Abstract

In the liver, biliary epithelial cells (BECs) line intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBDs) and are primarily responsible for modifying and transporting hepatocyte-produced bile to the digestive tract. BECs comprise only 3% to 5% of the liver by cell number but are critical for maintaining choleresis through homeostasis and disease. To this end, BECs drive an extensive morphologic remodeling of the IHBD network termed ductular reaction (DR) in response to direct injury or injury to the hepatic parenchyma. BECs are also the target of a broad and heterogenous class of diseases termed cholangiopathies, which can present with phenotypes ranging from defective IHBD development in pediatric patients to progressive periductal fibrosis and cancer. DR is observed in many cholangiopathies, highlighting overlapping similarities between cell- and tissue-level responses by BECs across a spectrum of injury and disease. The following core set of cell biological BEC responses to stress and injury may moderate, initiate, or exacerbate liver pathophysiology in a context-dependent manner: cell death, proliferation, transdifferentiation, senescence, and acquisition of neuroendocrine phenotype. By reviewing how IHBDs respond to stress, this review seeks to highlight fundamental processes with potentially adaptive or maladaptive consequences. A deeper understanding of how these common responses contribute to DR and cholangiopathies may identify novel therapeutic targets in liver disease.

Ductular Reaction: A Common, but Heterogeneous Response to Liver Injury

In the healthy liver, biliary epithelial cells (BECs; used synonymously with the term cholangiocytes) line intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBDs) that form branching structures with large ducts and small ducts (termed ductules) running adjacent to the portal vein (Figure 1A). BECs are primarily responsible for transporting and modifying bile and exhibit morphologic, functional, and transcriptional heterogeneity associated in part with their anatomical location along the duct-ductule axis of the IHBDs.1, 2, 3 During homeostasis, BECs are largely quiescent and do not exhibit significant rates of proliferation or physiologic turnover. However, liver injury can induce a phenotype termed ductular reaction (DR), which is driven by BEC proliferation and dramatic remodeling of IHBDs both around and away from the portal vein.4 DR occurs in both acute injury, such as drug-induced liver injury (DILI), and in the setting of chronic hepatobiliary disease, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.5

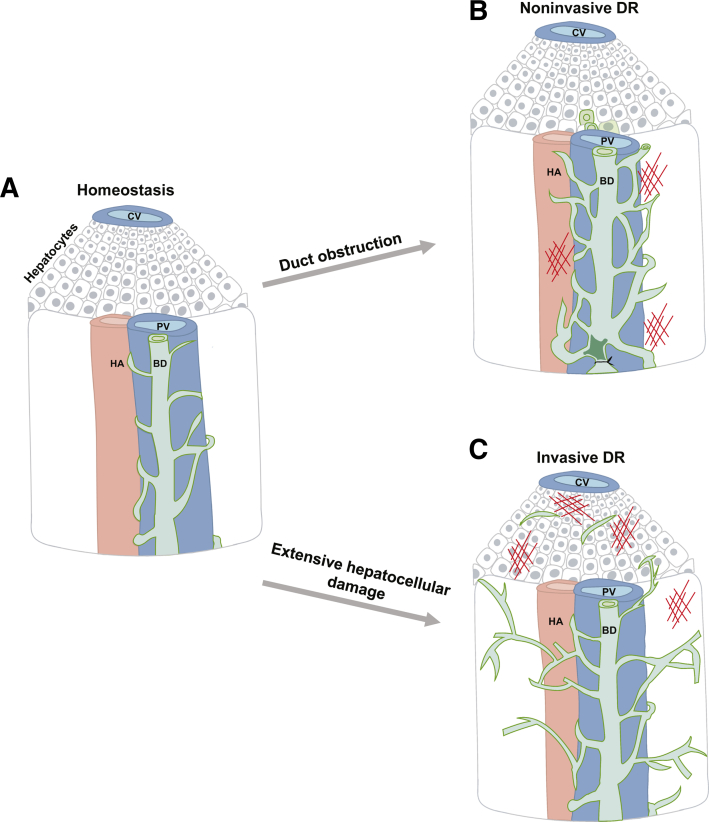

Figure 1.

Ductular reaction can be classified by parenchymal invasiveness. A: During homeostasis, bile ducts (BD; green) associate closely with the portal vein (PV; blue). B: Noninvasive DR, which is characterized by dilated ducts and minimal expansion of IHBDs away from the portal vein, is typically associated with direct biliary obstruction. C: In contrast, invasive DR is characterized by expansion of the IHBDs into the hepatic parenchyma and often observed with extensive hepatocellular injury. CV, central vein; HA, hepatic artery.

DR is a heterogenous response that varies across different human liver diseases and rodent models of liver injury. DR can be induced directly by damage to or blockage of the IHBDs or indirectly in response to hepatocellular injury. Cholestasis caused by direct obstruction of bile flow through IHBDs generally results in dilated ducts and minimal expansion of IHBDs away from the portal vein (Figure 1B). Because this type of DR maintains an anatomically close relationship with the portal vein, it is termed noninvasive DR. In humans, noninvasive DR occurs in PSC, in primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and following biliary obstruction.6 Rodent models of noninvasive DR include bile duct ligation (BDL) and 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) feeding.7, 8, 9 Three-dimensional confocal imaging and retrograde ink injection of noninvasive DRs exhibit defined lumens.10,11 Invasive DR generally results from extensive hepatocyte injury and is characterized the by expansion of IHBDs into the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 1C). In humans, invasive DR is seen in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis C.12 Rodent models for invasive DR include choline-deficient ethionine (CDE)–supplemented diet and thioacetamide (TAA) treatment.6,11 Invasive DR is hypothesized as being important to form de novo connections between bile ducts and hepatocyte canaliculi to promote bile removal and reduce bile-induced damage to hepatocytes.13,14 Earlier characterization of human liver disease denoted noninvasive DR as typical DR and invasive DR as atypical DR.15 However, this nomenclature has fallen out of use because it is considered somewhat subjective and implies distinct pathologic characteristics of atypical DR, such as premalignancy.15 Whether all BECs observed in DR are incorporated into the intrahepatic biliary tree has been the subject of speculation. Kaneko et al10 directly addressed duct continuity by co-localizing the BEC-specific marker cytokeratin 19 (CK19) with ink injected into the IHBDs of mice. The authors reported almost complete co-localization between CK19 and retrograde-injected ink in DDC, CDE, carbon tetrachloride, and TAA damage models by qualitative observation. This result suggests that both invasive and noninvasive DR results in a contiguous expansion of the biliary tree. It remains possible that quantitative analysis could reveal rare BECs that are discontinuous from the IHBDs during DR.

Many previous studies have proposed that liver injury is associated with activation of liver stem cells, often referred to as oval cells or liver progenitor cells that were originally speculated to migrate independently from the canals of Hering and/or bone marrow.16, 17, 18 Recent evidence challenges the existence of dedicated liver stem cells and demonstrates that liver regeneration is driven by mature cells, including hepatocytes that adopt BEC markers in mouse models of noninvasive DR.19 Retrograde ink injection and three-dimensional imaging has shown that parenchymal oval cells are consistent with invasive DR-associated BECs, which maintain continuity with IHBDs and may orient toward sites of injury.20, 21, 22 Likely, DR-associated BECs have acquired partial lineage plasticity enabling renewal of both BECs and, at times, hepatocytes during liver injury.

DR can be both beneficial and detrimental to promoting liver regeneration following injury and results in extracellular matrix (ECM) redistribution and deposition within the injured liver. However, the significance of ECM deposition and the role it plays in regulating DR is not well understood. Cholestasis induced by direct IHBD obstruction or indirectly by hepatocyte injury leads to an accumulation of bile and worsening hepatobiliary injury and inflammation.23 DR serves a protective function by maintaining choleresis. An increase in laminin deposition commonly occurs during DR.24, 25, 26 Previous work in liver development has shown that interactions between laminin, a component of the basal membrane, and the basement membrane help establish BEC polarity and support IHBD luminal structure necessary for removing bile and preventing cholestasis.27,28 Therefore, it is possible that choleresis is promoted during DR by increased deposition of laminin.29 However, laminin is just one component of a DR-associated niche composed of increased ECM, infiltrating immune cells, proinflammatory cytokines, and activated fibroblasts.30 During DR, the ratio of collagen type I and III to collagen type IV significantly increases.31,32 Collagens type I and III are components of the dense fibrillar network and are important in preserving tissue structure.31 However, when these components are in excess, they can disrupt cell signaling, resulting in the loss of cell polarity and ultimately tissue function.33 This switch in collagen deposition contributes to biliary fibrosis and biliary disease progression.34 Increased ECM deposition can be partially resolved following withdrawal of insult due to matrix metalloproteinase activity by immune cells and BECs.23 However, if uncontrolled and promoted by chronic liver injury, ECM deposition can lead to bridging fibrosis and impaired liver function.35 Because collagen is known to play a signaling role to adjacent cells, it is possible that the switch from type IV to types I and III collagen deposition may have an evolutionary benefit to DR that is yet to be established.36 This dual nature of ECM deposition during DR highlights the need to understand how other aspects of BEC biology promote liver regeneration and how they may also contribute to liver fibrosis. This may include reciprocal and dynamic interactions between BECs, other liver cell types, circulating immune cells, and the extracellular microenvironment.

Cholangiopathies

Cholangiopathies are chronic liver diseases that primarily affect BECs and are often progressive in nature. With minimal options for medical treatment, cholangiopathies often result in end-stage liver disease and require liver transplantation to extend survival.37 DR and associated fibrosis are often observed in cholangiopathies, varying by disease-specific origins. Cholangiopathies can be caused by known factors or idiopathic in nature and have at times been grouped by different classifications aimed at highlighting shared characteristics among specific diseases.37,38

Acquired Cholangiopathies

Acquired cholangiopathies can be caused by DILI, ischemia or reperfusion injury, or infectious disease.38 DILI-associated cholangiopathies can result from antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, herbal supplements, or recreational drugs, such as ketamine. Generally, these cholangiopathies cause small duct injury progressing to vanishing bile duct syndrome or large duct injury resulting in progressive secondary sclerosing cholangitis, sometimes involving DR.39 Ischemic cholangiopathy can occur from injury or surgical manipulation causing loss of blood supply to BECs. Ischemia is also thought to play a role in other cholangiopathies where fibrosis may restrict oxygen delivery to BECs.40 Infectious cholangiopathy is associated with viruses such as HIV/AIDS, occasionally resulting in liver inflammation and biliary strictures.41 AIDS-associated cholangiopathy is caused by opportunistic biliary infection of severely immunocompromised patients with pathogens such as Cryptosporidium parvum and cytomegalovirus.41 Direct infection of BECs in immunocompetent hosts, such as by SARS-CoV-2, may also contribute to the burden of acquired cholangiopathies. Although post–COVID-19 biliary complications are rare, SARS-CoV-2 infects BECs through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, and case reports describe instances of severe BEC injury with histologic features of secondary sclerosing cholangitis.42,43

Immune-Mediated Cholangiopathies

Although inflammation is common to BEC injury and disease, it is considered the primary cause of several cholangiopathies, including biliary atresia (BA), PBC, and PSC. BA is thought to be caused by early environmental or infectious injury in the developing livers of genetically susceptible hosts, resulting in fibroinflammatory cholestasis and persistent jaundice in infants.44 Patients with BA present a spectrum of dysregulated immune responses, including changes in Kupffer cells, T cells, and natural killer cells. Recent small conditional RNA–sequencing studies suggest that B-cell–mediated autoimmunity may play a key role in BA pathogenesis.45

PBC and PSC represent the most prevalent forms of immune-mediated cholangiopathies in adults and are also thought to arise from a complex interplay of environmental factors and host genetics. In PBC, which predominantly affects women, selective and progressive destruction of small IHBDs leads to cholestasis and fibrosis.46 Genome-wide association studies have identified several susceptibility loci associated with PBC, including genes belonging to the IL-12/IL-23, NF-κB, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α pathways, which are involved in self-tolerance and inflammation and could contribute to disease via these mechanisms.47, 48, 49 PSC is also thought to arise from environmental triggers in susceptible hosts but differs from PBC in origin, localization to either large or small IHBDs, and prevalence in males.37 Most patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease. Entry of microbial components into the portal circulation via a compromised gut epithelial barrier may be an important mechanism driving biliary inflammation in this patient population.50 Interestingly, both PBC and PSC can recur following liver transplantation, highlighting the central role of the host immune response in driving pathogenesis.51,52

Neoplastic Cholangiopathies

Cholangiocarcinomas are primary tumors arising from BECs and are more prevalent in the extrahepatic biliary tree. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) can arise from both small and large ducts, with some evidence that stem or progenitor-like cells of the large duct peribiliary glands may play an important role in tumorigenesis.53,54 PSC is a major risk factor for iCCA, and 10% to 20% of patients with PSC develop tumors.55 Although BECs are thought to be the primary source of iCCA, experimental evidence in animal models has shown that tumors can also arise from hepatocytes.56

Genetic Cholangiopathies

Rare autosomal dominant or recessive mutations can give rise to cholangiopathies by affecting duct development and/or function. Examples of genetic cholangiopathies include Alagille syndrome, progressive familial intrahepatic cholangitis (PFIC), and polycystic liver disease. Alagille syndrome is an autosomal dominant disease that results from mutations that impair Notch signaling.57 Because Notch signaling is required for proper IHBD development, infants with Alagille syndrome present with cholestasis secondary to ductal paucity.58 PFIC also presents with ductal paucity but refers to a heterogeneous group of autosomal recessive disorders in children that disrupt bile formation and present as cholestasis of hepatocellular origin.58,59 In PFIC, ductal paucity is thought to occur due to a loss in bile flow rather than BEC-autonomous impairment of IHBD development. Polycystic liver disease results from the hyperproliferation of BECs and the formation of cystic dilations of the bile ducts, driven by germline mutations. Autosomal dominant mutations in BEC-specific PRKCSH or SEC63 can cause primary polycystic liver disease. Additionally, polycystic liver disease can arise in some patients with polycystic kidney disease and is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in PKHD1 or dominant mutations in PKD1 or PKD2.60

Common BEC Responses to Injury

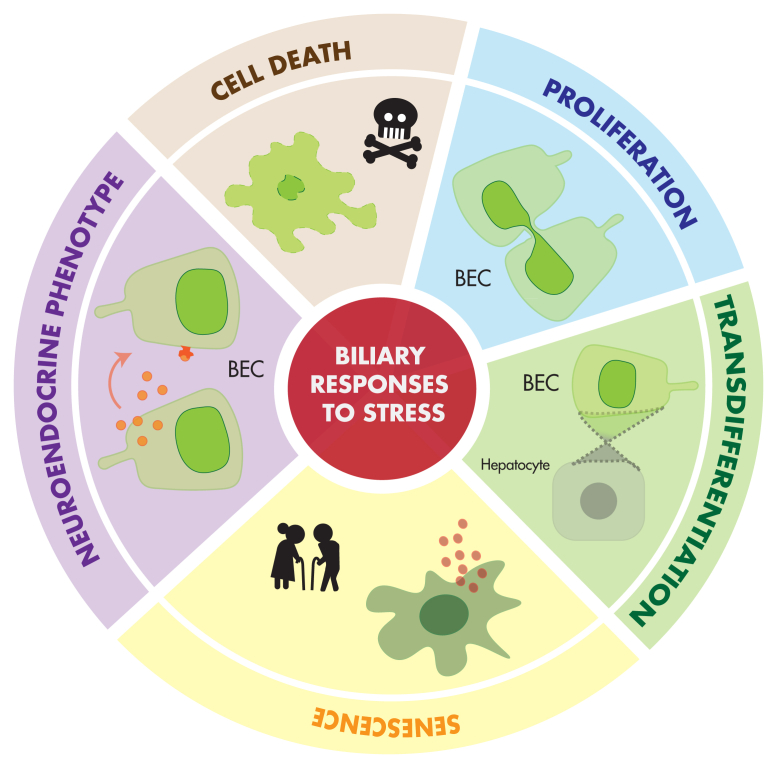

The sources of pathologic stimuli on BECs are broad and heterogeneous, including direct and indirect injuries, resulting in DR as well as genetic, idiopathic, and malignant causes of cholangiopathies. However, BEC responses to stress are often shared across distinct disease states and conditions, with commonalities in signaling pathways and cellular mechanisms. To approach these common responses from a cell biology perspective, we propose five processes associated with DR and cholangiopathies as a conceptual framework for understanding BEC pathophysiology: cell death, proliferation, transdifferentiation, senescence, and acquisition of neuroendocrine phenotype (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Common cellular responses in DR and cholangiopathies. Biliary epithelial cells mount common cellular responses across a range of liver injuries and diseases. Cell death, proliferation, transdifferentiation, senescence, and acquisition of neuroendocrine phenotype are identified as key features of the biliary epithelial cell stress response.

Cell Death

In the healthy liver, evidence suggests there is little to no BEC turnover via apoptosis.61 Liver injury can result in direct loss of BECs through different mechanisms of programmed and passive cell death. The most well-studied mechanisms for BEC death are apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis.61, 62, 63 These cell death mechanisms are usually intimately associated with inflammation, either as a consequence or cause, and may be particularly important in cholangiopathies associated with loss of IHBDs, such as PBC.64

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is an active, programmed pathway that triggers cell death, defined by the initiation of caspases to destroy cellular structure and organelles.65,66 The activation of this process induces a morphologic change in apoptotic BECs characterized by cytoplasmic and nuclear condensation and DNA damage, leading to the formation of apoptotic bodies, which are eliminated by phagocytosis.67,68 Apoptosis is a caspase-dependent cell death mechanism that can be activated through extrinsic or intrinsic pathways.

Extrinsic proapoptotic pathways are activated by ligand receptor binding, in which death receptors, such as TNF receptor, Fas, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand- receptor (TRAIL-R), bind to their corresponding ligands TNF-α, Apo2/TRAIL, and CD95/Fas ligand (FasL). This results in the activation of caspases 8 and 10, which, in turn, activate the executor caspases 3, 6, and 7.69, 70, 71 Tissue damage in liver injury is usually accompanied by a large number of infiltrating inflammatory cells. Proapoptotic ligands, chemokines, and cytokines are secreted by lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrating the IHBDs or by BECs themselves.72 Iwata et al73 demonstrated that monocytes surrounding damaged BECs are responsible for FasL production. Tsikrikoni et al74 reinforced the apoptotic significance of peribiliary FasL by showing a positive correlation between BEC expression of Fas receptor and BEC apoptosis in PBC. Similarly, TRAIL-R expression is increased in inflamed BECs,75 and patients with PBC have a high level of TRAIL in their serum.76,77

Intrinsic proapoptotic pathways can be activated by cellular stress, such as DNA damage, lack of growth factors, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, and detachment from the ECM.67 This pathway involves permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane and release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, triggering formation of a caspase 9–APAF1 apoptosome complex.78 This, in turn, activates executor caspases 3, 6, and 7. Permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane can also occur via reduction of Bcl2 signaling, which normally inhibits apoptotic progression. In PBC, antiapoptotic BCL2, MCL-1, and BCL-X are downregulated in damaged small bile ducts, promoting apoptosis.79 Intrinsic apoptosis can also be activated by the perforin/granzyme system. Cytotoxic T cells release granules that contain the perforin/granzyme B protein complex. Perforin forms a pore in the plasma membrane, whereas granzyme B is released into the cytosol. Hence, the granzyme activates the caspase 3 cascade, leading to apoptotic cell death.80 Clinical data show that patients with PBC demonstrate elevated expression of both granzymes and perforin transcripts in the small bile ducts.81

Necrosis

Necrosis refers to passive cell death that results from acute and severe metabolic dysfunctions, usually occurring in ischemia-reperfusion injury or drug-induced toxicity.82 Unlike apoptosis, necrosis is ATP independent. In ischemic cholangiopathy, bile acids leak through compromised cell-cell junctions and promote the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to cellular necrosis.83 Necrosis disrupts the cell membrane and induces cell lysis. Thus, BEC necrosis releases cellular components or damage-associated molecular patterns into the extracellular environment, which elicits a strong inflammatory response by the innate immune system.84,85 Consequently, a secondary cascade of damage and inflammation against the bile ducts is initiated, highlighting potentially complex interplay between different cell death mechanisms in DR and cholangiopathies.86

Necroptosis

Necroptosis is a form of controlled cell death like apoptosis. However, necroptosis acts independently of caspase and is regulated by the serine-threonine kinase receptor–interacting proteins (RIPs) 1 and 3.70 RIP1 and RIP3 form a complex to allow the phosphorylation of the mixed lineage kinase domain (MLKL), which is trimerized and translocated to the cell membrane, resulting in membrane rupture.87,88 Similar to secondary effects of necrosis, disruption of the cell membrane releases cytoplasmic contents, inducing damage-associated molecular pattern–dependent inflammatory reactions in neighboring cells.89 Elevated RIP3 and MLKL expression is observed in liver tissues from patients with PBC and mice subjected to BDL, indicating contribution of necroptosis to these pathophysiologic states. Furthermore, genetic deletion of RIP3 prevents necroptosis in mice after BDL injury.90 Recent studies on posttransplant liver tissue and samples from patients with cholangiopathies showed an up-regulation of RIP3 in cholangiocytes relative to hepatocytes, suggesting that necroptosis may be particularly important to BEC dysfunction.91

Pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is a programmed cell death mechanism associated with activation of the inflammasome. The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex containing i) a sensor, which is operated by the NOD-like receptor (NLR) family and PYHIN (Pyrin and HIN200) family, ii) an adapter (ASC), and iii) an effector protein (procaspase-1). Activation of inflammasome triggers caspase-1 signaling, releasing proinflammatory IL-1β and IL-8.92 In mice subjected to DDC injury and patients with PBC, expression of the central inflammasome component NLRP3 is increased in BECs, inducing pyroptotic cell death.93 These data indicate that pyroptosis plays an important role in cholangiopathies and DR.

Proliferation

In homeostasis, BECs are mostly mitotically quiescent, with reports of proliferation ranging from 1% to 5% of BECs in mouse models94 DR and cholangiopathies can result in rapid activation of proliferation in BECs. BEC proliferation is important for maintaining bile flow away from the liver and contributing to protective functions in DR, whereas in certain cholangiopathies (ie, PBC), it may compensate for loss of IHBDs. BEC proliferation during DR has been studied extensively in rodent models using BDL. In mice subjected to BDL, large ducts first enter the proliferative state, followed later by small ductules.9 As post-BDL injury progresses, the large ducts are more sensitive to damage, compromising their proliferation. At these later stages, small ductules can compensate for large duct injury by acquiring a large duct phenotype.95,96

Intracellular cAMP signaling plays an essential role in BEC proliferation. Post-BDL proliferation is activated by a cAMP/PKA/Src/MERK/ERK1/2 signaling cascade in large ducts,97 whereas the small ducts adopt a large duct phenotype via the IP3/Ca2+/calmodulin pathway.98 Nonepithelial cells can also influence BEC proliferation via niche signaling. Inhibition of Wnt secretion by macrophages inhibits the Wnt/B-catenin pathway and reduces biliary expansion.99 BECs receive blood supply from the peribiliary plexus vascular network. The growth factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and VEGF-C promote BEC proliferation during DR in the BDL model, further demonstrating the importance of BEC-niche interactions.55 Sensory innervation and neuropeptides also play a role in BEC proliferation. Inhibition or deletion of α-calcitonin gene-related peptide in mice inhibits BEC proliferation via the cAMP pathway following BDL.100 Recent studies, including small conditional RNA sequencing of mouse BECs isolated after 1 week of DDC administration, showed that BEC proliferation depends on YAP signaling.101 Independently, genetic ablation of YAP signaling was demonstrated to abolish BEC expansion in DDC-induced DR in mice.102 Using a model of invasive DR induced by TAA, Kamimoto et al22 applied clonal lineage tracing and three-dimensional imaging to demonstrate that de novo IHBD formation during DR is almost entirely the result of proliferation from the preexisting BECs. In the TAA model, which results in centrilobular hepatocyte injury, proliferating BECs migrate to damaged parenchyma via DR.22 The proliferative state of BECs was highly heterogeneous, with a small number of BEC clones exhibiting extensive postinjury proliferation and contributing to a large portion of the DR.22 Although the mechanisms influencing differential proliferative capacity of BECs in DR remain unclear, these studies highlight the importance of BEC heterogeneity to DR and cholangiopathies.1

In contrast to potential protective or compensatory functions of BEC proliferation in DR and cholangiopathies, uncontrolled proliferation may eventually lead to iCCA. In iCCA, BEC proliferation can be stimulated by the activation of epidermal growth factor receptor.103,104 As in DR, the YAP pathway is also involved in BEC proliferation, leading to iCCA. Several in vitro studies demonstrate the requirement of YAP pathway in the proliferation and progression of iCCA.105, 106, 107 BEC proliferation is induced and modulated by overlapping pathways in DR and cholangiopathies, which likely include a complex milieu of proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and bile acids. Additional studies are needed to determine the overlapping and unique components of BEC proliferation in different pathophysiologic contexts.

Transdifferentiation

In regeneration following partial hepatectomy or acute or mild hepatocellular injury, mature hepatocytes and BECs primarily regenerate their own populations.108 However, in response to severe or chronic liver injury, hepatocytes and BECs can undergo reciprocal transdifferentiation to regenerate the damaged liver. The plasticity of hepatocytes and BECs has now been well established using in vivo genetic lineage tracing in animal models. This plasticity appears to be triggered by injury combined with impaired regenerative response in one cell type triggering transdifferentiation of the other.20 Notably, the prevalence of hepatobiliary transdifferentiation in human disease (as well as its relevance in different DR and cholangiopathy-related contexts) remains unknown because of an inability to conduct gold standard in vivo lineage tracing assays in human samples.

BEC-to-Hepatocyte Transdifferentiation

BEC transdifferentiation into hepatocytes appears to be triggered primarily when hepatocyte proliferative capacity is impaired, most often in the setting of massive or chronic hepatocellular injury. To specifically trace the fate of BECs following various liver injury modalities, Raven et al109 used K19CreER:ROSA26LSL-tdTomato mice and simultaneously inhibited hepatocyte proliferation by overexpressing p21 or deleting the β1-integrin. They reported that approximately 20% to 30% of new hepatocytes are derived from BECs. A subsequent study demonstrated that biliary-derived hepatocytes contribute to 20% of total hepatocytes in CDE liver injury model following hepatocyte-specific knockout of β-catenin, which inhibits hepatocyte proliferation.110 Complementary studies in zebrafish models demonstrate that near-complete hepatocyte ablation drives BECs transdifferentiation into hepatocytes, preserving liver function.88 In mouse models, long-term administration of TAA and DDC promotes BEC plasticity in the absence of genetic modulation of hepatocytes, with BEC transdifferentiation accounting for 20.7% and 23.3% of new hepatocytes, respectively. Notably, BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation was only observed following 24 weeks of continuous liver injury, highlighting the importance of chronic damage in initiating cellular plasticity.111 Independent studies traced the fate of BECs using a different mouse model, OpnCreER:ROSA26LSL−YFP, demonstrating rare BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation following CDE injury that is more extensive following ≥8 weeks of carbon tetrachloride.112 In the latter report, BEC-derived hepatocytes were characterized and closely resembled fully functional hepatocytes, but with decreased apoptosis and increased capacity for DNA damage repair.13 Mechanisms driving BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation remain poorly defined but may hold therapeutic potential for liver diseases associated with hepatocyte loss or dysfunction.

Hepatocyte-to-BEC Transdifferentiation

In a similar but reciprocal process, recent studies demonstrate that hepatocytes may transdifferentiate to BECs to preserve IHBDs during liver injury that impairs BEC proliferation. Hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation was first demonstrated in rat models using transplant of dipeptidyl peptidase IV–positive hepatocytes into dipeptidyl peptidase IV–negative recipients before BDL. In this model, 1.75% of all keratin7+ biliary cells were dipeptidyl peptidase IV positive after BDL, increasing dramatically to 44.85% when BEC proliferation and repair were inhibited by methylene diamiline.113 Similar results were observed following transplantation of β-Gal–positive transgenic mouse hepatocytes into wild-type mice, which subsequently generated β-Gal–positive hepatocyte-derived BECs after 4 weeks of a DDC diet or 8 weeks of TAA liver injury.114 This process of hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation has also been referred to as hepatocyte metaplasia.21

Mechanistic regulation of hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation relies on pathways important for liver development and proliferation following injury. Constitutive expression of Notch1 in hepatocytes is sufficient to drive hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation.19 Conversely, Notch inhibition with N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-s-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) reduced hepatocyte transdifferentiation following BDL.115 Sox9 overexpression was shown to up-regulate Notch2 in a Jag1-deficient mouse model of Alagille syndrome, and Sox9 is up-regulated in peribiliary hepatocytes during DR, suggesting a transcriptional mechanism that might regulate Notch expression during hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation.116 YAP is also required for hepatocyte transdifferentiation, which is reduced following DDC injury in mice with hepatocyte-specific ablation of YAP signaling.101 Interestingly, YAP signaling also impacts the Notch pathway, promoting DR and hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation and highlighting the importance of crosstalk among major signaling pathways in hepatobiliary plasticity.117 In mouse models of extreme BA, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling drives replacement of the entire intrahepatic biliary tree in a Notch-independent manner.21 Elevated TGF-β was also observed in a portion of liver samples from human patients with Alagille syndrome.21 As in BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation, these studies suggest that hepatocytes may be a promising therapeutic target in settings where BECs are injured or compromised, such as PBC and PSC.

Finally, several studies have suggested that hepatocytes can be the cell of origin for some iCCA. In mice, hepatocyte-specific expression of constitutively active AKT and Notch signaling are sufficient to drive iCCA formation.56 Subsequent work identified other combinations of oncogene activation and tumor suppressor inhibition sufficient for driving hepatocyte-derived iCCA, including KRAS activation and p53 knockout.118 Lineage tracing was used to prove that hepatocyte transdifferentiation into malignant BECs is the predominant mechanism of tumorigenesis in a spontaneous, TAA-driven model of iCCA.119 Although similar mechanistic proof is unobtainable in patient samples, cell-of-origin predictions relying on somatic mutation analysis of whole exome and whole genome sequencing have suggested a hepatocyte origin for a subset of human iCCA.120 Interestingly, in silico prediction of hepatocyte origin was specifically correlated with iCCA in patients with hepatitis B or C.120 These studies imply that hepatocyte-to-BEC transdifferentiation may be a critical, disease-initiating process in some iCCAs and may involve similar pathways driving hepatobiliary plasticity in liver regeneration.

Senescence

Senescence is a state of cell cycle arrest associated with aging and has been hypothesized to play a tumor suppressive role.121,122 It differs from mitotic quiescence in that it is generally irreversible and associated with specific phenotypic changes. Although quiescent cells undergo reversible cell cycle arrest at G0, senescence-associated cell cycle arrest occurs in G1 and G2.123 Senescence can arise in response to cellular stress that results from chromatin instability, such as the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci.124 Senescence can also arise due to the DNA damage response and senescence-associated secretory phenotypes (SASPs).122,125, 126, 127, 128 Senescent cells can be identified morphologically, typically appearing larger with increased cytoplasm-nuclear ratios and an increased number of vacuoles relative to nonsenescent cells.129,130 No single marker reliably indicates senescence, so senescent cells are typically characterized by multiple markers. These markers include γ-H2AX, high expression of p16INK4a/Cdkn2a and p21WAF1/Cip1/Cdkn1a, senescence-associated β-galactosidase, DCR2, and/or 53BP1.72,131, 132, 133 A recent in vitro study identified a correlation between expression of IFIT3 and senescence in BECs.134

In BECs, senescence can be induced in vivo in response to oxidative stress, DNA damage, and chromatin instability and by serum deprivation in vitro.38 Telomere shortening is a cause of senescence often associated with age.135 In healthy human BECs and hepatocytes, telomere length is reported as being maintained regardless of age.136 In PBC, telomere shortening is observed in damaged small bile ducts coincident with expression of p21 or p16 and γH2AX, suggesting that telomere maintenance in BECs can fail, resulting in senescence or as a component of a senescent phenotype.137 The senescence marker p16 is also up-regulated in Mdr2−/− mice, a PSC model, and in vivo knockdown of p16 by RNA interference reduced IHBD mass, hepatic fibrosis, and expression of senescent markers in this model.138 Mdr2−/− mice have also been used to study the role of vimentin, a protein up-regulated in liver cells that undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition, in regulating biliary senescence. Similar to results for p16, in vivo knockdown of vimentin resulted in decreased BEC senescence, liver fibrosis, DR, and liver damage.139 Together, these studies provide proof-of-concept for senescence as a therapeutic target for cholangiopathies.

Senescent cells exert a feed forward loop of tissue senescence via SASPs, a proinflammatory response that can induce the senescent phenotype in adjacent cells. SASPs are characterized by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth modulators, angiogenic factors, proteases, bioactive lipids, ECM components, small exosome-like extracellular vesicles, and matrix metalloproteinases from senescent cells.126, 127, 128,140,141 Following liver injury, reactive oxygen species and DNA damage promote TGF-β signaling, which can induce SASPs.142,143 Studies in mouse models support the relevance of SASPs to liver pathophysiology. Ferreira-Gonzalez et al142 used a K19CreER:Mdm2fl/fl:ROSA26LSL-tdTomato model to induce senescence in bile ducts by BEC-specific ablation of Mdm2. The authors found that senescent BECs induce TGF-β–regulated paracrine senescence in surrounding BECs and hepatocytes.142 The expansion of senescence to neighboring BECs and hepatocytes demonstrates the significant impact senescence has on limiting liver regeneration when left unchecked.

Senescence has also been observed in both hepatocytes and bile ducts of adults and children with end-stage liver disease.144,145 Senescence exacerbates several malignant neoplasms, and p21WAF1/Cip1/Cdkn1a expression correlates with acute graft rejection after liver transplant.146 In addition to maladaptive consequences of senescence, SASPs may have protective functions in limiting profibrotic signals from hematopoietic stem cells and promoting liver regeneration.126,147 Some have even speculated that SASPs promote cellular plasticity in several tissues, including the liver.148,149 Furthermore, senescent cells are apoptosis resistant, likely to avoid self-destruction by detrimental SASP effects.38

Autophagy is induced during senescence and promotes the senescent phenotype.150 Autophagy is a genetically regulated program responsible for the turnover of cellular proteins and damaged organelles. Markers of autophagy include light chain 3β, lysosome-associated membrane protein 1, and cathepsin D. These markers correlate with markers of senescence (p16 and p21) in BEC vesicles of the inflamed and damaged small bile ducts of patients with PBC when compared with noninflamed small bile ducts in PBC and control livers.151 In cultured BECs, inhibition of autophagy suppresses cellular senescence.151

Biliary Neuroendocrine Phenotype

The term neuroendocrine was developed to describe cells originating from the neuroectoderm and exhibiting paracrine and/or endocrine functions.152 However, this concept has been revised to describe all cells that exhibit neuroendocrine markers, regardless of embryonic origin.153 Following stimulus, cells that previously were not classified as neuroendocrine can develop a neuroendocrine phenotype.154 The neuroendocrine phenotype presents in epithelial tissues and has been widely characterized in cancer, particularly in prostate cancer.155 Prostate cancer neuroendocrine phenotype cells produce various peptides, hormones, and growth factors, such as serotonin, VEGF, and chromogranin A (CHGA), that can stimulate proliferation in surrounding cells.155

During DR, a subpopulation of proliferating BECs adopts a neuroendocrine phenotype and can serve as a unique niche compartment, stimulating further proliferation and ECM deposition.156 This niche includes increased secretin (SCT) expression by neuroendocrine BECs, which can promote BEC function and proliferation.5,157 In both human PBC samples and the dominant negative TGF-β receptor II mouse model of late-stage PBC, biliary expression of Sct and SCT receptor (Sr) are decreased.158 Addition of SCT both in vitro and in vivo alleviates biliary injury and restores choleresis, bicarbonate secretion, and biliary maturation.158 These data suggest a link between injury-induced biliary neuroendocrine phenotype and SCT-mediated protection of biliary function.

The biliary neuroendocrine phenotype is characterized by expression of CHGA, glycolipid A2-B4, S-100, neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), neurotrophins, neurotrophin receptors, and neuroendocrine granules.156,159, 160, 161 The expression of neuroendocrine markers increases in BECs during prolonged and worsening liver damage.160 However, whether this increase in neuroendocrine marker expression results from more BECs adopting a neuroendocrine phenotype or a subpopulation of BECs increasing neuroendocrine marker expression is not known. Proliferating bile ducts and hybrid hepatocytes express low levels of CHGA following cholestasis.161,162 Subsequent studies demonstrate that the biliary neuroendocrine phenotype is most often associated with smaller ductules following liver injury.159 Parathyroid hormone–related peptide is associated with neuroendocrine phenotype reactive ductules and stimulates DNA synthesis, further promoting proliferation.159 Acquisition of a neuroendocrine phenotype by BECs can lead to rare biliary neuroendocrine tumors, which are generally more malignant than other forms of cholangiocarcinoma.163 Understanding the impacts of the neuroendocrine phenotype on BEC proliferation is important for dissecting its role in adaptive proliferation and duct expansion during DR versus potential tumorigenesis.

Integrating Individual Features of BEC Stress Response to Understand BEC Pathophysiology

Collectively, BECs respond to injury and pathophysiologic stimulus by mounting a complex and heterogeneous range of cellular responses, and many (if not all) of the features discussed here co-occur within DR and cholangiopathies. Understanding the full landscape of cellular responses to stress within a single injury or disease state remains a significant challenge. Although beyond the scope of this review, the interaction between BECs and the larger cellular microenvironment is also an important consideration. A classic example of BEC-niche interactions that influence cellular responses to stress can be found in studies of sensory innervation of the IHBDs from the 1990s, which initially described innervation of the IHBDs by calcitonin gene-related peptide–positive spinal afferent neurons.164 In rats, surgical resection of the vagal nerve before BDL-induced cholestasis resulted in impaired DR, with decreased BEC proliferation, increased BEC apoptosis, and a significant decrease in bile secretion.95 These studies suggest that innervation of the IHBDs influences a number of BEC stress responses and may warrant additional follow-up studies as interest in the gut-brain axis and new technological advances for studying these cellular interactions emerge.

Another challenge to better understanding BEC stress response is dissecting how overlapping molecular signals integrate to drive distinct phenotypic outcomes at the cellular level. A particularly complex example is found in Notch signaling, which is involved in many different aspects of BEC biology, including specification during development, proliferation, and transdifferentiation. Notch activation is known to be critical for BEC differentiation from hepatoblasts, where it results in activation of Sox9 and acquisition of cholangiocyte identity.165,166 Subsequent studies provided conflicting evidence for the role of Notch in reinforcing BEC identity during adult DR. Notch ligands, particularly Jagged-1, reinforce BEC identity during DR associated with DDC injury.167 Independent studies demonstrated that deletion of Rbpj, a downstream transcriptional effector of Notch, had no effect on BEC identity or BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation during DR.168 Regardless, multiple different experimental approaches linked Notch to BEC proliferation in response to injury, complicating the relationship between BEC expansion and BEC identity.168,169 More recent studies sought to clarify the link between Notch activation after liver injury and both BEC proliferation and BEC-to-hepatocyte transdifferentiation.170 In contrast to ongoing cycles of injury, proliferation, and transdifferentiation induced by chemical injury models, Minnis-Lyons et al170 temporally synchronized BEC transdifferentiation using an inducible Mdm2 knockout mouse model in which hepatocytes are simultaneously damaged and impaired from self-replicating. The authors found that Notch1 and Notch3 were nonredundantly required to initiate BEC proliferation, which was, in turn, required for later transdifferentiation into hepatocytes.170 Mechanistically, Notch activation induced expression of IGFR1 and stimulation of BECs with IGF-1 promoted proliferation while suppressing transdifferentiation.170 Together, these studies provide a comprehensive example of how two phenotypically distinct features of BEC stress response are mechanistically linked by a single signaling pathway. They highlight both temporal complexity and influence of secondary signaling pathways on how BECs respond to stress, suggesting the need for further research into downstream effectors responsible for regulating phenotypic outcomes in DR and cholangiopathies.

Conclusions

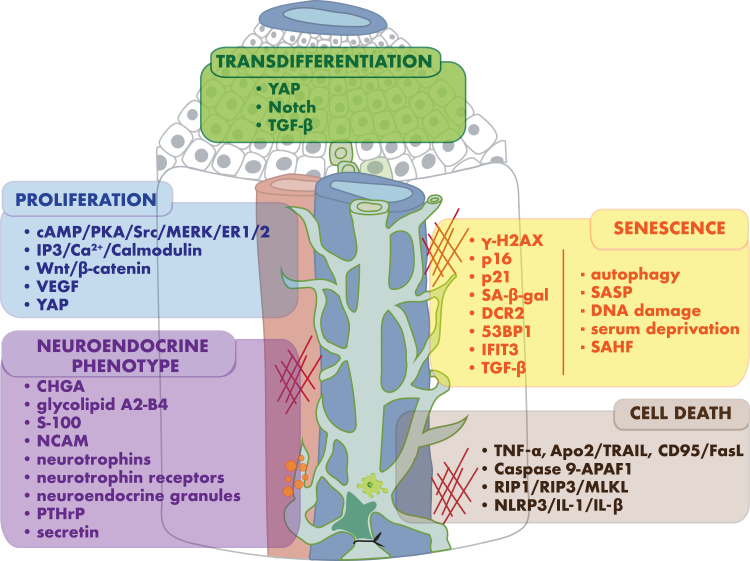

Between their role in DR and cholangiopathies, BECs are significant players in the pathophysiology of the liver. Our understanding of how BECs respond to stress and injury at the cellular and molecular levels remains incomplete. Unique challenges in studying BEC pathophysiology include their scarcity (3% to 5% of the total cell number in the liver), complex branching morphology of the IHBDs, and the heterogeneous nature of cholangiopathies, many of which are rare as individual syndromes. We set out to define a basic framework for approaching BEC responses to stress and injury, modeled after conceptual hallmarks that have been established for broad pathophysiologic processes, such as cancer and aging.135,171 In the case of DR and cholangiopathies, these processes represent true hallmarks of BEC stress response. Conceptually, for a cellular process to represent a hallmark, it would have to be required across the full spectrum of DR and cholangiopathies. As noted in specific examples above, different pathologic settings may involve a different milieu of cellular responses, influenced by redundant and overlapping signaling pathways (Figure 3). For example, some mouse models of DR proceed primarily via self-replication of existing BECs, whereas others exhibit higher rates of hepatobiliary metaplasia.11,19 Furthermore, the interaction between different cellular responses to BEC stress and injury is likely critical for certain cholangiopathies, such as the interaction between inflammation-induced cell death and senescence observed in PSC.72 Although this list of common cellular responses is not exhaustive, it is a conceptual starting point for approaching the complex cell biology of BEC injury and disease.

Figure 3.

Biomarkers and pathways associated with biliary epithelial cell responses to stress and injury. Signaling pathways activated in response to direct and indirect stimuli drive functional features of the biliary epithelial cell stress response: transdifferentiation, proliferation, senescence, cell death, and acquisition of neuroendocrine phenotype.

Acknowledgment

We thank Hengrui Zhang for helpful discussions and feedback.

Footnotes

Stress Responses and Cellular Crosstalk in the Pathogenesis of Liver Disease Theme Issue

Supported by NIH grants R01 DK132653 (A.D.G.) and F31 DK134199 (H.R.H).

H.R.H. and F.H. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

This article is part of a review series focused on the role of cellular stress in driving molecular crosstalk between hepatic cells that may contribute to the development, progression, or pathogenesis of liver diseases.

Author Contributions

H.R.H. and F.H. generated the figures; and H.R.H., F.H., and A.D.G. wrote and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hrncir H.R., Gracz A.D. Cellular and transcriptional heterogeneity in the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Gastro Hep Adv. 2022;2:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2022.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanno N., Lesage G., Glaser S., Alvaro D., Alpini G. Functional heterogeneity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2000;31:555–561. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaser S.S., Gaudio E., Rao A., Pierce L.M., Onori P., Franchitto A., Francis H.L., Dostal D.E., Venter J.K., DeMorrow S., Mancinelli R., Carpino G., Alvaro D., Kopriva S.E., Savage J.M., Alpini G.D. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest. 2009;89:456–469. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gouw A.S., Clouston A.D., Theise N.D. Ductular reactions in human liver: diversity at the interface. Hepatology. 2011;54:1853–1863. doi: 10.1002/hep.24613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou T., Kundu D., Robles-Linares J., Meadows V., Sato K., Baiocchi L., Ekser B., Glaser S., Alpini G., Francis H., Kennedy L. Feedback signaling between cholangiopathies, ductular reaction, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cells. 2021;10:2072. doi: 10.3390/cells10082072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clerbaux L.-A., Van Hul N., Gouw A., Manco R., Español-Suñer R., Leclercq I. 2018. Relevance of the CDE and DDC Mouse Models to Study Ductular Reaction in Chronic Human Liver Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guldiken N., Kobazi Ensari G., Lahiri P., Couchy G., Preisinger C., Liedtke C., Zimmermann H.W., Ziol M., Boor P., Zucman-Rossi J., Trautwein C., Strnad P. Keratin 23 is a stress-inducible marker of mouse and human ductular reaction in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fickert P., Stöger U., Fuchsbichler A., Moustafa T., Marschall H.-U., Weiglein A.H., Tsybrovskyy O., Jaeschke H., Zatloukal K., Denk H., Trauner M. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:525–536. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgiev P., Jochum W., Heinrich S., Jang J.H., Nocito A., Dahm F., Clavien P.A. Characterization of time-related changes after experimental bile duct ligation. Br J Surg. 2008;95:646–656. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko K., Kamimoto K., Miyajima A., Itoh T. Adaptive remodeling of the biliary architecture underlies liver homeostasis. Hepatology. 2015;61:2056–2066. doi: 10.1002/hep.27685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamimoto K., Nakano Y., Kaneko K., Miyajima A., Itoh T. Multidimensional imaging of liver injury repair in mice reveals fundamental role of the ductular reaction. Commun Biol. 2020;3:289. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-1006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill R.M., Belt P., Wilson L., Bass N.M., Ferrell L.D. Centrizonal arteries and microvessels in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1400–1404. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182254283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clerbaux L.-A., Manco R., Van Hul N., Bouzin C., Sciarra A., Sempoux C., Theise N.D., Leclercq I.A. Invasive ductular reaction operates hepatobiliary junctions upon hepatocellular injury in rodents and humans. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overi D., Carpino G., Cristoferi L., Onori P., Kennedy L., Francis H., Zucchini N., Rigamonti C., Viganò M., Floreani A., D'Amato D., Gerussi A., Venere R., Alpini G., Glaser S., Alvaro D., Invernizzi P., Gaudio E., Cardinale V., Carbone M. Role of ductular reaction and ductular-canalicular junctions in identifying severe primary biliary cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 2022:100556. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roskams T.A., Theise N.D., Balabaud C., Bhagat G., Bhathal P.S., Bioulac-Sage P., Brunt E.M., Crawford J.M., Crosby H.A., Desmet V., Finegold M.J., Geller S.A., Gouw A.S., Hytiroglou P., Knisely A.S., Kojiro M., Lefkowitch J.H., Nakanuma Y., Olynyk J.K., Park Y.N., Portmann B., Saxena R., Scheuer P.J., Strain A.J., Thung S.N., Wanless I.R., West A.B. Nomenclature of the finer branches of the biliary tree: canals, ductules, and ductular reactions in human livers. Hepatology. 2004;39:1739–1745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan A.W., Dorrell C., Grompe M. Stem cells and liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:466–481. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen B.E., Bowen W.C., Patrene K.D., Mars W.M., Sullivan A.K., Murase N., Boggs S.S., Greenberger J.S., Goff J.P. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science. 1999;284:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alison M.R., Poulsom R., Jeffery R., Dhillon A.P., Quaglia A., Jacob J., Novelli M., Prentice G., Williamson J., Wright N.A. Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature. 2000;406:257. doi: 10.1038/35018642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanger K., Zong Y., Maggs L.R., Shapira S.N., Maddipati R., Aiello N.M., Thung S.N., Wells R.G., Greenbaum L.E., Stanger B.Z. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 2013;27:719–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.207803.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadd V.L., Aleksieva N., Forbes S.J. Epithelial plasticity during liver injury and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:557–573. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaub J.R., Huppert K.A., Kurial S.N.T., Hsu B.Y., Cast A.E., Donnelly B., Karns R.A., Chen F., Rezvani M., Luu H.Y., Mattis A.N., Rougemont A.-L., Rosenthal P., Huppert S.S., Willenbring H. De novo formation of the biliary system by TGFβ-mediated hepatocyte transdifferentiation. Nature. 2018;557:247–251. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamimoto K., Kaneko K., Kok C.Y., Okada H., Miyajima A., Itoh T. Heterogeneity and stochastic growth regulation of biliary epithelial cells dictate dynamic epithelial tissue remodeling. Elife. 2016;5:e15034. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duarte S., Baber J., Fujii T., Coito A.J. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44-46:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallis Y.N., Robson A.J., Fallowfield J.A., Thomas H.C., Alison M.R., Wright N.A., Goldin R.D., Iredale J.P., Forbes S.J. Remodelling of extracellular matrix is a requirement for the hepatic progenitor cell response. Gut. 2011;60:525–533. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzini S., Bird T.G., Boulter L., Bellamy C., Samuel K., Aucott R., Clayton E., Andreone P., Bernardi M., Golding M., Alison M.R., Iredale J.P., Forbes S.J. Characterisation of a stereotypical cellular and extracellular adult liver progenitor cell niche in rodents and diseased human liver. Gut. 2010;59:645–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.182345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mak K.M., Chen L.L., Lee T.-F. Codistribution of collagen type IV and laminin in liver fibrosis of elderly cadavers: immunohistochemical marker of perisinusoidal basement membrane formation. Anat Rec. 2013;296:953–964. doi: 10.1002/ar.22694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai S.Y., Boyer J.L. The role of bile acids in cholestatic liver injury. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:737. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanimizu N., Kikkawa Y., Mitaka T., Miyajima A. α1- and α5-containing laminins regulate the development of bile ducts via β1 integrin signals. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28586–28597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.350488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryhanen L., Stenback F., Ala-Kokko L., Savolainen E.R. The effect of malotilate on type III and type IV collagen, laminin and fibronectin metabolism in dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver fibrosis in the rat. J Hepatol. 1996;24:238–245. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells R.G. Cellular sources of extracellular matrix in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.07.008. viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baiocchini A., Montaldo C., Conigliaro A., Grimaldi A., Correani V., Mura F., Ciccosanti F., Rotiroti N., Brenna A., Montalbano M., D'Offizi G., Capobianchi M.R., Alessandro R., Piacentini M., Schininà M.E., Maras B., Del Nonno F., Tripodi M., Mancone C. Extracellular matrix molecular remodeling in human liver fibrosis evolution. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuppan D. Structure of the extracellular matrix in normal and fibrotic liver: collagens and glycoproteins. Semin Liver Dis. 1990:1–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ezzell R.M., Toner M., Hendricks K., Dunn J.C., Tompkins R.G., Yarmush M.L. Effect of collagen gel configuration on the cytoskeleton in cultured rat hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1993;208:442–452. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellicoro A., Ramachandran P., Iredale J.P. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:S26. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klingberg F., Hinz B., White E.S. The myofibroblast matrix: implications for tissue repair and fibrosis. J Pathol. 2013;229:298–309. doi: 10.1002/path.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karsdal M.A., Nielsen S.H., Leeming D.J., Langholm L.L., Nielsen M.J., Manon-Jensen T., Siebuhr A., Gudmann N.S., Rønnow S., Sand J.M., Daniels S.J., Mortensen J.H., Schuppan D. The good and the bad collagens of fibrosis – Their role in signaling and organ function. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lazaridis K.N., LaRusso N.F. The cholangiopathies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trussoni C.E., O'Hara S.P., LaRusso N.F. Cellular senescence in the cholangiopathies: a driver of immunopathology and a novel therapeutic target. Semin Immunopathol. 2022;44:527–544. doi: 10.1007/s00281-022-00909-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scoazec J.Y. Drug-induced bile duct injury: new agents, new mechanisms. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38:83–88. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deltenre P., Valla D.-C. Ischemic cholangiopathy. J Hepatol. 2006;44:806–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naseer M., Dailey F.E., Juboori A.A., Samiullah S., Tahan V. Epidemiology, determinants, and management of AIDS cholangiopathy: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:767–774. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i7.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao B., Ni C., Gao R., Wang Y., Yang L., Wei J., Lv T., Liang J., Zhang Q., Xu W., Xie Y., Wang X., Yuan Z., Liang J., Zhang R., Lin X. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and cholangiocyte damage with human liver ductal organoids. Protein Cell. 2020;11:771–775. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roth N.C., Kim A., Vitkovski T., Xia J., Ramirez G., Bernstein D., Crawford J.M. Post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy: a novel entity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1077–1082. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asai A., Miethke A., Bezerra J.A. Pathogenesis of biliary atresia: defining biology to understand clinical phenotypes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:342–352. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J., Xu Y., Chen Z., Liang J., Lin Z., Liang H., et al. Liver immune profiling reveals pathogenesis and therapeutics for biliary atresia. Cell. 2020;183:1867–1883.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carey E.J., Ali A.H., Lindor K.D. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386:1565–1575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carbone M., Lleo A., Sandford R.N., Invernizzi P. Implications of genome-wide association studies in novel therapeutics in primary biliary cirrhosis. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:945–954. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mells G.F., Floyd J.A.B., Morley K.I., Cordell H.J., Franklin C.S., Shin S.-Y., Heneghan M.A., Neuberger J.M., Donaldson P.T., Day D.B., Ducker S.J., Muriithi A.W., Wheater E.F., Hammond C.J., Dawwas M.F., Jones D.E., Peltonen L., Alexander G.J., Sandford R.N., Anderson C.A., The UKPBCC. The Wellcome Trust Case Control C Genome-wide association study identifies 12 new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:329–332. doi: 10.1038/ng.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura M., Nishida N., Kawashima M., Aiba Y., Tanaka A., Yasunami M., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies TNFSF15 and POU2AF1 as susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis in the japanese population. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:721–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakamoto N., Sasaki N., Aoki R., Miyamoto K., Suda W., Teratani T., Suzuki T., Koda Y., Chu P.S., Taniki N., Yamaguchi A., Kanamori M., Kamada N., Hattori M., Ashida H., Sakamoto M., Atarashi K., Narushima S., Yoshimura A., Honda K., Sato T., Kanai T. Gut pathobionts underlie intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver T helper 17 cell immune response in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:492–503. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silveira M.G., Talwalkar J.A., Lindor K.D., Wiesner R.H. Recurrent primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:720–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fosby B., Karlsen T.H., Melum E. Recurrence and rejection in liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1–15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terada T., Nakanuma Y. Pathological observations of intrahepatic peribiliary glands in 1,000 consecutive autopsy livers. II. A possible source of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 1990;12:92–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayata Y., Nakagawa H., Kurosaki S., Kawamura S., Matsushita Y., Hayakawa Y., Suzuki N., Hata M., Tsuboi M., Kinoshita H., Miyabayashi K., Mizutani H., Nakagomi R., Ikenoue T., Hirata Y., Arita J., Hasegawa K., Tateishi K., Koike K. Axin2(+) peribiliary glands in the periampullary region generate biliary epithelial stem cells that give rise to ampullary carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2133–2148.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banales J.M., Marin J.J.G., Lamarca A., Rodrigues P.M., Khan S.A., Roberts L.R., Cardinale V., Carpino G., Andersen J.B., Braconi C., Calvisi D.F., Perugorria M.J., Fabris L., Boulter L., Macias R.I.R., Gaudio E., Alvaro D., Gradilone S.A., Strazzabosco M., Marzioni M., Coulouarn C., Fouassier L., Raggi C., Invernizzi P., Mertens J.C., Moncsek A., Rizvi S., Heimbach J., Koerkamp B.G., Bruix J., Forner A., Bridgewater J., Valle J.W., Gores G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan B., Malato Y., Calvisi D.F., Naqvi S., Razumilava N., Ribback S., Gores G.J., Dombrowski F., Evert M., Chen X., Willenbring H. Cholangiocarcinomas can originate from hepatocytes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2911–2915. doi: 10.1172/JCI63212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gilbert M.A., Spinner N.B. Alagille syndrome: genetics and functional models. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alonso E.M., Snover D.C., Montag A., Freese D.K., Whitington P.F. Histologic pathology of the liver in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:128–133. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davit-Spraul A., Gonzales E., Baussan C., Jacquemin E. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olaizola P., Rodrigues P.M., Caballero-Camino F.J., Izquierdo-Sanchez L., Aspichueta P., Bujanda L., Larusso N.F., Drenth J.P.H., Perugorria M.J., Banales J.M. Genetics, pathobiology and therapeutic opportunities of polycystic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:585–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakanuma Y., Tsuneyama K., Harada K. Pathology and pathogenesis of intrahepatic bile duct loss. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s005340170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakanuma Y., Sasaki M., Harada K. Autophagy and senescence in fibrosing cholangiopathies. J Hepatol. 2015;62:934–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lockshin R.A., Zakeri Z. Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2405–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peltzer N., Walczak H. Cell Death and Inflammation - a vital but dangerous liaison. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:387–402. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Danial N.N., Korsmeyer S.J. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green D.R. Apoptotic pathways: ten minutes to dead. Cell. 2005;121:671–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fulda S., Debatin K.M. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koga H., Sakisaka S., Ohishi M., Sata M., Tanikawa K. Nuclear DNA fragmentation and expression of Bcl-2 in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1997;25:1077–1084. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ashkenazi A., Dixit V.M. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guicciardi M.E., Gores G.J. Life and death by death receptors. FASEB J. 2009;23:1625–1637. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Waring P., Mullbacher A. Cell death induced by the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and its role in pathology. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:312–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tabibian J.H., O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Trussoni C.E., LaRusso N.F. Cholangiocyte senescence by way of N-ras activation is a characteristic of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:2263–2275. doi: 10.1002/hep.26993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iwata M., Harada K., Hiramatsu K., Tsuneyama K., Kaneko S., Kobayashi K., Nakanuma Y. Fas ligand expressing mononuclear cells around intrahepatic bile ducts co-express CD68 in primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver. 2000;20:129–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020002129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsikrikoni A., Kyriakou D.S., Rigopoulou E.I., Alexandrakis M.G., Zachou K., Passam F., Dalekos G.N. Markers of cell activation and apoptosis in bone marrow mononuclear cells of patients with autoimmune hepatitis type 1 and primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheung A.C., LaRusso N.F., Gores G.J., Lazaridis K.N. Epigenetics in the primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2017;37:159–174. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang Y., Yang Z., Li C., Zhu Y., Zhang L., Zhong R. Characterisation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in peripheral blood in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Exp Med. 2008;8:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10238-008-0149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelli N., Floreani A., Torre F., Delfino A., Baragiotta A., Contini P., Basso M., Picciotto A. Soluble apoptosis molecules in primary biliary cirrhosis: analysis and commitment of the Fas and tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand systems in comparison with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kroemer G., Reed J.C. Mitochondrial control of cell death. Nat Med. 2000;6:513–519. doi: 10.1038/74994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iwata M., Harada K., Kono N., Kaneko S., Kobayashi K., Nakanuma Y. Expression of Bcl-2 familial proteins is reduced in small bile duct lesions of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Voskoboinik I., Whisstock J.C., Trapani J.A. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:388–400. doi: 10.1038/nri3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fox C.K., Furtwaengler A., Nepomuceno R.R., Martinez O.M., Krams S.M. Apoptotic pathways in primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis. Liver. 2001;21:272–279. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2001.021004272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xia X., Demorrow S., Francis H., Glaser S., Alpini G., Marzioni M., Fava G., Lesage G. Cholangiocyte injury and ductopenic syndromes. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:401–412. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kobayashi S., Kozaka K., Gabata T., Matsui O., Koda W., Okuda M., Okumura K., Sugiura T., Ogi T. Pathophysiology and imaging findings of bile duct necrosis: a rare but serious complication of transarterial therapy for liver tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2596. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O'Hara S.P., Tabibian J.H., Splinter P.L., LaRusso N.F. The dynamic biliary epithelia: molecules, pathways, and disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malhi H., Guicciardi M.E., Gores G.J. Hepatocyte death: a clear and present danger. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1165–1194. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00061.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harada K., Nakanuma Y. Biliary innate immunity in the pathogenesis of biliary diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2010;9:83–90. doi: 10.2174/187152810791292809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang H., Sun L., Su L., Rizo J., Liu L., Wang L.F., Wang F.S., Wang X. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell. 2014;54:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cai Z., Jitkaew S., Zhao J., Chiang H.C., Choksi S., Liu J., Ward Y., Wu L.G., Liu Z.G. Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:55–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weinlich R., Oberst A., Beere H.M., Green D.R. Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:127–136. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Afonso M.B., Rodrigues P.M., Simao A.L., Ofengeim D., Carvalho T., Amaral J.D., Gaspar M.M., Cortez-Pinto H., Castro R.E., Yuan J., Rodrigues C.M. Activation of necroptosis in human and experimental cholestasis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2390. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shi S., Verstegen M.M.A., Roest H.P., Ardisasmita A.I., Cao W., Roos F.J.M., de Ruiter P.E., Niemeijer M., Pan Q., JNM I.J., van der Laan L.J.W. Recapitulating cholangiopathy-associated necroptotic cell death in vitro using human cholangiocyte organoids. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:541–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Broz P., Dixit V.M. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maroni L., Agostinelli L., Saccomanno S., Pinto C., Giordano D.M., Rychlicki C., De Minicis S., Trozzi L., Banales J.M., Melum E., Karlsen T.H., Benedetti A., Baroni G.S., Marzioni M. Nlrp3 activation induces Il-18 synthesis and affects the epithelial barrier function in reactive cholangiocytes. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Masyuk A.I., Masyuk T.V., Tietz P.S., Splinter P.L., LaRusso N.F. Intrahepatic bile ducts transport water in response to absorbed glucose. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C785–C791. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00118.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.LeSage G.D., Benedetti A., Glaser S., Marucci L., Tretjak Z., Caligiuri A., Rodgers R., Phinizy J.L., Baiocchi L., Francis H. Acute carbon tetrachloride feeding selectively damages large, but not small, cholangiocytes from normal rat liver. Hepatology. 1999;29:307–319. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mancinelli R., Franchitto A., Glaser S., Meng F., Onori P., Demorrow S., Francis H., Venter J., Carpino G., Baker K., Han Y., Ueno Y., Gaudio E., Alpini G. GABA induces the differentiation of small into large cholangiocytes by activation of Ca(2+)/CaMK I-dependent adenylyl cyclase 8. Hepatology. 2013;58:251–263. doi: 10.1002/hep.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Francis H., Glaser S., Ueno Y., Lesage G., Marucci L., Benedetti A., Taffetani S., Marzioni M., Alvaro D., Venter J., Reichenbach R., Fava G., Phinizy J.L., Alpini G. cAMP stimulates the secretory and proliferative capacity of the rat intrahepatic biliary epithelium through changes in the PKA/Src/MEK/ERK1/2 pathway. J Hepatol. 2004;41:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mancinelli R., Franchitto A., Gaudio E., Onori P., Glaser S., Francis H., Venter J., Demorrow S., Carpino G., Kopriva S., White M., Fava G., Alvaro D., Alpini G. After damage of large bile ducts by gamma-aminobutyric acid, small ducts replenish the biliary tree by amplification of calcium-dependent signaling and de novo acquisition of large cholangiocyte phenotypes. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1790–1800. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang J., Mowry L.E., Nejak-Bowen K.N., Okabe H., Diegel C.R., Lang R.A., Williams B.O., Monga S.P. β-catenin signaling in murine liver zonation and regeneration: a Wnt-Wnt situation! Hepatology. 2014;60:964–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.27082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Glaser S.S., Ueno Y., DeMorrow S., Chiasson V.L., Katki K.A., Venter J., Francis H.L., Dickerson I.M., DiPette D.J., Supowit S.C., Alpini G.D. Knockout of α-calcitonin gene-related peptide reduces cholangiocyte proliferation in bile duct ligated mice. Lab Invest. 2007;87:914–926. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pepe-Mooney B.J., Dill M.T., Alemany A., Ordovas-Montanes J., Matsushita Y., Rao A., Sen A., Miyazaki M., Anakk S., Dawson P.A., Ono N., Shalek A.K., van Oudenaarden A., Camargo F.D. Single-cell analysis of the liver epithelium reveals dynamic heterogeneity and an essential role for YAP in homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:23–38.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Planas-Paz L., Sun T., Pikiolek M., Cochran N.R., Bergling S., Orsini V., et al. YAP, but not RSPO-LGR4/5, signaling in biliary epithelial cells promotes a ductular reaction in response to liver injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:39–53.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yoon J.H., Gwak G.Y., Lee H.S., Bronk S.F., Werneburg N.W., Gores G.J. Enhanced epidermal growth factor receptor activation in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. J Hepatol. 2004;41:808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Werneburg N.W., Yoon J.H., Higuchi H., Gores G.J. Bile acids activate EGF receptor via a TGF-alpha-dependent mechanism in human cholangiocyte cell lines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G31–G36. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00536.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marti P., Stein C., Blumer T., Abraham Y., Dill M.T., Pikiolek M., Orsini V., Jurisic G., Megel P., Makowska Z., Agarinis C., Tornillo L., Bouwmeester T., Ruffner H., Bauer A., Parker C.N., Schmelzle T., Terracciano L.M., Heim M.H., Tchorz J.S. YAP promotes proliferation, chemoresistance, and angiogenesis in human cholangiocarcinoma through TEAD transcription factors. Hepatology. 2015;62:1497–1510. doi: 10.1002/hep.27992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sugiura K., Mishima T., Takano S., Yoshitomi H., Furukawa K., Takayashiki T., Kuboki S., Takada M., Miyazaki M., Ohtsuka M. The Expression of Yes-Associated Protein (YAP) maintains putative cancer stemness and is associated with poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:1863–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Toth M., Wehling L., Thiess L., Rose F., Schmitt J., Weiler S.M.E., Sticht C., De La Torre C., Rausch M., Albrecht T., Grabe N., Duwe L., Andersen J.B., Kohler B.C., Springfeld C., Mehrabi A., Kulu Y., Schirmacher P., Roessler S., Goeppert B., Breuhahn K. Co-expression of YAP and TAZ associates with chromosomal instability in human cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1079. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08794-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Michalopoulos G.K., Bhushan B. Liver regeneration: biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:40–55. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Raven A., Lu W.Y., Man T.Y., Ferreira-Gonzalez S., O'Duibhir E., Dwyer B.J., Thomson J.P., Meehan R.R., Bogorad R., Koteliansky V., Kotelevtsev Y., Ffrench-Constant C., Boulter L., Forbes S.J. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature. 2017;547:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature23015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Russell J.O., Lu W.Y., Okabe H., Abrams M., Oertel M., Poddar M., Singh S., Forbes S.J., Monga S.P. Hepatocyte-Specific beta-catenin deletion during severe liver injury provokes cholangiocytes to differentiate into hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2019;69:742–759. doi: 10.1002/hep.30270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Deng X., Zhang X., Li W., Feng R.-X., Li L., Yi G.-R., Zhang X.-N., Yin C., Yu H.-Y., Zhang J.-P., Lu B., Hui L., Xie W.-F. Chronic liver injury induces conversion of biliary epithelial cells into hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:114–122.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]