Abstract

The postantibiotic effects (PAEs) of antimycobacterial agents determined with a BACTEC TB-460 instrument (CO2 production) and by a traditional viable-count method against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) were not significantly different (P > 0.05). The longest PAEs following a 2-h exposure to 2× the MIC were induced by amikacin (10.3 h), rifampin (9.7 h), and rifabutin (9.5 h), while the shortest PAEs resulted from clofazimine (1.7 h) and ethambutol (1.1 h) exposure. CO2 generation is a valid and efficient means of determining in vitro PAEs against MAC.

The postantibiotic effect (PAE) is a pharmacodynamic parameter that refers to the persistent suppression of bacterial growth following short exposure to and subsequent complete extracellular removal of an antibiotic (2, 17). Knowledge of this effect can optimize antibiotic dosage regimen design; however, little pharmacodynamic research has been performed with the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) primarily due to its long generation time and the time required to visualize colonies on solid media (3, 4, 11, 16). The aim of this study was to develop a faster radiometric method based upon CO2 production to determine PAEs by using clinically relevant antibiotics against MAC.

(This work was presented in part at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 28 September to 1 October 1997.)

Organisms and antibiotics.

Cultures of a reference strain of MAC, strain NJ9141, and two clinical isolates, isolates 65319 and 81433, were used. Amikacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb, St. Laurent, Quebec, Canada), azithromycin (Pfizer Canada, Kirkland, Ontario, Canada), clarithromycin (Abbott, Chicago, Ill.), clofazimine (Ciba Geigy, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), ethambutol (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), rifabutin (Pharmacia, Columbus, Ohio), rifampin (Marion Merrell Dow, Laval, Quebec, Canada), and sparfloxacin (Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Collegeville, Pa.) were tested against MAC. All antimicrobial agents were prepared according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (12).

MIC determinations.

BACTEC 12B (Middlebrook 7H12) broth (10) contains 14C-palmitic acid as a sole source of carbon. Substrate consumption releases 14CO2 into the headspace above the medium in the sealed vial. The BACTEC TB-460 instrument detects the amount of radioactivity and records it as a growth index (GI) on a scale of from 0 to 999, simultaneously replacing the evacuated gas with 5 to 10% CO2 in air (9, 15).

By the method of Heifets and coworkers (8), a BACTEC 7H12 vial (4 ml) was inoculated with a 2- to 4-day-old broth culture of MAC adjusted to an optical density equivalent to that of a no. 1 McFarland standard (3 × 108 CFU/ml) and was incubated at 37°C. When the GI of this 7H12 seed vial reached 999 on a daily reading, 0.1 ml was diluted 1:100 in dilution fluid (0.1 ml of polysorbate [fatty acid-free] Tween 80, 1 g of bovine serum albumin factor V, 500 ml of deionized water [pH 6.8]). BACTEC 7H12 vials were inoculated with 0.1 ml of the appropriate drug concentrations and 0.1 ml of the diluted culture, giving an inoculum of between 104 and 105 CFU/ml. Identically processed drug-free growth controls were also maintained. In addition, 0.1 ml of the diluted culture (104 and 105 CFU/ml) was further diluted 1:100 to create a 1:100 growth control which was inoculated (0.1 ml) into another BACTEC 7H12 vial. The vials were evacuated by the BACTEC instrument, incubated at 37°C in the dark, and read every 24 h.

The radiometric MIC is the lowest antibiotic concentration inhibiting more than 99% of the bacterial population during 8 days of incubation (5, 8). More specifically, the MIC is the drug concentration in which the final GI reading is less than 50 and the daily GI increases are lower than those for the 1:100 growth control. The MIC test finished when the GI for the 1:100 growth control was greater than 20 for 3 consecutive days within 8 days of incubation. The GI for the undiluted growth control must have reached 999 between days 4 and 8 to ensure that the correct inoculum was used. MIC determinations were repeated two to three times on separate occasions for each drug and each strain. A good correlation between GI readings and the numbers of CFU/per milliliter during active growth has been shown previously (5–7).

PAE determinations.

A BACTEC 7H12 seed vial (GI, 999) was prepared as described above for the MIC determinations. Growth control vials and test vials containing 0.1 ml of the drug at the appropriate concentration were inoculated with 0.1 ml from the seed vial (final inoculum, between 106 and 107 CFU/ml). After 2 h of incubation, 0.1-ml aliquots from each vial were diluted 1:100 in dilution fluid to remove the drug. The dilution fluid was then used to inoculate prewarmed vials with 0.1-ml aliquots. Diluted drug controls containing 1:100 dilutions of antimicrobial agent and MAC were monitored to ensure that the PAEs were not due to residual antibiotic levels. Each vial was evaluated by determining plate counts and GI. Aliquots of 0.1 ml were plated immediately after inoculation (0 h) and then after each GI reading. GI readings were taken daily for the first 48 h and then every 12 h until the GI reached 999. Initial colony counts were also verified by plating the dilution fluid. Except at 0 h, both the growth control and test vials were injected with 0.1 ml from a fresh 12B vial to maintain volume. PAE determinations were performed three to five times on different days for each drug and each strain following a 2-h exposure at 2× the MIC. Experiments were also performed three to five times on different days with each strain following a 2-h exposure at 20× the MIC by using clarithromycin, clofazimine, rifabutin, rifampin, and sparfloxacin. The GIs of the vials were read until the GI reached 999 except for the vials containing rifampin and strain 81433, which were sampled for 14 days without evidence of regrowth.

Antibiotic concentrations at 2× the MIC either are achievable in serum, as with amikacin and rifampin, or are attainable in macrophages and tissues (1, 13, 14). The concentrations of macrolides, clofazimine, ethambutol, rifabutin, rifampin, and sparfloxacin in tissue or in cells are known to be severalfold higher than the levels attainable in serum (1, 13). However, it duly noted that in tests of PAEs performed with 20× the MIC, the concentrations used in vitro may exceed in vivo concentrations in tissue or in cells in some cases. MAC was exposed to a macrolide (clarithromycin), clofazimine, rifabutin, rifampin, and sparfloxacin at these high concentrations to evaluate the radiometric method with longer PAEs.

PAE calculations.

PAE by viable counts was calculated by using the formula PAE = T − C, where T and C are the times required for the numbers of CFU per milliliter for the test and control cultures, respectively, to increase 1 log10 above the counts observed immediately after drug removal (2, 17). The PAE obtained by using GI was defined and calculated as the difference in times for the test and control cultures to increase 2 log10, which corresponds to an increase in GI of 100, during the 12-h sampling times. Factorial analyses of variance followed by the post-hoc Scheffe test were conducted with the data.

Results.

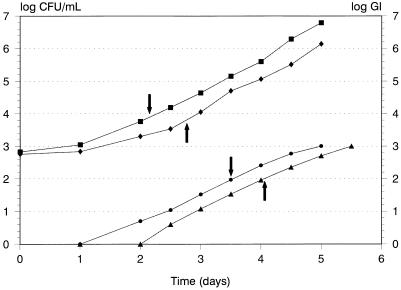

Differences in MICs for the MAC strains of greater than one twofold dilution occurred with azithromycin, clofazimine, rifampin, and sparfloxacin (Table 1). The PAEs determined by the two methods, viable counting and CO2 generation (BACTEC) as assessed by determining the GI, after 2-h exposures to antibiotics at 2× the MIC are reported in Table 2. The PAEs determined by the two methods were not significantly different (P > 0.05). The results of tests with rifampin against strain 81433 were so inconsistent that these data are not included in Table 2. Figure 1 depicts a representative determination of the PAE of rifabutin against strain NJ9141 following a 2-h exposure to rifabutin at 2× the MIC. To compare the durations of PAEs induced by the different antibiotics tested, PAEs were calculated by combining data for all three strains and both methods. The PAEs (mean ± standard deviation) of the antibiotics at 2× the MIC against MAC obtained by combining data for all three strains and both methods were as follows: amikacin, 10.3 ± 1.3 h; azithromycin, 4.6 ± 0.9 h; clarithromycin, 6.8 ± 0.7 h; clofazimine, 1.7 ± 0.9 h; ethambutol, 1.1 ± 0.5 h; rifabutin, 9.5 ± 0.6 h; rifampin, 9.7 ± 0.8 h; and sparfloxacin, 4.9 ± 0.9 h. Differences between antibiotics were observed (P < 0.001) with amikacin (mean, 10.3 h), rifampin (mean, 9.7 h), and rifabutin (mean, 9.5 h), resulting in significantly longer PAEs than those for clofazimine (mean, 1.7 h) and ethambutol (mean, 1.1 h). Differences between strains were tested for by combining PAEs determined by both methods. Among all strains, ethambutol and clofazimine resulted in the shortest PAEs, while rifabutin and rifampin resulted in the longest PAEs.

TABLE 1.

Radiometrically determined MICs of antibiotics for three strains of MACa

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NJ9141 | 65319 | 81433 | |

| Amikacin | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Azithromycin | 32 | 8 | 4 |

| Clarithromycin | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Clofazimine | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Ethambutol | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Rifabutin | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Rifampin | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 |

The MICs determined radiometrically were within 1 doubling dilution of the MICs determined by direct plating.

TABLE 2.

PAEs of antibiotics against MAC strains following 2-h exposures at 2× the MIC

| Antibiotic | Methoda | PAE (h)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NJ9141 | 65319 | 81433 | ||

| Amikacin | 1 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 14.9 ± 0.5 | 14.7 ± 3.1 |

| 2 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 17.9 ± 9.3 | 14.9 ± 0.9 | |

| Azithromycin | 1 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 5.5 ± 2.4 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | |

| Clarithromycin | 1 | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 9.9 ± 1.8 | 8.0 ± 3.8 |

| 2 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | |

| Clofazimine | 1 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 0.9 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 3.1 |

| 2 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | −0.4 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | |

| Ethambutol | 1 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 0.1 ± 1.5 |

| 2 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 1.8 | |

| Rifabutin | 1 | 11.7 ± 1.3 | 11.4 ± 1.7 | 9.6 ± 0.9 |

| 2 | 11.7 ± 2.5 | 8.4 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 2.9 | |

| Rifampin | 1 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 7.5 ± 3.6 | |

| 2 | 11.3 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 2.6 | ||

| Sparfloxacin | 1 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 1.8 |

| 2 | 8.0 ± 2.9 | 7.8 ± 3.3 | 0.8 ± 2.0 | |

Method 1 assessed PAEs by using viable counts. Method 2 assessed PAEs by using CO2 generation (BACTEC) as assessed by determining the GI.

Values are means ± standard deviation.

FIG. 1.

Determination of rifabutin PAE against MAC strain NJ9141 following a 2-h exposure to rifabutin at 2× the MIC. ▪, viable count, growth control; ⧫, viable count, rifabutin; •, GI, control; ▴, GI, rifabutin. For viable-count curves, arrows indicate the difference in times for control and exposed cultures to increase 1 log10 CFU/ml above the initial counts. For GI curves, arrows indicate the difference in times for GI, for the growth control and exposed cultures to increase 2 log10 above zero.

The PAEs determined by the two methods after 2-h exposures to antibiotics at 20× the MIC are presented in Table 3. The PAEs determined by the two methods were not significantly different (P > 0.05). The PAEs (mean ± standard deviation) of the antibiotics at 20× the MIC against MAC obtained by combining data for all three strains and both methods were as follows: clarithromycin, 18.9 ± 4.6 h; clofazimine, 9.0 ± 3.2 h; rifabutin, 31.2 ± 4.9 h; rifampin, 36.7 ± 3.8 h; and sparfloxacin, 20.6 ± 3.8 h. Significant differences were observed between the PAEs produced for all three strains (P < 0.001). Clofazimine resulted in the shortest PAEs among all strains, while rifampin and rifabutin caused the longest PAEs.

TABLE 3.

PAEs of antibiotics against MAC following 2-h exposures at 20× the MIC

| Antibiotic | Methoda | PAE (h)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NJ9141 | 65319 | 81433 | ||

| Clarithromycin | 1 | 20.6 ± 5.0 | 11.9 ± 4.8 | 12.5 ± 1.9 |

| 2 | 17.8 ± 1.6 | 21.9 ± 5.1 | 14.5 ± 3.5 | |

| Clofazimine | 1 | 15.2 ± 3.9 | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 11.5 ± 2.1 |

| 2 | 13.1 ± 2.2 | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 10.2 ± 1.7 | |

| Rifabutin | 1 | 41.6 ± 5.4 | 24.1 ± 3.3 | 24.3 ± 3.6 |

| 2 | 38.6 ± 1.7 | 21.0 ± 2.2 | 28.9 ± 2.3 | |

| Rifampin | 1 | 29.2 ± 3.0 | 54.9 ± 5.8 | |

| 2 | 30.5 ± 1.9 | 45.3 ± 3.8 | ||

| Sparfloxacin | 1 | 23.2 ± 9.6 | 13.6 ± 3.0 | 11.7 ± 4.4 |

| 2 | 36.4 ± 3.5 | 16.4 ± 2.3 | 11.6 ± 6.3 | |

Method 1 assessed PAE by using viable counts. Method 2 assessed PAE by using CO2 generation (BACTEC) as assessed by determining the GI.

Values are means ± standard deviations.

Discussion.

Statistical analysis of our PAE results demonstrated no significant difference between the viable-count method and the CO2 generation method (BACTEC) as assessed by determining the GI. The GI definition of PAE as the difference in times for control and test GIs to increase 2 log10 was developed because lower GI values were less reliable. In addition, GI values above 400 may be meaningless because the next reading, 12 h later, often reaches the maximum of 999. A GI of 100 (or 2 log10) is a value on the straight portion of the MAC growth curve, with meaningful values occurring both above and below that value, allowing for calculation of the PAE according to the GI. The actual colony count at a GI of 100 is between 105 and 106 CFU/ml.

On the basis of our PAE data, it appears that antimycobacterial agents may be divided into three principal groups given the length of the PAE produced following a 2-h exposure at 2× the MIC. Rifampin, rifabutin, and amikacin all produced PAEs of approximately 10 h under these conditions. Azithromycin, clarithromycin, and sparfloxacin conferred intermediate-length PAEs (approximately 4 to 7 h), while clofazimine and ethambutol produced PAEs of 1 to 2 h. Previous work by Tsui and coworkers (16) has also suggested that amikacin induces longer PAEs than ofloxacin against Mycobacterium fortuitum. The longer PAEs induced by exposure to clarithromycin, clofazimine, rifabutin, rifampin, and sparfloxacin, which were performed with 20× the MIC, indicate that the PAEs of these antibiotics against MAC are concentration dependent. Interestingly, the PAEs performed with 2× and 20× the MICs for 2-h exposures generally resulted in a minimal reduction of the initial colony counts. The differences noted between strains may be due to various affinities between antibiotics and their cellular binding sites.

We have demonstrated that a radiometric method of determining PAEs for MAC is reliable and is also less time-consuming and labor intensive than the viable-count method. Knowledge of PAE may be helpful in guiding dosage regimens for mycobacterial infections, including MAC infections. MAC is an important pathogen associated with disseminated infection in AIDS patients, as well as with localized pulmonary disease (6). Tailoring the dosage regimen by using PAE data may help to optimize the efficacy and decrease the toxicity of treatments for MAC infections.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the PMAC-Health Research Foundation and the Medical Research Council of Canada. James Karlowsky holds a MRC/PMAC-HRF fellowship. George Zhanel holds a Merck Frosst Chair in Pharmaceutical Microbiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alford R H, Wallace R J. Antimycobacterial agents. In: Mandell G L, Bennett J E, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig W A, Gudmundsson S. Postantibiotic effect. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1996. pp. 296–329. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson J M, Mitchison D A. In vitro studies on the choice of drugs for intermittent chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Tubercle. 1966;47:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson J M, Mitchison D A. Observations in vitro on the suitability of pyrazinamide for intermittent chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Tubercle. 1970;51:389–396. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(70)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heifets L B. Dilemmas and realities in drug susceptibility testing of M. avium-intracellulare and other slowly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria. In: Heifets L B, editor. Drug susceptibility in the chemotherapy of mycobacterial infections. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heifets L B, Iseman M D, Lindholm-Levy P J. Ethambutol MICs and MBCs for Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:927–932. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heifets L B, Iseman M D, Lindholm-Levy P J, Kanes W. Determination of ansamycin MICs for Mycobacterium avium complex in liquid medium by radiometric and conventional methods. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:570–575. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heifets L B, Lindholm-Levy P J, Libonati J, Hooper N, Laszlo A, Cynamon M, Siddiqi S. Radiometric broth macrodilution method for determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) with Mycobacterium avium complex isolates (proposed guidelines) Denver, Col: National Jewish Center for Immunology and Respiratory Medicine; 1993. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inderlied C B. Antimycobacterial agents: in vitro susceptibility testing, spectra of activity, mechanisms of action and resistance, and assays for activity in biological fluids. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1996. pp. 127–175. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middlebrook G, Reggiardo G Z, Tigertt W D. Automatable radiometric detection of growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in selective media. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;15:1067–1069. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchison D A, Dickinson J M. Laboratory aspects of intermittent drug therapy. Postgrad Med J. 1971;47:737–741. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.47.553.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. M7-A4. 4th ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peloquin C A. Antituberculous drugs: pharmacokinetics. In: Heifets L B, editor. Drug susceptibility in the chemotherapy of mycobacterial infections. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanford J P, Gilbert D N, Sande M A. The Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy. 26th ed. Dallas, Tex: Antimicrobial Therapy Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddiqi S H. Radiometric (BACTEC) tests for slowly growing mycobacteria. In: Isenberg H D, editor. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsui S Y T, Yew W W, Li M S K, Chan C Y, Cheng A F B. Postantibiotic effects of amikacin and ofloxacin on Mycobacterium fortuitum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1001–1003. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhanel G G, Hoban D J, Harding G K M. The postantibiotic effect: a review of in vitro and in vivo data. DICP Ann Pharmacother. 1991;25:153–163. doi: 10.1177/106002809102500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]