Abstract

Background:

Researchers over the last three decades have documented processes of gender and racial/ethnic inequality in engineering education, but little is known about other axes of difference, including the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) persons in engineering. Despite growing interest in LGBTQ inequality generally, prior research has yet to systematically document day-to-day experiences of inequality in engineering along LGBTQ status.

Purpose/Hypothesis:

In this paper, we utilize survey data of students from eight schools to sketch the landscape of LGBTQ inequality in engineering education. Specifically, we ask, do LGBTQ students experience greater marginalization than their classmates, is their engineering work more likely to be devalued, and do they experience more negative health and wellness outcomes? We hypothesize that LGBTQ students experience greater marginalization and devaluation and worse health and wellness outcomes compared to their non-LGBTQ peers.

Data/Method:

We analyze novel survey data from 1729 undergraduate students (141 of whom identify as LGBTQ) enrolled in eight U.S. engineering programs.

Results:

We find that LGBTQ students face greater marginalization, devaluation, and health and wellness issues relative to their peers, and that these health and wellness inequalities are explained in part by LGBTQ students’ experiences of marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs. Further, there is little variation in the climate for LGBTQ students across the eight schools, suggesting that anti-LGBTQ bias may be widespread in engineering education.

Conclusions:

We call for reflexive research on LGBTQ inequality engineering education and the institutional and cultural shifts therein needed to mitigate these processes and better support LGBTQ students.

Keywords: Sexual Orientation, Transgender, Bias, Inclusion, Engineering Culture

INTRODUCTION

A growing and interdisciplinary group of scholars have raised alarm about the persistent patterns of bias and discrimination within engineering education. Despite the energy and resources put toward advancing diversity in engineering, and engineering education’s formal commitment to equality and inclusion, women and many racial/ethnic minority groups continue to be underrepresented in engineering education and frequently encounter disadvantageous treatment therein (Blair et al., 2017; Brown, Morning & Watkins, 2005; Cech et al., 2011; Floor et al., 2007; Leslie, McClure & Oaxaca, 1998; National Science Foundation, 2009; Ohland et al., 2011). Research shows that these demographic patterns are the result of both structural processes and cultural practices within engineering education that systematically disadvantage women and students of color (Blair et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2005; Floor et al., 2007; Ohland et al., 2011; Cech, 2013; Samuelson & Litzler, 2015).

Aside from these important advancements in understanding the foundations of gender and racial/ethnic inequality, far less attention has been paid to the ways disadvantage may play out in engineering along other demographic categories, particularly those that are not always immediately visible or recognizable (Cech & Rothwell, 2018). One potentially ubiquitous but under-researched axis of disadvantage is the possible stigmatization and discrimination encountered by persons who identify as non-heterosexual or whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. Despite recent cultural and legal advancements toward greater inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) persons (Sears & Mallory, 2011), bias and discrimination toward LGBTQ individuals is pervasive in the US broadly (Doan et al., 2014; Herek, 2007; Ragins, 2008) and in academic institutions specifically (Bilimoria & Stewart, 2009; Patridge et al., 2014). LGBTQ persons lack even basic formal employment protections in over half of U.S. states (HRC, 2017) and LGBTQ workers experience systematic biases in the science and engineering workforce and beyond (Cech & Pham, 2017; Hebl et al., 2002; Tilcsik 2011). Although recent attention has been paid to the numeric under-representation of LGB individuals in STEM fields (Hughes, 2018), less is understood about the everyday experiences of bias that sexual minority, transgender, and gender non-binary students face prior to entering the workforce. Focusing on the experiences of LGBTQ students in engineering education allows us to better understand how processes of bias are perpetuated beyond typically visible markers of difference such as gender and race/ethnicity, analyzing not only whether such inequalities exist but what types of everyday experiences in engineering education may be impacted by anti-LGBTQ bias. The present study asks: How do LGBTQ persons fare in U.S. engineering education? What types of disadvantages, if any, do LGBTQ students encounter in their day-to-day experiences in their engineering programs, compared to their non-LGBTQ classmates?

Initial research, reviewed below, suggests that anti-LGBTQ bias flourishes in engineering education and may be fostered not only by the prejudicial behaviors and attitudes of individual students and faculty, but also by assumptions and practices embedded within the professional culture of engineering itself (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Hughes, 2017; Riley, 2008; Yoder and Mattheis 2016). This pioneering research suggests that LGBTQ identity may be a powerful differentiator of student experience within engineering education, and that LGBTQ-identifying students may face negative experiences that are not shared by their classmates. However, due to data and access limitations related to the size of the LGBTQ population and its absence in institutional record-keeping, research to date has not yet been able to systematically investigate possible disadvantages in the day-to-day experiences of engineering students across LGBTQ status. Such investigation is vital to advance scholarly knowledge about inequality in engineering and to promote policy changes that could improve the experiences of LGBTQ students. Absent a direct non-LGBTQ comparison group, skeptics of prior research on LGBTQ student experiences may argue that is there is nothing “special” or disadvantageous about LGBTQ students’ experiences in engineering education and any experiences of marginalization documented in research on LGBTQ-only samples is simply characteristic of the engineering education experience itself.

Using novel survey data of over 1,700 students across eight U.S. engineering education programs, this research compares the day-to-day experiences of LGBTQ-identifying students with their non-LGBTQ classmates in the same engineering programs. Such a comparison provides an unprecedented opportunity to examine whether LGBTQ students are indeed systematically disadvantaged in engineering and to explore the various ways such inequality may manifest.

We attend to three specific areas of potential disadvantage: informal interactional experiences, (de)valuation, and personal health and wellbeing. Specifically, this study asks: do LGBTQ students experience greater marginalization from classmates and peers than other students? Are LGBTQ students more likely than their non-LGBTQ classmates to report that their engineering work is devalued? Do LGBTQ students experience worse health and wellbeing outcomes than their classmates? Are these more negative health and wellness outcomes partly the result of LGBTQ students’ experiences of marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs? The analyses that follow indicate that LGBTQ students do indeed experience systematic marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs and these experiences, in turn, foster more negative health and wellness outcomes for LGBTQ students. We also find little systematic variation in these disadvantages by school, suggesting that these biases may be a feature of the culture of engineering education more broadly, rather than just an artifact of one or two particularly biased school contexts.

Beyond documenting these patterns of disadvantage for LGBTQ engineering students, this study advances theory on inequality in engineering by highlighting how heteronormativity, homophobia, and transphobia, in addition to the sexism and racism documented by prior research, may be embedded within the culture of engineering education that spans the array of engineering programs and colleges in the U.S. This investigation also illustrates how everyday marginalization and devaluation not only impacts students’ social and academic experiences, but also affects students in deeply personal, health-related ways. Finally, because engineering education is a place where neophyte engineers learn the cultural norms and dominant professional identities of engineering (Cech, 2015; Dryburgh, 1999), LGBTQ disadvantages, to the extent that they are built into the cultural norms and practices of engineering training, may accompany engineering graduates into the workforce and perpetuate anti-LGBTQ biases there as well.

BACKGROUND

Inequality in Engineering Education

Researchers have argued that differential persistence in engineering education by demographic category, especially along racial/ethnic and gender lines, are largely the outcome of underrepresented groups’ disadvantageous experiences within their engineering education programs (Brown et al., 2005; Floor et al., 2007). These disadvantages include unequal educational opportunities, uneven mentoring, and status biases and stereotypes perpetuated by classmates and professors (Turner, 2002; Moody, 2004; Cech et al., 2011; Cheryan et al., 2011; Archer et al., 2013). Non-dominant groups in engineering education are often less likely to feel as though they belong in engineering fields compared to their white male counterparts (Dryburgh, 1999; Floor et al., 2007; Zambrana et al., 2015).

These disparities are not just the result of encounters with a select few overtly prejudiced students or faculty. Biases are frequently built into the informal, interactional practices of engineering programs. Members of under-represented groups commonly report experiencing a “chilly climate” within their engineering programs, where subtle biases are part of the taken-for-granted assumptions and habits of members of their department—impacting which students are considered the smartest and most capable and who is included in study and lab groups, extracurricular gatherings, and student clubs (Tonso, 1996; Leslie et al., 1998).

Beyond individual and interactional processes within particular programs, disadvantageous practices and ideologies are built into the professional culture of engineering, which spans engineering education programs and U.S. engineering workforce broadly (Cech 2014). Professional cultures are historically-rooted meaning systems built into and around the characteristic tasks and knowledge of a profession (Abbott, 1988). Biases built into professional cultures may serve as particularly insidious mechanisms of disadvantage, as these cultural processes are typically less overt and thus often go unnoticed and unaddressed (Cech, 2013).

A particularly relevant aspect of engineering culture for our investigation is the cultural emphasis on disengagement—the devaluation of public welfare, social justice, and inequality related concerns as tangential to “real” engineering work. Disengagement frames the way neophytes learn to define the scope of their professional responsibilities and how to accomplish the day-to-day tasks of engineering (Cech, 2014). Three ideological tenants underlie this cultural emphasis on disengagement: depoliticization, or the assumption that “objective” engineering work can and should be separate from issues deemed political or social (Wynne, 1992; Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Cech & Sherick, 2015; Faulkner, 2007); the technical/social dualism, or the privileging of technical skill and competence and the devaluation of social considerations like inequality (Faulkner, 2007); and the meritocratic ideology, or the belief that professional success is due to hard work alone and those who fail are solely responsible for their own outcomes (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Cech, 2013; McCall, 2013). Because this cultural feature of engineering frames concerns about socio-demographic inequality as irrelevant to the core concerns of the engineering profession, it can aggravate feelings of isolation and devaluation and diminish the sense of belonging for disadvantaged group members within engineering education (Cech, 2014; Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Floor et al., 2007).

Although research has documented how processes at the interactional, departmental, and professional cultural levels foster negative experiences for women and racial/ethnic minorities within engineering education, much less is known about the experiences of LGBTQ students in engineering. Researchers understand little about how LGBTQ students’ experiences within their engineering education programs differ from those of their non-LGBTQ-identifying peers and the effects that these experiences have on students’ general well-being. Some recent scholarship has begun to unpack the experiences of LGBTQ students in engineering. We next review this literature and then set up the specific hypotheses we investigate with our data.

Engineering Education and Anti-LGBTQ Bias

The devaluation of sexual minorities and transgender and gender non-binary persons can occur through processes that operate at multiple levels. Heterosexism is anti-LGBTQ bias that operates at the macro level and includes policies, practices, and cultural ideologies that privilege heterosexuality and cisgender status and promote social biases against sexual minorities and non-cisgender persons (Kitzinger, 2005). Institutional-level heterosexism might include university policies that exclude same-gender partners from healthcare benefits or electronic records systems that prevent students from changing their preferred gender pronouns. Heteronormativity encompasses more subtle interpersonal and institutional beliefs, such as the assumption that heterosexuality is the most acceptable sexual orientation and that there are two mutually exclusive, biologically determined sexes (Herek, 2004). At the micro level, heteronormativity and heterosexism take the form of sexual prejudice and transphobia, or prejudicial attitudes and behaviors that individuals exhibit on the basis of others’ actual or presumed sexual orientation and/or gender expression (Herek, 2004). Transphobia (anti-transgender and gender-nonconformity bias) is tightly linked to bias against non-heterosexual persons, as transphobia rests on the belief that there are two natural and complimentary sexes and that heterosexuality is a natural feature of biological sex categories (Schilt & Westbrook, 2009; Westbrook & Schilt, 2014). The devaluation of LGBTQ persons may be especially heightened in engineering contexts. In a sample of LGBTQA-identifying individuals in STEM, for example, Yoder and Mattheis (2016) found that LGBTQA individuals in engineering report lower degree of openness about their LGBTQ status to their colleagues and students than those in other STEM fields.

Early research suggests that heteronormativity, heterosexism, sexual prejudice, and transphobia may be pervasive in engineering and engineering education (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Cech and Pham, 2017; Hughes, 2017; Yoder and Mattheis 2016). Sexual minorities have lower persistence in STEM fields like engineering than heterosexual students (Hughes, 2018). Existing research also suggests that LGBTQ engineering students face both overt forms of heteronormativity, transphobia, and sexual prejudice, including blatant anti-LGBTQ sentiments, and also more covert forms of bias, such as the presumption that all engineering students are heterosexual and cisgender and the silencing of sexual minority and transgender student concerns. This pervasive heteronormativity within engineering education programs appears to foster an educational culture where LGBTQ persons may have more trouble developing an “engineering identity” (Hughes, 2017) and feel as though they must work harder to compensate for their sexual identity to be seen as competent engineering students (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011).

LGBTQ students in engineering may adopt tactics of passing, covering, and compartmentalization in order to navigate engineering spaces where they feel their LGBTQ status is devalued or stigmatized (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Yoder and Mattheis 2016). Passing is a tactic where individuals hide their stigmatized identities, such as sexual minorities who work to be seen as straight by others (Yoshino, 2006). Going “stealth” is a form of passing preferred by some transgender individuals who take pride in a successful gender transition and do not openly identify as transgender (Schilt, 2010). Covering is similar to passing, but refers to a practice where individuals may be open about their LGBTQ status to most people but minimize the salience of the traits associated with their stigmatized identity (Goffman, 1963; Yoshino, 2006). For example, LGBTQ students who use the tactic of covering might conceal markers of their LGBTQ identity such as avoiding talk regarding romantic or sexual relationships, leisure activity preferences, or gender expression practices. Related, compartmentalization is a tactic where LGBTQ individuals maintain strict separation of their personal lives (where they may be open about their LGBTQ status) from their “professional” lives at school. Although these tactics may help LGBTQ students circumvent stigma and discrimination within their educational programs, they burden LGBTQ students with additional emotional and academic labor their non-LGBTQ peers do not face and may amplify feelings of social and academic isolation (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011).

The Present Study

Although previous research suggests that LGBTQ engineering students face marginalization that their classmates may not, due to data limitations, research to date has not been able to isolate how these processes vary across LGBTQ status. The present study is able to examine the experiences of LGBTQ students in engineering education programs controlling for other demographic characteristics like race/ethnicity and socio-economic status that may also affect experiences of marginalization and devaluation. Further, we do not yet know how extensively these disadvantageous experiences within engineering education programs might impact students. This study thus examines how processes of marginalization and devaluation translate into deeply personal consequences, such as stress, insomnia, and emotional health issues.

Drawing on the literature reviewed above, we offer several hypotheses. First, based on research suggesting that LGBTQ engineering students feel excluded by their peers, we expect that LGBTQ respondents in our sample will be more likely than their non-LGBTQ peers to experience marginalization—to feel isolated from other students and less likely to feel secure participating in informal interactions with classmates. Second, beyond social exclusion, we expect that LGBTQ students will be less likely to report that their engineering abilities are respected by their peers and teachers or to feel comfortable working in teams with other students, net of controls.

Third, we anticipate that students may be affected personally and deeply by heteronormativity, heterosexism, and transphobia in their engineering education programs—with negative outcomes for their health and wellness. Specifically, compared to their peers, LGBTQ students may more frequently experience exhaustion, stress, pre-depressive symptoms, and sleeping problems, net of controls. This is consistent with research that has found that health and wellness for LGBTQ individuals is frequently impacted by the cultural and structural circumstances in which they are embedded (Solazzo, Brown & Gorman, 2018).

However, these analyses would only indicate whether LGBTQ students report more negative health and wellness outcomes than their peers; they do not tell us if such differentials are driven by LGBTQ students’ more negative experiences in their engineering program or by unrelated personal experiences outside of school. In order to examine this directly, we conduct mediation analyses to determine whether LGBTQ students’ experiences of marginalization and devaluation in their departments help explain why they are more likely to report more negative health and wellness outcomes. Significant mediation effects would indicate that LGBTQ students’ experiences with marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs “get under their skin” to impact them in a way that runs deeper than just their social experiences and coursework.

Finally, we are interested in whether LGBTQ bias is isolated to just a few engineering programs, or whether this bias seems to be widespread across the culture of engineering education broadly. Based on the literature above, which suggests that anti-LGBTQ bias may be part of the culture of engineering education generally (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Hughes, 2017), we suspect that students will rate the climate of their engineering programs for LGBTQ students similarly across the schools in the sample. Significant school effects would indicate that the climate for LGBTQ students in engineering education is quite variable school to school, and the differences found on the first three hypotheses may be driven by the results from a handful of particularly heterosexist and/or transphobic engineering programs. Few differences across schools, on the other hand, may suggest that LGBTQ bias is not isolated to only certain schools, but is part of the culture of engineering education generally.

METHODS

The ASEE Diversity and Inclusion Survey was fielded in spring 2016 to undergraduate engineering students enrolled in eight engineering programs in the U.S. We identified these programs through an initial survey of U.S. engineering deans and program directors in fall 2015 (for details, see Cech et al., 2016). Ninety deans and program directors participated in this survey and 23 agreed to be contacted to discuss the possibility of surveying the engineering students and faculty in their programs. Eight deans agreed to send survey links out to undergraduate students in their engineering programs. Given this selection process, we expect that the engineering programs in our sample are more supportive on average of diversity and inclusion issues than schools in the U.S. generally, given that the engineering deans or program directors expressed at least nominal concern for diversity and inclusion issues in agreeing to include their engineering programs in the study in the first place. As such, the patterns of disadvantage we identify here are likely conservative estimates of broader patterns; engineering programs in the U.S. likely have similar if not more extreme patterns of disadvantage on average than those reported here.

The survey asked students a broad range of questions about their experiences in their engineering classrooms, their perceptions of the engineering profession, and their more general experiences as college students. The invitation email mentioned LGBTQ status only briefly alongside other axes of disadvantage: “This study will help engineering educators, scholars, university administrators, and national policymakers attempting to foster inclusion in engineering education programs for women, racial/ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer) students.”

We do not name the schools involved in the study to protect confidentiality, but Table A provides a general description of the types of institutions included in the study. The sample size for each school ranged from 82 students (school 101) to 909 students (school 109) and response rates ranged from a low of 4% to a high of 45% with an average of 17% across the eight schools (see Table A). This is consistent with student survey research, which typically have response rates between 15-30% (NSSE 2016).

Table A:

Means and Standard Deviations for Independent and Dependent Measures, for All Students and Separately by LGBTQ Status (N=1,729)

| ALL | LGBTQ | Non-LGBTQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | p | |

| LGBTQ (yes=1, no=0) | .087 | .007 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Hispanic (yes=1, no=0) | .037 | .005 | .079 | .023 | .034 | .005 | |

| Asian (yes=1, no=0) | .120 | .008 | .122 | .028 | .120 | .009 | |

| Black (yes=1, no=0) | .034 | .005 | .014 | .010 | .036 | .005 | |

| White (yes=1, no=0) | .835 | .009 | .878 | .028 | .831 | .010 | |

| Native Amer/ Pacific Islander (yes=1, no=0) | .017 | .003 | .017 | .012 | .017 | .003 | |

| Other Racial/Ethnic group (yes=1, no=0) | .018 | .003 | .014 | .010 | .018 | .004 | |

| Woman (yes=1, no=0) | .350 | .012 | .528 | .043 | .333 | .012 | |

| SES (1=working class to 5=upper class) | 2.564 | .032 | 2.698 | .109 | 2.554 | .033 | |

| First Generation Student (yes=1, no=0) | .144 | .009 | .189 | .033 | .140 | .009 | |

| Marginalization | |||||||

| Accepted by students in Dept (1=not accepted at all to 5=very accepted) | 3.544 | .017 | 3.335 | .064 | 3.563 | .017 | *** |

| Avoided Social Event (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 2.036 | .026 | 2.524 | .104 | 1.991 | .027 | *** |

| Included in Social Gatherings (1=strongly disagree [SD] to 5=strongly agree [SA]) | 3.434 | .024 | 3.092 | .098 | 3.463 | .025 | *** |

| Hide Personal Life (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 1.777 | .026 | 2.511 | .111 | 1.706 | .026 | *** |

| Offensive Comments (1=SD to 5=SA) | 2.567 | .034 | 3.137 | .127 | 2.516 | .035 | *** |

| Devaluation | |||||||

| Treated as Equally Skilled Student (1=SD to 5=SA) | 3.997 | .020 | 3.762 | .076 | 4.017 | .021 | *** |

| Students Respect Engr Work (1=SD to 5=SA) | 4.056 | .019 | 3.842 | .079 | 4.076 | .019 | *** |

| Avoided Team or Project (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 1.967 | .029 | 2.510 | .106 | 1.918 | .030 | *** |

| Health and Wellness | |||||||

| Exhausted from Compartmentalization (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 2.149 | .032 | 2.547 | .116 | 2.115 | .034 | *** |

| Nervous (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 3.773 | .026 | 4.115 | .078 | 3.743 | .028 | *** |

| Depressed or Sad at School (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 2.444 | .032 | 3.072 | .113 | 2.386 | .033 | *** |

| Sleeping Troubles (1=never to 5=almost every day) | 2.552 | .030 | 2.871 | .107 | 2.524 | .031 | ** |

| LGBTQ Students face Veiled Hostility (1=SD to 5=SA) | 2.193 | .023 | 2.439 | .087 | 2.170 | .023 | ** |

| Colleagues Condescending to LGBTQ Students (1=SD to 5=SA) | 2.744 | .028 | 3.053 | .101 | 2.716 | .029 | ** |

| Witnessed mistreatment of LGBTQ student (1=yes, 0=no) | .092 | .008 | .359 | .043 | .067 | .007 | *** |

| Schools | |||||||

| School 101: Small, private school in the NE (N=82, Response Rate [RR]=18%) | .029 | .004 | .022 | .012 | .030 | .004 | |

| School 108: Large, public flagship in the NE (N=233, RR=7%) | .091 | .007 | .086 | .024 | .092 | .008 | |

| School 109: Small Tech school in the Midwest (N=909, RR=45%) |

.359 | .012 | .439 | .042 | .350 | .013 | * |

| School 110: Large public in the NE (N=128, RR=4%) |

.044 | .005 | .072 | .022 | .042 | .005 | |

| School 114: Small Catholic school in the West (N=215, RR=30%) |

.101 | .008 | .129 | .029 | .098 | .008 | |

| School 116: Large public school in the South (N=290, RR=7%) |

.092 | .007 | .079 | .023 | .094 | .008 | |

| School 117: Large public flagship in the South (N=620, RR=11%) |

.238 | .011 | .101 | .026 | .251 | .011 | ** |

| School 120: Mid-size public school in the NE (N=98, RR=8%) |

.046 | .005 | .072 | .022 | .043 | .005 | |

Note:

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test)

A total of 2,575 students began the survey; to improve data quality and reliability, we use only the 1,729 respondents who passed the attention filter question. Attention checks significantly improve the quality of the data by excluding respondents who are not reading the options carefully. For this survey, we included a check that was worded as follows: “As a consistency check, please choose “Almost every day” for this question.” Respondents who chose something other than “almost every day” for this response were coded as having failed the attention filter (Oppenheimer, Meyvis and Davidenko 2009). Supplemental analyses ran with this full sample of 2,575 students, and models sequentially excluding the schools with the lowest response rates, produced the same patterns of results as presented here. See the robustness checks section below for a review of these supplemental analyses.

Dependent and Independent Measures

Marginalization Measures

We include five measures of the extent to which respondents feel marginalized by their classmates: “How accepted do you feel by the following: students in your engineering/engineering technology classes” (1=not accepted at all to 5=very accepted); “when my classmates get together after class, for example to go to lunch, I am usually included in the invitation” (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree); “Thinking about the past 12 months, did any of the following happen to you?…Avoided a social event such as a lunch or a holiday party” (1=never to 5=almost every day); “Felt the need to lie about my personal life to other students” (1=never to 5=almost every day); and “Stayed home from school because you did not feel welcome” (1=never to 5=almost every day). Finally, we include a question about whether respondents have encountered offensive sentiments in their engineering environments: “Please indicate your level of agreement regarding the climate in your engineering college: “I have read, heard, and/or seen insensitive comments that I found offensive” (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

Devaluation Measures

Devaluation of students’ engineering work is measured through two questions about the respect students receive for their engineering work: “my peers respect me for the work that I do” (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) and “In this engineering college, my schoolwork is respected” (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). To assess students’ reactions to the social and intellectual devaluation they may encounter from peers in group work settings (see, e.g., Cech & Waidzunas, 2011), we also include a question about the extent to which students have avoided working with teams or projects in their schoolwork: “Thinking about the past 12 months, did any of the following happen to you? …Avoided working on a certain school project or team” (1=never to 5=almost every day).

Health and Wellness Measures

We use four measures of negative health and wellness outcomes: “Thinking about the past 12 months, did any of the following happen to you?” “Felt exhausted from spending time and energy keeping my personal and professional lives separate,” “had trouble sleeping to the point that it affected your performance in and out of school,” “felt nervous or stressed,” and “felt unhappy or depressed at school” (1=never to 5=almost every day). The latter two questions are often used in national studies as pre-depression and pre-anxiety indicators (e.g., the National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration).

Engineering Program Climate Questions

Finally, we include three measures that asked respondents to assess the climate in their engineering programs for LGBTQ-identifying students. The first two ask respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree with the following statements: “LGBTQ students are met with thinly veiled hostility (for example, scornful looks or icy tone of voice)” and “some faculty and students seem condescending toward colleagues who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer’” (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). Finally, students were asked, “Overall, in the last three years, have you ever been aware of instances in which students in your engineering/engineering technology classes may possibly have been treated negatively due to their:” “Sexual identity,” and “Gender expression or transgender status.” Students who indicated yes on either this sexual identity and/or gender expression question were coded as “yes” on the aggregated measure of whether they had observed unfair treatment toward LGBTQ students (1=yes, 0=no).

Independent Measures

LGBTQ status is measured by a set of indicators that asked separately about students’ sexual identity and gender expression. First, respondents were asked, “Please mark your sexual identity from the categories below” and could choose between the following options: “Heterosexual or straight,” “Gay or Lesbian,” “Bisexual,” “Queer,” “Don’t Know” or “Something Else.” Those who marked “something else” were invited to specify with a text box. Anyone who marked “Gay or Lesbian,” “Bisexual,” or “Queer” on this question were included in our LGBTQ category. Because respondents who marked “don’t know” or “something else” did not choose to identify with one of the categories in the LGBTQ acronym, we did not include them in the LGBTQ category.

Gender expression was measured with a set of three questions. The first question asked “what sex were you assigned at birth?” “Male” or “Female.” The second question asked “How do you currently describe yourself?” “Male,” “Female,” “Transgender Male” or “Transgender Female,” “Something else,” or “I don’t know.” Respondents whose answer on the second question was different from their answer on the first question were asked the following follow-up question: “Just to confirm, you were assigned a different sex at birth than how you currently describe yourself. Is that correct?” “yes” or “no.” This confirmation question limits the number of false positives for transgender or gender non-binary identity—an important step for appropriately capturing proportionally small populations like non-cisgender individuals. Those who answered yes to this confirmation question were included in the LGBTQ category. Respondents who marked “something else” or “I don’t know” in the current gender identity question were coded as “gender non-binary” for their current gender category. Due to the very small proportion of respondents in this gender non-binary category, and the need to protect the confidentiality of respondents, we do not provide data as a separate category for gender non-binary respondents. Instead, the indicator for “women” is contrasted against both the categories for men and gender non-binary students in our models.

Students who indicated that their current gender identity is female (whether they are cis-gender or transgender) were included in the category “women;” men who indicated their current gender identity as male (whether they are cis- or transgender) were included in the category “men.”

We also include several measures of other important demographic characteristics that may impact students’ likelihood of experiencing marginalization and devaluation. We control for their racial/ethnic category (respondents could choose more than one): Hispanic, black, Asian, Native American/Pacific Islander, white, and other racial/ethnic category (1=yes, 0=no). Next, we control for respondents’ self-report of the socio-economic status (SES) of their family of origin: “what would you say is the economic class of your family growing up:” “working class”=1, “lower-middle class” =2, “middle class”=3, “upper-middle class”=4, “upper class”=5. We also control for whether the respondent is a first-generation college student. Specifically, students were asked, “Are you the first person in your immediate family (parents/guardians, siblings) to attend college?” (1=yes, 0=no). Finally, each model includes controls for school, with school 114 serving as the comparison category. Including these measures in our models allow us to identify the effect of LGBTQ status on marginalization, devaluation, and health and wellness measures holding constant possible variation by race/ethnicity, SES, first generation status, and school.

Analytic Strategy

The analyses below use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, ordered logistic regression, or logistic regression models, as appropriate, to predict each outcome variable of interest. Table A below provides the means and standard errors for all respondents and for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ students separately. Table B predicts the marginalization variables one at a time with LGBTQ identity and controls. Next, we predict the devaluation measures (Table C) and health and wellness measures (Table D). To test for mediation effects of marginalization and devaluation on the health and wellness measures, we utilize structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM is a useful empirical tool that allows us to test for indirect (mediating) effects—whether part of the statistical relationship between two factors (here, LGBTQ status and the health and wellness measures) can be explained by variation on a third factor (here, the marginalization or devaluation measures) (see Byrne, 2010). Table E presents the direct effects of LGBTQ status on health and wellness measures and the indirect effects of LGBTQ status on each health and wellness measure through each of the marginalization and devaluation measures.

Table B:

OLS Regression Models Predicting Marginalization Measures, with LGBTQ Status and Controls (N=1,792)

| Feel Accepted by Other Students | Avoided a Social Event with Classmates | Feel included in Invitations to Social Gatherings | Felt the Need to Hide Personal Life | Stayed Home from School b/c Didn’t Feel Welcome | Seen or Heard Offensive Comments in Engineering Spaces | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |||||||

| LGBTQ | −.214 | *** | .057 | .503 | *** | .095 | −.330 | *** | .094 | .813 | *** | .093 | .318 | *** | .052 | .441 | *** | .117 |

| Hispanic | −.080 | .093 | .050 | .145 | −.078 | .141 | −.017 | .140 | .093 | .076 | .091 | .174 | ||||||

| Asian | −.154 | ** | .059 | .219 | * | .088 | −.042 | .083 | .144 | .081 | .177 | *** | .049 | .056 | .105 | |||

| Black | −.220 | * | .091 | .149 | .154 | −.052 | .144 | −.095 | .149 | .095 | .082 | .131 | .191 | |||||

| Native American/Pacific Isl. | −.035 | .137 | .184 | .206 | −.002 | .210 | .408 | * | .202 | .066 | .119 | .417 | .257 | |||||

| Other Racial/Ethnic Group | −.277 | .143 | .051 | .199 | −.242 | .195 | .067 | .188 | .145 | .122 | .182 | .257 | ||||||

| Woman | −.124 | *** | .034 | .226 | *** | .056 | −.081 | .055 | .131 | * | .052 | .077 | * | .030 | .627 | *** | .069 | |

| SES | .010 | .013 | .002 | .021 | −.016 | .021 | .005 | .020 | −.003 | .011 | .037 | .025 | ||||||

| FirstGen Student | −.010 | .049 | .010 | .076 | −.020 | .076 | −.060 | .072 | .060 | .041 | .008 | .093 | ||||||

| School 101 | −.055 | .099 | .073 | .160 | .176 | .165 | .019 | .155 | .078 | .089 | .066 | .201 | ||||||

| School 108 | .020 | .077 | −.110 | .114 | −.035 | .119 | −.077 | .112 | −.036 | .064 | .046 | .145 | ||||||

| School 109 | −.038 | .064 | −.120 | .088 | .020 | .093 | .033 | .086 | .058 | .050 | .247 | * | .112 | |||||

| School 110 | −.155 | .090 | .053 | .143 | −.070 | .148 | .214 | .139 | .013 | .079 | .122 | .179 | ||||||

| School 116 | .043 | .089 | −.278 | * | .111 | −.072 | .117 | −.133 | .108 | −.004 | .063 | −.204 | .140 | |||||

| School 117 | .018 | .065 | −.121 | .093 | −.054 | .099 | −.082 | .091 | .088 | .053 | .008 | .119 | ||||||

| School 120 | .032 | .084 | −.273 | * | .138 | .003 | .145 | −.090 | .136 | .012 | .078 | .057 | .170 | |||||

| Constant | 3.617 | *** | .067 | 1.990 | *** | .098 | 3.574 | *** | .103 | 1.659 | *** | .097 | 1.060 | *** | .056 | 2.105 | *** | .121 |

Note:

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test); School 114 is the comparison category for institution; white is the comparison category for race/ethnicity; men and gender non-binary are the combined comparison category for women.

Table C:

OLS Regression Models Predicting Devaluation Measures, with LGBTQ Status and Controls

| Classmates Treat Me with Respect | My Work is Respected | Avoided Working with a Certain Team or on a Certain Project | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff. | SE | ||||

| LGBTQ | −.195 | ** | .073 | −.212 | ** | .068 | .575 | *** | .100 |

| Hispanic | −.065 | .106 | −.013 | .104 | −.007 | .150 | |||

| Asian | −.112 | .062 | −.139 | * | .058 | −.004 | .093 | ||

| Black | −.031 | .114 | −.115 | .107 | −.171 | .155 | |||

| Native American/Pacific Isl. | −.097 | .158 | −.153 | .151 | .451 | * | .223 | ||

| Other Racial/Ethnic Group | −.326 | .167 | −.021 | .161 | .063 | .206 | |||

| Woman | −.255 | *** | .042 | −.153 | *** | .040 | .274 | *** | .060 |

| SES | .001 | .016 | .018 | .015 | −.018 | .023 | |||

| First Generation Student | −.082 | .058 | −.016 | .054 | −.016 | .080 | |||

| School 101 | −.155 | .123 | −.237 | * | .116 | .045 | .175 | ||

| School 108 | −.018 | .088 | −.077 | .082 | −.046 | .125 | |||

| School 109 | .050 | .068 | −.008 | .063 | .056 | .097 | |||

| School 110 | −.063 | .111 | −.037 | .103 | −.180 | .157 | |||

| School 116 | .057 | .087 | .004 | .080 | −.203 | .122 | |||

| School 117 | .032 | .072 | .001 | .067 | −.050 | .103 | |||

| School 120 | −.030 | .107 | .023 | .102 | .052 | .159 | |||

| Constant | 4.110 | *** | .074 | 4.114 | *** | .070 | 1.889 | *** | .110 |

Note:

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test) School 114 is the comparison category for institution; white is the comparison category for race/ethnicity; men and gender non-binary are the combined comparison category for women.

Table D:

OLS Regression Models Predicting Personal Health and Wellness Outcomes, with LGBTQ Status and Controls

| Felt Exhausted from Spending Energy Keeping Personal & Professional Life Separate | Felt Nervous or Stressed | Felt Unhappy or Depressed at School | Had Trouble Sleeping to the Point that it Affected Your Performance In/Out of School | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |||||

| LGBTQ | .436 | *** | .117 | .256 | *** | .089 | .638 | *** | .112 | .291 | ** | .105 |

| Hispanic | −.115 | .173 | .008 | .135 | −.104 | .164 | −.017 | .164 | ||||

| Asian | .255 | * | .105 | −.296 | *** | .079 | .007 | .099 | .013 | .093 | ||

| Black | .226 | .183 | −.548 | *** | .139 | −.121 | .171 | .084 | .163 | |||

| Native American/Pacific Isl. | .292 | .253 | .188 | .194 | .282 | .251 | .481 | * | .228 | |||

| Other Racial/Ethnic Group | .070 | .231 | −.178 | .185 | .174 | .234 | .362 | .223 | ||||

| Woman | .154 | * | .068 | .539 | *** | .053 | .254 | *** | .065 | .327 | *** | .062 |

| SES | .013 | .026 | .018 | .020 | .013 | .025 | −.006 | .024 | ||||

| First Generation Student | .024 | .090 | .074 | .073 | −.021 | .087 | .246 | *** | .083 | |||

| School 101 | −.027 | .197 | .068 | .154 | .105 | .191 | .089 | .183 | ||||

| School 108 | .016 | .142 | .007 | .110 | .011 | .137 | .136 | .131 | ||||

| School 109 | .016 | .110 | .105 | .085 | .174 | .107 | .208 | * | .101 | |||

| School 110 | .339 | .174 | .160 | .135 | .259 | .169 | .137 | .162 | ||||

| School 116 | .121 | .137 | −.059 | .107 | −.019 | .133 | .086 | .127 | ||||

| School 117 | .121 | .117 | .187 | * | .091 | .146 | .113 | .187 | .108 | |||

| School 120 | −.189 | .177 | .008 | .132 | −.042 | .175 | .012 | .161 | ||||

| Constant | 1.924 | *** | .128 | 3.470 | *** | .095 | 2.164 | *** | .121 | 2.233 | *** | .112 |

Note:

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test); School 114 is the comparison category for institution; white is the comparison category for race/ethnicity; men and gender non-binary are the combined comparison category for women.

Table E:

Coefficient Estimates and Standard Errors from Structural Equation Models for Direct and Indirect Effects of LGBTQ Status, Marginalization, and Devaluation on Health and Wellness Outcomes

| Direct Effect of LGBTQ→ Health/ Wellness Measure | Indirect Effect of LGBTQ Status via Marginalization Measure | Indirect Effect of LGBTQ Status via Devaluation Measure | CFI (C) & RMSEA (R) Fit Statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff. | SE | |||||

| Outcome: Felt Exhausted from Spending Energy Keeping Personal & Professional Life Separate | ||||||||||

| Mediators: Marginalization | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Feel accepted | .384 | ** | .056 | .074 | ** | .023 | --- | C=.791 R=.044 | ||

| Mediator: Avoided social event | .270 | * | .109 | .196 | *** | .036 | --- | C=.891 R=.031 | ||

| Mediator: Included in social gatherings | .407 | *** | .113 | .042 | ** | .015 | --- | C=1.00 R=.000 | ||

| Mediator: Hide personal life | .028 | .106 | .447 | *** | .051 | --- | C=.961 R=.023 | |||

| Mediator: Stayed home, not welcome | .306 | ** | .111 | .156 | *** | .029 | --- | C=.869 R=.029 | ||

| Mediator: Offensive comments | .409 | *** | .113 | .063 | ** | .019 | --- | C=.878 R=.055 | ||

| Mediators: Devaluation | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Classmates treat with respect | .342 | ** | .113 | --- | .131 | *** | .028 | C=.735 R=.035 | ||

| Mediator: Work is respected | .403 | *** | .112 | --- | .055 | ** | .018 | C=.848 R=.021 | ||

| Mediator: Avoid working on projects | .226 | * | .109 | --- | .206 | *** | .036 | C=.792 R=.041 | ||

| Outcome: Felt Nervous or Stressed | ||||||||||

| Mediators: Marginalization | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Feel accepted | .206 | * | .044 | .072 | *** | .020 | --- | C=.917 R=.047 | ||

| Mediator: Avoided social event | .147 | .086 | .133 | *** | .025 | --- | C=.924 R=.030 | |||

| Mediator: Included in social gatherings | .245 | ** | .088 | .024 | * | .010 | --- | C=1.00 R=.000 | ||

| Mediator: Hide personal life | .036 | .087 | .245 | *** | .032 | --- | C=.964 R=.023 | |||

| Mediator: Stayed home, not welcome | .195 | * | .088 | .075 | *** | .018 | --- | C=.910 R=.029 | ||

| Mediator: Offensive comments | .211 | * | .087 | .075 | *** | .018 | --- | C=.718 R=.057 | ||

| Mediators: Devaluation | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Classmates treat with respect | .183 | * | .088 | --- | .101 | *** | .022 | C=.867 R=.035 | ||

| Mediator: Work is respected | .226 | * | .087 | --- | .047 | ** | .015 | C=.944 R=.021 | ||

| Mediator: Avoid working on projects | .154 | .087 | --- | .128 | *** | .024 | C=.927 R=.029 | |||

| Outcome: Felt Unhappy or Depressed at School | ||||||||||

| Mediators: Marginalization | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Feel accepted | .517 | ** | .051 | .158 | *** | .041 | --- | C=.908 R=.048 | ||

| Mediator: Avoided social event | .409 | *** | .101 | .275 | *** | .047 | --- | C=.942 R=.030 | ||

| Mediator: Included in social gatherings | .569 | *** | .108 | .090 | *** | .025 | --- | C=1.00 R=.000 | ||

| Mediator: Hide personal life | .172 | .099 | .511 | *** | .056 | --- | C=.974 R=.025 | |||

| Mediator: Stayed home, not welcome | .469 | *** | .107 | .198 | *** | .034 | --- | C=.911 R=.029 | ||

| Mediator: Offensive comments | .586 | *** | .109 | .097 | *** | .024 | --- | C=.588 R=.058 | ||

| Mediators: Devaluation | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Classmates treat with respect | .533 | *** | .110 | --- | .145 | *** | .029 | C=.855 R=.035 | ||

| Mediator: Work is respected | .559 | *** | .106 | --- | .112 | *** | .031 | C=.942 R=.021 | ||

| Mediator: Avoid working on projects | .441 | *** | .104 | --- | .245 | *** | .041 | C=.934 R=.029 | ||

| Outcome: Had Trouble Sleeping to the Point that it Affected your Performance in/out of School | ||||||||||

| Mediators: Marginalization | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Feel accepted | .218 | * | .103 | .103 | *** | .029 | --- | C=.851 R=.047 | ||

| Mediator: Avoided social event | .158 | .102 | .164 | *** | .031 | --- | C=.887 R=.030 | |||

| Mediator: Included in social gatherings | .252 | * | 104 | .057 | ** | .018 | --- | C=1.00 R=.000 | ||

| Mediator: Hide personal life | .028 | .102 | .298 | *** | .038 | --- | C=.952 R=.023 | |||

| Mediator: Stayed home, not welcome | .143 | .103 | .168 | *** | .030 | --- | C=.897 R=.029 | |||

| Mediator: Offensive comments | .250 | * | .118 | .081 | *** | .021 | --- | C=.608 R=.051 | ||

| Mediators: Devaluation | ||||||||||

| Mediator: Classmates treat with respect | .198 | .105 | --- | .131 | *** | .027 | C=.817 R=.035 | |||

| Mediator: Work is respected | .239 | * | .102 | --- | .078 | ** | .023 | C=.910 R=.022 | ||

| Mediator: Avoid working on projects | .149 | .102 | --- | .179 | *** | .032 | C=.905 R=.029 | |||

Note:

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test); Each row represents coefficients from a separate structural equation model. All models include standard controls for gender, race/ethnicity, first generation status, SES, and school.

Finally, to examine the extent to which the climate for LGBTQ persons varies by school, we ran OLS and logistic regression models to predict the climate measures by school and other demographic measures (Table F). As is recommended practice, we use multiple imputation to handle missing data; specifically, we used the MI chained technique in Stata 14 with 20 imputations for OLS and ordered logistic regression models, and maximum likelihood with robust standard errors for the SEM models (Allison, 2000).

Table F:

OLS and Logistic Regression Models Predicting School Climate Measures

| LGBTQ Students Face Veiled Hostilitya | Some Faculty and Students Seem Condescending Toward People who are LGBTQa | Have Witnessed Instances of Unfair Treatment Toward LGBTQ Studentsb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff. | SE | ||||

| LGBTQ | .313 | *** | .082 | .381 | *** | .100 | 2.132 | *** | .231 |

| Hispanic | −.034 | .120 | .162 | .146 | −.148 | .520 | |||

| Asian | .213 | *** | .072 | .163 | .085 | −.050 | .327 | ||

| Black | .176 | .125 | .191 | .153 | −.457 | .805 | |||

| Native American/Pacific Islander | .245 | .181 | .163 | .220 | −.884 | 1.089 | |||

| Other Racial/Ethnic Group | −.059 | .165 | −.077 | .208 | .508 | .707 | |||

| Woman | −.047 | .048 | −.071 | .057 | .648 | ** | .210 | ||

| SES | −.006 | .018 | .044 | * | .021 | .074 | .078 | ||

| First Generation Student | .129 | * | .064 | .027 | .079 | .236 | .273 | ||

| School 101 | −.076 | .146 | −.037 | .173 | .106 | .697 | |||

| School 108 | −.051 | .104 | −.052 | .121 | .155 | .544 | |||

| School 109 | .127 | .082 | .215 | * | .093 | .634 | .382 | ||

| School 110 | .163 | .133 | .166 | .151 | .502 | .569 | |||

| School 116 | .076 | .100 | .225 | .121 | .487 | .486 | |||

| School 117 | .173 | * | .086 | .282 | ** | .100 | .766 | * | .388 |

| School 120 | −.039 | .125 | .066 | .151 | .072 | .566 | |||

| Constant | 2.058 | *** | .092 | 2.416 | *** | .103 | −3.657 | *** | .442 |

Note:

OLS Regression Model;

Logistic regression model.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05 (two-tailed test); School 114 is the comparison category for institution; white is the comparison category for race/ethnicity; men and gender non-binary are the combined comparison category for women. The first two columns present OLS regression models; the third column presents the results of a logistic regression model.

RESULTS

Table A presents the means and standard errors of each independent and dependent variable for all respondents and separately by LGBTQ status. Approximately 8.7% (N=141) of the sample identifies as LGBTQ. This is higher than the population-level estimates of college-educated Americans who identify as LGBTQ (2.8%, Gates & Newport, 2012), but reflects trends where a larger proportion of young adults identifies as LGBTQ than in previous generations (Risman, 2018).

Among our sample, 24% identify as a member of a racial/ethnic minority group. Thirty-five percent of respondents identify as women, 64% as men, and around 1% as gender non-binary. We include gender non-binary respondents as part of the LGBTQ indicator; however, because of concerns about the identifiability of this small population, we do not include gender non-binary as a dichotomous indicator in the models, or provide the precise percent of the gender non-binary population in Table A. As such, the category “woman” (which includes those who identify as cis-gender and transgender women) is compared in the models to both the categories of men (which includes cis-gender and transgender men) and gender non-binary respondents.

Compared to national statistics on engineering students (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2015), our sample has proportionally greater representation of women (20% nationally, 35% here) and racial/ethnic minorities (13% nationally, 24% here). Fourteen percent of the sample are first-generation college students. There are no significant differences between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ students along these demographic axes, meaning that gender and racial/ethnic diversity is similar among both groups of students.

The remaining rows in Table A present the means and standard errors for the outcome variables of interest and the proportion of the sample enrolled in each school. Suggesting a broad pattern of disadvantage, LGBTQ students have significantly more negative values on all of the marginalization, devaluation, and personal health and wellness measures, and are more likely to report negative LGBTQ climates in their engineering programs. The analyses in the next subsection determine whether these differences remain net of variation by demographics and school.

Experiences of Marginalization

The first set of multivariate models examines whether LGBTQ students are more likely than their classmates to experience marginalization and isolation in their engineering programs (H1), net of controls. Multivariate regression models help determine whether LGBTQ status is a significant predictor of experiences of marginalization, holding constant any variation by gender identity, race/ethnicity, SES, first generation status, and school. Table B presents the regression coefficients, significance levels and standard errors on the LGBTQ status measure and controls for each of the five experiences of marginalization variables. Looking to the first column, which measures students’ perception that they feel accepted by other engineering students, the LGBTQ coefficient is significant and negative (B=−0.214, p<.001). This means that, controlling for variation explained by gender, race/ethnicity, SES, first generation status and school, LGBTQ-identifying students are significantly less likely than non-LGBTQ students to report that they feel accepted by their engineering classmates. LGBTQ students are more likely to report negative experiences along the other marginalization measures as well: net of controls, LGBTQ students are less likely to be included in invitations to social gatherings with their engineering classmates, more frequently avoid social events, are more likely than their peers to feel the need to hide their personal lives from their peers, and are more likely to stay home from school because they do not feel welcome. Finally, LGBTQ students are more likely than their classmates to report having seen or heard offensive comments in their engineering programs.

Consistent with research on the marginalization of women in engineering programs (e.g., Dryburgh, 1999; Faulker, 2009), the models also indicate that women report significantly more negative values on each measure except for the social gatherings measure, compared to men and gender non-binary respondents. The models also indicate marginalization experienced by racial/ethnic minority students: Asian students are more likely than white students to avoid social events and to stay at home from school because they don’t feel welcome, and less likely to feel accepted by other students. Finally, black students are significantly less likely than white students to feel accepted by other students, and Native American/Pacific islander respondents are more likely than white students to report that they feel the need to hide their personal lives at school.

Devaluation of Engineering Work

Next, we examine whether LGBTQ students are more likely than their non-LGBTQ classmates to have their work devalued in their engineering programs (H2). Specifically, controlling for variability by school and demographic factors, we find that LGBTQ students are less likely than their classmates to report that their engineering peers treat them as equally skilled students and respect their engineering work (see Table C). Speaking to students’ potential experiences of devaluation in team settings, LGBTQ students are also more likely to say that they avoid working on certain projects or teams at school.

As with marginalization, we see significant differences by gender and race/ethnicity on these devaluation measures: women are significantly more likely to report devaluation on each measure compared to others, black students are more likely than white students to report that their work is disrespected, and Native American/Pacific Islander students are more likely than white students to report that they have avoided working on certain projects or teams.

Health and Wellness Measures

The third set of measures examines the extent to which LGBTQ students experience negative consequences that carry into their personal health and wellness (H3). Specifically, we investigate whether LGBTQ identity is related to feeling exhausted from spending energy on compartmentalization, the frequency of feeling nervous or stressed, feeling unhappy or depressed at school, and having trouble sleeping to the point that it negatively affects their school performance. We find that LGBTQ status is significantly related to all of these measures, indicating that LGBTQ students experience more negative health and wellness outcomes than their non-LGBTQ classmates (see Table D).

As with the previous measures, we see significantly more negative experiences for women across all measures, that Asian students are more likely than white students to feel exhausted from compartmentalization, that black and Asian students are more likely to feel nervous or stressed, and that Native American/Pacific Islander students and first-generation college students are more likely to have sleeping troubles than whites and non-first generation students, respectively.

Mediation Effects

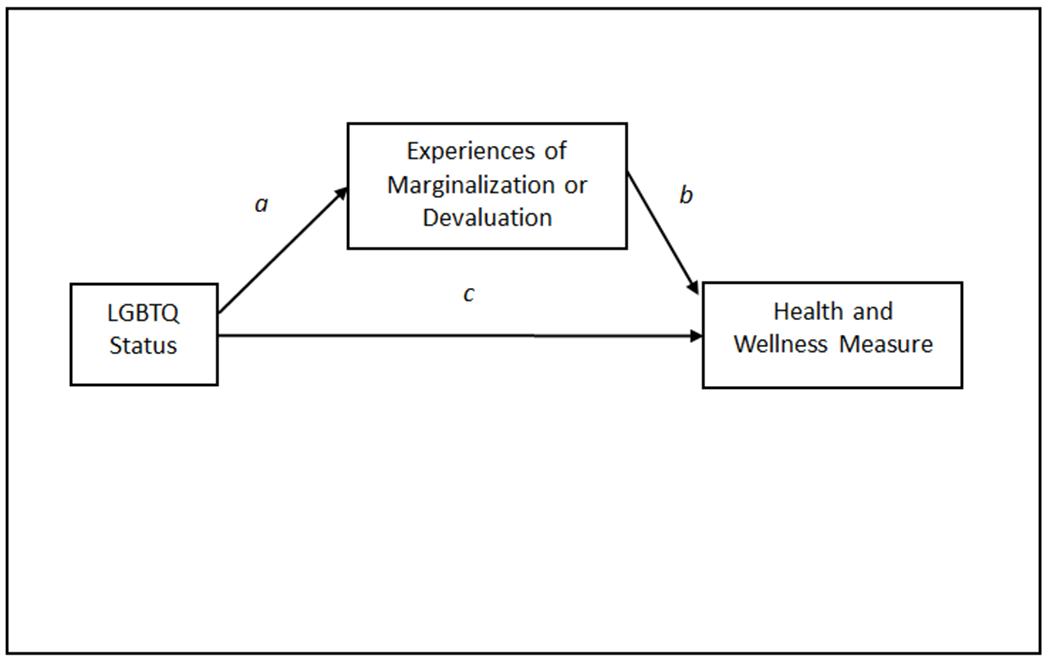

The next set of analyses tests whether these more negative health and wellness outcomes for LGBTQ students (Table D) are partly attributable to their greater likelihood of experiencing marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs (Tables B and C). We test this possibility through mediation analyses with structural equation models. Mediation analysis indicates the extent to which the relationship between LGBTQ status and the health and wellness outcomes can be attributed to the marginalization and devaluation that LGBTQ students experience. Figure A provides a schematic of these relationships. Direct effects between LGBTQ status and the health and wellness measures are represented by path c. The indirect effects through the marginalization or devaluation measures is represented by a*b.

Figure A:

Schematic of Structural Equation Models for Mediation Effects

Table E presents results from mediation analyses in SEM. Specifically, the table provides the coefficients, standard errors, and significance levels for the direct effects between LGBTQ status and the focal health or wellness measure (path c in Fig. A) as well as the indirect paths between the marginalization and devaluation measures and the focal health and wellness measure (a*b in Fig 1). Column 2 presents the indirect effects of the six marginalization measures on each of the four health and wellness measures, and column 3 presents the indirect effects of the three devaluation measures on the four health and wellness measures. Table E also provides CFI and RMSEA fit statistics for each SEM model.

In each case, the indirect effects of the marginalization and devaluation measures is significant and negative, indicating that part of the reason that LGBTQ students report more negative health and wellness outcomes is because they are more likely to encounter devaluation and marginalization in their engineering programs. Column 1 indicates that most of the direct effects between LGBTQ status and the health and wellness measures are still significant, suggesting that there are other factors at play in these negative outcomes beyond marginalization and devaluation—possibly including differential treatment by faculty or more institution-wide biases.

Variation by School Context

Our sample includes students from schools across a spectrum of approaches to engineering education, from a small, religiously-affiliated college, to a regional technical institute, to a large flagship public university. Does the climate for LGBTQ students vary by school context? Table F presents OLS and logistic regression models predicting three indicators of chilly climate for LGBTQ engineering students. Specifically, students were asked to rate their programs on the extent to which LGBTQ students face veiled hostility, whether faculty and students sometimes treat LGBTQ students condescendingly, and whether respondents have observed instances of unfair treatment toward students on the basis of sexual identity or gender expression. Unsurprisingly, LGBTQ students themselves are more likely to report negative climates for LGBTQ persons than their non-LGBTQ peers. Here, we are particularly interested in whether there are large differences across schools in students’ assessment of their engineering programs: many significant school effects would indicate that heteronormativity, transphobia, and heterosexism depend in large part on the particular climate of the engineering program and/or school. Very few school effects would suggest that these LGBTQ biases are similar across these engineering programs. Out of the seven school controls across the three climate measures, only a few significant school differences emerge: net of demographic controls, students at school 117 (large public flagship university in the south) are more likely than students at school 114 (a small religiously-affiliated college, the reference category) to report negative climate for LGBTQ persons across the three indicators. Students at school 109 (small tech school in the Midwest) were more likely than students at school 114 to report that faculty and students are sometimes condescending toward LGBTQ students. There is no other significant variation by school. In supplemental analyses, we replicated these models among LGBTQ students only and find similar consistency in climate across schools.1

Robustness Checks and Supplemental Analysis

To ensure the results above are not an artifact of our modeling strategy, we also tested the hypotheses with several other analytic approaches. First, we re-ran the analyses with the entire sample of respondents (N=2575) regardless of whether they failed the attention check. Second, we replicated the models above without multiple imputation. Third, we replicated the models excluding those schools that had less than 10% response rate. In each of these cases, the patterns of results and statistical significance were replicated.2 Appendix Table A provides the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and results of the post-hoc power analysis for differentials across LGBTQ status on each of the focal outcome measures.

We also conducted supplemental analyses to test for intersectional patterns among LGBTQ students by gender and race/ethnicity. For each marginalization, devaluation, and health and wellness measure, we ran analyses among LGBTQ students only (N=141) to understand if LGBTQ women or LGBTQ students of color (using a dichotomous indicator for whether students identify as nonwhite) more frequently reported negative experiences within their engineering programs when compared to white LGBTQ men (there are 85 women and 21 students of color in the LGBTQ sample). Although a larger dataset is necessary to parse out these intersectional patterns in depth, we did find a few patterns of note. Specifically, LGBTQ-identifying women are marginally more likely than other LGBTQ students to report encountering offensive comments (B=.444, p=.079) and marginally less likely to report that their classmates treat them with respect (B=−.275, p=.073). The nonwhite status indicator did not reach statistical significance in these models, perhaps due to the small sample of nonwhite LGBTQ students. More detailed analyses with larger samples are needed to articulate these intersectional patterns along specific racial/ethnic categories.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this paper was to examine whether LGBTQ students face significant disadvantages in their engineering programs compared to their classmates. These data provide the first opportunity to systematically compare the day-to-day experiences of LGBTQ-identifying individuals with their non-LGBTQ-identifying peers in the same engineering programs and to identify several axes along which these disadvantages manifest.

We identified three such areas of inequality. First, we found that LGBTQ students are significantly more likely than non-LGBTQ students to experience marginalization in their engineering programs. Not only do LGBTQ students feel less accepted and more ignored by their classmates, they are less comfortable joining social events with peers and more likely to avoid participating in group projects. They are also more likely to report hearing or reading derogatory comments in their engineering programs. Second, LGBTQ students are less likely than their peers to feel that their work as engineering students is respected. So, not only is LGBTQ inequality an issue of social isolation within engineering education, but one of professional devaluation as well. This resonates with qualitative research which finds that many sexual minority students feel they have to give “110%” to be taken seriously (e.g., Cech & Waidzunas, 2011).

Third, our findings suggest that these difficulties take their toll on LGBTQ students personally: compared to their peers, LGBTQ students are significantly more likely to report emotional, sleeping, stress, and anxiety difficulties and are more likely than their classmates to feel exhausted by efforts to compartmentalize their lives. Importantly, we found that these negative health and wellness outcomes are partly explained by LGBTQ students’ experiences of marginalization and devaluation in their engineering programs.

Finally, we investigated the extent to which the negative climate for LGBTQ students varies by school. Although the schools in our study range from a top-rated flagship public institution to a small, religiously-affiliated private school, there did not appear to be drastic variation in the climate for LGBTQ persons across the engineering programs in these schools. Supporting previous theoretical, ethnographic, and interview-based research (Cech & Waidzunas, 2011; Faulkner 2009; Schiebinger, 1999), this lack of strong variation across schools suggests that anti-LGBTQ bias is not just a manifestation of the climate of individual programs but part of the culture of engineering education more broadly—embedded in its taken-for-granted practices and ideologies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, our dataset is not large enough to explicate detailed intersectional patterns with race/ethnicity, gender, and other demographic categories, nor to disaggregate categories within the LGBTQ acronym. Second, the students in this study came from programs where the Dean expressed support for the ASEE Diversity and Inclusion Survey and agreed to let us collect data from their students. It is likely that these programs may be more concerned than others about issues related to diversity and inclusion within their student populations. Thus, the results from this study may actually provide conservative estimates of the disparities between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ engineering students as they pertain to devaluation, inclusion, and health and wellness outcomes. Finally, our goal was to sketch the landscape of possible LGBTQ biases in engineering education. Space limitations in the survey meant that we were unable to include multivariate measures of each of the dimensions of marginalization, devaluation, and health and wellness outcomes we investigate. We leave it up to future studies to develop and test scales that more precisely operationalize these LGBTQ biases. Despite these limitations, this research makes important strides in understanding an often-ignored axis of disadvantage.

Implications

How can engineering programs best support LGBTQ students? Engineering program administrators and faculty can take a number of approaches to improve the climate of their programs for LGBTQ students. These could include “Safe Zone” trainings that educate students and faculty on appropriate language and inclusionary behavior toward LGBTQ members of the college or university. Additionally, fostering a zero-tolerance policy for homophobic and transphobic joking and commentary may mitigate some of the most blatant anti-LGBTQ sentiments that students encounter. Similarly, thinking carefully about language use in formal engineering program communication and information structures is important. For example, using “partner” instead of “spouse” or “husband/wife” and allowing students and faculty to designate—and be referred to by—their preferred gender pronouns are important steps in making LGBTQ persons feel more welcome. Changes to the built environment, such as gender neutral bathrooms in campus buildings, can further support transgender and gender non-binary students.

Second, ensuring that a variety of underrepresented demographic categories, including LGBTQ status, are included in the non-discrimination statements on college and graduate school application materials, engineering course syllabi, and departmental websites can be an important step signaling support for LGBTQ students. Similarly, it would be impactful to make visible openly-LGBTQ engineering graduates and professionals who have “made it” in the profession—by, for example, including openly-LGBTQ persons in colloquia and speaker series in engineering departments or profiling the work of LGBTQ engineering alumni on departmental websites, brochures, and recruiting materials. The representation in these capacities of LGBTQ persons who have been successful in engineering sends a message to LGBTQ students (and their peers) that they, too, belong in the profession. Further, collaborating with and/or supporting membership in organizations for LGBTQ-identifying individuals in engineering such as oSTEM and partnering with campus LGBTQ student centers can help foster a more positive school climate for LGBTQ engineering students. Like Yoder and Mattheis (2016), we recommend working to increase the visibility of LGBTQ programs and advocacy efforts in engineering education programs so that students feel comfortable developing advantageous connections with students and professionals who share similar identity characteristics.

Additionally, our results suggest that LGBTQ students report more negative health and wellness outcomes due in part to the devaluation and marginalization they experience within their engineering education programs. These findings highlight the potentially serious impact that negative engineering program climates can have on members of marginalized groups. Persistent experiences of stigmatization and devaluation within engineering education programs can get under students’ skin—impacting not only students’ quality of life within their engineering programs, but also their very health and wellness. These are serious outcomes that demand administrative attention and resources and collective effort by faculty and student allies.

Future Research

Our findings make clear the need to better understand the mechanisms of LGBTQ inequality—how is it perpetuated in informal departmental interactions and through the engineering culture and curriculum, and how best to subvert these patterns of inequality. Much more research is needed to explicate the long-term impacts that disadvantageous engineering cultures have on the retention and representation of LGBTQ individuals in the engineering profession. Research that develops and tests quantitative measures of heteronormativity, heterosexism, and transphobia within engineering contexts is also needed to advance survey-based research and qualitative and ethnographic work is required to precisely document how these patterns of bias are enacted by students and faculty on a day-to-day basis.

As with scholarship on other axes of disadvantage, it is imperative that researchers are sensitive to the sociodemographic and identity complexities of the LGBTQ population, even if, as in our case, these complexities sometimes cannot be disaggregated in published scholarship so as not to risk the confidentiality of respondents. Like all research on marginalized populations, studies of LGBTQ persons should not be conducted simply as a desire to fill “broader impact” requirements on substantively unrelated research grants and projects, but as deliberate efforts that pay careful attention to relevant theoretical and empirical work in social science and queer theory on heterosexism, homophobia, and transphobia. The potential invisibility of students’ LGBTQ status also means that researchers should take great care to protect research participants from breaches of confidentiality in data collection, analysis, and reporting. LGBTQ-inclusive engineering education research, like inclusive engineering pedagogy, must start from respect for and attention to voices and perspectives of disadvantaged group members themselves.

CONCLUSION

In detailing the experiences of marginalization and devaluation that LGBTQ students face, this study advances scholarly understanding of an often-ignored axis of difference. We show that these inequalities for LGBTQ students not only impact their day-to-day interactions with their classmates, but influence whether they are perceived as competent engineering trainees and even reach into their personal lives to negatively impact their health and wellness. This study also draws attention to engineering education as a site that helps reproduce professional cultures that disadvantage LGBTQ individuals in engineering more broadly. Through the process of professional socialization, anti-LGBTQ biases may become entrenched in students’ understanding of what makes “good” engineers and what concerns are tangential to “real” engineering work—understandings that students take with them into the engineering workforce. Further, because the perpetuation of these anti-LGBTQ biases in engineering education and beyond do not necessarily rely on purposeful, overt displays of bias—for example, non-LGBTQ students may not exclude LGBTQ students in an overt or blatant way—the processes that reproduce these LGBTQ inequalities may be difficult to recognize and thus particularly difficult to challenge. Reflexive and theoretically-anchored research, combined with serious commitments from engineering faculty and program leaders for institutional and cultural change, are necessary to being to undermine these inequalities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2017 American Society for Engineering Education Conference (Cech, Waidzunas, and Farrell 2017) and received the 2017 ASEE Best Diversity Paper Award. We thank Stephanie Farrell, Tom Waidzunas, and Heidi Sherick for feedback on study design and previous versions of the paper; Rocio Chavela and Brian Yoder for their assistance with the ASEE Diversity and Inclusion Survey; and Michelle Pham and Madison Martin for expert research assistance. This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (grant 1539140; PI: Stephanie Farrell; Co-PIs: Rocio Chavela Guerra, Erin Cech, Tom Waidzunas, and Adrienne Minerick). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

APPENDIX

Appendix Table A:

Effect Sizes and Power Values of Mean Differences between LGBT vs Non-LGBT Respondents

| LGBT vs. non-LGBT | Power | |

|---|---|---|

| Marginalization | ||

| Accepted by students in department | .391 | .962 |

| Avoided social event | .525 | .993 |

| Feel included in social gatherings | .353 | .901 |

| Hide personal life | .789 | .999 |

| Stayed home because didn’t feel welcome | .476 | .967 |

| Offensive comments | .416 | .993 |

| Devaluation | ||

| Treated as equally skilled student | .317 | .928 |

| Students respect engineering work | .314 | .869 |

| Avoided team or project | .518 | .998 |

| Health and Wellness | ||

| Exhausted from compartmentalization | .346 | .961 |

| Nervous | .370 | .996 |

| Depressed or sat at school | .518 | .999 |

| Sleeping troubles | .283 | .999 |

Note: Columns above represent Cohen’s d effect sizes [d=difference in means / pooled standard deviation] on differences in means on each outcome measure between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ respondents.

Footnotes