Patient care and outcomes are cornerstones of decision making in health care systems. Civility, collaboration, and mutual respect among workforce members are vital for the overall success of health care delivery to patients. Cohesive health care teams and effective communication influence health care delivery positively.1 However, mutual respectful interaction is not always present in the health care workplace. This is underscored by the Global Prevalence and Impact of Hostility, Discrimination, and Harassment in the Cardiology Workplace survey, which found that of 5,931 cardiologists (77% men; 23% women), 44% reported an adversarial work culture, and 79% of those working in a hostile work environment reported adverse effects on professional activities with colleagues and patients. Women and Black cardiologists were more likely to report hostile environments (68% vs 37%; OR: 3.58 women vs men) and (53% vs 43%; OR: 1.46 Blacks vs Whites).2 The publication of the 2022 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Health Policy Statement on Building Respect, Civility, and Inclusion in the Cardiovascular Workplace outlines solutions and provides resources when addressing these institutionally engrained issues.3 Cultures are flawed with microaggressions, macroaggressions, blatant disrespect, or discrimination that require institutional change and individual accountability. The well being of all health care staff has become a focus to improve work satisfaction, deter burnout, and ultimately deliver better quality and more equitable patient care.

Historically, bias, discrimination, bullying, and harassment (BDBH) in the health care workplace did not receive attention for a multitude of reasons. The road to becoming a cardiologist and other subspecialties in medicine is long and grueling with an expectation to “grin and bear it.” Although BDBH exists in many forms, many hesitate to report these experiences for fear of retribution. For cardiology, like many specialties, the hierarchical system in medical school persists throughout training and encourages many to remain silent. Although these issues affect daily life for those who experience them, they also lead to career-related repercussions and decreased quality of life for health care professionals and their patients. The consequences of BDBH include mental health conditions that were prevalent in nearly one-third of survey respondents in a recent global survey of practicing cardiologists and were more often present in early career cardiologists and those experiencing emotional harassment or discrimination.4 These statistics constitute a need for significant and coordinated actions to change the current culture within cardiology.

In this paper, the authors provide a practical guide with suggested approaches for addressing bullying or harassment in the workplace.

Bullying and Incivility

Bullying and incivility from senior leadership present a difficult scenario for the affected individuals and the institution as a whole. For example, when cardiologists become leaders in a particular field, have large-volume practices, and are known for innovative techniques and high-quality research, they may feel empowered to treat others who work for them with incivility. “Having a temper,” displaying erratic behavior in the workplace, and using disrespectful language are ways individuals may display incivility.

Many of us have seen this either in training or while in practice. These attitudes and behaviors are active bullying and uncivil behavior, which are unacceptable regardless of the power or status of the perpetrator. They lead to low job satisfaction, burnout, and—importantly—constitute a threat to patient safety. Witnesses should be upstanders rather than bystanders. Upstanders speak up in the moment and stop the perpetuity of bullying and chain of abuse. The silence of bystanders, which may be driven by a fear of repercussion, may also indicate tolerance to the witnessed uncivil behavior. To support upstanders, health care systems should implement safety event monitoring and reporting systems with processes to preserve anonymity and ensure that those who lack power are protected from retaliation. Institutional cultures can also perpetuate bullying by elevating a person who bullies to the top of the power chain. Therefore, culture change must start with leadership involvement and example.

Cardiology leaders need to internalize that these attitudes affect patient care and act promptly to promote patient safety and a culture of respect for workers. When such systems fail, other societal platforms and social media can be used to bring attention to issues that were previously swept under the rug by traditional hierarchical structures and provide a voice and audience for those who are denied of respect and opportunities. Although this may have adverse personal repercussions, the current generation often use these platforms to highlight workplace bullying and harassment and propel change through public pressure and scrutiny.

Sexism and Gender Disparities

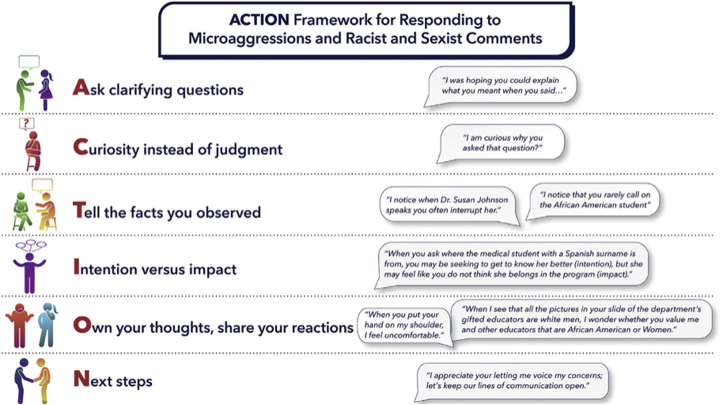

Sexism and gender disparities are prevalent in cardiovascular medicine, often going unnoticed and accepted as “normal.” Childbearing and childrearing are often flashpoints for exacerbation of these disparities in the workplace. Women are often questioned about their career choices and the possible repercussions on reproductivity and childrearing. Women who choose cardiology as a career, characterized by high call demand and exposure to radiation, are frequently asked why they would choose a career that could threaten their pregnancies or ability to see their children. These experiences illustrate sexism and misogynistic behavior and perpetuate gender disparities in cardiovascular medicine, even if they are meant to be protective (ie, benevolent sexism). Benevolent sexism stems from an often well-intended attempt to shield women from perceived harm or hard work, but the decisions or advice that affect them do not consider the will and goals of the woman herself. An essential concept in addressing this type of bias is recognizing women’s ability, agency, and autonomy to make decisions about their lives, careers, and reproduction. Upstanders can offer allyship by commenting assertively and supporting whatever the woman aspires to achieve. Finally, institutional leaders must engage in conversations with mentors or other personnel to correct the behavior. The ACTION (Ask clarifying questions; Curiosity instead of judgment; Tell the facts you observed; Intention vs impact; Own your thoughts, share your reactions; Next steps) framework highlights some of the recommended strategies to use in situations of benevolent sexism and gender bias.3,5

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are another form of bullying that affects careers negatively and can take many forms.6 Prominent examples include treating colleagues preferentially based on sexual orientation, ethnicity, or religious preference or even mispronouncing a colleague’s name with no intention to learn the proper way. Microaggressions, when repeated, can have as negative an effect as overt racism and sexism and promote a toxic work environment.6 Microaggressions are more prevalent in workplaces with high occurrences of BDBH and in those that lack diversity and inclusion.6 Witnesses have the opportunity to become upstanders by opting to intervene or offering nonverbal cues (ie, staring; not nodding in agreement). Broadening our perspectives by getting to know individuals from diverse backgrounds can lead to an inclusive mindset, but significant leadership involvement is needed to implement a culture of genuine inclusion. Institutional training can help increase awareness of unconscious biases.6

Conclusions

Bullying and harassment are common in the health care workplace, and appropriate interventions by individuals and organizations are needed to avoid perpetuating these harmful behaviors. Some of the strategies listed here have been highlighted by the ACTION framework for responding to microaggressions and sexist comments (Figure 1).3,5 A summary of the key analyses and action plans focused on areas of bullying, incivility, benevolent sexism, gender bias, and microaggressions are also outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Outline of the ACTION Framework Proposed by the American College of Cardiology for Responding to Microaggressions, Racist, and Sexist Comments

Adapted with permission from Douglas et al.3

Table.

Summary of the Key Analyses and Action Plans Focused on Areas of Bullying, Incivility, Benevolent Sexism, Gender Bias, and Microaggressions

| Key Analysis | Action Plan | |

|---|---|---|

| Bullying and incivility | This results in low job satisfaction, burnout, and constitute a threat to patient safety. |

|

| Benevolent sexism and gender bias | Sexism and misogynistic behavior perpetuate gender disparities in cardiovascular medicine |

|

| Microaggressions | Overt racism and sexism promote a toxic work environment. Microaggressions are more prevalent in workplaces with high occurrences of BDBH as well as in those that lack diversity and inclusion. |

|

BDBH = bias, discrimination, bullying, harassment.

The burden of change should not be solely on the individual or individual institutions, but rather national leaders and societies should spearhead this sorely needed change, as “we are what we tolerate.”

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Costello has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk; and has served on the medical advisory board for Prism Care. Dr Reza has received speaking honoraria from Zoll, Inc; and consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics. Dr Tamirisa has served as speaker for Abbott and Medtronic; and has received consultant fees from Sanofi. Dr Mieres has served on the medical advisory board of 98point6 Inc and Atria Academy. Dr Volgman has served as a consultant for Sanofi, Pfizer, Merck, and Janssen; has participated in clinical trials for Novartis and NIH; and holds stock in Apple Inc. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Sorensen D., Cristancho S., Soh M., Varpio L. Team stress and its impact on interprofessional teams: a narrative review. Teach Learn Med. 2023;10:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2022.2163400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma G., Douglas P., Hayes S., et al. Global prevalence and impact of hostility, discrimination, and harassment in the cardiology workplace. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(19):2398–2409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douglas P.S., Mack M.J., Acosta D.A., et al. 2022 ACC health policy statement on building respect, civility, and inclusion in the cardiovascular workplace: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(21):2153–2184. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(22)03144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma G., Rao S., Douglas P., et al. Prevalence and professional impact of mental health conditions among cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(6):574–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza T. Responding to microaggressions in the classroom: taking ACTION. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-classroom-management/responding-to-microaggressions-in-the-classroom/

- 6.Poorsattar S.P., Blake C.M., Manuel S.P. Addressing microaggressions in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2021;96:927. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]