Abstract

A technique to fabricate hollow fibers with porous walls via templating from high internal phase emulsions (HIPEs) has been demonstrated. This technique provides an environmentally friendly process alternative to conventional methods for hollow-fiber productions that typically use organic solvents. HIPEs containing acrylate monomers were extruded into an aqueous curing bath. Osmotic pressure effects, manipulated through differences in salt concentration between the curing bath and the aqueous phase within the HIPE were used to control the hollow structures of polyHIPE fibers. The technique was used to produce porous fibers (with millimeter-scale diameters and micronscale pores) having a hollow core (with a diameter of 50%–75% of the fiber diameter). Two potential applications of the hollow fibers were demonstrated. In vitro drug release studies using these hollow fibers show a controlled release profile that is consistent with the microstructure of the porous fiber wall. In addition, the presence of pores in the walls of polyHIPE fibers also enable size-selective loading and separation of functional materials from an external suspension.

Keywords: biomaterials, drug delivery, emulsion templating, macroporous polymer, polyHIPE fibers

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Porous fibers with a hollow center are ideal materials for applications such as encapsulation,1 controlled release,2 separation,3,4 and sensing.5 Fabrication of such delicate morphological structures can be a challenge. Currently, the most common routes use spinning methods6,7 including wet-spinning8 and dry-jet wet spinning9 techniques to generate fibers. However, these strategies use organic solvents and rely on evaporation to create the hollow center and porous walls. In conventional processes, a polymer solution is extruded through a multi-orifice spinneret into a coagulation bath where solidification occurs. The hollow center inside the fiber is created by extraction10 where a solvent selectively dissolves the core material. Nonsolvent-induced phase separation has also been studied to introduce the hollow core and porosity in polymer fibers.11 Porous fibers generated through emulsion templating have been reported.12–14 However, none report both a porous and hollow fiber morphology achieved without the use of organic solvent or with hydrophobic monomers. Typically, fibers generated by wet-spinning or microfluidic assembly using aqueous solutions have been limited to hydrophilic materials including calcium alginate15 and poly(ethylene glycol) methyl methacrylate.12

PolyHIPEs are highly porous materials prepared by polymerizing monomers in the continuous phase of an emulsion in which the dispersed aqueous droplets have a volume fraction that exceeds 74%.16 Within the polyHIPE material, interconnected voids are formed by the shrinkage of the thin film between two neighboring droplets during polymerization and subsequent removal of the droplet phase. The highly porous and interconnected morphology allows for mass transport throughout the bulk material, which is essential for diffusion of active ingredients and components including drugs17 and cells.18 Furthermore, polyHIPE properties have been shown to be adaptable for many different applications. For example, Kranjc et al.19 used an additional surface treatment to expand the potential of the polyHIPE to be used for heavy metal absorption. PolyHIPEs have also been studied as controlled drug release matrices to address the need for wound dressings that require a continuous release of antibiotic to prevent infections.20 In addition, polyHIPEs with pores on the order of microns are capable of separating large biomolecules.21

There have been many studies showing the wide applicability of polyHIPE monoliths or beads, but none have used the emulsion templating technique to generate porous hollow fibers. Here, we demonstrate a technique to fabricate porous hollow fibers in one step. The composition of the curing bath allows for control over the hollow structure of the fiber through the osmotic pressure difference between the curing bath and the HIPE. In addition, the potential of the polyHIPE hollow fibers to be used for applications such as drug delivery and size-based particle-exclusion separations have been explored.

In this paper, we demonstrate a new method to fabricate porous hollow fibers via polymerization of a high internal phase emulsion (HIPE) in an aqueous bath. This simple and eco-friendly process eliminates the use of organic solvents and the need for double- or triple-orifice spinneret equipment.

2.|. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1 |. Materials

The monomers 2-ethylhexyl acrylate (EHA; 98%) and 2-ethylhexyl methacrylate (EHMA; 98%), cross-linker ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA; 98%), initiator sodium persulfate (NaPS; 98%), sodium chloride (NaCl; 99%), surfactants dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide (DODAB; 98%) and Span 80, hydrochloric acid (HCl; 37%), and ciprofloxacin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. The alcohol 2-propanol (IPA; 99.5%) was obtained from Fisher Scientific. Superffin infiltration media was purchased from Source Medical Products. Fluoresbrite YO Carboxylate 0.50-μm microspheres and Fluoresbrite YG 25-μm microspheres were ordered from Polysciences, Inc. Polymeric microspheres (polystyrene divinyl benzene, diameter 1–15 μm) were obtained from Duke Scientific Corporation.

2.2 |. HIPE preparation

For the water-in-oil HIPEs, the aqueous phase was composed of 2 wt% NaCl in deionized (DI) water. The continuous oil phase was composed of EHA, EHMA, and EGDMA in the weight ratio of 8:8:5. Additionally, 1.8 g Span 80 and 0.18 g DODAB, serving as the surfactants, were mixed into 21 g of oil phase. The oil and water components were mixed by placing 4 g of the oil phase in a 500-mL bottle with an impeller rotating at 300 rpm. A 10:1 w/o HIPE was generated by adding 40 g aqueous phase solution at a uniform rate into the bottle over 1 min, followed by continued mixing for another 7 min.

2.3 |. Curing bath

Porous hollow fibers were produced in a curing bath containing an initiator (NaPS) and varying concentrations of salt (NaCl). Three different curing bath compositions (B1, B2, and B3) were investigated (Table S1). The combination of the salt (NaCl) and initiator (NaPS) enabled the generation of hollow structures inside the polyHIPE fiber.

2.4 |. Fiber preparation

Porous fibers were produced by extruding 1 mL of HIPEs through a 1-mL syringe with the extrusion orifice (a syringe needle) having an inner diameter of either 1.81 or 3.35 mm at the rate of 20 mL/min. The extrudate was collected into 100 g of curing bath heated to 90°C. Curing time was fixed at 5 min. After curing, the polyHIPE fibers were removed from the bath and dried at room temperature for characterization.

2.5 |. Morphology analysis

The morphology of porous fibers was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-6510LV). The samples were sputter-coated with gold before SEM observation. The software package ImageJ was used to analyze fiber dimensions and microstructure.

2.6 |. In vitro drug-release test

The efficacy of drug-loaded fibers for wound healing applications is dependent upon the mechanical properties, biocompatibility, hydrolytic stability, and the release rate of the loaded antibiotic.22,23 Since the fibers prepared here are made from a flexible acrylate polymer and the drug can be loaded in an aqueous environment, the drug release through the porous fiber walls was investigated. Drug release studies were carried out in 0.1 M HCl solution (pH of about 1) which is appropriate for ciprofloxacin release in vivo. Ciprofloxacin is typically taken orally and is released in the stomach in highly acidic conditions with the absorption of the drug in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Hollow polyHIPE fibers fabricated using curing bath B2 (Table S1) were cut into 1-cm lengths for controlled-release experiments using the drug ciprofloxacin. Superffin (a blend of highly purified paraffin and plastic polymers) heated to 60°C was used to seal one end of the hollow fiber. Subsequently, 2 mg of ciprofloxacin powder was added into the hollow core of the fiber using a 31-gauge needle. The other end of the fiber was then sealed by Superffin following a similar sealing procedure. The drug-loaded fiber was immersed in 1.5 mL of 0.1 M HCl solution at room temperature. Thirty microliters aliquots of solution were collected at time points of 3, 6, 15, 24, 48, and 72 h. Equal amounts of fresh 0.1 M HCl solution were added back to the incubation after collection of each sample to maintain the same overall solution volume. A spectrophotometer (Sunnyvale, CA) was used to determine the drug concentration using absorption peaks at 275 nm. Linear calibration curves were generated to calculate the actual drug concentrations. Each concentration point reports the average concentration of ciprofloxacin for two independent samples that were tested twice. The overall drug release profile was calculated using

| (1) |

where is the drug concentration measured at the nth time point, is the total volume of the solution used in the drug-release test (1.5 mL), is the volume removed at each time point for measurement, indicates the concentration of drug at the ith time point, and M is the mass of drug initially loaded into the hollow fiber.

2.7 |. Loading of microspheres

Fluorescent monodispersed polystyrene microspheres with 0.5 and 25 μm diameters were used to evaluate the size-based loading and separation properties of polyHIPE fibers. Microspheres were first dispersed in IPA with a concentration of 0.25 wt%. Both polyHIPE fibers cured in baths B1 and B2 were then separately immersed into these microsphere suspensions at 4°C. After 24 h of immersion, the fibers were dried and cut into very thin films (less than 0.5 mm) for fluorescence microscopy (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) observations. Samples were imaged under a 10× objective. Only the internal regions of the fiber not directly exposed to the microsphere suspension were imaged. Both the polyHIPE morphology and the location of fluorescent microspheres were detected.

3 |. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 |. Formation of porous hollow fibers

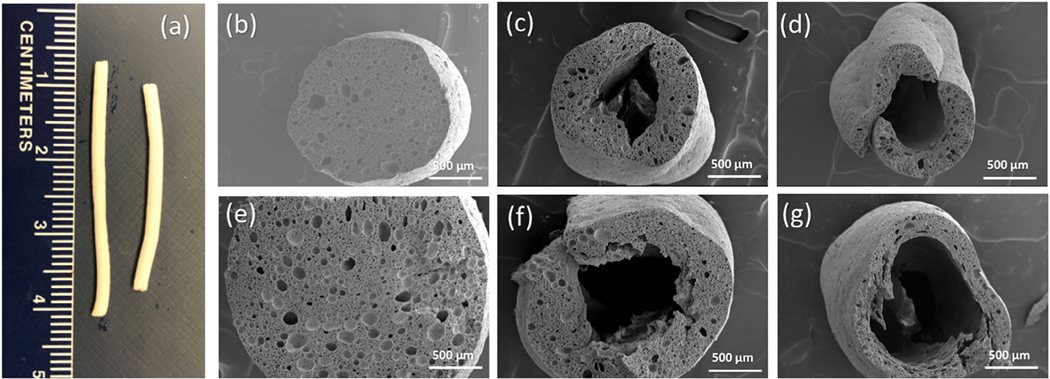

Images of representative fibers prepared in this study are shown in Figure 1. The HIPEs were extruded into a heated curing bath with compositions as described in Table S1. No initiator was present in the HIPE itself, so the polymerization reaction begins as the HIPE contacts the curing bath and the reaction starts from the HIPE-curing bath interface. The difference in electrolyte concentration between the curing bath and the HIPE is the critical parameter used to manipulate the fiber morphology and create the hollow core of the porous fibers. Non-hollow porous fibers are created when there is no gradient in the electrolyte concentration gradient, that is, when HIPE (containing 2 wt% NaCl) was extruded into a curing bath of containing 2 wt% electrolyte (curing bath B1). In this case, osmotic transport of water between the HIPE and the curing bath driven is limited, and the initiator is transported into HIPE only by diffusion. The relative rates of osmotic transport, polymerization kinetics, and emulsion destabilization govern the morphology of the porous structure and the formation of the hollow core. The polymerization reaction kinetics is typically faster than the kinetics of the destabilization of the emulsion which is favored thermodynamically. The initiation of the polymerization reaction starting from the surface of the HIPE in contact with the bath was efficient enough to polymerize throughout the fiber radius and maintain the HIPE morphology (Figure 1b). However, when a difference in electrolyte concentration is imposed by increasing its concentration in the curing bath above that in the HIPE, porous hollow fibers are generated. With a higher concentration of electrolyte in the bath, osmotic pressure drives the water from the HIPE towards the curing bath. This outward flow retards the diffusion of initiator into the fiber, slowing down the polymerization reaction to a timescale where destabilization of the emulsion can occur near the center of the fiber, the region farthest from the HIPE-curing bath interface. Coalescence that occurs near the center of the forming fiber result in a hollow structure with the walls retaining the HIPE morphology (Figure 1c). Hollow fibers with thinner walls were obtained when the NaCl concentration in the curing bath was increased from 4 to 6 wt% (Figure 1d). A higher electrolyte concentration difference between the curing bath and the HIPE leads to greater outward flux of water, thus further diluting the initiator concentration inside the fiber as it forms, and results in less polymerization in the center. As shown in Table 1, polyHIPE fibers were made hollow simply by varying the electrolyte concentration gradient between the HIPE and the curing bath, and the length-scale of the hollow interior was found to be dependent on the magnitude of the electrolyte gradient.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Photographs of polyHIPE fibers fabricated in curing baths B1 (left) and B2 (right). SEM images of polyHIPE fibers fabricated with orifice diameter 1.81 mm and prepared in (b) curing bath B1 containing 2 wt% NaCl and 0.3 wt% NaPS, (c) curing bath B2 containing 4 wt% NaCl and 0.3 wt% NaPS, and (d) curing bath B3 containing 6 wt% NaCl and 0.3 wt% NaPS. SEM images of polyHIPE fibers fabricated with orifice die diameter 3.35 mm and prepared in curing baths (e) B1, (f) B2, and (g) B3

TABLE 1.

Effects of curing bath parameters on polyHIPE fiber dimensions

| Orifice diameter | 1.81 mm |

3.35 mm |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl concentration in the curing bath | 2 wt% | 4 wt% | 6 wt% | 2 wt% | 4 wt% | 6 wt% |

| Fiber diameter (μm) | 1512 ± 97 | 1202 ± 61 | 904 ± 74 | 2516 ± 54 | 2012 ± 274 | 1550 ± 116 |

| Wall thickness (μm) | - | 287 ± 68 | 142 ± 63 | - | 428 ± 77 | 205 ± 37 |

| Wall thickness/fiber diameter | - | 0.23 | 0.16 | - | 0.21 | 0.13 |

We also investigated the effect of the diameter of the orifice (the syringe needle) used to extrude the HIPE on the ultimate size of the polyHIPE fibers. As seen in Figure 1e–g, increasing the diameter of the orifice from 1.81 to 3.35 mm resulted in an increase of the outer diameter of the fiber as well as the size of the hollow interior for an equivalent bath composition. Figure S1 displays high magnification images of polyHIPE fibers showing their cross-section and surface morphologies. Table 1 provides the average dimensions of polyHIPE fiber and their wall thicknesses.

The diameter of the polyHIPE fibers was always smaller than the orifice used for the HIPE extrusion. This result can be attributed to the shrinkage in volume associated with the conversion of monomer to polymer.24,25 Also, since EHA and EHMA have a solubility in water of around 0.1 g/L and the water solubility of EGDMA is about 1.1 g/L at room temperature, monomers may dissolve into the curing bath during curing resulting in a reduction in the mass of polymer formed into fiber. Additionally, the outer diameter of the polyHIPE fiber was found to gradually decrease with increasing electrolyte concentration in the bath.

Considering that non-hollow fibers (i.e., those formed using the 2 wt% NaCl curing bath) show approximately a 20% reduction in diameter compared to the extruded HIPE, it is possible to calculate the fiber diameters expected for the hollow fibers (i.e., those cured in 4 and 6 wt% NaCl baths). Table S2 shows these results normalized by the non-hollow fiber diameter. These results reveal that every 2-wt% increase in electrolyte concentration in the bath results in approximately 20% reduction the fiber diameter. This reduction can be explained by the competing processes of polymerization and emulsion destabilization mediated by initiator concentration at the fiber surface. When HIPE is extruded into a curing bath with high electrolyte concentration (curing bath B3), less initiator is present in both the outer and inner region of HIPE due to osmotically driven water-transport from the fiber diluting the initiator concentration at the surface of the HIPE. The reduced initiator efficiency gives time for emulsion destabilization to occur before the polymerization reaction locks-in13 the polyHIPE morphology. The hollow fiber wall thickness also reduced significantly when increasing the NaCl concentration of the curing bath above that of the HIPE. The ratio of wall thickness to overall fiber diameter decreased from 0.23 to 0.16 for the fibers extruded from the smaller (1.81 mm) orifice, and from 0.21 to 0.13 for the larger (3.35 mm) orifice. The ratio of wall thickness to fiber diameter decreases as the extruding diameter increases due to the longer pathway the initiator must travel from the surface to the center of HIPE during curing.

As Figure S1 indicates, the void and windows size or microstructure within the polyHIPE did not show a significant sensitivity to the NaCl concentration used in the curing bath. However, small pores about 5 μm in diameter can be observed on the fiber surface, which were much smaller than the typical void size (around 15 μm) in the bulk polyHIPEs. This surface feature results from the high concentration of initiator at the HIPE-curing bath interface, which rapidly initiates the polymerization at the fiber surface.

3.2 |. Drug-release studies

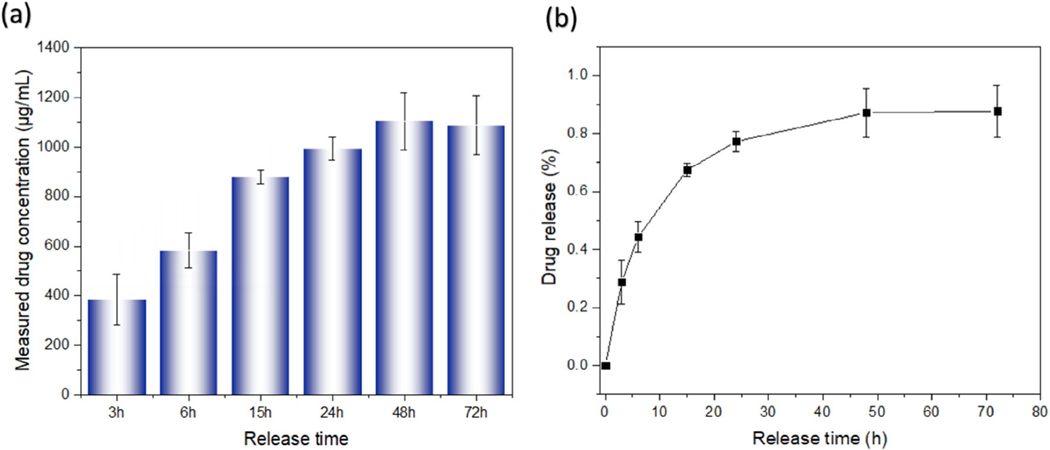

Hollow fibers fabricated from curing bath B2 were investigated as a vehicle for drug delivery using the antibiotic ciprofloxacin as a model drug. The hollow core of the fiber provides a reservoir for loading the drug powder, and the porosity of the fiber wall provides a tortuous barrier that hinders the rapid dissolution and release of the drug. As shown in Figure 2, the measured amount of drug concentration generally increased with time, reaching a maximum at 48 h indicating that porous hollow fibers continually released ciprofloxacin for at least 2 days. Since the two ends of the fiber were sealed, the ciprofloxacin could only diffuse radially through the fiber walls. Only about 30% of drug was released within the first 3 h, revealing that these porous hollow fibers have great potential as slow-release drug delivery devices. The slight decrease in measured concentration from 48 to 72 h is an artefact due to system dilution upon repeated sampling.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Measured drug concentration and (b) percentage of drug (see Equation 1) released over time from the ciprofloxacin-containing hollow fibers

3.3 |. Size-selective separation

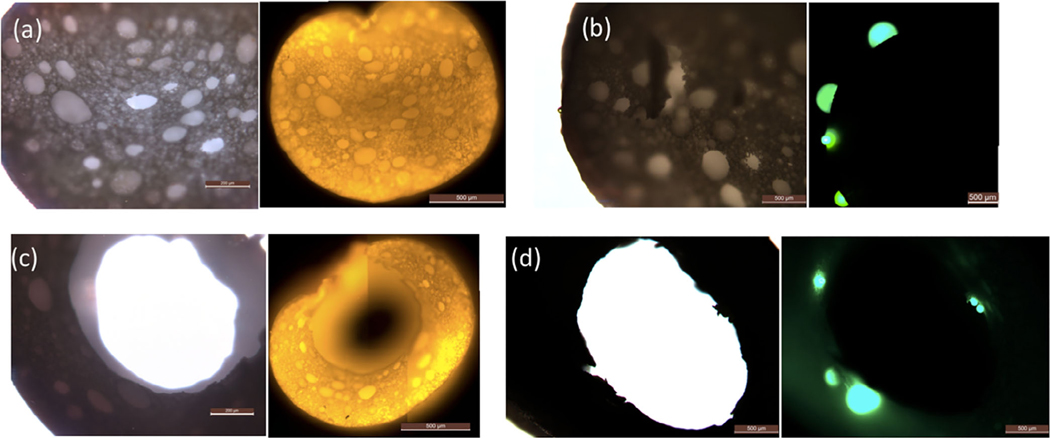

Porous media such as microfiltration membranes have morphology with pores on the nanoscale, and thus are not appropriate for the loading and separation of biomolecules with large dimension. The interconnected voids and windows in the polyHIPE fiber bulk and the porous fiber surface allow for the direct loading and separation of particles in the micron size range. A pore size analysis of the fibers is provided in Figure S2. More than half of the window and pore sizes in the fiber surface were less than 2 μm, whereas the largest opening for both cases was around 10 μm. Figure 3 displays normal and fluorescence optical micrographs of polyHIPE fibers after soaking in a suspension of small (0.5 μm in diameter) and large (25 μm in diameter) fluorescent microspheres. The bright orange light observed inside the fibers (Figure 3a,c) proves that the small microspheres were easily transported into the bulk of the fiber through the porous fiber surface. In contrast, microspheres with diameters larger than the maximum pore size on the fiber surface, were unable to penetrate the fiber wall. Green fluorescent beads can only be observed in the fiber outer surface (Figure 3b) and the hollow fiber inner surface (Figure 3d). The loading and separation of microspheres with size ranging from 1 to 15 μm is provided in Figure S3; the highly interconnected internal structure enables polyHIPE fibers to have potential applications in selective particle loading and separation.

FIGURE 3.

Optical (left) and fluorescence (right) optical micrographs: (a) fiber loaded with 0.5-μm microspheres; (b) fiber with 25-μm microspheres on its surface; (c) hollow fiber loaded with 0.5-μm microspheres; and (d) hollow fiber with 25-μm microspheres on its surface

4 |. CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated a facile and environmentally friendly method to fabricate porous fibers and porous hollow fibers via HIPE templating. An efficient strategy for tuning polyHIPE fibers structure by simply changing the electrolyte concentration gradient between the curing bath and HIPE was developed. Specifically, higher concentration of electrolyte in the curing bath compared to the emulsion itself generates an osmotic pressure difference between HIPE aqueous phase and the curing bath, resulting in the formation of hollow fibers. This fabrication method provides a new strategy to generate porous hollow fibers that is simple, safe, and “green.” Two potential applications of the porous hollow fibers were demonstrated. The ciprofloxacin-release test indicates that the porous hollow fibers can be effective slow drug release materials, with a continuous release of ciprofloxacin up to 48 h. The size exclusion property of the fibers was also demonstrated by fluorescent microscopy. This work demonstrates the feasibility of this new design strategy for porous hollow fibers. This simple fabrication strategy is applicable for large scale manufacture, as well as for the fabrication of fiber mats and fiber membranes. These functional materials could expand the potential applications of the fibers to water purification, polymer and biomolecular separation, and micro-encapsulation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health: EB021911 (to H.B.).

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: EB021911

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kang A, Park J, Ju J, Jeong GS, Lee S-H, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ceci-Ginistrelli E, Pontremoli C, Pugliese D, Barbero N, Barolo C, Visentin S, Milenese D, Mater. Lett 2017, 191, 116. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liang CZ, Yong WF, Chung T-S, J. Memb. Sci 2017, 541, 367. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Luo J, Huang Z, Lium L, Wang H, Ruan G, Zhao C, Du F, J. Separat. Sci 2021, 44, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fortin N, Klok H-A, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Altinkok C, Karabulut HRF, Tasdelen MA, Acik G, Mater. Today Commun 2020, 25, 101425. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Daglar O, Altinkok C, Acik G, Durmaz H, Macromol. Chem. Phys 2020, 221, 2000310. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jia Z, Lu C, Liu Y, Zhou P, Wang L, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 2016, 4, 2838. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Handge UA, Radjabian M, Abetz V, Sankhala K, Koll J, Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1600991. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Khalf A, Singarapu K, Madihally SV, Cellulose 2015, 22, 1389. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bonyadi S, Chung TS, Krantz WB, J. Memb. Sci 2007, 299, 200. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bell RV, Parkins CC, Young RA, Preuss CM, Stevens MM, Bon SAF, J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 813. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang T, Sanguramath RA, Israel S, Silverstein MS, Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5445. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Samanta A, Nandan B, Srivaslave RK, Colloid Interf J. Sci. 2016, 471, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Onoe H, Okitsu T, Itou A, Kato-Negishi M, Gojo R, Kiriya D, Sato K, Miura S, Iwanaga S, Kuribayashi-Shigatomi K, Matsunage YT, Shimoyama Y, Takeuchi S, Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lissant KJ, Colloid Interf J. Sci. 1966, 22, 462. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Silverstein MS, Prog. Polym. Sci 2014, 39, 199. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hayward AS, Sano N, Przyborski SA, Cameron NR, Macromol. Rapid Commun 2013, 34, 1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huš S, Kolar M, Krajnc P, Chromatogr J. A 2016, 1437, 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moglia R, Whitely M, Brookes M, Robonson J, Pishko M, Cosgriff-Hernandez E, Macromol. Rapid Commun 2014, 35, 1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jungbauer A, Hahn R, Chromatogr J. A 2008, 1184, 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chou S-F, Carson D, Woodrow KA, Controlled Release J.2015, 220, 584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ni Y, Lin W, Mu R-J, Wu C, Wang L, Wu D, Chen S, Pang J, RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boots HMJ, Pandey RB, Polym. Bull 1984, 11, 415. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xu H, Zheng X, Huang Y, Wang H, Du Q, Langmuir 2016, 32, 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.