Abstract

Communicators frequently make adjustments to accommodate receivers’ characteristics. One strategy for accommodation is to enhance the relevance of communication for receivers. The current work uses information targeting—a communication strategy where information is disseminated to audiences believed to experience heightened risk for a health condition—to test whether and why targeting health information based on marginalized racial identities backfires. Online experimental findings from Black and White adults recruited via MTurk (Study 1) and Prolific Academic (Study 2) showed that Black Americans who received targeted (vs. nontargeted) health messages about HIV or flu reported decreased attention to the message and reduced trust in the message provider. White Americans did not differentially respond to targeting. Findings also demonstrated that (a) these negative consequences emerged for Black Americans due to social identity threat, and (b) these consequences predicted downstream cognitive and behavioral responses. Study 2 showed that these consequences replicated when the targeting manipulation signaled relevance directly via marginalized racial identities. Collectively, findings demonstrate that race-based targeting may lead to overaccommodation, thus precluding the expected benefits of relevance.

Keywords: health communication, information targeting, social identity threat, communication accommodation theory, relevance

Understanding whether and why certain communication strategies fail to effectively engage Black receivers has been a key concern among communication scholars for decades. These questions remain critical because within the United States, Black Americans experience worse health outcomes than White Americans across numerous metrics (CDC, 2016). Moreover, Black Americans are disproportionately burdened by a myriad of health conditions, such as HIV, where Black Americans account for over 40% of new HIV infections (CDC, 2022). To mitigate these disparities, many health campaigns and prevention efforts have leveraged communication interventions to address several facets of healthcare (e.g., enhancing knowledge of disease prevention and reducing engagement in behaviors that increase risk). Although many of these interventions have been specifically designed to engage Black receivers, racial disparities persist.

Communicators frequently rely on a broad range of strategies to select and disseminate health information. For example, to convey risk and motivate behavior change for population subgroups that are disproportionately affected by certain health conditions, communicators may adapt their communication by leveraging strategies such as information targeting. Information targeting is a communication strategy that relies on group-level data to customize health information, and targeting intends to reach a particular population subgroup based on characteristics presumed to be shared by group members (e.g., audiences believed to be at heightened risk for a health condition; Davis & Resnicow, 2012; Kreuter & Wray, 2003). However, communication that incorporates aspects of receivers’ marginalized identities (e.g., their race) may have unintended consequences. Indeed, Black Americans who perceive racially biased treatment in health contexts report greater distrust, reduced adherence to recommendations, and decreased engagement with health services (Adegbembo et al., 2006; Haywood et al., 2014; Musa et al., 2009). Therefore, although information targeting intends to reduce gaps in information accessibility and facilitate persuasion (i.e., attitude and behavior change), we theorize that Black Americans who perceive racial biases in information exchange may disengage from the information and information provider (Kreuter et al., 2003; Kreuter & Wray, 2003). This notion is supported by previous theorizing and empirical research on overaccommodation, a context in which communicators’ attempts to engage receivers are perceived to be excessive and can inadvertently undermine communication effectiveness (Giles & Gasiorek, 2013). To test this possibility, the current work investigates how Black (vs. White) Americans respond to targeted health information and examines why targeting based on racial identity might be more consequential for some groups (Black Americans) relative to others (White Americans). Importantly, the hypothesized negative effects for Black Americans are not attributable to racial differences; rather, we theorize that they are the result of race-based stigmatization within U.S. contexts that disproportionately activates concerns about being devalued among Black individuals.

Accommodating receiver characteristics

To enhance communication, communicators may adapt messages to be consistent with receivers’ values, attitudes, beliefs, and/or social identities (Giles & Ogay, 2007). Communication Accommodation Theory provides a framework for predicting and explaining why, when, and how people adjust their communication during social interactions, as well as the implications of these adjustments (Gallois et al., 2005; Giles & Smith, 1979). Specifically, this theory contends that depending on a communicator’s motivations and perceptions (e.g., affiliation or interpersonal goals), they may make adjustments to their communicative behavior when engaging their communication partner. For example, a physician communicator may eliminate medical jargon from their speech to facilitate comprehension and enhance communication with a patient (Street Jr., 2003). Communicators who adequately accommodate the receiver’s characteristics (e.g., do not make too few or excessive accommodations) are more likely to communicate effectively (Gallois et al., 2005).

One strategy for accommodation is to enhance the relevance of communication for receivers. For example, when people communicate with someone who does not share their racial or ethnic identity, they tend to select conversation topics that they believe to be culturally relevant (e.g., cultural traditions; Harwood et al., 2006). The benefits of leveraging relevance have been well established in prior research. Indeed, personally relevant messages are more persuasive than irrelevant messages (Liberman & Chaiken, 1996; Petty et al., 1981), and perceiving message relevance has been linked with greater attention to self-relevant stimuli, increased information encoding and recall, more favorable perceptions of the message source, and stronger approach behavior towards health goals (Bargh, 1982; Kalichman & Coley, 1995; Kreuter & Wray, 2003; Petty & Cacioppo, 1979; Rotliman & Schwarz, 1998). One reason why relevance facilitates persuasion is because it can encourage elaboration of the message. For example, the Elaboration Likelihood Model posits that perceived relevance will increase the receiver’s motivation to process the message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Thus, attending to relevant messages should elicit high elaboration. In contexts where the message is evaluated positively, participants should report more (positively valenced) thoughts, fewer unrelated thoughts (an index of inattention), and perform better on recall and recognition tasks (Petty & Brinol, 2011). Although elaborating on weak or threatening messages can undermine persuasion, high elaboration under more favorable conditions should result in enduring attitude change (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986).

Because perceived personal relevance is believed to be a central tenet of persuasion, many communication strategies leverage relevance to facilitate persuasion. For instance, information targeting conveys relevance by incorporating aspects about the recipient, such as their demographics, goals, values, or behaviors, into the message content (Kreuter & Wray, 2003). Moreover, receivers can perceive targeting on multiple levels; whereas some forms of targeting focus on shared characteristics, such as attitudes or values (deep structure targeting), other forms of targeting rely on more superficial characteristics, such as membership in a particular social group (surface structure targeting; Resnicow et al., 1999).

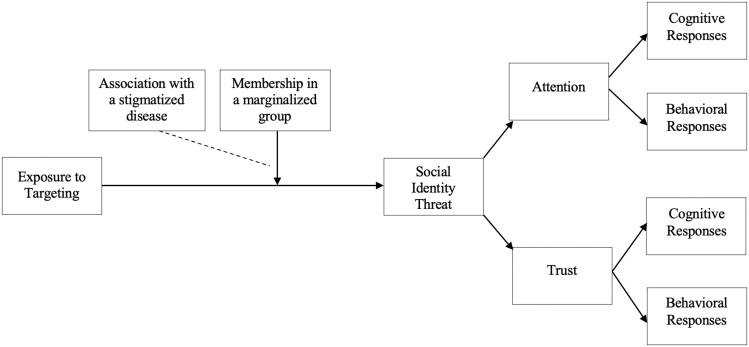

Given the well-established relationship between relevance and positive outcomes, one expectation is that targeting may reduce racial gaps in healthcare access and enhance engagement by ensuring that audiences believed to be at heightened risk receive and attend to pertinent health information (Barrera Jr. et al., 2013; Kreuter et al., 2003). However, we propose that there are limits to the effectiveness of targeting. In particular, we anticipate that exposure to targeted messages designed to reach marginalized audiences may undermine the persuasiveness of the message when these efforts are perceived as overaccommodation. Therefore, we theorize that (a) targeting information based on social identities will impede receptivity when the receiver belongs to a marginalized racial group, and (b) these effects will be exacerbated when the communication being associated with the receiver’s social group is stigmatizing (e.g., a stigmatized health condition; see Figure 1). Moreover, we predict that (c) these communication efforts are likely to backfire due to receivers’ experiences of social identity threat.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model underlying the research question and study outcomes.

Unintended consequences of leveraging relevance based on marginalized identities

Although communicators’ use of accommodations is often beneficial, receivers may respond negatively when they perceive these efforts to be excessive (Giles & Gasiorek, 2013). Overaccommodation refers to a situation in which communication behavior is believed to exceed the level of accommodation needed for a successful interaction (Coupland et al., 1988). Communicators may overaccommodate in several ways, including adapting communication for receivers based on stereotypes or overgeneralized beliefs about their social group (e.g., perceiving older adults or persons living with a disability as having limited abilities; Fox et al., 2000; Mustajoki, 2013; Ryan et al., 1986). For example, when medical students communicate with patients living with a disability, they use overaccommodative behaviors such as oversimplifying technical terms, making negatively framed assumptions about their relationships, and responding in ways that are incongruent with receivers’ emotional cues (Duggan et al., 2011). These types of behaviors have demonstrated negative effects for receivers, including reduced relational satisfaction, worse cognitive task performance, and reinforced stereotypes (Colaner et al., 2014; Hehman & Bugental, 2015). Because some forms of targeting rely on race-adapted information selection, we theorize that these instances may represent a communicative behavior that is perceived to be an overaccommodation. That is, receivers may perceive that this method of targeting relies excessively on group-based information without considering receivers as individuals.

Social identity theory offers a theoretical framework to understand whether and why exposure to race-adapted communication may lead to overaccommodation for Black receivers (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986). According to social identity theory, people define their identities based on social categories and derive their sense of self-esteem from these identifications. Consequently, people are motivated to view their group in a positive manner to maintain or enhance their self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Using these principles, previous research has established the ways in which social identity theory informs communication accommodation theory. Communication accommodation theory contends that intergroup relations are a key component of interpersonal interactions and hence, group membership can shape accommodation efforts (e.g., making accommodations based on receivers’ social identities; Colaner et al., 2014; Ryan et al., 1986). Whether accommodations are perceived to be threatening may be determined, at least in part, by recipients’ attributions, or beliefs, about why the accommodation was received (Kelley, 1967). Importantly, the types of attributions people make are often shaped by personal characteristics, such as their past experiences and group membership. For example, due to frequent experiences with discrimination, members of minoritized groups (e.g., Black Americans) show greater vigilance for stigma cues, which can heighten attributions that one’s identity underlies experienced events (Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). Concerns about race-based stigmatization may be especially salient given that the nature of discrimination in U.S. society predisposes racially minoritized individuals to focus more on their race relative to other marginalized identities when evaluating stigma cues (Levin et al., 2002). Therefore, in the context of persuasion, disseminating messages to members of minoritized groups based on salient group-level (vs. individual) characteristics may increase attributions for information selection to a marginalized identity, even when the criteria being used for information selection is ambiguous. These attributions, in turn, can prompt defensive processing due to concerns about the way in which one’s social group is being evaluated (King, 2003).

We predict that concerns about group-based devaluation may be especially salient for Black Americans in health contexts given historical instances of racism (e.g., Tuskegee syphilis experiments) and continued mistreatment in these settings that have cultivated mistrust of the healthcare system (Williamson et al., 2019). However, because White Americans typically do not contend with race-based stigmatization in healthcare settings, we expect that perceiving overaccommodations based on group-level characteristics (e.g., racial identity) is unlikely to elicit these concerns. Therefore, we theorize that communication which signals relevance through marginalized racial identities may result in overaccommodation and undermine persuasion for Black Americans due to social identity threat—experiencing, suspecting, or anticipating being negatively stereotyped or discriminated against based on one’s group membership (Steele et al., 2002). Consistent with this notion, research demonstrates that social identity threat is more likely to emerge for members of minoritized (vs. majority) groups (Steele et al., 2002), and that encountering identity-relevant cues can prompt social identity threat regardless of whether these cues are explicit (e.g., a salient intergroup comparison; Steele & Aronson, 1995) or more subtle (e.g., implied inferiority when encountering a setting with few ingroup members; Murphy et al., 2007).

Given that social identity threat emerges out of concerns that one’s group is being negatively evaluated, we propose that (a) adverse effects of targeting will arise for Black (but not White) receivers, and (b) these consequences will be exacerbated when receivers perceive that they are being associated with stimuli that are stigmatized in society (e.g., a stigmatized health condition). In line with this argument, using non-White, racially homogenous exemplars for stigmatized behaviors (e.g., graphic tobacco warning labels) can prompt concerns about stigma for racially minoritized adults due to perceptions that the labels reinforce stereotypes (Bigman et al., 2016). Although these associations can be novel, some of these associations are already well-established. For instance, statistics show that HIV, a stigmatized health condition, disproportionally affects Black Americans, which has generated negative racial stereotypes associating Black Americans with HIV (Moskowitz et al., 2012). Therefore, we expect that Black receivers’ negative responses to information targeting will be especially pronounced when receiving a message about HIV.

Consequences of experiencing social identity threat

One common consequence of experiencing social identity threat is disengagement from the stereotyped or threatening domain (Davies et al., 2002). Indeed, when individuals encounter communication that evokes concerns about how one’s social group is being evaluated, they may cope with this threat by withdrawing attention (Earl et al., 2016). Although there are several alternative ways that receivers can cope with identity-threatening communication, including counterarguing the message or derogating the message source, many of these approaches often require substantial personal and cognitive resources (e.g., motivation and/or the ability to counterargue; van ‘t Riet & Ruiter, 2013; Wheeler et al., 2007). Consequently, disengagement or avoidance of the identity-threatening stimuli tends to be the most prevalent response because it requires the fewest psychological resources (i.e., is the least taxing to enact and sustain; Earl & Nisson, 2015; van ‘t Riet & Ruiter, 2013; Wheeler et al., 2007). Understanding factors that undermine attention is critical because attention is a necessary step of message reception and can have implications for message yielding, such as retaining content from the message, focusing one’s thoughts on the message content, or adhering to message recommendations (McGuire, 1968).

Experiencing social identity threat also has implications for interpersonal encounters; members of minoritized groups who experience identity threat in health settings report greater reluctance to engage with individuals who are perceived to be prejudiced and are less likely to disclose personal information (Aronson et al., 2013). Relatedly, other work shows that experiencing social identity threat can reduce trust and engagement with the source of the threat (Kahn et al., 2017). Like attention, diminished trust in the message provider can have cascading effects on cognitive and behavioral outcomes; if receivers do not trust the message provider, it is unlikely that they will seek out additional communication from them or engage in behaviors recommended by the provider (Hou & Shim, 2010; Sun et al., 2021).

The current work

Given previous work suggesting that communicators’ attempts to adapt to the receiver can result in overaccommodation and produce deleterious effects, these studies will evaluate whether targeting based on superficial characteristics (e.g., group membership) might serve as a form of overaccommodation and elucidate why this communication strategy prompts negative consequences for Black receivers. Identifying the consequences associated with targeting for Black receivers, as well as the mechanism underlying these effects, offers an important contribution to research focused on understanding the interplay between communication accommodation theory and social identity theory.

Across two studies, this work examines whether and why targeting health messages based on marginalized racial identities might undermine Black Americans’ engagement with such messages. In Study 1, we manipulate perceptions of targeting; thus, we operationalize relevance in the targeting manipulation by telling participants that their demographic information was used as the basis for the message selection. In Study 2, the targeting manipulation operationalizes relevance specifically via marginalized racial identities by modifying the message content to explicitly reference participants’ racial identity.

In Study 1, we hypothesize that perceptions of being targeted based on one’s social identities (e.g., race) will produce decrements in attention and trust for Black Americans, but not White Americans (Hypothesis 1a). Moreover, we expect that Black Americans’ negative responses to targeting will be exacerbated when they receive a message about a stigmatized health condition (HIV) relative to a nonstigmatized health condition (flu; Hypothesis 1b). Because Black and White Americans may have different preexisting baselines for our primary study outcomes due to fundamentally different experiences with the healthcare system (Williamson et al., 2019), we evaluate the effects of targeting by examining within-group comparisons (e.g., comparing means for Black participants across the targeting and control condition, as opposed to comparing means between Black and White participants in the targeting condition). Furthermore, we predict that social identity threat will serve as a mechanism underlying Black Americans’ negative responses to targeting (Hypothesis 2) and that these consequences (i.e., reduced attention and trust) will be associated with downstream cognitive and behavioral responses such as information recognition, reporting unrelated thoughts on a cognitive elaboration task, elaboration of message content, and willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior (Hypothesis 3). In Study 2, we hypothesize that Black Americans’ negative responses to a targeted (vs. nontargeted) message will replicate with a new targeting manipulation that signals relevance specifically via marginalized racial identities (e.g., by modifying the message content to emphasize racial disparities in disease rates; Hypothesis 4).

Study 1

Study 1 had four key aims. First, we examined how Black and White Americans respond to a health message when they perceive that they are being targeted on their social identities (e.g., their race) and assessed whether participants’ responses are moderated by the message content (HIV vs. flu). Furthermore, Study 1 tested whether perceptions of targeting produced negative outcomes for Black Americans due to our hypothesized mechanism: experienced social identity threat. Finally, we examined whether self-report measures for attention and trust predict downstream cognitive and behavioral responses (e.g., whether attention predicts information recognition).

Sample

We recruited 201 White American (48.3% female, 84.1% had at least some college, Mage = 36.30, SDage = 10.90) and 200 Black American adults (62.5% female, 90.5% had at least some college, Mage = 35.40, SDage = 11.00) from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) to complete our experiment. Fifty-nine participants who identified with another racial identity or as multiracial were excluded before data analysis. We excluded participants who identified as multiracial due to (a) the inability to categorize their race for our study aims (e.g., Black–White biracial individuals), and (b) the complexity of which racial identities may be activated by the targeting manipulation, which could directly impact participants’ responses (Shih et al., 1999). Our predetermined target sample size, based on recommendations at the time the data were collected (2018), was 40–50 participants per cell (Simmons et al., 2011). Post-hoc sensitivity analyses in G*Power v.3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) suggested that we could detect an effect size of f = .14 for a between-subjects ANOVA with eight groups and one degree of freedom in the numerator.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of eight conditions in a 2 (Condition: Targeting, Control) × 2 (Race: Black American, White American) × 2 (Information: HIV, Flu) between-subjects design. Participants were told the researchers were interested in testing different ways of presenting health information to the public. Condition was manipulated by (a) the point at which participants reported their personal demographics in the survey, and (b) instructions explaining why participants were receiving the health message. To manipulate perceptions of targeting, participants in the targeting condition reported their demographic information (race, gender, socioeconomic status, and age) at the beginning of the survey and saw instructions that made explicit reference to their provided demographics: “Please evaluate the following information, which was selected for you based on the demographic information provided.” Participants in the control condition were told, “Please evaluate the following information, which was selected for you based on a randomly generated computer algorithm” and reported their demographics at the end of the survey.1 Following the experimental manipulation, participants saw one message about HIV or flu. The message consisted of eight short paragraphs that described the transmission, symptoms, and treatment options associated with either HIV or flu (see Figure 2; Earl et al., 2016). The message did not make any direct references to receivers’ social identities (e.g., their race). That is, the message was identical, regardless of whether participants were in the targeting or control condition.

Figure 2.

Participant messages (Study 1).

We operationalized targeting using this approach to simulate the experience of receiving a message topic that was ostensibly selected based on one’s demographics. Although targeted messages may not be announced as such, we recognized that MTurk participants may be accustomed to providing their demographics in online studies without any implications for the study procedure. Thus, we included explicit instructions about demographics-based targeting to enhance participants’ inferences that they were being targeted. Although these instructions are blatant, this approach is consistent with recent attempts to increase the transparency of targeted appeals in real-world settings (Kim et al., 2019).

After reading the health message, participants responded to items measuring the primary study outcomes. For the sake of parsimony, we include an example item for each measure below and report complete wording for all survey items in the online supplement. Unless noted otherwise, we calculated the mean of the items, with higher scores indicating more of each construct.

Measures

Perceptions of targeting

Participants answered one item on a Likert scale ranging from 1, Strongly disagree, to 5, Strongly agree (“I received these paragraphs due to something specific about me”).

Attention to the health message

Participants completed five items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Not at all, to 9, Very much (e.g., “How much attention did you pay to the paragraphs”; some items adapted from Mrazek et al., 2012; Takahashi & Earl, 2020). Due to a manual error, one of the items (e.g., “While I was reading the [HIV/FLU] paragraphs, my mind was…”) was measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Completely on unrelated concerns, to 7, Completely on the paragraphs. Thus, each of the five items was standardized before being averaged into a scale (α = .84). This error was corrected in Study 2.

Trust in the message provider

Participants completed four items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Not at all, to 9, Very much (e.g., “I trust this research team”; α = .85).

Social identity threat

Participants answered three items regarding their perceptions of being unfairly judged on Likert-type scales ranging from 1, Not at all, to 9, A great deal or Extremely, with response scale labels depending on the question stem (e.g., “To what extent did you feel you received the [HIV/FLU] paragraphs because you were being judged unfairly?”; α = .75).

To assess whether measures for attention and trust predict downstream cognitive and behavioral responses, participants completed additional survey items and tasks. Across outcomes, participants completed items that corresponded with the message they read (HIV or flu). Piloting of these items is reported in the online supplement.

Correlates for attention to the health message

Information recognition. Following the message, participants answered five multiple-choice questions regarding the message content (e.g., “On average, there are more than ____ new HIV infections each year in the United States”; “In order to be effective, antiviral medication should be taken within _____ hours of the onset of flu symptoms”; some items were adapted from Bruder et al., 2008). Participants saw four possible answers for each question, and their accuracy was determined by the number of questions, out of five, answered correctly.

Cognitive elaboration: Proportion of unrelated thoughts. Participants completed a thought-listing task in which they were given 2 minutes to record the thoughts, feelings, and ideas that came to mind while they were reading the message. We conducted and assessed responses to this task using gold-standard instructions and procedures (Cacioppo & Petty, 1981). Participants self-coded the relatedness of each listed thought on a dichotomous scale (1, related thought or 2, unrelated thought). The coding was completed after participants answered the primary study outcomes to prevent their codes from influencing their subsequent survey responses (Schwarz, 2010). Cognitive elaboration was measured using the proportion of thoughts that participants self-coded as being unrelated to the information. We theorized that the proportion of unrelated thoughts would be low when participants are processing the message (i.e., exhibit increased attention to the message; Martin & Hewstone, 2003).

Correlate for trust in the message provider

Source preference for additional health information. At the end of the study, participants were told that they would be reading another health message and were asked, “Would you prefer to receive health information chosen by the research team or health information chosen randomly?” Participants rated the strength of their preference using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Strongly prefer at random, to 6, Strongly prefer research team.

Elaboration of message content and willingness to engage in message-relevant behaviors

Elaboration of message content. Participants completed three items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Strongly disagree, to 7, Strongly agree (e.g., “The HIV information made me think about using condoms”; “The FLU information made me think about washing my hands frequently”). Although one of the items measured elaboration around getting a flu shot (flu condition) or HIV screening (HIV condition), the data were collected during peak flu season (February). As such, we expected that a subset of participants would have already received a flu shot, which would make it difficult to interpret responses to this item. To address this concern, participants only saw this item if they had not received a flu shot or completed HIV screening in the past 6 months. Due to a substantial loss of power from this approach (18.5% of participants), we dropped this item from analyses in Study 1 but retained the item (about HIV screening) in Study 2. The two-item scale showed acceptable reliability (r = .64).

Willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. Participants completed two items asking them to check a box if they (a) wanted to receive a coupon for a message-relevant item (e.g., condoms or hand sanitizer), and (b) wanted information about a nearby location to be screened for HIV or receive a flu shot. Participants who checked the box received the coupon and/or location information, respectively. To measure willingness, we counted the number of times, out of 2, that participants checked a box.

Analytic strategy

We conducted univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) in SPSS v.27.0. We examined the main effects (condition, race, and information) and their two and three-way interactions on the study outcomes to test the hypotheses that (a) Black Americans, but not White Americans, in the targeting (vs. control) condition would show negative responses to the primary study outcomes (e.g., attention and trust) as well as the cognitive and behavioral correlates of attention and trust, and (b) these negative responses would be exacerbated when seeing a message about HIV.

Next, we used Hayes (2018) PROCESS macro v.3.0 to test the proposed mechanism underlying negative outcomes for Black Americans: experienced social identity threat. We expected that being in the targeting (vs. control) condition would elicit social identity threat for Black Americans, but not White Americans. Experiencing social identity threat, in turn, would predict decreases in attention to the message and trust in the message provider. Lastly, we assessed whether attention and trust would predict downstream cognitive and behavioral responses. In particular, we examined whether (a) attention predicted accuracy of information recognition and the proportion of unrelated thoughts reported in the cognitive elaboration task, (b) trust in the message provider predicted participants’ preference to receive additional health information selected by the research team, and (c) attention and trust predicted elaboration of message content, and subsequently, participants’ willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior.

We analyzed this indirect effect using Model 85 with 5,000 bootstrap resamples. Separate models were run for each outcome. For the sake of brevity, we describe the paths of greatest theoretical interest below. Complete reporting of model parameters is presented in the Online Supplementary Material. Because the measure for attention was standardized, we report standardized estimates for the remaining measures to maintain consistency.

Results

Although we hypothesized that Black Americans’ negative responses to targeting would be stronger in response to a message about HIV (vs. flu), analyses showed nonsignificant three-way interactions, suggesting that the observed effects were not moderated by message content. Therefore, all interactions and main effects relevant to the information manipulation are presented in the Online Supplementary Material.

Additionally, neither the main effect of condition nor the Condition × Race interaction were significant for the cognitive and behavioral correlates of attention and trust, and as such, ANOVA analyses for these results are reported in the supplement. Statistical means and standard deviations for the following results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means for the primary study outcomes (Study 1)

| Outcome | Targeting M (SD) | Control M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptions of targeting | ||

| Black American | 2.88 (1.24) | 1.98 (0.98) |

| White American | 2.86 (1.17) | 1.89 (0.89) |

| Attention to message | ||

| Black American | −0.21 (0.89) | 0.11 (0.75) |

| White American | 0.05 (0.72) | 0.06 (0.78) |

| Trust in provider | ||

| Black American | 7.48 (1.39) | 7.62 (1.37) |

| White American | 7.86 (1.15) | 7.68 (1.21) |

| Social identity threat | ||

| Black American | 3.55 (2.20) | 2.11 (1.56) |

| White American | 2.32 (1.58) | 2.10 (1.55) |

Note: The measure for attention is standardized.

Perceptions of targeting

A significant main effect of condition demonstrated that our experimental manipulation was effective, F(1, 392) = 74.69, p <.001, d = .87; participants in the targeting condition (M = 2.87, SD = 1.20) reported stronger perceptions of being targeted than participants in the control condition (M = 1.93, SD = 0.93). Neither the main effect of race, F(1, 392) = 0.24, p = .626, d = .05, nor the Condition × Race interaction were significant, F(1, 392) = .13, p = .721, ηp2 = .000.

Attention to the health message

Findings demonstrated a significant main effect of condition, F(1, 392) = 4.53, p = .034, d = −.22, showing that participants in the targeting condition (M = −0.08, SD = 0.77) were less likely to attend to the health message than participants in the control condition (M = 0.08, SD = 0.82). Moreover, the Condition × Race interaction was significant, F(1, 392) = 4.20, p = .041, ηp2 = .011. Simple effects showed that although Black Americans reported less attention to the health message in the targeting (vs. control) condition, F(1, 392) = 8.73, p = .003, d = −.30, there was a nonsignificant effect of targeting for White Americans, F(1, 392) = 0.00, p = .956, d = −.00. Furthermore, although there was a nonsignificant effect of race within the control condition, F(1, 392) = 0.24, p = .628, d = .05, Black Americans reported less attention to the health message than White Americans within the targeting condition, F(1, 392) = 5.86, p = .016, d = −.24. The main effect of race was not significant, F(1, 392) = 1.85, p = .175, d = −.14.

Trust in the message provider

Neither the main effects of condition, F(1, 393) = 0.03, p = .862, d = .02, race, F(1, 393) = 3.02, p = .083, d = −.18, nor the Condition × Race interaction, F(1, 393) = 1.84, p = .176, ηp2 = .005, were significant.

Social identity threat

A significant main effect of condition, F(1, 393) = 23.67, p < .001, d = .49, indicated that participants in the targeting condition (M = 2.94, SD = 2.01) reported stronger feelings of social identity threat than participants in the control condition (M = 2.11, SD = 1.55). The main effect of race was also significant, F(1, 393) = 12.82, p < .001, d = .36. Thus, Black Americans (M = 2.84, SD = 2.04) reported stronger feelings of social identity threat than White Americans (M = 2.21, SD = 1.56). These main effects were qualified by a significant Condition × Race interaction, F(1, 393) = 12.66, p < .001, ηp2 = .031. Simple effects demonstrated that Black Americans reported stronger feelings of social identity threat in the targeting (vs. control) condition, F(1, 393) = 35.41, p < .001, d = .60. However, there was a nonsignificant effect of targeting on social identity threat for White Americans, F(1, 393) = 0.86, p = .356, d = .09. Furthermore, although there was a nonsignificant effect of race within the control condition, F(1, 393) = 0.00, p = .987, d = .00, Black Americans reported stronger feelings of social identity threat than White Americans within the targeting condition, F(1, 393) = 25.66, p < .001, d = .51.

Testing the mechanism: social identity threat

As reported in ANOVA, a significant Condition × Race interaction showed that Black Americans in the targeting (vs. control) condition reported stronger feelings of social identity threat, which predicted reductions in attention to the health message (Table 2) and decreased trust in the message provider (Table 3). Reduced attention predicted worse recognition of the message content and reporting a greater proportion of unrelated thoughts in the cognitive elaboration task. Decreased trust predicted a stronger preference to receive additional health information that was selected at random (vs. by the research team). Lastly, reductions in attention and trust predicted decreased elaboration of message content, which subsequently predicted reduced willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. The indices of moderated mediation were significant across outcomes and indicated that the indirect effects were significant for Black Americans, but not White Americans.

Table 2.

Mediation analyses: Statistical parameters for primary pathways (via attention; Study 1)

| Tested effect | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target × Race → Social identity threat | 0.14 | 0.04 | [0.06, 0.21] |

| Social identity threat → Attention | −0.39 | 0.05 | [−0.48, −0.30] |

| Information recognition | |||

| Attention → Information recognition | 0.40 | 0.06 | [0.28, 0.52] |

| Target x Race → Information recognition | 0.01 | 0.05 | [−0.08, 0.10] |

| Indirect effect (White Americans) | −0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.01] |

| Indirect effect (Black Americans) | −0.05 | 0.01 | [−0.08, −0.02] |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.08, −0.01] |

| Unrelated thoughts | |||

| Attention → Unrelated thoughts | −0.20 | 0.07 | [−0.33, −0.06] |

| Target x Race → Unrelated thoughts | 0.01 | 0.05 | [−0.08, 0.11] |

| Indirect effect (White Americans) | 0.00 | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.01] |

| Indirect effect (Black Americans) | 0.02 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.05] |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.02 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.05] |

| Willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior | |||

| Attention → Elaboration of content | 0.23 | 0.06 | [0.11, 0.35] |

| Elaboration of content → Message-relevant behavior | 0.30 | 0.05 | [0.19, 0.40] |

| Target x Race → Message-relevant behavior | 0.00 | 0.05 | [−0.09, 0.10] |

| Indirect effect (White Americans) | −0.001 | 0.002 | [−0.004, 0.002] |

| Indirect effect (Black Americans) | −0.008 | 0.003 | [−0.016, −0.003] |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.007 | 0.004 | [−0.016, −0.002] |

Table 3.

Mediation analyses: Statistical parameters for primary pathways (via trust in provider; Study 1)

| Tested effect | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target × Race → Social identity threat | 0.13 | 0.04 | [0.06, 0.22] |

| Social identity threat → Trust | −0.16 | 0.05 | [−0.26, −0.06] |

| Source preference | |||

| Trust → Source preference | 0.29 | 0.06 | [0.17, 0.41] |

| Target x Race → Source preference | −0.07 | 0.05 | [−0.17, 0.03] |

| Indirect effect (White Americans) | −0.00 | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.00] |

| Indirect effect (Black Americans) | −0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.03, −0.00] |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.03, −0.00] |

| Willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior | |||

| Trust → Elaboration of content | 0.30 | 0.05 | [0.19, 0.40] |

| Elaboration of content → Message-relevant behavior | 0.28 | 0.06 | [0.17, 0.38] |

| Target x Race → Message-relevant behavior | 0.01 | 0.05 | [−0.09, 0.10] |

| Indirect effect (White Americans) | −0.001 | 0.001 | [−0.002, 0.001] |

| Indirect effect (Black Americans) | −0.004 | 0.002 | [−0.009, −0.001] |

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.004 | 0.002 | [−0.008, −0.001] |

Summary

Findings demonstrated that our targeting manipulation was effective; participants in the targeting (vs. control) condition reported stronger perceptions of being targeted. Additionally, we found mixed evidence for our primary hypotheses; although Black Americans in the targeting (vs. control) condition reported decreased attention to the message, targeting did not significantly impact their trust in the message provider. As predicted, exposure to targeting produced nonsignificant effects for White Americans across outcomes. In contrast to our hypotheses, responses to the message did not vary as a function of message content (HIV or flu).

Moreover, Study 1 demonstrated that exposure to targeting increased social identity threat among Black (but not White) Americans and provided evidence for social identity threat as a mechanism underlying their negative responses. Specifically, modeling the indirect effect indicated that exposure to targeting predicted reductions in attention and trust via social identity threat, and decrements in attention and trust predicted downstream cognitive and behavioral responses: worse information recognition, reporting more unrelated thoughts in a thought-listing task, a stronger preference to receive additional health information at random, decreased elaboration of message content, and reduced willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior.

Study 2

Study 2 sought to offer further evidence that targeting information specifically via marginalized racial identities backfires. To investigate this aim, we used a different approach to signal targeting—messaging that emphasized racial disparities in disease rates. Study 2 focused specifically on the effects of targeting for Black Americans in response to HIV for three reasons: (a) our previous findings showed nonsignificant effects of targeting for White Americans as well as nonsignificant differences as a function of message content, (b) Black Americans have disproportionately higher rates of new HIV infections, and consequently, there is an increased likelihood that they will encounter race-based targeted HIV messaging in real-world settings, and (c) pilot tests showed that surges in COVID-19 at the time data were collected raised participants’ suspicion that flu messaging was being used as a guise to promote uptake of COVID-19 prevention behaviors.

Sample

A priori power analyses in G*Power V. 3.1 recommended a minimum sample size of 352 participants for a t-test when expecting a small-to-medium effect size (d = 0.30), 80% power, and α = 0.05. Our proposed effect size was informed by the effect sizes obtained in a separate pilot study using this manipulation (see Online Supplementary Material for details). We over-recruited participants to ensure sufficient power and account for exclusions.

We recruited 381 Black Americans to complete our study through Prolific Academic (70.1% female, 85.3% had at least some college, Mage = 32.19, SDage = 12.55). Before data analysis, we excluded 19 participants: 18 participants who were identified as multiracial (n = 16) or with a race other than Black (n = 2), and 1 participant who did not report reading information about HIV. Data were collected in 2021.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: targeting or control.

The study procedure generally followed the procedure used in the previous study. Participants in the targeting condition provided their demographics (race, age, gender, and socioeconomic status) and were told that they were receiving HIV information due to their demographics. To determine whether negative responses to targeting arise from leveraging relevance specifically via marginalized racial identities, we used another approach that is commonly employed to signal targeting—modifying the message content to emphasize racial disparities in HIV rates. Thus, participants saw one message that consisted of nine short paragraphs (Figure 3). In the targeting condition, we adapted the HIV message from the previous study by providing statistics about racial disparities in HIV infection rates within the United States (e.g., Black Americans are disproportionately affected by HIV), and identifying factors, such as lack of access to trusted doctors, that can contribute to these disparities. Participants in the control condition read an HIV message that provided statistics about the prevalence of HIV among Americans broadly and identified factors, such as failure to discuss sexual behavior with doctors, that contribute to HIV prevalence. Participants in the control condition reported their demographics at the end of the study.

Figure 3.

Participant messages (Study 2).

Measures

As in the previous study, participants reported their (a) perceptions of targeting, (b) attention to the message (α = .90), and (c) trust in the message provider (α = .90). As described below, we made a few changes to the measures used in Study 1 to improve construct validity and to minimize the number of study tasks.

As in Study 1, participants responded to items measuring social identity threat. To address concerns that this measure did not directly assess perceptions of racial discrimination, we included two additional items (e.g., “I received the HIV paragraphs due to racial discrimination”; adapted from Major et al., 2003). Although the reported results use the new, 5-item version of the measure (α = .93), all reported findings replicate when using the 3-item version.

Additionally, participants responded to the items used in Study 1 to measure cognitive and behavioral correlates of attention and trust. However, participants no longer completed the cognitive elaboration task to minimize the number of tasks required by the study. Furthermore, although reliability for the elaboration of message content measure was low (α = .60), conducting analyses with the items separately produced the same results as analyses using the scale. To streamline reporting of results, we retained the scale.

Finally, we included several new measures for this study. To assess whether participants were sensitive to our novel targeting manipulation, participants completed an additional manipulation check measure. We also measured additional outcomes, such as negative emotional responding, that were also shown to be significantly affected by targeting. T-tests for these results are reported in the Online Supplementary Material.

Manipulation check

We included survey items to assess whether Black Americans were sensitive to the content described in the targeted (vs. nontargeted) message. Thus, participants completed three items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1, Strongly disagree, to 7, Strongly agree (e.g., “The HIV paragraphs appear to be written specifically for people who share my racial/ethnic identity”; α = .91).

Analytic strategy

To test whether exposure to a targeted (vs. nontargeted) message produces negative consequences for Black participants, we conducted independent-samples t-tests on the primary study outcomes.

As a next step, we sought to replicate the indirect effect modeled in Study 1. As such, we used Model 6 in PROCESS with 5,000 bootstrap resamples to assess whether exposure to targeting undermines outcomes for Black Americans via social identity threat. Specifically, we examined the extent to which (a) exposure to a targeted (vs. nontargeted) message elicited social identity threat, (b) experienced social identity threat predicted reductions in attention and trust, and (c) attention and trust predicted downstream cognitive and behavioral responses. As in Study 1, separate models were run for each outcome. The paths of greatest theoretical interest are described below, and all other statistical parameters are presented in the Online Supplementary Material.

Because data for the study measures were collected at once (and causality of our model cannot be inferred), we also performed sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our mediation analysis to unobserved variables that may influence the proposed mechanism and outcomes in this model (i.e., sequential ignorability; Imai et al., 2010). These analyses tested whether exposure to targeting predicts decrements in attention and trust via social identity threat. Using the methods developed by Imai and colleagues (2010), these analyses included 5,000 bootstrap iterations.

Results

As in Study 1, we did not find significant effects of the targeting manipulation on information recognition, elaboration of message content, and willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. Although there was a significant effect of condition on participants’ source preference for additional health information, these analyses are reported in the Online Supplementary Material for brevity.

Manipulation check

The t-test was significant, t(379) = −31.14, p <.001, d = 3.20. Means showed that participants in the targeting condition reported stronger perceptions that the message implicated their racial identity (M = 5.41, SD = 1.30) than participants in the control condition (M = 1.75, SD = 0.97).

Perceptions of targeting

Replicating Study 1, a significant t-test demonstrated that participants in the targeting condition (M = 3.55, SD = 1.46) reported stronger perceptions of being targeted than participants in the control condition (M = 1.66, SD = 1.00), t(379) = −14.75, p <.001, d = 1.51.

Attention to the health message2

The t-test was not significant, t(379) = 0.96, p = .339, d = −.10. Participants in the targeting condition (M = 7.68, SD = 1.54) reported equal levels of attention to the message as participants in the control condition (M = 7.83, SD = 1.38).

Trust in the message provider

A significant t-test showed that participants in the targeting condition (M = 6.93, SD = 1.65) reported less trust in the message provider than participants in the control condition (M = 7.26, SD = 1.51), t(379) = 2.03, p = .043, d = −.21.

Social identity threat

Replicating Study 1, participants in the targeting condition (M = 3.37, SD = 2.17) reported stronger feelings of social identity threat than participants in the control condition (M = 2.05, SD = 1.58), t(379) = −6.76, p <.001, d = .69.

Testing the mechanism: social identity threat

Findings showed that Black Americans in the targeting (vs. control) condition reported stronger feelings of social identity threat, which, in turn, predicted reduced attention to the health message (Table 4) and decreased trust in the message provider (Table 5). Reduced attention predicted worse recognition of the message content, and decreased trust predicted a stronger preference to receive additional health information that was selected at random, versus by the research team. Lastly, in contrast to the model observed in Study 1, only reductions in trust predicted decreased elaboration of message content, which subsequently predicted decreased willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. Reductions in attention directly predicted decreased willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. The indirect effects for these reported pathways were significant across outcomes.

Table 4.

Mediation analyses: Statistical parameters for primary pathways (via attention; Study 2)

| Tested effect | b | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target → Social identity threat | 1.32 | 0.19 | [0.93, 1.70] |

| Social identity threat → Attention | −0.24 | 0.04 | [−0.31, −0.16] |

| Information recognition | |||

| Attention → Information recognition | 0.16 | 0.04 | [0.08, 0.23] |

| Target → Information recognition | 0.09 | 0.11 | [−0.12, 0.30] |

| Indirect effect | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.08, −0.02] |

| Willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior | |||

| Attention → Elaboration of content | 0.01 | 0.06 | [−0.10, 0.13] |

| Elaboration of content → Message-relevant behavior | 0.14 | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.18] |

| Target → Message-relevant behavior | −0.02 | 0.07 | [−0.15, 0.12] |

| Indirect effect | −0.001 | 0.003 | [−0.006, 0.004] |

Table 5.

Mediation analyses: Statistical parameters for primary pathways (via trust in provider; Study 2)

| Tested effect | b | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target → Social identity threat | 1.32 | 0.19 | [0.93, 1.70] |

| Social identity threat → Trust | −0.28 | 0.04 | [−0.36, −0.20] |

| Source preference | |||

| Trust → Source preference | 0.25 | 0.04 | [0.16, 0.33] |

| Target → Source preference | 0.01 | 0.13 | [−0.26, 0.27] |

| Indirect effect | −0.09 | 0.03 | [−0.15, −0.05] |

| Willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior | |||

| Trust → Elaboration of content | 0.22 | 0.05 | [0.12, 0.33] |

| Elaboration of content → Message-relevant behavior | 0.14 | 0.02 | [0.09, 0.18] |

| Target → Message-relevant behavior | −0.03 | 0.07 | [−0.17, 0.11] |

| Indirect effect | −0.011 | 0.005 | [−0.022, −0.004] |

Sensitivity analysis

Analyses indicated the point at which the average causal mediation effect (ACME) was approximately zero for attention (ρ = −0.30, = .09, and = .07) and trust (ρ = −0.35, = .12, and = .10). These parameters suggest that the correlation between the error terms of the mediation and outcome models would need to be somewhat high (−0.30 for attention and −0.35 for trust) for our mediation results to be null or reverse in direction. Thus, our models appear to be fairly robust to unobserved confounders.

Summary

Study 2 documented the negative effects of targeting using a novel targeting manipulation that signaled relevance explicitly via marginalized racial identities. Specifically, exposure to a targeted message that highlighted racial disparities in HIV rates reduced Black Americans’ trust in the message provider and evoked social identity threat. However, targeting had a nonsignificant effect on attention. Replicating Study 1, modeling the indirect effect demonstrated that targeting produced negative effects on attention and trust via increased social identity threat, and these measures predicted downstream cognitive and behavioral responses.

General discussion

This report examines the efficacy of information targeting as a communication strategy and identifies whether and why efforts to signal relevance via marginalized racial identities backfires. Although information targeting leverages relevance with the assumption that relevance will facilitate persuasion and motivate behavior change, we find that targeting information based on marginalized racial identities predicts decrements in attention, trust, and willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior among Black receivers who experience social identity threat.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1a, findings demonstrated that being in the targeting (vs. control) condition produced worse outcomes for Black Americans, but not White Americans. Specifically, Black Americans who saw a targeted (vs. nontargeted) message exhibited stronger feelings of social identity threat ( i.e., perceptions of being unfairly judged), decreased attention to the message (Study 1) and reduced trust in the message provider (Study 2). Although findings from the pilot and current studies showed a more robust relationship between targeting and trust, the results on attention were less consistent. One possible explanation for these inconsistent effects is that our participant sample may have utilized heterogeneous attention-related strategies to cope with threat. For example, some participants may have disengaged from the message whereas others increased attention to counterargue the message. The complex relationship between targeting and attention, including the conditions under which participants employ different attention-related strategies, should be disentangled in future research (see also, Earl & Nisson, 2015).

Although we predicted that the consequences of targeting would be exacerbated for Black participants in response to the HIV message, negative consequences generalized across HIV and flu information (Hypothesis 1b). There are a few possible explanations for these results. First, it is possible that although the effects of targeting are stronger for stigmatizing health conditions and/or behaviors, this effect is small and we were not powered to detect it in the current studies. Indeed, detecting these partially attenuated interactions tend to require very large sample sizes (Blake & Gangestad, 2020). Alternatively, it is possible that signaling relevance through marginalized racial identities elicits identity threat regardless of the message content. Given existing research demonstrating that negative responses to information targeting can arise in response to different types of health conditions and behaviors (e.g., cancer, tobacco use), future research should assess generalizability to other types of health information (e.g., diseases with a large genetic component; Landrine & Corral, 2015; Lee et al., 2017).

Modeling the indirect effect showed that Hypotheses 2 and 3 were supported. Therefore, social identity threat served as a mechanism underlying reduced attention and trust for Black Americans (Hypothesis 2), and measures for attention and trust predicted downstream cognitive and behavioral responses (Hypothesis 3). In particular, reductions in attention predicted decreased information recognition and reporting more unrelated thoughts in a cognitive elaboration task. Reduced trust predicted a stronger preference to receive additional health information selected at random (vs. by the research team). Both attention and trust predicted reduced elaboration of message content, which subsequently predicted decreased willingness to engage in message-relevant behavior. Lastly, consistent with Hypothesis 4, Study 2 demonstrated that the negative responses observed for Black participants persisted when the targeting manipulation signaled relevance directly via marginalized racial identities.

Taken together, this work demonstrates that negative effects of race-based targeting arise for Black receivers, but not White receivers. Of note, although examining the pattern of results between racial groups suggests that these consequences are specific to persons with marginalized racial group memberships, the observed findings must be contextualized; because the current work was conducted in a U.S. context where stigmatization of Black individuals is pervasive and can result in chronically activated concerns about being devalued, it is likely that these results are driven by the intergroup dynamics within this context. Furthermore, these studies suggest that the consequences associated with targeting can generalize across different types of targeting manipulations, including when the basis for information selection is more ambiguous (Study 1), and when the communication is modified to directly implicate receivers’ racial identities (Study 2). Thus, Black individuals are sensitive to the way in which their racial identity is being used in communication, and perceiving use of their racial group membership, even when ambiguous, can elicit adverse effects. Even though participants’ mean scores for the primary outcomes (e.g., trust) were generally high across studies, it is critical to identify any communication strategies that might erode message reception among receivers, especially because these negative effects can accumulate over time.

Theoretical implications

This work has several implications for communication accommodation theory. Specifically, these studies elucidate another form of overaccommodation—race-based targeted messaging—that elicits psychological, interpersonal, and behavioral consequences for Black receivers (Hummert & Ryan, 2001). In addition, the current work provides evidence for social identity threat as a mechanism underlying negative responses to identity-based overaccommodations. To date, there has been mixed evidence about whether and how to acknowledge social identities in communication; while some research documents the benefits of adjustments which convey that the receiver is viewed as an individual (Pitts & Harwood, 2015), other work theorizes that this approach might be threatening for receivers who value their group membership (Gallois et al., 2012). Thus, our data builds on accommodation theory by suggesting that making accommodations to communication content based on more superficial characteristics (e.g., group membership) can produce deleterious effects when the receiver has a marginalized identity. Namely, these accommodations may harm receiver outcomes because they rely on overgeneralizations based on group membership, as opposed to recognizing receivers’ individual needs.

These findings also build on exemplification theory (Zillmann, 1999), particularly in health contexts (Zillmann, 2006). Although communicators may use racially minoritized groups as exemplars to communicate information about health risk, this work suggests that using exemplars at the group-level (e.g., by highlighting group-based disparities) has the potential to undermine communication and persuasive efforts. Therefore, although previous theorizing and meta-analytic data finds that use of exemplars are evaluated more favorably than nonexemplar messages, exemplars may backfire in contexts that activate concerns about how one’s social group is being evaluated (Bigsby et al., 2019; Zillmann, 2006). Moreover, our work contributes to the literature on reception theory, which posits that messages encoded by communicators will not necessarily reflect the messages decoded by receivers (Hall, 1980). The current findings illustrate that the experiences tied to Black receivers’ racial identities can shape the ways in which they make meaning of the communication. In particular, use of information targeting may yield an oppositional position for Black receivers, in part because the meaning that receivers attribute to this type of communication is that it is based in negative judgment towards their social group (Hall, 1980).

In addition, these studies contribute to a burgeoning literature identifying backfire effects of relevance in persuasive appeals (Derricks & Earl, 2019; Landrine & Corral, 2015). By examining how social identity operates in the context of persuasion, the current studies suggest that relevance may function in a more nuanced way than previously considered. Specifically, leveraging relevance through marginalized racial identities can undermine the expected benefits on persuasion when these efforts elicit social identity threat. Though communicators may rely on relevance as a strategy for accommodation, relevance tends to amplify the characteristics of the message, for better or for worse. Consequently, when a potentially stigmatizing message is directly associated with one’s racial group membership, perceiving identity-based relevance in the context of threat can exacerbate identity concerns and undermine persuasion. Thus, our data also elucidate other ways in which identities might influence persuasion. For instance, these findings suggest that communication which aims to motivate behavior change by disparaging personally relevant behaviors may backfire when the behavior is reflective of identities (e.g., appeals that stigmatize smoking behavior may prompt social identity threat among smokers; Falomir & Invernizzi, 1999; Ma & Ma, 2021). Although the current work investigates the role of identity concerns on message reception, an important consideration for future research is to examine other types of defensive processes (e.g., defensive avoidance, reactance, and fatalism) that may emerge in response to identity-based targeting.

Lastly, this set of studies offers a more nuanced understanding of conditions under which targeting interventions may be beneficial (vs. backfire). For instance, past research has established the benefits of cultural targeting, a communication strategy where information is adapted based on cultural factors (e.g., cultural values, such as religiosity or collectivist beliefs), rather than demographics (Tanjasiri et al., 2007; Yancey et al., 1995). Thus, one way to reconcile these seemingly conflicting findings between the current and prior research is to consider the dimensions on which receivers are targeted. Although incorporating aspects of receivers’ cultural values into communication may facilitate persuasion (e.g., deep structured targeting), adapting communication based on superficial characteristics, such as receivers’ membership in a particular social group (e.g., surface structured targeting), may impede persuasion. Therefore, when relevance is implicated by highlighting a potential source of threat (e.g., a marginalized identity), receivers may be more likely to reject (vs. accept) the message due to concerns about identity-based devaluation. An important direction for future work is to investigate conditions under which race-based targeting might be beneficial. For example, changing the social identity contingencies relevant in a situation (e.g., by emphasizing structural factors that perpetuate health disparities or using statements that cue support for Black Americans) may attenuate identity threat and improve engagement with targeted messages (Purdie-Vaughns et al., 2008).

Study limitations and future directions

A limitation of this work is the size of our sample across studies (and consequently, our ability to detect a small effect size). It is possible that some of our studies were underpowered to detect the hypothesized effects (e.g., the three-way interaction with message content). Although our key analyses on trust and social identity threat replicated across multiple studies, future research should attempt to replicate the less robust effects using larger samples. Despite these small effects, they are practically significant—even small changes in mistrust and/or threat can accumulate over time to facilitate more negative encounters and undermine health outcomes (Benkert et al., 2006; Haywood et al., 2014; Musa et al., 2009).

Moreover, some of our measures were created specifically for this study. For example, although our measure for trust identified the research team as the message provider, it is possible that participants were considering a less proximal message source when responding to some of the survey items. Given this possibility, future research should replicate these findings with validated measures adapted from existing literature.

While this work focuses on the consequences of race-based targeting for Black Americans, another limitation is that we did not measure racial identity and instead inferred racial identification based on participants’ self-reported race. Importantly, the strength of Black adults’ racial identification may impact the observed consequences of targeting. For instance, although Black Americans who are highly identified with their racial identity may be particularly susceptible to experiencing social identity threat (Schmader et al., 2015; Van Laar et al., 2008), burgeoning research suggests that strong group identification can buffer group members from threat due to the sense of support provided by this group membership (Cobb et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2022). Furthermore, Black Americans who have low identification with their racial identity or who hold negative attitudes towards the ingroup may respond to the threat of targeted communication by exhibiting reduced self-esteem or further disidentification from the group (Branscombe et al., 1999). Future research should account for heterogeneity among Black receivers by exploring how various racial identity profiles impact responses to targeting and assessing the role of other individual difference measures (e.g., medical mistrust) that might moderate the observed effects.

Finally, although extensive research documents the role of social identity threat as a mechanism underlying negative psychological consequences, the indirect effects modeled in these studies are correlational and causality cannot be inferred. Despite supportive evidence obtained from the sensitivity analysis, future research should obtain further support for the processes outlined in this work with a longitudinal design.

There are several ways that the research questions explored in this work can be extended in future research. For example, although the current work examined the consequences of two different targeting manipulations, other types of cues (e.g., images and other visual cues) can also signal group-based targeting. As such, a valuable direction for future research is to investigate the consequences resulting from alternative approaches to targeting. For instance, despite research documenting that Black receivers prefer communication that uses images of racially similar persons over images of White individuals (Shafer et al., 2011), these benefits may be attenuated when the images are accompanied by written text that changes the way in which identity is represented (e.g., emphasizing the importance of safe sex or getting COVID-19 vaccines; Bigsby et al., 2019).

Future investigations should also account for communicator characteristics that can shape responses to targeted communication. In the current studies, participants received little information about the message provider (i.e., the research team). Given that source characteristics have a vital role in communication effectiveness (Bolsen et al., 2019; Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Major & Coleman, 2012), future research should systematically evaluate how factors, such as shared group membership, impact receptivity of targeted communication. Although data from Study 2 showed that participants in the targeting (vs. control) condition perceived the research team to be less racially diverse (see Online Supplementary Material for additional details), which provides initial evidence that exposure to targeted communication increases perceptions of social distance, future work should manipulate these source characteristics directly. Receiving a targeted message from a source who shares the receiver’s racial identity or manipulating the perceived intentionality of the source (e.g., that the communicator is well-intended) may mitigate receivers’ concerns about being negatively evaluated based on their race and alleviate social identity threat (Giles & Gasiorek, 2013; Hornsey et al., 2002).

Relatedly, an important avenue for future research is to consider whether targeted communication elicits negative consequences when the message originates from a nonhuman source, such as a computerized algorithm. Initial research demonstrates that people who encounter demographics-based targeting report concerns about this approach, regardless of whether targeting is conducted by a human or computer algorithm (Dolin et al., 2018; Plane et al., 2017). Although study participants in the control condition may have inferred that the computer algorithm was also using their demographics to guide information selections, this possibility would suggest that our control condition is a conservative test of our effect and that the effect of targeting may be even stronger when compared to a “true” control. Thus, examining the magnitude of the consequences resulting from different message sources (e.g., nonhuman vs. human) will enrich future research examining the effects of targeting.

Conclusion

Health communication campaigns often aim to reach audiences experiencing heightened risk effectively and efficiently. However, leveraging relevance based on marginalized racial identities can backfire when recipients experience social identity threat. Therefore, it is imperative that communication efforts consider not only the message content, but also attributes about the receiver that may impact receptivity to these appeals. These studies demonstrate that Black Americans’ perceptions that their racial identity is being used as the basis for information selection can produce interpersonal, attention-related, and behavioral consequences that impede persuasion. Developing a greater understanding of the ways in which group identity operates in the context of persuasion can inform communication efforts that seek to change attitudes and/or behavior, particularly for minoritized groups. Furthermore, this knowledge can decrease the likelihood that health initiatives will inadvertently perpetuate disparities they were designed to address.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This publication was made possible with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, which is funded, in part, by Award Number KL2TR002530 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflicts to disclose.

Footnotes

A pilot study demonstrated that our experimental manipulation successfully manipulated perceptions of targeting among study participants and provided initial evidence that exposure to the targeting manipulation reduced trust in the message provider among Black participants. Additional details about this pilot study are reported on a Supplementary webpage (https://osf.io/4bqh7/?view_only=445f5cff4e5c427589f052dde071f2c2).

We also included a secondary measure of attention: counterarguing the message. Results showed that participants in the targeting (vs. control) condition were more likely to counterargue the message, t(379) = −2.38, p = .018.

Contributor Information

Veronica Derricks, Department of Psychology, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, USA; Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Allison Earl, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Journal of Communication online.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Adegbembo A. O., Tomar S. L., Logan H. L. (2006). Perception of racism explains the difference between Blacks' and Whites' level of healthcare trust. Ethnicity & Disease, 16(4), 792–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J., Burgess D., Phelan S. M., Juarez L. (2013). Unhealthy interactions: The role of stereotype threat in health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), 50–56. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh J. A. (1982). Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(3), 425–436. 10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M., Castro F. G., Strycker L. A., Toobert D. J. (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(2), 196–205. 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert R., Peters R. M., Clark R., Keves-Foster K. (2006). Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(9), 1532–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigman C. A., Nagler R. H., Viswanath K. (2016). Representation, exemplification, and risk: Resonance of tobacco graphic health warnings across diverse populations. Health Communication, 31(8), 974–987. 10.1080/10410236.2015.1026430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigsby E., Bigman C. A., Martinez Gonzalez A. (2019). Exemplification theory: A review and meta-analysis of exemplar messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(4), 273–296. 10.1080/23808985.2019.1681903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake K. R., Gangestad S. (2020). On attenuated interactions, measurement error, and statistical power: Guidelines for social and personality psychologists. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(12), 1702–1711. 10.1177/0146167220913363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen T., Palm R., Kingsland J. T. (2019). The impact of message source on the effectiveness of communications about climate change. Science Communication, 41(4), 464–487. 10.1177/1075547019863154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N. R., Ellemers N., Spears R., Doosje B. (1999). The context and content of social identity threat. In Ellemers N., Spears R., Doosje B. (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 35–58). Blackwell Science. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder L., Albarracin D., Earl A. (2008, March). Medical waiting rooms: Patients’ motivation, interest, and recall of educational materials [Poster presentation] .Southeastern Psychological Association, Charlotte, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Petty R. E. (1981). Social psychological procedures for cognitive response assessment: The thought-listing technique. In Merluzzi TV. Glass CR. & Genest M. (Eds.), Cognitive Assessment (pp. 309–342). Guilford Press.