Abstract

Approximately 15% of cancers exhibit loss of the chromosomal locus 9p21.3 – the genomic location of the tumour suppressor gene CDKN2A and the methionine salvage gene methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP). A loss of MTAP increases the pool of its substrate methylthioadenosine (MTA), which binds to and inhibits activity of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5). PRMT5 utilises the universal methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to methylate arginine residues of protein substrates and regulate their activity, notably histones to regulate transcription. Recently, targeting PRMT5, or MAT2A that impacts PRMT5 activity by producing SAM, has shown promise as a therapeutic strategy in oncology, generating synthetic lethality in MTAP-negative cancers. However, clinical development of PRMT5 and MAT2A inhibitors has been challenging and highlights the need for further understanding of the downstream mediators of drug effects. Here, we discuss the rationale and methods for targeting the MAT2A/PRMT5 axis for cancer therapy. We evaluate the current limitations in our understanding of the mechanism of MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitors and identify the challenges that must be addressed to maximise the potential of these drugs. In addition, we review the current literature defining downstream effectors of PRMT5 activity that could determine sensitivity to MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibition and therefore present a rationale for novel combination therapies that may not rely on synthetic lethality with MTAP loss.

Keywords: MTAP, MAT2A, PRMT5, methionine, metabolism, synthetic lethality

1. Introduction

1.1. MTAP deletion creates therapeutic vulnerabilities in tumours

Gain-of-function or activating genetic alterations that occur in many cancers have proven useful as precision therapy targets. However, loss-of-function alterations must be targeted indirectly. To utilise these alterations for therapy, there must be a thorough understanding of the altered processes associated with the loss of gene products and any cancer-specific susceptibilities that may arise. Large genomic deletions that occur in cancers can lead to a growth or survival advantage by loss of tumour suppressor function. However, co-deletion of other genetic material in close physical proximity (“passenger deletions”) may create new “synthetically lethal” or “collateral” vulnerabilities to therapy (1, 2). The chromosome 9p21.3 region is deleted in approximately 15% of cancers (3, 4) and contains the tumour suppressor gene cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A). This gene encodes for the p14 (5) and p16 (6) proteins that stabilise p53 and block G1 progression respectively. Only 100 kb away from the CDKN2A locus resides a key gene in the methionine metabolism cycle, 5’-deoxy-5’-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) (7). MTAP is co-deleted with homozygous loss of CDKN2A in approximately 80-90% of cases of 9p21.3 homozygous deletion (8) and its loss is associated with poor prognosis (9–11). The co-occurrence of CDKN2A/MTAP deletion may explain early literature that observed MTAP loss in leukaemia (12, 13) and breast cancer (14).

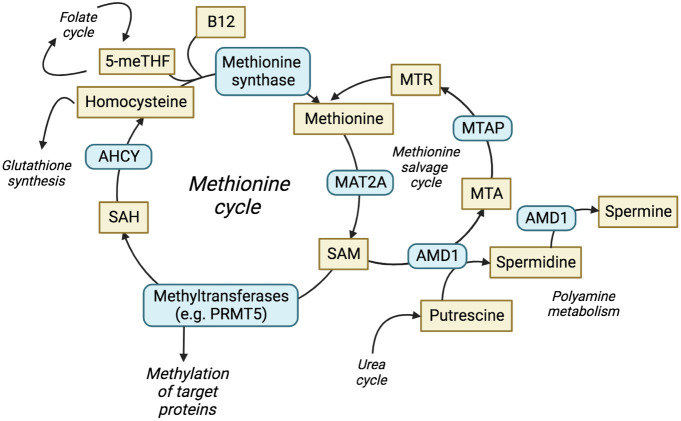

MTAP metabolises methylthioadenosine (MTA) in the methionine salvage cycle, regenerating methionine for further cycling ( Figure 1 ) (15). Methionine is an essential amino acid and loss of MTAP increases cellular dependence upon exogenous methionine (16), with implications for nucleotide synthesis, folate metabolism, glutathione synthesis and the urea cycle. MTA is a product of the synthesis of the universal methyl donor, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), and the polyamine synthesis pathway. MTA was shown to be secreted into culture medium by MTAP-negative leukaemia cells in vitro (17), whilst elevated levels of MTA and MTA secretion have frequently been observed in multiple cell lines derived from solid tumours with homozygous deletion of MTAP (18–20). MTAP is the only enzyme known to metabolise MTA, which highlights a lack of redundancy in this process and suggests that targeting methionine metabolism may be an effective therapy against MTAP-negative malignancies. Furthermore, loss of 9p21.3 has been shown to be a driver, or trunk event, that occurs early in cancer evolution (21). This suggests that MTAP deletion is present before additional branch mutations have occurred, i.e. before other adaptive processes can take place.

Figure 1.

The methionine cycle and interrelated pathways. The production and utilisation of SAM is central to the methionine cycle and allows protein methylation by methyltransferases. The methionine salvage cycle recovers methionine through the conversion of MTA to methionine via the analogue MTR. ACHY, adenosylhomocysteine; AMD1, adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1; ASA, arginonosuccinic acid; MTR, methylthioribose; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; SAH, S-adenosyl-homocysteine; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

Multiple studies in 2016 undertook short hairpin RNA (shRNA) screens to identify genes that cause synthetic lethality with both endogenous and genetically engineered loss of MTAP (18–20). All provided evidence of a conditional dependence on protein arginine methyl transferase 5 (PRMT5), RIOK1, WDR77 (MEP50) and methionine adenosyltransferase II alpha (MAT2A). These proteins are involved in the methionine cycle or subsequent methylation reactions: MAT2A catalyses the direct production of SAM (22, 23); PRMT5 and its associated binding partners RIOK1 (24) and MEP50 (25, 26) utilise SAM as methyl donor to methylate specific protein targets.

In this review, we examine the current understanding of therapeutic vulnerabilities intrinsic to MTAP-negative tumours, focusing on MAT2A and PRMT5, which are receiving increasing attention in clinical development. We discuss the function of MAT2A and PRMT5, including binding partners, current methods of inhibition, downstream signalling and effect on metabolic pathways. We review the interplay between these proteins, and how therapeutic inhibition impacts growth, cell cycle, apoptosis or DNA damage response. Finally, we highlight the challenges that face the therapeutic targeting of the MAT2A/PRMT5 axis, the need for additional predictive biomarkers other than MTAP status, and how these biomarkers could predict rational combination therapies.

2. The structure and function of PRMT5

PRMT5 is a member of the family of protein arginine methyltransferases responsible for methylating specific arginine residues of a wide range of proteins and thus regulate protein activity. This includes histones that regulate chromatin structure and epigenetic regulation of gene expression (27). The nine members of the PRMT family can be split into four distinct types that distinguish their activity. Type I, II and III PRMTs catalyse the formation of monomethylarginine intermediates at the terminal guanidino nitrogen atom of arginine, which can be subsequently modified to produce asymmetric dimethylarginines (ADMA) by the type I PRMTs (e.g. PRMT1) or symmetric dimethylarginines (SDMA) by the type II PRMTs (e.g. PRMT5). Type IV PRMTs can also monomethylate arginine, but they do this at the internal guanidine nitrogen atom of arginine (28, 29).

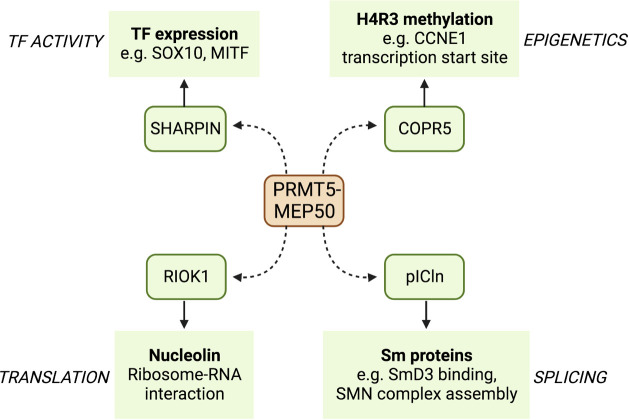

PRMT5 is the principal type II PRMT and functions mainly as a negative regulator of transcription (30). PRMT5 contains two distinct domains: a C-terminal catalytic domain that interacts with the methyl donor SAM and a N-terminal TIM barrel domain that allows interaction with binding partners such as MEP50 (26). PRMT5 binds to MEP50 to produce PRMT5-MEP50 heterodimers, which in turn form a tetramer complex; these interactions are essential for stimulating the activity of PRMT5. SAM is then utilised by the complex as a methyl donor to allow the addition of the methyl group to the target arginine. PRMT5 binds to substrate adaptor proteins (SAPs) that are required for PRMT5 targeting and subsequent methylation. All SAPs share the peptide sequence GQF[D/E]DA[D/E] known as the PRMT5 binding motif (PBM), which facilitates PRMT5 binding (31), and the specific SAP that binds to PRMT5 can localise its activity to different substrates ( Figure 2 ). The PRMT5 complex has been shown to preferentially bind an arginine- and glycine-rich (GRG) domain in the target substrate proteins as the site of arginine methylation (32). More than 100 substrates have been identified that are methylated by PRMT5 to regulate their functions, including proteins that promote survival and tumorigenesis (32, 33).

Figure 2.

A selection of binding partners (SAPS) of PRMT5 and some of their targets. PRMT5 binds to the PBM of a number of SAPs that localise its arginine methylation activity to different sites. Here, we show four PRMT5 SAPs that act as adapters to specify binding to transcription factors such as SOX10 and MITF, translation regulating proteins such as nucleolin, splicing factors such as SmD3, and CDK regulators such as the cyclin CCNE1.

3. PRMT5 activity and cancer

Many studies have identified that increased activity and upregulation of PRMT5 is a key regulator of cancer progression and marker for poor prognosis in multiple malignancies, including breast (34), gastric (35), glioblastoma (36), leukaemia (37), lung (38), lymphoma (39), ovarian (40), pancreatic (41) and prostate cancer (42). PRMT5 can act to promote tumorigenesis by methylating histone and non-histone proteins to regulate transcriptional and post-translational cell growth pathways, respectively ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

PRMT5 targets.

| PRMT5 target | Function | PRMT5 action on target | Cell line/cancer type | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALYREF | Pre-mRNA transport and splicing | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| AR | Tumour promoting gene | Increased expression via epigenetic regulation | LNCaP, C4-2 (Prostate cancer) | (42) |

| C-Myc | Regulate NF-κB pathway | Increased expression and stabilise protein | T24, 5637 (Bladder cancer), MUA PaCa-2, SW1990 (Pancreatic cancer) | (41, 43) |

| CANNTG | C-Myc-binding E-box element | Reduced expression of downstream genes via epigenetic regulation | BGC823 and SGC7901 (Gastric cancer) | (35) |

| CCNE1 | G1/S transition via CDK2 regulation | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | U2OS | (44) |

| CCT4 | Component of TRiC complex | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| CCT7 | Component of TRiC complex | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| CD74 | Component of MHC II molecule | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | Liver cancer | (45) |

| CDH1 | Tumour suppressor gene | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | A549 (Lung cancer) | (46) |

| CIITA | Component of MHC II molecule | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | Liver cancer | (45) |

| CPSF6 | 3’ RNA cleavage and polyadenylation | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| E2F1 | Transcription factor that can regulate apoptosis | Methylation and destabilisation of protein | U2OS | (47) |

| FA genes | Inter-strand crosslink (CIL)-induced DNA damage repair | Increased expression via epigenetic regulation | U251MG, T98G, U118MG (Glioblastoma) | (48) |

| FBW7 | C-Myc regulator gene | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | PaCa-2, SW1990 (Pancreatic cancer) | (41) |

| FOXP1 | Activates oestrogen receptor (ER) | Increased expression via epigenetic regulation | MCF7 (Breast cancer) | (34) |

| IFI16 (IFI204) | Regulator of STING/cGAS signalling pathway | Methylation of protein to control function | A375, WM115, B16 (Melanoma) | (49) |

| Mxi1 | C-Myc agonist | Methylation of protein leading to degradation | H1299, A549, H460, H522, H358 (NSCLC) | (50) |

| NLRC5 | Regulator of MHC I gene expression | Decreased expression of gene | B16, CCLE melanoma cell lines (Melanoma) | (49) |

| NM23 | Tumour suppressor gene | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | NIH/3T3 | (51) |

| p53 | Promotes cell cycle arrest to allow DNA repair, regulates apoptosis | Methylation of protein to inactivate pro-apoptotic function | U2OS, HSPCs | (52, 53) |

| PNN | Part of exon junction complex (EJC) | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| RPS10 | Component of the 40S ribosomal subunit | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| RUVBL1 | Component of TIP60 complex for directing DNA damage repair towards the HR pathway | Methylation of protein to allow complex formation | HeLa (Cervical cancer) | (54) |

| SFPQ | Early splicing factor | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| Sm proteins | Formation of the spliceosome | Methylation required for smRNP biogenesis | HeLa (Cervical cancer) | (55) |

| SNAIL1 | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastatic activator factor | Increased expression via epigenetic regulation | A549 (Lung cancer) | (46) |

| SNRPB | Component of SMN-Sm complex | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| SPDEF | Tumour suppressor gene | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | A549 (Lung cancer) | (46) |

| SRSF1 | Prevents exon skipping | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| ST7 | Tumour suppressor gene | Reduced expression via epigenetic regulation | NIH/3T3 | (51) |

| SUPT5H | mRNA processing, transcription and elongation of RNAP II | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| VIM | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastatic activator factor | Increased expression via epigenetic regulation | A549 (Lung cancer) | (46) |

| WDR33 | mRNA polyadenylation | Methylation of protein | THP-1 (AML) | (37) |

| ZNF326 | Subunit of DBIRD complex that regulates alternative splicing | Methylation requires for accurate splicing | MDA-MB-231 (Breast cancer) | (56) |

3.1. Epigenetic control of tumour regulating genes by PRMT5

Overexpression of PRMT5 has important consequences for the epigenetic landscape of cancer across different cancer types. An early study identified PRMT5 as a binding partner of hSWI/SNF complexes that cooperatively target tumour suppressor genes ST7 and NM23 to inhibit their transcription (51). Transcriptome profiling of PRMT5/MEP50 shRNA knockdown lung cancer models identified differential expression of components of the TGFβ pathway, suggesting that PRMT5 may be important for the TGFβ response and subsequent cancer metastasis (46). Knockdown of PRMT5 and MEP50 showed a reduction of activating epigenetic methylation markers (H3R2me1 and H3R4me3) at the promoters of SNAIL1 and VIM, both key epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis activator genes. In the same conditions, a reduction of repressive marks (H4R3me2) at the tumour suppressor genes SPDEF and CDH1 was observed (46). Co-operator of PRMT5 (COPR5), a SAP, is essential for PRMT5 binding and H4R3 methylation at transcription starts sites of genes such as CCNE1 (44). In prostate cancer cells, the androgen receptor (AR) promoter was shown to be an epigenetic target of PRMT5, and knockdown of PRMT5 caused a reduction in H4R3me2 marks at the AR promoter and a subsequent reduction in AR expression (42). In breast cancer stem cells, it was shown that PRMT5 functions to methylate H3R2, allowing SET1 binding and H3K4 trimethylation at the FOXP1 promoter to activate FOXP1 transcription both in vitro and in vivo. The expressed FOXP1 protein promoted breast cancer cell proliferation by activating oestrogen receptor (ER) signalling (34). PRMT5 was reported to deposit H4R3me2 marks at the c-Myc-binding E-box element (CANNTG), and that, in addition to c-Myc, PRMT5 binding results in the silencing of downstream genes. The genes affected include negative regulators of cell cycle, such as PTEN, CDKN2C, CDKN1A, CDKN1C and p63 (35). PRMT5 has also been shown to epigenetically silence the promoter region (via an increase of H4R3me2 and H3K9me3 marks) of the c-Myc regulator gene FBW7 (41). A reduction in PRMT5 activity also has a negative regulatory effect on the DNA damage repair Fanconi Anaemia (FA) family genes via reduced H3R2 monomethylation markers at FA gene promoters (48). PRMT5 was also suggested to regulate MHC II expression by histone methylation at the promoters of CD74 and CIITA, therefore affecting how tumours present to the immune system (45). Hence, PRMT5 has shown specific epigenetic control of a range of cancer-relevant genes and promotes growth and progression.

3.2. Transcription factor regulation by PRMT5

p53 is a widely studied tumour suppressor protein that responds to DNA damage by arresting growth and inducing an apoptotic response (57). PRMT5 has been shown to associate with STRAP (DNA damage cofactor) and p53, leading to the subsequent methylation of p53, whilst low expression of PRMT5 led to p53-induced apoptosis (52). The presence and methyltransferase activity of PRMT5 was later shown to be sufficient to inactivate p53 in haematopoietic stem progenitor cells (HSPCs), inhibit apoptosis and increase self-renewal in vitro and in vivo (53). Thus, an increase in PRMT5 expression will positively impact cancer proliferation.

As with p53, the transcription factor E2F1 can promote apoptosis by activating pro-apoptotic genes. PRMT5 has been found to methylate and destabilise E2F1 (47) and short interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of PRMT5 caused an increase in E2F1 mRNA and protein levels in ovarian cancer cells, resulting in decreased growth rate and induction of apoptosis (40). E2F1 can act in a mutually exclusive pro- or anti-proliferative manner, the former when marked with the symmetric methylation of R111/R113 by PRMT5. Conversely, asymmetric methylation of R109 by PRMT1 induces apoptosis. PRMT5 methylation of E2F1 and PRMT1 knockdown were both linked to a decrease in mRNA levels of apoptosis associated proteins (APAF1, p73 and E2F-1). Moreover, symmetric arginine methylation of E2F1 via PRMT5 was read by proliferation-promoting protein p100-TSN, which increased the binding of p100-TSN to promoters of proliferation-inducing genes (cyclin E, Cdc6 and DHFR) (58). Knockdown or inhibition of E2F1 and PRMT5 in HCT116 cells was later shown to lead to reduced expression of cell migration and invasion genes (e.g. cortactin/CTTN) and consequently defects in these processes. Further, PRMT5/E2F1 expression and cortactin/CTTN expression showed positive correlations across different types of cancer in the Cancer Genome Atlas datasets (TCGA) (59), suggesting that E2F1 and PRMT5 regulate the process of cell migration and invasion.

PRMT5 has been reported to promote c-Myc expression and consequently up-regulate the NF-κB pathway (43). Furthermore, PRMT5 has been shown to stabilise c-Myc in pancreatic cancer cells (41). PRMT5 also methylates the c-Myc agonist Mxi1 to promote β-Trcp ligase-directed degradation of Mxi1. Consequently, inhibition of PRMT5 achieved radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (50). These results highlight an important and widespread role of PRMT5 in promoting the oncogenic mechanisms of cancer. Reduction or inhibition of PRMT5 could therefore be an approach for treating cancer.

3.3. The role of PRMT5 in splicing and DNA damage repair

Seven small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) formed of Sm proteins and small nuclear RNA assemble to form the spliceosome (60). The spliceosome requires the snRNP assembly factor SMN to accurately assemble and bind at sites that require splicing (61). SMN binds the dimethylated arginine/glycine (GRG) domains of Sm proteins to allow for accurate recognition (62). Sm dimethylation is attributed to the 20S methyltransferase complex, or methylosome, comprising PRMT5, MEP50 and the SAP pICln (63). The methylosome (specifically PRMT5) acts to add SDMA modifications to Sm proteins that are required for snRNP biogenesis and the resulting process of splicing in vivo (55). Post-translational dimethylation of the splicing-associated protein ZNF326 was reduced upon PRMT5 inhibition by causing inclusion of AT rich introns in target genes, which phenocopied the loss of ZNF326 protein (56, 64). Deletion of PRMT5 has been shown to cause perturbed splicing leading to reduced canonical, and increased alternative, splicing specifically in pre-mRNAs with a weak 5’ donor site (65). This study highlighted alternatively spliced Mdm4 mRNA as a recurrent product of PRMT5 deletion. Mdm4 encodes for a key activator of p53 and alternative splicing leads to increased activation of the p53 transcription process and indicates a response to PRMT5 inhibitors (66).

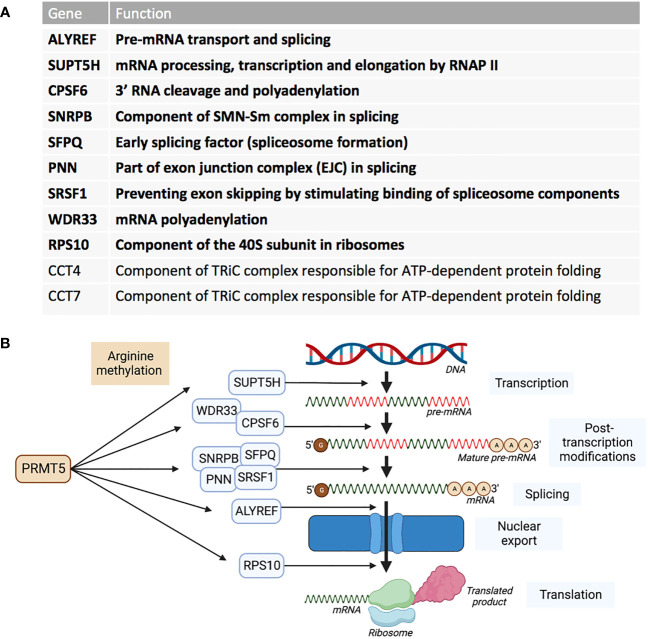

RNA sequencing of cells in which PRMT5 has been pharmacologically inhibited, demonstrated that a reduction in activity of PRMT5 caused an increase in detained introns (67). A detained intron (DI) describes the presence of a post-transcriptional intron in pre-mRNA that results in the transcript being detained within the nucleus (68). DI-containing transcripts are then either processed further by post-transcriptional splicing or degraded – leading to an overall reduction in the translated protein product (69). These types of alternative splicing upon PRMT5 downregulation in breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 were found to be enriched for transcription products associated with RNA processing such as splicing genes- HNRNPC, HNRNPH1, RBM5, RBM23, RBM39 and U2AF1 (56). In glioblastoma, PRMT5 inhibition globally increased abnormal splicing events, while mis-spliced transcripts were enriched in cell cycle progression pathways (70). Profiling the PRMT5 methylome identified 11 proteins that are essential in the proliferation of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) cells (37). Nine of these PRMT5 substrates are regulators of RNA metabolism and splicing ( Figure 3 ). AML cells were also shown to have increased DI-containing transcripts encoding the transcription factor ATF4 when PRMT5 was inhibited, decreasing levels of ATF4 and increasing oxidative stress and senescence (71). AML cells with genetic abnormalities in splicing gene Srsf2 were preferentially killed over Srsf2 WT cells when treated with PRMT5 inhibitors (72).

Figure 3.

PRMT5 substrates associated with AML proliferation outlined by Radzisheuskaya et al., 2019. (A) The eleven PRMT5 substrate genes identified as responsible for proliferation in AML and their functions. The genes in bold represent the nine genes that are involved in RNA metabolism and splicing. (B) The nine RNA metabolism and splicing proteins that are methylated by PRMT5 and whereabouts they act in the process of RNA metabolism and splicing.

PRMT5 methylation has been identified as an important regulating process for the DNA damage repair pathways. Under normal conditions, the TIP60 (KAT5) complex acetylates H4K16, displaces the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-promoting 53BP1 protein and directs DNA damage repair towards the homologous recombination (HR) pathway (54, 73). By contrast, PRMT5 deficiency leads to alternative splicing of TIP60, impairing acetyltransferase activity (73). In addition, PRMT5 directly methylates the TIP60 complex cofactor protein RUVBL1 that is essential for accurate complex function (54). In a PRMT5-deficient environment, the TIP60 complex cannot function to promote HR and consequently error-prone NHEJ is favoured – a potential explanation for upregulation of p53 seen previously (65). When MAT2A or PRMT5 were inhibited pharmacologically, Kalev et al. observed an increase in R-loop nuclear signals, micronuclei and the DNA damage marker γH2AX (74). The formation of R-loops and consequent DNA damage (and vice-versa) was attributed to irregular splicing arising from lack of PRMT5 activity. Furthermore, this study showed an increase in DIs located in the key DNA damage repair regulator ATM, and FA pathway transcripts FANCL, FANCA and FANCD2, and an associated reduction in protein levels. FA pathway proteins and ATM facilitate HR upon DNA damage (75).

4. The function of MAT2A

MAT2A was identified as a top synthetically-lethal hit in three independent shRNA screens in MTAP-negative cell lines (18–20). The methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) enzymes are a family of three proteins that are involved in the synthesis of the molecule SAM (76). The MAT2A substrates methionine and ATP are processed to produce SAM via an adenosine intermediate (77). SAM can then be utilised by methyltransferases, such as PRMT5, for downstream methylation processes. The enhanced expression and activity of MAT2A results in an elevated production of SAM and has been associated with tumour progression in liver cancer (78), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (79, 80) and colorectal cancer (81, 82). Therefore, targeting MAT2A as a possible strategy for treating cancers (especially in MTAP-negative cancers) may reduce tumour growth.

5. Pharmacological PRMT5/MAT2A inhibition and selectivity for MTAP-deficient cells

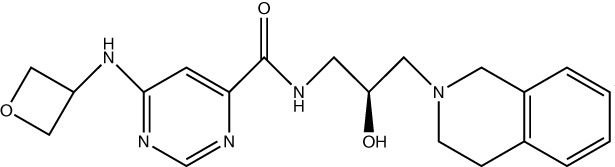

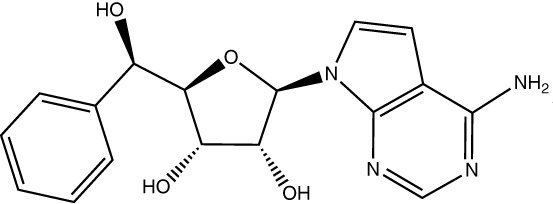

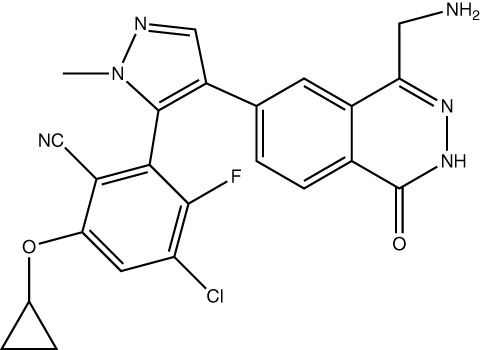

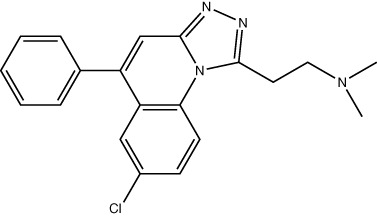

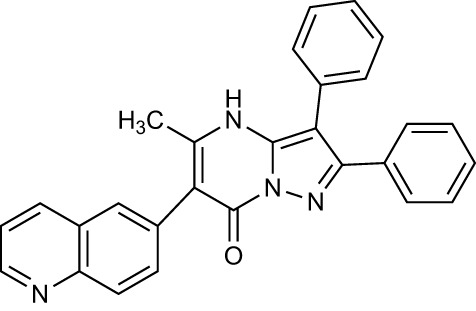

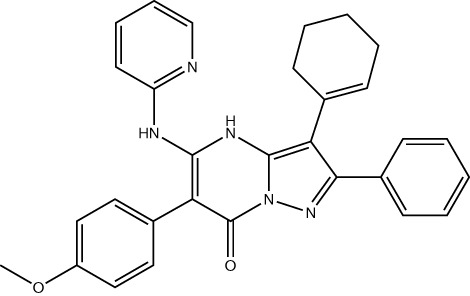

A limiting factor to targeting PRMT5 directly is its important role in normal tissue function, but a synthetically lethal interaction with an MTAP-negative background should, in principle, provide a suitable therapeutic window. However, since MTA and SAM bind competitively to the substrate binding pocket of PRMT5 (19), MTA accumulation downstream of MTAP loss is a ‘double-edged sword’ in the context of PRMT5 inhibition. A SAM-uncompetitive pharmacological inhibitor of PRMT5 (EPZ015666/GSK3326595) was shown to be an effective anti-proliferative agent in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) models with overexpression of PRMT5 (83). However, EPZ015666 showed no substantial antiproliferative effect in endogenous and engineered MTAP-negative cell lines (18) due to increased levels of MTA outcompeting SAM binding; PRMT5 has a lower affinity for SAM than MTA (19, 25, 84). Additional compounds found to bind in a SAM/MTA-competitive manner, including LLY-283 (85) and JNJ-64619178 (86, 87), are also less effective in conditions of elevated MTA levels. Subsequently compounds have recently been produced that interact with PRMT5 when bound to MTA, and which selectively target MTAP-negative cancer cells to varying degrees or elicit a synergistic effect in a MTAP-negative background (88, 89). Also, interaction between PRMT5 and SAPs can be targeted by BRD0639 and blocking this interaction reduced PRMT5 function and perturbed cellular growth in MTAP-negative cell lines in vitro (90). Several PRMT5 inhibitors are now in early-stage clinical trials for different types of cancers ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 inhibitors.

| Drug Name | Structure | Clinical trial identifier (if applicable) |

Clinical trial stage (if applicable) |

Cancer type in trial (if applicable) |

Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPZ015666/ GSK3326595 |

|

NCT04676516 | Phase 2 | Early-stage breast cancer | (83) |

| LLY-283 |

|

(85) | |||

| JNJ-64619178 |

|

NCT03573310 | Phase 1 | Neoplasms, Solid tumour (adult), Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Myelodysplastic Syndromes | (86, 87) |

| BRD0639 |

|

(90) | |||

| AMG193 | Not published | NCT05094336 | Phase 1/2 | MTAP-null solid tumours | No publications |

| TNG908 | Not published | NCT05275478 | Phase 1/2 | MTAP-null solid tumours | No publications |

| SCR-6920 | Not published | NCT05528055 | Phase 1 | Solid tumour, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | No publications |

| PRT543 | Not published | NCT03886831 | Phase 1 | Solid tumours/ lymphomas, Haematological malignancies |

No publications |

| PRT811 | Not published | NCT04089449 | Phase 1 | Advanced solid tumour, Recurrent Glioma | No publications |

| MRTX1719 |

|

NCT05245500 | Phase 1/2 | Mesothelioma, Non-small cell lung cancer, Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, Solid tumours, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | (89) |

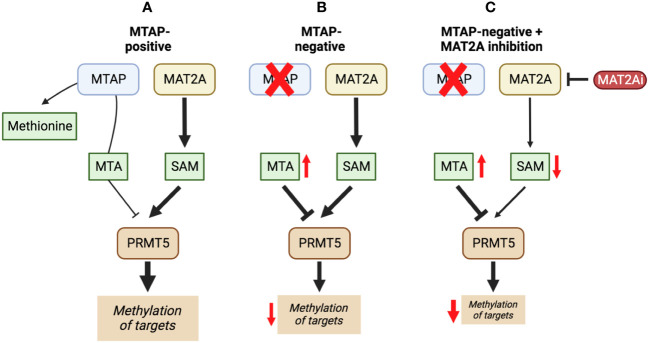

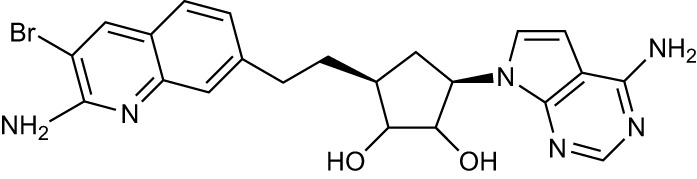

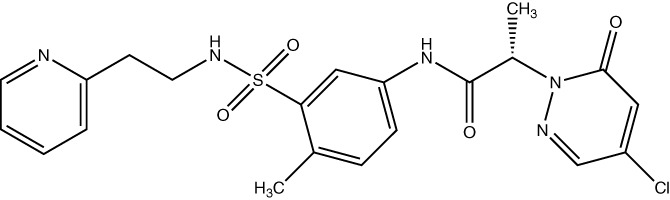

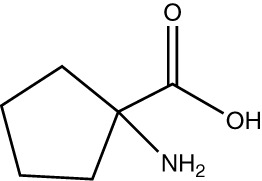

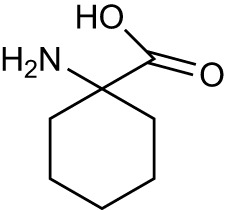

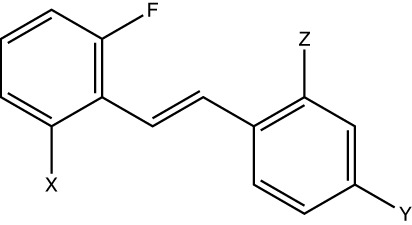

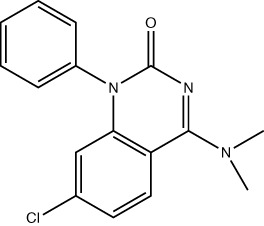

Inhibiting MAT2A and reducing SAM levels has been proposed to cause PRMT5 inhibition both by removing its substrate and, in the case of MTAP-negative tumours, by providing a greater opportunity for MTA binding. Inhibiting MAT2A will therefore act to reduce protein methylation via PRMT5 ( Figure 4 ), in addition to broader metabolism (nucleotide synthesis, glutathione synthesis, etc). Targeting MAT2A rather than PRMT5 directly has shown a greater selectivity for cells with an MTAP-negative background (19). As the MAT2A paralog MAT1A is the primary SAM producer in hepatic tissues there is also a lower risk of liver toxicity with selective inhibition of MAT2A (76). The first inhibitors of MAT2A ( Table 3 ) were substrate-competitive molecules adapted from the structure of methionine - cycloleucine (91) and aminobicyclohexanecarboxylic acid (92). However, these analogues did not possess the potency and binding specificity for an effective and accurate therapy. The development of small molecules called FIDAS (fluorinated N,N-dialkylaminostilbene) agents showed an improved potency down to low nanomolar concentrations (93, 94). However, the compounds did not show high selectivity for MAT2A at higher drug dosages in vitro (94). A non-substrate competitive inhibitor, PF-9366, showed promise with a higher potency for MAT2A; this molecule competitively binds to an allosteric site which mediates interactions with the binding partner MAT2B (95). MAT2B has been suggested to regulate MAT2A in low methionine or high methionine conditions by respectively activating or inhibiting MAT2A activity (95). Other data have suggested that the presence of MAT2B does not affect MAT2A activity but does improve MAT2A stability and longevity in low substrate concentrations (98). Therefore, these data suggest that the capacity of MAT2A inhibition via PF-9366 may be dependent on MAT2B levels or methionine/ATP availability. Extended PF-9366 and cycloleucine treatment led to adaptation in cultured cell lines resulting in an upregulation of MAT2A expression, indicating possible resistance mechanisms (95).

Figure 4.

The inhibition of MAT2A exacerbates the reduction in PRMT5 activity present in a MTAP-negative background. Here, we show the changes in PRMT5 activity over different genetic backgrounds [MTAP-positive (A) and MTAP-negative (B)] and in an MATZA inhibited state within an MTAP-negative background (C). The outcome of these differences is a change in levels of methylation of PRMT5 targets.

Table 3.

Methionine adenosyltransferase II alpha inhibitors.

| Drug Name | Structure | Clinical trial identifier (if applicable) | Clinical trial stage (if applicable) | Cancer type in trial (if applicable) |

Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloleucine |

|

(91) | |||

| Aminobicyclo-hexane-carboxylic acid |

|

(92) | |||

| FIDAS agents (generic structure) - X, Y and Z are variable groups |

|

(93, 94) | |||

| PF-9366 |

|

(95) | |||

| AGI-25696 |

|

(96) | |||

| AG-270 (S095033) |

|

NCT03435250, NCT05312372 | Phase 1, Phase 1/2 |

Advanced solid tumours, Lymphoma, Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | (74) |

| Compound 28 |

|

(97) | |||

| IDE397 | Not published | NCT04794699 | Phase 1 | Solid tumour | No publications |

A series of further non-substrate competitive inhibitors was developed, including an orally bioavailable in vivo candidate molecule AGI-25696 (96). AGI-25696 was a poor candidate for human treatment due to high plasma protein binding and consequent low tissue uptake. By masking polarity internally and reducing the hydrogen donors of the molecule, the absorption was improved, and potency maintained (96). The final compound produced, AG-270, has been shown to be effective in reducing proliferation both within in vitro cell lines and in vivo xenograft models (74). AG-270 is being investigated in a MTAP-negative solid tumour and lymphoma phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03435250) and a phase 1/2 clinical trial in advanced and metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (NCT05312372). A similar study used a fragment approach to design new MAT2A inhibitors that show a high potency and functionality in vivo (97). The study resulted in a drug called compound 28, showed comparable features to AG-270 in that both are orally bioavailable and bind to the MAT2B allosteric region of MAT2A. Both AG-270 (74) and compound 28 (97) showed high potency in vitro; reducing proliferation and SDMA markers in a HCT116 MTAP-negative background. In a xenograft study of HCT116 MTAP-negative tumours AG-270 resulted in 75% growth inhibition (96), while treatment with compound 28 led to complete tumour stasis (97). Another small molecule MAT2A inhibitor by IDEAYA (IDE397) is also in phase 1 clinical trials for MTAP-negative solid-tumours (NCT04794699).

PRMT5 clinical trials for PRT543 (NCT03886831) and GSK3326595 (NCT04676516) have been completed and have reported disappointing clinical responses to the monotherapy (99, 100). Just one of the baseline 49 patients achieved complete remission after treatment with PRT543 (101) and GSK has discontinued the trial with GSK3326595 (100). Even though these studies have not reported results selectively in an MTAP-negative tumour background, other clinical evidence is emerging that MTAP-negativity does not predict intra tumoral MTA accumulation as seen in model systems (102). This suggests that despite substantive pre-clinical evidence, this genomic biomarker may not sufficiently predict response to MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibition sensitivity in the clinic.

6. Determinants of response to MAT2A/PRMT5 targeting beyond MTAP status as a route to effective treatment

The selective sensitivity of MTAP-negative cancer to MAT2A or PRMT5 inhibition is argued to result from abnormally high levels of MTA. While high MTA levels have been demonstrated extensively in MTAP-negative cancer cells in vitro (18–20), lower than expected levels of MTA have been observed in vivo (102). Barekatain et al. conducted metabolomic analysis of 17 primary glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) tumours, xenograft tumours derived from a series of GBM lines and a 50 GBM tumour metabolomic dataset, which overall showed no significant difference in MTA levels between MTAP-negative and MTAP-positive primary tumours (102). Consequently, there was not the expected PRMT5 inhibition in primary MTAP-negative tumours (shown by a lack of significant reduction in SDMA markers). Barekatain et al. showed evidence that MTA produced from the MTAP-negative tumour is being processed by the intratumour, MTAP-positive stromal cells. A noticeable finding highlighted that in vivo xenografts may not accurately model endogenous tumour response, as xenografts are less populated by stromal cells when comparing their histology to primary GBM tumour tissue (102). These challenges emphasise the importance of reproducible model systems that result in more “patient-like” models. Overall, this study suggests caution in the use of MTAP status as the sole predictive biomarker for identifying patients to receive MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitor therapy.

In general, metabolite levels are likely to differ between cultured cells in vitro and patient tumours in vivo, not least because the composition of common culture media and levels of oxygenation do not recapitulate the physiological environment where tumours form in the body (103). Furthermore, tissue lineage can also influence the metabolic phenotype of a tumour, even when they share the same oncogenic driver mutations (104). For example, it has been shown that the accumulation of MTA resulting from a homozygous MTAP deletion was only reproducible between cell lines when grown in a complete nutrient culture medium, and not when cultured in methionine- or cysteine-depleted media (105). Each cell line in this study demonstrated distinct metabolic profiles upon amino acid restriction, which were clustered more by tissue type than MTAP status. These observations also imply that nutrient supply, including dietary methionine or cysteine, could add to patient-to-patient variability in response to therapy targeting the MAT2A/PRMT5/MTAP axis and that combining MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibition with nutrient depletion could result in enhanced responses. Reducing the level of methionine in the body, either enzymatically (106) or through dietary restriction (107), has been shown to reduce tumour volume or increase life span in mice, respectively. Methionine depletion has also been shown to be tolerable with no clinical toxicity in patients (108). When polyamine synthesis is increased in MTAP-deleted cells, it can cause reactive oxygen species (ROS) to form and lead to cell death by ferroptosis through lipid oxidation. This effect is amplified by a reduction in cysteine, which impairs the transsulfuration pathway that normally helps to resolve lipid oxidation and reduces the production of glutathione (109).

Given the fundamental importance of SAM levels or arginine methylation in normal tissue function and the systemic impact of MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitors to lower these, it is important to consider how the combination of such agents with standard-of-care therapies can be rationally designed to benefit from synergy, reduce dosage and alleviate on-target toxicity. In particular, difficult-to-treat cancers could benefit from combination approaches with MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitors alongside compounds that target the DNA damage response (110).

As described above, PRMT5 activity results in alternative splicing of the transcripts of key DNA damage repair proteins, such as ATM and FA family members, which facilitate repair of double strand DNA breaks, e.g. induced by inter-strand crosslinking. The combination of PRMT5 inhibitors and interstrand crosslinking agents induced an increase in unrepaired inter-strand crosslinks and lead to greater genomic instability (48), implying that MAT2A or PRMT5 inhibitors create a deficiency in the HR DNA repair pathway. Tumours with a defective HR pathway, such as BRCA2-negative breast and ovarian cancer, become dependent on PARP1-mediated repair pathways (111). This finding suggests that MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibition may act synergistically in combination with PARP inhibitors, as has been reported in one study of AML (73). PARP inhibitors have also shown significant synergy with type I PRMT inhibitors in NSCLC and in ovarian cancer, where type I PRMT inhibition re-sensitised resistant PEO4 ovarian cancer cells to PARP inhibitor treatment in vitro (112). Combination therapy using well characterised chemotherapies alongside PRMT5 inhibitors has shown promising results by targeting both PRMT5 inhibitor sensitive and resistant cells simultaneously. In one study, PRMT5 inhibition resistance was found to be associated with the upregulation of the microtubule regulator, stathmin 2 (STMN2) (113). Upregulation of STMN2 was found to be essential for resistance, and was also responsible for sensitivity to taxanes, such as paclitaxel (113). A combination of MAT2A inhibitors and taxanes was also shown to produce synergy when treating engineered (HCT116) and intrinsically (KP4) MTAP-negative cell lines (74).

Pharmacological inhibition of PRMT5 has been suggested to combine effectively with anti-PD1 immune checkpoint therapy (ICT) drugs in different types of cancers. In murine melanoma cell lines, PRMT5 was shown to methylate IFN-γ-inducible protein 204 (IFI16/IFI204) and negatively regulate NLRC5 transcription (49). Pharmacological inhibition or shRNA knockdown of PRMT5 increased production of type-I interferons by inhibiting IFI16 (IFI204) and increased NLRC5-promotion of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I antigen presentation genes (49). PRMT5 inhibition was later reported to induce lymphocyte infiltration and MHC II expression in mouse liver HCC tumours, which was demonstrated by an increase in CD45.1, CD4 and CD8 staining in fixed liver tumours and up-regulation of H2-Ab1, Cd74 and MHC II transactivator Ciita at the mRNA level (45). The combination of a PRMT5 inhibitor and anti-PD1 therapy produced a significant reduction in tumour volume and an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration compared to either therapy alone in vivo (45). In contrast, PRMT5 inhibition has also been reported to promote PD-L1 expression in lung cancer and ultimately disrupt antitumour immunity by increasing the marker for immune inhibition (114). While combining PRMT5 inhibition with PD-L1 therapy has potential benefits, it has been reported that the MTA-rich environment in MTAP-negative cancer cells stimulate the immunosuppressive (M2) state in macrophages through activation of the adenosine A2B receptor (115), thus inhibiting immune invasion. SAM and MTA secreted by tumours can reduce global chromatin accessibility in T cells, leading to dysfunction that may contribute to a poor anti-tumour immune response (116). As such, investigating the impact of MAT2A inhibitors on the function of tumour-associated T cells may provide additional insight into how the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors could be improved.

7. Conclusions

Deletion of MTAP is frequently observed in a wide variety of cancers due to its proximity to the key tumour suppressor gene CDKN2A. The codeletion of MTAP provides a selectable marker for the identification of cancer patients who might benefit from targeting of methionine metabolism and/or protein methylation due to accumulation of the metabolite MTA. Here we have reviewed current pharmacological methods of targeting SAM production via MAT2A inhibition and direct PRMT5 inhibition (both of which reduce PRMT5-specific methylation reactions) and reported evidence for and against the selectivity of these treatments for MTAP-negative tumours. Future generations of drugs that target PRMT5 activity in an MTAP-negative background must focus on maximising their selectivity for inhibiting PRMT5 specifically within the cancer cell (i.e. when PRMT5 is bound to MTA). Moving forward, to best understand the population of patients that will benefit from therapeutic treatment with MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitors we require a greater understanding of the molecular rewiring after inhibition. Our current understanding of the downstream effects of PRMT5 inhibition include the impairment of pre-mRNA splicing and DNA damage repair, co-treatment of cancers with agents that target these pathways such as PARP inhibitors and chemotherapy, is potentially synergistic. Such a strategy provides an alternative rationale for the use of MAT2A/PRMT5 inhibitors beyond synthetic lethality with MTAP loss and presents additional predictive biomarkers for future clinical development of combination treatments.

Author contributions

CB: Writing – original draft. CB: Writing – review & editing. IM: Writing – review & editing. HK: Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Muireann Coen, Valentina Fogal and Anke Nijhuis for evaluating this review article and the entire Cancer Metabolism & Systems Toxicology Group for their support. Schematic images were created with BioRender.com.

Funding Statement

The author declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. CB is supported by the Medical Research Council in collaboration with AstraZeneca (MR/R015732/1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Muller FL, Aquilanti EA, DePinho RA. Collateral lethality: A new therapeutic strategy in oncology. Trends Cancer (2015) 1(3):161–73. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Muller FL, Colla S, Aquilanti E, Manzo VE, Genovese G, Lee J, et al. Passenger deletions generate therapeutic vulnerabilities in cancer. Nature (2012) 488:7411. doi: 10.1038/nature14609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature (2010) . 463:7283. doi: 10.1038/nature08822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell PJ, Getz G, Korbel JO, Stuart JM, Jennings JL, Stein LD, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature (2020) 578:7793. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liégeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, et al. The Ink4a Tumor Suppressor Gene Product, p19Arf, Interacts with MDM2 and Neutralizes MDM2’s Inhibition of p53. Cell (1998) 92(6):713–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherr C. Cancer cell cycles. Science (1996) 274(5293):1672–4. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carrera CJ, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Carson DA. Assignment of the gene for methylthioadenosine phosphorylase to human chromosome 9 by mouse-human somatic cell hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1984) 81(9):2665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang H, Chen ZH, Savarese TM. Codeletion of the genes for p16INK4, methylthioadenosine phosphorylase, interferon-α1, interferon-β1, and other 9p21 markers in human Malignant cell lines. Cancer Genet Cytogenetics (1996) 86(1):22–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansen LJ, Sun R, Yang R, Singh SX, Chen LH, Pirozzi CJ, et al. MTAP loss promotes stemness in glioblastoma and confers unique susceptibility to purine starvation. Cancer Res (2019) 79(13):3383–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alhalabi O, Zhu Y, Hamza A, Qiao W, Lin Y, Wang RM, et al. Integrative clinical and genomic characterization of MTAP-deficient metastatic urothelial cancer. Eur Urol Oncol (2021) 6(2):228–32. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2021.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su CY, Chang YC, Chan YC, Lin TC, Huang MS, Yang CJ, et al. MTAP is an independent prognosis marker and the concordant loss of MTAP and p16 expression predicts short survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol (2014) 40(9):1143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fitchen JH, Riscoe MK, Dana BW, Lawrence HJ, Ferro AJ. Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase deficiency in human leukemias and solid tumors. Cancer Res (1986) 46(10):5409–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Traweek ST, Riscoe MK, Ferro AJ, Braziel RM, Magenis RE, Fitchen JH. Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase deficiency in acute leukemia: pathologic, cytogenetic, and clinical features. Blood (1988) 71(6):1568–73. doi: 10.1182/blood.V71.6.1568.1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smaaland R, Schanche JS, Kvinnsland S, Høstmark J, Ueland PM. Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat (1987) 9(1):53–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01806694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pegg AE, Williams-Ashman HG. Phosphate-stimulated breakdown of 5′-methylthioadenosine by rat ventral prostate. Biochem J (1969) 115(2):241–7. doi: 10.1042/bj1150241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toohey JI. Methylthioadenosine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency in methylthio-dependent cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (1978) 83(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(78)90393-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamatani N, Carson DA. Abnormal regulation of methylthioadenosine and polyamine metabolism in methylthioadenosine phosphorylase-deficient human leukemic cell lines. Cancer Res (1980) 40(11):4178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mavrakis KJ, McDonald ER, Schlabach MR, Billy E, Hoffman GR, deWeck A, et al. Disordered methionine metabolism in MTAP/CDKN2A-deleted cancers leads to dependence on PRMT5. Science (1979) 351(6278):1208–13. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marjon K, Cameron MJ, Quang P, Clasquin MF, Mandley E, Kunii K, et al. MTAP deletions in cancer create vulnerability to targeting of the MAT2A/PRMT5/RIOK1 axis. Cell Rep (2016) 15(3):574–87. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kryukov G, Wilson FH, Ruth JR, Paulk J, Tsherniak A, Marlow SE, et al. MTAP deletion confers enhanced dependency on the PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase in cancer cells. Science (2016) 351(6278):1214–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC, Gonzalez S, Rosebrock D, et al. The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature (2020) 578(7793):122–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1907-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakata SF, Shelly LL, Ruppert S, Schutz G, Chou JY. Cloning and expression of murine S-adenosylmethionine synthetase. J Biol Chem (1993) 268(19):13978–86. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85198-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujimoto S, Okumura1 S, Matsuda1 K, Horikawa1 Y, Maeda2 M, Kawasaki2 K, et al. Effect of fasting on methionine adenosyltransferase expression and the methionine cycle in the mouse liver. J Nutr Sci VitaminoI (2005) 51:118–23. doi: 10.3177/JNSV.51.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guderian G, Peter C, Wiesner J, Sickmann A, Schulze-Osthoff K, Fischer U, et al. RioK1, a new interactor of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5), competes with pICln for binding and modulates PRMT5 complex composition and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(3):1976–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun L, Wang M, Lv Z, Yang N, Liu Y, Bao S, et al. Structural insights into protein arginine symmetric dimethylation by PRMT5. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2011) 108(51):20538–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106946108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ho MC, Wilczek C, Bonanno JB, Xing L, Seznec J, Matsui T, et al. Structure of the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5-MEP50 reveals a mechanism for substrate specificity. PloS One (2013) 8(2):e57008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blanc RS, Richard S. Arginine methylation: the coming of age. Mol Cell (2017) 65(1):8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol Cell (2009) 33(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lorenzo A, Bedford MT. Histone arginine methylation. FEBS Lett (2011) 585(13):2024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fabbrizio E, Messaoudi S, Polanowska J, Paul C, Cook JR, Lee JH, et al. Negative regulation of transcription by the type II arginine methyltransferase PRMT5. EMBO Rep (2002) 3(7):641–5. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mulvaney KM, Blomquist C, Acharya N, Li R, Ranaghan MJ, O’Keefe M, et al. Molecular basis for substrate recruitment to the PRMT5 methylosome. Mol Cell (2021) 81(17):3481–3495.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Musiani D, Bok J, Massignani E, Wu L, Tabaglio T, Ippolito MR, et al. Proteomics profiling of arginine methylation defines PRMT5 substrate specificity. Sci Signaling (2019) 12(575):8388. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aat8388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stopa N, Krebs JE, Shechter D. The PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase: many roles in development, cancer and beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci (2015) 72(11):2041–59. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1847-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chiang K, Zielinska AE, Shaaban AM, Sanchez-Bailon MP, Jarrold J, Clarke TL, et al. PRMT5 is a critical regulator of breast cancer stem cell function via histone methylation and FOXP1 expression. Cell Rep (2017) 21(12):3498–513. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu M, Yao B, Gui T, Guo C, Wu X, Li J, et al. PRMT5-dependent transcriptional repression of c-Myc target genes promotes gastric cancer progression. Theranostics (2020) 10(10):4437–52. doi: 10.7150/thno.42047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yan F, Alinari L, Lustberg ME, Martin LK, Cordero-Nieves HM, Banasavadi-Siddegowda Y, et al. Genetic validation of the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 as a candidate therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Cancer Res (2014) 74(6):1752–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Radzisheuskaya A, v. SP, Grinev V, Lorenzini E, Kovalchuk S, Shlyueva D, et al. PRMT5 methylome profiling uncovers a direct link to splicing regulation in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2019) 26(11):999–1012. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0313-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gu Z, Gao S, Zhang F, Wang Z, Ma W, Davis RE, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 is essential for growth of lung cancer cells. Biochem J (2012) 446(2):235–41. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koh CM, Bezzi M, Low DHP, Ang WX, Teo SX, Gay FPH, et al. MYC regulates the core pre-mRNA splicing machinery as an essential step in lymphomagenesis. Nature (2015) 523(7558):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature14351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bao X, Zhao S, Lius T, Liu Y, Liu Y, Yang X. Overexpression of PRMT5 promotes tumor cell growth and is associated with poor disease prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Histochem Cytochem (2013) 61(3):206–17. doi: 10.1369/0022155413475452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qin Y, Hu Q, Xu J, Ji S, Dai W, Liu W, et al. PRMT5 enhances tumorigenicity and glycolysis in pancreatic cancer via the FBW7/cMyc axis. Cell Communication Signaling (2019) 17(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0344-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deng X, Shao G, Zhang HT, Li C, Zhang D, Cheng L, et al. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 functions as an epigenetic activator of the androgen receptor to promote prostate cancer cell growth. Oncogene (2016) 36(9):1223–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang L, Shao G, Shao J, Zhao J. PRMT5-activated c-Myc promote bladder cancer proliferation and invasion through up-regulating NF-κB pathway. Tissue Cell (2022) 76:101788. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2022.101788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lacroix M, el Messaoudi S, Rodier G, le Cam A, Sardet C, Fabbrizio E. The histone-binding protein COPR5 is required for nuclear functions of the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT5. EMBO Rep (2008) 9(5):452–8. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luo Y, Gao Y, Liu W, Yang Y, Jiang J, Wang Y, et al. Myelocytomatosis-protein arginine N-methyltransferase 5 axis defines the tumorigenesis and immune response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (2021) 74(4):1932–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.31864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen H, Lorton B, Gupta V, Shechter D. A TGFβ-PRMT5-MEP50 axis regulates cancer cell invasion through histone H3 and H4 arginine methylation coupled transcriptional activation and repression. Oncogene (2017) 36(3):373–86. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cho EC, Zheng S, Munro S, Liu G, Carr SM, Moehlenbrink J, et al. Arginine methylation controls growth regulation by E2F-1. EMBO J (2012) 31(7):1785–97. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Du C, Li SW, Singh SX, Roso K, Sun MA, Pirozzi CJ, et al. Epigenetic regulation of fanconi anemia genes implicates PRMT5 blockage as a strategy for tumor chemosensitization. Mol Cancer Res (2021) 19(12):2046–56. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim H, Kim H, Feng Y, Li Y, Tamiya H, Tocci S, et al. PRMT5 control of cGAS/STING and NLRC5 pathways defines melanoma response to antitumor immunity. Sci Trans Med (2020) 12(551):5683. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz5683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang X, Zeng Z, Jie X, Wang Y, Han J, Zheng Z, et al. Arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 methylates and destabilizes Mxi1 to confer radioresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett (2022) 532:215594. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pal S, Vishwanath SN, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sif S. Human SWI/SNF-associated PRMT5 methylates histone H3 arginine 8 and negatively regulates expression of ST7 and NM23 tumor suppressor genes. Mol Cell Biol (2004) 24(21):9630. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9630-9645.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jansson M, Durant ST, Cho EC, Sheahan S, Edelmann M, Kessler B, et al. Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat Cell Biol (2008) 10(12):1431–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li Y, Chitnis N, Nakagawa H, Kita Y, Natsugoe S, Yang Y, et al. PRMT5 is required for lymphomagenesis triggered by multiple oncogenic drivers. Cancer Discovery (2015) 5(3):288–303. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Clarke TL, Sanchez-Bailon MP, Chiang K, Reynolds JJ, Herrero-Ruiz J, Bandeiras TM, et al. PRMT5-dependent methylation of the TIP60 coactivator RUVBL1 is a key regulator of homologous recombination. Mol Cell (2017) 65(5):900–916.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gonsalvez GB, Tian L, Ospina JK, Boisvert FM, Lamond AI, Matera AG. Two distinct arginine methyltransferases are required for biogenesis of Sm-class ribonucleoproteins. J Cell Biol (2007) 178(5):733. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rengasamy M, Zhang F, Vashisht A, Song WM, Aguilo F, Sun Y, et al. The PRMT5/WDR77 complex regulates alternative splicing through ZNF326 in breast cancer. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45(19):11106–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer (2002) 2(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zheng S, Moehlenbrink J, Lu YC, Zalmas LP, Sagum CA, Carr S, et al. Arginine methylation-dependent reader-writer interplay governs growth control by E2F-1. Mol Cell (2013) 52(1):37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barczak W, Jin L, Carr SM, Munro S, Ward S, Kanapin A, et al. PRMT5 promotes cancer cell migration and invasion through the E2F pathway. Cell Death Dis (2020) 11(7):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02771-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Will CL, Lührmann R. Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2001) 13(3):290–301. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00211-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seng CO, Magee C, Young PJ, Lorson CL, Allen JP. The SMN structure reveals its crucial role in snRNP assembly. Hum Mol Genet (2015) 24(8):2138–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Friesen WJ, Massenet S, Paushkin S, Wyce A, Dreyfuss G. SMN, the product of the spinal muscular atrophy gene, binds preferentially to dimethylarginine-containing protein targets. Mol Cell (2001) 7(5):1111–7. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00244-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Friesen WJ, Paushkin S, Wyce A, Massenet S, Pesiridis GS, van Duyne G, et al. The methylosome, a 20S complex containing JBP1 and pICln, produces dimethylarginine-modified sm proteins. Mol Cell Biol (2001) 21(24):8289–300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8289-8300.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Close P, East P, Dirac-Svejstrup AB, Hartmann H, Heron M, Maslen S, et al. DBIRD complex integrates alternative mRNA splicing with RNA polymerase II transcript elongation. Nature (2012) 484(7394):386–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bezzi M, Teo SX, Muller J, Mok WC, Sahu SK, Vardy LA, et al. Regulation of constitutive and alternative splicing by PRMT5 reveals a role for Mdm4 pre-mRNA in sensing defects in the spliceosomal machinery. Genes Dev (2013) 27(17):1903–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.219899.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gerhart SV, Kellner WA, Thompson C, Pappalardi MB, Zhang XP, Montes De Oca R, et al. Activation of the p53-MDM4 regulatory axis defines the anti-tumour response to PRMT5 inhibition through its role in regulating cellular splicing. Sci Rep (2018) 8(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28002-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Braun CJ, Stanciu M, Boutz PL, Patterson JC, Calligaris D, Higuchi F, et al. Coordinated splicing of regulatory detained introns within oncogenic transcripts creates an exploitable vulnerability in Malignant glioma. Cancer Cell (2017) 32(4):411–426.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Boutz PL, Bhutkar A, Sharp PA. Detained introns are a novel, widespread class of post-transcriptionally spliced introns. Genes Dev (2015) 29(1):63–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.247361.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bresson SM, Hunter OV, Hunter AC, Conrad NK. Canonical poly(A) polymerase activity promotes the decay of a wide variety of mammalian nuclear RNAs. PloS Genet (2015) 11(10):e1005610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sachamitr P, Ho JC, Ciamponi FE, Ba-Alawi W, Coutinho FJ, Guilhamon P, et al. PRMT5 inhibition disrupts splicing and stemness in glioblastoma. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21204-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Szewczyk MM, Luciani GM, Vu V, Murison A, Dilworth D, Barghout SH, et al. PRMT5 regulates ATF4 transcript splicing and oxidative stress response. Redox Biol (2022) 51:102282. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fong JY, Pignata L, Goy PA, Kawabata KC, Lee SCW, Koh CM, et al. Therapeutic targeting of RNA splicing catalysis through inhibition of protein arginine methylation. Cancer Cell (2019) 36(2):194–209.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hamard PJ, Santiago GE, Liu F, Karl DL, Martinez C, Man N, et al. PRMT5 regulates DNA repair by controlling the alternative splicing of histone-modifying enzymes. Cell Rep (2018) 24(10):2643–57. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kalev P, Hyer ML, Gross S, Konteatis Z, Chen CC, Fletcher M, et al. MAT2A inhibition blocks the growth of MTAP-deleted cancer cells by reducing PRMT5-dependent mRNA splicing and inducing DNA damage. Cancer Cell (2021) 39(2):209–224.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cai MY, Dunn CE, Chen W, Kochupurakkal BS, Nguyen H, Moreau LA, et al. Cooperation of the ATM and fanconi anemia/BRCA pathways in double-strand break end resection. Cell Rep (2020) 30(7):2402–2415.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lu SC, Mato JM. S-adenosylmethionine in liver health, injury, and cancer. Physiol Rev (2012) 92(4):1515–42. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Murray B, Antonyuk SV, Marina A, Lu SC, Mato JM, Samar Hasnain S, et al. Crystallography captures catalytic steps in human methionine adenosyltransferase enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2016) 113(8):2104–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510959113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Liu Q, Chen J, Liu L, Zhang J, Wang D, Ma L, et al. The X protein of hepatitis B virus inhibits apoptosis in hepatoma cells through enhancing the methionine adenosyltransferase 2A gene expression and reducing S-adenosylmethionine production. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(19):17168–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yang H, Huang ZZ, Wang J, Lu SC. The role of c-Myb and Sp1 in the up-regulation of methionine adenosyltransferase 2A gene expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. FASEB J (2001) 15(9):1507–16. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0040com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yang H, Sadda MR, Yu V, Zeng Y, Lee TD, Ou X, et al. Induction of human methionine adenosyltransferase 2A expression by tumor necrosis factor α. J Biol Chem (2003) 278(51):50887–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307600200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ito K, Ikeda S, Kojima N, Miura M, Shimizu-Saito K, Yamaguchi I, et al. Correlation between the expression of methionine adenosyltransferase and the stages of human colorectal carcinoma. Surg Today (2000) 30(8):706–10. doi: 10.1007/s005950070081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen H, Xia M, Lin M, Yang H, Kuhlenkamp J, Li T, et al. Role of methionine adenosyltransferase 2A and S-adenosylmethionine in mitogen-induced growth of human colon cancer cells. Gastroenterology (2007) 133(1):207–18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chan-Penebre E, Kuplast KG, Majer CR, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Wigle TJ, Johnston LD, et al. A selective inhibitor of PRMT5 with in vivo and in vitro potency in MCL models. Nat Chem Biol (2015) 11(6):432–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Antonysamy S, Bonday Z, Campbell RM, Doyle B, Druzina Z, Gheyi T, et al. Crystal structure of the human PRMT5:MEP50 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2012) 44):17960–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209814109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bonday ZQ, Cortez GS, Grogan MJ, Antonysamy S, Weichert K, Bocchinfuso WP, et al. LLY-283, a potent and selective inhibitor of arginine methyltransferase 5, PRMT5, with antitumor activity. ACS Medicinal Chem Lett (2018) 9(7):612–7. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wu T, Millar H, Gaffney D, Beke L, Mannens G, Vinken P, et al. Abstract 4859: JNJ-64619178, a selective and pseudo-irreversible PRMT5 inhibitor with potent in vitro and in vivo activity, demonstrated in several lung cancer models. Cancer Res (2018) 78(13 Supplement):4859–9. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-4859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Brehmer D, Beke L, Wu T, Millar HJ, Moy C, Sun W, et al. Discovery and pharmacological characterization of JNJ-64619178, a novel small molecule inhibitor of PRMT5 with potent anti-tumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther (2021) 20(12):2317–28. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Malik R, Park PK, Barbieri CM, Blat Y, Sheriff S, Weigelt CA, et al. Abstract 1140: A novel MTA non-competitive PRMT5 inhibitor. Cancer Res (2021) 81(13 Supplement):1140–0. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-1140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smith CR, Aranda R, Bobinski TP, Briere DM, Burns AC, Christensen JG, et al. Fragment-based discovery of MRTX1719, a synthetic lethal inhibitor of the PRMT5•MTA complex for the treatment of MTAP-deleted cancers. J Medicinal Chem (2022) 65(3):1749–66. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. McKinney DC, McMillan BJ, Ranaghan MJ, Moroco JA, Brousseau M, Mullin-Bernstein Z, et al. Discovery of a first-in-class inhibitor of the PRMT5–substrate adaptor interaction. J Medicinal Chem (2021) 64(15):11148–68. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lombardini JB, Coulter AW, Talalay P. Analogues of methionine as substrates and inhibitors of the methionine adenosyltransferase reaction. Mol Pharmacol (1970) 6(5):481–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lombardini JB, Sufrin JR. Chemotherapeutic potential of methionine analogue inhibitors of tumor-derived methionine adenosyltransferases. Biochem Pharmacol (1983) 32(3):489–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90528-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhang W, Sviripa V, Chen X, Shi J, Yu T, Hamza A, et al. N-dialkylaminostilbenes repress colon cancer by targeting methionine S-adenosyltransferase 2A. ACS Chem Biol (2013) 8(4):796–803. doi: 10.1021/cb3005353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sviripa VM, Zhang W, Balia AG, Tsodikov OV, Nickell JR, Gizard F, et al. 2′,6′-dihalostyrylanilines, pyridines, and pyrimidines for the inhibition of the catalytic subunit of methionine S-adenosyltransferase-2. J Medicinal Chem (2014) 57(14):6083–91. doi: 10.1021/jm5004864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Quinlan CL, Kaiser SE, Bolaños B, Nowlin D, Grantner R, Karlicek-Bryant S, et al. Targeting S-adenosylmethionine biosynthesis with a novel allosteric inhibitor of Mat2A. Nat Chem Biol (2017) 13(7):785–92. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Konteatis Z, Travins J, Gross S, Marjon K, Barnett A, Mandley E, et al. Discovery of AG-270, a first-in-class oral MAT2A inhibitor for the treatment of tumors with homozygous MTAP deletion. J Medicinal Chem (2021) 64(8):4430–49. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. de Fusco C, Schimpl M, Börjesson U, Cheung T, Collie I, Evans L, et al. Fragment-based design of a potent MAT2a inhibitor and in vivo evaluation in an MTAP null xenograft model. J Med Chem (2021) 64:6826. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bailey J, Douglas H, Masino L, Carvalho LPS, Argyrou A. Human mat2A uses an ordered kinetic mechanism and is stabilized but not regulated by mat2B. Biochemistry (2021) 60(47):3621–32. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. GSK . Press Release. Full Year and Fourth Quarter 2021 (2021). Available at: https://www.gsk.com/media/7377/fy-2021-results-announcement.pdf (Accessed April 28, 2023).

- 100. Evaluate Vantage . GSK Raises More Questions About Synthetic Lethality (2022). Available at: https://www.evaluate.com/vantage/articles/news/deals/gsk-raises-more-questions-about-synthetic-lethality (Accessed April 28, 2023).

- 101. McKean M, Patel MR, Wesolowski R, Ferrarotto R, Stein EM, Shoushtari AN, et al. Abstract P039: A phase 1 dose escalation study of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibitor PRT543 in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther (2021) 20(12_Supplement):P039–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.TARG-21-P039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Barekatain Y, Ackroyd JJ, Yan VC, Khadka S, Wang L, Chen KC, et al. Homozygous MTAP deletion in primary human glioblastoma is not associated with elevation of methylthioadenosine. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24240-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ackermann T, Tardito S. Cell culture medium formulation and its implications in cancer metabolism. Trends Cancer (2019) 5(6):329–32. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mayers JR, Torrence ME, Danai LV, Papagiannakopoulos T, Davidson SM, Bauer MR, et al. Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science (2016) 353(6304):1161–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sanderson SM, Mikhael PG, Ramesh V, Dai Z, Locasale JW. Nutrient availability shapes methionine metabolism in p16/MTAP-deleted cells. Sci Adv (2019) 5(6):eaav7769. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav7769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kawaguchi K, Han Q, Li S, Tan Y, Igarashi K, Murakami T, et al. Efficacy of recombinant methioninase (rMETase) on recalcitrant cancer patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse models: A review. Cells (2019) 8(5):410. doi: 10.3390/cells8050410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Bárcena C, Quirós PM, Durand S, Mayoral P, Rodríguez F, Caravia XM, et al. Methionine restriction extends lifespan in progeroid mice and alters lipid and bile acid metabolism. Cell Rep (2018) 24(9):2392–403. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hoffman RM, Tan Y, Li S, Han Q, Zavala J, Zavala J. Pilot phase I clinical trial of methioninase on high-stage cancer patients: rapid depletion of circulating methionine. Methods Mol Biol (2019) 1866:231–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8796-2_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Zhang T, Bauer C, Newman AC, Uribe AH, Athineos D, Blyth K, et al. Polyamine pathway activity promotes cysteine essentiality in cancer cells. Nat Metab (2020) 2(10):1062. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0253-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lisio MA, Fu L, Goyeneche A, Gao ZH, Telleria C. High-grade serous ovarian cancer: basic sciences, clinical and therapeutic standpoints. Int J Med Sci (2019) 20(4):952. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature (2005) 434(7035):913–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Dominici C, Sgarioto N, Yu Z, Sesma-Sanz L, Masson JY, Richard S, et al. Synergistic effects of type I PRMT and PARP inhibitors against non-small cell lung cancer cells. Clin Epigenet (2021) 13(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01037-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mueller HS, Fowler CE, Dalin S, Moiso E, Udomlumleart T, Garg S, et al. Acquired resistance to PRMT5 inhibition induces concomitant collateral sensitivity to paclitaxel. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2021) 118(34):e2024055118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024055118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hu R, Zhou B, Chen Z, Chen S, Chen N, Shen L, et al. PRMT5 inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression and immuno-resistance in lung cancer. Front Immunol (2022) 0:722188. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.722188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hansen LJ, Yang R, Roso K, Wang W, Chen L, Yang Q, et al. MTAP loss correlates with an immunosuppressive profile in GBM and its substrate MTA stimulates alternative macrophage polarization. Sci Rep (2022) 12:1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07697-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Hung MH, Lee JS, Ma C, Diggs LP, Heinrich S, Chang CW, et al. Tumor methionine metabolism drives T-cell exhaustion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21804-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]