Abstract

Background:

Mapping exercises are important to inform development of interventions aiming to enhance private sector's contribution towards achieving health systems objectives.

Objective:

To map size, types, and distribution of private health institutions, and to identify the services they offer, and their alignment with Ministry of Health priorities.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study targeted licensed, for-profit private health institutions in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Secondary data were collected from Department of Private Health Institutions in Riyadh and the Ministry of Health Year Statistical Book. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze the collected data.

Results:

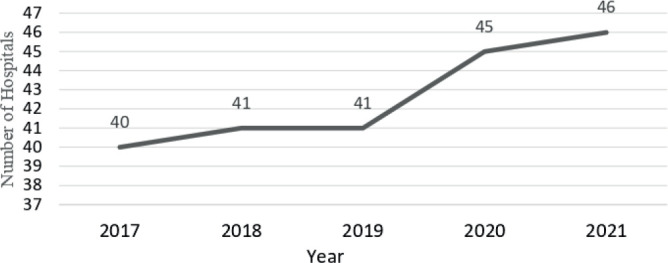

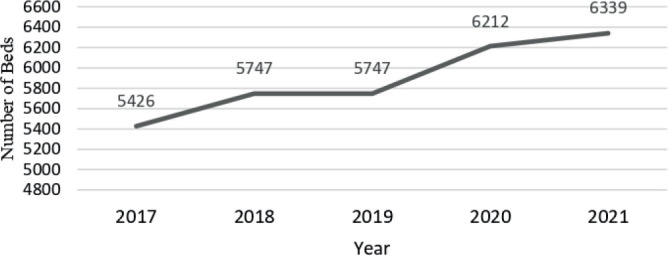

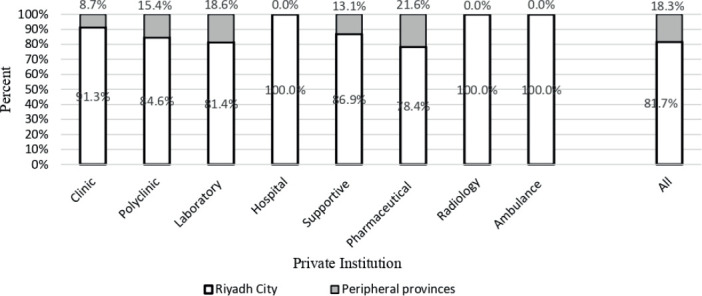

Private hospitals increased from 40 (2017) to 46 (2021), with private sector hospital beds rising from 5,426 (2017) to 6,339 (2021). Pharmaceutical institutions comprised 55.4% of private health institutions, followed by polyclinics (23%) and supportive health services centers (17.1%). Laboratories, hospitals, and clinics represented 2%, 1%, and 0.5% of private health institutions respectively. Ambulance and radiology service centers were least available private health institutions at 0.1%. Home healthcare, remote care, telemedicine, family medicine, and long-term care were offered by 1.3%, 0.5%, 0.4%, and 0.1% of private health institutions respectively. Private hospitals accounted for 41.4% of total hospitals and private hospitals beds constituted 30.9% of Riyadh's total, with an average of 137.8 beds per hospital. Around 82% of private health institutions were in Riyadh city, with around 18% in peripheral provinces.

Conclusion:

Private healthcare sector has witnessed substantial growth, primarily influenced by supply rather than demand dynamics. Incentives are essential to promote investment in Ministry of Health priorities.

Keywords: Private Health sector, Mapping, Saudi Arabia

1. BACKGROUND

The private sector plays a pivotal role in health systems by delivering a diverse range of healthcare services, encompassing medical care, medical products, financial services, workforce training, information technology, infrastructure, and supportive services (1). While private health sector (PHS) providers primarily pursue commercial and market-oriented objectives, they hold substantial potential to aid the public sector in fortifying the health system and ensuring equitable access to healthcare for all (2, 3). The ability of the PHS's to contribute to healthcare is attributed to its capacity to address various challenges affecting health systems. These challenges include fiscal constraints, increasing noncommunicable diseases, demographic changes, and political and economic instability (1).

Therefore, amidst the growing global focus on universal health coverage, effective engagement and collaboration with the expanding PHS are crucial to acknowledge its pivotal role as a substantial provider of healthcare worldwide (2). Furthermore, by harnessing the potential of the rapidly expanding private sector, not only can universal access to healthcare be improved, but economic growth and development can also be stimulated (3). Consequently, in recent years, the global discourse has shifted from a historically polarized debate between the public and private sectors to a more collaborative approach, focusing on finding ways to ensure the effective and efficient functioning of both systems in order to achieve universal and comprehensive coverage of health services for populations (2, 4).

In Saudi Arabia, the healthcare system consists of a mix of public and private providers. The Ministry of Health (MOH) serves as the primary public provider and financier of healthcare services, delivering 60% of the total health services in the country (5). The MOH offers free-of-charge healthcare services at the point of use to Saudi citizens and expatriates employed in civil services (5, 6). In addition to the MOH, the public health sector includes other entities that provide healthcare such as the Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of National Guard, Ministry of Higher Education, and the Red Crescent Society (5).

The private sector plays a significant role in providing healthcare services in Saudi Arabia, with a notable presence of 125 hospitals (equipped with 11,833 beds) and 2218 dispensaries and clinics (5). Private sector healthcare services operate under a fee-for-service model, where patients personally bear the costs or utilize private health insurance plans for payment (6).

The Saudi Ministry of Health has taken significant steps to promote increased private sector participation in the healthcare sector, offering interest-free long-term loans for the construction and operation of hospitals and clinics, as well as establishing new public-private partnerships (7). To ensure adherence to practice standards and maintain a satisfactory level of healthcare service quality, the Saudi Ministry of Health has developed policies and legislations specific to the private sector and implemented a standardized registration and regulation process for private health providers (5, 7, 8).

Furthermore, in order to enhance the role and maximize the contribution of the private sector to sustainable economic development, as well as to align with the government's aim of achieving universal health coverage, the Ministry of Health has developed guidelines for potential investors interested in investing in the healthcare sector (5, 9). These guidelines specifically encourage investments in a range of healthcare institutions, encompassing primary healthcare clinics, general or specialized polyclinics, home health care, remote care /telemedicine, and rehabilitation/long-term care centers (9).

However, to effectively devise policies for expanding and leveraging the private health sector's potential, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of its current scale, scope and untapped potential. Such mapping exercise inform the development of strategies and interventions aimed at enhancing the private sector's contribution to achieving health objectives of the country.

2. OBJECTIVE

To assess the private healthcare sector in the Riyadh Region of Saudi Arabia, specifically focusing on mapping the size, types and distribution of private health institutions, identifying the range of health services offered by it, and evaluating the alignment of these services with the priorities set by the Ministry of Health.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study setting and population

The study was conducted in the Riyadh Region, which comprises the capital city of Riyadh surrounded by 30 peripheral provinces. The study population comprised private health institutions as classified by the Ministry of Health into various categories including clinics, polyclinics, hospitals, laboratories, pharmaceutical facilities, supportive health services centers, radiology centers, and ambulance services. Health instituions were included if they hav a valid licence from the General Directorate of Health Affairs in Riyadh, and if they belong to the for-profit, formal medical sector.

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Committee of King Fahad Medical City approved the study proposal.

Measures

The study used secondary data sources including the records of the Department of Private Health Institutions in the Riyadh General Directorate of Health Affairs and the Ministry of Health Year Statistical Book (2022). Data were collected using a data collection sheet covering the following variables: Types of private health institutions, specialties provided by the private health institutions, number of private hospitals and beds from 2017 to 2021, number and specialties of beds in the public and private hospitals in 2021.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 21.0 for Windows. The study used descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and percentages to produce the study outcomes. Line graphs were used to illustrate the trends over time.

4. RESULTS

Size, types and specialties of the private health sector’s institutions

Figure 1A shows a consistent increase in private hospitals in Riyadh from 40 in 2017 to 46 in 2021. Similarly, Figure 1B demonstrates a rise in private sector hospital beds from 5,426 in 2017 to 6,339 in 2021. Table 1 provides an overview of different types of private health institutions. Pharmaceutical institutions represented the majority at 55.4%. Polyclinics accounted for 23% and dentistry was the most common specialty provided in over half of them (53.8%). Supportive health services centers made up 17.1% of private health institutions, providing complementary health and technical services. Laboratories comprised 2%, while hospitals and clinics represented 1% and 0.5% respectively. Ambulance and radiology service centers each contributed only 0.1% of private health institutions.

Figure 1A: Number of Hospitals in the privatr sector (2017-2021).

Figure 1B: Number of Beds in the private sector (2017-2021).

Table 1. The type of private health institutions in Riyadh Region (N= 4359).

| Type | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical facility | 2417 | 55.4 |

| Poly clinic | 1038 | 23.8 |

| Supportive health services | 747 | 17.1 |

| Laboratory | 86 | 2.0 |

| Hospital | 42 | 1.0 |

| Clinic | 23 | 0.5 |

| Ambulance services | 3 | 0.1 |

| Radiology | 3 | 0.1 |

Regarding the Ministry of Health’s recommended priority areas for investment, home healthcare services were provided by 1.3% of private health institutions, remote care/telemedicine services were provided by 0.5%, family medicine was offered in 0.4% of institutions, and long-term care was available in 0.1%. In 2021, the most prevalent specialties in private beds were obstetrics and gynecology (14.9%) followed by surgery (14.5%).

Geographical distribution of private health institutions:

Figure 2 depicts the geographical distribution of private health institutions in the Riyadh Region. Approximately 82% of these institutions were located in the capital city of Riyadh, while around 18% were situated in peripheral provinces within the region. Notably, private hospitals, radiology services, and ambulance services were absent in the peripheral provinces.

Figure 2: The geographical distribution of private health institutions in Riyadh Region.

Comparison between the public and private health sectors

In 2021, the public sector in Riyadh consisted of 65 hospitals, including those affiliated with the Ministry of Health and other governmental sectors, such as the Ministries of Defense, Interior, National Guards, and Higher Education (Table 2). Conversely, the private sector comprised 46 hospitals, accounting for 41.4% of the total number of hospitals (Table 2).

Table 2. Hospitals and Hospital Beds in the Public and Private sectors in Riyadh Region in 2021.

| Public | Private | % private | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of primary healthcare clinics/centers | 390 | 18 | 4.6% |

| Number of hospitals | 65 | 46 | 41.4% |

| Number of beds | 14172 | 6339 | 30.9 |

| Average number of beds per hospital | 218 | 137.8 |

Regarding bed capacity, public hospitals under the Ministry of Health and other public sector Ministries had a total of 14,172 beds, while private sector hospitals had 6,339 beds, representing 30.9% of the total beds in Riyadh (Table 2). On average, public hospitals had 218 beds per hospital, while the private sector had 137.8 beds per hospital (Table 2).

The Ministry of Health exhibited a greater number of beds in internal medicine, intensive care, and pediatrics. On the other hand, the private sector demonstrated a higher number of beds in surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, as well as burns and plastic surgery.

5. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study indicate a significant rise in the quantity of private hospitals and hospital beds within the Riyadh region over the past five years. This pattern aligns with similar trends observed in Saudi Arabia (10), and globally, highlighting the expanding role of the PHS within healthcare systems (3, 4, 11). The observed increase in the Riyadh Region aligns with the economic reforms implemented by the Saudi Government through the "Vision 2030" plan, which aims to enhance private sector participation in healthcare delivery and financing (6). It also responds to the global imperative of engaging the PHS to achieve universal health coverage targets (1).

The results of this study show that the health system in Riyadh is mixed, with private hospitals accounting for approximately 41% of the total number of hospitals and private hospital beds representing around one third of total bed capacity in the region. This pattern shares similarities with "group 2" of the four healthcare provision models observed in European countries. Within this model, private facilities have increasingly focused on providing profitable outpatient services, particularly surgeries with low co-morbidities and predictable management (12). As a result, private hospitals tend to have fewer beds compared to public facilities, as indicated by our results, suggesting prioritization of services with well-defined and lower-risk care, that lead to a higher turnover of beds (2).

Evidence from Europe demonstrates that this model, which combines private and public healthcare provision, is comparable to predominantly private or predominantly public models in effectively achieving universal health coverage, promoting equitable access to care, and achieving high levels of satisfaction among patients (12). Overall, numerous recent reforms in OECD countries have focused on transitioning predominantly public healthcare systems towards "group 2" models, with the aim to enhance the involvement of private healthcare providers while maintaining significant state funding (13).

The observed significant presence of the private sector in the Riyadh Region emphasizes the need to promote collaboration between the public and private sectors and exploring opportunities for public-private partnerships for harnessing the potential of the private sector in achieving overall health system objectives. This is important because private sector providers often concentrate on specific types of services and geographical settings, leading to challenges in equity and population coverage (14).

In this regard, and in order for the private sector to effectively contribute to health system objectives in Riyadh region, it is essential for its services to align with the priorities set by the Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia actively encourages investments in primary healthcare clinics, general or specialized polyclinics, home health care, remote care/telemedicine and rehabilitation/long-term care centers (9). The findings of this study indicate significant investment in polyclinics and to some extent in home health services within the Riyadh Region. These services were shown to be prefered by the private sector, attributed to their outpatient nature and relatively low-risk features (2, 13).

On the other hand, our results show that the level of investment in primary healthcare was comparatively low. As shown by the results of this study, the clinics are the least available private health institutions and constituted only 4.6% of the primary healthcare clinics and centers in Riyadh Region in 2021. Furthermore, these clinics in Riyadh Region are not classified as primary healthcare centers but rather offer specialized services. Family medicine was observed as a specialty in only a small proportion of private health institutions in Riyadh.

The achievement of universal health coverage requires a health system that prioritizes primary healthcare as an essential component (15). This approach entails countries taking overall responsibility for healthcare, regardless of whether it is delivered by the public or private sector (4). Currently, in high-income countries and OECD countries, private settings predominantly deliver primary care services, even in countries with national health systems (12). Evidence from numerous countries indicates a preference for private primary healthcare providers due to advantages such as improved geographic accessibility, shorter waiting times, and easier access to staff consultations and medication (16).

Private practitioners may find primary care an appealing investment option due to its lower capital requirements, high demand, and patients' willingness to pay (17). However, hospital care tends to be more attractive as economies of scale are realized at a modest size, resulting in substantial cost reductions with increased patient volume (18). Consequently, the private sector's preference for investing in hospitals over primary care clinics may be attributed to these factors.

Similarly, as shown by the results of this study, the private sector in the Riyadh Region has not given sufficient attention to two priority areas outlined by the Ministry of Health: rehabilitation/long-term care centers and remote care/telemedicine. The limited investment in long term care is consistent with practices observed in OECD countries, as the for-profit private sector may find long-term care unattractive due to its high costs and significant financial implications (19). On the other hand, the limited use of remote care/telemedicine in Riyadh Region differs from the practice of private healthcare providers in OECD countries who are increasingly offering access to remote consultations using telemedicine (20). However, a major barrier to the widespread adoption of telemedicine in these and other countries was the lack of clear reimbursement mechanisms (20, 21).

We also noted a lower proportion of intensive care beds in the private sector compared to the public sector, which aligns with trends observed in other countries (22). The involvement of the private sector in providing intensive care plays a crucial role in enhancing surge capacity during times of high demand, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the limited development of extensive acute and intensive care capabilities in the private sector can be attributed to the elective nature of private practitioners' work and the higher unit costs associated with professional services in the private sector (13, 22).

Our findings highlight a significant contribution of the private sector in Riyadh Region towards pharmaceutical and dental services. This aligns with similar trends observed in European countries, where community pharmacies and dental practices are predominantly privately owned and operated (12). The consensus within European health systems is that private markets are best suited for the provision of community pharmacy and dental services, given the specific nature and regulation of these areas of care (2). Case studies from various countries have demonstrated that private ownership leads to increased utilization, lower costs for consumers, and higher levels of client satisfaction (2).

Our findings indicate that private healthcare institutions in the Riyadh Region are predominantly concentrated in the central Riyadh city compared to the peripheral provinces. The concentration of private healthcare facilities in urban areas, as observed in other countries (3) is a prevalent trend. Private providers tend to cluster in urban areas characterized by higher per capita income, high population density, and convenient market access, including healthcare resources. These urban characteristics contribute to lower establishment costs and a greater demand for medical care (3, 17). The concentration of private facilities in areas where public facilities are already present suggests that their establishment may not expand the coverage by health services (3).

All the above findings suggest that in Riyadh Region, as in other countries, private sector interventions are predominantly driven by supply rather than demand. This highlights the need to implement demand-driven interventions to ensure that private providers actively contribute to the overall goals of the healthcare sector. These interventions should involve the government and other stakeholders, including the private health sector, to ensure alignment with national priorities and objectives (1, 3).

To further promote investments in priority services such as primary healthcare, long-term care, remote care and telemedicine and intensive care within the Riyadh Region, the provision of incentives becomes crucial. Various financial incentives, such as direct subsidies, grants, tax benefits, in addition to non-monetary support, can be employed to influence the behavior of private healthcare sector actors and encourage their investment in these essential health services (14, 23).

Study limitations

The study primarily relied on existing data sources related to the private health sector; therefore there may be potential gaps in the available data. Furthermore, the study did not include an examination of the quality of healthcare provided by the private sector. Therefore, further investigations are needed to explore this important aspect.

6. CONLUSION

The private sector has grown significantly in the Riyadh Region, primarily influenced by supply rather than demand dynamics. The resulting mixed health system follows the European "group 2" model that prioritize outpatient services and low-risk surgeries. Investment aligns with the Ministry of Health's priorities in polyclinics and home health services, while primary healthcare, long-term care, telemedicine and intensive care receive less investment. Pharmaceutical and dental services receive substantial investment. Private healthcare institutions are concentrated in Riyadh city, with peripheral provinces experiencing lower investment. Considering the substantial presence of the private sector in the healthcare system, it is important to explore opportunities for establishing public-private partnerships to harness the potential of the private health sector. Also, incentives should be provided to encourage private sector to investment in the ministry's identified priority areas and to expand coverage to underserved regions.

Patient Consent Form:

The utilized secondary data about private health institutions with contact with patients.

Authors’ contribution:

The All authors gave substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study. H. A. N. A., N. A.,R. T., and I. A. gave subtsanial contribution in acquisition of data. All authors contributed in analysis of data and interpretation of results. R. T. And M. H. prepared the draft. All authors revised and gave final approval of the final draft to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. author was involved in preparation all steps of this text and approved final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship:

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clarke D, Doerr S, Hunter M, Schmets G, Soucat A, Paviza A. The private sector and universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(6):434–435. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.225540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Private Sector Landscape in Mixed Health Systems. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Govindaraj R, Navaratne K, Cavagnero E, Seshadri SR. Health Care in Sri Lanka : What Can the Private Health Sector Offer? HNP Discuss Pap [Internet] 2014;(June 2014):1–66. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/423511468307190661/Health-care-in-Sri-Lanka-what-can-the-private-health-sector-offer . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umar-sadiq M. Role of private sector engagement in reimagined primary health care delivery: Comprehensive review. 2020;(June) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. EMHJ. 2011;17(10):784–793. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hanawi MK, Almubark S, Qattan AMN, Cenkier A, Kosycarz EA. Barriers to the implementation of public-private partnerships in the healthcare sector in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. PLoS One [Internet] 2020;15(6):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233802. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233802 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Analysis of the Private Health Sector in the Countries of Eastern Mediterranean. Exploring unfamiliar territory. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qutub A, Al-Jewair T, Leake J. Kingston, Canada A comparative study of the health care systems of Canada and Saudi Arabia: lessons and insights. International Dental Journal. 2009;59:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Minsitry of Health; Guidelines for investment in small to medium healthcare institutions. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman R. The Privatization of Health Care System in Saudi Arabia. Heal Serv Insights. 2020;13 doi: 10.1177/1178632920934497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang C, Zhang Y, Chen L, Lin Y. The growth of private hospitals and their health workforce in China: A comparison with public hospitals. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(1):30–41. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montagu D. The Provision of Private Healthcare Services in European Countries: Recent Data and Lessons for Universal Health Coverage in Other Settings. Front Public Heal. 2021;9(March):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.636750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Propper C, Green K. A Larger Role For the Private Sector in Health Care? A Review of the Arguments. 1999;32 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqi S, Aftab W, Venkat Raman A, Soucat A, Alwan A. The role of the private sector in delivering essential packages of health services: Lessons from country experiences. BMJ Glob Heal. 2023;8:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. The private sector, universal health coverage and primary health care. Tech Ser Prim Heal Care [Internet] 2018. pp. 1–9. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1216992/retrieve .

- 16.Joudyian N, Doshmangir L, Mahdavi M, Tabrizi JS, Gordeev VS. Public-private partnerships in primary health care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05979-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preker AS, Harding AL. Private Participation in Health Services: Health, Nutrition, and Population [Internet] Human Development Network: Health, Nutrition, and Population Series. 2003. pp. 157–218. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/15147 .

- 18.Russo G. The role of the private sector in health services: lessons for ASEAN. East-West Cent Repr Popul Ser. 1995;308(2):190–211. [Google Scholar]

- 19.OECD. Public and Private Sector Relationships in Long-term Care and Healthcare Insurance. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cravo T, Hashiguchi O. Brining Health Care to the Patients: An Overveiw of the Use of Telemedicine in OECD Countries. OECD Health Working Paper No. 116. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmanizadeh F, Ameri A, Bahaadinbeigy K. Methods of Reimbursement for Telemedicine Services: A Scoping Review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022;36(1) doi: 10.47176/mjiri.36.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin JM, Hart GK, Hicks P. A unique snapshot of intensive care resources in Australia and New Zealand. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(1):149–158. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters H, Hatt L, Peters D. Working with the private sector for child health. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18(2):127–137. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]