Abstract

Background

Cardiometabolic health has been worsening among young adults, but the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases is unclear.

Methods and Results

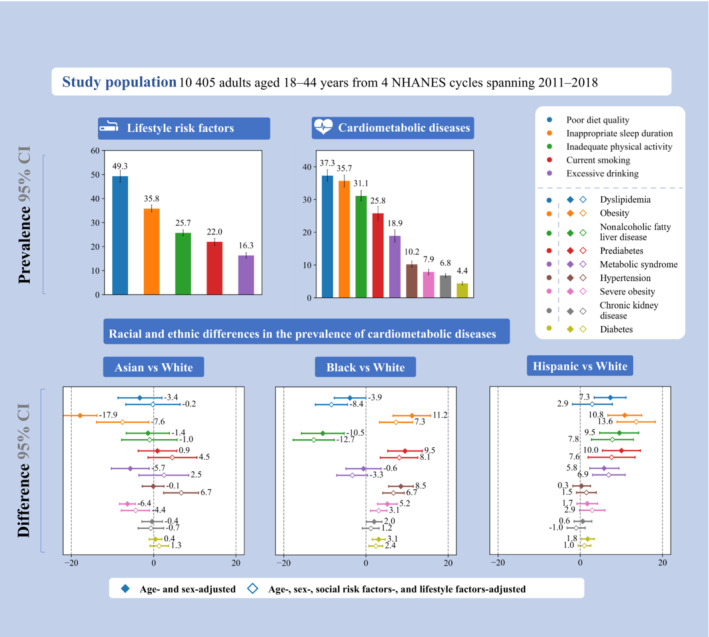

Adults aged 18 to 44 years were included from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011 to 2018. Age‐standardized prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases was estimated overall and by demographic and social risk factors. A set of multivariable logistic regressions was sequentially performed by adjusting for age, sex, social risk factors, and lifestyle factors to determine whether racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases may be attributable to differences in social risk factors and lifestyle factors. Appropriate weights were used to ensure national representativeness of the estimates. A total of 10 405 participants were analyzed (median age, 30.3 years; 50.8% women; 32.3% non‐Hispanic White). The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors ranged from 16.3% for excessive drinking to 49.3% for poor diet quality. The prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases ranged from 4.3% for diabetes to 37.3% for dyslipidemia. The prevalence of having ≥2 lifestyle risk factors was 45.2% and having ≥2 cardiometabolic diseases was 22.0%. Racial and ethnic disparities in many cardiometabolic diseases persisted but were attenuated after adjusting for social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Conclusions

The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases was high among US young adults and varied by race and ethnicity and social risk factors. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases were not fully explained by differences in social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Keywords: cardiometabolic diseases, lifestyle risk factors, prevalence, racial and ethnic disparities, social risk factors

Subject Categories: Lifestyle, Race and Ethnicity, Risk Factors, Epidemiology

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HEI‐2015

Healthy Eating Index‐2015

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

US young adults had poor lifestyle and a high burden of cardiometabolic diseases.

After adjusting for social risk factors and lifestyle factors, racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of many cardiometabolic diseases persisted but were attenuated.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Given that cardiometabolic diseases are largely preventable and lifestyle behaviors are theoretically modifiable, devising effective and targeted interventions to improve cardiometabolic health in young adults would deliver long‐term health benefits.

Cardiometabolic health among middle‐aged and elderly adults has generally improved over the past 2 decades worldwide, but young adults under the age of 45 years have developed increasingly unhealthy cardiometabolic risk profiles. 1 In the United States, the prevalence of obesity, 2 , 3 diabetes, 4 and hypertension 5 , 6 increased substantially among young adults from 1999 to 2018. Also, US young adults do not have ideal health behaviors. For example, diet quality had increased but was still at a very low level in 2017 to 2018. 7 More than half of young adults sat for more than 8 hours a day or were physically inactive in 2015 to 2016. 8 Poor and worsening cardiometabolic health among US young adults calls for immediate public health actions to improve lifestyle behaviors and reduce cardiometabolic disease risk, which are vital for young adults to prevent cardiovascular disease in their later life. 9 , 10

The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases varies substantially by race and ethnicity and social risk factors. 4 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic diseases are substantial and multifactorial and social risk factors are key contributors. 12 Multiple lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases tend to cluster. 16 The aforementioned points have been widely studied in general adult populations, diseased populations, and children, but data are sparse for young adults in general. Young adults have unique characteristics of social risk factors and thus may present unique patterns of racial and ethnic disparities due to a wide range of experiences and continuous changes across many domains of life at this stage, which play an important role in determining cardiometabolic health. 17 However, no study has investigated the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases, individually and in combination, by race and ethnicity and social risk factors among young adults, which prevents us from identifying high‐risk subgroups for early precise prevention of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, it is unclear to what extent racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic diseases among young adults may be attributable to differences in social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2011 to 2018, the objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases overall and by race and ethnicity and social risk factors among US young adults, as well as to determine whether racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases may be attributable to differences in social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

All data and guidance have been made publicly available by the National Center for Health Statistics and can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. NHANES was designed by the National Center for Health Statistics to assess health and nutritional status of noninstitutional civilian residents in the United States. NHANES has been a nationally representative serial cross‐sectional survey based on a complex multistage sampling design. 18 Four NHANES cycles between 2011 to 2012 and 2017 to 2018 were included. Information was collected during the household interview or in mobile examination centers. Data from NHANES have been released in 2‐year cycles since 1999. Personal medical history and medication use were collected by questionnaires. Laboratory data, including fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, serum lipids, urine and serum creatinine, and alanine aminotransferase, were assayed according to standard methods. Participants aged 18 to 44 years who were not pregnant were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Public Health and Nursing Research Ethics Review Committee.

Stratification Variables

Stratification variables included demographic and social risk factors. Demographic variables included age, sex, and race and ethnicity self‐reported based on fixed‐category questions. Social risk factors included education, family income‐to‐poverty ratio, home ownership, employment status, health insurance status, regular health care access assessed by routine place to go for health care, food security status, and country of birth. Food security levels were measured through the US Household Food Security Survey Module. 19

Definition of Lifestyle Risk Factors

Self‐reported lifestyle risk factors included current smoking, excessive drinking, poor diet quality, inadequate physical activity, and inappropriate sleep duration (Table S1). Current smokers reported having smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were currently smoking. Excessive drinkers reported having an average of ≥14 drinks per week for men and ≥7 drinks per week for women or at least 4 or 5 drinks in a single day. 20 Diet quality was assessed by the Healthy Eating Index‐2015 (HEI‐2015), ranging from 0 to 100. 21 There is no established criterion to define poor diet quality. This study defined poor diet quality arbitrarily as having an HEI‐2015 score <50 in primary analysis. Total physical activity included work‐related activity, leisure‐time activity, and transportation activity. Transportation activity was counted as moderate‐intensity activity. 22 The total amount of physical activity was calculated as the minutes of moderate‐intensity activity plus twice the minutes of vigorous‐intensity activity from all 3 domains. Inadequate physical activity was defined as having <150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week. 23 Inappropriate sleep duration was defined as <7 hours or >9 hours of sleep per night for young adults. 24 Clustering of lifestyle risk factors was studied, including having 0, 1, and ≥2 of these 5 lifestyle risk factors.

Definition of Cardiometabolic Diseases

Cardiometabolic diseases included obesity, severe obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, prediabetes, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and metabolic syndrome (Table S1). The 30‐year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was calculated based on the Framingham equation with body mass index included. 25 Fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels were measured among participants who fasted for at least 8 to <24 hours. Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and ≥40 kg/m2 defined obesity and severe obesity, respectively. Dyslipidemia was defined as having a total cholesterol level ≥240 mg/dL, self‐reported current use of lipid‐lowering medications or a high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women. 26 Hypertension was defined as self‐reported current use of antihypertensive medications or blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg. Having a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7% to 6.4% or a fasting plasma glucose level of 100 to 125 mg/dL defined prediabetes among participants who did not report a diabetes diagnosis. Diabetes was defined as having a self‐reported diabetes diagnosis, hemoglobin A1c level of 6.5% or greater or a fasting plasma glucose level of 126 mg/dL or greater. CKD required having a urine albumin to‐creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g or an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. NAFLD was assumed in the presence of serum alanine aminotransferase >30 IU/L for men and>19 IU/L for women and in the absence of excessive drinking and other identifiable causes of liver disease. 27 Metabolic syndrome required meeting at least 3 of the following 5 criteria: waist circumference >102 cm for men or>88 cm for women, a triglycerides level ≥150 mg/dL, a high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level <40 mg/dL for men or<50 mg/dL for women, blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg, and a fasting glucose level ≥100 mg/dL. 28 Clustering of cardiometabolic diseases was studied, including having 0, 1, and ≥2 of dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and NAFLD.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence was defined as the proportion of young adults who had the prespecified lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases. The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases was estimated in the total sample and subgroups by demographic factors: age (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, and 40–44 years), sex (male/female), and race and ethnicity (non‐Hispanic Asian, non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non‐Hispanic White, and other [including other non‐Hispanic ethnicities and mixed races]); and by social risk factors: education (<high school, high school graduate, some college, and ≥college graduate), family income‐to‐poverty ratio (≤100%, >100%–299%, 300%–499%, and ≥500%), home ownership (yes/no), employment status (yes/no), health insurance status (yes/no), regular health care access (yes/no), food security status (secure, marginal, and insecure), and country of birth (United States [born in 50 US states or Washington, DC]/others [born in other countries or US territories]). Results were age‐standardized to the 2017 to 2018 NHANES interview population using the following age groups:18 to 29, 30 to 39, and 40 to 44 years. Weights for the interview sample, examination sample, fasting subsample, and dietary subsample were used appropriately to ensure the estimates were representative of the total civilian noninstitutionalized US young adult population.

A set of multivariable logistic regressions was used to examine whether racial and ethnic differences (comparing other racial and ethnic subgroups to non‐Hispanic White individuals) in the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases may be attributable to demographic factors, social risk factors, and lifestyle factors (for cardiometabolic diseases only). Logistic regression models were sequentially adjusted as follows: model 1 adjusted for age, age squared, and sex; model 2 included variables in model 1 plus all social risk factors mentioned; and for cardiometabolic diseases only, model 3 included variables in model 1 plus lifestyle factors including smoking status (never, former, and current), drinking status (never, former, nonexcessive, and excessive), HEI‐2015 score, HEI‐2015 score squared, physical activity (minutes), physical activity squared, sleep hours, and sleep hours squared; and model 4 adjusted for all social risk factors and lifestyle factors simultaneously in addition to demographic factors. A series of logistic regression models with the same adjustments was additionally performed to evaluate racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of composite outcomes, including having 0, 1, and ≥2 lifestyle risk factors and having 0, 1, and ≥2 of dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and NAFLD.

According to the NHANES analytical guidelines, for analyses with 10% or more missing data, weights were adjusted. 29 Participants were classified into 30 subgroups defined by age (18–29, 30–39, and 40–44 years), sex (male/female), and race and ethnicity (non‐Hispanic White, non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non‐Hispanic Asian, and other). All subgroups had a sample size of at least 30 participants. An adjustment factor was calculated as the sum of the weights for all eligible participants in each subgroup divided by the sum of the weights for those included in the final analyses without missing data. Adjusted weights were calculated through multiplying the original weights by the adjustment factor from each subgroup. Three sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, education attainment was divided into 4 levels to better examine the possible graded relationship between education and the studied outcomes. We assumed that most young adults completed college education before the age of 25 years. Therefore, an additional analysis among adults aged ≥25 years was conducted to assess the robustness of the education‐stratified results from primary analysis. Second, family income‐to‐poverty ratio (9.6% missing data) was removed from multivariable analyses to ensure that missing data did not affect the primary results. Third, due to the absence of an established cutoff to define low diet quality, 2 additional cutoffs, <the 25th percentile of the HEI‐2015 score and an HEI‐2015 score <60, were used. A 2‐sided P<0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were conducted with SAS for Windows version 9.4 and Stata for Windows version 17.0.

Results

A total of 10 405 participants (weighted sample size: 1 0924 6482 participants) were analyzed but specific sample size for each outcome varied (Figures S1 through S3). The weighted median age was 30.3 years (interquartile range, 13.4 years), and 50.8% were women, 32.3% non‐Hispanic White, 22.1% non‐Hispanic Black, 26.2% Hispanic, and 14.7% non‐Hispanic Asian. Of all the variables, income (9.6%) and excessive drinking (10.5%) had the highest percentage of missing data. All other stratification variables and outcomes had a small percentage of missing data (Table S2).

Prevalence of Lifestyle Risk Factors

The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors among US young adults were as follows: current smoking (22.0% [95% CI, 20.4%–23.5%]), excessive drinking (16.3% [95% CI, 15.1%–17.5%]), poor diet quality (49.3% [95% CI, 46.8%–51.9%]), inadequate physical activity (25.7% [95% CI, 24.5%–27.0%]), and inappropriate sleep duration (35.8% [95% CI, 34.3%–37.3%]) (Figure; Table 1; sample sizes in Table S3). The estimated age‐standardized prevalence of lifestyle risk factors varied by demographic and social risk factors. The prevalence of current smoking was significantly higher in non‐Hispanic White individuals than Hispanic and non‐Hispanic Asian individuals (24.8% [95% CI, 22.3%–27.3%] versus 15.7% [95% CI, 13.7%–17.6%] and 10.5% [95% CI, 8.6%–12.4%]). The prevalence of excessive drinking was also significantly higher in non‐Hispanic White individuals than Hispanic and non‐Hispanic Asian individuals (18.5% [95% CI, 16.5%–20.5%] versus 13.1% [95% CI, 11.7%–14.5%] and 6.6% [95% CI, 4.9%–8.3%]). Non‐Hispanic White individuals had a significantly lower prevalence of poor diet quality (50.4% [95% CI, 46.9%–53.9%] versus 56.0% [95% CI, 52.3%–59.8%]), inadequate physical activity (22.1% [95% CI, 20.7%–23.6%] versus 29.6% [95% CI, 27.1%–32.0%]), and inappropriate sleep duration (33.1% [95% CI, 30.9%–35.2%] versus 49.2% [95% CI, 46.9%–51.5%]) than non‐Hispanic Black individuals. Non‐Hispanic Asian individuals had the lowest prevalence of all lifestyle risk factors except for inadequate physical activity. Generally, individuals with a more favorable social risk factor profile (eg, higher education, higher income, higher food security level, and with insurance) had a lower age‐standardized prevalence of lifestyle risk factors.

Figure . Lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic diseases by race and ethnicity and social risk factors among US young adults, 2011 to 2018.

This figure summarizes the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases as well as racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases among young adults, adjusting for age and sex only vs adjusting for age, sex, lifestyle factors, and social risk factors. Definitions for lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases are shown in the footnotes of Tables 1 and 2. Sample sizes are shown in Tables S3 and S4. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. NHANES indicates National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Lifestyle Risk Factors by Demographic Variables and Social Risk Factors*

| Prevalence, % (95% CI)† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Current smoking‡ | Excessive drinking§ | Poor diet quality|| | Inadequate physical activity¶ | Inappropriate sleep duration# |

| Total | 22.0 (20.4–23.5) | 16.3 (15.1–17.5) | 49.3 (46.8–51.9) | 25.7 (24.5–27.0) | 35.8 (34.3–37.3) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 18–24 | 18.5 (16.3–20.8) | 10.2 (8.9–11.5) | 58.3 (54.5–62.2) | 21.0 (18.7–23.3) | 35.9 (33.7–38.1) |

| 25–29 | 23.4 (20.7–26.2) | 17.0 (14.4–19.6) | 50.2 (45.9–54.4) | 21.1 (18.7–23.6) | 33.1 (30.4–35.8) |

| 30–34 | 23.4 (20.9–25.9) | 17.2 (14.6–19.7) | 46.2 (41.9–50.6) | 24.9 (22.0–27.8) | 35.3 (32.6–38.0) |

| 35–39 | 22.7 (20.4–25.0) | 19.7 (17.3–22.1) | 44.3 (40.5–48.1) | 29.2 (26.5–32.0) | 37.7 (34.3–41.1) |

| 40–44 | 22.9 (20.3–25.5) | 20.1 (17.7–22.5) | 42.7 (38.0–47.4) | 34.7 (31.6–37.7) | 37.0 (34.2–39.9) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 24.8 (22.8–26.9) | 20.9 (19.0–22.9) | 52.9 (50.3–55.6) | 19.6 (18.1–21.2) | 37.4 (35.3–39.5) |

| Female | 19.0 (17.3–20.7) | 11.4 (10.0–12.8) | 45.5 (42.3–48.7) | 31.6 (29.8–33.5) | 34.2 (32.5–35.8) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Non‐Hispanic Asian | 10.5 (8.6–12.4) | 6.6 (4.9–8.3) | 33.5 (30.0–37.0) | 33.1 (30.0–36.3) | 28.2 (25.7–30.7) |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 22.7 (20.3–25.2) | 15.2 (13.4–17.0) | 56.0 (52.3–59.8) | 29.6 (27.1–32.0) | 49.2 (46.9–51.5) |

| Hispanic | 15.7 (13.7–17.6) | 13.1 (11.7–14.5) | 46.1 (42.5–49.8) | 30.5 (28.4–32.6) | 37.0 (34.8–39.2) |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 24.8 (22.3–27.3) | 18.5 (16.5–20.5) | 50.4 (46.9–53.9) | 22.1 (20.7–23.6) | 33.1 (30.9–35.2) |

| Other** | 30.2 (25.1–35.3) | 18.7 (13.6–23.8) | 55.9 (47.5–64.3) | 21.8 (16.5–27.0) | 36.5 (31.4–41.5) |

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | 32.9 (29.5–36.4) | 19.0 (16.8–21.2) | 59.0 (55.0–63.0) | 32.6 (30.0–35.2) | 41.5 (38.9–44.2) |

| High school graduate | 30.0 (27.2–32.9) | 19.8 (17.5–22.1) | 60.5 (56.9–64.1) | 27.2 (25.0–29.5) | 39.7 (37.1–42.3) |

| Some college | 23.6 (21.7–25.4) | 17.2 (15.2–19.1) | 52.5 (48.9–56.1) | 24.2 (22.3–26.2) | 39.3 (36.8–41.8) |

| College graduate or higher | 9.0 (7.4–10.6) | 12.0 (9.7–14.3) | 32.4 (28.7–36.2) | 21.4 (19.1–23.7) | 25.0 (22.7–27.3) |

| Family income‐to‐poverty ratio | |||||

| ≤100% | 32.7 (29.1–36.4) | 17.7 (15.5–19.8) | 57.2 (53.2–61.2) | 30.2 (27.5–33.0) | 40.7 (38.5–42.9) |

| >100%–299% | 24.5 (22.5–26.5) | 17.6 (15.9–19.3) | 54.2 (51.3–57.1) | 26.5 (25.0–28.1) | 38.1 (36.1–40.2) |

| ≥300%–499% | 16.0 (13.6–18.3) | 14.3 (11.9–16.7) | 46.7 (42.2–51.3) | 22.9 (20.3–25.4) | 33.0 (29.5–36.5) |

| ≥500% | 12.0 (9.6–14.4) | 14.7 (10.7–18.6) | 37.4 (32.9–42.0) | 21.5 (18.8–24.2) | 28.0 (25.3–30.7) |

| Food security status†† | |||||

| Secure | 17.0 (15.4–18.6) | 14.5 (12.9–16.1) | 45.5 (42.7–48.4) | 24.4 (22.8–26.0) | 32.6 (30.9–34.3) |

| Marginal | 26.7 (23.6–29.7) | 16.7 (14.3–19.2) | 51.9 (47.4–56.3) | 27.6 (24.9–30.3) | 38.6 (35.1–42.2) |

| Insecure | 34.6 (31.8–37.5) | 21.6 (19.2–24.0) | 60.3 (56.4–64.1) | 28.3 (26.0–30.7) | 44.2 (41.2–47.1) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 20.2 (18.7–21.8) | 16.3 (14.8–17.7) | 48.1 (45.3–50.9) | 23.1 (21.7–24.5) | 34.8 (33.0–36.6) |

| Unemployed | 27.4 (24.4–30.5) | 16.4 (14.5–18.3) | 52.6 (49.0–56.1) | 33.0 (30.9–35.1) | 38.4 (36.2–40.5) |

| Home ownership | |||||

| Owned home | 17.4 (15.8–19.1) | 15.2 (13.6–16.8) | 49.0 (45.8–52.2) | 24.7 (22.9–26.4) | 34.3 (32.5–36.1) |

| Did not own home‡‡ | 26.5 (24.0–28.9) | 17.5 (16.0–19.0) | 50.5 (47.5–53.5) | 26.4 (24.8–28.1) | 37.7 (35.6–39.8) |

| Insurance status | |||||

| Insured | 19.1 (17.5–20.7) | 14.5 (13.1–15.9) | 47.1 (44.4–49.9) | 24.4 (23.1–25.6) | 34.9 (33.2–36.6) |

| Uninsured | 31.1 (28.0–34.1) | 21.8 (19.9–23.8) | 56.5 (52.8–60.2) | 29.3 (26.8–31.7) | 38.7 (36.5–40.9) |

| Regular health care access | |||||

| ≥1 Health care facilities | 20.8 (19.2–22.4) | 15.1 (13.8–16.4) | 48.1 (45.3–51.0) | 26.2 (24.7–27.7) | 35.4 (33.6–37.2) |

| None | 25.8 (23.2–28.3) | 19.8 (17.5–22.1) | 52.7 (49.4–55.9) | 23.9 (21.8–26.0) | 37.2 (35.0–39.4) |

| Country of birth | |||||

| United States | 24.3 (22.4–26.2) | 17.8 (16.4–19.2) | 52.5 (49.6–55.3) | 23.8 (22.5–25.0) | 36.8 (35.1–38.5) |

| Other countries | 12.7 (11.4–14.1) | 10.7 (9.3–12.1) | 36.6 (33.2–39.9) | 31.9 (29.8–34.0) | 32.1 (29.7–34.4) |

Please refer to Table S3 for sample sizes. Sample sizes were unweighted.

Estimates for overall and by age groups were unadjusted. Other estimates were age‐standardized to the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey nonpregnant adult population, using the age groups 18 to 29 years, 30 to 39 years, and 40 to 44 years. All estimates were weighted.

Smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were currently smoking.

Having an average of ≥14 drinks per week for men and ≥7 drinks per week for women or at least 4 or 5 drinks in a single day.

Having a Healthy Eating Index 2015 score <50 out of 100.

Having <150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week (including work‐related activity, leisure‐time activity, and transportation activity).

Having <7 hours or >9 hours of sleep per night.

The “other” group included other non‐Hispanic ethnicities and mixed races.

Food security level was measured using the US Household Food Security Survey Module in which 10 questions were used to create 4 response levels: full food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. Low food security and very low food security were combined into the “Insecure” category.

Renting a home or having other arrangements.

Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Diseases

The prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases among US young adults were as follows: obesity (35.7% [95% CI, 33.8%–37.5%]), severe obesity (7.9% [95% CI, 7.0%–8.7%]), dyslipidemia (37.3% [95% CI, 35.6%–39.1%]), hypertension (10.2% [95% CI, 9.3%–11.2%]), prediabetes (25.8% [95% CI, 23.6%–27.9%]), diabetes (4.4% [95% CI, 3.9%–4.9%]), CKD (6.8% [95% CI, 6.2%–7.4%]), NAFLD (31.1% [95% CI, 29.5%–32.8%]), and metabolic syndrome (18.9% [95% CI, 17.0%–20.8%]) (Table 2, sample sizes in Table S4). The estimated age‐standardized prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases varied by demographic and social risk factors. The prevalence of obesity (33.4% [95% CI, 30.8%–35.9%] versus 44.1% [95% CI, 41.7%–46.5%] and 41.6% [95% CI, 39.3%–43.9%]), prediabetes (22.2% [95% CI, 19.2%–25.3%] versus 30.3% [95% CI, 27.1%–33.4%] and 31.4% [95% CI, 28.5%–34.3%]), diabetes (3.4% [95% CI, 2.8%–4.0%] versus 6.1% [95% CI, 4.7%–7.5%] and 5.4% [95% CI, 4.3%–6.5%]), and CKD (5.9% [95% CI, 5.1%–6.8%] versus 8.7% [95% CI, 7.3%–10.2%] and 8.1% [95% CI, 6.7%–9.4%]) was significantly lower in non‐Hispanic White individuals than in non‐Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals. Compared with non‐Hispanic White and Hispanic individuals, non‐Hispanic Black individuals had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension (16.9% [95% CI, 15.2%–18.6%] versus 8.9% [95% CI, 7.7%–10.2%] and 8.1% [95% CI, 6.9%–9.3%]), respectively, but a significantly lower prevalence of dyslipidemia (32.0% [95% CI, 29.9%–34.1%] versus 36.2% [95% CI, 33.7%–38.7%] and 42.7% [95% CI, 40.3%–45.0%]) and NAFLD (20.9% [95% CI, 18.5%–23.3%] versus 30.6% [95% CI, 28.1%–33.0%] and 39.4% [95% CI, 36.5%–42.3%]). Hispanic individuals had the highest prevalence of metabolic syndrome among all racial and ethnic subgroups (23.2% [95% CI, 20.7%–25.8%]). Generally, young adults with a more favorable social risk factor profile had a lower prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Diseases by Demographic Variables and Social Risk Factors*

| Prevalence, % (95% CI)† | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Obesity‡ | Severe obesity‡ | Dyslipidemia§ | Hypertension|| | Prediabetes¶ | Diabetes¶ | CKD# | NAFLD** | Metabolic syndrome†† |

| Total | 35.7 (33.8–37.5) | 7.9 (7.0–8.7) | 37.3 (35.6–39.1) | 10.2 (9.3–11.2) | 25.8 (23.6–27.9) | 4.4 (3.9–4.9) | 6.8 (6.2–7.4) | 31.1 (29.5–32.8) | 18.9 (17.0–20.8) |

| Age group, y | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 26.4 (23.4–29.4) | 5.7 (4.5–7.0) | 31.1 (28.1–34.0) | 2.5 (1.7–3.2) | 17.2 (14.6–19.8) | 1.2 (0.5–1.9) | 7.5 (6.2–8.7) | 24.9 (22.1–27.6) | 8.1 (5.7–10.4) |

| 25–29 | 34.3 (30.4–38.2) | 7.3 (5.9–8.7) | 34.3 (30.8–37.7) | 3.8 (2.7–4.9) | 20.2 (16.5–24.0) | 2.3 (1.3–3.3) | 5.0 (3.4–6.5) | 31.8 (28.5–35.2) | 13.8 (10.1–17.5) |

| 30–34 | 38.7 (35.7–41.8) | 9.5 (7.6–11.5) | 38.8 (36.2–41.4) | 10.8 (8.6–13.1) | 28.0 (23.2–32.9) | 3.3 (2.4–4.2) | 6.0 (4.6–7.5) | 34.7 (31.8–37.6) | 21.4 (18.1–24.8) |

| 35–39 | 39.7 (36.5–42.8) | 8.0 (6.2–9.7) | 40.6 (37.6–43.7) | 16.6 (14.2–18.9) | 31.6 (27.4–35.7) | 6.6 (5.2–8.0) | 7.6 (6.1–9.1) | 33.0 (29.5–36.5) | 23.3 (19.0–27.6) |

| 40–44 | 43.4 (40.2–46.5) | 9.8 (7.9–11.7) | 44.5 (41.5–47.6) | 21.1 (18.2–24.1) | 35.4 (30.2–40.5) | 9.8 (8.0–11.6) | 7.7 (6.3–9.1) | 34.7 (31.3–38.1) | 32.5 (27.8–37.3) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 34.8 (32.3–37.3) | 5.8 (4.9–6.7) | 35.1 (33.2–37.0) | 11.9 (10.4–13.3) | 31.4 (28.4–34.5) | 3.9 (3.1–4.7) | 5.2 (4.4–6.0) | 32.3 (30.3–34.3) | 20.1 (17.7–22.6) |

| Female | 36.4 (34.5–38.2) | 9.9 (8.7–11.1) | 39.4 (37.3–41.5) | 8.1 (7.1–9.1) | 19.3 (17.2–21.4) | 4.6 (3.8–5.4) | 8.4 (7.5–9.4) | 30.2 (28.2–32.1) | 16.9 (14.8–19.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non‐Hispanic Asian | 14.9 (13.0–16.9) | 1.1 (0.6–1.6) | 33.7 (30.6–36.8) | 7.5 (6.1–8.9) | 22.8 (19.3–26.3) | 4.3 (3.0–5.5) | 6.7 (5.1–8.4) | 29.6 (27.1–32.1) | 13.4 (10.5–16.3) |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 44.1 (41.7–46.5) | 12.6 (11.1–14.2) | 32.0 (29.9–34.1) | 16.9 (15.2–18.6) | 30.3 (27.1–33.4) | 6.1 (4.7–7.5) | 8.7 (7.3–10.2) | 20.9 (18.5–23.3) | 16.4 (13.5–19.3) |

| Hispanic | 41.6 (39.3–43.9) | 7.6 (6.4–8.8) | 42.7 (40.3–45.0) | 8.1 (6.9–9.3) | 31.4 (28.5–34.3) | 5.4 (4.3–6.5) | 8.1 (6.7–9.4) | 39.4 (36.5–42.3) | 23.2 (20.7–25.8) |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 33.4 (30.8–35.9) | 7.4 (6.1–8.7) | 36.2 (33.7–38.7) | 8.9 (7.7–10.2) | 22.2 (19.2–25.3) | 3.4 (2.8–4.0) | 5.9 (5.1–6.8) | 30.6 (28.1–33.0) | 17.8 (15.3–20.3) |

| Other‡‡ | 41.6 (35.2–48.1) | 10.7 (7.2–14.2) | 42.7 (37.9–47.6) | 11.4 (7.2–15.5) | 32.6 (24.1–41.1) | 5.8 (3.1–8.4) | 6.6 (4.3–8.8) | 29.0 (23.3–34.8) | 22.3 (14.7–30.0) |

| Education level | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 36.7 (33.7–39.7) | 7.7 (6.1–9.4) | 44.7 (41.6–47.7) | 10.6 (8.9–12.3) | 31.6 (27.6–35.5) | 5.2 (3.9–6.6) | 9.6 (8.0–11.2) | 34.8 (32.2–37.4) | 24.6 (20.9–28.3) |

| High school graduate | 40.8 (38.5–43.2) | 9.1 (7.6–10.6) | 39.7 (36.9–42.4) | 12.4 (10.5–14.3) | 29.8 (25.8–33.7) | 5.2 (4.1–6.4) | 7.2 (5.8–8.7) | 30.8 (27.6–34.0) | 20.4 (17.3–23.4) |

| Some college | 39.9 (38.0–41.9) | 9.7 (8.3–11.0) | 40.4 (37.8–42.9) | 11.5 (9.8–13.2) | 24.1 (20.9–27.3) | 5.2 (4.2–6.2) | 6.7 (5.5–7.9) | 32.3 (30.1–34.5) | 21.6 (18.4–24.8) |

| College graduate or higher | 26.4 (23.1–29.6) | 5.3 (3.8–6.8) | 27.8 (25.5–30.1) | 7.0 (5.6–8.3) | 21.5 (17.7–25.4) | 2.1 (1.4–2.9) | 5.1 (3.9–6.4) | 29.4 (26.1–32.7) | 11.5 (9.0–13.9) |

| Family income‐to‐poverty ratio | |||||||||

| ≤100% | 37.9 (35.2–40.6) | 8.9 (7.6–10.3) | 42.7 (39.3–46.1) | 11.9 (10.2–13.6) | 29.5 (26.3–32.8) | 6.0 (4.7–7.3) | 9.1 (8.0–10.2) | 31.8 (28.7–34.9) | 23.0 (18.9–27.2) |

| >100%–299% | 39.6 (37.3–42.0) | 9.9 (8.5–11.3) | 41.0 (38.6–43.4) | 10.4 (9.2–11.5) | 26.7 (23.6–29.7) | 4.6 (3.6–5.6) | 7.6 (6.6–8.7) | 33.2 (30.8–35.5) | 23.4 (20.6–26.2) |

| ≥300%–499% | 33.8 (30.6–36.9) | 6.4 (4.9–8.0) | 32.9 (29.8–35.9) | 9.3 (7.4–11.1) | 22.2 (18.5–26.0) | 3.8 (2.5–5.1) | 4.4 (3.1–5.7) | 30.6 (26.7–34.5) | 15.1 (11.5–18.6) |

| ≥500% | 29.5 (25.1–33.8) | 5.3 (3.5–7.1) | 29.4 (26.3–32.5) | 8.9 (7.1–10.7) | 21.8 (16.6–27.1) | 2.7 (1.7–3.7) | 5.5 (4.0–7.0) | 31.5 (27.6–35.3) | 10.0 (6.8–13.3) |

| Food security status§§ | |||||||||

| Secure | 31.8 (29.5–34.1) | 6.4 (5.4–7.4) | 33.6 (31.8–35.4) | 8.7 (7.7–9.6) | 23.3 (20.8–25.7) | 3.5 (2.8–4.1) | 5.9 (5.2–6.6) | 30.1 (28.2–32.0) | 14.5 (12.7–16.4) |

| Marginal | 41.0 (37.4–44.6) | 8.7 (6.8–10.5) | 40.2 (36.7–43.7) | 12.4 (10.1–14.8) | 29.6 (25.3–33.8) | 4.6 (3.3–5.8) | 8.4 (6.5–10.3) | 33.7 (29.8–37.7) | 23.1 (18.5–27.7) |

| Insecure | 44.4 (41.6–47.2) | 12.0 (10.3–13.8) | 47.2 (44.4–49.9) | 12.8 (11.1–14.6) | 28.9 (25.2–32.7) | 6.3 (5.2–7.4) | 8.5 (7.0–9.9) | 34.4 (31.3–37.5) | 27.9 (24.0–31.7) |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Employed | 35.3 (33.4–37.2) | 7.3 (6.4–8.2) | 35.1 (33.5–36.8) | 9.4 (8.4–10.4) | 26.2 (23.9–28.5) | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 6.0 (5.2–6.8) | 30.8 (29.1–32.6) | 17.6 (15.8–19.4) |

| Unemployed | 36.4 (33.2–39.5) | 9.7 (8.1–11.2) | 43.6 (40.6–46.6) | 12.1 (10.7–13.4) | 23.2 (20.0–26.4) | 5.6 (4.4–6.7) | 9.2 (8.0–10.3) | 32.5 (29.6–35.5) | 21.5 (18.5–24.5) |

| Home ownership | |||||||||

| Owned home | 33.6 (30.7–36.4) | 7.1 (5.8–8.4) | 35.5 (33.1–37.8) | 9.4 (8.3–10.5) | 23.8 (20.8–26.8) | 3.7 (2.9–4.4) | 6.5 (5.4–7.5) | 30.4 (27.8–33.0) | 16.5 (14.1–18.9) |

| Not owned home|||| | 38.1 (36.1–40.1) | 8.7 (7.5–10.0) | 39.4 (37.2–41.5) | 10.9 (9.6–12.1) | 26.9 (24.3–29.5) | 5.0 (4.3–5.7) | 7.2 (6.3–8.0) | 32.9 (30.9–34.9) | 21.1 (18.5–23.6) |

| Insurance status | |||||||||

| Insured | 35.1 (33.0–37.2) | 7.6 (6.6–8.5) | 35.8 (33.8–37.8) | 10.3 (9.2–11.3) | 23.5 (21.1–25.9) | 4.1 (3.6–4.6) | 6.4 (5.7–7.0) | 30.5 (28.6–32.4) | 17.8 (15.9–19.8) |

| Uninsured | 36.6 (33.7–39.5) | 8.6 (7.1–10.2) | 41.3 (38.7–44.0) | 9.2 (7.6–10.7) | 31.6 (27.8–35.5) | 4.7 (3.6–5.7) | 8.2 (7.0–9.4) | 33.6 (31.3–35.9) | 20.7 (17.9–23.4) |

| Regular health care access | |||||||||

| ≥1 Health care facilities | 36.4 (34.5–38.3) | 8.5 (7.5–9.5) | 37.9 (36.0–39.8) | 10.7 (9.6–11.7) | 24.5 (22.1–26.9) | 4.5 (4.0–5.1) | 6.9 (6.2–7.7) | 31.1 (29.2–32.9) | 19.0 (17.1–21.0) |

| None | 32.1 (29.3–34.8) | 5.6 (4.4–6.7) | 34.9 (32.2–37.7) | 7.6 (6.4–8.7) | 27.6 (24.6–30.7) | 3.4 (2.2–4.5) | 6.3 (5.2–7.4) | 31.2 (28.4–34.1) | 16.6 (14.1–19.1) |

| Country of birth | |||||||||

| United States | 37.8 (35.7–39.8) | 9.1 (8.0–10.1) | 36.4 (34.6–38.3) | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 24.6 (22.1–27.0) | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 6.5 (5.8–7.3) | 30.0 (28.1–31.8) | 19.0 (17.0–21.0) |

| Other countries | 28.0 (25.7–30.4) | 3.6 (2.8–4.4) | 39.9 (37.3–42.5) | 6.2 (5.2–7.2) | 28.9 (25.7–32.0) | 4.7 (3.7–5.6) | 7.6 (6.4–8.9) | 35.9 (32.8–39.0) | 16.9 (14.3–19.6) |

CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; and NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Please refer to Table S4 for sample sizes. Sample sizes were unweighted.

Estimates for overall and by age groups were unadjusted. Other estimates were age‐standardized to the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey nonpregnant adult population, using the age groups 18 to 29 years, 30 to 39 years, and 40 to 44 years. All estimates were weighted.

Obesity was defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. Severe obesity was defined as body mass index ≥40 kg/m2.

Having a total cholesterol level ≥240 mg/dL, self‐reported current use of lipid‐lowering medications, or a high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women.

Blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or self‐reported current use of antihypertensive medications.

Prediabetes was defined as having a hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7–6.4% or a fasting plasma glucose level of 100–125 mg/dL among participants who did not report a diabetes diagnosis. Diabetes was defined as having a self‐reported diabetes diagnosis, a hemoglobin A1c level ≥6.5%, or a fasting plasma glucose level ≥126 mg/dL.

Having a urine albumin‐to‐creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g or an estimated glomerular filtration rate<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Having serum alanine aminotransferase activity >30 IU/L for men and>19 IU/L for women in the absence of excessive drinking and other identifiable causes of liver disease.

Having at least 3 of the following 5 criteria: waist circumference >102 cm for men or >88 cm for women, a triglycerides level ≥150 mg/dL, a high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level <40 mg/dL for men or <50 mg/dL for women, blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg, and a fasting glucose level ≥100 mg/dL.

The “other” group included other non‐Hispanic ethnicities and mixed races.

Food security level was measured using the US Household Food Security Survey Module in which 10 questions were used to create 4 response levels: full food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. Low food security and very low food security were combined into the “Insecure” category.

Renting a home or having other arrangements.

Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors and Cardiometabolic Diseases and 30‐Year ASCVD Risk

The prevalence of having none of the lifestyle risk factors was 20.1% (95% CI, 18.0%–22.1%) and of having ≥2 lifestyle risk factors was 45.2% (95% CI, 43.0%–47.5%) (Table 3, sample sizes in Table S5). The prevalence of having none of the 5 prespecified cardiometabolic diseases (dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and NAFLD) was 39.7% (95% CI, 37.3%–42.1%) and of having ≥2 cardiometabolic diseases was 22.0% (95% CI, 20.4%–23.5%). The 30‐year ASCVD risk was 14.2% (95% CI, 13.6%–14.8%). Non‐Hispanic Black individuals had the highest prevalence of having ≥2 lifestyle risk factors (56.4% [95% CI, 53.1%–59.8%]) among all racial and ethnic subgroups. Compared with non‐Hispanic White individuals, Hispanic individuals had a significantly higher prevalence of having ≥2 cardiometabolic diseases (27.1% [95% CI, 24.1%–30.2%] versus 20.1% [95% CI, 17.8%–22.4%]). Non‐Hispanic Asian individuals had the lowest 30‐year risk of ASCVD among all racial and ethnic subgroups (11.0% [95% CI, 10.4%–11.6%]).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors and Cardiometabolic Diseases by Demographic Variables and Social Risk Factors*

| Characteristics | Prevalence, % (95% CI)† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors‡ | Number of cardiometabolic diseases§ | 30‐Year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease|| | |||||

| 0 | 1 | ≥2 | 0 | 1 | ≥2 | ||

| Total | 20.1 (18.0–22.1) | 33.4 (31.8–34.9) | 45.2 (43.0–47.5) | 39.7 (37.3–42.1) | 32.2 (30.6–33.8) | 22.0 (20.4–23.5) | 14.2 (13.6–14.8) |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| 18–24 | 17.8 (14.8–20.9) | 35.0 (32.1–37.9) | 45.2 (41.3–49.2) | 48.8 (44.5–53.1) | 33.7 (29.9–37.5) | 13.5 (10.7–16.3) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) |

| 25–29 | 22.3 (18.5–26.2) | 33.6 (29.6–37.5) | 43.4 (39.3–47.5) | 43.0 (37.3–48.8) | 33.4 (28.7–38.2) | 17.5 (13.9–21.1) | 8.2 (7.7–8.6) |

| 30–34 | 22.0 (18.4–25.6) | 31.7 (28.4–34.9) | 45.3 (41.1–49.5) | 39.1 (35.1–43.2) | 30.9 (26.4–35.4) | 23.9 (20.9–26.9) | 13.5 (12.8–14.2) |

| 35–39 | 20.8 (16.8–24.8) | 31.5 (28.1–35.0) | 45.8 (41.5–50.2) | 34.2 (29.2–39.2) | 31.1 (26.0–36.3) | 27.1 (23.2–31.0) | 20.4 (19.3–21.4) |

| 40–44 | 18.3 (14.7–21.9) | 34.4 (30.3–38.4) | 46.4 (42.0–50.8) | 29.4 (25.2–33.6) | 31.2 (26.4–36.1) | 32.2 (27.7–36.7) | 28.6 (27.4–29.9) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 18.4 (16.0–20.8) | 33.5 (31.0–35.9) | 47.2 (44.5–50.0) | 41.1 (37.9–44.3) | 30.7 (28.2–33.2) | 21.0 (18.9–23.1) | 16.8 (16.2–17.4) |

| Female | 22.0 (19.4–24.5) | 33.1 (31.3–34.9) | 43.1 (40.1–46.1) | 38.8 (35.9–41.7) | 33.9 (31.4–36.3) | 22.8 (20.7–24.8) | 10.4 (10.0–10.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||

| Non‐Hispanic Asian | 30.7 (25.3–36.1) | 35.2 (31.0–39.5) | 32.3 (27.6–37.0) | 46.1 (41.0–51.1) | 28.5 (23.3–33.7) | 20.9 (16.9–25.0) | 11.0 (10.4–11.6) |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 12.2 (10.0–14.4) | 30.1 (27.3–32.9) | 56.4 (53.1–59.8) | 42.1 (38.2–45.9) | 30.8 (27.2–34.3) | 21.5 (18.5–24.5) | 15.8 (15.2–16.5) |

| Hispanic | 17.8 (15.2–20.3) | 37.4 (34.5–40.3) | 43.4 (40.1–46.7) | 33.6 (30.1–37.1) | 34.8 (31.9–37.6) | 27.1 (24.1–30.2) | 13.6 (13.1–14.1) |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 21.7 (18.8–24.5) | 32.8 (30.2–35.3) | 44.4 (40.9–47.8) | 41.5 (37.9–45.0) | 31.9 (29.4–34.4) | 20.1 (17.8–22.4) | 13.5 (12.9–14.1) |

| Other# | 17.6 (11.3–23.9) | 29.6 (23.5–35.6) | 51.5 (44.7–58.3) | 37.9 (28.5–47.3) | 32.7 (24.4–41.1) | 22.7 (15.3–30.0) | 14.7 (13.0–16.4) |

| Education level | |||||||

| Less than high school | 9.7 (7.7–11.7) | 25.8 (22.0–29.6) | 62.0 (57.3–66.8) | 32.7 (28.4–36.9) | 31.2 (27.2–35.3) | 29.2 (25.7–32.8) | 15.4 (14.6–16.1) |

| High school graduate | 12.2 (9.9–14.5) | 27.1 (24.6–29.6) | 60.0 (56.8–63.2) | 38.1 (34.4–41.8) | 32.6 (28.6–36.7) | 22.3 (19.3–25.4) | 15.8 (15.1–16.6) |

| Some college | 16.5 (13.8–19.2) | 34.7 (32.1–37.3) | 47.5 (44.4–50.7) | 38.1 (34.4–41.8) | 31.6 (28.4–34.8) | 24.0 (21.0–26.9) | 14.2 (13.6–14.8) |

| College graduate or higher | 35.3 (31.8–38.8) | 39.3 (36.1–42.6) | 24.5 (21.4–27.6) | 46.5 (41.3–51.6) | 33.5 (29.1–37.8) | 16.1 (13.5–18.8) | 11.4 (10.9–11.9) |

| Family income‐to‐poverty ratio | |||||||

| ≤100% | 11.5 (9.0–13.9) | 28.6 (25.7–31.5) | 58.4 (54.8–62.1) | 32.9 (28.4–37.3) | 34.1 (30.5–37.8) | 26.9 (23.5–30.2) | 15.2 (14.3–16.2) |

| >100%–299% | 16.8 (14.3–19.3) | 31.6 (29.0–34.1) | 50.4 (47.5–53.2) | 37.6 (33.7–41.6) | 30.4 (27.4–33.3) | 25.5 (23.0–28.0) | 14.6 (14.1–15.2) |

| ≥300%–499% | 23.7 (19.4–27.9) | 37.1 (33.5–40.8) | 38.4 (34.0–42.8) | 45.2 (39.6–50.7) | 31.8 (27.1–36.5) | 17.4 (14.0–20.9) | 13.1 (12.5–13.8) |

| ≥500% | 29.9 (26.2–33.6) | 37.4 (34.0–40.9) | 31.4 (27.2–35.6) | 48.4 (40.9–55.9) | 31.7 (25.1–38.3) | 15.4 (11.7–19.2) | 11.6 (11.0–12.2) |

| Food security status** | |||||||

| Secure | 23.9 (21.2–26.5) | 35.4 (33.4–37.4) | 39.4 (36.7–42.1) | 44.1 (41.1–47.1) | 31.9 (29.4–34.3) | 18.9 (17.0–20.9) | 12.7 (12.3–13.1) |

| Marginal | 15.3 (11.9–18.8) | 32.4 (28.4–36.5) | 50.7 (45.8–55.7) | 34.8 (30.6–39.1) | 32.6 (28.2–37.0) | 25.4 (20.9–29.9) | 14.3 (13.6–15.0) |

| Insecure | 10.6 (8.4–12.8) | 26.7 (23.4–30.0) | 61.6 (57.3–66.0) | 30.7 (26.2–35.3) | 31.6 (27.7–35.4) | 29.8 (26.2–33.5) | 16.3 (15.6–17.1) |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 21.7 (19.2–24.1) | 34.9 (33.0–36.9) | 42.4 (40.1–44.7) | 42.8 (40.1–45.5) | 32.2 (30.0–34.3) | 19.3 (17.8–20.7) | 13.7 (13.4–14.1) |

| Unemployed | 15.5 (12.7–18.3) | 28.9 (26.0–31.8) | 53.5 (49.5–57.6) | 31.7 (28.0–35.4) | 32.8 (29.5–36.0) | 29.3 (26.0–32.6) | 13.7 (12.9–14.5) |

| Home ownership | |||||||

| Owned home | 21.2 (18.7–23.7) | 35.4 (33.2–37.7) | 42.0 (39.0–45.0) | 43.2 (39.6–46.7) | 31.1 (28.2–34.0) | 20.2 (17.8–22.6) | 13.0 (12.5–13.5) |

| Did not own home†† | 18.2 (15.5–21.0) | 31.1 (29.1–33.0) | 49.4 (46.2–52.7) | 36.7 (33.6–39.8) | 32.7 (30.1–35.3) | 24.3 (21.8–26.7) | 14.5 (13.9–15.1) |

| Insurance status | |||||||

| Insured | 22.3 (19.9–24.6) | 35.0 (33.4–36.7) | 41.4 (39.1–43.6) | 41.3 (38.5–44.1) | 32.5 (30.4–34.7) | 20.8 (19.1–22.4) | 13.4 (13.0–13.7) |

| Uninsured | 13.2 (10.7–15.7) | 27.6 (24.9–30.2) | 57.9 (54.6–61.3) | 35.8 (32.3–39.3) | 31.1 (27.9–34.3) | 25.2 (22.3–28.2) | 14.8 (14.1–15.4) |

| Regular health care access | |||||||

| ≥1 Health care facilities | 21.2 (19.1–23.4) | 32.9 (31.2–34.6) | 44.4 (42.0–46.9) | 39.5 (36.8–42.1) | 32.8 (30.8–34.8) | 22.4 (20.9–24.0) | 13.6 (13.2–14.0) |

| None | 16.6 (13.7–19.6) | 34.3 (31.1–37.5) | 48.0 (44.9–51.2) | 41.8 (37.2–46.4) | 30.7 (26.9–34.5) | 19.5 (16.5–22.6) | 14.0 (13.3–14.7) |

| Country of birth | |||||||

| United States | 19.0 (16.8–21.2) | 32.4 (30.6–34.2) | 47.5 (45.0–49.9) | 40.5 (37.9–43.1) | 31.8 (29.8–33.8) | 21.4 (19.7–23.0) | 14.2 (13.7–14.6) |

| Other countries | 24.9 (21.3–28.4) | 36.8 (33.4–40.3) | 36.1 (32.7–39.5) | 38.1 (34.1–42.1) | 33.4 (30.0–36.8) | 23.8 (20.9–26.8) | 12.2 (11.7–12.6) |

Please refer to Table S5 for sample sizes. Sample sizes were unweighted.

Estimates for overall and by age groups were unadjusted. Other estimates were age‐standardized to the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey nonpregnant adult population, using the age groups 18 to 29 years, 30 to 39 years, and 40 to 44 years. All estimates were weighted.

Included current smoking, excessive drinking, poor diet quality, inadequate physical activity, and inappropriate sleep duration (definitions are shown in the Table 1 footnote).

Included dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (definitions are shown in the Table 2 footnote).

Based on the equation with body mass index included as a covariate from the Framingham Heart Study.

The “other” group included other non‐Hispanic ethnicities and mixed races.

Food security level was measured using the US Household Food Security Survey Module in which 10 questions were used to create 4 response levels: full food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. Low food security and very low food security were combined into the “Insecure” category.

Renting a home or having other arrangements.

Explaining Racial and Ethnic Disparities Through Adjustment

The differences between non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic individuals and non‐Hispanic White individuals in the prevalence of many cardiometabolic diseases were attenuated after adjusting for social risk factors but further adjustment of lifestyle factors did not qualitatively alter the results (Table 4). Based on the fully adjusted models, the prevalence of obesity (difference in prevalence, 7.3% [95% CI, 3.3%–11.3%]), severe obesity (3.1% [95% CI, 1.1%–5.1%]), hypertension (6.7% [95% CI, 4.1%–9.3%]), prediabetes (8.1% [95% CI, 3.5%–12.6%]), and diabetes (2.4% [95% CI, 0.7%–4.1%]) as well as 30‐year risk of ASCVD (2.0% [95% CI, 1.3%–2.7%]) remained significantly higher in non‐Hispanic Black individuals compared with non‐Hispanic White individuals. Compared with non‐Hispanic White individuals, Hispanic individuals had a significantly higher prevalence of obesity (13.6% [95% CI, 8.9%–18.2%]), prediabetes (7.6% [95% CI, 1.9%–13.3%]), NAFLD (7.8% [95% CI, 2.7v–12.9%]), and metabolic syndrome (6.9% [95% CI, 3.0%–10.9%]) after adjusting for all factors; however, the difference in the prevalence of dyslipidemia and diabetes was no longer significant. After adjusting for social risk factors, the significant difference in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and 30‐year risk of ASCVD disappeared between non‐Hispanic Asian and non‐Hispanic White individuals. Compared with non‐Hispanic White individuals, non‐Hispanic Asian individuals had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension (6.7% [95% CI, 2.4%–10.9%]) after adjusting for all factors. Racial and ethnic differences in most diseases did not change materially after adjusting for lifestyle factors only.

Table 4.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Diseases Adjusting for Demographic Variables, Social Risk Factors, and Lifestyle Factors

| No.* | Difference in the prevalence, % (95% CI)† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic diseases‡ | Age‐, age squared‐, and sex‐adjusted | Age‐, age squared‐, sex‐, and social risk factors‐adjusted§ | Age‐, age squared‐, sex‐, and lifestyle factors‐adjusted|| | Age‐, age squared‐, sex‐, social risk factors‐, and lifestyle factors‐adjusted§ , || | |

| Obesity | |||||

| Asian—White | 6644 | −17.9 (−22.1 to −13.8) | −7.9 (−14.4 to −1.5) | −16.1 (−20.5 to −11.7) | −7.6 (−13.9 to −1.2) |

| Black—White | 11.2 (6.6 to 15.7) | 8.3 (4.3 to 12.3) | 9.6 (5.2 to 14.0) | 7.3 (3.3 to 11.3) | |

| Hispanic—White | 10.8 (6.7 to 14.9) | 13.7 (9.0 to 18.5) | 11.0 (6.9 to 15.1) | 13.6 (8.9 to 18.2) | |

| Severe obesity | |||||

| Asian—White | 6644 | −6.4 (−8.3 to −4.5) | −4.5 (−7.9 to −1.1) | −6.1 (−8.1 to −4.1) | −4.4 (−7.9 to −1.0) |

| Black—White | 5.2 (2.8 to 7.6) | 3.2 (1.2 to 5.2) | 4.7 (2.3 to 7.0) | 3.1 (1.1 to 5.1) | |

| Hispanic—White | 1.7 (−0.8 to 4.2) | 2.8 (−0.3 to 5.9) | 2.0 (−0.4 to 4.5) | 2.9 (−0.2 to 6.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia | |||||

| Asian—White | 6374 | −3.4 (−8.7 to 2.0) | 0.3 (−6.6 to 7.3) | −1.2 (−6.4 to 4.1) | −0.2 (−6.8 to 6.4) |

| Black—White | −3.9 (−7.7 to 0.0) | −7.8 (−11.6 to −3.9) | −5.7 (−9.6 to −1.7) | −8.4 (−12.3 to −4.5) | |

| Hispanic—White | 7.3 (3.4 to 11.1) | 2.4 (−2.5 to 7.3) | 7.6 (3.8 to 11.3) | 2.9 (−1.9 to 7.8) | |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Asian—White | 6573 | −0.1 (−2.8 to 2.5) | 6.4 (1.9 to 10.8) | 1.1 (−1.8 to 4.1) | 6.7 (2.4 to 10.9) |

| Black—White | 8.5 (5.5 to 11.5) | 6.8 (4.3 to 9.3) | 8.1 (5.2 to 11.0) | 6.7 (4.1 to 9.3) | |

| Hispanic—White | 0.3 (−1.8 to 2.5) | 1.6 (−0.8 to 4.0) | 0.5 (−1.6 to 2.6) | 1.5 (−0.9 to 3.9) | |

| Prediabetes | |||||

| Asian—White | 3450 | 0.9 (−3.8 to 5.6) | 3.4 (−2.6 to 9.4) | 4.4 (−0.3 to 9.2) | 4.5 (−1.4 to 10.5) |

| Black—White | 9.5 (5.3 to 13.7) | 7.4 (2.9 to 11.8) | 9.6 (5.4 to 13.8) | 8.1 (3.5 to 12.6) | |

| Hispanic—White | 10.0 (5.4 to 14.6) | 6.6 (1.2 to 12.1) | 11 (6.4 to 15.6) | 7.6 (1.9 to 13.3) | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Asian—White | 3450 | 0.4 (−1.1 to 2.0) | 1.4 (−0.9 to 3.7) | 0.6 (−1.1 to 2.3) | 1.3 (−0.9 to 3.6) |

| Black—White | 3.1 (1.5 to 4.7) | 2.3 (0.7 to 3.9) | 3.3 (1.6 to 4.9) | 2.4 (0.7 to 4.1) | |

| Hispanic—White | 1.8 (0.3 to 3.4) | 1.1 (−0.5 to 2.8) | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 1.0 (−0.5 to 2.6) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| Asian—White | 6337 | −0.4 (−2.9 to 2.1) | −0.7 (−3.9 to 2.4) | −0.4 (−3.0 to 2.2) | −0.7 (−3.8 to 2.4) |

| Black—White | 2.0 (0.1 to 3.9) | 1.3 (−0.7 to 3.3) | 1.9 (0.0 to 3.9) | 1.2 (−0.9 to 3.2) | |

| Hispanic—White | 0.6 (−1.5 to 2.8) | −0.8 (−3 to 1.4) | 0.4 (−1.7 to 2.5) | −1.0 (−3.2 to 1.2) | |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | |||||

| Asian—White | 5305 | −1.4 (−6.7 to 3.8) | −0.9 (−7.7 to 5.8) | −1.7 (−7.0 to 3.6) | −1.0 (−7.8 to 5.7) |

| Black—White | −10.5 (−15.7 to −5.3) | −11.9 (−17.0 to −6.9) | −11.4 (−16.5 to −6.3) | −12.7 (−17.7 to −7.7) | |

| Hispanic—White | 9.5 (4.7 to 14.2) | 8.2 (3.2 to 13.2) | 8.9 (4.2 to 13.7) | 7.8 (2.7 to 12.9) | |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||||

| Asian—White | 3228 | −5.7 (−10.3 to −1.1) | 2.5 (−3.6 to 8.5) | −3.7 (−8.9 to 1.4) | 2.5 (−3.6 to 8.5) |

| Black—White | −0.6 (−4.9 to 3.7) | −3.3 (−7.0 to 0.4) | −1.0 (−5.2 to 3.3) | −3.3 (−7.1 to 0.4) | |

| Hispanic—White | 5.8 (2.3 to 9.4) | 6.6 (2.7 to 10.5) | 6.7 (3.1 to 10.4) | 6.9 (3.0 to 10.9) | |

| Having 0 cardiometabolic diseases¶ | |||||

| Asian—White | 3152 | 7.1 (−0.3 to 14.4) | 4.3 (−4.4 to 12.9) | 4.7 (−2.9 to 12.3) | 5.5 (−3.6 to 14.6) |

| Black—White | 1.1 (−4.2 to 6.4) | 5.9 (0.7 to 11.2) | 4.1 (−1.0 to 9.3) | 7.6 (2.5 to 12.8) | |

| Hispanic—White | −7.3 (−13.0 to −1.6) | −4.7 (−11.3 to 1.9) | −8.4 (−14.3 to −2.6) | −6.0 (−12.8 to 0.8) | |

| Having only 1 cardiometabolic disease¶ | |||||

| Asian—White | 2923 | −2.3 (−9.5 to 4.9) | −5.1 (−13.9 to 3.7) | −2.9 (−10.3 to 4.4) | −5.4 (−14.2 to 3.4) |

| Black—White | −2.1 (−6.4 to 2.1) | −2.5 (−6.6 to 1.6) | −1.9 (−6.1 to 2.4) | −2.5 (−6.6 to 1.6) | |

| Hispanic—White | 3.6 (−1.0 to 8.2) | 3.4 (−2.5 to 9.3) | 3.5 (−1.1 to 8.1) | 3.2 (−2.7 to 9.1) | |

| Having at least 2 cardiometabolic diseases¶ | |||||

| Asian—White | 3198 | −1.6 (−6.4 to 3.2) | 2.2 (−3.5 to 7.8) | −1.5 (−6.4 to 3.4) | 1.1 (−4.4 to 6.5) |

| Black—White | 2.3 (−2.1 to 6.6) | −0.5 (−4.5 to 3.5) | 0.9 (−3.4 to 5.1) | −1.3 (−5.4 to 2.7) | |

| Hispanic—White | 6.5 (2.5 to 10.4) | 5.1 (0.7 to 9.5) | 6.1 (2.4 to 9.9) | 4.7 (0.4 to 9.0) | |

| 30‐year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease# | |||||

| Asian—White | 3364 | −3.2 (−4.1 to −2.4) | 0.0 (−0.9 to 0.9) | −2.0 (−2.8 to −1.3) | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.6) |

| Black—White | 2.9 (2.0 to 3.7) | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.5) | 2.4 (1.7 to 3.1) | 2.0 (1.3 to 2.7) | |

| Hispanic—White | −0.3 (−1.1 to 0.5) | 0.0 (−0.9 to 0.9) | 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.1 to 1.8) | |

Unweighted sample size.

Multivariable weighted logistic regression models were used to assess racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases.

Definitions for cardiometabolic diseases are shown in the Table 2 footnote.

Social risk factors included education (<high school, high school graduate, some college, and ≥college graduate), family income‐to‐poverty ratio (≤100%, >100%–299%, 300%–499%, and ≥500%), home ownership (yes/no), employment status (yes/no), health insurance status (yes/no), regular health care access (yes/no), food security status (secure, marginal, and insecure), and country of birth (United States/others).

Lifestyle factors included smoking status (never, former, and current), drinking status (never, former, nonexcessive, and excessive), Healthy Eating Index‐2015 score, Healthy Eating Index‐2015 score squared, physical activity (minutes), physical activity squared, sleep hours, and sleep hours squared.

Included dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Definitions for cardiometabolic diseases are shown in the Table 2 footnote.

Based on the equation with body mass index included as a covariate from the Framingham Heart Study.

Results for racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors after adjusting for social risk factors are shown in Table S6.

Sensitivity Analysis

The estimated age‐standardized prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases according to education level among young adults aged ≥25 years is shown in Table S7. Results were consistent with those of primary analyses. The racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases and lifestyle risk factors without adjusting for family income‐to‐poverty ratio (Tables S8 and S9) were similar to those of primary analyses. The prevalence of poor diet quality was 24.2% (95% CI, 22.1%–26.2%) for <41 (25th percentile of the HEI‐2015 score) out of 100 and 74.9% (95% CI, 72.8%–76.9%) for <60 out of 100 (Table S10). Results of subgroup analyses for these 2 definitions were similar to those of primary analyses.

Discussion

Based on this serial cross‐sectional analysis of the NHANES data, US young adults aged 18 to 44 years had poor cardiometabolic health. Only 1 in 5 young adults had no lifestyle risk factors and less than half had the absence of cardiometabolic diseases. Approximately 45% and 22% of young adults had at least 2 lifestyle risk factors and at least 2 cardiometabolic diseases, respectively. Significant differences in the prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases by race and ethnicity as well as social risk factors were identified. Racial and ethnic disparities in many cardiometabolic diseases persisted even after accounting for social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Poor diet quality and inadequate sleep duration were highly prevalent among young adults, especially in non‐Hispanic Black individuals and young adults with an unfavorable social risk factor profile. It is well reported that most US people consumed low‐quality diets, although the definitions used for assessing diet quality differed. 7 , 30 Previous studies reported a trend for increasing diet quality with increasing age 31 and this study also found that emerging adults aged 18 to 24 years had the lowest diet quality. Young adults tended to have inadequate sleep duration because of the technology use. 32 That US young adults had poor lifestyle behaviors was further supported by that the prevalence of current smoking, excessive drinking, and inadequate physical activity was about 20%. Generally, behaviors are established in young adulthood and continue to middle age. Exposure to lifestyle risk factors early is harmful accumulatively to people's health throughout the life course. 33

Young adults are commonly perceived as healthy. However, this analysis found that one third of young adults had obesity, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD, a quarter had prediabetes, and 1 in 5 had metabolic syndrome. These diseases are known strong risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mortality and pharmaceutical or lifestyle treatments should be used after diagnosis. Furthermore, cardiometabolic diseases occurring in young adulthood also affect work productivity. 34 Therefore, young adults' cardiometabolic health needs more attention, especially that of non‐Hispanic Black individuals, Hispanic individuals, and people with an unfavorable social risk factor profile who were at increased risk of cardiometabolic diseases.

Previous studies reported that 2 or more lifestyle risk factors and 2 or more cardiometabolic diseases often clustered together among general adults. 35 , 36 Results of this study extend this evidence to young adults. The prevalence of having 2 or more lifestyle risk factors was higher than that of having only 1% and 22% of young adults had at least 2 cardiometabolic diseases. Similar to other studies, the clustering phenomenon was more common in non‐Hispanic Black individuals, Hispanic individuals, and adults with an unfavorable social risk factor profile. 37 , 38 Importantly, the coexistence of multiple lifestyle risk factors may create synergies, resulting in a greater health impact than individual behaviors alone. 39 Multimorbidity has also been associated with a lower life expectancy than a single disease. 40 Accordingly, health promotion activities may consider targeting 2 or more related lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases simultaneously.

Racial and ethnic disparities in lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases were notable even after adjusting for social risk factors. Non‐Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals generally had poorer cardiometabolic health than non‐Hispanic White individuals. Non‐Hispanic Asian individuals had relatively healthier behaviors except for physical activity and fewer cardiometabolic diseases than other racial and ethnic subgroups. A recent study by He et al reported that social risk factors contributed to but did not fully explain racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic health. 12 In addition, the current study found, in agreement with a previous study conducted in the general adult population, that lifestyle risk factors made little or only a small contribution to racial and ethnic disparities regardless of whether social risk factors were accounted for. 41 Adjusting for social risk factors reduced but did not eliminate racial and ethnic disparities because apart from social risk factors and lifestyle factors, other factors such as childhood adverse exposures, neighborhood characteristics, social networks, perceived discrimination, genetics, and epigenetics may also contribute. 16 , 42 Furthermore, this study included selected social risk factors with possibility of measurement error and thus the social risk factor profile was not comprehensively and precisely assessed.

Race categorization in this study was a social construct, not a biological attribute. Structural racism, which is deeply embedded in the economic system as well as in cultural and societal norms, produces widespread unfair treatment of people of color and ultimately leads to racial and ethnic disparities in health. 43 The pathways linking structural racism with biological consequences such as cardiometabolic diseases and related clinical risk factors are complex and multilayered, including but not limited to psychological/physical stress, poor diet and health behaviors, poor community/social support, unhealthy living conditions, as well as differential health care access, diagnosis, treatment, and insurance coverage. 44 , 45 Social risk factors and lifestyle factors assessed in this study were merely selective, easily measurable manifestations of structural racism, not a complete assessment by design. Therefore, it is within our expectation that social risk factors and lifestyle factors considered in this study did not fully explain racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases. Nonetheless, most of these factors are in theory modifiable and thus can serve as actionable intervention targets at the policy, community, and individual level.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize the epidemiological landscape of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases by race and ethnicity and social risk factors among a nationally representative sample of young adults. Findings of this study provide data to quantify the burden of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases among young adults and to identify high‐risk subgroups for intervention. Furthermore, racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic diseases were characterized and selected contributors to the disparities were assessed. Young adulthood is a vulnerable period for engagement in health‐damaging behaviors and for developing cardiometabolic diseases and risk factors. Given that cardiometabolic diseases are largely preventable and lifestyle risk factors are theoretically modifiable, devising effective and targeted interventions to improve cardiometabolic health in young adults would deliver long‐term health benefits and reduce economic costs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, reporting bias was likely for self‐reported data. Second, misclassification of disease was possible by using self‐reported diagnosis and laboratory test(s) from a single time point. Furthermore, several cardiometabolic diseases (eg, dyslipidemia and NAFLD) had more than 1 definition, although this study selected a most widely used one. Third, many social risk factors are challenging to measure precisely. Fourth, missing data may have caused bias in specific estimates, particularly from those analyses involving more than 10% missing data (eg, excessive drinking). Such analyses were adjusted for missing data. Furthermore, results were robust with excluding the income variable, the covariate with the highest percentage of missing data. Fifth, this study was cross‐sectional and observational. Causal inferences cannot be made and reverse causality bias cannot be ruled out. Sixth, due to the descriptive and exploratory study design, adjustment for multiple comparisons was not performed. Thus, some inferences drawn from the results may not be reproducible.

Conclusions

The prevalence of lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases was high among US young adults in 2011 to 2018. Only 1 in 5 young adults had no lifestyle risk factors, and less than half were free of cardiometabolic diseases. The prevalence of both lifestyle risk factors and cardiometabolic diseases varied by race and ethnicity and social risk factors. Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiometabolic diseases were not fully explained by differences in social risk factors and lifestyle factors.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Program for Young Eastern Scholars at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Education (QD2020027).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S10

Figures S1–S3

This article was sent to Mahasin S. Mujahid, PhD, MS, FAHA, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.028926

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 15.

Contributor Information

Victor W. Zhong, Email: wenze.zhong@shsmu.edu.cn.

Nannan Feng, Email: nnfeng@shsmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Andersson C, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in young individuals. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:230–240. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999‐2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017‐2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang L, Li X, Wang Z, Bancks MP, Carnethon MR, Greenland P, Feng YQ, Wang H, Zhong VW. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999‐2018. JAMA. 2021;326:1–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999‐2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.Hyp.0000252676.46043.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ostchega Y, Fryar CD, Nwankwo T, Nguyen DT. Hypertension prevalence among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2017‐2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;364:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu J, Micha R, Li Y, Mozaffarian D. Trends in food sources and diet quality among US children and adults, 2003‐2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215262. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ussery EN, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Katzmarzyk PT, Carlson SA. Joint prevalence of sitting time and leisure‐time physical activity among US adults, 2015‐2016. JAMA. 2018;320:2036–2038. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saydah S, Bullard KM, Imperatore G, Geiss L, Gregg EW. Cardiometabolic risk factors among US adolescents and young adults and risk of early mortality. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e679–e686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gooding HC, Shay CM, Ning H, Gillman MW, Chiuve SE, Reis JP, Allen NB, Lloyd‐Jones DM. Optimal lifestyle components in young adulthood are associated with maintaining the ideal cardiovascular health profile into middle age. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002048. doi: 10.1161/jaha.115.002048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whitaker KM, Jacobs DR Jr, Kershaw KN, Demmer RT, Booth JN III, Carson AP, Lewis CE, Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Gordon‐Larsen P, et al. Racial disparities in cardiovascular health behaviors: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He J, Zhu Z, Bundy JD, Dorans KS, Chen J, Hamm LL. Trends in cardiovascular risk factors in US adults by race and ethnicity and socioeconomic status, 1999‐2018. JAMA. 2021;326:1286–1298. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogden CL, Fakhouri TH, Carroll MD, Hales CM, Fryar CD, Li X, Freedman DS. Prevalence of obesity among adults, by household income and education–United States, 2011‐2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1369–1373. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6650a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, Jaeger BC, Wozniak G, Levitan EB, Colantonio LD. Trends in blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension, 1999‐2000 to 2017‐2018. JAMA. 2020;324:1190–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akam EY, Nuako AA, Daniel AK, Stanford FC. Racial disparities and cardiometabolic risk: new horizons of intervention and prevention. Curr Diab Rep. 2022;22:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s11892-022-01451-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gooding HC, Gidding SS, Moran AE, Redmond N, Allen NB, Bacha F, Burns TL, Catov JM, Grandner MA, Harris KM, et al. Challenges and opportunities for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease among young adults: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016115. doi: 10.1161/jaha.120.016115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm. Accessed December 13, 2022.

- 19. Hernandez DC, Reesor LM, Murillo R. Food insecurity and adult overweight/obesity: gender and race/ethnic disparities. Appetite. 2017;117:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hagman BT, Falk D, Litten R, Koob GF. Defining recovery from alcohol use disorder: development of an NIAAA research definition. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:807–813. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21090963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krebs‐Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Lerman JL, Tooze JA, Wilson MM, Reedy J. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI‐2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. Available at: https://health.gov/our‐work/nutrition‐physical‐activity/physical‐activity‐guidelines. Accessed December 13, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish‐Gozal L, et al. National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30‐year risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009;119:3078–3084. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.108.816694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shin JI, Bautista LE, Walsh MC, Malecki KC, Nieto FJ. Food insecurity and dyslipidemia in a representative population‐based sample in the US. Prev Med. 2015;77:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X, Seo YA, Park SK. Serum selenium and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2016. Environ Res. 2021;197:111190. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. doi: 10.1161/circ.106.25.3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnson CL, Paulose‐Ram R, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kruszon‐Moran D, Dohrmann SM, Curtin LR. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999‐2010. Vital Health Stat. 2013;2:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shan Z, Rehm CD, Rogers G, Ruan M, Wang DD, Hu FB, Mozaffarian D, Zhang FF, Bhupathiraju SN. Trends in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and diet quality among US adults, 1999‐2016. JAMA. 2019;322:1178–1187. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Imamura F, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Fahimi S, Shi P, Powles J, Mozaffarian D. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e132–e142. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109X(14)70381-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gradisar M, Wolfson AR, Harvey AG, Hale L, Rosenberg R, Czeisler CA. The sleep and technology use of Americans: findings from the National Sleep Foundation's 2011 Sleep in America poll. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:1291–1299. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stroud C, Walker LR, Davis M, Irwin CE Jr. Investing in the health and well‐being of young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Magliano DJ, Martin VJ, Owen AJ, Zomer E, Liew D. The productivity burden of diabetes at a population level. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:979–984. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Héroux M, Janssen I, Lee DC, Sui X, Hebert JR, Blair SN. Clustering of unhealthy behaviors in the aerobics center longitudinal study. Prev Sci. 2012;13:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0255-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, Meinow B, Fratiglioni L. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ortiz C, López‐Cuadrado T, Rodríguez‐Blázquez C, Pastor‐Barriuso R, Galán I. Clustering of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, self‐rated health and disability. Prev Med. 2022;155:106911. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cook WK, Kerr WC, Karriker‐Jaffe KJ, Li L, Lui CK, Greenfield TK. Racial/ethnic variations in clustered risk behaviors in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58:e21–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noble N, Paul C, Turon H, Oldmeadow C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the clustering of smoking, nutrition, alcohol and physical activity ('SNAP') health risk factors. Prev Med. 2015;81:16–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Di Angelantonio E, Kaptoge S, Wormser D, Willeit P, Butterworth AS, Bansal N, O'Keeffe LM, Gao P, Wood AM, Burgess S, et al. Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. JAMA. 2015;314:52–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cubbins LA, Buchanan T. Racial/ethnic disparities in health: the role of lifestyle, education, income, and wealth. Sociol Focus. 2009;42:172–191. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2009.10571349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The social determinants of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S5–s12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baumer Y, Powell‐Wiley TM. Interdisciplinary approaches are fundamental to decode the biology of adversity. Cell. 2021;184:2797–2801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Javed Z, Haisum Maqsood M, Yahya T, Amin Z, Acquah I, Valero‐Elizondo J, Andrieni J, Dubey P, Jackson RK, Daffin MA. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15:e007917. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.007917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S10

Figures S1–S3