HIGHLIGHTS

-

•

This study analyzed public arguments on a sugar-sweetened beverage tax before and after implementation.

-

•

News articles were coded for type, authors, frame, themes, and evidence.

-

•

Pro-tax themes included health, fund benefits, equity, and unethical soda industry.

-

•

Anti-tax themes included economic effects, government overreach, and ineffectiveness.

-

•

Anti-tax arguments tried to leverage local issues against sugar-sweetened beverage tax policy.

Keywords: Media, sugar-sweetened beverage, fiscal policy, news, communications, food

Abstract

The objective of this paper was to analyze the contents of opinion and news articles related to the city of Boulder's sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax campaigns in Boulder's only local newspaper. We searched for articles in The Daily Camera related to the sugar-sweetened beverage tax, published from January 2016 to December 2018. We conducted a content analysis, categorizing 152 relevant articles by type, authors, and frames (pro, anti, neutral) on the basis of the preponderance of arguments, themes, and use of evidence. The majority of articles were opinion (n=92) versus news (n=60). Most articles were pro-frame (n=78) versus anti-frame (n=37) and neutral frame (n=37). Pro-frame articles were more likely to cite evidence in support of arguments or the professional credentials/experience of the authors. The most frequent pro-frame themes were health, benefits of the revenues, equity, and unethical tactics of the industry. The most frequent anti-frame themes were economic consequences, claims that the measure was confusing, government overreach, and purported ineffectiveness of taxes. The leveraging of local issues by the beverage industry was observed. Themes identified in the news regarding Boulder's successful sugar-sweetened beverage tax may appear in future sugar-sweetened beverage policy campaigns and should be anticipated.

INTRODUCTION

Evaluations of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) excise taxes in several U.S. cities, Mexico, and other countries have shown that SSB taxes meaningfully reduce SSB consumption and purchasing while generating funds for community health and equity programs.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 The nation's first SSB excise tax was adopted by voters in Berkeley, California in 2014. In 2016, Boulder, Colorado along with Oakland, San Francisco and Albany, California also enacted SSB taxes through ballot initiatives.11 Boulder's SSB tax measure was launched in the Spring of 2016 by the volunteer organization, Healthy Boulder Kids, and supported by the nonprofit organization Healthier Colorado. The 2016 opposition, “No on 2H: Stop the Beverage and Grocery Tax,” was funded by the American Beverage Association (ABA).

The pro-tax campaign had 3 periods: 2016 ballot measure; 2017 efforts to implement the tax as intended; and 2018 Taxpayer's Bill of Rights (TABOR)–related ballot measure, specific to Colorado's context.12 The SSB tax was passed by 54% of Boulder voters in November 2016 and went into effect on July 1, 2017, levying a 2-cent-per-fluid-ounce excise tax on distributors of SSBs containing ≥5 grams of caloric sweetener per 12 fluid ounces.13 The policy also established the city's Health Equity Fund, which provides grants to community organizations and agencies promoting health equity. All revenues, minus costs of tax collection and fund administration, have been awarded through this fund, totaling $21 million since implementation.14 The 2017 phase involved city council decisions around implementation issues such as tax exemptions and establishing the Health Equity Advisory Committee. The TABOR ballot measure (which asked voters to approve having any tax revenues beyond the measure's projected estimate remain within the Health Equity Fund instead of being returned to SSB distributors) was passed by 65% of voters in November 2018.

With the ABA funding the opposition in a presidential election year, the 2016 campaign was the most expensive in city history and frequently covered in the local newspaper. The framing and themes of pro and anti arguments can provide insights for SSB campaigns elsewhere and for public health policy campaigns more generally. Previous research has examined the media coverage and framing of SSB tax policy in Oakland, Berkeley, and San Francisco in California and public testimony to the Philadelphia City Council.15, 16, 17 Themes included, for instance, the health risks of SSBs and revenue benefits for community programs in pro-framed media as well as ideological and economic (e.g., regressivity, grocery tax) arguments and the leveraging of local issues by anti-framed media.

To date, there have been no published studies of media coverage or framing of Boulder's tax measure. Boulder's 2018 TABOR vote, which was required by Colorado tax law because tax revenues exceeded projected estimates, provides a unique opportunity to examine community perspectives on an SSB tax 1 year into implementation. Another unique feature of Boulder is that it has only 1 daily newspaper—the Daily Camera—which heavily covered the SSB tax.

Therefore, we sought to analyze the framing and themes of all SSB tax–related articles from January 2016 through December 2018 in the Daily Camera. Earned media (i.e., articles either deemed newsworthy by the newspaper staff or submitted freely by citizens as opinion pieces) can provide insight into community points of view. These perspectives can inform public health communications on SSB taxes, which have continued to be important in public discourse after implementation.

METHODS

We used the publicly accessible database, NewsBank, to search for relevant articles from the Daily Camera, which has a circulation of 20,000 for 108,250 residents (2020 Census). We used search terms such as sugar-sweetened beverage, soda tax, and 2H (Appendix Table 1, available online, for a complete list). Inclusion criteria were a primary focus on the SSB tax and publication date between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2018. Of 224 retrieved articles, 152 were relevant and included in the sample (Appendix Table 2, available online, for article list). We categorized these into news (authored by staff writer) or opinion (editorial, OpEd, letter to the editor) on the basis of the article's official designation. Articles were coded for type (news or opinion), author and self- or news staff–identified affiliation, policy frame (pro, anti, or neutral based on the preponderance of pro- or anti-tax arguments presented and quoting of speakers in support and/or opposition), use of evidence (describing outside sources to bolster their argument), and themes.

Table 1 contains abbreviated theme descriptions (Appendix Table 3, available online, for complete descriptions). We developed a codebook of themes through an inductive rather than a priori approach on the basis of an initial reading of all articles and an iterative process of coding, comparing, and discussing codes among the team. All themes in an article were coded and counted. For example, if a news article presented quotes from a supporter about the health equity benefits from SSB tax revenues as well as an opponent arguing that the tax was government overreach, both themes would be coded—one as funding benefits and the other as government overreach. All articles were coded by the first author, and 10% of the articles were independently coded by the last author, with intercoder reliability at 89% agreement for coded themes and 100% for article frame. Microsoft Excel was used for coding. Because human subjects were not involved, IRB approval was not required.

Table 1.

Themes and Their Abbreviated Descriptions in the Study Codebook

| Themes | Description |

|---|---|

| Pro-tax themes | |

| Unethical actions of Big Soda | Unethical tactics of the ABA and soda industry, targeted marketing, comparisons to the tobacco industry |

| Health | Child health, health risks of SSB consumption |

| Healthcare costs | Costs borne by society from negative health effects of SSB consumption |

| Equity | Health disparities, health equity, social justice |

| Funding benefits | Benefits of the tax revenue (e.g., through the Health Equity Fund) |

| Efficacy | Examples of SSB tax efficacy elsewhere or of other excise taxes (e.g., tobacco) |

| Clarity | Rebuttal to the argument that the measure is confusing or difficult to implement |

| Not regressive | Rebuttal to the argument that the SSB tax is regressive |

| Not a grocery tax | Rebuttal to the argument that the tax amounts to a grocery tax |

| Community | Benefits bring together or are the right message for the Boulder community |

| Anti-tax themes | |

| Unnecessary | Boulder is already a healthy place; everyone already knows that SSBs are unhealthy |

| Government overreach | Government overreach or slippery slope |

| Responsibility | Personal choice/responsibility, parental authority |

| SSB tax does not work | SSB taxes do not work; the tax is not doing what it is supposed to |

| Economic | Hurt local businesses; personal cost burden |

| Regressive | The tax will disproportionately burden poor families |

| Confusing or burdensome to implement | Businesses are uncertain about how it will affect them; implementation challenges |

| Kombucha | The tax hurts kombucha businesses, which make lower or natural sugar drinks |

| Grocery tax | The tax amounts to a grocery tax and will raise the price of all groceries |

| Neutral themes | |

| Politics | What the 2 campaigns are doing or how those actions interact with the city government and courts |

| Campaign financing | How campaigns were financed |

| Colorado TABOR | Legality of the measure within Colorado tax law |

ABA, American Beverage Association; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; TABOR, taxpayer's bill of rights.

RESULTS

The 152 articles were written by 91 unique authors. Table 2 shows the distribution of articles by type and frame. Most articles (61%) were opinion (n=92: letter to the editor=69, OpEd=15, editorial=8), and 39% (n=60) were news. Among opinion articles, the majority (n=59, 64%) were categorized as pro-frame, presenting mostly arguments in favor of the tax, with the remainder of anti-frame articles presenting mostly arguments against the tax (n=30, 33%). Among news articles, 57% were neutral frame (n=34), presenting a similar distribution of arguments for and against the tax or neither, whereas 32% were pro-frame (n=19). Twenty-two (28%) of the total 78 pro-frame articles cited research to support their statements or arguments versus 3 (8%) of the 37 anti-frame articles. In 48 (62%) of the pro-frame articles, authors mentioned their own credentials or experience as an authority, including parents, nutritionists, healthcare providers, nonprofit leaders, program clients, and educators, versus in 6 (16%) of the anti-framed articles.

Table 2.

News Articles by Type (News or Opinion) and Policy Frame

| Article type |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy framea | Opinion, n (%) | News, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

| Pro- | 59 (64) | 19 (32) | 78 (51) |

| Anti- | 30 (33) | 7 (12) | 37 (24) |

| Neutral | 3 (3) | 34 (57) | 37 (24) |

| Total | 92 | 60 | 152 |

Determined by the preponderance of pro or anti-tax arguments or neutral themes presented and quoting of speakers in support and/or opposition. Neutral frame was coded if there was a similar distribution of arguments for and against the tax or only neutral themes.

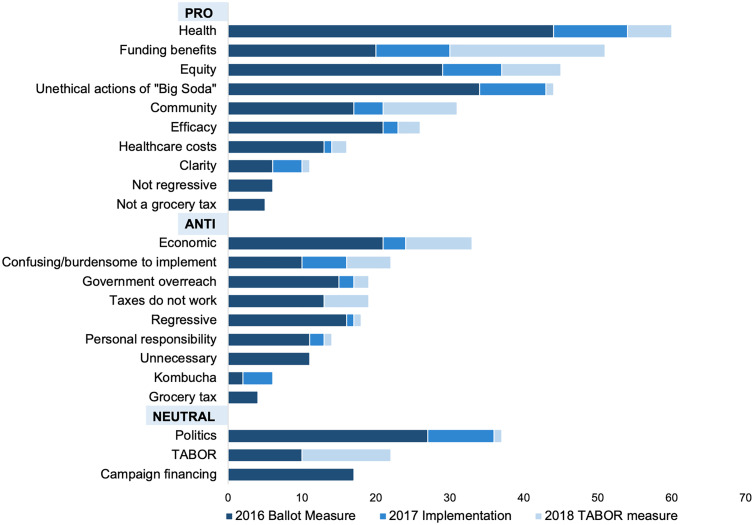

Figure 1 shows themes by campaign period and frame. Pro-frame arguments focused largely on health (e.g., child health, dental health, health consequences of SSBs) and benefits of the Healthy Equity Fund, particularly in 2018, when organizations and individuals benefiting from the fund revenues submitted opinion pieces and were interviewed in news articles (Appendix Table 4, available online, for citations of articles associated with the following quotes): “I have seen the direct benefits the tax has provided through direct patient services, program development and community building.” (1)

Figure 1.

Counts of themes identified in Daily Camera articles on the SSB tax by campaign period and frame.

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; TABOR, Taxpayer's Bill of Rights.

Other pro-frame arguments referred to unethical tactics of the soda industry and their targeted marketing to children and communities of color—“When I read that the conglomerate soda beverage companies… are pouring huge amounts of money into Boulder to persuade us, I took offense” (2)—and equity (health disparities, racial and social justice)—“Much like gun violence, these chronic diseases are strongly associated not just with racial disparity, but also with chronic poverty and barriers to education.” (3)

Articles arguing for effectiveness of soda taxes typically cited studies from Mexico and Berkeley. Some pro-framed articles presented arguments responding to anti-tax themes and misinformation, such as rebutting the arguments that the tax was confusing, regressive, and a tax on groceries.

Anti-frame arguments focused primarily on economic consequences and the common perception that Boulder already over-regulates local businesses—“…everyone who wanted a soda would just buy it outside the city, thus reducing the patronage and tax revenue from our local grocery and convenience stores” (4)—on government overreach and the slippery-slope argument that it would lead to more taxes—“What is next? A ban on ice cream at public swimming pools? A tax on cookies and pie, or salt, or meat?” (5)—on personal responsibility—“My wife and I managed to raise our children and manage their sugar intake without a tax.... Do we need to address uninformed and lazy thinking by more regulations and taxes?” (6)—and on the idea that taxes do not work and are unnecessary, particularly in a healthy community as Boulder is perceived to be—“Taxes don't fight obesity; healthy lifestyle choices do.” (7)

The only health-oriented anti argument came from a local kombucha founder who argued that their lower-sugar drinks, as part of Boulder's celebrated natural and organic products industry, were providing an alternative to sodas and alcohol and should not be taxed.

Neutral articles during the 2016 ballot measure covered campaign financing, TABOR, both campaigns’ tactics, and SSB policy nationally. Conflict and confusion between the pro- and anti-tax campaigns around polling, signatures, ballots, ABA lawsuits, and financing were highly covered. In 2018, the ABA did not fund an opposition, nor did they fund individuals to oppose the measure. Local news, in trying to present balance without an anti spokesperson, often filled this void with vaguely attributed references to opposition arguments: “Restaurant and store owners have spoken out against the added expense… Still others contend the higher-than-expected revenue shows the tax's stated goal—of discouraging consumption—has not been met.” (8)

DISCUSSION

This analysis of SSB tax coverage in Boulder's only newspaper showed that a majority of articles were opinion and pro-frame, containing a preponderance of pro-tax arguments. Pro-frame authors were more likely than anti-frame to cite personal or professional expertise and to use evidence. Pro-framed articles appealed to concepts of community and social justice, perceived unethical actions of the ABA and soda industry, and support from community organizations and individuals who benefit from SSB tax funding. The anti-framed articles showed repetition of simple messages; appeals to ideological arguments, individual preferences, and local business; and leveraged concurrent local concerns such as pride in Boulder's healthy food industry, which produced some taxable products, and perceived high regulation of local business.

Many themes overlapped with those found in analyses of other SSB campaigns, including exploitation of local concerns by the ABA.15, 16, 17, 18 The 2018 vote to keep tax revenue for use by the Health Equity Fund passed by a larger margin than the original 2016 measure. Pro arguments in the 2018 campaign focused largely on community and funding benefits, which align with findings and recommendations from Berkeley and Philadelphia.8,17 The focus on community and funding benefits may have played a role in the high public support for the 2018 measure because public support has been observed to be higher when an SSB tax is framed as funding health and public programs rather than as a nutrition intervention or means to fill general funding gaps.19,20 Overall, there were more pro-framed articles than anti-framed, but there was expressed skepticism from news staff about motivations behind the tax and the inclusion of affected communities, which may indicate the centering of public health advocates rather than affected community members in the campaign’ outward-facing aspects.

Limitations

This is the first study to analyze news framing of Boulder's successful SSB tax measures. Owing to Colorado's unique TABOR law, a novel contribution was the analysis of public arguments surrounding an SSB tax after implementation, when it was again the subject of a local measure. Limitations include assessing only earned media and from 1 newspaper, albeit Boulder's only daily. Official and social media campaign messages were not assessed. Finally, generalizability to other jurisdictions is uncertain and hinges on local contexts such as lawsuits and opposition campaigns.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings identified themes in Boulder that may arise in future SSB-tax campaigns. For successful policy adoption, proponents must prepare arguments, anticipate anti arguments, and prepare rebuttals. Recommendations for doing so have been developed.5,21,22 Anticipating how local issues will arise is important; Boulder-specific issues were the belief that Boulder is already a healthy place, concerns about taxing local kombucha, and the perception that businesses are over-regulated. The analysis of the 2018 campaign after implementation can help communities and advocates to understand ongoing SSB tax perceptions, which may be important in countering potential repeal campaigns. The media focus on funding benefits, together with the subsequent high support for the 2018 measure, suggests the importance of ensuring that messages from affected communities and those who will benefit from tax–revenue–supported equity programs are heard.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views or policy of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

JF was supported by NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K01DK113068 and U.S. Department of Agriculture/The National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch project 1016627.

KD was an unpaid volunteer for Healthy Boulder Kids, a nonprofit that advocated for the Boulder sugary drink tax during the time period of the campaigns from 2016 to 2018. No other disclosures were reported.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Kristen Daly: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Meredith Fort: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jennifer Falbe: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.focus.2023.100068.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption 3 years after the Berkeley, California, sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):637–639. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberto CA, Lawman HG, LeVasseur MT, et al. Association of a beverage tax on sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages with changes in beverage prices and sales at chain retailers in a large urban setting. JAMA. 2019;321(18):1799–1810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell LM, Leider J. Impact of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax two-year post-tax implementation in Seattle, Washington, United States. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(4):574–588. doi: 10.1057/s41271-021-00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colchero MA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin BM, Ng SW. In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(3):564–571. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falbe J. The ethics of excise taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages. Physiol Behav. 2020;225 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidaña-Pérez D, Braverman-Bronstein A, Zepeda-Tello R, et al. Equitability of individual and population interventions to reduce obesity: a modeling study in Mexico. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreyeva T, Marple K, Marinello S, Moore TE, Powell LM. Outcomes following taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falbe J, Grummon AH, Rojas N, Ryan-Ibarra S, Silver LD, Madsen KA. Implementation of the first U.S. sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Berkeley, CA, 2015–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1429–1437. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger J, Magee K, Hennings T, Schoof J, Madsen KA. How sugar-sweetened beverage tax revenues are being used in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones-Smith JC, Knox MA, Coe NB, et al. Sweetened beverage taxes: economic benefits and costs according to household income. Food Policy. 2022;110 doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falbe J, Madsen K. Growing momentum for sugar-sweetened beverage campaigns and policies: costs and considerations. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):835–838. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TABOR. Colorado General Assembly, The Legislative Council Staff. https://leg.colorado.gov/agencies/legislative-council-staff/tabor. Updated August 2022. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- 13.Health Equity Advisory Committee (HEAC). City of Boulder Colorado. https://bouldercolorado.gov/health-equity-advisory-committee-heac. Updated 2022. Accessed December 31, 2022.

- 14.Health equity fund. City of Boulder. https://bouldercolorado.gov/services/health-equity-fund. Updated 2022. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- 15.Asada Y, Pipito AA, Chriqui JF, Taher S, Powell LM. Oakland's sugar-sweetened beverage tax: honoring the “spirit” of the ordinance toward equitable implementation. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):35–41. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somji A, Nixon L, Mejia P, Azizi M, Arbatman L, Dorfman L. Berkeley Media Studies Group; Berkeley, CA: 2016. Soda Tax Debates in Berkeley and San Francisco: an Analysis of Social Media, Campaign Materials and News Coverage.https://food.berkeley.edu/research-database/soda-tax-debates-in-berkeley-and-san-francisco-an-analysis-of-social-media-campaign-materials-and-news-coverage/ Published 2016. Accessed November 6, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elstein JG, Lowery CM, Sangoi P, et al. Analysis of public testimony about Philadelphia's sweetened beverage tax. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(3):e178–e187. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mejia P, Perez-Sanz S, Garcia K, Dorfman L. Berkeley Media Studies Group; Berkeley, CA: 2021. Communicating about the nutrition equity amendment act of 2021: an analysis of news, social media, and campaign materials.https://voicesforhealthykids.org/assets/resources/bmsg_nutrition_equity_amend_analysis_september2021.pdf Published November 15, 2021. Accessed November 6, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eykelenboom M, van Stralen MM, Olthof MR, et al. Political and public acceptability of a sugar-sweetened beverages tax: a mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0843-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chriqui JF, Sansone CN, Powell LM. The sweetened beverage tax in Cook County, Illinois: lessons from a failed effort. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1009–1016. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tax Equity Workgroup, Healthy Food America . Tax Equity Workgroup, Healthy Food America; Seattle, WA: 2020. Centering equity in sugary drink tax policy: elements of equitable tax policy design.https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/heatlhyfoodamerica/pages/439/attachments/original/1613144730/SSB_Tax_Equity_Policy_Report_FINAL.pdf?1613144730 Published December 2020. Accessed November 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tramutola L. 2021. The people vs big soda: strategies for winning soda tax elections. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.