Abstract

Stress response pathways are crucial for cells to adapt to physiological and pathologic conditions. Increased transcription and translation in response to stimuli place a strain on the cell, necessitating increased amino acid supply, protein production and folding, and disposal of misfolded proteins. Stress response pathways, such as the unfolded protein response (UPR) and the integrated stress response (ISR), allow cells to adapt to stress and restore homeostasis; however, their role and regulation in pathologic conditions, such as hepatic fibrogenesis, are unclear. Liver injury promotes fibrogenesis through activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which produce and secrete fibrogenic proteins to promote tissue repair. This process is exacerbated in chronic liver disease, leading to fibrosis and, if unchecked, cirrhosis. Fibrogenic HSCs exhibit activation of both the UPR and ISR, due in part to increased transcriptional and translational demands, and these stress responses play important roles in fibrogenesis. Targeting these pathways to limit fibrogenesis or promote HSC apoptosis is a potential antifibrotic strategy, but it is limited by our lack of mechanistic understanding of how the UPR and ISR regulate HSC activation and fibrogenesis. This article explores the role of the UPR and ISR in the progression of fibrogenesis, and highlights areas that require further investigation to better understand how the UPR and ISR can be targeted to limit hepatic fibrosis progression.

Cirrhosis is an increasingly prevalent condition that leads to end-stage liver disease and liver failure.1,2 Cirrhosis occurs in response to liver injury, stemming from metabolic disorders, obesity, alcohol use, drug use, or viral infection. Liver injury activates a wound healing response, termed fibrogenesis, which involves activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).3, 4, 5 HSC activation involves differentiation of quiescent HSCs into myofibroblasts that proliferate, migrate, and produce as well as secrete fibrogenic proteins in response to liver injury.3,5 Fibrogenesis is initially a transient response to liver injury, allowing the liver to repair and regenerate, followed by resorption of the fibrogenic matrix.5,6 Chronic liver injury leads to persistent HSC activation, accumulation of scar tissue, liver fibrosis, and in some cases development of cirrhosis, at which point fibrotic scarring is irreversible.5,7 Limiting or reversing fibrosis has long been a therapeutic goal, particularly because fibrosis regresses with removal of the injury.4 Unfortunately, no drugs have yet successfully targeted fibrogenesis or promoted fibrosis regression directly.4,7 This is because of several factors, key among them being an incomplete understanding of both fibrogenic mechanisms in HSCs and how HSCs crosstalk with other liver cells during chronic liver injury. Stress responses are signaling pathways that play roles as both drivers of fibrosis and potential targets to reverse fibrosis. HSCs experience numerous stressors, including increased protein folding and trafficking demands, reactive oxygen species, metabolic changes, and other stressors that activate signaling mechanisms aimed at restoring cellular homeostasis.3,8,9 These stress responses include the unfolded protein response (UPR), integrated stress response (ISR), and oxidative stress response. All three of these pathways are implicated in promoting HSC activation and fibrogenesis, but they can also initiate HSC apoptosis under conditions of prolonged stress.3,8,10 Because of this dichotomy, understanding how HSCs balance stress responses to maintain a fibrogenic phenotype is crucial to targeting these processes as an antifibrotic strategy. Because the role of the oxidative stress response during chronic liver injury has been recently reviewed in detail, this review instead focuses on the recent advances in the role of the UPR and ISR in HSC activation and fibrogenesis, potential strategies for targeting these stress responses in patients, and the exciting directions that studying stress responses in the UPR could take the field in the future.11,12

ER Stress and the UPR in Hepatic Fibrosis

ER Stress and the UPR

The UPR is one of the major stress response pathways in HSCs, and it is initiated in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. The ER is a major site of protein folding and processing. Proteins destined for secretion or membrane insertion are translated by ribosomes located on the rough ER and folded by chaperones within the ER lumen. ER stress occurs when the folding demands of the ER exceed its folding capacity. Heightened protein folding demands result from increased cotranslational translocation of nascent proteins into the ER lumen, abnormal rates of protein misfolding due to mutations or quality control failures, and altered calcium homeostasis in the ER lumen. Unfolded or misfolded proteins recruit chaperones to assist in folding, which disinhibits ER stress sensors and activates the UPR.13 The three canonical ER stress sensors are inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), activating transcription factor 6α (ATF6α), and protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). Under non-stressed conditions, these transmembrane sensors are held in an inactive state by the chaperone Ig-binding protein (BiP). Recruitment of BiP to assist in protein folding promotes activation of the ER stress sensors, which in turn initiate both independent and interdependent signaling cascades.13 The aim of these cascades is to relieve ER stress and restore protein homeostasis through limiting general protein translation, while promoting transcription/translation of stress-responsive genes, termed the adaptive UPR.14,15 The dual translational and transcriptional regulation is crucial for the adaptive UPR to resolve ER stress, restore proteostasis, and deactivate the UPR. If the adaptive UPR is unable to resolve ER stress, UPR signaling shifts to promote apoptosis. This is achieved through increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes such as CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (c/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP) and growth arrest and DNA damage inducible 34 (GADD34), inhibition of anti-apoptotic proteins, and activation of pro-apoptotic proteins.16, 17, 18, 19 The balance of adaptive and apoptotic signaling is crucial in activated HSCs, which exhibit increased transcription and translation to not only produce and secrete fibrotic proteins, but also migrate, proliferate, while limiting apoptosis.4,8

Balancing ER Stress Is Crucial for Fibrogenesis

Numerous mouse models have identified a critical role for stress responses in the development of fibrosis. Mice injected with the hepatotoxin carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) expressed increased levels of the UPR markers BiP and CHOP in HSCs expressing α-smooth muscle actin, a marker of HSC activation, whereas treatment with the chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid was sufficient to limit CCl4-mediated fibrogenesis.20,21 There is evidence for ER stress as both a consequence and a driver of HSC activation and fibrogenesis. Initial studies looking at the fibrogenic role of the UPR showed that chemical induction of the UPR using tunicamycin promoted HSC activation in vitro.22 Brefeldin A, which causes ER stress through disruption of post-ER trafficking, also induced HSC activation, and this was found to occur through an IRE1α-dependent mechanism.23 Balancing ER stress may have important consequences for fibrogenic HSCs. Low doses of tunicamycin promoted HSC activation in vitro, whereas at high concentrations tunicamycin promoted HSC apoptosis.24 Inducing ER stress to promote HSC apoptosis has also been explored as a potential therapeutic strategy, although mechanisms to specifically target HSCs for apoptosis remain difficult to achieve.25, 26, 27 Each of the canonical UPR pathways, their role in HSC activation and fibrogenesis, and how crosstalk between these pathways and noncanonical signaling may provide insight into both mechanisms of fibrogenesis and new directions for investigation is discussed below.

IRE1α Signaling in HSCs

Introduction to IRE1α Signaling

IRE1α is the most conserved ER stress sensor. BiP recruitment away from IRE1α during ER stress facilitates oligomerization of IRE1α. Oligomerization activates the IRE1α kinase domain, inducing trans-autophosphorylation and initiating two distinct signaling cascades, mediated by the IRE1α endonuclease domain or its kinase domain. The endonuclease activity of IRE1α degrades RNA through a process termed regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD). RIDD also specifically targets mRNA for cleavage, the most studied of which is X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1).28, 29, 30, 31 IRE1α excises a 26-bp fragment from XBP1 mRNA, facilitating the translation of the active transcription factor XBP1s. XBP1s promotes transcription of numerous stress-responsive genes aimed at expanding the ER, increasing chaperone expression, and targeting misfolded proteins for proteasomal degradation through ER-associated degradation.32,33 Canonical XBP1 targets in UPR signaling include ER chaperones [HSPA5/BiP, DnaJ/heat shock protein 40 homolog subfamily B member 9 (DNAJB9), DnaJ/heat shock protein 40 homolog subfamily C member 3 (DNAJC3), and protein disulfide isomerase 3 (PDI3)], ER-associated degradation machinery [ER degradation-enhancing mannosidase α-like 1 (EDEM1) and synoviolin], and secretory pathway components [transport and Golgi organization protein 1 (TANGO1/MIA3), SEC23B, and SEC24C/D].34,35 IRE1α signaling through its endonuclease domain is generally considered adaptive, helping the ER to fold and export proteins while also targeting misfolded proteins for degradation.

IRE1α further induces signaling cascades through its kinase domain. IRE1α phosphorylates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), which in turn phosphorylates other kinases, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and p38.22,36 ASK1 activation of JNK leads to activation of proapoptotic proteins [BCL2 associated X (BAX) and BH3-interacting mediator of cell death] and inhibition of anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) family members, although the consequences of IRE1α signaling through extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 are less clear.37,38

IRE1α Signaling in HSCs and Fibrogenesis

IRE1α activation during HSC activation and fibrogenesis has been observed in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1A). Mice receiving CCl4 displayed increased IRE1α phosphorylation, and BiP expression was observed in cells expressing α-smooth muscle actin.21,39 Either deletion of IRE1α or injection of the IRE1α inhibitor 4μ8C limited CCl4-induced fibrosis, supporting a profibrogenic role for the UPR.21,39 In vitro, IRE1α phosphorylation and XBP1 splicing increased in activated HSCs.21,40 Interestingly, IRE1α activation occurs as a direct result of increased collagen I expression, since IRE1α phosphorylation was lost in immortalized human HSCs (LX-2 cells) lacking procollagen I or SMAD2, the transcription factor that promotes procollagen I expression in HSCs downstream of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β).40 Inhibition of IRE1α using 4μ8C in vitro limited HSC activation and collagen production, which has been suggested to occur through inhibiting autophagy, limiting ER expansion, and reducing expression of chaparones.21,22,40 Recent work showed that IRE1α induced the procollagen I chaperone prolyl 4-hydroxylase (P4HB/PDIA1). P4HB encodes for a subunit of the prolyl-4-hydroxylase complex, which facilitates procollagen I folding through hydroxylation of proline residues.41,42 IRE1α deletion reduced P4HB expression in both whole liver in vivo and isolated HSCs. Subsequent studies in a non-HSC cell line (U2OS) that expresses high amounts of collagen revealed that IRE1α loss resulted in collagen retention in the ER and impaired secretion, both of which were rescued by P4HB overexpression.39 These data cumulatively support an important profibrotic role for IRE1α signaling in HSCs.

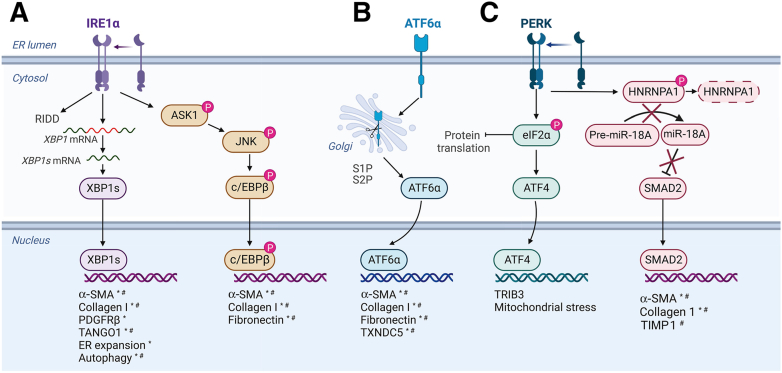

Figure 1.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) activates fibrotic genes during hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress leads to dissociation of the protein chaperone Ig-binding protein (BiP) from the three effector proteins of the UPR [activating transcription factor 6α (ATF6α), protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α)] and allows them to activate signaling mechanisms aimed at resolving ER stress. A: Dissociated IRE1α oligomerizes, autophosphorylates, and activates signaling cascades through X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1). The endonuclease activity of IRE1α cleaves mRNAs [in a process called regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD)], including the canonical splicing of XBP1 into the active transcription factor form. XBP1 increases expression of the fibrogenic genes α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen I, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFRβ), and transport and Golgi organization protein 1 (TANGO1), as well as the ER stress response mechanisms of ER expansion and autophagy. IRE1α also phosphorylates ASK1, which signals through a phosphorylation cascade involving c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the transcription factor CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (c/EBPβ). Like ATF6α, c/EBPβ increases expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin, increasing HSC activation and fibrogenesis. B: ATF6α dissociation from BiP reveals Golgi-localization signals to initiate its trafficking to the Golgi, where it is cleaved to release the cytosolic domain. ATF6α localizes to the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor. ATF6α increases expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and fibronectin in vitro and in vivo, directly up-regulating HSC activation and fibrogenesis. It also up-regulates thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 (TXNDC5), which activates JNK and STAT3 to promote fibrogenesis. C: PERK dimerization activates its kinase domain and leads to autophosphorylation. PERK phosphorylates and initiates signaling cascades through the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1). PERK phosphorylation of eIF2α inhibits general translation and promotes preferential translation of stress response genes, including the transcription factor ATF4, whose role in fibrogenesis is unclear. PERK also phosphorylates HNRNPA1, targeting it for degradation and preventing maturation of its downstream target miR-18A, promoting its degradation. miR-18A can target SMAD2, a major protein in fibrogenic transforming growth factor-β signaling, for degradation, so loss of miR-18A increases SMAD2 levels and associated fibrogenic signaling. ∗Shown in vitro. #Shown in vivo. Adapted from UPR Signaling (ATF6, PERK, IRE1) template at BioRender.com (Toronto, ON, Canada; 2023). TIMP1, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 1; TRIB3, Tribbles pseudokinase 3.

Several studies have shown a specific role for XBP1 in HSC activation and fibrogenesis. XBP1 facilitated ER expansion during HSC activation, as well as procollagen I expression and autophagic flux.21,22,40 In addition, XBP1 overexpression was sufficient to promote HSC activation, coinciding with up-regulation of fibrogenic genes and genes crucial for procollagen I folding and trafficking.24,43 Although this establishes XBP1 as a profibrotic transcription factor and a potential antifibrotic target, specific targeting of XBP1 is complicated by two major issues. First, XBP1 acts as a heterodimer, binding other transcription factors including c/EBPβ, c-Fos, and ATF6α.34,44 This crosstalk between the canonical arms of the UPR during HSC activation will be discussed in further detail below. Second, IRE1α endonuclease activity is not specific to XBP1. RIDD degrades mRNA to slow down the translation of nascent proteins into the ER, but has also been shown to degrade miRNAs. RIDD was previously implicated in fibrogenesis through targeting miR-150. miR-150 repressed HSC activation through targeting cMyb for degradation. On HSC activation, miR-150 was degraded by RIDD, which resulted in increased levels of the transcription factor cMyb and subsequent profibrotic transcription.21 Several other miRNAs are involved in fibrogenesis, and more are likely to be discovered, but whether RIDD is linked to these other miRNAs is not yet known.45, 46, 47

IRE1α kinase activity also plays a role in HSC activation and fibrogenesis. IRE1α overexpression promoted HSC activation through a mechanism involving IRE1α kinase activity, but not its endonuclease activity.40 IRE1α-dependent phosphorylation of ASK1 initiated a signaling cascade to activate JNK, which subsequently phosphorylated the transcription factor c/EBPβ.40 Inhibition or deletion of c/EBPβ limited HSC activation in vitro, and inhibition of c/EBPβ expression using the drug adefovir divipoxil limited fibrogenesis in vivo.40 This study highlighted a profibrotic role for JNK/ASK1 signaling downstream of IRE1α, which was originally thought to be primarily pro-apoptotic. An additional study identified IRE1α-mediated activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as a potentially profibrotic pathway through phosphorylation of SMAD2/3.23 These studies used brefeldin A to induce ER stress; thus, whether this pathway is pathologically relevant merits further investigation. In summary, these studies established that IRE1α signaling is induced during HSC activation due in part to increased procollagen I production, and acts through multiple downstream pathways to promote fibrogenesis.

ATF6α Signaling in HSCs

Introduction to ATF6α Signaling

ER stress leads to dissociation of BiP from ATF6α, revealing Golgi localization signals that facilitate ATF6α trafficking to the Golgi, where full-length ATF6α-p90 is cleaved to release the active transcription factor ATF6α-p50.48,49 ATF6α-p50 translocates to the nucleus, where it regulates transcription as a homodimer or heterodimer with c/EBPβ, XBP1, or ATF4. ATF6α induces transcription of stress-responsive genes such as PD1A1/P4HB, XBP1, HSPA5/BIP, EDEM1, and PDIA6.50, 51, 52, 53 ATF6α signaling primarily facilitates cellular adaptation to stress, evidenced by its transcriptional activation of chaperones and cooperation with XBP1.

ATF6α Signaling in HSC Activation and Fibrogenesis

Until recently, little was known regarding the role of ATF6α in HSCs (Figure 1B). ATF6α activation was observed in LX-2 cells following TGF-β treatment, and overexpression of ATF6α in LX-2 cells was sufficient to induce COL1A1 and FN1 transcription.54,55 Inhibition of ATF6α using ceapin-A7 blocked TGF-β induction of fibrogenic gene transcription in primary HSCs.54 In addition, conditional deletion of Atf6a from HSCs in vivo limited fibrogenesis in response to chronic CCl4 injection or bile duct ligation.54 The downstream mechanisms that mediate the profibrogenic role of ATF6α are less clear and merit further investigation to understand how ATF6α signaling could be targeted to limit fibrogenesis without deleterious off-target effects. To this end, the protein thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5 (TXNDC5) was recently identified as an important driver of liver fibrosis downstream of ATF6α.55 TXNDC5 expression increased in primary HSCs in a CCl4 model of fibrosis and in LX-2 cells treated with TGF-β, and this occurred through an ATF6α-dependent mechanism.55 TXNDC5 deletion limited HSC activation in vitro, and either global or HSC-specific deletion of TXNDC5 limited fibrosis in vivo.55 TXNDC5 is suggested to promote fibrogenesis by activating JNK and STAT3 downstream of oxidative stress.55 In addition to TXNDC5, potential profibrotic genes downstream of ATF6α are CEBPB and P4HB.40,52,53,56 CEBPB encodes c/EBPβ, which regulates fibrogenesis downstream of IRE1α.40 Because IRE1α and ATF6α can overlap in their transcriptional regulation, and both ATF6α and XBP1 can heterodimerize with c/EBPβ to regulate transcription, c/EBPβ could be either independently or coordinately regulated by IRE1α and ATF6α.34,56 P4HB encodes for a subunit of the prolyl-4-hydroxylase complex, which facilitates procollagen I folding through hydroxylation of proline residues.41,42 IRE1α also regulates P4HB expression, but the relative contributions of IRE1α and ATF6α in P4HB expression remain to be studied in depth.39

PERK Signaling in HSCs

Introduction to PERK Signaling

ER stress and BiP recruitment away from PERK allow PERK monomers to dimerize and activate PERK kinase activity. The primary substrate of PERK is the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), a component of the translation initiation complex. PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation slows down translation by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B. Disruption of the GTPase activity of eIF2 reduces the delivery of Met-tRNAiMet to ribosomes and effectively represses bulk translation initiation.57, 58, 59 By slowing down translation in this way, PERK signaling limits the formation of nascent unfolded proteins and allows the cell to recover from stress, while also promoting translation of stress-responsive mRNAs containing upstream open reading frames.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 Several mRNAs have been identified that are up-regulated in response to stress through this mechanism, with ATF4 as the canonical stress-induced downstream target of PERK. ATF4 is a transcription factor that promotes expression of several stress-responsive genes including CHOP/GADD153, a transcription factor canonically associated with apoptosis initiation.62, 63, 64 ATF4 regulates transcription as both a homodimer and a heterodimer, binding c/EBPβ, ATF3, c/EBPα, and other stress-associated transcription factors.65

PERK Signaling in HSC Activation and Fibrogenesis

PERK signaling in HSCs is less clear than that of the other two UPR pathways. PERK has been implicated in HSC activation and fibrosis through ATF4-dependent and ATF4-independent mechanisms (Figure 1C). PERK phosphorylation increased in livers of mice or rats receiving CCl4, and in primary rat HSCs activated ex vivo.66,67 PERK was reported to phosphorylate heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1), an miRNA processing enzyme.66 HNRNPA1 is required for maturation of miR18A, which induces degradation of SMAD2 RNA.66 PERK-mediated phosphorylation of HNRNPA1 targeted HNRNPA1 for degradation in both primary rat HSCs and LX-2 cells, and subsequently increased SMAD2 expression and profibrotic transcription.66 More important, this pathway did not involve ATF4. Recent work also suggested that ATF4 may not promote fibrogenesis, as ATF4 overexpression in LX-2 cells failed to promote HSC activation.54 Other studies implicating PERK in fibrosis found that PERK could be activated by stimulator of interferon genes (STING), leading to translational changes that promoted inflammation and cellular senescence, whereas PERK inhibition limited renal and pulmonary fibrosis in vivo.68 Together, these data suggest that PERK is involved in HSC activation, but this role may not require ATF4.

A recent study using rats suggested that ATF4 may play an important role in HSC activation and fibrosis. ATF4 protein and mRNA levels increased in livers of mice or rats receiving CCl4. PERK inhibition or shRNA-mediated knockdown of ATF4 disrupted platelet-derived growth factor-BB–induced activation of immortalized rat HSCs.69 ATF4-induced activation of rat HSCs was suggested to occur through ATF4 up-regulation of Tribbles homolog 3/Tribbles pseudokinase 3 (TRB3/TRIB3) and increased mitochondrial stress. Two factors that differentiate this study from the aforementioned studies, in which ATF4 was not found to facilitate fibrogenesis, were the use of platelet-derived growth factor-BB (as opposed to TGF-β or tunicamycin) and the use of HSC-T6 cells (as opposed to LX-2 cells).54,66,69 Further investigation of ATF4, whether downstream of PERK or other activators of the ISR, is needed to better understand the role of ATF4 in HSC activation and fibrogenesis.

Noncanonical UPR Signaling Pathways

Although most studies focus on the three canonical arms of the UPR, additional UPR sensors are also implicated in fibrogenesis. cAMP responsive element binding protein 3-like 1 (CREB3L1) and CREB3L2 are transmembrane proteins localized at the ER. Similar to ATF6α, CREB3L1 and CREB3L2 dimerize, traffic to the Golgi, and are cleaved in response to ER stress, releasing an active transcription factor.70,71 CREB3L2 up-regulates expression of coat protein complex II (COPII) vesicle proteins SEC23A and SEC24D, both of which are crucial for HSC activation.72 Interestingly, loss of either CREB3L1 or CREB3L2 did not impact procollagen I trafficking, suggesting that HSCs use noncanonical trafficking pathways to accommodate procollagen I, potentially through the lysosome as has been recently postulated.73 Recent single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments on HSCs isolated with patients also implicated that CREB3L1 both increases in HSCs during progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and regulates numerous fibrogenic genes.74

UPR Regulation of Autophagy and Its Role in Fibrogenesis

UPR and Autophagy

The UPR regulates numerous processes, and one that merits discussion with regard to HSCs and fibrosis is autophagy. Autophagy mediates the turnover of cellular components and organelles, with the dual goals of removing damaged proteins and organelles, as well as increasing availability of free amino acids.75 Autophagic mechanisms are separated into three main types: macro-autophagy, micro-autophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Macro-autophagy, referred throughout the review as autophagy, involves engulfment of proteins or organelles by a bilayer autophagosome followed by fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome, where lysosomal hydrolases degrade the contents of the autophagosome. The UPR regulates autophagy through inducing transcription and translation of autophagic machinery in response to ER stress.75, 76, 77, 78 Increased autophagic flux is believed to initially play a protective role aimed at relieving ER stress; however, under chronic conditions autophagy can promote apoptosis.75, 76, 77, 78 All three arms of the UPR are associated with autophagy, with PERK-ATF4-CHOP signaling playing the most established role. ATF4 induces transcription of several autophagy components including BECN1, autophagy-related gene 5 (ATG5), ATG10, and ATG5, whereas CHOP promotes transcription of ATG5.79,80 IRE1α regulates autophagy through both its RNase activity and its kinase activity. IRE1α activation of XBP1 promotes Beclin1/BECL1 transcription, as well as activation of the autophagy-associated transcription factor EB (TFEB). IRE1α signaling through ASK leads to phosphorylation of Bcl2 and subsequent disinhibition of beclin1.81 ATF6α also promotes autophagy directly through induction of BECL1 transcription, and indirectly through inducing XBP1 transcription.82,83

A less studied form of autophagy is macro-ERphagy, selective engulfment of the ER and its contents by autophagosomes. Autophagic membranes are recruited to the ER through receptors on the ER membrane [reticulophagy receptor 1 (RETREG1, alias family with sequence similarity 134B (FAM134B)), cell cycle progression 1 (CCPG1), atlastin 3 (ATL3), SEC62, testis-expressed 264 (TEX264), cyclin-dependent kinase regulatory subunit associated protein 3 (CDK5RAP3), and reticulon 3L (RTN3L)] and cytoplasmic proteins [p62 and calcium-binding and coiled-coil domain 1 (CALCOCO1) and 2 (CALCOCO2)].84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94 Macro-ERphagy is quickly becoming recognized as a crucial process in relieving ER stress through degradation of ER-associated degradation–resistant protein aggregates. Following resolution of ER stress, macro-ERphagy also helps remove excess ER membrane due to stress-induced ER expansion.84,85,93,94 Macro-ERphagy is regulated in part through the UPR. CCPG1 is predicted to be up-regulated downstream of PERK and/or XBP1, whereas RETREG1 is induced by c/EBPβ.91,94 A link between macro-ERphagy and fibrogenesis has been implicated by studies in extrahepatic systems. At the ER, RETREG1 interacts indirectly with procollagen I through the chaperone calnexin and facilitates procollagen I trafficking to the lysosome via the autophagosome.87 RETREG1 targeting of procollagen I to the lysosome is hypothesized to facilitate degradation of misfolded procollagen.95

UPR-Induced Autophagy and Fibrosis

Autophagy is considered protective in most liver cells; however, the relationship between autophagy, HSC activation, and fibrogenesis is complicated and not wholly understood. Several studies show that HSC activation is associated with increased autophagy in vivo and in vitro.96 Increased autophagic flux promotes HSC activation in part through lipid droplet degradation, whereas inhibition of autophagy or deletion of key autophagic genes limits HSC activation.97,98 Subsequent studies revealed a role for the UPR in regulating autophagy during HSC activation. Induction of ER stress through reactive oxygen species or compounds (tunicamycin) increased both autophagic flux and HSC activation, and HSC activation was blocked in the absence of key autophagic components (ATG5 or ATG7) or in the presence of autophagy inhibitor chloroquine or 3-methyladenine.22,24,97 The UPR was also revealed to be a major regulator of autophagy during HSC activation, with IRE1α-XBP1 signaling promoting autophagy downstream of ER stress in HSCs. Inhibition of IRE1α limited autophagy and HSC activation, whereas XBP1 overexpression induced both autophagy and fibrogenic pathways.22,24 HSC activation through XBP1 overexpression was blocked by knockdown of ATG7, further linking the profibrotic role of the UPR to autophagy. No studies linking macro-ERphagy and HSC activation have been reported, but the role of macro-ERphagy in degrading misfolded procollagen suggests that ERphagy may be important in maintaining homeostasis in activated HSCs through removal of misfolded collagen.

Promising Directions in Targeting the UPR and ER Stress in Fibrogenesis

We are beginning to understand how ER stress and UPR signaling balance to regulate fibrogenesis. Low doses of tunicamycin activate HSCs, but high doses of tunicamycin promote HSC apoptosis and limit fibrogenesis.24,25,27 To better understand how the UPR facilitates fibrogenesis, as well as how to target the UPR to limit fibrogenesis or promote HSC apoptosis, additional in-depth analyses are required, although these have been hampered by a lack of reliable antibodies for immunoprecipitation and other antibody-based methods. Recent studies are addressing this using other methods. A recent study mapped the genome for putative UPR-induced genes by searching for sequences that match ER stress response elements, consensus sequences where XBP1 and ATF6α preferentially bind.99 This study identified hundreds of genes previously not associated with the UPR that contain upstream ER stress response elements, notably several known fibrogenic genes including multiple collagen isoforms, serpin peptidase inhibitor E1, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 2, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, and the receptor tyrosine kinase MET/hepatocyte growth factor receptor. Investigating how these putative UPR-responsive genes influence fibrogenesis may provide fundamental insight into the mechanisms of fibrogenesis and advance the development of novel strategies to target fibrosis in patients.

Crosstalk between the UPR pathways is another area not well understood in the context of HSCs and fibrosis. UPR crosstalk may provide crucial and unique clues into fibrogenesis. Our group recently found that ATF6α deletion from HSCs protected mice from fibrosis, whereas dual HSC-specific loss of ATF6α and IRE1α exacerbated fibrosis.54 Known crosstalk occurs between IRE1α and ATF6α pathways. IRE1α is important for ATF6α activation, and both IRE1α and ATF6α regulate XBP1 through inducing its expression (ATF6α) or activity (IRE1α).32,51,83 In addition, both pathways regulate profibrotic transcription factors, including c/EBPβ, with ATF6α promoting c/EBPβ expression, and IRE1α promoting c/EBPβ phosphorylation through the ASK1-JNK pathway.34,83 In addition, ATF6α and PERK signaling are integrated, with PERK signaling inducing ATF6α expression and activation, whereas both PERK and ATF6α regulate proapoptotic factors, such as GADD45A and regulator of calcineurin (RCAN1).100,101 Studies have implicated GADD45A and RCAN1 both initiating the switch from cell adaptation to apoptosis, as well as protecting mice from developing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and CCl4-induced fibrosis, respectively; however, whether these processes can be targeted is unclear.102, 103, 104

In summary, each arm of the UPR regulates HSC activation and fibrogenesis in a unique way, likely through integrated mechanisms that are not yet understood. Targeting molecules downstream of multiple UPR pathways, which regulate HSC survival (eg, c/EBPβ and XBP1), could provide a more effective approach than inhibiting the individual pathways. Another caveat that must be considered is the importance of the UPR to the pathophysiology of hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, cholangiocytes, endothelial cells, and portal fibroblasts. Identification of a pathway crucial for HSC survival and/or fibrogenesis could allow for more direct targeting of HSCs in vivo. Further investigation into UPR-dependent transcriptional and translational regulation during HSC activation will be crucial to continue expanding our understanding of the fibrogenic role of the UPR.

The Integrated Stress Response

The ISR and Translational Control in Hepatic Fibrosis

The ISR is an adaptive mechanism that encompasses multiple stress-responsive pathways that converge to regulate translation.15 The term integrated refers to the convergence of multiple stress-induced signaling pathways on a single point through which translation initiation is controlled. The ISR is initiated through activation of one of several kinases that phosphorylate eIF2α, the convergence point of the ISR. These kinases are general control nonderepressible 2 kinase (GCN2/EIF2AK4; activated by amino acid deprivation and UV irradiation among others), protein kinase R (PKR/EIF2AK2; activated by viral infection), heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI/EIF2AK1; activated by heme and iron depletion in erythroid cells and by mitochondrial stress), and PERK (EIF2AK3; activated by ER stress).59,105, 106, 107, 108, 109 Phosphorylation of eIF2α by these kinases reduces bulk translation initiation while allowing preferential translation of selective genes such as ATF4, which are required for restoring protein homeostasis (Figure 2A).110 Although little is known regarding the ISR in HSC activation and fibrogenesis, several lines of evidence lead us to predict that ISR regulation of translation is involved. First, PERK signaling is induced in activated HSCs.66,67 Second, enhanced translation of fibrogenic proteins most likely activates GCN2 through increased levels of uncharged tRNAs in response to heavy consumption of free amino acids.15 Third, protein and mRNA levels of ATF4 are up-regulated in response to CCl4 injection in vivo, but this may not be dependent on PERK signaling.66, 67 Despite these observations, it is unknown how the ISR regulates fibrogenesis. Taking into account our above discussion of PERK, this section will discuss the potential roles of ISR kinases GCN2, PKR, and HRI in HSC activation and fibrogenesis in addition to potential therapeutic approaches to limit hepatic fibrogenesis (Figure 2B).

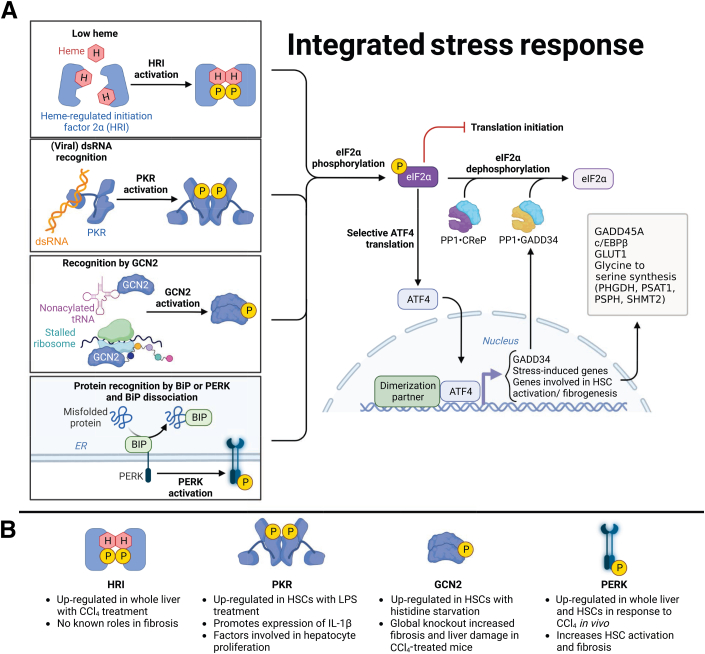

Figure 2.

The potential link between fibrogenesis and integrated stress response (ISR). A: The ISR is initiated by several different stimuli, but regardless of the initiating kinase [heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI), protein kinase R (PKR), general control nonderepressible 2 kinase (GCN2), or protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase (PERK)], ISR signaling begins with phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α; P-eIF2α). P-eIF2α limits bulk translation initiation, concomitant with preferential translation of stress response genes, including the transcription factor activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). ATF4 induces the expression of a diverse set of genes that play critical roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and responding to stress, including chaperones, oxidation-reduction enzymes, antiviral proteins, amino acid transporters, amino acid biosynthesis enzymes, tRNA synthetase, cytokines, and autophagy genes. ATF4 also up-regulates growth arrest and DNA damage inducible 34 (GADD34), a phosphatase that works in conjunction with another phosphatase, constitutive repressor of eIF2α phosphorylation (CReP), to dephosphorylate eIF2α and restore translation. Other ATF4-regulated genes include glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) and genes involved in glycine to serine synthesis [phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), phosphoserinea aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH), and serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2)]. B: ISR kinases have been shown to have different impacts on fibrogenesis in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). PERK was up-regulated in the whole liver as well as in HSCs following carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) treatment and promoted SMAD2 signaling through the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1–miR-18A pathway. HRI was also up-regulated in the whole liver following CCl4 treatment, but the impact of HRI signaling in fibrogenesis remains unknown. Histidine starvation induced up-regulation of GCN2 in HSCs, and GCN2 signaling was found to have antifibrotic effects and protect the liver from damage. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure induced up-regulation of PKR in HSCs, which promoted inflammation and hepatocyte proliferation. Adapted from Integrated Stress Response template at BioRender.com (Toronto, ON, Canada; 2023). BiP, Ig-binding protein; c/EBPβ, CCAAT enhancer-binding protein; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA.

GCN2 and Hepatic Fibrosis

GCN2 kinase is a serine/threonine kinase that is an important sensor of amino acid availability in eukaryotic cells, and it is conserved across different organisms including yeast, mammals, and plants. It regulates translation initiation in response to various stress conditions, such as amino acid starvation, viral infection, and UV radiation.59 One of the primary functions of GCN2 is to regulate the synthesis of proteins by phosphorylating eIF2α to both inhibit bulk translation initiation and conserve cellular resources during stress conditions. In addition, GCN2 positively regulates the expression of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis, transport, and metabolism, all of which are necessary for cell survival under stress conditions.59 GCN2 activation is triggered by amino acid depletion through mechanisms that involve GCN2 binding to uncharged tRNAs, which accumulate during the deprivation of their corresponding amino acids.105,111 GCN2 can also be activated during specific stresses because of the stalling and collisions of elongating ribosomes, and this activation is believed to occur via a signaling pathway involving the MAPK ZAK.112, 113, 114, 115

GCN2 phosphorylation was observed in primary and immortalized HSCs following histidine deprivation, and this phosphorylation was associated with reduced reactive oxygen species and HSC activation.116,117 In vivo studies showed Gcn2−/− mice displayed increased fibrosis and liver damage in response to CCl4 injection compared with controls.116 Although these data implicate GCN2 activation as potentially protective, they are limited by several factors, including lack of data using pathophysiological activators of HSCs (eg, TGF-β) and no conditional deletion of GCN2 from HSCs in vivo. Extrahepatic studies have also implicated that GCN2 is antifibrotic. GCN2 was expressed in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the lung, and GCN2 levels and eIF2α phosphorylation decreased in patients with pulmonary fibrosis.118 In rats, GCN2 was similarly observed in smooth muscle cells, and loss of GCN2 function through expression of a mutant GCN2 exacerbated pulmonary fibrosis.118

PKR and Hepatic Fibrosis

PKR phosphorylation is canonically induced in response to viral infection, stemming from recognition of double-stranded RNA, although additional studies have implicated that PKR is activated by other stresses, such as changes in calcium levels, oxidative stress, inflammation, and lipotoxic stress.109,119 With regard to fibrosis, HSCs treated with lipopolysaccharide displayed PKR activation, which promoted expression of proinflammatory IL-1β.120 Furthermore, conditioned media from lipopolysaccharide-treated HSCs promoted proliferation of HepG2 cells, although this effect was lost when HepG2 cells were treated with conditioned media from HSCs treated with lipopolysaccharide in combination with either PKR inhibitor C19 or siRNA-mediated PKR knockdown.120 Finally, studies in the kidney showed that increased PKR positively correlated with renal damage and fibrosis, but no clear correlation between PKR and hepatic fibrosis has been found.121

HRI and Hepatic Fibrosis

HRI is activated in response to heme/iron deficiency and oxidative stress, and it has been studied extensively in erythroid cells.107,122 With regard to fibrogenesis, one study showed that liver HRI expression increased in response to a single injection of CCl4, and this was correlated with increased fibrosis.123 In the absence of further studies, it is unclear whether HRI plays a pathologic role in liver fibrosis. In addition, studying HRI in fibrogenesis is hampered by a lack of commercially available inhibitors or activators of HRI.

ATF4

Until recently, studies on the role of PERK in liver fibrosis did not directly implicate ATF4, and this important transcription factor merits additional discussion in regard to both the UPR and the ISR. It is likely that ATF4 induction of ATF4 transcriptional targets includes CHOP, GADD45A, GADD45B, and other genes that regulate cell death and cell cycle arrest.63,124,125 Regulating the balance between prosurvival and pro-apoptotic pathways during HSC activation is important for fibrogenesis, and ATF4 could play a key role in maintaining this balance. Furthermore, GADD45A has been suggested to limit HSC activation and protect against fibrosis.102 Moreover, a recent study identified a crucial role for ATF4 in procollagen synthesis in myofibroblasts. Lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis expressed ATF4, and TGF-β increased ATF4 in lung fibroblasts in vitro in a mammalian target of rapamycin–dependent but rapamycin-independent manner. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) up-regulation of ATF4 in this model occurred independently of PERK, although the other pathways of the ISR were not investigated. The profibrotic consequences downstream of ATF4 were elucidated as increased expression of genes involved in serine-to-glycine biosynthesis.126 Every third amino acid in procollagen is a glycine, allowing for the canonical triple helical structure; thus, the group postulated that ATF4 induction of serine-to-glycine synthesis pathways was crucial for fibrogenesis in the lung.126 On the basis of these studies, ATF4 may have less of a direct effect on HSC activation (eg, up-regulation of procollagen and α-smooth muscle actin) and instead may facilitate the assembly and trafficking of matrix proteins.

ISR and Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a highly regulated cellular process that plays a critical role in development, tissue homeostasis, and immune system function.127 One of the essential roles of the ISR is to initiate apoptosis under conditions of prolonged or severe stress. The ISR promotes apoptosis through ATF4, which induces the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, such as CHOP/GADD153, TRB3, and BH3-only family members p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate–induced protein (NOXA), and Bcl-2–interacting mediator of cell death (BIM).16,17,62, 63, 64,128 These genes are involved in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and are responsible for the activation of caspases, degradation of cellular components, and eventual cell death.129,130

The role of CHOP in apoptosis is particularly noteworthy. ATF4-CHOP signaling plays a role in regulating apoptosis through both the mitochondrial-dependent131,132 and death receptor–dependent pathways.133, 134, 135 CHOP controls the expression of genes encoding anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic proteins including TRB3 and BCL2 family members. By down-regulating the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL2 and BCL-XL, and up-regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins, like BIM and TRB3, CHOP can increase BCL2 antagonist/killer 1 (BAK1) and BAX expression and release apoptotic factors, including cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor.18,136 CHOP also up-regulates the expression of death receptors, such as death receptor (DR)4 and DR5, to promote apoptosis. Overall, the extent of CHOP-induced apoptosis depends on different cell types and stimuli.133,134

Inducing apoptosis in HSCs through the ISR can serve as a potential antifibrotic therapeutic approach. This has been studied primarily in the context of cancers, where activation of the ISR by ONC201 triggers ATF4 activation and apoptosis in solid tumors.137 ONC201 induces ISR and apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines, glioblastoma, and diffuse midline gliomas, with the knockdown of ATF4 blocking the effect of ONC201.138 Tazemetostat, a drug used for treating epithelioid sarcoma, can enhance ISR induction and increase apoptosis, while combining ONC201 with tazemetostat or vorinostat, a drug used to treat cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, effectively promotes apoptosis.139

Additional Evidence and Insight into the Role of the ISR in Liver Fibrosis

Downstream effectors and targets of translational control provide further evidence that preferential translation is crucial for hepatic fibrogenesis. Microarray analysis comparing quiescent activated primary mouse HSCs revealed up-regulation of translational regulators in activated HSCs, including sterile α motif domain-containing 4A (SAMD4A), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2 (IGF2BP2), CUG-binding protein Elav-like family member 1 (CLEF1), cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein 1 (CPEB1), La ribonucleoprotein 1 (LARP1), and basic leucine zipper and W2 domains 1 (BZW1).140 CLEF1 and IGF2BP2 are RNA-binding proteins implicated in HSC activation and fibrogenesis, alongside zinc finger protein 36 (an autophagy regulator) and embryonic lethal, abnormal vision–like 1 (ELAV1).141, 142, 143, 144 Although these translation regulators are up-regulated in activated HSCs, few follow-up studies have investigated their contribution to fibrosis.140 Canonical downstream targets of the ISR are also implicated in fibrogenesis such as ATF3, XBP1, c/EBPβ, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and catalase 1 (CAT).21,22,24,40,43,145, 146, 147, 148 These proteins are preferentially translated in response to the ISR and may link ISR activation to fibrogenesis. Extrahepatic organ fibrosis also implicates the ISR in fibrogenesis. Studies in cardiac myofibroblasts showed translational regulation of RNA-binding proteins in activated myofibroblasts, including K homology-type splicing regulatory protein (KHSRP), which limits liver fibrosis.149,150 One of these studies also revealed that TGF-β regulated translation of several proteins with established roles in hepatic fibrosis, including TANGO1, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BNDF), and hairy and enhancer of split 1 (HES1).149

Conclusions

Both the UPR and ISR play critical roles in cell and organ physiology; thus, it makes sense that they play important roles in fibrogenesis. On the basis of the studies presented here, the adaptive UPR is primarily profibrotic, by up-regulating fibrogenic genes and increasing expression of genes involved in protein folding and trafficking. A caveat to these findings is that we do not yet understand how the changes in translational regulation by PERK and the other ISR-associated eIF2α kinases impact fibrogenesis. eIF2α phosphorylation inhibits general protein translation, but this could be balanced out by either up-regulation of other translational regulators or increased fibrogenic transcription by stress-induced transcription factors. The use of innovative murine models and development of both cell-specific delivery systems and better inhibitors of stress response components will be crucial to investigating and targeting these processes to treat hepatic fibrogenesis.

Footnotes

Stress Responses and Cellular Crosstalk in the Pathogenesis of Liver Disease Theme Issue

Supported in part by NIH grant DKR03129326 (J.L.M.), Indiana University School of Medicine Biomedical Research Grant (J.L.M.), and Showalter Trust grant (J.L.M.).

Z.H. and J.M. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

This article is part of a review series focused on the role of cellular stress in driving molecular crosstalk between hepatic cells that may contribute to the development, progression, or pathogenesis of liver diseases.

References

- 1.Scaglione S., Kliethermes S., Cao G., Shoham D., Durazo R., Luke A., Volk M.L. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:690–696. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asrani S.K., Devarbhavi H., Eaton J., Kamath P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsuchida T., Friedman S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezhilarasan D., Sokal E., Najimi M. Hepatic fibrosis: it is time to go with hepatic stellate cell-specific therapeutic targets. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berumen J., Baglieri J., Kisseleva T., Mekeel K. Liver fibrosis: pathophysiology and clinical implications. WIREs Mech Dis. 2021;13 doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferdek P.E., Krzysztofik D., Stopa K.B., Kusiak A.A., Paw M., Wnuk D., Jakubowska M.A. When healing turns into killing - the pathophysiology of pancreatic and hepatic fibrosis. J Physiol. 2022;600:2579–2612. doi: 10.1113/JP281135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman S.L., Pinzani M. Hepatic fibrosis 2022: unmet needs and a blueprint for the future. Hepatology. 2022;75:473–488. doi: 10.1002/hep.32285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamm D.R., McCommis K.S. Hepatic stellate cells in physiology and pathology. J Physiol. 2022;600:1825–1837. doi: 10.1113/JP281061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewidar B., Meyer C., Dooley S., Meindl-Beinker A.N. TGF-beta in hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis-updated 2019. Cells. 2019;8:1419. doi: 10.3390/cells8111419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiers J.L., Malhi H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic liver diseases and hepatic fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:235–248. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1681032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos-Tovar E., Muriel P. Molecular mechanisms that link oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:1279. doi: 10.3390/antiox9121279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luangmonkong T., Suriguga S., Mutsaers H.A.M., Groothuis G.M.M., Olinga P., Boersema M. Targeting oxidative stress for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;175:71–102. doi: 10.1007/112_2018_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Hendershot L.M., Harding H.P., Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutkowski D.T., Kaufman R.J. A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wek R.C., Anthony T.G., Staschke K.A. Surviving and adapting to stress: translational control and the integrated stress response. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2023;39:351–373. doi: 10.1089/ars.2022.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puthalakath H., O'Reilly L.A., Gunn P., Lee L., Kelly P.N., Huntington N.D., Hughes P.D., Michalak E.M., McKimm-Breschkin J., Motoyama N., Gotoh T., Akira S., Bouillet P., Strasser A. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galehdar Z., Swan P., Fuerth B., Callaghan S.M., Park D.S., Cregan S.P. Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16938–16948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iurlaro R., Munoz-Pinedo C. Cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J. 2016;283:2640–2652. doi: 10.1111/febs.13598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciniak S.J., Yun C.Y., Oyadomari S., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Jungreis R., Nagata K., Harding H.P., Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J.Q., Chen X., Zhang C., Tao L., Zhang Z.H., Liu X.Q., Xu Y.B., Wang H., Li J., Xu D.X. Phenylbutyric acid protects against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrogenesis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;266:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heindryckx F., Binet F., Ponticos M., Rombouts K., Lau J., Kreuger J., Gerwins P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrosis through IRE1alpha-mediated degradation of miR-150 and XBP-1 splicing. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:729–744. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez-Gea V., Hilscher M., Rozenfeld R., Lim M.P., Nieto N., Werner S., Devi L.A., Friedman S.L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces fibrogenic activity in hepatic stellate cells through autophagy. J Hepatol. 2013;59:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Galarreta M.R., Navarro A., Ansorena E., Garzon A.G., Modol T., Lopez-Zabalza M.J., Martinez-Irujo J.J., Iraburu M.J. Unfolded protein response induced by brefeldin A increases collagen type I levels in hepatic stellate cells through an IRE1alpha, p38 MAPK and Smad-dependent pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:2115–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim R.S., Hasegawa D., Goossens N., Tsuchida T., Athwal V., Sun X., Robinson C.L., Bhattacharya D., Chou H.I., Zhang D.Y., Fuchs B.C., Lee Y., Hoshida Y., Friedman S.L. The XBP1 arm of the unfolded protein response induces fibrogenic activity in hepatic stellate cells through autophagy. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep39342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Minicis S., Candelaresi C., Agostinelli L., Taffetani S., Saccomanno S., Rychlicki C., Trozzi L., Marzioni M., Benedetti A., Svegliati-Baroni G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and contributes to fibrosis resolution. Liver Int. 2012;32:1574–1584. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y., Li X., Wang Y., Wang H., Huang C., Li J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced hepatic stellate cell apoptosis through calcium-mediated JNK/P38 MAPK and calpain/caspase-12 pathways. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;394:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H., Dai L., Wang M., Feng F., Xiao Y. Tunicamycin induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis through calpain-2/Ca(2 +)-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.684857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han D., Lerner A.G., Vande Walle L., Upton J.P., Xu W., Hagen A., Backes B.J., Oakes S.A., Papa F.R. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollien J., Lin J.H., Li H., Stevens N., Walter P., Weissman J.S. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:323–331. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollien J., Weissman J.S. Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2006;313:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tirasophon W., Lee K., Callaghan B., Welihinda A., Kaufman R.J. The endoribonuclease activity of mammalian IRE1 autoregulates its mRNA and is required for the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2725–2736. doi: 10.1101/gad.839400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calfon M., Zeng H., Urano F., Till J.H., Hubbard S.R., Harding H.P., Clark S.G., Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uemura A., Oku M., Mori K., Yoshida H. Unconventional splicing of XBP1 mRNA occurs in the cytoplasm during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2877–2886. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto K., Sato T., Matsui T., Sato M., Okada T., Yoshida H., Harada A., Mori K. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6alpha and XBP1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S.M., Kang T.I., So J.S. Roles of XBP1s in transcriptional regulation of target genes. Biomedicines. 2021;9:791. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urano F., Wang X., Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Chung P., Harding H.P., Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hetz C., Bernasconi P., Fisher J., Lee A.H., Bassik M.C., Antonsson B., Brandt G.S., Iwakoshi N.N., Schinzel A., Glimcher L.H., Korsmeyer S.J. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK modulate the unfolded protein response by a direct interaction with IRE1alpha. Science. 2006;312:572–576. doi: 10.1126/science.1123480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto K., Ichijo H., Korsmeyer S.J. BCL-2 is phosphorylated and inactivated by an ASK1/Jun N-terminal protein kinase pathway normally activated at G(2)/M. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8469–8478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hazari Y., Urra H., Lopez V.A.G., Diaz J., Tamburini G., Milani M., Pihan P., Durand S., Aprahamia F., Baxter R., Huang M., Dong X.C., Vihinen H., Gonzalez A.B., Godoy P., Criollo A., Ratziu V., Foufelle F., Hengstler J.G., Jokitalo E., Maitre B.B., Maiers J.L., Plate L., Kroemer G., Hetz C. The endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor IRE1 regulates collagen secretion through the enforcement of the proteostasis factor P4HB/PDIA1 contributing to liver damage and fibrosis. bioRxiv. 2023 doi: 10.1101/2023.05.02.538835. [Preprint] doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Z., Li C., Kang N., Malhi H., Shah V.H., Maiers J.L. Transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) cross-talk with the unfolded protein response is critical for hepatic stellate cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:3137–3151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myllyharju J. Prolyl 4-hydroxylases, key enzymes in the synthesis of collagens and regulation of the response to hypoxia, and their roles as treatment targets. Ann Med. 2008;40:402–417. doi: 10.1080/07853890801986594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pihlajaniemi T., Myllyla R., Kivirikko K.I. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase and its role in collagen synthesis. J Hepatol. 1991;13(Suppl 3):S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90002-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maiers J.L., Kostallari E., Mushref M., deAssuncao T.M., Li H., Jalan-Sakrikar N., Huebert R.C., Cao S., Malhi H., Shah V.H. The unfolded protein response mediates fibrogenesis and collagen I secretion through regulating TANGO1 in mice. Hepatology. 2017;65:983–998. doi: 10.1002/hep.28921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ono S.J., Liou H.C., Davidon R., Strominger J.L., Glimcher L.H. Human X-box-binding protein 1 is required for the transcription of a subset of human class II major histocompatibility genes and forms a heterodimer with c-fos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4309–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sekiya Y., Ogawa T., Yoshizato K., Ikeda K., Kawada N. Suppression of hepatic stellate cell activation by microRNA-29b. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwiecinski M., Noetel A., Elfimova N., Trebicka J., Schievenbusch S., Strack I., Molnar L., von Brandenstein M., Tox U., Nischt R., Coutelle O., Dienes H.P., Odenthal M. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) inhibits collagen I and IV synthesis in hepatic stellate cells by miRNA-29 induction. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rashid H.O., Kim H.K., Junjappa R., Kim H.R., Chae H.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the regulation of liver diseases: involvement of regulated IRE1alpha and beta-dependent decay and miRNA. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:981–991. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen J., Chen X., Hendershot L., Prywes R. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev Cell. 2002;3:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hillary R.F., FitzGerald U. A lifetime of stress: ATF6 in development and homeostasis. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25:48. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., Shen J., Arenzana N., Tirasophon W., Kaufman R.J., Prywes R. Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27013–27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belmont P.J., Tadimalla A., Chen W.J., Martindale J.J., Thuerauf D.J., Marcinko M., Gude N., Sussman M.A., Glembotski C.C. Coordination of growth and endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling by regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1), a novel ATF6-inducible gene. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14012–14021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709776200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bommiasamy H., Back S.H., Fagone P., Lee K., Meshinchi S., Vink E., Sriburi R., Frank M., Jackowski S., Kaufman R.J., Brewer J.W. ATF6alpha induces XBP1-independent expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1626–1636. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xue F., Liu J., Buchl S.C., Sun L., Shah V.H., Malhi H., Maiers J.L. Coordinated signaling of activating transcription factor 6alpha and inositol requiring enzyme 1alpha regulates hepatic stellate cell-mediated fibrogenesis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;320:G864–G879. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00453.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hung C.T., Su T.H., Chen Y.T., Wu Y.F., Chen Y.T., Lin S.J., Lin S.L., Yang K.C. Targeting ER protein TXNDC5 in hepatic stellate cell mitigates liver fibrosis by repressing non-canonical TGFbeta signalling. Gut. 2022;71:1876–1891. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tam A.B., Roberts L.S., Chandra V., Rivera I.G., Nomura D.K., Forbes D.J., Niwa M. The UPR activator ATF6 responds to proteotoxic and lipotoxic stress by distinct mechanisms. Dev Cell. 2018;46:327–343. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harding H.P., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Zeng H., Wek R., Schapira M., Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Bertolotti A., Zeng H., Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wek R.C. Role of eIF2alpha kinases in translational control and adaptation to cellular stress. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a032870. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu P.D., Harding H.P., Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vattem K.M., Wek R.C. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fawcett T.W., Martindale J.L., Guyton K.Z., Hai T., Holbrook N.J. Complexes containing activating transcription factor (ATF)/cAMP-responsive-element-binding protein (CREB) interact with the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP)-ATF composite site to regulate Gadd153 expression during the stress response. Biochem J. 1999;339(Pt 1):135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X.Z., Lawson B., Brewer J.W., Zinszner H., Sanjay A., Mi L.J., Boorstein R., Kreibich G., Hendershot L.M., Ron D. Signals from the stressed endoplasmic reticulum induce C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4273–4280. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zinszner H., Kuroda M., Wang X., Batchvarova N., Lightfoot R.T., Remotti H., Stevens J.L., Ron D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reinke A.W., Baek J., Ashenberg O., Keating A.E. Networks of bZIP protein-protein interactions diversified over a billion years of evolution. Science. 2013;340:730–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1233465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koo J.H., Lee H.J., Kim W., Kim S.G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatic stellate cells promotes liver fibrosis via PERK-mediated degradation of HNRNPA1 and up-regulation of SMAD2. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:181–193. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luo X.H., Han B., Chen Q., Guo X.T., Xie R.J., Yang T., Yang Q. Expression of PERK-eIF2alpha-ATF4 pathway signaling protein in the progression of hepatic fibrosis in rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:3542–3550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang D., Liu Y., Zhu Y., Zhang Q., Guan H., Liu S., Chen S., Mei C., Chen C., Liao Z., Xi Y., Ouyang S., Feng X.H., Liang T., Shen L., Xu P. A non-canonical cGAS-STING-PERK pathway facilitates the translational program critical for senescence and organ fibrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:766–782. doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-00894-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye M.P., Lu W.L., Rao Q.F., Li M.J., Hong H.Q., Yang X.Y., Liu H., Kong J.L., Guan R.X., Huang Y., Hu Q.H., Wu F.R. Mitochondrial stress induces hepatic stellate cell activation in response to the ATF4/TRIB3 pathway stimulation. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:668–681. doi: 10.1007/s00535-023-01996-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kondo S., Saito A., Hino S., Murakami T., Ogata M., Kanemoto S., Nara S., Yamashita A., Yoshinaga K., Hara H., Imaizumi K. BBF2H7, a novel transmembrane bZIP transcription factor, is a new type of endoplasmic reticulum stress transducer. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1716–1729. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01552-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murakami T., Kondo S., Ogata M., Kanemoto S., Saito A., Wanaka A., Imaizumi K. Cleavage of the membrane-bound transcription factor OASIS in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1090–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tomoishi S., Fukushima S., Shinohara K., Katada T., Saito K. CREB3L2-mediated expression of Sec23A/Sec24D is involved in hepatic stellate cell activation through ER-Golgi transport. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7992. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08703-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pickard A., Garva R., Adamson A., Calverley B., Hoyle A., Hayward C., Spiller D., Lu Y., Hodson N., Swift J., Bigger B., Kadler K. ER-Golgi and lysosomal pathways together drive fibrous tissue formation. Research Square. 2022 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1336021/v1. [Preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z.Y., Keogh A., Waldt A., Cuttat R., Neri M., Zhu S., Schuierer S., Ruchti A., Crochemore C., Knehr J., Bastien J., Ksiazek I., Sanchez-Taltavull D., Ge H., Wu J., Roma G., Helliwell S.B., Stroka D., Nigsch F. Single-cell and bulk transcriptomics of the liver reveals potential targets of NASH with fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98806-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogata M., Hino S., Saito A., Morikawa K., Kondo S., Kanemoto S., Murakami T., Taniguchi M., Tanii I., Yoshinaga K., Shiosaka S., Hammarback J.A., Urano F., Imaizumi K. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yorimitsu T., Nair U., Yang Z., Klionsky D.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30299–30304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding W.X., Ni H.M., Gao W., Yoshimori T., Stolz D.B., Ron D., Yin X.M. Linking of autophagy to ubiquitin-proteasome system is important for the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell viability. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:513–524. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Altman B.J., Wofford J.A., Zhao Y., Coloff J.L., Ferguson E.C., Wieman H.L., Day A.E., Ilkayeva O., Rathmell J.C. Autophagy provides nutrients but can lead to Chop-dependent induction of Bim to sensitize growth factor-deprived cells to apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1180–1191. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.B'Chir W., Maurin A.C., Carraro V., Averous J., Jousse C., Muranishi Y., Parry L., Stepien G., Fafournoux P., Bruhat A. The eIF2alpha/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress-induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7683–7699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rouschop K.M., van den Beucken T., Dubois L., Niessen H., Bussink J., Savelkouls K., Keulers T., Mujcic H., Landuyt W., Voncken J.W., Lambin P., van der Kogel A.J., Koritzinsky M., Wouters B.G. The unfolded protein response protects human tumor cells during hypoxia through regulation of the autophagy genes MAP1LC3B and ATG5. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:127–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI40027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Margariti A., Li H., Chen T., Martin D., Vizcay-Barrena G., Alam S., Karamariti E., Xiao Q., Zampetaki A., Zhang Z., Wang W., Jiang Z., Gao C., Ma B., Chen Y.G., Cockerill G., Hu Y., Xu Q., Zeng L. XBP1 mRNA splicing triggers an autophagic response in endothelial cells through BECLIN-1 transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:859–872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gade P., Ramachandran G., Maachani U.B., Rizzo M.A., Okada T., Prywes R., Cross A.S., Mori K., Kalvakolanu D.V. An IFN-gamma-stimulated ATF6-C/EBP-beta-signaling pathway critical for the expression of death associated protein kinase 1 and induction of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10316–10321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119273109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoshida H., Matsui T., Yamamoto A., Okada T., Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fumagalli F., Noack J., Bergmann T.J., Cebollero E., Pisoni G.B., Fasana E., Fregno I., Galli C., Loi M., Solda T., D'Antuono R., Raimondi A., Jung M., Melnyk A., Schorr S., Schreiber A., Simonelli L., Varani L., Wilson-Zbinden C., Zerbe O., Hofmann K., Peter M., Quadroni M., Zimmermann R., Molinari M. Translocon component Sec62 acts in endoplasmic reticulum turnover during stress recovery. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:1173–1184. doi: 10.1038/ncb3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grumati P., Morozzi G., Holper S., Mari M., Harwardt M.I., Yan R., Muller S., Reggiori F., Heilemann M., Dikic I. Full length RTN3 regulates turnover of tubular endoplasmic reticulum via selective autophagy. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen Q., Xiao Y., Chai P., Zheng P., Teng J., Chen J. ATL3 is a tubular ER-phagy receptor for GABARAP-mediated selective autophagy. Curr Biol. 2019;29:846–855. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forrester A., De Leonibus C., Grumati P., Fasana E., Piemontese M., Staiano L., Fregno I., Raimondi A., Marazza A., Bruno G., Iavazzo M., Intartaglia D., Seczynska M., van Anken E., Conte I., De Matteis M.A., Dikic I., Molinari M., Settembre C. A selective ER-phagy exerts procollagen quality control via a calnexin-FAM134B complex. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.201899847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fregno I., Fasana E., Bergmann T.J., Raimondi A., Loi M., Solda T., Galli C., D'Antuono R., Morone D., Danieli A., Paganetti P., van Anken E., Molinari M. ER-to-lysosome-associated degradation of proteasome-resistant ATZ polymers occurs via receptor-mediated vesicular transport. EMBO J. 2018;37 doi: 10.15252/embj.201899259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang J.R., Lingeman E., Ahmed S., Corn J.E. Atlastins remodel the endoplasmic reticulum for selective autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3354–3367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201804185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nthiga T.M., Kumar Shrestha B., Sjottem E., Bruun J.A., Bowitz Larsen K., Bhujabal Z., Lamark T., Johansen T. CALCOCO1 acts with VAMP-associated proteins to mediate ER-phagy. EMBO J. 2020;39 doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith M.D., Harley M.E., Kemp A.J., Wills J., Lee M., Arends M., von Kriegsheim A., Behrends C., Wilkinson S. CCPG1 is a non-canonical autophagy cargo receptor essential for ER-phagy and pancreatic ER proteostasis. Dev Cell. 2018;44:217–232. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stephani M., Picchianti L., Gajic A., Beveridge R., Skarwan E., Sanchez de Medina Hernandez V., Mohseni A., Clavel M., Zeng Y., Naumann C., Matuszkiewicz M., Turco E., Loefke C., Li B., Durnberger G., Schutzbier M., Chen H.T., Abdrakhmanov A., Savova A., Chia K.S., Djamei A., Schaffner I., Abel S., Jiang L., Mechtler K., Ikeda F., Martens S., Clausen T., Dagdas Y. A cross-kingdom conserved ER-phagy receptor maintains endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis during stress. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.58396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang H., Ni H.M., Guo F., Ding Y., Shi Y.H., Lahiri P., Frohlich L.F., Rulicke T., Smole C., Schmidt V.C., Zatloukal K., Cui Y., Komatsu M., Fan J., Ding W.X. Sequestosome 1/p62 protein is associated with autophagic removal of excess hepatic endoplasmic reticulum in mice. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:18663–18674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.739821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kohno S., Shiozaki Y., Keenan A.L., Miyazaki-Anzai S., Miyazaki M. An N-terminal-truncated isoform of FAM134B (FAM134B-2) regulates starvation-induced hepatic selective ER-phagy. Life Sci Alliance. 2019;2 doi: 10.26508/lsa.201900340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fregno I., Fasana E., Solda T., Galli C., Molinari M. N-glycan processing selects ERAD-resistant misfolded proteins for ER-to-lysosome-associated degradation. EMBO J. 2021;40 doi: 10.15252/embj.2020107240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lucantoni F., Martinez-Cerezuela A., Gruevska A., Moragrega A.B., Victor V.M., Esplugues J.V., Blas-Garcia A., Apostolova N. Understanding the implication of autophagy in the activation of hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis: are we there yet? J Pathol. 2021;254:216–228. doi: 10.1002/path.5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hernandez-Gea V., Ghiassi-Nejad Z., Rozenfeld R., Gordon R., Fiel M.I., Yue Z., Czaja M.J., Friedman S.L. Autophagy releases lipid that promotes fibrogenesis by activated hepatic stellate cells in mice and in human tissues. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:938–946. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]