Abstract

Private equity (PE) investment in gastroenterology practices has significantly increased over the past several years. Because PE firms are prevented legally from owning a medical practice in many states, they usually form a management services organization to oversee all nonclinical aspects of the practice, leaving all clinical functions to the physician owners. Gastroenterology practices have become attractive investments to PE firms because of the willingness of gastroenterologists to join a PE-backed practice and the potential to earn profits through consolidating the market. Research has started to examine the effects of PE-backed practices on patients and on the gastroenterology specialty specifically. Questions remain regarding the benefits for physicians. This article examines PE investment in gastroenterology practices and how this may impact the specialty in the future.

Keywords: Private equity, management services organization, gastroenterology practice, health outcomes

Private equity (PE) firms invest in privately owned companies that have no shares available to trade on public exchanges. In contrast to venture capital, which focuses on rapidly growing startups that may just be an idea,1 PE firms usually target mature businesses suffering from operational inefficiencies.2 Investments in such companies are made in exchange for an ownership stake, or equity—hence, the term private equity.3

In a typical PE firm, a group of individuals will invest a portion of their own money along with the money of others. These others are called limited partners (LPs), and those who originally formed the firm are called general partners (GPs). LPs are frequently accredited institutional investors such as college endowments, corporations, and pension funds. Leveraging the LPs’ money, PE firms can become the majority owner of a company. To de-risk such an investment, PE firms will own a majority stake in many companies at once. The fixed pool of money invested in multiple companies from which the firm hopes to profit is called a private equity fund, and these investments are called the firm’s portfolio companies. Focusing on physician practices as potential portfolio companies, the strengths of an attractive practice for investment include: (1) potential for consolidation across a region, (2) projected increased demand for services by an aging patient population, and (3) ability to generate revenue independent of insurance contracting.4,5

Most PE firm profits are realized from sales of portfolio companies after several years, having transformed such companies into stronger businesses. GPs make money through collecting management fees, usually 2% of the LPs’ money that is being invested, and performance fees that approximate about 20% of the profits from the investment.6 Typically, LPs retain the remaining 80% of the profits. This compensation structure incentivizes a PE firm to increase the productivity and operational efficiencies of its portfolio companies.7,8 The PE firm further increases the value of its companies through access to favorable financing and improved governance.9–12

Beyond gastroenterology and medicine, PE firms are becoming entrenched across society. For example, when a customer purchases lunch from a fast-food restaurant, that meal could be purchased from a PE-backed firm.13 This same sense of ubiquity combined with anonymity may soon apply to several physician practices if it does not already. Over the past several years, PE firms have been significantly accelerating their investment in gastroenterology practices.14,15 Today, nearly 10% of US gastroenterologists are part of PE-backed practices,16 which did not even exist a decade ago.17,18 This article explores how such changes arose and what they may mean for the future of the specialty.

Relationship Between Private Equity Firms and Physician Practices

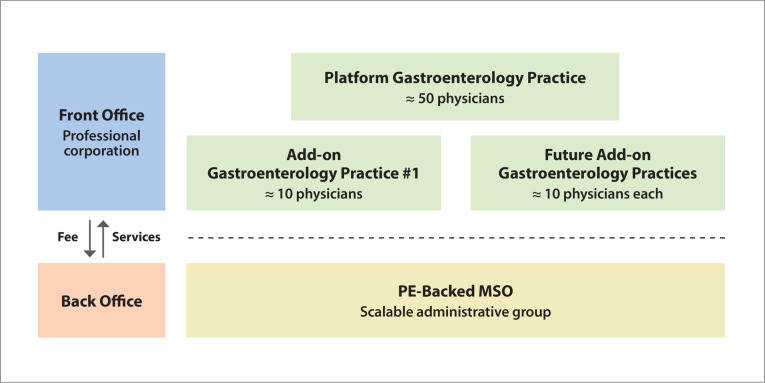

Owing to legal restrictions such as the corporate practice of medicine doctrine, which varies across states and prevents nonmedical practitioners from owning a medical practice, PE firms do not usually purchase medical practices directly.19 Instead, they form a management services organization (MSO), which can also be referred to as a physician practice management company. The MSO oversees all nonclinical aspects of the practice, including administrative and back-office operations such as information technology, human resources, and revenue cycle management, while leaving all clinical functions as part of a professional corporation controlled by the physician owners (Figure 1).20 With their responsibilities in direct patient care and clinical decision-making, physicians run the professional corporation. The relationship between the MSO and professional corporation will be formally described in a practice’s management service agreement. This agreement specifies the fee paid by the professional corporation to the MSO and what services the MSO will provide in return.

Figure 1.

When private equity (PE) firms back gastroenterology practices, they may form a management services organization (MSO) that is responsible for the administrative aspects of a practice. PE investors own a majority share of this MSO and can offer the leadership of the practices an ownership stake as well. In exchange for having an MSO to take care of back-office tasks, the practices pay a fee to the MSO. The same MSO can service multiple gastroenterology practices as PE firms seek to enhance the performance of various practices through mergers and acquisitions. Part of the strategy to attract a lot of gastroenterology practices involves partnering with a large group first, called the platform practice, and then acquiring smaller add-on practices—leveraging the same MSO for all entities, which is illustrated by the real-world example highlighted in Figure 3.

PE firms make money not only through the MSO fee, but also through economies of scale (a proportionate saving in costs when the level of production increases) because the same MSO partners with several other physician practices.4,21 As such, PE firms typically target platform practices. These types of practices are usually large, well-branded practices that enable expansion through other smaller practices.

State of Gastroenterology Practices Before Private Equity Investment

The organization of gastroenterology physicians continues to evolve over time. Prior to the managed care revolution in the 1990s that led to an emphasis on multispecialty group practice, many physicians chose to work in solo or small-group practices.22,23 As it became clear that managed care would not thrive, the insurance landscape liberalized access to specialists. Over time, it became easier to provide imaging and surgical services on an outpatient basis,24 leading to the formation of single-specialty groups that may have ownership stakes in ambulatory surgery centers.25,26 At the same time, health care policy incentivized vertical integration across specialties, leading more physicians to become employees rather than owners of their practices.27,28

Epidemiologic studies further highlight the decline of independent gastroenterology groups with a recent drive toward consolidation.29 Over the past 10 years, the number of practices with 3 to 9 physicians decreased 41%. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the number of practices with more than 500 physicians increased by two-thirds.

The COVID-19 pandemic further threatened independent gastroenterology practices. During this time, revenue significantly decreased as many practices operated at less than 10% of endoscopy capacity and canceled or rescheduled in-person clinic appointments.30 This caused many physicians to look for ways to stabilize their finances. These independent practice owners desired to maintain independence from hospital employment, retain clinical autonomy, free themselves from administrative responsibilities, stabilize revenues, and maintain growth.4,31,32 Some physicians sought to retire early and sell their ownership stake—ready to accept a decrease in pay from clinical duties in exchange for money to be earned from prior business success, often at higher rates than traditional acquirers such as earlyor mid-career gastroenterologists.4 Given the fragmented state of gastroenterology practices, PE firms found an attractive investment opportunity anchored on the promise to give physicians exactly what they think they need.

Why Gastroenterology Practices Are Attractive Investments

In addition to finding that many gastroenterologists were willing to join a PE-backed practice, PE firms found such an investment attractive because of the returns they could earn through consolidating the market.6,33 For example, GPs at a PE firm may identify a prominent and wellbranded gastroenterology group in 1 city. If successfully acquired, GPs could leverage the practice’s reputation by attaching this brand to many newly acquired smaller practices in a similar geographic area. On the back end, the PE-backed practices will have an MSO with some of the latest technology and advances in efficient management to enable all practices to operate smoothly. In theory, gastroenterology practices backed by this MSO will have a market advantage because independent practices will not be able to afford or invest in such processes or benefit from similar economies of scale. Eventually, the PE firm can corner the market, having the power to negotiate more favorable rates with insurers.34

This merger and acquisition model has seen much success in other health care fields, evidenced by increasing PE involvement in the space.35,36 For example, Heartland Dental has been supported by a variety of PE firms and has grown through mergers and acquisitions to include over 1000 dental practices today.37,38 Dermatology,39 eye care,40,41 fertility,42 orthopedics,43 urology,44,45 and oncology46 are also showing increased PE activity. This model is just one way for PE firms to grow a gastroenterology practice. Generally, such a PE-backed practice could add physicians to existing locations if the patient population warrants additional demand for services, or the practice could seek to increase the productivity of existing physicians and consider offering additional ancillary services.47 The strategies to successfully operationalize these growth mechanisms depend on the culture, skill sets, and resources within individual practices, and all strategies inevitably have varying impacts on patients that remain to be fully elucidated.

The key for a successful MSO transaction involves unlocking long-term profitability and growth potential— for the PE firm. Therefore, PE firms aim to have contractual elements that encourage such a trajectory. These elements may include an earnout clause, stipulating that the physician selling their practice can receive additional compensation in the future if certain financial targets are met. These elements may also include noncompete agreements, preventing physicians from immediately leaving for neighboring practices.48 Such elements encourage physicians to maintain the productivity of the existing practice, keeping it on sound financial footing. Furthermore, after physicians with an ownership stake retire, the PE firm may hire junior doctors and not offer MSO ownership, enabling the PE firm to retain more profits.34,49

Effects of Private Equity Investments in Gastroenterology

The effects of PE ownership in gastroenterology are only recently being studied. Notable conclusions include increased costs of services, more visits by new patients, and increased esophagogastroduodenoscopy utilization absent any increase in total number of polyps or tumors removed.50 Specifically, when focusing on PE-backed dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology practices in aggregate, Singh and colleagues found an average increase of $71 (+20%) charged per claim and $23 (+11%) in the allowed amount per claim, with a 26% increase in the number of unique patients seen, largely driven by a 38% increase in new patient visits. Although no significant changes in risk scores were noted, increases in coding intensity of evaluation and management visits were detected. The authors of this study note that all the observed changes may be part of the overall business strategy associated with PE management of a practice but do not anchor on what is responsible for these changes. To increase revenue, one needs to increase either prices or volume of services provided, and it appears as if PE-backed practices are effectively doing both. However, how exactly prices are increasing or more patients are visiting the practice remains ambiguous. The authors comment that increased volume could reflect overutilization of profitable services, unnecessary/low-value care, and/ or more effective marketing, among other tactics. Higher prices could relate to more efficient charge capture, higher intensity coding, higher negotiated prices, patients being offered higher-priced services, or other causes. Therefore, PE ownership could lead to increased costs for patients and health insurers, and increased revenues and thus profits to owners, which could imply that PE-backed practices are a net negative for society. Although on the surface this may seem true, the real question is whether there are improved outcomes resulting from this more expensive care delivery (ie, whether PE-backed practices are providing value in health care).

Although evidence remains absent in gastroenterology, recent efforts have delved into this critical question in other fields. Some studies suggest that for-profit motivation pressures practices to overtreat and rely on low-cost providers,34,51 which leads to diminished care quality.52–54 Other articles endorse this push toward overutilization, claiming that the health care system will ultimately become more efficient as a result.55 Yet, literature cautions that the sequestration of the most profitable medical procedures could imperil the ability to best care for the population as a whole.42,55,56 However, the quantitative data supporting any of these claims are not definitive. Observational studies to date have focused mostly on nursing home and inpatient hospital settings and demonstrated mixed results. For example, one study identified a 10% increase in short-term mortality of Medicare patients living in PE-owned compared with non-PE–owned facilities.57 Another observational study suggested a small improvement in efficient care processes related to treating acute myocardial infarction and pneumonia within PE-owned compared with non-PE–owned facilities in a hospital setting.58 Ultimately, performance on process measures cannot imply improved health outcomes. In the future, population-level observational studies will be needed to account for variability in external factors such as state and local policy and coverage variability that directly inform PE-backed operational management strategies and may also independently affect patient outcomes.47,59

Current Major Players and Trends

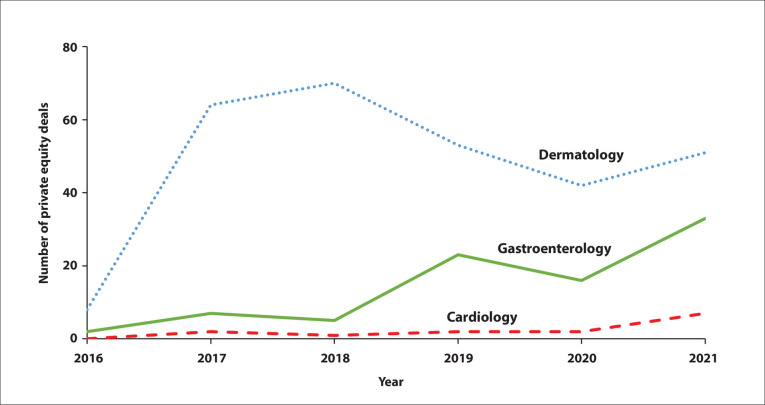

PE acquisition activity continues to trend upward across procedural specialties (Figure 2). Recognizing that health care has been increasingly migrating outside of hospital settings, several newer deals are focusing on traditionally hospital-owned specialties such as cardiology and orthopedics along with ownership of care settings such as ambulatory surgery and infusion centers.60

Figure 2.

Annual count of private equity deals by specialty. Compiled from PitchBook data.60

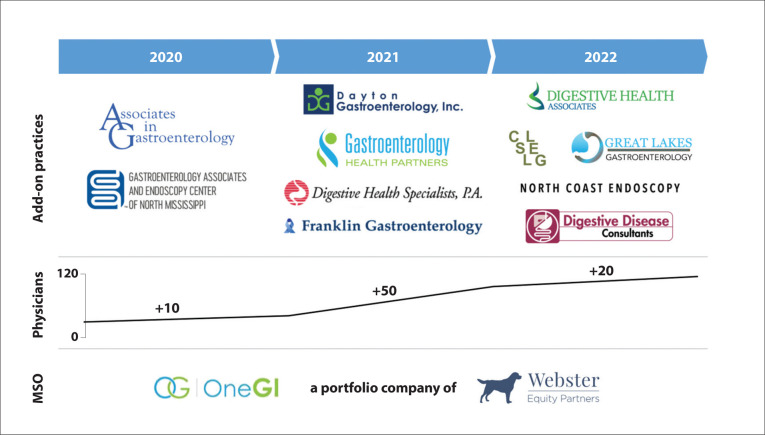

Several large PE-backed practice management firms are growing their footprint in gastroenterology.60 According to PitchBook data, the PE firms completing the most deals thus far include Waud Capital Partners, Audax Group, OMERS Private Equity, Frazier Healthcare Partners, Kelso, and Webster Equity Partners. Major PE-backed practice management solutions include Gastro Health, Allied Digestive Health, United Digestive, PE GI Solutions, and One GI.61 Another major practice group is GI Alliance, which was backed by Waud Capital Partners and recently bought out by a group of physicians facilitated by a $785 million investment from Apollo.62 As one of the largest groups, with nearly 700 participating physician members across 14 states, GI Alliance has a significant presence in the southern United States.

One GI serves as a case study of the potential rate of PE-backed practice growth (Figure 3). Within 2 years of acquisition by Webster Equity Partners, the number of physicians more than quadrupled, and the geographic footprint expanded to include practices in 6 different states. This expansion may be an underestimate of the growth of One GI, as not all transactions are listed in PitchBook and/or the company website at the time of publication.63 Headlines noting One GI acquired 30 practices64 (beyond 11 acquired practices shown in Figure 3) further this claim. The difference in numbers likely reflects the acquiring of several small practices that may consist of a single physician.

Figure 3.

In early 2020, Webster Equity Partners purchased Gastro One, the platform practice that gave rise to the management services organization (MSO) One GI. Over 2 years after its founding, more than 11 add-on practices have been subsequently incorporated. This brings the number of physicians that are a part of the platform to greater than 110. Although several larger platforms exist, this example highlights how rapidly the number of practices and physicians working with private equity is increasing.

Although small practice acquisition increases an MSO’s footprint, the potential benefits may not always outweigh acquisition costs. PE firms have a fixed amount of investment capital. A single solo-practice acquisition typically sells for such a small amount of money relative to fund size. Considering the costs of due diligence that are needed to support an acquisition, the potential return on investment in absolute dollars from a small purchase may not be attractive to the PE firm. Instead, the PE firm can gain a more sizeable absolute return by investing the same amount of time in the potential acquisition of a larger physician practice.

Questions About the Future

Although separation of the MSO from the professional corporation mitigates the ability of PE firms to bring the question of profitability into medical decision-making, financial incentives are still not fully aligned to deliver value. Dermatology practices serve as an ideal case study. As PE firms entrenched themselves within this space, providers interacting with such firms reported pressures to meet certain volume targets for procedures, upcharge visits, generously use physician assistants, sell specific products, and refer patients to additional services backed by the same PE firm.34,51,65

Utilization of a PE-backed MSO also inadvertently adds administrative costs and management fees that make the practice more bureaucratic and less profitable.66,67 In addition to the MSO fee itself, which directly cuts into a physician’s profits,48 there may be arrangements related to how the PE firm acquired a practice that further erode a physician’s earnings. For example, a PE firm usually finances the purchase of a practice through a leveraged buyout, which saddles the practice with a high debt burden.68 This burden has resulted in PE-backed hospitals such as Hahnemann University Hospital declaring bankruptcy and PE-backed specialty platform practices such as DermOne closing add-on practices.69,70

The administrative complexity of a PE-backed MSO often presents a challenge to practice integration. The most tangible aspects of this complexity relate to purchasable software and systems and written policies. For example, when practices merge, they likely have incompatible electronic health records or endoscopy software, use different claims management systems, or have different billing or scheduling policies. Behind these systems and policies lie individual practice cultures that are designed around local needs. Attempts to change such culture risk physician and staff turnover.66 In another example, siloing endoscopic tools that are purchased from one manufacturer is a common strategy for inventory management. Nuanced differences among these tools might be apparent only to the gastroenterologist, making bulk purchasing a contentious compromise that benefits the administrator but perhaps not the physician who is no longer the physician-owner.71 Furthermore, although integration of back-office functions yields synergies, PE firms could leverage integration across more dimensions to bring additional value to patients.72 For example, full integration that focuses on melding institutional cultures and clinical services in addition to back-office functions can improve patient outcomes.73,74 The merger between Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital highlights this importance of focusing on more than just back-office integration. Here, backoffice consolidation led to improved negotiations with insurance companies and increased reimbursement, but improved patient outcomes did not immediately follow—achieving the merger’s ultimate goals would require a rebranding and setting targets related to meaningful patient outcomes.71,75

Newer trends in gastroenterology practice management may include horizontal integration with multidisciplinary care models, such as Oshi Health for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, and vertical integration with insurers, such as through acquisition by United Healthcare. At the same time, the outlook for the gastroenterologist-led practice remains bright, given the rate and breadth of innovative ancillary services and new technologies, such as for weight loss, fatty liver disease, and motility disorders, that hold the promise of an exciting future.76

Conclusion

PE firms continue to drive significant consolidation of independent gastroenterology practices. The full consequences of this trend remain unclear. Nevertheless, early studies suggest patients will face increased costs. If health outcomes significantly improve with this added spending, then PE-backed gastroenterology practices provide positive value to their patients. However, if health outcomes remain stable or worsen, this supports the argument that PE-backed practices overutilize profitable services, providing low-value care. Although consolidation will likely continue owing to economies of scale, more research on health outcomes related to health care delivery system financial incentives needs to occur before understanding the full effects of increased PE-driven consolidation in gastroenterology.

References

- Fleishon HB, Vijayasarathi A, Pyatt R, Schoppe K, Rosenthal SA, Silva E III. White Paper: corporatization in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(10):1364–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Bye M, Howland J. Operational improvement: the key to value creation in private equity. J Appl Corp Finance. 2009;21(3):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cendrowski H, Petro LW, Martin JP, Wadecki AA. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Private Equity: History, Governance, and Operations. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell EM, Lelli GJ, Bhidya S, Casalino LP. The growth of private equity investment in health care: perspectives from ophthalmology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):1026–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramani A, Xun H, Comer CD, Lee BT, Lin SJ. What is the potential impact of private equity acquisitions regarding plastic surgery practices? Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum E, Batt R. Private equity buyouts in healthcare: Who wins, who loses? Institute for New Economic Thinking. Working Paper No. 118. https://www.cepr.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/WP_118-Appelbaum-and-Batt.pdf Published March 15, 2020. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Kaplan S. The effects of management buyouts on operating performance and value. J Financ Econ. 1989;24(2):217–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SN, Schoar A. Private equity performance: returns, persistence, and capital flows. J Finance. 2005;60(4):1791–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SN, Strömberg P. Leveraged buyouts and private equity. J Econ Perspect. 2009;23(1):121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Boucly Q, Sraer D, Thesmar D. Growth LBOs. J Financ Econ. 2011;102(2):432–453. [Google Scholar]

- Spaenjers C, Steiner E. Specialization and performance in private equity: evidence from the hotel industry. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3738265 Revised February 21, 2023. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Do private equity owned firms have better management practices? Am Econ Rev. 2015;105(5):442–446. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas L. Private equity firms are buying up your favorite food brands. Food & Environment Reporting Network’s AG Insider. https://thefern.org/ag_insider/ private-equity-firms-are-buying-up-your-favorite-food-brands/ Published June 18, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Zhu JM, Hua LM, Polsky D. Private equity acquisitions of physician medical groups across specialties, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(7):663–665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellad ZF. Practice management: the road taken and the road ahead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(6):1205–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisacreta E, Huetteman E. Betting on ‘Golden Age’ of colonoscopies, private equity invests in gastro docs. News release. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/ news/article/private-equity-gastroenterologist-colonoscopy/ Published May 27, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Gilreath M, Patel NC, Suh J, Brill JV. Gastroenterology physician practice management and private equity: thriving in uncertain times. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1084–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JI, Kaushal N. New models of gastroenterology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickerbocker K. What is private equity and how does it work? PitchBook blog. https://pitchbook.com/blog/what-is-private-equity Published December 20, 2021. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Gilreath M, Morris S, Brill JV. Physician practice management and private equity: market forces drive change. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(10):1924–1928.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent C. Update: private equity in ophthalmology. Review of Ophthalmology. https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/update-private-equity-inophthalmology Published May 10, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Pauly MV. Economics of multispecialty group practice. J Ambul Care Manage. 1996;19(3):26–33. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kletke PR, Emmons DW, Gillis KD. Current trends in physicians’ practice arrangements. From owners to employees. JAMA. 1996;276(7):555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paryani S, Scott W, Wells J et al. The “revolution” in outpatient care. J Ambul Care Manage. 1995;18(3):58–67. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebhaber A, Grossman JM. Physicians moving to mid-sized, single-specialty practices. Track Rep. 2007. pp. 1–5. 18. [PubMed]

- Kash B, Tan D. Physician group practice trends: a comprehensive review. J Hosp Med Manage. 2016;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- Evans JM, Baker GR, Berta W, Barnsley J. The evolution of integrated health care strategies. Adv Health Care Manag. 2013;15:125–161. doi: 10.1108/s1474-8231(2013)0000015011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs SL, Jellinek PS, Ray WL. The independent physician—going, going.... N Engl J Med. 2009;360(7):655–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0808076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ZD, Hogan J, Pollock JR, Moore ML, Mehta D. Gastroenterology practice consolidation between 2012 and 2020. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(8):3568–3575. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes N, Smith ZL, Spitzer RL, Keswani RN, Wani SB, Elmunzer BJ. North American Alliance for the Study of Digestive Manifestations of COVID-19. Changes in gastroenterology and endoscopy practices in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: results from a North American Survey. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(2):772–774.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte TN, Miedaner F, Sülz S. Physicians’ perspectives regarding private equity transactions in outpatient health care—a scoping review and qualitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15480. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192315480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino LP. Private equity, women’s health, and the corporate transformation of American medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1545–1546. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetter E, Snyder JA. Private equity investment and consolidation strategies in gastroenterology. https://focusbankers.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ FOCUS-White-Paper-Outlook-Gastroenterology-January-2020.pdf Published January 2020. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Konda S, Francis J, Motaparthi K, Grant-Kels JM. Group for Research of Corporatization and Private Equity in Dermatology. Future considerations for clinical dermatology in the setting of 21st century American policy reform: corporatization and the rise of private equity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):287–296.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KM, Demyan L, Weiss MJ. Private equity and its increasing role in US healthcare. Adv Surg. 2022;56(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billig JI, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Trends in funding and acquisition of surgical practices by private equity firms in the US from 2000 to 2020. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):1066–1068. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2018/03/07/1418000/0/en/ KKR-to-Acquire-Majority-Interest-in-Heartland-Dental.html KKR to acquire majority interest in Heartland Dental. News release. Globe Newswire. Published March 7, 2018. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- https://www.prnewswire. com/news-releases/heartland-dental-announces-strategic-transaction-with-american-dental-partners-incorporated-301291907.html Heartland Dental announces strategic transaction with American Dental Partners Incorporated. News release. PRNewswire. Published May 14, 2021. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, Mostaghimi A. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1013–1021. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SN, Groth S, Sternberg P., Jr The emergence of private equity in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):601–602. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EM, Cox JT, Begaj T, Armstrong GW, Khurana RN, Parikh R. Private equity in ophthalmology and optometry: analysis of acquisitions from 2012 through 2019 in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa A, Bruch JD. Prevalence and performance of private equity-affiliated fertility practices in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(1):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddapati V, Danford NC, Lopez CD, Levine WN, Lehman RA, Lenke LG. Recent trends in private equity acquisition of orthopaedic practices in the United States. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(8):e664–e672. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Demkowicz PC, Hsiang W et al. Urology practice acquisitions by private equity firms from 2011–2021. Urol Pract. 2022;9(1):17–24. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsh GM, Kapoor DA. Private equity and urology: an emerging model for independent practice. Urol Clin North Am. 2021;48(2):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyan K, Lam M, Milligan MG. Trends in private equity involvement in oncology practices in the United States. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;114(3):S100–S101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JM, Polsky D. Private equity and physician medical practices — navigating a changing ecosystem. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):981–983. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2032115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RP. Physician practice management companies: too good to be true? Fam Pract Manag. 1998;5(4):55–56. 45-46, 49-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resneck JS., Jr Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):13–14. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Y, Song Z, Polsky D, Bruch JD, Zhu JM. Association of private equity acquisition of physician practices with changes in health care spending and utilization. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(9):e222886. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondi S, Song Z. Potential implications of private equity investments in health care delivery. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1047–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Hellander I, Wolfe SM. Quality of care in investor-owned vs not-for-profit HMOs. JAMA. 1999;282(2):159–163. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, Secrest AM, Ferris LK. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):569–573. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch JD, Gondi S, Song Z. Changes in hospital income, use, and quality associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1428–1435. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relman AS. The new medical-industrial complex. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(17):963–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010233031703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinwald B, Neuhauser D. The role of the proprietary hospital. Law Contemp Probl. 1970;35(4):817. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Howell ST, Yannelis C, Gupta A. Does private equity investment in healthcare benefit patients? Evidence from nursing homes. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2021.

- Luh JY, Hansen ER, Liston S. Private equity and health care delivery. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers BW, Shrank WH, Navathe AS. Private equity and health care delivery: value-based payment as a guardrail? JAMA. 2021;326(10):907–908. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer R. Healthcare Services Report: PE Trends and Investment Strategies. PitchBook. 2022. https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/Q3_2022_ Healthcare_Services_Report.pdf#page=1 Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Newitt P. Private equity partners of 10 gastroenterology groups. Becker’s Healthcare. https://www.beckersasc.com/gastroenterology-and-endoscopy/private-equity-partners-of-10-gastroenterology-groups.html Updated June 6, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- https://www.prnewswire.com/ news-releases/gi-alliance-finalizes-physician-led-buyout-and-new-partnership-with-apollo-301625409.html GI Alliance Finalizes Physician-led Buyout and New Partnership with Apollo. New Release. PRNewswire. Published September 15, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Casalino LP, Saiani R, Bhidya S, Khullar D, O’Donnell E. Private equity acquisition of physician practices. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(2):114–115. doi: 10.7326/M18-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton R. One GI’s acquisition spree: 2 deals in 4 weeks. Becker’s Healthcare. https://www.beckersasc.com/gastroenterology-and-endoscopy/one-gis-acquisition-spree-2-deals-in-4-weeks.html Published December 6, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Konda S, Francis J. The evolution of private equity in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38(3):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt UE. The rise and fall of the physician practice management industry. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(1):42–55. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowes R. PPMs: going ... going.... Med Econ. 2001;78(5):67. 60, 63. 70 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S, Roxas R. Private equity and its effect on patients: a window into the future. 2022. pp. 1–12. Int J Health Econ Manag. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lexa FJ. Hahnemann-the fast death of an academic medical center and its implications for US radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(1 Pt A):82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun RT, Bond AM, Qian Y, Zhang M, Casalino LP. Private equity in dermatology: effect on price, utilization, and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(5):727–735. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH. Partners Healthcare Invasive Cardiology Team Collaborating to reduce costs in invasive cardiology: the Partners Healthcare experience. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1995;21(11):593–599. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmel P, van Steenis T, Meijboom B. Front-office/back-office configurations and operational performance in complex health services. Brain Inj. 2014;28(3):347–356. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.865271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovseiko PV, Melham K, Fowler J, Buchan AM. Organisational culture and post-merger integration in an academic health centre: a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0673-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Arnold S, Jones S et al. Quality and safety outcomes of a hospital merger following a full integration at a safety net hospital. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142382. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt L. Why many integrated delivery systems have not enhanced consumer value, and what’s next. NEJM Catal. 2020;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Shah ED, Rothstein RI. Crossing the chasm: tools to define the value of innovative endoscopic technologies to encourage adoption in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(5):1183–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]