Abstract

Chemoimmunotherapy has been approved as standard treatment for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), but the clinical outcomes remain unsatisfied. Abnormal epigenetic regulation is associated with acquired drug resistance and T cell exhaustion, which is a critical factor for the poor response to chemoimmunotherapy in TNBC. Herein, macrophage-camouflaged nanoinducers co-loaded with paclitaxel (PTX) and decitabine (DAC) (P/D-mMSNs) were prepared in combination with PD-1 blockade therapy, hoping to improve the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy through the demethylation of tumor tissue. Camouflage of macrophage vesicle confers P/D-mMSNs with tumor-homing properties. First, DAC can achieve demethylation of tumor tissue and enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to PTX. Subsequently, PTX induces immunogenic death of tumor cells, promotes phagocytosis of dead cells by dendritic cells, and recruits cytotoxic T cells to infiltrate tumors. Finally, DAC reverses T cell depletion and facilitates immune checkpoint blockade therapy. P/D-mMSNs may be a promising candidate for future drug delivery design and cancer combination therapy in TNBC.

Key words: Triple negative breast cancer, Chemoimmunotherapy, Epigenetics, Demethylation, Decitabine, Immunogenic cell death, Anti-tumor immunity, Combination therapy

Graphical abstract

Macrophage-camouflaged nanoinducers co-loaded with PTX and DAC (P/D-mMSNs) were prepared in combination with PD-1 blockade therapy, where P/D-mMSNs significantly improved the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy through the demethylation of tumor tissue.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently cancer worldwide and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women1,2. Currently, chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy such as anti-programmed death ligand 1 (αPD-LI) or anti-programmed death 1 (αPD-1) has been approved as standard treatment for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), while only showed a 50% overall response rate and 9%–17% complete response rate3, 4, 5. Accumulating evidences indicate that epigenetic dysregulation is a critical factor for the poor responses of TNBC patients to chemoimmunotherapy6,7. Epigenetic dysregulated tumors are insensitive to chemotherapeutic agents, accompanied by depletion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment8,9. Thus, regulating the normalization of tumor epigenetics is the key to improve the success of chemoimmunotherapy in TNBC.

Epigenetics regulates gene expression mainly at three levels: DNA methylation, histone modification and non-coding RNA editing10. In particular, DNA methylation tightly regulates gene expression and plays an important role in tumorigenesis and development11,12. On the one hand, the tumor genome is accompanied by abnormal methylation and demethylation, resulting in dysregulated expression of DNA repair-related genes, pro-apoptotic genes, drug binding and transport genes, etc13. These changes will result in uncontrollable tumor cell growth and insensitivity to chemotherapy drugs. In preclinical studies, the demethylating drug decitabine (DAC) has been shown to sensitize drug-resistant cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs such as paclitaxel (PTX), doxorubicin (DOX), etc14, 15, 16. On the other hand, continued exposure of T cells to inflammatory or antigenic signals will be in a state of exhaustion, and DNA hypermethylation is an intrinsic cause of T cell exhaustion17,18. Ghoneim et al.19 found that de novo DNA methylation mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3 (DNMT3) promotes the formation of exhausted T cell. The demethylating drug DAC can improve the depletion of CD8+ T cells, and combined treatment with αPD-1 significantly reduced tumor burden in mice. Therefore, demethylation of tumor tissue is expected to improve the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy.

Herein, DAC is selected to combine with PTX and αPD-1 to improve the therapeutic effect of TNBC (Scheme 1). DAC can achieve demethylation of tumor tissue and enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to PTX. Subsequently, PTX induces immunogenic death of tumor cells, accompanied by the release of tumor-associated antigens and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including adenosine triphosphate (ATP), calreticulin (CRT), and high mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1)20. These immunogenic signals promote dendritic cells (DCs) to phagocytose dead cells and recruit antigen-specific T cells into tumor tissue21. Finally, DAC reverses T cell depletion and facilitates immune checkpoint blockade therapy. This combination may be a promising therapeutic strategy to improve the response of TNBC to chemoimmunotherapy.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of macrophage-camouflaged nanoinducers (P/D-mMSNs) to improve the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy. (A) Preparation of P/D-mMSNs. B) P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 improve the anti-tumor efficiency. (I) P/D-mMSNs enhance the sensitivity of 4T1 cells to PTX via demethylation of tumor tissue. (II) P/D-mMSNs induce immunogenic death of tumor cells and initiate anti-tumor immunity. (III) P/D-mMSNs reverse T cell depletion and facilitate immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

The co-delivery of different drugs to tumor tissues is the key to enhancing the synergistic efficiency of combination therapy. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are inorganic nanoparticles with excellent biocompatibility, which have unique features in drug loading due to their large pore size and high surface ratio22, 23, 24. MSNs co-loaded with PTX and DAC (P/D-MSNs) were selected for drug co-delivery. Furthermore, successful drug delivery to tumor tissues is critical for therapy. Macrophages perform tumor tissues migration, and are the most abundant cell type in tumor microenvironments25,26. The integrin α4, integrin β1, and chemokine C–C-Motif receptor 2 (CCR2) on the surface of macrophages dominate this migration27,28. Encapsulation of macrophage membrane-derived vesicle containing α4β1 and CCR2 may endow MSNs with the tumor homing property29. As such, P/D-MSNs were further camouflaged with macrophage vesicle (P/D-mMSNs) to enable tumor tissue-specific targeting.

For this study, P/D-mMSNs were successfully prepared and the physicochemical properties were characterized. Tumor accumulation, cellular uptake and co-delivery were verified. The ability of P/D-mMSNs to induce demethylation, promote apoptosis and arrest cell cycle was investigated. The immunogenic death of tumor cells was assessed by DAMPs release (including CRT, HMGB1, and ATP) and DCs maturation. The ability of P/D-mMSNs to improve the immune microenvironment and reverse T cell exhaustion was assessed by the infiltration of T cells, CTLs, Tregs, and the cytokines secretion in tumor tissues. The anti-tumor efficiency and long-term immune memory effect of P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 were investigated on 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. This study provides a promising epigenetic nano-modulation strategy for improving chemoimmunotherapy in TNBC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Paclitaxel (PTX), Decitabine (DAC), DiR iodide, Coumarin 6 (C6) and Rhodamine B (RhB) were purchased from Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and Mouse HMGB1 ELISA Kit were purchased from Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Cell Cycle Analysis Kit and ATP Assay Kit were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Agents for SDS-PAGE were purchased from Epizyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Antibodies for Western blot were purchased from Abcam Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Antibodies for ICD analysis were purchased from Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Anti-mouse PD-1 antibody and antibodies for flow cytometry assay were purchased from BioLegend Inc. (San Diego, California, USA). Cytokine ELISA kits were purchased from MultiSciences Biotech Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). All other materials and reagents were of analytical reagent grade.

2.2. Cell lines and animals

Murine triple-negative breast cancer cells (4T1) and murine macrophages (RAW 264.7) were purchased from the Cell Bank/Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences. 4T1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). RAW 264.7 was cultured in DMEM medium contained 10% FBS. Female BALB/c mice aged 6–8 weeks were purchased from SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All experimental procedures were executed according to the protocols approved by the Animal Management Rules of the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China and the Animal Experiment Ethics Review of Shandong University.

2.3. Isolation of macrophage membrane-derived vesicle

RAW 264.7 were collected and suspended in Tris-magnesium buffer (1 × 107 cells/mL). The cell suspension was then placed on ice and broke by ultrasound. The macrophage membrane-derived vesicle (mø vesicle) was isolated by ultracentrifugation and resuspended in Tris-magnesium buffer. The obtained products were successively extruded through 1 μm, 400 nm, 200 nm, and 150 nm LiposoFast-Basic extruder (Avastin, Ottawa, Canada). The protein content was determined by BCA protein kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

2.4. Preparation of MSNs

CTAB (200 mg), NaOH (0.5 mol/L, 0.6 mL), ethanol (10 mL) and distilled water (100 mL) were mixed in a 250 mL round-bottom flask and heated to 80 °C with vigorous stirring. Then, TEOS (0.6 mL) was added dropwise to the mixture solution and kept stirring for 2 h. The reactants were centrifuged after cooling, washed with water and alcohol, and dried down in vacuum. The CTAB surfactant was removed by refluxing with NH4NO3/ethanol solution at 65 °C for 6 h, and repeated three times to obtain MSNs. The MSNs were washed and collected for characterization and usage.

2.5. Preparation of P/D-mMSNs

MSNs (20 mg) were ultrasonically dispersed in acidic methanol aqueous solution containing PTX and DAC, and stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After that, the PTX and DAC loaded MSNs (P/D-MSNs) was separated by centrifugation and rinsed with methanol aqueous solution to remove the PTX and DAC absorbed on the external surfaces. Then, P/D-MSNs and mø vesicles were co-extruded to prepare P/D-mMSNs. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to determine the concentrations of PTX and DAC in the initial and supernatant solution. The drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) were calculated as shown in Eqs. (1), (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Wdrug represents the amounts of drug in P/D-mMSNs, Wtotal drug represents the amounts of drug added to the system, Wcarrier represents the amounts of mMSNs.

2.6. Characterization of P/D-mMSNs

The morphologies of MSNs, mø vesicle and P/D-mMSNs were observed with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEOL, Japan). The hydrodynamic size and zeta potential were determined by the Zeta Sizer Nano-ZS instrument (Malvern, UK). The pore volume and pore size distribution of MSNs and P/D-mMSNs were measured by surface area and porosity analyzer (Micromeritics, USA). The total proteins and the membrane-associated markers in mø, mø vesicle and P/D-mMSNs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting, respectively.

2.7. In vitro drug release

The release of PTX and DAC from P/D-mMSNs was monitored by the dialysis method. Briefly, PTX solution, DAC solution and P/D-mMSNs were dialyzed (MWCO 8–14 kDa) in 10 mL PBS (pH 7.4, 6.5 or 5.5) containing 0.5% Tween-80. The system was stirred at 37 °C during the whole process. At predetermined time points, the release medium was collected and replaced with 10 mL fresh medium. The released concentration of PTX and DAC were determined by HPLC. All samples were performed three times.

2.8. Hemolysis analysis

Red blood cells (RBCs) were isolated from rat blood for the hemolysis analysis of P/D-mMSNs. P/D-mMSNs (10, 50, 100, 250, 500 μg/mL) were mixed with 2% RBCs, and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Following centrifugation to remove erythrocytes, the samples were photographed and the absorbance of hemoglobin was measured by UV–vis spectrophotometer. The hemolysis ratio were calculated as shown in Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where Ax, A1 and A0 represented the absorbance of the samples, H2O and NS, respectively.

2.9. Cellular uptake

C6 was selected as a tracer to prepare C6-mMSNs. 4T1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 per well and cultured overnight. Then, fresh media containing C6-MSNs and C6-mMSNs were added at predetermined time points. After incubating for 0.5 or 2 h, the cells were stained with DAPI and imaged using inverted fluorescence microscope (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont, USA). The quantification of cellular uptake was evaluated by flowcytometry (CytoFLEX, Beckman, Pasadena, California, USA).

2.10. Biodistribution and tumor accumulation

DiR was selected as a near-infrared tracer to prepare D-mMSNs. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice model was used to evaluate the in vivo biodistribution of D-mMSNs. Mice were intravenous injection with free DiR, D-MSNs or D-mMSNs (the equivalent DiR was 10 ug per mouse). At predetermined time points, mice were anesthetized and captured using real-time IVIS spectrum (Caliper Life Sciences, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). At 24 h post administration, mice were euthanized, the organs and tumors were harvested for ex vivo imaging.

2.11. Pharmacokinetic analysis

Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were administrated with PTX, DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs via intravenous injection (the dose of PTX and DAC were 10 mg/kg and 2.5 mg/kg). Blood samples was collected from the orbital vein at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after administration. Plasma samples were processed for determination, peak areas were recorded and plasma concentrations were calculated at each time point.

2.12. In vivo co-delivery ability

C6 and RhB were selected as tracers and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice model was used to verify the co-delivery ability of mMSNs. Mice were intravenous injection with C6 and RhB mixed solution, or C6 and RhB co-loaded mMSNs. At 12 h post administration, mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected for histological analysis. The tissues were stained with DAPI and imaged by confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 780, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.13. In vitro cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of P/D-mMSNs in 4T1 cells was investigated using MTT assay. 4T1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 per well and cultured overnight. Then, fresh media containing MSNs, mMSNs, PTX, DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs with different concentrations were added. After incubating for 48 h, MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well for another 4 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed and DMSO was added. The cell viability was measured at 570 nm with a microplate reader.

2.14. Cell apoptosis and cell cycle analysis

4T1 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 per well and cultured overnight. Then, fresh media containing NS, PTX, DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs or P/D-mMSNs were added. After incubating for 24 h, for apoptosis analysis, cells were collected and stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For cell cycle analysis, cells were collected and fixed with 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 12 h, and then stained with propidium iodide (PI) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Western blotting analysis of proteins was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.15. Demethylation analysis

For demethylation analysis, 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenous injection with NS, PTX, DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs or P/D-mMSNs. After one treatment cycle, mice were sacrificed and tumors were collected for cyro-sectioning. The tissues were stained with DAPI and anti-DNMT3 antibody, and imaged by confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss).

2.16. Immunogenic cell death analysis

4T1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 per well and cultured overnight. Then, fresh media containing NS, PTX, DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs or P/D-mMSNs were added. For analysis of CRT exposure, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, labeled with anti-CRT primary antibody and AF488-conjugated secondary antibody. Subsequently, cells were stained with DiI for membrane and DAPI for nucleus. Images were observed with an inverted fluorescence microscope, and quantified with flow cytometry. For analysis of HMGB1 release, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, treated with 0.1% Triton X-100, labeled with anti-HMGB1 primary antibody and AF488-conjugated secondary antibody. Images were observed with an inverted fluorescence microscope, and quantified with ELISA assay kit. For analysis of ATP secretion, the cell culture supernatant was collected and assayed using the ATP assay kit.

2.17. In vitro dendritic cells maturation

Bone marrow-derived monocytes were extracted from the bones of female BALB/c mice, and induced in 6-well plates with RPMI-1640 medium containing FBS (10%), GM-CSF (20 μg/mL) and IL-4 (10 μg/mL), to obtain bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). 4T1 cells were treated with NS, PTX, DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs or P/D-mMSNs, respectively, and then co-cultured with BMDCs using a Transwell system. For DCs maturation analysis, cells were stained with anti-CD11c-PE, anti-CD80-FITC and anti-CD86-PerCP. All samples were evaluated by flow cytometry and analyzed by FlowJo. The cell culture supernatant was collected to analysis the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 using ELISA assay kits.

2.18. In vivo immunization study

4T1 tumor-bearing mice were treated with NS, PTX, αPD-1, PTX+αPD-1, DAC, PTX+αPD-1+DAC, P-mMSNs, P/D-mMSNs, P/D-MSNs+αPD-1 and P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1, respectively. Tumor tissues were collected to prepare single-cell suspensions, and washed with PBS containing 1% rat serum. For T cells analysis, cells were stained with anti-CD3-APC, anti-CD4-FITC, and anti-CD8-PE. For CTLs analysis, cells were stained with anti-CD8-PE and anti–INF–γ-APC. For Tregs analysis, cells were stained with anti-CD4-FITC and anti-Foxp3-APC. All samples were evaluated by flow cytometry and analyzed by FlowJo. The secretion of IFN-γ, IL-12, TGF-β and IL-10 in tumor tissues were measured using ELISA assay kits.

2.19. In vivo anti-tumor activity

4T1 cells were subcutaneously injected into right axillary of BALB/c mice at a density of 1 × 106. While tumor grew to 100 mm3, mice were randomly divided into 10 groups and treated with NS, PTX, αPD-1, PTX+αPD-1, DAC, PTX+αPD-1+DAC, P-mMSNs, P/D-mMSNs, P/D-MSNs+αPD-1 and P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1, respectively. The dose of PTX, αPD-1 and DAC were 10 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 2.5 mg/kg, respectively. Body weight and tumor volume were measured every 2 days. Mice were sacrificed on Day 21, following which the tumors and major organs were dissected for histological analysis. The tumor sections were analyzed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Ki-67 immunohistochemistry and TUNEL immunofluorescence, major organs were analyzed with H&E staining.

2.20. Long-term immune memory

4T1 tumor-bearing mice were treated with PTX+αPD-1, PTX+αPD-1+DAC, P/D-mMSNs, and P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1, respectively. On Day 30, those mice were re-inoculated with 1 × 106 4T1 cells in the left axilla to establish a secondary tumor model. Untreated BALB/c mice were inoculated as a control group. The re-inoculated tumor volume was measured every 2 days. On Day 50, the spleens were harvested to prepared single-cell suspensions. For CD8+ TEM analysis, cells were stained with anti-CD3-APC, anti-CD8-PE, anti-CD62L-FITC and anti-CD44-PerCP. All samples were evaluated by flow cytometry and analyzed by FlowJo. The secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α in secondary tumors were measured using ELISA assay kits.

2.21. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Prism software (version 8.0, GraphPad) (Prism 8.0). ∗P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of P/D-mMSNs

First, RAW 264.7 cells were cultured and the macrophage membrane-derived vesicle (mø vesicle) were separated. From 1 × 108 RAW 264.7 cells, 8.42 ± 3.48 mg vesicle were obtained. The MSNs was prepared using the sol–gel method. PTX and DAC were loaded into the pores of MSNs (P/D-MSNs) by passive drug loading method. The optimal formulation was as follows: the ratio of drug to MSNs was 1.5:1, the ratio of PTX to DAC was 2:1, and the ratio of vesicle to P/D-MSNs was 1:1 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). The drug loading of PTX and DAC in P/D-MSNs were 22.07 ± 0.81% and 6.40 ± 0.48%, respectively (Supporting Information Table S1). P/D-mMSNs were prepared by co-extrusion of mø vesicle and P/D-MSNs (Fig. 1A). PTX and DAC suffered a slight loss after co-extrusion, and the drug loading of PTX and DAC in P/D-mMSNs were 10.55 ± 0.32% and 2.70 ± 0.34%, respectively (Table S1). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image revealed that mø vesicle, MSNs and P/D-MSNs were nanoparticles with rounded morphology and uniform dispersion (Fig. 1B). There were ordered mesoporous channels on MSNs, while the pores of P/D-mMSNs were blurred, and a distinct film layer about 20 nm thick on the surface of the P/D-mMSNs could be observed, indicating the successful assembly of the P/D-mMSNs.

Figure 1.

Preparation and characterization of P/D-mMSNs. (A) Schematic diagram of the assembly of P/D-mMSNs. (B) TEM images of mø vesicle, MSNs and P/D-mMSNs, scale bar = 0.5 μm or 100 nm. (C) Hydrodynamic size and (D) zeta potential of mø vesicle, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs. (E) Pore size distribution of MSNs and P/D-mMSNs. (F) SDS-PAGE analysis of total proteins and (G) western blotting analysis of mø vesicle-associated markers (Integrin α4, Integrin β1, CCR2, and Na+/K+ ATPase) (1. mø, 2. mø vesicle, 3. P/D-MSNs, 4. P/D-mMSNs). (H) Particle size and PDI of P/D-mMSNs at 4 °C for 18 days. (I) Images of P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs after storage in NS for 0 and 7 days. (J) Particle size distribution of P/D-mMSNs in 10% serum at 37 °C for 72 h. (K,L) Release profiles of PTX and DAC from P/D-mMSNs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The hydrodynamic size of mø vesicle, P/D-MSNs, and P/D-mMSNs were 127.80 ± 8.38, 85.97 ± 3.08, and 107.87 ± 4.08 nm, respectively (Fig. 1C). The zeta potential of mø vesicle, P/D-MSNs, and P/D-mMSNs were −12.93 ± 1.50, −20.03 ± 1.53, and −13.17 ± 1.05 mV, respectively (Fig. 1D). The pore size distribution of MSNs was uniform with 2.73 nm, while the mesopore size of P/D-mMSNs could not be tested, indicating the pore canal of the P/D-mMSNs was covered by drug loading and membrane capping (Fig. 1E). Protein profiles in P/D-mMSNs were determined by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Most of the protein components in mø and mø vesicle were retained in P/D-mMSNs, indicating the mø vesicle was successfully fused to P/D-MSNs (Fig. 1F). Macrophages have been reported to have tumor-targeting ability, which is associated with several proteins, including integrin α4, integrin β1, and chemokine CCR2. Western blot assay was carried out to detect membrane-associated markers. The mø, mø vesicle and P/D-mMSNs all displayed the signals of integrin α4, integrin β1, and CCR2 (Fig. 1G), indicating that P/D-mMSNs retained the tumor-targeting proteins of macrophages.

Encapsulation of cell membrane could effectively prevent the precipitated of P/D-mMSNs. Upon assessing the storage stability of the P/D-mMSNs at 4 °C for 18 days, it was found that there was no obvious change in particle size or PDI (P > 0.05, P > 0.05, n = 3) (Fig. 1H). Compared with P/D-MSNs, P/D-mMSNs with mø vesicle encapsulation effectively prevented precipitation (Fig. 1I). The physical stability of P/D-mMSNs in 10% FBS was assessed within 72 h, and there was no significant change in particle size and PDI of P/D-mMSNs (P > 0.05, n = 3), indicating that P/D-mMSNs were stable in 10% serum for 72 h (Fig. 1J and Supporting Information Fig. S2). PTX and DAC could be released from P/D-mMSNs under the sink condition. The cumulative release percentage of PTX at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.5 at 24 h were 69.99 ± 2.10%, 68.29 ± 8.37% and 74.99 ± 3.24%, respectively (Fig. 1K). The cumulative release percentage of DAC at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.5 at 24 h were 81.88 ± 0.28%, 80.84 ± 7.35% and 86.13 ± 7.47%, respectively (Fig. 1L). The hemolysis rate of P/D-mMSNs at 10–500 μg/mL were negligible (<5%) (Supporting Information Fig. S3), indicating that P/D-mMSNs had good hemocompatibility and was suitable for intravenous administration.

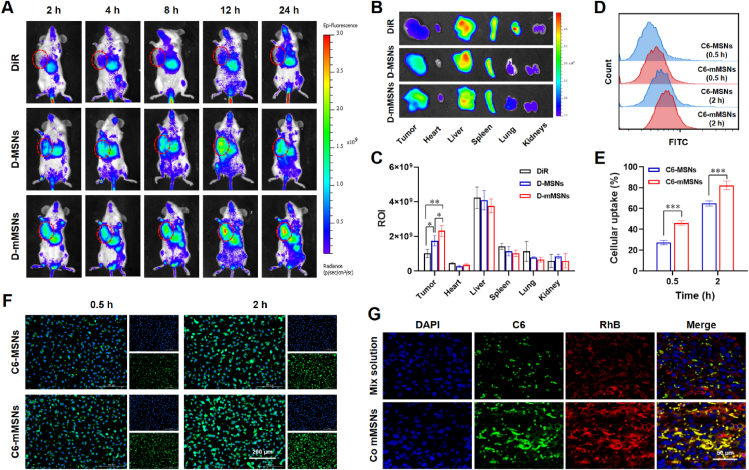

3.2. Tumor accumulation and co-delivery ability of P/D-mMSNs

The tumor accumulation ability of P/D-mMSNs was evaluated on 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. DiR was selected as a near-infrared tracer to prepare D-mMSNs. Real-time imaging showed the gradual accumulation of fluorescence at the tumor tissues after intravenous injection (Fig. 2A). Compared with the free DiR group, D-MSNs and D-mMSNs groups exhibited higher fluorescence intensity at the tumor tissues, suggesting that MSNs-loading could enhance the tumor accumulation. Subsequently, ex vivo imaging was performed 24 h after dosing to accurately assess the distribution of free DiR, D-MSNs, and D-mMSNs in tumors and major organs (Fig. 2B and C). The intensities of the tumor fluorescent signal in D-MSNs, and D-mMSNs groups were higher than that in free DiR group (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, n = 3). Compared with D-MSNs group, tumor fluorescent signal in D-mMSNs groups was significantly increased (P < 0.05, n = 3), indicating that the modification of macrophage vesicle could enhance drug accumulation in tumor tissues. The pharmacokinetic profile of P/D-mMSNs in vivo was investigated by examining the blood concentration of PTX and DAC using HPLC (Supporting Information Fig. S4). The plasma concentration of the P/D-mMSNs group was higher than that of the P/D-MSNs and free drug groups at each time point, indicating that P/D-mMSNs could slow down the clearance of the drugs in the blood and significantly prolong the circulation time of the drugs, which was beneficial to improve the therapeutic effect.

Figure 2.

P/D-mMSNs enhanced tumor accumulation, promoted cellular uptake and drug co-delivery. (A) Images of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after treated with free DiR, D-MSNs and D-mMSNs at different time intervals. (B) Images and (C) fluorescence intensity of tumors and organs at 24 h (DiR was used to label mMSNs for near-infrared imaging). (D,E) Flow cytometric analysis and (F) fluorescence images of cellular uptake in 4T1 cells, scale bar = 200 μm. (G) Fluorescence images of tumor sections after injection of different formulations, scale bar = 50 μm. (C6 was used to replace PTX, RhB was used to replace DAC). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. indicated.

The ability of P/D-mMSNs to enhance cellular uptake was evaluated on 4T1 cells. C6 was selected as a tracer to prepare C6-mMSNs. At 0.5 and 2 h, the intensity of fluorescent signal in C6-mMSNs group was higher than that in C6-MSNs group (Fig. 2F), and the flow cytometric analysis also showed the same results (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, n = 3) (Fig. 2D and E). These results demonstrate that macrophage vesicle camouflage enhanced cancer cell targeting capability, and increased intracellular uptake. The co-delivery ability of P/D-mMSNs was evaluated on 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. C6 and RhB were selected as tracers, representing PTX and DAC, respectively. Fluorescence images of tumor sections showed that the intensity of fluorescent signal in co-loaded mMSNs group was higher than that in mix solution group (Fig. 2G), indicating that mMSNs could enhance the accumulation of drugs in tumor tissue. And compared with mix solution group, C6 and RhB in co-loaded mMSNs group showed stronger co-localization (yellow), indicating that co-loaded mMSNs could co-deliver different drugs to the same location tumor tissue.

3.3. Cytotoxicity and demethylation analysis of P/D-mMSNs

P/D-mMSNs enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to PTX via demethylation (Fig. 3A). The in vitro cytotoxicity of P/D-mMSNs on 4T1 cells was detected by MTT assay. The MSNs and mMSNs had no direct cytotoxicity to tumor cells at the experimental concentrations, indicating a good safety profile (Fig. 3B). DAC has no apparent toxicity in the range of 0.1–50 μg/mL and exhibits enhanced cytotoxicity when combined with PTX (Fig. 3C and D). The IC50 value of PTX was 24.45 ± 3.92 μg/mL, while the ratio of PTX to DAC were 1:0.2, 1:0.25, and 1:0.3, the IC50 of PTX were 8.59 ± 1.63, 3.49 ± 0.42, and 2.50 ± 1.28 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that DAC could significantly enhance the sensitivity of 4T1 cells to PTX. The cell viability of P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs was like PTX + DAC (P > 0.05, P > 0.05, n = 3), suggesting that the drug encapsulated by MSNs does not affect its cytotoxicity (Fig. 3E). Human normal hepatocyte LO2 cells were selected to study the toxicity of P/D-mMSNs on normal cells. P/D-mMSNs had a certain killing effect on LO2 cells. The IC50 value of PTX in LO2 cells was 71.22 ± 19.86 μg/mL, which was significantly higher than that in 4T1 cells of 2.53 ± 0.58 μg/mL (P < 0.001, n = 3). This indicated that P/D-mMSNs had low toxicity to normal cells and a certain dose tolerance (Supporting Information Fig. S5).

Figure 3.

P/D-mMSNs enhanced the sensitivity of tumor cells to PTX via demethylation. (A) Schematic diagram of the mechanism of P/D-mMSNs. (B) Cell viability of 4T1 cells incubated with MSNs and mMSNs. (C) Cell viability of 4T1 cells incubated with DAC. (D) Cell viability of 4T1 cells incubated with PTX and DAC. (E) Cell viability of 4T1 cells incubated with P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs. (F) and (I) Apoptosis rate of 4T1 cells incubated with different formulations. (G) and (J) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle in different treated 4T1 cells. (H) Western blot analysis of DNMT3 and caspase 3 expression in 4T1 cells treated with different formulations. (K) Immunofluorescence staining of DNMT3 expression in 4T1 tumors treated with different formulations, scale bar = 50 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. indicated.

The effects of P/D-mMSNs on apoptosis was examined. The results of flow cytometric analysis showed that the apoptotic rate of 4T1 cells increased to 31.90 ± 2.19% in PTX + DAC group, while it was only 23.40 ± 4.22% in PTX group (P < 0.05, n = 3). P/D-mMSNs group showed the highest apoptotic rate of 38.83 ± 1.53% (Fig. 3F and I). And Western blot analysis showed that PTX, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs groups were accompanied by the increase of apoptotic protein caspase 3 (Fig. 3H). PTX group showed significant G2 phase arrest in 4T1 cells, with the G2 phase ratio of 61.02 ± 6.36%. DAC group arrested the cell cycle more in S phase in 4T1 cells, with the S phase ratio of 53.59 ± 10.70%. The proportion of 4T1 cells in G2 phase and S phase in P/D-mMSNs group increased to 40.96 ± 17.35% and 49.63 ± 16.06%, respectively, and the proportion of cells in G1 phase was significantly decreased (P < 0.001, n = 3), indicating that P/D-mMSNs could effectively arrested cell cycle, and inhibited cell division and proliferation (Fig. 3G and J). Subsequently, the effects of P/D-mMSNs on demethylation was examined. The fluorescence signal intensity of DNMT3 in DAC and P/D-mMSNs treated tumors were significantly decreased (Fig. 3K). And Western blot analysis showed that DAC, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs groups were accompanied by the decrease of DNMT3 (Fig. 3H). These results indicated that DAC may enhance the sensitivity of 4T1 cells to PTX through demethylation.

3.4. Immunogenic cell death induced by P/D-mMSNs

Studies have shown that chemotherapeutic drugs can cause immunogenic cell death (ICD) of tumor cells to trigger anti-tumor immunity. The CRT expression, HMGB1 release and ATP secretion in 4T1 cells were investigated to study the ICD effect induced by P/D-mMSNs (Fig. 4A). In the fluorescence images, 4T1 cells in PTX, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs groups all showed higher expose of CRT. And the green fluorescence of CRT could merge with the red fluorescence of cell membrane into yellow fluorescence. 4T1 cells in P/D-mMSNs group showed more yellow fluorescence, indicating that P/D-mMSNs could induce immunogenic cell death and promote the eversion of calreticulin to the cell membrane surface (Fig. 4B). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the expose of CRT in PTX group was 3.11-fold higher than that in NS group (P < 0.001, n = 3), PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs groups all showed higher expose of CRT, with expression levels of 39.05 ± 3.27%, 46.16 ± 2.87% and 52.93 ± 2.93%, respectively (Fig. 4C). P/D-mMSNs significantly promoted the secretion of ATP, the secretion of ATP in P/D-mMSNs group increased to 35.31 ± 2.91 nmol/L, which was 2.18-fold higher than that in NS group (P < 0.001, n = 3) (Fig. 4D). The release of HMGB1 also showed similar results, the fluorescence signal intensity of nuclear HMGB1 in PTX, PTX + DAC, P/D-MSNs and P/D-mMSNs groups was significantly decreased, and the release amounts were 22.53 ± 1.69 ng/mL, 24.55 ± 2.76 ng/mL, 37.32 ± 2.69 ng/mL, and 42.78 ± 2.50 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 4E and F). These results indicated that P/D-mMSNs could induce the ICD effect of tumor cells.

Figure 4.

P/D-mMSNs induced immunogenic death of tumor cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the ICD effect of P/D-mMSNs. (B) Fluorescence images and (C) flow cytometric analysis of CRT exposure in 4T1 cells, scale bar = 100 μm. (D) ATP secretion from 4T1 cells. (E) Fluorescence images and (F) quantitative ELISA analysis of HMGB1 release from 4T1 cells, scale bar = 100 μm. (G,H) Flow cytometry analysis of DCs maturation treated with different formulations. (I) Levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the supernatant of matured DCs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. indicated.

DCs are the most effective antigen-presenting cells and play a crucial role in initiating anti-tumor immune responses. The signals released by the ICD effect can promote the expression of co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of DCs. The maturation of DCs was evaluated, and the proportion of mature DCs increased to 23.83 ± 2.85% in PTX group, while only 13.37 ± 1.26% in NS groups (P < 0.01, n = 3) (Fig. 4G and H). P/D-mMSNs group induced the highest proportion of mature DCs at 35.33 ± 1.55%. Mature DCs secrete cytokines to regulate the activation and function of other immune cells. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the culture supernatant were detected. The P/D-mMSNs group showed the highest levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 4I). These results indicated that P/D-mMSNs could induce ICD effect and promote DCs maturation to initiate anti-tumor immunity.

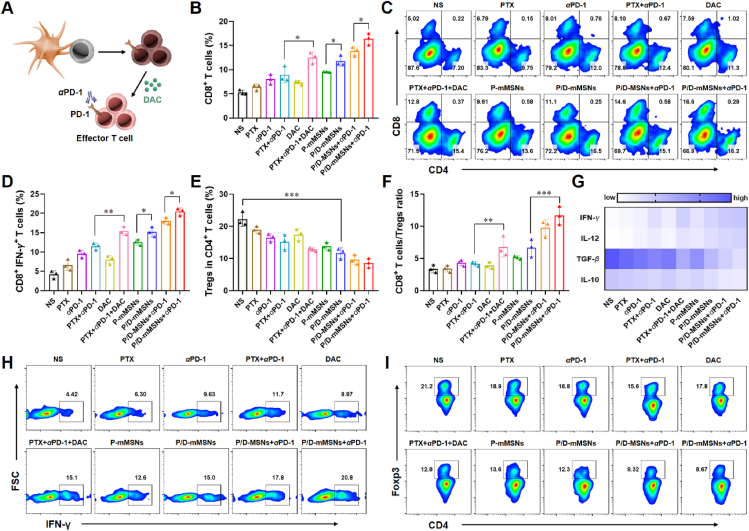

3.5. Anti-tumor immune responses of P/D-mMSNs

Mature DCs promote the proliferation and activation of T cells, and the activated T cells can migrate into tumor tissues to exert immune killing effect (Fig. 5A). The ratio of T cells, CTLs, and Tregs in tumor tissues was assessed to evaluate the immune status of tumor microenvironment. After standard chemoimmunotherapy (PTX+αPD-1), the proportion of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissue was 8.93 ± 1.63%, while combined with DAC (PTX+αPD-1+DAC) could increase to 12.50 ± 1.18% (P < 0.05, n = 3), indicating that chemoimmunotherapy combined with DAC could enhance the infiltration of T cells (Fig. 5B and C). Similarly, the proportion of CD8+ T cells in P/D-mMSNs group was 11.77 ± 1.07%, which was significantly higher than that in P-mMSNs group (P < 0.05, n = 3). And P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group had the highest proportion of CD8+ T cells of 16.40 ± 1.21%, which was significantly higher than that in PTX+αPD-1+DAC group and P/D-MSNs+αPD-1 group (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, n = 3), indicating that the camouflage of P/D-mMSNs can further enhance the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissue.

Figure 5.

P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 reversed T cells exhaustion and improved immune microenvironment. (A) Schematic diagram of immune activation. (B,C) Flow cytometry analysis of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues (gated on CD3+ T cells). (D) and (H) Flow cytometry analysis of CTLs in tumor tissues (gated on CD3+CD8+ T cells). (E) and (I) Flow cytometry analysis of Tregs in tumor tissues (gated on CD3+CD4+ T cells). (F) Ratio of CD8+ T cells to Tregs in tumor tissues. (G) ELISA analysis of IFN-γ, IL-12, TGF-β and IL-10 in tumor tissues. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. indicated.

CTLs that infiltrate tumor tissues are the main force for tumor killing, whereas Tregs are immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment. Compared with PTX+αPD-1 group, CTLs increased to 1.34-fold and Tregs decreased to 0.84-fold in PTX + DAC+αPD-1 group, indicating the improvement of immune microenvironment in combination with DAC (Fig. 5D, E, H, and I). The proportion of CTLs in P/D-mMSNs group was 15.17 ± 1.26%, which was significantly higher than that in P-mMSNs group (P < 0.05, n = 3). And the ratio of CD8+ T cells to Treg cells in P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group was 11.65 ± 1.43%, which was significantly higher than that in the PTX + DAC+αPD-1 group (P < 0.001, n = 3) (Fig. 5F). This was accompanied by increased levels of immune-activating cytokines and decreased levels of immunosuppressive cytokines (Fig. 5G). These results indicated that P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 treatment could reverse T cells exhaustion and elicit an effective anti-tumor immune response.

3.6. In vivo anti-tumor effect of P/D-mMSNs

P/D-mMSNs enhanced the sensitivity of 4T1 cells to chemotherapy, induced immunogenic death of tumor cells and improved immune microenvironment. Encouraged by these results, the anti-tumor effect of P/D-mMSNs was evaluated on 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. The mice were divided into 10 groups and administered with NS, PTX, αPD-1, PTX+αPD-1, DAC, PTX+αPD-1+DAC, P-mMSNs, P/D-mMSNs, P/D-MSNs+αPD-1 and P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1, respectively. The drugs were injected every 3 days over a period of 21 days (Fig. 6A). During dosing, the body weights of mice did not change significantly in each group (P > 0.05, n = 6), indicating that the P/D-mMSNs had low systemic toxicity (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 enhanced the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy. (A) Schedule diagram of in vivo administration approach. (B) Body weight changes of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. (C) Average tumor growth curves and (D) individual tumor growth curves of tumor-bearing mice after intravenous injection with different formulations. (E) Tumor photographs and (F) tumor weights of the sacrificed mice at the study endpoint, scale bar = 2 cm. (G) Immunohistochemical images of tumor tissue sections (H&E, Ki67, and TUNEL), scale bar = 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. indicated.

Chemoimmunotherapy is the standard treatment for TNBC, the tumor volume in PTX+αPD-1 group was smaller than that in NS group (P < 0.001, n = 6), and the tumor inhibition rate was 49.75 ± 7.10%, indicating the effectiveness of chemoimmunotherapy (Fig. 6C, Supporting Information Table S2). The tumor inhibitory effect of DAC alone was not obvious, but after combining with chemoimmunotherapy, the tumor inhibition rate of PTX + DAC+αPD-1 group was 67.17 ± 7.28%, which was significantly higher than that of PTX+αPD-1 group (P < 0.01, n = 6). Similarly, the tumor inhibition rate of P/D-mMSNs group was 72.02 ± 4.10%, which was significantly higher than that of P-mMSNs group (P < 0.001, n = 6), indicating that DAC combined with PTX and αPD-1 could improve the therapeutic effect of TNBC. The tumor volume in P-mMSNs group was smaller than that in PTX group (P < 0.01, n = 6), and the tumor inhibition rate was 56.26 ± 8.17%. The tumor inhibition rate in P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group was 90.04 ± 4.34%, which was significantly higher than of P/D-MSNs+αPD-1 group (P < 0.05, n = 6), suggesting that the drug loaded by MSNs and camouflaged with the macrophage vesica could significantly enhance the therapeutic effect (Fig. 6C and D). Furthermore, the anti-tumor effect of mMSNs or liposomes delivery systems was evaluated (Supporting Information Fig. S6). The efficacy of P/D-Lipo group was higher than that of P/D-MSNs group (P < 0.05, n = 6), which may be due to the long-circulation effect of liposomes, while the efficacy of P/D-mMSNs group was higher than that of P/D-Lipo group (P < 0.01, n = 6), which may be attributed to the camouflage of macrophage vesicle. In general, these results indicated that P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 could significantly enhance the chemoimmunotherapy effect of TNBC.

Mice were euthanized and dissected after 21 days of treatment, the tumors tissues and major organs were collected for analysis. The ex vivo tumor weights and tumor images trended in line with the tumor volume results (Fig. 6E and F). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Ki-67 immunohistochemistry and TUNEL immunofluorescence were used to analyze the proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells. The results showed that P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group had the best ability to resist tumor proliferation and promote tumor apoptosis (Fig. 6G). H&E staining was used to analyze the heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and lung, and no obvious damage was found in each group, indicating that P/D-mMSNs had no toxic effect on normal tissues (Supporting Information Fig. S7). Furthermore, the organ coefficients were evaluated (Supporting Information Fig. S8). Compared with the normal group, there was no significant difference in the weight of heart, lung, and kidney in all groups. The liver coefficient in NS, PTX, αPD-1, DAC groups were significantly higher than that in normal group, while the liver coefficient in P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 groups were similar to that in normal group, indicating the good safety of P/D-mMSNs. The spleen coefficient increased in P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group, indicating that the P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 may trigger immune response to enhance the anti-tumor effect.

3.7. Long-term immune memory effect of P/D-mMSNs

Furthermore, the potential of P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 to prevent tumor recurrence was investigated. To establish a secondary tumor model, 4T1 cells were re-inoculated into tumor-bearing mice that survived after treatment (Fig. 7A). Untreated BALB/c mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells as a control group. The growth of secondary tumors was significantly delayed in mice pretreated with P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1, while the 4T1 secondary tumors grew rapidly in the control group (P < 0.001, n = 6) (Fig. 7B, C and D), indicating that P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 elicited a long-term anti-tumor response in mice.

Figure 7.

P/D-mMSNs combined with αPD-1 exhibited long-term immune memory. (A) Schedule diagram of in vivo administration approach and secondary tumor model establishment. (B) The rechallenged tumor growth curves of tumor-bearing mice. (C) Secondary tumor photographs and (D) tumor weights of the sacrificed mice at the study endpoint, scale bar = 1 cm. (G) Flow cytometry analysis and (E) quantitative analysis of memory T cells in the spleens (gated on CD3+CD8+ T cells). (F) ELISA analysis of IFN-γ and TNF-α in secondary tumors. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 or n = 3). ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. indicated.

Effector memory T cells (TEM) play an important role in preventing tumor recurrence. The proportion of CD8+ TEM in the spleen was analyzed 20 d after rechallenge. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the proportion of CD8+ TEM in P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group increased to 43.77 ± 2.30%, which was 1.58-fold higher than that in control group (P < 0.001, n = 3) (Fig. 7E and G). Since immune cells in tumor tissue could produce cytokines to induce memory protection, IFN-γ and TNF-α in secondary tumors were measured. The P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 group showed the highest levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in secondary tumors (Fig. 7F). These results indicated that P/D-mMSNs+αPD-1 could effectively stimulate long-term immune memory effect and prevent tumor recurrence.

4. Conclusions

To improve the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy, macrophage-camouflaged nanoinducers co-loaded with PTX and DAC (P/D-mMSNs) were prepared in combination with PD-1 blockade therapy. P/D-mMSNs had the ability to enhance tumor accumulation, cellular uptake, and drug co-delivery, and improved the efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy through the demethylation of tumor tissue. On the one hand, P/D-mMSNs enhanced the sensitivity of tumor cells to PTX, and induced immunogenic death of tumor cells. On the other hand, P/D-mMSNs reversed T cell exhaustion, and facilitated immune checkpoint blockade therapy. This study provided a promising epigenetic nano-modulation strategy for improving chemoimmunotherapy in TNBC.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82173757, 82173756). The authors would like to thank Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for consultation and instrument availability that supported this work. The authors would like to thank Pharmaceutical Biology Sharing Platform of Shandong University for supporting the cell-related experiments.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.018.

Contributor Information

Yongjun Liu, Email: liuyongjun@sdu.edu.cn.

Na Zhang, Email: zhangnancy9@sdu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Tong Gao, Yongjun Liu and Na Zhang designed the research. Tong Gao carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Xiao Sang, Xinyan Huang, Panpan Gu and Jie Liu participated part of the cell and animal experiments. Tong Gao and Yongjun Liu wrote the manuscript. Tong Gao and Na Zhang revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortes J., Cescon D.W., Rugo H.S., Nowecki Z., Im S.A., Yusof M.M., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1817–1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Sullivan H., Collins D., O'Reilly S. Atezolizumab and Nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1900150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y.Y., Chen H.Y., Mo H.N., Hu X.D., Gao R.R., Zhao Y.H., et al. Single-cell analyses reveal key immune cell subsets associated with response to PD-L1 blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1578–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pathania R., Ramachandran S., Elangovan S., Padia R., Yang P.Y., Cinghu S., et al. DNMT1 is essential for mammary and cancer stem cell maintenance and tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6910. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zolota V., Tzelepi V., Piperigkou Z., Kourea H., Papakonstantinou E., Argentou M.I., et al. Epigenetic alterations in triple-negative breast cancer-the critical role of extracellular matrix. Cancers. 2021;13:713. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belk J.A., Yao W., Ly N., Freitas K.A., Chen Y.-T., Shi Q., et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens of T cell exhaustion identify chromatin remodeling factors that limit T cell persistence. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:768–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco F., Jaccard A., Romero P., Yu Y.R., Ho P.C. Metabolic and epigenetic regulation of T-cell exhaustion. Nat Metab. 2020;2:1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavalli G., Heard E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature. 2019;571:489–499. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett J.E., Herzog C., Jones A., Leavy O.C., Evans I., Knapp S., et al. The WID-BC-index identifies women with primary poor prognostic breast cancer based on DNA methylation in cervical samples. Nat Commun. 2022;13:449. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27918-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widschwendter M., Jones A., Evans I., Reiser D., Dillner J., Sundstrom K., et al. Epigenome-based cancer risk prediction: rationale, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:292–309. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson M.A. The cancer epigenome: concepts, challenges, and therapeutic opportunities. Science. 2017;355:1147–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bear H.D., Idowu M.O., Poklepovic A., Sima A., Kmieciak M. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus decitabine followed by standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced HER2-breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buocikova V., Longhin E.M., Pilalis E., Mastrokalou C., Miklikova S., Cihova M., et al. Decitabine potentiates efficacy of doxorubicin in a preclinical trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer models. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;147 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahn M.L., Cruickshank B.M., Jackson A.J., Dean C., Holloway R.W., Hall S.R., et al. Decitabine response in breast cancer requires efficient drug processing and is not limited by multidrug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1110–1122. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghoneim H.E., Zamora A.E., Thomas P.G., Youngblood B.A. Cell-Intrinsic barriers of T cell-based immunotherapy. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:1000–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Tong C., Dai H.R., Wu Z.Q., Han X., Guo Y.L., et al. Low-dose decitabine priming endows CAR T cells with enhanced and persistent antitumour potential via epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2021;12:409. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20696-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghoneim H.E., Fan Y.P., Moustaki A., Abdelsamed H.A., Dash P., Dogra P., et al. De novo epigenetic programs inhibit PD-1 blockade-mediated T cell rejuvenation. Cell. 2017;170:142–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroemer G., Galassi C., Zitvogel L., Galluzzi L. Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:487–500. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jhunjhunwala S., Hammer C., Delamarre L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:298–312. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryoo R. Birth of a class of nanomaterial. Nature. 2019;575:40–41. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou S., Zhong Q., Wang Y., Hu P., Zhong W., Huang C.B., et al. Chemically engineered mesoporous silica nanoparticles-based intelligent delivery systems for theranostic applications in multiple cancerous/non-cancerous diseases. Coord Chem Rev. 2022;452 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y.X., Quan G.L., Wu Q.L. Zhang XX, Niu BY, Wu BY, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Conza G., Tsai C.H., Gallart-Ayala H., Yu Y.R., Franco F., Zaffalon L., et al. Tumor-induced reshuffling of lipid composition on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane sustains macrophage survival and pro-tumorigenic activity. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:1403–1415. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu Y.Q., Chen T., Hu R., Zhu R.Y., Li C.J., Ruan Y.C., et al. Next frontier in tumor immunotherapy: macrophage-mediated immune evasion. Biomark Res. 2021;9:72. doi: 10.1186/s40364-021-00327-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapouri-Moghaddam A., Mohammadian S., Vazini H., Taghadosi M., Esmaeili S.A., Mardani F., et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6425–6440. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Q.Y., Guo N.N., Zhou Y., Chen J.J., Wei Q.C., Han M. The role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in tumor progression and relevant advance in targeted therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:2156–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y., Luo J.S., Chen X.J., Liu W., Chen T.K. Cell membrane coating technology: a promising strategy for biomedical applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2019;11:100. doi: 10.1007/s40820-019-0330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.