Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this article is to present conceptual and methodological challenges to recruitment strategies in enrolling socially disconnected middle-aged and older Latino caregivers of a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).

Methods:

Middle-aged and older Latino ADRD caregivers were recruited into two early stage, intervention development studies during the COVID-19 pandemic via online or in-person methods. Recruitment criteria included Latino ADRD caregivers over the age of 40 reporting elevated loneliness on the UCLA 3-item Loneliness Scale (LS) during screening.

Results:

Middle-aged, Latino caregivers were recruited predominantly from online methods whereas older caregivers were mostly recruited from in-person methods. We report challenges identifying socially disconnected Latino caregivers using the UCLA 3-item LS.

Conclusions:

Our findings support previously reported disparities in recruitment by age and language and suggest further methodological considerations to assess social disconnection among Latino caregivers. We discuss recommendations to overcome these challenges in future research.

Clinical Implications:

Socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers have an elevated risk for poor mental health outcomes. Successful recruitment of this population in clinical research will ensure the development of targeted and culturally sensitive interventions to improve the mental health and overall well-being of this marginalized group.

Keywords: Latinos, caregivers, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia, social disconnection, health disparities, recruitment

Latinos1 in the U.S. are expected to have the greatest increase in diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the next 40 years (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Matthews et al., 2019). Higher rates of risk factors including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome contribute to the elevated dementia rates among older Latinos (Chin et al., 2011). Despite these risk factors, Latinos with dementia live longer with the disease than non-Hispanic Whites (Mayeda et al., 2017), which prolongs the care provided by family caregivers. Longer survival after a dementia diagnosis among Latinos may be attributed, in part, to the prolonged care facilitated by family caregivers given that Latinos with dementia are less likely to be placed in nursing homes (Mayeda et al., 2017). Compared to nursing home placements, in-home care is often associated with better morale and well-being among the person with ADRD (Miguel et al., 2016; Olsen et al. 2016), which facilitates survival.

In addition, Latinos also have the highest prevalence of dementia caregiving compared to other racial/ethnic groups and, consequently, are more likely to experience greater caregiver burden (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2016). Despite their family-centric culture, many Latino caregivers report inconsistent support from family, as well as less support from health care systems, and greater health decline and barriers to using dementia care resources (Balbim et al., 2020). These burdens place Latino caregivers at risk for social disconnection – a dimension of social and mental health encompassing loneliness (distressing emotional experience of lacking a desired level of social connection), social isolation (lack of social contacts), and perceived low social support (functions that relationships provide) (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017) – thus, increasing the likelihood of experiencing poor mental health outcomes. Indeed, compared to other racial/ethnic ADRD caregivers, Latino caregivers show worse psychological outcomes, including higher levels of depression and distress (Adams et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2021; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005; Sörensen & Pinquart, 2005), leading Latino caregivers to potentially become and stay socially disconnected via bi-directional influences (Santini et al., 2020).

Across race/ethnicity groups, caregiving for a person with ADRD has been linked to social disconnection (Van Orden & Heffner, 2022). The effects of social disconnection coupled with the chronic stress and burden inherent to caregiving may increase caregivers’ risk for physical and mental illness (Kovaleva et al., 2021; Xian & Xu, 2020). Within studies of social and mental health among Latino caregivers, social support is the most studied dimension of social connection (Llanque & Enriquez, 2012; Rote et al., 2019); however, it is unknown how facets of social disconnection, such as loneliness and social isolation, affect Latino caregivers. Without a comprehensive understanding of social disconnection among Latino caregivers, it is unclear whether and how social connection interventions should be culturally adapted to promote Latino ADRD caregiver mental health outcomes, or how to develop clinical research on social connection that is culturally relevant and engages Latino caregivers.

Older Latinos face many social and systemic barriers that preclude them from engaging in clinical research. This includes unique barriers faced by older Latino ADRD caregivers that perpetuate social disconnection. One important challenge, among older Latinos, is the ability to fluently communicate with the research team (George et al., 2014). Approximately 50% of U.S. older Latinos speak predominantly Spanish (Center, 2013), with some preferring indigenous languages. This language barrier also affects access to dementia care services (Holton, 2017), including information provided by agencies that offer services for ADRD, thus perpetuating lack of support among Latino caregivers. Other significant barriers to participation in research include stigma and mistrust in the existing medical system, including dementia health care, low levels of health literacy, lack of health care or disease-related information, limited transportation, and researchers’ lack of cultural humility (Diaz Rios & Chapman-Novakofski, 2018; Lee et al., 2022; McGregor et al., 2019; Vega et al., 2017). Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic shone a light on these already existing barriers to research engagement for older Latinos, and for marginalized communities in general, highlighting the entrenched inequities in healthcare and research among the Latino population. One important aspect to note is the heterogeneity of the Latino population, with individuals from various regions including Central and South America and the Caribbean (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003). Latinos from these regions differ significantly, and their unique life experiences can influence their social integration to their surrounding environment. Despite the considerable heterogeneity, Latinos do share core cultural values, including familismo (placing family needs over individual needs), personalismo (emphasis on personal interactions), and respeto (respect based on a hierarchical structure), which shape Latino individuals’ responses to healthcare systems in general and to ADRD care, in particular (Adames et al., 2014; Savage et al., 2016), and likely their overall motivation to engage in ADRD research. For example, familismo can affect health care perceptions, the utilization of health care services, and health care decision-making processes within the family (Savage et al., 2016). Cultural values may also influence ADRD caregivers’ expectations about their own social roles and those of others within their networks (Balbim et al., 2019; Rodriguez & Padilla-Martinez, 2020) and, importantly, may predict social isolation and loneliness among older caregivers (Garcia Diaz et al., 2019). For some caregivers, for example, familismo may complicate their experience of caregiving because of the unmet expectation of family support, leading to increased stress and social disconnection (Mendez-Luck et al., 2016; Rosenthal German, 2014).

To address the underrepresentation of older Latinos, particularly socially disconnected Latino caregivers, researchers must adjust commonly utilized recruitment strategies and procedures. Previous work on dementia and dementia care with Latinos suggests active strategies including, but not limited to, building trust and fostering meaningful relationships with the Latino community, partnering with established organizations serving Latinos, providing culturally appropriate outreach, and diversifying research teams (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003; National Academies of Science, 2021; Quiroz et al., 2022). These strategies are consistent with those suggested for recruitment of Latinos during the COVID-19 pandemic, including considerations for virtual recruitment approaches (Cortes et al., 2022; Gutierrez et al. 2022). Further, a recent review suggested that the most promising strategy to recruit socially isolated and lonely older adults was referrals by recognized agencies (Ige et al., 2019).

Success of recruitment and enrollment is also affected by the selection of measures used to assess eligibility. Although most studies recruiting socially disconnected older adults have not consistently used standardized tools for defining social isolation or loneliness (Ige et al., 2019), some have relied on the UCLA 3-item Loneliness Scale to measure and identify these dimensions of social disconnection among older adults (Clifton et al., 2022; Crowe et al., 2021; Georgia Health Policy Center, 2020; Van Orden et al., 2022). When considering the adoption of this measure to recruit socially disconnected Latino caregivers, researchers must ensure that the measure appropriately captures the construct of social disconnection in this population. Indicators of social disconnection may be reflected differently in Latino caregivers relative to other racial/ethnic groups. Thus, utilizing the same tools employed with other groups to measure or identify aspects of social disconnection in Latino caregivers may not yield successful engagement in research. Addressing recruitment challenges early in the research process can inform future development and implementation of behavioral interventions (Onken et al., 2014) for Latino ADRD caregivers.

The objective of this article is to (1) present the efforts and challenges of our group to identify and recruit socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers into research, and (2) provide guidance from our lessons learned to foster advancement of social connection research and intervention development with Latino caregivers. The research was supported by infrastructure developed by the Hispanic/Latino Engagement sub-Core (HLESC) of the National Institute on Aging (NIA)-funded Rochester Roybal Center for Social Ties & Aging Research, in collaboration with community partners. Here, we describe approaches to identifying and recruiting lonely Latino caregivers for two early stage, intervention development studies funded by the Roybal Center during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also present key conceptual and methodological issues that arose in the conduct of our social connection research with Latinos that compelled modifications to ongoing recruitment and considerations of future directions in research.

Methods

The HLESC developed an infrastructure to establish and maintain partnerships with local community agencies and clinics that serve Latinos. In the following section, we provide an overview of our developed infrastructure as well as additional in-person and online approaches to recruit socially disconnected Latino caregivers for two early stage, development studies.

Overview of Early Stage, Social Connection Intervention Development Studies

Latino caregivers were recruited simultaneously for two studies that aimed to identify whether and how to culturally adapt behavioral interventions to improve social connectedness. Study 1 was a qualitative study targeting recruitment of 20 socially disconnected and 5 socially connected caregivers. Interviews were conducted to explore both facilitators and barriers to social connection among Latino caregivers who were experiencing social disconnection and those who were experiencing social connection. Study 2 was an early-stage clinical trial of a behavioral intervention testing behavioral strategies to improve social connection among socially disconnected Latino caregivers. The sample size goal for this clinical trial was 10 socially disconnected caregivers. All procedures for both studies were completed via Zoom and participants had the option to use either a computer, tablet or phone. Both studies were approved by the University of Rochester Medical Center Research Subject Review Board.

The Sample: Eligibility Criteria

Our key eligibility screening tool for social disconnection/connection was the UCLA 3-item Loneliness Scale (LS). The UCLA 3-item measures subjective feelings of loneliness, a dimension of social disconnection, and contains statements from its longer version, the UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3 (UCLA LS-20) (Russell, 1996) (“I lack companionship,” “I feel left out,” and “I feel isolated from others”). The scale is rated on a three-point Likert scale (hardly ever/never, some of the time, and often). At study start, caregivers were deemed eligible for participation based on scores from the UCLA 3-item LS, with social disconnection defined as a total score ≥ 6. Social connection was indicated by scores < 6 (Steptoe et al., 2013).

Additional inclusion criteria were: identified as Latino/a (English or Spanish speaking); caring for a loved one with ADRD; aged 40 years or older; endorsed elevated global or caregiving stress (Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) (Cohen et al., 1983) >11 or Modified Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) (Thornton, 2003) >5); no evidence of current alcohol or substance abuse, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features (MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview) (Sheehan et al., 1998), no evidence of cognitive impairment (Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) (Brandt et al., 1988) > 25), and able to provide informed consent to participate in the studies.

Recruitment Strategies

Fostering Community and Clinical Partnerships

The HLESC is comprised of an interdisciplinary team of investigators and research staff with complementary strengths in Latinos’ mental health and cognitive aging. Team members are fluent in both Spanish and English, thus ensuring capability to communicate with Latinos. The HLESC’s approach to engage socially disconnected Latino caregivers draws from previous work in Latinos’ dementia care (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 1997; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2004; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003; Montoro-Rodriguez & Gallager-Thompson, 2020) and community engagement frameworks (McCloskey et al., 2011; Programme, 2008), and centers around fostering partnerships with local community leaders and employing diverse research and recruitment approaches.

Establishing and fostering community partnerships is central to community engagement in research (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010; Organizing Committee for Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement in Health & Health Care Programs & Policies, 2022). A key HLESC community partner is the Ibero-American Action League; the largest nonprofit dual language multi-service community agency for Latinos in Monroe County, New York, a county region comprising metropolitan, suburban, and rural communities totaling approximately 67,600 Hispanic/Latino residents. Ibero houses Centro de Oro (Gold Center), which provides services to older Latinos over the age of 60. The center was identified by members of the HLESC interested in community-engaged research with a drive to provide community outreach and increase mental and cognitive health awareness in the Latino community. The strength of this partnership lies within its collaborative nature. Ibero leaders and HLESC members jointly identified the needs of the community served at the senior center and created opportunities to address these needs, including providing educational outreach. The outreach initiative comprises education about cognitive and mental health provided to older Latinos at Centro de Oro, including education about caregivers’ mental and social well-being. To expand and maintain these collaborations, Ibero’s President and CEO was asked to serve on the Roybal Center’s Advisory Committee and, together with Ibero’s Director of Elder Services, serves as a liaison to the Monroe County Latino community.

The Roybal Center has also forged strong collaborations with the Alzheimer’s Association Rochester and Finger Lakes Region Chapter. The local Alzheimer’s Association chapter was identified as a potential partner due to the services they provide for dementia care and caregiver support, including services for Latino families. The collaboration capitalizes on the association’s priority to establish closer connections with - and expand their services to - the Latino community. Therefore, as part of the collaboration, HLESC members provide study participants with information about the Alzheimer’s Association to raise awareness of the multiple resources currently available to Latinos. In turn, the Alzheimer’s Association disseminates research opportunities from studies funded through the Roybal Center recruiting socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers. Other partnerships include community clinics serving Latinos: Lazos Fuertes, a URMC Spanish-language outpatient behavioral health clinic; the University of Rochester Medicine Spanish Language Neurology Clinic; UR Medicine Memory Care Program. These programs provide specialized and culturally oriented care to Latinos. HLESC and Roybal Center members have strong ties to these clinics through prior collaborations or clinical services they provide at these clinics. The Medical Director of the Spanish Language Neurology Clinic and the Clinical Director of the Memory Care Program are members of the Center’s Steering Committee and aid with recruitment efforts. There is a strong appreciation for culturally attuned research with Latinos among clinical leadership and staff, which has been integral to our Center’s goals.

These community and clinical partnerships ensure that the HLESC’s recruitment efforts are continually informed by Latino community members or individuals working closely with Latino caregivers. It is important to note that establishing these partnerships takes time (Dennis et al., 2015). Community gatekeepers must trust that researchers care about their community. Thus, collaboratively developing common goals with the community and addressing the community’s needs can advance research and benefit the marginalized Latino caregiver community.

Online and On-Air Recruitment

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced many limitations to in-person recruitment. Thus, online recruitment became a widely used strategy to overcome social contact barriers to research participation (Mirza et al., 2022). Online recruitment for our studies was conducted from December 2020 through May 2022. Flyers with detailed information about our studies, including the purpose and study activities, were emailed to the local community organizations and clinics we had partnered with. Also, socially disconnected Latino caregivers were recruited from three online platforms: ResearchMatch, Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch, and the URMC Clinical Trials and Research Studies website. ResearchMatch (https://www.researchmatch.org/) is a non-profit program funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that connects people interested in research studies with researchers. Initially, individuals complete a short form with optional demographic and health questions. Researchers approved to access the platform can search non-identifiable volunteer data, identify possible matches, and send them an IRB-approved message about their study. Researchers also have the option to include an external link for further online eligibility screening. Regardless, potential participants receive the message via e-mail and, if interested, may provide permission for the research team to contact them (via phone or e-mail). Through the Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch (https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/research_progress/clinical-trials/trialmatch) and the URMC Clinical Trials and Research Studies websites, individuals can search for studies that are actively recruiting participants based on specific conditions (i.e., Alzheimer’s, dementia caregiving). Interested individuals can then complete a short form with contact information and preferences that is sent to study staff. The communication between researchers and potential participants via these online platforms is instantaneous. The two studies were also posted on social media, including private Facebook groups for Latinos in the region and the researchers’ Twitter accounts. In addition, information about our studies was disseminated to individuals attending the national and international Alzheimer’s Association Virtual Conference in Spanish. HLESC members also participated in a bilingual interview at Ibero’s radio station (Poder 97.1) regarding dementia care among Latinos and had the opportunity to describe the studies’ need to enroll socially disconnected Latino caregivers to the public.

In-Person Recruitment

Once COVID-19-related social distancing guidelines relaxed, HLESC members complemented online recruitment with in-person approaches. Nonetheless, community in-person contact was very limited, with small crowds of people congregating in public spaces given ongoing guidelines on social gatherings and pandemic-related fear. Our approach centered on the Latino value of personalismo following previous work with Latino caregivers suggesting that employing personalized recruitment strategies can help increase research participation (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2004). One strategy was to offer educational presentations on Latino caregiver health at Ibero’s Centro de Oro and to engage older adults in discussions regarding their experiences as caregivers (Evans et al., 2007). Our community partner at the Center identified Latino caregiver health as an area of need among the Center’s population. At the end of each presentation, HLESC members provided information about the two studies recruiting socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers, including the purpose and study activities, and offered the opportunity to participate. To further aid recruitment efforts, the senior center director personally identified and spoke with center-affiliated caregivers and connected the researchers with these individuals. Other recruitment efforts included posting our flyers at local Latino-owned food venues and businesses and at public housing developments’ community room spaces. HLESC members participate as non-profit vendors at the “La Marketa” (the International Plaza), a Latino-themed community gathering/event space and marketplace in the city of Rochester. Here, HLESC members regularly set up a table and engaged individuals in conversation about current Center-supported studies recruiting Latino caregivers who were feeling lonely and socially isolated. At the “Marketa,” Center members also connected with other vendors of locally-owned Latino businesses who agreed to distribute study-related materials at their shops. Additional community recruitment included tabling at health fairs focused on the health of marginalized communities. For our in-person recruitment, flyers were posted in local community venues beginning February 2021, and educational sessions and tabling events began May 2021. Recruitment was conducted until May 2022.

Results

Overall Screening and Enrollment Data

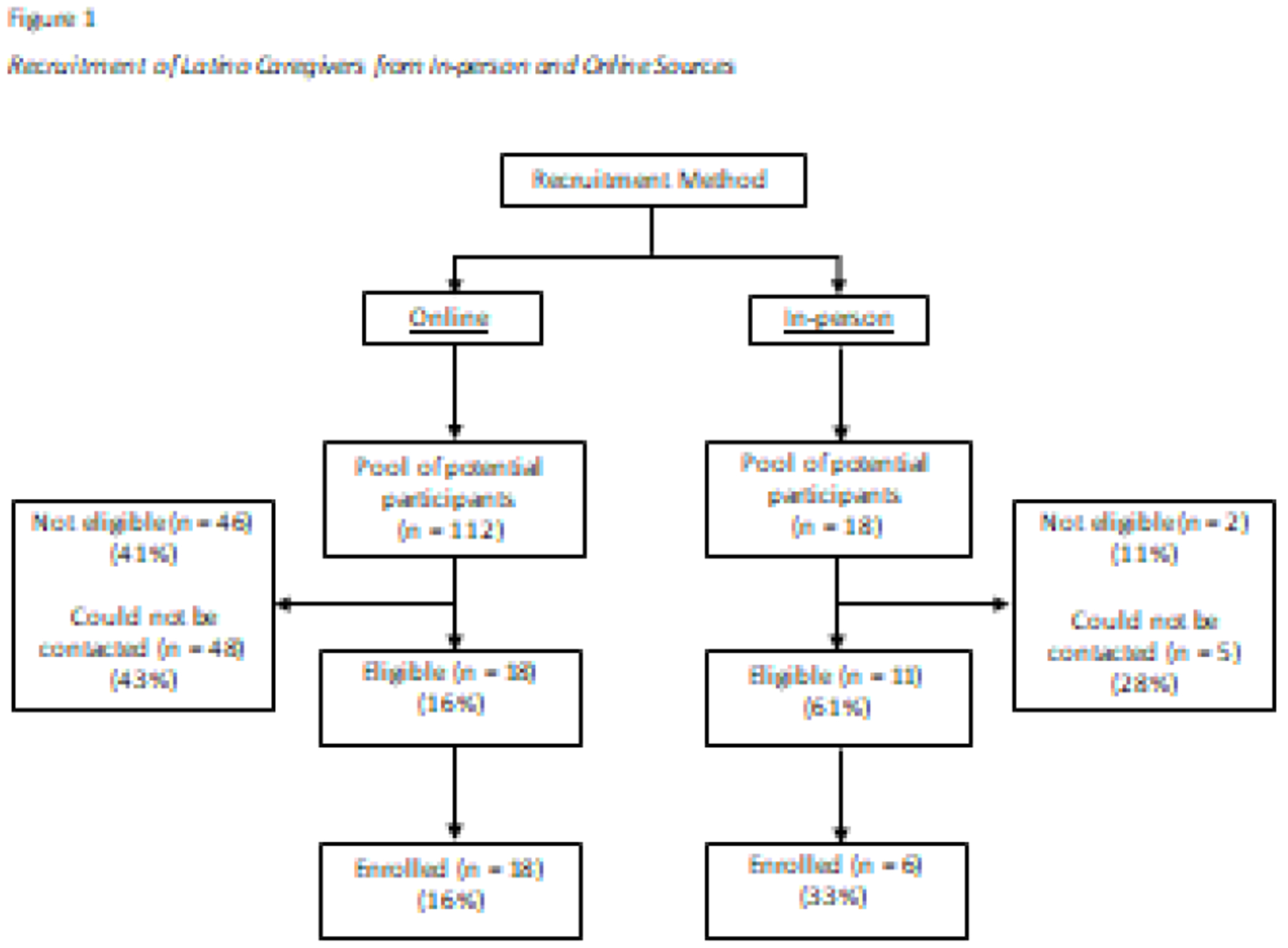

Figure 1 provides an overview of recruitment by source. Online recruitment resulted in a total of 112 potential participants (see left column of Figure 1). Recruitment through ResearchMatch yielded 102 interested participants who started an online screen, of which 41 were potentially eligible for our ongoing studies. The URMC Clinical Trials and Research Studies website yielded 5 potentially eligible participants. The Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch platform yielded 4 participants and their local Rochester and Finger Lakes Chapter webinars yielded 1 participant. Overall, from online sources, approximately 16% of interested individuals were eligible and enrolled in a study, 41% were not eligible, and 43% could not be contacted. Average age of individuals recruited from online sources with complete screens was 52.10 years. Only 20% of individuals recruited online with completed screens were mono-lingual Spanish speakers. Of those who completed further phone screening, about 66.6% had a college degree or higher.

Fig. 1.

Interested participants from in-person sources (n=18; see right column of Figure 1) were referred primarily via community organizations (i.e., Centro de Oro; n=10), medical providers (n=3), snowball sampling (n=4), and a community-posted flyer (n=1). Approximately 61% were eligible, from which 33.3% of the total interested participants enrolled in a study (those who did not enroll declined due to time limitations or lack of interest). Of total interested participants, about 11% (n=2) were not eligible and 28% (n=5) could not be contacted. Average age of individuals recruited from in-person sources was 61.44 years. About 28% of these individuals were mono-lingual Spanish speakers. Of those who completed the phone screening, 30.8% reported having a college degree or higher.

Thus, a total of 130 Latinos initially expressed interest in Center-related studies. The Center made (phone) contact with 69 Latinos, of which 24 enrolled in an ongoing study (overall 9% mono-lingual Spanish speakers). See Table 1 for a summary of demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics of Latino Caregivers from Online and In-person Sources

| Variable | Online | In-person |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.10 | 61.44 |

| Language | ||

| Spanish, monolingual | 20% | 28% |

| Education | ||

| Less than college degree | 33.4% | 69.2% |

| College degree or higher | 66.6% | 30.8% |

Screening Observations and Modification to the Indicator of Social Disconnection

At the start of study recruitment, caregivers were categorized as socially connected or socially disconnected according to their total score on the UCLA 3-item LS scale (as described above), which measures subjective feelings of loneliness, one of the dimensions of social disconnection. In Study 1, the aim was to understand both facilitators and barriers to social connection among Latino caregivers. Qualitative data was collected from both lonely and nonlonely caregivers to guide the potential adaptation of behavioral social connection interventions. After we met our recruitment target for socially connected caregivers (n=5; UCLA 3-item LS score 3-5), 33.33% of interested and subsequently screened caregivers continued to score below the identified loneliness cutoff (6) on the measure, and thus were not enrolled, posing a challenge to our goals to understand social disconnection in Latino caregivers.

To explore whether features of our screening measure might have contributed to low proportion of eligible caregivers, we evaluated scores and specific items endorsed on the 20-item UCLA LS version 3 (UCLA LS-20), which was completed by all enrolled participants in Study 1. This examination revealed that 10 (41.7%) caregivers who were identified as nonlonely on the UCLA 3-item LS met cutoff criteria for loneliness (≥ 28) (Lee et al., 2019) on the full UCLA LS-20. These caregivers endorsed items pertaining to other factors underpinning loneliness, such as relational conflict and subjective isolation, that were not represented in the UCLA 3-item LS short form (data not shown, manuscript in development). Based on these findings, recruitment criteria for the studies were changed. For Study 1, participants were no longer required to meet loneliness criteria from the UCLA 3-item LS. Instead, Latino caregivers who met all other criteria (i.e., family caregiver and caregiving stress) were enrolled to gain a broader understanding of the facets of social connection that are impacted by ADRD caregiving among Latinos. Given that Study 2 aimed to intervene on social disconnection for caregivers and the purpose was to identify efficient screening of lonely caregivers, the UCLA 3-item LS score was not eliminated from eligibility criteria; however; the cutoff score on the UCLA 3-item LS for eligibility was lowered from 6 to ≥ 4, a cutoff score consistent with previous work (Barnes et al., 2022).

Table 2 contains a summary of recommendations based on the lessons learned throughout our recruitment efforts. We describe and discuss these recommendations in more detail below.

Table 2.

Recommendations to recruit socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers

| Conceptualization and Measurement of Social Disconnection in Latino Caregivers |

| • Consider qualitative or cognitive interviewing studies with Latino caregivers to assess whether cultural tailoring of screening measures is warranted. • Perform comprehensive screening of potential participants that encompasses culture-fair constructs of social disconnection (social isolation, social support, loneliness). |

| Online and In-Person Strategies |

| • Online strategies to increase recruitment of diverse Latino subpopulations, although may be limited to younger and middle-aged caregivers. • In-person strategies may better target older caregivers with less education and limited access to caregiving resources. |

| Other Key Strategies |

| • Partner with community organization leaders to identify vulnerable Latino caregivers in the community to recruit. • Collaborate with local agencies to identify needs amongst Latinos that can be addressed through educational community outreach and build trust in the community. • Develop strategies with community partners to link socially disconnected older Latino caregivers to online resources and technology literacy. • Increase contact efforts with previously unreached caregivers, at least one month following last contact attempt. |

Discussion

By providing a description, evaluation, and adaptation of recruitment strategies and challenges encountered in engaging Latino ADRD caregivers in research studies of social disconnection and loneliness, we hope to support other investigators’ efforts in this important research area. Our recruitment efforts built on previous recommendations for working with Latino ADRD caregivers, and other ethnic/racial underrepresented groups, including building meaningful community partnerships, working closely with community partners serving Latinos, and diversifying our research team (Brijnath et al., 2022; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003; National Academies of Science, 2021; Quiroz et al., 2022). We added three strategies to those in the literature: adapting the screening approach to identify lonely caregivers, utilizing online recruitment strategies, and implementing community education relevant to ADRD and mental health. The recruitment numbers suggest that each yielded some participation by caregivers, regardless of age, but each also had specific limitations.

Recruitment Challenges, Lessons, and Recommendations

Conceptualization and Measurement of Social Disconnection in Latino Caregivers

The most notable challenge in recruitment was related to the criteria utilized to identify socially disconnected caregivers. In the early recruitment phase, the majority of Latino caregivers scored below the cutoff identifying them as “lonely,” hindering recruitment. After scrutinizing and adapting to this challenge, we found caregivers in our studies who did not initially meet the cutoff on the 3-item screen (study 1), or who met a lower cutoff (Study 2), did in fact exceed the established cutoff for loneliness on the full UCLA LS 20-item scale.

Our observations align with previous studies of loneliness and cardiovascular and metabolic health that did not find elevated loneliness among Latinos with the same 3-item screening measure (Foti et al., 2020), suggesting that adjustments and cultural adaptation of screening instruments to improve their culture-fairness is an important step in studying social disconnection among Latino caregivers. For example, because Latinos are more likely to live in multigenerational households (Center, 2018), caregivers may not feel that they “lack companionship,” a concept underscored by the UCLA 3-item scale; however, caregivers may feel isolated from non-family connections or experience relational conflict, which are more fully captured by the UCLA LS 20-item. Thus, relying solely on the UCLA 3-item LS may not accurately reflect the experience of loneliness among Latino caregivers (and may result in false negative screens). As previously noted, we are further exploring our data to identify potentially important conceptual themes related to loneliness and social disconnectedness in these Latino caregivers (manuscript under development). As described in Table 2, we suggest that future research should employ qualitative approaches or cognitive interviewing (Beatty & Willis, 2007), in which Latino caregivers deconstruct existing measures and inform the development of adequate culture-fair screening tools. With the guidance of Latino caregivers, a culture-fair version of a briefer screening tool to identify loneliness in Latinos, including Latino caregivers (such as one derived from UCLA LS), could be developed. Our findings also have clinical implications regarding accurate screening and detection of indicators of poor mental health among Latino ADRD caregivers.

In addition, we suggest greater consideration be given to the multidimensional nature of social connectedness in Latino caregivers, given prior findings regarding low perceptions of social support (Balbim et al., 2020). Thus, a focus on loneliness per se in this population may be limiting when attempting to promote Latino caregivers’ social well-being. Future work should consider performing a comprehensive assessment that fits the multi-domain construct of social disconnection (social isolation, social support, and loneliness, Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017) when seeking to recruit socially disconnected Latino caregivers.

Online and In-Person Strategies

First, by definition, older socially disconnected caregivers are difficult to reach, given that they may be less likely to attend social events, access available services, and perhaps respond to calls for participation. Specific recruitment challenges for our studies were worsened primarily by COVID-19-related restrictions, as in-person activities were halted due to shelter-in-place guidelines, which dramatically reduced recruitment opportunities in places where older Latinos typically gather. For example, during the pandemic the senior center Centro de Oro paused its operations, and once restrictions were relaxed, the center opened only at a limited capacity. This presented a significant barrier to accessing older socially disconnected Latino caregivers. For this population, the senior center may be one of the limited opportunities to connect with others outside of their caregiving role and without this resource caregivers became even harder to reach.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic presented these challenges to in-person recruitment efforts, moving to online recruitment allowed us to mitigate some of those limitations. One finding to highlight, however, is the difference in age and education attainment between online versus in-person groups. Participants recruited for our studies from online sources were younger and reported higher levels of education than those recruited through in-person sources. It is possible that younger socially disconnected Latino caregivers may engage with the outside world more frequently via online platforms, as suggested by previous work (Brown et al., 2016; Iribarren et al., 2019). Thus, online recruitment methods may bias recruitment toward a younger, more educated, and possibly better resourced set of participants. Additionally, greater success with the online strategy may be explained by the longer duration for online recruitment compared to in-person strategies. This strategy was certainly appropriate to overcome recruitment challenges during the pandemic, but it may pose challenges in recruitment for some populations. As we note in Table 2, another outcome to highlight from online recruitment appears to be the opportunity to diversify study samples. For example, our local Latino population in the region is predominantly Puerto Rican, but online recruitment allowed us to connect with caregivers from different Latino sub-groups.

For older caregivers, however, limited technology-related literacy and access to technology is a barrier to engaging with research and research-related communications, a gap made wider throughout COVID-19 for many older adult populations. In recent work, Latinos over the age of 60 reported challenges accessing and navigating technological devices well enough to engage in ADRD-related online activities (Gutierrez et al., 2022). Those who did engage typically had a college education or higher. Our limited in-person efforts allowed us to recruit Latino caregivers who mostly reported an education below the college level and had an average age of over 60 years. More intensive in-person recruitment strategies in future studies could help target and recruit these vulnerable caregivers (Table 2), particularly those with limited education, health literacy, and internet knowledge, who are also less likely to obtain resources for their caregiving challenges.

Other Key Strategies

We provide additional key strategy recommendations in Table 2. First, A valuable advantage in working with a well-respected and wide-reaching Latino community services organization was the center Director’s direct involvement in recruitment. The Director personally connected HLESC members with Latino caregivers who could no longer attend the center due to the COVID-19 pandemic and were even more socially disconnected than the attendees. This highlights the importance of taking the time to build trusting partnerships with community organizations that work with underserved communities (Dawson et al., 2022) to address fear, skepticism, and mistrust (Natale et al., 2021).

The development and use of educational materials in connection with working with community partners was also a valuable outcome of this recruitment effort. Our team provided educational community outreach at the local senior center about Latino caregiving and mental health (an area of need identified by our community partner). Previous research suggests that community outreach is a viable and important approach to recruit ethnic/racially underrepresented individuals in Alzheimer’s disease research (Brijnath et al., 2022; Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. 2019). In addition, linking socially disconnected older Latino caregivers to online resources and technology literacy is likely to improve their quality of life.

Another helpful strategy was increasing the number of times we contacted caregivers interested in participating in our studies. Initially, interested individuals from all recruitment sources were contacted a maximum of three times to conduct the screening. As recruitment for the studies progressed, team members decided to contact previously non-reached caregivers following at least one month after last contact. In addition, voicemails were left both in Spanish and English to ensure that the caregiver could understand them. This increase in follow-up efforts and language consideration allowed us to connect with additional caregivers who enrolled in our studies. It is unclear whether the need for the increased outreach was due to factors related to social disconnection, or barriers related to the caregiver role or logistical barriers related to phone usage. Although a phone-based data collection approach eliminated transportation barriers and allowed more flexible times for caregivers to schedule the interviews, we encountered issues with phone connectivity including: participants would run out of minutes, phone numbers were disconnected, or interviews were interrupted because caregivers received other phone calls related to their caregiving role. Nonetheless, it is possible that all of these factors coupled with social and structural barriers that Latino caregivers face may support the increase in efforts to connect with this highly marginalized population.

In conclusion, the recommendations provided here are intended to both add to and reinforce what is being learned by the research community. Through concerted, culturally-attuned efforts, lonely, isolated, and poorly supported Latino caregivers can be better represented in clinical research and benefit from evidence-based interventions that ameliorate loneliness and isolation, and substantially support caregivers’ mental health and well-being.

Clinical Implications.

Socially disconnected Latino ADRD caregivers have an elevated risk for poor mental health outcomes including greater depression and chronic stress than other racial/ethnic groups.

More research is needed to better understand the construct of social disconnection (loneliness, social isolation, low social support) in Latino ADRD caregivers to inform adequate screening.

Successful recruitment of this population in clinical research will ensure the development of targeted and culturally sensitive interventions to improve the mental health and overall well-being of this highly marginalized group.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging to the Rochester Roybal Center for Social Ties & Aging Research (Roc STAR) [P30AG064103].

Biographies

Maria Quiñones-Cordero, PhD

Maria Quiñones-Cordero, PhD, is a Clinical Psychologist and an Assistant Professor of clinical nursing at the University of Rochester School of Nursing. Her research program has both methodological and applied themes. A key focus of Dr. Quiñones’ work is on mechanism-based intervention development and delivery aimed at reducing Latino health disparities. She leads work on expanding and implementing systematic approaches to cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions to fit the needs and characteristics of the Latino culture in order to improve access to and delivery of care, as well as cognitive and mental health-related outcomes. She also focuses in understanding the relationships among cognition, inflammation, and mental health symptoms (i.e., depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms) and the contributions of aging on these relationships. Her overall aim is to develop or identify interventions that effectively target these mechanisms to improve cognitive and mental health and quality of life of middle-aged and older Latinos.

Caroline Silva, PhD

Caroline Silva, PhD, is a Clinical Psychologist and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Rochester School of Medicine & Dentistry (SMD). Broadly, her research has examined interpersonal risk factors for suicide via the lens of a contemporary theory of suicide—the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. In particular, Dr. Silva has examined the role of two forms of social disconnection—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness—in suicide risk among high-risk populations, including sexual minorities, military service members, and clinical outpatients. Dr. Silva’s current program of research is focused on integrating the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide with cultural determinants of health to inform the development and evaluation of suicide prevention interventions for at-risk Hispanics.

Carmona Ross, MA

Ms. Carmona Ross collaborates on several community initiatives involving the health of some of the most vulnerable people and communities in Western NY. Carmona is an International Student Counselor at The University of Rochester. Her interest concerns the emotional and physical well-being of Black-identified women. More specifically, in the context of caregiving for adults with chronic conditions. Moreover, she is very interested in the lived experiences of underrepresented groups and communities, as well as the cultural practices that shape perceptions of health and well-being.

Silvia Sörensen, PhD

Silvia Sörensen, PhD, is a researcher in human development with particular interests in facilitating well-being among vulnerable older adults and their families. Collaborating with colleagues in ophthalmology, psychiatry, primary care, immunology, and with community-based health activists, she has developed and/or evaluated interventions to (1) promote positive health behaviors, (2) prevent mental and physical health problems, (3) increase access to mental health services for underserved groups, (4) assist older adults with preparation for future care, and (5) support well-being among older adults. Dr. Sörensen is a co-founder of the Aging Well Initiative community collaboration with faith-based organizations, and she has a particular interest in empowerment of underserved groups in order to reduce health disparities. Her specific areas of research include successful aging through preparation for future care, family caregiver stress and coping, interventions with caregivers, interventions with vision-impaired older adults, future thinking among older adults, as well as health literacy and patient education for diabetes prevention.

Raquel Serrano

Ms. Raquel Serrano is the Director for Elderly Services for Ibero American Action League, Inc. located in Rochester, NY. Over the last 25 years, she has developed healthy relationships with key individuals in the non-profit, private, religious, and governmental arenas. She considers herself to be well-rounded, a connector with a keen understanding of critical needs for management, organization, and networking. Her work has been instrumental in engaging older Latinos at the senior center Centro de Oro and acquiring services for the engaged older Latinos.

Ms. Serrano is also the Director for the Rochester Youth Association — an organization that has served to catapult youth from diverse backgrounds to the mission field. She takes pride in advocating for the Latino community and is particularly inspired by the progress and growth of the Latino community at large.

Kimberly Van Orden, PhD

Kimberly Van Orden, PhD, is a Clinical Psychologist who aims to increase understanding of how to address the significant public health problem of social isolation in later life. Dr. Van Orden focuses in understanding the different ways isolation (both perceived and ‘objective’) is expressed and experienced in later life, from restricted social networks, to loneliness, to low social support, to feeling as if one does not belong. She also strives to understand how to reduce isolation and promote connectedness using behavioral interventions. Her work encompasses developing new interventions to increase connectedness, as well as testing existing interventions that have promise for increasing connectedness, but have not been tested. Another focus of her work is theory testing to promote understanding of suicide and illuminate mechanisms that can serve as intervention targets.

Kathi Heffner, PhD

Dr. Heffner’s research centers on how psychosocial and behavioral factors affect physiological stress adaptation and the immune system. In particular, she is interested in the implications of stress for healthy aging; the influence of sleep on stress physiology and clinical symptoms, including chronic pain and trauma-related symptomatology; and the role of social relationships in stress and health links. Her work has been supported by multiple organizational, NIH and other federally funded grants. Over the course of her career, her research has evolved from a primary focus on human laboratory experiments to a complementary emphasis on clinical behavioral intervention trials. That approach has led to multidisciplinary collaborations with expert clinician researchers, including nurses, psychologists, physicians, and geriatricians, contributing to a better understanding of the basic mechanisms of stress and health, with the potential for immediate translation to clinical intervention.

Footnotes

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author.

We use the term “Latino” to refer to those who self-identify as Latino, Latina, or Latinx, while acknowledging there is important diversity within groups who identify as ethnically Latino or are part of one or more Latino sub-groups. Also, the terms Hispanic/Latino are used interchangeably in this paper. However, it is worth noting that Hispanic refers to persons of Spanish-speaking origin or ancestry, whereas Latino can be a broader term, referring to persons of Latin American origin or ancestry, including Brazilians.

References

- Adames HY, Chavez-Duenas NY, Fuentes MA, Salas SP, & Perez-Chavez JG (2014). Integration of Latino/a cultural values into palliative health care: a culture centered model. Palliat Support Care, 12(2), 149–157. 10.1017/S147895151300028X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams B, Aranda MP, Kemp B, & Takagi K (2002). Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 8(4), 279–301. 10.1023/a:1019627323558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SM, & Palermo AG (2010). Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health, 100(8), 1380–1387. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(3), 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- Balbim GM, Magallanes M, Marques IG, Ciruelas K, Aguinaga S, Guzman J, & Marquez DX (2020). Sources of Caregiving Burden in Middle-Aged and Older Latino Caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol, 33(4), 185–194. 10.1177/0891988719874119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbim GM, Marques IG, Cortez C, Magallanes M, Rocha J, & Marquez DX (2019). Coping Strategies Utilized by Middle-Aged and Older Latino Caregivers of Loved Ones with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia. J Cross Cult Gerontol, 34(4), 355–371. 10.1007/s10823-019-09390-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TL, Ahuja M, MacLeod S, Tkatch R, Albright L, Schaeffer JA, & Yeh CS (2022). Loneliness, Social Isolation, and All-Cause Mortality in a Large Sample of Older Adults. J Aging Health, 8982643221074857. 10.1177/08982643221074857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty PC, & Willis GB (2007). Research Synthesis: The Practice of Cognitive Interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(2), 287–311. 10.1093/poq/nfm006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Spenser M, & Folstein M (1988). The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology, 1(2), 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Brijnath B, Croy S, Sabates J, Thodis A, Ellis S, de Crespigny F, Moxey A, Day R, Dobson A, Elliott C, Etherington C, Geronimo MA, Hlis D, Lampit A, Low LF, Straiton N, & Temple J (2022). Including ethnic minorities in dementia research: Recommendations from a scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 8(1), e12222. 10.1002/trc2.12222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Lopez G, & Hugo Lopez M (2016). Digital divide narrows for Latinos as more Spanish speakers and immigrants go online. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2016/07/20/digital-divide-narrows-for-latinos-as-more-spanish-speakers-and-immigrants-go-online/

- Chin AL, Negash S, & Hamilton R (2011). Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 25(3), 187–195. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton K, Gao F, Jabbari J, Van Aman M, Dulle P, Hanson J, & Wildes TM (2022). Loneliness, social isolation, and social support in older adults with active cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Oncol, 13(8), 1122–1131. 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes YI, Duran M, Marginean V, Harris LK, Cazales A, Santiago L, Mislan MD, & Perreira KM (2022). Lessons Learned in Clinical Research Recruitment of Midlife Latinas During COVID-19. Menopause, 29(7), 883–888. 10.1097/GME.0000000000001983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe CL, Domingue BW, Graf GH, Keyes KM, Kwon D, & Belsky DW (2021). Associations of Loneliness and Social Isolation With Health Span and Life Span in the U.S. Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 76(11), 1997–2006. 10.1093/gerona/glab128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis S, Hetherington SA, Borodzicz JA, Hermiz O, & Zwar NA (2015). Challenges to establishing successful partnerships in community health promotion programs: local experiences from the national implementation of healthy eating activity and lifestyle (HEAL) program. Health Promot J Austr, 26(1), 45–51. 10.1071/HE14035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Rios LK, & Chapman-Novakofski K (2018). Latino/Hispanic Participation in Community Nutrition Research: An Interplay of Decisional Balance, Cultural Competency, and Formative Work. J Acad Nutr Diet, 118(9), 1687–1699. 10.1016/j.jand.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson S, Banister K, Biggs K, Cotton S, Devane D, Gardner H, Gillies K, Gopalakrishnan G, Isaacs T, Khunti K, Nichol A, Parker A, Russell AM, Shepherd V, Shiely F, Shorter G, Starling B, Williams H, Willis A, Witham MD, & Treweek S (2022). Trial Forge Guidance 3: randomised trials and how to recruit and retain individuals from ethnic minority groups—practical guidance to support better practice. Trials, 23(1). 10.1186/s13063-022-06553-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BC, Coon DW, & Crogan NL (2007). Personalismo and breaking barriers: accessing Hispanic populations for clinical services and research. Geriatr Nurs, 28(5), 289–296. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Caregiver Alliance. (2016). Caregiver Statistics: Demographics. https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/2016

- Foti SA, Khambaty T, Birnbaum-Weitzman O, Arguelles W, Penedo F, Espinoza Giacinto RA, Gutierrez AP, Gallo LC, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, & Llabre MM (2020). Loneliness, Cardiovascular Disease, and Diabetes Prevalence in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. J Immigr Minor Health, 22(2), 345–352. 10.1007/s10903-019-00885-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Leary MC, Ossinalde C, Romero JJ, Wald MJ, & Fernandez-Gamarra E (1997). Hispanic caregivers of older adults with dementia: Cultural issues in outreach and intervention. Group, 21(2), 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Singer LS, Depp C, Mausbach BT, Cardenas V, & Coon DW (2004). Effective Recruitment Strategies for Latino and Caucasian Dementia Family Caregivers in Intervention Research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12(5), 484–490. 10.1097/00019442-200409000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, & Areán P (2003). Recruitment and Retention of Latino Dementia Family Caregivers in Intervention Research: Issues to Face, Lessons to Learn. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Diaz L, Savundranayagam MY, Kloseck M, & Fitzsimmons D (2019). The Role of Cultural and Family Values on Social Connectedness and Loneliness among Ethnic Minority Elders. Clin Gerontol, 42(1), 114–126. 10.1080/07317115.2017.1395377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S, Duran N, & Norris K (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health, 104(2), e16–e31. 10.2105/AJPH.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Health Policy Center. (2020). Evidence-Informed Approaches to Measure Social Isolation among Older Adults. https://www.thanksmomanddadfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Social-Isolation-Report_FINAL.pdf

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, Flowers-Benton S, Block LM, Dilworth-Anderson P, Barnes LL, Shah MN, & Zuelsdorff M (2019). Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 5, 751–770. 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Cain R, Nadine D, & Aranda MP (2022). The Digital Divide Exacerbates Disparities in Latinx Recruitment for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Online Education During COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med, 8, 23337214221081372. 10.1177/23337214221081372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, & Sbarra DA (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol, 72(6), 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton KM (2017). Exploring the Barriers of Latino Caregivers of Persons with Alzhemer’s and the Underutilization of Services (Doctoral dissertation). https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1583&context=etd

- Ige J, Gibbons L, Bray I, & Gray S (2019). Methods of identifying and recruiting older people at risk of social isolation and loneliness: a mixed methods review. BMC Med Res Methodol, 19(1), 181. 10.1186/s12874-019-0825-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren S, Stonbraker S, Suero-Tejeda N, Granja M, Luchsinger JA, Mittelman M, Bakken S, & Lucero R (2019). Information, communication, and online tool needs of Hispanic family caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Inform Health Soc Care, 44(2), 115–134. 10.1080/17538157.2018.1433674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva M, Spangler S, Clavenger C, & Hepburn K (2021). Chronic Stress, Scoial Isolation, and Perceived Loneliness in Dementia Caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(10), 36–43. 10.3928/02793695-20180329-04Cited [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Depp C, Palmer BW, Glorioso D, Daly R, Liu J, Tu XM, Kim HC, Tarr P, Yamada Y, & Jeste DV (2019). High prevalence and adverse health effects of loneliness in community-dwelling adults across the lifespan: role of wisdom as a protective factor. Int Psychogeriatr, 31(10), 1447–1462. 10.1017/S1041610218002120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Cassidy J, Mitchell J, Jones S, & Jang SW (2022). Documented barriers to health care access among Latinx older adults: A scoping review. Educational Gerontology, 49(2), 81–95. 10.1080/03601277.2022.2082714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Badana ANS, Burgdorf J, Fabius CD, Roth DL, & Haley WE (2021). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Racial and Ethnic Differences in Dementia Caregivers’ Well-Being. Gerontologist, 61(5), e228–e243. 10.1093/geront/gnaa028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanque SM, & Enriquez M (2012). Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: a review of the literature. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 27(1), 23–32. 10.1177/1533317512439794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, & McGuire LC (2019). Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged >/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement, 15(1), 17–24. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Johnson JK, Perez-Stable EJ, & Whitmer RA (2017). Survival after dementia diagnosis in five racial/ethnic groups. Alzheimers Dement, 13(7), 761–769. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DJ, McDonald MA, Cook J, Heurtin-Roberts S, Updegrove S, Sampson D, Gutter S, & Eder M (2011). Community Engagement: Definitions and Organizing Concepts from the Literature. (NIH Publication No. 11-7782). (Principles of Community Engagement, Issue.

- McGregor B, Belton A, Henry TL, Wrenn G, & Holden KB (2019). Improving Behavioral Health Equity through Cultural Competence Training of Health Care Providers. Ethn Dis, 29(Suppl 2), 359–364. 10.18865/ed.29.S2.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Applewhite SR, Lara VE, & Toykawa N (2016). The Concept of Familis in the Lived Experiences of Mexican-Origin Caregivers. J Marriage Fam, 78(3), 813–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel S, Alvira M, Farré M, Risco E, Cabrera E, Zabalegui A (2016). Quality of life and associated factors in older people with dementia living in long-term institutional care and home care. European Geriatric Medicine, 7(4), 346–351. 10.1016/j.eurger.2016.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza M, Siebert S, Pratt A, Insch E, McIntosh F, Paton J, Wright C, Buckley CD, Isaacs J, McInnes IB, Raza K, & Falahee M (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on recruitment to clinical research studies in rheumatology. Musculoskeletal Care, 20(1), 209–213. 10.1002/msc.1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro-Rodriguez J, & Gallager-Thompson D (2020). Stress and Coping: Conceptual Models for Understanding Dementia among Latinos. In Adames HY & Tazeau YN (Eds.), Caring for Latinxs with dementia in a globalized world. Behavioral and Psychosocial Treatments. (pp. 231–246). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Natale P, Saglimbene V, Ruospo M, Gonzalez AM, Strippoli GF, Scholes-Robertson N, Guha C, Craig JC, Teixeira-Pinto A, Snelling T, & Tong A (2021, Jun). Transparency, trust and minimizing burden to increase recruitment and retention in trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol, 134, 35–51. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Science, E., and Medicine (2021). Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward (2021). The National Academies Press. 10.17226/26026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen C, Pedersen I, Bergland A et al. Differences in quality of life in home-dwelling persons and nursing home residents with dementia – a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 16, 137 (2016). 10.1186/s12877-016-0312-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, & Riddle M (2014, Jan 1). Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health. Clin Psychol Sci, 2(1), 22–34. 10.1177/2167702613497932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organizing Committee for Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement in Health & Health Care Programs & Policies. (2022). Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement: A Conceptual Model to Advance Health Equity through Transformed Systems for Health. NAM Perspectives. Comentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. 10.31478/202202c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacesetters Programme. (2008). A dialogue of equals. The Pacesetters Programme Community Engagement Guide. London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2013). National survey of Latinos. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/dataset/2013-national-survey-of-latinos/.

- Pew Research Center. (2018). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/dataset/2013-national-survey-of-latinos/

- Pinquart M & Sörensen S (2005b). Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 90–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz YT, Solis M, Aranda MP, Arbaje AI, Arroyo-Miranda M, Cabrera LY, Carrasquillo MM, Corrada MM, Crivelli L, Diminich ED, Dorsman KA, Gonzales M, Gonzalez HM, Gonzalez-Seda AL, Grinberg LT, Guerrero LR, Hill CV, Jimenez-Velazquez IZ, Guerra JJL, Lopera F, Maestre G, Medina LD, O’Bryant S, Penaloza C, Pinzon MM, Mavarez RVP, Pluim CF, Raman R, Rascovsky K, Rentz DM, Reyes Y, Rosselli M, Tansey MG, Vila-Castelar C, Zuelsdorff M, Carrillo M, & Sexton C (2022). Addressing the disparities in dementia risk, early detection and care in Latino populations: Highlights from the second Latinos & Alzheimer’s Symposium. Alzheimers Dement. 10.1002/alz.12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, & Padilla-Martinez V (2020). Latino families living with dementia: Behavioral issues and placement considerations. In Adames HY & Tazeau YN (Eds.), Caring for Latinxs with Dementia in a Globalized World. Behavioral and Psychosocial Treatments (pp. 133–153). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0132-7_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosental Gelman C (2014). Familismo and it Impact on the Family Caregiving of Latinos with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Complex Narrative. Research on Aging, 36(1), 40–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote S, Angel J, & Hinton L (2019). Characteristics and Consequences of Family Support in Latino Dementia Care. J Cross Cult Gerontol, 34(4), 337–354. 10.1007/s10823-019-09378-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW (1996). UCLA Lonliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Madsen KR, & Koushede V (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62–e70. 10.1016/s2468-2667(19)30230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage B, Foli KJ, Edwards NE, & Abrahamson K (2016). Familism and Health Care Provision to Hispanic Older Adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(1), 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, & Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry, 59, 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S & Pinquart M (2005). Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship of caregiving stressors, resources, and sociodemographic variables to caregiver depression and perceived physical health. Journal of Aging and Mental Health, 9(05), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, & Wardle J (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(15), 5797–5801. 10.1073/pnas.1219686110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies W, & Bleiler L (2011). 2011 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts And Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(2), 208–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton T (2003). Analysis of the Reliability of the Modified Cargiver Strain Index. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 58(2), S127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, & Heffner KL (2022). Promoting Social Connection in Dementia Caregivers: A Call for Empirical Development of Targeted Interventions. Gerontologist, gnac032. 10.1093/geront/gnac032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Conwell Y, Chapman BP, Buttaccio A, VanBergen A, Beckwith E, Santee A, Rowe J, Palumbos D, Williams G, Messing S, Sörensen S, & Tu X The helping older people engage (HOPE) study: Protocol & COVID modifications for a randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 30, 101040. 10.1016/j.conctc.2022.101040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega IE, Cabrera LY, Wygant CM, Velez-Ortiz D, & Counts SE (2017). Alzheimer’s Disease in the Latino Community: Intersection of Genetics and Social Determinants of Health. J Alzheimers Dis, 58(4), 979–992. 10.3233/JAD-161261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian M, & Xu L (2020). Social support and self-rated health among caregivers of people with dementia: The mediating role of caregiving burden. Dementia (London), 19(8), 2621–2636. 10.1177/1471301219837464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]