Abstract

The assessment is the first of the fundamental nursing processes: it includes data collection, problem identification, and setting of priorities, which all facilitates the process of making a nursing diagnosis. The assessment helps to identify a goal, which, through a decision-making process, orientates the planning as well as the nursing intervention, which will be evaluated at a later stage. It seems that the proposed multidimensional and integrated assessment has a good potential to significantly influence the nursing care. This model is multidimensional since it covers biophysical, psychological, socio-relational, but also the spiritual dimensions of each person, and is integrated since it’s reinforced by the inter-professional dialogue between nurses, physicians, sociologists, psychologists, and other health professionals. To come up with a diagnosis, nurses integrate the “cases” (the set of data/information collected through a “traditional” assessment), with the “stories” (which are directly narrated from the people themselves). Thus the proposed model combines quantitative instruments, typical of natural sciences (questionnaires, scales, tests and surveys), with qualitative ones, deriving from human sciences (interviews, the patient’s agenda and narratives). The complementary use of objective and subjective methods leads to valid, consistent and standardized results, and, at the same time, makes it possible to investigate unique and subjective perceptions. Several strategies are outlined in this paper, with methods, phases and instruments related to the advanced assessment model, in order to better determine the most suitable based on the person’s individual needs.

Keywords: multi-dimensional and integrated assessment, nursing, questionnaire, scales, interviews, narratives

Introduction: theoretical and epistemological assumptions

The first problem a nurse shall wonder about is: Who is the person in front of me? (1). Two different conceptions of nursing tried to answer such an anthropological question, through two different epistemological paradigms (2). These different conceptions guide both caring purposes as well as instruments and assessment methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epistemological Nursing Models

| Model | Neo-positivist | Phenomenological |

| Origin | Logical empirism | Phenomenology |

| Goal | To cure | To care |

| Subject of the Research | Single parts | Complex human reality |

| Research issues | Problems related to the disease | Experiences, emotions, histories of illness and sickness |

| Method | Nomothetic | Idiographic |

| Tools | Assessment scales, questionnaires | Interview, patient’s agenda, narration |

Adapted from Artioli, Foà, Taffurelli (2016)

The first paradigm has a positivist matrix and it originates from logical empiricism, which sets a strictly scientific point of view. As for research, such approach emphasizes observation and experimentation. The method is nomothetic, based on logical deductive thinking and quantitative instruments for measuring phenomena. The approach aims indeed to the cure and its research scope covers all disease-related issues. Thus it “splits up” the person, focusing on specific parts and aspects. This paradigm defines health in relation to the disease: the health is indeed the absence of biological damage to organs, cells and tissues (3). Thus the person might be identified by and in his own disease, leading therefore the care provider to act in an “objective” and external way. In this perspective the sick person plays a passive role, with no responsibility, relying on experts for his cure.

The second paradigm is the phenomenological-narrative one. This interpretive model is inspired by the existential phenomenology, which emphasizes human inner and complex realities and their contexts. In this model, it becomes essential how the illness itself is experienced by the person (illness) as well as its social impact, in relation with the person’s environment (sickness). Even the general conception of health is meant in a personal sense, multidimensional, dynamic and partial. This is influenced by many psycho-social (such as temperament, personality structure, cognitive and psychosocial processes, coping skills, and self-esteem) and socio-relational variables (such as the belonging to a context, interpersonal and social relationships, social integration, and trust in others and in institutions). The person, holder of specific needs, is a whole that comprises the body, that experiences and the environment (bio-clinical dimension) and also the psyche, with feelings, emotions, ideas, values and culture (psycho-social dimension). The research range therefore includes the analysis of feelings, interpretations, emotions and meaning of personal stories. This paradigm is based on the human sciences and it supports ideographic and interpretative methods. Since such approach pays specific attention to the communication/relationship, the assessment instruments are based on qualitative methods (e.g. interviews, the patient’s agenda, narratives). The narrative interviews, in particular, allow in-depth understanding of the person’s needs (4, 5). Telling someone a story about his own illness, it means to describe a series of events, consciously or unconsciously selected and putting them into connection. This “story telling” is rarely structured into a single plot, but more often hesitantly organized, in a discontinuous and fragmented manner (6). The listener has to follow the story through its narrative trajectories, striving to identify the metaphors and images (7), tolerating ambiguity and uncertainty (8)

A professional who listens to a story of illness is not a “neutral” receiver since he actively contributes to the co-construction of the story itself (9). The professionals provide cares in a relational and dialogical way (“I care” approach). The nurse’s attention therefore needs to move from a concept of health as an absence of a disease to a more systemic and complex one, involving the representation that person he has of this concept (9). The health also has dynamic feature, since it is characterized by a continuous process of evolution, seeking for the balance between the individuals and their environments (physical, social, relational, cultural).

Starting from the above assumptions and through an examination of the theoretical and epistemological models (from the Evidence Based Nursing up to the Narrative Based Nursing), we proposed an Integrated Nursing Model (for a discussion see 10). This model is a multi-dimensional since it covers biophysical, psychological, socio-relational, and spiritual dimensions of each person, and is integrated since it’s reinforced by the inter-professional dialogue between nurses, physicians, sociologists, psychologists, and other health professionals. In order to best guarantee the drafting of a comprehensive and personalized care project, this model characterizes the nursing care as the simultaneous process of curing and caring, which comprises explanation, understanding, education and guidance efforts. The Integrated Nursing Model seems very useful to set up the assessment, the assistance and the education.

The assessment, in particular, is the first of the fundamental nursing processes: it includes data collection, problem identification, and setting of priorities, which all facilitates the process of making a nursing diagnosis. It helps to identify a goal, which, through a decision-making process, orientates the planning as well as the nursing intervention, which will be evaluated at a later stage (11). Therefore, the assessment is managed through an Integrated Narrative Nursing Model is aimed at collecting data in an objective, rigorous and structured way, but also in a subjective, idiosyncratic and personal way. As to ensure a full knowledge of the person, this model uses quantitative, qualitative and qualitative-quantitative instruments in order to select all information for an advanced assessment based on the person’s individual needs (for a discussion see 12). The authors have identified 23 person’s needs that should be assessed. These needs will certainly undergo further revision and integration in the next future (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main person’s needs

| Rest and sleep |

| Motion |

| Self care |

| Nutrition |

| Intestinal Evacuation |

| Urinary Evacuation |

| Functionality of the Cardiovascular System |

| Functionality of the Respiratory System |

| Tissue Integrity |

| Termal homeostasis |

| Safety |

| Pain |

| Body Image |

| Cognitive Perception and Sense |

| Communication |

| Self-esteem and Self-efficacy |

| Past, Hopes and Expectations |

| Quality of Life |

| Mood |

| Stress Adaptation, resilience and coping strategies |

| Therapeutic Adherence and self-empowerment |

| Spiritual and values -related dimension: culture and ethnicity |

| Socio-cultural dimension: person, family, community |

From: Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

As seen in Table 2, some needs are bio-medical (e.g. rest and sleep, movement, nutrition, respiratory and cardiovascular functionality), others are psycho-social (e.g. communication, adaptation to stress, resilience and coping strategies, mood, self-esteem, and self-efficacy) while others are socio-cultural-spiritual (e.g. feelings, hopes, expectations, family, community, ethnicity). Moreover, there are other needs, such as the freedom from pain, that are placed on the border between these different perspectives. Freedom from pain is not only one of the most important healthcare objectives but it perfectly exemplifies the complex interconnection between the bio-psycho-social dimensions of the health and of the disease experiences (for a discussion sees 13).

Besides being one of the major healthcare problems, the pain is a multidimensional experience as it includes physical, social, psychological and spiritual dimensions, with both acute and chronic components. Pain is also an integrated experience which, to be managed, requires a dialogue between different professionals, such as physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists and other health professionals. After the paradigmatic shift from the pain as a symptom to the pain as illness, and from a healing perspective to a caring one, the attention is set on the patients’ participation. Thus the commitment of health care organizations for the establishment of appropriate services to pain treatment has fostered the further development of competences (technical, relational, educational) to be applied to the assessment and treatment of pain, even through programs of ongoing education for the professionals of this field.

From theory to the method: assessment scales and relationship instruments

As explained above, the multi-dimensional and integrated assessment here proposed combines objective scientific instruments, typical of natural sciences (measurements, scales, tests and surveys), with qualitative methodologies, deriving from human sciences (interviews, the patient’s agenda and narratives). The qualitative assessment in particular is focused on understanding the person’s subjective experience, such as the way the person lives own path, evolution, adaptation and response to the illness. Thus it is focuses on feelings, emotions, interpretations, expectations and person’s values, keeping into consideration the socio-relational condition he/she belongs to. The goal is giving consistency, evidence and concreteness to what is indefinite, unstable and variable, which influences the need’s perception and their external expression. The assessment therefore becomes “person care”: the experience of illness is represented and told, events have meaning and coherence and experiences associated with the events are described according to the prevalent meaning for the people involved (5).

Thus the questions that the nurse poses to the person or to the caregiver are aimed at integrating, expanding, deepening and personalizing the objective observation and the measurement, with a complex, holistic, complementary and integrated point of view.

The bio-physiological dimension investigates the functionality of the need and helps the person to highlight the perception he has of his own organic and functional dimensions. Such approach integrates the physical examination of the patient with the person’s subjectivity. The psycho-social dimension examines: the emotional reactions towards possible limitations and their impact on psychological needs (such as self-image, self-esteem, mood); the family environment, and the social relationships; the information that person and family need; personal values, beliefs, principles, religion and guiding ideas (14).

Even though we are aware of their incompleteness, we will briefly describe several strategies (phases and related instruments) related to the integrated and multidimensional assessment model here proposed, in order to better determine the most suitable tools to be used in persons’ needs assessment.

a) The observation of the need and of the related needs

This phase aims to assess the functionality and the possible alteration of the need. The observation of the person is crucial in order to properly characterize the experience and try to understand and interpret symptoms and signs, therefore providing adequate care responses.

The need is considered in its two main components, the bio-physiological and the psycho-social, whose parameters are observed and measured in both normal and pathological stages.

It defines the normality pattern and signs and symptoms revealing the modification of the need.

About the need that we consider, the freedom from pain, the nurse observes the bio-physiological dimension (e.g. body regions involved, systems involved, temporal characteristics, intensity, aetiology of the pain), and the psycho-social dimension (e.g. aggravating/relieving factors linked to the experience and to its relapse in everyday life).

The nurse afterwards focuses on the observation of the related needs, as to determine how modification of the considered need can influence other needs. An in-depth analysis of the need is performed, along with, at the same time, a horizontal assessment of all other needs of the person. In the case of the pain, there is a relevant amount of related needs. Pain, in fact, is related with alterations in bio-physiological (e.g. sleep, nutrition, movement, self-care), psycho-social dimensions (e.g. self-esteem, mood, coping strategies, values, beliefs, religion, culture).

b) The measurement of the need

The goal of this this phase is the measuring of the need as objectively as possible, using tests, questionnaires, scales and other quantitative instruments. In particular, the assessment scales quantitatively detect a phenomenon and the clinical data and allow the measurement of any changes over time. Such a scale facilitates a comparable reading of caring processes, allowing a quali-quantitative evaluation of the requested care. It also provides a common and standardized language as well as concepts exactly operationalized as variables. Thus different professionals using the same tool may therefore easily reach the same conclusions. The instruments used in this phase are several and differentiated according to the need they apply to and they focus on specific multi-dimensional or one-dimensional evaluation. Each instrument usually has specific recommendations, validation and cut-off criteria. The assessment scales need to meet also the criteria of validity, sensitivity, internal consistency, repeatability, reliability and they must be easy to use. The assessment scales require adequate information and a proper degree of comprehension of the person under assessment. Where necessary, the nurse can share with families and other professionals the information about operating procedures. This can be especially useful in cases of chronic illness when discharge and home care are approaching.

The subjective scales for pain assessment can be classified into one-dimensional scales (measuring pain intensity) and multidimensional, evaluating different dimensions and pain levels (e.g. sensory-discriminative, motivational-affective, cognitive-evaluative).

The qualitative one-dimensional scales include the continuous chromatic analogical scale and the scale of facial expressions. The quantitative one-dimensional scales include the Verbal Numeric Scale (VNS), the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), the Visual Analogical Scale (VAS) and the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS). Table 3 shows some examples of one-dimensional scales.

Table 3.

Pain: examples of monodimensional scales

| Scale | Methods of administration | Valid for |

| Verbal Scale(VBS) | Verbal and/or Visual | Chronic Pain |

| Visual Analogue Scale(VAS) | Verbal | Acute Pain |

| Relief -scale (variation of VAS) | Verbal | Pain Relief |

| Verbal Numeric Scale (VNS) | Verbal | Chronic or Acute Pain |

| Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) | Verbal | Acute Pain |

| Visual rating scale (VRS) | Visual/Verbal | Acute and Chronic Pain |

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Visual | Chronic or Acute Pain |

| Rheumatic Disease | ||

| Children> 5 years | ||

| Numeric Scale (NSR) | Verbal/Visual | Chronic or Acute Pain |

| Rheumatic Disease | ||

| Oncological Pain | ||

| Traumatic Pain | ||

| Analoug chromatic continous scale (ACCS) | Visual | Chronic or Acute Pain |

| Facial Expression Scale | Visual | Chronic or Acute Pain |

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

Multi-dimensional scales to assess the pain are very numerous. Among these, for example, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale, together with the McGill Pain Questionnaire, the Brief Pain Inventory, the Descriptor Differential, the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale and the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pain: examples of multidimensional scales

| Scale | Methods of | Valid for administration |

| Edmonton symptom assessment scale (ESAS) | Visual | Daily assessment of oncological patients undergoing palliative care. It assesses quality of life and pain through 3 different dimensions: sensory-discriminative; affective-motivational; cognitive-evaluative |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire | Verbal and Visual | 78 pain descriptors (assessing sensory, affective and evaluative dimensions) are divided in 20 items assessing 4 measures of clinical pain: sensory; affective; evaluative; miscellaneous. There is also an human body schema |

| Brief Pain Inventory (Short form) | Verbal and Visual | It assesses most common oncological pain. 15 items assesses the presence of pain during last 24 hours, its position, intensity, relief, and its impact on quality of life (7 areas of psychosocial and physical activities) |

| Descriptor Differential Scale | Verbal and Visual | It assesses sensory intensity and complaint |

| Pain Assessment In Advanced Dementia scale (PAINAD) | Verbal and Visual | For patients with severe cognitive impairment. It assesses 5 indicators: breathing; negative vocalization; facial expression; body language; consolability |

| Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) | Self-report | It assesses the subjective distress and the impact of pain on patient’s lives (life interference, support, life control, pain severity, affective distress); the responses by significant others (distracting, negative or solicitous) and the activities (households, activities away from home, social activities, outdoor work) |

| West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain inventory (WHYMPI) | Self- report | It assesses chronic pain. 52 item investigating: perceived interference of pain in vocational; social/recreational, and family/marital functioning; support or concern from spouse or significant other, pain severity, perceived life control, and 5 affective distress |

| Pain Disability Index (PDI) | Self-report | It assesses chronic pain. 7 items assess the degree to which aspects of patient’s life are disrupted by chronic pain, such as: family/home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self care, and life-support activities |

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

Other tools might also be considered, such as the pain diary, which hinges on an accurate recording by the patient of his common daily activities: patient is asked to write down the intensity of pain related to particular behaviours (e.g. sitting, standing, walking, relaxing); specific tasks; intake of analgesic drugs; meals; sleeping and sexual activities; household and recreational activities. Using also the pain map, the patient indicates the parts of a human body or a diagram, where he is feeling pain in a given moment. This mapping can be easily handled by non-specialized staff: it becomes extremely practical for the recording of the exact point and the distribution of pain and for the determination of the body percentage affected by pain.

There are several other instrumental blood tests that help pain assessment and detection: for instance some changes can be measured in glycaemia, nitrogen, coagulation, blood count.

c) “Giving a voice” to the illness experience

This phase aims to gather and co-construct the history of patient’s illness, in an ideographic manner. To set up and conduct a good interview (not unplanned, uncertain, nor occasional) it is necessary to pay attention to the preparation of an appropriate setting, in view of encouraging an inter-subjective dynamic: this will concern the inner condition of both the professional and the patient and the “external setting” respectful of the person’s privacy.

A careful listening necessarily includes a real interest in observing and perceiving the thoughts, the mood, the personal significance that the person gives to his message. An “active” listening requires harmony between to list the verbal language and to observe the analogical-nonverbal one. The interview is thus a communication in which the nurse plays an active role with a dynamic commitment to understanding the person who, on the other hand, needs to show a real interest in understanding and clarifying the experience he is living.

As we have seen, the narrative interview is set up as a merely qualitative methodology to add value to stories, emotions and subjective perceptions of illness. This instrument helps the person showing his own concerns and allows the nurse to act in order to help the person having a clearer sight of his personal illness experience (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pain: examples of narrative interview

| Investigated Area | Trigger Questions | Key Words |

| Story of the illness | Just talk me about you… When did your problem begin? Did your life change after this experience? If yes, how? |

Perception of the personal story of the pain Meaning given to the pain and to the illness Future development of the life and the illness (real/preceived threat to wellbeing) |

| Story of the pain | What kind of effect has the pain on yours everyday life? | Physical effects: motion, nutrition, sleep and rest Psychological effects: anxiety, fear, depression Social effects: social retirement, loneliness. Spiritual effects: spiritual beliefs and values |

| Pain Management | What kind of expectations do you have on your pain management/control? What kind of difficulties do you think you will experience with the pharmacological treatment? |

Supporting health facilities Clinical evolution of the pharmacological research and disease Personal believes on pharmacological treatment Therapeutic information Adverse drug reaction (opioids, painkillers) |

| Coping Style | How and through which (mental and behavioral) strategies do you think you can cope with pain and its treatment? | Acceptance Avoidance/denial Active coping Positive attitude Trascendent approach Seeking for social support |

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

The semi-structured interview uses clusters of significant questions related to bio-physiological and psycho-social dimensions of the needs.

In Table 6 an example of a semi-structured interview for the assessment of pain is shown.

Table 6.

Pain: examples of semi-structured interview

| Addressed Dimension | Examples of guide questions |

| Bio-physiological related | Which words would you choose to define your pain? Which are the features of your pain? Could you indicate where you feel pain and describe its intensity? In which moment of the day does you pain arise? How much time does your pain last? Are there some factors worsening or relieving the pain? |

| Psycho-social and values-related | How are you living this experience of pain? Who is the person you talk with about your pain? Are you willing to talk about how you express your pain? What is the meaning you give to your pain? Do you want to know aims and effects of potential painkiller treatments? What gives you strength and hope, in this experience of pain? |

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

According to the conceptualization proposed by Moja and Vegni (15) patient’s agenda is also a valuable tool for exploring what the person brings with himself when requires the intervention of the health professional. It is organized in four dimensions: feelings; ideas and interpretations; expectations and desires; contexts.

Recognizing the universality of the four areas, we cannot predetermine the agenda content, which will be specific to that patient in that situation of illness, although the conceptualization in four dimensions is a valuable complementary instrument to the interview.

In Table 7 examples of the patient’s agenda about the experience of pain have been highlighted.

Table 7.

Pain: examples of patient’s agenda contents

| Agenda Areas | Examples of guide questions |

| Feeling | Which are your feelings about pain? How do you feel when you talk about what is happening to you? |

| Ideas/Interpretations | What do you think about the pain you are experiencing or you have experienced? Which explanations did you give to yourself? |

| Expectaions/Desires | What do you think is going to happen over the next period? What could make your pain more bearable? |

| Environment | How was your life before the pain? Did pain affect your environment? (family, work, friends) If yes, how? |

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

d) Assessment of potential problems

Investigating a need is not enough. In a systemic perspective, making connections between the need (main object of evaluation) and modified needs, arising from the repercussions that the unsatisfied need determines, has a significant preventive meaning. The aim, in this phase, is to provide some perspectives and assumptions on the assessment of potential problems of the patient, using in particular the guide questions and the concept maps.

There are some questions, in fact, that the nurse should pose, after the first assessment of the person, as to verify whether, according to collected data, there is a risk of developing potential problems. The guide questions investigate the possible repercussions of the unsatisfied needs on other areas and the possible problems both in the bio-physiological and psycho-social dimensions. Taking the pain as example, the detection of potential problems may be triggered through guide questions like: how much the presence of pain affects the person’s safety and comfort? How much pain prevents the normal cycle of daily activities? Does age, impaired cognitive status and communication, affect the person’s ability to express the pain? Has the person enough physical and psycho-emotional resources to cope with the experience of pain? Are the person’s significant others at risk for emotional breakdown?

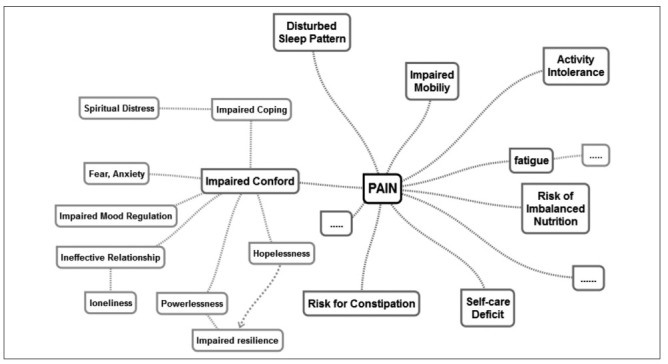

The concept map, instead, through its graphic immediacy helps to organize data since it uses diagrams to show the relationship of a concept or a given data with other concepts or other data. “As a geographical map helps to orient ourselves in a territory, a concept map is an instrument to interpret, re-elaborate and share knowledge, information and data, visualizing the subject of the communication, the main concepts, the bonds that they establish, and consequently, the path of the reasoning”(16). This allows representing and explaining the relationships among the assessment data and understanding whether there are sufficient data to support a diagnosis. The concept maps, therefore, constitute a powerful instrument to obtain an adequate representation of knowledge as well as its sharing and co-construction (17) as they help to think about the nature of acquired knowledges and relationships between them. The following figure shows the concept map of the pain.

Figure 1.

Concept map of the pain

Adapted from: Foà, La Sala, Tonarelli, Taffurelli, Sestigiani. In Artioli, Copelli, Foà, La Sala (2016)

Concluding remarks: the development of critical thinking and decision-taking

Much progress has been made in nursing history, in defining the human being and seeking the best ways to build a relationship with the person, keeping his real needs into consideration.

As we have tried to expose, the nursing assessment has a multidimensional connotation because it addresses the person, in all of his dimensions (bio-physiological, psychological, socio-cultural, spiritual and values-related) and because it responds to the complexity paradigm of the human nature.

Using the narratives in nursing assessment does not mean only to individually re-elaborate the patient’s own illness experience. It is instead a negotiation of meaning (or a common remodelling of the different interpretations of his story) between nurse and patient, willing to create a new comprehension of the illness through empathic involvement (3, 8).

Integrating a neo-positivist nursing assessment with a phenomenological-narrative approach fully realizes the process of nursing care, in which the assessment of needs allows the definition of a personalized care plan, integrated and multidimensional, aimed to meet the needs of the person.

The perspective proposed in this paper seems to have a good potential to significantly influence the nursing care. First of all because it acknowledges to the person’s assessment the proper importance and significance that inherently possesses.

In addition, the integrated use of objective and subjective methods allows to achieve valid, consistent and standardized results, and, at the same time, allows to investigate the unique and subjective perception, absolutely relevant to each person: standardization and customization of care intertwine and integrate each other to achieve high levels of nursing care quality.

We can, moreover identify some effects linked to the development of nurses’ professional skills. Using methods coming from two conceptual models not overlapping, requires specific skills in understanding the signs and symptoms of a disease and the idiosyncratic experience of the person also. Nurses should integrate the “cases”, meant as the set of data/information collected through a “neo-positivist” assessment, with the “stories” directly narrated from the people, which are then interpreted narratively (18). Cases and stories are used together to achieve a nursing diagnosis.

This nursing assessment model, which uses quali-quantitative approach, seems to have positive implications for the patient, especially as it increases his perception of being authentically understood. The person, therefore, as an expert of his illness, consulted and empathically listened, will shift from the implementation object of scientific knowledge, to main character of his own care. Only the active involvement of the person guarantees that the understanding of human responses to illness becomes one of the priority aims of the caring process, raising the approval rating and the satisfaction for the received cares.

This, of course, implies accepting the complexity of this kind of assessment process, which constitutes the weak point of this approach in its practice. But on the other hand, the complexity paradigm, which connotes the human being, has to be part of the methodologies and tools that are used to understand him. The person’s assessment is not a simple collection of information and a transcription on nursing documentation, but implies a multidimensional active thinking.

It requires appropriate observations and measurements, as well as the formulation of relevant and targeted questions to distinguish relevant and important data from those irrelevant and secondary. Knowing how to make inferences and to formulate hypothesis completes the nurse’s professional skills. Knowledge and skills developed in this way, together with the development of prospective reasoning skills, allow the professional to intervene in the current risk management. This requires adequate knowledge and good ability using critical thinking, essential to organize data, classify them effectively, understand what information is needed and where and how to acquire it, by establishing the most appropriate assessment methods.

For critical thinking we mean intentional mental activity, through which we process and evaluate ideas and make judgments. Critical thinking requires reflection to analyse the phenomena, integrating previous experiences and exploring alternatives. This way of thinking opens a window of opportunity and helps reflecting on the advantages of each of them. Critical thinking also involves creative thinking. Thinking creatively means leaving rigid patterns, in order to deal with situations from new points of view, establishing new relationships between thoughts and concepts and making inferences from the data (19). When assessing a person, it is also important to develop, along with critical thinking, the ability of decision-making. Decision making is the process needed to determine the appropriate action to be performed: it indicates reflection, evaluation, choice. The decision-making process is then used when, within many choices, a proper assessment needs to be adopted, or when among different available instruments, it is necessary to pick the most suitable based on circumstances and on person’s needs (11).

References

- Buber M. Il principio dialogico e altri saggi [The dialogical principle and other essays] Milano: S. Paolo Edizioni; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Marcadelli S, Artioli G. Nursing narrativo. Un approccio innovativo per l’assistenza [Narrative Nursing. A new approach for caring] Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli Editori; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giarelli G, et al. Storie di cura. Medicina narrativa e medicina delle evidenze. L’integrazione possibile. [Stories of care. Narrative Medicine and Evidence Based Medicine. The possible integration] Milano: Franco Angeli; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giarelli G, Maturo A, Florindi S. Il malessere della medicina: Un confronto internazionale [Discomfort in medicine: an international comparison] Milano: Franco Angeli; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Good BJ, Del Vecchio Good MJ. Il significato dei sintomi: un modello ermeneutica culturale per la pratica clinica [The symptoms meaning: a cultural hermeneutical model for the practice], in Giarelli G. et al. Storie di cura. Medicina narrativa e medicina delle evidenze. L’integrazione possibile. [Stories of care. Narrative Medicine and Evidence Based Medicine. The possible integration] Milano: Franco Angeli; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Launer J. Narrative-based.Primary Care. Abing-don, UK: Racliffe Medical Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci R. Manuale di Medical Humanities [Manual of Medical Humanities] Roma: Zading; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charon R. Narrative medicine. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:862–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannini L. Medical Humanities e medicina narrative [Medical Humanities and narrative medicine] Milano: Raffaello Cortina; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Artioli G, Foà C, Taffurelli C. An integrated narrative nursing model: towards a new healthcare paradigm. Acta Biomed. 2016;87(4):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Duncan G, Baumble W. Fondamenti di infermieristica. Principi generali dell’assistenza infermieristica. [Basics of Nursing Science. General assumptions of Nursing Care]. Seconda edizione. Napoli: EDIses; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Artioli G, Copelli P, Foà C, La Sala R. Valutazione infermieristica della persona assistita-approccio integrato [Nursing assessment of the person – integrated approach] Milano: Poletto Editore; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foà C, La Sala R, Tonarelli A, Taffurelli C, Sestigiani F. Artioli G, Copelli P, Foà C, La Sala R. Valutazione infermieristica della persona assistita-approccio integrato [Nursing assessment of the person – integrated approach] Milano: Poletto Editore; 2016. Dolore [Pain] [Google Scholar]

- Artioli G, Foà C. Valutazione della complessità della persona: verso un approccio quali- quantitativo integrato [Assessment of person’s complexity: towards an integrated quali-quantitative approach]. In Artioli G, Copelli P, Foà C, La Sala R. Valutazione infermieristica della persona assistita-approccio integrato [Nursing assessment of the person – integrated approach] Milano: Poletto Editore; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moja EA, Vegni E. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore; 2000. La visita medica centrata sul cliente [The medical examination client centred] [Google Scholar]

- Gineprini M, Guastavigna M. Mappe concettuali nella didattica [Concept maps in didactics] Retrived from Pavonerisorse: http://www.pavonerisorse.to.it/cacrt/mappe . [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Gowin D. Imparando ad imparare [Learning to learn] Torino: S.E.I; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Artioli G. I modelli assistenziali in oncologia: scale di valutazione e approccio narrativo [The care models in oncology: rating scales and narrative approach]. Contributo orale al [Oral contribute at] IV Congresso Nazionale Associazione Italiana Infermieri di Area oncologica “Modelli e strumenti assistenziali: fare la differenza in oncologia”[IV National Congress of Italian Association of Nurses in Oncology Area “Models and assistance instruments: make a difference in Oncology”]. Milan, 20-21/11/2015 [Google Scholar]

- Lunney M. Il pensiero critico nell’assistenza infermierisitica [Critical-thinking in Nursing Science] Rozzano: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana; 2010. [Google Scholar]