HIGHLIGHTS

-

•

Behavior change techniques used in vaping prevention campaigns were analyzed.

-

•

Campaigns focused on the consequences of vaping to dissuade youth from vaping.

-

•

Few campaigns incorporated other promising techniques (e.g., youth identity) to prevent uptake.

-

•

Utilizing additional techniques in prevention campaigns is recommended.

Keywords: E-cigarettes, vaping, prevention campaigns, behavior change techniques, public health

Abstract

Introduction

Vaping among North American youth has surfaced as a concerning public health epidemic. Increasing evidence of harms associated with E-cigarette use, especially among the young, has prompted urgency in addressing vaping. Although a number of individual behavior change campaigns have arisen as a result, little is known about which behavior change techniques are being employed to influence youth vaping behavior. In this study, we aimed to code all North American vaping prevention campaigns using the behavior change technique taxonomy (Version 1) to determine which behavior change techniques are being used.

Methods

We identified the sample of campaigns through systematic searches using Google. After applying the exclusion criteria, the campaigns were reviewed and coded for behavior change techniques.

Results

In total, 46 unique vaping prevention campaigns were identified, including 2 federal (1 from Canada, 1 from the U.S.), 43 U.S. state–level, and 1 Canadian provincial–level campaign(s). The number of behavior change technique categories and behavior change techniques in a campaign ranged from 0 to 5 (mean=1.56) and 0 to 6 (mean=2.13), respectively. Of the 16 possible behavior change technique categories, 4 were utilized across the campaigns, which included 5. Natural consequences (89%), 6. Comparison of behavior (22%), 13. Identity (20%), and 3. Social support (11%).

Conclusions

Only a small number of behavior change techniques were used in North American vaping prevention campaigns, with a heavy and often sole reliance on communicating the health consequences of use. Incorporating other promising behavior change techniques into future campaigns is likely a productive way forward to tackling the complex and multifaceted issue of youth vaping.

INTRODUCTION

A combination of successful vape marketing, peer influence, and an assortment of enticing flavors has led to what is described as an epidemic among school-aged youth in North America.1 This epidemic is exhibited by 21.3% of adolescents aged between 15 and 17 years vaping within the past 30 days in 2019.2 In addition, of these adolescents, 40% reported using an E-cigarette daily or close to daily.3 Students around middle school age reported lower rates of vaping, with 5.4% of youth aged between 12 and 14 years using E-cigarettes.2 While slightly lower, the rates of E-cigarette use in the U.S. are similar to the use rates in Canada.4

There is increasing evidence of the risks of vaping, both independent of smoking and in combination with smoking.5 For example, vaping alone has been found to increase pulmonary inflammation similar to that of tobacco smoke,6 lead to nicotine addiction,7 harm brain development,8 and put youth at up to a fourfold risk for cigarette use.9,10 Dual use of both vaping and smoking has been found to significantly increase one's risk for heart and lung disease compared with vaping or smoking alone.11, 12, 13 Given that youth and young adults are disproportionately at risk for these harmful impacts of vaping,14 there is an urgency to intervene.

A key aspect of public health measures designed to prevent engagement in health risk behaviors is through the use of individual behavior change campaigns. Individual behavior change campaigns are campaigns developed with the goal of motivating individuals to make lifestyle changes that will benefit themselves or society.15 They can have a promising impact on health behaviors.16 For example, smoking prevention campaigns altered beliefs around smoking and associated smoking behaviors, resulting in increased cessation rates.17 Currently, the landscape of youth-focused vaping prevention interventions is in its infancy. Although many initiatives have their roots in traditional tobacco control, they have modified their approaches by incorporating new information (e.g., vaping harms) and modes of delivery (e.g., social media).18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Research has yet to catch up in terms of evaluating these campaigns.

Michie et al. (2015)’s behavior change technique taxonomy, Version 1 (BCTTv1), is a productive way to identify the behavior change techniques (BCTs) that underpin vaping prevention campaigns.23 The BCTTv1 contains 93 itemized health BCTs, which are clustered into 16 groupings.23 The BCTTv1 has been used to analyze the content of a variety of health-related interventions, including online smoking cessation interventions.24 The primary objective of this descriptive qualitative content analysis is to apply the BCTTv1 framework to analyze the content of existing vaping prevention campaigns across North America. The specific questions addressed in this study include (1) what kinds of prevention campaigns are in place to address E-cigarette use? and (2) which specific BCT categories are being used within these interventions?

METHODS

Study Sample

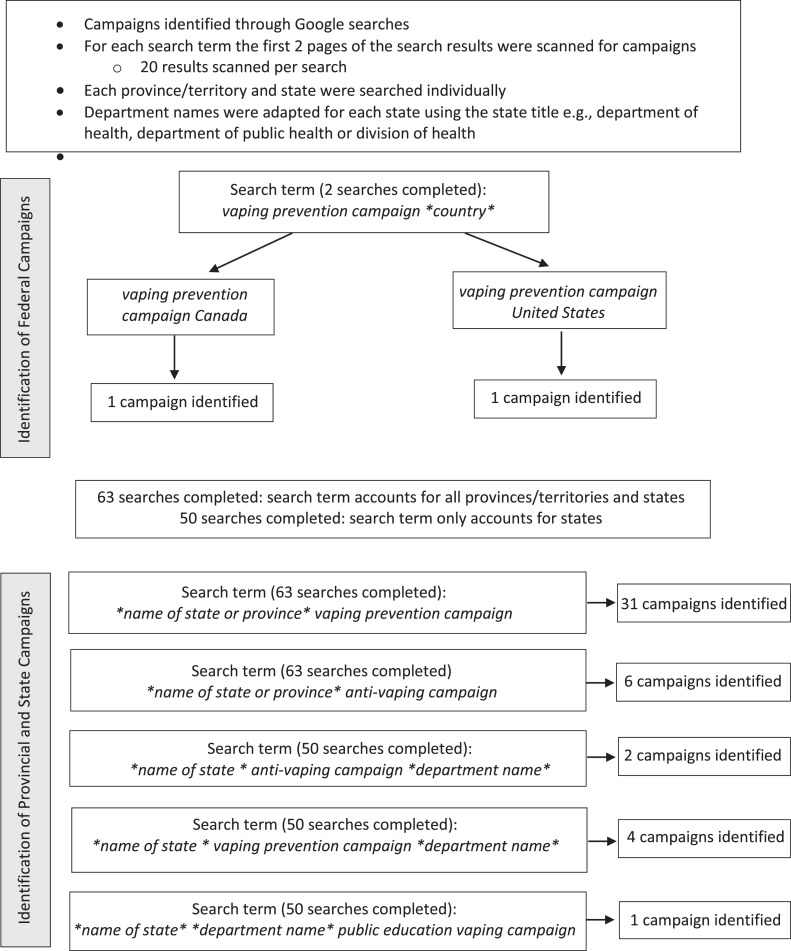

The sample for this study consisted of vaping prevention campaigns across North America. We found government-funded vaping prevention campaigns using individualized Google searches for both the U.S. and Canada (see Figure 1 for search strategy). We found provincial and state-level campaigns by individually searching each province/territory and state. The search included the phrases vaping prevention campaign, anti-vaping campaign, department of health anti-vaping campaign, and public education vaping campaign along with the corresponding name of the country or province/state. The exclusion criteria included campaigns that were not provincewide or statewide (e.g., targeted a specific population within a city/town or district), campaigns that only focused on smoking or lacked sufficient materials on vaping, and campaigns that could not be classified as a standard campaign (e.g., only had prevention toolkits, workshops). Campaigns designed by not-for-profit organizations could only be included if they were statewide and government funded.

Figure 1.

Campaign search strategy.

The first 2 pages of each search were scanned for campaign websites as well as news articles mentioning campaign names. Scanning beyond 2 pages was deemed unnecessary because results were not relevant to the state or province searched past the second page. We gathered and analyzed campaign materials from campaign websites (e.g., posters). We also analyzed social media pages included with a campaign (e.g., Instagram, Facebook). We gathered publicly available data and therefore did not require ethics approval.

Measures

We used the BCT taxonomy (Version 1) to identify the BCTs within the vaping prevention campaigns. All researchers involved were familiar with the BCT taxonomy, and the primary researcher conducting the coding (DR) had completed the online BCT training course as part of a previous study.24 All included campaign descriptions and links were uploaded onto a shared OneDrive file for coding according to the BCT taxonomy.

Data Analysis

We employed deductive content analysis to determine which BCTs were utilized in the vaping prevention campaigns. Deductive content analysis is the process of applying data to a pre-existing framework,25 such as the BCTv1. We analyzed the campaign media materials for the main themes underlying their core messages, which we then used for coding the BCTs. For example, we found that many campaigns spoke about the potentially negative impacts of vaping on the lungs, which we coded as negative health impacts, and we then linked to BCT 5.1 “health consequences.” All analyses were cross-referenced by the lead author (LS). We created a document that compiled the results and provided us with an audit trail of our decision making. Throughout the analysis, the research team was consulted to discuss the results and areas of ambiguity regarding the campaign content and the BCT taxonomy definitions.

RESULTS

Intervention Characteristics

In total, 46 unique vaping prevention campaigns were included in the final review (Table 1). Of these, 2 (4%) were at the federal level (1 from Canada; 1 from the U.S.), 43 (94%) were at the U.S. state level, and 1 (2%) was at the Canadian provincial level. Four (9%) campaigns did not list a known launch date, 1 (2%) was launched in 2015, 2 (4%) were launched in 2016, 7 (15%) were launched in 2018, 16 (35%) were launched in 2019, 13 (28%) were launched in 2020, and 3 (7%) were launched in 2021.

Table 1.

National, Provincial, and State-Level Campaigns

| Campaign (location), year launched | Delivery medium | Target audience | BCT category | BCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Real Cost campaign (U.S.), 2018 |

TV ads, online video ads, website, social media (Tumblr, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube), high school posters | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Consider the Consequences of Vaping (Canada), 2018 | Digital influencers, fact sheets, school presentations, social media (Snapchat, YouTube, Instagram) | Youth, parents, adults, teachers | 3. Social support 5. Health consequences |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| The New Look of Nicotine Addiction (NL Canada), 2020 | Social media (Facebook, Twitter), billboards, online | Youth, parents, teachers | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| We Get It (AL), 2016 |

Videos, social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube) | Youth | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

| Not Buying It (AK), 2019 | Mobile apps, social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube), Spotify, video ads, posters, website | Youth, young adults | 3. Social support 5. Health consequences |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Facts Over Flavor (AZ), 2019 | Social media (Snapchat, YouTube, Instagram), mobile app, website | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Unnamed (AR), unknown date | Videos on movie screens, TikTok videos, posters | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.5 Anticipated regret |

| Tell Your Story (CA), 2021 | Videos | Youth, young adults | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior |

5.1 Information about health consequences 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior |

| Wake Up (CA), 2015 | TV Ads, digital ads, outdoor advertising, mall kiosks, gas stations, online digital banner ads, website, Facebook, social media influencers | Youth, parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Flavors Hook Kids (CA), 2018 | TV, digital video, radio, outdoor advertising, social media (Facebook, YouTube) |

Youth, parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.5 Anticipated regret |

| Outbreak (CA), 2019 | TV ads, Internet ads, radio ads | Young adults, parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| TobaccoFreeCo (CO), 2018 | Videos, social media (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube) | Parents, coaches, teachers, counselors | 5. Health consequences 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.5 Anticipated regret 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| The Dirty Truth (DE), 2016 | Posters, videos, social media (Facebook, Instagram) |

Youth | 5. Health consequences 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| The Facts Now (FL), 2020 | TV ads, radio ads, digital channels, social media ads | Youth | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval 13.1 Identification of self as role model 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| 808NoVape (HI), 2018 | Videos, social media (Instagram, Twitter) | Youth | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| Escape the Vape (HI), 2020 | Videos, social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube) | Youth | 5. Health consequences 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| Clear the Air on Teen Vaping (ID), 2019 | Social media (Facebook, YouTube), Google search ads |

Parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences |

| When the Smoke Clears (IL), 2019 | Social media ads | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Vaping Versus Reality (IA), 2019 | Social media (SnapChat, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube), Hulu, videos, posters | Youth; parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Behind the Haze (IN), 2019 | Posters, videos, social media (Instagram, Facebook) |

Youth, young adults | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Vaping—Don't Get Sucked In (ME), 2020 | TV, Hulu, social media (Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat) | Youth, young adults | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| The New Look of Nicotine Addiction (MA), 2018 | Videos, YouTube | Parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Vapes and Cigarettes: Different Products. Same Dangers (MA), 2019 | Online, social media (Snapchat, Instagram), Spotify, posters, handouts | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Facts. No Filters (MA), 2021 | Social media (Instagram, Snapchat), TV, Google, various websites |

Youth | 3. Social support 5. Health consequences |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Unnamed (MN), 2021 | TikTok partnership with physician Dr. Rose Marie Leslie | Youth | 3. Social support 5. Health consequences. 6. Comparison of behavior |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

| Clear the Air (MS), 2019 | Videos | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Behind the Haze (NV), 2020 | Social media (Snapchat, YouTube, Instagram), online | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Let's Talk Vaping (NV), 2020 | Radio, TV, online, social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube) | Parents, adults | 3. Social support 5. Health consequences. 6. Comparison of behavior |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 5.1 Information about health consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

| Save Your Breath (NH), 2020 | Social media (TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube), Spotify |

Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.5 Anticipated regret 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| VapeFacts (NJ), 2020 | Website, posters in schools | Youth, parents, teachers, coaches, healthcare providers | N/A | N/A |

| Incorruptible U.S. (NJ), 2019 | School posters, billboards, images on trains and buses, videos, social media (Facebook, Instagram), website | Youth | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.5 Anticipated regret 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

| Vape (NM), 2019 | Documentary, posters, videos, Facebook | Youth, parents, teachers | 5. Health consequences 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| Unnamed (NY), 2019 | TV | Youth,p arents |

5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Behind the Haze (OK), 2020 | TV, radio, social media (Instagram, YouTube) | Youth,p arents |

5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Down and Dirty (OK), 2020 | TV, radio, social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube) | Youth, parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences |

| Smokefree Oregon (OR), 2020 | Social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube), digital ads, search engine ads, website, billboards | Adults, young adults, healthcare providers |

5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 6.3 Information about others’ approval 13.1 Identification of self as role model |

| Stay True to You (OR), 2019 | Website, digital ads, billboards, social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube) | Youth | 13. Identity | 13.1 Identification of self as role model |

| Rethink Tobacco (SD), unknown date | Social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube) | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| We Own Big Tobacco (TN), unknown date | Billboards, images on transit, online ads, social media, magazines, broadcast | Youth | N/A | N/A |

| VapesDown (TX), 2020 | Posters, handouts, TV ads, digital videos, social media (YouTube and TikTok) | Youth | 5. Health consequences 6. Comparison of behavior |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior |

| Say What! (TX), unknown date | Social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Snapchat, TikTok), posters, window clings, signage | Youth | N/A | N/A |

| See Through the Vape (UT), 2020 | Social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) | Youth | 5. Health consequences 13. Identity |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences 13.3 Incompatible beliefs |

| Unhyped VT (VT), 2019 | Social media (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube), digital videos | Youth, young adults | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Raze (WV), 2019 | Posters, social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube) | Youth | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| Tobacco is Changing (WI), 2019 | Website, social media, print materials, online videos, cinema | Parents | 5. Health consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences |

| Unnamed (WY), 2018 | Videos | Youth | 6. Comparison of behavior | 6.3 Information about others’ approval |

BCT, behavior change technique; N/A, not applicable.

The majority (85%) (n=39) of these interventions targeted youth. In addition, 35% (n=16) targeted parents, 11% (n=5) targeted educators, 46% (n=21) included adults in general, and 35% (n=16) included both youth and adults. The target age range for the campaigns varied and ranged from age 9 years through to adulthood. More than half of the campaigns (61%) (n=28) did not report the specific age or grade level of the target youth.

The campaigns utilized a variety of modalities for marketing, including social media (63%); online videos (43%); poster and print materials (e.g., billboards and community signs) (43%); TV ads (33%); online (non–social media) ads on websites (e.g., Google) (28%); their own websites (28%); radio ads (15%); handouts for parents, healthcare providers, and educators (7%); partnerships with digital influencers (7%); and mobile apps (4%). Of the campaigns that utilized social media, YouTube (34%), Instagram (34%), and Snapchat (28%) were the most frequently used platforms, followed by Facebook (24%), TikTok (17%), Spotify (17%), and Twitter (7%). The majority (74%) of campaigns used a combination of several modalities (e.g., social media, radio, and infographics).

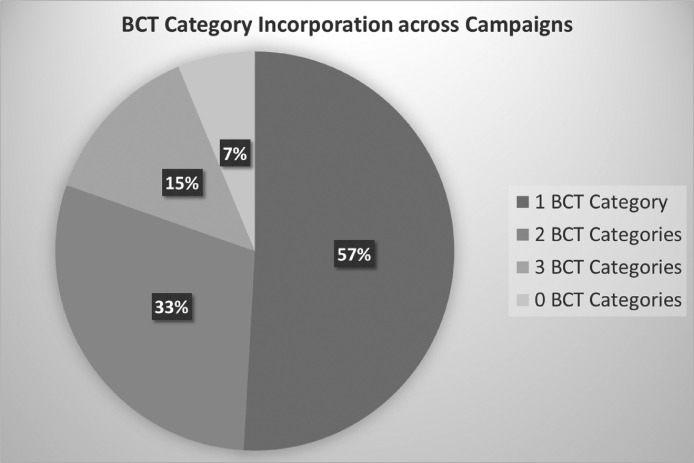

Breadth of Behavior Change Technique Application Within Campaigns

A range of 0–4 BCT categories (mean=1.31) and between 0 and 6 BCTs (mean=2.13) were used in the campaigns. It was most common for a campaign to utilize just 1 BCT category (n=26) (57%), followed by 2 (n=15) (33%), then 3 (n=7) (15%), and finally 0 (n=3) (7%). Campaigns that used multiple BCT categories contained a more varied focus. For example, 808NoVape, which utilized 3 BCT categories (5. Natural consequences, 6. Comparison of behavior, and 13. Identity) relayed messages around chemicals, nicotine, health, peer pressure/appearance, mental health, sports, and cost. Figure 2 visually displays the breadth of BCT category incorporation across the campaigns.

Figure 2.

Breadth of BCT category incorporation across campaigns.

BCT, behavior change technique.

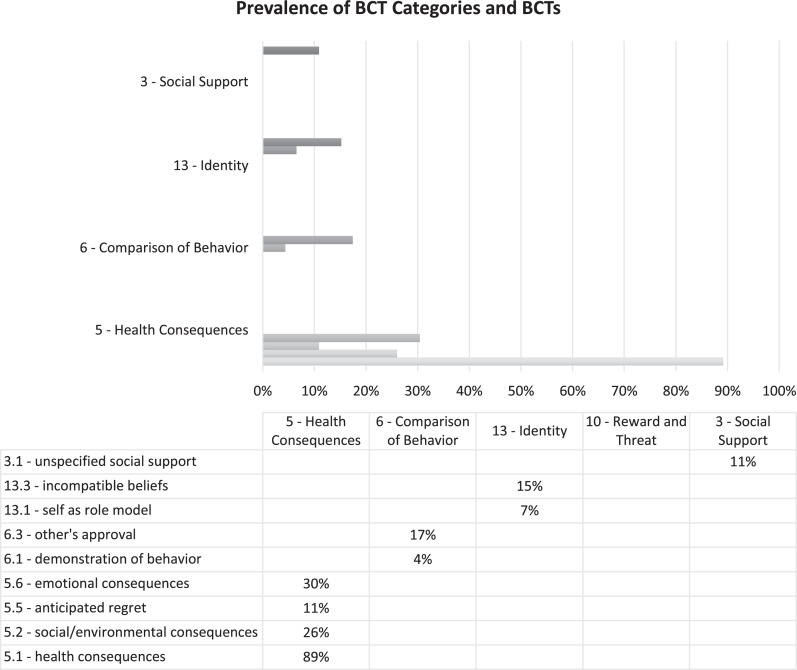

Campaign Behavior Change Technique Categories and Behavior Change Techniques

The 46 campaigns utilized 4 of the 16 possible BCT categories. In the order of popularity, these included 5. Natural consequences (89%) (n=41) (e.g., negative health effects), 6. Comparison of behavior (22%) (n=10) (e.g., information about others’ disapproval of vaping), 13. Identity (20%) (n=9) (e.g., identifying the self as a role model), and 3. Social support (11%) (n=5) (e.g., talking with other teens about vaping). Table 2 provides a summary of each BCT category and related BCTs applied in the campaigns. Figure 3 shows the distribution of how frequently each BCT category and related BCTs were endorsed across the interventions.

Table 2.

BCT and Message Content Across Campaigns

| BCT category (number of campaigns) | BCT (number of campaigns) | General themes identified in campaign content | Examples of BCT applications in campaign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. Natural consequences (41) | 5.1 Information about health consequences (41) 5.2 Information about social and environmental consequences (12) 5.5 Anticipated regret (5) 5.6 Information about emotional consequences (14) |

Addiction Chemicals Nicotine Negative health effects Brain development Mental health Flavors Secondhand vapor Missed opportunities |

The Real Cost – “Start with glycerin, add nicotine, add other unknown ingredients. If you vape, you could be inhaling toxic chemicals. It's a recipe for disaster.” |

|

| 6. Comparison of behavior (10) | 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior (2) 6.3 Information on others' approval (8) |

Peer pressure Appearance to peers Stories from others |

We Get It – “We get it; you vape. Look at you being edgy…” |

|

| 13. Identity (9) | 13.1 Identification of self as role model (3) 13.3 Incompatible beliefs (7) |

Future Sports/exercise Leadership |

Stay True to You – “*sister sees older sister vaping* ‘Stop following me. Hey, stop copying me. Mom! Don't copy me.’” |

|

| 3. Social support (5) | 3.1 Social support (unspecified) (5) | Talking/getting advice Supporting friends Supporting other teens |

Consider the Consequences of Vaping – “Talk with your teen about vaping.” |

|

BCT, behavior change technique.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of BCT categories and BCTs across campaigns.

BCT, behavior change technique.

Regarding specific BCTs within the 5 categories, a total of 10 were represented. Campaigns that used 5. Natural consequences all included 5.1 Information about health consequences, such as messages about the harmful chemicals found in E-cigarettes, addiction, and short- and long-term health consequences. Other BCTs used in this category included 5.3 Social and environmental consequences (e.g., secondhand vaper), 5.5 Anticipated regret (e.g., missed opportunities owing to addiction), and 5.6 Emotional consequences (e.g., increased anxiety). Campaigns endorsing 6. Comparison of Behavior delivered messages centered on 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior (e.g., stories from ex-vapers) and 6.3 Others' approval (e.g., acknowledging peer pressure to vape, disapproval by peers or important people in their lives).

In campaigns incorporating 13. Identity, some focused on 13.1 Identification of self as role model, encouraging youth to take an active role in preventing the uptake of vaping in their peer groups, school, and community. Other campaigns utilized 13.3 Incompatible beliefs, in which they drew on the disparity between youths' goals (e.g., athletic achievement) and the consequences of vaping (e.g., being out of breath), essentially positioning vaping as an obstacle to achieving their objectives. Finally, campaigns featuring 3. Social support provided 3.1 Social support (unspecified) and included things such as suggesting that parents talk to their teens about vaping or encouraging youth to be supportive of their friends.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the representation of BCTs in North American vaping prevention campaigns. We found that of 93 possible BCTs, only 9 that fell under 4 BCT categories were utilized. More specifically, of 16 BCT categories and 93 BCTs, these campaigns typically focused on 1–2 BCT categories and 1–2 respective BCTs only. This reveals the limited use of BCTs in current vaping prevention campaigns. Although we acknowledge that most campaigns are largely passive in nature, disabling the utilization of some of the BCT domains (e.g., 2. Feedback & monitoring, 8. Repetition & substitution), our findings indicate promise for expanding the breadth of BCT use in such campaigns given that a handful of campaigns utilized up to 6 different BCTs from up to 3 BCT categories. It is well established in the literature that youth uptake of E-cigarettes is complex, with multiple influencing factors lending to their decision to use them, including personal (e.g., to calm anxiety), relational (e.g., peer pressure), environmental (e.g., easy access), and product-related (e.g., flavors) factors.26 In this regard, it may be more beneficial to tap into multiple and diverse BCTs to help prevent youth uptake.

The majority of the campaigns in this study focused primarily on the BCT category 5. Natural consequences and, specifically, the health consequences BCT, especially in relation to physical health consequences of vaping (e.g., addiction). Although physical health is important and is viewed by youth as an important aspect of vaping prevention interventions,27 youth take up vaping for other reasons as well, including mental health, social identity, and curiosity,26 the latter of which may serve to override physical health as the most important reason to avoid vaping. A study on the perceptions of youth and parents on vaping prevention campaigns, including The Real Cost campaign, revealed that messages about the harmful chemicals in E-cigarettes were confusing for some youth, with parents voicing their concern that youth may not understand chemical names.28 Furthermore, youth evaluating The Real Cost campaign reported that addiction by itself is not a good enough reason not to use E-cigarettes.21 In this regard, caution is warranted in relying too heavily on health consequences in vaping prevention campaigns, and researchers are calling for more consideration of the complex and multifaceted factors that draw youth to vaping when developing prevention campaign messaging24,26,29, 30, 31

Evaluative evidence on youth vaping prevention efforts reveals an association between the BCT category 13. Identity and an increase in knowledge and risk perceptions as well as a decrease in intentions and perceived susceptibility to vape.18, 19, 20, 21,32, 33, 34 This is likely because this BCT category aims to present information and contexts with which individuals can identify. In a study whereby youth were asked to provide feedback on The Real Cost campaign materials, youth found relatable scenarios to be the most appealing.21 Despite this promising evidence, only 20% of the identified vaping prevention campaigns utilized this category in their messaging. To effectively prevent the uptake of vaping, prevention messaging must consider youth cultures, contexts, and identity (e.g., being social and fashionable, being part of hip hop and pop subcultures, and not caring about rules or physical health consequences).21,35

It is important to note that evaluative evidence in relation to the campaigns listed earlier is still in its infancy. Understanding which campaigns have which impact will strengthen our knowledge regarding the most useful BCTs for prevention of vaping among youth. In this regard, not only is there room for improving vaping prevention campaign messaging, but there is also an urgent need for evaluative research on these campaigns, both of which are an area ripe for future research.

Our evaluation of vaping prevention campaigns across North America revealed a disparity between the U.S.- and Canadian-driven campaigns. In Canada, the number of initiatives and the comprehensiveness of these initiatives were significantly limited when compared with those in the U.S. Not only does the U.S. have more initiatives, but a number of these campaigns address a more diverse range of BCTs (e.g., 5–6 vs 1–2 BCTs). These findings bring forward opportunities to expand Canadian vaping prevention efforts.

Most of the reviewed campaigns directly targeted youth, with only a few that targeted important people in the lives of youth (e.g., parents, caregivers, teachers, elders). It is important to note that the youth vaping epidemic is characterized not only by misperceptions of threat among youth but also by misperceptions among caregivers, limited research evidence on the topic of youth vaping, and a dearth of strategies to address youth E-cigarette use both in schools and in the larger communities.36 This indicates that families, school staff, and community groups are vital in addressing the youth vaping epidemic. Although research suggests that most parents are aware of the existence of E-cigarettes, many are unaware of high-nicotine salt devices, such as JUUL, and report having received minimal communication from their child's school about such devices.37 Despite their feelings of concern regarding adolescent E-cigarette use and support for stronger tobacco control policies, there remains a lack of understanding of these new products marketed toward youth.37, 38, 39 In this regard, campaigns would benefit from considering message dissemination to an audience that includes and extends beyond youth.

It is not surprising that campaigns relied heavily on social media platforms to disseminate their messages. Use of these platforms aligns with best practices in reaching youth with health promotion efforts.40 The primary use of YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat likely reflects current trends in use among youth.41 Moving forward, campaign developers would benefit from staying attuned to youth preferences for message dissemination on social media. It would be beneficial to inquire about the popular trends in social media use, changes in platform popularity, and youth preferences for receiving health promotion materials through different channels. For example, are particular channels not suited to health promotion content?

Limitations

There are a few limitations associated with this study. First, all included campaigns were restricted to U.S. and Canadian sources and initiatives given contextual similarities (e.g., usage rates, laws, and regulations). In this regard, we may have missed some useful sources located in other countries. Similarly, regarding the U.S. contexts, some states were excluded from this scan owing to the state only having local (e.g., city-wide or district-wide) rather than state-wide campaigns. Second, owing to the ambiguity of some of the campaign content, coding of the BCTs may at times have been subjective. Third, the initiatives included in this review are recent and have emerged in response to a novel public health issue. As a result, many have yet to be rigorously evaluated or published in peer-reviewed literature. Fourth, searching for campaigns on Google posed several challenges. Campaigns are not intended to be discovered by Google searching but rather to capture someone's attention when they are on social media or in their everyday lives with out-of-home advertising. As a result, campaign materials were only found if the organization included them on their website or social media account with a specific campaign name, thereby excluding pop-up ads used on social media; out-of-home advertisements designed for buses, billboards, or other modalities without a website; and campaigns without an explicit name announced. In this regard, we may have missed some campaigns because they did not show up in the search. Finally, although trained in applying the BCTTv1, the authors recognize that there may be subjective nuances in how some categories are applied.

CONCLUSIONS

This content analysis provides a comprehensive overview of North American youth vaping prevention campaigns and their associated BCTs. Although existing campaigns are limited in their use of BCTs to prevent youth vaping, this study laid the groundwork for using other BCTs in vaping prevention campaigns as well as areas for improvement. These findings provide critical information for moving health promotion efforts forward in a manner that resonates with youth.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Laura Struik: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Ramona H. Sharma: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Project administration. Danielle Rodberg: Methodology, Writing – original draft. Kyla Christianson: Writing – original draft. Shannon Lewis: Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding sources were not involved in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; or the preparation of the manuscript for publication.

This work was supported by a Canadian Cancer Society Emerging Scholar Award (Prevention) (Grant Number 707156) held by LS.

All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study and the analytic plan, interpreted the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. LS and RHS drafted the first version of the manuscript. DR and SL conducted the analyses and contributed to sections in the manuscript. RHS supported the analysis and wrote up the results section. KC conducted the literature review and supported the drafting of the final manuscript. LS developed and oversaw all aspects of the study, including its conceptualization, funding, and data collection. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venkata AN, Palagiri RDR, Vaithilingam S. Vaping epidemic in US teens: problem and solutions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021;27(2):88–94. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada. Less tobacco use for Canadian youth, but their reasons for vaping are concerning; Published 2022.https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/1519-less-tobacco-use-canadian-youth-their-reasons-vaping-are-concerning. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 3.Government of Canada. Summary of results for the Canadian Student Tobacco, alcohol and Drugs survey 2018–19; Published 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2018-2019-summary.html. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 4.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Results from the annual national youth tobacco survey; Published 2022. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/youth-and-tobacco/results-annual-national-youth-tobacco-survey#2022%20Findings. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 5.Abafalvi L, Pénzes M, Urbán R, et al. Perceived health effects of vaping among Hungarian adult e-cigarette-only and dual users: a cross-sectional internet survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):302. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6629-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tommasi S, Pabustan N, Li M, Chen Y, Siegmund KD, Besaratinia A. A novel role for vaping in mitochondrial gene dysregulation and inflammation fundamental to disease development. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22773. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling PM, Lee YO, Hong J, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Glantz SA. Social branding to decrease smoking among young adults in bars. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):751–760. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobore TO. On the potential harmful effects of E-Cigarettes (EC) on the developing brain: the relationship between vaping-induced oxidative stress and adolescent/young adults social maladjustment. J Adolesc. 2019;76(1):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan GCK, Stjepanović D, Lim C, et al. Gateway or common liability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of adolescent e-cigarette use and future smoking initiation. Addiction. 2021;116(4):743–756. doi: 10.1111/add.15246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien D, Long J, Quigley J, Lee C, McCarthy A, Kavanagh P. Association between electronic cigarette use and tobacco cigarette smoking initiation in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):954. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10935-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CY, Paek YJ, Seo HG, et al. Dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes is associated with higher cardiovascular risk factors in Korean men. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5612. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62545-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim T, Kang J. Association between dual use of e-cigarette and cigarette and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of a nationwide representative sample from 2013 to 2018. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):231. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01590-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the Health eHeart Study. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soneji SS, Sung HY, Primack BA, Pierce JP, Sargent JD. Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Julia C. PUBLIC COMMUNICATION CAMPAIGN EVALUATION, An environmental scan of challenges, criticisms, practice, and opportunities. Published online 2002.https://www.dors.it/documentazione/testo/200905/Public%20Communication%20Campaign%20Evaluation.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 16.Anker AE, Feeley TH, McCracken B, Lagoe CA. Measuring the effectiveness of mass-mediated health campaigns through meta-analysis. J Health Commun. 2016;21(4):439–456. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1095820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flay BR. Mass media and smoking cessation: a critical review. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(2):153–160. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.77.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaiha SM, Duemler A, Silverwood L, Razo A, Halpern-Felsher B, Walley SC. School-based e-cigarette education in Alabama: impact on knowledge of e-cigarettes, perceptions and intent to try. Addict Behav. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pentz MA, Hieftje KD, Pendergrass TM, et al. A videogame intervention for tobacco product use prevention in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2019;91:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noar SM, Rohde JA, Prentice-Dunn H, Kresovich A, Hall MG, Brewer NT. Evaluating the actual and perceived effectiveness of E-cigarette prevention advertisements among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roditis ML, Dineva A, Smith A, et al. Reactions to electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) prevention messages: results from qualitative research used to inform FDA's first youth ENDS prevention campaign. Tob Control. 2020;29(5):510–515. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055104. Published online September 10, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truth initiative. Youth smoking and vaping prevention; Published 2021. https://truthinitiative.org/what-we-do/youth-smoking-prevention-education. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 23.Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis JJ, Hardeman W. Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data) Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(99):1–188. doi: 10.3310/hta19990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struik L, Rodberg D, Sharma RH. The behavior change techniques used in Canadian online Smoking Cessation programs: content analysis. JMIR Ment Health. 2022;9(3):e35234. doi: 10.2196/35234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Struik LL, Dow-Fleisner S, Belliveau M, Thompson D, Janke R. Tactics for drawing youth to vaping: content analysis of electronic cigarette advertisements. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e18943. doi: 10.2196/18943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Morean ME, Krishnan-Sarin S. Preference for gain- or loss-framed electronic cigarette prevention messages. Addict Behav. 2016;62:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popova L, Fairman RT, Akani B, Dixon K, Weaver SR. “Don't do vape, bro!” A qualitative study of youth's and parents’ reactions to e-cigarette prevention advertisements. Addict Behav. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho YJ, Thrasher JF, Reid JL, Hitchman S, Hammond D. Youth self-reported exposure to and perceptions of vaping advertisements: findings from the 2017 International Tobacco Control Youth Tobacco and Vaping Survey. Prev Med. 2019;126 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padon AA, Lochbuehler K, Maloney EK, Cappella JN. A randomized trial of the effect of youth appealing E-cigarette advertising on susceptibility to use E-cigarettes among youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(8):954–961. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vassey J, Metayer C, Kennedy CJ, Whitehead TP. #Vape: Measuring E-Cigarette Influence on Instagram With Deep Learning and Text Analysis. Front Commun (Lausanne) 2020;4 doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.England KJ, Edwards AL, Paulson AC, Libby EP, Harrell PT, Mondejar KA. Rethink Vape: development and evaluation of a risk communication campaign to prevent youth E-cigarette use. Addict Behav. 2021;113 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelder SH, Mantey DS, van Dusen D, Case K, Haas A, Springer AE. A middle school program to prevent E-cigarette use: A pilot study of “CATCH My Breath.”. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(2):220–229. doi: 10.1177/0033354919900887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weser VU, Duncan LR, Pendergrass TM, Fernandes CS, Fiellin LE, Hieftje KD. A quasi-experimental test of a virtual reality game prototype for adolescent E-Cigarette prevention. Addict Behav. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stalgaitis CA, Djakaria M, Jordan JW. The vaping teenager: understanding the psychographics and interests of adolescent vape users to inform health communication campaigns. Tob Use Insights. 2020;13 doi: 10.1177/1179173X20945695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galderisi A, Ferraro VA, Caserotti M, Quareni L, Perilongo G, Baraldi E. Protecting youth from the vaping epidemic. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(suppl 26):66–68. doi: 10.1111/pai.13348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel M, Czaplicki L, Perks SN, et al. Parents’ awareness and perceptions of JUUL and other E-cigarettes. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(5):695–699. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crossland J. Parental perceptions of e-cigarette and vaping usage among single-sex, school-going adolescents in Toronto, Canada. Young Res. 2019;3(1):23–32. http://www.theyoungresearcher.com/papers/crossland.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czaplicki L, Perks SN, Liu M, et al. Support for E-cigarette and tobacco control policies among parents of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(7):1139–1147. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García del Castillo JA, García del Castillo-López Á, Dias PC, García-Castillo F. Social networks as tools for the prevention and promotion of health among youth. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2020;33(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s41155-020-00150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022; 2022.Pew Research Centre.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/#:~:text=YouTube%20stands%20out%20as%20the,%25)%20and%20Snapchat%20(59%25). Accessed January 3, 2023.