Abstract

Background:

The core needle biopsy (CNB) diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) generally mandates follow up excision, but controversy exists on whether small foci of ADH require surgical management. This study evaluated the upgrade rate at excision of focal ADH (fADH), defined as 1 focus spanning ≤2 mm.

Methods:

We retrospectively identified in-house CNBs with ADH as the highest risk lesion obtained between January 2013 and December 2017. A radiologist assessed radiologic-pathologic concordance. All CNB slides were reviewed by two breast pathologists and ADH was classified as fADH and non-focal ADH based on extent. Only cases with follow up excision were included. The slides of excision specimens with upgrade were reviewed.

Results:

The final study cohort consisted of 208 radiologic-pathologic concordant CNBs, including 98 fADH and 110 non-focal ADH. The imaging targets were calcifications (157), a mass (15), non-mass enhancement (27) and mass enhancement (9). Excision of fADH yielded 7 (7%) upgrades (5 ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), 2 invasive carcinoma) versus 24 (22%) upgrades (16 DCIS, 8 invasive carcinoma) at excision of non-focal ADH (p=.01). Both invasive carcinomas found at excision of fADH were subcentimeter tubular carcinomas away from the biopsy site and deemed incidental.

Conclusion:

Our data shows a significantly lower upgrade rate at excision of focal ADH than non-focal ADH. This information can be valuable if nonsurgical management of patients with radiologic-pathologic concordant CNB diagnosis of focal ADH is being considered.

Keywords: breast cancer, upgrade, ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, core biopsy

Introduction

Up to 14% of breast CNBs targeting screen detected lesions yield atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), an epithelial proliferation with the same degree of cytologic atypia as low grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).1–3 ADH is distinguished from DCIS based on architectural complexity and extent4, 5, according to guidelines developed from the examination of excisional biopsies.1 As only limited tissue is available in CNB samples, the quantitative criteria used to separate ADH and low grade DCIS cannot always be applied. Although the average rate of upgrade at excision of ADH is approximately 30%, rates range from 0% to 84%.6 The wide range of upgrade rates is in part attributable to possible under sampling associated with CNB, and to interobserver variation in the diagnosis of ADH, with one study reporting overall concordance of only 48%.7 Surgical excision of any lesion yielding ADH at CNB is performed routinely, however, in the era of de-escalation of treatment, controversy exists regarding the need to excise minute foci of ADH.

In one of the earliest studies addressing this issue, Ely et al.8 used the number of affected terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) to identify which cases of ADH were more likely to yield carcinoma at excision. They observed that ADH involving ≥4 TDLUs was significantly more likely to be upgraded to carcinoma than ADH in only 1 or 2 TDLUs, with upgrade rates of 86.6% (13/15) versus 0% (0/24), respectively. Subsequent studies have yielded conflicting results, with some concluding that observation is safe for a subset of patients with only small amounts of ADH on CNB9–13 while others recommend excision for all cases of ADH, regardless of size.6, 14–17

To address this issue, we evaluated the upgrade rate of focal ADH (fADH), defined as a single focus spanning ≤ 2mm, versus non-focal ADH and assessed the severity of the upgrades to determine whether a subset of our patients could be safely spared surgical excision.

Methods

Study population

A retrospective search of the institutional pathology database identified all consecutive in-house breast CNBs obtained between January 2013 and December 2017 with the diagnosis of ADH. CNBs with a concurrent diagnosis of DCIS and/or invasive carcinoma were excluded. CNBs with flat epithelial atypia (FEA) or classic lobular neoplasia (LN), including atypical lobular hyperplasia and classic lobular carcinoma in situ were included in the study, as these findings do not mandate excision at our center, based on the results of previous studies.18, 19 We included in our series only cases with available follow-up excision performed at our center. CNBs from patients with concurrent ipsilateral carcinoma who did not have a separate excision of the focus of ADH were excluded. Radiologic-pathologic concordance was assessed for all study cases. The Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Histopathologic review

All CNB hematoxylin and eosin-stained (H&E) slides were re-reviewed by two study breast pathologists (AG and EB) to confirm the diagnosis of ADH. The number of foci of ADH in each CNB specimen was assessed, as defined by Ely et al.8 Cases were divided into those with fADH (defined as ADH limited to one TDLU and spanning ≤2 mm), and non-focal (defined as ADH involving ≥2 TDLUs). The microscopic span of the largest focus of ADH was recorded. The presence of FEA and/or classic LN in the CNB material was also noted. The presence and location of calcifications was recorded. An upgrade was defined as DCIS and/or invasive cancer in the surgical excision.

All H&E slides of surgical excision specimens with upgrade were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis. We also assessed whether the carcinoma was near the core biopsy site, i.e. if it was present on tissue sections with or without core biopsy site changes. The findings in excision specimens without upgrade were recorded from pathology reports.

Radiology review

The study breast radiologist (SB) reviewed all pertinent imaging findings obtained before, at the time of, and after CNB. Imaging modality, type and diameter of the imaging target, gauge of biopsy needle, number of tissue cores, and whether the target lesion appeared entirely removed by the CNB were recorded for each case. If the CNB targeted calcifications, the imaging distribution and morphology were detailed.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was used to compare clinical and pathological characteristics. Continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted using the upgrade status as the dependent variable and the significant covariates from univariate analysis as independent variables. All analyses were done using R 3.6.3. Type I error rate was set to 0.05 (α).

Results

Study population

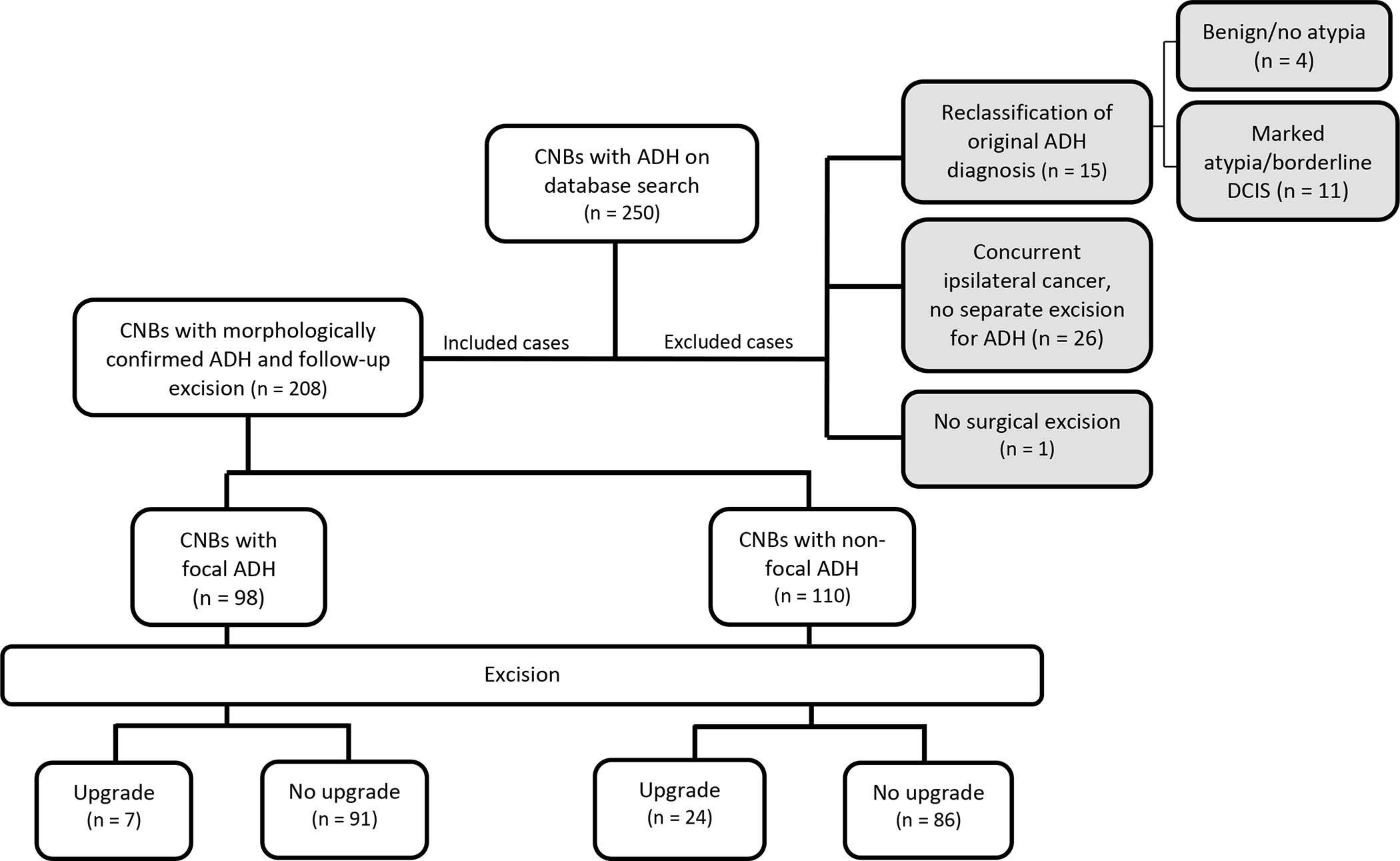

The study cohort consists of 208 CNBs from 202 women, including 6 women with bilateral CNBs. Case selection is summarized in Figure 1. The median patient age was 53 years (range: 21, 79). Most (122/202, 60%) women had no personal history of breast cancer. Eighty women (40%, 80/202) had prior and/or concurrent breast carcinoma (13 ipsilateral, 64 contralateral, and 3 bilateral).

Figure 1: Summary of study design and results.

CNB – core needle biopsy, ADH – atypical ductal hyperplasia, DCIS – ductal carcinoma in situ

Mammography was the CNB imaging modality in 77% (159/208) of cases, MRI in 17% (36/208) and ultrasound imaging in 6% (13/208) (Table 1). The mammographic target consisted of calcifications in 99% of cases (157/159) and of a mass in 2/159 (1%). The radiologic features of cases targeting calcifications are detailed in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The target of MRI-guided CNBs was non-mass enhancement (NME) in 75% (27/36) of cases and mass enhancement in 25% (9/36). All ultrasound guided CNBs targeted masses. Most (97%, 202/208) CNBs were vacuum assisted, except for 6/208 (3%) ultrasound-guided biopsies. The median number of tissue cores per CNB was 8 (range: 1, 18). A 9-gauge needle was used in 183/208 (88%) CNBs (Table 1). The median lesion diameter was 7 mm (range: 1, 80). The CNB completely removed the imaging target in 73/208 (35%) cases while a residual target lesion was identified on post-biopsy images in 135/208 (65%). All CNBs were deemed to be pathologically concordant with the imaging findings.

Table 1:

Univariate analysis of factors associated with upgrade at excision

| Variable | Overall (n=208) n (%) | No Upgrade (n=177) n (%) | Upgrade (n=31) n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.094 | |||

| <50 years | 70 (34%) | 55 (31%) | 15 (48%) | |

| ≥50 years | 138 (66%) | 122 (69%) | 16 (52%) | |

| Imaging modality | 0.7 | |||

| Mammogram | 159 (76%) | 137 (77%) | 22 (71%) | |

| MRI | 36 (17%) | 29 (16%) | 7 (23%) | |

| Ultrasound | 13 (6.2%) | 11 (6.2%) | 2 (6.5%) | |

| Target lesion diameter | <0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (4, 13) | 6 (4, 12) | 10 (7, 28) | |

| Number of cores removed | 0.8 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (6, 9) | 8 (6,9) | 8 (6,9) | |

| Needle gauge | 0.5 | |||

| 9 | 183 (88%) | 157 (89%) | 26 (84%) | |

| 10 | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| 11 | 3 (1.4%) | 3 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 12 | 12 (5.8%) | 9 (5.1%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| 13 | 2 (1.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 14 | 5 (2.4%) | 4 (2.3%) | 1 (3.2%) | |

| Target fully removed by CNB | 0.027 | |||

| Yes | 73 (35%) | 68 (38%) | 5 (16%) | |

| No | 135 (65%) | 109 (61%) | 26 (84%) | |

| Extent of ADH | 0.006 | |||

| Focal | 98 (47%) | 91 (51%) | 7 (23%) | |

| Non-focal | 110 (53%) | 86 (49%) | 24 (77%) | |

| Co-existing atypia in CNB | ||||

| FEA | 43 (21%) | 34 (19%) | 9 (29%) | 0.3 |

| Lobular neoplasia | 42 (20%) | 36 (20%) | 6 (19%) | >0.9 |

| Prior/concurrent breast carcinoma | 0.4 | |||

| Yes | 82 (39%) | 67 (38%) | 15 (48%) | |

| No | 126 (61%) | 110 (62%) | 16 (52%) | |

IQR – interquartile range, CNB – core needle biopsy, ADH – atypical ductal hyperplasia, FEA – flat epithelial atypia

Focal ADH was present in 98/208 (47%) CNBs. The average size of the largest focus of ADH was 1.8 mm (range: 0.3, 2). The clinical and pathologic features of the fADH cohort are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2:

Univariate analysis of factors associated with upgrade at excision in focal ADH cohort

| Variable | Overall (n=98) n (%) | No Upgrade (n=91) n (n%) | Upgrade (n=7) n (n%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.2 | |||

| <50 years | 32 (33%) | 28 (31%) | 4 (57%) | |

| ≥50 years | 66 (67%) | 63 (69%) | 3 (43%) | |

| Imaging modality | 0.2 | |||

| Mammogram | 80 (82%) | 74 (81%) | 6 (86%) | |

| MRI | 13 (13%) | 13 (14%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ultrasound | 5 (5.1%) | 4 (4.4%) | 1 (14%) | |

| Imaging target | 0.6 | |||

| Calcifications | 78 (80%) | 72 (79%) | 6 (86%) | |

| Mass | 7 (7.1%) | 6 (6.6%) | 1 (14%) | |

| Non-mass enhancement | 9 (9.2%) | 9 (9.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mass enhancement | 4 (4.1%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Target lesion diameter | 0.15 | |||

| 1–5 mm | 46 (47%) | 44 (49%) | 2 (29%) | |

| 6–10 mm | 30 (30%) | 25 (27%) | 5 (71%) | |

| 11–20 mm | 15 (15%) | 15 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

| >20 mm | 7 (7.2%) | 7 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Target fully removed by CNB | 0.7 | |||

| Yes | 37 (38%) | 35 (38%) | 2 (29%) | |

| No | 61 (62%) | 56 (62%) | 5 (71%) | |

| Co-existing atypia in CNB | ||||

| FEA | 20 (20%) | 16 (18%) | 4 (57%) | 0.03 |

| Lobular neoplasia | 27 (28%) | 25 (27%) | 2 (29%) | >0.9 |

| Prior/concurrent breast carcinoma | >0.9 | |||

| Yes | 34 (35%) | 32 (35%) | 2 (29%) | |

| No | 64 (65%) | 59 (65%) | 5 (71%) | |

CNB – core needle biopsy, ADH – atypical ductal hyperplasia, FEA – flat epithelial atypia

Non-focal ADH was present in 110/208 (53%) CNBs (Table 1). The average number of foci/involved TDLUs was 2.9 (range: 2, 8). The average size of the largest focus of ADH was 1.8 mm (range: 0.5, 6).

ADH was the only high risk lesion in 136/208 (65%) CNBs. In 72/208 (35%) CNBs ADH co-existed with other atypical lesions including FEA (12 fADH, 18 non-focal ADH), classic LN (19 fADH, 10 non-focal ADH) and FEA and classic LN (8 fADH, 5 non-focal ADH).

The majority (185/202; 92%) of women underwent wide local excision of ADH, but 17 patients had a mastectomy (including 14 women with concurrent contralateral carcinoma, 1 with prior contralateral carcinoma, 1 with family history of breast cancer and 1 woman who chose mastectomy). Overall, excision of ADH yielded an upgrade in 31/208 (15%) cases, including 21 DCIS and 10 invasive carcinomas.

Focal ADH versus non-focal ADH: upgrades at excision and statistical analysis

Excision of 98 cases of fADH yielded 7 (7%) upgrades, including 2 hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative tubular carcinomas, spanning 4.5 mm and 6 mm, and 5 DCIS with low or intermediate nuclear grade (Table 3). Two women with fADH and upgrade at excision had prior/concurrent carcinoma.

Table 3:

Imaging and Excision findings of upgraded cases showing focal atypical ductal hyperplasia on core needle biopsy

| Imaging Findings | Excision Findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Imaging modality | Lesion type | Lesion diameter (mm) | Target removed by CNB | DCIS at excision | DCIS grade | IC at excision | IC grade |

| 1 | MMG | Ca++ | 7 | No | Yes (3 mm) | Intermediatea | No | - |

| 2 | US | Mass | 8 | No | Yesb | Low | No | - |

| 3 | MMG | Ca++ | 5 | No | Yes (2.1 mm) | Lowa | No | - |

| 4 | MMG | Ca++ | 8 | No | Yes (30 mm) | Intermediatea | No | - |

| 5 | MMG | Ca++ | 4 | Yes | Yes (12 mm) | Intermediatea | No | - |

| 6 | MMG | Ca++ | 7 | Yes | No | - | Yesc (4.5 mm) | Grade 1 (tubular carcinoma) |

| 7 | MMG | Ca++ | 6 | No | No | - | Yesc (6 mm) | Grade 1 (tubular carcinoma) |

Calcifications identified in DCIS

DCIS difficult to quantify due to dispersed nature, focally involves intraductal papilloma

Not associated with the biopsy site

MMG – mammogram, US – ultrasound, Ca++ - calcifications, CNB – core needle biopsy, DCIS – ductal carcinoma in situ, IC – invasive carcinoma

The CNBs with fADH and subsequent upgrade targeted mammographic calcifications in 6 cases, ranging from 4 to 8 mm maximally, and one sonographic mass with angular margins and spanning 8 mm. Both cases upgraded to tubular carcinoma targeted calcifications and had a single 0.5 mm focus of ADH. The tubular carcinomas were deemed “incidental” as they did not harbor calcifications and were in tissue sections without biopsy changes (Supplemental Table 2).

Of the 5 upgrades to DCIS, the DCIS nuclear grade was intermediate in 3 cases and low in 2 (Table 3). Four of the 5 CNBs targeted calcifications and the size of fADH was 1.0 to 1.5 mm. At excision, DCIS harbored calcifications in all 4 cases targeting calcifications; the nuclear grade was intermediate in 3 cases, and low in one. One patient had a history of a prior contralateral DCIS. The remaining CNB with upgrade to low grade DCIS targeted a sonographic mass and contained fADH spanning 1.0 mm. This patient had a concurrent ipsilateral diagnosis of DCIS. In all cases upgraded to DCIS at excision, the DCIS was associated with the prior biopsy site.

Twenty-four of 110 (22%) CNBs with non-focal ADH yielded an upgrade at excision (8 invasive carcinomas, 16 DCIS). Seven invasive carcinomas were well-differentiated, with sizes ranging from 1.1 mm to 5 mm. The remaining invasive carcinoma was moderately differentiated and spanned 12 mm. Of the 16 DCIS upgrades, 12 were of low nuclear grade and 4 of intermediate grade. Thirteen of the 24 patients with non-focal ADH and upgrade had a personal history of carcinoma.

On univariate analysis, the upgrade rate correlated with the size of the imaging target (p=<.001), with its incomplete removal at the time of CNB (p=.03), and with the extent of ADH (Table 1). Cases with fADH were less likely to be upgraded to carcinoma than cases with non-focal ADH (p=.01). On multivariable analysis only the extent of ADH was statistically significant (p=.01), while the lesion diameter on imaging and the presence of residual target after CNB were not (p=.06 and p=.12, respectively). Imaging modality, number of tissue cores removed, needle gauge, co-existing atypia and prior/concurrent breast carcinoma were not associated with the likelihood of upgrade (Table 1).

When examining the fADH cohort alone, coexisting FEA was associated with upgrade in univariate analysis (p=.03) (Table 2). No other feature was significantly correlated with upgrade, though we observed a trend toward increased risk of upgrade for larger imaging targets. In particular, the upgrade rate of radiographic lesions spanning ≤5 mm was only 4% (2/46) versus 10% (5/52) for those spanning >5 mm. Similarly, the upgrade rate tended to be higher when the CNB did not completely remove the imaging target.

Discussion

The diagnosis of ADH found at CNB is an accepted indication for surgical excision, driven by the potential for upgrade. In our series, the upgrade rate of non-focal ADH was 22% (24/110), with upgrade rates to DCIS of 15% and to invasive carcinoma of 7%, warranting routine excision. In contrast, only 7% (7/98) of CNBs with fADH yielded carcinoma at excision (5% to DCIS and 2% to invasive carcinoma). Sutton et al.17 reported an overall upgrade rate of 19% (16/84) at excision of ADH, noting that ADH involved more than 1 duct in 15 of the 16 cases with upgrade.17 Likewise, in our cohort lesions yielding only fADH at CNB are less likely to result in upgrade.

Together with fADH, we identified a trend towards lower upgrade rates in cases with low risk imaging findings, which suggests that a combination of pathologic and radiologic features could identify a subset of patients at low risk of upgrade at excision, who might be considered for close imaging surveillance. Williams et al.13 observed a significant association of both smaller lesion size (<1 cm) and larger percentage of lesion removed (>50%) with lower risk of upgrade of ADH at excision, yet these features alone were insufficient to predict upgrade rates low enough to stratify patients into alternative forms of management. However, if the CNB yielded only focal ADH (defined as involvement of <3 ducts) and the CNB imaging target had low risk features no cases were upgraded.13 Using a similar approach, Pena et al.20 developed a definition of ADH at low risk for upgrade, which included absence of individual cell necrosis, and either 1 focus of ADH with ≥50% of target removed, or 2 to 3 foci of ADH that is ≥90% removed. They reported a 4.9% upgrade rate for lesions meeting the low risk criteria compared to 21.4% for those that did not.

Concerns regarding observation over excision in women with ADH stem from the limited understanding of its natural evolution. The progression of ADH to carcinoma is poorly understood.21 Menen et al.11 observed 125 patients with a CNB diagnosis of ADH deemed at low risk of upgrade who did not undergo excision. After a median of 3 years, only 7 patients developed carcinoma (all ipsilateral) and only 1 (0.8%) tumor was at the site of the index CNB. In our series, fADH yielded only two upgrades to tubular carcinoma, and both were regarded as “incidental” findings. Tubular carcinoma typically has indolent course and excellent prognosis.1, 22, 23

There are multiple ongoing clinical trials examining non-surgical approaches for patients with non-high grade DCIS.24 Of the 5 fADH cases upgraded to DCIS in our series, four would have been eligible for inclusion into at least one of these trials if the DCIS had been diagnosed at CNB. Using a risk projection model, Grimm et al.25 estimated that for a 7% upgrade rate, as in our fADH cohort, the median 10-year, breast cancer specific, cumulative mortality for a 60 year old woman with low to intermediate grade DCIS on active surveillance was 1.4%. In comparison, the SEER database estimate of 10-year disease specific mortality for usual care was also 1.4% versus the 10 year mortality for other causes at 6.1%.25

Precise assessment of the size and number of foci of ADH on CNB is essential if cases of fADH are not excised. While an interobserver reproducibility study performed with 4 study breast pathologists showed substantial agreement on the diagnosis of ADH (kappa=0.669 to 0.918), there was considerable variation in the evaluation of the extent of ADH (data not shown). When asked to assess the number of foci of ADH in each sample there was complete agreement amongst the pathologists on only 36% (4/11) of cases. Prior studies have observed the lowest kappa agreement values for the specific diagnosis of ADH.26 Elmore et al.7 noted over-interpretation of atypia in 17% and under-interpretation in 35% of CNBs. This variability might be reduced by consulting with colleagues, which was not permitted in Elmore et al’s7 study or in our own assessment. Although prospective review of all fADH cases by the breast pathology team could be implemented to achieve consensus if fADH cases were to be managed differently than ADH, in our opinion, the results of this and similar studies may find best application in the management of patients with a CNB diagnosis of ADH and comorbidities that pose a substantial surgical risk. In this setting, knowing whether only fADH is present could contribute significantly to patient management.

Our study has limitations. This is a retrospective, single institution review and though we demonstrate a few upgrade events the length of follow up is limited. At our center, a team of experienced and dedicated breast pathologists review all breast cases, including all breast CNBs, which has been shown to enhance diagnostic accuracy and thus may impact the applicability of our findings to a generalized setting. While we found that FEA coexisting with fADH significantly increased the risk of upgrade, this observation warrants independent validation in larger series.

In summary, we demonstrate a low upgrade rate of fADH at excision. Our data suggest that radiologic-pathologic concordant CNBs targeting lesions ≤5 mm, which are completely removed at CNB and yield fADH, may be candidates for nonoperative management in the appropriate clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

In the setting of radiologic-pathologic concordance, excision of focal ADH has a significantly lower upgrade rate than non-focal ADH. Integration of radiologic, pathologic, and clinical features can identify patients with focal ADH suitable for nonsurgical management if clinical need arises.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748).

Footnotes

Disclosures: This work was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748). Author AG is a consultant for Paige.AI, HYW reports consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, MM has received honoraria from Roche and Genomic Health. All authors report no direct competing interests.

References

- 1.Lokuhetty D, White VA, Watanabe R, Cree IA. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Breast tumors. Lyon; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison KH, Abraham LA, Weaver DL, et al. Trends in breast biopsy pathology diagnoses among women undergoing mammography in the United States: a report from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Cancer. May 1 2015;121(9):1369–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eby PR, Ochsner JE, DeMartini WB, Allison KH, Peacock S, Lehman CD. Frequency and upgrade rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: 9-versus 11-gauge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Jan 2009;192(1):229–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. Jun 1 1985;55(11):2698–708. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. A comparison of the results of long-term follow-up for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and intraductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer. Feb 1 1990;65(3):518–29. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiaffino S, Calabrese M, Melani EF, et al. Upgrade Rate of Percutaneously Diagnosed Pure Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 6458 Lesions. Radiology. Jan 2020;294(1):76–86. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elmore JG, Longton GM, Carney PA, et al. Diagnostic concordance among pathologists interpreting breast biopsy specimens. JAMA. Mar 17 2015;313(11):1122–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ely KA, Carter BA, Jensen RA, Simpson JF, Page DL. Core biopsy of the breast with atypical ductal hyperplasia: a probabilistic approach to reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. Aug 2001;25(8):1017–21. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200108000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LY, Hu J, Tsang JYS, et al. Diagnostic upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast based on evaluation of histopathological features and calcification on core needle biopsy. Histopathology. Sep 2019;75(3):320–328. doi: 10.1111/his.13881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, Wasif N, Giurescu ME, McCullough AE, Gray RJ. Atypical ductal hyperplasia on core biopsy: an automatic trigger for excisional biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol. Oct 2012;19(10):3264–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2575-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menen RS, Ganesan N, Bevers T, et al. Long-Term Safety of Observation in Selected Women Following Core Biopsy Diagnosis of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol. Jan 2017;24(1):70–76. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5512-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen CV, Albarracin CT, Whitman GJ, Lopez A, Sneige N. Atypical ductal hyperplasia in directional vacuum-assisted biopsy of breast microcalcifications: considerations for surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. Mar 2011;18(3):752–61. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1127-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams KE, Amin A, Hill J, et al. Radiologic and Pathologic Features Associated With Upgrade of Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia at Surgical Excision. Acad Radiol. Jul 2019;26(7):893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Co M, Kwong A, Shek T. Factors affecting the under-diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsies - A 10-year retrospective study and review of the literature. Int J Surg. Jan 2018;49:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eby PR, Ochsner JE, DeMartini WB, Allison KH, Peacock S, Lehman CD. Is surgical excision necessary for focal atypical ductal hyperplasia found at stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol. Nov 2008;15(11):3232–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0100-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohr JR, Eby PR, Allison KH, et al. Risk of upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia after stereotactic breast biopsy: effects of number of foci and complete removal of calcifications. Radiology. Jun 2010;255(3):723–30. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton T, Farinola M, Johnson N, Garreau JR. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: Clinicopathologic factors are not predictive of upgrade after excisional biopsy. Am J Surg. May 2019;217(5):848–850. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grabenstetter A, Brennan S, Salagean ED, Morrow M, Brogi E. Flat Epithelial Atypia in Breast Core Needle Biopsies With Radiologic-Pathologic Concordance: Is Excision Necessary? Am J Surg Pathol. Feb 2020;44(2):182–190. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray MP, Luedtke C, Liberman L, Nehhozina T, Akram M, Brogi E. Classic lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia at percutaneous breast core biopsy: outcomes of prospective excision. Cancer. Mar 1 2013;119(5):1073–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pena A, Shah SS, Fazzio RT, et al. Multivariate model to identify women at low risk of cancer upgrade after a core needle biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Jul 2017;164(2):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4253-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kader T, Hill P, Rakha EA, Campbell IG, Gorringe KL. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: update on diagnosis, management, and molecular landscape. Breast Cancer Res. May 2 2018;20(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0967-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metovic J, Bragoni A, Osella-Abate S, et al. Clinical Relevance of Tubular Breast Carcinoma: Large Retrospective Study and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:653388. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.653388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rakha EA, Lee AH, Evans AJ, et al. Tubular carcinoma of the breast: further evidence to support its excellent prognosis. J Clin Oncol. Jan 1 2010;28(1):99–104. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.23.5051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanbayashi C, Thompson AM, Hwang E-SS, et al. The international collaboration of active surveillance trials for low-risk DCIS (LORIS, LORD, COMET, LORETTA). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(15_suppl):TPS603–TPS603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.TPS603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimm LJ, Ryser MD, Partridge AH, et al. Surgical Upstaging Rates for Vacuum Assisted Biopsy Proven DCIS: Implications for Active Surveillance Trials. Ann Surg Oncol. Nov 2017;24(12):3534–3540. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6018-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain RK, Mehta R, Dimitrov R, et al. Atypical ductal hyperplasia: interobserver and intraobserver variability. Mod Pathol. Jul 2011;24(7):917–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.