Abstract

Survivorship after liver transplantation (LT) is a novel concept providing a holistic view of the arduous recovery experienced after transplantation. We explored components of early survivorship including physical, emotional, and psychological challenges to identify intervention targets for improving the recovery process of LT recipients and caregivers. A total of 20 in-person interviews were conducted among adults 3 to 6 months after LT. Trained qualitative research experts conducted interviews, coded, and analyzed transcripts to identify relevant themes and representative quotes. Early survivorship comprises overcoming (1) physical challenges, with the most challenging experiences involving mobility, driving, dietary modifications, and medication adherence, and (2) emotional and psychological challenges, including new health concerns, financial worries, body image/identity struggles, social isolation, dependency issues, and concerns about never returning to normal. Etiology of liver disease informed survivorship experiences including some patients with hepatocellular carcinoma expressing decisional regret or uncertainty in light of their post-LT experiences. Important topics were identified that framed LT recovery including setting expectations about waitlist experiences, hospital recovery, and ongoing medication requirements. Early survivorship after LT within the first 6 months involves a wide array of physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. Patients and caregivers identified what they wish they had known prior to LT and strategies for recovery, which can inform targeted LT survivorship interventions.

The concept of “survivorship” after transplantation has recently been adapted from the cancer literature, allowing for a more holistic view of transplant recovery that goes beyond graft or patient survival.(1,2) Transplant providers may have a limited understanding of patient experiences when perceived through the lens of clinic visits and laboratory values. Understanding challenges after liver transplantation (LT) through a conceptual framework of survivorship allows for an in-depth understanding of patient experiences and may translate to the development of interventions to enhance recovery.(1) To better understand early survivorship experiences, it is essential to understand patient perspectives more fully, especially in the individual’s home environment, where the recovery process predominantly takes place.

It is well established that solid organ transplant recipients experience changes in physical challenges,(3–7) quality of life,(8–11) coping,(12,13) and psychological symptoms(14–20) after transplantation. Medication adherence has been the primary health behavior of interest given its important implications for transplant outcomes.(21–24) Other important concepts related to posttransplant recovery include self-management(25) and self-efficacy as it relates to medication taking and engagement in healthy behaviors.(26–28) These studies provide a foundation for understanding posttransplant recovery; however, apart from enhanced education and informed consent processes, few psychoeducational interventions have been developed to target challenges faced after LT, and none have been endorsed by current transplant guidelines.(29) Moreover, transplant centers continue to diverge in their approaches to addressing post-LT challenges, and there is no systematic process for monitoring and facilitating recovery after transplantation.

To enhance our understanding of posttransplant recovery, we investigated early survivorship experiences using in-depth, in-home interviews. In addition to investigating various dimensions related to the quality of life, we also focused on what patients and caregivers wish they had known prior to embarking on the transplant journey to identify potential targets for future survivorship interventions. Building on previous qualitative work,(30) we conducted in-home interviews that focused on physical, emotional, and psychological challenges experienced by LT recipients and caregivers during the recovery period of 3 to 6 months. Unique to this study was the special attention paid to recovery in the home environment and what tools or coping strategies may improve survivorship. Through this comprehensive investigation of early survivorship experiences, our aim was to inform a novel conceptual model of survivorship after LT(1) and to generate evidence to directly inform future LT interventions.

Patients and Methods

POPULATION

Individuals undergoing LT from December 2018 through November 2019 at the University of North Carolina (UNC) were enrolled consecutively as previously described.(1) Included were English-speaking adult (≥18 years of age) LT recipients between 3 and 6 months after transplant. We chose the recovery period of 3 to 6 months given that, during this time, coping skills and resilience are often tested, and unanticipated challenges may arise. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation recipients were eligible to participate. At the discretion of the LT recipients, caregivers participated in the interviews, which primarily took place in patients’ homes. All patients provided written informed consent and received a $40 gift card for their participation. This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board and followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist for qualitative studies (Supporting Table 1).(31)

IN-PERSON INTERVIEWS

Qualitative methods for conducting our in-person interviews and data analysis are described in more detail elsewhere.(1) Briefly, we followed a semistructured interview guide developed as part of a narrative research paradigm to elicit stories and descriptive details about the physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and psychological challenges experienced after LT and ways of coping with these challenges. These broad categories were based on the multiple dimensions of quality of life that have been described in posttransplant experiences(30) but explored through the lens of survivorship. In addition, we explored what LT recipients and caregivers wish they had known or what resources they wish they could have had during the recovery process to enhance their survival. Findings specific to what survivorship means to LT recipients and motivations to survive are reported elsewhere.(1) Included in the interviews was a tour of the home, during which participants were invited to show the interviewers the rooms where they recovered, tools used for recovery (eg, medication lists/binders, pillboxes, equipment), and any other important aspects of their recovery process (eg, pets, pictures of family).

Results

SAMPLE SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 20 in-person interviews were conducted between May 2019 and February 2020. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The median age of the LT recipients was 61 years (range, 28–68). More than one-third (35%) were women, and most (60%) were White. Patients lived on average 76 miles (range, 14–270) from the transplant center.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants (n = 20)

| Identification Number* | Age, Years | Sex | Race | Education Level | Interview Location | Caregiver Present | LT lndication† | Kidney Transplant | Native MELD Score at LT | Waitlist Time, Months | Distance to LT Center, Miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 | 60 | Male | White | Some college | Home | Yes | NAFLD | No | 27 | 10.1 | 73 |

| 2 | 50 | Female | Black | College graduate | Home | No | AIH/PBC/PSC | No | 28 | 22.5 | 93 |

| 3 | 55 | Male | White | High school graduate | Home | Yes | Alcohol | No | 27 | 0.76 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 65 | Male | White | High school graduate | Home | Yes | Viral Hepatitis/NAFLD | No | 17 | 12.1 | 14 |

| 5 | 66 | Male | White | College graduate | Home | Yes | NAFLD | Yes | 28 | 2.4 | 104 |

| 6 | 64 | Male | White | High school graduate | Home | No | Viral Hepatitis/HCC | No | 14 | 10.1 | 18 |

| 7 | 62 | Female | Black | High school graduate | Clinic | Yes | AIH/PBC/PSC | No | 36 | 1.8 | 85 |

| 8 | 58 | Female | White | College graduate | Home | Yes | NAFLD | Yes | 21 | 7.9 | 22 |

| 9 | 68 | Female | White | Some college | UNC temporary residence | Yes | Cryptogenic | No | 26 | 42.4 | 270 |

| 10 | 68 | Male | White | Some college | Clinic | No | NAFLD/HCC | No | 28 | 9.8 | 65 |

| 11 | 66 | Male | White | Graduate school | Home | No | Viral Hepatitis/HCC | No | 28 | 7.7 | 21 |

| 12 | 42 | Female | Other | Some college | Home | No | NAFLD | No | 32 | 3.7 | 129 |

| 13 | 68 | Male | White | College graduate | Home | Yes | NAFLD/HCC | No | 40 | 4.5 | 76 |

| 14 | 66 | Male | White | High school graduate | Home | Yes | NAFLD/HCC | No | 19 | 8.8 | 140 |

| 15 | 55 | Female | White | Some college | Home | Yes | Viral Hepatitis/HCC | No | 28 | 82.4 | 25 |

| 16 | 28 | Male | Black | College graduate | Home | No | AIH/PBC/PSC | No | 24 | 42.8 | 101 |

| 17 | 63 | Male | White | High school graduate | Home | Yes | NAFLD | No | 23 | 1.7 | 75 |

| 18 | 54 | Male | Other | High school graduate | Clinic | Yes | Viral Hepatitis/HCC | No | 8 | 6.8 | 100 |

| 19 | 52 | Female | Black | Some college | Home | Yes | AIH/PBC/PSC | Yes | 21 | 51.6 | 84 |

| 20 | 47 | Male | White | Some high school | Home | Yes | Alcohol | No | 21 | 4.1 | 49 |

To protect the identity of interview participants, identification numbers were reassigned such that they do not reflect the chronological order of transplants at UNC.

To protect the identity of interview participants, indications for LT were listed using broader categories such as viral hepatitis (HBV, HCV) and autoimmune/cholestatic liver diseases (AIH, PBC, PSC).

PHYSICAL CHALLENGES AND BARRIERS TO HEALTHY BEHAVIORS AFTER LT

LT recipients and caregivers identified the following physical challenges in their early survivorship: (1) physical debility, (2) appetite issues/dietary restrictions, (3) medication taking, and (4) new medical problems (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

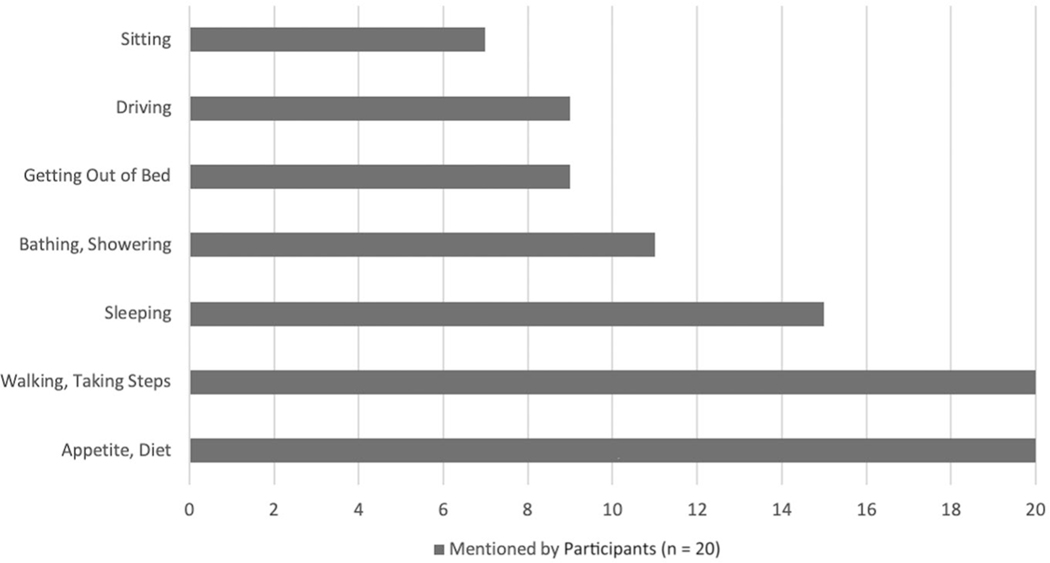

FIG. 1.

Type and frequency of physical challenges identified by LT recipients during in-home interviews at 3 to 6 months after LT (n = 20). The most commonly encountered challenges included physical challenges such as walking/standing as well as issues related to appetite and diet (eg, food preparation, safety).

TABLE 2.

Physical Challenges Experienced After LT: Home Interviews With LT Recipients 3 to 6 Months After Transplant (n = 20)

| Category | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1. Sitting/standing/walking | “I was scared to walk, in the beginning. I was very nervous ... I was scared I was gonna fall. I couldnť feel any strength in my legs” (patient 2) “I would get up and walk, but after a while, my legs were starting to give out and the last time I walked down there and I fell over on the mailbox, and a lady come along ... helped me out and brought me here. But that was the last time I walked” (patient 1) “I couldnť move. I couldnť do anything for myself, too, and having to rely on her or somebody there to do it for me, it wasnť me” (patient 20) |

| 2. Bathing/showering | “The first 90 days, iťs pretty much just getting your body built back up just enough to do the basics, you know. Like, making sure you can get to your showers, and to the little everyday things, you know” (patient 6) “I love hot baths. They wonť let me take a hot bath. I had to take a shower, but I canť get in the tub and soak like I normally do. ‘Cause I had a bag on this side. I had the PICC line in my arm. So, I had to wrap up my arm and wrap up my bag, and get in the shower. But I couldnť sit down in my hot tub and soak” (patient 2) |

| 3. Sleeping/mobilizing from bed | “It was pretty intense. You know you just, just moving, trying to sleep. I’ve always been a side sleeper and you’re going to have to get used to just laying on your back sleeping like that, which I didnť sleep good at all for how long, until those staples come out” (patient 18) “I was waking up in the middle of the night, and I had to sit up and just watch TV ‘cause I couldnť sleep or read” (patient 2) “Well it was just painful to get out of bed. Once I learned how to maneuver myself in the right direction it was better ... as long as I tried to use my stomach it would hurt. There still, if I move wrong, I still feel it” (patient 10) |

| 4. Driving • Being in passenger seat • Limited driving privileges |

“Just when you hit a bump [when you are riding or driving in a car] ... hit a big bump you would hurt” (patient 10) “We donť let her drive. I donť care if iťs going to [quick]. She’s not driving over there. I donť care ... if she needs to go somewhere [we take her] but other than that no, [we] donť let her drive” (patient 19’s caregiver) |

| 5. Dietary • Appetite changes • Food restrictions/safety • Food preparation |

“That appetite ... I can fix something and think I want it and I eat a little bit of it and it just donť taste right” (patient 7) “We had to get the menu from a nutritionist of what we could buy over the counter to eat. ‘Cause we didnť know how to puree food or anything” (patient 2) “I try to cook but I canť stand so long and sit for so long, you know stand up until I get tired” (patient 7). “Even after you’ve cooked it if you put it in the refrigerator it can only stay but a couple of days before it has to be throwed away. And it canť stay just 2 or 3 days and not 3 or 4 days before you have to freeze it or you throw it away” (patient 10) “It was reinforcing food safety things ... like washing all fruits and vegetables very carefully, and rubbing them, and stuff and making sure everything’s well done. Washing the tops of cans” (patient 1 ‘s caregiver) |

| 6. Medication taking | “Oh my god. I had to take so many pills the first month. It was like 15 at 9:00, 15 at 12:00, at 3:00, and another maybe 12 at 9:00. You couldnť miss a dose” (patient 2) “When you first start, iťs overwhelming ... But when you’re not really used to doing that ... you take the card and get it, and then you take a pillbox—I make it up for a week. But it was a little overwhelming, ‘cause my mind’s, like, a little foggy, you know. And I was having to do it, and then I was having to recheck behind myself, to make sure ... ‘Cause a couple times, I made it up wrong, and then I went back and I caught it, and then I had to rechange it” (patient 6) |

| 7. New medical issues after LT • Frequent clinic/laboratory visits • Medical problems (eg, dialysis, diabetes) • Rehospitalizations |

“You know sometimes when you have surgery you think, ‘Well when I have surgery this is iť ... but I donť think she realized all that she had to go through with the dialysis and all of that” (patient 2’s caregiver) “Another thing that I donť think we expected is the frequency of blood work that he had to do ... he was having to do bloodwork 3 times a week” (patient 18’s caregiver) “Well, they cause elevated blood sugars, or elevated blood pressures, or this and that, so now you’re on diabetic medicine, and you’re on cholesterol medicine, and you’re on blood pressure medicine, things that you may didnť have before” (patient 1 ‘s caregiver) “I had to go back a couple of times. Yeah. I had spent—I think one was for a week and then another one was for 10 days. Just I had some fluid that wasnť going anywhere. I blew up like a balloon and they had to control that” (patient 3) |

Physical Debility

A majority of individuals described physical debility including an overwhelming decrease in strength and energy after LT. Participants described issues of pain, as well as extreme fatigue, easily becoming short of breath with the slightest physical movement, and being unable to bend or twist: “When I first came home, I was as weak as a newborn puppy … it took every ounce of strength I had to get up those steps” (patient 5).

The following most basic activities of daily living were extremely challenging: walking, taking steps, mobilizing to and from bed, sleeping, mobilizing from a car, sitting in the passenger seat, and bathing (Table 2, sections 1–4). Other challenging activities included getting dressed, playing with children or grandchildren, doing housework, or enjoying hobbies such as gardening or working on vehicles.

Appetite/Diet Changes

Another substantial physical challenge identified by LT recipients involved changes in appetite and dietary restrictions after LT (Table 2, section 5). Individuals experienced a lack of appetite early during recovery, including a change in what foods/beverages they wanted to consume. Interestingly, others reported the opposite issue and felt increased hunger, especially as the recovery period unfolded and their strength increased.

It was physically challenging for individuals to make and cook their own meals as they were accustomed to doing before transplant. They indicated that pain and lower stamina impaired their ability to prepare food properly. Adapting to and learning new ways to prepare their food (eg, pureed, avoiding potassium) was also challenging.

The numerous food restrictions faced after LT (eg, avoidance of grapefruit, undercooked meat, buffet foods) were viewed as monumental challenges for participants compared with their pretransplant eating habits: “Well I don’t really know what to eat. I can’t eat this. I can’t eat that” (patient 7). Food safety became a looming concern after transplant. In some cases, practicing food safety guidelines meant limiting eating away from home and avoiding restaurants that included buffets. However, food safety was also relevant to how food needed to be prepared at homes and new lifestyle habits that needed to be maintained (eg, washing fruits/vegetables, cooking meat thoroughly, avoiding leftovers).

Medication Taking

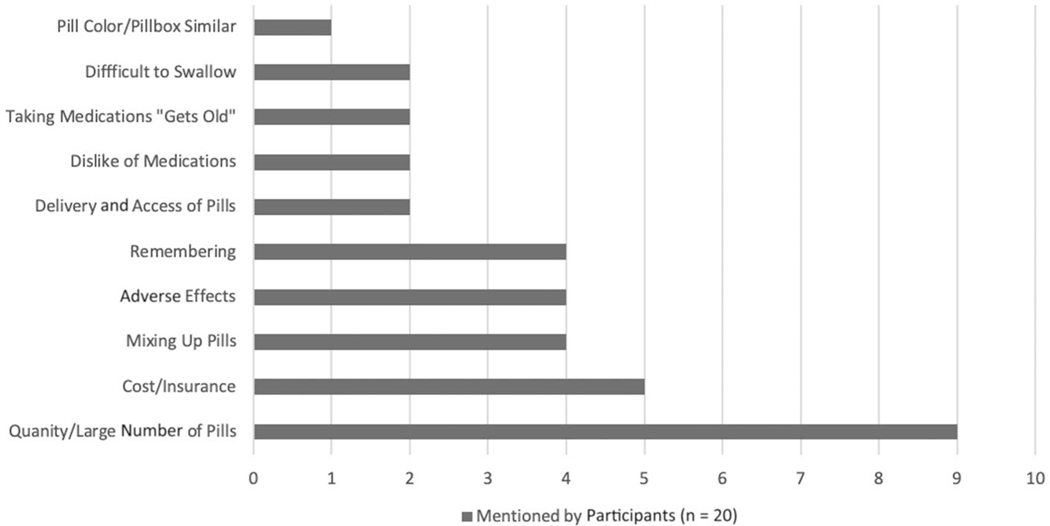

The main challenges related to medications included the large quantity of pills taken on a daily basis, the cost of medications, and concerns about insurance coverage (Fig. 2). Other key challenges were remembering to take medications at the correct time, dealing with adverse effects, and the fear of mixing up different pills (Table 2, section 6). Some individuals observed personality or mood changes that they attributed to medications (ie, immunosuppression) with which they needed to cope.

Fig. 2.

Type and frequency of challenges identified regarding taking medication (n = 20). The most commonly faced issue pertained to the number and frequency of pills taken daily. This was overwhelming to both LT recipients and caregivers, who also expressed concern about preparing this number of medications for their loved ones to take.

Participants discussed cognitive motivations and behavioral strategies to assist with remembering to take their medicines correctly (Table 3). The following 3 main reasons to take medications included: (1) to stay healthy, (2) to honor the gift of life received through a LT, (3) and “to do what needs to get done.” All participants used a pillbox or medicine case to help with medication management; however, this was only 1 of multiple strategies used. Patients reported it was more effective to use a combination of strategies for medication adherence, including the use of a medication card/list, travel bags with extra medications, phone alarms, and caregiver reminders. “Being consistent with routines” (patient 17) (ie, routinized behaviors) was most helpful in facilitating medication adherence. Most of the patients described a weekly ritual of filling pillboxes and checking pill counts. On the tour of homes, it was commonly observed that patients had medications stored in 1 area of the house where they or a caregiver would routinely fill pillboxes.

TABLE 3.

Key Motivations and Strategies for Taking Medications After LT (n = 20)

| Motivations for Taking Medications | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| I. To live/stay healthy | |

| “I want my life back; you know I want to get back to like it was before. I want to work. I want to go fishing. I want to get out there ... just get back to normal” (patient 18) | |

| “But I donť want to go without [my medications], because I know I could reject my liver. And why go through what all’s been done from the surgery on, to just throw it all away? That would be stupid ... I shouldnť have had the transplant if I was gonna be like that. I didnť deserve it if I’m not gonna try to do what I need to do to stay healthy and live" (patient 15) | |

| II. To appreciate the gift of receiving a LT | |

| “I think that if I was blessed enough to be able to get a liver that some other person gave to me, I feel like I’m just very, very grateful. And I feel that it is gonna be a real good one for me. I have full intentions of living to be 90, so, I donť think any other way, and I donť choose to" (patient 9) | |

| “Iťs a gift that someone’s given to you, and they’re losing someone in the process of it, so you’ve got to take care of it ... It takes special people to do special things. I’m grateful for her family, and whoever she is, gave me the opportunity to live longer (patient 19) | |

| III. To do what needs to get done: | |

| “Because I had to take [the meds] ... the 1 pill is for the lining of my stomach, so if I donť want to throw up or be back in the hospital, guess what I’m going to do? I’m going to take it” (patient 19) | |

| Strategy for medication taking | Illustrative quotes |

|

| |

| Pillbox medicine case | “They gave us a pillbox; iťs, like, iťs slots, you know, morning-evening pill, morning-evening, noon, if I have to take it. And now there’s one that I got that I’m gonna have to take 3 times a day, so, I’m gonna finally fill the noon slot" (patient 9) |

| “Have a system, because you imagine if you’ve got 12 medications sitting here in front of you and you’re taking them at different frequencies and iťs kind of hard to keep up ... our system was when we first began, we did 1 pill tray. So, I did 1 pilltray“ (patient 18) | |

| Medication list, medication cards, and medication sheet | “We have our med sheet that we—our bible med that we have to keep ... so that when you take it and put [the pills] in, iťs all [there]” (patient 14) “There’s some sort of routine for filling—refilling—the pillbox ... I actually do it, ‘cause it goes through Saturday. And usually Saturday evening I’ll sit down and go through and do the whole week ... yeah, I’ll get out my orange card I got, just to make sure I’ve got everything right, and just start filling it up" (patient 15) |

| Caregiver support and assistance | “I’m his medicine person. I make sure his phone rings at 9 am and 9 pm. Iťs an alarm so that he will be able to get his medication on time. Try to makes sure he eats like he’s supposed to" (patient 17’s caregiver) |

| “He’s [caregiver] like my alarm clock, ‘Uh, iťs 9:00. You take your medicine? Iťs 9:00. You take your medicine?’" (patient 12) | |

| Medication travel/to-go bag | “I actually put the pillbox in my bookbag if I know I’m going out somewhere. I have medicine on me all the time, and I make sure iťs by me. When I hear it go off, thaťs when I’m like, okay. Iťs about that time. I need to go get my medicine" (patient 16) |

| “My oldest daughter, if she donť see my pillbox close by, or we get in the car, she says where is your medicine, where is your medication or card? And I have to go back in the house and get it" (patient 19) | |

| Setting phone alarms | “My phone I actually have 9:00—9:00 am and 9:00 pm—alarms on it, so they go off to remind me to take ‘em ... yeah, that way I donť miss ‘em. And then it gets loud if I donť get it pretty quick” (patient 15) |

| “They set my phone .... That phone hasnť left my side ever since I got out of the hospital ... iťs always, iťs been in a pocket. | |

| And if I happen to forget it well, not good. So that phone is—I mean I hate to do it but iťs got to be on my person at all times” (patient 8) | |

| Count pills every time | “They gave me this little medicine case to make sure you have every medicine in there. I had to count every time I take them to make sure. It was a lot” (patient 2) |

Health Problems After LT

Multiple clinic appointments and other procedures, including frequent laboratory draws or dialysis, were experienced after LT. This required additional travel, contributing to additional burdens of transportation, financial stressors, and caregiver dependency. Some also faced complications or new health conditions from their transplant, including collapsed lungs, new-onset diabetes, fluid overload, and drainage issues (Table 2, section 7).

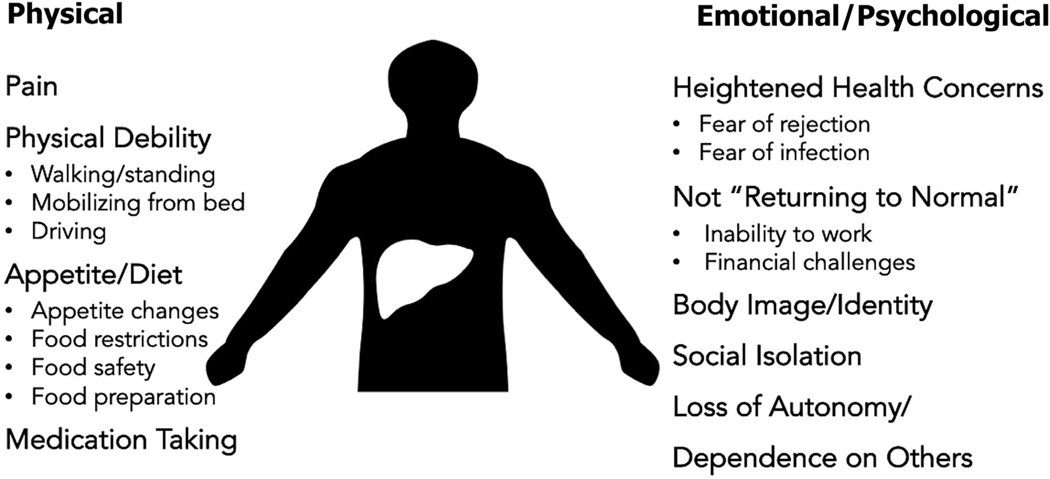

EMOTIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL CHALLENGES AFTER LT

In addition to the physical challenges encountered during the transplant recovery, participants and caregivers identified emotional and psychological challenges (Fig. 3). The following several themes were identified: (1) LT is an “emotional roller coaster,” (2) new health-related anxiety including fear of rejection, (3) fear of never “returning to normal,” (4) financial concerns, (5) body image and self-identity issues, (6) social isolation, and (7) loss of autonomy/dependence on others (Supporting Table 2). Not returning to normal, loss of autonomy, and dependence on others had negative implications for role identity (eg, no longer being the “breadwinner” at home). For some individuals, including those who received LTs for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), we explored whether LT was the right decision for them and the tradeoffs they encountered.

Fig. 3.

Various themes were identified regarding early survivorship experiences including physical, emotional, and psychological challenges experienced 3 to 6 months after LT. For physical challenges, individuals coped with (1) pain, (2) physical debility, (3) appetite/diet, and (4) medication taking. Among the emotional/psychological challenges, LT recipients faced (1) new health-related concerns, (2) fears about not “returning to normal,” (3) body image and self-identity issues, (4) social isolation, and (5) loss of autonomy/dependance on others. These challenges had important implications for role identity (ie, how individuals saw themselves after LT, including as a survivor, breadwinner, and so forth). Image adapted from Alexander Skowalsky. CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/.

LT Is an “Emotional Rollercoaster”

The experience of waiting for, receiving, and recovering from LT was described as an “emotional rollercoaster” (Supporting Table 2, section 1). During recovery, LT recipients felt heightened and unexpected waves of emotion, sometimes being overwhelmed with emotion for no apparent reason or being unable to control their emotions in the moment. Likewise, caregivers spoke of personality changes in their loved ones and a sense that they were more emotional— either positively (eg, grateful, humbled) or negatively (eg, angry, irritated, mean).

Heightened Health Concerns

Sources of concern and stress included health-related fears (Supporting Table 2, section 2). Individuals conveyed a general worry about the unpredictability of recovery during the first year and the feelings of apprehension and anxiety about what might happen to their new liver. There was worry about other health conditions or complications arising from receiving a new liver (eg, the body rejecting the new organ). Many expressed how strong and stable they felt when they were initially discharged from the hospital after the surgery, only to have a health problem arise at home that resulted in rehospitalization. This experience could be demoralizing, leading to setbacks not only in one’s physical recovery but also emotional recovery. Others relayed concerns that the LT had severely weakened their immune system, making them more vulnerable to contracting infections from others.

Fear of Not “Returning to Normal”

A main source of worry and concern was not knowing if they would be able to return to a “normal” life in which they could return to work or be as physically active as they were prior to LT (Supporting Table 2, section 3). Worries about losing job skills and being able to resume the same stressful and demanding roles were prevalent. Being away from their jobs reinforced the isolation they felt while sitting at home. Regarding return to employment, differences in responses were seen based on sex. When discussing challenges related to returning to work, male participants specifically commented on their physical limitations (eg, decreased strength, endurance, weight restrictions) as being the main barrier to return to employment. Female participants remarked on infectious risks given their immunocompromised state as the main barrier to returning to work. Motivations for male participants to return to work included escaping the feelings of social isolation and “uselessness” of sitting at home as well as providing more financially for their family. In addition, they invoked principles of “work ethic” (ie, working from a young age or always having been the breadwinner) as motivations to return to work. All participants viewed returning to work as an important indicator of “returning to normal.” Although many participants described plans to go back to work eventually, once they were physically stronger or their immunity was less compromised, others saw LT as a natural transition to early retirement or disability.

Financial Concerns

In light of concerns about not being able to go back to work, patients expressed fear about the financial burden of covering medical costs and other bills with no income being generated (Supporting Table 2, section 4): “Financially, it’s been real hard on us … that’s the hardest, for us, because we’re on social security … how much you get is how much you get … we’ll be paying till we die” (patient 9).

Body Image and Identity Issues

Several participants showed their surgical scars and described them as a “badge of honor.” Others said it frightened family and friends to see their scars. One participant expressed extreme sadness and grief about what her body looked like after transplant and whether her husband would become more detached and less affectionate because of her scar (Supporting Table 2, section 5). Others were grappling with the idea of having someone else’s organ in them and what that meant in terms of their new post-LT identity. Integral to this was the mixed emotions that came with knowing someone had to die in order for them to live. Although grateful, a great deal of sadness, guilt, and feelings of heavy obligation and responsibility were also expressed. Participants described feeling connected or “very close” to the donors despite never meeting them.

Social Isolation

Participants discussed dealing with prolonged episodes of being down or depressed secondary to home confinement and social isolation, restriction of visitors, and dependence on others to care for some of their most basic daily needs (Supporting Table 2, section 6). Compounding the feeling of isolation was the perceived need to restrict visitors in light of a compromised immune system.

Just being confined to the bed, the house, you know just— it’s physical but it’s about as bad mentally too. You know for somebody like me … [to] just look at TV, look at the walls … you can’t see nobody because you know there’s that risk of infection and so you’re pretty much isolated. It’s just mentally it’s tough. (patient 18)

Loss of Autonomy/Dependence on Others

In conjunction with being homebound, relying on a caregiver and others for help was a psychologically difficult part of the recovery process (Supporting Table 2, section 7).

It will get you down, you get discouraged. You hate to call your wife or your son or somebody, whoever is with you, to come in and help you put your socks on, and put your shoes on, tie your shoes, maybe help you get dressed. I mean, the things you used to do all along, you can’t— your hands are tied. (patient 14)

Feeling helpless would sometimes bring on bouts of sadness and frustration. There was also concern for creating a burden of dependency on their loved ones. This fostered frustration and resentment at times and added stress to relationships with caregivers. They expressed embarrassment about asking for help with mundane tasks such as using the shower or bathroom. Some had their driving privileges revoked by caregivers, further exacerbating their feelings of autonomy and self-control. Despite these negative feelings and struggles with changing role identities, most recognized that they had to rely on other people to recover. Caregivers were often observed reminding patients about what they could and could not do and were important sources of external motivation to practice patience with the small steps of their physical and mental recovery.

Tradeoffs: Was LT the Right Choice?

For some LT recipients, especially those who received LTs for HCC, there was some doubt about whether pursuing LT was the right choice.

So, it was a difficult decision for me, ‘cause I’m feeling fine and there’s nothing wrong with my liver, except for they see these spots … I had been going back and forth, all through this process, “Do I really wanna do this?” Cause again, you know, I was strong, I felt fine, so it’s a statistical thing … I’ll never know what the benefit is. I’ll never know if I would’ve died from the cancer. It’s a crapshoot. (patient 11)

Others expressed that if their cancer had been stable, then perhaps LT may not have been worth it or could have been better used in another recipient: “If it’s not gonna progress for me more, then why would I wanna take a liver that could’ve [gone to] somebody else that was going to benefit more” (patient 6). There was also a sense of mourning or loss expressed by a few participants who acknowledged that there were now specific activities they would never be able to enjoy or accomplish (eg, exotic foreign travel).

“WHAT I WISH I HAD KNOWN”

Table 4 illustrates key themes related to what LT recipients and caregivers wish they had known prior to LT. Part of this conversation included eliciting what they might tell a patient preparing for LT and tips to enhance early survivorship based on their own personal experiences. Overall, they recommended more frequent teaching/orientations at different time intervals before and after LT. Most important was managing expectations, including depicting waitlist and recovery experiences in as honest and clear terms as possible.

TABLE 4.

“What I Wish I Had Known Before Undergoing a Liver Transplantation”: Illustrative Quotes Highlighting Advice LT Recipients Would Give to Future LT Candidates (n = 20)

| Category | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Waitlist experiences • Time spent waiting for an organ can be very long (and short in the setting of HCC) • False alarms (le, being called for offers that did not come to fruition) |

“I had to wait a couple of years. I had to go up the list with my MELD score ... there wasnť really anything I could do because I was taking my medicine and ... It was just one of those things that If my MELD score was high enough, it was a good thing. But at the same time, It was bad on me because it meant something was going on with my health. But If it was low, it means I was doing good ... but It didnť help for my liver transplant. So, it was one of those wln-win lose-lose situation” (patient 16) “It was discouraging. It was very discouraging. At one point, I just wanted to just take my name off the list ‘cause I felt like it was never gonna happen. I think we went 3 times. One time was the middle of the night... It was pouring rain. I was like, this has got to happen” (patient 2) “One time that I was getting kind of worried that I would never get one. So, when It actually came, I was so scared. You have all these negative thoughts in your head that you’re not gonna make It, it was not gonna fit you, and all that stuff. Thaťs what I went through before I had the surgery” (patient 2) "Whatever your MELD score is, they automatically jump you up to like 28 or something like that. And thaťs usually the transplant time. And I actually got my transplant points right at the beginning of November, and before the end of January I was transplanted” (patient 15) |

| Hospital stay • Expectations for intensive care unit care (eg, potential lines, endotracheal tube) • Resources for caregivers (eg, parking, where to stay) |

“I didnť really know howto expect the surgery you know. I mean I knew what the outcome was... I donť know I wasnť expecting it to go through all of what I went through after surgery ... You know all of the tubes and things hooked up to you and all these X-rays and all, had to do the same thing over after the transplant" (patient 7) “No one prepared me for what life was gonna be ... I mean I knew I was gonna go in Intensive care. But I didnť know that when I went in there when I woke up I had tubes down my throat... I couldnť talk... I felt paralyzed. I couldnť move my legs I couldnť move my arms and It was a scary feeling ... It was a shock" (patient 13) “Parking—people need to know about parking when they come up here too. I didnť realize that you could park down the street for $10.00 a week, you know versus $10.00 a day out here ... thaťs $70.00 a week, you know thaťs a lot of money ... Yeah I was stressing I’m like, ‘Oh my God I’m parked outside, whaťs it going to cost me?’... Nobody never talked to me about... ‘Are you able to afford the parking’ or tell me about the parking resources" (patient 18’s caregiver) |

| Realities of physical recovery: It is a process • Temper expectations: getting back to a new "normal" will take time • Caregivers should expect this process to take time |

“It would be good if somebody said, Ľook, this Is going to be hard. This is going to hurt, iťs going to be real slow. And now like you’re in your 50s. You’re not going to zing back like you did when you were in your 20s’... what Iťs going to be like In the real world" (patient 8’s caregiver). “It was something that kind of caught me off guard ... Iťs just that I hated the length and the timeframe that It took ‘cause I was ready to get back to having everything back to normal. So, iťs something definitely that people need to know about because it Is a little process. They explained It as a process, but you donť actually know how It is until you actually start going through it" (patient 16) “Iťs a very slow healing process... Iťs very slow. I think with a caregiver thaťs something that they need to know and understand ... They told me I would be out of work for about you know 2 months... because when he went home he became how can I say this, I think he started feeling a little bit Insecure. I hope you wonť kill me after saying this, but he wanted me in his eyesight all the time" (patient 18’s caregiver) |

| Physical fitness prior to LT matters | “But if I could tell anybody anything you know if they’re able to get out and exercise you know and just try and get their self In the best shape possible before they go through this they’ll be a whole better off" (patient 18) “I wish that I had known that the exercises that I should have done prior—[they] would be so beneficial in my recovery. So thaťs why I press myself now" (patient 4) |

| Plan for time-intensive follow-ups • Be prepared for visits that can take a lot of time, coordination, and require travel |

“Once you’re discharged you got to come back for an appointment. Try to come and stay in a hotel... if you’re coming a long distance because little bumps In the road which we donť pay attention to now -You feel every one of them ... If you try and do it there and back In a day you’re going to be one miserable feeling person ... you’re going to feel bad, hurt and just wish you hadnť even of come" (patient 18) “Donť just tell someone you can be drawing blood frequently, let them know, ‘Hey this could be 3 times a week for 2 months’... one of those days he had to drive you know had to go 45 minutes away to do lab work" (patient 18’s caregiver) |

| Prepare for unexpected medical complications • Surgical, renal, glucose |

“Other people need to know there may be hospitalizations even after the transplant, so be prepared" (patient 18) “I didnť have any Idea all this was gonna happen. And I didnť have any idea prior to surgery that my kidneys would act up and I may need to have a kidney transplant. That was told to me after the fact and I donť know that It would do any good but It sure canť do any harm I donť think" (patient 13) |

| Medication taking Is overwhelming | “I thought I would have to take maybe I or 2 pills a day. But not that much ... 9 am, 3 pm, every day. I didnť know It was gonna be that much" (patient 2) “I thought for sure I would come home and take less medicine. Actually, I was taking more medicine when I came home. I still am ... but she explained It... now that I know what each pill means... iťs helping different categories of my body" (patient 1) “You’re looking at the medicine and you’re looking at this pill bottle and you’re like, ‘Oh my God.’ My first thought in my mind I didnť—I donť know If I told my husband or not, but my first In my mind, ‘Oh my God I’m going to be the one thaťs going to kill my husband,’ [laughs] because I know I’m going to jack this up ... so when you get those medicines it can be overwhelming" (patient 18’s caregiver) |

| Orientation may not stick • Refresher training sessions, mentors |

“Once you go through all that training, they give you material which Is a good thing, but you know ... a year later you’re getting transplanted how much did you retain? ... so yeah there needs to be some maybe every 3 months... a refresher I think would help ... because there’s a lot of stuff that I donť remember" (patient 18’s caregiver) “When they’re doing their training ... it would be nice If they could bring someone in and let someone thaťs been through this talk to get their point of view ... and the person also needs to say, ‘What happened to this person may not happen with you.’ So we do understand that every situation is different" (patient 18’s caregiver) |

Everybody had said it was going to get better. You know, after the transplant it will be better. And then here this happens … and you’re going to feel so much better. And then it’s not … but maybe setting expectations a little bit in terms of this is not a cure for your liver disease … that there might be some other hurdles down the road is important for you to hear before you go through. (patient 17’s caregiver)

Discussion

Early survivorship experiences for LT recipients and caregivers include a wide array of physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. This qualitative study featured in-depth home interviews of LT recipients and their caregivers, offering a unique perspective on LT survivorship and actionable items to improve the recovery process. The most challenging physical experiences related to mobility, dietary modifications, and medication taking. LT recipients grappled with the rollercoaster of new health concerns, body image and identity struggles, social isolation, dependency issues, and worries about never returning to normal— both physically and emotionally. These findings have important implications for survivorship, including how individuals perceive their post-LT identity and expectations for managing their LT long term. In describing “what they wish they had known,” LT recipients and caregivers offered insight into potential interventions, including enhanced educational resources and support mechanisms, to assist with transplant recovery that should be examined in future research studies.

Survivorship after LT is a novel concept proposed to frame our understanding of the arduous recovery endured by transplant recipients and caregivers.(1,2) This study generated data guided by a conceptual model of survivorship as well as provided a deeper understanding of posttransplant recovery. The survivorship framework, adapted from the cancer literature, naturally lends itself to a multidisciplinary approach in which actionable items are targeted to enhance survival. Although most transplant recipients and providers consider LT to be a “gift of life,” it is important to recognize that LT requires physical, emotional, and psychological recoveries that pose evolving challenges at different stages of recovery.(30) This concept was further elucidated by a French study in which LT was described as not only a recovery but also a new chronic illness.(32) Although quality of life has been shown to improve after LT,(11,33,34) despite initial impairments in physical and cognitive functions,(14) more than half of solid organ transplant recipients experience increased symptoms of anxiety or depression(18,20) and posttraumatic stress.(35) About one-quarter of individuals have persistent symptoms of anxiety or depression that are associated with impaired quality of life and medication nonadherence(18) as well as increased mortality.(20) These experiences may be related to adverse effects from immunosuppressive medications, pretransplant mental health issues, poor coping strategies, or a feeling of less personal control over one’s health.(18) They are also likely exacerbated by the physical, emotional, and psychological challenges experienced after LT as described in this study. Similar to what has been reported previously, we found that feelings of guilt and indebtedness to the organ donor can provide additional stress to LT recipients; this has important implications for graft outcomes, including worse immunosuppressant adherence.(36)

Although the focus on quality of life and psychological symptoms after transplant is vital to understanding patient experiences, this study delved deeper into other survivorship experiences and the interplay between physical, emotional, and psychological challenges experienced 3 to 6 months after LT. Previous studies of post-LT recovery have not investigated these experiences in the home environment or have been limited by their use of survey methodology, which cannot solicit data on unanticipated challenges. Only 1 other study has been conducted using in-home interviews among solid organ transplant recipients to investigate daily self-management strategies to engage in physical activities and take medications.(25) A survivorship framework offers a way to investigate the interplay between physical, emotional, and psychological recoveries after LT with a focus on the development of interventions and tools that may improve this recovery process. Unique to our study was the focus on what LT recipients and caregivers wish they had known or resources they wish they could have accessed throughout the LT process (Table 4). Traveling to and being in individuals’ homes also shed light on the important role sociodemographic and geographical factors play in a survivorship conceptual model for LT and potential health disparities experienced by this population.(37,38)

Results from this study generate potential ideas for survivorship strategies to enhance post-LT care (Table 5). Overall, transplant programs likely need to improve setting realistic expectations and providing a truly balanced perspective of challenges that may arise before and after LT. This includes describing and planning for a full range of experiences, rather than the average, so that individuals are better prepared mentally for unanticipated challenges. It is imperative to set expectations about potentially not getting back to “normal”; individuals may have to adapt to a “new normal,” which could have important implications for functioning, work, and role identity. In addition to describing death or short-term surgical complications, outcomes should be framed in terms of debility and negative implications for role identity (ie, returning to work or switching skill sets). In-depth education (using audiovisual materials) should be provided at different time points surrounding LT (eg, on the waiting list, acute in-hospital recovery, transitioning home), recognizing that needs will evolve over time. Activities to combat social isolation and provide more psychological and emotional support could include facilitating more telehealth interactions with the transplant team and developing robust “mentorship” programs or support groups for LT recipients and caregivers (eg, matching individuals with others who have already gone through the recovery process). In addition, practicing and ingraining certain ritualized behaviors prior to LT (eg, food preparation/safety, pillbox use) can build self-efficacy that lasts after LT.

Table 5.

potential strategies and interventions to Foster early survivorship after lt

| Challenge | Strategy/Intervention |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Waitlist experiences | • Deliver enhanced education including: a Orientation plus educational refreshers at multiple time points b Audiovisual learning targeting various levels of health literacy c Set expectations regarding range of waitlist experiences • Establish peer mentorship from other LT recipients with similar indications for LT • Practice ritualized behaviors including dietary modifications while on the waiting list |

| Physical recovery | • Offer detailed descriptions of acute postoperative experiences • Provide sample schedules for planned clinic visits, laboratory draws, and hospitalizations during the first year after LT • Create a physical therapy plan including goal setting and strategies for physical activity re-engagement |

| Medication taking | • Use electronic medication card lists • Promote early use of pillboxes and medication monitoring while on the waiting list • Leverage phone reminders/app technology to increase adherence |

| Emotional/psychological | • Set expectations about getting back to a new "normal" (eg, lifelong medications) |

| Recovery | • Combat social isolation with scheduled check-ins after LT • Create LT recipient and caregiver support groups |

| Financial | • Provide more robust prefinancial and postfinancial counseling • Promote fundraising to address unanticipated challenges with finances related to LT • Offer caregiver resources (subsidized housing, parking, food) before and after LT |

| Coordination of care | • Outline care team (eg, transplant hepatologist, surgeon, coordinator) and primary care doctor • Create a survivorship plan including primary support individuals/networks, goal setting for returning to work, and goal setting for autonomous return to function with daily activities |

Although our study population was representative of other LT recipients at the UNC, it likely overrepresented perspectives of LT recipients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD; 40%) and HCC (35%) as compared with national estimates based on United Network for Organ Sharing data (16%−20% for NAFLD and 23% HCC).(39,40) Most notable was the overrepresentation of patients with HCC, whose experiences after LT are markedly different from those with decompensated cirrhosis given abrupt changes in health status before and after LT (ie, being “well” prior to LT). Further investigation is needed to understand how pre-LT health status informs post-LT recovery including coping with and adapting to the new physical, emotional, and psychological challenges after LT. Although the findings from this study may not be generalizable to the overall LT population, including individuals outside of the United States, our sample was diverse in terms of age, sex, and race/ethnicity and offered varied opinions on post-LT experiences. Moreover, our results provide an important perspective from the growing population of patients with NAFLD and HCC undergoing LT. Other limitations of this small qualitative study included not being able to stratify results based on important variables including age, sex, and indication for LT. Despite this limitation, some nuances in differing survivorship experiences were seen based on sex and HCC diagnosis. The strengths of this study included using in-depth qualitative interviews that allowed for a more intimate discussion that can facilitate patient-driven conversations to elicit what is important to the patient and caregiver.(41) In turn, this research generated a deeper investigation of attitudes, experiences, and health behaviors and provides a more thorough needs assessment that can inform future intervention research interventions to improve LT survivorship.(42,43) Overall, there is variability in institutional practices when it comes to LT education, orientation, and resources provided for patients and caregivers. We identified key areas for intervention based on patient and caregiver opinions on what they wish they had known or resources they wish had been available during the process. These findings have important implications for other solid organ transplant recipients who likely share similar experiences.

In conclusion, understanding post-LT challenges through the lens of survivorship offers a unique perspective on the physical, emotional, and psychological experiences of patients and caregivers. This qualitative research contributes to our understanding of LT survivorship and generates evidence to inform future intervention research aimed at improving patient-centered outcomes after transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Maihan Vu, Dr. P.H., and Jessica Carda-A uten, M.P.H., from University of North Carolina Connected Health Applications and Interventions for their assistance with coding and analyzing the qualitative data in this study.

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK034987 and T32 DK007634) and by an American Association of Liver Disease Transplant Hepatology Award (2020–2021).

Donna M. Evon received grants from Gilead and Merck.

Sarah R. Lieber participated in the concept/design, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, article drafting, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Hannah P. Kim participated in the concept/design, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Luke Baldelli participated in the concept/design, data collection, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Rebekah Nash participated in the concept/design, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Randall Teal participated in data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Gabrielle Magee participated in data collection, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Chirag S. Desai participated in the critical revision of the article and approval of the article. Marci M. Loiselle participated in the concept/design, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. Simon C. Lee, Amit G. Singal, and Jorge A. Marrero participated in the data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article. A. Sidney Barritt IV and Donna M. Evon participated in the concept/design, data analysis/interpretation, critical revision of the article, and approval of the article.

Abbreviations:

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- PBC

primary biliary cholangitis

- PICC

peripherally inserted central catheter

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- UNC

University of North Carolina

ReFerences

- 1).Lieber SR, Kim HP, Baldelli L, Nash R, Teal R, Magee G, et al. What survivorship means to liver transplant recipients— qualitative groundwork for a survivorship conceptual model. Liver Transpl 2021;27:1454–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Lai JC, Ufere NN, Bucuvalas JC. Liver transplant survivorship. Liver Transpl 2020;26:1030–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Painter P, Krasnoff J, Paul SM, Ascher NL. Physical activity and health-related quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2001;7:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Hunt CM, Tart JS, Dowdy E, Bute BP, Williams DM, Clavien P-A. Effect of orthotopic liver transplantation on employment and health status. Liver Transpl 1996;2:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Aadahl M, Hansen BA, Kirkegaard P, Groenvold M. Fatigue and physical function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2002;8:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).van den Berg-Emons R, van Ginneken B, Wijffels M, Tilanus H, Metselaar H, Stam H, Kazemier G. Fatigue is a major problem after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006;12:928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).van Ginneken BTJ, van den Berg-Emons RJG, Kazemier G, Metselaar HJ, Tilanus HW, Stam HJ. Physical fitness, fatigue, and quality of life after liver transplantation. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007;100:345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Bownik H, Saab S. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation for adult recipients. Liver Transpl 2009;15(suppl 2):S42–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Sullivan KM, Radosevich DM, Lake JR. Health-related quality of life: two decades after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2014;20:649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Hellgren A, Berglund B, Gunnarsson U, Hansson K, Norberg U, Bäckman L. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg 1998;4:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Bravata DM, Olkin I, Barnato AE, Keeffe EB, Owens DK. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl Surg 1999;5:318–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Stilley CS, Miller DJ, Manzetti JD, Marino IR, Keenan RJ. Optimism and coping styles: a comparison of candidates for liver transplantation with candidates for lung transplantation. Psychother Psychosom 1999;68:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Forsberg A, Bäckman L, Svensson E. Liver transplant recipients’ ability to cope during the first 12 months after transplantation— a prospective study. Scand J Caring Sci 2002;16:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Nickel R, Wunsch A, Egle UT, Lohse AW, Otto G. The relevance of anxiety, depression, and coping in patients after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2002;8:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Telles-Correia D, Barbosa A, Mega I, Monteiro E. Importance of depression and active coping in liver transplant candidates’ quality of life. Prog Transplant 2009;19:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Telles-Correia D, Barbosa A, Mega I, Barroso E, Monteiro E. Psychiatric and psychosocial predictors of medical outcome after liver transplantation: a prospective, single-center study. Transplant Proc 2011;43:155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Rogal SS, Landsittel D, Surman O, Chung RT, Rutherford A. Pretransplant depression, antidepressant use, and outcomes of orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2011;17:251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Annema C, Drent G, Roodbol PF, Stewart RE, Metselaar HJ, van Hoek B, et al. Trajectories of anxiety and depression after liver transplantation as related to outcomes during 2-year follow-up. Psychosom Med 2018;80:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Stilley CS, Flynn WB, Sereika SM, Stimer ED, DiMartini AF, deVera ME. Pathways of psychosocial factors, stress, and health outcomes after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant 2012;26:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Dew MA, Rosenberger EM, Myaskovsky L, DiMartini AF, DeVito Dabbs AJ, Posluszny DM, et al. Depression and anxiety as risk factors for morbidity and mortality after organ transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis1. Transplantation 2015;100:988–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Drent G, De Geest S, Dobbels F, Kleibeuker JH, Haagsma EB. Symptom experience, nonadherence and quality of life in adult liver transplant recipients. Neth J Med 2009;67:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).De Geest S, Burkhalter H, Berben L, Bogert LJ, Denhaerynck K, Glass TR, et al. The Swiss Transplant Cohort Study’s framework for assessing lifelong psychosocial factors in solid-organ transplants. Prog Transplant 2013;23:235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Lieber SR, Volk ML. Non-adherence and graft failure in adult liver transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:824–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Christina S, Annunziato RA, Schiano TD, Anand R, Vaidya S, Chuang K, et al. Medication level variability index predicts rejection, possibly due to nonadherence, in adult liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2014;20:1168–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Vanhoof JMM, Vandenberghe B, Geerts D, Philippaerts P, De Mazière P, DeVito Dabbs A, et al. Shedding light on an unknown reality in solid organ transplant patients’ self-management: a contextual inquiry study. Clin Transplant 2018;32:e13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Gordon EJ, Prohaska TR, Gallant M, Siminoff LA. Self-care strategies and barriers among kidney transplant recipients: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 2009;5:75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Gordon EJ, Gallant M, Sehgal AR, Conti D, Siminoff LA. Medication-taking among adult renal transplant recipients: barriers and strategies. Transpl Int 2009;22:534–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).De Geest S, Abraham I, Gemoets H, Evers G. Development of the long-term medication behaviour self-efficacy scale: qualitative study for item development. J Adv Nurs 1994;19:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Lucey MR, Terrault N, Ojo L, Hay JE, Neuberger J, Blumberg E, Teperman LW. Long-term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl 2013;19:3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Jones JB. Liver transplant recipients’ first year of posttransplant recovery: a longitudinal study. Prog Transplant 2005;15:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Bardet J-D, Charpiat B, Bedouch P, Rebillon M, Ducerf C, Gauchet A, et al. Illness representation and treatment beliefs in liver transplantation: an exploratory qualitative study. Ann Pharm Françaises 2014;72:375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Belle SH, Porayko MK, Hoofnagle JH, Lake JR, Zetterman RK. Changes in quality of life after liver transplantation among adults. Liver Transpl 1997;3:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Moore K, Jones RM, Burrows GD. Quality of life and cognitive function of liver transplant patients: a prospective study. Liver Transpl 2000;6:633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Paslakis G, Beckmann M, Beckebaum S, Klein C, Gräf J, Erim Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder, quality of life, and the subjective experience in liver transplant recipients. Prog Transplant 2018;28:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Shemesh Y, Peles-Bortz A, Peled Y, HarZahav Y, Lavee J, Freimark D, Melnikov S. Feelings of indebtedness and guilt toward donor and immunosuppressive medication adherence among heart transplant (HTx) patients, as assessed in a cross-sectional study with the Basel Assessment of Adherence to Immunosuppressive Medications Scale (BAASIS). Clin Transplant 2017;31:e13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Wadhwani SI, Bucuvalas JC, Brokamp C, Anand R, Gupta A, Taylor S, et al. Association between neighborhood-level socioeconomic deprivation and the medication level variability index for children following liver transplantation. Transplantation 2020;104:2346–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Saab S, Bownik H, Ayoub N, Younossi Z, Durazo F, Han S, et al. Differences in health-related quality of life scores after orthotopic liver transplantation with respect to selected socioeconomic factors. Liver Transpl 2011;17:580–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Cholankeril G, Wong RJ, Hu M, Perumpail RB, Yoo ER, Puri P, et al. Liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the US: temporal trends and outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:2915–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Ong J, Trimble G, AlQahtani S, Younossi I, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly increasing indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:580–589.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Tong A, Chapman JR, Israni A, Gordon EJ, Craig JC. Qualitative research in organ transplantation: recent contributions to clinical care and policy. Am J Transplant 2013;13:1390–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Gagnon M, Jacob JD, McCabe J. Locating the qualitative interview: reflecting on space and place in nursing research. J Res Nurs 2015;20:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 43).Anderson J, Adey P, Bevan P. Positioning place: polylogic approaches to research methodology. Qual Res 2010;10:589–604. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.