Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae NEM865 was isolated from the culture of a stool sample from a patient previously treated with ceftazidime (CAZ). Analysis of this strain by the disk diffusion test revealed synergies between amoxicillin-clavulanate (AMX-CA) and CAZ, AMX-CA and cefotaxime (CTX), AMX-CA and aztreonam (ATM), and more surprisingly, AMX-CA and moxalactam (MOX). Clavulanic acid (CA) decreased the MICs of CAZ, CTX, and MOX, which suggested that NEM865 produced a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase. Genetic, restriction endonuclease, and Southern blot analyses revealed that the resistance phenotype was due to the presence in NEM865 of a 13.5-kb mobilizable plasmid, designated pNEC865, harboring a Tn3-like element. Sequence analysis revealed that the blaT gene of pNEC865 differed from blaTEM-1 by three mutations leading to the following amino acid substitutions: Glu104→Lys, Met182→Thr, and Gly238→Ser (Ambler numbering). The association of these three mutations has thus far never been described, and the blaT gene carried by pNEC865 was therefore designated blaTEM-52. The enzymatic parameters of TEM-52 and TEM-3 were found to be very similar except for those for MOX, for which the affinity of TEM-52 (Ki, 0.16 μM) was 10-fold higher than that of TEM-3 (Ki, 1.9 μM). Allelic replacement analysis revealed that the combination of Lys104, Thr182, and Ser238 was responsible for the increase in the MICs of MOX for the TEM-52 producers.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important pathogen that is usually susceptible to extended-spectrum cephalosporins. However, strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) were described in the early 1980s, and, since that time, there has been an increase in the incidence of ceftazidime (CAZ)-resistant Klebsiella strains responsible for nosocomial outbreaks (8, 16, 27). In most cases, ESBLs are plasmid-encoded enzymes providing resistance to oxyiminocephalosporins (CAZ, cefotaxime [CTX], ceftriaxone, cefpirome, and cefepime [FEP]) and to aztreonam (ATM) (16, 24). Cephamycins (cefoxitin [FOX] and cefotetan [CTT]), moxalactam (MOX), and carbapenems are stable toward most ESBLs, and strains producing such enzymes remained susceptible to these molecules (7, 24). The molecular basis of the extended spectrum often involves point mutations within plasmid-mediated β-lactamase genes resulting in either single or multiple amino acid substitutions in the corresponding enzymes (7, 16, 24). We describe here a novel TEM-type ESBL able to hydrolyze MOX. The enzyme is produced by a clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae.

(Part of this work was presented at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 28 September to 1 October 1997 [24a].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. K. pneumoniae NEM865 was isolated from the culture of a stool sample from a 2-year-old girl previously treated with CAZ for 2 weeks. K. pneumoniae NEM533, a nalidixic acid-resistant mutant of K. pneumoniae 5214-K (28; this study) and Escherichia coli K802N (33) resistant to nalidixic acid were used as recipients in mating experiments. E. coli TG1 (11) and plasmid pBGS18 (31) were used in the cloning experiments as the host strain and vector, respectively. Plasmids pBR322 (32) and pCFF04 (30) were used as templates for the amplification of blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-3, respectively. Bacteria were grown in Mueller-Hinton (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-La-Coquette, France) media at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant charactersa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae | ||

| NEM865 | Tic Caz Mox Cm Sm Gm Su Tmp Tc | Clinical isolate |

| NEM533 | Nal | Spontaneous mutant of K. pneumoniae 5214-K (28) and this work |

| NEM835 | Nal Tic Caz Mox | Conjugation NEM865 × NEM533 |

| E. coli | ||

| K802N | Nal; hsdR+hsdM+gal met supE | 33 |

| TG1 | F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacz)M15proA+B−/supE Δ(hsdM-mcrB)5(rk−mk− McrB−)thi Δ(lac-proAB) | 11 |

| NEM837 | Nal Tic Caz Mox | Conjugation NEM865 × K802N |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNEC865 | Tic Caz Mox; Mob (13.5 kb) | This work |

| pBGS18 | Km (cloning vector) | 31 |

| pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52 | Km Tic Caz Mox; recombinant derivative of pBGS18 carrying a 1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment amplified from pNEC865 | This work |

| pBGS18ΩblaTEM-3 | Km Tic Caz; recombinant derivative of pBGS18 carrying a 1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment amplified from pCFF04 | This work |

| pBGS18ΩblaTEM-1 | Km Tic; recombinant derivative of pBGS18 carrying a 1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment amplified from pBR322 | This work |

| pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52-H | Km Tic; recombinant derivative of pBGS18 carrying the 660-bp EcoRI-PstI fragment of pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52 and the 340-bp PstI fragment of pBGS18ΩblaTEM-1 | This work |

Resistance to antibiotics is denoted as follows: Tic, ticarcillin; Caz, ceftazidime; Mox, moxalactam; Cm, chloramphenicol; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Sm, streptomycin; Nal, nalidix acid; Su, sulfamide; Tmp, trimethoprim; and Tc, tetracycline. Mob, mobilizable.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Disk diffusion tests were performed, and the results were interpreted according to the guidelines of the Comité Français de l’Antibiogramme (1). The MICs were determined on Mueller-Hinton agar by a dilution method with an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot. The following antimicrobial agents were kindly provided by the indicated manufacturers: amoxicillin (AMX), ticarcillin, and clavulanic acid (CA), Smith Kline Beecham; cefalothin and CAZ, Glaxo Group Research Ltd., Greenford, England; cefotetan, ICI Pharmaceuticals Inc.; FOX and imipenem, Merck-Sharp & Dohme-Chibret); MOX, Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind.; sulbactam (SUL), Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.; CTX, Hoechst-Roussel Pharmaceuticals Inc., Somerville, N.J.; tazobactam (TZ), Taiho Laboratories, Tokushima, Japan; and ATM and benzylpenicillin, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Princeton, N.J.

Genetic techniques.

Mating on filters was performed as described previously (33). Transfer frequencies were expressed as the number of transconjugants per donor CFU after the mating period. The antibiotic concentrations for the selection of transconjugants were 20 μg/ml for CAZ and 50 μg/ml for nalidixic acid.

Isoelectric focusing of β-lactamases.

Analytical isoelectric focusing was done with CAZ-resistant E. coli transconjugants and transformants. Supernatants of sonicates were subjected to isoelectric focusing for 2 h by using a mini IEF cell 111 (Bio-Rad) and a gradient made up of two-thirds of polyampholytes with a pH range of 4 to 6 and one-third with a pH range of 3 to 10 (Serva). Extracts from TEM-1, TEM-2, and TEM-3-producing strains were used as standards for pIs of 5.4, 5.6, and 6.3, respectively. β-Lactamases were revealed by overlaying the gel with nitrocefin (1 mg/ml) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7).

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Isolation of plasmid DNA, transformation, restriction endonuclease digestion, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and other standard recombinant techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (29). DNA-DNA hybridization was performed as follows. DNA was transferred onto nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously (29). Purified plasmid ColE1::Tn3 DNA was used as a probe and was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham, les Ulis, France) by nick translation. Prehybridization and hybridization were carried out for 4 and 18 h, respectively, at 65°C in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 sodium citrate), 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.05% nonfat dry milk, followed by two washings in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 30 min and two washings in 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 45 min.

PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing.

The pairs of primers C1 (5′-gggaattcTCGGGGAAATGTGCGCGGAAC-3′) and C2 (5′-gggatccGAGTAAACTTGGTCTGACAG-3′), which delineate blaTEM-1 of pBR322 (32), were used in the PCR experiments, which were carried out as described previously (25). These primers were designed to add EcoRI and BamHI sites (bases in lowercase letters) at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the blaT gene, respectively. The amplicons were purified, digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and cloned into pBGS18 digested with the same enzymes, and recombinant DNAs were introduced by transformation into E. coli TG1. The entire nucleotide sequences of both strands of three cloned amplicons obtained from independent PCRs were determined by using the dideoxy chain termination method of Sanger with the DYE ABI-PRISM sequencing kit on a Genetic ABI-PRISM 310 Sequencer Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystem Division, Roissy, France).

β-Lactamase preparation.

Crude enzyme extracts were prepared for kinetics assays as described previously (22). The kinetic parameters were determined spectrophotometrically in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) at 30°C with a model 550 double-beam spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). One unit of β-lactamase was defined as the amount of enzyme able to hydrolyze 1.0 μmol of cephaloridine per min. Wavelengths of 233 nm for benzylpenicillin, 235 nm for ampicillin, 260 nm for cephaloridine and CAZ, and 267 nm for CTX were used. Vmax and Km values were calculated by computerized linear regression analysis of Woolf-Augustinsson-Hofstee plots (velocity versus velocity divided by substrate concentration). For the determination of the Ki values of MOX and the concentrations of clavulanic acid required to inhibit 50% of the β-lactamase activity (IC50), the inhibitor was preincubated with the enzyme for 5 min at 30°C before the addition of the substrate. The Ki values of MOX were deduced from Dixon plots. The protein concentrations were measured by the technique of Bradford (6).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of blaTEM-52 has been assigned EMBL accession number Y13612.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Properties of K. pneumoniae NEM865.

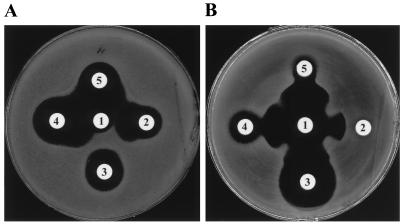

NEM865 was isolated in March 1996 at the Hospital Necker-Enfants Malades from the culture of a stool sample from a 2-year-old girl originating from Athens, Greece. The review of the records revealed that the patient was previously treated with CAZ for 2 weeks. A stool swab collected from this patient on admission as part of a surveillance study for multiply resistant enterobacteria grew K. pneumoniae NEM865. Analysis of this strain by the conventional disk diffusion antibiotic susceptibility test suggested that β-lactam resistance was due to the presence of an ESBL combined with another mechanism of resistance. No zones of inhibition were detected for penicillins, tested alone or in combination with a β-lactamase inhibitor, or for FOX or CAZ. Synergies were observed between AMX-CA and cephalosporins such as CAZ, CTX, and FEP, between AMX-CA and ATM, and more surprisingly, between AMX-CA and MOX (Fig. 1A presents some of these results). NEM865 was also resistant to chloramphenicol, gentamicin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline (data not shown). The MICs of β-lactams for K. pneumoniae NEM865 indicated that this strain was resistant to all antibiotics tested except imipenem (Table 2). In order to evaluate the effects of β-lactamase inhibitors on MOX activity, CA, SUL, and TZ were combined with MOX at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml. Eightfold decreases in the MICs of MOX were obtained with the three β-lactamase inhibitors (Table 2). These results suggested that K. pneumoniae NEM865 produces of a novel type of ESBL which is able to hydrolyze MOX.

FIG. 1.

Detection of the production of an ESBL by the double-disk synergy test. The bacterial strains were wild-type strain K. pneumoniae NEM865 (A) and E. coli TG1 containing pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52 (B). Disks: 1, AMX-CA (AMX at 20 μg and CA at 10 μg); 2, CTX (30 μg); 3, MOX (40 μg); 4, ATM (30 μg); 5, CAZ (30 μg). Note the potentiation of cephalosporins, ATM, and MOX by CA.

TABLE 2.

MICs for the strains tested

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMX | AMX + CA | TIC | TIC + CA | CF | FOX | CTX | CAZ | MOX | MOX + CA | MOX + SUL | MOX + TZ | CTT | ATM | IMP | |

| K. pneumoniae | |||||||||||||||

| NEM865 | >1,024 | >1,024 | >1,024 | 512 | 512 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 32 | 0.5 |

| NEM533 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | <0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.06 | <0.5 |

| NEM835 (NEM835/pNEC865) | >1,024 | 16 | >1,024 | 16 | 128 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | 16 | <0.5 |

| E. coli | |||||||||||||||

| K802N | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | <0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | <0.5 |

| NEM837 (K802N/pNEC865) | >1,024 | 16 | >1,024 | 16 | 128 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | 8 | <0.5 |

| TG1/pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52 | >1,024 | 32 | >1,024 | 32 | 256 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | 8 | <0.5 |

| TG1/pBGS18ΩblaTEM-3 | >1,024 | 16 | >1,024 | 16 | 64 | 4 | 16 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 8 | <0.5 |

| TG1/pBGS18ΩblaTEM-1 | >1,024 | 8 | >1,024 | 8 | 32 | 4 | <0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 | <0.5 |

| TG1/pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52H | >1,024 | 128 | >1,024 | 128 | 256 | 4 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | <0.5 |

| TG1/pBGS18 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | <0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | <0.5 |

TIC, ticarcillin; CF, cephalothin; IMP, imipenem. The other abbreviations are defined in the text. CA, SUL, and TZ were each used at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Genetic support of the ESBL β-lactamase gene in K. pneumoniae NEM865.

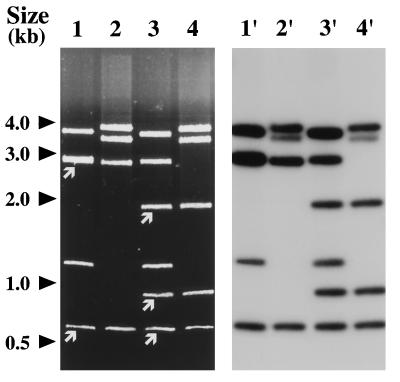

K. pneumoniae NEM865 was mated with K. pneumoniae NEM533 and E. coli K802N. Transconjugants of NEM533 and K802N resistant to nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) and CAZ (10 μg/ml) were obtained at frequencies of 3 × 10−6 and 5 × 10−5, respectively. Resistance to chloramphenicol, gentamicin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline were not cotransferred with CAZ resistance. The plasmid contents of NEM865 and randomly selected NEM533 and K802N transconjugants (six of each) were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis following digestion with HindIII (data not shown). A large plasmid (>50 kb) and a small plasmid (13.5 kb) were detected in the wild-type clinical isolate NEM865, whereas only the small replicon, designated pNEC865, was present in all the transconjugants studied (data not shown). A transconjugant of K. pneumoniae NEM533 and E. coli K802N were selected for further studies and were designated NEM835 and NEM837, respectively (Table 1). Neither of the selected K. pneumoniae NEM835 or E. coli NEM837 transconjugants was able to retransfer (<10−8 per donor) CAZ resistance to appropriate K. pneumoniae or E. coli recipients (data not shown). These results suggest that the gene conferring CAZ resistance is carried by pNEC865 and that this plasmid could be transferred by mobilization in its original host, NEM865. Plasmid pNEC865 and ColE1::Tn3 (12) were compared by restriction endonuclease and Southern blot analyses (Fig. 2). Tn3 contains one PstI (658 bp) and two PstI-BamHI (1919 and 920 bp) internal DNA fragments (13). DNA fragments of similar sizes and carrying sequences homologous to ColE1::Tn3 were detected in pNEC865 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, partial sequencing (200 bp) of the 920-bp BamHI-PstI fragment of pNEC865 revealed that the segment sequenced was almost identical to the corresponding region of the Tn3 tnpR gene (data not shown). These data indicate that pNEC865 harbors a Tn3-like element. Plasmid pNEC865 has an approximate size of 13.5 kb and carries only the β-lactamase resistance gene. These features are unusual for a plasmid encoding an ESBL, because such plasmids are usually large (≥80 kb) and carry multiple antibiotic resistance genes (17).

FIG. 2.

Restriction and Southern analyses of pNEC865. Lanes 1 and 1′ and lanes 2 and 2′, PstI digestion of ColE1::Tn3 and pNEC865, respectively; lanes 3 and 3′ and lanes 4 and 4′, BamHI-PstI digestion of ColE1::Tn3 and pNEC865, respectively. Plasmid ColE1::Tn3 was used as a probe. DNA fragments internal to Tn3 are indicated by white arrows.

By using the disk diffusion test, the synergies between AMC-CA and CTX, AMX-CA and CAZ, AMX-CA and ATM, and AMX-CA and MOX observed with the wild-type strain NEM865 were also observed with NEM835 and NEM837 (data not shown). In comparison with NEM865, K. pneumoniae NEM835 was resistant to CTX and CAZ, with fourfold decreases in the MICs of these antibiotics. The MICs of cephamycins (FOX and CTT) and MOX were also lower, confirming that high-level resistance to cephamycins in wild-type strain NEM865 was due to the production of an ESBL combined with another mechanism of β-lactam resistance. Other enzymes (MIR-1, CMY-1, FOX-1, and LAT-1, etc.) that degrade α-methoxycephalosporins and MOX have been described previously (7). However, the β-lactam resistance conferred by these enzymes is usually not reversed by inhibitor combinations, a feature enabling the distinction between such enzymes and TEM-derived ESBLs. Therefore, the reduced susceptibility to cephamycins in the wild-type strain NEM865 was probably related to the decreased permeability of the strain for β-lactams, as described previously (21, 23). The MICs of MOX for K. pneumoniae NEM835 and E. coli NEM837 transconjugants fell into the susceptible range but remained higher than those for the recipient strains (4 versus 0.25 μg/ml). The combination of MOX with a β-lactamase inhibitor (CA, SUL, or TZ) restored the susceptibility to this antibiotic (Table 2). Interestingly, the production of this novel ESBL by K. pneumoniae or E. coli transconjugants also increased the MIC of CTT but not that of FOX. Isoelectric focusing revealed the production of a β-lactamase with a pI of 6.0 by the wild-type strain NEM865 and the transconjugants K. pneumoniae NEM835 and E. coli NEM837 (data not shown).

Cloning and sequencing of the blaT gene of pNEC865.

A 1-kb DNA fragment amplified from pNEC865 and carrying the blaT gene was cloned into pBGS18, and the resulting plasmid was introduced into E. coli TG1. The β-lactam resistance phenotypes of the E. coli transformants were similar to those of the E. coli transconjugants (Fig. 1B and Table 2). Sequence analysis revealed that the blaT gene of pNEC865 differed from blaTEM-1 by three mutations, leading to three amino acid substitutions: Lys for Glu at position 104, Thr for Met at position 182, and Ser for Gly at position 238 (Table 3). Since the combination of these three substitutions has not been described previously, the ESBL produced by pNEC865 was designated TEM-52. TEM-52 is closely related to TEM-3, one of the first ESBLs to be described (30), and TEM-15 (20). The same critical substitutions involved in the extension of the β-lactamase spectrum were present in these enzymes at positions 104 and 238, but TEM-52 differed from TEM-3 by a Glu-to-Lys change and a Thr-to-Met change at positions 39 and 182, respectively, and from TEM-15 by a Thr-to-Met change at position 182 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid substitutions of TEM-type variants at critical positions

| β-Lactamase | pI | Amino acid at the following positiona:

|

Reference or source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | 69 | 104 | 164 | 182 | 238 | |||

| TEM-1 | 5.4 | Gln | Met | Glu | Arg | Met | Gly | 32 |

| TEM-2 | 5.6 | Lys | Met | Glu | Arg | Met | Gly | 3 |

| TEM-3 | 6.3 | Lys | Met | Lys | Arg | Met | Ser | 30 |

| TEM-15 | 6.0 | Gln | Met | Lys | Arg | Met | Ser | 20 |

| TEM-20 | 5.4 | Gln | Met | Glu | Arg | Thr | Ser | 4 |

| TEM-32 | 5.4 | Gln | Ile | Glu | Arg | Thr | Gly | 10, 14 |

| TEM-43 | 6.1 | Gln | Met | Lys | His | Thr | Gly | 35 |

| TEM-52 | 6.0 | Gln | Met | Lys | Arg | Thr | Ser | This work |

| TEM-52H | —b | Gln | Met | Lys | Arg | Thr | Gly | This work |

Enzyme assays and analysis of the amino acid substitutions in TEM-52.

In order to compare the kinetic constants of TEM-52 with those of TEM-1 and TEM-3, blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-3 genes were amplified, cloned into pBGS18, and introduced into E. coli TG1 as described above (Table 1). The cloned blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-3 genes were sequenced to verify that no misincorporation of nucleotides occurred during the PCRs. Comparison of the MICs of cephamycins and MOX for TG1 strains producing TEM-3 or TEM-52 confirmed that this novel ESBL confers resistance to CTT and MOX but not to FOX (Table 2). The Km value and the relative rates of hydrolysis (Vrel) of TEM-52 were compared to those of TEM-3, which revealed that the biochemical characteristics of these two β-lactamases were similar (Table 4). It is worth noting that the Km values of these enzymes were typical of those of ESBLs belonging to the Ser238 family (26). In addition, the IC50 of CA for TEM-52 (14 nM) and TEM-3 (10 nM) were also nearly identical. Therefore, the mutation Met182→Thr does not result in Km or IC50 modifications. The specific activity of TEM-52 was 3.5-fold higher that of TEM-3 when ampicillin was used as the substrate (data not shown). These differences in specific activity might be responsible for the higher MICs of β-lactams for strain TG1 producing TEM-52 compared to those for strain TG1 producing TEM-3 (Table 2). Because MOX hydrolysis was not measurable in vitro under our conditions, Ki values were determined to compare the respective affinities of TEM-52 and TEM-3 for this antibiotic. The affinity of TEM-52 for MOX was 10-fold higher than that of TEM-3 (Table 3). This increased affinity might explain the differences in the MICs of MOX for TG1 strains producing TEM-52 or TEM-3 (Table 2).

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of TEM-52, TEM-3, TEM-52H, and TEM-1

| Substrate | TEM-52

|

TEM-3

|

TEM-52H

|

TEM-1

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | Ki (μM)a | Relative Vmax (%) | Km (μM) | Ki (μM) | Relative Vmax (%) | Km (μM) | Relative Vmax (%) | Km (μM) | Relative Vmax (%) | |

| Benzylpenicillin | 5.3 | —b | 100 | 3.8 | — | 100 | 29 | 100 | 26 | 100 |

| Ampicillin | 4.1 | — | 66 | 8.2 | — | 126 | 40 | 113 | 40 | 122 |

| Cephaloridine | 13 | — | 130 | 19 | — | 120 | 532 | 95 | 244 | 25 |

| CAZ | 239 | — | 50 | 350 | — | 65 | 982 | 0.2 | — | — |

| CTX | 30 | — | 229 | 35 | — | 252 | 1,170 | 2.3 | — | — |

| MOX | — | 0.16 | — | — | 1.9 | — | — | — | — | — |

Ki constants were measured with cephaloridine used as the substrate.

—, not determined.

The mutation Met182→Thr has been described previously in three different variants of TEM-1 (32): TEM-20, TEM-32 (IRT-3), and TEM-43 (4, 10, 14, 35). Amino acid residues Thr182 and Ser238 are found with TEM-20, residues Ile69 and Thr182 are found with TEM-32, and residues Lys104, His164, and Thr182 are found with TEM-43 (Table 3). None of these enzymes were shown to confer the resistance phenotype observed with TEM-52. We have shown that TEM-52 differed from TEM-3 and TEM-15 by two substitutions and one substitution, respectively (Table 3). The mutation at position 39, which also differentiates TEM-1 from TEM-2, has been associated only with minor changes in the substrate profile (5, 7, 9). Therefore, it is likely that the amino acid change responsible for the difference between the enzymatic profiles of TEM-52 and TEM-3 is the Met182→Thr replacement.

The association of Lys104, Thr182, and Ser238 in TEM-52 is responsible for MOX hydrolysis.

To investigate the role of the three mutations (Lys104, Thr182, and Ser238) in TEM-52 involved with MOX hydrolysis, a blaTEM-52–blaTEM-1 hybrid gene was constructed by replacing the 340-bp PstI fragment of pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52 with that of pBGS18ΩblaTEM-1 (Table 1). The resulting plasmid, pBGS18ΩblaTEM-52H, encoded a hybrid TEM β-lactamase, designated TEM-52H, which differed from TEM-52 by a Ser238→Gly change (Table 3). This enzyme, like other TEM variants containing only the Lys104 substitution, was unable to confer resistance to 7-oxyiminocephalosporins (Table 2) (5). The kinetic constants of this hybrid protein were similar to those of TEM-18, an ESBL containing the Lys104 substitution (Table 4) (26). These results suggest that the combination of Thr182 with Lys104 does not account for the extended spectrum of TEM-52. On the other hand, MOX hydrolysis by TEM-3 or TEM-15, which contains Lys104 and Ser238, or by TEM-20, which contains Thr182 and Ser238, has never been studied. Taken together, these results suggest that the combination of Lys104, Thr182, and Ser238 is responsible for the extended spectrum of TEM-52 and is required for MOX hydrolysis.

Kinetic and molecular modeling analyses of ESBLs have provided the following explanations for the influences of certain mutations on the substrate profiles of these enzymes. The residue at position 238 is situated at the end of the β-3 sheet, and mutations at this residue, such as Gly238→Ser, might enlarge the active site to give enzymes with higher affinities for 7-oxyiminocephalosporins (15, 34). The Glu104→Lys change, which has been observed for many ESBLs, may perturb the seryl-aspartyl-asparagyl loop and its interaction with the substrate (15). Molecular modeling studies have led to the suggestion that the presence of a threonine at position 182 probably strengthens a hydrogen bond which stabilizes the active site and, consequently, increases the catalytic activity of the enzyme (10, 18). A cooperative effect of these three mutations in TEM-52 might account for the ability of this enzyme to hydrolyze MOX.

In conclusion, these results highlight the remarkable adaptability of K. pneumoniae to selective antibiotic pressure. Until this report, cephamycins and MOX were considered to be stable to ESBLs and cephamycins remained an option for the treatment of infections due to organisms producing such enzymes (16, 19, 27). Further work is required to determine whether the level of resistance to MOX observed in vitro has clinical significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J.-L. Beretti for help in determining pI values.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and by the Université Paris V.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acar J, Bergogne-Bérézin E, Chardon H, Courvalin P, Dabernat H, Drugeon H, Dubreuil L, Duval J, Flandrois J P, Goldstein F, Meyran M, Morel C, Philippon A, Sirot J, Thabault A. Comité de l’antibiogramme de la société française de microbiologie. Communiqué 1994. Pathol Biol. 1994;42:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler R P, Coulson A F, Frère J M, Ghuysen J M, Jaurin B, Joris B, Levesque R, Tiraby G, Waley S G. A standard numbering scheme for the class A beta-lactamase. Biochem J. 1991;276:269–272. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambler R P, Scott G K. Partial amino acid sequence of penicillinase coded by Escherichia coli plasmid R6K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3732–3736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arlet G, Goussard S, Courvalin P, Philippon A. Nucleotide sequences of TEM-20, TEM-21, TEM-22, and TEM-29. 1997. Unpublished data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazquez J, Morosini M I, Negri M C, Gonzales-Leiza M, Baquero F. Single amino acid replacements at positions altered in naturally occurring extended-spectrum TEM beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:145–149. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing a principal of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter J L. Klebsiella pulmonary infections: occurrence at one medical center and review. J Infect Dis. 1990;12:672–682. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaibi E B, Farzaneh S, Péduzzi J, Barthélémy M, Labia R. An extra ionic bond suggested by molecular modeling of TEM-2 might induce a slight discrepancy between catalytic properties of TEM-1 and TEM-2 β-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:121–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farzaneh S, Chaibi E B, Peduzzi J, Barthelemy M, Labia R, Blazquez J, Baquero F. Implication of Ile-69 and Thr-182 residues in kinetic characteristics of IRT-3 (TEM-32) β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2434–2436. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson T J. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein F W, Labigne-Roussel A, Gerbaud G, Carlier C, Collatz E, Courvalin P. Transferable plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter. Plasmid. 1983;10:138–147. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(83)90066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heffron F, McCarthy B J, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E. DNA sequence analysis of the transposon Tn3: three genes and three sites involved in transposition of Tn3. Cell. 1979;18:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henquell C, Chanal C, Sirot D, Labia R, Sirot J. Molecular characterization of nine different types of mutants among 107 inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases from clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:427–430. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huletsky A, Knox J R, Lesvesque R C. Role of Ser-238 and Lys-240 in the hydrolysis of third generation cephalosporins by SHV-type-β-lactamases probed by site-directed mutagenesis and three dimensional modelling. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3690–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. More extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1697–1704. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacoby G A, Sutton L. Properties of plasmids responsible for extended-spectrum β-lactamase production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:164–169. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox J R. Extended-spectrum and inhibitor-resistant TEM-type β-lactamases: mutation, specificity, and three-dimensional structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2593–2601. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mabilat C, Courvalin P. Development of “oligotyping” for characterization and molecular epidemiology of TEM β-lactamases in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2210–2216. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Martinez L, Hernandez-Allès S, Alberti S, Tomas J, Benedi V J, Jacoby G A. In vivo selection of porin-deficient mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae with increased resistance to cefoxitin and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:342–348. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mugnier P, Dubrous P, Casin I, Arlet G, Collatz E. A TEM-derived extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2488–2493. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pangon B, Bizet C, Pichon F, Philippon A, Regnier B, Bure A, Gutman L. In vivo selection of a cephamycin resistant porin mutant of a CTX-1 β-lactamase producing strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:1005–1006. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philippon A, Labia R, Jacoby G A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1131–1136. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Poyart C, Mugnier P, Quesnes G, Berche P, Trieu-Cuot P. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. A novel TEM-type extended spectrum beta-lactamase from K. pneumoniae hydrolyzing moxalactam, abstr. C-185; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poyart C, Pierre C, Quesne G, Pron B, Berche P, Trieu-Cuot P. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in the genus Streptococcus: characterization of a vanB transferable determinant in Streptococcus bovis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:24–29. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raquet X, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Fonzé E, Goussard S, Courvalin P, Frère J M. TEM β-lactamase mutants hydrolysing third-generation cephalosporins. J Mol Biol. 1994;244:625–639. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice L B, Willey S H, Papanicolau A, Medeiros A, Eliopoulos G M, Moellering R C, Jacoby G A. Outbreak of ceftazidime resistance caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamases at a Massachusetts chronic-care facility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2193–2199. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riottot M-M, Fournier J-M, Jouin H. Direct evidence for the involvement of capsular polysaccharide in the immunoprotective activity of Klebsiella pneumoniae ribosomal preparations. Infect Immun. 1981;31:71–77. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.1.71-77.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sirot D, Sirot J, Labia R, Morand A, Courvalin P, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Perroux R, Cluzel R. Transferable resistance to third generation cephalosporins in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae: identification of CTX-1, a novel β-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20:323–324. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spratt B G, Hedge P I, Heesen S, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8, and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutcliffe J G. Nucleotide sequence of the ampicillin resistance gene of Escherichia coli plasmid pBR322. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3732–3736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trieu-Cuot P, Courvalin P. Transposition behavior of IS15 and its progenitor IS15-Δ: are cointegrates exclusive end-products? Plasmid. 1985;14:80–89. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(85)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venkatachalam K V, Huang W, LaRocco M, Palzkill T. Characterization of TEM-1 β-lactamase mutants from positions 238 to 241 with increased catalytic efficiency for ceftazidime. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23444–23450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Bhachech N, Bradford P A, Jett B D, Sahm D F, Bush K. Program and abstracts of the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates producing TEM-10 and TEM-43 β-lactamases from St. Louis, abstr. C25; p. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]