Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an unprecedented relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses in opioid agonist treatment (OAT). We conducted a mixed methods systematic review to explore the impact of these changes on program effectiveness and client experiences in OAT.

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022352310). From Aug.–Nov. 2022, we searched Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Web of Science, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, and the grey literature. We included studies reporting quantitative measures of retention in treatment, illicit substance use, overdose, client health, quality of life, or treatment satisfaction or using qualitative methods to examine client experiences with take-home doses during the pandemic. We critically appraised studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. We synthesized quantitative data using vote-counting by direction of effect and presented the results in harvest plots. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic synthesis. We used a convergent segregated approach to integrate quantitative and qualitative findings.

Results

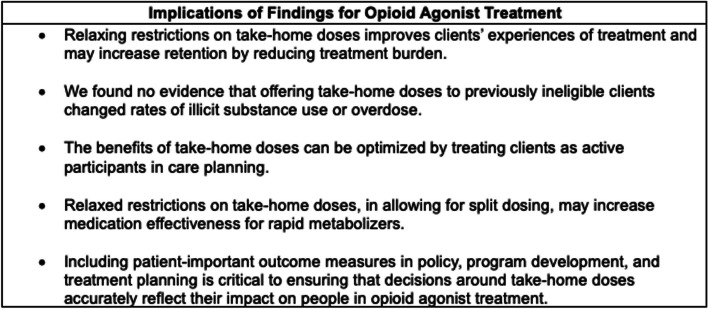

Forty studies were included. Most were from North America (23/40) or the United Kingdom (9/40). The quantitative synthesis was limited by potential for confounding, but suggested an association between take-home doses and increased retention in treatment. There was no evidence of an association between take-home doses and illicit substance use or overdose. Qualitative findings indicated that take-home doses reduced clients’ exposure to unregulated substances and stigma and minimized work/treatment conflicts. Though some clients reported challenges with managing their medication, the dominant narrative was one of appreciation, reduced anxiety, and a renewed sense of agency and identity. The integrated analysis suggested reduced treatment burden as an explanation for improved retention and revealed variation in individual relationships between take-home doses and illicit substance use. We identified a critical gap in quantitative measures of patient-important outcomes.

Conclusion

The relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses was associated with improved client experience and retention in OAT. We found no evidence of an association with illicit substance use or overdose, despite the expansion of take-home doses to previously ineligible groups. Including patient-important outcome measures in policy, program development, and treatment planning is essential to ensuring that decisions around take-home doses accurately reflect their value to clients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13011-023-00564-9.

Keywords: Substance use, Opioid use disorder, Opioid agonist treatment, COVID-19

Introduction

Opioid use disorder affects an estimated 21.4 million people worldwide [1]. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, attributable in part to the stigmatization, social marginalization, and criminalization of people who access the unregulated drug supply [2, 3]. Regionally, opioid use disorder is most prevalent in high-income North America [4]. In 2022, a total of 83,827 deaths in the United States and 7,328 deaths in Canada were attributed to opioid toxicity [5, 6]. This is a substantial increase over 2016, when 43,149 deaths were reported in the United States and 2,831 in Canada [5, 6]. The severity of the overdose crisis in this region of the world is the result of historical overprescribing, social factors, and an unregulated drug supply that is heavily contaminated with fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and other adulterants [7–9].

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) using methadone or buprenorphine is an effective and well-established approach to reducing the harms associated with opioid use disorder [10–13]. Both methadone and buprenorphine suppress use of unregulated opioids when prescribed at adequate doses [11, 14] and are associated with substantial reductions in rates of fatal and non-fatal overdose [13, 15]. Despite these benefits, retention in OAT is low; it ranges from 19 to 86% at six months, with a median retention rate of 58% [16]. Mortality rates rise steeply after treatment cessation [13].

Burdensome treatment conditions, particularly for clients on methadone, may contribute to low retention in OAT [17]. These conditions commonly include supervised dosing, in which OAT clients must travel to their clinic or pharmacy each day so that their medication can be ingested under the observation of a health care provider [18]. Take-home doses, which can be carried out of the clinic and stored safely elsewhere, may be granted to clients who meet specific criteria.

In the United States, pre-pandemic guidelines for methadone programs required clients to meet eight criteria reflecting ‘stability’ and to remain in treatment for a minimum of six months before becoming eligible to receive more than two take-home doses per week [19]. Factors affecting eligibility for take-home OAT in other jurisdictions include time in treatment, abstinence from illicit substance use, housing stability, distance from the treatment facility, and provider discretion [18, 20].

Restrictions on take-home doses are driven by concerns over the potential for diversion, injection, and overdose [21]. Methadone is approached with particular caution; as a full agonist with a long half-life, it has the potential to cause serious respiratory depression if taken in excess or in conjunction with alcohol, unregulated opioids, or other sedatives [21]. For this reason, careful titration is necessary to initiate methadone safely. However, systematic reviews of supervised versus unsupervised dosing have found insufficient evidence to determine whether restrictions on take-home doses are effective in reducing diversion [22, 23]. Recent research has drawn attention to the role of unmet treatment need in the market for diverted medication [24–26] and highlighted the potential for benefits as well as harms [27, 28].

Though some OAT clients appreciate the structure of daily supervised dosing [29, 30], inflexible restrictions on take-home doses have repeatedly been identified as a source of dissatisfaction with treatment [31]. In addition to “[obstructing] the basic day-to-day functioning of life” [32] (p. S118), supervised dosing has been described as humiliating, degrading, and stigmatizing [29, 33, 34]. Commentators have argued that supervised dosing is part of a treatment paradigm that reinforces institutional stigma and power imbalances, serving as a form of social control as well as a medical intervention [35–38].

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses on an unprecedented scale. The risks of viral infection to clients and providers in medical settings, as well as the dangers of treatment discontinuation for clients who might stop OAT to avoid exposure to COVID-19, were deemed to outweigh the potential harms of take-home doses. Regulations and guidelines to encourage use of take-home doses during the pandemic were developed in Canada [39], the United States [40, 41], Australia [42], England [43], Spain [44], Italy [45], and India [46]. Other changes to OAT during COVID-19 included the suspension of urine testing or a reduction in testing frequency, increased emphasis on naloxone distribution, medication delivery for clients in isolation or quarantine, and the use of virtual care in place of in-person visits [39, 41–43, 45, 46]. Though implementation of the new flexibilities around take-home doses varied [47], their introduction created an unparalleled opportunity to assess the impact of relaxing restrictions on take-home doses in OAT.

Previous reviews of changes to take-home guidance during COVID-19 have focused on providers’ experiences [48] and changes within the United States [49]. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of international scope to focus on how relaxing restrictions on take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic affected program effectiveness and client experiences in OAT. Results from this study can support clinicians, policymakers, and stakeholders in making informed decisions around the implementation and expansion of take-home doses in OAT.

Methods

Design

We conducted a mixed methods systematic review to address the following questions:

Q1 (quantitative): What was the impact of relaxing restrictions on take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic on program effectiveness in OAT, as defined by (1) retention; (2) illicit substance use; (3) fatal and non-fatal overdose; (4) client health (e.g., measures of physical, mental, or emotional health); (5) quality of life; and (6) treatment satisfaction?

Q2 (qualitative): What was the impact of relaxing restrictions on take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic on clients’ experiences with OAT?

Q3. What are the integrated findings of Q1 and Q2, and what are their implications for OAT?

Mixed methods approaches have the potential to generate a more complete and nuanced understanding of a phenomenon than quantitative or qualitative evidence alone. Qualitative evidence can suggest explanations for quantitative findings, help policymakers predict the impact of an intervention in a specific context, and illuminate aspects of human experience that are not captured by quantitative research [50]. We used a convergent segregated approach in which the quantitative synthesis (Q1) and qualitative synthesis (Q2) are conducted separately before being integrated through ‘configured analysis’ (Q3) [51]. Reporting of the methods was guided by the PRISMA and PRISMA-S statements for reporting systematic reviews and the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline [52–54] (Additional file 1). The protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022352310; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Search strategy

We used the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) and PICo (Population, phenomenon of Interest, Context) frameworks to structure our search strategy and define our inclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

PICO and PICo criteria for review questions Q1 and Q2

| Q1: What was the impact of relaxing restrictions on take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic on program effectiveness in OAT, as indicated by (1) retention; (2) illicit substance use; (3) fatal and non-fatal overdose; (4) client health; (5) quality of life; and (6) treatment satisfaction? | P (Population): People receiving OAT via any route of administration (e.g., oral, sublingual, buccal, injectable) |

| I (Intervention): Relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses of OAT during the COVID-19 pandemica | |

| C (Comparator): (1) No comparator OR (2) restrictions on take-home doses prior to the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| O (Outcomes): Program effectiveness, as indicated by incidence of (1) retention; (2) illicit substance use; (3) fatal and non-fatal overdose; (4) client health; (5) client quality of life; and (6) client treatment satisfaction | |

| Q2: What was the impact of relaxing restrictions on take-home doses during the COVID-19 pandemic on clients’ experiences with OAT? | P (population): People receiving OAT via any route of administration (e.g., oral, sublingual, buccal, injectable) |

| I (phenomenon of Interest): Client experience (e.g. satisfaction with treatment, relationship with provider, self-efficacy, alignment of service with personal treatment goals, other patient-reported outcomes) | |

| Co (Context): Relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses of OAT during the COVID-19 pandemica |

Abbreviations: OAT opioid agonist treatment

aAs specified in the review protocol, we included studies in which relaxed restrictions on take-home doses formed part of a broader intervention or context

The search strategy was developed by a member of the research team with expertise in systematic searching (AA) and reviewed by a professional research librarian. Substantive elements of the search strategy for this review were used in a previously published review [48]. We restricted all searches to articles published after January 1, 2020 because the review focuses on actions taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We searched six electronic databases and registers on Aug. 26, 2022 to retrieve peer-reviewed literature: Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost), PsycInfo (EBSCOhost), Web of Science Core Collection (Web of Science), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Ovid). See Additional file 2 for a sample search strategy. We conducted a grey literature search of selected websites and databases from Oct. 27–Nov. 7, 2022. We conducted forward and backward citation chaining from Dec. 1–2, 2022. We updated the searches through an additional round of forward citation chaining conducted on Mar. 31, 2023. Full search strategies can be found in the OSF data repository [55].

Screening, data extraction, and critical appraisal

We imported all searches into Covidence, an online platform for supporting systematic reviews [56]. Screening, data extraction and critical appraisal were completed in Covidence by two reviewers working independently and blinded to each other’s assessments (AA, SB, RF, TM). See Table 2 for eligibility criteria used in screening. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer (JL, SB). We used a standardized, pre-piloted form to extract information on study characteristics and findings, including geographical region, study aim, study design, and sample characteristics.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria used to screen studies

| Inclusion Criteria |

| For all studies: |

|

• Includes findings on the impact of relaxed restrictions on take-home doses of opioid agonist medication for opioid use disorder, either alone or in conjunction with other interventions/exposures, during the Covid-19 pandemic on program effectiveness in opioid agonist treatment • Written in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, or Italian |

| For quantitative component: |

|

• A randomized or non-randomized study reporting quantitative data OR a mixed methods study where the quantitative component can be cleanly extracted • Assesses one or more of the following client outcomes: (1) Retention in treatment, using any quantitative measure; (2) illicit substance use, using any quantitative measure; (3) fatal and non-fatal overdose, using any quantitative measure; (4) client health, using any quantitative measure; (5) client quality of life, using any quantitative measure; (6) client satisfaction with treatment, using any quantitative measure |

| For qualitative component: |

|

• A qualitative study using any qualitative approach (e.g., grounded theory, critical theory, ethnography) OR a mixed methods study where the qualitative component can be cleanly extracted • Includes findings on OAT clients’ experiences with relaxed restrictions on take-home doses of OAT during the Covid-19 pandemic |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| For all studies: |

|

• OAT clients are a subgroup of the study population, but findings specific to this group cannot be extracted; • Take-home doses intended to be supervised remotely or in person (e.g., witnessed daily delivery; take-homes witnessed through videoconferencing systems) • Commentaries, editorials, or letters to the editor, unless original empirical research is presented • Conference abstracts, posters, or slide decks, unless meeting three predefined conditions designed to limit retrieval to relevant studies for which sufficient information can be obtained • The study is a preprint that has become available in peer-reviewed form |

| For qualitative component: |

| • The study uses quantitative methods (e.g., questionnaires, fixed-choice surveys) to collect qualitative data |

Acronyms: OAT opioid agonist treatment

We used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 to appraise study quality and validity [57]. The MMAT is designed specifically for mixed methods systematic reviews. We used the results of the appraisal to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence base and conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding low-quality studies, which we defined as studies meeting fewer than three of five criteria on the MMAT.

Quantitative synthesis

For the quantitative synthesis, we grouped study findings by outcome to improve comparability. We did not conduct meta-analysis or summarize effect estimates because the diversity of outcome measures precluded calculation of a common effect estimate. Nor was it possible to summarize p-values with the data available. Instead, we synthesized data using vote counting based on direction of effect to answer the question “Is there any evidence of an effect?” [58, 59]. This method is an acceptable alternative to meta-analysis when it is not possible to calculate a standardized estimate of effect, as is often the case in reviews of complex interventions [58–60]. For each outcome, we compared the number of studies showing a beneficial effect with the number showing a harmful effect. As per guidance, we did not take statistical significance or magnitude of effect into account [59].

When a study used more than one measure for the same outcome, we used Boon & Thomson’s revised method [58] to determine the overall direction of effect supported by the study. If the direction of effect was the same (e.g., all beneficial or all harmful) for ≥ 70% of measures, we considered this the overall direction of effect. We recorded the direction as mixed if less than 70% of measures reported a consistent effect direction. We described the results of the synthesis using harvest plots displaying direction of effect, study quality, and sample size [61–63].

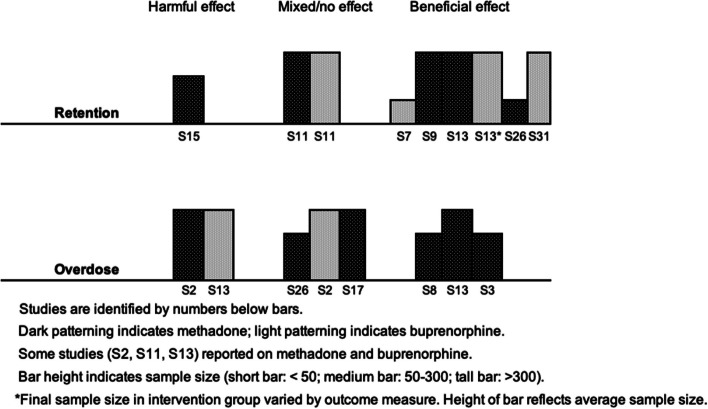

We planned to investigate heterogeneity through subgroup analyses based on treatment type (buprenorphine, which had considerably fewer restrictions on take-home doses before the pandemic, versus methadone) and on race and ethnicity. However, formal statistical investigation was not feasible because of insufficient data. Where possible, we explored the effects of treatment type through informal methods; more specifically, through visual inspection of harvest plots in which studies were shaded according to treatment type (methadone vs. buprenorphine).

Qualitative synthesis

We synthesised qualitative findings using thematic synthesis, which consists of (1) coding studies line-by-line; (2) grouping codes into descriptive themes; and (3) integrating the descriptive themes into analytical themes that address the review question more directly [64]. Thematic synthesis preserves a clear audit trail from data to analytical themes, making it particularly suitable for systematic reviews [65].

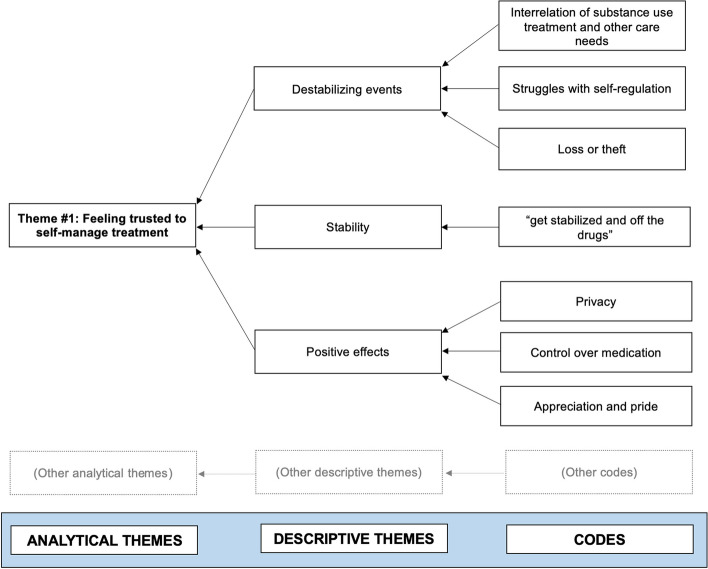

Two members of the research team (AA, SB) coded the same four studies line-by-line in NVivo 1.7 [66]. AA and SB compared and reconciled their coding to create a set of codes and descriptive themes that were used to code/re-code all studies (AA, SB). After coding was completed, AA and SB discussed conceptual links between the descriptive themes and generated analytical themes. These themes were then reviewed with a third member of the research team (EOJ). See Fig. 1 for an illustration of theme development.

Fig. 1.

Example of the development of an analytical theme. For visual simplicity, only descriptive themes and codes contributing to Theme #1 are shown

Certainty of evidence

There is no consensus around whether appraising the certainty of the evidence is appropriate in mixed methods reviews, with some organizations supporting this step [67] and others advising against [51]. Methodologists have raised concerns about the use of GRADE and similar methods in mixed methods reviews because of the complexities and uncertainties around incorporating these assessments into the integrated findings of the review [51, 68]. In light of these concerns, we did not formally appraise the certainty of the evidence supporting the qualitative or quantitative findings.

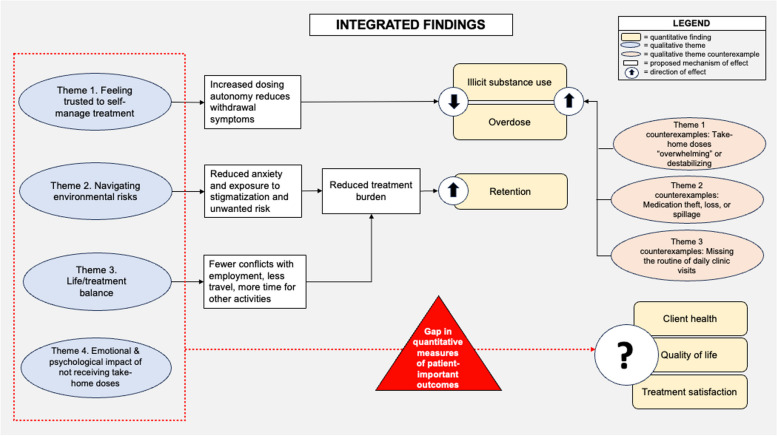

Integrated analysis

To develop the integrated analysis, we juxtaposed the qualitative and quantitative syntheses and considered how they might complement, explain, or contextualize each other [51]. After drafting the analysis, we discussed our preliminary findings with seven community members with lived experience of OAT to help us assess the credibility of our findings and inform further interpretation.

Results

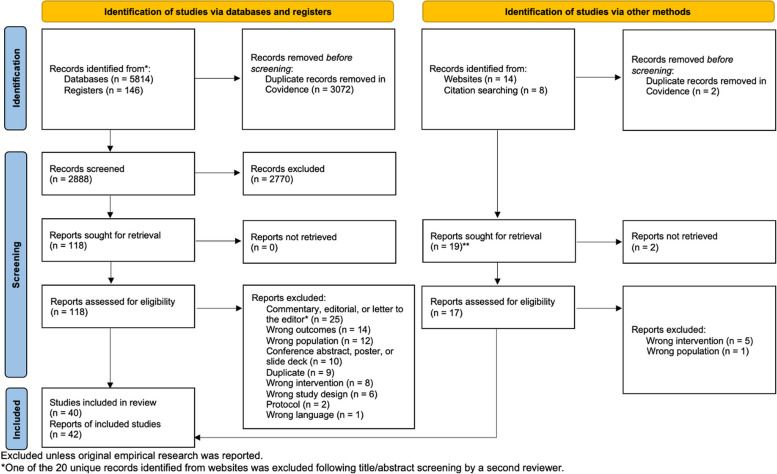

After excluding duplicates, we retrieved 2,888 records from databases and registers and 20 records from citation chaining and the grey literature search. Of these, 42 records (representing 40 studies) met our eligibility criteria and were included in the review [69–110] (hereafter referred to as S1–S40; see Table 3) (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies

| No | Study | Region | Aima | Study Design | Start of Data Collection | End of Data Collection | Q1 Findings (Quant.) | Q2 Findings (Qual.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Abidogun et al., 2023b [69] | United States | To explore (1) the impact of COVID-19-related changes to methadone treatment, including increased take-home doses, on patients; and (2) the experience of patients with virtual counselor meetings | Qualitative study | Mar. 2021 | Jun. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S2 | Aldabergenov et al., 2022 [70] | United Kingdom (England) | To investigate methadone- and buprenorphine-related deaths in people prescribed and not prescribed OAT after the first COVID-19 lockdown and compare trends to those observed in prior years | Before-and-after study | Jan. 2016 | Jun. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S3 | Amram et al., 2021 [71] | United States | To evaluate the effects of a COVID-19-related increase in methadone take-home doses on outcomes for MOUD clients | Before-and-after study | May 2019 | Dec. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S4 | Bart et al., 2022 [72] | United States | To explore the impact of COVID-19-related changes to methadone take-home doses on drug use | Before-and-after study | Jul. 2019 | Jul. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S5 | Conway et al., 2023 [73] | Australia | To explore how adaptations to OAT provision “impacted and responded to the risk environments of people receiving OAT during the COVID-19 pandemic” (p. 2) | Qualitative study | Aug. 2020 | Dec. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S6 | Corace et al., 2022 [74] | Canada | To assess "(1) which patients received additional unsupervised doses during the pandemic; (2) the outcomes of unsupervised dosing [...]; and (3) patients' and prescribers' experiences with changes in OAT care delivery" (p. 2) | Cross-sectional study | Aug. 2020 | Sept. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S7 | Cunningham et al., 2022 [75] | United States | To understand how COVID-19-related changes in health care policies and health care delivery impacted buprenorphine treatment outcomes | Cohort study | Mar. 2019 | Dec. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S8 | Ezie et al., 2022 [76] | United States | To investigate changes in medication adherence, illicit substance use, rates of infection, and mortality following SAMHSA's relaxation of take-home guidelines for methadone treatment | Before-and-after study | Dec. 2019 | Jun. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S9 | Farid et al., 2022 [77] | Bangladesh | NR | Before-and-after study | Jul. 2019 | Mar. 2021 | Yes | No |

| S10 | Gage et al., 2022 [78] | Online community (Reddit) | "to investigate the lived experience of PWUD during the COVID-19 pandemic" (p. 1505) | Qualitative study | Mar. 2020 | Jun. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S11 | Garg et al., 2022 [79] | Canada | To investigate the impact of COVID-19, [including the] subsequent change in OAT guidance, on OAT discontinuation" (p. 2) | Time series study | Apr. 2019 | Nov. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S12 | Gittins et al., 2022 [80] | United Kingdom (England) | To explore over-the-counter and prescription drug misuse among SMS [substance misuse services] clients during COVID-19 | Mixed methods (qualitative/cross-sectional) | Aug. 2020 | Aug. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S13 | Gomes et al., 2022 [81] | Canada | "to evaluate whether increased access to take-home doses of OAT related to pandemic specific guidance was associated with changes in treatment retention and opioid-related harms" (p. 847) | Cohort study | Feb. 2020 | NR | Yes | No |

| S14 | Harris et al., 2022 [82] | United States | "to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted MOUD and addiction service experiences." (p. 2) | Qualitative study | Aug. 2020 | Oct. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S15 | Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | United States | "to assess patients' responses to the enhanced access to take-home methadone" (p.2) | Mixed methods (qualitative/before-and-after) | Sept. 2019 | Dec. 2020 | Yes | Yes |

| S16 | Javakhishvili et al., 2021 [84] | Western Georgia (Eurasia) | To study treatment satisfaction and quality of life among people in opioid substitution therapy (OST) programs in western Georgia [during the COVID-19 pandemic] | Mixed methods (qualitative/cross-sectional) | NR; data collection "during pandemic" | NR; data collection "during pandemic" | Yes | Yes |

| S17 | Joseph et al., 2021 [85] | United States | The original research presented in this commentary was conducted "to ascertain outcomes" of new approach to take-home dosing following SAMHSA's relaxation of take-home guidelines for methadone treatment | Before-and-after study | Jan. 2020 | May 2020 | Yes | No |

| S18 | Kesten et al., 2021 [86] | United Kingdom | To understand how people who inject drugs experienced COVID-19-related public health measures and changes to opioid substitution treatment and harm reduction services | Qualitative study | Jun. 2020 | Aug. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S19 | Krawczyk et al., 2021 [87] | Online community (Reddit) | To explore views on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on various aspects of treatment for opioid use disorder | Qualitative study | Mar. 2020 | NR | No | Yes |

| S20 | Levander et al., 2021 [88] | United States | To investigate patients' perceptions of the impact of COVID-19-related changes to take-home methadone policies and to investigate how these changes affected treatment access, recovery, and mental health support for rural patients | Qualitative study | Aug. 2020 | Jan. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S21 | Liddell et al., 2021 [89] | United Kingdom (Scotland) | "to provide a baseline of current MAT [medication-assisted treatment] provision, prior to implementation [of new treatment standards], from the perspective of people currently in treatment" (p. 6). [Includes experiences with increased take-home doses during the pandemic] | Mixed methods (qualitative/cross-sectional) | Dec. 2020 | May 2021 | No | Yes |

| S22 | Lintzeris et al., 2022 [90] | Australia | To describe COVID-19-related changes to OAT service delivery and to examine changes in patient outcomes following the implementation of the changes | Before-and-after study | Dec. 2019 | Sept. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S23 | May et al., 2022 [91] | United Kingdom | To "[investigate] the longer-term impacts of the pandemic on the health and wellbeing [...] of PWID, as well as their experiences of treatment changes from the perspectives of both PWID and service providers" (p. 2) | Qualitative study | May 2021 | Sep. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S24 | Meyerson et al., 2022 [92] | United States | "To understand patient experience of federal regulatory changes governing methadone and buprenorphine (MOUD) access in Arizona during the COVID-19 pandemic" (p. 1) | Qualitative study | Aug. 2021 | Oct. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S25 | Morin et al., 2021 [93] | Canada | "to present a Canadian perspective on increased fentanyl positive urine drug screen results among OAT patients during the COVID-19 pandemic." (p. 2) | Time series study | Jan. 2020 | Sept. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S26 | Nguyen et al., 2021c [94] | United States | "to understand the impact of the expanded eligibility for take-home MOUD dosing, including benefits and unintended consequences" (p. 3) | Mixed methods (qualitative/before-and-after and cohort data) | Jan. 2019 | Dec. 2020 | Yes | Nob |

| S27 | Nobles et al., 2021 [95] | Online community (Reddit) | To address the knowledge gap around "the perspectives and experiences of OTP [opioid treatment program] patients during the COVID-19 pandemic [...] we qualitatively examine self-reported impacts to the delivery of MMT." (p. 2135) | Qualitative study | Jan. 2020 | Sept. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S28 | Parkes et al., 2021 [96] | United Kingdom (Scotland) | To explore how program staff and PWLLE have experienced COVID-19 related changes to services for people experiencing homelessness and problem substance use | Qualitative study | Apr. 2020 | Aug. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S29 | Pilarinos et al., 2022 [97] | Canada | "to identify policy related factors that can be addressed to improve OAT experiences and outcomes among young people, and we provide new insights into how OAT programming can be optimized to meet young peoples' needs and goals." (p. 2). [Includes experiences with COVID-19-related changes to take-home dosing] | Qualitative study | Jan. 2018 | Aug. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S30 | Rosic et al., 2022 [98] | Canada | "1. To determine whether opioid use increased, decreased, or remained unchanged during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients already enrolled in MAT; 2. To explore factors associated with a change in the percentage of opioid-positive urine drug screens (UDSs) for patients followed both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic." (p. e258) | Before-and-after study | Jun. 2019 | Nov. 2020 | Yes | No |

| S31 | Roy et al., 2023 [99] | United States | To evaluate "national changes in buprenorphine access as a result of COVID-19-related prescribing guideline changes up to one-year post-initial-pandemic period" (p. 2) | Time series study | Feb. 2019 | Apr. 2021 | Yes | No |

| S32 | Russell et al., 2021 [100] | Canada | "to understand how service disruptions during COVID-19 may have affected PWUD" (p. 2) | Qualitative study | May 2020 | Jul. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S33 | Schofield et al., 2022 [101] | United Kingdom (Scotland) | To explore "the impacts of COVID-19 related changes on the availability and uptake of health and care services, particularly harm reduction, treatment, recovery, and general healthcare services, among PWUD in Scotland during the pandemic" (p. 2) | Qualitative study | May 2020 | Nov. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S34 | Scott et al., 2023 [102] | United Kingdom (England) | To investigate how people with OUD experienced changes to substance use treatment during COVID-19 and to explore their views on improving OAT delivery | Qualitative study | NR | NR | No | Yes |

| S35 | Suen et al., 2022/Wyatt et al., 2022 [104] | United States | "to describe the MOUD treatment experiences of patients and providers at an OTP [opioid treatment program] in San Francisco, California, to inform [post-COVID-19] research and policy" (p. 1148) | Qualitative study | Aug. 2020 | Nov. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S36 | University of Bath et al., 2020, 2021 [106] | England | "to understand how people in receipt of OST [opioid substitution treatment] in rural areas have experienced the pandemic changes [to treatment]." (p. 2) | Qualitative study | NR | Mar. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S37 | Vicknasingam et al., 2021 [107] | Malaysia | To evaluate how people who use drugs and service providers adapted to and coped with COVID-19-related public health measures and associated changes to treatment | Qualitative study with before-and-after quantitative data | Dec. 2019 | Aug. 2020 | Yes | Yes |

| S38 | Walters et al., 2022 [108] | United States | To examine how COVID-19 and COVID-19 mitigation strategies "affected the lives of people who use drugs in relation to MOUD" (p. 1145) | Qualitative study | Jun. 2020 | Oct. 2020 | No | Yes |

| S39 | Watson et al., 2022 [109] | United States | "[to investigate] how individuals with OUD understood and navigated treatment and their personal recoveries during the COVID-19 pandemic" (p. 2) | Qualitative study | Sept. 2020 | Jan. 2021 | No | Yes |

| S40 | Zhen-Duan et al., 2022 [110] | United States | "to understand (1) how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted low-income individuals with SUD [substance use disorder] and (2) how people adjusted to SUD treatment changes during stay-at-home orders in NYC [New York City]" (p. 1105) | Qualitative study | Apr. 2020 | Jun. 2020 | No | Yes |

aAcronyms: MMT methadone maintenance treatment, MOUD medication for opioid use disorder, NR not reported, OAT opioid agonist treatment, OUD opioid use disorder, PWID people who inject drugs, PWLLE people with lived and living experience [of substance use], PWUD people who use drugs, SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration

bQualitative findings were extracted from a preprint version of this manuscript. Comparison with the peer-reviewed publication showed no appreciable changes to the data extracted for this review

cQualitative findings from this mixed-methods preprint were later published in peer-reviewed form (Suen et al., 2022/Wyatt et al., 2022) and were therefore not extracted from the preprint

Fig. 2.

PRISMA diagram

Study characteristics

Most studies were from the United States (16/40), the United Kingdom (9/40), or Canada (7/40). Twenty-four studies included participants on a variety of OAT medications. Fourteen focused exclusively on methadone clients and two were limited to buprenorphine clients. For additional details on study design and participant characteristics, see Tables 3 and 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of participants in included studies

| No | Study | Samplea | No. of OAT Clients in Sample | Opioid Medication(s) Used | Ageb | Sex | Race and Ethnicitye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Abidogun et al., 2023 [69] | 28 clients from a community-based opioid treatment program serving a low-income population in Baltimore, Maryland | 28 | Methadone | 50 (10) |

Female: 43% Male: 57% |

White: 39% Black/African American: 57% American Indian: 4% |

| S2 | Aldabergenov et al., 2022 [70] | 529 deceased adults prescribed and not prescribed OAT treatment for opioid use disorder in England | NR | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S3 | Amram et al., 2021 [71] | 183 MOUD clients at an opioid treatment program in Spokane County, Washington | 183 | Methadone | 41 (median), 32–51 (IQR) |

Female: 58% Male: 42% |

Non-Hispanic White: 73% Other: 18% |

| S4 | Bart et al., 2022 [72] | 613 clients at the Hennepin Healthcare Addiction Medicine opioid treatment program in Minnesota | 613 | Methadone | 49 (14) |

Female: 49% Male: NR |

Caucasian: 46% Black: 23% American Indian: 15% Asian: 9% Latinx: < 1% |

| S5 | Conway et al., 2023 [73] | 40 OAT clients and 28 OAT providers in Australia | 40 | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR | NR | NR |

| S6 | Corace et al., 2022 [74] | 402 OAT clients prescribed OAT and 100 OAT prescribers in Ontario.d | 402 | Buprenorphine, methadone, slow-release oral morphine | 18–59 (range) |

Female: 44% Male: 54% Trans and/or GE: 2% |

White– European or North American: 78% Black – African, Caribbean, or North American: 11% First Nations, Inuit, or Metis: 7% Asian – East or South East: 2% Latin American: 1% Mixed heritage: < 1% Prefer not to respond: < 1% |

| S7 | Cunningham et al., 2022 [75] | 107 people referred for buprenorphine treatment at Montefiore Buprenorphine Treatment Network in the Bronx (NY, USA) | 81 | Buprenorphine | 46 (14) |

Female: 33% Male: NR |

Hispanic: 52% Non-Hispanic Black: 20% Non-Hispanic White: 18% Non-Hispanic other or unknown: 10% |

| S8 | Ezie et al., 2022 [76] | 129 clients at a methadone maintenance treatment program in New York | 129 | Methadone | 66 (median), 32–79 (range) |

Female: 1% Male: 99% |

Non-Hispanic Black/African American: 40% Non-Hispanic White: 28% Hispanic or Latino: 25% American Indian/Alaska Native: 2% Unknown: 5% |

| S9 | Farid et al., 2022 [77] | PWID receiving opioid substitution treatment at 35 centers in Bangladesh | NR | Methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S10 | Gage et al., 2022 [78] | 100 posters on four Reddit subforums related to substance use | NR | Buprenorphine, methadone | 16 (7)c |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S11 | Garg et al., 2022 [79] | 63,941 clients receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone in Ontario | 63,941 | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S12 | Gittins et al., 2022 [80] | 56 clients receiving substance use care at two community treatment centres/providers in England | 35 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 39 (mean), 18–61 (range) |

Female: 41% Male: 59% |

White—British: 95% White – Irish: 4% White – Other: 2% |

| S13 | Gomes et al., 2022 [81] | 21,297 people receiving OAT in Ontario | 21,297 | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR [only subgroup data reported] | NR [only subgroup data reported] | NR |

| S14 | Harris et al., 2022 [82] | 20 Boston site participants from a parent study (REBOOT) on preventing opioid overdose | 14 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 42 (mean), 27–61 (range) |

Female: 45% Male: 50% Trans and/or GE: 5% |

White: 80% Other or more than one race: 20% |

| S15 | Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | 377 methadone clients at two opioid treatment programs serving five Southern Oregon rural counties | 377 | Methadone | 40 (11) |

Female: 49% Male: 51% |

Non-Hispanic White: 93% |

| S16 | Javakhishvili et al., 2021 [84] | 100–668 clients from OST institutions in Western Georgia (Eurasia) | Quant: 668, Qual.: 10 | Buprenorphine, methadone |

43 (median) [quant. participants], 48 (6) [qual. participants] |

Female: 10% Male: 90% |

NR |

| S17 | Joseph et al., 2021 [85] | > 3,600 opioid treatment program clients at five clinics in the Bronx | > 3,600 | Methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S18 | Kesten et al., 2021 [86] | 28 people who use drugs in Bristol, England | 23 | Buprenorphine, methadone |

25–29: 7% 30–34: 14% 35–39: 36% 40–44: 18% 45–49: 11% 50–54: 14% |

Female: 32% Male: 68% |

NR |

| S19 | Krawczyk et al., 2021 [87] | Posters on the subreddits r/Opiates and r/OpiatesRecovery | NR | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S20 | Levander et al., 2021 [88] | 46 clients at three rural opioid treatment programs in Oregon | 46 | Methadone | 44 (13) |

Female: 50% Male: 50% |

White: 96% American Indian/Alaska Native: 13% Hispanic/Latinx: 4% |

| S21 | Liddell et al., 2021 [89] | 95 MAT clients from six health boards across Scotland | 90 | Buprenorphine, methadone |

24–34: 25% 35–44: 53% 45–54: 16% 55–64: 5% Missing: 1% |

Female: 43% Male: 56% |

White – Scottish: 96% White – British: 6% White – English: 3% |

| S22 | Lintzeris et al., 2022 [90] | 429 clients enrolled on OAT at three public treatment service locations in Sydney | 429 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 43 (10) |

Female: 33% Male: NR |

NR |

| S23 | May et al., 2022 [91] | 19 PWID recruited through drug and homelessness services in London and Bristol | NR | Methadone | 40 (mean), 24–49 (range) |

Female: 53% Male: 47% |

White British: 68% Black or Black British Caribbean: 11% White and Black Caribbean: 11% White Other: 11% |

| S24 | Meyerson et al., 2022 [92] | 131 MOUD clients from 29 different providers in rural and urban communities across Arizona | 131 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 38 (11) |

Female: 38% Male: 71% Trans and/or GE: 2% |

White: 68% Hispanic: 24% Black: 3% Native American: 3% Asian: 2% |

| S25 | Morin et al., 2021 [93] | 14,669 clients from 67 OAT clinics in Ontario | 14,669 | Buprenorphine, methadoneg | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S26 | Nguyen et al., 2021f [94] | 506 clients at a hospital-affiliated opioid treatment program in San Francisco, California | 506 | Methadone | 48 (11) |

Female: NR Male: 77% |

White: 51% Black/African American: 32% Hispanic: 10% Other: 7% |

| S27 | Nobles et al., 2021 [95] | 179 posters on the subreddit r/methadone | NR | Methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S28 | Parkes et al., 2021 [96] | 10 people with lived/living experience of homelessness who used services at the Wellbeing Centre, as well as staff and stakeholders | NR | Methadoneg | NR |

Female: 20% Male: 80% |

NR |

| S29 | Pilarinos et al., 2022 [97] | 56 young current or former OAT clients in Vancouver | NR | Buprenorphine, methadone, slow-release oral morphineg | 14–24 (range) |

Female: 32% Male: 64% Trans and/or GE: 4% |

White: 75% Indigenous: 23% Asian-Canadian: 9% African-Canadian: 5% Declined to answer: 4% |

| S30 | Rosic et al., 2022 [98] | 629 OAT clients from 31 clinics in Ontario | 629 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 40 (11) | Female: NR Male: 50% | NR |

| S31 | Roy et al., 2023 [99] | Individuals prescribed buprenorphine in the U.S. between Feb. 2019 and Apr. 2021 |

Time point 1: 1,269,651 Time point 2: 814,013 Time point 3: 1,329,502 |

Buprenorphine |

Time point 1: 41 (12) Time point 2: 42 (13) Time point 3: 42 (12) |

Varied; 43–44% | NR |

| S32 | Russell et al., 2021 [100] | 196 people who use drugs from across Canada | 72 | Buprenorphine, methadone, “intravenous OAT” | 41 (11) |

Female: 41% Male: 56% Trans and/or GE: 4% |

White: 59% Indigenous: 30% Other: 11% |

| S33 | Schofield et al., 2022 [101] | 29 people who use drugs recruited from a hostel/shelter, a stabilization and housing service, a harm reduction service, and a peer-led recovery community in Scotland | NR | Buprenorphine, methadoneg | 28–56 (range) |

Female: 45% Male: 55% |

NR |

| S34 | Scott et al., 2023 [102] | 27 people receiving OAT at a community addictions centre in London | 27 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 47 (NR) |

Female: 19% Male: 82% |

White British: 52% Black British: 15% Other: 33% |

| S35 | Suen et al., 2022/Wyatt et al., 2022 [104] | 20 MOUD patients and 10 providers at one OTP in San Francisco, California | 20 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 51 (median), 41–60 (IQR) |

Female: 47% Male: 53% |

Black/African American: 47% Hispanic/Latinx: 26% White: 26% Native American/American Indian: 11% |

| S36 | University of Bath et al., 2020, [105] | 15 people receiving OST in rural villages and towns in Somerset, Wiltshire, and Suffolk | 15 | Methadoneg | 43 (mean), 31–56 (range) |

Female: 53% Male: 47% |

NR |

| S37 | Vicknasingam et al., 2021 [107] | Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clients and personnel at MMT programs, HIV clinics, and NGO services in the Malaysian states of Penang, Kelantan, Selangor, and Melaka | Quant.: 74, Qual.: 9 | Methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S38 | Walters et al., 2022 [108] | 37 people who use drugs recruited from the Northeast US; 18 MOUD providers, clinic staff, and regulatory officials | NR | Buprenorphine, methadone | NR |

Female: NR Male: NR |

NR |

| S39 | Watson et al., 2022 [109] | 25 people referred to MOUD in Chicago, Illinois, within the year prior to or after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic | 20 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 57 (mean), 48–74 (range) |

Female: 76% Male: 24% |

African American: 96% Hispanic/Latino: 4% |

| S40 | Zhen-Duan et al., 2022 [110] | 20 adults enrolled in Medicaid and receiving outpatient SUD treatment (e.g., medication, counseling) in NYC | 13 | Buprenorphine, methadone | 52 (13) |

Female: 20% Male: 80% |

Black non-Latinx: 25% Asian non-Latinx: 20% Black Latinx: 10% White Latinx: 10% Multiracial non-Latinx: 5% Multiracial Latinx: 5% Latinx, no race selected: 25% |

aAcronyms: GE gender-expansive, IQR interquartile range, NR not reported, SD standard deviation

bAges presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise specified. All ages are rounded to the nearest year

cBased on 53 posts reporting age

dPrescriber data excluded from sample characteristics

eRace and ethnicity were initially extracted in dichotomized form (White/Non-White) to facilitate subgroup analysis. As subgroup analysis was not possible, one reviewer (AA) subsequently extracted a more detailed breakdown of the ‘Non-White’ category using the terms used in the original studies. All figures are rounded to the nearest percent. Some figures sum to more than 100% because of rounding and/or selection of multiple race and ethnicity categories

fQualitative findings from this mixed-methods preprint were later published in peer-reviewed form (Suen et al., 2022/Wyatt et al., 2022) and were therefore not extracted. Sample characteristics in this table are based on participants in the quantitative analysis

gInferred from type of treatment facility, general description of treatment, or participant quotes; may not be exhaustive list of participants’ medications

Eighteen studies contributed data to the quantitative synthesis. As specified in our review protocol, we included studies in which the relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses formed part of a broader intervention or exposure. Other pandemic-related changes to OAT described in the quantitative studies included increased use of telehealth and virtual care (S2, S6, S7, S11, S13, S22, S30, S31), reduced in-person appointments (S6, S7, S11, S13, S15–17, S22), cessation or reduced frequency of urine testing (S2, S6, S11, S17, S22, S37), home delivery of medication for clients who were self-isolating and/or at high risk (S7, S22, S30), rapid or remote protocols for OAT induction (S2, S30, S31), and increased naloxone provision (S7, S22). Of the 18 studies, nine were intended to assess only the impact of changes to take-home policies. Five of these studies (S3, S4, S13, S15, S22) used methods to control for the impact of co-exposures or other factors associated with the receipt of take-home doses (e.g., regression modelling) in their analysis. Six studies defined their intervention of interest as pandemic-related changes to OAT, including, but not limited to, increased take-home doses. Two studies defined their exposure/intervention as the pandemic together with associated changes to OAT.

Twenty-five studies contributed to the qualitative synthesis. Three focused exclusively on OAT clients’ experiences with take-home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many were designed to explore participants’ experiences with any and all pandemic-related changes to OAT (15/25). A smaller number explored how people who use drugs experienced life during the pandemic (7/25). Though all studies met our inclusion criteria, some contributed little data to the synthesis.

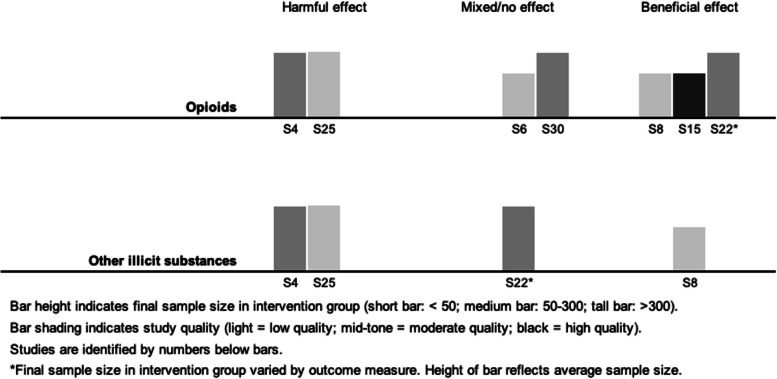

Quantitative synthesis

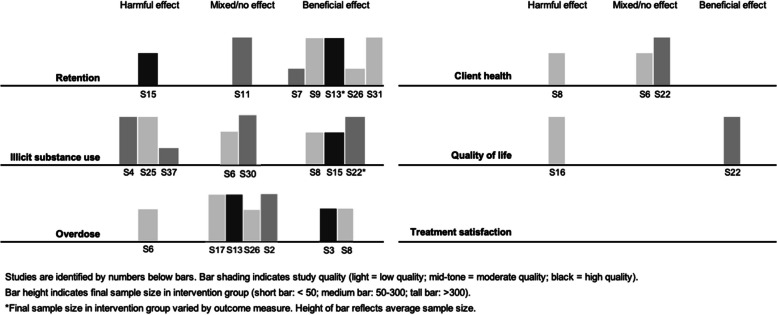

Visual inspection of harvest plots (see Fig. 3) suggested an association between take-home doses and improved retention, but showed no clear evidence of an association with overdose or illicit substance use. The small number of studies reporting client health or quality of life precluded meaningful synthesis. We did not identify any studies reporting treatment satisfaction. Brief narrative summaries are provided below.

Fig. 3.

Harvest plots showing results of synthesis by direction of effect

Retention

Seven studies reported measures of retention, including one finding a negative direction of effect (S15), one with mixed direction of effect (S11), and five supporting a positive direction of effect (S7, S9, S13, S26, S31). See Table 5. Two were high-quality (S13, S15), two were moderate-quality (S7, S11), and three were low-quality (S9, S26, S31). Our main concerns about the quality of studies contributing to this outcome were failure to account for confounding, unplanned co-interventions, and generalizability (Table 6).

Table 5.

Studies reporting measures of retention

| Study | Measure | Control Group | Intervention Group | Statistical Test or Model | p-value | Estimate of Effect | Direction of Effect | Overall Effect Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S7) Cunningham et al., 2022 [75] | Retention in treatment at 90 daysa | 42.9%b | 68.0%c | Chi square or Fisher exact test | < 0.05 | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| (S9) Farid et al., 2022 [77] | “Retention” | 68.1%d |

(a) 72.9% (b) 82.7% (c) 87.3%e |

NR | NR | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| (S11) Garg et al., 2022 [79] | Immediate changef in weekly prevalence of treatment discontinuation following intervention among clients stable on OAT | NA | NA | Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model | 0.93 | Step change: -0.01% (95% CI -0.14–0.12%) | Favours intervention | Mixed |

| Gradual changeg in weekly prevalence of treatment discontinuation following intervention among clients stable on OAT | NA | NA | Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model | 0.72 | Slope change: 0.00% (95% CI -0.01–0.02%) | No difference | ||

| Immediate changef in weekly prevalence of treatment discontinuation following intervention among clients not stable on OAT | NA | NA | Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model | 0.82 | Step change: -0.31% (-3.04–2.43%) | Favours intervention | ||

| Gradual changeg in weekly prevalence of treatment discontinuation following intervention among clients not stable on OAT | NA | NA | Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model | 0.63 | Slope change: 0.04% (95% CI: -0.12–0.20%) | Favours control | ||

| (S13) Gomes et al., 2022 [81] | OAT discontinuationh among people receiving daily methadone at baseline | 63.6% per person-yeari | 51.0% per person-yearj | Cox proportional-hazards model | < 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.80 (95% CI: 0.72–0.90) | Favours intervention | Positive |

| OAT discontinuationh among people receiving 5–6 take-home doses of methadone at baseline | 19.6% per person-yeari | 14.1% per person-yearj | Cox proportional-hazards model | < 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.72 (95% CI 0.62–0.84) | Favours intervention | ||

| OAT discontinuationh among people receiving daily buprenorphine/naloxone at baseline | 93.2% per person-yeari | 85.1% per person-yearj | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.91 (95% CI 0.68–1.22) | Favours intervention | ||

| OAT discontinuationh among people receiving 5–6 take-home doses of buprenorphine/naloxone at baseline | 30.8% per person-yeari | 26.0% per person-yearj | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.85 (95% CI 0.70–1.01) | Favours intervention | ||

| (S15) Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | Treatment discontinuation among people in treatment < 90 days | 13%k | 26%l | Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.047 | NR | Favours control | Negative |

| Treatment discontinuation among people in treatment 90–180 days | 9.4%k | 19%l | Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.090 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Treatment discontinuation among people in treatment > 180 days | 11%k | 12%l | Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.7 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Odds of treatment discontinuation per percentage point in take-home dosing above expectedm | NR | NR | Random effects logistic regression model | 0.003 | Adjusted OR: 0.97 (95% CI 0.95, 0.99) | Favours intervention | ||

| (S26) Nguyen et al., 2021 [94] | 60-day retention among new intakes | 63%k | 69%l | Two-tailed t-test | 0.26 | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| (S31) Roy et al., 2023 [99] | Treatment disruptions among stably treated clientsn at 1 week post-initial pandemic period | 1.3%k | NR | Segmented regression interrupted time series model | < 0.05 |

Relative change from baseline trend: (a) Disruptions ≥ 7 days: -12.6 (95% CI: -16.6,-8.5) (b) Disruptions ≥ 14 days: -9.7 (95% CI: -15.1,-4.3) (c) Disruptions ≥ 28 days: -11.6 (95% CI: -14.7,-8.5) |

Favours intervention | Positive |

| Treatment disruptions among stably treated clientsn at 26 weeks post-initial pandemic period | 1.0%k | NR | Segmented regression interrupted time series model | < 0.05 |

Relative change from baseline trend: (a) Disruptions ≥ 7 days: -17.0 (95% CI: -19.4,-14.6) (b) Disruptions ≥ 14 days: -10.2 (95% CI: -15.7,-4.8) (c) Disruptions ≥ 28 days: -15.5 (95% CI: -18.9,-12.1) |

Favours intervention | ||

| Treatment disruptions among stably treated clientsn at 52 weeks post-initial pandemic period | 0.6%k | NR | Segmented regression interrupted time series model | < 0.05 |

Relative change from baseline trend: (a) Disruptions ≥ 7 days: -21.6 (95% CI: -25.6,-17.7) (b) Disruptions ≥ 14 days: -10.8 (95% CI:-16.3,-5.3) (c) Disruptions ≥ 28 days: -27.3 (95% CI:-33.0,-21.6) |

Favours intervention |

Where adjusted and unadjusted effect estimates were reported, we present adjusted estimates. Where weighted and unweighted effect estimates were reported, we present weighted estimates. In no case did this change the estimated direction of effect

Acronyms: HR hazard ratio, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, RR relative risk

*Not reported in the original study; inferred or calculated by authors

aRetention defined as active buprenorphine prescription at least 90 days after treatment initiation

bControl group: OAT clients initiating treatment after referral before pandemic

cIntervention group: OAT clients initiating treatment after referral during pandemic

dControl group: OAT clients from Jul.–Dec. 2019

eIntervention groups: OAT clients from (a) Jan.-Jun. 2020, (b) Jul.-Dec. 2020, and (c) Jan.-Mar. 2021

fThe step transfer function was used to test for immediate change

gThe ramp transfer function used to test for gradual change

hOAT discontinuation defined as a gap in therapy exceeding 14 days

iControl group: OAT clients with no change in take-home doses during pandemic

jIntervention group: OAT clients with increased take-home doses during pandemic

kControl group: OAT clients pre-pandemic

lIntervention group: OAT clients post-pandemic

mAnalysis limited to OAT clients with at least three months of pre-pandemic data and one month of post-pandemic data

n “Stable clients” defined as clients with six months or more of buprenorphine prescriptions without a treatment disruption. “Treatment disruptions” defined as gaps of 28 days

Table 6.

Critical appraisal of quantitative studies reporting retention

| No | Study | MMAT Section 3a for quantitative non-randomized studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Are the participants representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis?b | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended?b | ||

| S7 | Cunningham et al., 2022 [75] | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| S9 | Farid et al., 2022 [77] | Yes | No | Can't tell | No | No |

| S11 | Garg et al., 2022 [79] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| S13 | Gomes et al., 2022 [81] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S15 | Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S26 | Nguyen et al., 2021 [94] | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| S31 | Roy et al., 2023 [99] | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | No | No |

| # meeting quality criteria | 4/7 | 6/7 | 5/7 | 2/7 | 3/7 | |

aThe MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) Qualitative Checklist is designed specifically for mixed methods systematic reviews (Hong et al., 2018). It consists of five sections specific to various study designs, each with five quality criteria. All quantitative studies included in this review, including quantitative components of mixed-methods studies, were appraised under Sect. 3: Quantitative non-randomized studies

bThis review included studies in which the intervention of interest (relaxed restrictions on take-home doses) formed part of a broader intervention (e.g., pandemic-related changes to OAT treatment). To increase the relevancy of the quality assessments, we interpreted questions 4 and 5 relevant to the research question posed in this review

Negative direction

A before-and-after study (S15) found that treatment discontinuation increased following the relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses, regardless of time in treatment. However, logistic regression showed that the odds of treatment discontinuation decreased with each additional take-home dose.

Mixed direction

The overall direction of effect was mixed in a study using statistical modelling to test for changes in OAT discontinuation after pandemic-related treatment changes (S11). Though there was an immediate decrease in treatment discontinuation for all clients, tests for gradual changes showed no change among stable clients and a negative trend for non-stable clients.

Positive direction

Five studies reported a positive direction of effect (S7, S9, S13, S26, S31). A cohort study of buprenorphine clients (S7) found that clients referred to treatment during the pandemic, when prescription durations increased, had a higher rate of retention at 90 days than clients referred prior to the pandemic. Another cohort study (S13) assessed the risk of OAT discontinuation in a sample stratified by treatment type and number of take-home doses at baseline. In all four subgroups, clients who received additional take-home doses during COVID-19 had a lower risk of treatment discontinuation. Two before-and-after studies reported increased retention following the relaxation of restrictions on take-home doses (S9, S26), and a time series study using data on buprenorphine prescriptions in the United States (S31) reported a reduction in treatment disruptions of 28 days or more during the pandemic.

Illicit substance use

Eight studies reported measures of illicit substance use, including three supporting a negative direction of effect (S4, S25, S37), two with mixed direction of effect (S6, S30), and three finding a positive direction of effect (S8, S15, S22). See Table 7. One study was high-quality (S15), four were moderate-quality (S4, S22, S30, S37), and three were low-quality (S6, S8, S25). Most studies supporting this outcome were downgraded for concerns about unplanned co-interventions, failure to account for confounders, and generalizability (see Table 8).

Table 7.

Studies reporting measures of illicit substance use

| Study | Measure | Control Group | Intervention Group | Statistical Test or Model | p-value | Estimate of Effect | Direction of Effect | Overall Effect Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S4) Bart et al., 2022 [72] | Urine test positive for opiates without confirmed prescription | 14%a | 22%b | NR | < 0.001 | NR | Favours control | Negative |

| Urine test positive for amphetamines without confirmed prescription | 10%a | 16%b | NR | < 0.001 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for barbiturates without confirmed prescription | 0.2%a | 0.3%b | NR | p ≥ 0.001 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for benzodiazepines without confirmed prescription | 6.3%a | 11%b | NR | < 0.001 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for cocaine without confirmed prescription | 11%a | 12%b | NR | p ≥ 0.001 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for oxycodone without confirmed prescription | 2.6%a | 3.2%b | NR | p ≥ 0.001 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for opioids (opiates or oxycodone) without confirmed prescription | NRa | NRb | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | OR: 2.34 (95% CI 1.78–3.07) | Favours control | ||

| Urine test positive for non-opioids without confirmed prescription | NRa | NRb | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | OR: 2.48 (95% CI 1.89–3.25) | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for opioids among clients with 1–2 take-home doses/week | 0.435c | 0.202d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Proportion drug tests positive for opioids among clients with 3–5 take-home doses/week | 0.187c | 0.226d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for opioids among clients with 6 take-home doses/week | 0.060c | 0.121d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for opioids among clients with > 6 take-home doses/week | 0.027c | 0.036d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for non-opioids among clients with 1–2 take-home doses/week | 0.587c | 0.398d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Proportion drug tests positive for non-opioids among clients with 3–5 take-home doses/week | 0.187c | 0.377d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for non-opioids among clients with 6 take-home doses/week | 0.119c | 0.161d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Proportion of drug tests positive for non-opioids among clients with > 6 take-home doses/week | 0.049c | 0.040d | Generalized linear mixed model | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| (S6) Corace et al., 2022 [74] | OAT clients reporting increase in opioid use "since COVID-19 (March 2020)" | 46%e | 28%f | NR | NR | NR | Favours intervention | Mixed |

| OAT clients reporting decrease in opioid use "since COVID-19 (March 2020)" | 21%e | 14%f | NR | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| (S8) Ezie et al., 2022 [76] | Urine drug screens positive for opiates | 39%a | 36%b | Multiple logistic regression | > 0.05 | Adjustedg OR: 0.82 (0.34–1.98) | Favours intervention | Positive |

| Urine drug screens positive for any non-prescribed substance other than cannabis | 45%a | 40%b | Multiple logistic regression | > 0.05 | Adjustedg OR: 0.61 (0.25–1.48) | Favours intervention | ||

| (S15) Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | Random monthly urine drug tests positive for opioids among clients in treatment for < 90 days | 38% (SD 0.43)a | 33% (SD 0.42)b | Wilcoxon rank sum test, Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.6 | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| Random monthly urine drug tests positive for opioids among clients in treatment for 90–180 days | 19% (SD 0.34)a | 33% (SD 0.43)b | Wilcoxon rank sum test, Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.041 | NR | Favours control | ||

| Random monthly urine drug tests positive for opioids among clients in treatment for > 180 days | 23% (SD 0.33)a | 20% (SD 0.32)b | Wilcoxon rank sum test, Pearson's Chi-squared test | 0.12 | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Expected change in random monthly urine drug test positivity per percentage point in take-home dosing above expectedh | NR | NR | Linear regression | 0.005 | Slope: -0.12 (95% CI -0.21, -0.04) | Favours intervention | ||

| (S22) Lintzeris et al., 2022 [90] | Any self-reported cannabis use | 33%a | 38%n | McNemar test | 0.028 | χ2: 4.817 | Favours control | Positive |

| Any self-reported benzodiazepine use | 28%a | 22%n | McNemar test | 0.014 | χ2: 6.017 | Favours intervention | ||

| Any self-reported stimulant use | 20%a | 16%n | McNemar test | 0.120 | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Any self-reported opioid use | 30%a | 24%n | McNemar test | 0.033 | χ2: 4.563 | Favours intervention | ||

| Any self-reported injection drug use | 29%a | 22%n | McNemar test | 0.077 | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Average days used among clients self-reporting cannabis use |

Mean: 18.1 (SD 10.8) Median: 21a |

Mean 18.0 (SD 11.0), Median 26b | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | 0.020 | Z: -2.331 | Favours control | ||

| Average days used among clients self-reporting benzodiazepine use | Mean: 14.6 (SD 11.7) Median: 12a | Mean: 16.9 (SD 11.4) Median: 20b | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | NR | NR | Favours control | ||

| Average days used among clients self-reporting stimulant use | Mean: 6.5 (SD 8.2) Median: 3a | Mean: 5.9 (SD 7.4) Median: 3b | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| Average days used among clients self-reporting opioid use | Mean: 12.2 (SD 10.7) Median: 8a | Mean: 7.9 (SD 9.1) Median: 4b | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | 0.001 | Z: -3.445 | Favours intervention | ||

| Average days used among clients self-reporting injection drug use | Mean: 10.7 (SD 10.5) Median: 5a | Mean: 8.1 (SD 8.9) Median: 4b | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | 0.010 | Z: 2.577 | Favours intervention | ||

| Percentage of clients with “statistically reliable” and “clinically relevant” increase in substance use (composite measure)i | 43%j |

(a) 40%k (b) 17%l |

Logistic regression |

(a) p ≥ 0.05* (b) p < 0.05* |

Adjusted OR: (a) 0.854 (0.39–1.87) (b) 0.273 (0.10–0.77) |

Favours intervention | ||

| (S25) Morin et al., 2021 [93] | Routine urine drug screens positive for fentanyl |

Jan: 14% Feb: 13% Mar: 14%a |

Apr: 12% May: 21% Jun: 26% Jul: 29% Aug: 29% Sep: 25%b |

Fractional logistic regression | NR |

OR: (a) Apr. vs. Jan: 0.9 (95% CI: 0.8–0.9) (b) May vs. Jan.: 1.7 (95% CI: 0.5–1.89) (c) Jun. vs. Jan.: NR (d) Jul. vs. Jan: NR (e) Aug. vs. Jan: 2.6 (95% CI: 2.3–2.9) (f) Sep vs. Jan: 2.2 (95% CI: 1.9–2.6) |

Favours controlm | Negative |

| Routine urine drug screens positive for cocaine |

Jan: 24% Feb: 24% Mar: 24%a |

Apr: 23% May: 29% Jun: 28% Jul: 28% Aug: 26% Sep: 25%b |

NR | NR | NR | Favours controln | ||

| Routine urine drug screens positive for methamphetamine |

Jan: 18% Feb: 19% Mar: 20%a |

Apr: 17% May: 23% Jun: 23% Jul: 18% Aug: 17% Sep: 19%b |

NR | NR | NR | Favours controln | ||

| Routine urine drug screens positive for morphine |

Jan: 13% Feb: 13% Mar: 13%a |

Apr: 12% May: 15% Jun: 15% Jul: 15% Aug: 15% Sep: 15%b |

NR | NR | NR | Favours controln | ||

| Routine urine drug screens positive for oxycodone |

Jan: 6% Feb: 6% Mar: 6%a |

Apr: 6% May: 7% Jun: 7% Jul: 6% Aug: 6% Sep: 6%b |

NR | NR | NR | Favours controln | ||

| (S30) Rosic et al., 2022 [98] | Percentage of opioid-positive urine drug screens | Mean: 7.5% (SD 17.2)a | Mean: 18.1% (SD 26.5)b | Paired t-test | p < 0.001 | Risk difference: 10.56% (95% CI: 8.17–12.95) | Favours control | Mixed |

| Percentage of clients with any opioid-positive urine drug screens | 73.5%a | 46.3%b | NR | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| (S37) Vicknasingam et al., 2021 [107] | Percentage of clients with urine toxicology tests positive for any illicit substance |

Dec.: 23% Jan.: 23% Feb.: 18%a |

Jun.: 24% Jul.: 19%b |

NR | NR | NR | Favours controln | Negative |

Where adjusted and unadjusted effect estimates were reported, we present adjusted estimates. In no case did this change the estimated direction of effect

Acronyms: NR not reported, OR odds ratio. Where bivariate and multivariate analyses were reported, we present the results of the multivariate analysis

*Not reported in the original study; inferred or calculated by authors

aControl group: OAT clients pre-pandemic

bIntervention group: OAT clients post-pandemic

cControl group: 2019 values from a fitted model that removed the main effect of year to “[capture] the effect of change in take-out schedule” (Bart et al., 2022, p. 3)

dIntervention group: 2020 values from a fitted model that removed the main effect of year

eControl group: All OAT clients

fIntervention group: OAT clients with additional take-home doses during pandemic

gAdjusted for years in treatment, age, substance use disorder diagnosis, psychiatric disorder diagnosis, and % reduction in visit frequency

hAnalysis limited to clients with three months of pre-COVID-19 data and one month of post-COVID-19 data

iDefined as an increase of 4 or more days in the previous 28 days

jControl group: OAT clients with no take-home doses at follow up

kIntervention group (a): OAT clients with 1–5 take-home doses/week at follow up

lIntervention group (b): OAT clients with 6 + take-home doses/week at follow up

mBased on proportion of comparisons favouring control

nBased on mean control group value versus mean intervention group value

Table 8.

Critical appraisal of quantitative studies reporting illicit substance use

| No | Study | MMAT Section 3a for quantitative non-randomized studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Are the participants representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis?b | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended?b | ||

| S4 | Bart et al., 2022 [72] | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| S6 | Corace et al., 2022 [74] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| S8 | Ezie et al., 2022 [76] | Yes | Can't tell | Yes | No | Can't tell |

| S15 | Hoffman et al., 2022 [83] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S22 | Lintzeris et al., 2022 [90] | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| S25 | Morin et al., 2021 [93] | Yes | Yes | Can't tell | No | No |

| S30 | Rosic et al., 2022 [98] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| S37 | Vicknasingam et al., 2021 [107] | Can't tell | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| # meeting quality criteria | 3/8 | 6/8 | 7/8 | 3/8 | 2/8 | |

aThe MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) Qualitative Checklist is designed specifically for mixed methods systematic reviews (Hong et al., 2018 [57]). It consists of five sections specific to various study designs, each with five quality criteria. All quantitative studies included in this review, including quantitative components of mixed-methods studies, were appraised under Sect. 3: Quantitative non-randomized studies

bThis review included studies in which the intervention of interest (relaxed restrictions on take-home doses) formed part of a broader intervention (e.g., pandemic-related changes to OAT treatment). To increase the relevancy of the quality assessments, we interpreted questions 4 and 5 relevant to the research question posed in this review

Negative direction

One time series study (S25) and two before-and-after studies (S4, S37) found an increase in the percentage of positive urine tests among OAT clients following pandemic-related treatment changes. One study (S4) used statistical modelling to examine whether urine test positivity was associated with number of take-home doses, but found no clear association.

Mixed direction

A cross-sectional study (S6) reported that clients receiving additional take-home doses during the pandemic were less likely to report increased or decreased opioid use since COVID-19. In a before-and-after study (S30), the total percentage of positive urine tests among OAT clients increased following the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the percentage of clients testing positive decreased.

Positive direction

Three before-and-after studies (S8, S15, S22) reported a decrease in the percentage of positive urine tests (S8, S15) or self-reported substance use (S22) following pandemic-related treatment changes. In one study (S15), a linear regression analysis limited to clients in treatment for at least three months before the pandemic found that the probability of a positive urine test decreased as take-home doses increased.

Fatal and non-fatal overdose

Seven studies reported measures of fatal and/or non-fatal overdose. The direction of effect was negative in one study (S6), mixed in four studies (S2, S13, S17, S26), and positive in two studies (S3, S8). See Table 9. Two studies were high-quality (S3, S13), one was moderate-quality (S2), and four were low-quality (S6, S8, S17, S26). Areas of concern included failure to account for confounding, unplanned co-interventions, and generalizability (see Table 10).

Table 9.

Studies reporting measures of fatal and non-fatal overdose

| Study | Measure | Control Group | Intervention Group | Statistical Test or Model | p-value | Estimate of Effect | Direction of Effect | Overall Effect Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S2) Aldabergenov et al., 2022 [70] | Methadone-related deaths among people prescribed methadone | 44 (95% CI: 37–50)a | 55b | NR | ≥ 0.05* | NR | Favours control | Mixed |

| Buprenorphine-related deaths among people prescribed buprenorphine |

2016: 1 2017: 1 2018: 1 2019: 1c |

2020: 1d | NR | NR | NR | None | ||

| (S3) Amram et al., 2021 [71] | Emergency department visits related to overdose | 16e | 15f | Chi-square, McNemar’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test | 1 | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| Odds of emergency department visit per one-dose difference in total take-home doses after regulatory changes | NR | NR | Generalized linear model with binary logistic function | 1.73 | Adjusted OR: 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | Favours intervention | ||

| (S6) Corace et al., 2022 [74] | Self-reported opioid overdose(s) with or without emergency department visit | 13%g | 16%h | Chi square test | 0.54 | χ2: 0.37 | Favours control | Negative |

| (S8) Ezie et al., 2022 [76] | “Overdose”, details not specified | 2%e | 0.7%f | Chi square test | > 0.05 | NR | Favours intervention | Positive |

| (S13) Gomes et al., 2022 [81] | Non-fatal opioid overdosesi among clients receiving daily methadone at baseline | 9.5% per person-yeark | 6.9%/person-yearl | Cox proportional-hazards model | < 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.73 (95% CI: 0.56–0.96) | Favours intervention | Mixed |

| Non-fatal opioid overdosesi among clients receiving 5–6 take-home doses of methadone at baseline | 1.8%/person-yeark | 1.4%/person-yearm | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.80 (95% CI: 0.50–1.28) | Favours intervention | ||

| Fatal opioid overdosesj among clients receiving daily methadone at baseline | 0.5% per person-yeark | 0.6%/person-yearl | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 1.26 (95% CI: 0.48–3.33) | Favours control | ||

| Fatal opioid overdosesj among clients receiving 5–6 take-home doses of methadone at baseline | 0.3%/person-yeark | NRm,n | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 0.48 (95% CI: 0.16–1.45) | Favours intervention | ||

| Non-fatal opioid overdosesi among clients receiving daily buprenorphine/ naloxone at baseline | 3.5%/person-yeark | 6.5%/person-yearm | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 1.86 (95% CI: 0.70–4.92) | Favours control | ||

| Non-fatal opioid overdosesi among clients receiving 5–6 take-home doses of buprenorphine /naloxone at baseline | 1.4%/person-yeark | 1.7%/person-yearm | Cox proportional-hazards model | ≥ 0.05* | Weighted HR: 1.23 (95% CI: 0.58–2.63) | Favours control | ||

| (S17) Joseph et al., 2021 [85] | Non-fatal overdoseso | 2e | 6f | NR | NR | NR | Favours control | Mixed |

| Fatal overdoseso | 1e | 0f | NR | NR | NR | Favours intervention | ||

| (S26) Nguyen et al., 2021 [94] | Fatal overdosest among clients “established” in care without take-home doses at baseline | 0.5%q | 0.6%r | NR | ≥ 0.05* | NR | Favours control | Mixed |

| Fatal overdosesp among clients “established” in care with take-home doses at baseline | 4.1%s | 0.8%t | NR | ≥ 0.05* | NR | Favours intervention |

Where adjusted and unadjusted effect estimates were reported, we present adjusted estimates. Where weighted and unweighted effect estimates were reported, we present weighted estimates. In no case did this change the overall estimated direction of effectAcronyms: HR hazard ratio, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, RR relative risk

*Not reported in the original study; inferred or calculated by authors

aControl group: Projected deaths of methadone clients, Mar.-Jun. 2020

bIntervention group: Actual deaths of methadone clients, Mar.–Jun. 2020

cControl group: Buprenorphine clients, 2016–2019

dIntervention group: Buprenorphine clients, 2020

eControl group: OAT clients pre-pandemic

fIntervention group: OAT clients post-pandemic

gControl group: OAT clients without additional take-home doses during pandemic

hIntervention group: OAT clients with additional take-home doses during pandemic

i ≥ 1 emergency department visit or inpatient hospitalization for opioid toxicity

jCoroner-confirmed fatal opioid overdoses

kControl group: OAT clients without additional take-home doses during pandemic

lIntervention group: OAT clients with additional take-home doses (any number) during pandemic

mIntervention group: Clients with additional take-home doses (at least a two-week supply) during pandemic

nCould not be modelled because of small numbers

oOverdoses reported to clinical personnel or documented in medical records

pFatal overdoses ascertained from electronic health records; defined as death [over 10-month follow-up period] with any or multiple illicit substances (including opioids) listed as any of the potential causes of death

qControl group: Clients who never had take-home doses (neither before nor during pandemic)

rIntervention group: Clients newly started on take-home doses during pandemic

sControl group: Clients with no change or a decrease in take-home doses during pandemic

tIntervention group: Clients with additional take-home doses during pandemic

Table 10.

Critical appraisal of quantitative studies reporting fatal and non-fatal overdose

| No | Study | MMAT Section 3a for quantitative non-randomized studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Are the participants representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis?b | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended?b | ||

| S2 | Aldabergenov et al., 2022 [70] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| S3 | Amram et al., 2021 [71] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| S6 | Corace et al., 2022 [74] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |