Abstract

The in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of S-4661, a new 1β-methylcarbapenem, were compared with those of imipenem, meropenem, biapenem, cefpirome, and ceftazidime. The activity of S-4661 against methicillin-susceptible staphylococci and streptococci was comparable to that of imipenem, with an MIC at which 90% of the strains tested were inhibited (MIC90) equal to 0.5 μg/ml or less. S-4661 was highly active against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, with MIC90s ranging from 0.032 to 0.5 μg/ml. Against imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S-4661 was the most active among test agents (MIC90, 8 μg/ml). Furthermore, S-4661 displayed a high degree of activity against many ceftazidime-, ciprofloxacin-, and gentamicin-resistant isolates of P. aeruginosa. The in vivo efficacy of S-4661 against experimentally induced infections in mice caused by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and drug-resistant P. aeruginosa, reflected its potent in vitro activity and high levels in plasma in mice. We conclude that S-4661 is a promising new carbapenem for the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive and -negative bacteria, including penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae and drug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

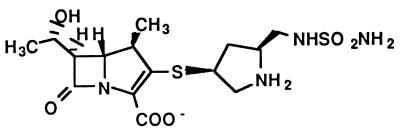

The antibacterial activity of carbapenems covers a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Carbapenems are also stable against a variety of plasmid-encoded and chromosomal β-lactamases. These drugs have been used in the treatment of serious forms of infections, such as complicated urinary tract infections, sepsis, pneumonia, endocarditis, and polymicrobial infections. Accordingly, adverse effects are likely to appear in the compromised host. In particular, serious renal toxicity and neurotoxicity may be induced following the use of carbapenems. Therefore, imipenem must be combined with cilastatin to prevent the breakdown of the former by dehydropeptidase I (5), and panipenem should likewise be combined with betamipron (10). Any modification of the carbapenems should be done for the purpose of decreasing their toxicity as well as maintaining or improving their antibacterial activities against a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. S-4661, (4R,5S,6S)-3-{[(3S,5S)-5-(sulfamoylaminomethyl)- pyrrolidin-3-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-4-methyl-7-oxo- 1-azabicyclo(3.2.0)hept-2-ene-2-carboxylic acid, is a new synthetic 1β-methylcarbapenem developed by Shionogi & Co. Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) (Fig. 1) (2). The new drug does not have the side effects described above in animal models. In the present study, we compared the in vitro and in vivo activities of S-4661 with those of imipenem, meropenem (11), biapenem (14), cefpirome, and ceftazidime.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of S-4661.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial agents.

S-4661 was supplied by Shionogi & Co. Imipenem and cilastatin were obtained from Banyu Pharmaceutical Co. (Tokyo, Japan), meropenem was from Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Co. (Osaka, Japan), biapenem was from Lederle Japan Co. (Tokyo, Japan), cefpirome and cefotaxime were from Hoechst Japan Co. (Osaka, Japan), ceftazidime was from Glaxo Co. (Tokyo, Japan), ciprofloxacin was from Bayer Yakuhin Co. (Osaka, Japan), gentamicin was from Schering-Plough K. K. (Osaka, Japan), and vancomycin was from Shinogi & Co.

Microorganisms.

Most clinical isolates used in this study were collected at Toho University Hospital and stored at −80°C in 10% skim milk until use.

Susceptibility testing.

The MIC was determined for each drug by a broth microdilution method according to the guidelines of the Japan Society for Chemotherapy (3, 4, 9). Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) was used for nonfastidious aerobic bacteria. For streptococci, enterococci, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Haemophilus influenzae, the medium was supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood, 5 mg of yeast extract (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) per ml, and 15 μg of NAD (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. The microdilution plates were inoculated with an automatic MIC-2000 inoculator (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Alexandria, Va.) so that the final inoculum was approximately 105 CFU/ml.

In vivo activity.

It is reported that S-4661, unlike imipenem, is stable against a variety of dehydropeptidases I (6). However, meropenem is stable against dehydropeptidase I from guinea pigs, pigs, dogs, and humans but unstable against that from mice and rats (1). In this study, we combined meropenem with cilastatin to make a comparison of the tested carbapenems in experimentally infected mice possible.

(i) Systemic infection.

The in vivo efficacy of S-4661 was determined in a mouse model of bacteremia. Male SLC/ICR mice weighing 18 to 22 g (Sankyo Labo Service Co., Tokyo, Japan) were intraperitoneally injected with a portion of a 0.5-ml dose of a bacterial suspension in 5% mucin (Difco). S-4661 and the other test antibiotics were each subcutaneously administered in a single dose 60 min after the induction of infection. The survival of the infected mice was monitored for 7 days, and the 50% effective dose (ED50) was determined by the probit method (8).

(ii) Pulmonary infection. (a) Penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae infection.

The therapeutic effect of S-4661 was tested in a mouse model of respiratory tract infection induced by S. pneumoniae TUH39 by the method described previously by Tsuji et al. (13). The test drug was subcutaneously administered, starting at 12 h after infection, twice daily for 2 days. Mortality was recorded over 14 days, and the ED50 was determined by the probit method (8).

(b) Penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae infection.

The therapeutic effects of S-4661 were tested in a mouse model of pulmonary infection induced by penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae TUH741 by the method described by Tateda et al. (12). Four-week-old male CBA/JNCrj mice (Charles River Japan, Inc., Tokyo) were anesthetized by a single intramuscular injection of a mixture of ketamine (6 mg/kg of body weight) and xylazine (1 mg/kg). The animals were infected by instillation of 0.05 ml of bacterial suspension containing 3.0 × 105 CFU. The suspension was prepared with physiological saline from Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco) supplemented with 30% horse serum. The test drug was subcutaneously administered, starting at 36 h after infection, three times a day for 3 days. The number of viable cells in the lungs (CFU per gram) was determined 20 h after administration of the last dose of the tested drugs.

Plasma drug levels.

A dose of 20 mg of each antibiotic per kg was subcutaneously injected into five mice in each group. A sample of heart blood was obtained 7.5, 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after drug administration. The level of biologically active drug in the plasma was determined by the bioassay method, with Escherichia coli 7437 as the indicator organism (7).

RESULTS

In vitro antibacterial activity.

The MICs at which 50 and 90% of the strains are inhibited (MIC50 and MIC90, respectively), as well as the range of MICs of each drug for a wide range of tested bacteria, are listed in detail in Table 1. S-4661 was potent against methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis (MIC90 for each, 0.063 μg/ml). The activity of S-4661 against these species was higher than that of the other agents tested except imipenem. S-4661 was two to four times more active than the other carbapenems against methicillin-resistant S. aureus. S-4661 was the most active compound against Streptococcus pyogenes. The activity of S-4661 against penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae was similar to that of imipenem but was higher than that of the other agents. Furthermore, S-4661 was potent against penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae, and its activity was similar to that of the other carbapenems (MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml). Compared with cephalosporins, S-4661 had activity similar to that of cefpirome against S. pyogenes and penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. However, it was more active than other cephalosporins against these gram-positive bacteria. S-4661 was more active against Enterococcus faecalis than all other tested agents except for imipenem. Similarly, all agents were less active against Enterococcus faecium than against E. faecalis.

TABLE 1.

In vitro activities of S-4661 and reference antibiotics against clinical isolates

| Organism (no. of strains) | Drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||||

| Methicillin-susceptible strains (30) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.016–0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Meropenem | 0.063–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.063–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.25–1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ceftazidime | 8–16 | 16 | 16 | |

| Methicillin-resistant strains (30) | S-4661 | 4–32 | 16 | 16 |

| Imipenem | 1–64 | 32 | 32 | |

| Meropenem | 8–32 | 16 | 32 | |

| Biapenem | 2–32 | 32 | 64 | |

| Cefpirome | 8–64 | 32 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 32–>128 | 128 | >128 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | ||||

| Methicillin-susceptible strains (46) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.008–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| Meropenem | 0.063–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.032–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftazidime | 4–16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Methicillin-resistant strains (27) | S-4661 | 8–32 | 16 | 32 |

| Imipenem | 8–128 | 64 | 128 | |

| Meropenem | 8–64 | 32 | 64 | |

| Biapenem | 8–64 | 64 | 128 | |

| Cefpirome | 4–64 | 32 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 16–>128 | 64 | >128 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (42) | S-4661 | ≦0.004 | ≦0.004 | ≦0.004 |

| Imipenem | ≦0.004–0.008 | ≦0.004 | 0.008 | |

| Meropenem | ≦0.004–0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Biapenem | ≦0.004–0.01 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.008–0.016 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | ||||

| Penicillin-susceptible strains (25) | S-4661 | 0.004–0.016 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Imipenem | 0.004–0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| Meropenem | 0.008–0.016 | 0.008 | 0.016 | |

| Biapenem | 0.008–0.016 | 0.008 | 0.016 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.008–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.125 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125–16 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| Penicillin | 0.016–0.063 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Penicillin-resistant strains (25) | S-4661 | 0.016–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.008–2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Meropenem | 0.016–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Biapenem | 0.016–4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.032–2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125–32 | 8 | 32 | |

| Penicillin | 0.125–4 | 1 | 2 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (32) | S-4661 | 0.016–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem | 0.016–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| Meropenem | 0.016–0.063 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Biapenem | 0.016–0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.032–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis (26) | S-4661 | 0.5–16 | 2 | 4 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–8 | 1 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 1–64 | 4 | 8 | |

| Biapenem | 1–32 | 4 | 8 | |

| Cefpirome | 2–128 | 8 | 32 | |

| Ceftazidime | >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Enterococcus faecium (25) | S-4661 | 0.5–>128 | 128 | >128 |

| Imipenem | 0.5–>128 | 128 | >128 | |

| Meropenem | 1–>128 | 128 | >128 | |

| Biapenem | 1–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Cefpirome | 1–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Ceftazidime | 32–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Escherichia coli (30) | S-4661 | 0.016–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem | 0.063–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Meropenem | 0.016–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| Biapenem | 0.032–0.063 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.016–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.063–1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (30) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.063–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Biapenem | 0.032–0.25 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.032–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.063–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca (38) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Biapenem | 0.032–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.008–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Proteus mirabilis (27) | S-4661 | 0.063–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–8 | 2 | 4 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–0.5 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–8 | 2 | 2 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.063–0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Proteus vulgaris (30) | S-4661 | 0.063–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–8 | 2 | 4 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.063–8 | 1 | 4 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.063–8 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–8 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Providencia rettgeri (21) | S-4661 | 0.063–1 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 0.5–2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–1 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.008–8 | 0.063 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–8 | 0.125 | 4 | |

| Morganella morganii (32) | S-4661 | 0.063–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 0.5–4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Meropenem | 0.063–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.063 | |

| Biapenem | 0.125–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.016–0.5 | 0.032 | 0.125 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–128 | 0.063 | 2 | |

| Citrobacter freundii (22) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Meropenem | 0.016–0.063 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Biapenem | 0.063–1 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.016–1 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25–128 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae (30) | S-4661 | 0.032–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 |

| Imipenem | 0.125–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| Meropenem | 0.016–0.125 | 0.032 | 0.063 | |

| Biapenem | 0.032–0.5 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.016–4 | 0.063 | 4 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.063–>128 | 0.25 | 128 | |

| Serratia marcescens (30) | S-4661 | 0.063–4 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–2 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–8 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Biapenem | 0.125–8 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.032–32 | 0.063 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125–128 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis (46) | S-4661 | 0.008–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem | 0.008–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Panipenem | ≦0.004–0.032 | 0.016 | 0.032 | |

| Meropenem | ≦0.004–0.008 | ≦0.004 | ≦0.004 | |

| Biapenem | 0.016–0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.125–2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.032–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae (50) | S-4661 | 0.032–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–16 | 1 | 4 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–0.5 | 0.063 | 0.25 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–16 | 1 | 4 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.016–0.125 | 0.063 | 0.125 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.063–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||||

| Imipenem-susceptible strains (83) | S-4661 | 0.063–8 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–8 | 1 | 8 | |

| Meropenem | 0.032–8 | 0.25 | 2 | |

| Biapenem | 0.125–8 | 0.5 | 4 | |

| Cefpirome | 2–>128 | 8 | 32 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5–128 | 2 | 32 | |

| Imipenem-resistant strains (32) | S-4661 | 2–16 | 8 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 16–32 | 16 | 32 | |

| Meropenem | 2–32 | 8 | 16 | |

| Biapenem | 8–32 | 16 | 32 | |

| Cefpirome | 8–64 | 32 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 1–64 | 32 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime-resistant strains (39) | S-4661 | 0.063–16 | 2 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.5–32 | 8 | 16 | |

| Meropenem | 0.063–32 | 4 | 16 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–32 | 8 | 32 | |

| Cefpirome | 32–>128 | 64 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 32–128 | 32 | 128 | |

| Ciprofloxacin-resistant strains (16) | S-4661 | 0.125–8 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–32 | 1 | 32 | |

| Meropenem | 0.25–16 | 0.5 | 8 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–32 | 0.5 | 32 | |

| Cefpirome | 2–>128 | 16 | >128 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5–128 | 8 | 64 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4–64 | 16 | 64 | |

| Gentamicin-resistant strains (37) | S-4661 | 0.063–16 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–32 | 1 | 16 | |

| Meropenem | 0.063–32 | 0.5 | 16 | |

| Biapenem | 0.25–32 | 0.5 | 32 | |

| Cefpirome | 2–>128 | 32 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.5–128 | 8 | 64 | |

| Gentamicin | 16–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Bordetella pertussis (52) | S-4661 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.25–4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| Biapenem | 0.5–8 | 2 | 4 | |

| Cefpirome | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Ceftazidime | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Burkholderia cepacia (25) | S-4661 | 4–16 | 8 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 8–32 | 16 | 32 | |

| Meropenem | 2–8 | 4 | 8 | |

| Biapenem | 4–16 | 8 | 16 | |

| Cefpirome | 16–>128 | 64 | 128 | |

| Ceftazidime | 2–16 | 4 | 8 | |

S-4661 was particularly active against members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and H. influenzae. The MIC90s for Escherichia, Klebsiella, Proteus, Providencia, Morganella, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, and Serratia spp. ranged from 0.063 to 0.5 μg/ml. The activity of S-4661 against these bacteria was two to eight times greater than that of imipenem and biapenem, but S-4661 was slightly less potent than meropenem. Against M. catarrhalis, S-4661 was two to four times more active than imipenem and biapenem but less active than meropenem. S-4661 was eight times more active against H. influenzae than imipenem and biapenem but two times less active than meropenem, cefpirome, and ceftazidime.

The MIC90s of S-4661 and meropenem for imipenem-susceptible P. aeruginosa (MIC, <8 μg/ml) were identical at 2 μg/ml. The MIC90s of imipenem, biapenem, and both cefpirome and ceftazidime for this organism were 8, 4, and 32 μg/ml, respectively. Against imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, S-4661 was two to four times more active than the other tested carbapenems. Furthermore, S-4661 displayed a high degree of activity against many of the ceftazidime-, ciprofloxacin-, and gentamicin-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates; its activity was similar to that of meropenem and higher than those of reference agents.

The activity of S-4661 against Bordetella pertussis was slightly less than that of meropenem and ceftazidime but similar to that of cefpirome. The MIC90s of imipenem and biapenem for B. pertussis were ≥1 μg/ml.

In vivo efficacy.

The in vivo efficacy of S-4661 against experimentally induced acute bacteremia in mice was compared with those of imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem-cilastatin, ceftazidime, and vancomycin (Table 2). The ED50 of S-4661 against S. aureus Smith was 0.066 mg/kg, which was almost the same as that of imipenem-cilastatin but lower than that of meropenem-cilastatin. The ED50 of ceftazidime was approximately 200 times greater than that of S-4661. On the other hand, S-4661 was more effective than the other carbapenems against methicillin-resistant S. aureus TUH1. Against this pathogen, the ED50 of vancomycin was 3.13 mg/kg. S-4661 was slightly less effective than meropenem-cilastatin but more effective than the other tested agents against E. coli C-11. S-4661 had almost the same effectiveness as that of the other test carbapenems against P. aeruginosa E7. Against ceftazidime-resistant P. aeruginosa TUH302, S-4661 was the most effective compound among the test drugs. The ED50 of meropenem against this pathogen was greater than 100 mg/kg.

TABLE 2.

Protective effects of S-4661 and other agents in murine systemic infections

| Strain | Challenge dose (CFU/mouse) | Drug(s) | ED50 (mg/kg) | 95% Confidence limit | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus Smith | 1.1 × 106 | S-4661 | 0.066 | 0.038–0.17 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 0.050 | 0.031–0.14 | 0.016 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 0.41 | 0.24–0.94 | 0.063 | ||

| Ceftazidime | 14.7 | 7.30–47.9 | 8 | ||

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus TUH1 | 5.5 × 107 | S-4661 | 19.2 | 11.9–31.3 | 4 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 34.5 | 18.2–88.0 | 16 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 48.4 | 28.0–132 | 16 | ||

| Vancomycin | 3.10 | 2.01–4.45 | 1 | ||

| E. coli C-11 | 9.0 × 105 | S-4661 | 1.42 | 0.65–4.48 | 0.032 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 2.41 | 1.29–7.04 | 0.063 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 0.62 | 0.32–20.3 | 0.016 | ||

| Ceftazidime | 1.69 | 0.86–7.15 | 2 | ||

| P. aeruginosa | |||||

| E7 | 2.5 × 104 | S-4661 | 10.0 | 0.71–37.7 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 7.13 | 1.31–15.5 | 2 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 7.11 | 3.32–12.1 | 0.5 | ||

| IPM2 | 5.3 × 105 | S-4661 | 6.24 | 3.41–11.2 | 8 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 2.42 | 1.45–4.32 | 16 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 38.9 | 25.2–58.3 | 32 | ||

| Ceftazidime | >100 | NCb | 32 | ||

| TUH302 | 3.0 × 104 | S-4661 | 31.2 | 15.9–114.4 | 2 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 32.4 | 17.9–91.1 | 8 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | >100 | NC | 4 | ||

| Ceftazidime | >100 | NC | 64 | ||

| S. pneumoniae TUH39a | 1.9 × 106 | S-4661 | 0.23 | 0.16–0.3 | 0.008 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 0.24 | 0.17–0.32 | 0.008 | ||

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 0.45 | 0.22–0.88 | 0.008 | ||

| Cefotaxime | 4.85 | 3.71–7.13 | 0.125 |

Pulmonary infection.

NC, not calculated.

The therapeutic effects of S-4661 in pulmonary infections induced by penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae TUH39 (Table 2) and penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae TUH741 (Table 3) were compared with those of imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem-cilastatin, and cefotaxime. The ED50 of S-4661 was 0.23 mg/kg against S. pneumoniae TUH39, the same as that of imipenem-cilastatin; S-4661 was more active against this organism than meropenem-cilastatin and cefotaxime. S-4661 was also active against penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae TUH741. The antibacterial activity of S-4661 at 10 mg/kg was significantly higher than that of the control group (P < 0.05) but was not higher than that of the other tested agents. The reduction in the number of microorganisms was more marked following treatment with S-4661 than after treatment with cefotaxime.

TABLE 3.

In vivo effects of S-4661 and other agents against respiratory tract infections in mice caused by S. pneumoniae TUH741a

| Drug(s)b | MIC (μg/ml) | Log CFU/g of lung (mean ± SD)c |

|---|---|---|

| None (control) | 7.17 ± 0.45 | |

| S-4661 | 0.25 | 4.07 ± 1.30d |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 0.125 | 4.39 ± 1.08d |

| Meropenem-cilastatin | 0.25 | 4.21 ± 0.49d |

| Cefotaxime | 0.5 | 5.62 ± 0.93 |

The inoculum was 3.0 × 105 CFU per mouse.

Each drug was administered at 10 mg/kg.

n = 5.

P < 0.05 compared with the value for the control group. The statistical difference was analyzed by the Tukey multiple-comparison test.

Serum antibiotic levels.

The levels of S-4661 and reference compounds in plasma after subcutaneous administration of a single dose of 20 mg/kg are summarized in Table 4. The peak level of S-4661 was higher than that of imipenem but similar to that of meropenem (S-4661, 14.6 μg/ml; imipenem, 12.0 μg/ml; meropenem, 14.0 μg/ml). The half-life of S-4661 was 17.7 min, compared with 18.5 min for imipenem and 10.2 min for meropenem. A combination of S-4661 and cilastatin prolonged the half-life but did not change the peak level in plasma. Therefore, the area under the concentration-time curve for S-4661 combined with cilastatin was 1.4 times higher than the value for S-4661 alone. Similar differences were found for imipenem versus imipenem-cilastatin and for meropenem versus meropenem-cilastatin.

TABLE 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of S-4661 and reference drugs in micea

| Drug |

Cmaxb (μg/ml)

|

t1/2c (min)

|

AUC0–∞d (μg · h/ml)

|

Ratio [CS+/CS−]

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS− | CS+ | CS− | CS+ | CS− | CS+ | Cmax | AUC0–∞ | |

| S-4661 | 14.6 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 23.4 | 9.08 | 12.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Imipenem | 12.0 | 14.4 | 18.5 | 23.3 | 6.99 | 10.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Meropenem | 14.0 | 19.7 | 10.2 | 24.1 | 5.73 | 13.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

The parameters were measured for the drugs both in combination with cilastatin (CS+) and without cilastatin (CS−).

Cmax, maximum concentration of the drug in serum.

t1/2, half-life.

AUC0–∞, area under the concentration-time curve from 0 h to infinity.

DISCUSSION

S-4661 is a new 1β-methylcarbapenem, with a sulfamoyl-aminomethyl-pyrrolidinylthio group in the side chain at position 3. The major finding of the present study was that this new carbapenem has a well-balanced wide-spectrum antibacterial activity against gram-positive and -negative bacteria. In other words, S-4661 showed greater activity than meropenem did against gram-positive cocci and greater activity than imipenem did against gram-negative rods. Also, the activity of S-4661 against P. aeruginosa, including imipenem-resistant strains, was two to four times higher than that of meropenem and imipenem. Compared with cephalosporins, S-4661 and the other carbapenems were more potent against all groups of staphylococci and streptococci. Cefpirome, an injectable cephalosporin with an expanded spectrum, is influenced by overexpression of chromosomally mediated enzymes which significantly elevate MICs for Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Serratia, and Pseudomonas spp. (1). In comparison with cefpirome, S-4661 was more active against these strains. The present study shows that with the introduction of the methyl group in the side chain at position 1, S-4661, like meropenem, becomes more active against gram-negative pathogens, in contrast with imipenem. Also, S-4661 has the same side chain as meropenem and biapenem at position 1. Against Enterobacteriaceae, especially the most frequently encountered clinical isolates, the activity of S-4661 was similar to that of meropenem but greater than that of imipenem. The tested carbapenems contain basic substituents (positively charged) at position 2 of the carbapenem. While S-4661 also has a basic group in the side chain at position 2, it is less basic than other carbapenems. The chemical structure of S-4661 suggests that the new side chain at position 2 also enhances the activity of the compound against drug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Meropenem is stable against dehydropeptidase I from guinea pigs, pigs, dogs, and humans but is unstable against that from mice, rats, and rabbits (1). Accordingly, in the present in vivo study, cilastatin, an inhibitor of dehydropeptidase I, was administered simultaneously with meropenem in mice; the simultaneous administration of cilastatin and meropenem is not required in humans. Since S-4661 is stable against a variety of dehydropeptidases I (6), we did not administer cilastatin in our mouse models. The in vivo efficacy of S-4661 was roughly the same as or better than that of reference drugs. However, the present data indicate that the efficacy of S-4661 is less than its in vitro activity; this is in contrast to data for imipenem-cilastatin and meropenem-cilastatin. Experiments examining the pharmacokinetics of the tested drugs in mice indicate that a combination of S-4661 and cilastatin improves the concentration of S-4661 in plasma like a combination of meropenem or imipenem and cilastatin improves the concentration of meropenem or imipenem in plasma. This result indicates that in further studies examining in vivo activities of S-4661, cilastatin may be administered simultaneously.

In conclusion, our results indicate that S-4661 is a promising new carbapenem for the treatment of infections caused by gram-positive and -negative bacteria, including penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae and imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from Shionogi & Co.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edwards, J. R. 1995. Meropenem: a microbiological overview. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Iso Y, Irie T, Nishino Y, Motokawa K, Nishitani Y. A novel 1β-methylcarbapenem antibiotic, S-4661: synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 2-(5-substituted pyrrolidin-3-ylthio)-1β-methlycarbapenems. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1996;49:199–209. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Japanese Society for Chemotherapy. Method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of fastidious bacteria and anaerobic bacteria by microdilution method. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1993;41:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Japanese Society for Chemotherapy. Method for the determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of aerobic bacteria by microbrothdilution method. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1990;38:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahan J S, Kahan F M, Geogelman R, Currie S A, Jacson M, Stapley E O, Miller A K, Hendlin D, Mochales S, Hernandez S, Woodruff H B, Birnbaum J. Thienamycin, a new beta-lactam antibiotic. I. Discovery, taxonomy, isolation, and physical properties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1979;32:1–12. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura Y, Murakami K, Onoue H, Shimada J, Kuwahara S. Program and abstracts of the 34th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. S-4661, a new carbapenem: III. Pharmacokinetics in laboratory animals, abstr. F37; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura, Y., M. Nakano, and T. Yoshida. 1987. Microbiological assay methods for 6315-S (flomoxef) concentrations in body fluid. Chemotherapy 35(Suppl. 1):129–136.

- 8.Miller L C, Tainter M L. Estimation of the ED50 and its error by means of logarithmic probit graph paper. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1944;57:261–264. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standards M7-A2. Method for dilution antibacterial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 2nd ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada J, Kawahara Y. Overview of a new carbapenem, panipenem/betamipron. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1994;20:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunagawa M, Matsumura H, Inoue T, Fukasawa M, Kato M. A novel carbapenem antibiotic, SM-7338: structure-activity relationships. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1990;43:519–532. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tateda K, Takashima K, Miyazaki H, Matsumoto T, Hatori T, Yamaguchi K. Noncompromised penicillin-resistant pneumococcal pneumonia CBA/J mouse model and comparative efficacies of antibiotics in this model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1520–1525. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji M, Ishii Y, Ohno A, Miyazaki S, Yamaguchi K. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of S-1090, a new oral cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2544–2551. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubukata K, Hikida M, Yoshida M, Nishiki K, Furukawa Y, Tashiro K, Konno M, Mitsuhashi S. In vitro activity of LJC10,627, a new carbapenem antibiotic with high stability to dehydropeptidase I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:994–1000. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]