal multiorgan involvement. 3 The incubation period of leptospirosis is approximately 1 to 2 weeks. 4 The bacterium is present in water contaminated by excreta of chronically infected rodents, and it enters the human body through mucous membrane and skin aberrations. 5 People at risk include farmers and slum dwellers. 6 Complications are mainly caused by vasculitis involving medium and small vessels. 1 Widespread activation and damage of endothelial cells in these vessels occurs by either direct injury by the microorganism or immune-mediated destruction following cytokine storm. 7 Leptospirosis often occurs in tropical and subtropical countries because the climate favors the transmission. 7 Because most tropical regions contain developing countries, leptospirosis continues to have a negative impact on the healthcare systems in these countries with each outbreak that occurs. 4

The mild form of leptospirosis has two distinctive phases: the septicemic and immune phases. 8 The acute septicemic phase lasts for 5 to 7 days and is followed by transient symptomatic improvement. 7 The disease then either progresses to the severe form or regresses to an asymptomatic illness. 7 The severity of leptospirosis is not predictable at symptom onset 7 ; it is influenced by host-related factors and the pathogenicity of the microorganism. 7 Weil syndrome is a severe form leptospirosis manifesting as renal failure, hepatic dysfunction, pulmonary hemorrhage, and multiple hemorrhagic diathesis.9–12

The mortality rate is higher in patients with Weil syndrome, reaching 10% to 15%, 12 and exceeds 50% when severe pulmonary hemorrhagic syndrome occurs.5,13 Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an uncommon but known complication of leptospirosis. 12 However, very few studies have focused on the incidence, pathogenesis, and risk factors of AP in leptospirosis. AP has a wide spectrum of presentations ranging from mild symptomatic illness to severe hemorrhagic pancreatitis causing peripancreatic necrotic collections (PPNC) and fatal multiorgan failure (MOF). 6

Diagnosis of AP in patients with leptospirosis is important because both AP and leptospirosis can lead to MOF, and early diagnosis with prompt management may reduce the risk of mortality. 14 The diagnosis of AP is reached after correlating the biochemical and radiological findings with the clinical presentation (CP). 10 Serological testing of leptospirosis is also important to confirm the etiology of AP. 15 The modified Atlanta criteria are used to diagnose AP, and two of the following three criteria must be fulfilled 16 : clinical features including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting; biochemical features including a serum lipase or amylase concentration higher than three times the upper limit of normal; and characteristic imaging findings on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging. 16

The severity of AP is classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on local and systemic complications. 17 Various scoring systems are available to classify the severity of AP. 16 The revised Atlanta classification is one such system that is widely accepted for defining the severity of AP. 16 Persistent organ failure is the hallmark of severe AP and is associated with an increased mortality rate (20%) and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). 18

It should be noted that clinical manifestations are not reliable because both AP and leptospirosis have common symptoms and signs. 19 Early identification and treatment, including both operative and nonoperative measures, are important to minimize complications. 20 A synopsis of existing evidence on leptospirosis complicated by AP is needed. The primary objective of this review was to systematically examine the clinical characteristics, biochemistry, imaging, complications, management, and outcomes of AP in the setting of leptospirosis.

Methods

Search strategy

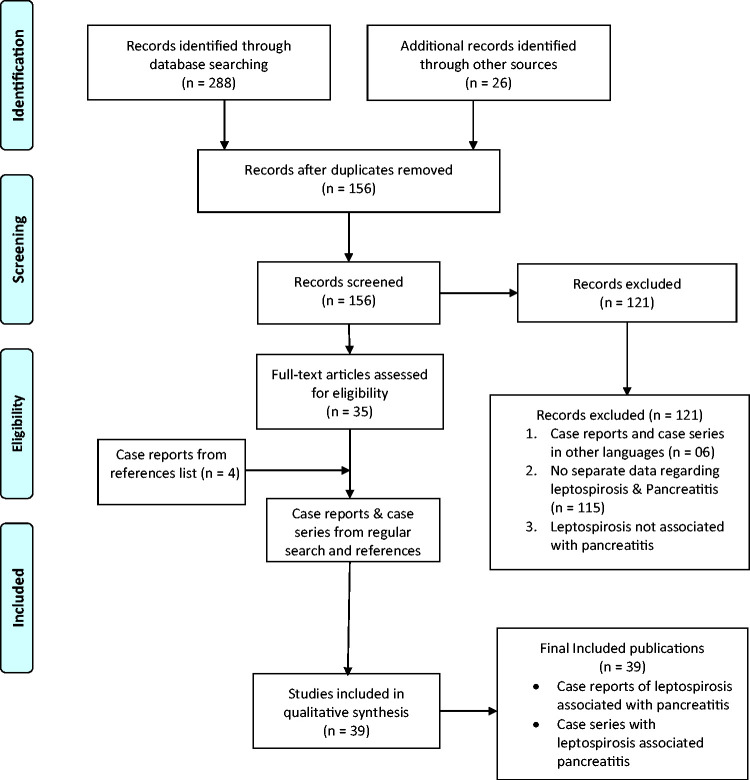

We systematically searched the electronic databases of PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) from database inception to December 2021 with no language restriction. Key words related to AP and its complications as well as leptospirosis were searched in the title and abstract fields. The detailed search strategy is shown in the supplementary file. Additionally, the reference list of each eligible article was manually searched to identify more publications (Figure 1). This study was registered in PROSPERO (Number: CRD42022360802).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Eligibility criteria and screening of articles

All types of observational studies (e.g., cohort studies, case-control studies, descriptive cross-sectional studies, case reports, and series) were included in the review. Articles were screened using three key criteria:

The article must describe AP as a complication of leptospirosis.

The article must be based on primary data of actual patients.

The article must include an interim or full analysis and not be restricted to a description of a protocol.

In the first round, two investigators independently performed the initial screening based on the titles and abstracts. In the second round, the full texts of relevant records were assessed based on the eligibility criteria. In doubtful situations, a consensus was reached after discussion with a third investigator.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently performed the data extraction using a predesigned template. All data pertaining to the CP, investigations, treatment, and outcomes were extracted, categorized, and tabulated. The extracted data were cross checked for any discrepancy by a third reviewer.

Data analysis

The risk-of-bias assessment of eligible studies was performed using the Downs and Black checklist, and the findings are shown in Table S1. A narrative synthesis was performed with the available data. A meta-analysis of the quantitative parameters (e.g., outcome) was not performed because of the heterogeneity in the reporting and the limited number of studies.

Data analysis

Ethics approval and consent to participate are not applicable because of the nature of this study (systematic review with no patient involvement).

Results

Clinical characteristics

The screening process resulted in the inclusion of 35 individual case reports and 4 case series involving a total of 79 patients. Sex was reported for 48 (60.7%) patients and was not available for 31 (39.2%) patients. Of the 48 patients with available data on sex, 38 (48.1%) were male and 10 (12.6%) were female. The patients’ mean age was 45.13 (range, 15–83) years.

Abdominal pain (n = 51, 64.5%), fever (n = 45, 56.9%), vomiting (n = 30, 37.9%), and oliguria (n = 11, 13.9%) were the most common symptoms. Other manifestations included bleeding (n = 12, 15.1%), arthralgia (n = 8, 10.1%), lethargy (n = 8, 10.1%), diarrhea (n = 6, 7.5%), and chills and rigors (n = 5, 6.3%). Headache (n = 4, 5.0%), dyspnea (n = 3, 3.7%), occipital headache (n = 2, 2.5%), cough (n = 2, 2.5%), and back pain (n = 2, 2.5%) were also reported as common symptoms. Icterus (n = 34, 43.0%), tachycardia (n = 19, 24.0%), and hypotension (n = 17, 21.5%) were the most common examination findings described. Other clinical signs were abdominal tenderness (n = 15, 18.9%), conjunctival suffusion (n = 13, 16.4%), tachypnea (n = 10, 12.6%), and basal crepitation (n = 9, 11.3%) (Table 1). 3 ,6,8,11–15,17,19,21–47

Table 1.

General and clinical characteristics of patients with leptospirosis and acute pancreatitis.

| SN | Authors (year) | Sex | Age (y) | Strain | Method of diagnosis | Clinical presentation | Physical examination findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maier et al. 21 (2019) | M | 73 | Leptospira interrogans | Lipase, CP | Sore throat, mucosal congestion, high-grade fever, jaundice, back pain, leg weakness | Jaundice, minor petechiae in lower legs, distended abdomen, right hypochondrial tenderness |

| 2 | Jain and Mohan 6 (2013) | M | 45 | NA | CT, amylase, lipase | Abdominal pain, progressive abdominal distention | Tachypnea, tachycardia, fever, frank signs of peritonitis in abdominal examination |

| 3 | Silva et al. 22 (2011) | M | 48 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Progressive weakness of limbs, severe leg pain, high-grade fever, occipital headache, diarrhea, weight loss | Ill-looking, dehydrated, PR of 108/min, BP of 140/80 mmHg, paraparesis, muscle tenderness, absent patella and ankle reflexes |

| 4 | Spichler et al. 20 2007 | M | 18 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Fever, myalgia, diffuse abdominal pain, progressive dyspnea | Ill-looking, BP of 100/60 mmHg, PR of 112/min, RR of 48/min, SpO2 of 80% |

| 5 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | F | 68 | Leptospira biflexa serovar Patoc | Lipase, amylase | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice | Ill-looking, dehydrated, icteric, PR of 120/min, tachypnea, abdominal tenderness, guarding and rebound tenderness |

| 6 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | M | 62 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | CT, amylase, lipase | Fever, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, malaise, dizziness | Icterus, conjunctival hyperemia |

| 7 | Prasanthie and De Silva 15 (2009) | M | 28 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | Lipase, amylase | Fever, myalgia, vomiting for 3 days | Icterus, conjunctival suffusion, diffuse abdominal tenderness |

| 8 | Afzal et al. 25 (2020) | M | 61 | NA | Lipase, CP | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain for 1 week | Icterus, conjunctival suffusion, hypertension, supple neck, heaving laterally displaced point of maximum impulse, regular heart rate and rhythm |

| 9 | Mazhar et al. 26 (2016) | M | 23 | Leptospira interrogans | Lipase, CP | Fever, chills, headache, neck stiffness, productive cough, nausea, diffuse myalgia, photophobia, non-bloody watery stools, non-bloody non-bilious vomiting, bloodstained sputum, dark-colored urine for 2 days | Hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnea, SpO2 of 94%, conjunctival injection, icterus, reduced bilateral air entry in lung examination, abdominal rigidity, tenderness, hyperactive bowel sounds, hip/knee/ankle tenderness |

| 10 | Ranawaka et al. 13 (2013) | M | 15 | Leptospira interrogans | CT, CP | High-grade intermittent fever with epigastric discomfort and backache without severe myalgia for 5 days | Hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, ill-looking |

| 11 | Yew et al. 27 (2015) | M | 53 | NA | Amylase, CP | Fever, headache, lethargy, myalgia, arthralgia, epigastric pain, nausea for 4 days | Normal examination |

| 12 | Gomes et al. 54 (2019) | M | 48 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Diffuse abdominal pain, vomiting, myalgia, calf pain, fever, conjunctival hyperemia, progressive jaundice, dark urine for 10 days | Diminished turgor, pallor, jaundice, enlarged abdomen with tenderness on superficial and deep palpation, BP of 100/60 mmHg, PR of 160/min, RR of 17/min, SpO2 of 97% |

| 13 | Panagopoulis et al. 29 (2014) | M | 32 | Leptospira interrogans | Amylase | Fever, headache, confusion, rigor, for 1 week | Fever, headache, confusion, rigor, tachycardia |

| 14 | Popa et al. 30 (2013) | M | 34 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | CT, CP | Transferred from another hospital for further management of pancreatitis and sepsis, initial presentation not clearly mentioned | Abdominal distension, icterus, epigastric mass, painful induration in left iliac fossa and left flank, epigastric guarding, epigastric dullness |

| 15 | Lim et al. 31 (2014) | M | 83 | NA | CT, CP | Fever, abdominal pain, vomiting for 2 days | Ill-looking, normal BP, mild epigastric tenderness, bilateral basal crepitations in lung examination |

| 16 | Mondal et al. 32 (2014) | M | 32 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | CT, amylase, CP | Moderate-grade intermittent fever, mild cough, redness of eyes, pain in muscles (especially in calf region) for 10 days | Icterus, confusion, GCS score of 11/15, severe pallor, neck rigidity, positive Kernig sign, hepatomegaly, sluggish peristalsis |

| 17 | Desai and Hattangadi 14 (2008) | M | 45 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | CT, CP | Epigastric pain with back radiation, bilious vomiting, mild fever, steatorrhea, hematuria, reduced urinary output | Tachycardia, tachypnea, mild hypotension |

| 18 | Schattner et al. 19 (2020) | M | 63 | Leptospira interrogans serovar Bratislava | CT, amylase, lipase | Extreme lassitude and fatigue | Normal examination |

| 19 | Law et al. 33 (2014) | M | 34 | NA | CT, amylase, lipase | Fever, nonproductive cough, progressive breathlessness for 10 days | Fever, tachypnea, coarse crepitations in lung examination |

| 20 | Castillo et al. 34 (2006) | M | 32 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Fever, nonproductive cough, progressive breathlessness for 10 days | Jaundice |

| 21 | Taher et al. 35 (2005) | F | 36 | Leptospira interrogans serovar Bataviae | Lipase, amylase | Severe abdominal pain and generalized malaise for 1 week | Moderately ill, alert and oriented, pale icterus, BP of 120/80 mmHg, PR of 100/min, RR of 20/min, hepatosplenomegaly |

| 22 | Krati et al. 36 (2019) | M | 18 | NA | CT, CP | Fluctuating fever, icterus, epigastric pain, muscle pain, diarrhea, liquid yellowish stool | Fever, tachycardia, discrete hepatomegaly |

| 23 | Tanrıverdi 42 (2009) | F | 67 | NA | NA | Flulike presentation, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, functional impotence, occipital headache, diplopia, unusual neck pain, abdominal pain, fever, nausea, bilious vomiting | Ill-looking, PR of 110/min, BP of 145/85 mmHg, tachypnea |

| 24 | Baburaj et al. 37 (2008) | M | 63 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, malaise, pain, and weakness for 2 days | Ill-looking, fever, jaundice, bilateral conjunctival congestion, pedal edema, tachycardia, abdominal distention, diffuse tenderness, guarding, hepatomegaly, reduced bowel sounds, free fluid in abdomen, left lung crepitation |

| 25 | Pribadi et al. 12 (2012) | M | 42 | NA | Lipase, amylase | Fever, diarrhea, body aches for 3 days | GCS of 13, icterus, ciliary injection, greenish fluid in nasogastric tube, generalized abdominal tenderness, bilateral calf tenderness |

| 26 | Khan et al. 38 (2015) | M | 35 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | CT, CP | Fever, reduced appetite, diffuse abdominal and calf pain for 1 week | Conscious, oriented, febrile, normal BP, PR of 100/min, low-volume regular pulse, RR of 18/min |

| 27 | Thungag et al. 3 (2008) | F | 45 | NA | Amylase, CP | High-grade fever with chills and rigors for 3 days | Normal examination |

| 28 | Bourquin et al. 8 (2011) | M | 65 | Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae | NA | High-grade fever with chills and rigors, sweating, chest pain of pricking nature for 3 days | Fever, icterus |

| 29 | Sharma et al. 39 (2019) | M | 60 | NA | CT, amylase, lipase | Fever, epigastric pain, myalgia, jaundice for 1 week | Ill-looking, icterus, bilateral conjunctival congestion, pedal edema, tachycardia, BP of 90/60 mmHg, abdominal distension, diffuse tenderness, guarding, rigidity, reduced bowel sounds |

| 30 | Pal 11 (2019) | M | 57 | NA | CT, amylase, CP | Fever, body aches, and diarrhea for 3 days | Hypotension, tachycardia, scleral icterus, subconjunctival hemorrhage, rebound tenderness, guarding, sluggish peristaltic sounds |

| 31 | Casella and Scatena 43 (2000) | M | 42 | Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona | Lipase, amylase | High-grade continuous fever, jaundice, myalgia, redness of right eye, cough, hemoptysis, reduced urine output, diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness | Poor general condition, severe dehydration and hypotension, hepatosplenomegaly |

| 32 | Maria-Rios et al. 40 (2020) | M | 43 | NA | CT, lipase, CP | Fever, diarrhea, sore throat, headache | Diffuse icterus, mild epigastric tenderness |

| 33 | Simon et al. 41 (2012) | M | 37 | Leptospira interrogans | Lipase, CP | Intermittent fever, myalgia, and general weakness | Generalized rash with desquamation and purpura |

| 34 | Monno and Mizushima 44 (1993) | M | 66 | Leptospira interrogans serovar Autumnalis | Amylase, lipase, CP | Fever, chills, myalgia, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, retro-orbital pain | Jaundice, conjunctival suffusion, erythema, right hypochondrial tenderness, calf tenderness, mild lymphadenopathy |

| 35 | Chong and Goh 45 (2007) | M | 41 | NA | Amylase, CT | Fever, myalgia, anorexia, and fatigue | Jaundice, lethargy, nonspecific abdominal tenderness |

| 36 | Herath et al. 46 (2016) | NA | 43 | NA | NA | Fever, myalgia, and arthralgia in all six patients; nausea, vomiting, and radiation to back in four patients | Hypotension and bilateral basal crepitation in lung examination in six patients; epigastric tenderness, guarding, conjunctival suffusion, and tachycardia in four patients; tachypnea, hepatomegaly, and icterus in three patients; pallor and bleeding in one patient |

| 37 | O’Brien et al. 47 (1999) | 7M, 6F | MA 42 | Leptospira interrogans serovar Bratislava in three patients, serovar Autumnalis in two patients | Lipase, amylase, CP | NA | NA |

| 38 | Kishor et al. 10 (2002) | NA | NA | NA | Amylase, abdominal USS | Fever, epigastric pain, and vomiting in 15 patients | NA |

| 39 | Daher et al. 17 (2003) | NA | 16 | NA | Histology (autopsy) | Fever in12 patients; vomiting, myalgia, and dyspnea in 11 patients; chills in 10 patients; abdominal pain and diarrhea in 8 patients; oliguria in 1 patient | Jaundice in 12 patients, tachycardia and dehydration in 8 patients, hypotension in 7 patients |

SN, serial number; M, male; F, female; NA, not available; MA, mean age; CP, clinical presentation; BP, blood pressure; PR, pulse rate; RR, respiratory rate; CT, computed tomography; USS, ultrasound scan; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Biochemical and electrocardiographic findings

Among all 79 patients, hyperamylasemia (n = 56, 70.8%), leukocytosis (n = 38, 48.1%), and thrombocytopenia (n = 31, 39.2%) were the most common findings. Other common findings were hyperbilirubinemia (n = 20, 25.3%), altered liver enzymes (n = 23, 29.1%), hyperlipasemia (n = 20, 25.3%), and anemia (n = 10, 12.6%). Metabolic acidosis (n = 9, 11.3%), hypocalcemia (n = 9, 11.3%), microscopic hematuria (n = 6, 7.5%), an increased alkaline phosphatase concentration (n = 8, 10.1%), and proteinuria (n = 6, 7.5%) were the remaining findings. Electrocardiographic findings were available for seven (8.8%) patients. The most common electrocardiographic findings noted were atrial fibrillation (n = 3, 3.7%), bradycardia (n = 3, 3.7%), and atrioventricular block (n = 1, 1.2%) (Table 2). 3 ,6,8,11–15,17,19,21–47

Table 2.

Biochemical findings of patients with leptospirosis and acute pancreatitis

| SN | Authors (year) | WBC(/µL) | Hb(g/dL) | PCV | Platelets(/µL) | Na(mol/L) | K(mmol/L) | Amylase(U/L) | Lipase(U/L) | CRP(mg/L) | AST(U/L) | ALT(U/L) | TBr(µmol/L) | SCr(mg/dL) | Ca(mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maier et al. 21 (2019) | 13,200 | 14 | 42% | NA | NA | NA | 69 | 2417 | 174 | 36 | 55 | 15 | 2.95 | NA |

| 2 | Jain and Mohan 6 (2013) | 4500 | 11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5300 | 1200 | NA | 22 | 85 | 1.9 | Normal | NA |

| 3 | Silva et al. 22 (2011) | 6770 | 12.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 478 | 898 | NA | 130 | 213 | 11.05 | 1.3 | NA |

| 4 | Spichler et al. 20 (2007) | 54,800 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2860 | 14,900 | NA | 223 | 158 | 3.4 | 5 | NA |

| 5 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | 9000 | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 630 | 642 | 192 | 1900 | 2500 | 6.5 | 2.7 | NA |

| 6 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | 23,000 | 8.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 830 | 797 | NA | 85 | 70 | 48 | NA | NA |

| 7 | Prasanthie and de Silva 15 (2008) | 13,000 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1834 | 198 | NA | 106 | 60 | NA | NA | ||

| 8 | Afzal et al. 25 (2020) | 10,100 | 13 | 39% | 12,800 | 141 | 40 | NA | NA | NA | 0.3 | 4.9 | NA | 1.4 | NA |

| 9 | Mazhar et al. 26 (2016) | 18,000 | 42 | NA | NA | 132 | 3 | NA | 1750 | NA | 144 | 184 | 13 | 4.4 | NA |

| 10 | Ranawaka et al. 13 (2013) | 7000 | 13 | NA | 12,500 | NA | NA | 4200 | NA | NA | 96 | 141 | NA | 521 | Low |

| 11 | Yew et al. 13 (2015) | NA | 12.7 | NA | 32,000 | NA | NA | 2707 | NA | NA | 59 | NA | NA | 233 | NA |

| 12 | Gomes et al. 54 (2019) | 20,000 | 12.8 | 36.9% | 32,000 | 142 | 4.5 | 664 | 4277 | NA | 96 | 81 | 18.48 | 2.73 | NA |

| 13 | Panagopoulis et al. 29 (2014) | 15,000 | NA | NA | 5000 | NA | NA | 1000 | NA | NA | 5 times | NA | NA | 3 | NA |

| 14 | Popa et al. 30 (2013) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 15 | Lim et al. 31 (2014) | 11,700 | 12.4 | NA | 169,000 | NA | NA | 820 | NA | NA | 49 | 66 | 0.91 | 1.57 | 8.6 |

| 16 | Mondal et al. 32 (2014) | 15,600 | 9.4 | NA | Normal | NA | NA | 750 | 3720 | NA | 168 | 71 | 11.7 | 4.1 | NA |

| 17 | Desai and Hattangadi 14 (2008) | 16,500 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.6 | 1.7 | NA |

| 18 | Schattner et al. 19 (2020) | 23,300 | 12.06 | NA | 201,000 | NA | 3.3 | 428 | 373 | 43.4 | Normal | Normal | 31.1 | Normal | 7 |

| 19 | Law et al. 33 (2014) | Increased | Normal | NA | Normal | NA | NA | 156 | 111 | NA | Mildly elevated | Mildly elevated | NA | Normal | NA |

| 20 | Castillo et al. 34 (2006) | 15,000 | 15 | NA | 316,000 | 139 | 3.3 | 1275 | 2800 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.9 | 9.5 |

| 21 | Taher et al. 35 (2005) | 12,600 | 8.4 | NA | NA | 127 | 3 | 327 | 445 | NA | 73 | 94 | NA | 7.4 | NA |

| 22 | Krati et al. 36 (2019) | 13,850 | NA | NA | 3900 | 3.8 | NA | >550 | NA | 142.5 | 1044 | 1740 | NA | 13 | NA |

| 23 | Tanriverdi 42 (2009) | 3400 | 11.8 | 34.5% | 79,000 | 122 | 3.1 | 32.4 | NA | 211.4 | 41.8 | 32.4 | 0.9 | 5.42 | 8.9 |

| 24 | Tanriverdi 42 (2009) | 12,500 | NA | Normal | 45,000 | NA | NA | 1176 | 412 | NA | 921 | 52 | 5.9 | 2 | NA |

| 25 | Pribadi et al. 12 (2012) | 13,000 | 12.3 | 33.5% | 233,000 | NA | 6.4 | 224 | 314 | NA | 50 | 60 | 18.78 | 6.6 | NA |

| 26 | Khan et al. 38 (2015) | 14,600 | 10.8 | NA | 78,000 | NA | 140 | 4.6 | NA | NA | 46 | 50 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 8.2 |

| 27 | Thungag et al. 3 (2008) | 15,000 | NA | NA | 22,000 | NA | NA | 1429 | 60 | NA | NA | NA | 9.8 | 3.1 | NA |

| 28 | Bourquin et al. 8 (2011) | NA | 11.5 | NA | 22,000 | NA | 2.7 | NA | NA | 209 | 185 | 108 | 285 | 486 | NA |

| 29 | Sharma et al. 39 (2019) | 12,500 | NA | NA | 40,000 | NA | NA | 1106 | 412 | NA | 92 | 52 | NA | 2.4 | NA |

| 30 | Pal 11 (2019) | 15,900 | 11.8 | NA | 20,000 | 110 | 3.1 | 984 | 1012 | NA | 82 | 27 | 22 | 5.1 | NA |

| 31 | Casella and Scatena 43 (2000) | 11,800 | NA | 122 | NA | NA | 1116 | 802 | NA | NA | NA | 4.77 | 4.77 | NA | |

| 32 | Maria-Rios et al. 40 (2020) | NA | NA | NA | 9000 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 564 | 462 | 12 | NA | NA |

| 33 | Simon et al. 41 (2012) | 12,500 | 12.6 | 34.3% | 42,000 | NA | NA | NA | 402 | 231 | 90 | 70 | 42.6 | 1.1 | NA |

| 34 | Monno and Mizushima 44 (1993) | 8800 | 13.9 | 40.4% | 131 | 4.1 | 344 | 1400 | 5 | 243 | 106 | 6.5 | NA | NA | |

| 35 | Chong and Goh 45 (2007) | 17,000 | NA | NA | 105,000 | NA | NA | 328 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17.1 | 1.4 | NA |

| 36 | Herath et al. 46 (2016) | Leukocytosis in 8 patients | NA | Thrombocytopenia in 6 patients | NA | NA | NA | Hyperamylasemia in 6 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | Hyperbilirubinemia in 5 patients | Increased creatinine in 6 patients | Hypocalcemia in 4 patients |

| 37 | O’Brien et al. 47 (1999) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Hyperamylasemia in 8 patients | Hyperlipasemia in 8 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | Increased creatinine in 10 patients | NA |

| 38 | Kishor et al. 10 (2002) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Hyperamylasemia in 15 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 39 | Daher et al. 17 (2003) | Leukocytosis in 8 patients | NA | Thrombocytopenia in 10 patients | NA | NA | Hyperkalemia in 6 patients | Hyperamylasemia in 3 patients | Hyperlipasemia in 5 patients | NA | Elevated transaminases in 4 patients | Elevated transaminases in 4 patients | Hyperbilirubinemia in 9 patient | Increased creatinine in 12 patients | NA |

SN, serial number; WBC, white blood cell count; PCV, packed cell volume; NA, not available; Hb, hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; TBr, total bilirubin; SCr, serum creatinine.

Radiological findings

At least one modality of imaging was reported for 48 (60.7%) patients. An abdominal ultrasound scan (USS), abdominal contrast-enhanced CT (CECT), chest X-ray (CXR), and abdominal X-ray (AXR) were used as imaging modalities. USS was performed in 41 (51.8%) patients. Abnormalities consistent with pancreatitis (n = 19, 24.0%) and ascites (n = 4, 5.0%) were the most common findings. CECT findings were reported for 21 (26.5%) patients.

The most common findings in CECT were a large bulky pancreas (n = 5, 6.3%), peripancreatic fat stranding (n = 5, 6.3%), an edematous pancreatitis (n = 5, 6.3%), hepatosplenomegaly (n = 4, 5.0%), and PPNC (n = 4, 5.0%). The remaining findings were ascites (n = 3, 3.7%), bilateral pleural effusion (n = 2, 2.5%), and isolated hepatomegaly (n = 1, 1.2%). CXR was performed examine the concomitant lung involvement in six (7.5%) patients, and diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage (n = 1, 1.2%) was the most common finding. AXR was performed in five (6.3%) patients, and the presence of dilated intestinal loops (n = 2, 2.5%) was the most common finding (Table 3). 3 ,6,8,11–15,17,19,21–47

Table 3.

Microbiological and radiological investigations of patients with leptospirosis and acute pancreatitis

| SN | Authors (year) | Lepto IgM | DFM | Blood PCR | MAT | Urine PCR | Lepto IgG | CXR findings | AXR findings | USS findings | CECT findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maier et al. 21 (2019) | Present | Absent | NA | NA | NA | Present | Normal | NA | Prominent edematous pancreas | NA |

| 2 | Jain and Mohan 6 (2013) | Present | Absent | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal | NA | Moderate ascites, pancreas not visualized | Bulky pancreas with areas of necrosis and peripancreatic fluid collections |

| 3 | Silva et al. 22 (2011) | Present | Absent | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Free peritoneal fluid | Free fluid in the pelvis and bilateral pleural effusion |

| 4 | Spichler et al. 20 (2007) | Present | Absent | NA | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | Mild hepatomegaly | Normal no pancreatic abnormalities |

| 5 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | NA | Absent | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | Acute calculous cholecystitis and abdominal fluid collection | NA |

| 6 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | NA | Present | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Bilateral pleural effusion, intra-abdominal minimal fluid collection/peripancreatic tissue heterogeneity |

| 7 | Prasanthie and de Silva 15 (2008) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 | Afzal et al. 25 (2020) | NA | NA | Positive | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Isolated hepatofugal flow in right portal vein suspicious for portal vein thrombosis; normal directional flow in left portal vein | Normal except for subtle sludge and gallstones in GB |

| 9 | Mazhar et al. 26 (2016) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Bilateral diffuse alveolar shadows suggesting diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage | NA | Hepatomegaly without ascites or biliary dilation | Presence of hepatosplenomegaly without biliary dilation and unremarkable pancreas |

| 10 | Ranawaka et al. 13 (2013) | Present | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Prominent edematous pancreas suggesting pancreatitis; hepatomegaly also present |

| 11 | Yew et al. 27 (2015) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | Gomes et al. 54 (2019) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 13 | Panagopoulis et al. 29 (2014) | Present | NA | Positive | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 14 | Popa et al. 30 (2013) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Air–fluid levels in small bowel in center of abdomen | Hepatic steatosis, peritoneal ascites in Morrison’s pouch, homogeneous pancreas with cephalic diameter of 20 mm | Diffuse enlargement of the pancreas with necrosis associated with necrotic collections in the lesser sac, anterior and inferior to the pancreatic tail; necrotic retroperitoneal extensions, anterior to the left prerenal fascia and behind the descending colon |

| 15 | Lim et al. 31 (2014) | Present | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Patchy area of non-enhancement at the pancreatic head region, representing an area of necrosis and streaky peripancreatic fat; ill-defined fluid collection present inferior, posterior, and anterior to the pancreatic head and neck; pericholecystic fluid with enhancement of GB wall |

| 16 | Mondal et al. 32 (2014) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Bulky pancreas with mild peripancreatic fat stranding |

| 17 | Desai and Hattangadi 14 (2008) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Ground glass appearance | Pancreatitis features | Free fluid in the abdomen, edematous pancreas, peripancreatic fat stranding |

| 18 | Schattner et al. 19 (2020) | NA | NA | Positive | NA | NA | NA | Normal | NA | NA | Non-enlarged and homogeneously enhancing liver and spleen, mild fat stranding in the lesser omentum, acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis without tissue necrosis |

| 19 | Law et al. 33 (2014) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Bulky pancreas with peripancreatic fat stranding |

| 20 | Castillo et al. 34 (2006) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 21 | Taher et al. 35 (2005) | Present | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | Normal | NA | Mild hepatomegaly of left lobe with chronic parenchymal liver disease and renal disease | Computed tomography not performed |

| 22 | Krati et al. 36 (2019) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | Increased pancreatic volume without an identifiable obstruction | Homogeneous increase in pancreatic volume without identifiable lithiasis but with homogeneous hepatosplenomegaly |

| 23 | Tanriverdi 42 (2009) | Present | Present | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | Thickened GB with pericholecystic fluid collection | CECT normal |

| 24 | Baburaj et al. 37 (2008) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dilated intestinal loops | Mild hepatomegaly with consolidation of left lower lobe of lung and bilateral minimal pleural effusion | Bulky edematous pancreas with mild hepatosplenomegaly |

| 25 | Pribadi et al. 12 (2012) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | CKD, CLCD, bile sludge, bilateral hydronephrosis | NA |

| 26 | Khan et al. 38 (2015) | Present | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | Normal | Normal | Bulky pancreas | Peripancreatic necrosis with diffuse pancreatitis |

| 27 | Thungag et al. 3 (2008) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal | NA |

| 28 | Bourquin et al. 8 (2011) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 29 | Sharma et al. 39 (2019) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dilated intestinal loops | Mild hepatomegaly with consolidation of left lower lobe of lung and bilateral minimal pleural effusion | Bulky edematous pancreas with mild hepatosplenomegaly |

| 30 | Pal 11 (2019) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Evidence of AP |

| 31 | Casella and Scatena 43 (2000) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Splenomegaly | NA |

| 32 | Maria-Rios et al. 40 (2020) | NA | NA | Present | NA | Present | NA | Features of ARDS | NA | Normal | Peripancreatic fat stranding |

| 33 | Simon et al. 41 (2012) | Present | NA | NA | Present | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 34 | Monno and Mizushima 44 (1993) | NA | NA | NA | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | Enlarged tender GB with sludge | NA |

| 35 | Chong and Goh 45 (2007) | Present | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal | NA | Thickened GB with pericholecystic fluid collection | Mild AP |

| 36 | Herath et al. 46 (2016) | NA | NA | NA | Present in 6 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 37 | O’Brien et al. 47 (1999) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Present in 5 patient and normal pancreas in all 5 patients | NA |

| 38 | Kishor et al. 10 (2002) | Present in 15 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Pancreatitis in 15 patients | NA |

| 39 | Daher et al. 17 (2003) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Lepto IgM, Leptospira immunoglobulin M; Lepto IgG, Leptospira immunoglobulin G; SN, serial number; AP, acute pancreatitis; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLCD, chronic liver cell disease; DFM, dark field microscopy; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MAT, microscopic agglutination test; CXR, chest X-ray; AXR, abdominal X-ray; USS, ultrasound scan; GB, gallbladder; NA, not available; CECT, contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Diagnosis of AP and leptospirosis

The serum concentration of either amylase or lipase was reported for 43 (54.4%) patients. Only the enzyme concentrations and CP were reported for 18 (22.7%) patients. Amylase with CP (n = 3, 3.7%), lipase with CP (n = 4, 5.0%), and both amylase and lipase with CP (n = 9, 11.3%) were reported. Radiological findings were used in the diagnosis of AP in 27 (34.1%) patients. USS, amylase, and CP were reported for 15 (18.9%) patients. Only CECT with CP was reported for six (7.5%) patients. CECT findings, both amylase and lipase, and CP were reported for five (6.3%) patients. CECT findings, amylase, and CP were reported for three (3.7%) patients. CECT findings, lipase, and CP were reported for one (1.2%) patient.

At least one type of leptospirosis diagnostic workup was performed in 54 (68.1%) patients. Measurement of immunoglobulin M (IgM) (n = 39, 49.3%) and performance of a microscopic agglutination test (MAT) (n = 18, 22.7%) were the most common diagnostic modalities. Urine polymerase chain reaction (n = 5, 6.3%), blood polymerase chain reaction (n = 4, 5.0%), dark field microscopy (n = 2, 2.5%), and measurement of immunoglobulin G (n = 3, 3.7%) were the other reported modalities.

Various serovars of Leptospira species were mentioned. Leptospira interrogans Icterohaemorrhagiae (n = 7, 8.8%) and L. interrogans unspecified (n = 5, 6.3%) were the most common types mentioned. Leptospira interrogans Autumnalis and (n = 3, 3.7%) L. interrogans Bratislava (n = 3, 3.7%) were the other common strains reported.

Local and systemic complications

Hemorrhagic pancreatitis (n = 2, 2.5%) and necrotizing pancreatitis (n = 2, 2.5%) were the most common local complications noted. Others included extensive PPNC (n = 1, 1.2%), paralytic ileus (n = 1, 1.2%), and acalculous cholecystitis (n = 4, 5.0%). Acute kidney injury (AKI) (n = 55, 69.6%), thrombocytopenia (n = 32, 40.0%), hypotension (n = 19, 24.0%), liver injury (n = 13, 14.4%), acidosis (n = 10, 12.6%), cardiac involvement (n = 10, 12.6%), and sepsis (n = 8, 10.1%) were the most common complications reported. MOF (n = 6, 7.5%) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 4, 5.0%) were other common complications. Atrial fibrillation (n = 4, 5.0%), bradycardia (n = 4, 5.0%), and meningitis (n = 2, 2.5%) were other notable complications (Table 4). 3 ,6,8,11–15,17,19,21–47

Table 4.

Complications and management of patients with leptospirosis and acute pancreatitis.

| SN | Authors (year) | Local complications | ICU admission | Duration of ICU stay | Duration of hospital stay | Intubation | Treatment | Fluid management (liberal/judicious) | Objective assessment of fluid status | Operative management | Exact type of operative management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maier et al. 21 (2019) | None | Present | NA | 18 | Ventilation given | Meropenem, noradrenaline | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 2 | Jain and Mohan 6 (2013) | Hemorrhagic pancreatitis, extensive peripancreatic fluid collection | Present | NA | Died after 3 days | NA | NA | NA | NA | Operative management | Emergency laparotomy, drain in lesser sac, peritoneal lavage, feeding jejunostomy |

| 3 | Silva et al. 22 (2011) | None | NA | NA | 22 | NA | Ceftriaxone, penicillin G | Liberal | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 4 | Spichler et al. 20 (2007) | Severe pancreatitis | Present | NA | Died after 17 days | NA | Ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 5 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | Hemorrhagic pancreatitis | NA | NA | Died after 6 days | NA | Penicillin G (3 million units IV once daily) | NA | NA | Operative management | Exploratory laparotomy with cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration |

| 6 | Kaya et al. 24 (2005) | None | NA | NA | 19 | NA | Ampicillin/sulbactam | NA | NA | Operative management | Endoscopic nasojejunal feeding tube insertion |

| 7 | Prasanthie and de Silva 15 (2009) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | IV Penicillin, calcium gluconate, sodium bicarbonate, inotropes, platelet transfusion | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 8 | Afzal et al. 25 (2020) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | Doxycycline, anti-coagulation | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 9 | Mazhar et al. 26 (2016) | None | Present | NA | 7 | Ventilation given | Doxycycline, ceftriaxone, metronidazole | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 10 | Ranawaka et al. 13 (2013) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | IV Meropenem (500 mg every 8 h) with penicillin (2 million units every 6 h) for 2 days | Judicious | CVP | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 11 | Yew et al. 27 (2015) | None | Present | NA | NA | Ventilation given | Ceftriaxone (2 g/day) | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 12 | Gomes et al. 54 (2019) | None | Present | NA | Died after 4 days | Intubated | Ampicillin/sulbactam | Judicious | UOP | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 13 | Panagopoulis et al. 29 (2014) | None | Present | NA | NA | NA | Penicillin (1.5 million units every 6 h), meropenem, vancomycin | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 14 | Popa et al. 30 (2013) | Acute necrotizing pancreatitis | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moxifloxacin (1 tablet/day), imipenem/cilastatin (3 g/day), teicoplanin (400 mg/day), rifampicin (600 mg/day) | NA | NA | Operative management | (1) Exploratory laparotomy, drainage of pancreatic head/body abscess, incision and evacuation of retroperitoneal extensions, abdominal extensive lavage, and multiple drains(2) Exploratory laparotomy, mesh removal, re-evacuation and drainage of retroperitoneal extension, extensive lavage and drainage of abdominal cavity(3) Damage control laparotomy and drainage of left retroperitoneal extension, left colic parietal space, and right extremity of transverse mesocolon root |

| 15 | Lim et al. 31 (2014) | Necrotizing pancreatitis, acalculous cholecystitis | NA | NA | 14 | NA | IV Ceftriaxone (2 g once daily for 1 week), IV imipenem (500 mg three times daily for 1 week), IV pantoprazole (40 mg once daily) | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 16 | Mondal et al. 32 (2014) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | Ceftriaxone (1 g IV twice daily or daily) | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 17 | Desai and Hattangadi 14 (2008) | Paralytic ileus | NA | NA | 10 | NA | Cefotaxime, amikacin, metronidazole, octreotide, pantoprazole amoxicillin | NA | UOP | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 18 | Schattner et al. 19 (2020) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | IV Ceftriaxone for 7 days | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 19 | Law et al. 33 (2014) | None | NA | NA | 7 | Ventilation given | Ceftriaxone, azithromycin | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 20 | Castillo et al. 34 (2006) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 21 | Taher et al. 35 (2005) | None | Present | NA | 12 | NA | Procaine penicillin, cefoperazone, cefotaxime | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 22 | Krati et al. 36 (2019) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 23 | Tanriverdi 42 (2009) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | Ampicillin/sulbactam (2 g daily) | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 24 | Baburaj et al. 37 (2008) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | Penicillin C (2 million units every 6 h for 7 days), octreotide (50-mcg infusion every 8 h for 3 days) | Judicious | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 25 | Pribadi et al. 12 (2012) | None | NA | NA | 19 | NA | Ceftriaxone (2 g once daily) | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 26 | Khan et al. 38 (2015) | None | NA | NA | 15 | NA | Ceftriaxone (1 g every 12 h) | Judicious | UOP | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 27 | Thungag et al. 3 (2008) | None | NA | NA | 15 | NA | Penicillin B (1 million units), analgesics and sedatives on as-needed basis | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 28 | Bourquin et al. 8 (2011) | None | Present | 45 days | 70 | Intubated | NA | Judicious | UOP | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 29 | Sharma et al. 39 (2019) | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | Penicillin C (2 million units every 6 h), octreotide (500 mcg every 8 h), pantoprazole (40 mg daily) | Judicious | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 30 | Pal 11 (2019) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable | |

| 31 | Casella and Scatena 43 (2000) | Acute cholecystitis, cholangitis | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dopamine, amoxicillin | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 32 | Maria-Rios et al. 40 (2020) | NA | Present | NA | Discharged after 18 days | Intubated | Vancomycin, metronidazole, ceftriaxone, norepinephrine, vasopressin | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 33 | Simon et al. 41 (2012) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 34 | Monno and Mizushima 44 (1993) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Streptomycin, Clindamycin, Piperacillin. | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 35 | Chong and Goh 45 (2007) | NA | NA | NA | Discharged after 40 days | Intubated | NA | NA | NA | Nonoperative management | Not applicable |

| 36 | Herath et al. 46 (2016) | NA | (6/6) | NA | NA | NA | IV Penicillin, IV Cefotaxime, Doxycycline & IV Hydrocortisone in 6 patients | NA | NA | NA | Not applicable |

| 37 | O’Brien et al. 47 (1999) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Not applicable | ||

| 38 | Kishor et al. 10 (2002) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Not applicable |

| 39 | Daher et al. 17 (2003) | NA | AKI in 12 patients; hypoxia in 11 patients; respiratory failure and hypotension in 7 patients; ARDS in 6 patients; atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, and septic shock in 3 patients; hemorrhagic CVA, hypovolemic shock, splenic rupture, and AV block in 1 patient | NA | Not applicable | Intubation in 7 patients | IV Penicillin, metronidazole, IV furosemide, IV hydrocortisone, and ranitidine in 6 patients | NA | NA | NA | Not applicable |

SN, serial number; NA, not applicable; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; AV block, atrioventricular block; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CVP, central venous pressure; UOP, urine output.

Management and outcomes of AP in patients with leptospirosis

Admission to the ICU was needed for 17 (21.5%) patients. Noninvasive ventilation and intubation were performed in 4 (5.0%) and 11 (13.9%) patients, respectively. Ionotropic support was needed for four (5.0%) patients. Among patients with AKI, hemodialysis (HD) was needed for 20 (25.3%) patients. Urine output and central venous pressure were used for objective assessment of the fluid status in four (5.0%) and one (1.2%) patient, respectively. A judicious fluid regimen was used in six (7.5%) patients, and a liberal fluid regimen was used in one (1.2%) patient (Table 4). 3 ,6,8,11–15,17,19,21–47

Among all 79 patients, intravenous (IV) penicillin G (n = 22, 27.8%), IV ceftriaxone (n = 18, 22.7%), and doxycycline (n = 9, 11.3%) were the most commonly used drugs. Other commonly used drugs were IV hydrocortisone (n = 8, 10.1%), IV meropenem (n = 3, 3.7%), IV imipenem (n = 3, 3.7%), and IV ampicillin sulbactam (n = 3, 3.7%).

Complete recovery was reported for 36 (45.5%) patients. Biochemical and radiological recovery was reported for 10 (12.6%) and 9 (11.3%) patients, respectively. Death was reported in 18 (22.7%) patients. Respiratory failure due to pulmonary hemorrhage (n = 6, 7.5%) and MOF (n = 4, 5.0%) were the most common causes of death. Septic shock (n = 3, 3.7%) and bleeding (n = 2, 2.5%) were the other causes. The cause was not established in two patients.

Operative management was mentioned in only three (3.7%) patients, all of whom underwent exploratory laparotomy. All three patients had features of acute abdomen due to necrotizing pancreatitis, and two patients also had ascites. Two patients underwent necrosectomy and drainage of PPNC. One patient also had acute cholecystitis for which cholecystectomy and bile duct exploration were performed. The histologic findings were compatible with acute cholecystitis. Two patients achieved complete recovery. The outcome of the remaining patient was not reported.

Histological findings were obtained through autopsy and were available in only 13 (17.4%) patients. Among these 13 patients, edema (n = 9, 11.3%) and inflammatory lymphocytic infiltration (n = 8, 10.1%) were the most commonly reported findings. Hemorrhage (n = 5, 6.3%), fat necrosis (n = 3, 3.7%), congestion (n = 3, 3.7%), and calcification (n = 1, 1.2%) were the other findings.

Discussion

This systematic review revealed the clinical characteristics and outcomes of AP associated with leptospirosis. In general, the most common symptoms in patients with leptospirosis included fever, myalgia, occipital headache, red eye, and jaundice. 7 Compared with the aforementioned symptoms, abdominal pain was reported less commonly (30%–40%). 7 In patients with AP, however, abdominal pain was a predominant symptom that was observed in 97% of patients, and it has diagnostic significance according to the modified Atlanta criteria.16,48 Interestingly, abdominal pain in patients with concurrent AP and leptospirosis was not as common in the present review (64.5%). Thus, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required for a definitive diagnosis.

Leptospirosis occurs in two distinct phases: icteric and nonicteric. 49 Most patients with leptospiral infections are asymptomatic and have a nonicteric presentation. 50 Icterus was identified as one of the most common signs in the present review (43%). Frieden 51 reported that the incidence of icterus in patients with AP was 41.3% (n = 75) and that icterus originated from common bile duct enlargement secondary to the inflamed head of the pancreas as evidenced by autopsy. However, icterus is unlikely to be present solely due to pancreatitis in the absence of duct obstruction. 51

Goswami et al. 52 reported that 61.4% of patients with leptospirosis had icterus. Another study showed that among patients with leptospirosis, those with icterus had a higher mortality rate (5%–10%) than those without icterus (1%). 53 In the present review of patients with AP secondary to leptospirosis, the mortality rate was higher among patients with icterus (n = 16, 89%) than among those without icterus (n = 2, 11%). The sensitivity and specificity of an elevated amylase concentration are high on the first day of the CP of AP but decrease thereafter. 54 Smith et al. 55 reported a 76.8% sensitivity and 92.6% specificity for amylase in patients with AP. In the present review, hyperamylasemia was seen in 70.8% of patients with AP secondary to leptospirosis. In previous studies, however, hyperamylasemia has been noted in association with nonpancreatic etiologies. Furthermore, Edwards 49 reported the presence of hyperamylasemia in 65% of patients diagnosed with leptospirosis in the absence of pancreatitis. Daher et al. 17 reported that the presence of AKI in patients with leptospirosis may increase the amylase concentration and make the diagnosis of AP difficult. Therefore, hyperamylasemia must be carefully interpreted to diagnose AP when AKI is present in patients with leptospirosis. 17 A combined assay of elevated lipase and amylase is superior in achieving a diagnosis of AP. 56 This combined assay can be used when hyperamylasemia cannot be interpreted in the context of AP associated with leptospirosis. 56

In this review, IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (49.3%) and MAT (22.7%) were the most common methods of diagnosing leptospirosis. MAT is widely used in the diagnosis of leptospirosis because of its high sensitivity and remains the gold standard. 7 Furthermore, long-term persistence of IgM in the serum may interfere with the identification of acute infection and give rise to false positives. 7

In the present review, AKI (70%), hemodynamic instability (24%), and liver injury (14%) were the most common complications reported. The reported incidence of AKI in patients with leptospirosis ranges from 40% to 60%. 17 The presence of AKI increases the risk of mortality in patients with leptospirosis. 57 Daher et al. 17 reported a 22% mortality rate in patients with leptospirosis complicated by AKI. AKI also occurs in patients with severe AP. 58 Devani et al. 59 reported that the incidence of AKI in patients with AP was 7.9% (n = 3,466,493). The mortality rate is increased in patients with concurrent AKI and AP. 60 Thus, the presence of AKI carries a poor prognosis in patients with both leptospirosis and AP. 59 Furthermore, oliguria has been found to be an important prognostic factor in patients with leptospirosis.7,61 Therefore, patients with AP and leptospirosis should be carefully monitored and managed for AKI, and care should be taken to avoid iatrogenic causes of AKI such as drugs and contrast-induced nephropathy. In our review, we found that most patients with AKI needed HD (n = 20, 25.3%). Previous studies have shown that HD can be delayed up to 72 hours following the identification of AKI in patients with leptospirosis. 61 Low-volume HD is preferred to prevent pulmonary hemorrhage in patients with concurrent leptospirosis and AKI. 5 In our review, the mortality rate among patients with AKI was considerably high (29%).

Thrombocytopenia is an important hematological marker in the diagnosis and prognostication of leptospirosis and has been identified in more than 50% of patients.49,62 Furthermore, thrombocytopenia is a significant predictor of AKI in patients with leptospirosis and has been shown to correlate with mortality.63,64 However, various platelet abnormalities may be noted in patients with severe AP, including thrombocytopenia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.65–67 The recorded incidence of thrombocytopenia in patients with AP ranges from 36% to 43%. 66 Furthermore, the presence of thrombocytopenia has been shown to correlate with severe complications and ICU admission in patients with AP. 65 In the present review, thrombocytopenia was present in 50% of patients with concurrent AP and leptospirosis and could be attributable to the combined influence of both AP and leptospirosis. Furthermore, approximately 16% of patients with thrombocytopenia were admitted to the ICU. However, only one (3.2%) patient died among all patients with thrombocytopenia.

In our review, the most common radiological modalities used to diagnose pancreatitis were CECT (26.5%) and abdominal USS (21.0%). USS has a sensitivity of 62% to 90% in diagnosing pancreatitis in general, whereas CECT has an accuracy of 82% to 90% with 100% specificity.68–70 Furthermore, less than 3% of PPNC is missed in CECT. 69 USS is the preferred initial imaging modality to exclude biliary stones, which are among the most common etiologies of AP. 68 Silverstein et al. 71 conducted a study on pancreatic imaging and concluded that pancreatic CECT was superior to abdominal USS because CECT had an increased diagnostic yield (38%). However, CECT has the disadvantage of contrast administration to patients with leptospirosis who have impaired renal function. 68 Magnetic resonance imaging can be a good alternative in such patients. 68 In patients with the severe form of leptospirosis (Weil disease), the mortality rate ranges from 10% to 15%.23,72,73 Severe AP is associated with a mortality rate of 20%.74,75 In our review, death was reported in 18 (31.03%) patients who had concurrent AP and leptospirosis. Furthermore, respiratory failure due to pulmonary hemorrhage was the most common cause of death found in our review.

To overcome the challenges in diagnosing AP in patients with leptospirosis, we recommend a high degree of clinical suspicion combined with routine biochemical assays, including measurement of the serum amylase and lipase concentrations, and a basic USS. CECT should be reserved for select patients with diagnostic uncertainty and assessment of complications, and extreme caution is needed in the presence of AKI. Among patients who live in or have traveled to an area endemic for leptospirosis, those who have AP and jaundice without bile duct dilation should be promptly screened for leptospirosis. Although management includes antibiotics and supportive care, judicious fluid management is also required, preferably with monitoring of the central venous pressure or inferior vena cava filling and close examination for AKI. Surgical management should be the last option. Minimally invasive approaches are more advisable than exploratory laparotomy to avoid the morbidity induced by major surgery in physiologically compromised patients. A consensus statement or guidelines to manage severe pancreatitis in the context of leptospirosis should be developed by experts.

Limitations

This review had several limitations. Heterogeneity in the reporting of case reports and case series was noted, and a meta-analysis was therefore not feasible. Relatively few patients with concurrent AP and leptospirosis have been reported in the literature. Many data were missing and the reporting was incomplete, leading to inaccuracies in the data extraction and analysis. There were also considerable variations in the choice of investigations and management because of the lack of standard guidelines for management of AP in the setting of leptospirosis. Furthermore, the disease outcomes are likely to have been influenced by other complications of leptospirosis.

Conclusion

AP is uncommon but may give rise to severe complications in patients with leptospirosis. A high degree of clinical suspicion and different modalities of investigations are essential to achieve a correct diagnosis. AP can be easily missed in patients with leptospirosis because both conditions share similar CPs and complications. Judicious fluid management with monitoring for AKI is an essential component of supportive management. Mortality and morbidity are considerably higher when both AP and leptospirosis are present. A consensus statement or guidelines to manage severe pancreatitis in the context of leptospirosis is warranted.

Authors’ contributions: UJ, JCC, and DS conceived and designed the study, acquired and analyzed the data, and drafted the article. UJ, JCC, and DS collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data and wrote the article. UJ, JCC, and DS contributed to the design and conception of the study, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in the above analysis will be available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD

James C Charles https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1667-7150

References

- 1.Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JNet al. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3: 757–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayachari P, Sugunan AP, Shriram AN. Leptospirosis: an emerging global public health problem. J Biosci 2008; 33: 557–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thungag, Mallayasamy SR, Mangasuli Set al. A case report of leptospirosis induced acute pancreatitis. J Clin Diag Res 2008; 2: 1100–1102. Available from http://www.jcdr.net/back_issues.asp?issn=0973-709x&year=2008&month=october&volume=2&issue=5&page=1100-1102&id=306. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartskeerl RA, Collares-Pereira M, Ellis WA. Emergence, control and re-emerging leptospirosis: dynamics of infection in the changing world. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17: 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramachandran S, Perera MVF. Cardiac and pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1977; 71: 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain AK, Mohan LN. Acute necrotising pancreatitis associated with leptospirosis—a case report. Indian J Surg 2013; 75: 245–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001; 14: 296–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourquin V, Ponte B, Hirschel Bet al. Severe leptospirosis with multiple organ failure successfully treated by plasma exchange and high-volume hemofiltration. Case Rep Nephrol 2011; 2011: 817414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Koning J, Van der Hoeven JG, Meinders AE. Respiratory failure in leptospirosis (Weil’s disease). Neth J Med 1995; 47: 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishor KK, Rao PV, Bhat KRet al. Pancreatitis in Weil’s disease. Trop Doct 2002; 32: 230–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal S. An unusual presentation of Weil’s disease. J Assoc Physicians India 2019; 67: 86–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pribadi RR, Efiyanti C, Zakaria Ret al. Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis as a complication of Weil’s disease. Indones J Gastroenterol Hepatol Dig Endosc 2012; 13: 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranawaka N, Jeevagan V, Karunanayake Pet al. Pancreatitis and myocarditis followed by pulmonary hemorrhage, a rare presentation of leptospirosis- a case report and literature survey. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai A, Hattangadi D. Leptospirosis as a rare cause of acute pancreatitis. Internet J Surg 2008; 20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasanthie H, De Silva K. A rare complication of leptospirosis: acute pancreatitis. Galle Med J 2009; 13: 69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster BR, Jensen KK, Bakis Get al. Revised Atlanta Classification for acute pancreatitis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics 2016; 36: 675–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daher Ede F, Brunetta DM, De Silva Júnior GBet al. Pancreatic involvement in fatal human leptospirosis: clinical and histopathological features. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2003; 45: 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koo BC, Chinogureyi A, Shaw AS. Imaging acute pancreatitis. Br J Radiol 2010; 83: 104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schattner A, Dubin I, Glick Yet al. Acute painless pancreatitis as an unusual presentation of leptospirosis in a low-incidence country. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e234988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spichler A, Spichler E, Moock Met al. Acute pancreatitis in fatal anicteric leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 886–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maier A, Kaeser R, Thimme Ret al. Acute pancreatitis and vasoplegic shock associated with leptospirosis – a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva AP, Burg LB, Schadeck Locatelli JFet al. Leptospirosis presenting as ascending progressive leg weakness and complicating with acute pancreatitis. Braz J Infect Dis 2011; 15: 493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spichler A, Moock M, Chapola EGet al. Weil’s disease: an unusually fulminant presentation characterized by pulmonary hemorrhage and shock. Braz J Infect Dis [Internet] 2005; 9: 336–340. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-86702005000400011&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaya E, Dervisoglu A, Eroglu Cet al. Acute pancreatitis caused by leptospirosis: report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 4447–4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afzal I, Thaker R, Weissman Set al. Leptospirosis as an unusual culprit of acute pancreatitis and portal vein thrombosis in a New Yorker. Clin Case Rep 2020; 8: 690–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazhar M, Kao JJ, Bolger DT., Jr. A 23-year-old man with leptospirosis and acute abdominal pain. Hawaii J Med Public Health 2016; 75: 291–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yew KL, San Go C, Razali F. Pancreatitis and myopericarditis complication in leptospirosis infection. J Formos Med Assoc 2015; 114: 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez D, Addison A, De Rosa Aet al. Retrospective study of patients with acute pancreatitis: is serum amylase still required? BMJ Open 2012; 2: e001471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panagopoulos P, Terzi I, Karanikas Met al. Myocarditis, pancreatitis, polyarthritis, mononeuritis multiplex and vasculitis with symmetrical peripheral gangrene of the lower extremities as a rare presentation of leptospirosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 2014; 8: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popa D, Vasile D, Ilco A. Severe acute pancreatitis – a serious complication of leptospirosis. J Med Life 2013; 6: 307–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim SM, Hoo F, Sulaiman WAet al. Acute necrotising pancreatitis and acalculous cholecystitis: a rare presentation of leptospirosis. J Pak Med Assoc 2014; 64: 958–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mondal S, Ete T, Sinha Det al. Leptospirosis complicated with meningoencephalitis and pancreatitis -a case report. Int J Med Res Health Sci 2014; 3: 477. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law AD, Som R, Bhalla A. Painless pancreatitis: an unusual presentation of leptospirosis. SCh J Med Case Rep 2014; 2: 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castilo J, Alvarez M, Hernandex MEet al. Pancreatitis due to Leptospira: about a case. Gene [Internet] 2006. Accessed 3 Sept 2023. Available from: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0016-35032006000300013&lng=es.

- 35.Taher DN, Abdullah M, Marcellus Simadibrata Ket al. Leptospirosis and pancreatitis complication. Indones J Gastroenterol Hepatol Dig Endosc 2005; 6: 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krati K, Haraki I, ELyazal Set al. Acute pancreatitis reveals leptospirosis in 18-year-old: a new observation. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access [Internet] 2019; 10: 123‒124. Available from: https://medcraveonline.com/GHOA/acute-pancreatitis-reveals-leptospirosis-in-18-year-old-a-new-observation.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baburaj P, Antony T, Louis Fet al. Acute abdomen due to acute pancreatitis–a rare presentation of leptospirosis. J Assoc Physicians India 2008; 56: 911–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan R, Quaiser S, Khan F. Anicteric leptospirosis: an unusual cause of acute pancreatitis. Community Acquir Infect 2015; 2: 107. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma ZP, Sharma D, Sharma R. Case of acute abdomen due to acute pancreatitis: a uncommon presentation of leptospirosis. Int J Res Med Sci 2019; 7: 3183. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maria-Rios JC, Marin-Garcia GL, Rodriguez-Cintron W. Renal replacement therapy in a patient diagnosed with pancreatitis secondary to severe leptospirosis. Fed Pract 2020; 37: 576–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon F, Morand G, Roche Cet al. Leptospirosis in a French traveler returning from Mauritius. J Travel Med 2012; 19: 69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanrıverdi Ö. Case report: acute pancreatitis and acalculous acute cholecystitis in a patient with leptospirosis. Med Bull Haseki 2009; 47: 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casella G, Scatena LF. Mild pancreatitis in leptospirosis infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 1843–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monno S, Mizushima Y. Leptospirosis with acute acalculous cholecystitis and pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1993; 16: 52–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chong VH, Goh SK. Leptospirosis presenting as acute acalculous cholecystitis and pancreatitis. Ann Acad Med Singap 2007; 36: 215–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herath NJ, Kamburapola CJ, Agampodi SB. Severe leptospirosis and pancreatitis; a case series from a leptospirosis outbreak in Anuradhapura district, Sri Lanka. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Brien MM, Vincent JM, Person DAet al. Leptospirosis and pancreatitis: a report of ten cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998; 17: 436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Földi M, Gede N, Kiss Set al. The characteristics and prognostic role of acute abdominal on‐admission pain in acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort analysis of 1432 cases. Eur J Pain 2022; 26: 610–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards CN. Leptospirosis and pancreatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999; 18: 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berman SJ, Tsai CC, Holmes Ket al. Sporadic anicteric leptospirosis in South Vietnam. A study in 150 patients. Ann Intern Med 1973; 79: 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frieden JH. The significance of jaundice in acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1965; 90: 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goswami RP, Goswami RP, Basu Aet al. Predictors of mortality in leptospirosis: an observational study from two hospitals in Kolkata, eastern India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014; 108: 791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haake DA, Levett PN. Leptospirosis in Humans. In: Adler B, editor. Leptospira and Leptospirosis [Internet] Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2015. [cited 2022 Jul 24]. p. 65–97. (Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; vol. 387). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-662-45059-8_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Gomes PEAC, Brilhante SO, Carvalho RBet al. Pancreatitis as a severe complication of leptospirosis with fatal outcome: a case report. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2019; 61: e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith RC, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D. Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis? ANZ J Surg 2005; 75: 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keim V, Teich N, Fiedler Fet al. A comparison of lipase and amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients with abdominal pain. Pancreas 1998; 16: 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daher Ede F, De Abreu KL, Da Silva Junior GB. Leptospirosis-associated acute kidney injury. J Bras Nefrol 2010; 32: 400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abdulkader RC, Silva MV. The kidney in leptospirosis. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23: 2111–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Devani K, Charilaou P, Radadiya Det al. Acute pancreatitis: trends in outcomes and the role of acute kidney injury in mortality- a propensity-matched analysis. Pancreatology 2018; 18: 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathew AJ, George J. Acute kidney injury in the tropics. Ann Saudi Med 2011; 31: 451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daher EF, Silva GB, Jr, Karbage NNet al. Predictors of oliguric acute kidney injury in leptospirosis. Nephron Clin Pract 2009; 112: C25–C30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Everard COR, Callender J, Nicholson GDet al. Thrombocytopenia in leptospirosis: the absence of evidence for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1986; 35: 352–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turgut M, Sünbül M, Bayirli Det al. Thrombocytopenia complicating the clinical course of leptospiral infection. J Int Med Res 2002; 30: 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma J, Suryavanshi M. Thrombocytopenia in leptospirosis and role of platelet transfusion. Asian J Transfus Sci 2007; 1: 52–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ali MA, Shaheen JS, Khan MA. Acute pancreatitis induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Indian J Crit Care Med 2014; 18: 107–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaquero E, Casellas F, Bisbe Vet al. [Thrombocytopenia onset in acute episodes of pancreatitis]. Med Clin (Barc) 1995; 105: 334–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thachil J. Lessons from acute pancreatitis-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Intern Med 2009; 20: 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah A, Mourad M, Bramhall S. Acute pancreatitis: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. J Inflamm Res 2018; 11: 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balthazar EJ, Freeny PC, VanSonnenberg E. Imaging and intervention in acute pancreatitis. Radiology 1994; 193: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan DE, Baron TH. Practical imaging in acute pancreatitis. Semin Gastrointest Dis 1998; 9: 41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silverstein W, Isikoff M, Hill Met al. Diagnostic imaging of acute pancreatitis: prospective study using CT and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1981; 137: 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inada R, Ido Y, Hoki Ret al. The etiology, mode of infection, and specific therapy of Weil’s disease (spirochaetosis icterohaemorrhagica). J Exp Med 1916; 23: 377–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forbes AE, Zochowski WJ, Dubrey SWet al. Leptospirosis and Weil’s disease in the UK. QJM 2012; 105: 1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Popa CC, Badiu DC, Rusu OCet al. Mortality prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. J Med Life 2016; 9: 413–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fu CY, Yeh CN, Hsu JTet al. Timing of mortality in severe acute pancreatitis: experience from 643 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 1966–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the above analysis will be available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.