Abstract

TP63 (p63) is strongly expressed in lower-grade carcinomas of the head and neck, skin, breast, and urothelium to maintain a well-differentiated phenotype. TP63 has two transcription start sites at exons 1 and 3′ that produce TAp63 and ΔNp63 isoforms, respectively. The major protein, ΔNp63α, epigenetically activates genes essential for epidermal/craniofacial differentiation, including ΔNp63 itself. To examine the specific role of weakly expressed TAp63, we disrupted exon 1 using CRISPR-Cas9 homology-directed repair in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) line. Surprisingly, TAp63 knockout cells having either monoallelic GFP cassette insertion paired with a frameshift deletion allele or biallelic GFP cassette insertion exhibited ΔNp63 silencing. Loss of keratinocyte-specific gene expression, switching of intermediate filament genes from KRT(s) to VIM, and suppression of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion components indicated the core events of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Many of the positively and negatively affected genes, including ΔNp63, displayed local DNA methylation changes. Furthermore, ΔNp63 expression was partially rescued by transfection of the TAp63 knockout cells with TAp63α and application of DNA methyltransferase inhibitor zebularine. These results suggest that TAp63, a minor part of the TP63 gene, may be involved in the auto-activation mechanism of ΔNp63 by which the keratinocyte-specific epigenome is maintained in SCC.

Keywords: TP63, p63, TAp63, ΔNp63, CRISPR/Cas9, Squamous cell carcinoma, Epigenome, Keratinocyte differentiation, DNA methylation, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Introduction

TP63 (also termed p63 or p51) was originally identified as a close analog to the TP53 (p53) tumor suppressor gene [1,2]. Experiments in mouse systems showed that this gene is essential for embryonic development of the epidermis, craniofacial tissues, urothelium, and limbs [3,4]. Human germline TP63 mutations manifest as developmental defects, such as ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, and cleft lip/palate (EEC) syndrome [5], [6], [7], [8].

TP63 has two transcriptional start sites, of which exon 1 is used to synthesize the trans-activator isoform (TAp63) and exon 3′ for the N-terminally truncated isoform (ΔNp63). For each RNA type, α, β, and γ variants are produced by alternative splicing [2]. Hereafter, we use the terms “TA-p63” and “ΔN-p63” to indicate the genes (DNA), transcripts (RNA), and products (proteins) of the two different TP63 forms regardless of the spliced variants. Where important, isoform names such as TAp63α and ΔNp63α are specified.

The basal layers of stratified epithelia, particularly keratinocyte stem cells, express TP63 almost exclusively as ΔNp63α [9], [10], [11], [12], which bears the main function of TP63 [13]. Well-differentiated, lower-grade carcinomas of the epidermis, head and neck, bladder, breast, and prostate strongly express ΔNp63α before undergoing malignant progression by losing the protein [14], [15], [16], [17], [18].

Multiple TP63-binding enhancers in a wide chromosomal region flanking exon 3′ organize a self-activation loop for ΔN-p63 transcription [19]. ΔNp63α activates genes for keratinocyte differentiation by binding to the enhancers and causing histone acetylation (H3K27ac) [11,20]. More recently, ΔNp63α was found to assemble super-enhancers by interacting with SOX2 or KLF4/5 and chromatin regulatory factors to induce epidermal/craniofacial differentiation genes [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. The α domain of ΔNp63α reportedly interacts with p300 histone acetyltransferase [26]. These studies collectively indicate that ΔNp63α causes chromatin remodeling and builds super-enhancers with other epigenetic regulators to activate genes involved in epidermal/craniofacial differentiation [27].

Owing to the low-level RNA synthesis and rapid turnover of proteins, TA-p63 is not easily identified in keratinocyte precursors or carcinoma cells [9], [10], [11]. When ectopically expressed in cultured cells, the TA-p63 protein responds to DNA damage [28], [29], [30]. In mouse development, TA-p63 is constitutively expressed in oocytes during meiotic arrest to maintain genomic stability, similar to p53 in somatic cells [31]. TA-p63-null embryos accomplished normal development. However, another study detected mild skin symptoms and hair defects in germline TA-p63 knockout mice with age [32]. After examinations with various mouse models, the true physiological function of TA-p63 in epidermal tissue development remains unclear [11,33]. Importantly, a few human clinical cases with heterozygous mutations in the TA-p63-specific region also show abnormalities related to the developmental defects caused by mutations in other regions of TP63 [34,35].

Thus, to explore the biological significance of TA-p63, we disrupted exon 1 of TP63 by CRISPR-Cas9 in a pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) line. The elimination of TA-p63, despite its low expression, can considerably affect ΔN-p63 and genome-wide gene expression.

Materials and methods

Details of the reagents, primers, apparatus, manufacturers, and protocols are given in Supplementary Information: Materials and Methods.

Cell lines

FaDu nasopharyngeal SCC cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC HTB-43). Saos2 cells were obtained from RIKEN BRC Cell Bank (RCB0428). Cells obtained from cell banks were subcultured and stored at −135 °C and used before 25 passages. Cell cultures were checked for the absence of mycoplasmas using MycoStrip (Invivogen).

Genome editing

We used the p63 (TP63) Human Gene Knockout Kit (KN20803; OriGene Technologies) designed for CRISPR-Cas9 homology-directed repair (HDR). pCas-Guide CRISPR vectors (KN208013G1 and KN208013G2) had the gRNA sequences GTCAGGGCAGTACTGTAGGG (position +156 to +175) and AAACTCACCGCTGGATGTAA (+178 to +197), respectively. Nucleotide +1 corresponds to the reported 5′ end of TA-p63 mRNAs: NM_003722.5 for variant 1 (TAp63α), NM_001114978.2 for variant 2 (TAp63β), and NM_001114979.2 for variant 3 (TAp63γ). The donor plasmid KN208013-D contained left and right homologous arms (LHA and RHA, respectively), each comprising 600 bp, and a GFP-PuroR functional cassette. We also used the GFP-BsdR cassette vector KN208013-D-Bsd containing the blasticidin resistance gene from pCMV/BsdR (Thermo Scientific, Invitrogen). Cells were selected with puromycin (0.2 µg/mL) or blasticidin (2 µg/mL).

In the first round of genome editing, the gRNA vector KN208013G2 (abbreviated as G2) and donor vector KN208013-D were transfected into FaDu cells. Puromycin-resistant cell clones were screened for the presence of the GFP-PuroR cassette at the target site by end-point PCR. The primers and enzymes are listed in Supplementary Information: Materials and Methods. In the second-round experiment, KN208013G1 (G1) and KN208013-D-Bsd were introduced into TA(d2/−)104 cells.

Sequencing of non-HDR exon 1

The Q segment of the non-HDR allele was amplified from genomic DNA with a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (PrimeSTAR MAX DNA polymerase, Takara) using Fro-F2 and In1-R2 primers. The amplified segment was isolated using preparative agarose gel electrophoresis and purified with NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up (MACHEREY-NAGEL) for sequencing (Eurofins Genomics).

Gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed using PrimeScript II Reverse Transcriptase (TAKARA BIO) and random hexamers. RT products were quantified by qPCR with the 2−ΔΔCT (delta-delta Ct) method using ACTB (β-actin) as the reference gene (relative quantity = 1.0) whose expression was not altered by TP63 exon 1 genome editing. qPCR was performed using the PikoReal Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Scientific) or StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) in technical triplicates for biological triplicates obtained at different cellular passages.

Gene expression profiling with microarray

Agilent expression array analysis (SurePrint G3 Human GE v3 8 × 60 K Microarray, design ID 072363) was performed. After double-stranded DNA synthesis using the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit, One-Color, cyanin-3 (Cy3)-labeled cRNA was synthesized. Fragmented cRNA was hybridized with an Agilent Expression Array. Scanned data (SureScan Microarray data scanner G2600D) were analyzed using Feature Extraction software for digitalization. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS)

Methods for PCR-free library preparation, cluster generation, and sequencing are summarized in Supplementary Information: Materials and Methods.

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS)

Genome-wide DNA methylation was analyzed by RRBS, which covers more than 4 million CpGs at biologically relevant positions, such as promoters and CpG islands (https://www.activemotif.jp/documents/1836.pdf). Genomic DNA was digested with TaqαI (TaqI-v2, NEB R0149) at 65 °C for 2 h and then with MspI (NEB R0106) at 37 °C overnight. The DNA digest was subjected to library generation using the Ovation RRBS Methyl-Seq Kit (Tecan 0353-32). Briefly, the digested DNA was ligated with adaptors, end-repaired, and subjected to bisulfite conversion using the EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen 59824). After amplification and purification, libraries were analyzed using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation System and quantified using the KAPA Library Quant Kit ABI Prism qPCR Mix (Roche KK4835) for sequencing (NextSeq 500 system).

Results

Genome editing to disrupt exon 1 of TP63

FaDu cells have normal alleles of TP63 without amplification [36] and are suitable for genome editing with CRISPR/Cas-9. As estimated by RT-qPCR with published primers [37], TA-p63 expression was nearly 103-fold lower than ΔN-p63 expression (Fig. 1(A), (B)). The spliced isoforms, α, γ, and β, were found at a ratio of 1:10−1:10−3 (Fig. 1(B)). Consistent with the RT-qPCR results, the ΔNp63α protein was observed predominantly in FaDu cells by western blotting with anti-p63 monoclonal antibody 4A4 (Fig. 1(C), lane 1), whereas TA-p63 proteins were unidentifiable [10,38,39]. The positions of TAp63α, TAp63γ, ΔNp63α, and ΔNp63γ were confirmed by transfection of each expression vector (lanes 3–6) and empty vector (lane 2) into Saos2 cells.

Fig. 1.

Exon–intron structure of TP63 and expression of its variants in FaDu cells. (A) Top, exon-intron structure of TP63. Exons 1 to 15 (rectangles) and the TA and ΔN promoter regions (yellow and blue squares) are aligned. Size (in base pairs) is shown above each exon. Middle, six typical variants produced from TP63. The TA-p63 and ΔN-p63 transcripts undergo alternative splicing (dotted lines) to generate α, β, and γ variants. “An” indicates polyadenylation site. Positions of the start codon (AUG) are indicated for TA-p63 and ΔN-p63 RNAs. Bottom, positions of the primer pairs (arrows) for detection of the TP63 variants by RT-qPCR. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Information: Materials and Methods. We referred to the following NCBI reference sequences: NM_003722.5 for Tap63α (TP63 variant 1), NM_001114978.2 for Tap63β (variant 2), NM_001114979.2 for Tap63γ (variant 3), NM_001114980.2 for ΔNp63α (variant 4), NM_001114981.2 for ΔNp63β (variant 5), and NM_001114982.2 for ΔNp63γ (variant 6). (B) Relative quantification of total TP63 mRNA (p63-all) and each variant mRNA in FaDu cells by RT-qPCR. qPCR was performed with ACTB as the reference gene (1.0), and quantification was conducted using the ΔΔCt method. C) TP63 proteins in FaDu cells and four variants expressed in Saos2 cells. FaDu without transfection and Saos2 transfected with TP63 variants (indicated above the lanes) were analyzed by western blotting with p63-specific monoclonal antibody 4A4. “Vec” indicates empty vector. Positions of proteins are marked on the right of the image, whereas those of standards (in kilodaltons) are on the left. SUMOylated ΔNp63α (SUMO-ΔNp63α) is also indicated.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

After the first round of CRISPR-Cas9 reaction with the gRNA G2 vector (Fig. 2(A)), approximately 60 puromycin-resistant cell clones were obtained. By genomic DNA PCR analyses with e, h, and q primer pairs (Fig. 2(A)), we identified two cell lines (clones 77 and 104) having monoallelic recombination with the GFP-PuroR cassette at the target site (Fig. 2(B)). Most of the other clones (∼50) showed off-target vector integration (data not shown). Sequencing of the non-recombinant Q segment (Fig. 2(B)) of clones 77 and 104 revealed 8-base and 2-base deletions, respectively, in the TA-p63 coding sequences (Fig. 2(C)). These clones were termed TA(d8/−)77 and TA(d2/−)104 to indicate the loss of exon 1 in one allele (−) and a frameshift deletion in the other (d8, d2) (Fig. 2(D)). The biallelic recombinant clone TA(−/−)15 was obtained from TA(d2/−)104 by the second CRISPR-Cas9 attempt using a donor vector with the BlastR gene and gRNA G1 vector (Fig. 2(B), (D)).

Fig. 2.

Genome editing by CRISPR-Cas9 homology-directed repair (HDR) in exon 1 of TP63. (A) Donor vector (KN208013-D), wild-type (WT), and HDR alleles are aligned. Primers for genomic DNA PCR (e, h, q) and those for RT-PCR of exon 1-derived transcript are also aligned (c). The left and right homologous arms (LHA, RHA), GFP and PuroR, respectively, in the vector are indicated. Boundaries of the promoter region (Pro), exon 1 (Ex1) and intron 1 (In1), of TP63 are also shown. (B) PCR analyses of genomic DNA to identify the recombinant allele(s) having the GFP-PuroR cassette at the target sites. Results of amplification of the 5′ terminal region with primer pair e, 3′ terminal region with h, and core segment with q are shown for FaDu, TA(d8/−)77, TA(d2/−)104, and TA(−/−)15. (C) Sequences of the Q segments (B, right) of human reference sequences (GRCh37), FaDu, TA(d8/−)77, and TA(d2/−)104. Nucleotides from position c.-62 in exon 1 to c.62 + 11 in intron 1 (+66 to +200 when initiation site is +1) are aligned. Sequences targeted by Guide CRISPR vectors (G1 and G2) are indicated by blue lines. Results of Pro_F2-primed forward sequencing are shown, which matched the results of reverse sequencing with primer In1_R2. FaDu had one SNP in UTR (3: 189349247A > T, c.-58A > T) in exon 1. (D) Schematic of TP63 exon 1 of FaDu and the edited alleles of TA-p63 knockout cell lines.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Loss of ΔN-p63 expression by exon 1 disruption

End-point RT-PCR with primer pair c (Figs. 2(A), 3(A)) indicated that the region encompassing exon 1 to intron 1 was transcribed at a ratio of 2:1:1:0 in FaDu, TA(d8/−)77, TA(d2/−)104, and TA(−/−)15 cells. Thus, the nascent chain of TA-p63-type RNA was detectable depending on the allele structure.

Fig. 3.

ΔN-63 silencing by TP63 exon 1 genome editing. (A) Synthesis of exon-1 derived RNA in FaDu and the TA-p63 knockout cell lines. TA-p63 pre-mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (end-point) with primer pair c. Control experiments without reverse transcription (PCR w/o RT) are also shown. (B) Relative quantification of TP63 variant mRNAs. Entire TP63 mRNA (p63-all) as well as ΔN-, α-, and γ-specific sequences were analyzed by RT-qPCR with primers shown in Fig. 1A. “ND” (not determined) indicates too low to determine (≤10−5 in comparison with ACTB). (C) Western blot analysis of TP63 proteins and β-actin (control) in FaDu and the TA-p63 knockout cell lines.

Surprisingly, RT-qPCR results showed that the amount of ΔN-p63 RNA decreased ∼104-fold in the three TA-p63 knockout cell lines (Fig. 3(B)). Consequently, the total TP63 RNA (p63-all) and the α and γ RNA variants decreased by two to three orders of magnitude in the knockout cells. Meanwhile, western blotting results clearly showed the absence of ΔNp63α (Fig. 3(C)) while the constant appearance of control β-actin protein in all cell lines. Thus, the ΔN-p63 transcription starting with exon 3′ was shut down by the exon 1 genome editing.

Profound changes in global gene expression

By gene expression profiling with microarray, we detected 1169 genes showing increase or decrease of ≥5-foldchange (in log2) in TA(d2/−)104 or TA(−/−)15 cells compared with FaDu cells. GO term enrichment analysis of the DEGs indicated that “extracellular matrix (ECM) organization,” “hemidesmosome assembly,” and “cell adhesion” were the three most influenced biological processes (Supplementary Information 1). The original data were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE234980 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE234980).

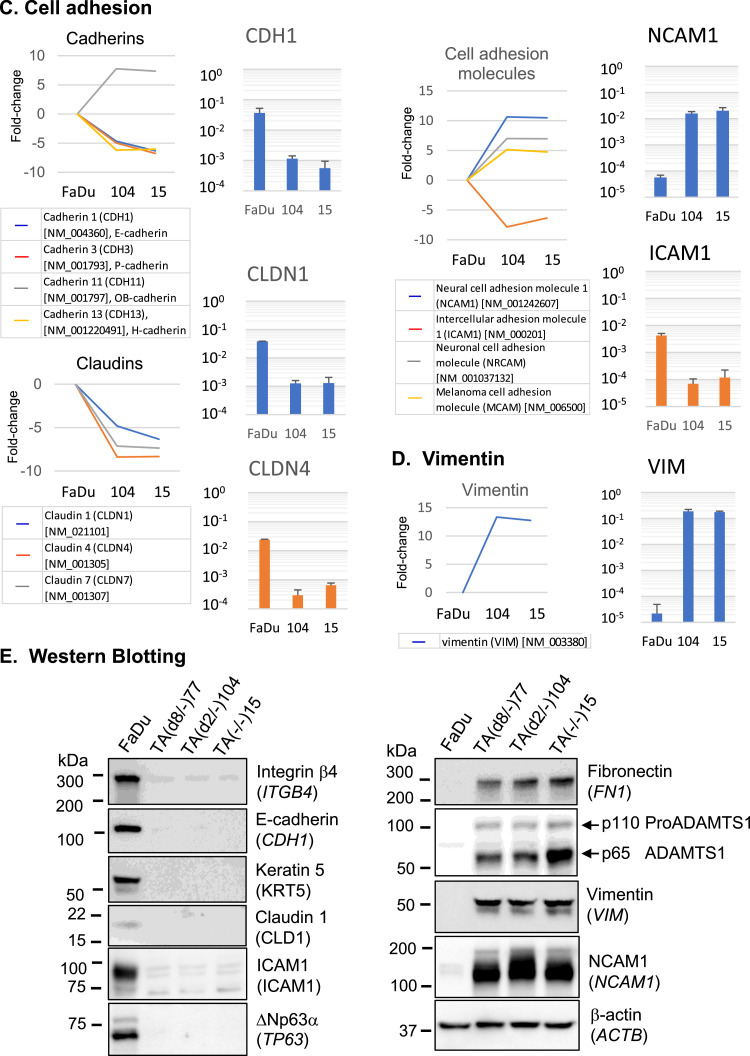

Genes showing ≥5-fold change are presented for the top three GO terms (Fig. 4(A)–(D), left, line graphs) in parallel with the results of RNA quantification by RT-qPCR (right, bar graphs). In the category of “ECM organization,” COL4A4 (coding for collagen type IV alpha 4), FN1 (fibronectin 1), and LAMA1 (laminin subunit alpha 1) were activated 10- to 100-fold as determined by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4(A)). ADAMTS1, an ADAM metallopeptidase gene involved in tumor development [40] was also upregulated nearly 1000-fold. By contrast, ITGA3 (integrin α3) and ITGB4 (integrin β4) decreased 10- to 100-fold (Fig. 4(A)). Genes involved in “hemidesmosome assembly,” including COL17A1 (collagen type IV alpha 4 domain), LAMC2 (laminin subunit gamma 2) and KRT5 (keratin 5), were suppressed 100- to 1000-fold (Fig. 4(B)). Among the “cell adhesion” genes (Fig. 4(C)), CDH1 (E-cadherin), CLDN1 (claudin 1), CLDN4 (claudin 4), and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) showed 30- to 100-fold downregulation in expression, whereas NCAM1 (neural cell adhesion molecule 1) showed a 100-fold increase in expression. In addition, VIM (vimentin) (Fig. 4(D)) appeared to replace KRT5, indicating cytoskeletal remodeling.

Fig. 4.

Prominent changes in gene expression as the result of TA-p63 genome editing.

(A–D) Based on the GO term enrichment analysis with the expression array results (Supplementary information 1), genes with GO terms of extracellular matrix organization (A), hemidesmosome assembly (B), and cell adhesion (C) were examined. Changes in VIM expression (D) were also analyzed for comparison with KRT5 in (A). Left, Results of the microarray analysis are shown in fold-change (log2). Right, Relative quantification of mRNAs by RT-qPCR using ACTB (β-actin) as the reference (=1.0). ACTB expression was not altered by TP63 exon-1 genome editing. Measurements were performed in technical triplicates with biological triplicates for FaDu, TA(d2/−)104, and TA(−/−)15. (E) Western blot analysis of FaDu and the three TAp63 knockout cell lines. Proteins synthesized from 9 genes appeared in A–D, TP63 proteins, and control β-actin were analyzed. Gene symbol is in parenthesis. Positions of protein size markers (in kilodaltons, kDa) are indicated.

Western blotting results showed a stark contrast in protein composition between FaDu and the three TA-p63 knockout cell lines (Fig. 4(E)). Integrin β4, E-cadherin, Keratin 5, Claudin 1 and ICAM1 proteins became undetectable in the TA-p63 knockout cells, as ΔNp63α did so. By contrast, Fibronectin, ADAMTS1, Vimentin and NCAM1 protein levels significantly increased.

Apart from the GO term analysis, keratinocyte-specific gene expression was also examined. In total, the expression of 56 of the proposed 76 keratinocyte-specific genes [41] was significantly downregulated in the TA-p63 knockout cells (Supplementary Information 2). These genes included non-structural protein genes (SERPINB5, TACSTD2, TRIM29, SFN, and S100A2) (Supplementary Information 3, d). Suppression of genes encoding keratins (other than KRT5), desmosome proteins, and GAP junction proteins are also shown (a–c).

Thus, TA-p63 knockout cells showed suppression of well-studied epithelial genes (KRT5, CDH1, ICAM1, CLDN1, etc.) with concomitant activation of non-epithelial genes (FN1, VIM, NCAM1, etc.). These changes represent the core events of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [42] and correspond to the backward reaction of ΔNp63α-dependent keratinocytes/craniofacial differentiation [24].

Gene expression related to DNA methylation/demethylation

We compared the DNA methylation status between FaDu and TA(d2/−)104 by RRBS, which can cover 4 million CpG sites biologically relevant for methylation (5 mC) (Fig. 5). The original data are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE234980 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE234980). As observed for ITGB4, KRT5, ICAM1, CLDN4, and CDH1 (Fig. 5(A), a–e), many genes being suppressed in TA(d2/−)104 cells displayed intense methylation in the region encompassing the first and second exons. Conversely, the genes activated in TA(d2/−)104 cells, FN1, VIM1, and NCAM1, showed profound demethylation in their corresponding regions (Fig. 5(B), a–c). These results are consistent with those of genome-wide surveys concluding that transcriptional silencing is frequently associated with DNA methylation in the first exon [43] or the first intron [44] but not in further downstream regions. Interestingly, TA(d2/−)104 cells had methylation at scattered positions immediately downstream from exon 3′ of TP63, which corresponded to the first intron of ΔN-p63 (Fig. 5(A), f), suggesting involvement of DNA methylation in ΔN-p63 silencing.

Fig. 5.

Local changes in DNA methylation.

CpG methylation in FaDu and TA(d2/−)104 cells analyzed by RRBS sequencing. CpG methylation in genes whose expression was significantly inactivated (A) or activated (B) in TA(d2/−)104 (Fig. 5). Each block is a separate analysis point, with red representing methylated cytosines and blue representing unmethylated cytosines. The right arrow indicates the transcription initiation site and its orientation for each gene. The panel format is graphically explained (bottom, right).(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Similar patterns of increased DNA methylation were observed for keratinocyte-specific genes with significantly downregulated expression in TA(d2/−)104 cells (Supplementary Information 4A). Some genes, including ITGA3 and ADAMTS1, showed only a few positional changes despite their significant transcriptional suppression (Supplementary Information 4B, top). However, the suppression of COL17A1 and CLDN1 cannot be explained by DNA methylation (bottom).

Methylation rates (0 to 1.0) in the “promoter region” and the “body of gene” of each transcript were also compared between FaDu and TA(d2/−)104 (Supplementary Information 5). Most of the genes suppressed in TA(d2/−)104 cells showed an enhanced methylation rate, and vice versa, in either or both regions.

Reactivation of ΔN-p63 by TAp63α transfection and DNA demethylation

To gain insights into the mechanisms underlying ΔN-p63 silencing by TA-p63 knockout, we performed three courses of experiments with TA(d2/−)104 cells: (a) transfection (TFN) of TAp63α and TAp63γ expression vectors; (b) incubation with zebularine (4-deoxyuridine, Active Motif, 14106), a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor [45,46]; and (c) a combination of the two (Fig. 6(A)). End-point RT-PCR results showed that ΔN-p63 mRNA became detectable only in the cells transfected with the TAp63α expression vector and incubated with 500 ng/µL (2.2 × 10−3 M) zebularine (Fig. 6(B), c). Although the level of ΔN-p63 reactivation was considerably below its steady-state level in FaDu cells (10−3 by RT-qPCR), neither the “TFN”-only (a) nor “zebularine”-only (b) experiment allowed us to detect ΔN-p63 mRNA.

Fig. 6.

Partial reactivation of ΔN-p63 in TA(d2/−)104 by transient expression of TAp63α and zebularine. (A) Experiments (a) to (c) were carried out through the time courses after cell plating on day-0. Starting cell numbers (per 6 cm dish) are indicated. (a) Transfection (TFN) of the expression vectors for the period shown by red bar. (b) Incubation with zebularine for the periods shown by blue (100 ng/mL) and green (500 ng/mL) bars. (c) TFN (three expression vectors) followed by zebularine treatment. (B) Detection of TP63-related mRNA by RT-PCR (end-point). Vector-derived α-HA and γ-HA coding sequences and the endogenous ΔN-p63-specific sequences were amplified. ACTB served as the endogenous control mRNA. Cycle numbers of PCRs are indicated in parentheses. Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Information: Materials and Methods. (C) Detection of the ΔNp63α synthesis by western blotting. After the (c) course experiment with TAp63α-3HA expression vector and the empty vector, TAp63α-3HA protein was adsorbed to magnetic beads conjugated with anti-HA IgG. The whole lysates, adsorbed protein fraction (anti-HA beads), and un-adsorbed fraction (supernatant) were analyzed by western blotting with anti-p63 and anti-HA antibodies. Chemiluminescence images of the membrane sections containing lanes 5–8 were re-captured by increasing the sensitivity 12.5-fold (lanes 5′–8′).(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We attempted to detect the newly synthesized ΔNp63α protein in TA(d2/-)104 cells by western blotting at the end of the experiment (c) (Fig. 6(C)). As TAp63α and ΔNp63α migrate to close proximity on the gel (Fig. 1(C)), small amounts of ΔNp63α were not well separated from the thick band of TAp63α. We used TAp63α tagged with 3xHA by which the molecular mass was increased by 3 kDa. After the adsorption of TAp63α-3HA in the lysate onto anti-HA IgG-conjugated magnetic beads (Fig. 6(C), lane 4, arrowhead), the supernatant still contained a small amount of TAp63α-3HA, which was reactive with both anti-p63 and anti-HA antibodies (lane 6). With increased sensitivity (12.5-fold), we detected a lower band (arrow) reactive with the anti-p63 antibody but not with the anti-HA antibody (lane 6′), which corresponded to endogenous ΔNp63α in FaDu cells (lane 8, 8′). The empty vector fails (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 5′). Thus, ΔN-p63 expression was rescued to the detectable levels in RNA and protein via the forced expression of TAp63α in combination with the DNA demethylation treatment.

Off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9

The CRISPR-Cas9 system causes off-target effects, including vector integration and short-sequence variants [47,48]. By WGS of FaDu and TA(−/−)15 cells, we examined the possibility that off-target effects cause ΔN-p63 silencing. The genome wide variant calls did not increase from FaDu to TA(−/−)15 (Supplementary Information 6A). Although TA(−/−)15 cells had 80 additional gene mutations with “high” impact prediction (Supplementary Information 6B), none of them appeared to impair the ΔNp63α-dependent super-enhancer assembly [27] or shared developmental phenotypes with TP63 mutations.

In the extended TP63 region (189,000,000–189,660,000, Chr. 3, GRCh37) that covered the ΔN-p63 super enhancer, and the body of TP63 [22], TA(−/−)15 had 90 additional sequence variants (compared with 987 variants in FaDu). However, none of these variants seemed to abolish the transcriptional activation mechanism or the ΔN-p63 protein-encoding ability. Thus, we could not identify an off-target sequence alteration that could explain ΔN-p63 silencing. WGS data are available in the Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA989409).

Discussion

Conclusions

To understand the role of TA-p63 in SCCs, we destroyed exon 1 of TP63 in FaDu nasopharyngeal SCC cells by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Surprisingly, TA-p63 knockout cells caused ΔN-p63 silencing and substantial changes in the global gene expression profile, with an obvious loss of keratinocyte/craniofacial differentiation potential and the occurrence of EMT. These changes correlated with local DNA (CpG) methylation patterns, implying that ΔNp63α-dependent differentiation involves DNA methylation control. Furthermore, we observed partial reactivation of ΔN-p63 by TAp63α transfection in combination with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor zebularine. These results indicate that TA-p63 plays an important role in maintaining ΔN-p63 expression and keratinocyte-specific epigenome in SCC.

Disruption of TP63 exon 1 by CRISPR-Cas9

In our CRISPR-Cas9 experiment, only two clones, TA(d2/−)104 and TA(d8/−)77, were identified as TA-p63 knockout cells among approximately 60 puromycin-resistant clones obtained in the first round of transfection. Generally, genome editing is performed more efficiently on open chromatin than on closed chromatin, although the outcome is not affected by the chromatin status [49]. TP63 exon 1 is poorly transcribed and may be a difficult target for CRISPR-Cas9.

Although high-level off-target mutations were observed when CRISPR-Cas9 was applied to transformed human cell lines [47,48], an advanced, well-controlled experiment with human hematopoietic stem and progenitor clones concluded that the collective mutational burden in Cas9-RNP-edited cells is indistinguishable from the naturally occurring somatic background heterogeneity [50]. FaDu showed a huge number of sequence variant calls in WGS, which did not increase in TA(−/−)15 cells. Although we could not distinguish CRISR-Cas9-caused sequence variants from those due to genome instability of carcinoma cells, at least the 80 high-impact mutations newly gained by TA(−/−)15 were unrelated to the reported ΔN-p63 transcription mechanism, including the super-enhancer assembly. Furthermore, none of the ∼50 cell clones with off-target vector integration exhibited ΔN-p63 silencing or KRT5 suppression (data not shown). Thus, we consider the overall results of our genome editing experiment appropriate, although we cannot rule out the possibility that some lower-impact mutations collectively influenced ΔN-p63.

Activation/maintenance of ΔN-p63 expression by TAp63α

TA(d2/−)104 cells were indistinguishable from TA(−/−)15 cells in the genome-wide gene expression profile. Reduced haplotype expression of ΔN-p63 was not observed in TA(d2/−)104 or TA(d8/−)77 cells. In addition, the exon 1 sequences were not found in the chromatin contacts of ΔN-p63 super-enhancer [22]. Therefore, TA-p63 protein appeared to contribute to ΔN-p63 expression in SCC.

In fact, ΔN-p63 was reactivated by transfecting the cells with the TAp63α expression vector and incubating them with zebularine. A previous study showed that TAp63γ activates luciferase gene expression under the control of enhancer sequences of ΔN-p63 (C40) [19]. In this study, TAp63α but not TAp63γ activated endogenous ΔN-p63 transcription in TA(d2/−)104 cells. Thus, the α domain containing SAM and TID regions may be important for this function [33].

Intriguingly, tumor suppressor p53 inhibits the reprogramming of somatic cells and differentiation of the reprogrammed cells, leading to the redefinition of p53 as “the guardian of the epigenome” [51,52]. Similarly, TAp63α could also stabilize the epigenome governed by ΔNp63α. TAp63α (680 amino acids) has 572 sequences in common with ΔNp63α (586) and could play an epigenetic regulatory role related to ΔNp63α. Furthermore, an interaction between TA-p63 and ΔN-p63 proteins with the common oligomerization domain has been speculated [2,53], although the initial explanation for ΔN-p63 as the dominant-negative suppressor of TA-p63 is not convincing in the context of keratinocyte differentiation.

Influence of TA-p63 on tissue development in humans and mice

In a clinical study, an isolated patient with a heterozygous TP63 mutation corresponding to the amino acid substitution R97C in the TA domain displayed hand malformation and sculp skin defect [35]. Another study identified a germline mutation in the canonical translation start codon of TA-p63 (c.3G > T; p.Met1?) in patients with mild symptoms, including cleft tongue and foot deformity [34]. These naturally occurring mutations in TA-p63 could also influence ΔN-p63 expression and its function in tissue development, as we observed in SCC by genome editing.

However, ΔN-p63-silencing has never been detected in TA-p63 knockout mouse models [33]. In one study, TA-p63-null mouse oocytes escaped cell death in response to ionizing irradiation, suggesting a tumor suppressor p53-like function of TA-p63 in oocytes [31]. In another study, germline TA-p63 knockout mice but not conditional knockout mice displayed skin and hair defects with age [32]. The apparent inconsistency between TA-p63 knockout mice and our results may reflect the differences in cell growth and differentiation control between keratinocyte stem cells and SCC cells. In contrast to immortal SCC with differentiation potential, epidermal stem cells undergo only a limited number of cell cycles before committing to differentiation [54].

EMT caused by ΔN-p63 silencing

TA-p63 knockout cells showed the following profiles characteristic to the core events of EMT [42]: the replacement of keratin 5 with vimentin, explaining “cytoskeleton remodeling”; the loss of E-cadherin, claudins, etc., indicating “cell–cell adhesion weakening"; and the loss of hemidesmosome components, which is relevant to “cell–matrix adhesion remodeling". Forced expression of ΔNp63α with KLF4 causes the conversion of fibroblasts to keratinocyte-like cells [24], indicating that the direct cause of EMT is most likely ΔN-p63 silencing but not TA-p63 knockout.

ΔN-p63 and its target gene suppression by DNA methylation

In mammalian genome-wide tissue-specific gene expression studies, CpG methylation in the first exon [43] and intron [44] is closely related to transcriptional silencing. The first intron of ΔN-p63 (immediately downstream of exon 3′) showed increased CpG methylation in TA(d2/−)104 cells, indicating that ΔN-p63 silencing was at least partly caused by DNA methylation. Indeed, reactivation of ΔN-p63 by TAp63α was facilitated by DNA demethylation with zebularine. ΔNp63α increases chromatin accessibility, as detected by ATAC sequencing [21,22,24]. Furthermore, DNA methyltransferase 3a physically and functionally interacts with p63 protein at enhancers in primary human keratinocytes [55]. When SCC cells lose ΔNp63α expression during the malignant progression, general DNA methylation mechanisms would take over epigenetic control to silence the keratinocyte/craniofacial differentiation genes.

Statement

The authors did not use AI or AI-assisted technologies during the writing of this manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Iyoko Katoh: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Keiichi Tsukinoki: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ryu-Ichiro Hata: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Shun-ichi Kurata: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant numbers 19K10080, 20K09927, and 22K09934).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2023.100938.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Osada M., Ohba M., Kawahara C., Ishioka C., Kanamaru R., Katoh I., Ikawa Y., Nimura Y., Nakagawara A., Obinata M., et al. Cloning and functional analysis of human p51, which structurally and functionally resembles p53. Nat. Med. 1998;4:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang A., Kaghad M., Wang Y., Gillett E., Fleming M.D., Dotsch V., Andrews N.C., Caput D., McKeon F. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:305–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills A.A., Zheng B., Wang X.J., Vogel H., Roop D.R., Bradley A. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang A., Schweitzer R., Sun D., Kaghad M., Walker N., Bronson R.T., Tabin C., Sharpe A., Caput D., Crum C., et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celli J., Duijf P., Hamel B.C., Bamshad M., Kramer B., Smits A.P., Newbury-Ecob R., Hennekam R.C., Van Buggenhout G., van Haeringen A., et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in the p53 homolog p63 are the cause of EEC syndrome. Cell. 1999;99:143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Bokhoven H., Hamel B.C., Bamshad M., Sangiorgi E., Gurrieri F., Duijf P.H., Vanmolkot K.R., van Beusekom E., van Beersum S.E., Celli J., et al. p63 Gene mutations in EEC syndrome, limb-mammary syndrome, and isolated split hand-split foot malformation suggest a genotype-phenotype correlation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:481–492. doi: 10.1086/323123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterburg C., Osterburg S., Zhou H., Missero C., Dotsch V. Isoform-specific roles of mutant p63 in human diseases. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:536. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunner H.G., Hamel B.C., Van Bokhoven H. The p63 gene in EEC and other syndromes. J. Med. Genet. 2002;39:377–381. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzo J.M., Romano R.A., Bard J., Sinha S. RNA-seq studies reveal new insights into p63 and the transcriptomic landscape of the mouse skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015;135:629–632. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellegrini G., Dellambra E., Golisano O., Martinelli E., Fantozzi I., Bondanza S., Ponzin D., McKeon F., De Luca M. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061032098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouwenhoven E.N., van Bokhoven H., Zhou H. Gene regulatory mechanisms orchestrated by p63 in epithelial development and related disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1849:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurata S., Okuyama T., Osada M., Watanabe T., Tomimori Y., Sato S., Iwai A., Tsuji T., Ikawa Y., Katoh I. p51/p63 controls subunit alpha3 of the major epidermis integrin anchoring the stem cells to the niche. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50069–50077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koster M.I., Marinari B., Payne A.S., Kantaputra P.N., Costanzo A., Roop D.R. DeltaNp63 knockdown mice: a mouse model for AEC syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2009;149A:1942–1947. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higashikawa K., Yoneda S., Tobiume K., Taki M., Shigeishi H., Kamata N. Snail-induced down-regulation of {delta}Np63{alpha} acquires invasive phenotype of human squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9207–9213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urist M.J., Di Como C.J., Lu M.L., Charytonowicz E., Verbel D., Crum C.P., Ince T.A., McKeon F.D., Cordon-Cardo C. Loss of p63 expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukushima H., Koga F., Kawakami S., Fujii Y., Yoshida S., Ratovitski E., Trink B., Kihara K. Loss of DeltaNp63alpha promotes invasion of urothelial carcinomas via N-cadherin/Src homology and collagen/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9263–9270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X., Mori I., Tang W., Nakamura M., Nakamura Y., Sato M., Sakurai T., Kakudo K. p63 expression in normal, hyperplastic and malignant breast tissues. Breast Cancer. 2002;9:216–219. doi: 10.1007/BF02967592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucci P., Agostini M., Grespi F., Markert E.K., Terrinoni A., Vousden K.H., Muller P.A., Dotsch V., Kehrloesser S., Sayan B.S., et al. Loss of p63 and its microRNA-205 target results in enhanced cell migration and metastasis in prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15312–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110977109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonini D., Rossi B., Han R., Minichiello A., Di Palma T., Corrado M., Banfi S., Zannini M., Brissette J.L., Missero C. An autoregulatory loop directs the tissue-specific expression of p63 through a long-range evolutionarily conserved enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:3308–3318. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3308-3318.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kouwenhoven E.N., Oti M., Niehues H., van Heeringen S.J., Schalkwijk J., Stunnenberg H.G., van Bokhoven H., Zhou H. Transcription factor p63 bookmarks and regulates dynamic enhancers during epidermal differentiation. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:863–878. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai J., Chen S., Yi M., Tan Y., Peng Q., Ban Y., Yang J., Li X., Zeng Z., Xiong W., et al. DeltaNp63alpha is a super enhancer-enriched master factor controlling the basal-to-luminal differentiation transcriptional program and gene regulatory networks in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1282–1293. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y.Y., Jiang Y., Li C.Q., Zhang Y., Dakle P., Kaur H., Deng J.W., Lin R.Y., Han L., Xie J.J., et al. TP63, SOX2, and KLF5 establish a core regulatory circuitry that controls epigenetic and transcription patterns in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1311–1327. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.050. e1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y., Jiang Y.Y., Xie J.J., Mayakonda A., Hazawa M., Chen L., Xiao J.F., Li C.Q., Huang M.L., Ding L.W., et al. Co-activation of super-enhancer-driven CCAT1 by TP63 and SOX2 promotes squamous cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3619. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin-Shiao E., Lan Y., Welzenbach J., Alexander K.A., Zhang Z., Knapp M., Mangold E., Sammons M., Ludwig K.U., Berger S.L. p63 establishes epithelial enhancers at critical craniofacial development genes. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw0946. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw0946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T., Yoo S., Kong R., Sinha A., Chandramani-Shivalingappa P., Patel A., Fridrikh M., Nagano O., Masuko T., Beasley M.B., et al. Epigenomic profiling discovers trans-lineage SOX2 partnerships driving tumor heterogeneity in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:6084–6100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katoh I., Maehata Y., Moriishi K., Hata R.I., Kurata S.I. C-terminal alpha domain of p63 Binds to p300 to coactivate beta-catenin. Neoplasia. 2019;21:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi M., Tan Y., Wang L., Cai J., Li X., Zeng Z., Xiong W., Li G., Li X., Tan P., et al. TP63 links chromatin remodeling and enhancer reprogramming to epidermal differentiation and squamous cell carcinoma development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020;77:4325–4346. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katoh I., Aisaki K.I., Kurata S.I., Ikawa S., Ikawa Y. p51A (TAp63gamma), a p53 homolog, accumulates in response to DNA damage for cell regulation. Oncogene. 2000;19:3126–3130. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada Y., Osada M., Kurata S., Sato S., Aisaki K., Kageyama Y., Kihara K., Ikawa Y., Katoh I. p53 gene family p51(p63)-encoded, secondary transactivator p51B(TAp63alpha) occurs without forming an immunoprecipitable complex with MDM2, but responds to genotoxic stress by accumulation. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;276:194–200. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petitjean A., Ruptier C., Tribollet V., Hautefeuille A., Chardon F., Cavard C., Puisieux A., Hainaut P., Caron de Fromentel C. Properties of the six isoforms of p63: p53-like regulation in response to genotoxic stress and cross talk with DeltaNp73. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:273–281. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suh E.K., Yang A., Kettenbach A., Bamberger C., Michaelis A.H., Zhu Z., Elvin J.A., Bronson R.T., Crum C.P., McKeon F. p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature. 2006;444:624–628. doi: 10.1038/nature05337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su X., Paris M., Gi Y.J., Tsai K.Y., Cho M.S., Lin Y.L., Biernaskie J.A., Sinha S., Prives C., Pevny L.H., et al. TAp63 prevents premature aging by promoting adult stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanbokhoven H., Melino G., Candi E., Declercq W. p63, a story of mice and men. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011;131:1196–1207. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt J., Schreiber G., Altmüller J., Thiele H., Nürnberg P., Li Y., Kaulfuß S., Funke R., Wilken B., Yigit G., et al. Familial cleft tongue caused by a unique translation initiation codon variant in TP63. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;30:211–218. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00967-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zenteno J.C., Berdon-Zapata V., Kofman-Alfaro S., Mutchinick O.M. Isolated ectrodactyly caused by a heterozygous missense mutation in the transactivation domain of TP63. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;134A:74–76. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redon R., Muller D., Caulee K., Wanherdrick K., Abecassis J., du Manoir S. A simple specific pattern of chromosomal aberrations at early stages of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: PIK3CA but not p63 gene as a likely target of 3q26-qter gains. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4122–4129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petitjean A., Cavard C., Shi H., Tribollet V., Hainaut P., Caron de Fromentel C. The expression of TA and DeltaNp63 are regulated by different mechanisms in liver cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:512–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osada M., Inaba R., Shinohara H., Hagiwara M., Nakamura M., Ikawa Y. Regulatory domain of protein stability of human P51/TAP63, a P53 homologue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;283:1135–1141. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghioni P., D'Alessandra Y., Mansueto G., Jaffray E., Hay R.T., La Mantia G., Guerrini L. The protein stability and transcriptional activity of p63alpha are regulated by SUMO-1 conjugation. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:183–190. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.1.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehembre F., Yilmaz M., Wicki A., Schomber T., Strittmatter K., Ziegler D., Kren A., Went P., Derksen P.W., Berns A., et al. NCAM-induced focal adhesion assembly: a functional switch upon loss of E-cadherin. EMBO J. 2008;27:2603–2615. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gazel A., Ramphal P., Rosdy M., De Wever B., Tornier C., Hosein N., Lee B., Tomic-Canic M., Blumenberg M. Transcriptional profiling of epidermal keratinocytes: comparison of genes expressed in skin, cultured keratinocytes, and reconstituted epidermis, using large DNA microarrays. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003;121:1459–1468. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J., Antin P., Berx G., Blanpain C., Brabletz T., Bronner M., Campbell K., Cano A., Casanova J., Christofori G., et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:341–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenet F., Moh M., Funk P., Feierstein E., Viale A.J., Socci N.D., Scandura J.M. DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anastasiadi D., Esteve-Codina A., Piferrer F. Consistent inverse correlation between DNA methylation of the first intron and gene expression across tissues and species. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2018;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s13072-018-0205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng J.C., Weisenberger D.J., Gonzales F.A., Liang G., Xu G.L., Hu Y.G., Marquez V.E., Jones P.A. Continuous zebularine treatment effectively sustains demethylation in human bladder cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1270–1278. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1270-1278.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng J.C., Yoo C.B., Weisenberger D.J., Chuang J., Wozniak C., Liang G., Marquez V.E., Greer S., Orntoft T.F., Thykjaer T., et al. Preferential response of cancer cells to zebularine. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Y., Foden J.A., Khayter C., Maeder M.L., Reyon D., Joung J.K., Sander J.D. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu M., Zhang W., Xin C., Yin J., Shang Y., Ai C., Li J., Meng F.L., Hu J. Global detection of DNA repair outcomes induced by CRISPR-Cas9. Nucl. Acids Res. 2021;49:8732–8742. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kallimasioti-Pazi E.M., Thelakkad Chathoth K., Taylor G.C., Meynert A., Ballinger T., Kelder M.J.E., Lalevee S., Sanli I., Feil R., Wood A.J. Heterochromatin delays CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis but does not influence the outcome of mutagenic DNA repair. PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith R.H., Chen Y.C., Seifuddin F., Hupalo D., Alba C., Reger R., Tian X., Araki D., Dalgard C.L., Childs R.W., et al. Genome-wide analysis of off-target CRISPR/Cas9 activity in single-cell-derived human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell clones. Genes (Basel) 2020;11 doi: 10.3390/genes11121501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yi L., Lu C., Hu W., Sun Y., Levine A.J. Multiple roles of p53-related pathways in somatic cell reprogramming and stem cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5635–5645. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levine A.J., Greenbaum B. The maintenance of epigenetic states by p53: the guardian of the epigenome. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1503–1504. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kojima T., Ikawa Y., Katoh I. Analysis of molecular interactions of the p53-family p51(p63) gene products in a yeast two-hybrid system: homotypic and heterotypic interactions and association with p53-regulatory factors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;281:1170–1175. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watt F.M. Epidermal stem cells: markers, patterning and the control of stem cell fate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B, Biol. Sci. 1998;353:831–837. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rinaldi L., Datta D., Serrat J., Morey L., Solanas G., Avgustinova A., Blanco E., Pons J.I., Matallanas D., Von Kriegsheim A., et al. Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b associate with enhancers to regulate human epidermal stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.