Abstract

Background

Loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab in ulcerative colitis occurs frequently, and dose escalation may aid in regaining clinical benefit. This study aimed to systematically assess the annual loss of response and dose escalation rates for infliximab and adalimumab in ulcerative colitis.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted from August 1999 to July 2021 for studies reporting loss of response and dose escalation during infliximab and/or adalimumab use in ulcerative colitis patients with primary response. Annual loss of response, dose escalation rates, and clinical benefit after dose escalation were calculated. Subgroup analyses were performed for studies with 1-year follow-up or less.

Results

We included 50 unique studies assessing loss of response (infliximab, n = 24; adalimumab, n = 21) or dose escalation (infliximab, n = 21; adalimumab, n = 16). The pooled annual loss of response for infliximab was 10.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.1-14.3) and 13.6% (95% CI, 9.3-19.9) for studies with 1-year follow-up. The pooled annual loss of response for adalimumab was 13.4% (95% CI, 8.2-21.8) and 23.3% (95% CI, 15.4-35.1) for studies with 1-year follow-up. Annual pooled dose escalation rates were 13.8% (95% CI, 8.7-21.7) for infliximab and 21.3% (95% CI, 14.4-31.3) for adalimumab, regaining clinical benefit in 72.4% and 52.3%, respectively.

Conclusions

Annual loss of response was 10% for infliximab and 13% for adalimumab, with higher rates during the first year. Annual dose escalation rates were 14% (infliximab) and 21% (adalimumab), with clinical benefit in 72% and 52%, respectively. Uniform definitions are needed to facilitate more robust evaluations.

Keywords: anti-TNF, loss of response, ulcerative colitis, dose escalation

Key Messages.

What is already known?

A proportion of patients develop loss of response after initial response to anti-TNF for ulcerative colitis, and these patients may regain therapeutic effect following dose escalation.

What is new here?

In this meta-analysis, we found pooled annual loss of response risks of 10% and 13% and pooled annual dose escalation rates of 14% and 21% for infliximab and adalimumab, respectively—with higher rates in the first year.

How can this study help patient care?

The results from our meta-analysis support strict disease monitoring during the first year of anti-TNF treatment and the value of dose escalation to regain therapeutic effect.

Introduction

Antitumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF) agents are essential therapeutics in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (UC). In 2005, infliximab (IFX) was the first anti-TNF agent approved by the Food and Drug administration (FDA) and European Medication Agency (EMA) for the treatment of moderate to severe UC.1 Infliximab is an IgG1 mouse-human chimeric monoclonal antibody neutralizing the effects of TNF, resulting in potent anti-inflammatory effects. In 2012, adalimumab (ADA), a fully human monoclonal antibody, was approved for the treatment of UC.2 According to label, IFX maintenance therapy is dosed at 5 mg/kg intravenously every 8 weeks, with induction infusions at week 0, 2, and 6.1 Adalimumab maintenance is dosed at a standard dose of 40 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks, with an induction schedule of 160 mg at week 0, and 80 mg at week 2.2

In general, patients with clinical response or remission after the induction period are considered primary responders to anti-TNF therapy. Disease worsening after primary response is considered loss of response (LOR).3 However, there is a wide variation in definitions in place, and consensus on definitions of primary nonresponse and LOR are lacking.3,4 To address LOR, dose escalation is possible by either a dose increase (IFX, up to 10 mg/kg; ADA, 80 mg every 2 weeks) or interval reduction (IFX to every 4-6 weeks; ADA to 40 mg weekly).5

Loss of response during IFX and ADA use in UC patients has not been systematically assessed. In Crohn’s disease, loss of clinical response at week 52 ranged from 16%-71% for IFX and 16%-47% for ADA. Annual LOR incidences, which take into account different follow-up times among studies, varied between 13%-18% following IFX initiation and 23%-25% following ADA initiation.6–8 A recent retrospective multicenter study reporting LOR rates in both Crohn’s disease and UC found an LOR percentage of 9% per patient-year in UC.9

Dose escalation has shown to be effective in achieving higher rates of mucosal healing in patients with signs of LOR.10 Annual dose escalation rates were 15% in IFX-treated Crohn’s disease patients and 24%-26% in ADA-treated Crohn’s disease patients, although follow-up varied widely (20-208 weeks); this may have impacted the annual dose escalation rates.6–8 In UC patients, overall dose escalation rates in primary responders vary between 13%-37% for IFX and 18%-55% for ADA.11–13 Despite a number of available studies, no comprehensive and systematic evaluation on LOR and dose escalation for anti-TNF in UC is available.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess (1) the annual LOR rates to IFX and ADA in adult UC patients with primary response, stratified per LOR definition; (2) the annual dose escalation rates of IFX and ADA in primary responders as a proxy for LOR; and (3) the proportion of patients regaining clinical benefit after dose escalation following loss of response.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study followed the methodology for conducting and reporting a systematic review described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and guidelines for reporting developed by the Meta-analysis of Observational studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group (Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3).14,15 The study protocol was registered in the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020160390).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library was conducted from August 1999 (date of IFX EMA approval for Crohn’s disease) to July 2021, with aid of an experienced librarian. Search algorithms included a combination of the following terms: ulcerative colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, infliximab, adalimumab, and antitumor necrosis factor (for full search strategy, see Supplementary Table 4). There were no language or study design restrictions. Two authors (E.S., P.T.) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of all studies identified in the search for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, full text of the selected articles was reviewed for availability of the outcomes of interest. A manual search of references in the included articles was performed to identify additional articles. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. If no consensus was reached, a third reviewer (F.H.) was involved for final decision-making. All search results were cross-checked for duplicates using Endnote X9.2 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Rayyan QRCI (Rayyan Systems Inc.) was used for blinded title/abstract screening.16

Selection Criteria

Clinical trials and cohort studies assessing IFX and/or ADA use in adult patients with UC were eligible for inclusion if they reported the LOR rates or dose escalation rates due to LOR, with or without the outcome of dose escalation (regaining response or remission). Studies were excluded if they were case reports or case series or if the full text was not available. Additionally, studies not using standard induction or maintenance treatment and studies primarily focusing on proactive drug monitoring were deemed inaccurate for comparison and were excluded. We did not extrapolate LOR from studies only providing clinical remission/response rates since we could not reliably account for other reasons for not reaching remission or response. In case of multiple published studies involving the same cohort, data from the most comprehensive study were included.

Data Extraction

The following information from each study was extracted: first author’s last name, year of publication, study design, anti-TNF use (IFX/ADA), and total study population characteristics (including prior exposure to anti-TNF and baseline concomitant immunomodulator use). Specific outcomes of interest included total follow-up duration following IFX or ADA initiation, number of primary responders, LOR incidence, LOR-related dose escalation incidence, dose escalation strategies, and dose escalation outcomes. Lastly, we extracted the used definitions for primary response, LOR, dose escalation, and clinical benefit of dose escalation. Data were extracted separately by ES and PT, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes included (1) the annual LOR per patient-year to IFX and ADA in UC patients, and (2) the annual dose escalation rates per patient-year for IFX and ADA in UC patients and the subsequent ability to regain therapeutic effect. Loss of response stratified per used definition was added following evaluation of study-specific definitions of LOR. Stratification per follow-up duration (≤65 weeks [52 weeks with a range of one quarter to correct for borderline follow-up time] vs >65 weeks) was added after a recent study implied time dependency of LOR.9

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses for annual LOR were carried out, including (1) the extent of disease affecting the colon; (2) the type of anti-TNF agent; (3) concomitant use of mesalamine; (4) concomitant use of immunomodulator; (5) study design; (6) prior anti-TNF agent exposure; (7) adequate trough levels and presence of antidrug antibodies; and (8) quality of studies.

Definitions

Loss of response describes patients who responded to induction therapy but subsequently lost clinical response during maintenance treatment. Primary nonresponse was defined as no response or remission after the induction period.3 Because there is no consensus definition for primary response and LOR, we used the definitions as reported by the authors in each study.3 Consequently, LOR was categorized in 3 groups: (1) treatment discontinuation due to LOR; (2) treatment optimization defined as dose escalation or a combination of dose escalation and treatment switch and/or medical rescue therapy (including steroids and ciclosporin) and/or surgery because of LOR; and (3) increase of disease activity defined as increased clinical disease activity scores (eg, partial Mayo score, physician’s global assessment) and/or increased C-reactive protein (according to provided standards and combined with clinical or endoscopic indication of disease activity) and/or endoscopic disease worsening (according to provided standards or scores). Dose escalation was defined as any dose increase or interval shortening as reported by the authors. Dose escalation rates include all dose escalations performed in primary responders regardless of the reason for dose escalation. Regaining therapeutic effect following dose escalation was defined as recapturing clinical response and/or clinical remission. In case any study used multiple effect outcome measures, short-term clinical response or remission was used.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Information on the methodological quality of each study was extracted, and quality assessment was performed using the ROBINS-I tool for observational cohort studies and risk of bias 2 tool for randomized controlled trials, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook.17,18 In the ROBINS-I tool, 7 items can be assessed on a 5-point scale: low, moderate, serious, critical risk of bias, or no information. Details on the subdomains and scoring are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Two authors (P.T., E.S.) independently assessed risk of bias by rating every item. Discrepancies in the risk of bias judgment were resolved by discussion.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Due to large variation in follow-up among studies, we used annual rates per patient-year per study to describe the LOR and dose escalation incidence rates. The annual LOR per patient-year was calculated as follows: LOR events/ (primary responders x years of follow-up). The same method was used to calculate the annual dose escalation per patient-year. Regaining therapeutic effect following dose escalation was reported as a percentage of the total number of dose escalations. We used a random-effects model to calculate the pooled annual LOR incidence rates, annual dose escalations incidence rates, and proportion of patients regaining therapeutic effect after dose escalation, using the DerSimonian and Laird method.19 Proportion transformation was performed using the generalized linear mixed model.20 Additionally, subgroup analyses on predefined LOR definitions (described previously) were conducted for the annual LOR rates. Heterogeneity across the pooled studies was evaluated using I2 statistics, with low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity defined as <30%, 30%-59%, 60%-75%, and >75%, respectively.21 To assess the robustness of the pooled effects, influence analyses using a manual leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed.22 Publication bias was evaluated through visual inspection of funnel plots. All analyses were conducted in R Version 3.6.2 (Free Software Foundation, Inc.), using the following packages: meta and metafor for meta-analyses, and robvis for risk of bias visualization.

Results

Search Results

After removal of duplicates, the database search yielded 26 508 potentially relevant articles that were assessed for title and abstract (Supplementary Figure 2). We assessed the full text for 166 studies. Finally, we included 50 unique observational cohort studies and no randomized controlled trials on adult UC patients treated with either IFX, and/or ADA. These studies provided data on LOR incidence (n = 38),11,23–59 and/or dose escalation incidence (n = 31),11,24,26–28,31,33,37–41,47–50,53–57,59–68 and/or dose escalation outcomes (n = 15).11,12,27,31,39,50,53–56,59,62,66,69,70 Outcomes for IFX were described in 34 studies. 12,23–39,49–52,56,57,59–66,69,70 Outcomes for ADA were described in 23 studies.11,24,25,28,31,33,37,40–48,53–55,57,58,67,68 Forty-one were retrospective cohort studies, and 9 were prospective cohort studies. Characteristics of all included studies are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Definitions of primary response, LOR, and outcomes of dose escalation per study are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis of loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab.*

| Study | Year | Design | Anti-TNF | Prior Anti-TNF Exposure, in % | Concomitant IM use, in % | Follow-up, in weeks | Primary responders, n | LOR n (%) |

Annual LOR in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of response defined as discontinuation | |||||||||

| Angelison23 | 2016 | Retro | IFX | 3 | 53 | 52 | 190 | 22 (12) | 11.6 |

| Barberio24 | 2020 | Retro | IFX | 10 | 15 | 52 | 60 | 6 (10) | 10.0 |

| Bertani25 | 2020 | Pros | IFX | NA | 0 | 48 | 27 | 5 (19) | 20.1 |

| Fernandez26 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 77 | 160 | 170 | 32 (19) | 6.1 |

| García-Bosch27 | 2016 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 85 | 302 | 40 | 16 (40) | 6.9 |

| Gies28 | 2010 | Pros | IFX | 0 | 37 | 60 | 18 | 4 (22) | 19.3 |

| Hayes29 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 4 | 54 | 52 | 71 | 8 (11) | 11.3 |

| Kolar30 | 2017 | Retro | IFX | 0 | NA | 46 | 26 | 3 (12) | 13.0 |

| Kronsten31 | 2021 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 65 | 52 | 74 | 5 (7) | 6.8 |

| Petitdidier32 | 2020 | Retro | IFX | 30 | 69 | 54 | 118 | 37 (31) | 30.2 |

| Pouillon33 | 2019 | Retro | IFX | 13 | 43 | 282 | 105 | 26 (25) | 4.6 |

| Russo34 | 2008 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 50 | 65 | 31 | 3 (10) | 7.7 |

| Teisner35 | 2010 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 67 | 96 | 12 | 5 (52) | 22.6 |

| Tursi36 | 2010 | Pros | IFX | 0 | 100 | 83 | 23 | 2 (9) | 5.4 |

| Tursi37 | 2021 | Retro | IFX | NA | 33 | 209 | 172 | 9 (5) | 1.3 |

| Viola38 | 2019 | Retro | IFX | 100 | 12 | 52 | 59 | 1 (2) | 1.7 |

| Yamada39 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 49 | 156 | 24 | 1 (4) | 1.4 |

| Baert40 | 2014 | Retro | ADA | 100 | 21 | 52 | 55 | 16 (29) | 29.1 |

| Balint41 | 2015 | Pros | ADA | 67 | 52 | 52 | 55 | 4 (7) | 7.3 |

| Barberio24 | 2020 | Retro | ADA | 58 | 23 | 52 | 30 | 8 (27) | 26.7 |

| Bertani25 | 2020 | Pros | ADA | NA | 0 | 48 | 20 | 8 (40) | 43.3 |

| Christensen42 | 2015 | Retro | ADA | 100 | 27 | 52 | 21 | 2 (10) | 9.5 |

| Gies28 | 2010 | Pros | ADA | 0 | 37 | 60 | 20 | 6 (30) | 26.0 |

| Kamat43 | 2019 | Retro | ADA | 10 | 71 | 52 | 13 | 4 (31) | 30.8 |

| Kronsten31 | 2021 | Retro | ADA | 0 | 54 | 52 | 48 | 6 (13) | 12.5 |

| Kumei44 | 2021 | Pros | ADA | 14 | 37 | 52 | 23 | 3 (13) | 13.0 |

| Macaluso45 | 2021 | Pros | ADA | 34 | NA | 38 | 32 | 3 (9) | 12.8 |

| McDermott46 | 2012 | Retro | ADA | 87 | NA | 96 | 17 | 8 (47) | 25.5 |

| Oh47 | 2020 | Retro | ADA | 44 | 68 | 74 | 92 | 30 (33) | 22.9 |

| Pouillon33 | 2019 | Retro | ADA | 13 | 43 | 282 | 25 | 10 (40) | 7.4 |

| Tursi48 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 41 | 11 | 78 | 102 | 8 (8) | 5.2 |

| Tursi37 | 2021 | Retro | ADA | NA | 17 | 209 | 111 | 2 (2) | 0.4 |

| Van de Vondel11 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 63 | 32 | 177 | 101 | 5 (5) | 0.6 |

| Loss of response defined as treatment optimization | |||||||||

| Alzafiri49 | 2011 | Retro | IFX | 4 | 81 | 62 | 19 | 10 (53) | 44.1 |

| Arias50 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 48 | 245 | 184 | 113 (61) | 13.0 |

| Endo51 | 2016 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 53 | 107 | 27 | 8 (30) | 14.4 |

| Nishida52 | 2017 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 46 | 83 | 37 | 14 (38) | 23.7 |

| Otsuka59 | 2018 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 44 | 52 | 17 | 4 (24) | 23.5 |

| Renna53 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 50 | 11 | 40 | 93 | 50 (54) | 69.9 |

| Taxonera54 | 2017 | Retro | ADA | 58 | 55 | 100 | 184 | 91 (50) | 25.7 |

| Zacharias55 | 2017 | Retro | ADA | 39 | 67 | 55 | 36 | 18 (50) | 47.3 |

| Loss of response defined as increase of disease activity | |||||||||

| Juliao56 | 2013 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 71 | 52 | 21 | 4 (19) | 19.0 |

| Ma57 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 65 | 159 | 66 | 39 (59) | 19.3 |

| Ma57 | 2015 | Retro | ADA | 0 | 65 | 159 | 36 | 21 (58) | 19.1 |

| Sugimoto58 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 19 | 67 | 350 | 14 | 6 (43) | 6.4 |

*Treatment optimization is defined as dose escalation or a combination of dose escalation and treatment switch and/or medical rescue therapy and/or surgery because of LOR. Increase of disease activity is defined as increase of disease scores (eg, partial Mayo score), physician’s global assessment and/or increased C-reactive protein (according to provided standards) and/or endoscopic disease worsening (according to given provided standards or scores).

Abbreviations: ADA, adalimumab; IFX, infliximab; IM, immunomodulator including thiopurines and methotrexate; LOR, loss of response; NA, not available; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis of dose escalation during infliximab or adalimumab treatment

| Study | Year | Design | Anti-TNF | Prior Anti-TNF Use, in % |

Conco-mitant IM Use in % | Follow-up, in Weeks | Pre-DE Group, n | DE N (%) |

Annual DE rate, % | Responsive to DE, n (%) | DE Strategy | Median Time to Escalation, in Weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzafiri49 | 2011 | Retro | IFX | 4 | 81 | 62 | 19 | 8 (42) | 35.3 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Arias50 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 48 | 245 | 184 | 91 (50) | 10.5 | Overcoming clinical relapse: 46 (51) | DI to 10mg/kg: 14 IS 6 weeks: 28; IS 4 weeks: 11 Both IS and DI: 38 |

28 (IQR 15- 48) |

| Armuzzi60 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 56 | 180 | 96 | 15 (16) | 4.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Balint61 | 2018 | Pros | IFX | 7 | 43 | 54 | 73† | 20 (27) | 26.4 | NA | DI to 10 mg/kg | 12 (IQR 4-27) |

| Barberio24 | 2020 | Retro | IFX | 10 | 15 | 52 | 60 | 17 (28) | 28.3 | NA | IS to 6 or 4 weeks | NA |

| Barreiro-de Acosta62 | 2009 | Pros | IFX | 0 | 65 | 104 | 13 | 6 (46) | 23.1 | Deep remission: 3 (50) | IS to 6 weeks | NA |

| Cesarini69 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 2 | 46 | NA | NA | 41 | NA | C-Response at next infusion: 37 (93%); C-Remission week 52: 28 (68) |

DI to 10mg/kg: 15 IS: 26 (4-6 weeks) |

126 (range 17-413) |

| Dumitrescu70 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | NA | 40 | NA | NA | 113 | NA | Week8: C-Response: 61 (54) C-Remission: 10 (11) Week 24: C-Response: 45 (40) C-Remission: 16 (14) |

DI 10 mg/kg | 31 (IQR 16-68) |

| Fernandez26 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 77 | 160 | 187† | 78 (42) | 13.6 | NA | DI: 47 IS: 9 Both: 13 |

NA |

| García-Bosch27 | 2016 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 85 | 302 | 40 | 10 (25) | 4.3 | C-Response: 9 (90) | DI 10 mg/kg IS to 6 or 4 weeks |

29 (IQR 24-60) |

| Gies28 | 2010 | Pros | IFX | 0 | 37 | 60 | 18 | 7 (39) | 33.7 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Juliao56 | 2013 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 71 | 119 | 28† | 4 (14) | 6.2 | C-Response: 4 (100) | IS to 6 weeks | NA |

| Kronsten31 | 2021 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 65 | 52 | 78† | 10 (13) | 12.8 | No discontinuation: 6 (60) | DI or IS | 35 (IQR 22-48) |

| Llao63 | 2016 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 80 | 136 | 15 | 8 (53) | 20.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ma57 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 65 | 159 | 66 | 36 (55) | 17.8 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Otsuka59 | 2018 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 44 | 52 | 17 | 4 (24) | 23.5 | C-Response: 3 (75) | IS 6 weeks | NA |

| Oussalah64 | 2010 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 67 | 78 | 80 | 36 (45) | 30.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pouillon33 | 2019 | Retro | IFX | 6 | 43 | 282 | 140‡ | 77 (55) | 10.1 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Rostholder65 | 2011 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 38 | 52 | 50 | 27 (54) | 54.0 | 5 | DI or IS | NA |

| Taxonera12 | 2015 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 77 | NA | NA | 79 | NA | C-Response week 12: 54 (68) C-Remission week 12: 41 (52) Sustained Clinical benefit: 46 (58) |

DI: 30 IS to 4 weeks: 21 IS to 6 weeks: 28 |

NA |

| Tursi66 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | NA | 182 | 110 | 3 (3) | 0.8 | Remission: 3 (100) | DI 10mg/kg: 1 IS to 4 weeks: 1 Both: 1 |

NA |

| Tursi37 | 2021 | Retro | IFX | NA | 33 | 208 | 184† | 9 (5) | 1.2 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Viola38 | 2019 | Retro | IFX | 100 | 12 | 52 | 53 | 26 (49) | 49.1 | NA | IS: 11 DI: 5 Both: 10 |

NA |

| Yamada39 | 2014 | Retro | IFX | 0 | 49 | 156 | 24 | 17 (71) | 23.6 | C-Remission: 16 (94) | DI: 2 IS: 8 Both: 7 |

NA |

| Baert40 | 2014 | Retro | ADA | 100 | 21 | 52 | 61 | 22 (36) | 36.1 | NA | NA | 12 |

| Balint41 | 2015 | Pros | ADA | 67 | 52 | 52 | 73 | 13 (18) | 17.8 | NA | IS | NA |

| Barberio24 | 2020 | Retro | ADA | 58 | 23 | 52 | 30 | 11 (37) | 36.7 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Gies28 | 2010 | Pros | ADA | 0 | 37 | 60 | 20 | 8 (40) | 34.7 | NA | IS | NA |

| Iborra67 | 2016 | Retro | ADA | 67 | 46 | 52 | 258† | 93 (36) | 36.0 | NA | NA | 21 |

| Kronsten31 | 2021 | Retro | ADA | 0 | 54 | 52 | 63 | 16 (25) | 25.4 | No discontinuation: 7 (44) | DI or IS | 24 (IQR 17-42) |

| Ma57 | 2015 | Retro | ADA | 0 | 65 | 139 | 36 | 18 (50) | 18.7 | NA | DI of IS | NA |

| Oh47 | 2020 | Retro | ADA | 44 | 68 | 74 | 92 | 37 (40) | 28.3 | NA | IS | 28 (IQR 14-59) |

| Pouillon33 | 2019 | Retro | ADA | 35 | 43 | 282 | 63‡ | 38 (60) | 11.1 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Renna53 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 50 | 11 | 40 | 93 | 50 (54) | 69.9 | “Clinical benefit”: 23 (46) | IS | NA |

| Taxonera54 | 2017 | Retro | ADA | 58 | 55 | 100 | 184 | 76 (41) | 21.5 | C-Response: 36 (47) C-Remission: 15 (20) |

IS: 72 DI: 4 |

17 (IQR 9-39) |

| Taxonera68 | 2010 | Retro | ADA | 100 | 50 | 48 | 23 | 4 (17) | 18.8 | NA | IS | NA |

| Tursi48 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 41 | 11 | 78 | 56 | 9 (16) | 10.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| Tursi37 | 2021 | Retro | ADA | NA | 17 | 208 | 118† | 6 (5) | 1.4 | NA | DI or IS | NA |

| Van de Vondel11 | 2018 | Retro | ADA | 63 | 32 | 177 | 196§ | 129 (66) | 19.3 | Two PGA ≥13 weeks apart: 77 (60) | IS | 12 (IQR 7-22) |

| Zacharias55 | 2017 | Retro | ADA | 39 | 67 | 55 | 36 | 8 (22) | 21.0 | Continuation of therapy: 5 (63) | IS | NA |

†Including both primary responders and primary nonresponders.

‡Patients were included in the study if they have received at least 6 months of treatment with infliximab or adalimumab.

§Patients with early discontinuation were excluded, yet dose escalation occurred within time needed to assess primary response and may therefore also include partial responders or primary nonresponders.

Abbreviations: ADA, adalimumab; C-Response, clinical response; C-Remission, clinical remission; DE, dose escalation; DI, dose intensification; IFX, infliximab; IM, immunomodulator including thiopurine and methotrexate; IQR, interquartile range; IS, interval shortening; NA, not available; PGA, physician global assessment; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Annual Loss of Response to Infliximab

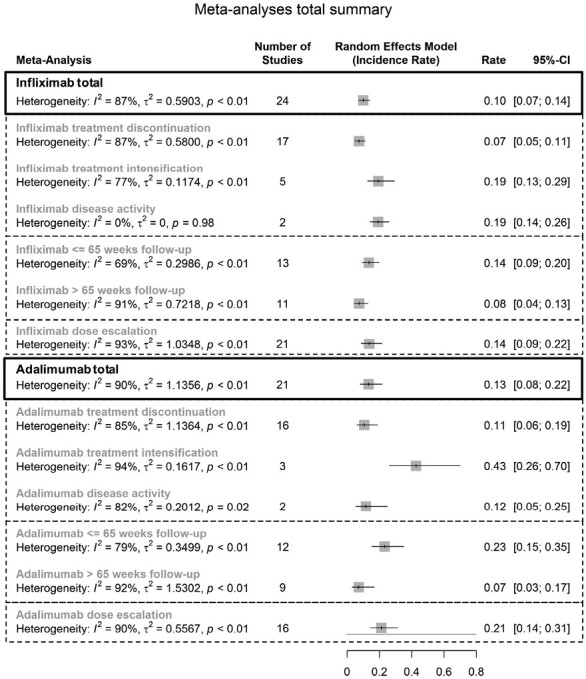

Twenty-four cohort studies were included in the meta-analysis to assess annual LOR to infliximab maintenance treatment.23–39,49–52,56,57,59 These studies collectively included 1591 primary responders and provided a total of 4075 patient-years of follow-up. Follow-up ranged from 46 weeks to 302 weeks. Only 1 study included >50% of patients with prior anti-TNF exposure. A wide variety of definitions (n = 10) was used to define LOR (Supplementary Table 5). Overall, estimates of the annual LOR rates to IFX ranged from 1.3% to 43.5%, and the pooled annual LOR rate to IFX was 10.1% (95% CI, 7.1-14.3; I2 = 86.6%; Figures 1 and 2). Subgroup analysis showed a random effects summary of 13.6% annual LOR (95% CI, 9.3-19.9; I2 = 69.1%) for studies with a follow-up of ≤65 weeks (n = 13) and 7.6% (95% CI, 4.4-13.1; I2 = 90.7%) for studies with a follow-up >65 weeks (n = 11; Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis resulted in incidence rates ranging from 9.5%49 to 11.3%,37 indicating low outlier influences (Supplementary Table 6).

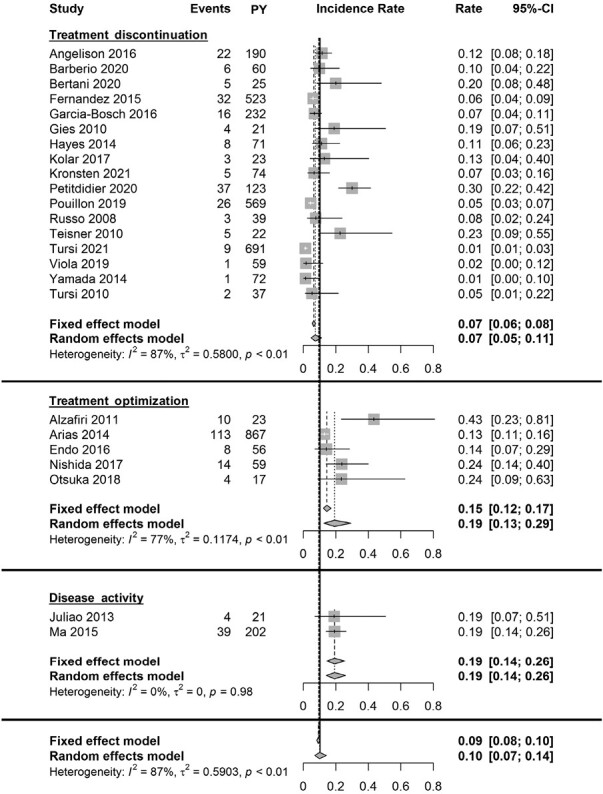

Figure 1.

Forest plot of annual incidence rates of loss of response to infliximab maintenance therapy. Annual incidence rates are plotted per LOR definition group and combined. Abbreviation: PY, patient-years.

Figure 2.

Summary of all meta-analyses’ random effects models.

Loss of response based on treatment discontinuation

Seventeen studies were included for the meta-analysis (Figures 1 and 2).23–35,37–39 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 7.5% (95% CI, 4.9-11.4; I2 = 87.1%). Subgroup analysis showed a random-effects summary of 11.4% annual LOR (95% CI, 7.5-17.2; I2 = 70.1%) for studies with a follow-up ≤65 weeks (n = 10), and 4.5% annual LOR (95% CI, 2.4-8.4; I2 = 81.5%) for studies with a follow-up >65 weeks (n = 7).

Loss of response based on treatment optimization

Five studies were included for the meta-analysis (Figures 1 and 2).49–52,59 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 19.4% (95% CI, 12.7-29.4; I2 = 76.9%). Subgroup analysis showed a random-effects summary of 35.0% annual LOR (95% CI, 20.7-59.1; I2 = 7.2%) for studies with follow-up ≤65 weeks (n = 2), and 13.7% annual LOR (95% CI, 11.6-16.3; I2 = 55.3%) for studies with follow-up >65 weeks follow-up (n = 3).

Loss of response based on increase of disease activity

Two studies were included for the meta-analysis (Figures 1 and 2).56,57 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 19.3% (95% CI, 14.3-26.0; I2 = 0%).

Annual Loss of Response to Adalimumab

A total of 21 studies included 1128 UC patients with primary response to ADA that were treated for 2219 patient-years of follow-up.11,24,25,28,31,33,37,40–48,53–55,57,58 Follow-up ranged from 40 weeks to 350 weeks. Seven studies included >50% of patients with prior anti-TNF exposure. A wide variety of definitions (N = 8) was used to define LOR (Supplementary Table 5). Overall, estimates of the annual LOR rates to ADA ranged from 0.4% to 69.9%, and the pooled annual LOR rate to ADA was 13.4% (95% CI, 8.2-21.8; I2 = 89.8%; Figures 2 and 3). Subgroup analysis showed a random effects summary of 23.3% annual LOR (95% CI, 15.4-35.1; I2 = 78.6%) for studies with a follow-up of ≤65 weeks (n = 12), and 7.2% (95% CI, 3.1-16.8; I2 = 92.0%) for studies with a follow-up >65 weeks (n = 9; Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 4). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis resulted in incidence rates ranging from 12.253 to 15.9,37 indicating low outlier influences (Supplementary Table 7).

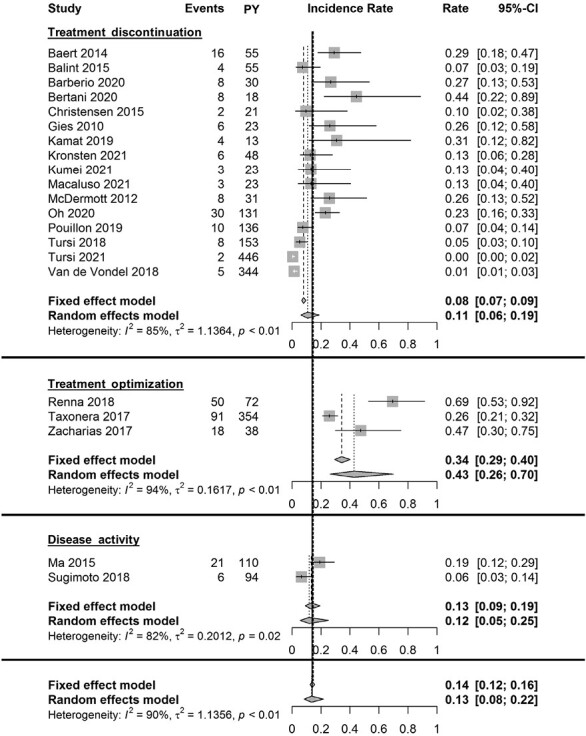

Figure 3.

Forest plot of annual incidence rates of loss of response to adalimumab maintenance therapy. Annual incidence rates are plotted per LOR definition group and combined. Abbreviation: PY, patient-years.

Loss of response based on treatment discontinuation

Sixteen studies were included in the meta-analysis (Figures 2 and 3).11,24,25,28,31,33,37,40–48 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 10.7% (95% CI, 6.1-18.9; I2 = 84.8%). Subgroup analysis showed a random-effect summary of 18.8% annual LOR (95% CI, 13.2-26.9; I2 = 43.6%) for studies with a follow-up ≤65 weeks (n = 10), and 5.0% annual LOR (95% CI, 1.6-15.5; I2 = 92.7%) for studies with a follow-up >65 weeks (n = 6).

Loss of response based on treatment optimization

Three studies were included for the meta-analysis (Figures 2 and 3).53–55 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 42.8% (95% CI, 26.1-70.0; I2 = 93.9%).

Loss of response based on increase of disease activity

Two studies were included for the meta-analysis (Figures 2 and 3).57,58 The random-effects summary showed an annual LOR of 11.7% (95% CI, 5.5-25.1; I2 = 82.1%).

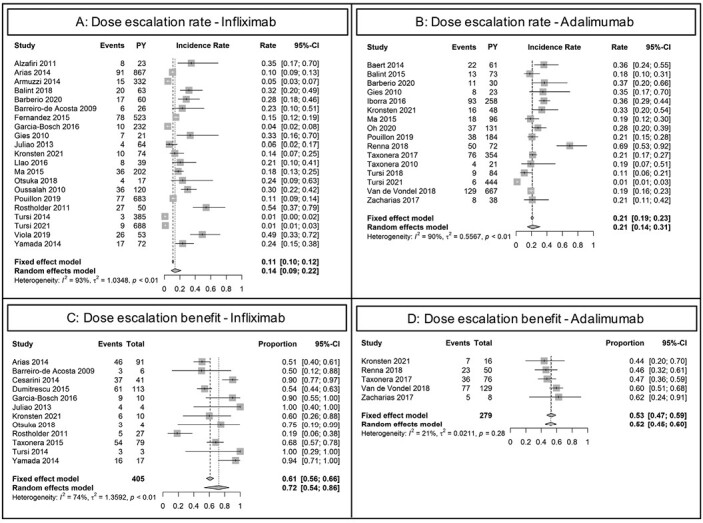

Infliximab Dose Escalation Incidence Rates and Regaining Therapeutic Effect

Twenty-one studies were included for the meta-analysis of annual dose escalation rates during IFX use (Figure 2 and Figure 4A; Table 2).24,26–28,31,33,37–39,49,50,56,57,59–66 Dose escalation strategies were reported in 19 studies. Four studies solely performed either interval shortening or increase of dosage, whereas in 15 studies, both strategies were used. Follow-up ranged from 52 weeks to 302 weeks. Only 1 study included >50% of patients with prior anti-TNF exposure. Random-effects summary showed an annual dose escalation rate of 13.8% (95% CI, 8.7-21.7; I2 = 92.6%). Reported time to dose escalation medians ranged from 12 to 126 weeks (n = 6). Subgroup analysis showed a random-effects summary annual dose escalation rate of 31.8% (95% CI, 23.5-43.2; I2 = 62.4%) for studies with ≤65 weeks follow-up (n = 8), and 8.5% (95% CI, 4.8-15.2; I2 = 91.8%) for studies with >65 weeks follow-up (n = 13). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis resulted in incidence rates ranging from 12.8%65 to 15.7%,66 indicating low outlier influences (Supplementary Table 8). Pooled effectiveness of dose escalation as reported by the authors was 72.4% (95% CI, 53.7-85.6; I2 = 73.8%; n = 12; Figure 4C).12,27,31,39,50,56,59,62,65,66,69,70

Figure 4.

Forest plot of annual incidence rates of dose escalation and subsequential clinical benefit. A, Dose escalations during infliximab maintenance therapy. B, Dose escalations during adalimumab maintenance therapy. C, Proportion of patients regaining clinical remission, clinical response, or continued use following dose escalation for loss of response during infliximab maintenance treatment. D, Proportion of patients regaining clinical remission, clinical response, or continued use following dose escalation for loss of response during adalimumab maintenance treatment. Abbreviation: PY, patient-years.

Adalimumab Dose Escalation Incidence Rates and Regaining Therapeutic Effect

Sixteen studies were included for the meta-analysis of annual dose escalation rates during ADA use (Figure 2 and Figure 4B; Table 2).11,24,28,31,33,37,40,41,47,48,53–55,57,67,68 Random-effects summary showed an annual dose escalation rate of 21.3% (95% CI, 14.4-31.3; I2 = 89.6%). Reported time to dose escalation medians ranged from 12 to 28 weeks (n = 6). Subgroup analysis showed a random-effects summary annual dose escalation rate of 32.7% (95% CI, 24.5-43.5]. I2 = 74.2%) for studies with ≤65 weeks of follow-up (n = 9), and 13.4% (95% CI, 6.8-26.3; I2 = 88.4%) for studies with >65 weeks of follow-up (n = 7). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis resulted in incidence rates ranging from 19.6%53 to 25.8%,37 indicating low outlier influences (Supplementary Table 9). Pooled effectiveness of dose escalation as reported by the authors was achieved in 52.3% (95% CI, 45.0-59.6; I2 = 21.2%; n = 5; Figure 4D).11,31,53–55

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses, including exploration of LOR predictors, could not reliably be performed for the following parameters: use of therapeutic drug monitoring, extent of disease, concomitant mesalamine or immunomodulator use, prior anti-TNF agent exposure, trough levels, and antidrug antibody presence. These features were only described for the total study population including primary nonresponders and not specifically for patients experiencing LOR. There were insufficient prospective studies for solid stratification for study design. We decided not to perform meta regression analyses given the lack of reliable and complete data per included study.

Risk of Bias

The ROBINS-I tool was used for all included studies. The overall risk of bias was low, moderate, serious, and critical in 4%, 24%, 62%, and 10%, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). Visual inspection of funnel plots suggested a higher annual incidence of LOR and (to some extent) dose escalations in larger studies (ie, studies with more patient-years of follow-up; Supplementary Figures 5-6).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we addressed the incidence rates of annual LOR and dose escalation during IFX and ADA treatment for UC. We found an overall pooled annual LOR of 10% for IFX and 13% for ADA. The annual LOR defined as treatment discontinuation was lower compared with treatment optimization (8% vs 19% for IFX and 11% vs 43% for ADA, respectively). In subgroup analyses, LOR rates were higher in studies with shorter follow-up (≤65 weeks) compared with studies with longer follow-up. Annual dose escalation rates were 14% for IFX and 21% for ADA; therapeutic effect was regained in the majority of cases. Definitions of primary response, LOR, successful dose escalation, and follow-up varied markedly among included studies.

As follow-up time varies largely between studies, we used the incidence rate per patient-year as an approximation of LOR. Recently, a large retrospective cohort study reported an LOR to anti-TNF for UC of 9% per patient-year, based on discontinuation due to disease activity, after a median of 2.4 years.9 The authors reported a gradual decrease in annual LOR over time, which is in line with our findings and could explain the higher overall LOR incidence in our study due to inclusion of studies with shorter follow-up. In the first year of treatment, the authors described an annual LOR of 30% for UC. This is significantly higher than the rates we found for LOR due to discontinuation for either IFX (14%) or ADA (23%) during the first 65 weeks of treatment. However, the authors only included a time frame of 8 months following 4 months of induction in the first year. Therefore, it is difficult to compare these LOR rates. It is likely that most causes for LOR, such as immunogenicity or loss of sensitivity to the mechanism of anti-TNF, occur relatively early given the predisposed susceptibility of this group of patients. The annual LOR for IFX and ADA may be different between Crohn’s disease and UC. As a comparison, in Crohn’s disease overall annual LOR rates to IFX and ADA in patients are 13%-18% and 23%-25%, respectively.6–8 In these studies, LOR was most often based on increase of clinical symptoms, which is expected to lead to higher LOR rates compared with discontinuation or treatment optimization used in our study.71,72 Moreover, the authors did not adjust for the follow-up time per individual study but reported the total LOR events in the total follow-up time of all studies. Two recent large retrospective studies suggested that the annual LOR risk to anti-TNF is higher in UC patients compared with Crohn’s disease patients.9,73

Dose escalation may be used as a proxy of LOR and can be used to recapture response following LOR. Yet, dose escalation may also be performed to achieve desired trough levels in absence of disease activity. Although current guidelines only recommend reactive therapeutic drug monitoring and we have excluded studies primarily focusing on proactive drug monitoring, dose escalation rates may overestimate the true LOR rate to a small extent, as proactive dose escalations cannot be ruled out completely.74 Similar to the LOR rates, the annual dose escalation rate was higher in studies reporting shorter follow-up time compared with studies with a longer follow-up. The need for dose escalation seems to be higher during the early phases of IFX and ADA treatment. In a previous systematic review, cumulative dose escalation rates after primary response were 15%-37% for IFX and 18-55% for ADA use.13 However, these rates were not adjusted for follow-up time and are therefore difficult to interpret. In Crohn’s disease, annual dose escalation rates (15% for IFX, 26% for ADA) were similar to our rates.8

Clinical benefit after dose escalation of IFX and ADA was observed in the majority of patients. However, similar to studies in Crohn’s disease, there is a large variation in regained clinical response and remission rates between studies.75 Dose escalation outcomes are subject to used definitions for success. Most studies evaluated success based on short-term clinical parameters without using objective, long-term biochemical and endoscopic measurements following dose escalation. Moreover, dose escalations were not performed in a standardized manner and therefore lead to potential selection bias. It should also be noted that a proportion of dose escalations are performed for dose optimization in (partial) responders. Another proportion may have lost sensitivity to this mechanism and may eventually require a biological agent with a different mechanism of action.

Because the total LOR rate was higher in the first year of treatment (≤65 weeks), physicians should be more aware of signs of LOR during the first year of anti-TNF treatment and consider concomitant immunomodulator therapy, especially for IFX.76 Patients should be informed on the higher risk of LOR during the early stages of therapy, and timely assessment of disease activity may be crucial to prevent a severe disease relapse. It is important to consider predictors that may identify patients at higher risk for LOR for improvement of therapy determination. For example, the HLA-DQA1*05 allele is associated with the development of antidrug antibody formation and consequently LOR.77

It is important to report a uniform definition of primary response and LOR and work towards implementing these uniform definitions in clinical practice. This will enable physicians and researchers to gain more insight in the magnitude of LOR to medical therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), establish predictors related to LOR, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions following LOR. First, there is large variation in definitions used for LOR, which substantially impacts the number of patients classified as LOR. Loss of response may be defined as increase of clinical symptoms based on a variety of clinical indices that cannot be compared reliably. Moreover, increase of clinical disease scores may not always indicate clinically relevant LOR and may also not be related to the underlying IBD.71 The use of more reliable outcome measures such as (combinations of) biomarkers (eg, fecal calprotectin), endoscopic assessment, treatment optimization (either dose escalation or initiation of steroids), or treatment discontinuation may be more appropriate and applicable.4,7,78 Second, as the LOR risk does not seem to be linear over time, varying follow-up time among studies reporting LOR hamper the ability to compare LOR rates.9 Loss of response rates are best reported at predefined time points using a survival curve that adjusts for drop-outs.

Strengths of our study include the extensive literature search and robust methodology. We stratified LOR according to different definitions and showed the impact of these definitions on the LOR rates. Limitations include the substantial heterogeneity among the included studies. Our findings on annual LOR in UC patients on IFX and ADA are based on different used definitions of LOR and follow-up in literature and should therefore be interpreted carefully. In order to adjust for varying follow-up times, we calculated the annual LOR and dose escalation rates per study. We recognize that this approach also has downsides including the expected nonlinear LOR and dose escalation risk over time. In addition, studies with a longer follow-up were consequently weighted more heavily compared with studies with a short follow-up. Annual LOR and dose escalation are therefore only an approximation of the “true” rates. In order to account for the expected nonlinear time relation, we performed a subgroup analysis for studies with a comparable follow-up time (≤65 weeks). We would have preferred to use individual data such as concomitant immunomodulator use for separation and prediction of LOR, but unfortunately these data were only available at an aggregate level in the majority of studies. Similarly, separate use of the definitions for response or remission was not feasible. No endoscopic data were available for further analysis. We did not compare LOR, dose escalation and dose escalation success rates between IFX and ADA as this was beyond the scope of this study. Lastly, our risk of bias assessment reflected the absence of well-defined outcomes of interest, which further underlines the need for definitions that are widely supported and can be implemented in daily practice.

In conclusion, annual LOR incidence in UC patients was 10% for IFX and 13% for ADA treatment. The annual LOR incidences were higher during the first 65 weeks of treatment for both IFX (14%) and ADA (23%). Dose escalation was performed in 14% (IFX) and 21% (ADA) of UC patients and resulted in clinical benefit in 72% and 52%, respectively. A uniform definition for LOR is warranted to gain more insight on the magnitude of this problem and for future evaluation of clinical interventions.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADA

adalimumab

- Anti-TNF

antitumor necrosis factor alpha

- IBD

inflammatory bowel diseases

- IFX

infliximab

- LOR

loss of response

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Contributor Information

Edo H J Savelkoul, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Pepijn W A Thomas, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Lauranne A A P Derikx, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Nathan den Broeder, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Tessa E H Römkens, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands.

Frank Hoentjen, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; Division of Gastroenterology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

Author Contributions

P.T. and E.S. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, and writing of the original draft. L.D., N.dB., T.R., and F.H. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, supervision, review, and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. No additional writing assistance was used for this manuscript.

Funding

No funding has been received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

P.T., E.S., and N.dB. report no conflicts of interest. L.D. has served as speaker or on advisory boards of Sandoz, Janssen, and Dr Falk. T.R. has served as speaker or consultant for Ferring, Janssen, and Takeda. F.H. has served on as speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Takeda, and has received unrestricted grants from Janssen-Cilag, Abbvie.

Data Availability

Data, analytic methods, and study materials can be requested through contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462-2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2012;142(2):257-65.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, Colombel J-F.. Loss of response to Anti-TNFs: Definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2016;7(1):e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y.. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(9):987-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abbvie. Humira 40 mg/0.4 ml solution for injection in pre-filled pen SmPC. 2021. [published 08 September 2003; last updated 09 June 2021; cited 22 november 2021]; Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7986/smpc#DOCREVISION

- 6. Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L.. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):674-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gisbert JP, Panes J.. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):760-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qiu Y, Chen BL, Mao R, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: loss of response and requirement of anti-TNFα dose intensification in Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(5):535-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schultheiss JPD, Mahmoud R, Louwers JM, et al. Loss of response to anti-TNFα agents depends on treatment duration in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(10):1298-1308. Epub 2021/09/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 2018;390(10114):2779-2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van de Vondel S, Baert F, Reenaers C, et al. Incidence and predictors of success of adalimumab dose escalation and de-escalation in ulcerative colitis: a real-world belgian cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(5):1099-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taxonera C, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Calvo M, et al. Infliximab dose escalation as an effective strategy for managing secondary loss of response in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(10):3075-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gemayel NC, Rizzello E, Atanasov P, Wirth D, Borsi A.. Dose escalation and switching of biologics in ulcerative colitis: a systematic literature review in real-world evidence. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(11):1911-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG.. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-9, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama 2000;283(15):2008-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A.. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2016;355:i4919. Epub 2016/10/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2019;366:l4898. Epub 2019/08/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DerSimonian R, Laird N.. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ, Rücker G.. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res Synth Methods 2019;10(3):476-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG.. Chapter 10: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2. Cochrane 2021. Updated February 2021. Accessed November 22, 2021. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW.. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1(2):112-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Angelison L, Almer S, Eriksson A, et al. Long-term outcome of infliximab treatment in chronic active ulcerative colitis: a Swedish multicentre study of 250 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(4):519-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barberio B, Zingone F, Frazzoni L, et al. Real-life comparison of different anti-tnf biologic therapies for ulcerative colitis treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis. 2021;39(1):16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bertani L, Blandizzi C, Mumolo MG, et al. Fecal calprotectin predicts mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with biological therapies: a prospective study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020;11(5):e00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fernández-Salazar L, Muñoz F, Barrio J, et al. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis: real-life analysis of factors predicting treatment discontinuation due to lack of response or colectomy: ECIA (ACAD Colitis and Infliximab Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(2):186-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. García-Bosch O, Aceituno M, Ordás I, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with infliximab for ulcerative colitis: predictive factors of response-an observational study. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(7):2051-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gies N, Kroeker KI, Wong K, Fedorak RN.. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with adalimumab or infliximab: long-term follow-up of a single-centre cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(4):522-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayes MJ, Stein AC, Sakuraba A.. Comparison of efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity between infliximab mono- versus combination therapy in ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(6):1177-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kolar M, Duricova D, Bortlik M, et al. Infliximab biosimilar (remsima™) in therapy of inflammatory bowel diseases patients: experience from one tertiary inflammatory bowel diseases centre. Dig Dis. 2017;35(1-2):91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kronsten VT, Colwill MJ, Nayeemuddin S, et al. A “real-world” retrospective multi-centre cohort study comparing infliximab and adalimumab for the maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. GastroHep 2021;3:229-235. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petitdidier N, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, et al. Real-world use of therapeutic drug monitoring of CT-P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective observational cohort study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2020;44(4):609-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pouillon L, Baumann C, Rousseau H, et al. Treatment persistence of infliximab versus adalimumab in ulcerative colitis: a 16-year single-center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(5):945-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russo EA, Harris AW, Campbell S, et al. Experience of maintenance infliximab therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis from six centres in England. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Teisner AS, Ainsworth MA, Brynskov J.. Long-term effects and colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis patients treated with infliximab: a Danish single center experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(12):1457-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, et al.. Safety and effectiveness of infliximab for inflammatory bowel diseases in clinical practice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14(1):47-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tursi A, Mocci G, Lorenzetti R, et al. Long-term real-life efficacy and safety of infliximab and adalimumab in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases outpatients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33(5):670-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viola A, Pugliese D, Renna S, et al. Outcome in ulcerative colitis after switch from adalimumab/golimumab to infliximab: a multicenter retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(4):510-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamada S, Yoshino T, Matsuura M, et al. Long-term efficacy of infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis: results from a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:80. Epub 2014/04/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2014;40(11-12):1324-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bálint A, Farkas K, Palatka K, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis refractory to conventional therapy in routine clinical practice. Journal of Crohn’s Colitis 2016;10(1):26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Christensen KR, Steenholdt C, Brynskov J.. Clinical outcome of adalimumab therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab: a Danish single-center cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(8):1018-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kamat N, Kedia S, Ghoshal UC, et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab biosimilar in inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2019;38(1):44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumei S, Sakurai T, So S, et al. Impact of the concomitant use of immunomodulator and a lower week 8 partial mayo score on the persistence of adalimumab in refractory ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2021;60(24):3849-3856. Epub 2021/06/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Macaluso FS, Cappello M, Busacca A, et al. SPOSAB ABP 501: a Sicilian prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with adalimumab biosimilar ABP 501. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(11):3041-3049. Epub 2021/06/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McDermott E, Murphy S, Keegan D, et al.. Efficacy of adalimumab as a long term maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2013;7(2):150-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oh EH, Kim J, Ham N, et al. Long-term outcomes of adalimumab therapy in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis: a hospital-based cohort study. Gut Liver 2020;14(3):347-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tursi A, Elisei W, Faggiani R, et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab to treat outpatient ulcerative colitis: a real-life multicenter, observational study in primary inflammatory bowel disease centers. Medicine (Baltim). 2018;97(34):e11897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alzafiri R, Holcroft CA, Malolepszy P, Cohen A, Szilagyi A.. Infliximab therapy for moderately severe Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a retrospective comparison over 6 years. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2011;4:9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arias MT, Vande Casteele N, Vermeire S, et al. A panel to predict long-term outcome of infliximab therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):531-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Endo K, Onodera M, Shiga H, et al. A comparison of short- and long-term therapeutic outcomes of infliximab- versus tacrolimus-based strategies for steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016;2016:11, Article id:3162595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nishida Y, Hosomi S, Yamagami H, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting loss of response to infliximab in ulcerative colitis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Renna S, Mocciaro F, Ventimiglia M, et al. A real life comparison of the effectiveness of adalimumab and golimumab in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis, supported by propensity score analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(12):1292-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taxonera C, Iglesias E, Muñoz F, et al. Adalimumab maintenance treatment in ulcerative colitis: outcomes by prior anti-TNF use and efficacy of dose escalation. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(2):481-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zacharias P, Damião A, Moraes AC, et al. Adalimumab for ulcerative colitis: results of a Brazilian multicenter observational study. Arq Gastroenterol. 2017;54(4):321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Juliao F, Marquez J, Aristizabal N, et al. Clinical efficacy of infliximab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a Latin American referral population. Digestion. 2013;88(4):222-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ma C, Huang V, Fedorak DK, et al. Outpatient ulcerative colitis primary anti-TNF responders receiving adalimumab or infliximab maintenance therapy have similar rates of secondary loss of response. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(8):675-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sugimoto K, Ikeya K, Kato M, et al. Assessment of long-term efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis: results from a 6-year real-world clinical practice. Dig Dis. 2019;37(1):11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Otsuka T, Ooi M, Tobimatsu K, et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes of infliximab and tacrolimus treatment for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: retrospective observational study. Kobe J Med Sci. 2018;64(4):E140-E148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, Danese S, et al. Long-term combination therapy with infliximab plus azathioprine predicts sustained steroid-free clinical benefit in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(8):1368-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bálint A, Rutka M, Kolar M, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 therapy is effective in maintaining endoscopic remission in ulcerative colitis - results from multicenter observational cohort. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(11):1181-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Barreiro-de Acosta M, Lorenzo A, Mera J, Dominguez-Muñoz JE.. Mucosal healing and steroid-sparing associated with infliximab for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2009;3(4):271-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Llaó J, Naves JE, Ruiz-Cerulla A, et al. Azathioprine or infliximab maintenance therapy in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis responding to a 3-infusion induction regimen of infliximab. Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal al Día 2017;16(1):15-20. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oussalah A, Evesque L, Laharie D, et al. A multicenter experience with infliximab for ulcerative colitis: outcomes and predictors of response, optimization, colectomy, and hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(12):2617-2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rostholder E, Ahmed A, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC.. Outcomes after escalation of infliximab therapy in ambulatory patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2012;35(5):562-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tursi A, Elisei W, Picchio M, et al. Managing ambulatory ulcerative colitis patients with infliximab: a long term follow-up study in primary gastroenterology centers. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25(8):757-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Iborra M, Pérez-Gisbert J, Bosca-Watts MM, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in clinical practice: comparison between anti-tumour necrosis factor-naïve and non-naïve patients. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(7):788-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taxonera C, Estellés J, Fernández-Blanco I, et al. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(3):340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cesarini M, Katsanos K, Papamichael K, et al. Dose optimization is effective in ulcerative colitis patients losing response to infliximab: a collaborative multicentre retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46(2):135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dumitrescu G, Amiot A, Seksik P, et al. The outcome of infliximab dose doubling in 157 patients with ulcerative colitis after loss of response to infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(10):1192-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Falvey JD, Hoskin T, Meijer B, et al. Disease activity assessment in IBD: clinical indices and biomarkers fail to predict endoscopic remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(4):824-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease in the SONIC trial. Gut 2014;63(1):88-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Blesl A, Binder L, Högenauer C, et al. Limited long-term treatment persistence of first anti-TNF therapy in 538 patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a 20-year real-world study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(5):667-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S.. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;153(3):827-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mattoo VY, Basnayake C, Connell WR, et al. Systematic review: efficacy of escalated maintenance anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(3):249-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):392-400.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sazonovs A, Kennedy NA, Moutsianas L, et al. HLA-DQA1*05 carriage associated with development of anti-drug antibodies to infliximab and adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158(1):189-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160(5):1570-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data, analytic methods, and study materials can be requested through contacting the corresponding author.