Abstract

Objectives:

Clinical observations and studies of retrospective observer ratings point to changes in personality in persons with cognitive impairment or dementia. The timing and magnitude of such changes, however, are unclear. This study used prospective self-reported data to examine the trajectories of personality traits before and during cognitive impairment.

Design:

Longitudinal observational cohort study.

Setting and Participants:

Older adults from the United States in the Health and Retirement Study were assessed for cognitive impairment and completed a measure of the five major personality traits every four years from 2006 to 2020 (N = 22,611; n = 5,507 with cognitive impairment; 50,786 personality and cognitive assessments).

Methods:

Multilevel modeling examined changes before and during cognitive impairment, accounting for demographic differences and normative age-related trajectories.

Results:

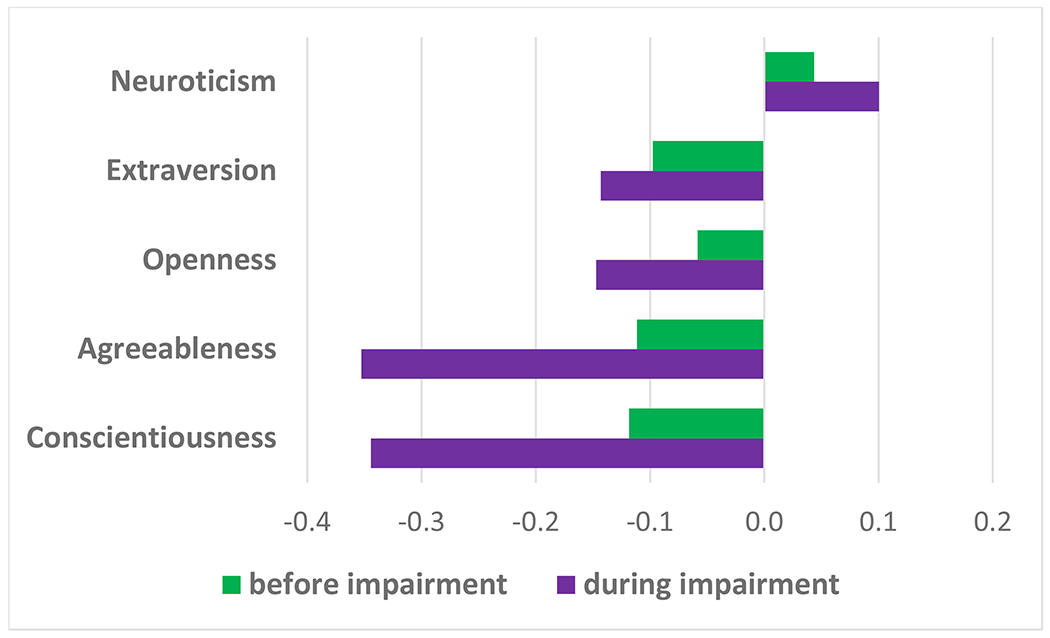

Before detected cognitive impairment, extraversion (b=−.10, SE=.02), agreeableness (b=−.11, SE=.02), and conscientiousness (b=−.12, SE=.02) decreased slightly; there was no significant change in neuroticism (b=.04, SE=.02) or openness (b=−.06, SE=.02). During cognitive impairment, faster rates of change were found for all five personality traits: neuroticism (b=.10, SE=.03) increased, and extraversion (b=−.14, SE=.03), openness (b=−.15, SE=.03), agreeableness (b=−.35, SE=.03), and conscientiousness (b=−.34, SE=.03) declined.

Conclusions and Implications:

Cognitive impairment is associated with a pattern of detrimental personality changes across the preclinical and clinical stages. Compared to the steeper rate of change during cognitive impairment, the changes were small and inconsistent before impairment, making them unlikely to be useful predictors of incident dementia. The study findings further indicate that individuals can update their personality ratings during the early stages of cognitive impairment, providing valuable information in clinical settings. The results also suggest an acceleration of personality change with the progression to dementia, which may lead to behavioral, emotional, and other psychological symptoms commonly observed in people with cognitive impairment and dementia.

Keywords: Personality, dementia, cognitive impairment, longitudinal, preclinical, prodromal

Brief summary:

Analyses of longitudinal data from 22611 older adults found detrimental personality changes in people with cognitive impairment. Personality changes were smaller and less consistent before cognitive impairment.

Introduction

Since the first case described by Alois Alzheimer, personality changes have been prominent in characterizing Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). Consistent with early reports, current diagnostic criteria recognize behavioral and personality changes as a core clinical criterion for the diagnosis of dementia1. Clinical observations are largely consistent with research2 based on standardized measures of the five major dimensions of personality (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness)3. Although personality changes are commonly observed in individuals with dementia2, there are conflicting reports on the exact timing and magnitude of change before and during the early stages of cognitive impairment (i.e., mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia)4–9. Identifying the pattern of change in the pre-symptomatic or preclinical stage (i.e., before cognitive impairment) and in subsequent prodromal (e.g., MCI) and early stages of dementia has implications for understanding the natural evolution of the disease. More detailed knowledge of dementia-related personality change can inform clinicians, patients, and their families about the impact of the disease on fundamental psychological traits. Further, research on personality changes can complement evidence that ADRD pathology accumulates in the brain years before the appearance of clinical symptoms10, and during the preclinical stage personality traits are related to β-amyloid, tau, and markers of neurodegeneration (e.g., glial fibrillary acidic protein - GFAP-, and neurofilament light -NfL)11, 12.

Research that uses retrospective, observer-ratings by family members of the person with dementia has found remarkably consistent patterns of personality change across studies2, 13–18. The differences between premorbid and current ratings point to large (≥1SD) increases in neuroticism and decreases in extraversion and conscientiousness. These changes in persons with dementia are more than ten-fold larger than changes with normal aging19. A similar pattern has been observed in individuals with MCI17, but the magnitude was considerably smaller (~0.25 SD)2. With a retrospective pre-post design, however, these studies are not well suited to identify the exact timing and rates of change.

Several longitudinal studies with self-rated personality traits have examined personality change in people transitioning to MCI or dementia. An early 12-year longitudinal study (n=66 with MCI), found no significant changes in any of the five major personality traits4. A later 7-year study (n=25 with MCI) assessed personality before and during MCI and found significant increases in neuroticism, declines in openness, and no significant changes in extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness5. Similar increases in neuroticism have been reported for four other samples of persons who developed MCI or dementia (range n=43 to 183)6–8. These studies used a variety of research designs and analytic methods, but generally included personality assessed before and during impairment (i.e., at the time of diagnosis or later). This approach makes it difficult to distinguish changes that occurred before impairment from those that occurred during cognitive impairment. To our knowledge, only one 36-year prospective study examined changes specifically before the onset of impairment (n = 359 MCI or dementia), and found no evidence that individuals who later developed MCI or dementia had patterns of personality change that differed from those who remained cognitively healthy9.

Using one of the largest samples to date, this study aimed to advance knowledge on personality changes related to cognitive impairment. The primary focus was on distinguishing between the changes that occur before and during the early stages of cognitive impairment and dementia, while accounting for demographic differences and normative age-related trajectories. This study had no pre-registered hypotheses. Consistent with clinical observations and previous observer rating studies2, 13–18, we hypothesized that persons who develop cognitive impairment would report detrimental personality changes (increases in neuroticism and declines in the other four traits). We also expected a steeper rate of change as the disease progresses. In other words, we expected smaller rates of personality change before than during cognitive impairment.

Methods

Sample:

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is a national sample of Americans aged 50 years or older and their spouses, regardless of age. The HRS data are publicly available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the HRS research protocol. Written consent was obtained from all participants. Spouses younger than 50 were excluded from this study because dementia is less common at younger ages. Individuals who had proxies answer the personality items were also excluded. Participants with at least one assessment of personality and cognition, and with basic demographics (age and gender), were included in this study. The personality test was first administered to a random half of the HRS sample in 2006; the other half completed the personality inventory for the first time in 2008. The personality assessment repeats every four years, and this study used all available data, up to 2020. Cognitive status was assessed at every wave. New participants were recruited in the HRS to replenish the cohort, and we examined all data regardless of when the first assessment occurred.

Personality assessment:

The Midlife Development Inventory20 is a validated, self-report measure of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Respondents rated how much 26 adjectives described them on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). Internal consistency across the five traits was α = 0.75 for intact cognition, α = 0.70 for cognitive impairment not dementia (CIND), and α = 0.72 for dementia, which suggests that comprehension of items was adequate even among impaired participants21.

Cognitive assessment:

Cognitive status was assessed at each wave and classified with the modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICSm)22, 23. The TICSm overall score (range 0 to 27) is based on immediate and delayed recall of 10 nouns (0 to 20 points), serial 7 subtraction (0 to 5 points), and backward counting (0 to 2 points). HRS classifies individuals who scored ≤6 in the dementia group, 7 to 11 in the CIND group, and 12 to 27 in the normal cognitive group23. These cut-off values were validated by comparisons with clinical diagnoses in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), a substudy of the HRS, and have been used in many studies of cognitive aging and dementia23–28.

The current study defined cognitive impairment as a score ≤11. Those who scored 12 to 27 were classified as cognitively unimpaired. Participants who scored in the impaired range at one wave but in the normal range at the following wave were classified as unimpaired. The results were similar when participants were coded as impaired regardless of cognitive status at the following wave.

Statistical analyses:

We calculated means and SD or proportions for study variables. Missing data for education were coded with the sample mean (13 years), and missing data for race/ethnicity were coded as white. One participant with missing data on gender and other variables was excluded from the analyses.

The primary analyses used multilevel modeling29 given the hierarchical structure of the data with measurement occasions (Level 1) nested within persons (Level 2). The model included terms for the intercept and slope, specifically sample means (fixed effects) and individual deviations from the means (random effects). Time invariant variables included age at baseline (centered at age 63 and divided by ten to scale coefficients per decade), age squared, sex, race (one dummy coded variable for Black/African American and one dummy coded variable for race other than Black and White), ethnicity (Latinx vs. other), and education in years. These demographic variables were included because past research has shown associations with both personality and risk of dementia.

Multiple time-variant variables were included to capture within-person changes in personality overall and before and during cognitive impairment. First, to capture normative personality change over time, we coded “time” in years, starting from the first personality assessment (e.g., 0 for the first assessment, .4 for a second assessment 4 years later, and so on; one unit corresponds to one decade for all time-related variables). Time squared was included to account for potential quadratic slopes, and a time-by-age interaction to account for differences in the slope as people age. Second, we coded a “Before-CI” (CI=cognitive impairment) variable with negative values for waves leading to cognitive impairment (e.g., −.4 for personality assessments completed 4 years before the wave at which participant scored cognitively impaired) and 0 at waves in which participants were impaired; note that this metric does not model change at the wave in which the participant became impaired. Third, we coded a “During-CI” variable to track time from the first wave at which participants were cognitively impaired (e.g., .4 for personality assessments completed 4 years after the wave at which participants scored as cognitively impaired) and coded 0 for the pre-impairment waves. Figure 1 provides an example of how data were coded. Nonimpaired participants were the reference group and the “Before-CI” and “During-CI” variables were coded 0 at all waves. The personality traits were standardized to facilitate comparisons across traits. The codes for the models tested are in supplementary material.

Figure 1.

Example of coding of the time variables.

Given the large sample size and the five traits tested, we used a more conservative p < .01 to decrease the risk of chance findings, and we focused more on effect sizes than statistical significance when interpreting the findings. We further accounted for multiple testing using Benjamini and Hochberg’s false discovery rate method.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Descriptive statistics for the total sample and by cognitive status are in Table 1. At the first assessment, age ranged from 50 to 104 years (M=64.79, SD=10.40) and years of education ranged from 0 to 17 years (M=12.76, SD=3.13). The sample included 58% women, 18% African-American, 8% other races, and 12% Latinx participants. The 22,611 included participants provided 50,786 personality assessments between 2006 and 2020.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive statistics for the total sample and by cognitive impairment status during the study.

| Unimpaired | Impaired | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 17104 (75.6%) | 5507 (24.4%) | 22611 (100%) |

| N assessments | 39430 (77.6%) | 11356 (22.4%) | 50786 (100%) |

| Sex (Women) | 10043 (58.7%) | 3159 (57.4%) | 13202 (58.4%) |

| Black | 2527 (14.8%) | 1489 (27.0%) | 4016 (17.8%) |

| White | 13289 (77.7%) | 3528 (64.1%) | 16817 (74.4%) |

| Other race | 1288 (7.5%) | 490 (8.9%) | 1778 (7.9%) |

| Latinx | 1856 (10.9%) | 878 (15.9%) | 2734 (12.1%) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age, yr. | 63.00 (9.52) | 70.32 (11.07) | 64.79 (10.40) |

| Time, yr. | 5.45 (4.63) | 4.52 (4.34) | 5.23 (4.58) |

| Assessments | 2.31 (1.13) | 2.06 (1.04) | 2.25 (1.11) |

| Education, yr. | 13.33 (2.76) | 11.00 (3.52) | 12.76 (3.13) |

| TICSm | 16.79 (3.27) | 10.79 (3.91) | 15.33 (4.29) |

| Neuroticism | 2.04 (0.62) | 2.11 (0.65) | 2.06 (0.63) |

| Extraversion | 3.21 (0.55) | 3.16 (0.58) | 3.19 (0.56) |

| Openness | 3.00 (0.54) | 2.81 (0.60) | 2.95 (0.56) |

| Agreeableness | 3.54 (0.47) | 3.46 (0.54) | 3.52 (0.49) |

| Conscientiousness | 3.40 (0.46) | 3.23 (0.53) | 3.36 (0.48) |

Note. TICSm = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Unimpaired are participants who were not impaired at any assessment during the study. Impaired are participants who were impaired at any point during the study. 7741 participants provided 1 personality assessment; 5625 provided 2 assessments; 5192 provided 3 assessments; 4046 provided 4 assessments; and 7 provided 5 assessments.

Over the duration of the study, 5507 participants (24%) scored in the impaired range. These participants provided 11,356 personality assessments, of which 3,095 were before cognitive impairment, and 8,261 were during cognitive impairment. The unadjusted baseline means indicated that the impaired group was older, had lower education, was more likely to be Black or Latinx, had a lower TICSm score, and scored higher on neuroticism and lower on extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness compared to nonimpaired participants (Table 1).

Personality trajectories leading to and during cognitive impairment

Multilevel modeling results are in Table 2. The model accounted for normative personality changes that occur over time with aging, but this study focused on parameters that assessed change leading up to (Before-CI) and during (During-CI) cognitive impairment. We found no significant change in neuroticism leading up to impairment, but neuroticism significantly increased during cognitive impairment. Similarly, declines in openness were significant during but not before impairment. For extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, there were significant declines both before and during cognitive impairment. In terms of effect size, the personality changes in relation to dementia were small, especially leading up to cognitive impairment (Figure 2). To interpret the coefficient in Table 2, note that the personality traits were standardized, and the time variables were coded per decade. Thus, for neuroticism, the estimated change over a decade before cognitive impairment was about d=.04 and during cognitive impairment was about d=.1. Across most traits, change during impairment was roughly two to three times larger than change before cognitive impairment, with the largest acceleration in the rate of decline for agreeableness and conscientiousness (both from d=−.11 to about d=−.35).

Table 2.

Estimates from multilevel modeling of change in personality in relation to cognitive impairment.

| Neuroticism | Extraversion | Openness | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| Intercept | 0.313 | 0.036 | <.001 | −0.514 | 0.037 | <.001 | −1.042 | 0.035 | <.001 | −1.035 | 0.035 | <.001 | −0.991 | 0.036 | <.001 |

| Age | −0.148 | 0.008 | <.001 | 0.051 | 0.008 | <.001 | −0.023 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.038 | 0.008 | <.001 | −0.026 | 0.008 | 0.002 |

| Age2 | 0.023 | 0.005 | <.001 | −0.050 | 0.005 | <.001 | −0.031 | 0.005 | <.001 | −0.031 | 0.005 | <.001 | −0.027 | 0.005 | <.001 |

| Gender (Women) | 0.187 | 0.012 | <.001 | 0.162 | 0.013 | <.001 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.365 | 0.514 | 0.012 | <.001 | 0.217 | 0.012 | <.001 |

| Education | −0.037 | 0.002 | <.001 | 0.023 | 0.002 | <.001 | 0.085 | 0.002 | <.001 | 0.022 | 0.002 | <.001 | 0.054 | 0.002 | <.001 |

| Black | −0.279 | 0.016 | <.001 | 0.136 | 0.017 | <.001 | 0.106 | 0.016 | <.001 | −0.004 | 0.016 | 0.796 | −0.101 | 0.016 | <.001 |

| Other race | −0.069 | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.714 | 0.030 | 0.024 | 0.219 | −0.054 | 0.024 | 0.026 | −0.040 | 0.025 | 0.104 |

| Latinx | 0.061 | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.616 | −0.014 | 0.021 | 0.513 | −0.078 | 0.021 | <.001 | 0.040 | 0.021 | 0.064 |

| Time | −0.178 | 0.023 | <.001 | −0.144 | 0.022 | <.001 | −0.184 | 0.022 | <.001 | −0.111 | 0.023 | <.001 | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.478 |

| Time2 | 0.054 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.065 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.139 | 0.021 | <.001 | 0.048 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.281 |

| Age*Time | 0.055 | 0.013 | <.001 | −0.011 | 0.013 | 0.399 | −0.037 | 0.013 | 0.004 | −0.010 | 0.013 | 0.449 | −0.068 | 0.014 | <.001 |

| Before-CI | 0.044 | 0.024 | 0.074 | −0.098 | 0.023 | <.001 | −0.058 | 0.023 | 0.011 | −0.111 | 0.024 | <.001 | −0.118 | 0.024 | <.001 |

| During-CI | 0.101 | 0.030 | 0.001 | −0.143 | 0.029 | <.001 | −0.147 | 0.028 | <.001 | −0.353 | 0.031 | <.001 | −0.344 | 0.031 | <.001 |

Note. CI= cognitive impairment. Age and time (including before and during cognitive impairment) are in decades. Fully unconditional models, with no predictors, were used to estimate within-person variance of the traits, which ranged from 30% for extraversion to 37% for agreeableness. Follow-up analyses found that within-person variance was generally larger in the subsample cognitively impaired at any point in the study (e.g., for neuroticism: 33% for the cognitively unimpaired and 47% in those cognitively impaired; for conscientiousness: 31% for the cognitively unimpaired and 57% in those cognitively impaired). Nominal p-value reported and considered significant if p < .01. Results also hold if accounting for multiple testing using Benjamini and Hochberg’s false discovery rate method.

Figure 2.

Personality changes before and during cognitive impairment.

Note. Change metric is SD per decade. For example, Conscientiousness declined .34 SD during impairment.

In follow-up analyses, we examined whether the personality changes were larger in individuals with more severe impairment by testing the interaction between time and a dummy coded variable (CIND=0 vs. Dementia=1, based on the last cognitive assessment; n=11,356 personality assessments). The results indicated that while there were trends for larger personality changes in the dementia group, the interaction was significant only for agreeableness (b=−.22, SE=.06, p<.001), and not neuroticism (b=.05, SE=.05, p=.29), extraversion (b=−.13, SE=.05, p=.016), openness (b=−.10, SE=.05, p=.056), or conscientiousness (b=−.14, SE=.06, p=.017).

Discussion

This study found detrimental personality changes in individuals with cognitive impairment, while accounting for demographic differences and normative changes that occur with aging. Some personality changes were statistically significant before cognitive impairment, but such preclinical changes were smaller and not statistically significant for neuroticism and openness. Compared to the preclinical stage, change during cognitive impairment was two to three fold larger and significant for all five traits: neuroticism increased, and extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness declined. Compared to other traits and past research2, 4–9, the changes in neuroticism were smaller than expected, while the changes in agreeableness were larger than expected. Overall, the findings were consistent with the expected detrimental and accelerating changes in personality with the progression of cognitive impairment2, 21, 30.

Comparisons with previous studies

The current findings are consistent in direction with the results of a meta-analysis of retrospective observer rating studies, which reported increases in neuroticism and decreases for the other four traits2. It is worth noting that observer-rated changes were substantially larger for some traits, such as a d=1 for neuroticism (compared to d=.1 in the current study) and a d=−1.8 for conscientiousness (compared to d=−.35 in the current study), but similar for openness and agreeableness. Some differences could be due to the inclusion of more advanced dementia in studies of observer ratings. One study of MCI, for example, found changes similar in magnitude to those reported in this study17. It is also possible that some impaired individuals might be unable to reliably report on their personality and thus dilute the changes observed for the group. It is also possible that effect sizes from retrospective studies could be inflated by contrast effects between premorbid and current personality, potential labeling effects due to the diagnosis, or some “enhancement” bias of the recalled premorbid personality2. Despite the limitations of each assessment method and study design, the consistency in the direction of changes across self-(prospective) and observer-(retrospective) ratings is remarkable.

Given the different research designs and analytic approaches of previous prospective studies4–9, it is difficult to compare the current findings with past research. For preclinical changes before impairment, one previous study found no changes in personality9, which is consistent with our null findings for neuroticism and openness, but not for the other traits. The discrepant patterns of statistically significant results could be due to power, given that the current study had a larger sample. With respect to effect sizes, the current findings confirmed that, if any, preclinical changes in personality are small.

Most previous prospective studies of change from before to during impairment found significant changes only for neuroticism5–8 (one study also found openness to decline5 and some studies did not assess all five traits6–8). The current study, however, found changes for all five traits during cognitive impairment. Contrary to previous prospective studies, the largest changes were not found for neuroticism but for agreeableness and conscientiousness. The differences across traits are unlikely to be simply due to power. Perhaps one reason for the divergent results is the difference in the timing, assessment of personality and cognitive impairment across studies.

Implications

The findings of this study have theoretical and clinical implications. The changes in the five major personality traits are likely to parallel behavioral, emotional, and other psychological changes commonly observed in people with cognitive impairment and dementia5, 31–33. The increase in neuroticism could manifest as increased mood fluctuations, sadness, uncontrolled temper, anger, and emotional vulnerability. Social withdrawal, passivity, and decreases in talkativeness could be signs of the decline in extraversion. Loss of interest in activities and repetitive behaviors or thoughts could parallel the decline in openness. The decline in agreeableness and conscientiousness could manifest as a loss of empathy, socially unacceptable behaviors, and becoming uncooperative or aggressive. The decline in conscientiousness could also present as a loss of drive and impaired motivation. While the observed changes are generally interpreted as detrimental and seem to parallel the emergence of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, some changes could be adaptive. For example, increases in neuroticism could lead to seeking help or declines in extraversion and openness might reduce stimulation that could be overwhelming.

Another implication of the current findings is that most patients do not seem unaware (anosognosia) of initial, disease-related personality changes. Indeed, the change in self-ratings provides evidence that many patients are able to recognize changes similar to those observed by knowledgeable informants and clinicians. This suggests that most patients are aware of their personality and update their ratings to recognize the personality changes occurring during the early stages of cognitive impairment. Given that patients recognize personality changes, the findings support patients themselves as a useful source of information in clinical settings.

This study also has implications for understanding personality traits as risk factors for ADRD and other health outcomes34. Prior research indicates that a single assessment of personality (even early in life)35 has robust associations with risk of developing dementia36. However, tracking self-rated personality change to predict incident impairment could have limited benefits, given the inconsistent findings and modest change in the preclinical phase. Still, individual differences in the rate of personality change may be differentially related to the risk of specific types of dementia (e.g., frontotemporal dementia)37. Another implication of finding changes in personality before cognitive impairment is that reverse causality could partly explain the association between personality and risk of dementia. However, the preclinical changes were small and inconsistent across traits and studies, which suggests that reverse causality is unlikely to explain the association between personality and dementia risk.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies to address the critical question of personality changes in relation to cognitive impairment by modeling change in trajectories before and during cognitive impairment. Yet, limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Moderate to severe cognitive impairment is likely to increase the likelihood of dropout, which likely limited this study to the early stages of cognitive impairment. There was a trend for larger changes in people with dementia compared to CIND, but dropout and potentially less reliable data in those with dementia may underestimate such differences. Another limitation is the lack of precise information on the exact timing of dementia onset. However, those changes are typically gradual, and difficult to pinpoint, even in clinical practice. A related limitation is the four-year time gap between personality assessments. Ideally, more frequent and longer follow-ups would provide more precise estimates of personality change and would allow testing for non-linear trajectories. The study also lacked information on dementia type. Conceivably, personality changes could differ across Alzheimer, frontotemporal, vascular, and other causes of dementia37, 38. This study was further limited to a US sample and should be replicated in other cultural contexts39. Finally, brief scales measured the five major personality traits, the dominant paradigm in current personality psychology, but more could be learned from more specific personality measures (e.g., facets)40, 41 or instruments dedicated to assessing dementia-related changes42, 43.

Conclusions and Implications

The current study systematically mapped the trajectory of the five major personality dimensions before and from the point on which impairment can be detected with standard cognitive testing. We found a pattern of detrimental personality change across the preclinical and clinical stages. The effects were small and inconsistent before impairment but became more noticeable when people were cognitively impaired. This pattern suggests that changes accelerate with conversion to dementia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG068093, and R01AG053297. The HRS is supported by the National Institute on Aging grant U01AG009740 awarded to the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose

References.

- 1.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam M, Mazumder M, Schwabe-Warf D, et al. Personality Changes With Dementia From the Informant Perspective: New Data and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2019;20(2):131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrae RR, Costa PT Jr. Validation of the Five-Factor Model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of personality and social psychology 1987;52:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzma E, Sattler C, Toro P, et al. Premorbid personality traits and their course in mild cognitive impairment: results from a prospective population-based study in Germany. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders 2011;32(3):171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caselli RJ, Langlais BT, Dueck AC, et al. Personality Changes During the Transition from Cognitive Health to Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2018; 10.1111/jgs.15182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoneda T, Rush J, Berg AI, et al. Trajectories of Personality Traits Preceding Dementia Diagnosis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2016:gbw006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waggel SE, Lipnicki DM, Delbaere K, et al. Neuroticism scores increase with late-life cognitive decline. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2015;30(9):985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoneda T, Rush J, Graham EK, et al. Increases in Neuroticism May Be an Early Indicator of Dementia: A Coordinated Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2020;75:251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terracciano A, An Y, Sutin AR, et al. Personality Change in the Preclinical Phase of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA psychiatry 2017;74(12):1259–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology 2013;12(2):207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terracciano A, Bilgel M, Aschwanden D, et al. Personality associations with amyloid and tau: Results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging and meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry 2022;91(4):359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terracciano A, Walker K, An Y, et al. The association between personality and plasma biomarkers of astrogliosis and neuronal injury. Neurobiology of aging 2023; 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee A, Strauss ME, Smyth KA, et al. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of neurology 1992;49:486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegler IC, Dawson DV, Welsh KA. Caregiver Ratings of Personality-Change in Alzheimers-Disease Patients - a Replication. Psychology and aging 1994;9(3):464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson DV, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Siegler IC. Premorbid personality predicts level of rated personality change in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 2000;14(1):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pocnet C, Rossier J, Antonietti JP, et al. Personality changes in patients with beginning Alzheimer disease. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56(7):408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donati A, Studer J, Petrillo S, et al. The evolution of personality in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders 2013;36(5-6):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrente F, Pose M, Gleichgerrcht E, et al. Personality Changes in Dementia: Are They Disease Specific and Universal? Alzheimer disease and associated disorders 2014; 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Brant LJ, et al. Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and aging 2005;20:493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lachman ME, Weaver SL, Waltham MA. The Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) personality scales: Scale construction and scoring. Brandeis University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terracciano A, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, et al. Cognitive impairment, dementia, and personality stability among older adults. Assessment 2018;25(3):336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 1988;1(2):111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, et al. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2011;66 Suppl 1:i162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davydow DS, Levine DA, Zivin K, et al. The association of depression, cognitive impairment without dementia, and dementia with risk of ischemic stroke: a cohort study. Psychosomatic medicine 2015;77(2):200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saczynski JS, Rosen AB, McCammon RJ, et al. Antidepressant Use and Cognitive Decline: The Health and Retirement Study. Am J Med 2015;128(7):739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark DO, Stump TE, Tu W, et al. Hospital and nursing home use from 2002 to 2008 among U.S. older adults with cognitive impairment, not dementia in 2002. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders 2013;27(4):372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Luchetti M, et al. Feeling Older and the Development of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2016; 10.1093/geronb/gbw085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Internal Medicine 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terracciano A, Sutin A. Personality and Alzheimer’s disease: An integrative review. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 2019;10(1):4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osborne H, Simpson J, Stokes G. The relationship between pre-morbid personality and challenging behaviour in people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & mental health 2010;14(5):503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, et al. Self-reported personality traits are prospectively associated with proxy-reported behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia at the end of life. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2018;33(3):489–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouch I, Dorey JM, Padovan C, et al. Does Personality Predict Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia? Results from PACO Prospective Study. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2019;69(4):1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hajek A, König H-H. Personality and falls: findings based on the survey of health, aging, and retirement in Europe. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2021;22(12):2605–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman BP, Huang A, Peters K, et al. Association Between High School Personality Phenotype and Dementia 54 Years Later in Results From a National US Sample. JAMA psychiatry 2020;77(2):148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Luchetti M, et al. Is personality associated with dementia risk? A meta-analytic investigation. Ageing Research Reviews 2021;67:101269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sollberger M, Neuhaus J, Ketelle R, et al. Interpersonal traits change as a function of disease type and severity in degenerative brain diseases. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2011;82(7):732–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terracciano A, Aschwanden D, Passamonti L, et al. Is neuroticism differentially associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia? Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021;138:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bond MH, Lu Q, Lun VM-C, et al. The wealth and competitiveness of national economic systems moderates the importance of Big Five personality dimensions for life satisfaction of employed persons in 18 nations. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2020;51(5):267–282. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Aschwanden D, et al. Five-factor model personality domains and facets associated with markers of cognitive health. Journal of Individual Differences 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terracciano A, Piras MR, Sutin AR, et al. Facets of personality and risk of cognitive impairment: Longitudinal findings in a rural community from Sardinia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022; (Preprint):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balsis S, Carpenter BD, Storandt M. Personality change precedes clinical diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2005;60(2):P98–P101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bózzola FC, Gorelick PB, Freels S. Personality changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of neurology 1992;49(3):297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.