Abstract

Benign lymphangioendothelioma (BL) is a rare, poorly identified, slow-growing benign vascular lesion characterized by asymptomatic, solitary, well-demarcated macules, or by mildly infiltrated plaque. We report a case of an atypical BL that arose as a tender, protuberant, flesh-colored mass with cyanotic vesicles, and then progressed to a persistent exudative wound after two incomplete excisions. The patient was also diagnosed with thoracic duct narrowing. Although the stenosis was removed by surgery, the right lower extremity ulceration and exudation did not improve. Thus, we performed a thorough excision and split-thickness skin graft transplant following vacuum sealing drainage, and eventually the patient had a favorable functional and cosmetic outcome. A biopsy revealed irregular, dilated vascular spaces lined with a single layer of flat endothelial cells extending from the superficial dermis to the subcutis that did not reach the striated muscles. Additionally, by reviewing the literature on BL, in this paper we summarize the diverse pathogenic, morphological, and immunohistochemical presentations for this rare disease, as well as the histopathological differential diagnosis of lymphangiomatosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and angiosarcoma.

Keywords: acquired progressive lymphangioma, angiosarcoma, benign lymphangioendothelioma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphangioma, lymphangiomatosis

Introduction

Benign lymphangioendothelioma (BL) is a rare, slow-growing vascular lesion that is poorly understood. It was first reported by Wilson Jones1 as malignant angioendothelioma in a 10-year-old girl and was later recognized as a benign condition and formally named “acquired progressive lymphangioma” (APL) in 1976.2 BL is characterized histologically as an uncommon lymphatic vascular proliferation with infiltrating lymphatic channels dissecting collagen.3,4 Clinically, BL lesions typically present as asymptomatic, solitary, well-demarcated macules or mildly infiltrated plaques that are pink to red-brown in color.5 According to the PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases, only 83 cases of BL (in 40 reports) have been described in English from 1963 to the present, with only a minority of cases experiencing relapse.6–8 Although BL is considered a rare presentation of lymphatic malformation rather than a true neoplasm, complete excision is necessary due to the infiltrating character of the entity.9

In this report, we describe a patient with BL on the lower leg who presented with multiple ulcers and exudation, and was successfully treated with a skin graft following debridement and vacuum sealing drainage. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria.10 The patient provided consent for the publication of case details and images. Furthermore, we conducted a review of the literature to discuss the pathogenesis, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment options for BL.

Case Report

Patient Information

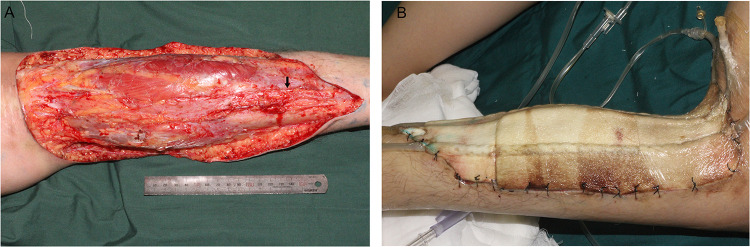

A 25-year-old female with no history of radiation exposure presented with persistent ulceration and exudation on her right lower extremity. The condition had developed three years prior following a cutaneous lesion that had been gradually growing for seven years. At age 16, the patient sustained an injury to her right calf in a bicycle accident, resulting in the development of a 3 cm x 3 cm bruise. Over time, the bruise grew into a flesh-colored, slightly tender, protuberant mass measuring 20 cm x 35 cm with cyanotic vesicles (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging showed increased signal density corresponding to the vascular lesion, extending to the superficial layer of the deep fascia. In 2018, the lesion was excised and histopathological examination revealed the presence of many irregularly shaped and anastomosing channels lined by flattened endothelial cells that had infiltrated between collagen bundles through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Atypical endothelial cells were absent. The endothelial cells expressed podoplanin (D2-40), CD31, and CD34, indicating the lymphatic nature of the lesion. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of BL or lymphangiomatosis was considered. In 2019, the patient’s wound was seeping and steadily worsening. An ultrasound revealed that the posterior lateral region of the left cervicothoracic duct was restricted. Lymphoscintigraphy showed activity in the left jugular venous angle and increased radiopharmaceutical kinetics in the right lower limb, suggesting thoracic duct outlet obstruction and lower limb lymphangioma. In May 2021, the patient underwent debridement of the lower leg, as well as recanalization and anastomosis of the chest catheter. Pathological examination suggested the possibility of hemangioendothelioma or a generalized lymphangioma. Despite the treatment, the wound on the right calf did not heal, and the patient visited our clinic for further treatment. She had been unable to walk for a year due to severe pain. The timeline of the reported incident is depicted in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The condition of the patient’s lower limb before the first debridement.

Table 1.

Timeline of Events

| Date | Information |

|---|---|

| 2014 | Patient sustained an injury to the right calf in a bicycle accident, leading to the formation of a bruise. |

| 2018 | The initial bruise evolved into a 20 cm x 35 cm mass with cyanotic vesicles. |

| 2018.9 | First excision surgery was performed on the protuberant mass. |

| 2019 | Persistent ulceration and exudation were observed in the bruised area. There was a restriction in the posterior lateral region of the left cervicothoracic duct. |

| 2021.5 | Second excision surgery was performed, along with recanalization and anastomosis of the chest catheter. |

| 2021.6 | The surgical wound on the right calf remained unhealed. The patient was unable to walk for a year due to severe pain. |

Clinical Findings

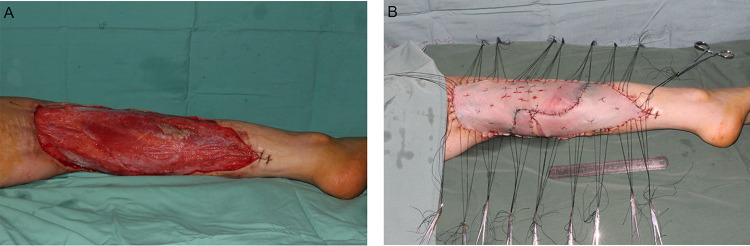

On physical examination, a hyperpigmented, slightly indurated, 14 cm × 21 cm mass with a strong odor was observed. There were also blisters, ulcerations, continuous seeping of lymph-like clear liquid, and some bleeding (Figure 2). The ulcerations were 3 cm × 4 cm and 3 cm × 5 cm.

Figure 2.

The lesion of the right lower leg after two debridements at admission. Multiple ulcers and a superficial scar were visible on the dorsal area of the right calf.

Diagnostic Approach

A wound secretion and drug sensitivity test revealed an Enterobacter cloacae infection, which was found to be sensitive to gentamicin. No abnormalities were observed upon general examination. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed scattered lesions with increased signal density.

Therapeutic Intervention

After two weeks of dressing changes for preoperative preparation, the patient was admitted to the hospital. On the first day of hospitalization, the patient underwent debridement of the right lower leg under general anesthesia to remove the lesion by excising the skin and subcutaneous tissue. During the operation, lymph-like fluid was observed oozing from the unhealthy subcutaneous adipose tissue surrounding the wound. Therefore, the excision of unhealthy adipose tissue was extended to 2 cm around the lesion until healthy fat was exposed. The 18 cm × 28 cm incision was then cleaned (Figure 3A), two vacuum sealing drainage (VSD) sponges were placed on the wound, and two semipermeable membranes were used to seal the wound before applying negative pressure (Figure 3B). Continuous negative pressure of approximately 20 kPa was applied to the wound on the right lower limb after the first debridement. Closed irrigation with sterile normal saline was then performed, and the amounts of irrigation and extraction were carefully recorded (Table 2). One week after admission, the patient underwent a second procedure in which the VSD sponges were replaced under intravenous anesthesia. During this procedure, any unhealthy subcutaneous adipose tissue and exudation surrounding the wound were also removed. The VSD was left in place for an additional week. Initially, the extraction volume was greater than the rinsing volume, exceeding it by approximately 15% (104 mL) during the first ten days after the second procedure. Over time, however, the excess volume decreased to about 5% (36 mL), and the appearance of the extracted fluid gradually changed from cloudy to transparent. Two weeks after admission, the patient received an 18 cm × 28 cm split-thickness skin graft (STSG), harvested from the right thigh, to cover the wound on the right calf (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Surgery on the first day after admission. (A) The clearly necrotic tissue was entirely removed. Arrows indicate the sural nerve. (B) Two vacuum sealing drainage devices were installed after the debridement.

Table 2.

The Intake and Output Volume of Closed Irrigation During Two VSD Treatment

| Day | Intake Volume (mL) | Output Volume (mL) | Δ Value (mL)a | Δ/Intake Ratiob |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 580 | 720 | 140 | 0.24 |

| 3 | 800 | 950 | 150 | 0.19 |

| 4 | 700 | 840 | 140 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 530 | 550 | 20 | 0.04 |

| 6 | 1300 | 1400 | 100 | 0.08 |

| 7 | 900 | 980 | 80 | 0.09 |

| 8 | 400 | 500 | 100 | 0.25 |

| Average1c | 104 | 0.16 | ||

| 11 | 1000 | 1050 | 50 | 0.05 |

| 13 | 925 | 950 | 25 | 0.03 |

| 14 | 850 | 870 | 20 | 0.02 |

| 15 | 600 | 650 | 50 | 0.08 |

| Average2d | 36 | 0.05 |

Notes: aΔDifference volume (mL) = output volume- input volume; bΔ/intake ratio = (output volume - input volume)/input volume×100%; cAverage 1, average volume after the first debridement; dAverage 2, average volume after the second debridement.

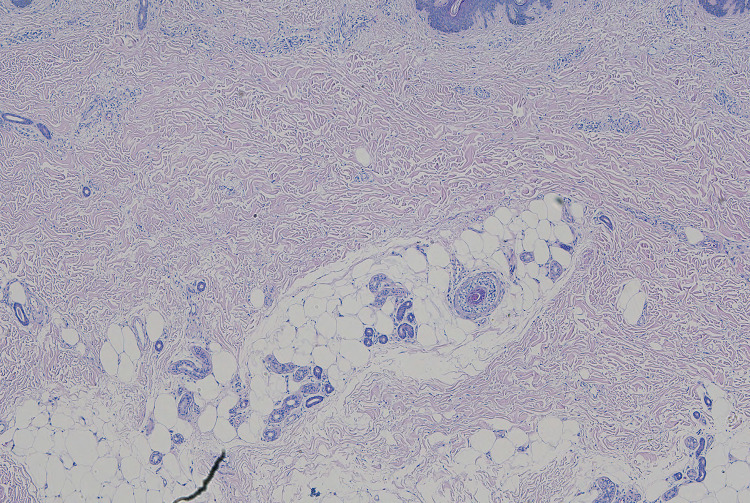

Figure 4.

Skin grafting two weeks after debridement. (A) The necrotic tissue was completely removed, with a promising amount of fresh granulation tissue covering the wound before the skin graft operation. (B) The split-thickness skin graft was sutured to the wound.

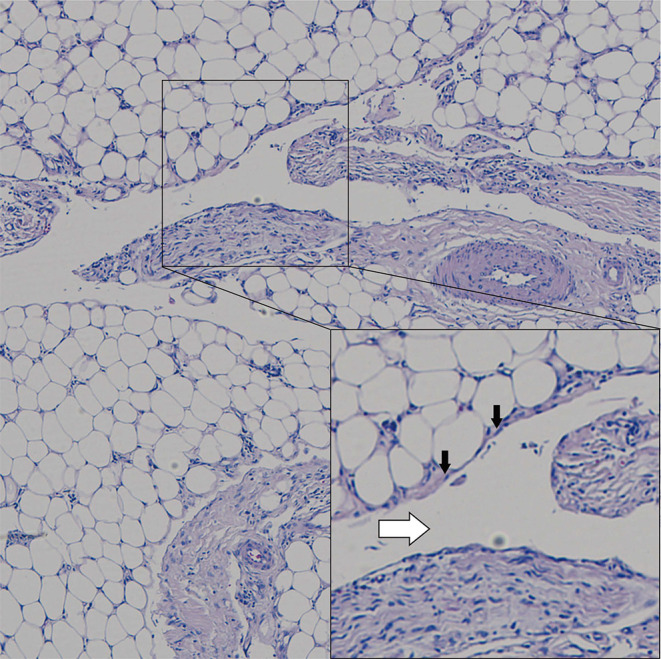

The histopathological examination of the lesions, in conjunction with the patient’s medical history, confirmed the diagnosis of BL. Microscopic analysis revealed irregular, dilated vascular spaces lined with a single layer of flat endothelial cells, which showed no signs of nuclear atypia or mitotic activity (Figure 5). The narrow vascular spaces within the dermis were separated by reticular dermal collagen bundles (Figure 6). The lesions extended from the superficial dermis to the subcutis but did not involve the striated muscles. There were no signs of extravasated red cells, hemosiderin, or inflammatory infiltrate.

Figure 5.

Pathological examination showing ectatic vascular spaces (white arrow) lined by flattened, cytologically bland endothelial cells (black arrow) dissecting through subcutaneous fat (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: B, × 4).

Figure 6.

The narrow vascular spaces separated by reticular dermal collagen bundles in the dermis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: B, × 4).

Follow-Up and Outcome

The patient showed excellent postoperative recovery, and during the 1-year follow-up conducted remotely via video, complete wound healing was observed with no associated complications or recurrence. The patient expressed satisfaction with the functional and cosmetic outcome.

Discussion

The authors conducted a comprehensive search of the published literature in three databases, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, using restricted language to English and a specific time period up to October 1, 2022. We used appropriate search keys to identify papers related to the subject of “acquired progressive lymphangioma” and “lymphangioendothelioma”. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of 86 relevant papers, the authors found 37 articles reporting 80 cases. We also searched cited cases prior to the official recognition of the terms “APL” and “BL” and identified a total of 83 patients in 40 reports (Table 3), including 27 cases diagnosed with BL after radiotherapy for breast carcinoma.6,7,11,12 Recurrences were observed only in cases with incomplete excision,6,8,12 with only one lesion progressing to an angiosarcoma eight years later.12

Table 3.

Characteristics and Treatments of Patients with Lymphangioendothelioma Reported from 1963 to 2022

| Case | Age (yr) | Duration (yr) | Sex | Location | Clinical Symptom | Physical Examination | Size | Pathological Findings | Nuclear Atypia or Mitotic Figures | Immunohistochemical Results | Follow-Up | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones 19631 | 15 | 5 | F | Right wrist | Asymptomatic | A round, flat, erythematous plaque | 2cm | Multiple, slitlike, bloodless channels throughout the dermis with a dissection-of-collagen appearance | Little or no cellular atypia or nuclear hyperchromatism | NA | Without recurrence at 3 years | Wide excision |

| Gold 19704 | 23 | 10 | M | Right thigh | Tenderness | A discolored patch | >30cm | Abnormal, narrow, endothelium-lined vessels involving dermis and subcutaneous tissue | No significant cellular atypia | NA | Without recurrence at 13 years | Wide excision |

| Watanabe 19839 | 5 | 1 | M | Left temporal, retroauricular areas, forehead, neck, shoulder; left arm | Tenderness | Dark brown erythematous lesions with slight atrophy | 3.5 x 6.5 cm | Left retroauricular area: dilated channels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells throughout the dermis and extending to the subcutaneous fat left upper arm: the appearance of “dissection of collagen” | Minimal or no cellular atypia | NA | Gradual regression | 10 mg oral prednisolone for 3 months |

| Tadaki 198837 | 8 | 4 | M | Abdominal wall | Asymptomatic | An erythematous patch | 3.7 × 7.0 cm | Tortuous vascular channels | Some cellular atypia | F-VIII-RA (-) | Without recurrence at 3 years | Excision |

| Jones 199046 | 55 | 2 | F | Forearm | NA | NA | 3 cm | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts throughout the dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | Without recurrence at 1 year | Excision |

| Jones 199046 | 28 | 1 | F | Shoulder | NA | NA | NA | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts throughout the dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Jones 199046 | 69 | 0.3 | F | Both forearms | NA | NA | >30cm | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts confined to the subpapillary region and upper dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | Died of unrelated cancers | Incisional biopsy |

| Jones 199046 | 52 | 3 | M | Left shoulder | NA | NA | NA | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts confined to the subpapillary region and upper dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | Without recurrence at 1 year | Excision |

| Jones 199046 | 68 | 0.3 | M | Forearm | NA | NA | NA | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts confined to the subpapillary region and upper dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | Without recurrence at 0.5 year, died of unrelated cancers at 1 year | Excision |

| Jones 199046 | 59 | 0.3 | M | Left side of back | NA | NA | NA | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts confined to the subpapillary region and upper dermis | None gross nuclear atypia, none multinucleate tumor cells | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | Without recurrence at 1 year | Excision |

| Zhu 199129 | 9 | 3 | M | Right calf | Swelling, warmth, itching, and pain; profuse lymphatic drainage at skin biopsy | A hyperpigmented, slightly indurated, irregular patch | 8×9 cm | Many irregularly shaped and dilated channels, lined by a single layer of endothelium within the dermis | Minimal cellular atypia, none multinucleate cells or mitotic activity | ColIV (+), desmin (+) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Mehregan 19925 | 58 | NA | F | Left thigh | Asymptomatic | A large linear, angiomatous and tender plaque | NA | Vascular channels lined by a single row of endothelial cells that infiltrated between collagen bundles throughout the dermis | Lack of nuclear atypia and mitoses | F-VIII-RA (±), VIM (±), UEA I (+) | Resolved spontaneously after 5 months | Incisional biopsy |

| Mehregan 19925 | 52 | 3 | M | NA | Asymptomatic | A soft, deep dermal growth cyst | 3.5 cm | A deep dermal and partially subcutaneous tumor composed of a proliferation of elongated endothelial cells lining collagen bundles and forming dilated vascular spaces | None abnormally large cells, mitotic figures, or nuclear atypia | F-VIII-RA (±), AAT (±), VIM (-) | NA | Excision |

| Renshaw 199347 | 60 | NA | F | Upper lip | NA | NA | NA | Freely anastomosing vessels beneath the epidermis, with a pattern of dissection of collagen fibers | None nuclear atypia, mitoses or prominent nucleoli | NA | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Herron 199421 | 40 | 40 | M | Right thigh | NA | A nontender, wellmarginated, red-brown, slightly raised plaque, with the surface lichenified with scattered flat-topped papules | 10 × 15 cm | Flattened, endothelium-lined channels and spaces permeated both papillary and reticular dermis | None cellular atypia | VIII (+), UEA I (+), CD34 (+), HLA-DR (+), ColIV (+), laminin (+), actin (+), ICAM-I (±), XIII (-), desmin (-), Ki-67 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Meunier 199448 | 30 | 16 | F | Right breast | Asymptomatic | Scattered yellowish papules with an ‘apple jelly’ appearance | Involve almost the entire breast | Many dilated, tortuous vascular channels lined by an hyperplastic endothelium; a ‘dissection of collagen’ appearance | Without cellular atypia | NA | Without any benefit | 1 mg/kg·d oral prednisolone for 4 months |

| Rosso 199511 | 49 | 1 | F | Left breast | Asymptomatic | A slightly raised, faintly red papular lesion; a lesion surrounded by several smaller papules; a pinkish papule | 0.5–1cm | An anastomosing network of thin-walled, bloodless vascular channels extended from papillary to reticular dermis dissecting collagen bundles | None atypical cells with pleoniorphic nuclei | F-VIII-RA (+), CD34 (±), UEA I (±), cyclin (-), Ki-67 (-) | Without recurrence at 23 months | Wide skin excision |

| Soohoo 199549 | 9 | 1 | M | Right knee | Asymptomatic | A violaceous macule with a central, slightly indurated brown papule | 2×1 cm | Anastomosing and discrete lymphatic channels lined with flattened endothelial cells; in areas had a “dissection of collagen” appearance | NA | F-VIII-RA (-), UEA I (+) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Kato 199619 | 52 | NA | M | Right thigh | Itch and pain | A reddish purple, slightly raised, well-demarcated plaque | 9.5 × 6.5 cm | Many irregularly shaped and dilated channels lined by a single layer of endothelium; some of the endothelial cells protruded into the vascular lumina; the vascular proliferation dissecting between collagen bundles | None cellular atypia and mitotic activity | vWF (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Grunwald 199716 | 68 | 5 | F | Right buttock | Asymptomatic | A well-demarcated, indurated, erythematous plaque | NA | Numerous vascular channels throughout the dermis; the channels becoming narrow in the reticular dermis, giving the appearance of “dissecting the collagen bundles” | None atypical cells | F-VIII-RA (+), UEA I (+), ColIV (±), desmin (±) | Marked improved | Intensive oral antibiotic therapy (ciprofloxacin and clindamycin) |

| Wilmer 199815 | 64 | 3 | M | Back (the lumbar area) | Asymptomatic | A solitary, irregular, oval shaped plaque with a well-defined border and scaly crusts | 2×4 cm | Subepithelial thin-walled vascular clefts, lined by a flat endothelium | Without cellular atypia or increased mitotic activity | CD31 (+), F-VIII-RA (+), SMA (+) | No recurrence after 18 months | Excision |

| Guillou 20008 | 17 | 8 | F | Chin | Asymptomatic | Slowly enlarging, fluctuant lump | Small | Anastomosing, angulated, and often widely dilated vascular spaces in the superficial dermis; vascular spaces dissecting the dermal collagen in an angiosarcoma-like fashion | None | F-VIII-RA (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), actin (+), desmin (+) | Recurrence at 7 months and 2 years; lost to follow up then on | Excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 78 | >2 | F | Posterior auricular area | Concomitant hair loss | Large, scaly, macular bruise-like lesion on back of head, occiput, and above and behind right ear | 10cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | Persistent lichen planus; dead of congestive heart failure at 7 months | Incisional biopsies (x2) |

| Guillou 20008 | 37 | NA | M | Mouth | Painful swelling | Hemorrhagic clinical appearance | 1.5cm | The same as the above | None | CD31 (+), EMA (-) | No evidence of disease at 40 months | Incisional biopsy in Nov’93; incomplete excisional biopsy in March’94 |

| Guillou 20008 | 71 | 15 | M | Left foot | Asymptomatic | Discolored, 1.4×3 cm hemangiomatous lesion | 2.6cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), actin (+) | NA | Incomplete excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 52 | 5~6 | F | Back of neck | Asymptomatic | Solitary asymptomatic bluish nodule with smooth surface | 1cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), actin (+) | No evidence of disease at 27 months | Excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 53 | 1.5 | F | Right forearm | Asymptomatic | Fluctuant, asymptomatic, irregular and smooth reddish-brown patch | 2cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | No evidence of disease at 12 months; keloid at the site of surgery at 6 months | Incisional biopsy, complete excision |

| Guillou 20008 | 30 | Childhood | M | Left breast | Asymptomatic | Small, nonitching, fluctuant, erythematous macule | 0.5cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | NA | Excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 65 | 0.16 | F | Left shoulder | Asymptomatic | Well-defined, slowly growing papule on shoulder with pigmentary incontinence | 0.3cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | No evidence of disease at 10 months | Excisional biopsy with free margins |

| Guillou 20008 | 56 | 2 | F | Face | Asymptomatic | Skin lesion | 1.5cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | No evidence of disease at 9 months | Excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 90 | 5 | M | Scalp | Profuse bleeding while combing hair | Smooth, brown, nonulcerated, slowly enlarging nodule of the scalp | NA | The same as the above | None atypical endothelial cells | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | No evidence of disease at 4 months | Excisional biopsy |

| Guillou 20008 | 27 | 27 | M | Back | Asymptomatic | Two faintly blue-brown, pigmented areas, of which one contained a 0.5-cm nodule | 7cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (-), CD31 (-), CD34 (-) | No evidence of disease at 36 months | Wide excision (8 x 4 cm) |

| Guillou 20008 | 75 | Recent | F | Left foot | Asymptomatic | Small macular lesions | 0.5cm | The same as the above | None | F-VIII-RA (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), actin (+), desmin (+) | NA | Excisional biopsy of one lesion |

| Sevila 200013 | 49 | 49 | M | Right thigh | Extreme pain; marked hyperesthesia resulting in functional limitation of the knee joint | Tender, indurated, and warm plaque, the surface of which was smooth with an erythemato-violaceous center and a bruiselike contusiform periphery | 17×12cm | Thin-walled vascular channels dissecting the collagen bundles extending from the mid dermis to subcutaneous fat; large and horizontally arranged vascular spaces at superficial levels and smaller at deeper ones | None evident nuclear atypia | F-VIII-RA (+), UEA I (+), VIM (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), ColIV (+) | Temporary improvement using predisone; no recurrence at 1 year | Prednisone 60 mg/day for 4 weeks; complete excision and split skin graft transplantation |

| Yiannias 200136 | 68 | NA | F | Right forearm | Asymptomatic | A light brown patch with a slightly rough texture, resembling pigmented actinic keratosis or lentigo | 2.4×1.0cm | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts in the upper dermis, with an overlying pigmented actinic keratosis | NA | UEA-I (+), vWF (-) | Without recurrence at 1 month | Excision |

| Hwang 200350 | 15 | 10 | M | Right foot | Slightly tender to palpation | Multiple erythematous, indurated coalescing plaques | 6cm | Numerous dilated, anastomosing vascular spaces dissecting between collagen bundles in the mid to reticular dermis | None cellular atypia or mitotic figures | NA | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Gengler 20076 | 44 | 0.6 | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | An erythematous plaque | 0.5cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 36 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 48 | 1.5 | F | Axilla | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.5cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 120 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 40 | NA | F | Axilla | Asymptomatic | One papule | 0.7cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 48 months, metastatic breast carcinoma | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 61 | 1 | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 81 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 44 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.3cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Dead of ovarian carcinoma at 152 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 51 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 54 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 67 | 0.25 | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | Multiple papules regressing spontaneously 3 months before development of a 6-mm nodule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Spontaneous regression 12 months after biopsy; alive without disease at 28 months | Incisional biopsy (with positive margins) |

| Gengler 20076 | 53 | 3.5 | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One stable nodule | 0.8cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 14 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 46 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.5cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Lost to follow up | Incisional biopsy (with positive margins) |

| Gengler 20076 | 53 | NA | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | One papule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 24 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 48 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive with disease at 65 months, no additional cutaneous lesions | Incomplete excision (R1) |

| Gengler 20076 | 75 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive with disease at 61 months, no additional cutaneous lesions | Incisional biopsy (with positive margins) |

| Gengler 20076 | 42 | NA | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | One cyst | 0.5cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive with disease at 36 months, no additional cutaneous lesions | Incisional biopsy (with positive margins) |

| Gengler 20076 | 52 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 7 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 53 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One papule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Lost to follow up | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 64 | 0.5 | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | One nodule | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 40 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 63 | 5 | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | Six papules present for 5 y; development of an additional 6-mm nodule | 0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 92 months | Incisional biopsy (with positive margins) (6-mm nodule) |

| Gengler 20076 | 52 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | Two nodules | 0.8cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Lost to follow up | Present on mastectomy specimen (recurrent breast carcinoma) |

| Gengler 20076 | 56 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | Two nodules | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | With nuclear/architectural atypia (1 nodule) | NA | Alive without disease at 67 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 57 | 2 | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | Six papules | 0.4cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 3 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 51 | 3.5 | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | Several papules | 0.7–1cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 64 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 50 | NA | F | Breast | Asymptomatic | Several papules | 0.3–0.6cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 8 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 61 | NA | F | Axilla | Asymptomatic | Several papules | 0.3–0.5cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive without disease at 6 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Gengler 20076 | 57 | NA | F | Chest wall | Asymptomatic | Multiple nodules | 0.2–0.3cm | Lymphangioendothelioma-like | None nuclear/architectural atypia | NA | Alive with persistent telangectasis at 88 months | Complete excision with negative margins |

| Kim 200722 | 7 | 7 | F | Left little toe | Asymptomatic | A slightly tender, flesh coloured mass | NA | Irregular, dilated vascular spaces lined by a single layer of bland, flat endothelial cells in the dermis | None cellular atypia | NA | No sign of local recurrence at 2 months | Complete excision with advancement flap for closure |

| Paik 200732 | 56 | 5 | M | Left cheek | Rare bleeding with minor trauma and occasional pruritus | A blanchable, violaceous, non-tender, soft plaque containing a few compressible papules | 2×7 cm | A proliferation of vascular spaces in the superficial and reticular dermis; more compressed vascular spaces with a pattern of dissection through the collagen in the deeper dermis | None mitotic figures | HHV-8 (-), CD31 (+), D2-40 (+) | NA | Incisional biopsy, close observation |

| Ando 200917 | 31 | 2 | F | Left lower leg; left abdomen; left knee | Left inguinal node swelling | An arborizing, reticulate reddish brown lesion along the postoperative scar of the left femur | 25 cm (left lower leg), 5 cm (left abdomen), 16cm (left knee) | Compressed vascular spaces in the deeper dermis, the appearance of “dissection of collagen bundles” | None atypia or mitotic changes | NA | NA | Skin biopsy |

| Lin 200933 | 33 | >1 | M | Right groin area | Frequent drainage of clear fluid sufficient to wet clothing | A soft, fluctuant subcutaneous nodule | 1 × 0.2 cm | Many irregularly dilated vascular channels throughout the dermis and dissecting the collagen bundles | None cellular atypia or mitotic figures | VIII (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+), HHV-8 (-) | Symptom-free after 9 months | Wide excision |

| Tong 201118 | 75 | NA | M | Right upper chest | Pruritus and occasional serous fluid discharge from minute breaks | An ill-defined scaly, slightly indurated, erythematous lesion | large | Multiple dilated, thin-walled, endothelial-lined channels in the superficial dermis | None endothelial atypia or mitotic activity | CD31 (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+) | Remained unchanged at 12 months | Incisional biopsy, no surgery |

| Revelles 201235 | 75 | 1 | M | Left back, left abdomen, pubic area | Asymptomatic | A large erythematoviolaceous, ill-defined, not indurated, multifocal bruise-like patches and violaceous areas | > 60 cm | Both papillary and reticular dermis permeated by irregular empty channels and spaces which were lined by a single layer of flat endothelial cells | None nuclear atypia or mitotic figures | CD31 (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+), Lyve-1 (+), Prox-1 (+), WT1 (+), HHV-8 (-), c-Myc (-), Ki-67 (-) | Died of disseminated aspergillosis at 8 months; no visceral vascular proliferation in autopsy | Incisional biopsy |

| Wang 201323 | 19 | 19 | F | Right thigh | Asymptomatic | A dull red patch | 20 cm | Prominent proliferation of anastomotic or retiform vessels dissecting the dermal collagen in the entire dermis | None pleomorphic cells and mitoses | D2-40 (+), Prox1 (+), Ki67 (-), WT-1 (-), HHV-8 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Wang 201323 | 27 | 7 | M | Left thigh | Exudation of watery clear liquid that looked like lymph at biopsy | A large brown plaque with no clear margin | 30 cm | The same as the above | None pleomorphic cells and mitoses | D2-40 (+), Prox1 (+), Ki67 (-), WT-1 (-), HHV-8 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Wang 201323 | 36 | 8 | F | Left thigh | Asymptomatic | A large red patch with unclear margin | 10 cm | The same as the above | None pleomorphic cells and mitoses | D2-40 (+), Prox1 (+), Ki67 (-), WT-1 (-), HHV-8 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Wang 201323 | 7 | 3 | M | Neck | Asymptomatic | A large red patch | 8 cm | The same as the above | None pleomorphic cells and mitoses | D2-40 (+), Prox1 (+), low Ki67, WT-1 (-), HHV-8 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Alkhalili 201425 | 47 | 0.5 | F | Left nipple | Itch and discomfort | A 7 mm asymmetrical outgrowth of the left nipple, without palpable masses and skin rash | 0.7cm | Ectatic vascular spaces lined by flattened, cytologically bland endothelial cells dissecting through the dermis | NA | NA | Resolved spontaneously | Incisional biopsy |

| Flores 201427 | 17 | High school | F | Right shoulder | Asymptomatic | A blanchable, light pink to slightly beige, nonindurated patch with reticulated borders | 16 × 11 cm | Interconnecting vessels lined with thin endothelium arranged horizontally and dissecting between dermal collagen bundles | None atypical cells or mitotic figures | D2-40 (+), CD31 (+) | Complete resolution after four PDL treatments; no appreciable change in the area treated with imiquimod | 585-nm pulsed dye laser; imiquimod |

| Hunt 201426 | 48 | Childhood | M | Left thigh | Asymptomatic | Dusky brown to bluish-red dermal papules | 10 × 10 cm | Thin, irregular vascular spaces with a lobular arrangement superficially and a more slit-like appearance deeper in the dermis | None endothelial cell atypia | HHV-8 (-) | The lesion decreased in size, lightened in color, and flattened after 7.5 months | Sirolimus |

| Yamada 20147 | 45 | 4 | F | Left arm | Chronic lymphedema of left arm | Multiple small and yellowish to reddish soft nodules | Nodules < 0.6 cm | Irregular, anastomosing vascular structures in the middle to lower layer of dermis; proliferating vascular channels dissecting dermal collagenous bundles in deeper dermis | Modestly atypical endothelial cells, but no apparent mitotic figures | CD31 (+), DAKO (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+), LYVE-1 (+), low Ki67, HHV-8 (-) | Partial remission and neogenesis for 7 years | Incisional biopsy |

| Zhu 201414 | 38 | 1 | M | Inguinal region | Asymptomatic | A neoplasm with a smooth lustrous surface and slight oozing | 2 × 2×5 cm | Epidermal hyperplasia; substantially dilated, thin-walled lymphatic vessels containing lymph fluid | Without koilocytes or atypical cells | D2-40 (+), HHV-8 (-), HPV-6 (-), HPV-11 (-) | Without recurrence at 5 years | Wide excision of the primary neoplasm, with the smaller surrounding lesions treated with cryotherapy |

| Mizuno 201520 | 42 | 42 | M | Inguinal region | Pain at night being sufficient to interrupt sleep | A indurated reddish-brown plaque with 3–5 mm diameter nodules | 12 × 7 cm | Irregular, horizontal slit-like spaces dissecting the collagen bundles in the dermis | None nuclear atypia | CD31 (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+) | Improved induration and color, and disappearance of pain and subcutaneous nodules under electron radiotherapy | Electron radiotherapy (total 20 Gy) for two weeks |

| Schnebelen 201530 | 73 | NA | M | Right flank | Drainage of clear to milky white fluid at punch biopsy | A large, soft, tuberous, supple, flesh-colored mass, with irregular and wrinkled surface contours | Occupying most of the right flank | Numerous anastomosing vascular channels dissecting through the dermal collagen from the superficial dermis to the subcutis, with vascular channels becoming less dilated and more slit-like as they delved deeper into the dermis | Free of cytologic atypia; no hobnailing, hyperchromasia and increased mitotic activity | HHV-8 (-), D2-40 (+), WT1 (-) | NA | Incisional biopsy |

| Vittal 201624 | 24 | 2 | F | Left leg | Asymptomatic | An ill-defined hyperpigmented, atrophic plaque, round to oval in shape | 3 × 3 cm | Horizontal, thin-walled vascular channels lined by single layer of bland endothelial cells at the dermo-epidermal junction | NA | NA | Mild improvement and exacerbation on stopping the treatment; no recurrence | Topical steroids for 6 months; excision |

| McKay 201712 | 83 | NA | F | Left back | NA | A small patch of thickening and scaliness | NA | Lymphangioendothelioma with no suggestion of malignancy | With no suggestion of malignancy | NA | Progressing to an angiosarcoma approximately 8 years later | Serial excision biopsies |

| Rudra 201751 | 8 | 1.5 | M | Left leg | Asymptomatic | An ill-defined, bluish, oblong-shaped plaque, studded with a few dark-blue and reddish papules | 4 × 3 cm | Compact hyperkeratosis with irregular acanthosis; dilated thin-walled spaces lined by intermittent flat endothelial cells resembling lymphatic channels in the upper and mid-dermis | NA | NA | No recurrence for 1 year | Completely excision |

| Salman 201728 | 5 | 0.16 | F | Right ankle | Asymptomatic | A slightly hyperkeratotic, brown to violaceous plaque with irregular borders | 5 cm | Delicate, thin-walled, endothelium-lined empty vascular spaces involving the superficial dermis and extending deep into the dermis | NA | D2-40 (+), CD31 (+), HHV-8 (-), low Ki-67 proliferation index (<1%) | A moderate response at 1 month; maintaining the initial response without any progression at 5 months | Imiquimod 5% cream three times per week |

| Larkin 201831 | 1 | 0.6 | M | Abdomen, penis, right scrotum, lower extremity | Episodic pain | A plaque with ecchymotic discoloration along the borders | 12 × 15 cm | Characteristic, ectatic, irregularly shaped vascular channels lined by flattened endothelial cells infiltrating the superficial and deep reticular dermis | NA | FLI-1 (+), CD34 (+), D2-40 (+), WT1 (-), HHV-8 (-), CD3 (-), CD20 (-). CD68 (-) | Lost to follow-up after 9 months | Incisional biopsy |

| Teixeira 202234 | 70 | 1 | F | Bilateral breasts | Asymptomatic | A yellow-brownish infiltrated plaque with superimposed flat papules | 60 cm | Slight acanthosis and irregular vascular spaces dissecting the collagen bundles lined by swollen endothelial cells | Without cellular atypia | D2-40 (+), CD31 (+), WT1 (+) | Remaining in follow-up | Incisional biopsy; wait-and-see approach |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; no evidence of disease, no evidence of disease.

The etiology of this benign lymphatic malformation remains unclear, but various triggering factors have been reported, including trauma,9,13,14 tick bites,15 surgery,16–18 femoral arteriography,19 cardiac catheter examination,20 radiation therapy6,7,11,12 and recurrent cellulitis.21 Our case adds to the evidence that trauma may be a predisposing factor for the development of BL. Additionally, there have been reports of BL developing from preexisting congenital vascular lesions.8,13,20–23 Kato et al19 proposed that traumatic obstruction of lymphatic circulation, if not sufficient to induce lymphedema, could lead to lymphatic proliferation and the formation of BL lesions. Inflammatory stimuli played a critical part in the genesis and rapid growth of BL, as demonstrated by the fact that the tumor may regress gradually with topical24 or systemic9,13 corticosteroid therapy. However, the role of inflammatory stimuli is controversial, with some studies suggesting that corticosteroid therapy is ineffective,21 and spontaneous recovery of the lesion has been reported in some cases.5,25 The role of immunity in the pathogenesis of BL is crucial, as Hunt et al26 reported that the plaque grew significantly under an immunosuppressive regimen of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. However, the response of different lesions to imiquimod, an immune response modifier, is perplexing.27,28 Another hypothesis regarding BL’s pathogenesis suggests that it may be a hamartoma of intermediately differentiated lymphatic vessels, blood vessels, and smooth muscle, given that lymphatic endothelial markers, various blood endothelial markers, type IV collagen, and desmin have been found to surround the vascular channels in many BL cases.29 In terms of the nature of BL, it is widely accepted that BL is a lymphatic vascular malformation rather than a true neoplasm, as demonstrated by the absence of WT-123,30,31 and D2-40 expression18,23,32–34 in endothelial cells. In the present case, positive D2-40 expression in endothelial cells further supports this view. Since the majority of evidence indicates that BL is a lymphatic malformation, sirolimus, which inhibits the incidence and progression of BL by targeting VEGFR-3, has been used to treat BL and has achieved satisfactory outcomes.26 However, some cases of BL with lesions larger than 60 cm have shown positive WT-1 expression,34,35 a marker of proliferation and neoplasia rather than a malformation, indicating that BL may develop a proliferative capacity in the slow enlargement process.

Jones3 summarized five features of BL that distinguish it from malignant angioendothelioma: (1) its development primarily in young individuals; (2) its sites of predilection are not limited to the face and scalp; (3) its lesion is usually localized and flat; (4) it has a slow growth and favorable prognosis; and (5) its so-called dissection of collagen appearance, channeled with a row of endothelial cells showing no obvious cellular atypicality. Of the 83 cases we found reported in the literature, most fulfill all but the first criterion. BL has been identified in virtually every age group, with the reported age of presentation ranging between 1 and 90 years, with a median age of 46.07 (the average time to diagnosis is around 6 years). It displays no sex predilection. The most commonly affected sites are the limbs (30% of cases), followed by the breast (24% of cases), head and neck (12% of cases), and other areas such as the abdominal wall, chest, back, shoulder, buttock, axilla, and groin. In contrast to most previous cases with localized, flat lesions, our patient had a slightly tender, protuberant, flesh-colored mass with cyanotic vesicles. BL criteria should allow for morphological variability, with some cases presenting as nodular mass,30 actinic keratosis-like lesion,36 condyloma acuminatum,14 and even without a visible mass or rash.25 BL can grow to a large size, with a maximum diameter of 65 cm reported in one case.35 Patients are generally asymptomatic, but occasionally, pain (sometimes extreme13), pruritus, swelling, and tenderness have been reported. Our patient experienced consistent watery clear liquid exudation after debridement, which is a symptom that has been observed in several other cases.14,18,23,30 The lymph-like fluid in our case may have seeped from ulceration, potentially exacerbating the infection. On a histological level, BL is characterized by the irregular proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels dissecting between bundles of dermal collagen. These findings can be limited to the papillary dermis but may extend into deeper subcutaneous tissue. Vascular channels are lined by a monolayer of endothelial cells, with no mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism. As shown in Table 3, significant quantities of endothelial cells were only observed in eight of the 83 cases.6,7,37 Usually, extravasated red cells and hemosiderin deposition, as well as marked inflammation, are rarely observed, indicating a predominant involvement of lymphatic channels. This is further supported by positive immunohistochemistry for lymphatic-specific markers such as D2-40. Results of immunohistochemistry for other lymphatic or vascular endothelium markers such as Factor VIII (F-VIII-RA), Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA-I), CD 31, CD 34, LYVE-1, and PROX-1 were inconsistent (Table 3), although some studies suggest that BL may be differentiated from other lymphatic skin tumors by negative staining for F-VIII-RA and strong staining for UEA-I.21 All evidence suggests that BL is a heterogeneous disease. It is more of a pathological diagnosis than a clinical one, and we should allow for more etiological, morphological, and immunohistochemical diversity in the identification of BL.

BL is a rare lymphatic vascular proliferation that can be mistaken for various benign and malignant conditions arising from vessels. In this case report, the patient had previously been diagnosed with hemangioendothelioma, lymphangiomatosis, and BL. Upon the review of histopathology slides, the differential diagnoses included well-differentiated cutaneous angiosarcoma, hemangioendothelioma, lymphangiomatosis, and Kaposi’s sarcoma in the patch stage. Lymphangiomatosis is a rare disorder that is characterized by multifocal lymphangioma involving multiple organs such as the skin, superficial soft tissue, and abdominal and thoracic viscera in 75% of cases. In the remaining 25% of cases, it presents as diffused pulmonary lymphangioma (DPL).38 Compared to BL, lymphangiomatosis is mainly observed in children and is rarely diagnosed in patients over the age of 20, with over 75% of cases presenting with multiple bone lesions. In the case discussed in this report, the patient, who was 25 years old, experienced a progressive lower extremity lesion after previous trauma that did not reach the bone, indicating a diagnosis of BL rather than lymphangiomatosis. A definitive diagnosis of lymphangioendothelioma requires histopathological examination to distinguish it from other forms of lymphangioma, which usually show superficially dilated vascular spaces that become progressively smaller with deep extension.5,31,39 Lymphangiomatosis shares similar histological features with the deep portions of BL, characterized by a single layer of flattened endothelium that ramifies in the soft tissue.40 Considering portions of BL are virtually indistinguishable from lymphangiomatosis, Guillou et al8 believed that BL may be considered a localized form of lymphangiomatosis, and the distinction between the two is best made based on presentation and pathological extent. In lymphangiomatosis, as opposed to BL, the dilated lymphatic spaces involve not only the dermis but also the subcutaneous tissue and, occasionally, the underlying fascia and skeletal muscle.40 In the present case, the mass spread beneath the dermis and invaded subcutaneous fat but did not reach the striated muscles. Based on the clinical manifestations and infiltration depth of the lesion, a diagnosis of BL was preferred over lymphangiomatosis, even though it might be a multifocal disease.

Kaposi’s sarcoma in patch stage, which shares a red-violaceous macular appearance and lymphangioma-like cell dissection of collagen with BL, can be identified histologically by the presence of erythrocytes and spindle cells, hemosiderin deposits, plasma cells, and positive anti-HHV8 immunostaining.15,41 Differential diagnosis from well-differentiated angiosarcoma is particularly important as BL shares the histopathological presence of extensive dissection of collagen bundles with angiosarcoma. Angiosarcoma may clinically manifest as red-blue nodules or plaques that can ulcerate in the face or scalp of elderly individuals or lymphedematous extremities. BL differs from angiosarcoma in its lack of anastomosing and infiltrating vascular structures, mitosis, prominent nuclear pleomorphism or mitotic figures, and Ki-67 amplification in less-differentiated areas.7,13,42 Yamada et al7 demonstrated that the MIB-1 labeling index could be helpful as a supplement to the diagnosis of cutaneous BL, particularly when specimens are inadequate. However, differentiating lymphangioendothelioma from angiosarcoma remains challenging. Sevila13 suggested that some previously reported cases of angiosarcoma may actually be benign tumors similar to BL, as they were curable in children and young adults. Therefore, the diagnosis of BL should be used with caution, especially in cases of post-irradiation lesions in adults, as this condition is known to be a precursor to the development of angiosarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.12,43 Audard et al43 even questioned the existence of BL. Hence, careful sampling of such lesions, close correlation of pathological findings with clinical characteristics, and close follow-up care are necessary.

The radiological findings in the present case were typical and quite helpful for the diagnosis and assessment of giant BL before surgery. Lymphoscintigraphy, with subcutaneously injected 99mTc-DX, effectively imaged the lymphatic malformations, enabling a good differential diagnosis from hemangioma or benign hemangioendothelioma and a good assessment of lymphatic uptake, distribution, and retention. The MRI findings were similar to those of hemangiomas, but no signal voids caused by high-flow vessels were observed.40 MRI also helped assess tumor extent, making a valuable contribution to surgery. In the present case, scattered lesions with increased signal density superior to the deep fascia were found on MRI, corresponding to the final pathological result. Ultrasonography can also be useful for localizing and determining the cystic nature of some types of lymphangioma. The imaging examinations allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the nature and extent of the lesion.

Regarding the treatment, the differentiation between lymphangiomatosis and lymphangioendothelioma was not necessary. The main concern was whether the lesion was benign and had the potential for malignant transformation, which would determine if lymph node dissection was required. Due to the patient’s history of clear fluid drainage and the tendency for the mass to infiltrate peripheral subcutis, a type of infiltrating lymphatic malformation with a risk of recurrence was suspected. Despite its penchant for infiltrating peripheral subcutis, the mass showed no signs of invading deeper tissue planes or metastasizing, indicating that the lesion was benign. Given that the lesion had reached the subcutaneous fat and that the patient had undergone two incomplete debridements before admission, thorough surgical excision was the preferred treatment. According to MRI results, the lesion had spread into subcutaneous fat but did not reach the deep fascia, so a complete excision from the skin to the superficial fascia was necessary. The wound boundary was visible to the naked eye, and the scope of the surgery was expanded to ensure a negative margin. Because of the numerous lymphatic fistulas and infections, the temporary coverage by VSD was an important part of the treatment protocols through the application of a controlled and localized negative pressure on porous polyurethane absorbent foams. By controlling infection, calculating the volume lymph fluid, improving lymphorrhea, accelerating tissue granulation, minimizing exposure of deep tissues, and increasing the survival rate of graft transplants for soft-tissue defects, the negative pressure technique played an important role in the protection of a large wound in the lower leg.44 The volume of lymph-like fluid decreased significantly after two surgeries, and the wound no longer exhibited signs of potential sepsis, indicating that skin grafting was possible. Split-thickness skin grafting was chosen after the wound was covered with fresh granulation tissue and showed no evidence of infection. Compared to skin flap, STSG was preferred as it was more effective in preventing recurrent lymphatic malformations since it had less reticular dermis and thus fewer lymphatics. In addition, the patient’s overweight (with a BMI of 28.34) and the wound size made skin flap transplantation risky. Furthermore, the transplantation of the flap from the thigh to the calf might generate morphological issues in the lower leg if microscopic anastomosis was performed. Given the above points, we eventually chose split-thickness skin graft, and we managed to achieve a good functional and cosmetic result. Moreover, medications such as sirolimus, imiquimod, glucocorticoids, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective when surgical excision is not possible due to the size and location of the lesion.9,26,28,45 Positive WT-1 immunostaining indicates a proliferative vascular lesion that requires appropriate therapy such as systemic steroids or interferon, whereas negative results indicate a vascular malformation that does not require unnecessary systemic therapy.35 Interestingly, antibiotic therapy was also effective.16 Since partial or complete spontaneous remission has been documented in some cases,5 therapeutic abstention and pharmaceutic treatment could be reserved for patients when surgery is contraindicated due to the size or location of the lesion.

Conclusion

We have discussed a case of benign lymphangioendothelioma that progressed to a persistent exudative wound after two incomplete excisions. Clinicopathological correlation, imaging examination, and pathological examination are essential for diagnosing BL and excluding lymphangiomatosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and angiosarcoma. This case also demonstrates that complete excision and split-thickness skin graft transplant following vacuum-seal drainage is an effective course of treatment for recurrent BL. Additionally, by reviewing the literature on BL, we concluded that BL is more of a pathological diagnosis than a clinical one, and we should allow for more etiological, morphological, and immunohistochemical diversity in the identification of BL.

Funding Statement

This study was financially supported by the National Major Disease Multidisciplinary Diagnosis and Treatment Cooperation Project (No.1112320139) and the National clinical key specialty construction project (23003). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The Ethics Committee of the hospital approved the use of the clinical data of the patient. Consent had been obtained from the patient to use pictures, notes and lab investigations for publication on the condition that the personal information was kept confidential.

Consent for Publication

The consent for publication has been obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jones EW, Feiwel M. Malignant angio-endothelioma. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56(4):299–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson Jones E. Malignant vascular tumours. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1(4):287–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1976.tb01435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones EW. MALIGNANT ANGIOENDOTHELIOMA OF THE SKIN. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76(1):21–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb13970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold SC. Angioendothelioma (lymphatic type). Br J Dermatol. 1970;82(1):92–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehregan DR, Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA. Benign lymphangioendothelioma: report of 2 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19(6):502–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1584–1598. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada S, Yamada Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Post-mastectomy benign lymphangioendothelioma of the skin following chronic lymphedema for breast carcinoma: a teaching case mimicking low-grade angiosarcoma and masquerading as Stewart-Treves syndrome. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:197. doi: 10.1186/s13000-014-0197-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1047–1057. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200008000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe M, Kishiyama K, Ohkawara A. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(5):663–667. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70076-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A. The SCARE 2020 Guideline: updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22(2):164–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb01401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKay MJ, Rady K, McKay TM, McKay JN. A radiation-induced and radiation-sensitive, delayed onset angiosarcoma arising in a precursor lymphangioendothelioma. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(6):137. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.03.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sevila A, Botella-Estrada R, Sanmartín O, et al. Benign lymphangioendothelioma of the thigh simulating a low-grade angiosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):151–154. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200004000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu JW, Lu ZF, Zheng M. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in the inguinal area mimicking giant condyloma acuminatum. Cutis. 2014;93(6):316–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilmer A, Kaatz M, Mentzel T, Wollina U. Lymphangioendothelioma after a tick bite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(1):126–128. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70416-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunwald MH, Amichai B, Avinoach I. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):656–657. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70192-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando K, Watanabe D, Takama H, Tamada Y, Matsumoto Y. Acquired progressive lymphangioma with atypical clinical presentation. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(1):82–83. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong PL, Beer TW, Fick D, Kumarasinghe SP. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in a 75-year-old man at the site of surgery 22 years previously. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2011;40(2):106–107. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V40N2p106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato H, Kadoya A. Acquired progressive lymphangioma occurring following femoral arteriography. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(2):159–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1996.tb00044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuno K, Okamoto H. Benign lymphangioendothelioma on a vascular birthmark following examination of a cardiac catheter. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(7):e273–4. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herron GS, Rouse RV, Kosek JC, Smoller BR, Egbert BM. Benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 Pt 2):362–368. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, Kim JW, Yu DS. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(3):416–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Chen L, Yang X, Gao T, Wang G. Benign lymphangioendothelioma: a clinical, histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of four cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(11):945–949. doi: 10.1111/cup.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vittal NK, Kamoji SG, Dastikop SV. Benign Lymphangioendothelioma - A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):Wd01–2. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2016/15664.7155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alkhalili E, Ayoubieh H, O’Brien W, Billings SD. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the nipple. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014(sep22 1):bcr2014205966–bcr2014205966. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunt KM, Herrmann JL, Andea AA, Groysman V, Beckum K. Sirolimus-associated regression of benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(5):e221–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flores S, Baum C, Tollefson M, Davis D. Pulsed dye laser for the treatment of acquired progressive lymphangioma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(2):218–221. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salman A, Sarac G, Can Kuru B, Cinel L, Yucelten AD, Ergun T. Acquired progressive lymphangioma: case report with partial response to imiquimod 5% cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(6):e302–e304. doi: 10.1111/pde.13283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu WY, Penneys NS, Reyes B, Khatib Z, Schachner L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(5 Pt 2):813–815. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70120-q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnebelen AM, Page J, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Benign lymphangioendothelioma presenting as a giant flank mass. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42(3):217–221. doi: 10.1111/cup.12453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larkin SC, Wentworth AB, Lehman JS, Tollefson MM. A case of extensive acquired progressive lymphangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(4):486–489. doi: 10.1111/pde.13486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paik AS, Lee PH, O’Grady TC. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in an HIV-positive patient. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(11):882–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin SS, Wang KH, Lin YH, Chang SP. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in the groin area successfully treated with surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(7):e341–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teixeira D, Canelhas Á, Costa M, Magalhães C, Ferreira EO, César A. Giant benign lymphangioendothelioma with positive expression of Wilms tumor 1: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49(1):86–89. doi: 10.1111/cup.14125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Revelles JM, Díaz JL, Angulo J, Santonja C, Kutzner H, Requena L. Giant benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(10):950–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yiannias JA, Winkelmann RK. Benign lymphangioendothelioma manifested clinically as actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2001;67(1):29–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tadaki T, Aiba S, Masu S, Tagami H. Acquired progressive lymphangioma as a flat erythematous patch on the abdominal wall of a child. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(5):699–701. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1988.01670050043017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3):1037–1046. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9904056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindberg MR. Diagnostic Pathology: Soft Tissue Tumors. Springer Science & Business Media; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Folpe AL. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. Elsevier Health Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cossu S, Satta R, Cottoni F, Massarelli G. Lymphangioma-like variant of Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic study of seven cases with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199702000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elder DE. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Audard V, Lok C, Trabattoni M, Wechsler J, Brousse N, Fraitag S. Misleading Kaposi’s sarcoma: usefulness of anti HHV-8 immunostaining. Ann Pathol. 2003;23(4):345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleischmann W, Strecker W, Bombelli M, Kinzl L. Vacuum sealing as treatment of soft tissue damage in open fractures. Der Unfallchirurg. 1993;96(9):488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tronnier M, Lommel K, Haselbusch D. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in a 13-year-old boy. Hautarzt. 2021;72(7):610–614. doi: 10.1007/s00105-020-04728-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones EW, Winkelmann RK, Zachary CB, Reda AM. Benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2 Pt 1):229–235. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70203-t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renshaw AA, Rosai J. Benign atypical vascular lesions of the lip. A study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(6):557–565. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199306000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meunier L, Barneon G, Meynadier J. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131(5):706–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04988.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soohoo L, Mercurio MG, Brody R, Zaim MT. An acquired vascular lesion in a child. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(3):341–2, 344–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690150107022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang LY, Guill CK, Page RN, Hsu S. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 Suppl):S250–1. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00448-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudra O, Ghosh A, Ghosh SK, Bhunia D, Mandal P. Benign Lymphangioendothelioma: a Report of a Rare Vascular Hamartoma in a Young Indian Child. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(5):528–529. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_416_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]