Abstract

Drug resistance is still a big challenge for cancer patients. We previously demonstrated that inhibiting peptidylarginine deiminase 2 (PADI2) enzyme activity with Cl-amine increases the efficacy of docetaxel (Doc) on tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells with PADI2 expression. However, it is not clear whether this effect applies to other tumour cells. Here, we collected four types of tumour cells with different PADIs expression and fully evaluated the inhibitory effect of the combination of PADIs inhibitor (BB-Cla) and Doc in vitro and in vivo on tumour cell growth. Results show that inhibiting PADIs combined with Doc additively inhibits tumour cell growth across the four tumour cells. PADI2-catalysed citrullination of MEK1 Arg 189 exists in the four tumour cells, and blocking the function of MEK1 Cit189 promotes the anti-tumour effect of Doc in these tumour cells. Further analysis shows that inhibiting MEK1 Cit189 decreases the expression of cancer cell stemness factors and helps prevent cancer cell stemness maintenance. Importantly, this combined treatment can partially restore the sensitivity of chemotherapy-resistant cells to docetaxel or cisplatin in tumour cells. Thus, our study provides an experimental basis for the combined therapeutic approaches using docetaxel- and PADIs inhibitors-based strategies in tumour treatment.

This article is part of the Theo Murphy meeting issue ‘The virtues and vices of protein citrullination’.

Keywords: peptidylarginine deiminase, chemotherapy resistance, citrullination, cancer cell stemness

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy drug docetaxel (Doc), a second-generation taxane, is generally recommended to be used to treat a variety of cancers, due to its ability to prolong the survival time of cancer patients [1–3]. However, the use of a single chemotherapy drug does not achieve the desired effect [4,5], and long-term use of chemotherapy drugs is also prone to drug resistance [6,7]. Therefore, for the treatment of patients with advanced tumours, a combination of multiple drugs is often applied [8–10]. Additionally, the combined therapy strategy not only helps increase the efficacy of chemotherapeutics, but also decreases the dosage of the drugs, as prolonged and high-dose chemotherapy is easily associated with safety issues among clinical trial patients including asthenia, cutaneous reactions, hematological issues and neurosensory reactions [11,12]. For example, Park et al. [13] demonstrated that the combination of baicalein and Doc reduced the malignancy of thyroid cancer compared with monotherapy. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester combined with docetaxel treatment in Doc-resistant prostate cancer cells increased the apoptosis of tumour cells and interfered with the survival and proliferation of Doc-resistant prostate cancer cells [14]. Therefore, it is urgently needed to identify new therapeutic targets that can be combined with other existing chemotherapy drugs for cancer treatment.

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) are actively involved in regulating a wide range of cellular biological processes by altering the structure and dynamics of proteins [15–19]. Accumulated studies have proved that the occurrence and development of tumours are closely related to the disorder of PTMs in tumour cells [20–22]. PTMs thus provide an abundance of potential candidates for tumour biomarker detection [23]. Accordingly, the upstream regulators of PTMs in tumour cells, such as acetyltransferases, kinases or methyltransferases, are becoming potential therapeutic targets for cancers [24]. Citrullination represents a new member of the PTMs family. It is catalysed by peptidylarginine deiminase (PADI) enzymes, which hydrolyze a guanidino group of the positively charged arginine into a urea group of neutrally charged citrulline, thereby affecting the molecular conformation of the target protein [25], and eventually affecting the biological behaviour of cells, such as cell proliferation, differentiation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in multiple human cancer cells [16,19,25–27]. There are five PADI members in the family, including PADI1–4 and PADI6. Except for PADI6, which is specifically expressed in the ovary and has no enzymatic activity [28], all the other PADIs have the ability to catalyse protein citrullination [25,27]. Though PADI expression varies across different tumours [29–36], most of them are positively correlated with the onset and progression of cancers [33,37,38], indicating the crucial roles of PADIs in tumourigenesis. Importantly, the synthetic PADI inhibitors designed to inhibit PADIs catalytic activity have been shown to successfully kill a selection of cancerous cell lines, further strengthening the possibility of using PADI-catalysed citrullination as a promising therapeutic target for tumour therapy [31,39,40].

Previously we have shown that peptidylarginine deiminase 2 (PADI2) was upregulated in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells (MCF7/TamR) and inhibiting PADI2 not only partially restored the sensitivity of MCF7/TamR cells to tamoxifen, but also more efficiently enhanced the efficacy of docetaxel on MCF7/TamR cells with even lower doses of PADI inhibitor and docetaxel [31]. In this study, we sought to further verify the additive anti-tumour effect of this combined treatment on different tumour cells with PADI expression, explore the molecular mechanism of this superposition, and anticipate providing a novel therapeutic approach to improve clinical practice in treatment of patients with advanced tumours.

2. Material and methods

(a) . Cell culture

ISI cells, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). MCF7/TamR cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 µM of tamoxifen. HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For BB-Cla treatment, cells were exposed to 20 µM BB-Cla for 24 h, 48 h or 72 h [29]. For Doc treatment, cells were exposed to 100 nM Doc for 24 h, 48 h or 72 h [31]. In the combination group, cells were exposed to 20 µM BB-Cla and 100 nM Doc for 24 h, 48 h or 72 h. For the construction of chemotherapy-resistant cell lines, ISI cells were exposed to 100 nM Doc or 5 µM Cis for six months, until cells were selected [31,41,42].

(b) . Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted with RNA isolater Total RNA Extraction Reagent (Vazyme R401-1), and reversely transcribed into cDNA with the HiScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme R111-01). For quantitative real-time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR), Vazyme's Sybrgreen Mix (Vazyme Q111-02) was used for PCR with the cDNA and gene-specific primer pairs. GAPDH was used as an internal control for gene expression, and the relative expression of target gene transcripts was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences used in this study include, PADI1, 5′-GAGTG ATGGA CACTC ATGGC-3′ (F), 5′-CAGAT GGTCA GCTTG CAGTT-3′ (R); PADI2, 5′-TCTCA GGCCT GGTCT CCAT-3′ (F), 5′-AAGAT GGGAG TCAGG GGAAT-3′ (R); PADI3, 5′-AGCAA TGACC TCAAC GACAG-3′ (F), 5′-TGAGG TAGAG CACCG CATAG-3′ (R); PADI4, 5′-TCACC TACCA CATCA GGCAT-3′ (F), 5′-CATGT TCCAC CA CTT GAAGG-3′ (R); CDKN1A, 5′- TGTCC GTCAG AACCC ATGC-3′ (F), 5′-AAAGT CGAAG TTCCA TCGCT C-3′ (R); GADD45A, 5′-CTGCG AGAAC GACAT CAA-3′ (F), 5′-CCTTC CATTG AGATG AATGT G-3′ (R); FAS, 5′-TCGTA ATTGG CATCA ACTTC-3′ (F), 5′-CCTTG AGGAT GATAG TCTGA A-3′ (R); BAG3, 5′-AAGGC AAGAA GACTG ACAA-3′ (F), 5′-ATAGA CCTGG ACTTG ACCT-3′ (R); GAPDH, 5′-GAAAT CCCAT CACCA TCTTC CAGG-3′ (F), 5′-GAGCC CCAGC CTTCT CCATG-3′ (R).

(c) . Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a seeding quantity of 5000 cells/well. After cells adhered to the well, drugs were added accordingly. After 24, 48 and 72 h of culture, cells were collected, followed by incubation with CCK-8 mixed solution (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) for 2 h. Absorbance at OD450 was recorded with a micro-plate reader. Based on the absorbance values, the relative cell viability capacity in each group was calculated.

(d) . Nuclear and cytoplasmic extract preparations

The cells were washed 3 times with pre-cooled PBS, then lysed on ice with cold cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH = 7.4; 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1% NP40, 1× proteinase inhibitors) for 60 min. The lysates were then centrifuged and the supernatants were collected as cytoplasmic fraction. The cell nuclear pellets were washed and then lysed with cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH = 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP40, 1× proteinase inhibitors). The supernatants were centrifuged and collected as nuclear fraction.

(e) . Transwell invasion assay

A transwell invasion assay was performed in 24-well plates with 8 µm pore-size chamber inserts (Corning, USA), according to the protocols recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the upper surface of the filter was coated with 50 µl of Matrigel diluted 1 : 3 in serum-free DMEM. Approximately 5000 cells were added to the upper chamber of a Matrigel-coated transwell plate (Corning) and cultured in serum-free DMEM. The lower compartment of the transwell chamber was filled with 600 µl complete media. Cells on the lower surface were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 0.1% crystal violet and photographed in three independent fields for each well under light microscope. After taking pictures, Image J software was used to count the cells, and the number of cells reflected the relative invasion ability of each group of cells.

(f) . Antibody transfection

For transfection of anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody into cells, we used ‘PULSin’ Protein Delivery Reagent (Polyplus, no. 501-04, Shanghai, China). Briefly, 1 µg of anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody was complexed with 4 µl ‘PULSin’ Protein Delivery Reagent, and added dropwise to the cell culture medium. After 48 h, the transfection efficiency of the antibody was detected using a Fluor 486-conjugated secondary antibody, and then subsequent experiments were performed. The anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody was generated and its specificity was validated as described in our previous study [29].

(g) . Immunofluorescence staining

Cells grown on slides and transfected with anti-MEK1Cit 189 antibody were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking with 4% BSA, cells were incubated with Fluor 486-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at room temptation for 1 h. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Cambridgeshire, UK). Representative images were collected with an LSM 700 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

(h) . Western blot

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing protease inhibitors was used to extract total proteins, and the lysates were boiled for 5 min before being subjected to 10% SDS–PAGE. The proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: anti-P53 (no. 60283-2-Ig, Proteintech, China), anti-Cit189 (homemade, AtaGenix Biotechnology, China), anti-MEK1 (no. 8272, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), anti-CD133 (no. Ab19898, Abcam, USA), anti-SOX2 (no. 11064-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-Histone3 (no. 17168-1-AP, Proteintech) and anti-GAPDH (no. AP0063, Bioworld Technology, China). The membranes were washed and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. The signals were visualized using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, USA).

(i) . Apoptosis evaluation by flow cytometry

Apoptotic cells were detected using the Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Yeasen). Briefly, cells were washed and cell pellets were re-suspended in ice-cold binding buffer. Subsequently, 5 µl Annexin V-FITC solution and 5 µl propidium iodide (PI) were added to the cell suspension. After gentle mixing, samples were incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. A FACScan flow cytometer was applied to quantify cellular apoptosis. Cells with Annexin V-positive and PI-negative staining were denoted as early apoptosis, with Annexin V-positive and PI-positive as late apoptosis. Statistically, both types of cells are considered apoptotic cells.

(j) . Xenograft tumour model in nude mice

Female BALB/c nude mice (six weeks old) were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China) and maintained in a special pathogen-free (SPF) environment. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University. Cells (1 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into the left upper flank of mice. Solid tumour masses were formed three weeks post cell inoculation. The tumour-bearing mice were randomly divided into four groups, and intraperitoneally injected with the following solution: PBS, BB-Cla, Doc and BB-Cla + Doc. The dosage was: BB-Cla group, 20 mg kg time, once every 3 days; Doc group, 10 mg kg time, once every 3 days; combination group, inject two drugs at the same time as a single dose; PBS group, inject an equal volume of PBS. We injected 10 nude mice per group for ISI cells; 8 nude mice per group for MDA-MB-231 cells; 5 nude mice per group for HCT116 cells and 5 nude mice per group for MCF7/TamR cells. After three weeks of administration, the nude mice were euthanized, and the tumour mass was weighed and recorded.

(k) . Immunoprecipitation assay

MCF7/TamR cell lysate was collected, followed by the addition of 5 µg anti-Cit189 antibody. An equal amount of rabbit IgG was used as a negative control. After incubation overnight at 4°C, 20 µl rProtein A/G Agarose Resin (Yeasen, 36403ES08) was added into the mixture and incubated for another 6 h. Then, the resin was washed with lysis buffer three times and the proteins bound to the resin were eluted, followed by western blot analysis with anti-MEK1 antibody.

(l) . Short interferring RNA transfection

For transiently knocking down PADI expression in MCF7/TamR cells, siRNA transfection was performed when cells were grown until 70–80% confluency. Briefly, both the siRNAs and the transfection reagent Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher, L3000001) were separately diluted with Opti-MEM, and then mixed gently. The above mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 min, and added to the cells dropwise. After 48 h, cells were collected for analyses.

(m) . Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in at least three biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. Statistical evaluation for data analysis was determined using Student's t-tests between two groups, or one-way ANOVA among four groups to compare the difference. Differences were considered significant at *p < 0.05.

3. Results

(a) . The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively inhibits the viability of tumour cells with PADIs expression

PADIs are widely expressed in a variety of tumour cells. We previously showed that PADI1 is relatively highly expressed in human triple negative breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cells, compared to other PADI family members [30], while PADI2 is the main PADI expressed in both Ishikawa human endometrial carcinoma (ISI) and tamoxifen-resistant human breast cancer (MCF7/TamR) cells [29,31]. There are also reports showing that PADI1-4 can be detected in colon cancer cells [43–47]. To further confirm the expression levels of PADIs in these selected cells, we performed qRT-PCR analysis and showed that PADI2 was highly expressed in ISI cells and MCF7/TamR cells. Of note, PADI2 still showed a relatively high expression level in HCT-116 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells, though PADI4 and PADI1 seemed to be the primary PADI, respectively, in these two cells (figure 1a). In order to evaluate the combined effect of PADIs inhibitor and Doc on the cellular growth of these PADIs-expressed tumour cells, we treated four tumour cell lines with BB-Cl-amidine (BB-Cla, a modified version of Cl-amidine) and Doc. As assessed by CCK-8 assay, either 20 µM BB-Cla or 100 nM Doc treatment significantly inhibited the tumour cell growth compared to the control, while the combined treatment with BB-Cla and Doc showed an additive inhibitory effect as compared to individual treatment (figure 1b). Further, we tested the synergy of the BB-Cla and Doc in tumour growth in vivo. Six-week-old nude mice were subcutaneously inoculated with these four cells, respectively. After solid tumours were formed, drugs were then injected intraperitoneally once every 3 days for three weeks. Results showed that administration of either BB-Cla or Doc alone reduced the tumourigenic ability of the four tumour cell lines, while the combined treatment significantly decreased the tumour weight compared to that of each single treatment (figure 1c).

Figure 1.

The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively inhibits the viability of tumour cells with PADIs expression. (a) Relative expression levels of PADI mRNAs detected in four cell lines by qRT-PCR. n = 3. (b) CCK-8 assay showing the relative cell viability for the four tumour cells after treatment with 20 µM BB-Cla, 100 nM Doc or the combination treatment with 20 µM BB-Cla and 100 nM Doc. ISI cells, HCT116 cells, MDA-MB-231 and MCF7/TamR cells in panels from left to right. n = 3, *p < 0.05. (c) The average tumour weight was quantified for the xenograft tumour mouse model. The number of tumours from each group was denoted by dots. *p < 0.05.

(b) . The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively promotes apoptosis of tumour cells with PADIs expression

Further, we performed flow cytometric analysis to evaluate cell apoptosis upon the drug treatment. Annexin V staining results showed that cell apoptosis was observed after exposure of four tumour cells to either BB-Cla or Doc, while the combination treatment significantly accelerated the cell apoptotic rate as compared to each individual treatment (figure 2a). Given that we have previously shown an accumulation between PADIs inhibitor and Doc in enhancing p53 nuclear accumulation, leading to accumulative cell apoptosis in MCF7/TamR cells [31], we then tested whether this accumulation between BB-Cla and Doc also exists in the other tumour cells. Results confirmed that the combined treatment additively enhanced p53 nuclear accumulation in all four tumour cells (figure 2b and electronic supplementary material, S1). We then further detected the expression of p53 target genes, and the results confirmed that the combination treatment also increased the expression of apoptosis-related genes CDKN1A, GADD45A, FAS and BAG3, consistent with the increased nuclear accumulation of p53 (figure 2c). These results suggested that inhibiting PADIs combined with docetaxel can additively inhibit tumour cell growth in those tumours with PADIs expression.

Figure 2.

The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively promotes the apoptosis of tumour cells with PADIs expression. (a) Relative apoptosis rate of the four tumour cells under conditions as indicated. The cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. Annexin-FITC was used to mark apoptotic cells. n = 3, *p < 0.05. (b) Cellular proteins were separated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions and examined by western blot with anti-p53 antibody. Cell fractionation was determined by probing with antibodies against histone H3 (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytoplasmic). n = 3. (c) qRT-PCR assay showing the relative mRNA expression level of apoptosis-related genes for the ISI cell after treatment with 20 µM BB-Cla, 100 nM Doc or the combination treatment. n = 3, *p < 0.05.

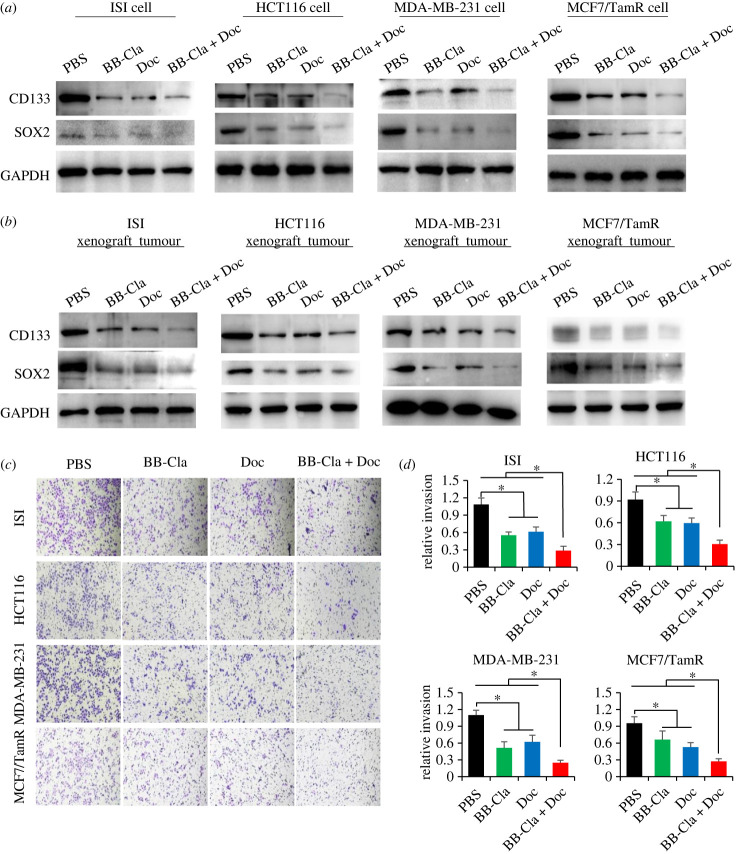

(c) . The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively inhibits the stemness characteristics of tumour cells with PADIs expression

We have previously demonstrated that inhibiting MEK1 R189 citrullination can reduce the expression of the tumour stemness gene SOX2 in ISI cells [29]. It is generally accepted that poorly differentiated tumours express high levels of stemness-related factors, such as SOX2, OCT4 and CD133 [48–50]. We then tested the expression of these stemness-related factors in the four tumour cell lines. Results showed that BB-Cla or Doc treatment alone obviously decreased the expression of CD133 and SOX2, while the expression of these stemness-related factors was further reduced after the combined treatment (figure 3a and electronic supplementary material, S2a). We also tested the expression of these factors in our xenograft mouse tumours. Consistent with the results obtained from the in vitro cell culture, BB-Cla combined with Doc has an obviously additive inhibitory effect against the expression of CD133 and SOX2 in tumour tissues (figure 3b and electronic supplementary material, S2b). Of note, the invasive ability of tumour cells is closely related to the characteristics of tumour stemness [51,52]. We continued to detect the changes of the cell invasive ability upon drug treatment. As shown in figure 3c,d, either BB-Cla or Doc treatment reduced the invasion ability of these tumour cells, while the combined treatment further reduced the tumour cell invasion ability. These results suggested that inhibiting PADIs enzymatic activity can enhance the suppressive effect of Doc on PADIs-expressed tumour cells through additively decreasing the stemness characteristics of tumour cells.

Figure 3.

The combination of BB-Cla and Doc additively inhibits the tumour stemness characteristics of tumour cells with PADIs expression. (a) Cells were treated with 20 µM BB-Cla, 100 nM Doc or a combination of 20 µM BB-Cla and 100 nM Doc for 48 h, followed by western blot analysis to detect the protein levels of CD133 and SOX2. GAPDH was used as a loading control. n = 3. (b) Western blot detection of protein levels of CD133 and SOX2 in the mouse xenograft tumour tissue with injection of ISI cells, HCT116 cells, MDA-MB-231 cells or MCF7/TamR cells, respectively. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (c,d) Representative images (c) and quantification (d) for transwell assay in different tumour cells under treatments as indicated. n = 3, *p < 0.05.

(d) . BB-Cla inhibits MEK1 Arg189 citrullination in tumour cells with PADI2 expression

In our previous work, we showed that PADI2 interacts with MEK1 and catalyses the citrullination of MEK1 Arg189 (Cit189), thereby activating the MEK1–ERK signalling pathway and promoting endometrial cancer tumourigenesis [29]. We thus wondered whether BB-Cla treatment in these cells may also affect the citrullination of MEK1 at Arg189. Results showed that inhibiting PADIs enzymatic activity with BB-Cla obviously reduced MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 (figure 4a and electronic supplementary material, S3a). The existence of Cit189 modification in the four tumour cells was also validated in the xenograft mouse tumours (figure 4b–e and electronic supplementary material, S3b). Furthermore, we evaluated the degree of MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 in MCF7/TamR cells. To this end, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments with the anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody and probed the pulled down MEK1 protein with the anti-MEK1 antibody. Results showed that citrullinated MEK1 accounts for nearly 40% of total MEK1 in MCF7/TamR cells (electronic supplementary material, figure S3c,d). Although knockdown of either PADI2 or PADI4 reduced cell viability, only PADI2 depletion significantly reduced MEK1 Cit189 (electronic supplementary material, figure S3e–h), suggesting that BB-Cla may prefer to inhibit PADI2 activity on MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 in MCF7/TamR cells, which is similar to that in ISI cells [29].

Figure 4.

BB-Cla inhibits the expression of MEK Cit189 of tumour cells with PADIs expression. (a) Cells were treated with 20 µM BB-Cla, 100 nM Doc or a combination of 20 µM BB-Cla and 100 nM Doc for 48 h, followed by western blot analysis to detect the protein levels of MEK1 Cit189 and total MEK1. GAPDH was used as a loading control. n = 3. (b–e) Western blot detection of protein levels of MEK1 Cit189 and total MEK1 in the mouse xenograft tumour tissue with injection of ISI cells (b), HCT116 cells (c), MDA-MB-231 cells (d) and MCF7/TamR cells (e). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

(e) . Inhibition of MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 promotes Doc to suppress malignant progression of tumour cells

Given the fact that inhibiting PADI2 enzymatic activity enhances the anti-tumour effect of docetaxel in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells [31], we wondered whether blocking the function of MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 can promote the anti-tumour effect of Doc in the other tumour cells. To test this hypothesis, we first transfected the four tumour cells with anti-Cit189 antibody, and then performed immunofluorescence analysis in these cells and validated the successful antibody transfection efficiency (figure 5a). The blocking treatment significantly decreased the viability of cells to the similar level as that of BB-Cla treatment. Combined treatment with anti-Cit189 antibody transfection and Doc further reduced the cell viability (figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of MEK1 citrullination at Arg189 promotes Doc to suppress malignant progression of tumour cells. (a) After the anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody transfection into cells, Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody was used to detect the transfection efficiency. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Bar = 20 µm. (b) Relative cell viability analysis using CCK-8 detection kit. n = 3, *p < 0.05. (c) Schematic presentation for generating Docetaxel-resistant (DocR) or Cisplatin-resistance (CisR) ISI cells. (d–f) Relative cell viability with CCK8 assay in ISI DocR cells (top) or ISI CisR cells (bottom) under 100 nM Doc or 5 µM Cis treatment (d), 100 nM Doc combined with 20 µM BB-Cla or 5 µM Cis combined with 20 µM BB-Cla (e), 100 nM Doc combined with anti-MEK1 189 antibody or 5 µM Cis combined with anti-MEK1 189 antibody (f). n = 3, *p < 0.05. (Online version in colour.)

In the process of tumour chemotherapy and its acquired drug resistance, it is also accompanied by disorder of the intracellular ERK signalling pathway, which further leads to the activation of tumour stemness characteristics [53–55]. Given that BB-Cla can increase the efficacy of the Doc against tumour cells, we wondered whether inhibiting MEK1 Cit189 may also play a protective role in chemotherapy-resistant tumour cells. We first constructed Doc-resistant (DocR) or Cisplatin-resistant (CisR) ISI tumour cells (figure 5c). As shown in figure 5d, after six months of drug screening, DocR (100 nM Doc) or CisR (5 µM Cis) ISI cells were successfully constructed (figure 5d). We then treated these two chemotherapy-resistant cell lines with BB-Cla, and the results showed that BB-Cla could significantly reduce the cell viability of drug-resistant cells in the presence of Doc or Cis (figure 5e). To determine whether BB-Cla restores the chemosensitivity of tumour cells by affecting MEK1 citrullination, we again transfected tumour cells with the anti-Cit189 antibody. Results showed that the viability of drug-resistant cells was significantly reduced upon the anti-MEK1 Cit189 antibody transfection (figure 5f). Together, inhibiting MEK1 Cit189 modification can partially restore the sensitivity of chemotherapy-resistant cells to docetaxel or cisplatin in PADIs-expressed tumour cells, at least with PADI2 expression.

4. Discussion

Previously, we found that inhibiting PADI2 enzyme activity with Cl-amine increases the efficacy of docetaxel on MCF7/TamR cells with PADI2 expression [31]. However, it was not clear whether this effect applies to other tumour cells with PADIs expression. Here, we collected four tumour cells with different PADIs expression and fully evaluated the inhibitory effect of the combination of BB-Cla and Doc in vitro and in vivo on tumour cell growth. Our results showing that inhibiting PADIs combined with docetaxel additively inhibits tumour cell growth across the four tumour cells strongly suggest that this combined strategy is applicable to a variety of tumour treatments with PADIs expression, not only limited to MCF7/TamR cells.

Accumulated reports including ours have identified citrullination as a novel protein PTM on a couple of non-histone proteins that can affect the malignant progression of tumours, such as the ability of angiogenesis and metastasis [29,30,37,56]. Recently, we showed that inhibiting PADI2 enzymatic activity increases the efficacy of docetaxel on MCF7/TamR cells, indicating that it is probably the protein citrullination in tumour cells that helps enhance the tumour-killing effect of docetaxel [31]. We further provided evidence showing in endometrial carcinoma cells that MEK1 citrullination at R189 is involved in regulating the malignancy of cancer cells with PADI2 expression. Inhibiting conversion of MEK1 arginine 189 to citrulline compromises MEK1 kinase activity, which prevents the activation of the MEK1/ERK signalling axis in tumour cells [29]. The MEK1–ERK signalling cascade is a classic signal transduction module in cells and plays an important role in various disease processes. Abnormal activation of this pathway is one of the most important oncogenic drivers of human tumours [57,58]. As an important part of the MEK1–ERK signalling cascade, MEK1 is phosphorylated and activated by upstream RAF kinases, and then specifically catalyses the phosphorylation of the downstream ERK [58,59]. Therefore, this critical cross-over position of MEK1 makes it an attractive anti-tumour target for the treatment of various tumours [60]. In the process of chemotherapy and its acquired drug resistance, disorder of the intracellular ERK signalling pathway is frequently observed across a variety of tumour types, leading to the activation of tumour stemness characteristics, including colorectal cancer [55], pancreatic cancer [61], melanoma [62], prostate cancer cells [63] and ovarian cancer [64]. Our study showing that MEK1 Cit189 also exists in the four tumour cells, and that blocking the function of MEK1 Cit189 promotes the anti-tumour effect of Doc in tumour cells, greatly expands the possibility of establishing MEK1 Cit189 as a potential therapeutic target for multiple tumours. Of note, citrullination at MEK1 Arg189 is probably PADI2-dependent in these cells, as we have previously shown that PADI1 overexpression does not increase the level of MEK1 Cit189 [29]. Additionally, knocking down PADI1 or PADI4 in MCF7/TamR cells does not affect MEK1 Cit189 (electronic supplementary material, figure S3g,h). As a pan PADI inhibitor, BB-Cla may inhibit PADI1 in MDA-MB-231 cells, or PADI4 in HCT-116 cells, through a different mechanism independent of MEK1 Cit189.

The expression level of tumour stemness factors can reflect the malignancy of tumour cells to a certain extent [65–68]. We previously showed that inhibiting MEK1 R189 citrullination reduces the expression of stemness factor SOX2 in endometrial carcinoma cells [29]. Additionally, we found that MEK1 citrullination at R189 catalysed by PADI2 increases the malignancy of endometrial cancer cells [29]. Here, we again validated across the four tumour cells that inhibiting MEK1 Cit189 decreases the expression of cancer cell stemness factors and helps prevent cancer cell stemness maintenance. Docetaxel alone can reduce the expression of cancer cell stemness factors, and inhibit the malignancy of tumour stem cells [69]. On the basis of that, inhibiting MEK1 Cit189 combined with Doc seems to achieve an additive anti-tumour effect on the four tumour cells, as the combined treatment accumulatively reduces the expression of these tumour stemness factors, and partially restores the sensitivity of chemotherapy-resistant cells to docetaxel or cisplatin in PADIs-expressed tumour cells, at least with PADI2 expression. Together, our work may help establish a therapeutic feasibility using docetaxel combination with PADIs inhibitors in tumour treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged the technical support for antibody transfection from Prof. Lizeng Gao, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academic of Science.

Ethics

This work did not require ethical approval from a human subject or animal welfare committee.

Data accessibility

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [70].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors' contributions

T.X.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft; S.F.: data curation, methodology; J.G.: investigation, methodology; N.L.: investigation, methodology; P.Z.: data curation, investigation; X.L.: methodology; P.R.T.: resources; X.Z.: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 82172945 and 82203869); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2022M711679) and Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (grant no. 2022ZB421).

References

- 1.Sheng D, et al. 2022. Ccl3 enhances docetaxel chemosensitivity in breast cancer by triggering proinflammatory macrophage polarization. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e003793. ( 10.1136/jitc-2021-003793) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Z, et al. 2022. Docetaxel remodels prostate cancer immune microenvironment and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Theranostics 12, 4965-4979. ( 10.7150/thno.73152) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabholtz JM, et al. 2001. Phase II study of docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 314-321. ( 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.314) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei G, Wang Y, Yang G, Wang Y, Ju R. 2021. Recent progress in nanomedicine for enhanced cancer chemotherapy. Theranostics 11, 6370-6392. ( 10.7150/thno.57828) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nouman M, et al. 2020. Response rate of cisplatin plus docetaxel as primary treatment in locally advanced head and neck carcinoma (squamous cell types). Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 21, 825-830. ( 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.3.825) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Guo S, Wang S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Wang Y, Liu R, Niu Y, Xu Y. 2022. EIF4A3-induced circARHGAP29 promotes aerobic glycolysis in docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer through IGF2BP2/c-Myc/LDHA signaling. Cancer Res. 82, 831-845. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-2988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, et al. 2022. Docetaxel resistance-derived LINC01085 contributes to the immunotherapy of hormone-independent prostate cancer by activating the STING/MAVS signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 545, 215829. ( 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215829) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves CL, et al. 2021. Co-targeting CDK4/6 and AKT with endocrine therapy prevents progression in CDK4/6 inhibitor and endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 5112. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-25422-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Q, Min S, Zhou Y. 2022. A network meta-analysis for efficacies and toxicities of different concurrent chemoradiotherapy regimens in the treatment of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 22, 674. ( 10.1186/s12885-022-09717-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith ER, Huang M, Schlumbrecht MP, George SHL, Xu XX. 2022. Rationale for combination of paclitaxel and CDK4/6 inhibitor in ovarian cancer therapy—non-mitotic mechanisms of paclitaxel. Front. Oncol. 12, 907520. ( 10.3389/fonc.2022.907520) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Nardo P, Lisanti C, Garutti M, Buriolla S, Alberti M, Mazzeo R, Puglisi F. 2022. Chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer: clinical overview and management of long-term side effects. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 21, 1341-1355. ( 10.1080/14740338.2022.2151584) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elm'hadi C, Tanz R, Khmamouche MR, Toreis M, Mahfoud T, Slimani KA, Errihani H, Ichou M. 2016. Toxicities of docetaxel: original drug versus generics—a comparative study about 81 cases. Springerplus 5, 732. ( 10.1186/s40064-016-2351-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CH, Han SE, Nam-Goong IS, Kim YI, Kim ES. 2018. Combined effects of baicalein and docetaxel on apoptosis in 8505c anaplastic thyroid cancer cells via downregulation of the ERK and Akt/mTOR pathways. Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 121-132. ( 10.3803/EnM.2018.33.1.121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu YK, Wang BJ, Tseng JC, Huang SH, Lin CY, Kuo YY, Hour TC, Chuu CP. 2022. Combination treatment of docetaxel with caffeic acid phenethyl ester suppresses the survival and the proliferation of docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer cells via induction of apoptosis and metabolism interference. J. Biomed. Sci. 29, 16. ( 10.1186/s12929-022-00797-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Liu S, Tao Y. 2020. Regulating tumor suppressor genes: post-translational modifications. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 90. ( 10.1038/s41392-020-0196-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Qian C, Cao X. 2016. Post-translational modification control of innate immunity. Immunity 45, 15-30. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surka C, et al. 2021. CC-90009, a novel cereblon E3 ligase modulator, targets acute myeloid leukemia blasts and leukemia stem cells. Blood 137, 661-677. ( 10.1182/blood.2020008676) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou C, et al. 2020. N6-methyladenosine modification of the TRIM7 positively regulates tumorigenesis and chemoresistance in osteosarcoma through ubiquitination of BRMS1. EBioMedicine 59, 102955. ( 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102955) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jing C, et al. 2021. Blockade of deubiquitinating enzyme PSMD14 overcomes chemoresistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by antagonizing E2F1/Akt/SOX2-mediated stemness. Theranostics 11, 2655-2669. ( 10.7150/thno.48375) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salguero AL, et al. 2022. Multifaceted regulation of Akt by diverse C-terminal post-translational modifications. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 68-76. ( 10.1021/acschembio.1c00632) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zecha J, Gabriel W, Spallek R, Chang YC, Mergner J, Wilhelm M, Bassermann F, Kuster B. 2022. Linking post-translational modifications and protein turnover by site-resolved protein turnover profiling. Nat. Commun. 13, 165. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-27639-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manni W, Jianxin X, Weiqi H, Siyuan C, Huashan S. 2022. JMJD family proteins in cancer and inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 304. ( 10.1038/s41392-022-01145-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu G, Jin L, Sun W, Wang S, Liu N. 2022. Proteomics of post-translational modifications in colorectal cancer: discovery of new biomarkers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1877, 188735. ( 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188735) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng Y, Liu J, Inuzuka H, Wei W. 2023. Targeted protein posttranslational modifications by chemically induced proximity for cancer therapy. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 104572. ( 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104572) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuzhalin AE. 2019. Citrullination in cancer. Cancer Res. 79, 1274-1284. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2797) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katayama H, et al. 2021. Protein citrullination as a source of cancer neoantigens. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, e002549. ( 10.1136/jitc-2021-002549) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vossenaar ER, Zendman AJ, van Venrooij WJ, Pruijn GJ. 2003. PAD, a growing family of citrullinating enzymes: genes, features and involvement in disease. Bioessays 25, 1106-1118. ( 10.1002/bies.10357) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raijmakers R, et al. 2007. Methylation of arginine residues interferes with citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminases in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 1118-1129. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.054) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue T, et al. 2021. PADI2-catalyzed MEK1 citrullination activates ERK1/2 and promotes IGF2BP1-mediated SOX2 mRNA stability in endometrial cancer. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002831. ( 10.1002/advs.202002831) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin H, et al. 2017. PAD1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer cells by regulating MEK1-ERK1/2-MMP2 signaling. Cancer Lett. 409, 30-41. ( 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.08.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li F, Miao L, Xue T, Qin H, Mondal S, Thompson PR, Coonrod SA, Liu X, Zhang X. 2019. Inhibiting PAD2 enhances the anti-tumor effect of docetaxel in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 414. ( 10.1186/s13046-019-1404-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang X, Han J. 2006. Expression of peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 (PAD4) in various tumors. Mol. Carcinog. 45, 183-196. ( 10.1002/mc.20169) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang X, Han J, Pang L, Zhao Y, Yang Y, Shen Z. 2009. Increased PADI4 expression in blood and tissues of patients with malignant tumors. BMC Cancer 9, 40. ( 10.1186/1471-2407-9-40) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moshkovich N, Ochoa HJ, Tang B, Yang HH, Yang Y, Huang J, Lee MP, Wakefield LM. 2020. Peptidylarginine deiminase IV regulates breast cancer stem cells via a novel tumor cell-autonomous suppressor role. Cancer Res. 80, 2125-2137. ( 10.1158/0008-5472) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi L, Yao H, Liu Z, Xu M, Tsung A, Wang Y. 2020. Endogenous PAD4 in breast cancer cells mediates cancer extracellular chromatin network formation and promotes lung metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 18, 735-747. ( 10.1158/1541-7786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H, Xu B, Zhang X, Zheng Y, Zhao Y, Chang X. 2016. PADI2 gene confers susceptibility to breast cancer and plays tumorigenic role via ACSL4, BINC3 and CA9 signaling. Cancer Cell Int. 16, 61. ( 10.1186/s12935-016-0335-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuzhalin AE, et al. 2018. Colorectal cancer liver metastatic growth depends on PAD4-driven citrullination of the extracellular matrix. Nat. Commun. 9, 4783. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-07306-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, et al. 2017. PADI2-mediated citrullination promotes prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 77, 5755-5768. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0150) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones JE, Slack JL, Fang P, Zhang X, Subramanian V, Causey CP, Coonrod SA, Guo M, Thompson PR. 2012. Synthesis and screening of a haloacetamidine containing library to identify PAD4 selective inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 160-165. ( 10.1021/cb200258q) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, et al. 2012. Anticancer peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) inhibitors regulate the autophagy flux and the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25 941-25 953. ( 10.1074/jbc.M112.375725) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun MY, Zhu JY, Zhang CY, Zhang M, Song YN, Rahman K, Zhang LJ, Zhang H. 2017. Autophagy regulated by lncRNA HOTAIR contributes to the cisplatin-induced resistance in endometrial cancer cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 39, 1477-1484. ( 10.1007/s10529-017-2392-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong C, Zhu Z, Li Y, Xue P, Chen L. 2021. Downregulation of HOXA11 enhances endometrial cancer malignancy and cisplatin resistance via activating PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 23, 1334-1341. ( 10.1007/s12094-020-02520-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Funayama R, Taniguchi H, Mizuma M, Fujishima F, Kobayashi M, Ohnuma S, Unno M, Nakayama K. 2017. Protein-arginine deiminase 2 suppresses proliferation of colon cancer cells through protein citrullination. Cancer Sci. 108, 713-718. ( 10.1111/cas.13179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chai Z, et al. 2019. PADI3 plays an antitumor role via the Hsp90/CKS1 pathway in colon cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 19, 277. ( 10.1186/s12935-019-0999-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang X, Chai Z, Zou J, Wang H, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Wu H, Liu C. 2019. PADI3 induces cell cycle arrest via the Sirt2/AKT/p21 pathway and acts as a tumor suppressor gene in colon cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 16, 729-742. ( 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2019.0065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang YR, Zhang L, Li F, He JS, Xuan JF, Chen CC, Gong C, Pan YL. 2022. PADI1 and its co-expressed gene signature unveil colorectal cancer prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy. J. Oncol. 2022, 8394816. ( 10.1155/2022/8394816) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song S, Gui L, Feng Q, Taledaohan A, Li Y, Wang W, Wang Y, Wang Y. 2020. TAT-modified gold nanoparticles enhance the antitumor activity of PAD4 inhibitors. Int. J. Nanomed. 15, 6659-6671. ( 10.2147/IJN.S255546) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. 2008. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat. Genet. 40, 499-507. ( 10.1038/ng.127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hassan KA, Chen G, Kalemkerian GP, Wicha MS, Beer DG. 2009. An embryonic stem cell-like signature identifies poorly differentiated lung adenocarcinoma but not squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6386-6390. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouyang S, Zhou X, Chen Z, Wang M, Zheng X, Xie M. 2019. LncRNA BCAR4, targeting to miR-665/STAT3 signaling, maintains cancer stem cells stemness and promotes tumorigenicity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 19, 72. ( 10.1186/s12935-019-0784-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu Q, et al. 2022. microRNA-497 prevents pancreatic cancer stem cell gemcitabine resistance, migration, and invasion by directly targeting nuclear factor kappa B 1. Aging 14, 5908-5924. ( 10.18632/aging.204193) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chong KH, Chang YJ, Hsu WH, Tu YT, Chen YR, Lee MC, Tsai KW. 2022. Breast cancer with increased drug resistance, invasion ability, and cancer stem cell properties through metabolism reprogramming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 12875. ( 10.3390/ijms232112875) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jang TH, et al. 2022. MicroRNA-485-5p targets keratin 17 to regulate oral cancer stemness and chemoresistance via the integrin/FAK/Src/ERK/β-catenin pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 29, 42. ( 10.1186/s12929-022-00824-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng W, Gao M, Yang M, Li X, Gan Z, Wu T, Lin Y, He T. 2022. TNFAIP3 promotes ALDH-positive breast cancer stem cells through FGFR1/MEK/ERK pathway. Med. Oncol. 39, 230. ( 10.1007/s12032-022-01844-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei F, et al. 2019. PD-L1 promotes colorectal cancer stem cell expansion by activating HMGA1-dependent signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 450, 1-13. ( 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, et al. 2021. Histone citrullination by PADI4 is required for HIF-dependent transcriptional responses to hypoxia and tumor vascularization. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe3771. ( 10.1126/sciadv.abe3771) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drosten M, Barbacid M. 2020. Targeting the MAPK pathway in KRAS-driven tumors. Cancer Cell 37, 543-550. ( 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aikin TJ, Peterson AF, Pokrass MJ, Clark HR, Regot S. 2020. MAPK activity dynamics regulate non-cell autonomous effects of oncogene expression. Elife 9, e60541. ( 10.7554/eLife.60541) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan M, Templeton DJ. 1994. Identification of 2 serine residues of MEK-1 that are differentially phosphorylated during activation by raf and MEK kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19 067-19 073. ( 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32275-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seo G, Han H, Vargas RE, Yang B, Li X, Wang W. 2020. MAP4K interactome reveals STRN4 as a key STRIPAK complex component in hippo pathway regulation. Cell Rep. 32, 107860. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107860) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaushik G, et al. 2021. Selective inhibition of stemness through EGFR/FOXA2/SOX9 axis reduces pancreatic cancer metastasis. Oncogene 40, 848-862. ( 10.1038/s41388-020-01564-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li S, et al. 2019. Transcriptional regulation of autophagy-lysosomal function in BRAF-driven melanoma progression and chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 10, 1693. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-09634-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zelivianski S, et al. 2003. ERK inhibitor PD98059 enhances docetaxel-induced apoptosis of androgen-independent human prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 107, 478-485. ( 10.1002/ijc.11413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitra T, Prasad P, Mukherjee P, Chaudhuri SR, Chatterji U, Roy SS. 2018. Stemness and chemoresistance are imparted to the OC cells through TGFβ1 driven EMT. J. Cell. Biochem. 119, 5775-5787. ( 10.1002/jcb.26753) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie H, Yao J, Wang Y, Ni B. 2022. Exosome-transmitted circVMP1 facilitates the progression and cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting miR-524-5p-METTL3/SOX2 axis. Drug Deliv. 29, 1257-1271. ( 10.1080/10717544.2022.2057617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soleimani A, Dadjoo P, Avan A, Soleimanpour S, Rajabian M, Ferns G, Ryzhikov M, Khazaei M, Hassanian SM. 2022. Emerging roles of CD133 in the treatment of gastric cancer, a novel stem cell biomarker and beyond. Life Sci. 293, 120050. ( 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou L, Sun Y, Ye G, Zhao Y, Wu J. 2022. Effects of CD133 expression on chemotherapy and drug sensitivity of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 25, 18. ( 10.3892/mmr.2021.12534) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al-Kaabi M, Noel K, Al-Rubai AJ. 2022. Evaluation of immunohistochemical expression of stem cell markers (NANOG and CD133) in normal, hyperplastic, and malignant endometrium. J. Med. Life 15, 117-123. ( 10.25122/jml-2021-0206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang X, Shao J, Li X, Cui L, Tan Z. 2019. Docetaxel promotes cell apoptosis and decreases SOX2 expression in CD133-expressing hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells by suppressing the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 41, 1067-1074. ( 10.3892/or.2018.6891) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xue T, Fei S, Gu J, Li N, Zhang P, Liu X, Thompson PR, Zhang X. 2023. Inhibiting MEK1 R189 citrullination enhances the chemosensitivity of docetaxel to multiple tumor cells. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6806579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [70].