Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the effectiveness of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy for improving accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and accommodative dysfunction.

Methods:

We report changes in accommodative function following therapy among participants in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial – Attention and Reading Trial with decreased accommodative amplitude (115 participants in vergence/accommodative therapy; 65 in placebo therapy) or decreased accommodative facility (71 participants in vergence/accommodative therapy; 37 in placebo therapy) at baseline. The primary analysis compared mean change in amplitude and facility between the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups using analyses of variance models after 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of treatment. The proportions of participants with normal amplitude and facility at each time point were calculated. The average rate of change in amplitude and facility from baseline to week 4 and from weeks 4 to 16 were determined in the vergence/accommodative therapy group.

Results:

From baseline to 16 weeks, the mean improvement in amplitude was 8.6 diopters (D) and 5.2 D in the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively (mean difference = 3.5 D, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.5 to 5.5 D; P = 0.012). The mean improvement in facility was 13.5 cycles per minute (cpm) and 7.6 cpm in the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively (mean difference = 5.8 cpm, 95% CI: 3.8 to 7.9 cpm; P < 0.0001). Significantly greater proportions of participants treated with vergence/accommodative therapy achieved a normal amplitude (69% vs. 32%, difference = 37%, 95% CI: 22 to 51%; P < 0.0001) and facility (85% vs. 49%, difference = 36%, 95% CI: 18 to 55%; P < 0.0001) than those who received placebo therapy. In the vergence/accommodative therapy group, amplitude increased at an average rate of 1.5 D per week during the first 4 weeks (P < 0.0001), then slowed to 0.2 D per week (P = 0.002) from weeks 4 to 16. Similarly, facility increased at an average rate of 1.5 cpm per week during the first 4 weeks (P < 0.0001), then slowed to 0.6 cpm per week from weeks 4 to 16 (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Office-based vergence/accommodative therapy is effective for improving accommodative function in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and coexisting accommodative dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Accommodative insufficiency and accommodative infacility are common vision disorders in school-aged children with prevalence estimates of 8 to 18% based on samples of students between 7 and 19 years of age.1–3 Common symptoms include blurred vision at near, intermittent blur with change of fixation between near and far, headaches, eye fatigue, poor maintenance of concentration during reading or near work, and avoidance of near activities.4–7 Previous studies have found that children diagnosed with convergence insufficiency often have coexisting accommodative insufficiency and infacility.8–10

The most common treatments for accommodative dysfunction are a plus lens addition for near work or accommodative therapy.4,11–13 Studies of accommodative therapy in children have shown improvements in clinical measures of accommodative function4,8,11,14,15 and associated symptoms,4,16 however, only one of these studies was a randomized controlled trial.8

The data for this report are from the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial – Attention and Reading Trial (CITT-ART), a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the effectiveness of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy on reading and attention in 310 children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.17,18 Therapy procedures for accommodation were included in the CITT-ART treatment protocol, and accommodative amplitude and facility were measured at baseline and regular intervals throughout the study, thus providing the opportunity to assess the effectiveness of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy for treating accommodative dysfunction.

The main aim of the present study was to determine the effectiveness of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy in improving accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility by comparing it with office-based placebo therapy in school-aged children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and a coexisting accommodative dysfunction. We also determined the proportion of children who achieved normal accommodative amplitude and facility in both vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups. Lastly, in the vergence/accommodative therapy group, we evaluated the rate of change in these accommodative functions.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This study was supported through a cooperative agreement with the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki by the CITT-ART Investigator Group at 9 clinical centers. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant informed consent and assent forms were approved by each site’s institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian of each participant and written assent (if required) was obtained from each participant prior to study-related data collection. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided oversight (see Acknowledgments). The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial-Attention and Reading Trial (NCT02207517). The full study protocol and Manual of Procedures are available on the CITT-ART study website (https://u.osu.edu/cittart/; accessed 01/28/2020).

Participant Selection

The CITT-ART enrolled participants 9 to 14 years old (grades 3 to 8) with symptomatic convergence insufficiency, defined as near exophoria at least 4Δ greater than at far, a receded near point of convergence (6 cm or greater break), insufficient positive fusional vergence at near [i.e., failing Sheard’s criterion19 (positive fusional vergence less than twice the near phoria) or positive fusional vergence less than 15Δ], and score of ≥16 on the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS).20,21 Those with a cycloplegic refraction of ≥ 2.00 diopters (D) spherical equivalent (SE) of hyperopia, > 0.75 D SE of myopia, > 1.00 D of astigmatism, or > 0.75 D of SE anisometropia were required to wear a refractive correction for a minimum of 2 weeks prior to enrollment. Hyperopic corrections could be symmetrically reduced up to 1.50 D at investigator discretion. Monocular accommodative amplitude was required to be ≥ 5 D. A complete listing of CITT-ART eligibility and exclusion criteria has been reported previously.17

Measurement of Accommodative Function

Certified examiners collected standardized measures of monocular accommodative amplitude and monocular accommodative facility in the right eye of participants wearing their refractive correction (if required) at baseline and after 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of therapy. Measures at the follow-up visits were collected by examiners masked to participants’ assigned treatment group. Monocular accommodative amplitude was measured using the push-up method with a moveable card containing a 20/30-sized column of letters attached to Gulden Near Point Rule (Gulden Ophthalmics, Elkins Park, PA).22 The card was advanced at a consistent speed of approximately 1 to 2 centimeters per second from a starting point of 40 cm toward the participant’s right eye. The distance from the eye to the point where the participant first reported sustained blur of the letters was recorded to the nearest half centimeter and then converted into diopters. Monocular accommodative facility was determined by calculating the speed with which participants reported a 20/30-sized vertical column of letters at 40 cm to be clear while viewing through alternating +2.00 D and −2.00 D lenses (lens immediately changed to the other when the letters reported to be clear). The number of cycles per minute (cpm) (one cycle being the ability to clear the plus lens followed by the minus lens) were counted.

Criteria for Decreased and Normal Accommodative Amplitude and Accommodative Facility

For the present analysis, decreased accommodative function was determined based on whether or not a “minimum” criterion was met. The combined normative data from studies by Hashemi et al.23 and Castagno et al.24 that used similar testing procedure as the present study show that the average accommodative amplitude is approximately 14 D with a standard deviation (SD) of 3 D in children 9 to 14 years old. Thus, decreased amplitude was defined as monocular accommodative amplitude <11 D, which is 1 SD below the normative value of 14 D. Deficient monocular accommodative facility was defined as <6 cpm with ±2.00 D lenses, which is 1 SD below the normative value of 11 cpm for school-age children.5,25

For outcome measures, normal accommodative amplitude was defined as ≥ 14 D23,24 and normal accommodative facility was defined as ≥ 11 cpm.5,25

Treatment and Follow-up

Subsequent to enrollment, CITT-ART participants were randomly assigned using a permuted design of random blocks of 3, 6, and 9 by site to either office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (hereafter vergence/accommodative therapy; N = 206) or office-based placebo therapy (hereafter placebo therapy; N = 104) in a 2:1 ratio using a central web-based system (Research Electronic Data Capture; REDCap) at the Coordinating Center.26

Certified therapists followed a standardized, sequential treatment protocol of therapy specific to each treatment group; these protocols have been described previously27 and are outlined briefly below. Both groups received weekly 60-minute in-office therapy visits for 16 weeks, where participants performed 4 to 5 therapy procedures under a therapist’s guidance. Therapy procedures were also prescribed to be performed at home for 15 minutes per day for 5 days per week.

The goal of the in-office and home accommodative therapy procedures was to improve accommodative amplitude and facility. The therapy program consisted of typical accommodative therapy procedures using different lens powers, print size, or viewing distances to change accommodative demand, with procedures sequenced from monocular to bi-ocular to binocular, based on the attainment of pre-specified objectives and endpoints.12,28(Table 1)

Table 1.

Accommodative therapy procedures*

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocular loose lens facility | A, F | A, F | ||

| Monocular letter chart facility | A, F | A, F | ||

| Monocular Bull’s eye facility | A, F | A, F | ||

| Monocular lens sorting | A | A | ||

| Stereoscope bi-ocular facility | F | |||

| Prism dissociation bi-ocular facility | F | |||

| Computer orthopter bi-ocular facility | F | F | ||

| Binocular ±2.00 D lens flipper facility | F |

A = technique emphasizes accommodative amplitude; F = technique emphasizes accommodative facility. A, F = technique trains both accommodative amplitude and facility with initial emphasis on amplitude.

Specifics of the therapy procedures are described in the CITT-ART Manual of Procedures: https://u.osu.edu/cittart/manual-of-procedures/

The placebo therapy procedures were designed to look like real vergence/accommodative therapy, but not to stimulate vergence or accommodation skills beyond typical daily visual activities. For example, one placebo procedure involved viewing large letters through plano lenses, whereas an actual accommodative procedure involved viewing small letters through minus lenses. To mimic real therapy, participants were consistently encouraged to keep the target clear during training.

Participants and their parents were masked regarding treatment assignment. Examiners masked to participants’ treatment group conducted follow-up examinations after 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of therapy (hereafter referred to as week 4, week 8, week 12, and week 16 examinations), with the week-16 examination being the primary outcome examination.

Statistical Methods

All statistical testing was performed at a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for within- and between-group differences. All data were analyzed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

All CITT-ART participants with decreased accommodative amplitude and/or facility who completed their 16-week outcome examination were analyzed in their randomized group (i.e., intent to treat analysis). Thus, these analyses are based on a subset (N = 180 for the accommodative amplitude analysis; N = 108 for the accommodative facility analysis) of the original clinical trial cohort (N=310).

The mean, standard deviation (SD), and mean change in accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility from baseline to outcome were calculated for each treatment group. Comparisons within and between groups over time were done separately for accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility, using a 2 group × 5 time point repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) model, with a random effect for clinical site. Baseline characteristics (Tables 2A and 2B) were screened for inclusion as potential confounding variables in each model; however, none were included in the final models because there were no statistically significant or clinically relevant treatment group differences for any baseline characteristic. Multiple comparisons were controlled by the Sidak method.29 Given that participants were 9 to 14 years, a subsequent sensitivity analysis was also conducted using the same ANOVA model to control for age.

TABLE 2A.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of participants with reduced accommodative amplitude by treatment group

| Vergence/Accommodative Therapy (N = 115) | Placebo Therapy (N = 65) | Overall (N = 180) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 10.8 (1.5) | 10.9 (1.4) | 10.8 (1.4) |

| Sex, female, N (%) | 75 (65) | 34 (52) | 109 (61) |

| White Race, N (%) | 71 (62) | 35 (54) | 106 (59) |

| Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity, N (%) | 39 (34) | 23 (36) | 62 (34) |

| Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey score, mean (SD) | 30.3 (8.6) | 31.9 (8.9) | 30.9 (8.7) |

| Monocular Accommodative Amplitude (D), mean (SD) | 7.6 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.7) |

| Monocular Accommodative Facility (cpm), mean (SD) | 6.8 (4.2) | 6.8 (5) | 6.8 (4.5) |

| Exodeviation at distance (Δ), mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.7) | 2.2 (4.3) | 2.0 (3.4) |

| Exodeviation at near (Δ), mean (SD) | 9.9 (4.1) | 10.0 (5.7) | 10.0 (4.7) |

| Near Point of Convergence Break (cm), mean (SD) | 16.0 (8.3) | 17.0 (8.2) | 16.4 (8.2) |

| Positive Fusional Vergence Blur/Break† (Δ), mean (SD) | 10.7 (4.1) | 11.3 (4.2) | 10.9 (4.2) |

The blur finding was used, but if blur was not reported, the break finding was used.

SD = standard deviation; D = diopters; cpm = cycles per minute; Δ = prism diopters.

TABLE 2B.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of participants with reduced accommodative facility by treatment group

| Vergence/Accommodative Therapy (N = 71) | Placebo Therapy (N = 37) | Overall (N = 108) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 10.9 (1.4) | 10.8 (1.5) | 10.9 (1.4) |

| Sex, female, N (%) | 41 (58) | 15 (41) | 56 (52) |

| White Race, N (%) | 44 (62) | 19 (51) | 63 (58) |

| Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity, N (%) | 26 (37) | 12 (32) | 38 (35) |

| Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS) score, mean (SD) | 30.2 (9) | 31.2 (8.9) | 30.6 (9) |

| Monocular Accommodative Amplitude (D), mean (SD) | 9.5 (3.4) | 8.5 (3.6) | 9.2 (3.5) |

| Monocular Accommodative Facility (cpm), mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.9) |

| Exodeviation at distance (Δ), mean (SD) | −1.4 (2.2) | −0.9 (1.6) | −1.3 (2) |

| Exodeviation at near (Δ), mean (SD) | −9.1 (3.6) | −8.6 (4.3) | −8.9 (3.8) |

| Near Point of Convergence Break (cm), mean (SD) | 14.9 (8.7) | 15.5 (8.2) | 15.1 (8.5) |

| Positive Fusional Vergence Blur/Break† (Δ), mean (SD) | 10.8 (4.1) | 11.1 (4) | 10.9 (4.1) |

The blur finding was used, but if blur was not reported, the break finding was used.

SD = standard deviation; D = diopters; cpm = cycles per minute; Δ = prism diopters

The number and proportion of participants who met the normal age-expected amplitude and facility were tabulated and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for both groups. We investigated the trajectory of change in accommodative function for the vergence/accommodative therapy group by performing a post-hoc analysis using the 2 group × 5 time point ANOVA model to determine the rate of change for both accommodative amplitude and facility.

RESULTS

CITT-ART Study Results Related to Accommodation

Of the 310 CITT-ART participants, 215 (69%) had a coexisting accommodative dysfunction: 107 (50%) with decreased accommodative amplitude alone, 35 (16%) with decreased accommodative facility alone, and 73 (34%) with both.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Group

In the CITT-ART, there were 206 participants randomized to vergence/accommodative therapy group and 104 randomized to placebo therapy group. At baseline, decreased accommodative amplitude was present in 115 of the 206 (56%) participants randomized to vergence/accommodative therapy and in 65 of the 104 (63%) participants randomized to placebo therapy, with a mean baseline accommodative amplitude of 7.6 D (95% CI: 7.3 to 8.0 D) and 7.1 D (95% CI: 6.7 to 7.5 D) in the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively (P = 0.15). Decreased accommodative facility was present at baseline in 71 of 206 (34%) of the vergence/accommodative therapy group and in 37 of 104 (36%) of the placebo therapy group (P = 0.85), with a mean accommodative facility of 2.9 cpm (95% CI: 2.4 to 3.3 cpm) and 2.7 cpm (95% CI: 2.1 to 3.4 cpm) for the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively. Tables 2A and 2B provide baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of those with decreased accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility, respectively.

Outcome Visit Completion and Masking of Participants & Examiners

Of the participants who had decreased accommodative amplitude at baseline, 112 of 115 (97%) in the vergence/accommodative therapy group and 65 of 65 (100%) in the placebo therapy group completed their 16-week outcome visit. Of those with decreased accommodative facility at baseline, 67 of 71 (94%) and 37 of 37 (100%) in the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively, completed the 16-week outcome visit.

In regard to participant masking, among those with decreased accommodative amplitude at baseline, 89% (97/109) and 81% (52/64) assigned to vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively, stated they thought they had been assigned to the vergence/accommodative therapy group. For those with decreased accommodative facility, 88% (58/66) and 72% (26/36) assigned to vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups, respectively, responded that they thought they had been assigned to receive vergence/accommodative therapy. Four participants in the vergence/accommodative therapy group and 2 participants in the placebo therapy group did not provide a response as to whether they thought they were in the real or placebo treatment group. One examiner became unmasked at a study visit, but did not perform any subsequent masked examinations for that participant.

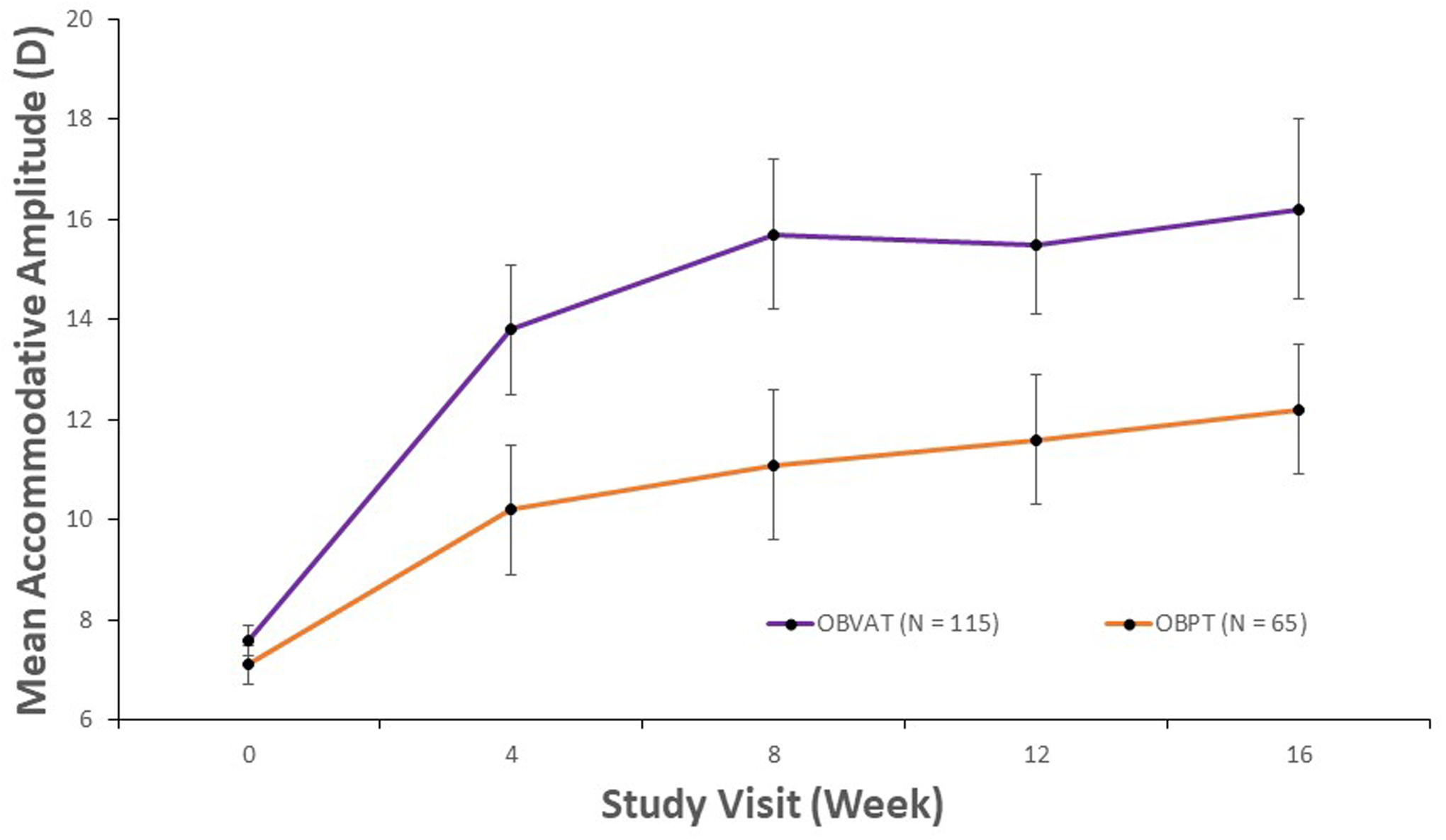

Changes in Accommodative Amplitude

From baseline to week 16, the mean accommodative amplitude improved from 7.6 D to 16.2 D in the vergence/accommodative therapy group (P < 0.0001) and from 7.1 D to 12.2 D in the placebo therapy group (P < 0.0001). The mean change in accommodative amplitude after 16 weeks of treatment was significantly greater in the vergence/accommodative therapy group compared with the placebo therapy group, with a treatment group difference of 3.5 D (95% CI: 1.5 to 5.5 D; P = 0.012). Table 3 shows the improvement in amplitude for each 4-week interval between masked examinations. In the vergence/accommodative therapy group, the largest increase in amplitude occurred between baseline and the 4-week visit; a smaller but significant increase occurred between weeks 4 to 8 with no significant increase occurred beyond week 8. Similarly, the greatest increase in amplitude for the placebo group was between baseline and the 4-week visit, with subsequent small and statistically insignificant improvements thereafter. Mean amplitude of accommodation was statistically significantly better for the vergence/accommodative therapy group than for the placebo therapy group at all four time points (Table 4; Figure 1). The sensitivity analysis that controlled for age yielded results that were essentially the same (data not shown) as the original results, suggesting that the age of the participant did not influence the results.

TABLE 3.

Change in accommodative amplitude and facility by treatment group between successive examinations

| Therapy | Vergence/Accommodative | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Intervals | Change† (95% CI) | P value | Change† (95% CI) | P value |

| Accommodative Amplitude (diopters) | ||||

| Baseline to Week 4 | 6.1 (4.9 to 7.4) | <0.0001 | 3.1 (1.4 to 4.7) | 0.004 |

| Week 4 to Week 8 | 2.0 (0.8 to 3.2) | 0.03 | 1.0 (−0.7 to 2.6) | 0.99 |

| Week 8 to Week 12 | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.0) | 0.99 | 0.5 (−1.2 to 2.1) | 0.99 |

| Week 12 to Week 16 | 0.7 (−0.5 to 2.0) | 0.99 | 0.6 (−1.1 to 2.2) | 0.99 |

| Baseline to Week 16 | 8.6 (7.4 to 9.8) | <0.0001 | 5.1 (3.4 to 6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Accommodative Facility (cycles per minute) | ||||

| Baseline to Week 4 | 5.9 (4.6 to 7.1) | <0.0001 | 4.1 (2.5 to 5.8) | <0.0001 |

| Week 4 to Week 8 | 3.9 (2.7 to 5.2) | <0.0001 | 1.8 (0.1 to 3.5) | 0.46 |

| Week 8 to Week 12 | 2.8 (1.6 to 4.0) | 0.0001 | 0.1 (−1.5 to 1.8) | 0.99 |

| Week 12 to Week 16 | 0.9 (−0.4 to 2.1) | 0.97 | 1.6 (−0.1 to 3.2) | 0.71 |

| Baseline to Week 16 | 13.5 (12.2 to 14.7) | <0.0001 | 7.6 (6.0 to 9.3) | <0.0001 |

Change is computed as the mean value for the later visit minus the mean value for the earlier visit.

CI = confidence interval.

TABLE 4.

Treatment group difference at each time point

| Accommodative Amplitude (diopters) |

Accommodative Facility (cycles per minute) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Point | Difference† (95% CI) | P value | Difference† (95% CI) | P value |

| Baseline | 0.4 (−1.5 to 2.3) | 0.99 | 0.1 (−1.7 to 2.0) | 0.99 |

| Week 4 | 3.5 (1.6 to 5.3) | 0.0045 | 1.9 (0 to 3.7) | 0.58 |

| Week 8 | 4.5 (2.6 to 6.4) | <0.0001 | 4.0 (2.1 to 5.8) | 0.0005 |

| Week 12 | 3.8 (1.9 to 5.6) | 0.0015 | 6.7 (4.9 to 8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Week 16 | 3.9 (2.1 to 5.8) | 0.0007 | 6.0 (4.1 to 7.8) | <0.0001 |

Difference is computed as the mean value for the vergence/accommodative therapy group minus the mean value for the placebo therapy group at each time point.

CI = confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Mean accommodative amplitude and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for participants with decreased accommodative amplitude at baseline, by study visit and treatment group.

The proportion of participants reaching the normal age-expected amplitude by time point is shown in Table 5. The proportion of participants who attained a normal amplitude of accommodation was significantly greater in the vergence/accommodative therapy group than in the placebo therapy group with a treatment group difference of 36% (95% CI: 22 to 51%; P < 0.0001).

TABLE 5.

Proportion of participants reaching normal accommodative amplitude or facility by treatment group at each time point

| Vergence/Accommodative % (95% CI) |

Placebo % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Time Point | Normal Accommodative Amplitude † | |

| Week 4 | 47% (37% to 56%) | 19% (10% to 30%) |

| Week 8 | 58% (49% to 68%) | 23% (13% to 35%) |

| Week 12 | 63% (53% to 72%) | 35% (24% to 48%) |

| Week 16 | 69% (59% to 77%) | 32% (21% to 45%) |

| Time Point | Normal Accommodative Facility ‡ | |

| Week 4 | 36% (25% to 49%) | 14% (5% to 29%) |

| Week 8 | 68% (56% to 79%) | 39% (23% to 57%) |

| Week 12 | 87% (77% to 94%) | 35% (20% to 53%) |

| Week 16 | 85% (74% to 93%) | 49% (32% to 66%) |

Normal accommodative amplitude defined as amplitude ≥ 14 diopters.

Normal accommodative facility defined as facility ≥ 11 cycles per minute.

95% CI = confidence interval.

We evaluated the trajectory of change in the vergence/accommodative therapy group. Because most of the improvement in amplitude occurred by week 4, the timeframes of baseline to week 4 and of weeks 4 to 16 were selected for this post-hoc analysis. Accommodative amplitude increased at an average rate of 1.5 D per week (P < 0.0001) during the first 4 weeks and then increased at a slower, but statistically significant average rate of 0.2 D per week from weeks 4 to 16 (P = 0.0018).

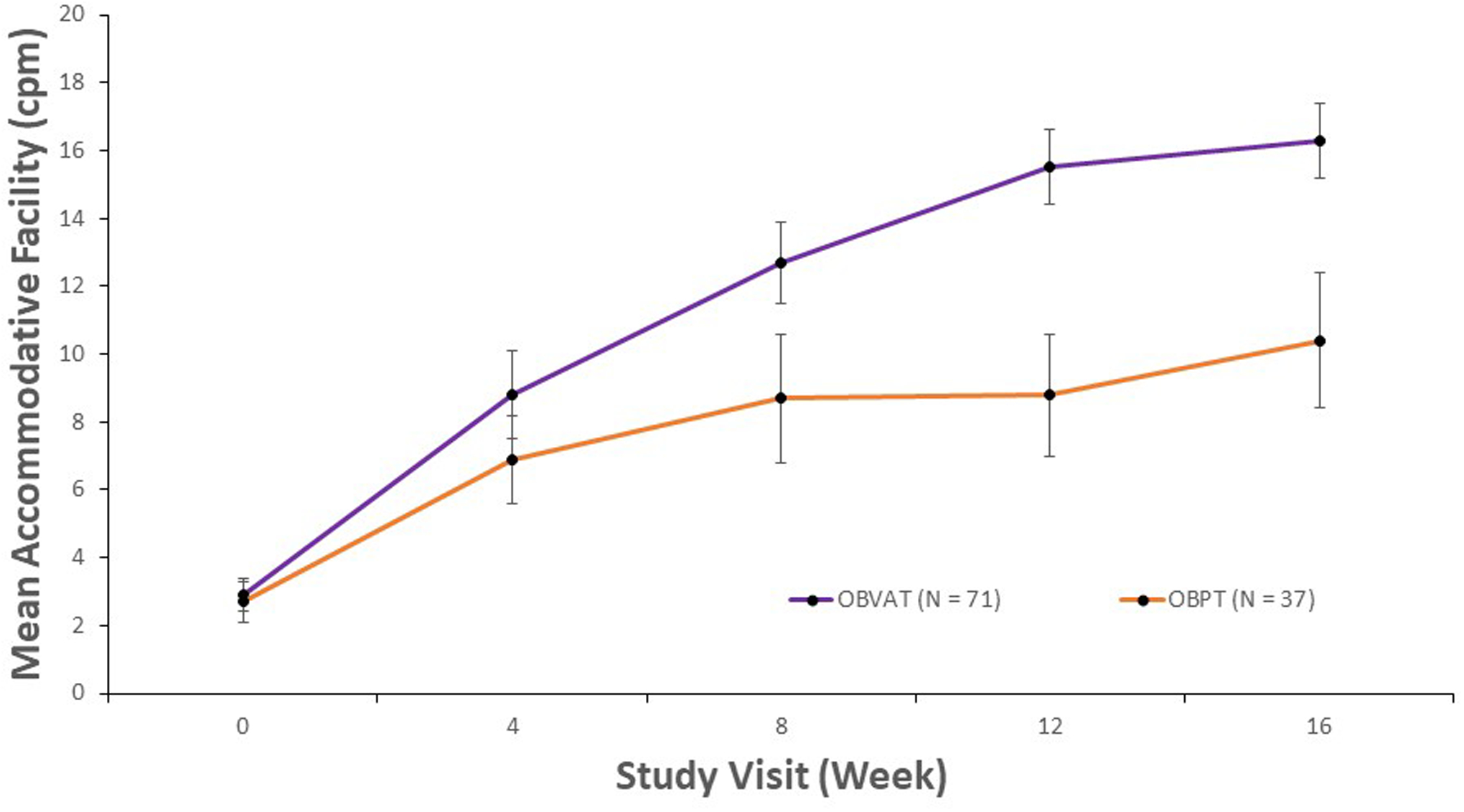

Changes in Accommodative Facility

From baseline to week 16, mean accommodative facility improved from 2.9 cpm to 16.4 cpm in the vergence/accommodative therapy group (P < 0.0001) and from 2.7 cpm to 10.3 cpm in the placebo therapy group (P < 0.0001). The total mean improvement in accommodative facility was significantly greater in the participants treated with vergence/accommodative therapy than the participants treated with placebo therapy, with a treatment group difference of 6.0 cpm (95% CI: 3.8 to 7.9 cpm; P < 0.0001). Table 3 shows the mean change and 95% CI’s in accommodative facility between follow-up visits. In the vergence/accommodative therapy group, a statistically significant improvement in accommodative facility was found between each time interval from baseline to the 12-week visit. In the placebo therapy group, the greatest increase in facility occurred between baseline and the 4-week visit, followed by small and statistically insignificant improvements after that. While the mean accommodative facility measures did not differ between the vergence/accommodative and placebo therapy groups at week 4, facility was significantly better in the vergence/accommodative therapy compared with placebo therapy at weeks 8, 12, and 16 (Table 4, Figure 2). The sensitivity analysis that controlled for age yielded results that were essentially the same (data not shown) as the original results.

Figure 2.

Mean accommodative facility and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for participants with decreased accommodative facility at baseline, by study visit and treatment group.

The proportions of participants reaching the normal accommodative facility in both groups are shown in Table 5. A significantly greater proportion of participants in the vergence/accommodative therapy group met the criterion for normal facility compared with the placebo therapy group what a treatment group difference of 36% (95% CI: 18 to 55%; P < 0.0001).

Regarding the rate of change in accommodative facility for the participants assigned to the vergence/accommodative therapy, accommodative facility increased at mean rate of 1.46 cpm per week during the first 4 weeks (P < 0.0001), then slowed to a mean rate of 0.63 cpm per week from weeks 4 to 16 (P < 0.0001).

DISUSSION

The CITT-ART placebo-controlled randomized trial demonstrated that office-based vergence/accommodative therapy is an effective treatment for improving accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and coexisting accommodative dysfunction. On average, accommodative amplitude improved 8.6 D with a resultant mean amplitude of 16.2 D and accommodative facility improved 13.5 cpm with resultant mean facility of 16.4 cpm.

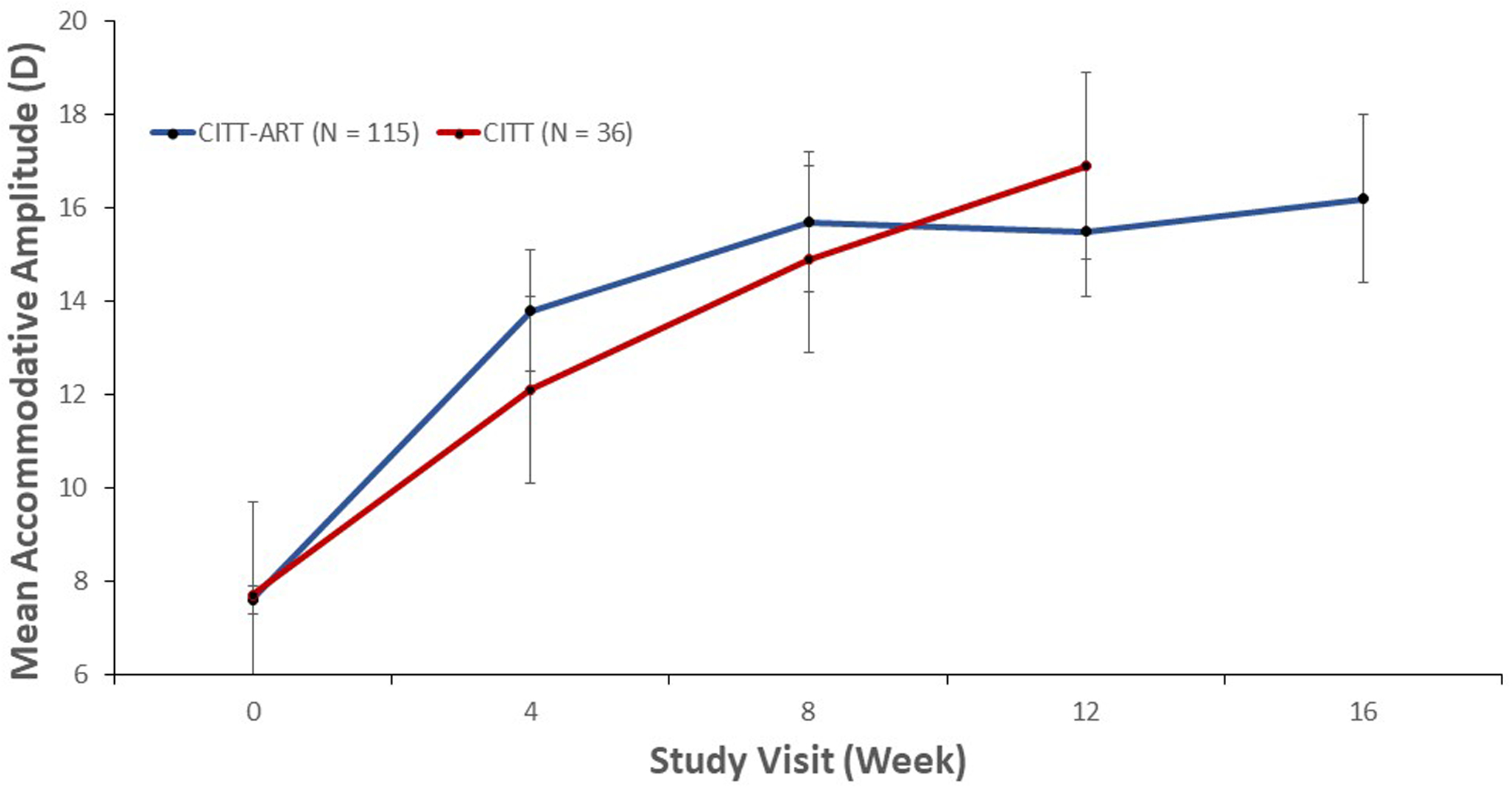

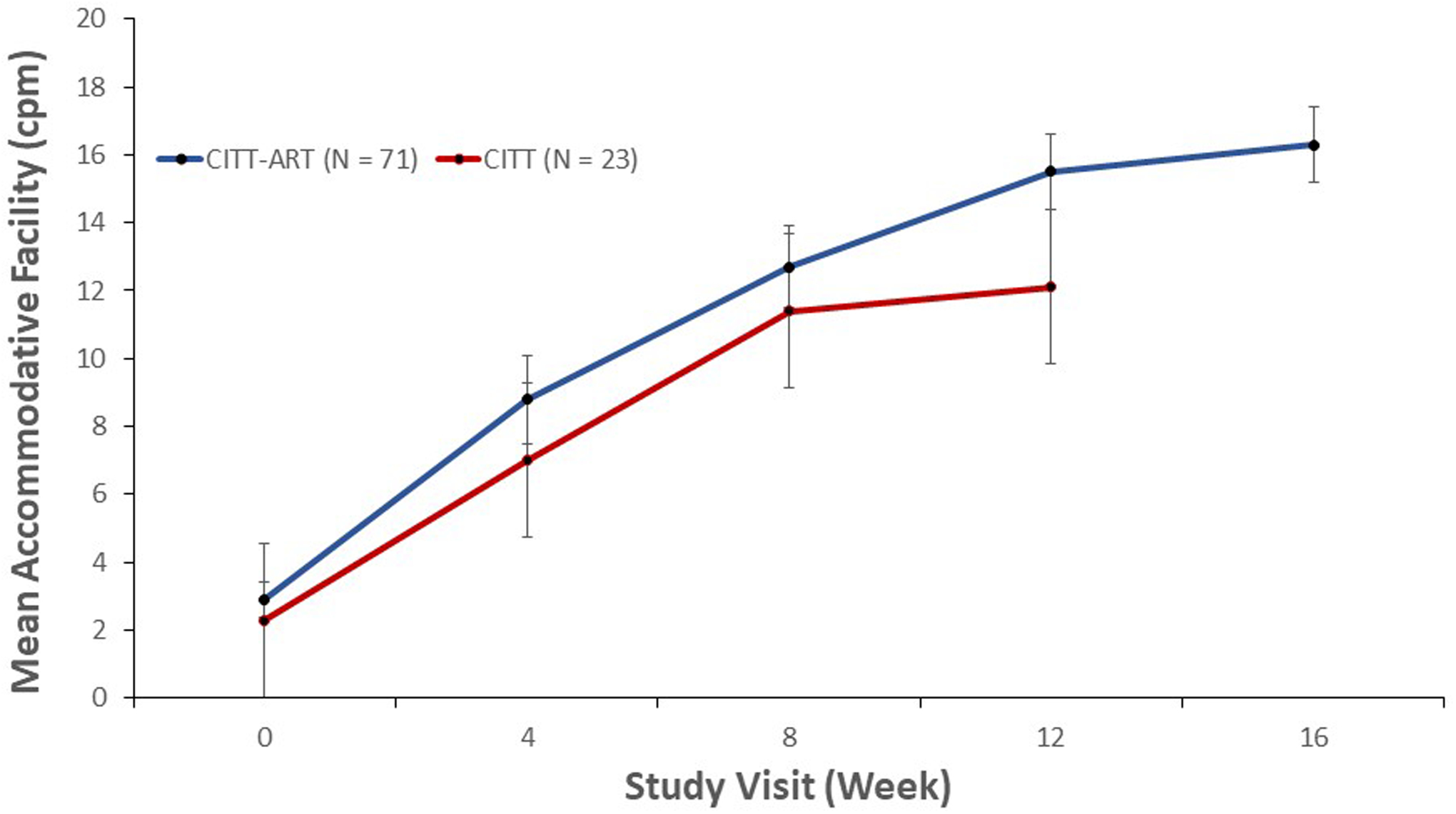

Our study is not the first to report that accommodative dysfunction in children can be effectively treated with vision therapy; however, most prior studies have been retrospective, had small sample sizes, and/or were conducted without a control group.15,30,31 We can, however, compare our results with the CITT study, which was a randomized controlled trial with only minor protocol differences.8 Our current study shared the same inclusion criteria as CITT except that in the current study, the criterion for decreased accommodative amplitude was based on contemporary data from two recent school-based studies,23,24 rather than from Hofstetter’s formula,32 which was outdated and based on the assumption that change in accommodative amplitude with age is linear. The therapy programs in both studies were identical except that the current study was 4 weeks longer in duration and included three additional bi-ocular accommodative therapy techniques (stereoscope bi-ocular facility, prism dissociation bi-ocular facility, and computer orthopter bi-ocular facility) that were not in the CITT. The mean improvement in accommodative amplitude in the current study (8.6 D) was comparable to that of CITT (9.9 D) (Figure 3). There was a greater improvement in accommodative facility in the current study than in the CITT (13.5 versus 9 cpm; Figure 4), but we cannot attribute this difference to the additional 4 weeks of treatment because the improvement from weeks 12 to 16 was only 0.9 cpm.

Figure 3.

Mean accommodative amplitude (D) for participants with decreased accommodative amplitude at baseline, treated with accommodative/vergence therapy, by study visit in CITT and CITT-ART.

Figure 4.

Mean accommodative facility (cpm) for participants with decreased accommodative facility at baseline, treated with vergence/accommodative therapy by study visit in CITT and CITT-ART.

We also investigated the impact of the additional 4 weeks of therapy in the current study. Similar to the just-noted small improvement (0.9 cpm) in accommodative facility, we found that a minimal improvement in accommodative amplitude (0.9 D) occurred between weeks 12 and 16. This suggests that the last 4 weeks of the therapy protocol provided little added benefit in improving accommodative function. However, given that the therapy regimen was designed to treat convergence insufficiency rather than accommodative dysfunction, the emphasis of the therapy program during the last 4 weeks was on vergence procedures with minimal accommodative therapy.

In evaluating the rate of improvement in accommodative function in the vergence/accommodative therapy group, the largest gains occurred during the first 4 weeks of therapy. This was particularly true for accommodative amplitude. Of the eventual 8.6 D mean improvement, 71% of that gain had occurred by the week 4 visit and 94% by the week 8 visit. In contrast, accommodative facility had improved by only 44% and 73% of its eventual mean gain of 13.5 cpm after 4 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively. This chronology of events is consistent with the sequencing of the accommodative therapy procedures in the treatment program. The initial phase of therapy consisted of procedures designed to improve accommodative amplitude, with emphasis on awareness of accommodative effort when viewing small size print at progressively closer working distances or through progressively higher powers of minus lenses. As the participants showed improved accommodative amplitude, accommodative facility therapy procedures were implemented to improve the speed and accuracy of accommodation (i.e., alternating looking through plus and minus lenses to relax and stimulate accommodation as quickly as possible).

Strengths of this study include random assignment to treatment groups prospectively, inclusion of a placebo control, masking of examiners and participants to avoid bias, a standardized treatment protocol, and a high retention rate. The study is not without limitations, however. The trial was designed to investigate the effectiveness of a therapy regimen in treating children with convergence insufficiency who might or might not have had associated accommodative dysfunction; thus, the observed treatment effect may not represent what is obtained in the treatment of children with simply an accommodative dysfunction. Furthermore, the impact of improved accommodative function on other parameters such as symptoms cannot be assessed. In addition, it is possible that therapy regimens of shorter or longer duration, or comprised of different procedures, might have yielded different results. Another consideration is that there could be misclassifications that affected the proportions of participants who achieved the criteria for “normal” accommodative function given that a binary outcome measure was created from a continuous measure. Nonetheless, this would not affect the treatment group comparisons. Finally, there is uncertainty in how much, if any, of the improvement found in the placebo therapy group represents a beneficial clinical effect. The results of several meta-analyses of clinical trials, including the latest Cochrane review33 that analyzed clinical trials with patients randomly allocated to a placebo group and a no-treatment group concluded that placebo interventions generally do not produce important clinical effects and major health benefits. Rather, improvements seen in placebo treatment groups are reported to be mostly from a combination of factors including regression to the mean, spontaneous remission, the natural course of the disease, and other factors such as patient-provider relationship effects.34–36 Because these factors affect both treatment groups, it is only when there is a no-treatment arm that one can ascertain the influence these factors have for an individual trial. Nevertheless, in a comparative effectiveness trial where participants are randomly allocated to treatment groups such as in the present study, both groups should be equally affected by regression to the mean and other unknown factors. Thus, it is the treatment group differences that are of primary importance.

In conclusion, office-based vergence/accommodative therapy was found to be an effective treatment for improving accommodative amplitude and accommodative facility in children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency and coexisting accommodative dysfunction. The change in accommodative function suggests that 12 weeks of the protocolized CITT-ART therapy regimen ameliorates accommodative dysfunction with convergence insufficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial – Attention & Reading Trial Investigator Group Clinical Sites

Sites are listed in order of the number of participants enrolled in the study, with the number enrolled listed in parentheses preceded by the clinical site name and location. Personnel are listed as (PI) for principal investigator, (SC) for coordinator, (ME-ART) for masked examiner or attention and reading testing, (ME-VIS) for masked examiner for visual function testing, (VT) for vision therapist, and (UnM) for unmasked examiners for baseline testing.

Study Center: SUNY College of Optometry (45)

Jeffrey Cooper, MS, OD (PI 06/14 – 04/15); Erica Schulman, OD (PI 04/15 - present); Kimberly Hamian, OD (ME-VIS); Danielle Iacono, OD (ME-VIS); Steven Larson, OD (ME-ART); Valerie Leung, Boptom (SC); Sara Meeder, BA (SC); Elaine Ramos, OD (ME-VIS); Steven Ritter, OD (VT); Audra Steiner, OD (ME-VIS); Alexandria Stormann, RPA-C (SC); Marilyn Vricella, OD (UnM); Xiaoying Zhu, OD (ME-VIS)

Study Center: Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (44)

Susanna Tamkins, OD (PI); Naomi Aguilera, OD (VT); Elliot Brafman, OD (ME-VIS); Hilda Capo, MD (ME-VIS); Kara Cavuoto, MD (ME-VIS); Isaura Crespo, BS (SC); Monica Dowling, PhD (ME-ART); Kristie Draskovic, OD (ME-VIS); Miriam Farag, OD (VT); Vicky Fischer, OD (VT); Sara Grace, MD (ME-VIS); Ailen Gutierrez, BA (SC); Carolina Manchola-Orozco, BA (SC); Maria Martinez, BS (SC); Craig McKeown, MD (UnM); Carla Osigian, MD (ME-VIS); Tuyet-Suong Pham, OD (VT); Leslie Small, OD (ME-VIS); Natalie Townsend, OD (ME-VIS)

Study Center: Pennsylvania College of Optometry (43)

Michael Gallaway, OD (PI); Mark Boas, OD, MS (VT); Christine Calvert, Med (ME-ART); Tara Franz, OD (ME-VIS); Amanda Gerrouge, OD (ME-VIS); Donna Hayden, MS (ME-ART); Erin Jenewein, OD,MS (VT); Zachary Margolies, MSW, LSW (ME-ART); Shivakhaami Meiyeppen, OD (ME-VIS); Jenny Myung, OD (ME-VIS); Karen Pollack, (SC), Mitchell Scheiman, OD, PhD (ME-VIS); Ruth Shoge, OD (ME-VIS); Andrew Tang, OD (ME-VIS); Noah Tannen, OD (ME-VIS); Lynn Trieu, OD, MS (VT); Luis Trujillo, OD (VT)

Study Center - The Ohio State University College of Optometry (40)

Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (PI); Michelle Buckland, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Allison Ellis, BS, MEd (ME-ART); Jennifer Fogt, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Catherine McDaniel, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Taylor McGann, OD (ME-VIS); Ann Morrison, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Shane Mulvihill, OD, MS (VT); Adam Peiffer, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Maureen Plaumann, OD (ME-VIS); Gil Pierce, OD, PhD (ME-VIS); Julie Preston, OD, PhD, MEd (ME-ART); Kathleen Reuter, OD (VT); Nancy Stevens, MS, RD, LD (SC); Jake Teeny, MA (ME-ART); Andrew Toole, OD, PhD (VT); Douglas Widmer, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Aaron Zimmerman, OD, MS (ME-VIS)

Study Center: Southern California College of Optometry (38)

Susan Cotter, OD, MS (PI); Carmen Barnhardt, OD, MS (VT); Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd (ME-ART); Angela Chen, OD, MS (VT); Raymond Chu, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Kristine Huang, OD, MPH (ME-VIS); Susan Parker (SC); Dashaini Retnasothie (UnM); Judith Wu (SC)

Study Center: Akron Childrens Hospital (34)

Richard Hertle, MD (PI); Penny Clark (ME-ART); Kelly Culp, RN (SC); Kathy Fraley CMA/ASN (ME-ART); Drusilla Grant, OD (VT); Nancy Hanna, MD (UnM); Stephanie Knox (SC); William Lawhon, MD (ME-VIS); Lan Li, OD (VT); Sarah Mitcheff (ME-ART); Isabel Ricker, BSN (SC); Tawna Roberts, OD (VT); Casandra Solis, OD (VT); Palak Wall, MD (ME-VIS), Samantha Zaczyk, OD (VT)

Study Center: UAB School of Optometry (32)

Kristine Hopkins, OD (PI 12/14 - present); Wendy Marsh-Tootle, OD, MS (PI 06/14 – 2/14); Michelle Bowen, BA (SC); Terri Call, OD (ME-VIS); Kristy Domnanovich, PhD (ME-ART); Marcela Frazier, OD MPH (ME-VIS); Nicole Guyette, OD, MS (ME-ART); Oakley Hayes, OD, MS (VT); John Houser, PhD (ME-ART); Sarah Lee, OD, MS (VT); Jenifer Montejo, BS (SC); Tamara Oechslin, OD, MS (VT); Christian Spain (SC); Candace Turner, OD (ME-ART); Katherine Weise, OD, MBA (ME-VIS)

Study Center: NOVA Southeastern University (31)

Rachel Coulter, OD (PI); Deborah Amster, OD (ME-VIS); Annette Bade, OD, MCVR (SC); Surbhi Bansal, OD (ME-VIS); Laura Falco, OD (ME-VIS); Gregory Fecho, OD (VT); Katherine Green, OD (ME-VIS); Gabriela Irizarry, BA (ME-ART); Jasleen Jhajj, OD (VT); Nicole Patterson, OD, MS (ME-ART); Jacqueline Rodena, OD (ME-VIS); Yin Tea, OD (VT); Julie Tyler, OD (SC); Dana Weiss, MS (ME-ART); Lauren Zakaib, MS (ME-ART)

Study Center: Advanced Vision Care (15)

Ingryd Lorenzana, OD (PI); Yesena Meza (ME-VIS); Ryan Mann (ME-ART); Mariana Quezada, OD (VT); Scott Rein, BS (ME-ART); Indre Rudaitis, OD (ME-VIS); Susan Stepleton, OD (ME-VIS); Beata Wajs (VT)

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD

Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH

CITT-ART Executive Committee

Mitchell Scheiman, OD, PhD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS; Richard Hertle, MD; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Carolyn Denton, PhD; Eugene Arnold, MD; Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd; Christopher Chase, PhD

CITT-ART Reading Center

Carolyn Denton, PhD (PI); Sharyl Wee (SC); Katlynn Dahl-Leonard (SC); Kenneth Powers (Research Assistant); Amber Alaniz (Research Assistant)

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

Marie Diener-West, PhD, Chair; William V. Good, MD; David Grisham, OD, MS, FAAO; Christopher J. Kratochvil, MD; Dennis Revicki, PhD; Jeanne Wanzek, PhD

CITT-ART-Study Chair

Mitchell Scheiman, OD, PhD (study chair); Karen Pollack (study coordinator); Susan Cotter, OD, MS; (vice chair); Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (vice chair)

CITT-ART Data Coordinating Center

G Lynn Mitchell, MAS (PI); Mustafa Alrahem (Student worker); Julianne Dangelo, BS (Program Assistant); Jordan Hegedus (Student worker); Ian Jones (Student worker); Lisa A Jones-Jordan, PhD (Epidemiologist); Alexander Junglas (Student worker); Jihyun Lee (Programmer); Jadin Nettles (Student worker); Curtis Mitchell (Student worker); Mawada Osman (Student worker); Gloria Scott-Tibbs, BA (Project Coordinator); Loraine Sinnott, PhD (Biostatistician); Chloe Teasley (Student worker); Victor Vang (Student worker); Robin Varghese (Student worker)

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by National Eye Institute of National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (grant number 5U10EY022599 to MMS, 5U10EY022601 to GLM, 5U10EY022595 to SC, 5U10EY022592 to MK, 5U10EY022586 to ES, 5U10EY022600 to RH, 5U10EY022587 to MG, 5U10EY022596 to RC, 5U10EY022594 to KH, and 5U10EY022591 to ST). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

A complete list of participating members of the CITT-ART Investigator Group can be found in the Acknowledgement.

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned in this article.

Meeting presentation: This manuscript was presented in part at the American Academy of Optometry Annual Meeting (November 2019 in Orlando, FL).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hussaindeen JR, Rakshit A, Singh NK, et al. Prevalence of non-strabismic anomalies of binocular vision in Tamil Nadu: report 2 of BAND study. Clin Exp Optom 2017;100:642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wajuihian SO, Hansraj R. Accommodative Anomalies in a Sample of Black High School Students in South Africa. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang JU, Park IJ. Prevalence of general binocular dysfunctions among rural schoolchildren in South Korea. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2015;5:177–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daum K. Accommodative dysfunction. Doc Ophthalmol 1983;61:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hennessey D, Iosue R, Rouse M. Relation of symptoms to accommodative infacility of school-aged children. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1984:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine S, Ciuffreda K, Selenow A, Flax N. Clinical assessment of accommodative facility in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. J Am Optom Assoc 1984;56:286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman L, Rouse M. Referral recommendations for binocular function and/or developmental perceptual deficiencies. J Am Optom Assoc 1980;51:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheiman M, Cotter S, Kulp M, et al. Treatment of accommodative dysfunction in children: results from a randomized clinical trial. Optom Vis Sci 2011;88:1343–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borsting E, Rouse M, Deland P, et al. Association of symptoms and convergence and accommodative insufficiency in school-age children. Optometry 2003;74:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis A, Harvey E, Twelker J, Miller J, Leonard-Green T, Campus I. Convergence insufficiency, accommodative insufficiency, visual symptoms, and astigmatism in Tohono O’odham students. J Ophthalmol 2016;2963976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brautaset R, Wahlberg M, Abdi S, Pansell T. Accommodation Insufficiency in Children: Are Exercises Better than Reading Glasses? Strabismus 2008;16:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper JS, Burns CR, Cotter SA, Daum KM, Griffin JR, Scheiman MM. Optometric Clinical Practice Guidline Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction. St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterner B, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrom A. Accommodative facility training with a long term follow up in a sample of school aged children showing accommodative dysfunction. Doc Ophthalmol 1999;99:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterner B, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrom A. The effects of accommodative facility training on a group of children with impaired relative accommodation - a comparison between dioptric treatment and sham treatment. Ophthal Physiol Opt 2001;21:470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouse MW. Management of binocular anomalies: efficacy of vision therapy in the treatment of accommodative deficiencies. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987;64:415–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CITT-ART Investigator Group. Treatment of Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children Enrolled in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial-Attention & Reading Trial: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CITT-ART Investigator Group. Effect of Vergence/Accommodative Therapy on Reading in Children with Convergence Insufficiency: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:836–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheard C. Zones of ocular comfort. Am J Optom 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity of the convergence insufficiency symptom survey: a confirmatory study. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9 to 18 years. Optom Vis Sci 2003;80:832–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. Randomized clinical treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1336–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashemi H, Nabovati P, Khabazkhoob M, Yekta A, Emamian MH, Fotouhi A. Does Hofstetter’s equation predict the real amplitude of accommodation in children? Clin Exp Optom 2018;101:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castagno VD, Vilela MA, Meucci RD, et al. Amplitude of Accommodation in Schoolchildren. Curr Eye Res 2017;42:604–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zellers JA, Alpert TL, Rouse MW. A review of the literature and a normative study of accommodative facility. J Am Optom Assoc 1984;55:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CITT-ART Investigator Group, Scheiman M, Mitchell G, et al. Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial - Attention and Reading (CITT-ART): Design and Methods. Vis Dev Rehabil 2015;1:214–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin J, Borsting E. Binocular Anomalies Theory, Testing & Therapy 5th Ed. Santa Ana, CA: Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Šidák Z. Rectangular Confidence Regions for the Means of Multivariate Normal Distributions. J Am Stat Assoc 1967;62:626–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman L, Cohen A, Feuer G. Effectiveness of non-strabismus optomtric vision training in a private practice. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1973;50:813–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wold RM, Pierce JR, Keddington J. Effectiveness of optometric vision therapy. J Am Optom Assoc 1978;49:1047–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofstetter H. Using age-amplitude formula. Opt World 1950;38:42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2010;2010:Cd003974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morton V, Torgerson DJ. Regression to the mean: treatment effect without the intervention. J Eval Clin Pract 2005;11:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krogsbøll LT, Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Spontaneous improvement in randomised clinical trials: meta-analysis of three-armed trials comparing no treatment, placebo and active intervention. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]