Abstract

Lung cancers bearing oncogenically-mutated EGFR represent a significant fraction of lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) for which EGFR-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) provide a highly effective therapeutic approach. However, these lung cancers eventually acquire resistance and undergo progression within a characteristically broad treatment duration range. Our previous study of EGFR mutant lung cancer patient biopsies highlighted the positive association of a TKI-induced interferon γ transcriptional response with increased time to treatment progression. To test the hypothesis that host immunity contributes to the TKI response, we developed novel genetically-engineered mouse models of EGFR mutant lung cancer bearing exon 19 deletions (del19) or the L860R missense mutation. Both oncogenic EGFR mouse models developed multifocal LUADs from which transplantable cancer cell lines sensitive to the EGFR-specific TKIs, gefitinib and osimertinib, were derived. When propagated orthotopically in the left lungs of syngeneic C57BL/6 mice, deep and durable shrinkage of the cell line-derived tumors was observed in response to daily treatment with osimertinib. By contrast, orthotopic tumors propagated in immune deficient nu/nu or Rag1−/− mice exhibited modest tumor shrinkage followed by rapid progression on continuous osimertinib treatment. Importantly, osimertinib treatment significantly increased intratumoral T cell content and decreased neutrophil content relative to diluent treatment. The findings provide strong evidence supporting the requirement for adaptive immunity in the durable therapeutic control of EGFR mutant lung cancer.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, EGFR, GEMM, adaptive immunity, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is mutated in 15–30% of lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) [[1–4] where the L858R missense mutations and in-frame exon 19 deletions account for ~85% of EGFR-activating mutations [3]. The EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) erlotinib was approved in 2004 for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients [5]. Subsequently, it was noted that novel EGFR mutations predicted patient sensitivity to erlotinib [6, 7], and EGFR-specific TKIs became first-line therapies for LUAD patients whose tumors harbor EGFR mutations [5, 8, 9]. To combat the EGFR-T790M mutation that arose as a resistance mechanism in the setting of 1st generation TKIs, a 3rd generation inhibitor, osimertinib, that inhibits oncogenic EGFR with or without the T790M mutation [10–12] was approved as the present first-line therapy for EGFR mutant LUAD. Despite these important advances in precision oncology for oncogenic EGFR-driven LUAD, the vast majority of patients will develop acquired resistance and eventually relapse [13, 14]. There is presently no FDA-approved therapy for patients progressing on osimertinib.

While oncogenic EGFR mutations predict responsiveness to EGFR-specific TKIs [6, 7, 15], patients display wide-ranging therapeutic responses with rare complete responses, but largely partial responses accompanied by residual disease [16, 17]. Thus, defining molecular mechanisms contributing to residual disease and variable duration of EGFR TKI therapeutic responses may provide opportunities for novel drug combinations to improve outcomes for this oncogene-defined group of patients. Based on their lack of response to immunotherapies and lower mutation burden, it is tempting to consider host immunity as irrelevant to EGFR-driven LUAD subsets and therapeutic response to TKI. However, we recently reported that the degree of induction of an interferon γ (IFNγ) transcriptional response in “on-treatment” biopsies obtained from EGFR mutant LUAD patients positively associated with the duration of the therapeutic response [18]. This same study and that of Maynard et al [19] provided evidence for increased tumoral content of T cells in response to TKI treatment, supporting a growing body of evidence that host immunity contributes to the therapeutic response to oncogene-targeted agents [20–28]. While human tumor specimens have provided important associations, relevant preclinical models are necessary to provide deeper mechanistic insight into tumor-immune cell interactions.

There are limited preclinical models available to explore how innate and adaptive immunity may contribute to the TKI response in EGFR-mutant lung tumors. Human patient-derived EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines provide models for assessing direct actions of TKIs on tumor cells, but in vivo studies require implantation into immune-deficient mice which lack T and B cells. Several groups have developed genetically-engineered mouse models (GEMMs) where human EGFR cDNAs bearing L858R or exon 19 deletions, in some instances bearing mutations inducing TKI resistance, are expressed in relevant lung cell types via tetracycline-inducible promoters to yield multi-focal lung tumors [29–34]. These models have provided clear evidence for the therapeutic activity of TKIs and antibody-based agents, but due to the selection of the tetracycline-inducible system, cultured cell lines have not been generated. In this study, we developed novel GEMMs whereby murine EGFR cDNAs encoding the two major oncogenic mutations are expressed following Cre recombinase-mediated excision of Lox-stop-Lox sequences, yielding multifocal lung tumors in mice. Our group has established an orthotopic model whereby murine lung cancer cells are implanted directly into the left lung of syngeneic mice, resulting in the development of a single tumor in the appropriate microenvironment complete with a fully-competent immune system [35–37]. This model is well suited for examining interactions between the cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment (TME), and has allowed us to define pathways in the cancer cells associated with response to immunotherapy [38, 39]. Using these oncogenic EGFR GEMMs, we have established transplantable murine lung cancer cell lines that yield orthotopic lung tumors suitable for assessing the role of host immunity in the therapeutic response to TKI. The results reveal that engagement of adaptive immunity is necessary for durable in vivo efficacy of osimertinib in these models of EGFR-mutant LUAD.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mouse Models of EGFR-Mutant LUAD:

The murine Egfr cDNA was amplified from reverse-transcribed mRNA isolated from the Lewis Lung Cancer (LLC) cell line with forward primer 5’-ACCGCTAGCGCCGCCACCATGCGACCCTCAGGGACCGC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-ACCAAGCTTTCATGCTCCAATAAACTCACT-3’. The bolded ATG and TCA represent the translation start and stop sites, respectively of murine Egfr. The purified 3600 bp amplicon was cloned into pcDNA3.1/Hygro (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and validated by Sanger sequencing. Murine Egfr cDNAs encoding the L860R mutation (equivalent to human L858R) and EGFR-ELREA (aa 748–752) deletion (del19) were generated by in vitro PCR-based mutagenesis. Egfr-transgenic mice (Rosa-LoxP-STOP-LoxP-EGFR-L860R/EGFR-del19-mC3-WPRE) were generated by the Mouse Genetics Core Facility at National Jewish Health (Denver, CO). Founding mice were subsequently bred with Trp53LoxP mice (B6.129P2-Trp53tm1Brn/J; Jackson Laboratory stock #008462). An adenovirus preparation (1010 PFU/ml) encoding Cre recombinase driven by the CMV promoter was purchased from Vector Biolabs (Malvern, PA; Cat. No. 1770). Intratracheal administration of Adeno-Cre virus (2.5 × 107 PFU/mouse) led to the development of multifocal tumors within 8 weeks (see below).

Genotyping:

DNA was isolated from mouse ear clips following the Extracta DNA Prep for PCR (Quantabio #95091) following the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR for the gene of interest was performed using the AccuStart II GelTrack PCR SuperMix protocol (Quantabio, #95136, Beverly, MA).

EGFR – Forward primer:

5’-AGTTGTTATCAGTAAGGGAGCTGCA-3’; Reverse primer: 5’-ACCGAAAATCTGTGGGAAGTCTTGT-3’; RS-CAG rev1 primer: 5’-CTCGACCATGGTAATAGCGATGAC-3’; PCR Program: 95°C 3 min, [95°C 30 sec, 58°C 30 sec, 72°C 40 sec] × 38 cycles, 72°C 3 min, 4°C 5 min.

TP53 [40] – Forward primer:

5’-GGTTAAACCCAGCTT GAC CA-3’; Reverse primer: 5’-GGAGGCAGAGACAGTTGGAG-3’; PCR Program: 94°C 1 min, [94°C 30sec, 60°C 30 sec, 72°C 1 min] × 35 cycles, 72°C 10 min, 4°C 5 min.

Generation and Maintenance of EGFR-Mutant Murine Lung Cancer Cell Lines:

To generate mEGFR-del19.1 and mEGFR-L860R.1 cells, lungs from AdCre-infected EGFR-transgenic mice were harvested and tumors minced, digested and cultured. For the generation of mEGFR-del19.2 cells, a tumor from an EGFR-transgenic mouse was minced into 1 mm3 pieces, dipped in Matrigel (Corning, #354234, Corning, NY), and implanted into the flanks of a nu/nu mouse. The resulting flank tumor was harvested, minced, digested and cultured on a plastic tissue culture dish in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. EGFR-mutant murine cell lines were passaged in culture until stable epithelial cell lines were established. The presence of the predicted EGFR mutation was verified by Sanger Sequencing of the EGFR-mutant transgene. Cells were cultured and maintained at 37°C in RPMI-1640 media (Corning) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Waltham, MA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were passaged for no more than 10 passages before a new vial of cells was thawed.

A cell line was established from a tumor derived from mEGFRdel19.1 cells that was propagated in a nu/nu mouse and treated chronically with osimertinib until progression occurred. The tumor was excised, minced and cultured in vitro in the presence of 200 nM osimertinib until a stable cell line (mEGFRdel19.1–616) was established. In parallel, mEGFRdel19.1 cells were passaged in vitro with increasing concentrations of osimertinib until a culture (mEGFRdel19.1 Osi-R) that grew in medium containing 1 μM osimertinib was obtained. Cells were also passaged for the same time period in medium with DMSO as a passage control.

In vivo Animal Studies:

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (#000664), and nu/nu mice (Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu; #069) were obtained from Envigo. Transgenic mice were developed at the Mouse Genetics Core at National Jewish Hospital. Experiments were performed on 8- to 12-week-old male and female mice that were bred (transgenic EGFR mice), housed, and maintained at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus vivarium, and all procedures and manipulations were performed under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Mice were sacrificed using CO2 and cervical dislocation as a secondary method.

Orthotopic Lung Model:

We have previously reported our orthotopic lung injection model [36, 37, 41]. Briefly, 5 × 105 murine EGFR-mutant lung cancer cells in 40 μL of 1.35 mg/mL Matrigel diluted in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Corning) were injected into the left lobe of the lungs of either C57BL/6 or nu/nu mice. For the injection, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, their left side was shaved, a 1 mm incision was made in the skin on their left side to visualize the ribs and the left lung, cells were injected using a 30-gauge needle, and the incision was closed with staples. Mice were imaged 7–10 days post injection for a baseline pre-treatment image, and then randomized into groups (n=10) treated with osimertinib (5 mg/kg; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ) or control (H2O) by oral gavage with a schedule of 5 days on treatment followed by 2 days off. For immunofluorescence experiments, tumors were allowed to establish for 3 weeks and then treated by oral gavage for 4 days with 5 mg/kg osimertinib or control. Mice were euthanized, tumors measured via digital calipers, and tissue was harvested (see below).

Xenograft Flank Model:

1 × 106 cells in 100uL of 1.35 mg/mL matrigel diluted in PBS were injected into each flank of nu/nu mice. When the tumors reached ~200mm3, mice were randomized to diluent control (H2O) or 5 mg/kg osimertinib delivered by daily oral gavage. Tumor volumes were measured every 3 days via digital calipers. Mice were euthanized when tumor size reached ~1000 mm3 per IACUC guidelines.

Micro-CT (μCT) Imaging:

μCT imaging was performed by the Small-Animal IGRT Core at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, CO using the X-Rad 225Cx Micro IGRT and SmART Systems (Precision X-Ray, Madison, CT). Tumor volume was quantified from μCT images using ITK-SNAP software [42] (www.itksnap.org).

Tissue Harvesting and Processing for Immunofluorescence:

For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, the lungs of mice were perfused with 5mL of PBS/heparin (20 U/mL; Sigma) and inflated with 4mL of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Scientific). The tumor-bearing left lung was fixed in 4% PFA for 24 hours, upon which it was switched to 70% ethanol. Tissues were processed and embedded into FFPE by the Pathology Shared Resource at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The Pathology Shared Resource cut blank slides performed hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E). Paraffin embedded samples were cut into 5 μm sections. Sections were dehydrated, immersed in 0.1% Sudan Black B (Sigma, #199664–25G) in 70% ethanol for 20 minutes, washed in TBST, incubated in citrate antigen retrieval solution at 100°C for 2 hours, washed in 0.1M glycine/TBST (Sigma, #G-8898) for 10 minutes, and placed in 10 mg/ml sodium borohydride in Hank’s buffer (Gibco, #14175–095). After blocking with 10% goat serum in equal parts of 5% BSA in TBST and Superblock (ScyTek Laboratories, #AAA999, Logan, UT) at 4°C overnight, sections were incubated with primary rabbit anti-CD3e (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific, #MA5–14524, Waltham, MA) and rat anti-CD8 (1:100; #4SM15, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in equal part solution of 5% BSA in TBST and Superblock for 1 hour at room temperature, washed in TBST, and incubated with secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Flour 488 (#A11034; Invitrogen) or goat anti-rat Alexafluor 594 (A11007; Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, #H-1200, Newark, CA). Triplicate high power fields (40X) derived from regions of interest within 3–4 independent tumors were analyzed with Cell Profiler 4.2.4 to perform image segmentation and identify individual nuclei and cells in each 40x image. Identified cells were exported to Cell Profiler Analyst 3.0.4 where RandomForest Classifier model was trained (classification accuracy> 80%) to identify CD3+ cells. CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD8- cells were further identified among the CD3+ cells using the same workflow. Quantified images were visually examined to exclude false positives.

Flow Cytometry:

Excised lungs were perfused with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/heparin solution, the left lung lobes bearing the tumors were mechanically dissociated using a razor blade and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C with 3.2mg/mL Collagenase Type 2 (Worthington, 43C14117B), 0.75 mg/ml Elastase (Worthington, 33S14652), 0.2 mg/ml Soybean Trypsin Inhibitor (Worthington, S9B11099N), and DNAse I 40 μg/ml (Sigma). The resulting single cell suspensions were filtered through 70μm strainers (BD Biosciences), washed with FA3 staining buffer (PBS containing 1% FBS, 2mM EDTA, 10mM HEPES). Samples underwent a red blood cell lysis step (0.15 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 7.2), were washed, and filtered through a 40 μm strainer (BD Biosciences). The single cell suspension samples were blocked in anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (clone 93; eBioscience) at 1:200 on a rocker for 15 min at 4°C. Next, fix viability dye (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit; 1:200; Invitrogen) and conjugated antibodies were added (see below) to the single cell suspension. Cells were incubated in the dark at 4°C for 60 minutes. Cells were then resuspended in FA3 buffer and ran on the Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). For compensation, single-stained beads (VersaComp Antibody Capture Bead Kit; Beckman Coulter) and a single-stained cell-mix of all samples analyzed were used. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using Kaluza Analysis Software (v2.0, Beckman Coulter) and the previously-published gating strategy [43]. Compensation was first performed on the single-stained bead controls and then confirmed using the single-stained cell mixture. Antibody Panel: CD11b-FITC (clone M1/70; 1:100; BioLegend), Ly6C-PerCP/Cy5.5 (clone HK1.4; 1:100; BioLegend), Ly6G-PE/Cy7 (clone 1A8; 1:200; BioLegend), SigF-A647 (clone E50–2440; 1:100; BD Biosciences), CD45-AF700 (clone 30-F11; 1:100; Invitrogen).

RNAseq:

Murine EGFR mutant cell lines cultured in 10 cm dishes were treated for 1–6 days with 0.1% DMSO or 100 nM osimertinib. RNA was submitted to the University of Colorado Cancer Center Genomics Shared Resource where libraries were generated and sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 to generate 2×151 bp reads. Fastq files were quality checked with FastQC, Illumina adapters trimmed with bbduk, and mapped to the mouse mm10 genome with STAR aligner. Counts were generated by STAR’s internal counter and reads were normalized to counts per million (CPM) using the edgeR R package (20). Heatmaps were generated in Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Immunoblotting:

Cells were collected in phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuged, and suspended in lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate (pH 7.2), 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.3 M NaCl, 2 μg/ml leupeptin and 4 μg/ml aprotinin). Aliquots of the cell lysates containing 50 μg of protein were submitted to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for proteins described in the legend to Figure 3.

Proliferation Assays

The murine EGFR mutant cell lines were plated at 100 cells per well in 96-well tissue culture plates. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated in triplicate with the indicated concentration of gefitinib or osimertinib. Cell number assessed by DNA content was determined after 7–10 days of culture using CyQUANT Direct Cell Proliferation Assay (Life Technologies, #C35011, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Data are presented as percent of control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO.

Statistics:

All graphing and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Transcriptional induction of gene signatures associated with immune engagement in biopsies from TKI-treated patients.

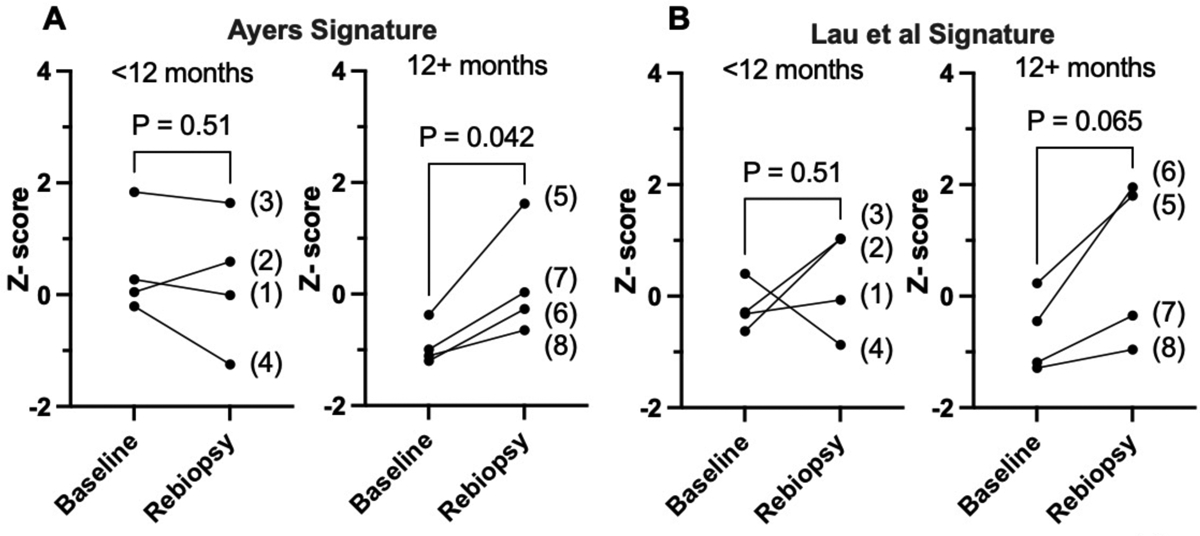

We previously performed RNAseq analysis on 8 pairs of patient-derived EGFR mutant lung tumor biopsy specimens obtained prior to and after ~2 weeks of treatment with an EGFR-specific TKI [18]. The findings revealed induction of multiple immune and inflammation-related pathways in “on-treatment” relative to pre-treatment biopsies, and the degree of induction of the IFNγ Hallmark pathway was positively associated with the time to progression (TTP) experienced by the patients. For this study, the RNAseq data were used to calculate scores from the T cell-inflamed gene expression profile reported by Ayers et al [44] as well as a cytotoxic T cell signature developed by Lau et al [45]. Both of these signatures serve as predictors of clinical response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. The findings show that the Ayers signature scores increased in all on-treatment biopsies from patients with TTP of greater than 12 months (p < 0.05 by paired t-test), but in only 1 of 4 patients with a TTP less than 12 months (Fig.1A). Similarly, the Lau et al signature (Fig. 1B) was increased in all four patients with TTP greater than 12 months and trended towards significance (p = 0.065). Thus, the duration of TKI response in this set of patients associated with induction of these gene signatures despite the fact that EGFR mutant lung cancers fail to exhibit significant response to anti-PD-1-based immune therapies [46–48]. We interpret the increased induction of the IFNγ Hallmark pathway as well as the Ayers and Lau signatures in Fig. 1 as evidence supporting the contribution of host immunity to the therapeutic response of human EGFR mutant lung cancer to TKIs. Definitively testing this hypothesis requires experiments with EGFR-driven murine lung cancer models in fully immune competent hosts.

Figure 1. Induction of T cell-focused gene expression signatures in on-treatment biopsies from EGFR mutant LUAD patients associates with greater time to progression.

Using previously reported RNAseq data from pre- and on-treatment biopsies collected from eight EGFR mutant LUAD patients under informed consent [18], the sums of the 18 genes in the signature described by (A) Ayers et al [44] and the 25 genes in the signature described by (B) Lau et al [45] were calculated for each patient-derived specimen and converted to Z-scores. The resulting values for the Ayers (A) and Lau et al (B) signatures were binned by the time to progression (TTP) values of less than or greater than 12 months where the eight patients (#’s 1–8) exhibited TTP of 6.2, 7, 7, 8.6 13, 13.1. 16 and 16.3 months, respectively (mean = 10.9, median = 10.8 months). The matched Z-scores for each patient at baseline and upon re-biopsy (patient IDs are in parentheses) are graphed and analyzed by paired t-tests. The p values for the two analyses are indicated.

Generation of mouse models that develop EGFR mutation-driven LUAD.

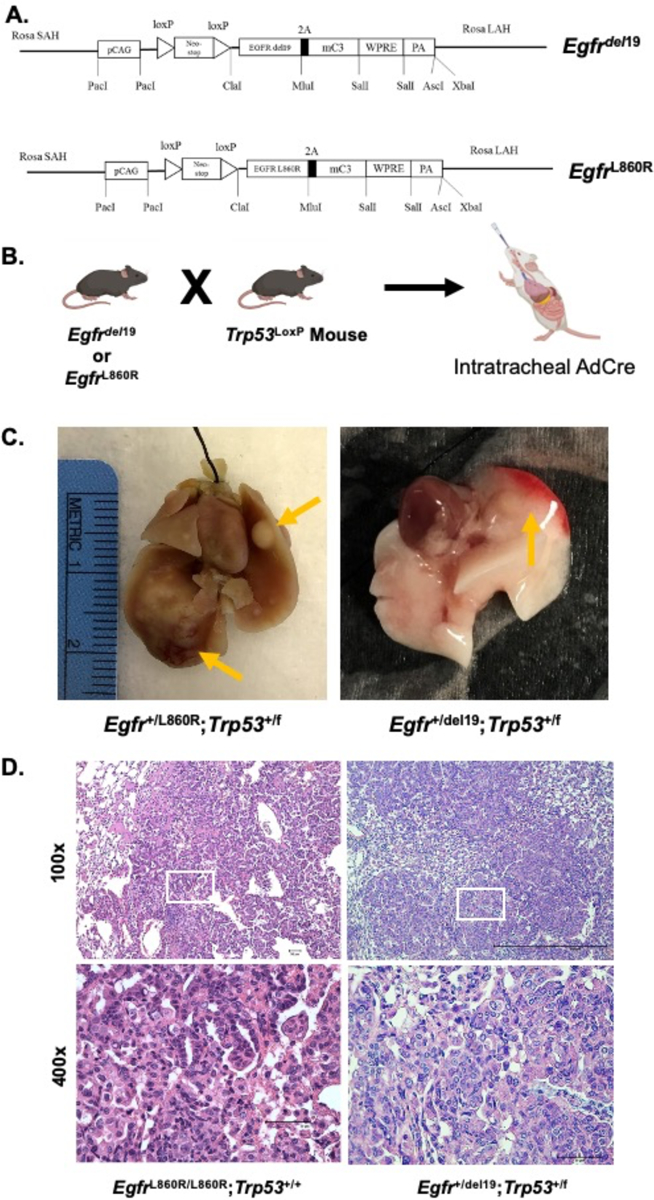

To provide preclinical models of EGFR-mutant LUAD from which murine LUAD cell lines could be established, novel EGFR-mutant GEMMs were developed. The murine Egfr cDNA was amplified from reverse-transcribed RNA prepared from murine Lewis Lung carcinoma (LLC) cells and the exon 19 deletion and L860R (equivalent to human EGFR L858R) mutations were generated by PCR-directed mutagenesis (see Materials and Methods). Transgenic mouse strains were generated whereby the Efgrdel19 or EgfrL860R transgenes were inserted into the Rosa locus controlled by a strong CAG promoter and a proximal LoxP-STOP-LoxP sequence (Fig. 2A). After interbreeding with Trp53LoxP mice (Fig. 2B), adeno-Cre virus preparations (AdCre) were administered intratracheally (see Materials and Methods) and 8–14 weeks later, multifocal lung adenocarcinomas developed with some mice exhibiting tumor formation as early as 4 weeks post AdCre injection (Suppl. Table S1). The tumors were readily visualized by gross inspection (Fig. 2C) and pathological analysis of H&E-stained sections identified hyperplasias, atypical adenomatous hyperplasias (AAH), adenomas, and adenocarcinomas (Fig. 2D and Suppl. Table S1). To test the dependency of the tumors arising in these models on EGFR signaling, an Efgrdel19 mouse intratracheally injected with AdCre was imaged 15 weeks post-injection by μCT, and then treated daily with osimertinib by oral gavage. Osimertinib treatment of the mouse for 3 weeks induced significant shrinkage of tumors detected by μCT (Suppl. Fig. S1A).

Figure 2. Transgenic mouse strains for Cre-mediated expression of Egfrdel19 and EgfrL860R.

Egfr-transgenic mice (Rosa-loxP-STOP-LoxP- EGFR L860R/del19-mC3-WPRE) were created by the Mouse Genetics Core at National Jewish Health. One strain expresses the murine Egfr cDNA encoding an exon 19 deletion and one with an L860R mutation (equivalent to the human L858R mutation). The resulting mice were bred with p53LoxP mice from Jackson Laboratories (B6.129P2-Trp53tm1Brn/J; #008462). To induce expression of the oncogenic EGFR transgene, an Adeno-Cre (AdCre) virus was instilled intratracheally (2.5×107 PFU/mouse) to excise the LoxP-STOP-LoxP sequence. (A) Schematic of the recombined Rosa locus and (B) breeding crosses. (C) Gross dissection of multifocal tumors in the right and left lungs resulting from AdCre instillation. Left panel: Egfr+/L860R;Trp53+/f lungs at 24 weeks post AdCre. Right panel: Egfr+/del19;Trp53+/f lungs at 11 weeks post AdCre. Arrows indicate visible tumors. (D) H&E-stained tumor sections showing adenocarcinoma of the lungs in this model resulting from AdCre installation. Left panels: an EgfrL860R/L860R;Trp53+/+ tumor at 14 weeks post AdCre. Right panels: an Egfr+/del19;Trp53+/f tumor at 8 weeks post AdCre. Images captured at 100x and 400x. The white boxes in the 100X images indicate positions of the 400x images.

Generation of murine EGFR-mutant lung cancer cell lines.

To generate cell lines from lung tumors that arise in the Efgrdel19 and EgfrL860R GEMMs, individual tumors were dissected from the lungs of mice previously injected with AdCre, dissociated into single cell suspensions and cultured until stable cell lines were established. Two cell lines were generated by direct propagation on tissue culture plastic, mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFR-L860R.1 (Suppl. Fig. S2A). For a third cell line (mEGFRdel19.2), a primary tumor was minced and implanted in the flank of a nu/nu mouse. The resulting flank tumor was harvested, dissociated, and cultured on plastic until a cell line was established (Suppl. Fig. S2A). The transgene construct also encodes cerulean blue, and fluorescence microscopy confirmed expression of this gene in mEGFRdel19.2 cells (Suppl. Fig. S2B). Expression of the oncogenic EGFR cDNAs was confirmed in all cell lines by direct Sanger sequencing (Suppl. Fig. S2C). The three murine EGFR cell lines were confirmed to be p53-null as assessed by immunoblot analysis, including mEGFRdel19.1 which was established from a p53+/f mouse (Suppl. Fig. S2D).

In vitro and in vivo sensitivity of murine EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines to TKIs.

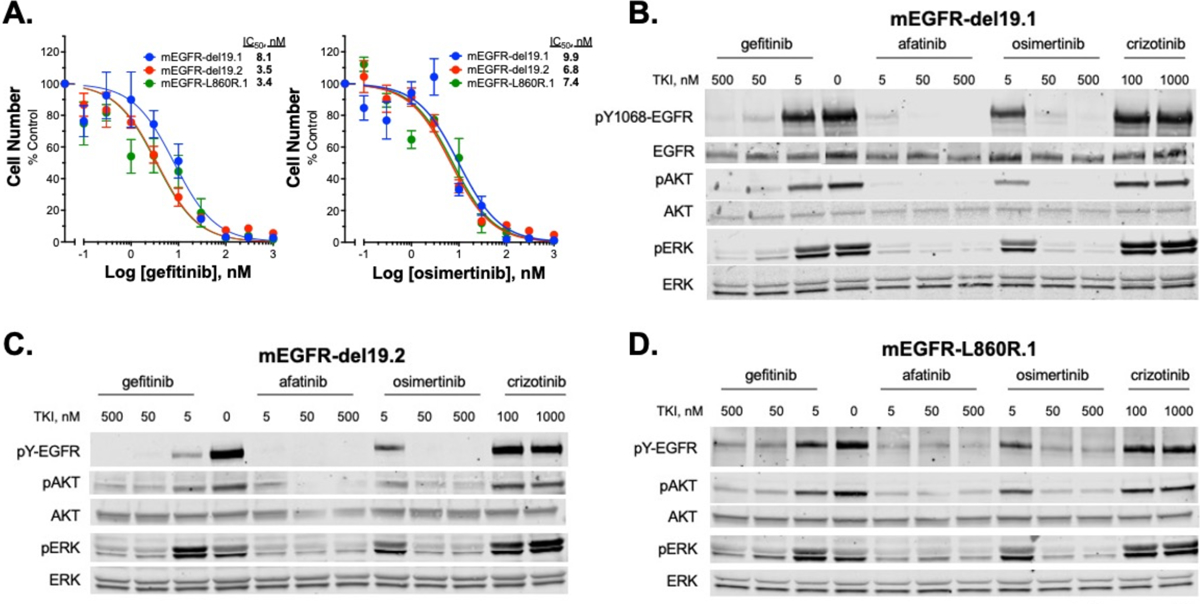

The growth and MAPK signaling dependency of the murine cell lines on mutant EGFR was tested in vitro. Measurement of cell growth in the presence of increasing concentrations of gefitinib and osimertinib revealed similar dose-dependent growth inhibition in the three cell lines with IC50 values in the 3–10 nM range for both drugs (Fig. 3A). Treatment of the cell lines with EGFR-targeting TKIs (gefitinib, afatinib, osimertinib) but not the ALK/MET-targeting TKI, crizotinib inhibited phospho-Y1068 content of EGFR as well as levels of pS483-AKT, and pThr202/Tyr204-ERK1/2 (Fig. 3B–D). The findings demonstrate that the murine EGFR lung cancer cell lines are dependent on oncogenic EGFR for growth as well as MAPK and AKT signaling.

Figure 3. Murine EGFR-mutant LUAD cell lines are responsive to EGFR inhibitors in vitro.

(A) The three EGFR-mutant murine cell lines were treated for 10 days with increasing concentrations of EGFR-specific TKIs, gefitinib or osimertinib and cell number was quantified with CyQUANT reagent. IC50 values were calculated with Prism 9 and presented in the graph. The data shown are the means of two independent experiments, each performed with technical triplicates. (B-D) The murine EGFR mutant cell lines were treated (2 hrs) with the indicated EGFR targeting TKIs (gefitinib, afatinib, osimertinib) as well as the ALK/MET-targeting TKI, crizotinib as a negative control. Cell lysates were submitted to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phospho-Y1068 and total EGFR, phospho-S483 and total AKT, and phospho-Thr202/Tyr204 and total ERK.

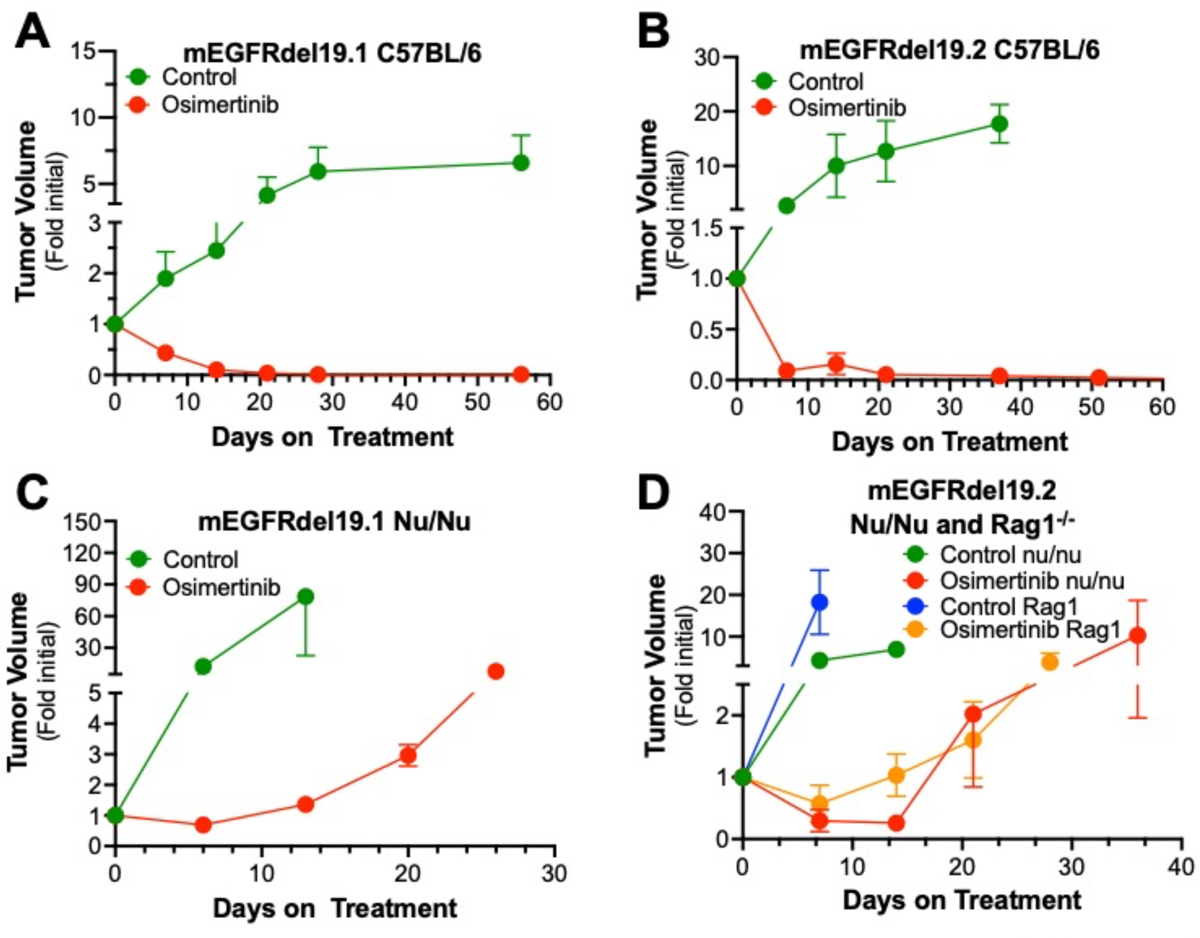

An orthotopic mouse model of lung cancer whereby murine lung cancer cells are directly inoculated into the left lobe of C57BL/6 mice [[36, 37, 41] was deployed to assess the therapeutic response of these murine EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines in the context of an immune-competent TME. Both mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2 readily formed lung tumors in C57BL/6 mice upon direct inoculation into the lung and H&E-stained sections of representative tumors are shown in Supp. Fig. S1B. By contrast, the frequency of tumor formation with mEGFR-L860R.1 cells was low with evidence of spontaneous regression in some instances. For this reason, in vivo evaluation of osimertinib responses will focus on mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2 cells. When mice bearing orthotopic mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2 tumors were submitted to daily treatment with osimertinib (5 mg/kg by oral gavage) starting 10 days after implantation, both models underwent prompt and marked tumor shrinkage (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, the TKI responses were durable with no evidence of tumor progression over the ~50-day course of osimertinib treatment.

Figure 4. Therapeutic response of orthotopic murine EGFR tumors to osimertinib in immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice.

Murine EGFRdel19.1 and del19.2 cells (500,000 cells/mouse) were injected into the left lungs of syngeneic C57BL/6 (A, B) or nu/nu (C) or nu/nu and Rag1−/− (D) mice. After 10 days, the mice were imaged by μCT to generate pre-treatment tumor volumes and randomized into osimertinib (5 mg/kg) or control treatment groups. The tumor-bearing mice were submitted to weekly μCT scans and the data are presented as fold of the initial pre-treatment volumes (means and SEM). For the C57BL/6 experiments, the initial tumor volumes (mean ± SEM) for the diluent and osimertinib-treated groups were 19.9 ± 4.4 mm3 (n=14) and 13.5 ± 2.8 mm3 (n=14) and 11.9 ± 4.5 mm3 (n=8) and 11.6 ± 3.0 mm3 (n=9) for mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2, respectively. For the Nu/Nu experiments, the initial tumor volumes for the diluent and osimertinib-treated groups were 2.9 ± 0.7 mm3 (n=6) and 9.0 ± 1.6 mm3 (n=9) and 21.7 ± 6.5 mm3 (n=6) and 13.6 ± 4.0 mm3 (n=9) for mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2, respectively. For the mEGFRdel19.2 experiment in Rag1−/− mice, the initial tumor volumes for the control and osimertinib-treated groups were 3.8 ± 1.5 mm3 (n=5) and 7.0 ± 2.5 mm3 (n=6), respectively.

To test the response of the murine EGFR models to PD-1 inhibitors, the response of mEGFRdel19.2-derived orthotopic tumors to twice weekly administered anti-PD-1 was determined. As shown in Suppl. Fig. S3, this immune checkpoint inhibitor had no effect on the growth of orthotopic mEGFRdel19.2 tumors compared to control IgG, similar to the general lack of response to human EGFR mutant lung cancers to immunotherapy.

Evidence for an adaptive immunity requirement for durable osimertinib responses.

Our recent studies with human EGFR mutant lung tumor biopsies (see [18] and Fig. 1A and B) suggest a role for host immunity in the therapeutic response to EGFR-targeting TKIs. To directly test the role for adaptive immunity, orthotopic tumors were established with mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2 cells in nu/nu mice which lack functional T cells. As shown in Figure 4C and D, osimertinib treatment induced tumor shrinkage to ~70 and 25% of initial volume in mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2, respectively. In contrast to the stable therapeutic response observed in tumors propagated in C57BL/6 mice, tumor progression was observed within ~2–3 weeks despite continuous treatment with osimertinib (Fig. 4C and D). In addition, mEGFRdel19.2-derived tumors were established in the distinct immune-deficient Rag1−/− mouse model; transient tumor shrinkage followed by prompt progression with continuous osimertinib treatment was observed similar to nu/nu mice (Fig. 4D). Of note, propagation of human H1650 cells bearing an EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation as a flank xenograft in nu/nu mice revealed similar kinetics of initial tumor shrinkage and progression upon treatment with continuous osimertinib (Suppl. Fig. S4). These data support a role for adaptive immune cells that are lacking in nu/nu and Rag1−/− mice in the durability of the in vivo TKI response in murine models driven by oncogenic EGFR.

To explore if the mEGFRdel19 tumors that progress on continuous osimertinib treatment represented TKI-resistant variants, we established a cell line from a mEGFRdel19.1 tumor propagated in nu/nu mice referred to as mEGFRdel19.1–616 that could be cultured in 200 nM osimertinib, demonstrating it had acquired TKI resistance (see Materials and Methods). In addition, mEGFRdel19.1 cells were cultured in vitro with escalating doses of osimertinib, yielding a culture that proliferated in the presence of 1 μM osimertinib (mEGFRdel19.1 Osi-R). Both cell lines and a passage control culture were submitted to RNAseq and analysis of the datasets revealed 2–3-fold induction of MET mRNA as well as pronounced induction of HGF mRNA relative to control mEGFRdel19.1 cells (Suppl. Fig. S5A). Both cultures were fully resistant to osimertinib up to 300 nM TKI, but exhibited acquired sensitivity to the MET inhibitor, crizotinib (Suppl. Fig. S5B). Thus, the progression of mEGFRdel19.1 orthotopic tumor growth in immune-deficient hosts under continuous osimertinib treatment appears to be driven by an HGF-MET bypass signaling pathway.

Analysis of the immune microenvironment in murine mEGFRdel19 tumors.

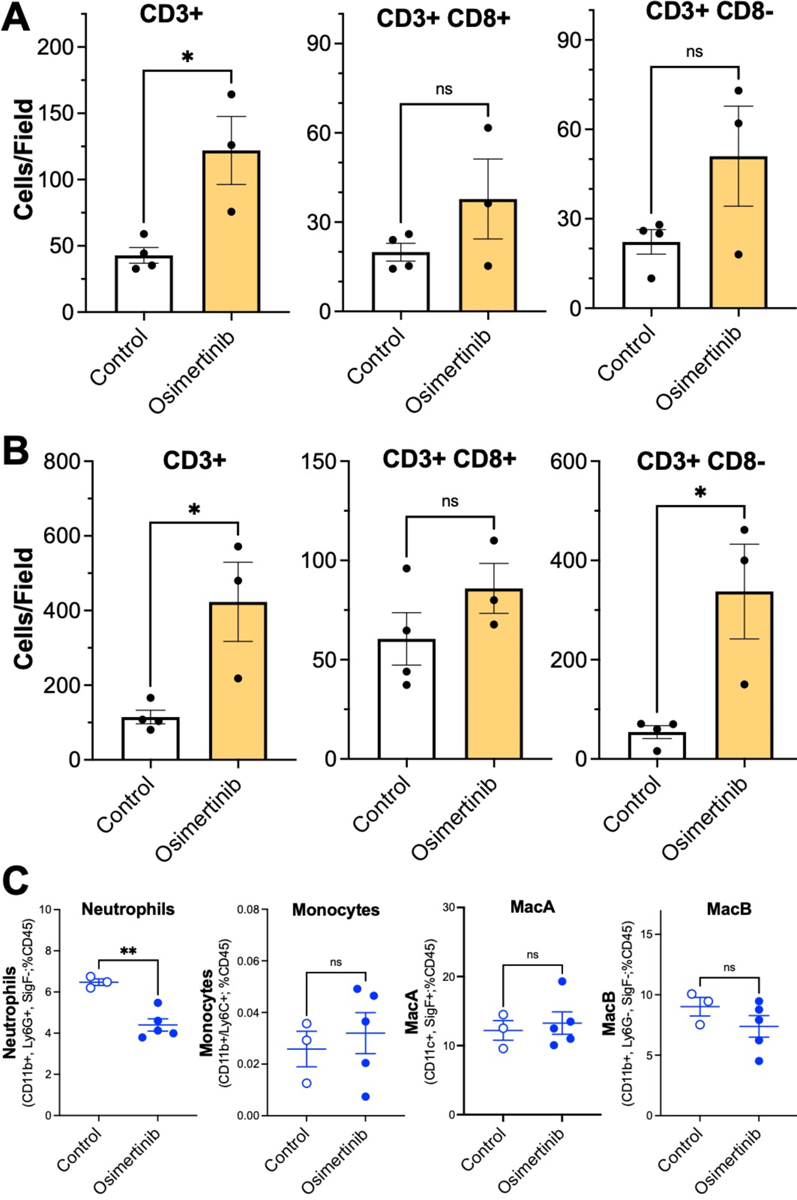

The findings in Fig. 4C and D support a role for the tumor microenvironment in contributing to the TKI therapeutic response. To analyze the immune cell populations in control and osimertinib-treated tumors, a combination of immunofluorescence and flow cytometry was deployed. The mEGFRdel19.1 and mEGFRdel19.2 cells were implanted into C57BL/6 mice and allowed to establish for ~3 weeks and then treated for 4 days with control or 5 mg/kg osimertinib. The left tumor-bearing lungs were harvested, formalin-fixed and submitted to immunofluorescence staining with anti-CD3 and anti-CD8 antibodies (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Figure 5A and B, the number of CD3+ cells was significantly increased with osimertinib treatment in both murine EGFR models. When the T cell populations were defined by CD3+/CD8+ and CD3+/CD8-, potentially identifying CD4+ T cells, the findings reveal statistically-significant increases in CD3+/CD8- content in osimertinib-treated mEGFRdel19.2 tumors. The osimertinib-treated mEGFRdel19.1 tumors exhibited increases in CD3+/CD8- cells that was not statistically significant. By contrast, CD3+/CD8+ T cells did not show significantly increased content with osimertinib treatment in either tumor model. To identify potential changes in myeloid cell types, mEGFRdel19.1 tumor-bearing lungs were dissociated and submitted to flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 5C). The findings reveal significantly decreased neutrophil content upon osimertinib treatment, but no significant changes in monocytes, resident alveolar macrophages (MacA) or recruited macrophage populations (MacB).

Figure 5. Osimertinib-treatment increases T cell content in orthotopic murine EGFRdel19 tumors.

Murine EGFRdel19.1 (A and C) and 19.2 (B) cells were injected into C57BL/6 mice, tumors were permitted to establish for 14–21 days and then the mice were treated for 4 days with diluent or osimertinib. In A and B, lungs were harvested, inflated with formalin, paraffin-embedded and 5 μm sections were submitted to immunofluorescence staining with anti-CD3 and anti-CD8 antibodies (see Materials and Methods). Total CD3+ cells as well as CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD8- cells were quantified in 3 distinct fields for each tumor with Cell Profiler 4.2.4 and the resulting values were averaged. The data in A and B are the means and SEM of 4 and 3 independent tumors for control and osimertinib-treated tumors, respectively, and were analyzed by student’s two-way t-tests. (C) Single-cell suspensions were generated from the left mEGFRdel19.1 tumor-bearing lungs and submitted to flow cytometry analysis for innate immune cells using the previously described gating strategy for neutrophils, monocytes and MacA and MacB macrophages [56]. Differences between groups was analyzed with two-way T tests. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM where ** indicates p-value less than 0.01; ns indicates not significant.

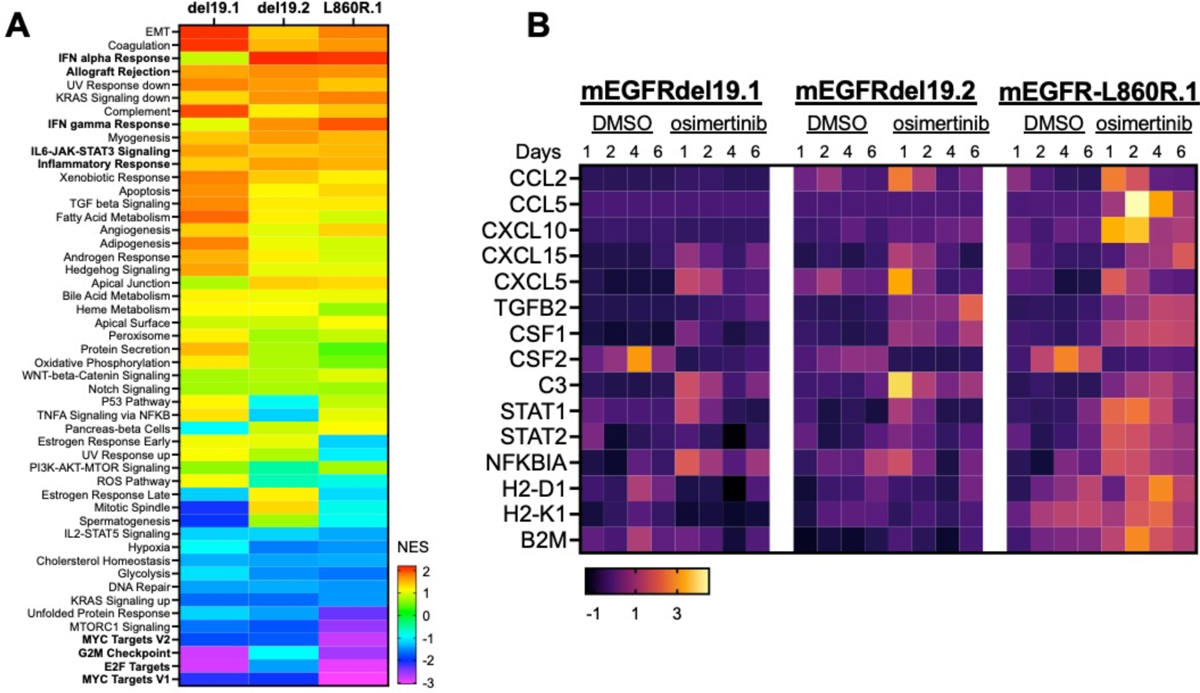

Osimertinib induces inflammation-related Hallmark pathways and expression of distinct chemokines.

Our recent studies in human EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines and both human and murine head and neck cancer cells demonstrate TKI-stimulated IFNγ transcriptional responses accompanied by increased chemokine expression [18, 49]. The three murine EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines were treated in vitro with osimertinib or DMSO and RNAseq was performed (see Materials and Methods). The resulting datasets were submitted to gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the Hallmark Pathways and the normalized enrichment scores (NES) are presented as a heatmap in Fig. 6A. The data reveal the induction of multiple inflammation-related Hallmark pathways in osimertinib-treated cells. Predictably, Hallmark pathways associated with cell proliferation (MYC targets V1 and V2, G2M checkpoint, E2F targets) were de-enriched in the TKI-treated cells. Using the RNAseq datasets, various genes encoding chemokines, cytokines and antigen-presentation machinery were interrogated as well as STAT1, STAT2 and NFKBIA, a transcriptional target of the NF κB pathway. The findings are presented as a heatmap in Fig. 6B and reveal marked, yet varied, regulation of chemokine and cytokine gene expression as well as putative proximally-acting transcription factor pathways (STAT1, IRF7, NFKBIA). The antigen-presentation genes (H2-D1, H2-K1 and B2M) were not significantly regulated in mEGFRdel19.1 and 19.2 cells, but exhibited osimertinib-dependent induction in mEGFR-L860R.1 cells.

Figure 6. Transcriptional regulation of inflammation-related Hallmark pathways and chemokines and cytokines in response to osimertinib treatment.

The murine EGFR mutant cell lines were treated in vitro for 1 to 6 days with DMSO or osimertinib (100 nM) and RNA was purified and sequenced. (A) For this analysis, the different time points were considered as replicates (n=4) and DMSO vs. alectinib-treated samples analyzed with GSEA using the Hallmark Pathways. The heatmap presents the normalized enrichment scores (NES) in the osimertinib-treated samples (see color bar for relative scores). (B) The RNA expression values for the selected genes were converted to Z-scores and presented in a heatmap format.

Discussion

Herein, we report the development and validation of novel EGFR mutant mouse models that recapitulate key features of human EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, we isolated and characterized three novel murine EGFR mutant lung cancer cell lines. Combined, these GEMMs and cell lines will be valuable for dissecting the contribution of the lung TME and host immunity to therapeutic responses to TKIs that cannot be assessed with human EGFR mutant cell lines propagated in immunodeficient mice. Coupled with our orthotopic model, we were able to assess tumor shrinkage and progression in mice with intact immune systems and a lung-specific microenvironment. We were able to track individually-implanted tumors via μCT imaging to assess their dynamic responses to the 3rd generation EGFR inhibitor, osimertinib. In future studies, it will be possible to molecularly engineer these cell lines through gene transfer-mediated overexpression or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout to test specific cancer cell-derived signal pathways for roles in cancer cell-TME cross-talk and therapeutic response. For example, if the TKI-induced inflammatory transcriptional responses dictate immune cell engagement, molecular manipulation of distinct chemokine and cytokine expression pathways that have been shown to recruit specific immune cell types would be predicted to alter TKI responsiveness through changes in the baseline and therapy-induced immune microenvironments.

Using these murine EGFR mutant cell lines, we present evidence for adaptive immunity as a requirement for durable inhibition of orthotopic tumors by osimertinib (Fig. 4). In this regard, our present study adds to a growing body of evidence supporting host immunity as a contributor to therapeutic efficacy of oncogene-targeted agents [20–27, 50]. We previously reported that the degree of induction of the IFNγ Hallmark response as well as a T cell signature [51] in on-treatment biopsies associate with the duration of therapeutic benefit in patients bearing EGFR mutant lung cancers [18]. Herein, we demonstrate that the magnitude of two additional gene expression signatures previously shown to predict responsiveness to anti-PD-1-based immune therapy [44, 45] also associate with longer time to progression on EGFR TKIs (Fig. 1). Thus, there is ample evidence for immune engagement by human EGFR mutant lung cancers despite their lack of sensitivity to anti-PD-1 therapies [46–48], a feature that is shared by orthotopic tumors derived from the murine EGFR mutant cell lines (Suppl. Fig. S3). While the aforementioned evidence for immune cell engagement by EGFR mutant lung cancers provides rationale for combining EGFR-specific TKIs and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, clinical trials testing these combinations were terminated early due to toxicities [52, 53]. In sum, the published and present findings suggest that host immunity is critical for durability of TKI response, but perhaps is regulated in a manner distinct from that associated with response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. A recent study by Tang et al [25] exploring sensitivity to SHP2 inhibitors revealed a dominant role for immunosuppressive myeloid cell types. Blockade of myeloid cell recruitment by CXCR1/2 inhibitors markedly enhanced T cell function and overall therapeutic response. Moreover, a study by Maynard et al demonstrated accumulation of immune suppressive cell types after longer times of TKI treatment in EGFR and ALK-driven lung tumors [[19]. Thus, alternative means to boost cytotoxic T cell activity besides anti-PD-1 agents may be required to enhance the contribution of adaptive immunity to TKI responsiveness in EGFR mutant lung cancers. These transplantable murine EGFR cell lines should prove invaluable for a deeper interrogation of the immune microenvironment in this oncogene-defined LUAD subset with the goal of identifying a novel combination therapy that bolsters adaptive immunity in conjunction with EGFR-specific TKIs to prolong the duration of therapeutic benefit presently experienced by patients.

A simple interpretation of the rapid progression of murine EGFR mutant tumors propagated in the absence of functional adaptive immunity (Fig. 4C, D) is that immune surveillance by specific T cell and/or B cell populations serves as a break on tumor progression driven by acquired resistance in the setting of TKI treatment. Thus, variation in the efficacy of immune surveillance amongst EGFR mutant lung cancer patients may account for the observed range in time to progression. It is interesting to consider the mutational and/or differentiation status of the murine EGFR mutant tumors that rapidly emerge in nu/nu and Rag1−/− mice. The spectrum of EGFR kinase domain mutations that confer osimertinib resistance has been defined in human EGFR mutant LUAD [13, 14], but the rapidity with which the emergence of resistance occurs seems more consistent with transcription-dependent phenotype switching [54] or engagement of bypass signaling pathways. RNAseq analysis of a mEGFRdel19.1-derived cell line that was established from a mEGFRdel19.1 tumor that progressed in an osimertinib-treated nu/nu mouse as well as osimertinib-resistant cells generated in vitro reveals induction of both MET and its ligand, HGF (Suppl. Fig. S5). This finding was accompanied by acquired sensitivity of the osimertinib-resistant cell lines to the MET inhibitor, crizotinib. It remains unclear how the lack of adaptive immunity permits this previously-defined bypass signaling pathway to be functionally unleashed. It is possible that initial shrinkage of the tumors with TKI treatment alters the balance between T cells and cancer cells as proposed in the immunoediting model of cancer [55] and prevents the ability of residual cancer cells undergoing bypass signaling to proliferate. Future studies will be directed at characterizing the progressing tumors in the immunodeficient hosts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Jennifer Matsuda and the Mouse Genetics Core at National Jewish Health for generating the murine EGFRdel19 and EGFRL860R GEMMs. The RNA sequencing was performed by the Genomics shared resource within the University of Colorado Cancer Center.

Funding

This research was supported by the Department of Defense Lung Cancer Research Program award W81XWH1910220 (LEH and RAN), the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Thoracic Oncology Research Initiative and the University of Colorado Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA046934.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures

None of the authors have disclosures to report.

Availability of Data

The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in GEO Datasets (GSE217405).

References

- [1].Fois SS, Paliogiannis P, Zinellu A, Fois AG, Cossu A, Palmieri G, Molecular Epidemiology of the Main Druggable Genetic Alterations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Int J Mol Sci, 22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Graham RP, Treece AL, Lindeman NI, Vasalos P, Shan M, Jennings LJ, Rimm DL, Worldwide Frequency of Commonly Detected EGFR Mutations, Arch Pathol Lab Med, 142 (2018) 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harrison PT, Vyse S, Huang PH, Rare epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung cancer, Semin Cancer Biol, 61 (2020) 167–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang YL, Yuan JQ, Wang KF, Fu XH, Han XR, Threapleton D, Yang ZY, Mao C, Tang JL, The prevalence of EGFR mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 78985–78993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cohen MH, Johnson JR, Chen YF, Sridhara R, Pazdur R, FDA drug approval summary: erlotinib (Tarceva) tablets, Oncologist, 10 (2005) 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, Naoki K, Sasaki H, Fujii Y, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Johnson BE, Meyerson M, EGFR Mutations in Lung Cancer: Correlation with Clinical Response to Gefitinib Therapy, Science, 304 (2004) 1497–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L, Mardis E, Kupfer D, Wilson R, Kris M, Varmus H, EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101 (2004) 13306–13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu J, Yang H, Jin B, Lou Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhong H, Wang H, Wu D, Han B, Corrigendum: EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients with the L858R point mutation, Sci Rep, 6 (2016) 38270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Huang X, Kang S, Chen G, Wu M, Miao S, Huang Y, Zhao H, Zhang L, Therapeutic Efficacy Comparison of 5 Major EGFR-TKIs in Advanced EGFR-positive Non-Small-cell Lung Cancer: A Network Meta-analysis Based on Head-to-Head Trials, Clin Lung Cancer, 18 (2017) e333–e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, Orme JP, Finlay MR, Ward RA, Mellor MJ, Hughes G, Rahi A, Jacobs VN, Red Brewer M, Ichihara E, Sun J, Jin H, Ballard P, Al-Kadhimi K, Rowlinson R, Klinowska T, Richmond GH, Cantarini M, Kim DW, Ranson MR, Pao W, AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer, Cancer discovery, 4 (2014) 1046–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Finlay MR, Anderton M, Ashton S, Ballard P, Bethel PA, Box MR, Bradbury RH, Brown SJ, Butterworth S, Campbell A, Chorley C, Colclough N, Cross DA, Currie GS, Grist M, Hassall L, Hill GB, James D, James M, Kemmitt P, Klinowska T, Lamont G, Lamont SG, Martin N, McFarland HL, Mellor MJ, Orme JP, Perkins D, Perkins P, Richmond G, Smith P, Ward RA, Waring MJ, Whittaker D, Wells S, Wrigley GL, Discovery of a potent and selective EGFR inhibitor (AZD9291) of both sensitizing and T790M resistance mutations that spares the wild type form of the receptor, Journal of medicinal chemistry, 57 (2014) 8249–8267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, Dechaphunkul A, Imamura F, Nogami N, Kurata T, Okamoto I, Zhou C, Cho BC, Cheng Y, Cho EK, Voon PJ, Planchard D, Su WC, Gray JE, Lee SM, Hodge R, Marotti M, Rukazenkov Y, Ramalingam SS, Investigators F, Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer, N Engl J Med, 378 (2018) 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cooper AJ, Sequist LV, Lin JJ, Third-generation EGFR and ALK inhibitors: mechanisms of resistance and management, Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 19 (2022) 499–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Koulouris A, Tsagkaris C, Corriero AC, Metro G, Mountzios G, Resistance to TKIs in EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: From Mechanisms to New Therapeutic Strategies, Cancers (Basel), 14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, Louis DN, Christiani DC, Settleman J, Haber DA, Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib, N Engl J Med, 350 (2004) 2129–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bivona TG, Doebele RC, A framework for understanding and targeting residual disease in oncogene-driven solid cancers, Nat Med, 22 (2016) 472–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Janne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, Planchard D, Ohe Y, Ramalingam SS, Ahn MJ, Kim SW, Su WC, Horn L, Haggstrom D, Felip E, Kim JH, Frewer P, Cantarini M, Brown KH, Dickinson PA, Ghiorghiu S, Ranson M, AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer, N Engl J Med, 372 (2015) 1689–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gurule NJ, McCoach CE, Hinz TK, Merrick DT, Van Bokhoven A, Kim J, Patil T, Calhoun J, Nemenoff RA, Tan AC, Doebele RC, Heasley LE, A tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced interferon response positively associates with clinical response in EGFR-mutant lung cancer, NPJ Precis Oncol, 5 (2021) 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Maynard A, McCoach CE, Rotow JK, Harris L, Haderk F, Kerr DL, Yu EA, Schenk EL, Tan W, Zee A, Tan M, Gui P, Lea T, Wu W, Urisman A, Jones K, Sit R, Kolli PK, Seeley E, Gesthalter Y, Le DD, Yamauchi KA, Naeger DM, Bandyopadhyay S, Shah K, Cech L, Thomas NJ, Gupta A, Gonzalez M, Do H, Tan L, Bacaltos B, Gomez-Sjoberg R, Gubens M, Jahan T, Kratz JR, Jablons D, Neff N, Doebele RC, Weissman J, Blakely CM, Darmanis S, Bivona TG, Therapy-Induced Evolution of Human Lung Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing, Cell, 182 (2020) 1232–1251 e1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gurule NJ, McCoach C, Hinz TK, Marek L, Ryall K, Korpela S, Sisler D, Tan AC, Doebele RC, Heasley LE, Oncogene-targeted agents induce an interferon response in EGFR and EML4-ALK driven lung cancer., Keystone Symposium on Cancer Immunotherapy: Combinations 2018., (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sisler DJ, Heasley LE, Therapeutic opportunity in innate immune response induction by oncogene-targeted drugs, Future Med Chem, 11 (2019) 1083–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ruscetti M, Leibold J, Bott MJ, Fennell M, Kulick A, Salgado NR, Chen CC, Ho YJ, Sanchez-Rivera FJ, Feucht J, Baslan T, Tian S, Chen HA, Romesser PB, Poirier JT, Rudin CM, de Stanchina E, Manchado E, Sherr CJ, Lowe SW, NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity contributes to tumor control by a cytostatic drug combination, Science, 362 (2018) 1416–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Petroni G, Buque A, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Immunomodulation by targeted anticancer agents, Cancer cell, 39 (2021) 310–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Uzhachenko RV, Bharti V, Ouyang Z, Blevins A, Mont S, Saleh N, Lawrence HA, Shen C, Chen SC, Ayers GD, DeNardo DG, Arteaga C, Richmond A, Vilgelm AE, Metabolic modulation by CDK4/6 inhibitor promotes chemokine-mediated recruitment of T cells into mammary tumors, Cell reports, 35 (2021) 109271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tang KH, Li S, Khodadadi-Jamayran A, Jen J, Han H, Guidry K, Chen T, Hao Y, Fedele C, Zebala JA, Maeda DY, Christensen JG, Olson P, Athanas A, Loomis CA, Tsirigos A, Wong KK, Neel BG, Combined Inhibition of SHP2 and CXCR1/2 Promotes Antitumor T-cell Response in NSCLC, Cancer discovery, 12 (2022) 47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, Gaida K, Holt T, Knutson CG, Koppada N, Lanman BA, Werner J, Rapaport AS, San Miguel T, Ortiz R, Osgood T, Sun JR, Zhu X, McCarter JD, Volak LP, Houk BE, Fakih MG, O’Neil BH, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Desai J, Kuo J, Govindan R, Hong DS, Ouyang W, Henary H, Arvedson T, Cee VJ, Lipford JR, The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity, Nature, 575 (2019) 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Petrazzuolo A, Perez-Lanzon M, Martins I, Liu P, Kepp O, Minard-Colin V, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G, Pharmacological inhibitors of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) induce immunogenic cell death through on-target effects, Cell Death Dis, 12 (2021) 713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kumagai S, Koyama S, Nishikawa H, Antitumour immunity regulated by aberrant ERBB family signalling, Nat Rev Cancer, 21 (2021) 181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kwon MC, Berns A, Mouse models for lung cancer, Mol Oncol, 7 (2013) 165–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McFadden DG, Politi K, Bhutkar A, Chen FK, Song X, Pirun M, Santiago PM, Kim-Kiselak C, Platt JT, Lee E, Hodges E, Rosebrock AP, Bronson RT, Socci ND, Hannon GJ, Jacks T, Varmus H, Mutational landscape of EGFR-, MYC-, and Kras-driven genetically engineered mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113 (2016) E6409–E6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Politi K, Fan PD, Shen R, Zakowski M, Varmus H, Erlotinib resistance in mouse models of epidermal growth factor receptor-induced lung adenocarcinoma, Dis Model Mech, 3 (2010) 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Politi K, Zakowski MF, Fan PD, Schonfeld EA, Pao W, Varmus HE, Lung adenocarcinomas induced in mice by mutant EGF receptors foundin human lung cancers respondto a tyrosine kinase inhibitor orto down-regulation of the receptors, Genes Dev, (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Regales L, Balak MN, Gong Y, Politi K, Sawai A, Le C, Koutcher JA, Solit DB, Rosen N, Zakowski MF, Pao W, Development of new mouse lung tumor models expressing EGFR T790M mutants associated with clinical resistance to kinase inhibitors, PloS one, 2 (2007) e810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim DS, Ji W, Kim DH, Choi YJ, Im K, Lee CW, Cho J, Min J, Woo DC, Choi CM, Lee JC, Sung YH, Rho JK, Generation of genetically engineered mice for lung cancer with mutant EGFR, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 632 (2022) 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li HY, McSharry M, Walker D, Johnson A, Kwak J, Bullock B, Neuwelt A, Poczobutt JM, Sippel TR, Keith RL, Weiser-Evans MCM, Clambey E, Nemenoff RA, Targeted overexpression of prostacyclin synthase inhibits lung tumor progression by recruiting CD4+ T lymphocytes in tumors that express MHC class II, Oncoimmunology, 7 (2018) e1423182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sippel TR, Johnson AM, Li HY, Hanson D, Nguyen TT, Bullock BL, Poczobutt JM, Kwak JW, Kleczko EK, Weiser-Evans MC, Nemenoff RA, Activation of PPARgamma in Myeloid Cells Promotes Progression of Epithelial Lung Tumors through TGFbeta1, Molecular cancer research : MCR, 17 (2019) 1748–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weiser-Evans MC, Wang XQ, Amin J, Van Putten V, Choudhary R, Winn RA, Scheinman R, Simpson P, Geraci MW, Nemenoff RA, Depletion of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in bone marrow-derived macrophages protects against lung cancer progression and metastasis, Cancer research, 69 (2009) 1733–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bullock BL, Kimball AK, Poczobutt JM, Neuwelt AJ, Li HY, Johnson AM, Kwak JW, Kleczko EK, Kaspar RE, Wagner EK, Hopp K, Schenk EL, Weiser-Evans MC, Clambey ET, Nemenoff RA, Tumor-intrinsic response to IFNgamma shapes the tumor microenvironment and anti-PD-1 response in NSCLC, Life Sci Alliance, 2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Johnson AM, Bullock BL, Neuwelt AJ, Poczobutt JM, Kaspar RE, Li HY, Kwak JW, Hopp K, Weiser-Evans MCM, Heasley LE, Schenk EL, Clambey ET, Nemenoff RA, Cancer Cell-Intrinsic Expression of MHC Class II Regulates the Immune Microenvironment and Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Lung Adenocarcinoma, J Immunol, 204 (2020) 2295–2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Marino S, Vooijs M, van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A, Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum, Genes Dev, 14 (2000) 994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kwak JW, Laskowski J, Li HY, McSharry MV, Sippel TR, Bullock BL, Johnson AM, Poczobutt JM, Neuwelt AJ, Malkoski SP, Weiser-Evans MC, Lambris JD, Clambey ET, Thurman JM, Nemenoff RA, Complement Activation via a C3a Receptor Pathway Alters CD4(+) T Lymphocytes and Mediates Lung Cancer Progression, Cancer research, 78 (2018) 143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G, User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability, Neuroimage, 31 (2006) 1116–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Poczobutt JM, Nguyen TT, Hanson D, Li H, Sippel TR, Weiser-Evans MC, Gijon M, Murphy RC, Nemenoff RA, Deletion of 5-Lipoxygenase in the Tumor Microenvironment Promotes Lung Cancer Progression and Metastasis through Regulating T Cell Recruitment, J Immunol, 196 (2016) 891–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, Albright A, Cheng JD, Kang SP, Shankaran V, Piha-Paul SA, Yearley J, Seiwert TY, Ribas A, McClanahan TK, IFN-gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade, The Journal of clinical investigation, 127 (2017) 2930–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lau D, Khare S, Stein MM, Jain P, Gao Y, BenTaieb A, Rand TA, Salahudeen AA, Khan AA, Integration of tumor extrinsic and intrinsic features associates with immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer, Nature communications, 13 (2022) 4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bylicki O, Paleiron N, Margery J, Guisier F, Vergnenegre A, Robinet G, Auliac JB, Gervais R, Chouaid C, Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint in EGFR-Mutated or ALK-Translocated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer, Target Oncol, 12 (2017) 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV, Fu X, Azzoli CG, Piotrowska Z, Huynh TG, Zhao L, Fulton L, Schultz KR, Howe E, Farago AF, Sullivan RJ, Stone JR, Digumarthy S, Moran T, Hata AN, Yagi Y, Yeap BY, Engelman JA, Mino-Kenudson M, EGFR Mutations and ALK Rearrangements Are Associated with Low Response Rates to PD-1 Pathway Blockade in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis, Clin Cancer Res, 22 (2016) 4585–4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].To KKW, Fong W, Cho WCS, Immunotherapy in Treating EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer: Current Challenges and New Strategies, Front Oncol, 11 (2021) 635007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Korpela SP, Hinz TK, Oweida A, Kim J, Calhoun J, Ferris R, Nemenoff RA, Karam SD, Clambey ET, Heasley LE, Role of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced interferon pathway signaling in the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma therapeutic response, J Transl Med, 19 (2021) 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kleczko EK, Hinz TK, Nguyen TT, Gurule NJ, Navarro A, Le AT, Johnson AM, Kwak J, Polhac DI, Clambey ET, Weiser-Evans M, Patil T, Schenk EL, Heasley LE, Nemenoff RA, Adaptive immunity is required for durable responses to alectinib in murine models of EML4-ALK lung cancer, bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2022.04.14.488385 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T, Lafontaine L, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Becker C, Pages F, Speicher MR, Trajanoski Z, Galon J, Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer, Immunity, 39 (2013) 782–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Oxnard GR, Yang JC, Yu H, Kim SW, Saka H, Horn L, Goto K, Ohe Y, Mann H, Thress KS, Frigault MM, Vishwanathan K, Ghiorghiu D, Ramalingam SS, Ahn MJ, TATTON: a multi-arm, phase Ib trial of osimertinib combined with selumetinib, savolitinib, or durvalumab in EGFR-mutant lung cancer, Ann Oncol, 31 (2020) 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yang JC, Shepherd FA, Kim DW, Lee GW, Lee JS, Chang GC, Lee SS, Wei YF, Lee YG, Laus G, Collins B, Pisetzky F, Horn L, Osimertinib Plus Durvalumab versus Osimertinib Monotherapy in EGFR T790M-Positive NSCLC following Previous EGFR TKI Therapy: CAURAL Brief Report, Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, 14 (2019) 933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ware KE, Hinz TK, Kleczko E, Singleton KR, Marek LA, Helfrich BA, Cummings CT, Graham DK, Astling D, Tan AC, Heasley LE, A mechanism of resistance to gefitinib mediated by cellular reprogramming and the acquisition of an FGF2-FGFR1 autocrine growth loop, Oncogenesis, 2 (2013) e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ, Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion, Science, 331 (2011) 1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Poczobutt JM, De S, Yadav VK, Nguyen TT, Li H, Sippel TR, Weiser-Evans MC, Nemenoff RA, Expression Profiling of Macrophages Reveals Multiple Populations with Distinct Biological Roles in an Immunocompetent Orthotopic Model of Lung Cancer, J Immunol, 196 (2016) 2847–2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in GEO Datasets (GSE217405).