Abstract

PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression, yet their molecular functions in neurobiology are unclear. While investigating neurodegeneration mechanisms using human α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg pan-neuronal overexpressing strains, we unexpectedly observed dysregulation of piRNAs. RNAi screening revealed that knock down of piRNA biogenesis genes improved thrashing behavior; further, a tofu-1 gene deletion ameliorated phenotypic deficits in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains. piRNA expression was extensively downregulated and H3K9me3 marks were decreased after tofu-1 deletion in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. Dysregulated piRNAs targeted protein degradation genes suggesting that a decrease of piRNA expression leads to an increase of degradation ability in C. elegans. Finally, we interrogated piRNA expression in brain samples from PD patients. piRNAs were observed to be widely overexpressed at late motor stage. In this work, our results provide evidence that piRNAs are mediators in pathogenesis of Lewy body diseases and suggest a molecular mechanism for neurodegeneration in these and related disorders.

Subject terms: Diseases of the nervous system, Molecular neuroscience

piRNAs are small noncoding RNAs whose biological functions are not fully understood. Here, the authors demonstrate using C. elegans genetic models that dysregulated piRNAs are associated with protein degradation processes in a model of Lewy body disease.

Introduction

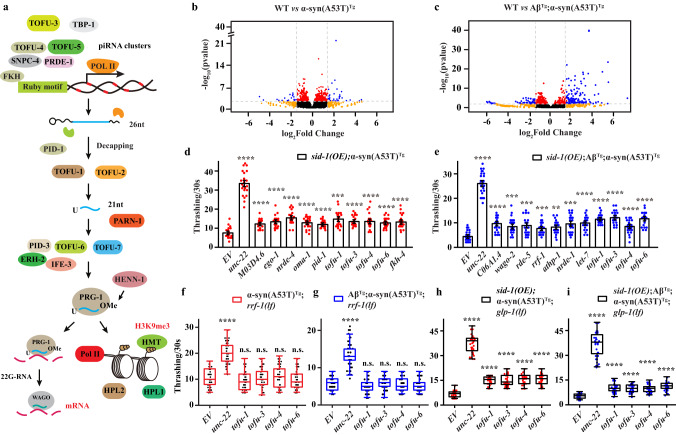

piRNAs are small noncoding RNAs derived from single-stranded precursor transcripts expressed in piRNA clusters located in intergenic regions of the genome1,2. piRNA biogenesis begins with transcription of primary piRNAs, which are then shortened by RNA exonucleases at both 5’ and 3’ ends with a preference for a 5’ U residue, and are then 3’ nucleotide 2’O-methylated (Fig. 1a). This results in 26–30 nucleotide (nts) piRNAs in Drosophila and vertebrates, and 21 nts in C. elegans (21U-RNA)3. A forward genetic screen for factors involved in C. elegans piRNA biogenesis uncovered several tofu (Twenty-One-Fouled Ups) genes that greatly perturbed 21U-RNA production4. TOFU-1 and TOFU-2 knock down led to precursor 21U (pre-21U) accumulation suggesting that they are involved in downstream processing. TOFU-3,-4,-5 knock down led to a lack of 21U-RNA suggesting they are also required for piRNA precursor transcription. TOFU-6 and TOFU-7 affect mature levels of 21U-RNAs without affecting precursor levels suggesting they are involved in the loading of piRNAs to PRG-15.

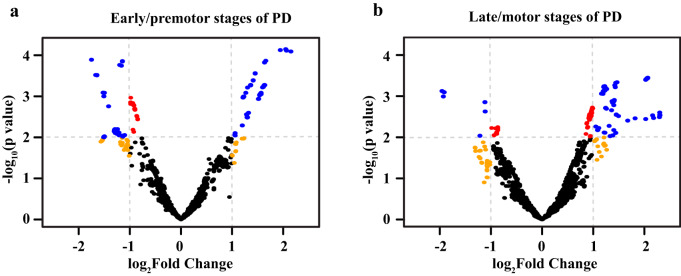

Fig. 1. RNAi screening in transgenic animals.

a Schematic diagram of piRNA biogenesis in C. elegans. b, c Volcano plot of piRNAs expression in small RNA-Seq. Red dots, P value < 0.01, FDR < 0.05; orange dots, |log2(fold change)| > 1.5; blue dots, P value < 0.01, FDR < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| > 1.5; black dots, P value ≥ 0.01, FDR ≥ 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| ≤ 1.5. d, e Thrashing assay in young adult stage of sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg and sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains under different RNAi clones (n ≥ 12 for each clone). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. f–i Thrashing assay in the young adult stage of different strains under tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 RNAi clones (n ≥ 12 for each clone). The box plots display the median, upper, and lower quartiles; the whiskers show a 1.5× interquartile range (IQR). For (d–i), each dot represents one nematode. EV was an empty vector (negative control), and unc-22 was a positive control in the RNAi screen. p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA analysis. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, n.s. not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Primary piRNAs bind PIWI proteins and undergo secondary amplification known as the “Ping-Pong” cycle in Drosophila and mammals6. While in C. elegans, piRNAs bind with PRG-1, and secondary siRNAs are generated via RNA dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps)4. Fully processed and amplified piRNAs bind PIWI proteins to form mature piRNA-PIWI complexes that regulate transposable elements or cellular gene expression4. piRNAs repress gene expression mainly through post-transcriptional silencing by inducing 22G-RNA biogenesis and silencing mRNA transcripts directly or initiate transcriptional silencing by inducing chromatin modification, such as repressive histone mark formation or DNA methylation7,8. Accumulating evidence suggests that PIWI/piRNAs are broadly expressed in the nervous system and participate in neuronal processes as well as neuronal disorders9. The Piwi/piRNA complex promotes serotonin-dependent methylation in the CREB2 promoter in Aplysia, which enhances long-term synaptic facilitation10. piRNAs target neuronal mRNAs, which regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis11. In addition, a neuronal piRNA pathway was found to inhibit axon regeneration in C. elegans12. piRNA not only regulates memory formation but also induces transgenerational inheritance of learning pathogen avoidance behavior to the offspring in C. elegans13,14. Loss of condensation of heterochromatin and depletion of piRNAs can drive transposable element dysregulation, which is a driver for tauopathy neurodegeneration15. Together, these studies provide an emerging concept of piRNAs as an important regulator in the maintenance and function of neuronal processes.

Amyloid β (Aβ) and α-synuclein (α-syn) represent two of the key proteins found in lesions associated with age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), respectively16. Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Lewy body Dementia (LBD) are two neurodegenerative disorders related to Lewy body formation and accumulation, which leads to persistent movement deficits and worsens over time17. Currently, there is no effective treatment for PD and LBD. Our lab previously produced PD and LBD models in C. elegans, which overexpressed human α-syn(A53T) pan-neuronally for the PD model and co-expressed human Aβ and α-syn(A53T) pan-neuronally for the LBD model (transgenic lines of α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg), respectively18,19. Both of these models displayed dopaminergic neuronal loss and motor deficits, which allowed us to explore the pathogenesis of PD and LBD18,19.

The role of piRNAs in neurobiology is less well understood. We previously observed that piRNAs were dysregulated in α-syn(A53T)Tg animals as part of a study to characterize changes in the small noncoding RNA landscape during neurodegeneration20. In that study, we described our initial observation and did not investigate the mechanism.

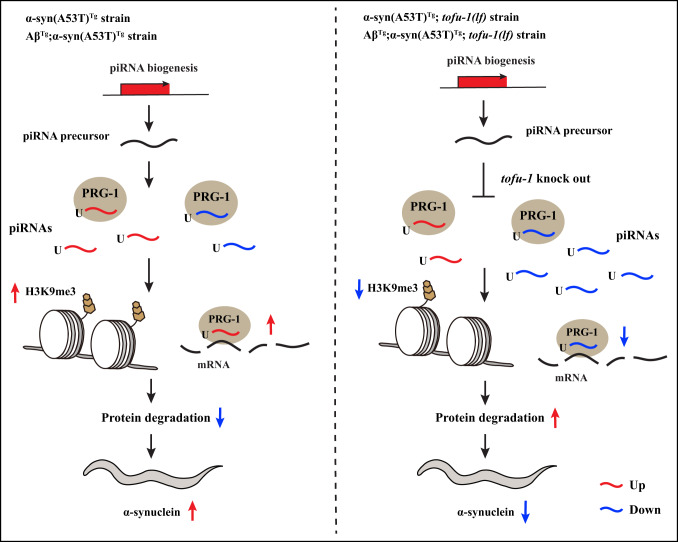

In this work, we hypothesize that piRNAs are dysregulated and aggravate neuronal loss in Lewy body diseases. Here we find that piRNAs are dysregulated in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals and are mainly upregulated in these strains. When we knock down piRNA biogenesis genes, we observe an improvement in movement in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, suggesting a role for piRNAs in mediating neurodegeneration. We further cross these model strains with a tofu-1 null mutant to explore the function of piRNAs in Lewy body related diseases. TOFU-1 loss of function mutation (lf) in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains ameliorate the behavioral phenotypes and improve thrashing, extend lifespan, and reduce α-syn expression while alleviating the dopaminergic neuron degeneration. piRNAs are broadly downregulated after tofu-1 deletion. Furthermore, these piRNAs require PRG-1 to regulate thrashing deficits, and the repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 increase in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, while decreasing after tofu-1 deletion in transgenic animals. piRNA mainly targets protein degradation genes, which lead to α-syn accumulation, whereas decreases of piRNA expression increases the protein degradation ability in C. elegans. We further find that piRNAs are aberrantly expressed in PD patient brains and are mainly overexpressed in the late motor stage, suggesting that piRNA dysregulation might be conserved from C. elegans to humans. We thus provide insights to explain the roles of piRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases related with protein degradation, suggesting that piRNAs are one of the key components in mediating neuropathology in Lewy body diseases. These findings indicate a pathway to explore treatment and biomarker development for neuropathology involved in Lewy body diseases.

Results

piRNAs dysregulation in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains

In order to explore how small RNAs regulate pathogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases, we used small RNA-Seq to identify changes of small RNAs in our PD and LBD models, which overexpressed human α-syn(A53T) and Aβ;α-syn(A53T) pan-neuronally in C. elegans. To our surprise, we found that piRNAs were dysregulated both in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains and some of the piRNAs were overexpressed in these two models. For the α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strain, 34 differentially expressed piRNAs (DEPs, |log2fold change | >1.5, P < 0.01 and FDR < 0.05) were identified with 23 DEPs upregulated and 11 DEPs downregulated (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Data 1). These 34 DEPs target 1131 genes. For the AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain, 117 DEPs were identified with 94 DEPs upregulated and only 23 DEPs downregulated (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Data 1). These 117 DEPs target 2338 genes. Three piRNAs (21ur-10824, 21ur-11898, 21ur-13215) were both upregulated in these two models. We used qRT-PCR to confirm some of the piRNA expression changes and these results were consistent with our small RNA-Seq (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Previous studies observed that piRNA expression changes in neurodegenerative diseases9. A study identified massive dysregulated piRNAs in PD derived neuronal cells21. AD patients showed that 103 piRNAs were nominally differentially expressed in the brains and among this change, 81 piRNAs were upregulated and 22 piRNAs were downregulated22. Similarly, another study identified 146 piRNAs that were upregulated and only 3 piRNAs that were downregulated in AD patients23. Based on our sequencing results and these previous data from patients, we speculated that piRNAs were dysregulated in Lewy body diseases.

We hypothesized that if piRNAs were dysregulated and mainly overexpressed in neurodegenerative diseases, a decrease in piRNA expression might improve phenotypes observed in neurodegenerative disease models. To confirm our hypothesis, we used RNAi to knock down piRNA biogenesis genes and determined whether it can improve thrashing in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains. Neurons are highly resistant to exogenous dsRNA in C. elegans, therefore, we overexpressed sid-1(OE) in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains by standard genetic crossing to increase RNAi efficiency24. The biogenesis of type I piRNAs is initiated by fork head (FKH) family transcription factors that recognize the Ruby motif4,9. The 26nt of 21U-RNA precursors generated are exported to cytoplasm, then further modified by TOFU-1, TOFU-2, TOFU-6, TOFU-7 to generate the mature 21U-RNAs in C. elegans (Fig. 1a). The mature 21U-RNAs combine with PRG-1 to form RNA induced silencing complexes (RISC) and induced 22G-RNAs biogenesis to target mRNA directly or cause histone modification to silence gene expression4,9. In our study, we screened 130 genes, which covered most of the small RNAs biogenesis genes in our models (Supplementary Data 2). In the first-round of screening, we identified 19 genes that could improve thrashing in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, and 23 genes in sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (P < 0.01, thrashing > 1.5 fold) (Supplementary Data 2). Among these genes, we performed a second-round of screening and finally confirmed 10 genes that could significantly improve thrashing in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg strains and 11 genes in sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains (P < 0.01, thrashing > 1.5 fold) (Fig. 1d, e). Among these genes, we found that piRNA biogenesis genes tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 can improve thrashing both in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg and sid-1(OE); AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains (Fig. 1d, e). Furthermore, we assayed these genes on locomotion in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg and sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. The results confirmed that knock down of tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 improved movement in our models (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d), suggesting that the piRNAs might be involved in the pathogenesis of Lewy body diseases.

piRNAs were originally discovered in germline cells and act to silence transposable elements, while more recent accumulating evidence suggests that piRNAs are expressed in somatic cells and may participate in neuronal functions9–12. In order to address whether piRNAs improved thrashing behavior independent of germline function, we used tissue specific RNAi in α-syn(A53T)Tg;rrf-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;rrf-1(lf) transgenic strains. Strains with a rrf-1 null mutation are sensitive to RNAi against genes expressed in the germline (some in intestine and hypodermal cells), and rrf-1 loss of function mutation is widely used in RNAi to assess the function of genes specifically in the germline in C. elegans25. Our results showed that knock down of tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 did not improve thrashing in α-syn(A53T)Tg;rrf-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;rrf-1(lf) transgenic animals (Fig. 1f, g). We further crossed sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg and sid-1(OE); AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains with the temperature sensitive strain glp-1(e2141)III, which will lose germline cells after C. elegans are cultivated in 23 °C. We found that knock down of tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 could still improve thrashing in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg;glp-1(lf) and sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;glp-1(lf) in 23°C (Fig. 1h, i). Since piRNAs required PRG-1 to form RISC and previous work showed that prg-1 mRNA is present in somatic cells12; therefore, our results suggested that piRNAs may improve thrashing in somatic cells, which would be independent of germline function.

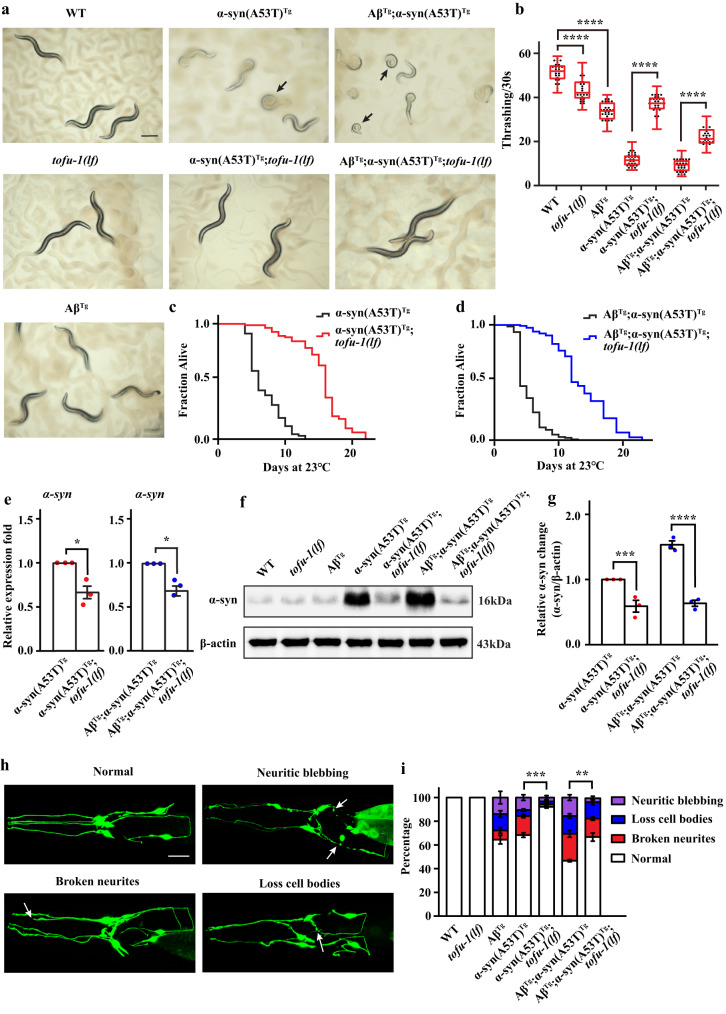

TOFU-1 loss of function mutation ameliorates behavioral impairments in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains

To further confirm that piRNAs are involved in pathogenesis, we focused on TOFU-1. TOFU-1 (21U-RNA biogenesis fouled up) gene was originally identified from forward genetic screens directed towards piRNA biogenesis and function5. It is enriched in neurons and germline in C. elegans5. Since knock down of tofu-1 improves thrashing and locomotion in our transgenic animals, we crossed tofu-1 loss of function mutant (strain tm6424) to α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains to generate the compound transgenic animal α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf). Our results showed that tofu-1 deletion visibly reversed the coiled postures into sinuous shapes both in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains (Fig. 2a). We analyzed images and the results showed that 70.7% ± 1.41 of α-syn(A53T)Tg, 84.2% ± 1.25 of AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg, while 24.8% ± 1.29 of α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf), and 35.9% ± 3.48 of AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) animals (mean ± SEM) showed postural deficits. We then assayed behavioral phenotypes and showed that compared with α-syn(A53T)Tg and Aβ; α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals had significantly improved thrashing rates (Fig. 2b). We also assayed effects on lifespan and observed that tofu-1 loss of function mutation significantly extended lifespan of α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (Fig. 2c, d). Compared with the wild type, tofu-1(lf) mutant also extended lifespan in C. elegans (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Meanwhile, we also checked whether tofu-1 loss of function mutation can improve phenotypes in pan-neuronal expression of Aβ transgenic animal (strain of CL2355). Our results showed that tofu-1(lf) mutation improved learning ability, increased thrashing rate, and decreased Aβ gene expression in the AβTg strain (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d), suggesting that tofu-1 loss of function reversed phenotypes in neurodegenerative disease models in C. elegans.

Fig. 2. TOFU-1 deletion ameliorates behavioral impairments in transgenic animals.

a Transmitted light microscopy images of transgenic animals on agar plates. Black arrows indicate transgenic animals with severe postural deficits. Scale bar = 250 μM. b Thrashing assay of WT and transgenic animals at young adult stage (n ≥ 12 for each group). The box plots display the median, upper, and lower quartiles; the whiskers show 1.5× interquartile range (IQR). c, d The survival curve of transgenic animals (n ≥ 70 for each group). The average lifespan was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier test, P value was calculated by the log-rank test. e Gene expression of α-syn in transgenic animals (mean ± SEM, n = 3). f, g Western blot analysis of α-syn expression in transgenic animals at young adult stage (mean ± SEM, n = 3). h Confocal imaging of normal, neuritic blebbing, broken neurites, and loss cell body in head dopaminergic neurons in transgenic animals. Typical examples are shown. White arrows indicate the location of the lesion. Images were obtained using Zeiss confocal microscope LSM710 at 400× magnification. Scale bar = 20 μM. i Quantitation of dopaminergic neuron lesions on day 8 adults (n ≥ 60 for each group). Statistical analysis was conducted for the normal ratio in dopaminergic neurons in transgenic strains, three biological replicates (mean ± SEM). For (b, g, i), p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA analysis. For (e), p-values were determined by two-tail student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

α-Syn can be observed as protein deposits in PD, while both Aβ and α-syn accumulate in LBD to cause neurodegeneration26,27. Since Aβ did not change while α-syn increases dramatically in LBD models in C. elegans19, we mainly focused on how piRNAs regulate α-syn levels in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. We wondered whether tofu-1 deletion reduced α-syn expression. Our results showed that α-syn was decreased both in mRNA and protein levels in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic strains (Fig. 2e–g). Since monomer α-syn further aggregates into multimer forms, we used native gel electrophoresis to test the different forms of α-syn in transgenic strains. The results showed that tofu-1 deletion not only decreased the monomer but also the polymer form of α-syn in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic strains (Supplementary Fig. 2e). We also assayed Aβ gene expression in the AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain. Our results showed that Aβ levels decreased after tofu-1 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 2f).

Previous studies showed that both α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains had degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, which was mainly caused by α-syn overexpression and accumulation18,19. We further determined whether tofu-1 loss of function mutation improved neurodegeneration in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. Aberrant neurons characterized by broken neurites, shrinking of dendritic endings, neuritic blebbing, and the loss of neuronal cell bodies could be observed (Fig. 2h)28. We observed the neurodegeneration in day 8 adults, while some of the animals were dead in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg, therefore, these surviving animals might have better neuronal morphology than the population average in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. Our results showed that after tofu-1 deletion, dopaminergic neurons showed 92.2% normal morphology in day 8 adults compared to 68.3% normal morphology in the α-syn(A53T)Tg strain, and 66.7% normal morphology in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals compared to only 46.6% normal morphology in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (Fig. 2i). These results suggest that tofu-1 loss of function mutation ameliorated some of the phenotypic deficits and alleviated the dopaminergic neuron degeneration in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals.

TOFU-1 loss of function mutation downregulates piRNAs expression

In order to determine whether tofu-1 deletion decreases piRNAs, we used small RNA-Seq to measure piRNA expression in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains. Compared with wild type, piRNAs were dramatically downregulated in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals. In α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf), 2078 DEPs were downregulated while only 83 DEPs were upregulated (|log2fold change | >1.5, P < 0.01 and FDR < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1). For AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strain, 1598 DEPs were downregulated, and 55 DEPs were upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1). These results showed that tofu-1 deletion significantly downregulated piRNA expression in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic strains. Since tofu-1 is one of the piRNA biogenesis genes, we also measured piRNA expression in tofu-1(lf) mutant. Results confirmed that tofu-1 deletion significantly downregulated piRNAs expression with 1913 DEPs downregulated and only 88 DEPs upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1).

We made a further comparison between α-syn(A53T)Tg and α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains, AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains. Our results confirmed that tofu-1 loss of function mutation significantly downregulated piRNA expression. In α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strain, 1967 DEPs were downregulated, and 88 DEPs were upregulated compared to α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1). For AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strain, 971 DEPs were downregulated and only 27 DEPs were upregulated compared to AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 1). We found one piRNA (21ur-3554) that was upregulated in WT vs. α-syn(A53T)Tg and downregulated in WT vs. α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf), and three piRNAs (21ur-6799, 21ur-8461, 21ur-7000) that were upregulated piRNAs in WT vs. AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg and downregulated in WT vs. AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf).

TOFU-1 is involved in piRNA processing by enhancing the conversion of the precursor 21U (pre-21U, 26nt) into mature piRNA (21U-RNA, 21nt) as silencing tofu-1 or loss of tofu-1 function increases the pre-21U levels of piRNA in C. elegans5. To explore whether the downregulation of piRNAs after tofu-1 deletion in our transgenic models is due to the pre-21U accumulation, we analyzed the length distribution in these transgenic strains. Results confirmed that the pre-21U extensively accumulated in tofu-1 deletion strains (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c), suggesting that the downregulation of piRNAs was mainly due to the precursor piRNA accumulation. Combined with experiments that showed behavioral phenotype deficits were rescued and piRNAs were downregulated in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains, our results suggest that downregulation or inhibition of piRNA expression may decrease misfolded protein expression in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals.

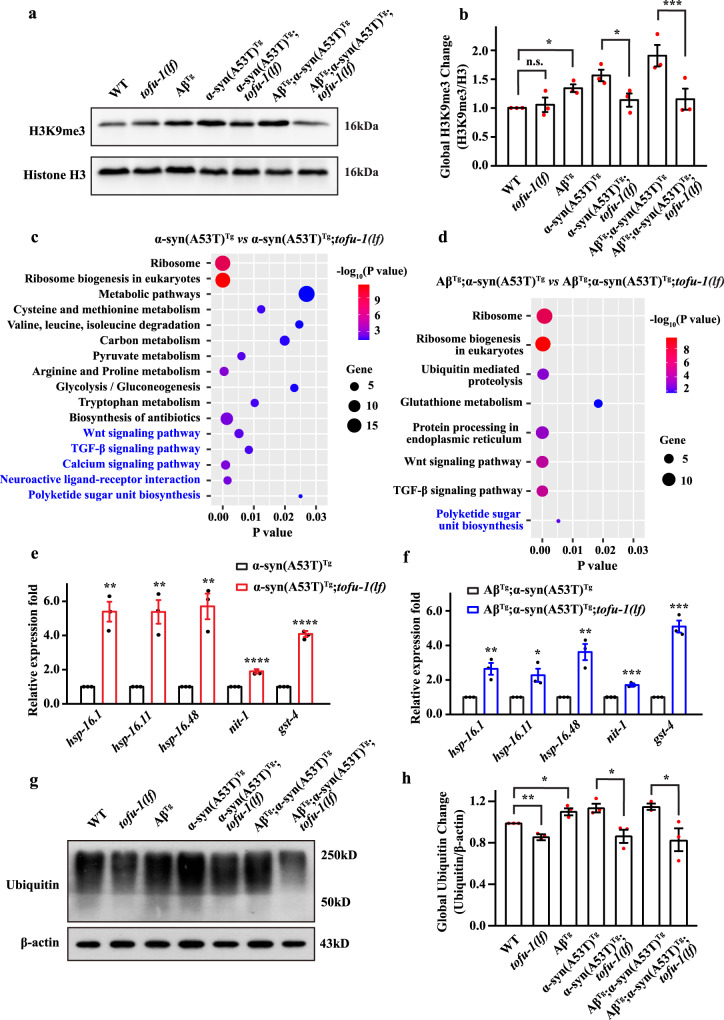

H3K9me3 levels increase in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains while decreasing after tofu-1 loss of function mutation

piRNAs regulate gene expression mainly through post-transcriptional or/and transcriptional silencing, these two processes required PRG-1 to form RISC2,29,30. Previous research detected a significant amount of prg-1 mRNA in germline less C. elegans and confirmed their presence in somatic cells using single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization12. In order to determine whether piRNAs recruit PRG-1 to mediate thrashing deficits, we crossed the prg-1 loss of function mutant to the overexpressing transgenic animals to generate compound strains α-syn(A53T)Tg;prg-1(lf). PRG-1 loss of function still improved thrashing in α-syn(A53T)Tg;prg-1(lf) strains (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Furthermore, we used RNAi to knock down tofu-1 in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg;prg-1(lf) strains with the result showing that tofu-1 could not improve thrashing (Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting that TOFU-1 required PRG-1 to execute its function.

piRNAs are loaded to PRG-1 to form RISC complexes and recruit histone marks of H3K9me3 to silence gene expression30. Thus, we examined whether H3K9me3 marks were changed in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals in genetic backgrounds that included or excluded the tofu-1 gene. Our results showed that the levels of H3K9me3 increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains compared with wild type, while H3K9me3 levels decreased in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) compared with our transgenic models (Fig. 3a, b). We further crossed H3K9me3 methyltransferase null mutant genes set-32 and set-25 into sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg and sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. SET-32 and SET-25 are required for the establishment of epigenetic silencing signals in C. elegans6. Our results showed that knock down of tofu-1 could not improve thrashing in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg;set-32(lf), sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg;set-25(lf), sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;set-32(lf) and sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;set-25(lf) transgenic strains (Supplementary Fig. 4d–g), suggesting that the piRNAs required repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 to regulated gene expression, while downregulation of piRNA expression decreases H3K9me3 levels.

Fig. 3. H3K9me3 change and RNA-Seq analysis in transgenic animals.

a, b Western blot analysis of H3K9me3 expression in transgenic animals at young adult stage (mean ± SEM, n = 3). c, d Enriched KEGG pathways analysis in transgenic animals. Pathways are shown on the left side of the chart. Black text indicates upregulated pathways and blue text indicates downregulated. The size of the balls denotes the number of genes in pathways that are regulated. −log10 (P value) is indicated by the color of the circle and the P value is indicated by the location on the horizontal axis. e, f Gene expression in transgenic animals (mean ± SEM, n = 3). g, h Western blot analysis of ubiquitination in transgenic animals in young adult stages (mean ± SEM, n = 3). For (b, h), p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA analysis. For (e, f) p-values were determined by two-tailed student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, n.s. not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Expression of protein degradation genes decrease in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains while increase after tofu-1 loss of function mutation

Since repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains while being decreased after tofu-1 deletion, we carried out ChIP-Seq to explore the H3K9me3 modification. Because piRNAs are mostly overexpressed in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, we mainly investigated the function of these overexpressed piRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. After annotating modified peaks, we identified 116 and 146 differentially H3K9me3 modified genes (|log2fold change | >2 and P < 0.05) in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, respectively compared with wild type in ChIP-Seq (Supplementary Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 3). ChIP-qPCR further confirmed the alteration of some modified genes in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). GO enrichment analysis showed that piRNAs mainly inhibited translation and ribosome function in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, suggesting that overexpression of piRNAs in our transgenic model primarily targeting genes involved in protein synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e).

piRNAs can silence transcripts through imperfectly complementary sites by initiating small interfering RNA response29,30, therefore, we analyzed the 22G-RNA expression. Our results suggested that 22G-RNAs showed the same expression trend with piRNAs. 22G-RNA expression levels increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, while decreased after tofu-1 deletion (Supplementary Data 4). We further predicted the target genes for piRNAs by using piRTarBase31. For WT vs α-syn(A53T)Tg, 23 overexpressed piRNAs target 935 genes, and 4 genes overlapped with 259 downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in RNA-Seq (Supplementary Fig. 6a)19. Among these 4 overlapped genes, T21E12.3 is predicted to be involved in proteolysis, which was downregulated in the α-syn(A53T)Tg strain. RNAi knock down of T21E12.3 slightly decreased thrashing in sid-1(OE);α-syn(A53T)Tg strain (Supplementary Fig. 6e). For WT vs AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg, 94 overexpressed piRNAs target to 1838 genes. Of these, 54 genes overlapped with 605 downregulated DEGs in RNA-Seq (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Among these overlapped genes, C08H9.1 and R03G8.6 are predicted to regulate proteolysis activity, while decreased in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain, and RNAi showed that decrease of these two genes exacerbated thrashing in sid-1(OE);AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Further enrichment analysis found that some of these upregulated piRNAs targets were enriched in endocytosis, phagosome, and MAPK signaling pathways, which are related with the protein degradation both in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b)32.

We further carried out RNA-Seq to compare gene expression before and after tofu-1 loss of function mutation in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. TOFU-1 deletion mainly increased the ribosome biogenesis, metabolic process, ubiquitin mediated proteolysis, and protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum ontologies, suggesting that the degradation ability increased after tofu-1 deletion in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic strains (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Data 5). Some protein folding genes like the heat shock proteins (hsp-16.1, hsp-16.11, hsp-16.48), which enable unfolded protein binding activity; nit-1 (enable hydrolase activity) and gst-4 (enables glutathione transferase activity) genes are all upregulated in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains compared with α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals both in RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR (Fig. 3e, f). Western blot further showed that ubiquitination increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, while decreased after tofu-1 deletion (Fig. 3g, h).

Taken together, these results suggest that overexpressed piRNAs target protein folding and degradation both in transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains; while tofu-1 deletion increased protein degradation genes expression in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals.

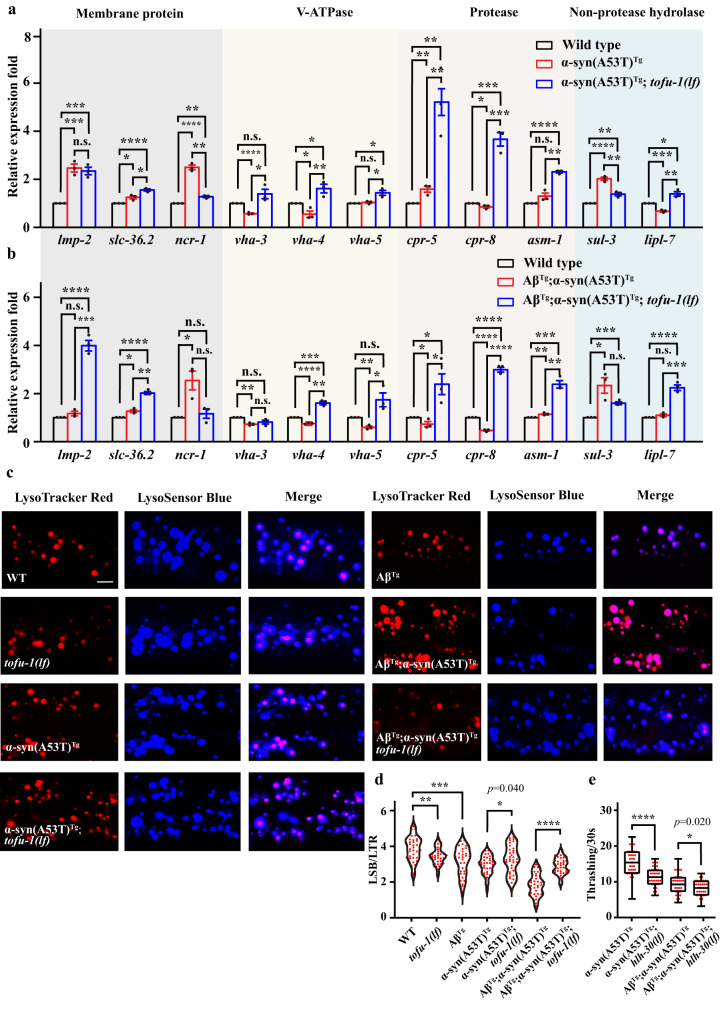

Lysosome function increases in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic strains

Since the sequencing data showed that piRNAs mainly target protein degradation genes, we further investigated lysosome activity to confirm whether protein degradation function was improved after tofu-1 deletion in our models based on several rationale. Firstly, our previous results showed that lysosome function mainly decreased in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains and in one type of LBD patient, dementia with Lewy body (DLB)19. Clinically, post-mortem PD brains showed the depletion of intraneuronal lysosomes, accumulation of undegraded autophagosomes, and reduction in the lysosome related proteins33. Lysosomal dysfunction is central to PD and other neurodegenerative diseases34. Secondly, protein degradation occurs through autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome pathways35; while the lysosome is at the crossroads of various degradative pathways including endocytosis and autophagy to regulate exogenous and endogenous cellular molecules36. Thirdly, α-syn processing is lysosomal-dependent, which affects its turnover, accumulation, and aggregation37. For instance, the mutation of glucocerebrocidase (GBA), which encodes a lysosomal enzyme involved in sphingolipid degradation, is the single greatest risk factor based on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in PD and LBD38,39.

Based on this background and combined with the protein degradation genes increase after tofu-1 loss of function mutation, we expected to observe that the overexpressed piRNAs would lead to decreased lysosome related gene expression levels in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains while increasing in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals. We used qRT-PCR to verify some of lysosomal gene expression in C. elegans. These genes encode lysosomal membrane proteins of lmp-2, slc-36.2, ncr-1, the proton pump V-ATPase of vha-3, vha-4, vha-5, the protease of cpr-5, cpr-8, asm-1, and the hydrolases of sul-3, lipl-7 (Fig. 4a, b)40. Our results demonstrated that the gene expression levels of proteases cpr-5, cpr-8 and asm-1 were significantly increased both in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains compared with α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains (Fig. 4a, b). Previous results showed that α-syn is primarily degraded by lysosomal proteases and cathepsin D, which is consistent with our results here41. Other genes like vha-3, vha-4, and lipl-7 were decreased in α-syn(A53T)Tg, and vha-4, vha-5 were decreased in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg, while they recovered after tofu-1 loss of function mutation in C. elegans (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, the lysosomal membrane proteins lmp-2, and slc-36.2 were significantly increased in AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Lysosome function in transgenic animals.

a, b qRT-PCR analysis of lysosomal gene expression in wild type and transgenic animals. The bottom of the bar chart indicates the gene name. The top of the bar chart indicates the type of gene. Bars are color coded to indicate different transgenic strains (mean ± SEM, n = 3). c Confocal imaging of lysosome morphology and acidity in transgenic animals by lysotracker red (LTR) and lysosensor blue (LSB) staining. Typical examples for each strain are shown. Images were obtained using Zeiss confocal microscope LSM710 at 630× magnification. Scale bar = 5 μM. d The fluorescence intensity of LSB/LTR in each strain was quantified. Each dot represents one nematode (n ≥ 30 for each group). e Thrashing assay in transgenic strains at young adult stage. The box plots display the median, upper, and lower quartiles; the whiskers show 1.5× interquartile range (IQR). Each dot represents one nematode (n ≥ 12 for each group). For (a, b, d, e), p-values were determined by one-way ANOVA analysis. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. n.s. not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to observe lysosome function at the cellular level, we co-stained with LysoTracker Red (LTR) and LysoSensor Blue (LSB) to monitor the morphology and acidity of the lysosome in transgenic animals. LSB is sensitive to acidity but not to LTR; therefore, LTR is used as a control for normalizing the LSB intake, and the fluorescence intensity ratio of LSB/LTR is used to indicate the activity of lysosome acidity40. Our results showed that lysosome acidity was dramatically reduced in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, while significantly improved in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals (Fig. 4c, d), suggesting that lysosome activity is improved after tofu-1 deletion in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains.

The TFEB orthologue HLH-30 is a master transcription factor for autophagy and lysosome biogenesis42, we further crossed hlh-30 mutant with α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains; results showed that the thrashing was further damaged after hlh-30 loss of function mutation in our transgenic animals (Fig. 4e).

Taken together, these results strongly suggest that piRNAs target protein degradation and reduce its function, whereas the degradation function was recovered after tofu-1 loss of function mutation by downregulating piRNAs expression.

piRNAs are dysregulated in pre-motor early and late motor stages of PD patients

In order to connect our findings to human disease, we analyzed small RNA-Seq data in PD patients43. In pre-motor PD patients, we identified 945 piRNAs that were upregulated and 810 piRNAs that were downregulated (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 6); whereas in late-motor PD patients, we found 731 piRNAs were upregulated and 66 piRNAs were downregulated (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Data 6). These results are consistent with our model that piRNAs are dysregulated in Lewy body diseases. In the late-motor stages of PD, most piRNAs were overexpressed, suggesting that a decrease in piRNA expression might be a potential therapeutic strategy for Lewy body diseases.

Fig. 5. piRNAs expression in PD patients.

a, b Volcano plot of piRNA expression in premotor and motor stages of PD patients. Data were obtained from GEO database (GSE97285) which includes 7 early premotor PD, 7 late motor stage PD, and 14 control samples. Red dots, P value < 0.01; orange dots, |log2(fold change)| > 1; blue dots, P value < 0.01 and |log2(fold change)| > 1; black dots, P value ≥ 0.01 and |log2(fold change)| ≤ 1. Data are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Discussion

For our PD model, we expressed human α-syn with alanine53 mutant to threonine (A53T) pan-neuronally under the aex-3 promoter. For the LBD model, we co-expressed Aβ with α-syn(A53T) (aex-3 promoter) while Aβ was under the snb-1 promoter19. Since our model expresses these proteins pan-neuronally, our western blots here and in previous publications18,19 show a high level of α-syn expression. Since C. elegans does not have a known α-syn ortholog and we overexpressed a mutant form of α-syn(A53T) pan-neuronally, our phenotypes may be more severe than other PD models that express α-syn in muscle cells. We did not compare the α-syn expression levels between our model with other PD models since the promoters, variants, and copy numbers of the α-syn transgene differ depending upon the model.

In our models of PD and LBD, which expresses α-syn(A53T) and Aβ;α-syn(A53T) pan- neuronally, we profiled small noncoding RNAs and unexpectedly found piRNA dysregulation characterized by predominant upregulation of piRNAs in transgenic animals, which was consistent with our previous work sequencing the α-syn(A53T)Tg strain20. We were then prompted to identify genetic interactors and found that knock down of piRNA biogenesis genes suppressed the impairment phenotypes suggesting that piRNAs mediate neuropathic deficits. Follow-up studies identified tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 as suppressors in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. Tissue specific RNAi suggested that the functions of tofu-1, tofu-3, tofu-4, and tofu-6 in our model were independent of germline function.

While all these genes perturb piRNA biogenesis, we focused on tofu-1 because it was enriched in neurons, functions late in biogenesis, and null mutants demonstrated strong deficits in the abundance of mature piRNAs5. Crosses of null mutant tofu-1 into single α-syn(A53T)Tg, AβTg or double AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg overexpressing transgenic animals revealed that TOFU-1 was necessary for thrashing, lifespan, and neuron morphology impairments, thus implicating mature piRNAs as mediators of neurodegeneration in our model. These tofu-1 mutants showed decreased α-syn expression in overexpressing transgenic animals. By using small RNA sequencing, we confirmed that tofu-1 deletion caused a massive downregulation of piRNAs, and this downregulation was mainly caused by piRNA precursor accumulation in our transgenic animals. Since tofu-1 is involved in piRNA biogenesis, we first considered that the piRNA pathway was essential to improve phenotypes in our transgenic models. We further observed that both tofu-1 and prg-1 mutants had extended lifespan compared with wild type animals, suggesting that tofu-1 not only functions in the piRNA pathway, but may also participate elsewhere to regulate biological processes to mediate lifespan extension. This suggests that tofu-1 deletion might improve phenotypes through non-piRNA mediated pathways and thus, we cannot rule out multiple actions of TOFU-1 in C. elegans.

We also examined the function of tofu-1 deletion in another PD model which expresses wild type α-syn in muscle cells (strain NL5901). We did not find that tofu-1 deletion decreased α-syn expression and aggregation in this α-syn(WT)Tg model (Supplementary Fig. 8a–d). We speculate that tofu-1 did not express or function in muscle cells, which could not change the α-syn expression in α-syn(WT)Tg strain. Since piRNAs recruit histones to activate or silence gene expression, we hypothesized that piRNAs affect gene expression of α-syn and other targets via epigenetic modification. We first identified repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains while decreased after tofu-1 deletion. These results suggested that piRNAs act mainly through repressive epigenetic marks to execute its silencing function. Previous research observed that 4 piRNAs could reciprocally regulate 4 mRNAs (CYCS, LIN7C, KPNA6, RAB11A) in AD brain, suggesting that a direct action may be possible23. We also wondered whether some individual piRNAs could directly decrease α-syn expression by post-transcription; however, we were unable to identify dysregulated piRNAs that targeted sequences for α-syn transcripts directly, which prompted us to consider whether piRNAs regulated other processes to change the α-syn level.

By using ChIP-Seq, 21U-RNA target prediction, and RNA-Seq, we showed that the function of dysregulated piRNAs was related to protein degradation. ChIP-Seq indicated that overexpressed piRNAs might recruit repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 to silence the transcription and synthesis of protein related genes. 21U-RNA target prediction found that some piRNA targets are directly related to protein folding, which decreased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strain. Enrichment analysis for overexpressed piRNA targets also showed that these targets are enriched in folding related pathways. Furthermore, by using RNA-Seq to observe the changes in α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) transgenic animals, we were able to confirm that overexpressed piRNAs target to protein folding genes, which decreases its degradation ability in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic models, while the degradation activity was restored after deletion of tofu-1 gene. We tried to find out overlapped genes between ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq, while we only identified a few overlapped genes. One possible explanation would be that the epigenetic regulation of dysregulated genes is more complex than we anticipate. For example, the use of more and different Chip-Seq antibodies may uncover more overlaps. Another explanation would be that our Chip-Seq or RNA-Seq methods are not sensitive enough to uncover overlapping genes. Finally, the role of post transcriptional regulation may be underestimated in our study.

Since α-syn is mainly degraded by the lysosomal-autophagic pathway and combined with our previous study that showed lysosome function was decreased in an LBD model and patients; and that the mutation of GBA, which encodes a lysosomal enzyme involved in sphingolipid degradation, is the single greatest risk factor for PD and LBD38,39; and LBD patients have 6 to 8 times higher risk as a carrier with GBA mutant44; we were prompted to further investigate lysosome function. Our results confirmed that lysosome function decreased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains whereas its function improved after tofu-1 loss of function mutation and piRNA downregulation. Even though our results show that tofu-1 deletion improves phenotypes, further studies will still need to be conducted to strengthen the relationship between piRNA function and protein degradation. If piRNAs were overexpressed in the transgenic model of α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg, we would expect to see increased piRNA expression in patient tissues. To test this, we analyzed a publicly available dataset (GSE97285) of small RNA reads from control and early premotor or late motor PD brain tissues43. In this dataset, we found both upregulated and downregulated piRNAs (945 up and 810 down) in early pre-motor, but more upregulated piRNAs (731 up and 66 down) in late motor stage samples, entirely consistent with the hypothesis of increased piRNAs in neurodegeneration in Lewy body diseases. The dysregulation of piRNAs was shown in PD neuronal cells and AD patients previously21–23; while the function of piRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases are not well understood. By using a PD and LBD model in C. elegans, we showed that dysregulated piRNAs targeted protein degradation, and provided a plausible explanation for the roles of piRNAs in neurons. Nonetheless, more animal models and datasets will be needed in the future to expand the knowledge of how small noncoding RNAs function in somatic cells in both healthy and disease states.

Another alternative explanation of how piRNAs exacerbate neurodegenerative processes, besides epigenetic modification, maybe via their traditional targets, transposons. While we did not investigate transposon expression here, it was reported in a Drosophila tauopathy model that a differential expression of more than 100 transposable elements could be observed15. Furthermore, a study of AD brains showed a high transcriptional activation of transposable elements that correlated with neurofibrillary tangles, a pathological hallmark in AD45. While beyond the scope here, future studies will investigate various downstream effects of piRNA dysregulation including their mRNA as well as noncoding RNA targets.

We found piRNAs dysregulated both in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals. Deletion of piRNA biogenesis gene of tofu-1 ameliorates behavioral phenotypes, improves thrashing, extends lifespan, decreases α-syn expression, and alleviates dopaminergic neuron degeneration in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. The tofu-1 loss of function mutation extensively downregulated piRNAs, which were mainly caused by piRNA precursor accumulation in our transgenic models. piRNAs required PRG-1 to improve thrashing after tofu-1 loss of function mutation. Further, repressive epigenetic marks of H3K9me3 were increased in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg transgenic animals, whereas tofu-1 deletion returned these levels to near wild type strain levels. piRNAs mainly target protein degradation genes, which leads to misfolded protein accumulation through post-transcriptional and transcriptional gene silencing. Downregulated piRNA expression reversed behavioral phenotypes in transgenic animals. Based on the body of our results, we propose a sequence of piRNA actions in α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains both before and after tofu-1 gene deletion (Fig. 6), where piRNAs can mediate the neurodegenerative effects of α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains. Lastly, we found piRNAs were overexpressed in the late stage of PD patients, indicating that these effects might be conserved from C. elegans to humans. Our data suggests that piRNAs regulate the pathogenesis of Lewy body diseases, and that reduction of piRNA expression may ameliorate symptoms in Lewy body diseases. This work provides a role of piRNA in neurons and may thus open other avenues to investigate the molecular basis for neurodegenerative diseases.

Fig. 6. Proposed piRNA function in transgenic animals.

In α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg strains, piRNA dysregulation upregulates H3K9me3 to silence and/or directly target protein degradation genes which cause α-syn accumulation. After blocking piRNA biogenesis by knocking out the tofu-1 gene, piRNAs downregulate and decrease H3K9me3, while protein degradation gene expression increases, which improves the activity of protein degradation and decreases α-syn expression in C. elegans.

Some limitations still exist in our work. We were unable to identify specific piRNAs that target Aβ or α-syn directly, which would provide direct evidence about piRNA function in the context of these pathological proteins. In addition, it remains unclear how tofu-1 regulates lifespan extension, and we still do not understand how this common effect (piRNA pathway and lifespan extension) improves phenotypes in PD and LBD models. Although PRG-1 was detected in somatic cells, it remains to be determined whether PRG-1 is localized in neurons. Furthermore, we are unable to identify piRNA targets in PD patients since most of the piRNA processes are obscure in humans. Knowledge concerning the biogenesis of piRNAs and related processes mainly comes from animal models like mouse, Drosophila, and C. elegans; therefore, how piRNA biogenesis occurs and the identification of their putative targets in humans deserves further exploration.

Methods

Strains and maintenance

All strains were cultured on NGM plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 at 16 °C unless otherwise indicated. For experiments, C. elegans was transferred to 23 °C in order to activate the Aβ peptide expression at L3 stage. New strains were created by standard genetic crosses and genotypes were confirmed by PCR or sequencing. The strains used and created in this project are listed in Supplementary Data 7.

Thrashing assay

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C till they reached L3, then transferred to 23 °C until growth to L4 or young adults. Late L4 or young adult nematodes were placed in a drop of M9 buffer and allowed to recover for 30 s, then video recordings of the body bends for 30 s for each strain under the microscope were taken. Some of the recordings were analyzed by Image J software under the plugin of wrMTrck46. At least 12 nematodes were counted in each experiment. The experiment was performed 3 times with independent biological replicates.

Locomotion assay

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until they reached L3, then transferred to 23 °C until growth to adults. Day 1 old adult nematodes were chosen randomly from RNAi plates and transferred to fresh plates seeded with OP50. After 5 min recovery period, the number of body bends was counted per minute on each nematode by visual observation on a Nikon SMZ700 dissecting microscope at 60× magnification. At least 12 nematodes were counted for each experiment. Each experiment was performed 3 times with independent biological replicates.

Lifespan assay

All strains were cultured on NGM plates for 2–3 generations without starvation at 16 °C. For the assay, C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C till they reached L3, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to L4 or young adult. Late L4 or young adult nematodes were transferred to NGM plates seeded with fresh OP50 and defined as experiment day 0. Animals were transferred to fresh plates every other day. If C. elegans did not respond to mechanical stimulation from a platinum wire, they were scored as dead. If C. elegans crawled off the plate, displayed extruded internal organs, or died due to the hatching of progeny inside the uterus, these nematodes were censored. The entire lifespan assay was repeated with at least 3 independent trials.

RNAi plasmid construction

RNAi plasmids for tofu-3, tofu-6 were produced by PCR cloning and ligation into pL4440 vector (Addgene). All primer pairs included XhoI and NheI restriction sequences (tofu-3: 5’- AAAGCTAGCTCCAAAATGCGAAGCACCC; 3’- AAACTCGAGTGCACAATCACGAG GAACCA; tofu-6: 5’-AAACTCGAGCCGTGTTGTTGGACAATCC; 3’- AAAGCTAGCGG AAGACTCCATCGTAGCC). C. elegans were collected by M9, and total RNA was extracted by using RNAiso Plus (Takara). Leftover DNA was digested with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). The purified RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA by RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two microliters of the RT cDNA products were used in each PCR reaction with Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and purified by PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The vector pL4440 and PCR product were digested by XhoI and NheI enzymes and ligated by T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The ligation reactions were terminated by heat-inactivation and transfected into DH5a competent bacteria. Ampicillin resistant bacteria colonies were grown, and their plasmids were isolated and sequenced to verify correct sequences. Finally, the verified plasmids were transfected into HT115 and further verified by restriction digestion and sequencing again to confirm the correct sequences.

RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) was performed on NGM plates containing 2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 25 μg/mL carbenicillin. RNAi bacteria were cultured in LB liquid (100 μg/mL ampicillin) with each target gene fragment or empty vector (Source from BioScience Nottingham, UK) at 37 °C overnight, then centrifuged and transferred to the NGM plates47. L2 or L3 stage nematodes were transferred onto RNAi plates and left to grow and lay eggs for 4–5 days at 16 °C. These progenies were allowed to grow to L4 or young adults before molecular, cellular, or behavioral assays. For thrashing, at least 12 late L4 or young adult nematodes were placed in a drop of M9 buffer and allowed to recover for 30 s, then video recordings of the body bends for 30 s for each RNAi clone under the microscope were taken. For locomotion, at least 12 day 1 adults were randomly chosen from RNAi plates and transferred to a fresh plate seeded with OP50. After 5 min recovery, the number of body bends was counted per minute on each nematode. Each experiment was performed 3 times with independent biological replicates.

Dopaminergic neuron impairment assay

For dopaminergic neuron observation, 60 nematodes at day 8 in each group were mounted onto agarose pads and paralyzed with 15 mM sodium azide. The micrographs for dopaminergic neurons were taken by a Zeiss confocal microscope LSM710 at 400× magnification. ZEN imaging software (Zeiss, Germany) was used to analyze the photos for each strain.

Chemotaxis assay

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. Animals were collected with M9 and washed 3 times. For each strain, animals were divided into naïve, trained, and control groups, each group contained at least 100 nematodes. For naïve group, animals were placed directly onto assay plates. For the trained group, animals were starved in M9 for 1 h, then transferred to NGM plates containing OP50, and 2 μL of 10% butanone was added to the lid for odor training for 1 h. For the control group, animals were starved in M9 for 1 h, then transferred to NGM plates containing OP50 without odor in the plates. After 1 h, these two plates of nematodes were washed with M9 and transferred to assay plates for observation. The number of worms was counted on both butanone and ethanol spots containing 1 μL of 1 M sodium azide after 1 h. Chemotaxis index (CI) and Learning index (LI) were calculated as Chemotaxis index (CI): [Nbut − Neth] / [Total − Norigin]; Learning index (LI): CIbut – CInaive48. Each experiment was performed 3 times with independent biological replicates.

Western blot

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. To extract H3K9me3 and ubiquitin proteins, C. elegans were collected with M9 buffer and transferred to RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor. Animals were sonicated for 30 min (Bioruptor® Plus sonication device), then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min to obtain the protein lysate. To extract the total α-syn, animals were collected with M9 buffer and resuspended in TBS-Urea-SDS buffer (1× TBS (pH 7.4), 5% SDS, 8 M Urea, 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1× protease inhibitor cocktail)49. Animals were sonicated for 30 min and centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min to get rid of the debris. Supernatants were taken and further centrifuged at 14000 g for 20 min to obtain the protein lysate, this lysate contains soluble and insoluble α-syn in C. elegans. To extract the monomer and polymer forms of α-syn, animals were collected with M9 buffer and transferred to RAB buffer containing protease inhibitor. Animals were ground by pellet pestles, and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min to obtain protein lysate, this lysate mainly contains soluble α-syn in C. elegans.

Lysate supernatants were taken, and protein concentrations were measured by using the PierceTM BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty micrograms of proteins were loaded onto 12% SDS/PAGE or native/PAGE gels and blotted onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). The primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4 °C, then changed to the secondary antibody and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Antibody binding was visualized by using ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad). Antibodies used were anti-α-synuclein (LB509) (1:1000, Abcam, ab27766), anti-α-synuclein (1:1000, Thermo Fisher, PA5-85343), anti-β-actin (C4) (1:2000, Santa cruz, sc-47778), anti-H3K9me3 (1:2000, Abcam, ab8898), anti-Histone H3 (1:2000, Abcam, ab1791), anti-ubiquitin (1:2000, Proteintech, 10201-2-AP), Rabbit Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (1:2000, Abcam, ab97046), Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (1:2000, Proteintech, SA00001-2).

Lysosome staining

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until animals grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. Animals were washed twice by M9 and soaked in M9 buffer containing 25 μM of lysotracker red and the same concentration of lysosensor blue (Invitrogen). Staining was carried out for 1 h at room temperature in dark. C. elegans were transferred to fresh NGM plates seeded with OP50 and allowed to recover for another 1 h40. Animals were picked up and paralyzed by 15 mM sodium azide and images were taken by a Zeiss confocal microscope LSM710 at 630× magnification. The fluorescence intensity of the lysosome was analyzed by using Image J software. At least 30 nematodes were scored for each strain.

qRT-PCR

For gene expression, C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. C. elegans were collected in M9. RNAiso Plus (Takara) was used to extract total RNA. For mRNA expression, High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems™) was used to convert RNA to cDNA. The qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™) and ABI 7500 system. The relative expression levels of genes were carried out using 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the expression of gene cdc-42.

For small RNAs expression, Mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis (Takara) was used to convert small RNA to cDNA. The qRT-PCR was performed using TG GreenTM Advantage qPCR Premix (Takara) and ABI 7500 system. The relative expression levels of piRNAs were carried out using 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the expression of U65. All the primers for genes and piRNAs expression are listed in Supplementary Data 8.

RNA-Seq

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. C. elegans were collected by M9, and total RNA was extracted by using RNAiso Plus (Takara). RNA samples were quantified by Bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100). RNA library was prepared following NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 (FHS Genomics, Bioinformatics & Single Cell Core, University of Macau).

For quality control, adaptor sequences, low quality reads, and ambiguous reads were removed and then mapped to C. elegans genome (WBcel235) using HISAT250. The genome sequence and gene annotation files were downloaded from the NCBI database. Samtools was used for sorting and Stringtie was used to estimate the abundances of transcripts and genes51,52. edgeR was used to perform differential expression analysis with thresholds as |log2(fold change) | >2, P value < 0.01 and FDR < 0.0553. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed in DAVID bioinformatics resources54. We refer to heat-shock protein genes as protein folding or protein degradation genes during function analysis. The protein products of these genes have dual related functions in both protein folding and protein degradation55–57.

For the sequencing data on α-syn(A53T) and Aβ;α-syn(A53T) strains, data were downloaded from a dataset with the accession number PRJNA622398 in NCBI SRA19. The analysis workflow was the same with our other samples in RNA sequencing with the thresholds adjusted to |log2(fold change)| > 1.5, P value < 0.01, and FDR < 0.05.

Small RNA-Seq

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. C. elegans were collected by M9, and total RNA was extracted by using RNAiso Plus (Takara). RNA samples were quantified by Bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100). A small RNA library was prepared following NEBNext® Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (New England Biolabs), size selection of the cDNA library was performed by 6% TBE PAGE gel (140 bp for miRNA, 150 bp for piRNA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq™ 2000. In order to keep all samples consistent, we collected wild type, α-syn(A53T)Tg, α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf), AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg and AβTg;α-syn(A53T)Tg;tofu-1(lf) strains, and sequenced all samples in one throughput submission to minimize technical variations or potential batch effects (FHS Genomics, Bioinformatics & Single Cell Core, University of Macau).

For quality control, adaptor sequences, low quality reads, and ambiguous reads were removed to obtain clean reads, which were then mapped to the C. elegans genome (WBcel235) using Bowtie (-a -v 0 -m 10)58. Samtools was used for sorting and the piRNA annotation files were downloaded from NCBI (WBcel235)51. featureCounts was used to measure the abundance of piRNA. edgeR was used to identify significant differentially expressed piRNA using threshold as P value < 0.01, FDR < 0.05, and |log2 (fold change)| > 1.553. piRNA targets were predicted by using piRTarBase31. The enrichment analysis of piRNA targets was performed in DAVID bioinformatics resources54.

For 22G-RNAs analysis, potential 22G-RNAs were defined as 21-23 nt reads starting with G and using featureCounts with parameter (-s 2) to measure 22G-RNA antisense counts on the basis of their sequence being antisense to protein coding genes, transposons, simple repeats or piRNAs. edgeR was used to identify the differentially expressed 22G-RNAs coverage between different groups using threshold as P value < 0.01, FDR < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| > 1.553.

ChIP-Seq

C. elegans were cultivated at 16 °C until nematodes grew to L3 stage, then transferred to 23 °C until they grew to young adults. C. elegans were collected and washed by M9 buffer three times. The supernatant was discarded to obtain a tightly packed pellet and the nematodes were placed into liquid nitrogen immediately. Frozen nematodes were ground using a pestle and suspended in 1% fresh formaldehyde in PBS solution to cross-link proteins to DNA, and then incubated at room temperature on a shaker for 10 min. The crosslinking reaction was quenched by adding 2 M glycine and incubated for 5 min. C. elegans was washed three times with cold PBS (contain 1× proteinase inhibitor cocktail) and kept in −80 °C59. The C. elegans pellet was resuspended in nuclei preparation buffer (Imprint® Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit) and sonicated for 18 min with 30 s ON and 30 s OFF (Bioruptor® Plus sonication device) to get the 150–500 bp of DNA fragments. Chip reactions were carried out using 2–5 μg chromatin DNA, 5 μL of diluted supernatant was removed as “input DNA”, then 2 μg of H3K9me3 antibody was added (Abcam, ab8898). After 60–90 min, samples were reverse crosslinked to obtain the genomic DNA.

For ChIP-Seq, genomic DNA was purified. The DNA library was prepared following the protocol of NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs), and sequencing was performed by Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 (FHS Genomics, Bioinformatics & Single Cell Core, University of Macau).

For quality control, adaptor sequences, low quality reads, and ambiguous reads were removed to obtain clean reads, which were then mapped to the C. elegans genome (WBcel235) using Bowtie260. Samtools were used for sorting and peaks were identified by using MACS251,61. edgeR was used to identify significant differentially modified peaks between two groups using threshold as P value < 0.05 and |log2 (fold change)| > 253. Chipseeker was used to annotate the differentially modified peaks62. The heatmaps, read distribution of differentially modified peaks were drawn by using deepTools63. The enrichment analysis of differentially H3K9me3 modified genes were performed in DAVID bioinformatics resources54.

ChIP-qPCR

For ChIP-qPCR, genomic DNA was purified and then analyzed by using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™) and ABI 7500 system. The calculation of the % Input for each ChIP fraction was 2(−ΔCt [normalized ChIP]), where ΔCt [normalized ChIP] = (Ct [ChIP] - (Ct [Input] - Log2(Input Dilution Factor))). Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data 8.

Bioinformatic analysis of PD patient samples

Non-coding RNA profiling dataset (GSE97285) including 7 early-premotor PD samples, 7 late-motor stage PD samples, and 14 control samples were downloaded and analyzed to obtain the differentially expressed piRNAs in PD patients43. Samples were obtained from the amygdala. The raw data were downloaded from SRA database using prefetch and decompressed by fastq-dump. The human genome sequence file (GRCh38) was downloaded from NCBI database. The piRNA annotation files were downloaded from piRBase64, respectively. Read alignment was performed by Bowtie (-a -v 0 -m 10)55. Samtools was used for sorting and featureCounts was used to measure the piRNA abundance51,65. edgeR was used to do differential analysis using threshold as P value < 0.01 and |log2 (fold change)| > 153.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey Post-Hoc test to compare each group. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used only in two group comparisons. The difference was considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Kaplan-Meier was carried out and P values were calculated using log-rank test in lifespan analysis. Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS statistic 20. Figures were drawn by OriginPro 8 or GraphPad Prism 8, and further imported to Adobe Illustrator CC 2018.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants (MYRG2017-00123-FHS and MYRG2020-00213-FHS) to G.W. from the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62002212) to L.C.; the Shantou University Scientific Research Foundation for Talents (no. 35941918) and 2020 Li Ka Shing Foundation cross-disciplinary research grants (2020LKSFG07D, 2020LKSFG09B) to L.C. We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), for providing some of the Caenorhabditis elegans strains used in this work. We thank National Bioresource Project (NBRP) for providing some of the Caenorhabditis elegans strains used in this work. We thank all the members in Genomics, Bioinformatics & Single Cell Core in Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau for helping us to do the RNA-Seq, small RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq. We thank all the members in Garry Wong’s lab and Hongjie Zhang’s lab for comments and suggestions.

Author contributions

X.B.H. and G.W. contributed to the research design and writing the paper. H.J.Z. and Q.H.Z. contributed to providing RNAi clones and some strains. C.L.W., T.J.Z. and L.C. contributed to bioinformatic analysis. X.B.H., R.Z.L., K.L.L., and M.L. contributed to experiment performances.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Eugenia Goya and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All relevant data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript and/or its supplementary information. The data underlying Figures and Supplementary Figures are provided as Source data. The Raw RNA, and small RNA and ChIP-Seq data generated in this study have been deposited to NCBI SRA database; the accession numbers are PRJNA732252 for RNA-Seq, PRJNA622394 for small RNA-Seq, PRJNA983087 for tofu-1 mutant small RNA-Seq, and PRJNA763505 for ChIP-Seq, respectively. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-41881-8.

References

- 1.Vagin VV, et al. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science. 2006;313:320–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1129333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:246–258. doi: 10.1038/nrm3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwasaki YW, Siomi MC, Siomi H. PIWI-interacting RNA: its biogenesis and functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:405–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izumi N, Tomari Y. Diversity of the piRNA pathway for nonself silencing: worm-specific piRNA biogenesis factors. Genes Dev. 2014;28:665–671. doi: 10.1101/gad.241323.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goh WS, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies factors required for distinct stages of C. elegans piRNA biogenesis. Genes Dev. 2014;28:797–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.235622.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozata DM, Gainetdinov I, Zoch A, O’Carroll D, Zamore PD. PIWI-interacting RNAs: small RNAs with big functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:89–108. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sienski G, Donertas D, Brennecke J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell. 2012;151:964–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luteijn MJ, Ketting RF. PIWI-interacting RNAs: from generation to transgenerational epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrg3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang X, Wong G. An old weapon with a new function: PIWI-interacting RNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2021;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s40035-021-00233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajasethupathy P, et al. A role for neuronal piRNAs in the epigenetic control of memory-related synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2012;149:693–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EJ, et al. Identification of piRNAs in the central nervous system. Rna. 2011;17:1090–1099. doi: 10.1261/rna.2565011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KW, et al. A neuronal piRNA pathway inhibits axon regeneration in C. elegans. Neuron. 2018;97:511–519.e516. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore RS, Kaletsky R, Murphy CT. Piwi/PRG-1 argonaute and TGF-beta mediate transgenerational learned pathogenic avoidance. Cell. 2019;177:1827–1841.e1812. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaletsky R, et al. C. elegans interprets bacterial non-coding RNAs to learn pathogenic avoidance. Nature. 2020;586:445–451. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2699-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun W, Samimi H, Gamez M, Zare H, Frost B. Pathogenic tau-induced piRNA depletion promotes neuronal death through transposable element dysregulation in neurodegenerative tauopathies. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:1038–1048. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soto C, Pritzkow S. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:1332–1340. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Outeiro TF, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: an update and outlook. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019;14:5. doi: 10.1186/s13024-019-0306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakso M, et al. Dopaminergic neuronal loss and motor deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans overexpressing human alpha-synuclein. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:165–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, et al. Human amyloid beta and alpha-synuclein co-expression in neurons impair behavior and recapitulate features for Lewy body dementia in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochim. et. Biophys. acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021;1867:166203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen L, Wang C, Chen L, Wong G. Dysregulation of MicroRNAs and PIWI-interacting RNAs in a caenorhabditis elegans parkinson’s disease model overexpressing human α-synuclein and influence of tdp-1. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:600462. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.600462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulze M, et al. Sporadic Parkinson’s disease derived neuronal cells show disease-specific mRNA and small RNA signatures with abundant deregulation of piRNAs. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:58. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0561-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu W, et al. Transcriptome-wide piRNA profiling in human brains of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2017;57:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy J, Sarkar A, Parida S, Ghosh Z, Mallick B. Small RNA sequencing revealed dysregulated piRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease and their probable role in pathogenesis. Mol. Biosyst. 2017;13:565–576. doi: 10.1039/C6MB00699J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2002;295:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1068836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumsta C, Hansen M. C. elegans rrf-1 mutations maintain RNAi efficiency in the soma in addition to the germline. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e35428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 2015;386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnaoutoglou NA, O’Brien JT, Underwood BR. Dementia with Lewy bodies - from scientific knowledge to clinical insights. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15:103–112. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maulik M, Mitra S, Bult-Ito A, Taylor BE, Vayndorf EM. Behavioral phenotyping and pathological indicators of Parkinson’s disease in C. elegans models. Front. Genet. 2017;8:77. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagijn MP, et al. Function, targets, and evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans piRNAs. Science. 2012;337:574–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1220952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batista PJ, et al. PRG-1 and 21U-RNAs interact to form the piRNA complex required for fertility in C. elegans. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu WS, et al. piRTarBase: a database of piRNA targeting sites and their roles in gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D181–D187. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Z, Hunter T. Degradation of activated protein kinases by ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:435–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.013008.092711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehay B, et al. Lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson disease: ATP13A2 gets into the groove. Autophagy. 2012;8:1389–1391. doi: 10.4161/auto.21011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallings RL, Humble SW, Ward ME, Wade-Martins R. Lysosomal dysfunction at the centre of Parkinson’s disease and frontotemporal dementia/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42:899–912. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ihara Y, Morishima-Kawashima M, Nixon R. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagic-lysosomal system in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006361. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonam SR, Wang F, Muller S. Lysosomes as a therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:923–948. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzulli JR, Zunke F, Isacson O, Studer L, Krainc D. alpha-Synuclein-induced lysosomal dysfunction occurs through disruptions in protein trafficking in human midbrain synucleinopathy models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520335113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerreiro R, et al. Investigating the genetic architecture of dementia with Lewy bodies: a two-stage genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blauwendraat C, et al. Genetic modifiers of risk and age at onset in GBA associated Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Brain: J. Neurol. 2020;143:234–248. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]