Abstract

Purpose

Disability data inform resource allocation and utilization, characterize functioning and changes over time, and provide a mechanism to monitor progress toward promoting and protecting the rights of individuals with disability. Data collection efforts, however, define and measure disability in varied ways. Our objective was to see how the content of disability measures differed in five US national surveys and over time.

Methods

Using the WHO ICF as a conceptual framework for measuring disability, we assessed the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), Current Population Survey (CPS), Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), National Survey of SSI Children and Families (NSCF), and American Community Survey (ACS) for their content coverage of disability relative to each of the four ICF components (i.e., body functions, body structures, activities and participation, and environment). We used second-level ICF three-digit codes to classify question content into categories within each ICF component and computed the proportion of categories within each ICF component that was represented in the questions selected from these five surveys.

Results

The disability measures varied across surveys and years. The NHIS captured a greater proportion of the ICF body functions and body structures components than did other surveys. The SIPP captured the most content of the ICF activities and participation component, and the NSCF contained the most content of the ICF environmental factors component.

Conclusions

This research successfully demonstrated the utility of the ICF in examining the content of disability measures in five national surveys and over time.

Keywords: Disability, Survey, ICF, Data, Coding, Impairment

Introduction

Disability data inform decisions about resource allocation and utilization, characterize functional changes over time, and provide a way to monitor progress toward promoting individuals with disability as fully engaged societal members [1, 2]. Unfortunately, the varied approaches used to measure disability lead to substantial variation in disability rates. For instance, the international rates of disability prevalence range from 1 to 20 % [3] depending on the country. In the USA, the 2011 disability prevalence rate reported by the American Community Survey (ACS) was 12.1 %. The Current Population Survey (CPS) reported 8.1 %, and in the 2000 Census, the rate was 9.7 % [4].

While there are a range of factors that may contribute to actual differences, variance in disability rate is substantially influenced by whether disability is defined at the impairment, the activity, or the participation level [1]. The historical context for this distinction has roots in the medical model, which framed disability solely as impairment at the level of the individual. Contemporary perspectives define impairment as the manifestation of physiological or structural pathology (ibid). More current perspectives of disability account for activity (a task completed by an individual), participation (societal functioning), and contextual factors (such as environmental barriers). Focusing solely on impairment not only fails to describe the functional consequences of the impairment, but tends to underestimate prevalence rates of disability at the population level [1].

Historically, Asian and African countries tended to capture disability at the impairment level and reported lower rates of disability compared with European and North American countries, which used activity/participation questions. Appreciation for methodological variation, along with other important factors such as sociocultural beliefs about disability, contributes to the understanding of regional differences [5]. While counts of conditions and diagnoses continue to play a role in calculating incidence and prevalence rates [6], activity/participation questions provide a mechanism to examine the way impairment influences daily life, providing crucial information that may shape policy approaches to social programs.

Fortunately, over time, our perspectives on disability have moved beyond the concept that impairment equals disability. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), now the gold standard for the conceptual understanding of disability, recognizes disability as the outcome of the interaction between a person with a health condition and contextual factors (both environmental and personal). This interaction may encompass impairment of body structure/function, activity limitation and participation restrictions [7]. As our understanding of the disability phenomenon has evolved, we know that questions capturing impairment information yield substantially different data outcomes than questions about activity or participation. This distinction is important when using data to inform program and policy decisions.

The ICF provides a holistic conceptual framework and a standard coding system for describing states of health and disability [13]. With this in hand, we can identify conceptual gaps and discuss approaches to improve our disability measures. In addition to providing a detailed listing of domains that describe human functioning in terms of body structure, body function, activity, and participation, the ICF also includes a list of environmental domains, appreciating that an individual’s functioning and disability are influenced by contextual factors. Since impairment does not fully explain human functioning, further investigation into relationships, such as the influence of environment on participation, is needed to further understand the role of context on engagement in social roles.

The existing literature supports the utility of the ICF in evaluating health and disability-related data content and helping us to learn more about the data we are collecting (e.g., Are we collecting the type of information needed to inform decision making?). For instance, the ICF has been used to compare instruments designed for specific subpopulations with health conditions and inform instrument selection [8–12], and to study questionnaire content coverage [13, 14]. It has also been used to examine the range of domains captured by an instrument within a particular ICF component, such as the examination of questionnaires relative to the ICF activity and participation component [15–18]. Investigators have developed coding rules to systematically link health status measures to ICF components [19, 20]. The coding guidelines developed for this work build upon prior research [13, 14, 21].

While the purpose of motivating the collection of disability data varies, a single conceptual lens through which surveys and censuses may be viewed provides an opportunity to maximize the utility of the information captured across instruments. Although most of these data collection instruments were designed to collect information from individuals with specific health conditions, we know little about how disability is conceptualized in US nationally representative surveys. This research demonstrates the use of the ICF as a tool to critically examine national surveys in an effort to make more informed choices with respect to the use of survey data or developing survey questions.

The primary objective of this research was to examine the conceptual composition of disability questions selected from five US surveys to see how the proportion of ICF components varies among the surveys and changes over time. Understanding the content of survey questions using a consistent conceptual framework helps to reveal conceptual variation that might influence future development or refinement of an instrument, or use of the data. A survey that captures information focused on body structure and body function is helpful in the examination of impairment, yet less useful when attempting to understand functioning of the whole person. Furthermore, survey questions that capture environmental context may uncover facilitators and barriers that influence functioning in terms of activity and participation and yet remain external to the individual. This research reports on use of the ICF framework as an analytical tool to examine individual survey content and to compare conceptual content across surveys. This approach transcends individual survey characteristics in a manner that permits comparative analysis.

Methods

Selection of survey questions

We identified five national surveys that contained questions relevant to people with disability and have been widely used by researchers and policy makers to estimate disability in the US. Selection of these surveys was also motivated by the ability of these surveys to link with administrative data sets, thereby providing a more complete picture of disability benefit recipients. Although the surveys selected are designed for different purposes, these survey data are frequently used by researchers, administrators, and policy makers to estimate disability prevalence [4, 22–26]. These surveys include the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), Current Population Survey (CPS), Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), National Survey of SSI Children and Families (NSCF), and the American Community Survey (ACS). We screened survey questions that asked about a respondent’s health status, health conditions, mobility, functioning, activities, and program participation due to disabilities or impairments. For comparative purposes, we excluded questions that were not surveyed regularly, including questions from the CPS supplement files (i.e., the veterans, civic engagement, voting and registration, and public participation in the arts supplement files). Table 1 presents the source and type of questions selected from each survey.

Table 1.

Source and type of selected qüestions by survey

| ACS (1996–2011) | CPS (2006–2011) | NHIS (2006–2010) | SIPP (1996, 2001, and 2004 panels) | NSCF (July 2001-June 2002) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Topics/data source | Person | Basic monthly survey March CPS annual social and economic supplement file Volunteers supplement file |

Sample adult file Person file |

Core module Adult functional limitations and disability topical module (1–2 times in each panel) |

Disability status and functional limitations Education and training Other programs and Services SSI experience Employment Housing and transportation |

| Sample age | ≥15 | ≥15 | ≥18 | ≥15 | 0–23 (children and young adults with special health care needs and their families who received or applied for SSI)a |

| Survey design | Cross section; annual | Rotating panel (4—8—4 pattern); monthly, annual. | Cross section; annual | Panel (2½—4 years each panel) | Cross section; one time |

| Type of record | Person record | Person record | Person and, sample adult record | Person record | Person record |

We only selected qüestions relevant to young adults (aged 18–23) for coding purpose

To longitudinally examine the content coverage of the survey questions, we began by reviewing questions from the most recent survey year and, as available, reviewed questions of preceding years of the survey for at least 5 years. However, not all surveys were conducted yearly. The NSCF was only conducted once. The SIPP is a panel survey, and each panel usually lasts from 2½ to 4 years. Therefore, we scanned questions from the three most recent SIPP panels (1996, 2001, and 2004). The ACS is an ongoing survey that provides data every year but it contains fewer numbers of questions of interest as compared to other four surveys. Therefore, ten additional years of questions from the ACS were reviewed.

Coding question content and guidelines

Each ICF component consists of various domains that identify more granular levels of domain specificity in a hierarchical fashion. These levels are units of classification, such as ICF second- and third-level codes. To assess the content coverage of these survey questions, we applied the WHO ICF second-level codes (three digits) to classify the content of each selected question into five major components: (1) body functions, (2) body structures, (3) activities and participation, (4) environment, and (5) health status/health conditions. Four out of these five components are the ICF components (i.e., body functions, body structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors). The fifth component (health status/condition) was used to identify survey content that captured health-related information more broadly. Survey questions could be classified into one or more of these five components. For instance, a question asking about the use of an assistive device, such as a cane or walker, to get around would be classified into two ICF components: one from the ICF activity/participation component (d465: moving around using equipment) and another from the environment component (e120: use of products for mobility). In addition to the ICF coding guidelines established in the literature [19, 20]), we developed additional coding guidelines to ensure that our coding decisions were made consistently. A list of general coding guidelines is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Additional content coding guidelines

| 1. Use two-level classification codes from the ICF body functions, body structures, or both components to classify health conditions or disorders as appropriate a. Use exactly matched ICF two-level classification codes to classify the content of the question. b. Avoid using “unspecified” or “other specified” ICF codes 2. Apply one of the following approaches if the content of a question is too broad to be classified (i.e., no exactly matched ICF code(s) and requiring a broad range of ICF codes): a. If applicable, use exactly matched ICF two-level classification codes to classify the content of examples provided in the question; b. If applicable, use exactly matched ICF two-level classification codes to classify the response choices c. Do not code the content of a question if its examples and response choices are not given or are too broad. For instance, the content of an open-ended question (e.g., why, when, where, what, how, and who) can be too broad to find an exactly matched ICF code (or codes). In this case, we can classify its response choices using the ICF codes. However, it is possible that response choices of a question are also too broad to be classified. Then, none of the ICF codes are used d. Use the ICF codes d845 and d850 to classify the concept of “seeking employment and/or getting a job” because the concept is currently captured by both ICF codes 3. Classify specific health conditions or disorders (e.g., hypertension, asthma) into the “health status/health condition” category, body functions, and/or body structures as appropriate 4. Do not classify disease symptoms (e.g., trouble seeing or hearing) into the “health status/health conditions” category because they are different from heath conditions or disorders (e.g., glaucoma, deaf). Nevertheless, like health conditions, disease symptoms can be classified into body functions, body structures, or both using the ICF classifications codes 5. If none of the ICF codes are applicable to the health condition(s) in the question, then mark health status/health condition category in the coding template 6. Do not classify the same content again in questions with a skip/ branch pattern |

Content coverage

As stated earlier, we used second-level ICF codes to classify the content of each question and computed content coverage of each survey by ICF component. By definition, content coverage was the proportion of ICF categories within each ICF component that was represented in the questions selected from these five surveys. The numerator was the total number of categories within each ICF component captured in the survey questions. ICF codes were counted only once regardless of the number of questions that included the same code. The denominator was the total number of second-level codes within each ICF component, excluding unspecified and other specified codes. For example, in the body functions component, there is a total of 79 second-level codes (excluding other specified and unspecified codes). Of these second-level codes, 31 were captured in the 2010 NHIS questions. Therefore, the content coverage of the body functions component represented in the 2010 NHIS questions was 39.2 %. For comparative purposes, the content coverage was presented graphically by type and year of the survey. Our computation of content coverage focused on the four components included in the ICF. We did not attempt to quantify the health condition data since that is beyond the scope of the ICF.

To ensure quality and objective results, two researchers coded the content of these questions independently. Prior to coding survey questions to the ICF components, they reviewed coding rules and guidelines and evaluated a subset of questions as part of a training procedure. Results of this exercise were used to understand discrepancies between the coders and to further develop and refine coding guidelines. The coding procedure started with the identification of the meaningful concepts contained within each selected question. The two researchers then translated the meaningful concepts into corresponding ICF categories, which most precisely represented the concepts. Coding results from both researchers were compared and cross-validated. If there were discrepancies in the results that could not be reconciled between these two investigators, a third opinion was sought from an expert with extensive research experience in the disability and measurement field.

Results

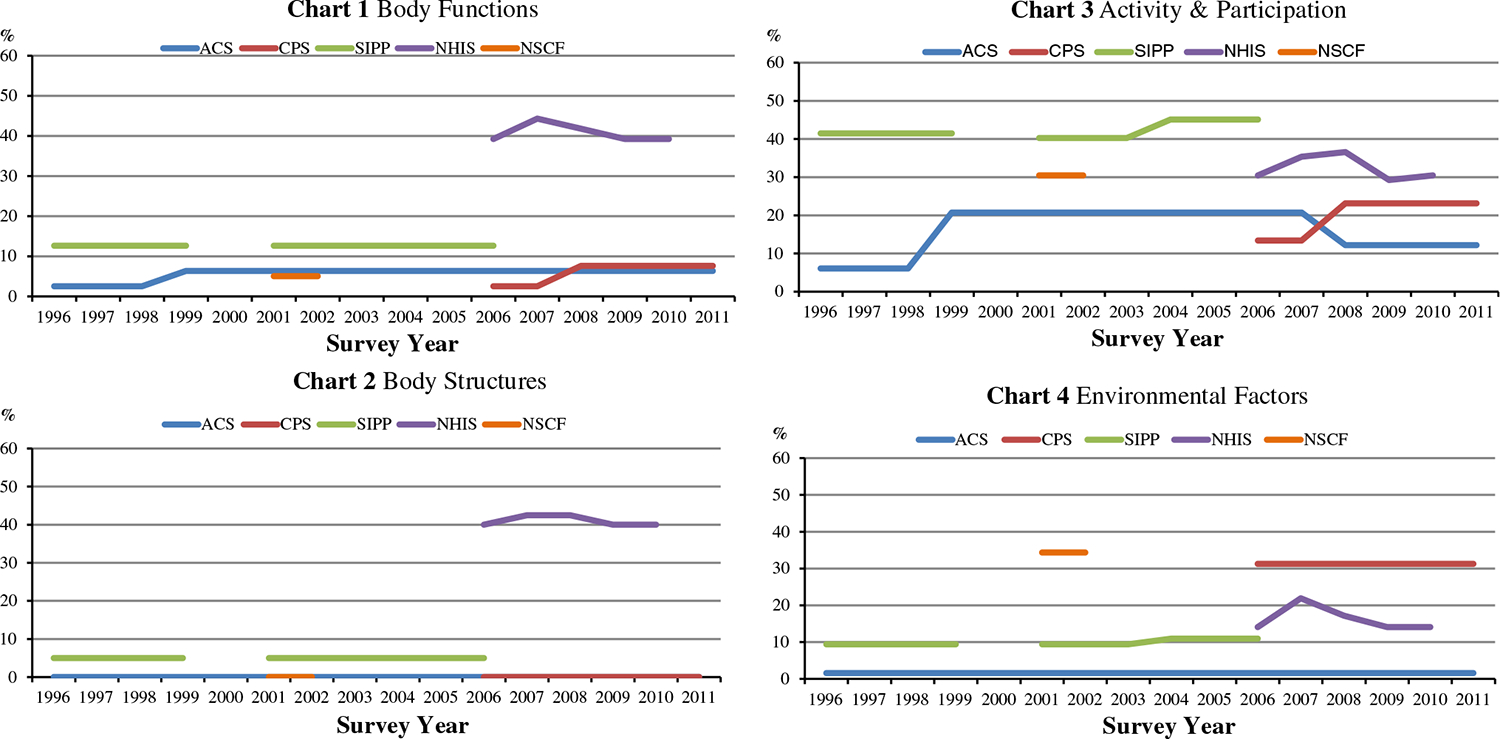

We selected 917 questions from five national surveys: 284 from NHIS (2006–2010), 296 from CPS (2006–2011), 135 from SIPP (1996, 2001, and 2004 panels), 158 from NSCF (July 2001–June 2002), and 44 from ACS (1996–2011). These questions were selected because they solicited information concerning health, disability, functioning, and participation in an activity or a program (e.g., leisure, work, or school). Figure 1 presents ICF content coverage represented in questions selected from each survey and linked to categories within each of the four ICF components: body function, body structure, activities/participation, and environment.

Fig. 1.

ICF content coverage by survey and survey year

Representation of body functions

The first chart in Fig. 1 presents the proportion of ICF body functions component represented by questions selected from each survey. Questions from the NHIS captured a greater proportion of the ICF body functions component (ranging from 39.24 to 44.30 %) than did the other surveys examined. We found the proportion of SIPP questions capturing information about body functions remained stable over time. The proportion of the body functions component increased in the ACS and CPS in 1 year (1999 for ACS and 2008 for CPS) and then remained stable for several years. For the NHIS, the proportion of this ICF component increased in 1 year (2007) and then decreased in the following years (2008 and 2009). Approximately five percent of the categories within the body functions component were represented in questions selected from NSCF.

Representation of body structures

The second chart in Fig. 1 shows that none of the questions selected from the ACS, CPS, and the NSCF were linked to categories within the ICF body structures component. Some questions in the SIPP and NHIS were linked to categories within the body structures component of the ICF; however, the proportions were quite different (40–42.5 % for the NHIS and 5 % for the SIPP).

Representation of activity and participation

The third chart in Fig. 1 displays the variation in content coverage in the activity and participation component represented in the questions selected from the five surveys. Questions from the SIPP encompassed at least 40 percent of the categories within the ICF activity and participation component over time. Except for the NSCF, the content coverage of activity and participation fluctuated in each survey over time. For the ACS, CPS, and the SIPP, the proportion of this ICF component changed in year one and then remained stable for a period of time. However, for the NHIS, this content coverage changed slightly every year.

Representation of environmental factors

As shown in the fourth chart in Fig. 1, all five surveys capture some degree of the environmental factors component of the ICF. Questions from the NSCF (34.4 %) and the CPS (31.3 %) covered at least 30 % of the categories of this ICF component, whereas questions from the ACS covered less than two percent of the categories of this ICF component (1.6 %). Unlike the other four surveys, the content coverage of the NHIS fluctuated almost every year (2006–2009). For the SIPP, the content coverage of this ICF component remained relatively stable over time (between 9.4 and 10.9 %).

Overall, the extent of the ICF categories captured in the questions selected from five national surveys varied among the surveys and often over time. Of the surveys we examined, the NHIS contains the most content linked to the ICF body structures and body functions components; the SIPP captures the most content of the ICF activities and participation component; and the NSCF contains the most content of the ICF environmental factors component. Interestingly, none of the questions selected from the ACS, CPS, and NSCF address the body structures component of the ICF. The content associated with ICF components represented in the NHIS tends to fluctuate almost every year.

The five surveys demonstrate variation not only in content coverage among the ICF components, but also in terms of the sub-domains captured within each particular ICF component. This means the survey data do not capture a comprehensive range of sub-domains within an ICF component and leave potential gaps in coverage. While the SIPP demonstrates the greatest coverage of the ICF activities/participation component, the SIPP is the only survey that includes questions on the interpersonal interactions and relationships sub-domain of the ICF activities/participation component (Fig. 2). The CPS and NHIS include questions capturing recreation and leisure, part of the community, social and civic life sub-domain in the activities/participation component, measures not found in the other surveys. Remarkable variation among the surveys in terms of the ICF environment component is noted, as well (Fig. 3). The NSCF captures a substantially higher proportion of environment codes compared with the other surveys; however, the NSCF was only administered from July 2001 to June 2002.

Fig. 2.

Content coverage of ICF activities and participation domains by survey

Fig. 3.

Content coverage of ICF environmental domains by survey

While all of the surveys examined capture a smaller proportion of environmental content compared with activity/participation content, the importance of environmental factors for individuals with disability is particularly relevant. As mentioned in the ICF [7], environmental factors may serve as barriers or facilitators to disability. It is difficult to fully appreciate how impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions may contribute to disability without consideration for environmental factors. Environment alone may contribute to varied functional levels for individuals with the same health condition [27].

Discussion

Current debates in disability research in the USA are centered on the distinction between the activity and participation component of disability and the potential role of environment in distinguishing between the two [28]. Recent research reveals the six-question disability set [29] recommended by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHSs), as a minimum standard measure of disability, may only be a first step in capturing populations of people with disability who receive income support through the Social Security Administration’s (SSAs) Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income programs [30], the nation’s largest disability programs. This debate focuses on the inclusion or exclusion of a “work” question in disability measurement. Including a participation questions such as this, implicates a host of potential environmental factors, such as assistive products and technologies intended to improve functioning; economic and labor policies that may enhance employment of individuals with disability; transportation policy that may influence access and use of transportation services; and natural and human-made environmental conditions that may influence mobility in built and natural environments. These factors ultimately influence participation. With this in mind, the inclusion of a participation question without addressing environmental factors “muddies” the conceptual waters and further complicates disability measurement [28].

On the other hand, the absence of participation data may fail to adequately capture populations served by public programs, regardless of whether participation restrictions are due to changes in functioning or environmental barriers. This omission may underreport the need for public programs. The debate over conceptual clarity is important, particularly when these data are used to inform programmatic and/or policy solutions.

Not all surveys cover all ICF domains, and often, federal legislation and national health priorities dictate the type of information collected. Given the often remarkable constraints underpinning survey development, this study is not intended to persuade or dissuade inclusion of ICF content in survey development. This research illustrates the importance of applying a single, conceptual lens across surveys to detect methodological variation that looks beyond psychometric properties. If survey questions do not capture data at a desired or intended conceptual level, psychometric properties, such as validity and reliability, may be less relevant. In this research, the ICF was a useful tool permitting comparison of national surveys, which often provide policy-relevant data.

Our study suggests that disability data likely capture different facets of the disability experience. This means that surveys collecting disability data are measuring different aspects of the disability concept. Furthermore, there is no single federally sponsored national survey that comprehensively collects data across the range of issues relevant to people with disability [31]. In fact, there appears to be a paucity of information collected about issues, such as participation in social roles, transportation, and environmental barriers [ibid]. Since contemporary paradigms consider disability the outcome of the interaction between an individual with a health condition and environmental demand, failure to capture data about environmental characteristics limits the ability to fully understand the disability experience and to make informed policy decisions important to people with disabilities.

In summary, the approach of linking survey questions to the ICF has several merits. It permits a quantitative assessment of the extent to which a survey captures information relative to components of functioning, as defined in the ICF. In addition, the coding process facilitates the ability to identify ICF domains/sub-domains of functioning not captured by the survey. In this respect, ICF coding serves as a mechanism to critique the type of data collected by a survey. This research highlights the utility of ICF as a framework to facilitate comparison across surveys. Future research should also consider different response choices (yes/no vs. a scaled response), target survey populations, sample sizes, and survey designs (e.g., longitudinal vs. cross-sectional) that may influence the utility of information collected.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, some ICF codes are not mutually exclusive. For instance, the activity of seeking employment is included in two ICF categories, i.e., d845 (acquiring, keeping, and terminating a job) and d850 (remunerative employment). Should all potentially relevant codes be selected when parsing and linking key survey terms to ICF codes, the proportion of ICF coverage will appear higher compared with selection and use of the one, best ICF code per key survey term. In other words, survey questions may appear to capture a higher proportion of ICF domains due to a lack of exclusivity among ICF codes. It is also unclear if d825 (vocational training) includes an integrated vocational education in a high school, a state-sponsored vocational rehabilitation program, or both. A detailed classification in some of the ICF domains is also needed. For instance, the category of higher education can be further classified into full time and part time. Although the ICF categorizes attitudes of various individuals (e.g., family members, friends, strangers, and professionals), none of these categories contain attitudes of self.

Another limitation is that this study focuses solely on survey questions and not the associated response choices. For instance, the SIPP seeks yes/no responses to questions regarding difficulty walking up a flight of 10 stairs and walking a quarter of a mile—about three city blocks. In contrast, the NHIS asks participants to specify how difficult it is to walk up 10 steps without resting and to walk a quarter of a mile—about three city blocks given the following response choices: not at all; only a little; somewhat; very difficult; cannot do at all; and do not do this activity. Clearly, the NHIS response choices capture greater detail about these activities compared with the SIPP. We envision that coding response choices will provide a more comprehensive picture of the ICF domains captured by each survey. This will be an important consideration for future work.

While this research effort was applied to a small sample of US surveys, the coding guidelines established in previous research and extended in the current work advance the utility of the ICF as a framework to examine how disability is conceptualized within each survey instrument and permit comparative assessment across surveys. In this regard, national and international comparisons are more feasible and ripe for development in future efforts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research demonstrates the importance of critically examining data captured and illustrates how a consistent conceptual framework may inform approaches to analyze survey and census question content. To fully understand both direct and indirect costs of impairment and to appreciate the range of functioning associated with similar impairments, perspectives of disability, and resultant disability measures must appreciate the manifestation of impairment in terms of functioning. Furthermore, to measure participation in social roles, disability measures much appreciate the role of environmental factors, as barriers or facilitators, to human functioning and disability. Use of a common, conceptual lens provides the ability to compare data content across surveys used within the USA and to compare US data with other countries. Ultimately, these data influence the lives of individuals living with disability and help shape our social consciousness about disability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to Barbara Altman, PhD for her guidance in this project and to Zabelle Zakarian, ScD, for her ICF coding suggestions. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Clinical Research Center and through an Inter-Agency Agreement with the US Social Security Administration. This manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Contributor Information

Diane E. Brandt, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, 6100 Executive Blvd. Rm. 3C01 MSC 7515, Bethesda, MD 20892-7515, USA

Pei-Shu Ho, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, 6100 Executive Blvd. Rm. 3C01 MSC 7515, Bethesda, MD 20892-7515, USA.

Leighton Chan, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Building 10, Room 1-1469 10 Center Drive, MSC 1604, Bethesda, MD 20892-1604, USA.

Elizabeth K. Rasch, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, 6100 Executive Blvd. Rm. 3C01 MSC 7515, Bethesda, MD 20892-7515, USA

References

- 1.World Health Organization and United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. (2008). Training manual on disability statistics. Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field MJ, & Jette AM. (Eds.). (2007). The future of disability in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mont D (2007). Measuring disability prevalence Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornell University Employment and Disability Institute. (2012). Disability statistics. 2012. http://www.disabilitystatistics.org/reports/acs.cfm.

- 5.Statistical Office Department of International Economic and Social Affairs Statistical Office. (1990). Disability statistics compendium. In Statistics on special populations. Publishing Division, United Nations: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott S, & Turk MA (2011). The myth and reality of disability prevalence: Measuring disability for research and service. Disability and Health Journal, 4(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borchers M, et al. (2005). Content comparison of osteoporosis targeted health status measures in relation to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Clinical Rheumatology, 24, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cieza A, & Stucki G (2005). Content Comparison of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) instruments based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Quality of Life Research, 14, 1225–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geyh S, et al. (2007). Content Comparison of Health-related Quality of Life measures used in stroke based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 16, 833–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stucki A, et al. (2008). Content Comparison of Health-Related Quality of Life instruments for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Medicine, 9(2), 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tschiesner U, et al. (2008). Content Comparison of Quality of Life Questionnaires used in head and neck cancer based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: A systematic review. European Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 265, 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriello C, et al. (2008). Mapping the Stroke Impact Scale(SIS-16) to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 40, 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasiak J, et al. (2011). Measuring common outcome measures and their concepts using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in adults with burn injury: A systematic review. Burns, 37, 913–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stucki G, et al. (2008). ICF-based classification and measurement of functioning. European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation, 44, 315–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magasi S, & Post M (2010). A comparative review of contemporary participation measures’ psychometric properties and content coverage. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(9 Suppl 1), S17–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairbairn K, et al. (2012). Mapping Patient-specific Functional Scale (PSFS) items to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Physical Therapy, 92(2), 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnik L, & Plow M (2009). Measuring participation as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: An evaluation of existing measures. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90, 856–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cieza A, et al. (2002). Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 34(5), 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cieza A, et al. (2005). ICF linking rules: An update based on lessons learned. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 37(4), 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fekete C, et al. (2011). How to measure what matters: Development and application of guiding principles to select measurement instruments in an epidemiologic study on functioning. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90(11 Suppl 2), S29–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Census Bureau. (2014). Disability. http://www.census.gov/people/disability/.

- 23.Kraus LE, Stoddard S, & Gilmartin D (1996). Chartbook on disability in the United States, 1996. http://infouse.com/disabilitydata/disability/index.php.

- 24.Social Security Administration. (2014). National Survey of SSI Children and Families (NSCF). http://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/nscf.htm.

- 25.Nicholas J (2013). Prevalence, characteristics, and poverty status of supplemental security income multirecipients. Social Security Bulletin 73(3), 11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.University of California, S.F. (2014). Disability statistics center. http://dsc.ucsf.edu/main.php?name=resources. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker H (2006). Measuring health among people with disabilities. Family and Community, 29(1 Suppl), 70S–77S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman BM (2013). Another perspective: Capturing the working-age population with disabilities in survey measures. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. doi: 10.1177/1044207312474309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madans JH, Loeb ME, & Altman BM (2010) Measuring disability and monitoring the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: The work of the Washington group on disability statistics. BMC Public Health, 11(Suppl 4), S4–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burkhauser R, et al. (2012). Using the 2009 CPS-ASEC-SSA matched dataset to show who is and is not captured in the official six-question sequence on disability. In 14th annual joint conference of the retirement research center consortium. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livermore G, Whalen D, & Stapleton DC (2011). Assessing the need for a National Disability Survey: Final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]