Abstract

A 65-year-old obese woman with rheumatic heart disease and restrictive lung disease presented with decompensated heart failure. Evaluation demonstrated severely thickened mitral valve leaflets, severe mitral stenosis, and moderate mitral regurgitation. She underwent successful transfemoral transseptal transcatheter mitral valve replacement with a dedicated valve resulting in improved functional status. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Key Words: mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis, TMVR

Central Illustration

History of Presentation

A 65-year-old obese woman with rheumatic heart disease (RHD), paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and restrictive lung disease requiring chronic oxygen therapy (FEV1 and DLCO were 51% and 35% of predicted, respectively) presented with declining functional status (NYHA functional class III symptoms, ambulating with a walker). The physical examination was remarkable for a body mass index of 43.8 kg/m2 and a diastolic heart murmur. She underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrating severe mitral stenosis (MS) and moderate mitral regurgitation (MR). There was no other significant valvular disease evident. The patient was high-risk for surgery because of the severity of her lung disease, obesity, and frailty (poor grip strength, ambulating 60 m on 6-min walk test). Thus, after discussion with a multidisciplinary heart team, she was submitted for consideration of transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) with the Cephea Transseptal Mitral Valve System (Abbott Vascular).

Learning Objectives

-

•

To understand new opportunities for the management of rheumatic mitral valve disease.

-

•

To demonstrate utilization of a novel TMVR system in rheumatic mitral stenosis.

Past Medical History

The patient’s additional medical history includes former tobacco abuse, prior pulmonary embolism, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Investigations

The patient’s blood work was within normal limits except for an elevated N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide level (1,351 pg/mL). There was no coronary artery disease by angiography. The TTE demonstrated a mean mitral valve gradient of 13 mm Hg, an estimated mitral valve area of 1.2 cm2, and grade II MR (Table 1). There was prominent subvalvular thickening causing restriction of the leaflet tips with a Wilkins’ score of 9.

Table 1.

Screening Transthoracic Echocardiogram

| LVEF, % | 66 |

| LVEDD, mm | 47 |

| LVESD, mm | 33 |

| Peak mitral valve gradient, mm Hg | 37.5 |

| Mean mitral valve gradient, mm Hg | 13.4 |

| MR EROA, cm2 | 0.25 |

| Forward stroke volume, mL | 80.9 |

| MR regurgitant volume, mL | 45.7 |

| MR regurgitant fraction, % | 58 |

| LVOT peak gradient, mm Hg | 4.3 |

| LVOT mean gradient, mm Hg | 2.0 |

EROA = estimated regurgitant orifice area; LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD = left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; MR = mitral regurgitation.

A cardiac computed tomography analysis was performed to assess for anatomic suitability and procedural planning (3mensio, Pie Medical) (Table 2, Figure 1). The predicted neo-left ventricular outflow tract was considered sufficient.

Table 2.

Cardiac Computed Tomography Analysis

| Systole | Diastole | |

|---|---|---|

| Annulus area, cm2 | 10.5 | 10.0 |

| Annulus perimeter, mm | 119.5 | 115.4 |

| C-C diameter, mm | 40.0 | 38.3 |

| A-P diameter, mm | 30.2 | 30.3 |

| T-T distance, mm | 25.3 | 25.3 |

| Atrial septum height, mm | 46.9 | 46.6 |

| LVOT area, mm2 | 455.0 | 454.2 |

| Neo-LVOT, mm2 | 168.9 | 184.9 |

A-P = anterior-to-posterior; C-C = commissure-to-commissure; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; T-T = trigone-to-trigone.

Figure 1.

Cardiac Computed Tomography Preprocedural Planning

(A) Mitral annulus dimensions. (B) Three-chamber view demonstrating thickened posterior chordae. (C) Cephea-specific virtual valve predicted position. (D) Predicted neo-left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT). (E) Transseptal and catheter planning predicted a transseptal puncture height of 41 mm above the mitral annulus. (F and G) The transseptal catheter path was predicted to be mid and posterior on the fossa. (H) The computed tomography–generated fluoroscopic projection for valve deployment.

Management

The patient’s anatomy was suitable for treatment with the transseptal TMVR System (36-mm valve). The bioprosthesis consists of atrial and ventricular self-expanding Nitinol discs with a central bovine trileaflet valve. The valve is under early feasibility investigational use in the United States for treatment of symptomatic patients with grade ≥3+ MR in patients who are high surgical risk (NCT05061004). Given that this patient had predominantly rheumatic MS and was not a candidate for approved transcatheter or surgical mitral valve therapies, she was treated under compassionate use, as approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and local Institutional Review Board requirements.

TMVR implantation was performed in November 2022 using fluoroscopic and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) guidance. The intraprocedural TEE showed severe MS and moderate-to-severe MR (Figure 2). Transfemoral venous access was obtained via surgical cutdown. After transseptal puncture and balloon septostomy (12-mm balloon), the 40-F introducer sheath was advanced into the inferior vena cava. The 36-F delivery system was tracked over a dedicated 0.032-inch preshaped wire and navigated to the center of the mitral annulus. After positioning the distal edge of the loaded valve 15 to 20 mm below the mitral annulus, the valve was unsheathed starting with the ventricular disc. Once the atrial disc was deployed, the delivery system was removed. Following valve implantation, the patient was hemodynamically stable; however, echocardiography and fluoroscopy revealed partial expansion of the inner frame supporting the leaflets of the prosthesis, associated with abnormal leaflet motion. Therefore, postdilation was performed with a 25-mm True balloon (Bard Peripheral Vascular) resulting in improved expansion of the inner frame and normalized leaflet function (Figures 3 and 4). The venous access site was closed surgically.

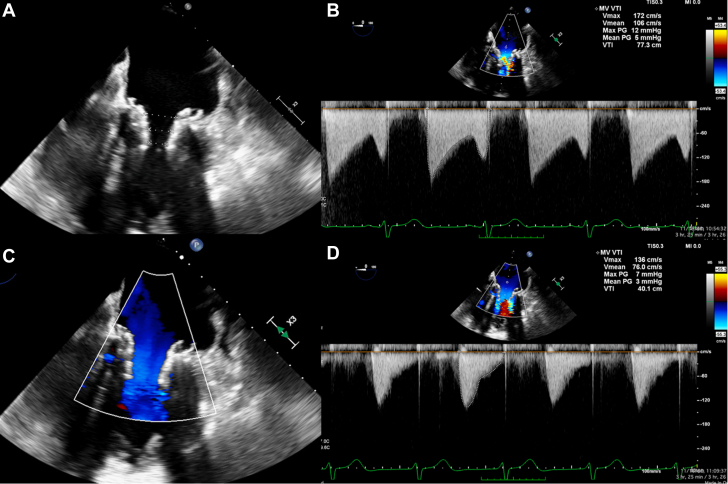

Figure 2.

Baseline TEE Imaging

(A) Three-chamber view showing restricted opening of the mitral leaflets. (B) Continuous wave Doppler demonstrating a peak mitral gradient of 17 mm Hg and mean gradient of 8 mm Hg. (C) Flow acceleration through the mitral valve into the left ventricle during diastole. (D) X-plane imaging demonstrating moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation. (E and F) Three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiogram imaging of the mitral valve from the left atrial view during systole and diastole.

Figure 3.

Transseptal Procedural Steps: Illustration and Fluoroscopic Representative Images

(A) The valve delivery system is inserted over a dedicated wire. (B) First, the valve is unsheathed until the tines are exposed (yellow arrows). (C) After depth confirmation, the ventricular disc is unsheathed. (D) After complete valve deployment, the ventricular disc appeared underexpanded. (E) Postballoon dilation is performed. (F) Final ventriculogram demonstrates excellent valve function and absence of mitral regurgitation.

Figure 4.

Intraprocedural Transesophageal Echocardiography Imaging

(A and B) After valve deployment, underexpansion of the valve frame resulted in tapering of the inner frame from 17.2 mm (atrial) to 9.7 mm (ventricular). The peak and mean mitral valve (MV) gradients were 12 and 5 mm Hg, respectively. (C and D) Following postdilation, there was improved frame expansion, with a final mean MV gradient of 3 mm Hg. PG = pressure gradient; VTI = velocity time integral.

Postimplant TEE demonstrated excellent bioprosthetic valve function without central or paravalvular leak, and a mean mitral valve gradient of 3 mm Hg (Figure 4). There was no significant left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. A 5.1-mm atrial septal defect with left-to-right shunting remained.

The patient’s recovery was uncomplicated. She was extubated in the operating room and required no vasopressor support. Anticoagulation with coumadin therapy was started on postprocedure day 1 and will continue lifelong. TTE imaging before discharge remained unchanged. She was discharged home in a clinically stable condition on postprocedure day 5.

Discussion

RHD most commonly affects the mitral valve and results predominantly in MS. Treatment options include percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty (PBMV), open commissurotomy, and surgical replacement.

If the anatomy is suitable for PBMV, patients have good 10-year functional outcomes and an approximate doubling of mitral valve area.1 PBMV suitability is dependent on valve morphology and cautioned against if greater than moderate MR is present. Generally, patients with a Wilkins’ score of <9, commissural fusion and less subvalvular disease have the best outcomes.2 In this case, PBMV was not considered an option before subvalvular thickening with presence of chordal calcification, minimal commissural fusion, and the pre-existing MR. She was not a candidate for surgical MV replacement; thus, TMVR was explored as an alternative.

TMVR has not been studied in rheumatic MS patients who are suboptimal PBMV candidates. Although there is growing experience with the use of a balloon-expandable TAVR device in the mitral position in patients with mitral annular calcification, this device may not anchor reliably in patients with rheumatic MS as they typically lack adequate annular calcification.3

Currently a number of TMVR devices are being studied in clinical trials for patients with symptomatic MR.4 Consistent with this, the prior TMVR implants with this system have been in symptomatic MR patients.5,6 To our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient with rheumatic MS who was successfully treated with a transseptal TMVR device. This may open a new avenue for treatment of high-risk surgical patients who experience inadvertent significant MR after PBMV. In addition, TMVR with the device described here may expand the percutaneous treatment options for RHD patients with high Wilkins’ scores.

Follow-up

At 30-day clinical follow-up, the patient reported functional improvement and denied any significant cardiac symptoms. TEE demonstrated a stable bioprosthesis with good hemodynamics and absence of MR. Cardiac computed tomography showed a well-anchored prosthesis with normal leaflet appearance (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

30-Day Follow-Up Cardiac Computed Tomography Imaging

(A) Three-chamber view demonstrates a well-positioned prothesis. (B) Short-axis view demonstrates circular expansion of the inner frame of the prosthetic valve.

Conclusions

The development of TMVR devices has focused on patients with symptomatic MR. Our experience demonstrates that transseptal TMVR may become a viable option for patients with rheumatic MS who are not candidates for PBMV or surgical mitral valve replacement.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Ranard has received institutional funding to Columbia University Medical Center from Boston Scientific; and has received consulting fees from 4C Medical and Philips. Dr Vahl has received institutional funding to Columbia University Irving Medical Center from Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, JenaValve, and Medtronic; and has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular, JenaValve and 4C Medical. Dr Granada is a coinventor and cofounder of Cephea Valve Technologies (Abbott Vascular). Dr Chehab has received study grants and consulting fees from Abbott, Edwards Lifesciences, and Biotronics. Dr Grizzell has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Reyes V.P., Raju B.S., Wynne J., et al. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty compared with open surgical commissurotomy for mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:961–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410133311501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palacios I.F., Sanchez P.L., Harrell L.C., Weyman A.E., Block P.C. Which patients benefit from percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty? Prevalvuloplasty and postvalvuloplasty variables that predict long-term outcome. Circulation. 2002;105:1465–1471. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012143.27196.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrero M., Urena M., Himbert D., et al. 1-year outcomes of transcatheter mitral valve replacement in patients with severe mitral annular calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1841–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alperi A., Granada J.F., Bernier M., Dagenais F., Rodés-Cabau J. Current status and future prospects of transcatheter mitral valve replacement: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:3058–3078. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modine T., Vahl T.P., Khalique O.K., et al. First-in-human implant of the cephea transseptal mitral valve replacement system. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alperi A., Dagenais F., Del Val D., et al. Early experience with a novel transfemoral mitral valve implantation system in complex degenerative mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;13:2427–2437. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]