Abstract

Purpose of Review

The objective of this study was to explore the clinical spectrum of movement disorders and associated neurologic findings in hypomagnesemia and challenges in diagnosis and treatment.

Recent Findings

Sixty patients were identified in the literature for analysis. Movement disorders observed were postural tremor (23.3%, n = 14), resting tremor (8.3%, n = 5), intention tremor (10%, n = 6), ataxia involving the trunk (48.3%, n = 29) or limbs (25%, n = 15) and dysarthria (21.7%, n = 13), athetosis (8.3%, n = 5), myoclonus (6.7%, n = 4), and chorea (1.8%, n = 1). Symptoms may be accompanied by downbeat nystagmus, tetany, drowsiness, vertigo, and proximal muscle weakness. Residual deficits were noted in 16 (26.67%) patients. Serum magnesium was 1.3 mg/dL or lower in 53 patients (88.3%). Imaging findings include bilateral cerebellar (20%, n = 11) and vermis hyperintensities (9.09%, n = 5) and normal imaging. Proton pump inhibitors are the commonest etiology.

Summary

The movement disorders linked with hypomagnesemia can be associated with varied neurologic symptoms. A high degree of suspicion will enable early diagnosis to prevent residual deficits.

Introduction

Evaluation of a new-onset movement disorder can be challenging due to its association with a wide range of etiologic factors. These include vascular, toxic, drug-induced, metabolic, immune-mediated, genetic, or neurodegenerative diseases. Clinical history and examination can give clue toward genetic, drug-induced, or toxic causes. While imaging can be rewarding in the presence of specific abnormalities, it is common for imaging to be normal or show nonspecific lesions that calls for more detailed evaluation. Although the clinical course can give a clue for the diagnosis, the opportunity to prevent the residual damage in a treatable disease can be lost in the process, if there is a delay in the diagnosis.

Metabolic alterations are one of the common causes of treatable new-onset movement disorder.1 Disorders of calcium and glucose metabolism are common causes of acute movement disorders.2,3 Magnesium is the second most abundant intracellular cation after potassium.4 Compared with calcium, magnesium has received far less attention in its role in etiology of movement disorders.

The incidence of hypomagnesemia is as high as 60% in ICU.5 However, hypomagnesemia is frequently underdiagnosed.6 In addition to life-threatening cardiac arrythmias, hypomagnesemia is associated with a plethora of neurologic disorders such as headache, depression, seizures, and movement disorders. The first report of neurologic deficits (twitching of extremities, seizures) due to hypomagnesemia was detailed by Hirschfelder in 1934.7

This review aims to discuss the movement disorders associated with hypomagnesemia and other neurologic findings and challenges in diagnosis and treatment. The first section of the review discusses the metabolism of magnesium and etiology of hypomagnesemia. The next section elaborates the neurologic presentation of hypomagnesemia with special emphasis on movement disorders and the mechanism of neurologic involvement. Subsequently, the management of hypomagnesemia in the context of neurologic manifestations is detailed.

Methods

Search Strategy

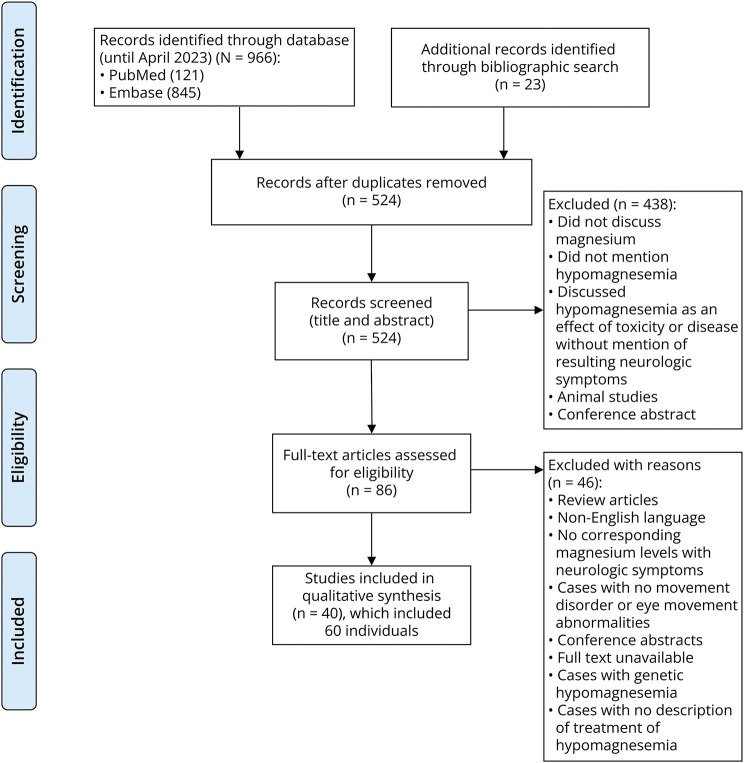

The systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A search for published literature was conducted in PubMed and EMBASE database for studies published before April 10, 2023, using the index terms “hypomagnesemia” combined with “ataxia,” “tremors,” “nystagmus,” “eye movement,” “myoclonic jerks,” “chorea,” or “athetosis” by standard search. Additional articles were selected manually from the bibliography of the relevant articles. Information regarding the demographics, clinical presentation, corresponding serum magnesium levels during presentation, imaging, evaluation, management, and outcome was collected and analyzed. The review has not been registered.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Relevant studies were considered for analysis after screening the abstract and full text, which was undertaken independently by 2 independent reviewers (S.R. and K.W.P.). The articles were considered for analysis if (1) movement disorders or eye movement abnormalities were present in association with hypomagnesemia, (2) a reversal in clinical features was noted after correction of hypomagnesemia, and (3) there were no concurrent medical conditions to which the clinical presentation could be attributed. Articles were excluded if (1) the details of individual clinical presentation and clinical course and the corresponding serum magnesium levels were not available, (2) studies were in languages other than English, (3) serum magnesium values were not mentioned for patients who had movement disorder, (4) patients experienced genetic disorders that did not solely lead to low serum magnesium levels, (5) full text was unavailable, including conference abstract. For patients who have serial magnesium testing values documented, the lowest magnesium levels were considered for analysis. Patients were considered to have residual deficits if clinical features persisted beyond a week after restoration of serum magnesium levels.

Selection of Studies

Search using the terms “hypomagnesemia” combined with “ataxia” revealed 216 results of which 16 were relevant and included. Search using the terms “magnesium” or “hypomagnesemia” combined with “tremors” revealed 520 results of which 12 articles were relevant. “Hypomagnesemia” and “nystagmus” or “eye movement” revealed 125 results of which 16 articles were relevant. “Hypomagnesemia” and “chorea,” “athetosis,” and “myoclonic jerks” revealed 23 results with articles obtained through cross-referencing alone. After elimination of duplicate results, 40 articles were identified.

Analysis was performed using SPSS 23. The magnesium values were converted into mg/dL units and described in the form of mean and SD and range. Categorical variables were described in the form of frequencies (Figure).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart of the Systematic Review.

Results and Discussion

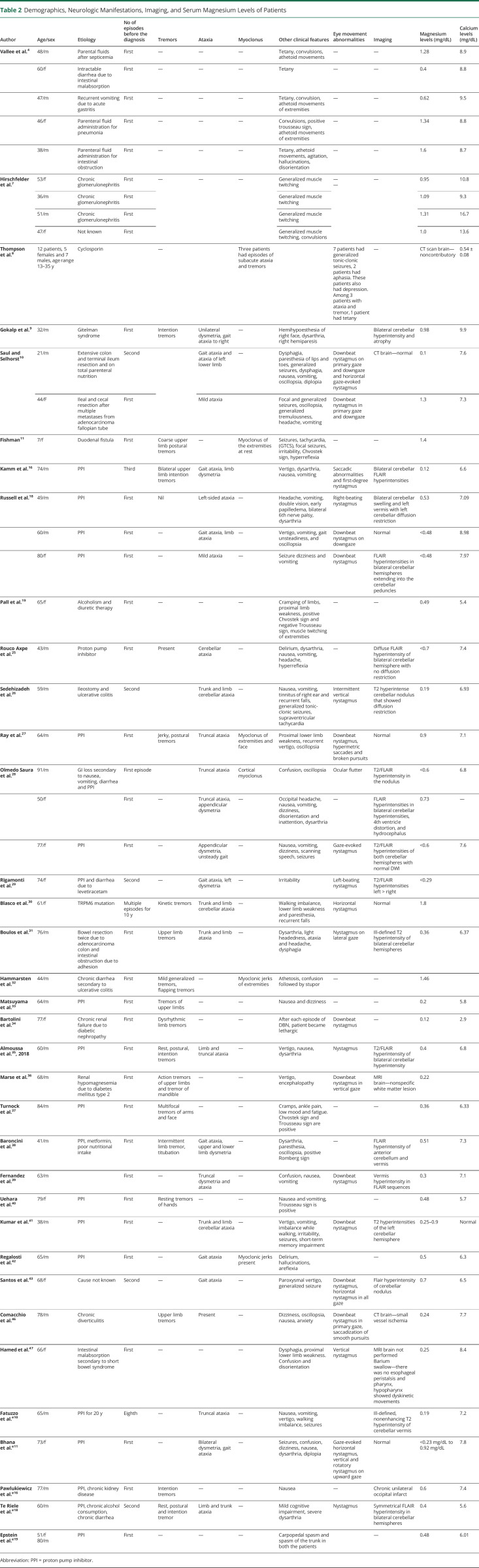

In this study, 60 patients were identified in the literature for analysis. The mean age of presentation of hypomagnesemia with neurologic involvement was 54.9 ± 18.2 years (range: 7–91 years). Hypomagnesemia associated with movement disorders was observed in 36 male patients (61.7%) and 19 female patients (31.7%). Commonest movement disorders associated with hypomagnesemia were tremors in the form of postural tremor (23.3%, n = 14), resting tremor (8.3%, n = 5), and intention tremor (10%, n = 6) and ataxia that could be involve the trunk (48.3%, n = 29) or limbs (25%, n = 15) and dysarthria (21.7%, n = 13). Relatively rare movement disorders reported in association with hypomagnesemia were athetosis (8.3%, n = 5), myoclonus (6.7%, n = 4), and chorea (1.8%, n = 1). Signs of tetany were noted in the form of intermittent stiffening (1.9%, n = 1), carpopedal spasm (13.3%, n = 8), Chvostek sign (8.3%, n = 5), and Trousseau sign (5%, n = 3). Downbeat nystagmus (DBN) was reported in 26.7% of patients (n = 16), while horizontal nystagmus was seen in 18.3% of patients (n = 11). Two patients had torsional nystagmus. These symptoms may be accompanied by diplopia (6.7%, n = 4), oscillopsia (13.3%, n = 8), cognitive impairment (3.3%, n = 2), confusion and disorientation (38.18%, n = 23), and drowsiness (6.7%, n = 4), which shall be discussed in subsequent sections.

Other symptoms and signs seen in hypomagnesemia were cramps (3.3%, n = 2), nausea/vomiting (35%, n = 21), headache (13.3%, n = 8), vertigo (18.3%, n = 11), dizziness (18.3%, n = 11), focal and generalized seizures (36.7%, n = 22), twitching of extremities (15%, n = 9), and hyperreflexia (6.7%, n = 4). Paresthesia and dysphagia were seen in 2 and 3 patients, respectively, while hemihypoesthesia was noted in 1 patient. Proximal muscle weakness (6.7%, n = 4) was also observed that may or may not be in conjunction with elevated CPK (6.7%, n = 4). Transient aphasia,8 transient hemiparesis,9 and extensor plantar response have also been reported in association with hypomagnesemia.10 Sixteen patients (29.09%) had residual deficits at follow-up. The common symptoms were nystagmus, dizziness, gait ataxia, and cognitive impairment.

Details of imaging studies are available for 27 patients. Commonest imaging finding was bilateral cerebellar hyperintensities (20%, n = 11). Cerebellar edema was severe enough to cause fourth ventricle narrowing and hydrocephalus in 2 patients. Hyperintensity of the vermis was observed in 5 patients (9.09%), while unilateral cerebellar hyperintensity was found in 1 patient. Five patients had normal imaging.

In our review of literature, commonest etiology was the use of PPI (38.3%, n = 23). The other causes of hypomagnesemia were intestinal resection, intestinal malabsorption, alcoholism, prolonged administration of parenteral fluids, chronic vomiting, use of diuretics, ciclosporin, chronic kidney disease, and a combination of these factors. Mean serum magnesium levels were 0.67 ± 0.44 mg/dL (range 0.01–1.8 mg/dL). Serum magnesium was 1.3 mg/dL or lower in 53 (88.3%) patients, of which 46 (76.6%) patients had magnesium levels lower than 1 mg/dL.

Magnesium and Its Metabolism

Magnesium is predominantly stored in the bones and to a lesser extent in the muscles, brain, and liver.11 The serum magnesium constitutes less than 1% of total body magnesium stores,12 while 90% of the magnesium is stored intracellularly,13 implying that serum magnesium is a poor indicator of total body magnesium stores. The concentration of magnesium is higher in the CSF than that in the serum.11,14 The absorption of magnesium takes place mainly through jejunum and ileum.5 Approximately 80% of magnesium is filtered through the kidneys, mainly reabsorbed through the distal convoluted tubule and thick ascending part of Loop of Henle.5

Etiology of Hypomagnesemia

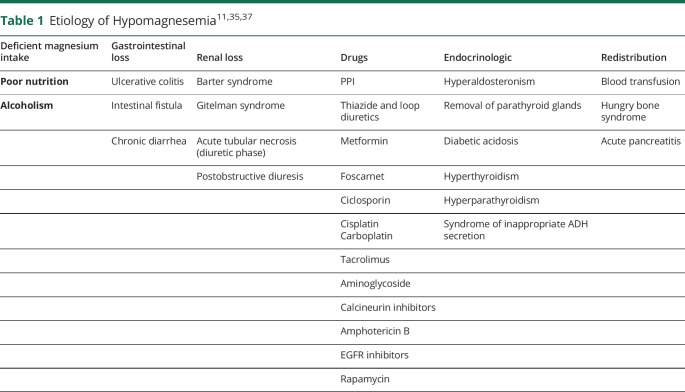

The causes of acquired hypomagnesemia are listed in Table 1.15,16 Hypomagnesemia can be due to decreased oral intake or absorption, increased redistribution, or losses through renal or gastrointestinal route.

Table 1.

| Deficient magnesium intake | Gastrointestinal loss | Renal loss | Drugs | Endocrinologic | Redistribution |

| Poor nutrition | Ulcerative colitis | Barter syndrome | PPI | Hyperaldosteronism | Blood transfusion |

| Alcoholism | Intestinal fistula | Gitelman syndrome | Thiazide and loop diuretics | Removal of parathyroid glands | Hungry bone syndrome |

| Chronic diarrhea | Acute tubular necrosis (diuretic phase) | Metformin | Diabetic acidosis | Acute pancreatitis | |

| Postobstructive diuresis | Foscarnet | Hyperthyroidism | |||

| Ciclosporin | Hyperparathyroidism | ||||

| Cisplatin Carboplatin |

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion | ||||

| Tacrolimus | |||||

| Aminoglycoside | |||||

| Calcineurin inhibitors | |||||

| Amphotericin B | |||||

| EGFR inhibitors | |||||

| Rapamycin |

Initially, magnesium supplementation was considered as a treatment for delirium tremors due to its depressant effect.17 This benefit conferred by magnesium could be due to the correction of hypomagnesemia secondary to alcoholism-related malabsorption. Alcoholism leads to hypomagnesemia by causing salt wasting.18 Magnesium loss in the muscle secondary to chronic alcohol consumption is very similar to that noted in intestinal malabsorption.19 One of the commonest causes of hypomagnesemia in recent reports is the chronic intake of proton pump inhibitor (PPI).16 The absorption of magnesium in the small intestine occurs through active transport through the transient receptor potential melastin 6/7 (TRPM6/7) channels located on the apex of the enterocytes into the portal venous system and through the cellular passive diffusion. Long-term intake of PPI hinders the active absorption of magnesium through TRPM6/7 channels while allowing paracellular absorption.18,20 A prolonged intake of PPI (for at least 1 year) is associated with hypomagnesemia.21

The Effect of Hypomagnesemia on Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

Magnesium was first recognized as a CNS depressant in the late 17th century, and this prompted the use of IV magnesium as an anesthetic agent.11 However, it was soon recognized that magnesium has a narrow margin of safety owing to its potential to cause respiratory depression easily when used as an anesthetic agent. It was subsequently used to treat eclampsia in view of the effect of magnesium on lowering the vascular tone and reactivity11,22 and used in refractory status epilepticus.11,23 In the peripheral nervous system, magnesium primarily acts on the neuromuscular junction.11 It diminishes the sensitivity of the end plate to the effect of acetylcholine.11,24 Magnesium deficiency is associated with neuromuscular irritability. In view of predisposition toward neuromuscular irritability by both hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia, the clinical features of both the conditions can overlap. The tetany due to magnesium deficiency is clinically indistinguishable from the tetany secondary to hypocalcemia.4

Clinical Manifestations

Ataxia

Hypomagnesemia is a rare cause of cerebellar ataxia25 and has been termed hypomagnesemia-induced cerebellar syndrome (HICS). HICS has a fluctuating and progressive course25,26 and can be subacute in onset.27,28 Examination reveals truncal and/or limb ataxia,26,29 distal postural or kinetic tremor,25,30 and impaired tandem gait. Accompanying dysarthria is also noted.25 Although ataxia is frequently bilateral, unilateral cerebellar involvement in the form of ataxia of a single lower limb has also been observed.10 In most of these cases, magnesium levels were critically low (Table 2).31

Table 2.

Demographics, Neurologic Manifestations, Imaging, and Serum Magnesium Levels of Patients

| Author | Age/sex | Etiology | No of episodes before the diagnosis | Tremors | Ataxia | Myoclonus | Other clinical features | Eye movement abnormalities | Imaging | Magnesium levels (mg/dL) | Calcium levels (mg/dL) |

| Vallee et al.4 | 48/m | Parental fluids after septicemia | First | — | — | — | Tetany, convulsions, athetoid movements | — | — | 1.28 | 8.9 |

| 60/f | Intractable diarrhea due to intestinal malabsorption | First | — | — | — | Tetany | — | — | 0.4 | 8.8 | |

| 47/m | Recurrent vomiting due to acute gastritis | First | — | — | — | Tetany, convulsion, athetoid movements of extremities | — | — | 0.62 | 9.5 | |

| 46/f | Parenteral fluid administration for pneumonia | First | — | — | — | Convulsions, positive trousseau sign, athetoid movements of extremities | — | — | 1.34 | 8.8 | |

| 38/m | Parenteral fluid administration for intestinal obstruction | First | — | — | — | Tetany, athetoid movements, agitation, hallucinations, disorientation | — | — | 1.6 | 8.7 | |

| Hirschfelder et al.7 | 53/f | Chronic glomerulonephritis | First | — | — | — | Generalized muscle twitching | — — |

— | 0.95 | 10.8 |

| 36/m | Chronic glomerulonephritis | First | Generalized muscle twitching | 1.09 | 9.3 | ||||||

| 51/m | Chronic glomerulonephritis | First | Generalized muscle twitching | 1.31 | 16.7 | ||||||

| 47/f | Not known | First | Generalized muscle twitching, convulsions | 1.0 | 13.6 | ||||||

| Thompson et al.8 | 12 patients, 5 females and 7 males, age range 13–35 y | Cyclosporin | — | Three patients had episodes of subacute ataxia and tremors | 7 patients had generalized tonic-clonic seizures, 2 patients had aphasia. These patients also had depression. Among 3 patients with ataxia and tremor, 1 patient had tetany | — | CT scan brain—noncontributory | 0.54 ± 0.08 | |||

| Gokalp et al.9 | 32/m | Gitelman syndrome | First | Intention tremors | Unilateral dysmetria, gait ataxia to right | — | Hemihypoesthesia of right face, dysarthria, right hemiparesis | Bilateral cerebellar hyperintensity and atrophy | 0.98 | 9.9 | |

| Saul and Selhorst10 | 21/m | Extensive colon and terminal ileum resection and on total parenteral nutrition | Second | Gait ataxia and ataxia of left lower limb | — | Dysphagia, paresthesia of lips and toes, generalized seizures, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, oscillopsia, diplopia | Downbeat nystagmus on primary gaze and downgaze and horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus | CT brain—normal | 0.1 | 7.6 | |

| 44/F | Ileal and cecal resection after multiple metastases from adenocarcinoma fallopian tube | First | Mild ataxia | Focal and generalized seizures, oscillopsia, generalized tremulousness, headache, vomiting | Downbeat nystagmus in primary gaze and downgaze | 1.3 | 7.3 | ||||

| Fishman11 | 7/f | Duodenal fistula | First | Coarse upper limb postural tremors | — | Myoclonus of the extremities at rest | Seizures, tachycardia, (GTCS), focal seizures, irritability, Chvostek sign, hyperreflexia | — | — | 1.4 | |

| Kamm et al.16 | 74/m | PPI | Third | Bilateral upper limb intention tremors | Gait ataxia, limb dysmetria | Vertigo, dysarthria, nausea, vomiting | Saccadic abnormalities and first-degree nystagmus | Bilateral cerebellar FLAIR hyperintensities | 0.12 | 6.6 | |

| Russell et al.18 | 49/m | PPI | First | Nil | Left-sided ataxia | — | Headache, vomiting, double vision, early papilledema, bilateral 6th nerve palsy, dysarthria | Right-beating nystagmus | Bilateral cerebellar swelling and left vermis with left cerebellar diffusion restriction | 0.53 | 7.09 |

| 60/m | PPI | First | — | Gait ataxia, limb ataxia | — | Vertigo, vomiting, gait unsteadiness, and oscillopsia | Downbeat nystagmus on downgaze | Normal | <0.48 | 8.98 | |

| 80/f | PPI | First | — | Mild ataxia | — | Seizure dizziness and vomiting | Downbeat nystagmus | FLAIR hyperintensities in bilateral cerebellar hemispheres extending into the cerebellar peduncles | <0.48 | 7.97 | |

| Pall et al.19 | 65/f | Alcoholism and diuretic therapy | First | — | — | — | Cramping of limbs, proximal limb weakness, positive Chvostek sign and negative Trousseau sign, muscle twitching of extremities | — | — | 0.49 | 5.4 |

| Rouco Axpe et al.25 | 43/m | Proton pump inhibitor | First | Present | Cerebellar ataxia | — | Delirium, dysarthria, nausea, vomiting, headache, hyperreflexia | — | Diffuse FLAIR hyperintensity of bilateral cerebellar hemisphere with no diffusion restriction | <0.7 | 7.4 |

| Sedehizadeh et al.26 | 59/m | Ileostomy and ulcerative colitis | Second | Trunk and limb cerebellar ataxia | — | Nausea, vomiting, tinnitus of right ear and recurrent falls, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, supraventricular tachycardia | Intermittent vertical nystagmus | T2 hyperintense cerebellar nodulus that showed diffusion restriction | 0.19 | 6.93 | |

| Ray et al.27 | 64/m | PPI | First | Jerky, postural tremors | Truncal ataxia | Myoclonus of extremities and face | Proximal lower limb weakness, recurrent vertigo, oscillopsia | Downbeat nystagmus, hypermetric saccades and broken pursuits | Normal | 0.9 | 7.1 |

| Olmedo Saura et al.28 | 91/m | GI loss secondary to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and PPI | First episode | Truncal ataxia | Cortical myoclonus | Confusion, oscillopsia | Ocular flutter | T2/FLAIR hyperintensity in the nodulus | <0.6 | 6.8 | |

| 50/f | First | — | Truncal ataxia, appendicular dysmetria | — | Occipital headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, disorientation and inattention, dysarthria | — | FLAIR hyperintensities in bilateral cerebellar hyperintensities, 4th ventricle distortion, and hydrocephalus | 0.73 | — | ||

| 77/f | PPI | First | — | Appendicular dysmetria, unsteady gait | — | Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, scanning speech, seizures | Gaze-evoked nystagmus | T2/FLAIR hyperintensities of both cerebellar hemispheres with normal DWI | <0.6 | 7.6 | |

| Rigamonti et al.29 | 74/f | PPI and diarrhea due to levetiracetam | Second | — | Gait ataxia, left dysmetria | — | Irritability | Left-beating nystagmus | T2/FLAIR hyperintensities left > right | <0.29 | |

| Blasco et al.30 | 61/f | TRPM6 mutation | Multiple episodes for 10 y | Kinetic tremors | Trunk and limb cerebellar ataxia | — | Walking imbalance, lower limb weakness and paresthesia, recurrent falls | Horizontal nystagmus | Normal | 1.8 | |

| Boulos et al.31 | 76/m | Bowel resection twice due to adenocarcinoma colon and intestinal obstruction due to adhesion | First | Upper limb tremors | Trunk and limb ataxia | — | Dysarthria, light headedness, ataxia and headache, dysphagia | Nystagmus on lateral gaze | Ill-defined T2 hyperintensity of bilateral cerebellar hemispheres | 0.36 | 6.37 |

| Hammarsten et al.32 | 44/m | Chronic diarrhea secondary to ulcerative colitis | First | Mild generalized tremors, flapping tremors | — | Myoclonic jerks of extremities | Athetosis, confusion followed by stupor | — | — | 1.46 | |

| Matsuyama et al.33 | 64/m | PPI | First | Tremors of upper limbs | — | — | Nausea and dizziness | — | — | 0.2 | 5.8 |

| Bartolini et al.34 | 77/f | Chronic renal failure due to diabetic nephropathy | First | Dysrhythmic limb tremors | — | — | After each episode of DBN, patient became lethargic | Downbeat nystagmus | — | 0.12 | 2.9 |

| Almoussa et al.35, 2018 | 60/m | PPI | First | Rest, postural, intention tremors | Limb and truncal ataxia | — | Vertigo, nausea, dysarthria | Nystagmus | T2/FLAIR hyperintensity of bilateral cerebellar hyperintensity | 0.4 | 6.8 |

| Marse et al.36 | 68/m | Renal hypomagnesemia due to diabetes mellitus type 2 | First | Action tremors of upper limbs and tremor of mandible | — | — | Vertigo, encephalopathy | Downbeat nystagmus in vertical gaze | MRI brain—nonspecific white matter lesion | 0.22 | |

| Turnock et al.37 | 84/m | PPI | First | Multifocal tremors of arms and face | — | — | Cramps, ankle pain, low mood and fatigue. Chvostek sign and Trousseau sign are positive | — | — | 0.36 | 6.33 |

| Baroncini et al.38 | 41/m | PPI, metformin, poor nutritional intake | First | Intermittent limb tremor, titubation | Gait ataxia, upper and lower limb dysmetria | — | Dysarthria, paresthesia, oscillopsia, positive Romberg sign | — | FLAIR hyperintensity of anterior cerebellum and vermis | 0.51 | 7.3 |

| Fernandez et al.39 | 63/m | First | — | Truncal dysmetria and ataxia | — | Confusion, nausea, vomiting | Downbeat nystagmus | Vermis hyperintensity in FLAIR sequences | 0.3 | 7.1 | |

| Uehara et al.40 | 79/f | PPI | First | Resting tremors of hands | — | — | Nausea and vomiting, Trousseau sign is positive | — | 0.48 | 5.7 | |

| Kumar et al.41 | 38/m | PPI | First | — | Trunk and limb cerebellar ataxia | — | Vertigo, vomiting, imbalance while walking, irritability, seizures, short-term memory impairment | Downbeat nystagmus | T2 hyperintensities of the left cerebellar hemisphere | 0.25–0.9 | Normal |

| Regalosti et al.42 | 65/m | PPI | First | — | Gait ataxia | Myoclonic jerks present | Delirium, hallucinations, areflexia | — | 0.5 | 6.3 | |

| Santos et al.43 | 68/f | Cause not known | Second | — | Gait ataxia | — | Paroxysmal vertigo, generalized seizure | Downbeat nystagmus, horizontal nystagmus in all gaze | Flair hyperintensity of cerebellar nodulus | 0.7 | 6.5 |

| Comacchio et al.46 | 78/m | Chronic diverticulitis | Upper limb tremors | Present | — | Dizziness, oscillopsia, nausea, anxiety | Downbeat nystagmus in primary gaze, saccadization of smooth pursuits | CT brain—small vessel ischemia | 0.24 | 7.7 | |

| Hamed et al.47 | 66/f | Intestinal malabsorption secondary to short bowel syndrome | First | — | — | — | Dysphagia, proximal lower limb weakness. Confusion and disorientation | Vertical nystagmus | MRI brain not performed Barium swallow—there was no esophageal peristalsis and pharynx, hypopharynx showed dyskinetic movements |

0.25 | 8.4 |

| Fatuzzo et al.e10 | 65/m | PPI for 20 y | Eighth | — | Truncal ataxia | — | Nausea, vomiting, vertigo, walking imbalance, seizures | Ill-defined, nonenhancing T2 hyperintensity of cerebellar vermis | 0.19 | 7.2 | |

| Bhana et al.e11 | 73/f | PPI | First | — | Bilateral dysmetria, gait ataxia | — | Seizures, confusion, dizziness, nausea, dysarthria, diplopia | Gaze-evoked horizontal nystagmus, vertical and rotatory nystagmus on upward gaze | Normal | <0.23 mg/dL to 0.92 mg/dL | 7.8 |

| Pawlukiewicz et al.e16 | 77/m | PPI, chronic kidney disease | First | Intention tremors | — | — | Nausea | — | Chronic unilateral occipital infarct | 0.6 | 7.4 |

| Te Riele et al.e18 | 60/m | PPI, chronic alcohol consumption, chronic diarrhea | Second | Rest, postural and intention tremor | Limb and trunk ataxia | — | Mild cognitive impairment, severe dysarthria | Nystagmus | Symmetrical FLAIR hyperintensity in bilateral cerebellar hemispheres | 0.4 | 5.6 |

| Epstein et al.e19 | 51/f 80/m |

PPI | First | — | — | — | Carpopedal spasm and spasm of the trunk in both the patients | — | 0.48 | 6.01 |

Abbreviation: PPI = proton pump inhibitor.

Tremors

Tremors are generally postural and intentional and most commonly seen over upper limbs but can be generalized.32,33 These can have a jerky, irregular quality27,34 or have a flapping quality due to large amplitude of tremors.32 Rest tremors35 and acute onset of action tremors have been reported in the upper limb, the lower limb, and over the mandible.36,37 Tremors may be seen in association with cerebellar ataxia or in isolation.36 Acute tremors without ataxia have been reported in hypomagnesemia with normal serum calcium levels.36 Titubation in the form of no-no head tremor has also been observed.38

Myoclonus

Twitching of extremities have been reported in earlier studies.32 Myoclonic jerks can be observed in extremities and can persist during sleep,32 although it can be also seen in the face.27 Exaggerated startle reaction has also been noted.11

Tetany

Tetany can be mild in the form of intermittent stiffening of limbs39 or manifest in the form of presence of carpopedal spasm.4 The diagnosis of tetany is based on spasm of the extremities and facial muscles and the presence of laryngeal stridor. Carpopedal spasm can be observed even without signs of frank tetany.10 Latent tetany is diagnosed by the presence of positive Chvostek and Trousseau sign.4,40 In hypomagnesemia, Chvostek sign can be seen without concurrent presence of Trousseau sign or carpopedal spasm.11,27 In addition, auditory or mechanical stimulation incites worsening of spasms, indicating hyperresponsiveness to external stimuli.4 The presence of Chvostek sign in hypomagnesemia could be associated with hypocalcemia.11 Both hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia can act in conjunction to cause tetany rather than low calcium being the sole etiology27 because these symptoms have been noted in patients with hypomagnesemia with normal or mildly low calcium levels.4 The presence of hypocalcemia augments the neuromuscular hyperexcitability rendered by hypomagnesemia. Hypomagnesemia must be strongly suspected in a tetany-like syndrome that does not respond to calcium supplementation.

Cognitive Impairment

Somnolence and confusion can be concomitantly seen in hypomagnesemia.16,26 Mental status examination in hypomagnesemia can range from confusion to deep stupor.32 Acute cognitive impairment in these patients could manifest in the form of short-term memory loss.41 Depression, disorientation, and agitation can be associated with visual hallucinations4,41,42 that could be aggravated by the secondary hypocalcemia. There is no correlation between the severity of hypomagnesemia and degree of obtundation.4

Eye Movement Abnormalities

Oscillopsia is frequently reported, most likely due to nystagmus. It may or may not be associated with diplopia.10,27,28 Eye movement abnormalities in association with hypomagnesemia include slowing of horizontal saccades,25 horizontal nystagmus,43,44 and torsional nystagmus that may be isolated or seen in concurrence with downbeat nystagmus (DBN) in primary position.27,36,43,45-47 DBN is perhaps the most characteristic feature of hypomagnesemia. The intermittent appearance of DBN can be a diagnostic clue toward the etiology.26,27,34

Muscle Abnormalities

Hypomagnesemia leads to rhabdomyolysis that elevates creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels in the presence of rapidly progressive proximal limb weakness27 or can remain asymptomatic.25

Pathogenesis of Neurologic Involvement in Hypomagnesemia

Cerebellum is rich in NMDA, a receptor that facilitates transmission of excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and mediates excitotoxicity. Magnesium blocks its action, leading to inhibition of calcium influx through NMDA receptor, thereby reducing excitability. Magnesium depletion causes dysfunction of sodium-potassium ATPase pump, increasing the excitatory effect of glutamate through NMDA receptor activation and altering calcium current in presynaptic and postsynaptic membrane,48 leading to neuronal hyperexcitability.13 Magnesium also stimulates GABA-A chloride channels in the cerebellum,49 and thus, hypomagnesemia causes GABAergic channel dysfunction leading to cerebellar symptoms such as ataxia.

Vertical nystagmus in hypomagnesemia occurs because of dysfunctional GABAergic activity in the Purkinje cells of cerebellum.50 Purkinje cells are a part of vertical gaze circuitry in flocculus and send inhibitory projections to the part of superior vestibular nucleus (SVN) that solely controls the upward eye movement without affecting the fibers controlling the downgaze.e1 Disruption of GABAergic activity in the Purkinje cells leads to disinhibition of the SVN. This results in stimulation of oculomotor fibers supplying superior rectus muscle with subsequent slow upward gaze with corrective fast downgaze.e1

The propensity toward development of cerebellar lesions in severe hypomagnesemia could also be related to the vulnerability of the posterior circulation in terms of cerebral autoregulation.e2 These lesions are similar to clinical and imaging features of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) and preeclampsia. In both these conditions, high blood pressure perturbs the cerebral autoregulation of the blood vessels leading to edema in the territory of posterior circulation.30,31,43 Magnesium is essential in maintaining vascular tone. Severe hypomagnesemia overwhelms vascular endothelial stability and results in elevated intracellular calcium levels that lead to increased contraction and subsequently increased tone.22 Disturbed cerebral autoregulation due to hypomagnesemia causes elevated perfusion pressure leading to cytotoxic damage and endothelial dysfunction with subsequent vasogenic edema.43 Thus, PRES-like lesions in the cerebellum warrant testing of serum magnesium levels.

Magnesium and calcium are known to strongly modulate the excitability of nerve cell.e3 Magnesium influences the nerve excitability by its direct effect on the membrane.e4 Small decrease in extracellular calcium and magnesium concentrations was linked to increased firing and increased spontaneous discharge of action potentials in bursts in CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus.e2 Increased burst firing is also associated with induction of kindling, a vital step in epileptogenesis.e5 Neuronal hyperexcitability may be the underlying cause behind seizures and myoclonus in hypomagnesemia. Neuronal hyperexcitability is associated with cortical myoclonuse6 that has been observed in hypocalcemia.e7 The effect of hypomagnesemia on cognition may be related to the overactivity of NMDA receptors and the effect of low magnesium levels on cholinergic transmission.e8 As a result of hypomagnesemia, the hyperactive NMDA transmission could influence synaptic transmission that disrupts the institution of long-term potentiation integral to learning and memory.e9 In animals, experimental magnesium depletion in the muscles foster changes in the resting transmembrane potential and muscle necrosis that might explain the myopathic changes reported in hypomagnesemia.19

Differential Diagnosis

In view of multiaxial involvement, episodic symptoms and predominant age of involvement among older individuals, an elaborate workup is generally performed before the diagnosis of hypomagnesemia. It had taken many months to years of recurrent symptoms and extensive workup before the accurate etiology could be detected. There have been instances where a patient had several episodes of ataxia, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, unsteadiness that were diagnosed as cerebellar ischemia and cerebral vasculopathy before the etiology of hypomagnesemia was uncovered.e10 The vascular endothelial dysfunction secondary to hypomagnesemia leads to cerebellar edema similar to that seen in PRES.30,31 Immune-mediated diseases including paraneoplastic disease, cerebellitis, and encephalitis are other possible differential diagnoses in view of episodic symptoms that could ameliorate with the administration of steroids because of resolution of parenchymal edema.16 Both hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia can cause a similar clinical feature owing to the propensity to cause neuromuscular irritability.11

Clinical features seen in hypomagnesemia can mimic episodic ataxia type 2.25 Episodic ataxic type 2, a channelopathy due to CACNA1A sequence variant can present with episodes of ataxia, vertigo, and dysarthria lasting for hours. They also have interictal nystagmus and seizures, similar to that seen in hypomagnesemia.30

Magnesium is an essential cofactor for conversion of thiamine into diphosphate and triphosphate esters. Low levels of magnesium may simulate functional thiamine deficiency,e11,e12 leading to signs and symptoms resembling Wernicke encephalopathy.10,38 Vertical nystagmus, more conspicuous with upgaze, has been reported in thiamine deficiency. However, many patients with thiamine deficiency have poor nutritional intake and consume alcohol on a daily basis and have gastritis that would be treated with magnesium containing antacids. Hence, it is possible that these patients with thiamine deficiency have concomitant undetected hypomagnesemia that gets corrected with treatment addressing both thiamine deficiency and gastritis.10 A diagnosis of untreated hypomagnesemia must be kept in mind if a patient with classical presentation of Wernicke encephalopathy fails to optimally respond to thiamine.

The presentation of hypomagnesemia among the older individuals, multiaxial nature of symptoms (eye signs, cognitive changes, movement disorders, and myopathy), and relapsing-remitting symptoms with residual deficits recurring over years makes the diagnosis of paraneoplastic or autoimmune etiology as the first consideration. Moreover, cerebellar hyperintensities mimicking PRES or encephalitis/cerebellitis further directs the clinical intuition toward a metabolic etiology. A high index of suspicion for a diagnosis of hypomagnesemia needs to be maintained if the symptoms are episodic and are associated with movement disorders and DBN.

Imaging

MRI of the brain shows poorly defined T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in unilateral or bilateral31,41 cerebellar hemispheres that showed increased signal in diffusion-weighted sequences and ADC map consistent with vasogenic edema.25,28 Sulcal effacement can also be seen.31 The cerebellar hemispheric swelling can be severe enough to cause distortion of fourth ventricle and hydrocephalus,28 necessitating craniectomy.18 Hyperintensities have also been observed in the vermis, in the region of nodulus.26,43 Unilateral cerebellar clinical involvement has been observed with bilateral cerebellar edema.9 None of these individuals had accelerated hypertension, sepsis, autoimmune condition, or elevated creatinine or were on medication that are associated with PRES. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) showed low levels of N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) indicative of neuronal loss.25,31 Follow-up MRI after correction of hypomagnesemia can show focal cerebellar atrophy.25 Mild cerebellar vermis atrophy has been detected in autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia with renal wasting.e13 MRI of the brain can also be normal despite severe symptoms.27

Diagnosis of Hypomagnesemia

Hypomagnesemia is defined as serum magnesium levels below 0.66 mmol/L or 1.7 mg/dL.e14 Hypomagnesemia is underrecognized because the etiologic factors often lead to concurrent issues such as fever, sepsis, dyselectrolytemia, hyposmolality, or liver disease.11,21 In a study, in all the patients who exhibited neurologic impairment, magnesium levels were critically low (less than 1.3 mg/dL).16 Neurologic examination of patients with mild hypomagnesemia (1.3–1.7 mg/dL) showed no deficits.11 In a study of 22 patients with hypomagnesemia secondary to cisplatin treatment, patients with symptoms secondary to hypomagnesemia (tremors, cramps, muscle twitching) had magnesium levels lower than 1 mEq/L.e15 However, in our review, although 88.3% patients had critically low magnesium levels, recurrent ataxia and movement disorders were noted in a patient with serum magnesium levels up to 1.8 mg/dL30 that could be attributed to her TRPM6 mutation. Thus, mild hypomagnesemia very rarely can be associated with movement disorders. Although serum magnesium levels are a poor indicator of body stores, it is likely that the low body magnesium stores are reflected as hypomagnesemia resulting in clinical manifestations because dilutional hypomagnesemia does not lead to neurologic symptoms.11

Hypomagnesemia is associated with hypokalemia, hypocalcemia,25 and rhabdomyolysis.25 Parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels can be low27 or elevated,25,43,e16 secondary to PTH resistance. Magnesium deficiency impairs the mobilization of calcium from the bone leading to hypocalcemia. Furthermore, it decreases the end-organ response toward PTH leading to PTH resistance and affects the secretion of PTH.e17

CSF analysis is generally performed to rule out other causes of ataxia. CSF analysis is normal in hypomagnesemia.38,39 Further evaluation is performed to ascertain the etiology of hypomagnesemia that include urinary magnesium loss, urine chloride, and arterial blood gas analysis. Once the source of magnesium depletion is ascertained (decreased intake or renal or gastrointestinal loss), further testing to determine etiology is taken up.

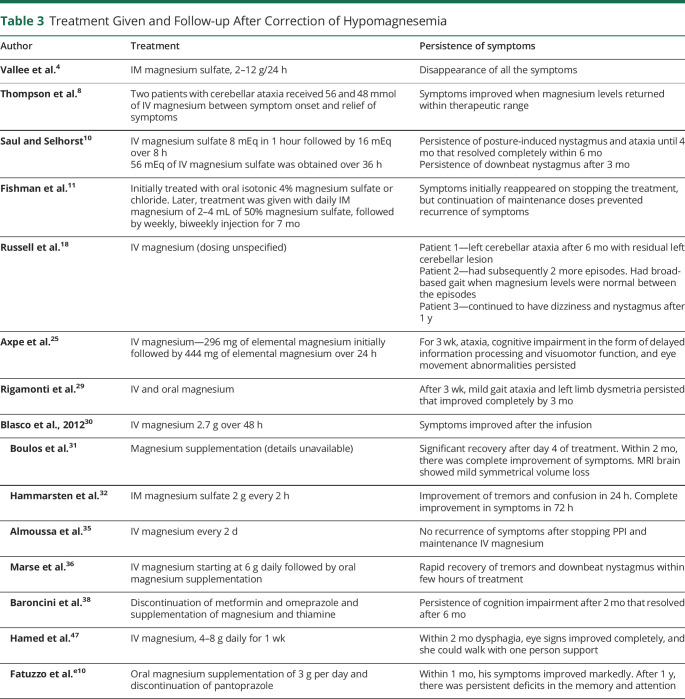

Clinical Course of Hypomagnesemia

With improvement in serum magnesium levels, the lesions resolve completely in some patients,31 while in others, the imaging abnormalities persist despite normalization of serum magnesium levels.25 Although rapid recovery of symptoms is generally seen after IV magnesium administration,26 the neurologic deficits can persist long after correction of serum magnesium levels.25 Residual symptoms can include oscillopsia, diplopia on downgaze, gait imbalance,10 and dysarthria. Dizziness aggravating with supine position has also been reported.10 Symptoms continue to persist up to 3–6 months and even up to 4 years after correction of serum magnesium levels (Table 3).28 Cognition assessment in these patients at follow-up after 2 months revealed slowed processing of information,25,38 defects in visual-motor activity,25 and visuospatial and verbal memory.38 The residual deficits in the form of gait ataxia and nystagmus were noted in up to 50% of patients28 in one study describing the cerebellar syndrome in hypomagnesemia, while in our review, 27.27% of patients had residual deficits at follow-up.

Table 3.

Treatment Given and Follow-up After Correction of Hypomagnesemia

| Author | Treatment | Persistence of symptoms |

| Vallee et al.4 | IM magnesium sulfate, 2–12 g/24 h | Disappearance of all the symptoms |

| Thompson et al.8 | Two patients with cerebellar ataxia received 56 and 48 mmol of IV magnesium between symptom onset and relief of symptoms | Symptoms improved when magnesium levels returned within therapeutic range |

| Saul and Selhorst10 | IV magnesium sulfate 8 mEq in 1 hour followed by 16 mEq over 8 h 56 mEq of IV magnesium sulfate was obtained over 36 h |

Persistence of posture-induced nystagmus and ataxia until 4 mo that resolved completely within 6 mo Persistence of downbeat nystagmus after 3 mo |

| Fishman et al.11 | Initially treated with oral isotonic 4% magnesium sulfate or chloride. Later, treatment was given with daily IM magnesium of 2–4 mL of 50% magnesium sulfate, followed by weekly, biweekly injection for 7 mo | Symptoms initially reappeared on stopping the treatment, but continuation of maintenance doses prevented recurrence of symptoms |

| Russell et al.18 | IV magnesium (dosing unspecified) | Patient 1—left cerebellar ataxia after 6 mo with residual left cerebellar lesion Patient 2—had subsequently 2 more episodes. Had broad-based gait when magnesium levels were normal between the episodes Patient 3—continued to have dizziness and nystagmus after 1 y |

| Axpe et al.25 | IV magnesium—296 mg of elemental magnesium initially followed by 444 mg of elemental magnesium over 24 h | For 3 wk, ataxia, cognitive impairment in the form of delayed information processing and visuomotor function, and eye movement abnormalities persisted |

| Rigamonti et al.29 | IV and oral magnesium | After 3 wk, mild gait ataxia and left limb dysmetria persisted that improved completely by 3 mo |

| Blasco et al., 201230 | IV magnesium 2.7 g over 48 h | Symptoms improved after the infusion |

| Boulos et al.31 | Magnesium supplementation (details unavailable) | Significant recovery after day 4 of treatment. Within 2 mo, there was complete improvement of symptoms. MRI brain showed mild symmetrical volume loss |

| Hammarsten et al.32 | IM magnesium sulfate 2 g every 2 h | Improvement of tremors and confusion in 24 h. Complete improvement in symptoms in 72 h |

| Almoussa et al.35 | IV magnesium every 2 d | No recurrence of symptoms after stopping PPI and maintenance IV magnesium |

| Marse et al.36 | IV magnesium starting at 6 g daily followed by oral magnesium supplementation | Rapid recovery of tremors and downbeat nystagmus within few hours of treatment |

| Baroncini et al.38 | Discontinuation of metformin and omeprazole and supplementation of magnesium and thiamine | Persistence of cognition impairment after 2 mo that resolved after 6 mo |

| Hamed et al.47 | IV magnesium, 4–8 g daily for 1 wk | Within 2 mo dysphagia, eye signs improved completely, and she could walk with one person support |

| Fatuzzo et al.e10 | Oral magnesium supplementation of 3 g per day and discontinuation of pantoprazole | Within 1 mo, his symptoms improved markedly. After 1 y, there was persistent deficits in the memory and attention |

Hypomagnesemia can be episodic if the underlying cause remains uncorrected. Recurrent episodes are not without repercussions. Brain imaging in follow-up showed neuronal loss as evident by low NAA levels25,31 in addition to structural cerebellar volume loss.31

Treatment

Given the fact that magnesium is predominantly an intracellular ion, the degree of depletion of body stores of magnesium may not be entirely reflected in the serum magnesium levels. Prolonged magnesium supplementation in either parenteral or oral mode is essential to prevent recurrence.e18 With neurologic manifestations, oral magnesium supplementation alone may fail to replenish the body magnesium stores, and there is a risk of reemergence of symptoms after transient improvement.16 Treatment with oral magnesium may normalize the serum magnesium levels without achieving adequate alleviation of neurologic deficits.25 It is prudent that magnesium is repleted using IV magnesium because IV magnesium has been found to rapidly improve symptoms and correct the critically low magnesium levels.16

The dose of IV magnesium ranges from 2 to 12 g per day (Table 3). Monitoring of serum magnesium enables titration of IV magnesium dose.23,27 For preventing recurrent episodes of hypomagnesemia, the mode and duration of treatment is variable, and maintenance treatment with intermittent IV magnesium or oral magnesium supplementation has been tried. To prevent recurrences, maintenance dose of IV magnesium 1 gm every two days for more than two months have been tried.e18 Hypomagnesemia secondary to PPI intake fails to correct with oral magnesium intake and only responds to IV magnesium replacement.16 Cessation of intake of PPI is also necessary for restoration of serum magnesium levels18 that improves few weeks after discontinuation of PPI.13,e19

Acute changes in serum magnesium levels may not lead to corresponding changes in serum calcium19 implying the fact that it is the intracellular magnesium that governs the calcium homeostasis and subsequently calcium levels in the body.19,25 Hypocalcemia secondary to hypomagnesemia may fail to correct with conventional calcium correction. This hypocalcemia will normalize only if the underlying hypomagnesemia is corrected.25,27

The review has limitations inherent to consideration of multiple isolated case reports and case series for analysis such as missing data and heterogeneity in description of clinical presentation and follow-up information. We have not included studies describing the genetic or familial causes of hypomagnesemia because the mutations can have wide phenotypic expression that extend beyond the clinical presentation of hypomagnesemia alone.

Hypomagnesemia as the etiology of acute-onset movement disorders may be more common than reported. Ataxia and tremors are commonest movement disorders associated with hypomagnesemia while myoclonus, chorea, and athetosis are rare manifestations. Neuronal hyperexcitability such as carpopedal spasm, tetany, seizures, vertigo, vomiting, and mental status changes are other neurologic features. PPI are widely used by individuals worldwide and for many years by some individuals, making it even more likely that hypomagnesemia and the neurologic complications are prevalent but underdiagnosed in view of the presentation being similar to PRES, cerebellitis, ischemia, or vasculopathy. Recurrent episodes of hypomagnesemia lead to neuronal damage and residual motor and cognitive deficits making it imperative to maintain a high degree of suspicion for early detection of this verily treatable condition.

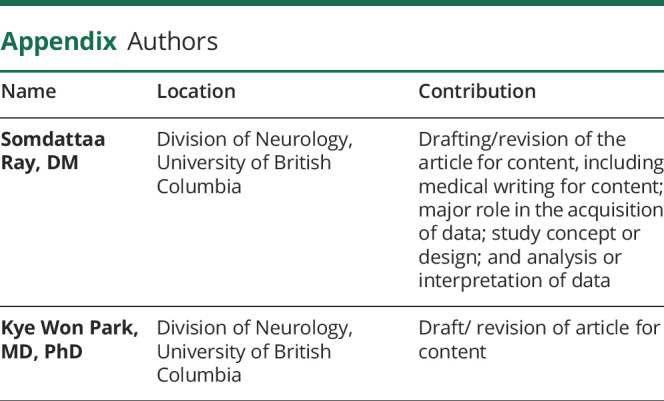

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Somdattaa Ray, DM | Division of Neurology, University of British Columbia | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Kye Won Park, MD, PhD | Division of Neurology, University of British Columbia | Draft/ revision of article for content |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ The widespread use of PPI, similarity of clinical picture with cerebellitis and PRES, makes the prevalence of hypomagnesemia-induced neurologic symptoms more common than reported.

→ Hypomagnesemia is associated with a myriad of movement disorders, commonest being ataxia and tremors. Myoclonus, athetosis, and chorea have also been reported.

→ Other neurologic symptoms associated with hypomagnesemia include vertigo, nausea, cognitive impairment, tetany, dysphagia, proximal muscle weakness, and downbeat nystagmus.

→ If untreated, hypomagnesemia runs a chronic course with recurrent episodes that leads to residual neurologic deficits.

→ Hypomagnesemia must be suspected in the context of episodic movement disorders, altered mental status, vertigo, and muscle weakness with downbeat nystagmus.

References

- 1.Goraya JS. Acute movement disorders in children: experience from a developing country. J Child Neurol. 2015;30(4):406-411. doi: 10.1177/0883073814550828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiménez-Ruiz A, García-Grimshaw M, Vigueras-Hernández A, Reyes-Melo I. Hemiballismus as a presenting feature of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism in the emergency department. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020;11(4):e592-e593. doi: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girija MS, Yadav R, Nalini A, et al. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome presenting with unique craniofacial involuntary movements. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(6):e909-e910. doi: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000001004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallee BL, Wacker WE, Ulmer DD. The magnesium-deficiency tetany syndrome in man. N Engl J Med. 1960;262(4):155-161. doi: 10.1056/nejm196001282620401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin KJ, González EA, Slatopolsky E. Clinical consequences and management of hypomagnesemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(11):2291-2295. doi: 10.1681/asn.2007111194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whang R, Ryder KW. Frequency of hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia: requested vs routine. JAMA. 1990;263(22):3063-3064. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.22.3063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirschfelder AD, Haury VG. Clinical manifestations of high and low plasma magnesium: dangers of epsom salt purgation in nephritis. J Am Med Assoc. 1934;102(14):1138-1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.1934.02750140024010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson C, Sullivan K, June C, Thomas E. Association between cyclosporin neurotoxicity and hypomagnesaemia. Lancet. 1984;324(8412):1116-1120. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91556-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gokalp C, Cetin C, Bedir S, Duman S. Gitelman syndrome presenting with cerebellar ataxia: a case report. Acta Neurol Belgica. 2020;120(2):443-445. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saul RF, Selhorst JB. Downbeat nystagmus with magnesium depletion. Arch Neurol. 1981;38(10):650-652. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510100078014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishman RA. Neurological aspects of magnesium metabolism. Arch Neurol. 1965;12(6):562-569. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1965.00460300010002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(suppl 1):i3-i14. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):1-46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leicher CR, Mezoff AG, Hyams JS. Focal cerebral deficits in severe hypomagnesemia. Pediatr Neurol. 1991;7(5):380-381. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(91)90070-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell WW, DeJong RN. DeJong's the Neurologic Examination. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamm CP, Nyffeler T, Henzen C, Fischli S. Hypomagnesemia-induced cerebellar syndrome—a distinct disease entity? Case report and literature review. Front Neurol. 2020;11:968. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flink E, Stutzman F, Anderson A, Konig T, Fraser R. Magnesium deficiency after prolonged parenteral fluid administration and after chronic alcoholism complicated by delirium tremens. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;43(2):169-183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross Russell A, Prevett M, Cook P, Barker CS, Pinto AA. Reversible cerebellar oedema secondary to profound hypomagnesaemia. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(4):311-314. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pall H, Williams A, Heath D, Sheppard M, Wilson R. Hypomagnesaemia causing myopathy and hypocalcaemia in an alcoholic. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63(742):665-667. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.63.742.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlingmann KP, Konrad M. Magnesium homeostasis. Principles of Bone Biology. Elsevier; 2020:509-525. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasina L, Zanotta D, Puricelli S, Bonoldi G. Acute neurological symptoms secondary to hypomagnesemia induced by proton pump inhibitors: a case series. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(5):641-643. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sontia B, Touyz RM. Role of magnesium in hypertension. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;458(1):33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray S, Srijithesh PR, Kulkarni G, Alladi S. Prolonged magnesium sulphate infusion in the management of super refractory status epilepticus in a probable anti GABA- B autoimmune encephalitis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2019;22(suppl 1):S45-S157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Castillo J, Engbaek L. The nature of the neuromuscular block produced by magnesium. J Physiol. 1954;124(2):370-384. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rouco Axpe I, Almeida Velasco J, Barreiro Garcia JG, Urbizu Gallardo JM, Mateos Goñi B. Hypomagnesemia: a treatable cause of ataxia with cerebellar edema. Cerebellum. 2017;16(5-6):988-990. doi: 10.1007/s12311-017-0873-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sedehizadeh S, Keogh M, Wills AJ. Reversible hypomagnesaemia-induced subacute cerebellar syndrome. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;142(2):127-129. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8757-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray S, Kamath VV, Jadhav SR, Rajesh KN. Hypomagnesemia‐a rare cause of movement disorders, myopathy and vertical nystagmus. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2023;10(6):1001-1003. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olmedo‐Saura G, Pérez‐Pérez J, Xuclà‐Ferrarons T, Collet R, Martínez‐Viguera A, Kulisevsky J. Cerebellar syndrome induced by hypomagnesemia: a treatable cause of ataxia not to be missed. Report of three cases and a review of the literature. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2023;10(6):1004-1012. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrea R, Vittorio M, Giuseppe L, Paola B, Andrea S. Reversible cerebellar MRI hyperintensities and ataxia associated with hypomagnesemia: a case report with review of the literature. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(4):961-963. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04081-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blasco LM. Cerebellar syndrome in chronic cyclic magnesium depletion. Cerebellum. 2013;12(4):587-588. doi: 10.1007/s12311-012-0431-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulos MI, Shoamanesh A, Aviv RI, Gladstone DJ, Swartz RH. Severe hypomagnesemia associated with reversible subacute ataxia and cerebellar hyperintensities on MRI. Neurologist. 2012;18(4):223-225. doi: 10.1097/nrl.0b013e31825bbf07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammarsten JF, Smith WO. Symptomatic magnesium deficiency in man. N Engl J Med. 1957;256(19):897-899. doi: 10.1056/nejm195705092561907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuyama J, Tsuji K, Doyama H, et al. Hypomagnesemia associated with a proton pump inhibitor. Intern Med. 2012;51(16):2231-2234. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartolini E, Sodini R, Nardini C. Acute-onset vertical nystagmus and limb tremors in chronic renal failure. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(1):e13-e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almoussa M, Goertzen A, Brauckmann S, Fauser B, Zimmermann CW. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to hypomagnesemia: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:1-6. doi: 10.1155/2018/1980638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marse C, Druesne V, Giordana C. Paroxysmal tremor and vertical nystagmus associated with hypomagnesemia. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(suppl 3):S61-S62. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turnock M, Pagnoux C, Shore K. Severe hypomagnesemia and electrolyte disturbances induced by proton pump inhibitors. J Dig Dis. 2014;15(8):459-462. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baroncini D, Annovazzi P, Minonzio G, Franzetti I, Zaffaroni M. Hypomagnesaemia as a trigger of relapsing non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy: a case report. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(11):2069-2071. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3062-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collía Fernández A, Huete Antón B, García-Moncó JC. Progressive ataxia and downbeat nystagmus in an adult. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(8):1018-1019. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uehara A, Kita Y, Sumi H, Shibagaki Y. Proton-pump inhibitor-induced severe hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia are clinically masked by thiazide diuretic. Intern Med. 2019;58(15):2201-2205. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2608-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar SS, Khushbu G, Dev MJ. Hypomagnesaemia induced recurrent cerebellar ataxia: an interesting case with successful management. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2020;7(1):1-3. doi: 10.1186/s40673-019-0110-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regolisti G, Cabassi A, Parenti E, Maggiore U, Fiaccadori E. Severe hypomagnesemia during long-term treatment with a proton pump inhibitor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(1):168-174. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos AF, Sousa F, Rodrigues M, Ferreira C, Soares-Fernandes J, Maré R. Reversible cerebellar syndrome induced by hypomagnesemia. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2015;3(5):190-191. doi: 10.1111/ncn3.183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enríquez DR, Sirvent A, Amoros F, Martínez M, Cabezuelo JB, Reyes A. Renal hypomagnesemia, hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis in a middle-aged man. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37(1):93-95. doi: 10.1080/00365590310008802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du Pasquier R, Vingerhoets F, Safran AB, Landis T. Periodic downbeat nystagmus. Neurology. 1998;51(5):1478-1480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comacchio F, Markova V, Accordi D, et al. Primary downbeat spontaneous nystagmus and severe Hypomagnesemia. Monit Follow-Up. 2015;2:2-7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamed IA, Lindeman RD. Dysphagia and vertical nystagmus in magnesium deficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):222-223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-2-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris M. Brain and CSF magnesium concentrations during magnesium deficit in animals and humans: neurological symptoms. Magnesium Res. 1992;5(4):303-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poleszak E. Benzodiazepine/GABAA receptors are involved in magnesium-induced anxiolytic-like behavior in mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(4):483-489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glasauer S, Stephan T, Kalla R, Marti S, Straumann D. Up–down asymmetry of cerebellar activation during vertical pursuit eye movements. Cerebellum. 2009;8(3):385-388. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0109-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- eReferences are available at; links.lww.com/CPJ/A467.