Abstract

Chalk talks are a ubiquitous teaching strategy in both pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine and medicine in general; yet, trainees and early career faculty are rarely taught how to design, prepare, and present a chalk talk. Skills necessary to deliver a chalk talk are transferable to other settings, such as the bedside, wards during rounds, and virtual classrooms. As a teaching strategy, the chalk talk can involve learners at multiple levels, foster practical knowledge, stimulate self-assessment, encourage the generation of broad differential diagnoses, and promote an interactive learning environment. Suited for both formal and informal learning, the chalk talk can be prepared well in advance or, after some practice, can be presented “on the fly.” Furthermore, often on the wards or in the intensive care unit, team members are asked to “teach the rest of the team” at some point during rounds. There is little guidance in medical education for students and trainees to prepare for how to do this, and the chalk talk can serve as an excellent format and teaching strategy to “teach the team” when tasked to do so. To highlight our perspectives on best practices in using the chalk talk format effectively, we first briefly review the literature surrounding this very common yet understudied teaching strategy. We then provide a primer on how to design, develop, and deliver a chalk talk as a resource for how we teach residents, fellows, and early career attendings to deliver their own chalk talks.

Keywords: chalk talk, on shift teaching, undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, teaching skills

The Chalk Talk as a Necessary Skill

The chalk talk is a prevalent education strategy within medicine that is often demonstrated but rarely explicitly taught. Defined as a discussion or didactic session using a writing instrument and surface, a chalk talk can encompass anything from a teaching session held in front of a whiteboard, a “teachable moment” diagrammed on paper during rounds, a patient-centered explanation of a new diagnosis on the back of a visit summary, or a whiteboard session between an instructor and students via an online interface, such as Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc.). In critical care medicine, chalk talks are ideal for the multitude of learning opportunities that present themselves while teams are on-service in the intensive care unit (ICU). Opportunities to employ chalk talks in the ICU include formal preround teaching, bedside teaching during rounds, and teaching during task completion after rounds when patients’ clinical courses change or procedures may be required.

Chalk talks have proved useful in formal and informal teaching settings (1–5). Chalk talks are a strategy that can involve learners at multiple levels, foster practical knowledge, stimulate self-assessment, encourage the generation of broad differential diagnoses, and promote an interactive learning environment (4, 6). An engaging chalk talk is a dynamic approach to content dissemination and elaboration and is more memorable than static diagrams presented on slides (7–9). Chalk talks can progress at the learners’ pace; the inherent need to pause while writing or waiting for learner input guarantees that the facilitator (i.e., the resident, fellow, or attending delivering the chalk talk) creates space for questions or clarifications before advancing to the next topic. In addition, chalk talks use retention-promoting visual aids that encourage effective learning in easily digestible blocks. These qualities of a chalk talk, coupled with the opportunities to build on learners’ prior knowledge and to actively apply the learning objectives to clinical practice, make chalk talks a formidable example of adult learning theory in practice (10).

Ultimately, educators may wonder how the chalk talk differentiates itself from a typical lecture format or more condensed didactic moments during which the educator may deliver a several-minutes-long monologue imbuing learners with high-yield teaching points. Although chalk talks and lectures can both be prepared in advance, chalk talks often lend themselves to a “cognitivist approach” that organizes and sequences information in a way that optimizes comprehension and future application during interactive and small-group teaching, as Stetson and Dhaliwal highlighted (11). Chalk talks rely on educators to draw or record the information to be acquired by learners, which allows them to be less prone to the possible information overload of “busy” slides yet more prone to the possible underretention of lecturing/talking alone or even text-based teaching (12, 13). Finally, a traditional lecture format often implies “speaking at” or “presenting to” learners, whereas the ideal chalk talk, as we aim to delineate in this primer, encourages educators to use learner input in such a way that the chalk talk is “drawn with” or “constructed alongside” learners.

Educating Trainees/Faculty on How to Teach Using Chalk Talks

Residents, fellows, and early career faculty attempting to teach using the chalk talk format often require guidance on doing so effectively. Although teaching is a vital aspect of being a physician (14), a large majority of residents and fellows are reluctant when it comes to teaching, often citing a lack of familiarity, practice, and strategies for developing a teaching plan and interacting with learners (15). In an effort to foster longitudinal growth of future physician-educators, several resident-as-teacher courses have been developed, though these courses are not yet widely implemented (14, 16–19). Of existing curricula aimed at preparing medical trainees to teach, many programs include lessons on learning theory, asking questions, giving feedback, creating assessments, implementing microskills, and teaching at the bedside (16, 17, 20–22).

Although resources have recently been developed to create “chalk talk teaching banks” (23, 24), the skills needed to independently develop chalk talks are not emphasized in resident-as-teacher curricula, and only a limited subset prepare trainees to apply skills related to chalk talks, such as concept mapping (23, 25, 26). In pilots of these chalk talk–based programs, feedback from trainees was overwhelmingly positive, although overall training materials are limited (4, 6, 7, 24). Despite emerging recognition of the chalk talk as an essential skill in medical teaching, there is no unified framework on how to develop and deliver an effective chalk talk in the clinical setting. Furthermore, by emphasizing these critical teaching skills for residents, fellows, and even early career faculty, it is possible to enforce habits that make for better senior physician-educators. The skills acquired developing a chalk talk are also transferable to other teaching settings and may enhance “just-in-time” teaching on the wards (i.e., pedagogy of engaged learning that invites students to actively construct new knowledge from prior knowledge/experience) (27), peri-encounter debriefing (10), and bedside or in-office education of patients (14, 15).

To address the absence of high-quality guidance on how to develop and deliver effective chalk talks, we developed a primer to guide interested residents, fellows, and early career attendings in developing and implementing chalk talks. The strategies described in this primer can easily be transferred to multiple settings and specialties within pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, including the ICU, the ambulatory clinic, the medical wards, and consultative services. This primer is intended as a starting point for those who are interested in developing their skills in teaching with chalk talks, as well as those who do not know where to begin after being asked to present a chalk talk or being tasked with generally “teaching the team” during rounds. Because “teaching the team” often implies that teaching will be done on rounds without a screen or slide deck, the chalk talk is an ideal strategy that trainees may be initially uncomfortable employing. Regardless of the setting or audience, learning how to develop and deliver a chalk talk will help trainees establish an essential skill for their careers in medicine.

How to Develop, Prepare, and Deliver a Chalk Talk: A Primer

General Approach and Rationale

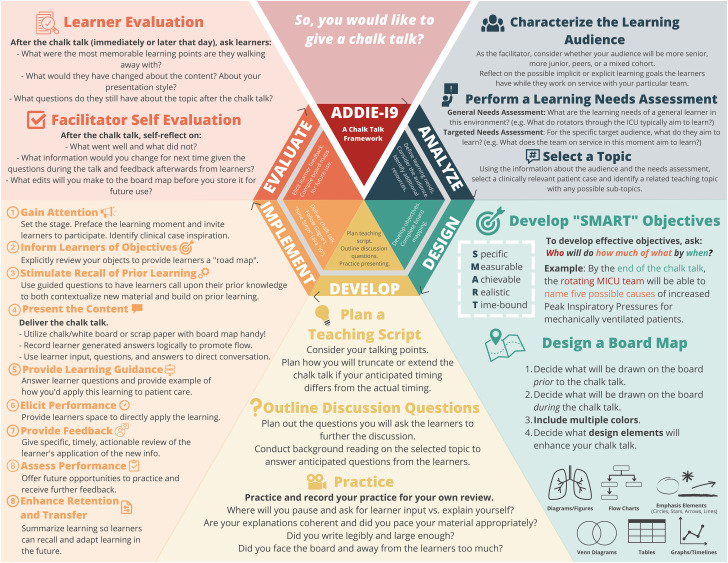

To unify the literature surrounding the chalk talk as a teaching strategy with our own experience integrating chalk talks into our clinical practice, we sought to develop an approach that was grounded in instructional design and theory. As a preparatory model, we found the “ADDIE” (analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate) model to be the most learner-centric and most easily implemented (28). In reviewing the literature, we found no prior examples of applying the ADDIE model to medical education interventions. Given that the chalk talk is so dynamic during its implementation, we also believed that a framework was necessary for the “implement” phase of ADDIE. We found the most systematic and applicable framework for the “implement” phase to be the “nine events of instruction,” which was developed by Gagné as a part of his book The Conditions of Learning and Theory of Instruction (29). This nine-step process has served as a model for developing effective and engaging teaching activities both within and outside of medicine. In curricular development, the nine events call on a learning stimulus and subsequent interactions between instructors and learners to promote improved learning. We refer to our chalk talk preparation, design, and delivery framework as the “ADDIE-I9,” which can serve as a straightforward guide for new and developing medical educators. The novel ADDIE-I9 framework is detailed below and illustrated in Figure 1 with further explanation of Figure 1 provided in the accompanying video (see Video in the data supplement).

Figure 1.

ADDIE-I9 schema, workflow, and primer: a quick reference guide for trainees as they approach the development, preparation, and implementation of a chalk talk. Development hinges on identifying “SMART objectives” and designing a board map. Design strategies such as arrows, circles, lines, and other connectors allow real-time annotation of the board. Tables and figures are also useful to organize detailed information. Preparation relies on background reading, question development, contingency planning, and rehearsing. Implementation relies on the application of Gagné’s nine steps, as outlined. Finally, after presenting the chalk talk, it is necessary to evaluate, redesign, and save the chalk talk for future use. Please use Figure 1 in conjunction with the supplemental video, which walks through a demonstration of developing and delivering a chalk talk. ADDIE-I9 = analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate-Gagné’s nine events of instruction; SMART = Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Timely.

Sample Case Scenario

For the purposes of the examples in this primer, we will walk you through how to give a chalk talk related to Mr. Rivers, a patient currently in the ICU. Imagine you are the senior resident or fellow teaching junior residents, medical students, the pharmacist, and the attending on rounds. Before rounds, Mr. Rivers, who has a history of congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and diabetes and is currently mechanically ventilated for distributive shock in the setting of urosepsis, develops worsening hypoxia and increasing peak inspiratory pressures (PIPs). Given his challenging clinical course, you decide to take 15 minutes before rounds to teach on the suspected etiology, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, at the bedside on a piece of paper. See Video for more detail.

Analyze

During the “analyze” phase of the model, it is necessary to consider and define the learning needs of the group. Broadly speaking, it is first necessary to consider the audience of learners. Next, one can perform a formal or informal needs assessment to assess prior experiences or questions from this audience. Finally, the educator should reflect on the necessary resources and/or teaching topics that may address these learning needs.

Audience

First, one should identify whether the learners will be peers, more junior, or more senior to each other. Table 1 identifies several questions the facilitator may reflect on before developing their chalk talk so that the learning opportunity may be most beneficial to their likely audience of learners. By asking these questions, the facilitator can leverage their own experience to identify the potential learning needs of the learners and identify an appropriate topic for the session.

Table 1.

Considering audience and scope

| Important Considerations to Make Regarding a Chalk Talk’s Audience |

|---|

| Teaching

learners who are peers to the facilitator Ask: What questions have I recently asked, read about, or developed a new understanding of during my own clinical learning experience? Teaching learners who are junior to the facilitator Ask: When I was at their stage of training, what concept(s) did I personally find difficult to understand? Ask: On what topic(s) did I require additional teaching, reading, or explaining? Teaching learners who are senior to the facilitator Ask: What new and potentially unfamiliar guidelines or studies have recently been published that may be beneficial to review? Ask: What uncommon diagnoses or procedures have been encountered together while on service that may be beneficial for the whole team to discuss and review? Teaching to a mixed group of learners Ask: What content will be new for certain learners, and what will be a review for others? Ask: What expertise of senior learners can be leveraged to move the chalk talk along but also engage the junior learners? Ask: What information presented will engage each learner, and could learning objectives vary by the level of the learner? |

| Important Considerations to Make Regarding a Chalk Talk’s Topic/Scope |

|---|

| Diagnosis-focused topics Ask: For a particular diagnosis, what aspect is often most challenging for learners? Is it the pathophysiology, workup, management, etc.? Ask: Are there diagnoses on the differential that are also worth highlighting and giving space to during a longer chalk talk? Procedure-focused topics Ask: What evidence exists and may be important to review about best practices for procedures? Ask: What are rare but lifesaving procedures that should be reviewed by discussing indications, supplies, or process? Ask: What are the often neglected but important pieces of a procedure that we do not often receive teaching on (e.g., postintubation sedation plans)? Trial-focused topics Ask: How would this trial change practice patterns when caring for similar patients? Ask: Would a discussion of the methodology and conclusions drawn in a trial be beneficial to the team and their conceptualization of that trial or future trials in clinical practice? |

Before selecting a topic for the chalk talk, it is essential to define the audience and the audience’s stage of clinical development/learning. Considering the questions above and any further questions inspired by the suggested list presented here may aid in the successful selection of a teaching topic best suited for the intended audience of learners. After identifying the characteristics of the audience, consider the topic of the talk, which may be, but certainly is not limited to, a pathophysiology, diagnosis, procedure, or trial-focused topic. Initial questions are provided that may guide the process of determining a talk’s scope within a given topic.

Assessing Learning Needs

Described by Kern and colleagues, a needs assessment provides educators and facilitators with insight into their learners’ preexisting gaps in knowledge or skill (30). Kern and colleagues highlight that there are general and targeted needs assessments. The general needs assessment focuses on the common learning needs for any given context (e.g., learners rotate through the ICU to understand care of the critical patient, which often includes ventilatory physiology/support, circulatory physiology/support, goals of care, etc.), as well as the differences between the current and ideal approach (e.g., how the team is currently managing Mr. Rivers’s increasing PIP vs. how a diagnosis-driven approach may improve ventilation settings). In context, the facilitator can make generalized assumptions about the learning needs of most learners who come through the ICU. Therefore, the facilitator can develop a predetermined bank of learning topics and associated chalk talks to address common learning needs. The targeted needs assessment focuses on the needs of a specific group of learners. To conduct a quick, informal targeted needs assessment, the facilitator can ask the current ICU team about their personal learning goals for their time on service, identify current patient cases that pose a physiologic or management-based challenge for the team, or focus on the common questions/points of weakness during case presentations on the first few days on-service to determine team-specific learning needs. Using this information, targeted topics can be selected for possible chalk talks.

Topic Selection and Scope

Needs assessments define various topics that may be beneficial as core content for chalk talks. Within a selected topic, it is critical to define the scope of the content that will be covered. Chalk talks need not be dense or comprehensive. Although longer chalk talks may allow a deeper discussion of a topic, the chalk talk is often an exercise in “bite-sized teaching,” or a distilled discussion of focused content (31). By narrowing the topic by time, audience, and learning need, the chalk talk can be both manageable and high yield in the context of time constraints (Table 1).

Design

The next phase, design, encompasses the process of specifying how learning will be achieved. Given that we have already identified that this will be a chalk talk, the standard ADDIE requirement of determining the presentation format has already been determined. For our purposes, the design highlights objective development and chalk talk board mapping, defined below.

Objective Development

A critical step of teaching using chalk talks is to create clear objectives for the chalk talk and discussion. Objectives should be focused and realistic and should lead to a measurable outcome (e.g., “recognize two diagnoses,” “describe three mechanisms”). Resources are available about writing SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based) objectives (Figure 1 and Video) (32). The number of objectives should correlate with the intended length of the chalk talk; brief 5- to 10-minute chalk talks should have one objective, whereas longer 20- to 40-minute talks may have three to five objectives. For chalk talks, one objective per 5 minutes of content is ideal, with a maximum of five total (33). Be sure to summarize the relationship between the objective(s) and at least one aspect of the audience’s clinical experience, because this will contextualize the objective(s) in the learners’ clinical activities and make explicit the learning needs the objectives address.

Board Map Creation

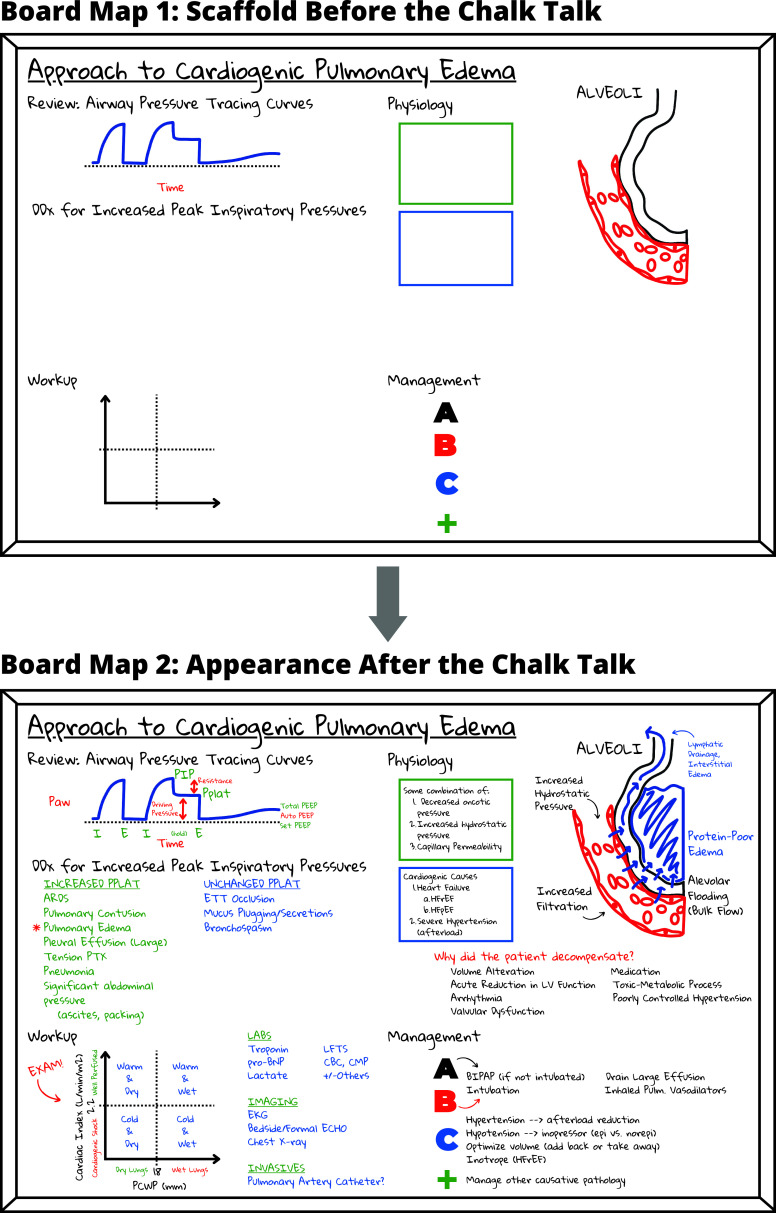

Developing a “board map” is critical when preparing a chalk talk (34). The board map is a two-panel diagram of what the board will look like before and after the chalk talk (Figure 2). The board map is the visual anchor for the talk, providing a visual and organizational structure to follow. Supplemental notes on a few additional points not covered explicitly on the board map can also be developed if helpful for the facilitator. Developing a board map is an opportunity to think critically about the graphics that will be used and how the board will evolve and develop over the course of the chalk talk.

Figure 2.

Sample board map: a sample board map is provided for a possible discussion on cardiogenic pulmonary edema in the setting of worsening ventilator settings for more junior learners in the intensive care unit. The first panel (top) depicts what the facilitator will draw on the board before the start of the chalk talk. The second panel (bottom) depicts the outcome of the chalk talk on the board and includes all information that the facilitator plans to record throughout the learning session.

One can start with a blank board and therefore a blank first panel on the board map. However, some graphics are difficult to set up or draw during the session. In this case, the facilitator can set up a visual scaffold by beginning the talk with graphics already on the board (and on the first panel of the board map). When using a scaffold, planning ahead and arriving at the session early to complete the setup of the board is necessary.

The second panel of the board map will depict all the information to be recorded on the board by the end of the chalk talk. The second panel allows one to consider, visualize, and critically evaluate the arc of the talk before presenting. When designing the second panel of the board map, consider how and when each piece of information will be used during the presentation.

Often, the graphic portion of the board map is the most memorable component of the talk, so it is important to consider what imagery will be most conducive to learner engagement and learning. The graphics should be central to the session’s learning goals and objectives. Graphics can both build the session and anchor the discussion. Remember, graphics also include the annotations used and notes taken on the board (Figure 1, Video, and Table 2) (6).

Table 2.

Suggested considerations when designing and preparing a chalk talk

| Questions to Ask While Designing a Board Map |

|---|

General considerations

|

Board Map Panel

1 (image of the board before the talk)

|

Board Map Panel

2 (image of the board after the talk)

|

| Questions to Ask While Preparing the Discussion |

|---|

General

considerations

|

These questions are intended to guide the design and preparation process, particularly when it comes to designing a board map.

Development

During the development phase of preparation, facilitators prepare any necessary scripts and practice the presentation of the chalk talk to further the work done during the design phase.

Preparation and Practice

Before delivering a chalk talk, consider important talking points related to the board map. For beginners, it is helpful to plan questions in advance to ask the audience during the session. Asking questions of learners not only minimizes the time the presenter spends speaking but also promotes audience engagement, active learning, and content retention (35).

With regard to session timing, it is critical to have a backup plan by specifically considering the best way to abridge material should the group need a longer discussion of particular concepts. Because sometimes it can take less time than anticipated to go through content, drafting extra material to fill extra time after finishing the planned material is also a reasonable contingency plan.

For scheduled presentations, especially lengthier ones, practicing and video recording the chalk talk in advance can be extremely helpful. This is an important opportunity to evaluate the talk and one’s use of the board and, after constructive review and reflection on effective and ineffective presentation techniques, can result in a more polished and effective talk in real time (Figure 1 and Video).

Implementation

The implementation phase represents the effective and efficient delivery of the teaching material. As a part of our proposed framework, the facilitator can think of Gagné’s “nine steps” as a means of walking through the presentation. These steps include gain attention, inform learners of objectives, stimulate recall of prior learning, present the content, provide learning guidance, elicit performance, provide feedback, assess performance, and enhance retention/transfer.

Step 1: Gain Attention

In gaining learners’ attention, the facilitator makes explicit that the normal progression of the clinical workday will be interrupted momentarily and that learners should transition to a mindset ready to engage with the teaching points to be discussed. Gaining the learners’ attention is often best received by grounding the motivation for teaching in patient care activities. An example of gaining attention for a preselected topic based on a particular patient case on rounds may be, “Team, Mr. Rivers’s vent settings have posed a challenge for us over the course of the past couple of days. I suggest we take the next 10 minutes to discuss the causes of increased PIPs, and particularly the reason Mr. Rivers’s PIPs are increased, in a bit more detail. Perhaps then today’s plan for what we’re going to do for him might be clearer.” With an emphasis on improving patient care, this example also invites learners to consider how taking time from tasks that need to be accomplished on rounds may benefit from a temporary pause.

Step 2: Inform Learners of Objectives

Next, review the objectives developed during the design phase of planning. Explicitly reviewing the objectives provides a roadmap for the learners so that they may be able to anticipate the course of learning, prepare questions they may have, and better understand the facilitator’s goals (36). Later, having learners know the intended objectives will further guide their feedback on the session by giving them the ability to comment on the actualized objectives.

Step 3: Stimulate Recall of Prior Learning

Next, the facilitator may take a moment to engage learners on their prior experience or knowledge of the topic. Pose questions such as, “Have you ever taken care of a patient with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE), and what was challenging about it?” “What do you know about the pathophysiology of CPE?” “What do you know about the management of CPE?” or “What questions do you have about CPE, given what you know already?” These questions provide the facilitator with a real-time needs assessment that can serve as an adjunct to the targeted needs assessment done during the analyze phase, but it also invites learners to organize the new information they are about to obtain within the constructs of their prior knowledge (37).

Step 4: Present the Content

The board map will serve as a reference during the presentation. The ideal chalk talk is presented as a conversation. Educators are encouraged to facilitate discussion by adding points, asking questions, and gathering learner input. By engaging the learners in this way, the learners will feel a sense of ownership over the learning of the group and feel more connected to the teaching moment itself. It is important to anticipate what the facilitator will ask the learners during the talk and the types of responses they may provide. Record their answers in a way that moves the board and teaching agenda along while also serving as a memory aid or tool later. (For example, if the learners will list a differential diagnosis, consider grouping diagnoses or ordering them from most likely to least likely, without explicitly saying so while recording the learners’ responses.)

As an important component of presenting the content, be sure to avoid spending too much time facing the board with one’s back to the audience. Facing away from the learners will disincentivize group participation. Avoid writing too small, too much, or with too many abbreviations. Writing too much on the board invites unnecessary pauses that can hinder the talk’s momentum. Although developing a board map in advance is an attempt to address some of these handicaps, one can also use shorthand notations and common abbreviations that everyone will understand.

Avoid erasing the board during the session, and actively plan to maintain all the notes on the board throughout the talk. Maintaining what is written on the board throughout the session always keeps the whole idea in front of learners. By not erasing, learners can take a picture for review and/or future studying (Figure 1 and Video).

Step 5: Provide Learning Guidance

Learning guidance is the act of ensuring that knowledge provided by the session is later transferable to future practice. By asking the discussion-leading questions prepared during the development phase and by inviting learners to ask questions as the chalk talk progresses, the facilitator can provide learning guidance. Of note, “discussion-leading questions” are best viewed as preplanned or scripted questions posited by the educator that allow learners to provide answers that aid in navigating to the next discussion point or learning objective. By providing a response and natural transition with their response, the learners dictate the pace both of discussion and of transitions, which allows any needed clarification or additional explanation on the part of the educator if the discussion does not advance at the expected pace. Discussion-leading questions also highlight which information the learners should know or will know by the end of the session. Encouraging learners to also generate their own questions about the material allows educators to provide guidance as they correct misconceptions, fill in gaps, clarify difficult concepts, and redirect learners back to the learning objectives. In addition, the facilitator may choose to return to the case and demonstrate how they themselves would interpret the material covered in the session to alter their clinical practice (e.g., “Now that we’ve reviewed this, I might approach the case of Mr. Rivers in the following way…”).

Step 6: Elicit Performance

During this step, allow learners to perform and demonstrate their application of the newly acquired knowledge. If time permits, the facilitator may provide a fictional, similar, yet different patient case and ask learners to walk through the case in a manner similar to what had been demonstrated in Step 5. If time does not permit, the facilitator may ask the learners to return to the initial assessment and plan that was presented for the patient during rounds and ask, “Knowing this now, how would your assessment and plan change?” or “How might you now think about Mr. Rivers’s case differently going forward?”

Step 7: Provide Feedback

Feedback from the facilitator on learner performance is critical to the learner’s ability to successfully contextualize the newly acquired knowledge. In the case of a chalk talk and the application of these steps, feedback is typically quite expedient. However, the facilitator should take time to make specific comments regarding the learners’ performance in Step 6. The most beneficial feedback is specific (e.g., “you said ___,” “you chose ___,” etc.) and actionable.

Step 8: Assess Performance

Subsequently, the facilitator may offer opportunities to assess performance. Giving learners the chance to act on the feedback they received allows them to further reinforce learning. This chance at performance may occur during the presentation of a similar patient later on rounds, during procedural time later on-service, or while admitting a new patient on-service later that week. Explicitly coming back to the teaching session is always beneficial if there is time between the performances and being explicit about the intention to look for these opportunities: “When we discuss Ms. Brooks later, let’s try to apply this information as well,” “I’ll be looking out for patients similar to Mr. Rivers over the course of the week to remind us of this session.”

Step 9: Enhance Retention and Transfer

The final step emphasizes the learners’ ability to recall the information in the future (retention) and adapt the information for future different scenarios (transfer). Upon completing the presentation, a summary of the key “takeaways” of the chalk talk allows a review of the final board map and reinforces future retention. Reiterating the initial learning objective(s) for the session during the summary demonstrates how the chalk talk accomplished the session’s learning goal(s). Reminding learners of the talk’s relationship to actual patient care will also highlight the covered material’s relevance. Finally, adding a final knowledge assessment at the end of the presentation may allow the early formation of transfer skills. Optionally, the facilitator may direct learners to related supplemental materials that they may seek out later to promote a mixed-learning strategy (38).

Evaluation

At the end of the chalk talk, the facilitator enters the evaluation phase. Attempt to find time to gather feedback from the learners. The most basic feedback will assess whether the learners found the chalk talk useful or perceived it as beneficial to their learning. More in-depth feedback can include suggestions for improvement, unanswered questions remaining, and assessment of acquired knowledge. This information will allow iterative modification to the chalk talk and the facilitator’s delivery to enhance future presentations.

Of Note: After the Chalk Talk

Save the board map after the session. Collecting board maps and the associated teaching scripts as they are created serves as a repertoire of teaching material one can use in the future (e.g., in a teaching portfolio) (6, 23). Similarly, taking a picture of the board after the presentation provides an opportunity for the facilitator to review the teaching session and identify how the board might be modified for further sessions.

Of Note: Teaching “on the Fly”

Because of the inherent flexibility of the chalk talk format, this technique is often employed while teaching “on the fly” in moments of spontaneous downtime while on-service (31). The proposed ADDIE-I9 format outlined above incorporates several preparatory steps that make teaching “on the fly” feel much less spontaneous. However, for those interested in newly incorporating this technique into their teaching repertoire, we uphold that preparation and practice will be necessary while learning the technique. Identifying topics or preparing banks of chalk talks ahead of time as demonstrated in Video, although requiring some advance preparation, does allow future spontaneous teaching when time permits. For those new to developing chalk talks, we anticipate that the preparatory steps for the ADDIE-I9 framework (i.e., everything before delivering and implementing the chalk talk) may take approximately 1 hour to complete (accounting for more or less time, depending on how much additional reading on the topic the educator may want to do in anticipation of learner questions. As educators become increasingly more comfortable with the ADDIE-I9 framework or their own adapted method for delivering a chalk talk, we anticipate that the preparatory time will decrease significantly and will feel more spontaneous and “on the fly.” Furthermore, less preparatory work will be necessary when implementing a chalk talk from the educator’s stored bank of material. Evaluating your chalk talk each time is crucial because this process is iterative. Every implementation of the same chalk talk may look somewhat different, depending on learners or clinical contexts in which the same talk is given, another benefit of the chalk talk’s flexibility.

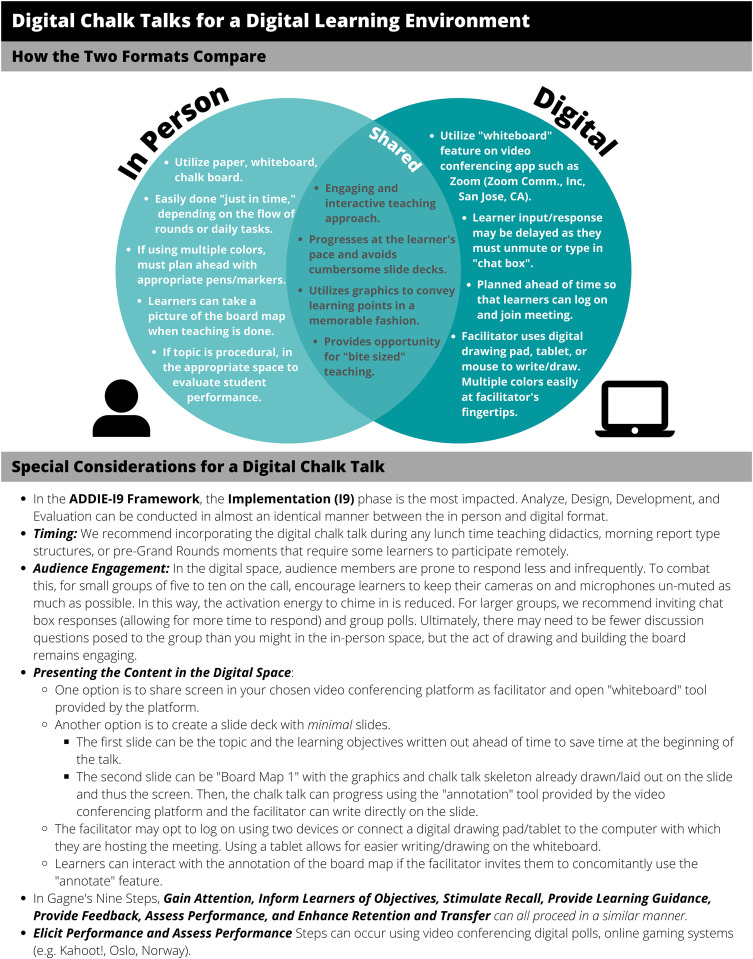

Of Note: Adaptations for the World of Digital Learning

Given the circumstances of today’s learning environments, the world of medical education has entered a digital space. Often, people associate chalk talks with in-person learning; however, we assert that in conjunction with online teaching best practices, such as those outlined by Ohnigian and colleagues, the chalk talk certainly has a place in online learning (39). The ADDIE-I9 model that we propose may still be applied to online learning with some modifications, outlined in Figure 3. Of particular interest in digital or virtual teaching, the digital board map is quite flexible and adaptable. Facilitators may choose to develop board maps using the same programs they would for slide presentations (e.g., Microsoft PowerPoint [Microsoft Corp.]), which can allow higher-resolution figures and ease of reuse in the future. If you do develop these digital board maps, the “empty board map” or equivalent of “Board Map 1” in Figure 2 could also be printed out and brought to teaching sessions/discussions in the same way a small whiteboard or piece of scrap paper can. If the facilitator opts not to use slide-building software, board maps can be hand drawn digitally on whiteboard applications (e.g., Explain Everything or Zoom built-in Whiteboard feature), both remotely and in person. Digital versions of board maps may also be saved after completion to be printed or shared with learners for future reference.

Figure 3.

Adapting chalk talks to digital learning; although there are distinct differences between a chalk talk conducted in person and digitally, there are similarities. The implementation phase of ADDIE-I9 is most affected in the digital space. Here suggestions are provided for the adaptation of the I9 portion of the framework to the digital space (45, 46). Digital chalk talks can also be done asynchronously and filmed ahead of time, a practice that Rana and colleagues outline extensively (47). ADDIE-I9 = analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate-Gagné’s nine events of instruction.

Summary

The chalk talk is a ubiquitous teaching method used not only in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine but in all medical specialties and at all levels of teaching and learning. The chalk talk provides an active learning technique that engages learners (40). Promotion of active learning enhances the learner’s experience, clinical understanding, and patient management (41, 42). Chalk talks do have limits, however, because they are not suited for teaching about detailed topics that include complex diagrams, detailed anatomy instruction, or large quantities of terminology (12, 43). However, facilitators may consider hybrid PowerPoint–chalk talk strategies that use the strengths while bypassing the limitations of both modalities (42, 44). Trainees are infrequently taught how to consider, design, prepare for, and deliver an effective chalk talk or teach on the wards. This guide details the ADDIE-I9 approach, with specific, actionable strategies for developing effective and engaging chalk talks. By using chalk talks in their teaching, residents, fellows, and early career attendings can develop effective skills for successful careers in the practice of medicine that emphasize both teaching and learning.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Each of the listed authors has contributed significantly to the writing and review of this article.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Bassendowski SL. Chalk and talk assessment strategy. Nurse Educ . 2004;29:224–225. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shallcross DE, Harrison TG. Lectures: electronic presentations versus chalk and talk—a chemist’s view. Chem Educ Res Pract . 2007;8:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waters CM.Rock the Chalk: a five-year comparative analysis of a large microbiology lecture course reveals improved outcomes of chalk-talk compared to PowerPoint. 2019. [DOI]

- 4. Sheng A, Eicken J, Lynn Horton C, Nadel E, Takayesu J. Interactive format is favoured in case conference. Clin Teach . 2015;12:241–245. doi: 10.1111/tct.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betharia S. Combining chalk talk with PowerPoint to increase in-class student engagement. Innov Pharm . 2016;7:13. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pitt MB, Orlander JD. Bringing mini-chalk talks to the bedside to enhance clinical teaching. Med Educ Online . 2017;22:1264120. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1264120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orlander JD. Twelve tips for use of a white board in clinical teaching: reviving the chalk talk. Med Teach . 2007;29:89–92. doi: 10.1080/01421590701287913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santhosh L, Brown W, Ferreira J, Niroula A, Carlos WG. Practical tips for ICU bedside teaching. Chest . 2018;154:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas M, Appala Raju B. Are PowerPoint presentations fulfilling its purpose. South East Asian J Med Educ. . 2007;1:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor DCM, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach . 2013;35:e1561–e1572. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.828153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stetson GV, Dhaliwal G. Chalk talks in the clinical learning environment. Acad Med . 2023;98:534. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh N, Phoon CKL. Not yet a dinosaur: the chalk talk. Adv Physiol Educ . 2021;45:61–66. doi: 10.1152/advan.00126.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson RE, Richards JB, Ricotta DN. Strategies to elevate whiteboard mini lectures. Clin Teach . 2022;19:79–85. doi: 10.1111/tct.13479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erlich DR, Shaughnessy AF. Student-teacher education programme (STEP) by step: transforming medical students into competent, confident teachers. Med Teach . 2014;36:322–332. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.887835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dotters-Katz S, Hargett CW, Zaas AK, Criscione-Schreiber LG. What motivates residents to teach? The Attitudes in Clinical Teaching study. Med Educ . 2016;50:768–777. doi: 10.1111/medu.13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hill AG, Yu TC, Barrow M, Hattie J. A systematic review of resident-as-teacher programmes. Med Educ . 2009;43:1129–1140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farrell SE, Pacella C, Egan D, Hogan V, Wang E, Bhatia K, et al. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Undergraduate Education Committee Resident-as-teacher: a suggested curriculum for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med . 2006;13:677–679. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zackoff MW, Real FJ, DeBlasio D, Spaulding JR, Sobolewski B, Unaka N, et al. Objective assessment of resident teaching competency through a longitudinal, clinically integrated, resident-as-teacher curriculum. Acad Pediatr . 2019;19:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeung C, Friesen F, Farr S, Law M, Albert L. Development and implementation of a longitudinal students as teachers program: participant satisfaction and implications for medical student teaching and learning. BMC Med Educ . 2017;17:28. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0857-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu TC, Wilson NC, Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract . 2011;2:157–172. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S14383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach . 2007;29:558–565. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrell H, Wipf J, Aronowitz P, Rencic J, Smith DG, Hingle S, et al. Resident as teacher curriculum. MedEdPORTAL . 2015;11:10001. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cawkwell PB, Jaffee EG, Frederick D, Gerken AT, Vestal HS, Stoklosa J. Empowering clinician-educators with chalk talk teaching scripts. Acad Psychiatry . 2019;43:447–450. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01042-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mookherjee S, Cosgrove EM. Handbook of clinical teaching. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dattilo WR, Gagliardi JP, Holmer SA. The concept of “concept mapping” is useful in teaching residents to teach. Acad Psychiatry . 2017;41:542–546. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Price J, Knee A, Koenigs L, Mackie S. Bringing back the chalk talk: a novel curriculum utilizing the mini chalk talk to improve clinical teaching in a pediatric residency program [abstract] Acad Pediatr . 2019;19:e15–e16. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schuller MC, DaRosa DA, Crandall ML. Using just-in-time teaching and peer instruction in a residency program’s core curriculum: enhancing satisfaction, engagement, and retention. Acad Med . 2015;90:384–391. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Branch RM. Instructional design: the ADDIE approach. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gagné RM. The conditions of learning and theory of instruction. 4th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Tackett SA, Chen BY. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manning KD, Spicer JO, Golub L, Akbashev M, Klein R. The micro revolution: effect of Bite-Sized Teaching (BST) on learner engagement and learning in postgraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ . 2021;21:69. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02496-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chatterjee D, Corral J. How to write well-defined learning objectives. J Educ Perioper Med . 2017;19:E610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy D, Hyland A, Ryan N. In: EUA Bologna Handbook. Froment E, Kohler J, Purser L, Wilson L, editors. Berlin: Raabe; 2006. pp. C3.4–1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger GN, Kritek PA. In: Handbook of clinical teaching. Mookherjee S, Cosgrove EM, editors. New York: Springer; 2016. How to give a great “chalk talk.”; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kornell N, Hays MJ, Bjork RA. Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn . 2009;35:989–998. doi: 10.1037/a0015729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeSilets LD. Using objectives as a road map. J Contin Educ Nurs . 2007;38:196–197. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20070901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kang S. Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci . 2016;3:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Kesteren MTR, Rijpkema M, Ruiter DJ, Morris RGM, Fernández G. Building on prior knowledge: schema-dependent encoding processes relate to academic performance. J Cogn Neurosci . 2014;26:2250–2261. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ohnigian S, Richards JB, Monette DL, Roberts DH. Optimizing remote learning: leveraging Zoom to develop and implement successful education sessions. J Med Educ Curric Dev . 2021;8:23821205211020760. doi: 10.1177/23821205211020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolff M, Wagner MJ, Poznanski S, Schiller J, Santen S. Not another boring lecture: engaging learners with active learning techniques. J Emerg Med . 2015;48:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao B, Potter DD. Comparison of lecture-based learning vs discussion-based learning in undergraduate medical students. J Surg Educ . 2016;73:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lenz PH, McCallister JW, Luks AM, Le TT, Fessler HE. Practical strategies for effective lectures. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2015;12:561–566. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-024AR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jabeen N, Ghani A. Comparison of the traditional chalk and board lecture system versus Power Point presentation as a teaching technique for teaching gross anatomy to the first professional medical students. J Evol Med Dent Sci . 2015;4:1811–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Demirseren ME, Otsuka T, Satoh K, Hosaka Y. Training of plastic surgery on the white board. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2003;111:1757–1758. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200304150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS. Medical education during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis . 2020;27:412–417. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mistry R, Glaser A. The upfront cost of translating graduate medical education into a virtual platform. Adv Clin Med Res Healthc Deliv . 2021;1 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rana J, Besche H, Cockrill B. Twelve tips for the production of digital chalk-talk videos. Med Teach . 2017;39:653–659. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1302081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]