Abstract

Pathogenic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) compromise cellular metabolism, contributing to cellular heterogeneity and disease. Diverse mutations are associated with diverse clinical phenotypes, suggesting distinct organ- and cell-type-specific metabolic vulnerabilities. Here we establish a multi-omics approach to quantify deletions in mtDNA alongside cell state features in single cells derived from six patients across the phenotypic spectrum of single large-scale mtDNA deletions (SLSMDs). By profiling 206,663 cells, we reveal the dynamics of pathogenic mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy consistent with purifying selection and distinct metabolic vulnerabilities across T-cell states in vivo and validate these observations in vitro. By extending analyses to hematopoietic and erythroid progenitors, we reveal mtDNA dynamics and cell-type-specific gene regulatory adaptations, demonstrating the context-dependence of perturbing mitochondrial genomic integrity. Collectively, we report pathogenic mtDNA heteroplasmy dynamics of individual blood and immune cells across lineages, demonstrating the power of single-cell multi-omics for revealing fundamental properties of mitochondrial genetics.

Mitochondria are complex organelles essential for metabolism and carry their own genome. Characterized by a high mutation rate, cell cycle-independent (relaxed) replication and variable copy number, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) possesses distinct genetic properties compared to nuclear DNA. In human cells, mitochondrial genomes are present in high copy numbers (100–1,000s), and mutations in mtDNA may vary in their level of heteroplasmy (proportion of mitochondrial genomes carrying a specific variant) in and across individual cells1,2. Notably, mtDNA-related disorders affect approximately 1 in 4,300 individuals, many of which present with heterogeneous phenotypes, cell-type-specific defects and variable severity that may correlate with heteroplasmy of pathogenic mutations3. Similarly, the age-related accumulation of somatically mutated mtDNA molecules in human cells and tissues may contribute to a variety of complex human diseases1,2,4,5. While germline single nucleotide variants (SNV) have been studied in human tissues, the effects of a major class of mutations and large mtDNA deletions have been examined to a lesser extent. Notably, single large-scale mtDNA deletions (SLSMDs) have been implicated in a continuum of congenital disorders, including Pearson syndrome (PS), Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS) and chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO)6.

Recently, we and others have demonstrated the utility of single-cell genomics for mtDNA genotyping in combination with cellular state characterization7,8. The droplet-based mitochondrial single-cell assay for transposase accessible chromatin by sequencing (mtscATAC-seq) technique enables the scalable, concomitant profiling of accessible chromatin and mtDNA9,10. Further innovations enable additional single-cell measurements alongside chromatin accessibility and mtDNA genotyping, including antibody-based quantification of protein expression (ATAC with selected antigen profiling by sequencing (ASAP-seq)) and gene expression (DOGMA-seq)11. The application of these approaches has revealed the high prevalence of somatic mtDNA mutations, many of which are stably propagated and facilitate clonal/lineage tracing studies7–9,11. Moreover, these assays facilitate the study of pathogenic mtDNA variants associated with human disease. In patients with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) caused by the m.3243A > G mutation, we demonstrated a previously unappreciated purifying selection against pathogenic mtDNA in particular T cells, suggesting a link between heteroplasmy and cell state10.

Here we use a series of multi-omics single-cell approaches and introduce mgatk-del, a computational approach to assess heteroplasmy of mtDNA deletions with high sensitivity and specificity, in single cells from patients with SLSMD. By examining primary hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood and the bone marrow (n = 206,663 primary cell profiles), we reveal the distribution of pathogenic mtDNA deletions in hematopoietic lineages and its depletion or persistence in specific cell types indicative of distinct metabolic vulnerabilities. We identify context-dependent alterations in cell state as assessed by transcriptional, accessible chromatin, and protein expression profiling. Collectively, this study underscores the power of single-cell multi-omics to interrogate congenital mitochondriopathies, revealing metabolic requirements, vulnerabilities and cell-type-specific means of compensation.

Results

Single-cell quantification of mtDNA deletions

We have previously demonstrated that mtscATAC-seq yields relatively uniform coverage across the mitochondrial genome and can robustly quantify pathogenic SNVs in single cells9,10. Here we sought to assess this approach for detecting and quantifying large mtDNA deletions that underlie PS and related SLSMD. These large mtDNA deletions have been hypothesized to occur due to strand displacement errors in mtDNA replication between the heavy (OH) and light (OL) origins of replication and occur very early in development or oogenesis (Fig. 1a)12,13. To examine these deletions in single-cell data, we conducted mixing experiments by pooling in vitro cultured fibroblasts derived from two healthy donors and three patients with PS carrying three distinct mtDNA deletions for mtscATAC-seq (Fig. 1b). Following sequencing, cells from each donor were demultiplexed using private SNVs (Fig. 1b; Methods). Pseudobulk summaries of high-quality cells per donor revealed distinct dips in coverage along the mtDNA genome corresponding to the specific deletions at variable levels of heteroplasmy (Fig. 1c).

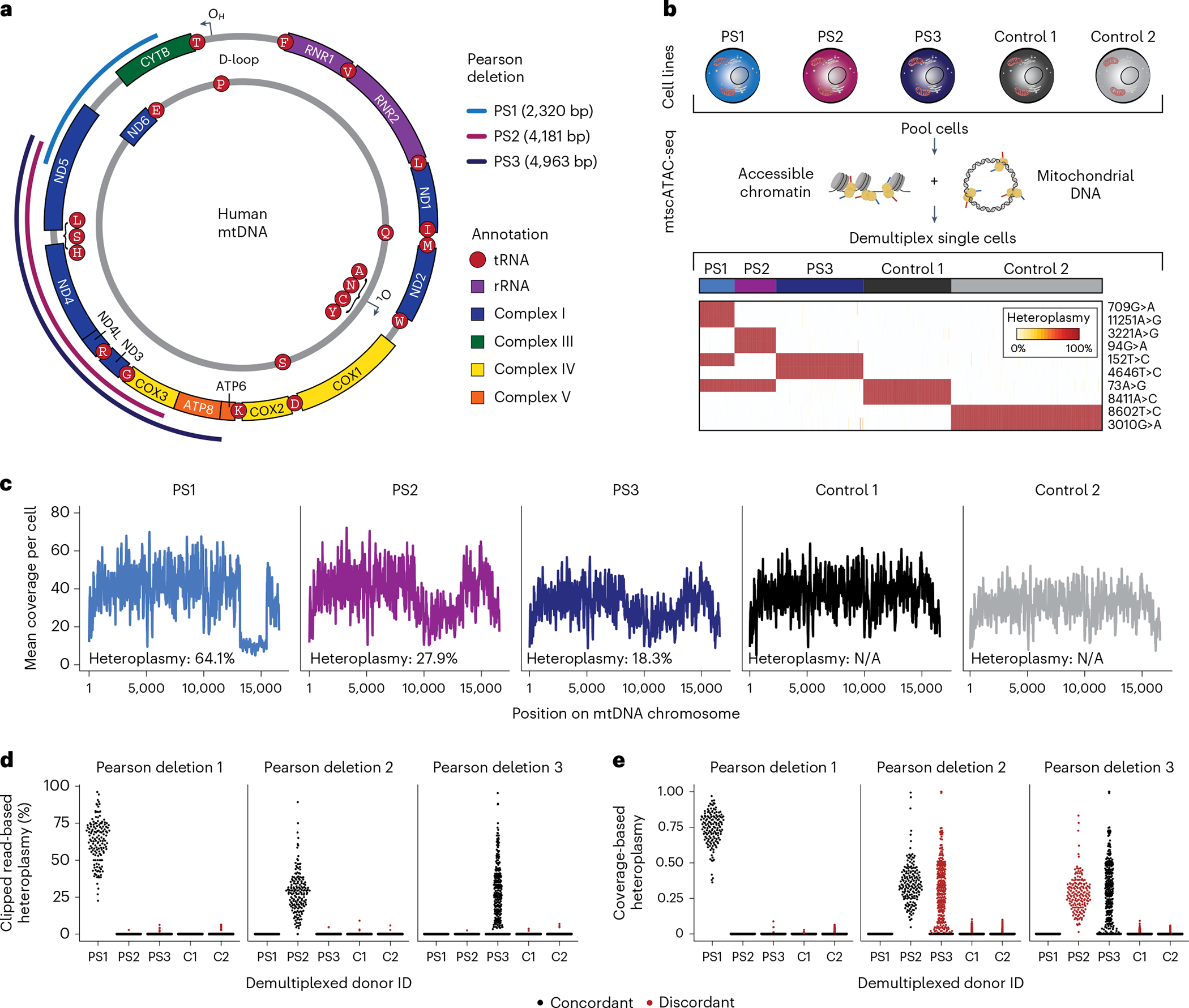

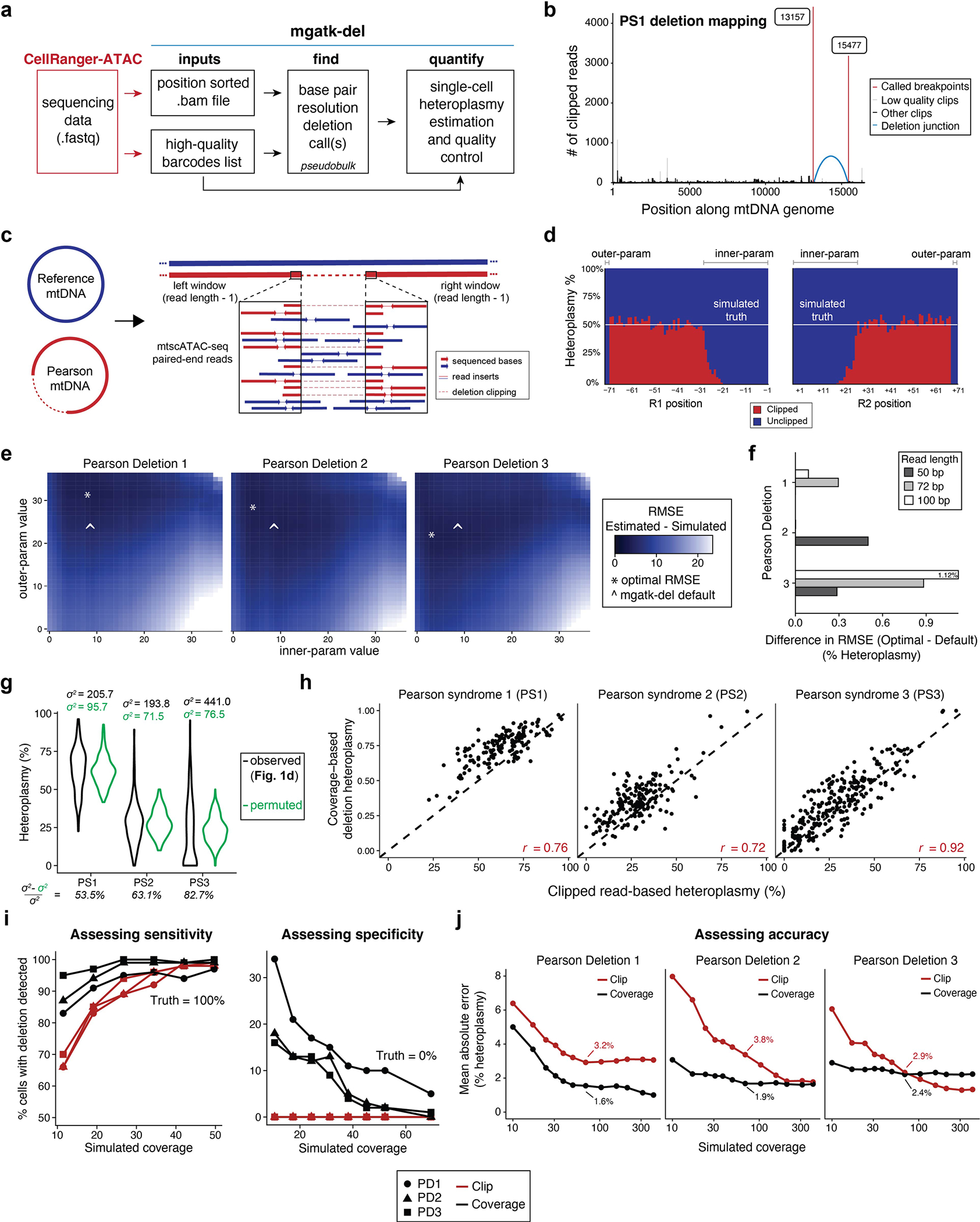

Fig. 1 |. Identification and quantification of heteroplasmic pathogenic mtDNA deletions in single cells.

a, Schematic of mtDNA in humans with PS-related deletions relevant for the cell lines examined in b. OH and OL represent the heavy and light chain origins of replication, respectively. PS1, PS2 and PS3 represent three different mtDNA deletions identified in three independent donors from which the cell lines were derived. Size and location of deletions are indicated. b, Summary of cell line mixing experiment and demultiplexing using mtDNA haplotype-derived SNVs in single cells. Heatmap depicts homoplasmic SNVs that facilitate the separation of cells from distinct donors. c, Mean coverage plots per cell across the mitochondrial genome for the demultiplexed donor cell identities. Drops in the coverage are indicative of large mtDNA deletions. d,e, Estimates of single-cell heteroplasmy using (d) clipped-read enumeration and (e) coverage-based approaches. Red dots represent false-positive heteroplasmy assessments from the deletion/donor pair (‘discordant’). Each dot represents estimated heteroplasmy from a single cell for each respective deletion. C1, C2 = Control 1 and Control 2 as in b and c.

Although the software has been developed to analyze mtDNA deletions in bulk sequencing data14,15, these workflows do not ensure valid estimation of deletion heteroplasmy, particularly in lower-coverage libraries such as individual cells, and do not readily scale to thousands of cells from a mtscATAC-seq library. Thus, we developed a computational approach, mgatk-del, that uses aligned mtDNA sequencing reads that result from the CellRanger-ATAC preprocessing (Extended Data Fig. 1a). To achieve precise heteroplasmy estimation, we reasoned that base-resolution breakpoints in sequencing reads (encoded as soft-clips in the alignments) could be used to infer deletion junctions, which could be corroborated with per-read secondary alignments reported from BWA (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c). Deletion heteroplasmy could then be estimated as a ratio of reads supporting or contradicting a deleted junction sequence. To benchmark this approach, we evaluated heteroplasmy estimation as a function of two hyperparameters using grid-searching simulated synthetic data (Extended Data Fig. 1c–f; Methods), yielding a method to accurately estimate heteroplasmy for each deletion.

Having established the computational approach, we quantified single-cell heteroplasmy for all three investigated pathogenic deletions. Following donor demultiplexing, our clipped-read heteroplasmy estimates revealed variation in deletion heteroplasmy across the population of cells (Fig. 1d), consistent with our previous observations of heterogeneity in cells derived from patients with mitochondriopathy caused by SNVs9,10 and exceeding the variation that could be explained from variable single-cell coverages under a null model (Extended Data Fig. 1g). Furthermore, nonzero heteroplasmy was highly specific for each PS cell line. Conversely, a coverage-based estimate of heteroplasmy (ratios of read depths within and outside the deleted region) showed greater nonspecific heteroplasmy at deletions discordant from the originating PS patient cells although both methods were overall concordant (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 1h–j; Methods). Together, our analyses demonstrate the ability of mgatk-del to map mtDNA deletions at base-pair resolution and quantify their heteroplasmy in single cells.

Purifying selection of mtDNA deletions in T cells

We then used mtscATAC-seq and mgatk-del to analyze mtDNA deletions and heteroplasmy in primary patient cells. We obtained peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from three cases, including a 7-year-old male with PS/KSS (‘PT1’), a 4-year-old female with PS (‘PT2’) and a 4-year-old male with PS and chromosomal 7q deletion (del7q) myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS, ‘PT3’). Each patient presented with a distinct SLSMD (Supplementary Table 1). PBMCs from all three patients were profiled using both mtscATAC-seq and 10× 3′ scRNA-seq to quantify heterogeneity of mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy, chromatin accessibility and transcriptional profiles (Fig. 2a). Application of mgatk-del revealed the base-resolution breakpoints corresponding to the deleted regions for each patient (without prior knowledge) and enabled the quantification of deletion heteroplasmy in single cells (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Among cells passing quality control (n = 15,064; mean 81.5× coverage), we observed marked variation of heteroplasmy in PBMCs, including hundreds of cells that had no detectable mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2 |. Purifying selection against pathogenic mtDNA deletions in peripheral blood MAIT and CD8 T cells in PS.

a, Schematic of single-cell genomics data generation. PBMCs from three patients (PT1, PT2 and PT3) with PS were collected and processed via scRNA-seq and mtscATAC-seq. b, Depiction of mtDNA deletions from three investigated patients with PS as determined by mgatkdel. Location and size of deletions are indicated. c, Violin plots of single-cell heteroplasmy across indicated patients and respective mtDNA deletions are indicated in b. Median heteroplasmy (%) and profiled cell numbers are indicated for each patient. d, Reduced dimensionality projection and joint clustering of PBMCs from three patients with PS and one healthy control are shown. Major cell types and clusters are annotated in the same color. e, Reduced dimensionality projection as in d split by patient with PS and colored by respective mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy. f–h, Cumulative distribution plots of heteroplasmy stratified by T-cell subset derived from PT1, PT2 and PT3. Each comparison is a two-sided binomial test for the proportion of 0% cells comparing CD4.TCM to CD4 naive, CD8.TEM to CD8 naive and MAIT to other T-cell subsets. i,j, Purifying selection of the m.3243A>G allele in individuals with MELAS as previously reported10. The cell annotations and statistical tests are the same as in f–h but for the m.3243A>G allele. k, A refined model of purifying selection in T cells with the relative ordering of cells based on the proportion and frequency of 0% heteroplasmic cells observed in these donors between the two disease cohorts. DC, dendritic cells; pDCs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; NK, natural killer cells.

As mtDNA genotypes are paired with single-cell chromatin accessibility data, we sought to examine heteroplasmy variability and dynamics as a function of cell state. We performed a dictionary-based reference mapping of all cells to a previously annotated atlas of PBMCs (Fig. 2d; Methods)16. Notably, our analyses revealed clusters of T cells consistently depleted of mutant mtDNA relative to other immune or T-cell populations across all three donors, including effector/memory CD8 T cells (CD8.TEM) and mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAIT) that could not be explained by variation in sequencing coverage (Fig. 2e–h, Extended Data Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Table 2). These results are reminiscent of the previously described purifying selection of pathogenic mtDNA in T cells from patients with MELAS10 but add nuance by revealing multiple subpopulations of affected T cells. To corroborate this inference, we performed the same dictionary-based reference annotation for MELAS cells. Indeed, MAIT and CD8.TEM cells displayed reduced heteroplasmy of mutant mtDNA (Fig. 2i,j and Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Overall, our results suggest that MAIT and CD8.TEM cells are both under specific selection pressures that are conserved between different classes of pathogenic mtDNA genotypes and diagnoses, thus resulting in a refined model of the degree of purifying selection in immune cells in the context of congenital mitochondrial disease (Fig. 2k).

In vitro T-cell models corroborate purifying selection

We sought to investigate pathogenic mtDNA dynamics during in vitro activation and differentiation of T cells from PS donors (Fig. 3a). We observed retention of naive-like marker CD45RA, reduced expansion of T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells, relative to healthy controls, consistent with the stronger selective pressure of CD8.TEM cells observed in vivo (Fig. 3b–d and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Conversely, parallel cultures of healthy adult and pediatric T cells did not show impairment either in total proliferation or in the ratio of CD8+:CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 3b). To link cell surface markers to pathogenic mtDNA heteroplasmy, we performed proteogenomic characterization via ASAP-seq at days 14 and 21 of culture, observing the percentage of cells with zero heteroplasmy increasing to 75%, compared to 23% in ex vivo PBMCs (Fig. 3e). Unsupervised dimensionality reduction and cell state annotation revealed heteroplasmy to be mostly restricted to naive-like CD45RA+ and Th17-like T cells (Fig. 3f–h and Extended Data Fig. 3c). In contrast, CD4+ and CD8+ effector-like T cells (marked by CD45RO+) had mostly selected against pathogenic mtDNA, suggesting that mitochondrial genetic integrity is essential to acquire these T-cell states. Identical observations were made upon extension of culture to day 21, which further revealed clonality of expanded T-cell populations as indicated by somatic mtDNA mutations (for example, m.12631T>C and m.4225A>G; Extended Data Fig. 3d–h). Culture of T cells from patient with PS (PT1) replicated these findings, including limited expansion, reduced CD8+:CD4+ ratio and depletion of heteroplasmy specifically in effector-like CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3i–k). Finally, we hypothesized that the fitness deficit of T cells in vitro may be mitigated through the supplementation of pyruvate (to accept electrons instead of oxygen) and uridine (to enable pyrimidine synthesis in the absence of DHODH activity) in the culture media17,18. To explore this, we repeated the T-cell expansion cultures with and without pyruvate and uridine (P&U) and assessed proliferation and viability via flow cytometry (Fig. 3i; Methods). Indeed, after 4 d of culture, we observed an increase in viability and proliferation (Fig. 3j,k), suggesting that restoring OXPHOS function may partially restore T-cell function. In total, our in vivo and in vitro results suggest that pathogenic mtDNA deletions compromise the proliferation and differentiation of naive to effector T-cell states, with a particular vulnerability of the CD8.TEM lineage.

Fig. 3 |. Altered CD8+ T cell expansion and purifying selection of pathogenic mtDNA deletions in vitro.

a, Schematic of experimental design. PBMC-derived T cells were cultured and activated via α-CD3 and α-CD28 for ~3 weeks. ASAP-seq and flow cytometry measures were collected longitudinally. b, Fold expansion for all cells in culture for the healthy donors (blue) compared to the Pearson donor (red). c, Dynamics of CD8+ to CD4+ T-cell ratios in culture over time, implicating deficient CD8+ expansion of PS cells. d, Percentage of CD45RAhi/CD45RO− among CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) cells from the four donors over 12 d. e, Per-sample distribution of heteroplasmy of T cells from PBMCs, after 14 d in culture, and after 21 d in culture demonstrating most selection to have occurred by day 14 of culture relative to PBMCs. f, Day 14 ASAP-seq embedding annotated by heteroplasmy (%). g, The same embedding in f but colored by ADTs for CD45RA, CD8 and CD4, allowing for annotation of cluster-specific cell states. h, Cell state clusters of the day 14 ASAP-seq embedding. Per-cluster heteroplasmy is depicted via a continuous distribution plot. i, Schematic of in vitro culture experiment with and without 1 mM pyruvate and 200 nM uridine (P&U) supplementation. j, Cell trace violet plots showing cell division traces of a healthy donor and three donors with PS stratified by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. k, All comparisons between none and P&U were not significantly different at an α value of 0.05 using a Student’s paired t-test.

Deletion heteroplasmy in adults with SLSMD

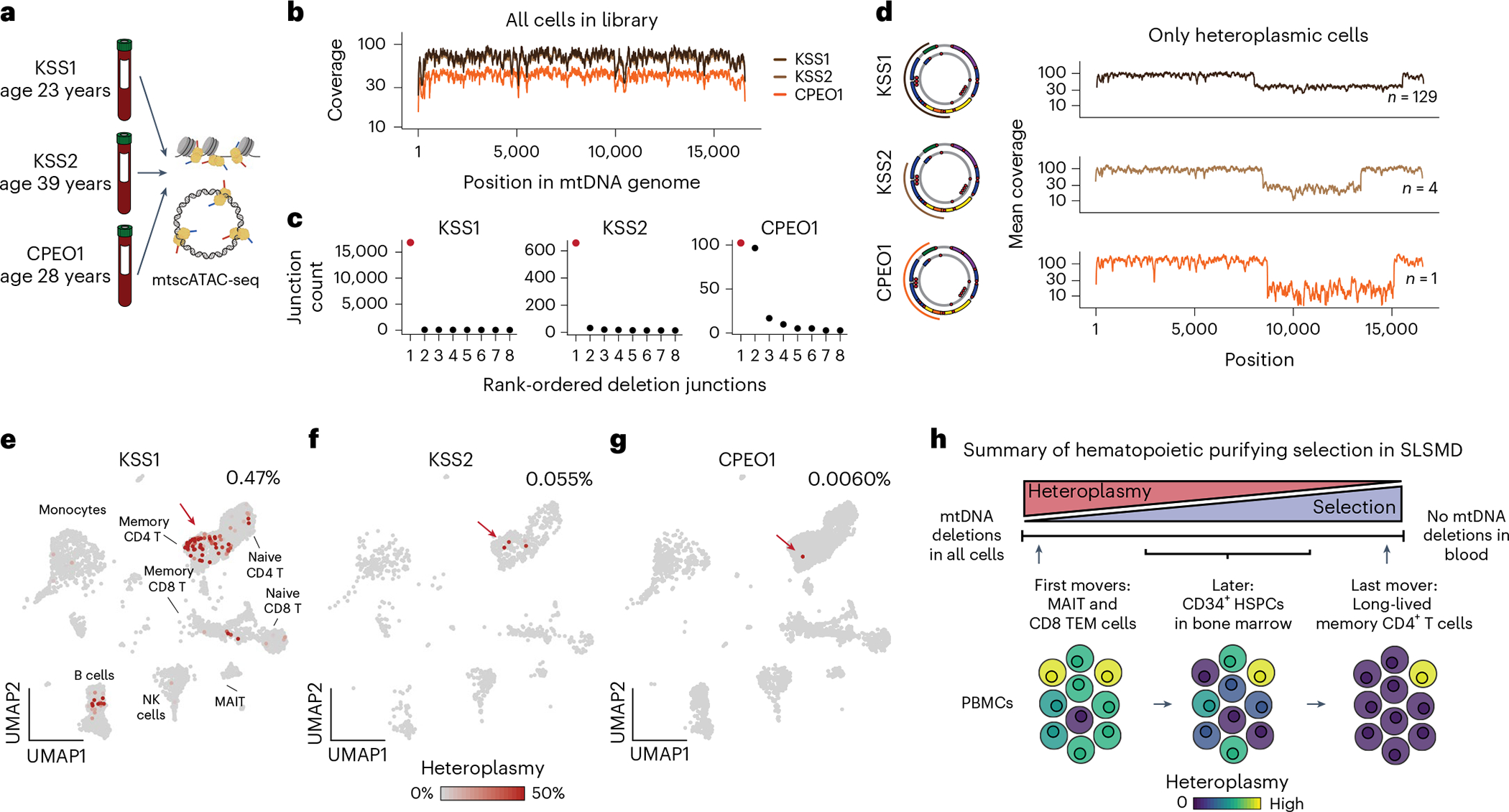

While PS may be lethal early in life, individuals with CPEO and KSS, other diseases caused by SLSMD, more commonly live into adulthood. To study the dynamics of purifying selection of SLSMD in the immune system after decades of life, we profiled three donors aged 23–39 years with mtscATAC-seq (Fig. 4a). While an initial examination of mtDNA coverage did not reveal obvious deletions (Fig. 4b), application of clipped-read analysis via mgatk-del revealed specific large deletions between 4,965 bp and 7,514 bp in all three donors (Fig. 4c,d), including deletions with 0.0060% pseudobulk heteroplasmy. Here all reads supporting the deletion came from the same cell (68.8% heteroplasmy; 11 unique reads supporting the deletion), whereas other software19,20 failed to uncover this rare event. For all three patients, we observed that these heteroplasmic cells were enriched in the CD4+ central memory and regulatory T-cell compartments (53.0% of nonzero heteroplasmy cells versus 25.0% of all cells; Fisher’s exact P = 9.9 × 10−7; Fig. 4e–g). Thus, analysis of adult patients with SLSMD provides a lens into the lifetime dynamics of pathogenic mtDNA deletions, indicating CD8. TEM and MAIT cells are initially most sensitive to the selection, which over time extends to CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and all descending cells, leaving long-lived CD4+ cells with residual heteroplasmy (Fig. 4h).

Fig. 4 |. Purifying selection and retention of pathogenic mtDNA heteroplasmy across the peripheral blood in adults with SLSMD.

a, Three donors with either KSS or CPEO were profiled using mtscATAC-seq. b, Pseudobulk coverage of three donors across the mtDNA genome. c, Results of deletion calling from mgatk-del find. Each dot represents a pair of junctions. The junction pair marked in red represents the pathogenic deletion. d, Validation of deletions in cells from pseudobulk coverage estimates in cells with nonzero heteroplasmy. The coordinates of the deletions are noted in the miniature diagrams of the mtDNA deletions. e–g, Reference projection of cell states from mtscATAC-seq (as in Fig. 2d) with heteroplasmy annotated for the indicated mtDNA deletions. The red arrow points to the memory CD4+ T-cell compartment. Only a single cell harbored the deletion for the patient with CPEO (heteroplasmy = 68.8%; 11 reads supporting the deletion; 5 reads supporting wild-type mtDNA). h, Schematic of the lifetime dynamics of purifying selection against pathogenic mtDNA across PS (as in Fig. 2k) and other SLSMDs.

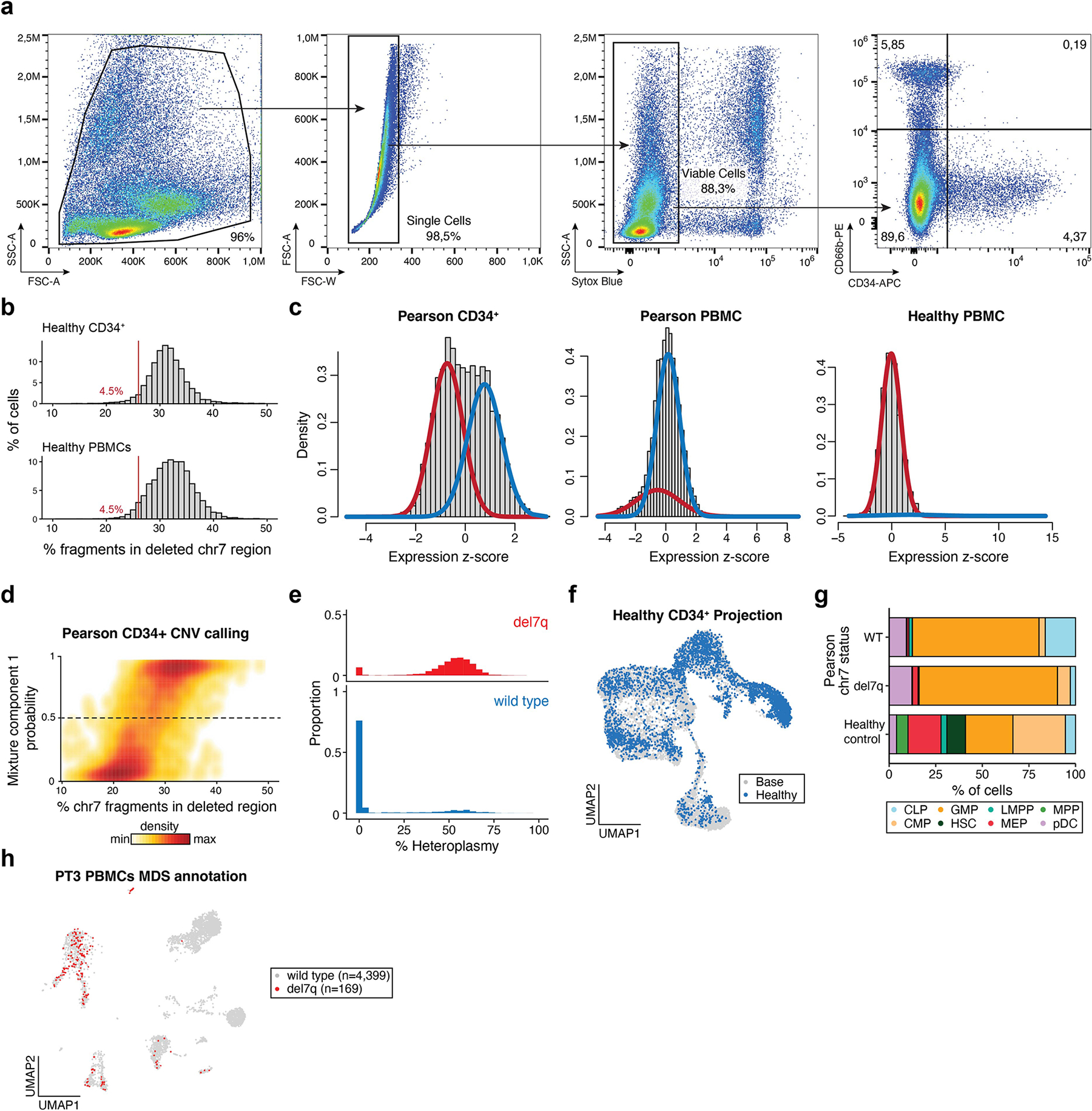

Identification of mosaic del7q cells

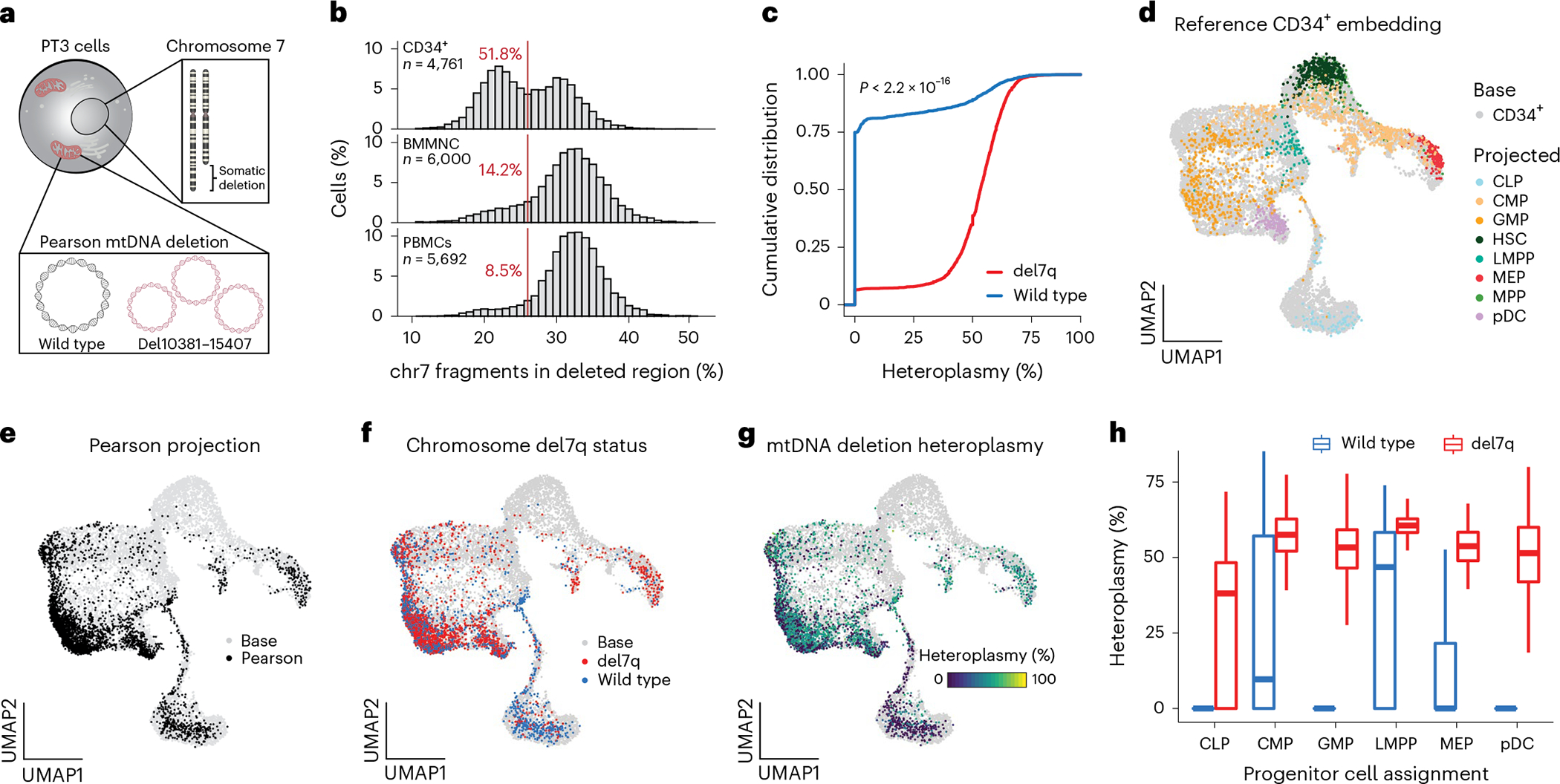

For PT3 with PS, the clinical evaluation revealed a mosaic del7q, a chromosomal abnormality consistent with the development of MDS on the backdrop of a congenital bone marrow failure syndrome (Fig. 5a)21. Notably, the acquisition of monosomy 7 has recently been reported in a case of PS22. We applied mtscATAC-seq to PT3 bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) with and without CD34+ enrichment (Extended Data Fig. 4a) to analyze the association of mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy and the nuclear del7q abnormality at single-cell resolution. To assess the distribution of del7q cells, we first examined the abundance of fragments overlapping the deleted region, which revealed a clear multimodal distribution, that could be classified using a Gaussian mixture model (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 4b–d; Methods). As del7q was most abundant in CD34+ HSPCs, we examined the association between del7q and mtDNA heteroplasmy in these cells. Notably, we observed a striking association where del7q cells had substantially higher levels of mutant mtDNA, suggesting the acquisition of del7q in HSPCs with the most compromised mitochondrial function (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 4e).

Fig. 5 |. Myelodysplastic cells resolved by a chromosomal 7q deletion in CD34+ HSPCs in a case of PS.

a, Schematic depicting the del7q and mtDNA deletion of PT3 in the same cell. b, Histograms showing the percentage of fragments on chromosome 7 mapping to the somatically deleted region. A consistent cutoff of 26% with the percentage of cells below this threshold is indicated in red. n, cells assayed for each indicated population of CD34+, BMMNC and PBMCs. c, Cumulative distribution curves of mtDNA heteroplasmy stratified by the del7q status per cell. Statistical test—two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. d, UMAP of a reference CD34+-based embedding (base; gray) with sorted cell populations projected (color coded) onto the reference. All cells were derived from healthy donors. CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte–monocyte progenitors; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LMPP, lymphoid primed multipotent progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte erythroid progenitor; MPP, multipotent progenitor; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell. e, Projection of PS CD34+ cells onto the same base embedding as in d. f, Annotation of del7q status for each PS CD34+ cell, indicating diploid (blue) and del7q (red) status. g, Annotation of single-cell mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy per PS CD34+ cell. h, Heteroplasmy (%) stratified based on annotated CD34+ progenitor cell state and by del7q ploidy status. Data from one biologically independent sample and experiment. Boxplots—center line, median; box limits, first and third quartiles; whiskers, 1.5× interquartile range.

To refine our analysis, we projected CD34+ PT3 data onto a healthy donor reference of sorted CD34+ cells to define the continuous differentiation trajectory of these progenitors via patterns of chromatin accessibility (Fig. 5d; Methods)23,24. Relative to healthy control cells, PT3 displayed a stark depletion of cells annotated as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) as well as an enrichment of granulocyte–monocyte progenitors (GMP) and monocytes in peripheral blood, resulting in a markedly different estimated composition of the entire HSPC compartment (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 4f–h). We observed the pronounced presence of del7q in PT3 GMPs and multipotent erythroid progenitors (MEP), consistent with the MDS phenotype (Fig. 5f). Notably, the PT3 common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) population was mostly wild-type for chr7 and depleted of pathogenic mtDNA (Fig. 5g,h). Together, these analyses reveal the complexity of lineage commitment and differentiation in the presence of pathogenic mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy and the onset of MDS within the early hematopoietic progenitor compartment of the patient with PS.

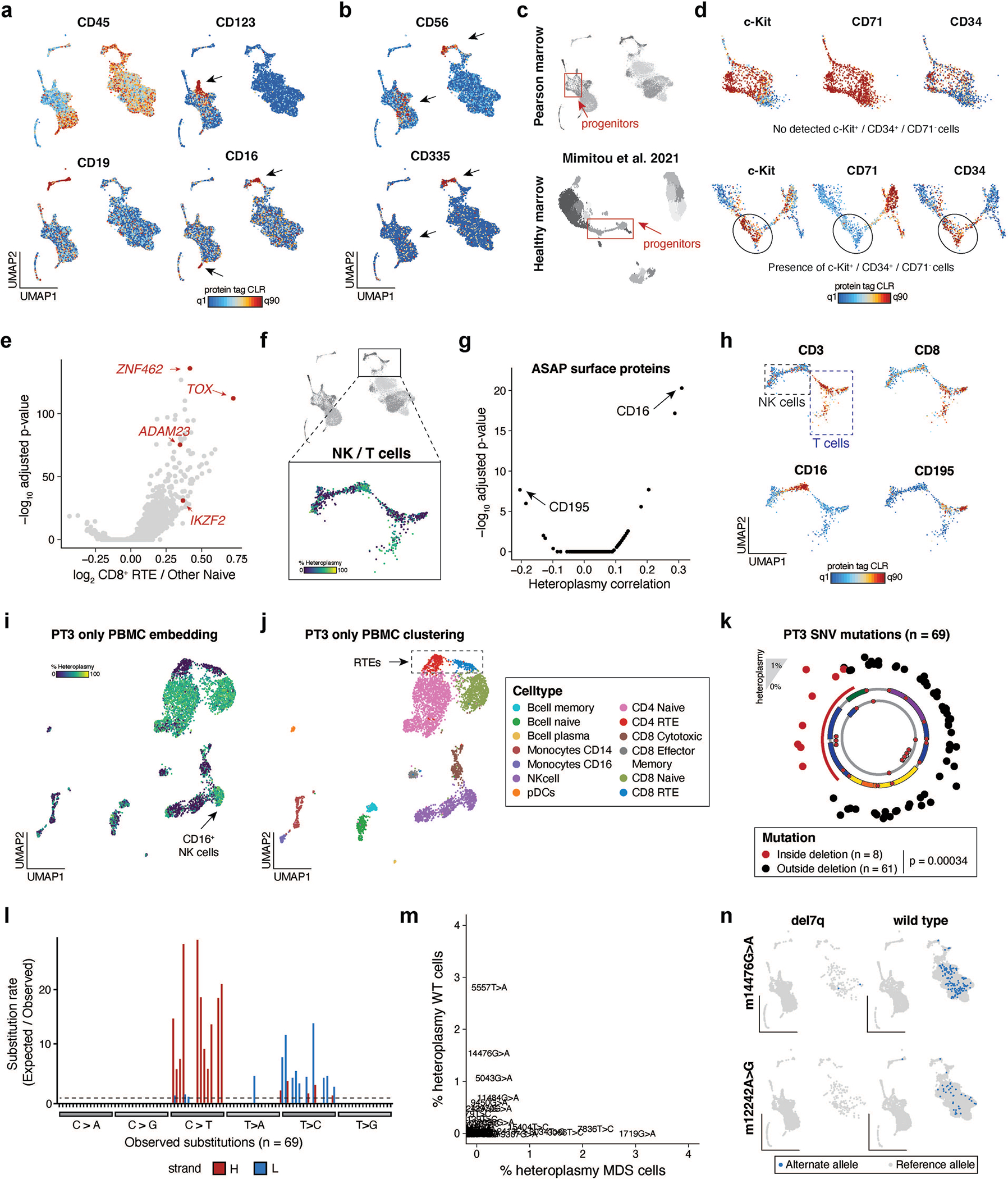

Purifying selection in hematopoietic development

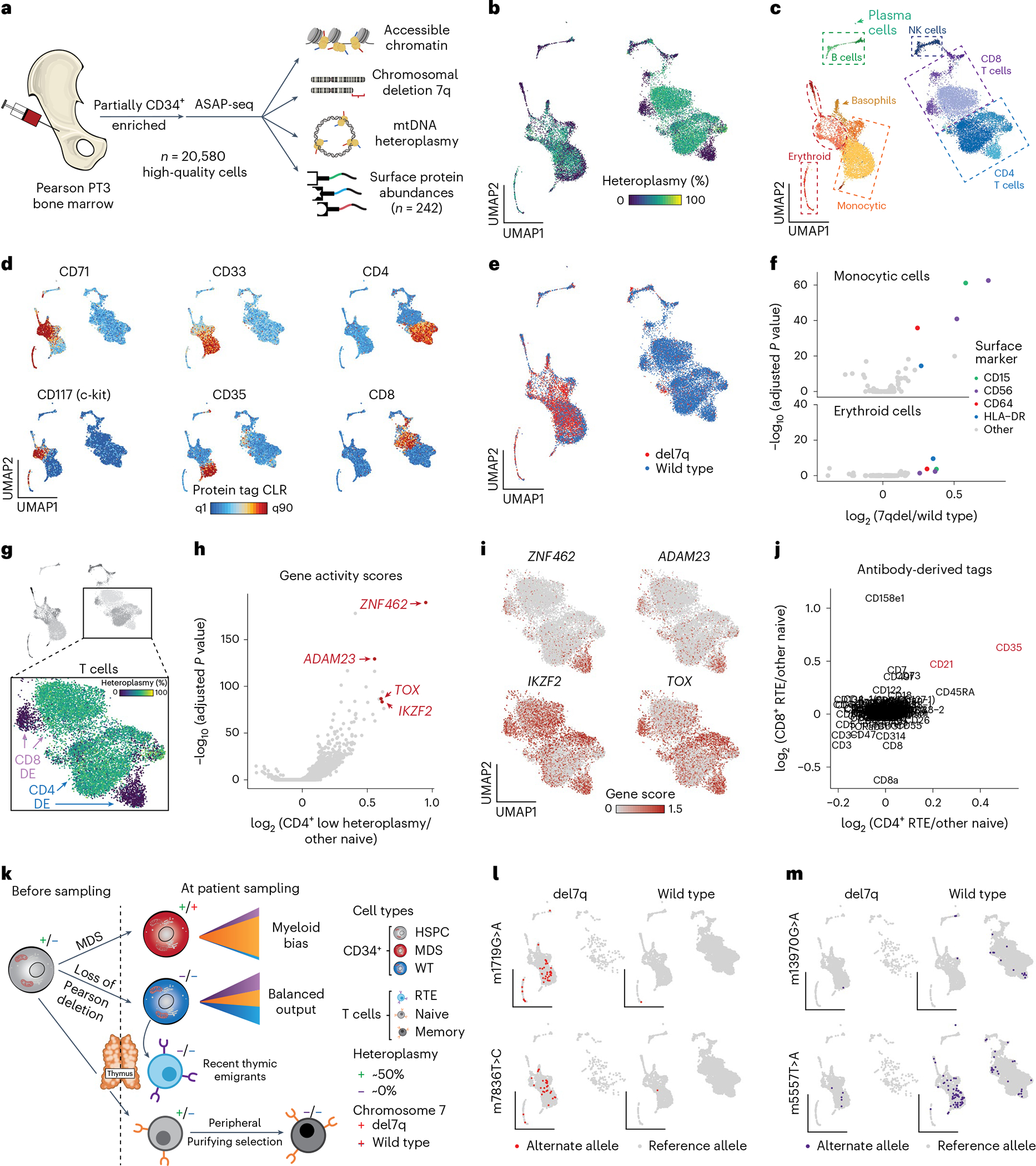

To further investigate the interplay of del7q and mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy dynamics across the hematopoietic compartment, we applied ASAP-seq to PT3-derived BMMNCs, including the profiling of 242 surface antigens, yielding 20,580 high-quality cells with quantification across four distinct modalities per cell (chromatin accessibility, nuclear chromosomal aberrations, mtDNA genotypes and surface protein abundance; Fig. 6a). We revealed variation in heteroplasmy across hematopoietic lineages with the proteogenomic measurements facilitating more highly resolved inferences of cell type/state (Fig. 6b–d and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Furthermore, our mixture model approach identified del7q to be primarily in myeloid and erythroid cells and largely absent in lymphocytes (Fig. 6e).

Fig. 6 |. Multimodal characterization of PS BMMNCs with ASAP-seq.

a, Schematic of ASAP-seq experiment from PS BMMNCs derived from PT3 with MDS. b, Dimensionality reduction and embedding for high-quality BMMNCs with heteroplasmy colored. c, The same embedding as in b is annotated by major cell type clusters. d, Selected lineage-defining surface protein markers are shown on the reduced dimension space as in b and c. e, Projection of annotated del7q status onto the UMAP space as in b and c. f, Volcano plots of differentially expressed protein surface markers inferred from antibody barcodes for del7q versus wild-type cells annotated as erythroid or monocytic from c. Markers with distinct colors were significantly upregulated in both comparisons (logFC > 0.1 and Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction P < 0.01). g, Schematic illustrating CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell clusters used for differential gene score expression (DE) analyses to identify markers distinguishing low-heteroplasmy cell populations. h, Volcano plot showing differential gene activity scores for comparison of CD4+ T-cell clusters as illustrated in g. Genes in red (ZNF462, ADAM23, IKZF2 and TOX) indicate marker genes for RTEs. i, Projected gene scores for indicated marker genes onto UMAP space as highlighted in g. j, Differentially expressed proteins for the comparisons of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations as illustrated in g. CD21 and CD35, shown in red, are known surface markers for RTEs. A total of three markers (CD21, CD35 and CD45RA) were significantly upregulated in both CD4+ and CD8 T+ RTEs (logFC > 0.1 and Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction P < 0.01). k, Schematic of multifaceted clonal output and purifying selection in PT3 with PS and MDS. Major cell transitions are depicted as a function of 7qel status and mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy. l, Projection of somatic mtDNA mutations m.1719G>A and m.7836T>C enriched in cells carrying the del7q. m, Projection of somatic mtDNA mutations m.13970G>A and m.5557T>A enriched in wild-type cells (diploid for chr 7), including in RTEs.

We performed integrative analyses to determine surface markers overexpressed on del7q compared to chr7 wild-type monocytic and erythroid cells (Fig. 6f). For both comparisons, we observed an enrichment of surface proteins CD15, CD56, CD64 and HLA-DR, all markers that have previously been reported to be upregulated in patients with MDS25,26. Unlike CD56, other markers of NK cells such as CD335 were not expressed on MDS-associated cells, but were present exclusively on NK cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b). In addition, we corroborated our observation of the depletion of phenotypic HSCs as revealed in the CD34+ projection analysis (Fig. 5d,e). We compared the distribution of HSPC populations and protein markers in PS to healthy donor bone marrow ASAP-seq data11 and were unable to detect CD34+c-Kit+CD71 cells in PT3 despite the clear presence of these cells in healthy BMMNCs (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Noting that HSCs do not express CD71, our integrated analysis confirms the apparent relative depletion of phenotypic HSCs in PT3, which may further present a consequence of the pathogenic mtDNA deletion and/or the MDS phenotype.

Then, we investigated two subpopulations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that were depleted of pathogenic mtDNA heteroplasmy. Differential gene accessibility revealed markers associated with recent thymic emigrants (RTEs)27, including ADAM23, IKZF2, TOX and ZNF462 (Fig. 6g–i and Extended Data Fig. 5e). Differential protein expression of the same populations showed a relative enrichment of CD21 and CD35 (Fig. 6j), which are both upregulated on RTEs27. Notably, we verified the presence of RTE-heteroplasmy-depleted cells in peripheral blood by reclustering PBMCs from PT3, which did not separate RTEs in our previous reference projection analyses (Fig. 2) and confirmed the purifying selection of CD8.TEM cells in the bone marrow (Extended Data Fig. 5f–j). Overall, integrating our observations of populations depleted of pathogenic mtDNA deletions— including CLPs in the CD34+ compartment (Fig. 5d,g), subpopulations of CD4+/CD8+ RTEs and CD8.TEM cells in multiple hematopoietic compartments— suggests multiple distinct modes of purifying selection at distinct stages of lymphopoiesis (Fig. 6k).

As we have previously demonstrated somatic mtDNA SNVs to identify clonal subsets in hematopoietic populations of adults7,9, we sought to determine the prevalence of these mutations at 4 years of age. Application of mgatk revealed 69 somatic mtDNA SNVs that were enriched in expected nucleotide substitution patterns9,11, located largely outside of the mtDNA deleted region and present in both del7q and wild-type cells (Extended Data Fig. 5k–m). For example, variants m.1719G>A and m.7836T>C refined clones within the del7q compartment, whereas variants m.12242A>G, m.14476G>A, m.5557T>A and m.13970G>A were predominantly found in cells with wild-type chr7 (Fig. 6l,m and Extended Data Fig. 5n). Notably, the m.5557T>A variant was observed in both CD4+ and CD8+ RTEs and in the myeloid compartment, suggesting that the HSPC carrying this variant is capable of multi-lineage output, whereas variants m.12242A>G and m.14476G>A were only identified in lymphoid cells. Together, our analyses indicate that the utility of mtDNA-based lineage tracing extends to pediatric patients and clonal myeloid disorders.

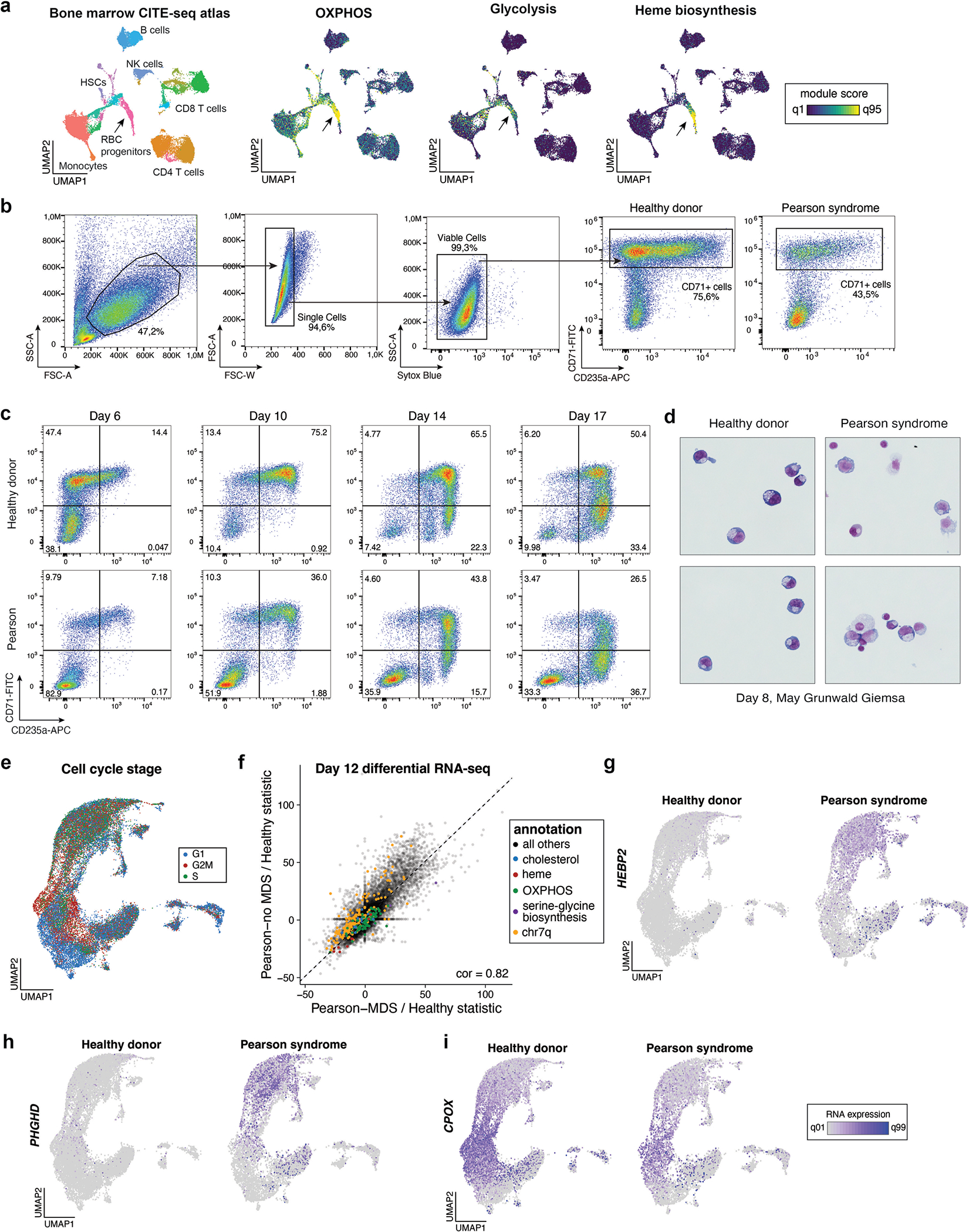

Selection dynamics in erythropoiesis

A hallmark feature of PS is severe macrocytic sideroblastic anemia, characterized by erythroblasts accumulating iron deposits around their mitochondria, which is frequently detectable in the neonatal period and often in the context of evolution to pancytopenia (a significant reduction in the number of all blood cells)28–30. Given this phenotype, we sought to understand the selection dynamics and altered gene expression programs underlying defective erythropoiesis. To realize this, we performed pseudotime trajectory inference for 1,511 cells from the BMMNC ASAP-seq data along the erythroid pseudotime axis (Fig. 7a; Methods). Our trajectory corroborated known cell state markers associated with early-to-late erythroid transitions from both surface protein and chromatin accessibility, including the GATA1 and TMCC2 loci (Fig. 7b)31. Along this axis, the proportion of cells harboring del7q and mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy was greatly reduced (Fig. 7c,d), suggesting selection during late erythropoiesis. Differentiating erythroid cells also showed high OXPHOS module scores relative to other BMMNCs, indicative of a high metabolic demand (Extended Data Fig. 6a). These findings support a model of the high vulnerability of the erythroid lineage and its altered output in PS, analogous to our observations of increased OXPHOS demand and resulting selection during T-cell proliferation and differentiation.

Fig. 7 |. Altered erythroid differentiation and selection in PS.

a, Erythroid pseudotime trajectory of in vivo ASAP-seq data. The color bar represents the annotated pseudotime for 1,511 cells, with the arrow orienting the inferred trajectory for the embedding in Fig. 6c. b, Summary of cell state features along erythroid pseudotime axis. c, Abundance of del7q cells along erythroid pseudotime axis. The mean of each pseudotime bin is noted ±s.e.m. d, Distribution of heteroplasmy across erythroid pseudotime bins. Each cell is plotted in color matching (a) with the per-bin median noted in black. e, Schematic of experimental design. BMMNCs were derived from PT3 with PS/MDS and healthy controls and differentiated toward erythroblasts in vitro. Patient and healthy cells were harvested on day 6 and day 12 and jointly processed via mtscATAC-seq or scRNA-seq. f, Stacked bar graph of cells annotated as wildtype or del7q across indicated cell populations, including at day 6 and day 12 of in vitro culture. g, Same as f but showing the proportion of cells with exactly 0% and >0% heteroplasmy of the mtDNA deletion as determined by mgatk-del. h, Cumulative distribution graphs of mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy across the indicated four cell populations. i–k, UMAP embedding of 28,783 high-quality cells profiled via scRNA-seq annotated by (i) day of culture collected, (j) healthy or disease state and (k) annotated cell state/cluster. l, Rank-sorted differentially expressed genes across erythroid populations. Selected top genes overexpressed and downregulated in PS are annotated. Black dots (n = 6,577) represent statistically significant genes at a Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold of <0.01. m, Volcano plot of pathway enrichment analysis results via erythroid differential gene expression comparisons of the PS to healthy control cells. Selected top pathways are annotated. The dotted line represents the threshold for consideration at an FDR < 0.1. n, Schematic overview of altered (metabolic) genes and pathways in PS relative to the healthy status. Genes and pathways upregulated in PS are shown in red and when downregulated shown in blue. Note—not all biochemical steps necessarily take place in mitochondria and the schematic has been simplified for illustrative purposes.

To further corroborate the observed in vivo phenotypes, we differentiated PT3 BMMNCs and healthy control cells in vitro in the presence of erythropoietin (EPO), collecting cells at days 6 and 12 of culture, before processing with scRNA-seq and mtscATAC-seq (Fig. 7e). Phenotypically, PS cells displayed poor proliferation and clear signs of impairment during erythroid differentiation as assessed by surface markers and cytology (Extended Data Fig. 6b–d). Assessment of mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy and del7q status revealed a relative increase in the proportion of del7q cells at days 6 and 12, with no notable selection against mtDNA heteroplasmy (Fig. 7c–h). These results, however, may reflect a low abundance of late-stage erythroblasts at the sampled time points.

Finally, we investigated the altered gene expression programs that may underlie the anemic phenotype in PS. We performed unsupervised dimension reduction of 28,783 high-quality cells, which revealed a trajectory of erythroid differentiation (Fig. 7i–k and Extended Data Fig. 6e; Methods). Differential gene expression and pathway enrichment analyses comparing erythroid cells from the PS donor to the healthy control were robust despite MDS-associated cells, suggesting alterations to be primarily attributable to the mtDNA deletion (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Most notably, we observed genes of the serine and glycine biosynthesis pathway, including PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH and SHMT2 to be upregulated in PS erythroblasts (Fig. 7l,m). Serine metabolism, reported to be altered in response to mitochondrial dysfunction, may aid in maintaining cellular one-carbon availability to provide essential precursors for synthesizing urines, phospholipids and the antioxidant glutathione (GSH), a scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS)32–34. Conversely, the heme biosynthesis pathway, including genes UROS, CPOX, FECH, UROD, HMBS and PPOX, and cholesterol biosynthesis pathways were substantially downregulated in PS (Fig. 7l,m and Extended Data Fig. 6g–i). In total, our multi-omic analyses nominate numerous perturbed genes and pathways, the deregulation of which likely contributes to the characteristic anemia in PS (Fig. 7n), and suggests avenues for additional functional follow-up.

Discussion

Multi-omic approaches provide complementary and orthogonal measurements to more holistically characterize the cellular circuits underlying perturbed cellular phenotypes in disease35,36. Here we charted genomic alterations across five modalities (that is, transcriptome, accessible chromatin, cell-surface markers, mtDNA genotypes and nuclear chromosomal aberrations) resulting from large mtDNA deletions across ~200,000 primary patient cells. In particular, we demonstrate how mgatk-del in conjunction with mtscATAC-seq9,10, ASAP-seq11 or DOGMA-seq (Supplementary Note)11 enables the sensitive identification and quantification of large mtDNA deletions in single cells, alongside concomitant readouts of cell state. MtDNA copy number and heteroplasmy can be present at highly variable levels across a population of cells and cell states, thereby emphasizing the utility of our multi-omic advances. Our approach will aid in studying the phenotypic effects of somatically arising mtDNA mutations, which may be selected against in individuals with cancer, aging-related degenerative diseases and healthy tissues1,2,37–39. We note reports of the accumulation of mtDNA deletions in postmitotic cells, including in single muscle fibers40 and neurons in Parkinson’s disease41, whereas SNVs appear more common in mitotic cells42, indicative of distinct evolutionary pressures underlying these two classes of mutations. Future studies at the single mitochondrion level43 or that study the full mtDNA or RNA molecule via long-read sequencing technologies39 will complement our cell state inferences of heteroplasmy.

By studying pathogenic mtDNA deletion dynamics in vivo and in vitro, we observed multiple instances of purifying selection, including in MAIT, CD8.TEM and RTEs, indicative of metabolic vulnerabilities at distinct stages of T-cell maturation. Notably, we observed that CD8. TEMs are more sensitive to selection compared to their effector CD4. TCM counterparts, corroborating distinct mitochondrial/metabolic demand following TCR-specific activation and conversion of CD8+ T cells to effector/memory cells44. Such a model is consistent with mitochondrial respiratory capacity to be a critical regulator of CD8 memory T-cell development45. Furthermore, our approach also allowed the characterization of rare populations of cells, including MAIT, which experienced similar strong selection pressures to CD8.TEM, presumably requiring efficient mitochondrial capacity for cellular differentiation and function46,47. Together, these results provide insights into our emerging understanding of the effects of pathogenic mtDNA on the development of T-cell states and their life-long dynamics across the hematopoietic compartment (Fig. 4). Furthermore, through a rare case of PS with MDS, we show the del7q alteration to be restricted to cells carrying the mtDNA deletion, indicating that it arose in a mitochondrially/metabolically dysfunctional background and was coincidental with an expanded myeloid pool and reduction of the phenotypic HSC pool. While profiling additional patients is required to verify selection dynamics in HSPCs, our observation of purifying selection in progenitor cells in the bone marrow compartment explains pan-lineage purifying selection across all mitochondriopathies studied herein.

Leveraging in vivo pseudotime trajectory analysis and in vitro models, we further assessed genomic and mtDNA features during erythroid differentiation to study the anemia characteristic of PS (Fig. 7). Our data suggest that serine/glycine biosynthesis is upregulated in PS cells to maintain DNA production and other critical components of the cell in states of mitochondrial dysfunction48–50. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism appears to be less sensitive to product inhibition by increased NADH:NAD+ ratios, which are associated with mtDNA-related diseases due to an impaired electron transport chain34. These downstream perturbations may contribute to the downregulation of heme biosynthesis51, which is necessary for adequate hemoglobin production during red blood cell generation52. We hypothesize that glycine may be redirected to synthesize one-carbon precursors for DNA replication in highly proliferative erythroblasts and/or GSH to scavenge increased ROS levels resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction. Correspondingly, we observed the downregulation of heme biosynthesis genes, which may lead to excess iron accumulation and granular depositions, ultimately forming characteristic sideroblastic cells in PS.

In sum, our multi-omic methods revealed unique genomic alterations in response to pathogenic mtDNA in distinct cellular compartments throughout the hematopoietic system. While mitochondria are ubiquitous, they nevertheless fulfill distinct roles depending on cell type and cell state. This emphasizes the need to ideally study patient-derived cellular specimens to fully capture alterations resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction attributable to germline or somatic mtDNA mutations. In this light, we demonstrate how comprehensive single-cell multi-omic approaches provide biologically important insights into the molecular alterations of primary mitochondrial defects.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01433-8.

Methods

Our research complies with all relevant ethical and regulatory guidance, including the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital, ethics approval from Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, and a research agreement with the North American Mitochondrial Disease Consortium (NAMDC).

Cell lines and cell culture

Biological samples for cell lines were procured under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital, after obtaining written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PS fibroblasts were derived from the patient bone marrow (PS1 and PS2) or skin (PS3). Control fibroblasts were derived from healthy donors’ skin (Control 1 and Control 2). All fibroblasts were grown in DMEM containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine, nonessential amino acid and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2).

Healthy donor and patient samples

Primary human peripheral blood and bone marrow samples were collected under Institutional Review Board-approved protocols and with written informed consent for genomic sequencing. Primary hematopoietic samples were collected from three previously diagnosed patients, including a 7-year-old male with PS/KSS (‘PT1’), a 4-year-old female with PS (‘PT2’) and a 4-year-old male with PS and del7q MDS (‘PT3’). Peripheral blood and BMMNCs were isolated using Ficoll Paque Plus solution and density gradient centrifugation using SepMate tubes (StemCell Technologies). PBMCs from adult female donors (‘KSS1’, ‘KSS2’ and ‘CPEO1’) were obtained in collaboration with NAMDC53. Both donors with KSS presented with pigmentary retinopathy and various neurological symptoms, as KSS1 was diagnosed with hearing loss and KSS2 was diagnosed with ataxia and dementia over the disease course. There were limited relevant clinical annotations for CPEO1. None of the patients had defined postmitotic heteroplasmy levels following the diagnosis available in the NAMDC records. All PBMC samples were stored in vapor-phase liquid nitrogen after cryopreservation with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide until analysis.

Healthy donor BMMNCs were obtained from StemCell Technologies. Healthy adult CD34+ HSPCs were obtained from the Fred Hutchinson Hematopoietic Cell Processing and Repository. The CD34+ samples were de-identified, and approval for use of these samples for research purposes was provided by the Institutional Review Board and Biosafety Committees at Boston Children’s Hospital. For healthy pediatric controls for the differential gene expression analyses and T-cell culture experiments, pseudonymized samples from bone marrow donors of 5 (‘Ped1’) and 14 (‘Ped2’) years of age were obtained at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, following approval of the local ethics commission (EA2/144/15). Informed consent was obtained from parents/legal guardians for all pediatric material.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessments. All custom codes used to replicate analyses are available as part of the code availability.

Human T-cell activation cultures

PBMCs or isolated T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin and streptomycin, as well as 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 (PeproTech) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were in vitro activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody (5 μg ml−1, clone OKT3, BioLegend) plus soluble anti-CD28 antibody (1 μg ml−1, clone 28.2; BioLegend, 302901). Upon thawing (defined as ‘day 0’), cells were resuspended at a concentration of ~106 cells per ml in culture medium plus anti-CD28 antibody, and ~150,000 cells were plated into 96-well plates precoated with anti-CD3 antibody. After 48 h of activation (defined as ‘day 2’), cells were transferred into uncoated plates and maintained at a density of 1–2 × 106 cells per ml. Cell counts were determined every 2–3 d.

The following culturing conditions were used for the proliferation assay: RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 2 mM stable glutamine, 10% FBS, penicillin and streptomycin, as well as 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 (PeproTech) with or without the presence of 1 mM pyruvate and 200 nM uridine at 37 °C and 5% CO2. PBMCs were labeled with CellTrace Violet (2.5 μM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, C34557) before activation according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Cell proliferation was measured on day 4 after activation as measured by the dilution of CellTrace Violet upon activation. In vitro activated T cells were stained using 1:100 AF488-conjugated CD3 (clone OKT3; BioLegend, 317310), 1:100 PE-conjugated CD4 (clone PRA-T4; BioLegend, 300508), 1:100 APC-conjugated CD8 (clone SK1; BioLegend, 344721), 1:100 BV785-conjugated CD45RA (clone HI100; BioLegend, 304139) and 1:2,000 Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience, 65–0865-18).

Human erythroid in vitro cell culture

BMMNCs or CD34+ HSPCs from healthy donors or PT3 were differentiated into mature erythroid cells using a three-phase culture protocol54,55. Cells used for scRNA-seq and mtscATAC-seq experiments were derived from two independent cultures using PT3 cells, but two different healthy control donors were used for each culture. In phase 1 (days 0–7), cells were cultured at a density of 105–106 cells per ml in IMDM supplemented with 2% human AB plasma, 3% human AB serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 3 IU ml−1 heparin, 10 μg ml−1 insulin, 200 μg ml−1 holo-transferrin, 1 IU EPO, 10 ng ml−1 stem cell factor and 1 ng ml−1 IL-3. In phase 2 (days 7–12), IL-3 was omitted from the medium. In phase 3 (days 12–18), cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 106 cells per ml, with both IL-3 and SCF omitted from the medium, and the holo-transferrin concentration was increased to 1 mg ml−1. Cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting

For flow cytometry analysis and sorting, cells were washed with FACS buffer (1% FBS in PBS) before antibody staining. In vitro cultured primary erythroid cells were stained using 1:50 APC-conjugated CD235a (glycophorin A, clone HIR2; eBioscience, 50–153-69) and 1:50 FITC-conjugated CD71 (clone OKT9; eBioscience, 14–0719-82) for 15 min on ice. PT3 bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells were stained using 1:40 APC-conjugated CD34 (clone 581; BioLegend, 343509). In vitro activated T cells were stained using 1:200 AF488-conjugated CD3 (clone OKT3; BioLegend, 317310), 1:200 PE-conjugated CD4 (clone PRA-T4; BioLegend, 300508), 1:100 APC-conjugated CD8 (clone SK1; BioLegend, 344721), 1:200 PE-Cy7-conjugated CD45RO (clone UCHL1; BioLegend, 304229), 1:200 BV785-conjugated CD45RA (clone HI100; BioLegend, 304139), 1:50 BV605-conjugated CCR7 (clone G043H7; BioLegend, 353223) and 1:50 APC-H7-conjugated CD27 (clone MT271; BD Bioscience, 560223). For mtscATAC-seq and ASAP-seq experiments, residual granulocytes were excluded by staining cells using 1:50 PE-conjugated CD66b (clone G10F5; BioLegend, 305102). For live/dead cell discrimination, Sytox Blue was used at a 1:1,000 dilution according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, S34857). FACS analysis was conducted on BD Bioscience Fortessa flow cytometers at the Whitehead Institute Flow Cytometry Core and at the Berlin Institute of Health and Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology. Cell sorting was conducted using the Sony SH800 sorter with a 100-μm chip at the Broad Institute Flow Cytometry Facility. The data were analyzed using the FlowJo software v10.4.2.

May–Grünwald-Giemsa staining

Harvested cells were washed once at 300g for 5 min, resuspended in 200 μl of FACS buffer and spun onto poly-L-lysine-coated microscope slides with a Shandon 4 (ThermoFisher Scientific) cytocentrifuge at 300 rpm for 4 min. Visibly dry slides were transferred into the May–Grünwald solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min, rinsed four times every 30 s in water and transferred to Giemsa solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. Slides were washed as described previously, dry mounted with coverslips and examined. All images shown were taken using a Metafer slide scanning platform and software (Metasystems) at 63× magnification.

Mitochondrial single-cell ATAC-seq (mtscATAC-seq)

MtscATAC-seq libraries were generated using the 10× Chromium Controller and the Chromium Single Cell ATAC Library & Gel Bead Kit (1000111) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (CG000169-Rev C and CG000168-Rev B) as outlined below and previously described to increase mtDNA yield and genome coverage9. Briefly, 1.5 ml or 2 ml DNA LoBind tubes (Eppendorf) were used to wash cells in PBS and downstream processing steps. After washing, cells were fixed in 0.1 or 1% formaldehyde (FA; ThermoFisher Scientific, 28906) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, quenched with glycine solution to a final concentration of 0.125 M and washed twice in PBS via centrifugation at 400g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were subsequently treated with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCL, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP40 and 1% BSA) for 3 min for primary cells and 5 min for cell lines on the ice, followed by addition of 1 ml of chilled wash buffer and inversion (10 mM Tris–HCL, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and 1% BSA) before centrifugation at 500g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and cells were diluted in 1× diluted nuclei buffer (10× Genomics) before counting using trypan blue and a Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter. If large cell clumps were observed, a 40-μm Flowmi cell strainer was used before processing cells according to the Chromium Single Cell ATAC Solution user guide with no additional modifications. Briefly, after tagmentation, the cells were loaded on a Chromium Controller Single-Cell Instrument to generate single-cell gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs), followed by linear PCR, as described in the protocol using a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with 96-Deep Well Reaction Module (BioRad). After breaking the GEMs, the barcoded tagmented DNA was purified and further amplified to enable sample indexing and enrichment of scATAC-seq libraries. All genomic libraries were quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and a high-sensitivity DNA chip run on a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent).

ATAC with selected antigen profiling by sequencing (ASAP-seq)

PT3-derived BMMNCs were stained with a 242 TSA-conjugated antibody panel (BioLegend; Supplementary Table 3 for a list of antibodies, clones and barcodes used for ASAP-seq) as previously described11. To enable flow cytometry-based enrichment of CD34+ cells, the sample was co-stained using an APC-conjugated CD34 (clone 581; BioLegend, 343509) to sort live CD66b-CD34+ and otherwise CD66b-BMMNCs, which were then pooled after sorting and processed for ASAP-seq as previously described11 and outlined online at https://cite-seq.com/asapseq/. Briefly, following sorting, cells were fixed in 1% FA and processed as described for the mtscATAC-seq workflow described previously, with the modification that during the barcoding reaction, 0.5 μl of 1 μM bridge oligo A (BOA for TSA) was added to the barcoding mix. Silane bead elution and SPRI cleanup steps were modified as described to generate the indexed protein tag library11.

scRNA-seq

scRNA-seq libraries were generated using the 10× Genomics Chromium Controller and the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library Construction Kit v2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the suspended cells were loaded on a Chromium Controller Single-Cell Instrument to generate single-cell GEMs, followed by reverse transcription and sample indexing using a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with 96-Deep Well Reaction Module (BioRad). After breaking the GEMs, the barcoded cDNA was purified and amplified, followed by fragmenting, A-tailing and ligation with adaptors. Finally, PCR amplification was performed to enable sample indexing and enrichment of scRNA-Seq libraries.

10x Genomics multiome

Single-cell multiome libraries of healthy pediatric control PBMCs were generated using the 10× Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression reagent bundle (100285) and the Chromium controller according to the manufacturer’s instructions (CG000338-Rev E). Briefly, following the sorting of live and CD66b-negative cells, 1.5 ml DNA LoBind tubes (Eppendorf) were used to wash cells in PBS and for downstream processing steps. After washing, cells were lysed for 3 min in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCL, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% NP40, 0.01% digitonin, 1% BSA, 1 mM DTT and 1 U μl−1 RNase inhibitor). Following lysis, cells were washed three times with 1 ml wash buffer (10 mM Tris–HCL, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT and 1 U μl−1 RNase inhibitor) before centrifugation at 500g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and cells were diluted in 1× diluted nuclei buffer (10× Genomics) before counting using trypan blue and a Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter. If large cell clumps were observed, a 40-μm Flowmi cell strainer was used before processing cells according to the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression user guide with no further modifications. Briefly, after transposition and chip loading, the cells were loaded into the Chromium Controller instrument to generate single-cell GEMs, followed by incubation as described in the protocol using a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with 96-Deep Well Reaction Module (BioRad). After breaking the GEMs, the barcoded DNA was purified and further amplified before separate ATAC and cDNA library construction. For the ATAC part, the purified DNA was further amplified to enable sample indexing and enrichment of the DNA. The cDNA was further amplified, purified and quantified using a high-sensitivity DNA chip run on a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent). The cDNA was subsequently fragmented, PCR-amplified and purified as depicted in the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression user guide with no further modifications.

DOGMA-seq

For Pearson PT1, PBMCs were processed with DOGMA-seq as described previously11. Briefly, PBMCs were stained with total-seq A antibody panels (TotalSeq-A Human Universal Cocktail, v1.0; BioLegend, 399907; no dilution), PE-conjugated CD66b and Sytox Blue, and dead and CD66b+ cells were removed via sorting. Sorted live cells were fixed at 0.1% FA for 5 min at room temperature, and subsequent lysis/permeabilization steps were analogous to the multiome protocol except for Tween-20, and digitonin was omitted from the lysis and wash buffers. Permeabilized cells were then processed as described for the multiome workflow above with the modification of adding 1 μl of 0.2 μM antibody-derived tag (ADT) additive primer (CCTTGGCACCCGAGAATT*C*C). After SPRI cleanup of the preamplification PCR product, the beads were eluted in 100 μl of EB buffer. Notably, 25 μl of the eluate were used for ATAC-seq library processing, and 35 μl were each used as input for cDNA and antibody tag amplification11, respectively. Libraries for MAS-ISO-seq were constructed using the cDNA from the RNA modality as previously described56. While the MAS-ISO-seq libraries were of high quality, the low mtRNA capture in the DOGMA-seq assay limited further analysis as we detected less than one fusion or relevant wild-type mtRNA per cell from these libraries (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, we note the fixation step as part of the DOGMA-seq workflow that reduces the average cDNA fragment size.

Sequencing

All libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq550 and NovaSeq6000 sequencing platforms. 10× Genomics scATAC-seq and ASAP-seq libraries were sequenced with paired-end reads (2 × 72 cycles). 10× Genomics multiome and 3′ scRNA-seq libraries were sequenced as recommended by the manufacturer. For DOGMA-seq and in vitro T-cell stimulation libraries (Fig. 3), libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq6000 platform with a 2 × 150 bp of 2 × 100 paired-end read configuration, which were trimmed to be 2 × 72 cycles for compatibility with the optimized deletion calling workflow originally implemented on the NextSeq. MAS-ISO-seq libraries were sequenced using two SMRT cells using the PacBio Sequel II as previously described56. Both cells yielded >30 M reads, and >99% of reads had a valid barcode and UMI from the 10× multiome/DOGMA-seq design.

mtDNA deletion calling and heteroplasmy estimation in single cells

Although large mtDNA deletions have been well-documented in a variety of next-generation sequencing datasets, we observed that coordinates associated with deletions (for example, the ‘common’ deletion) may be incorrect at base-pair resolution. These differences are primarily due to differences in the coordinates of the mitochondrial reference genome and variations in the results of sequencing read alignment tools, particularly near homomorphic sequences at deletion junctions. Thus, we recommend using the sequencing data from the particular sequencing experiment to identify the deletion junction within the primary sequencing data that is being analyzed. As part of our software solution, mgatk-del in ‘find’ mode takes a.bam file and compiles a list of key summary statistics, including the number of clipped reads per position, secondary alignment bases and overall coverage, to identify deletions. The outputs of mgatk-del find include plots (for example, Extended Data Fig. 1b) and tables that facilitate identifying the specific base pairs associated with the mtDNA deletions.

After the precise breakpoints have been determined, single-cell mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy can be estimated using the second step in the mgatk-del pipeline. Here PCR-deduplicated single-cell bam files (emitted as intermediate output in the standard mgatk pipeline) serve as the primary input, yielding an estimation of mtDNA deletion heteroplasmy per user-specified deletion. This metric is determined by using the ratio of reads overlapping the deletion junction that either support (via clip) or provide no evidence of the deletion (contiguous alignment over the read window, as depicted in Fig. 1c,d). Notably, each paired-end read contributes only once to the heteroplasmy metric. As a comparison, coverage-based heteroplasmy (Fig. 1e) was estimated via one minus the ratio of mean per-base coverage within the deleted region over the mean per-base coverage outside the deleted region. For negative values (when the within-deleted region coverage exceeded that of the outside region), values were adjusted to 0% heteroplasmy for display purposes (coverage-based heteroplasmy was not used in any downstream analyses).

To generate simulated sequencing datasets and to benchmark this approach, we used the wgsim tool from within samtools57 to generate paired-end reads of length 72 bp (same length as for our mtscATAC-seq data), 50 bp or 100 bp, which represent common sequencing configurations. Sequencing reads were simulated from either the revised Cambridge reference sequence (rCRS) or a synthetic mtDNA chromosome that encoded the specified deletion. Simulated sequencing reads were then aligned to the masked reference genome used by CellRanger-ATAC, and the resulting aligned reads from the.bam files were mixed in specific ratios (ten mixtures per deletion) to specify the true heteroplasmy for the given simulation. The estimated heteroplasmy was computed by running the function used in mgatk-del with the search space of possible values in the outer-param and inner-param and then the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) was computed based on the difference. In total, 22 mtDNA deletions were considered, which represented a curated list of the six deletions in our study and 16 additional deletions that were curated from MITOMAP58. The default parameters in mgatk-del (outer-param, 9; inner-param, 24) represent values that performed consistently well across a variety of deletions and read lengths. We suggest that mgatk-del can produce reasonable single-cell heteroplasmy estimations from the default parameters. Specifically, we observed a mean 0.93% RMSE difference between default and optimal hyperparameter values across our six PS mtDNA deletions in the cell lines and primary cells. Thus, we suggest that a grid search to determine optimal hyperparameters for accurate heteroplasmy estimation may be useful but typically unnecessary for new datasets.

To quantify that the variance in heteroplasmy was attributable to variation in coverage per single cell (Extended Data Figs. 1g and 2c), the overall mean per comparison was computed, and a permuted heteroplasmy was simulated using the rbinom() function with the overall heteroplasmy and per-cell coverage as inputs. The observed (true data) and null (output of rbinom simulation) are shown for each comparison. To assess the sensitivity and specificity of the heteroplasmy estimation, a threshold of 1% was used for ‘detection of deletion’ (Extended Data Fig. 1i). For further validation of heteroplasmy estimation as a function of coverage, we used the simulated reads from the wgsim alignments to synthetically create cells with a predetermined heteroplasmy at 15 variable coverages between 10× and 500× coverage (Extended Data Fig. 1j) and subsequently estimated heteroplasmy with the core function in the mgatk-del workflow. Per deletion, we simulated 100 cells and averaged the mean absolute error to quantify the bias associated with the mgatk-del coverage estimates from both coverage and clipped heteroplasmy. Collectively, our benchmarking and simulation analysis indicates that for specific inference near 0%, clipped-read-based heteroplasmy performs better, whereas coverage-based heteroplasmy (once base-pair resolution junctions are inferred) can produce more accurate absolute heteroplasmy estimates, particularly in lower coverage settings, including the DOGMA-seq data shown here. For this study, we consistently use the clipped-read base estimates from mtscATAC-seq data to both accurately infer purifying selection in varied populations and as the mean coverage of our mtscATAC-seq profiles was 81.5×. Full details of the simulations, including code for reproducibility, and additional discussion of the methods are available as part of our online resources.

scATAC-seq analyses

Raw-sequencing data were demultiplexed using CellRanger-ATAC mkfastq. Demultiplexed sequencing reads for all libraries were aligned to the mtDNA blacklist modified9 hg38 reference genome using CellRanger-ATAC count v2. Deletions in mtDNA were identified per patient library and heteroplasmy was quantified using the exact breakpoints as discussed in the previous section. Downstream analyses of the three PS donors and one healthy donor previously profiled with mtscATAC-seq9 were performed after identifying cells with a minimum depth of 10× on mtDNA, 1000 ATAC fragments passing filters and 45% of fragments in accessibility peaks from an aggregated peak set. Latent semantic indexing (LSI) was performed, and the 2–30 components were adjusted for donor effects using harmony before producing a two-dimensional embedding and clustering using the harmony components59. Gene activity scores were computed and normalized using the Signac workflow60. For PBMC cell-type annotations, granular cell-type labels and UMAP coordinates were derived by using the Seurat Dictionary Learning16 for cross-modality integration. We used Azimuth CITE-seq reference dataset labels61 with public 10× genomics multiome RNA- and ATAC-seq PBMC data as a cross-modality bridge. Libraries for the MELAS donors10 were reprocessed with the hg38 scATAC-seq reference and consistently projected using the Seurat reference. Libraries for the CPEO and KSS donors were processed consistently as well, and the base-pair resolution for the deletions was inferred from the ‘_del_ find.clip.tsv’ file from mgatk-del-find. For all deletions, the top clipped base pairs were called deletions in Fig. 4 from this analysis. Statistical comparisons of the extent of purifying selection (for example, Fig. 2 cumulative distribution plots) were computed based on the proportion of cells with less than 1% heteroplasmy using a two-sided proportion test in R. The uncorrected P values are shown in each panel.

scRNA-seq analyses

PS cell-derived 10× 3′ scRNA-seq sequencing libraries were demultiplexed and aligned to the hg38 reference with CellRanger v3.0.2. Healthy PBMC datasets were augmented from the public resource of 10× single-cell gene expression. Raw-sequencing reads from two libraries (pbmc4k and pbmc8k) of 10× 3′ v2 chemistry were downloaded and reprocessed consistent with the PS cell libraries. Filtered count matrices from the two 10× 3′ v3 chemistries (pbmc5k and NextGEM) were downloaded from the online resource as they were already aligned to the same reference as the rest of the PS data. We note that the pairs of libraries from each technology were derived from the same biological donor (‘H1’ for v2 libraries; ‘H2’ for v3 libraries). Separately, scRNA-seq libraries (‘Ped1’ and ‘Ped2’) from the two pediatric donors were aligned to the same hg38 reference and aggregated at the counts-matrix level as the reference transcriptome used for quantification was identical between the libraries.

Using the filtered gene by cell count matrices for all scRNA-seq libraries, we identified and removed putative cell doublets using scrublet62 with the default parameters and specified a 5% expected doublet rate. Barcodes identified as cell doublets were then filtered. Next, we performed data integration across these seven libraries for the PBMC reference projection via Azimuth via Seurat v4. Differential gene expression summary statistics from scRNA-seq libraries were computed using edgeR (v3.16.0)63 while adjusting for the scaled number of genes detected per cell (edgeRQLFDetRate64). We note that while edgeR was originally introduced for bulk RNA-seq, a comparison of differential expression tools demonstrated good performance for this approach compared to other bulk and single-cell strategies64. We performed gene-set enrichment analyses with the Panther Pathway enrichments using the WebGestalt v2019 framework65 using a rank ordering of genes by the signed z score (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Bulk expression data from GTEx were curated from the GTEx online portal for the indicated genes66. All other visualizations and analyses for scRNA-seq data were performed using the Seurat framework. Gene module score analyses, including for the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, heme biosynthesis pathway and glycolysis, were performed using gene sets from the PANTHER dataset accessed via WebGestalt65 and computed using the AddModuleScore in Seurat using the default parameters. For the comparison of within and between donor/state heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. 3), we considered six major cell types with an ample number of cells from our reference projection annotation. After computing a principal component space using the Seurat defaults for all cells, we randomly subsampled 100 cells within each condition to make comparisons within or between groups. The boxplots in the figure represent the cell–cell distances from all comparisons for ten simulation iterations.

DOGMA-seq analyses

For the DOGMA-seq antibody tag data, per-cell and per-antibody tag counts were enumerated via the kite | kallisto | bustools framework accounting for unique bridging events as previously described11,67. Cells called by the CellRanger-arc knee call were filtered based on the abundance of protein (>50 unique molecules), minimal nonspecific antibody binding (<10 molecules associated with isotype control antibodies), total accessible chromatin (>1,000 nuclear fragments), >50% fragments in accessibility peaks and total gene expression (>1,000 UMIs per cell and >500 genes detected per cells), following our prior quality control of cells from DOGMA-seq for use in the 3WNN analyses (Extended Data Fig. 2)11. For consistency with other analyses, we used the Seurat reference projection of our dataset with the RNA modality for the DOGMA-seq data and corroborated the cell state classification by performing the same project using the ATAC modality. For comparison of heteroplasmy, we required either a minimum of 10× total coverage for a coverage-based heteroplasmy estimation or a minimum of ten reads supporting or refuting the deletion for clipped-based heteroplasmy inference (Extended Data Fig. 2f). For the long-rad PacBio sequencing, raw molecules were processed using the standard manufacturer’s workflow into full cDNA molecules in the format of unmapped.bam files. Deleted molecules or wild-type molecules from the MAS-ISO-seq libraries were inferred using the base-pair resolution deletion junctions for PT1 between COX1 and ND5 or the wild-type sequences of a full gene to derive unique 16-mers (8 bp on either side of the deletion junction), which we determined empirically to be unique strings in the human reference genome for PT1. To quantify heteroplasmy, we filtered reads for a valid barcode and UMI then parsed the full molecules for these unique 16-mers after validating that there were no detectable levels of the deletion junction in other healthy control samples.

Chromosome 7 copy number (deletion) analysis

del7q analyses were performed only for PT3 as the other patients showed no evidence of copy number alterations (either from cytogenetics or sequencing data). To assign cells as either wild-type or del7q, we performed copy number analyses of the accessible chromatin (scATAC-seq) data for all libraries and cells profiled from PT3. From the cytogenetics and sequencing data, we estimated the positions 110,000,000 (on chromosome 7q22) as the approximate break point and computed the fraction of fragments occurring after this coordinate to get an estimate of the copy number changes across the different libraries (shown in Fig. 5b). To call the single-cell del7q status, we used CONICS68 on the gene activity matrix and specified a custom region spanning the deletion for estimation of the copy number. Because the del7q abundance varied between biological sources (for example, PBMCs and CD34+ cells) and resulted in different maximum-likelihood estimates for the Gaussian distribution parameters, wild-type or single-cell del7q genotype per cell was called using a manual threshold of the predicted probability of the two-component mixture model based on the density of the first component’s predicted probability. Explicitly, the thresholds used were 0.5 for the CD34+ data (Fig. 5), 0.3 for the ASAP BMMNC dataset (Fig. 6) and 0.3 for the erythroid differentiation dataset (Fig. 7).

Bone marrow ASAP-seq analyses

For the ASAP-seq antibody tag data, per-cell and per-antibody tag counts were enumerated via the kite | kallisto | bustools framework, accounting for unique bridging events as previously described11,67. Cells called by the CellRanger-ATAC knee call were filtered based on the abundance of protein (>150 unique molecules) and accessible chromatin (>1,000 nuclear fragments) as well as accessible chromatin enrichment (>25% fragments in accessibility peaks) and minimal nonspecific antibody binding (<10 molecules associated with isotype control antibodies). Dimensionality reduction and clustering were performed only using the chromatin accessibility modality of the ASAP-seq, and protein expression and gene activity values were used to annotate clusters as previously described11. Differential protein and gene activity score calculations (via Signac60) were performed using the FindMarkers function in Seurat. Somatic mtDNA mutations were identified by running mgatk on the ASAP-seq cells, exceeding a mean 20× coverage using the default parameters9. For CD34+ analysis and projections (Fig. 6d–g), we used the LSI reference projection and reference CD34+ landscape as previously described23. For the erythroid pseudotime trajectory (Fig. 7a–d), we used a semi-supervised trajectory inference previously introduced69,70 connecting the annotated multipotent progenitor populations to the committed erythroid population. Single-cell pseudotime was estimated using the projection of each cell along the axis joined between the per-cluster centroids.

Erythroid single-cell analyses

Raw-sequencing data were demultiplexed and aligned using CellRanger and CellRanger-ATAC as done for the PBMC analyses. To minimize batch effects, PS and healthy cells were pooled for single-cell processing and then computationally deconvolved using donor-specific SNPs. Differential gene expression, via edgeR (v3.16.0)63, and pathway enrichment (Panther Pathway enrichments using the WebGestalt framework65) were conducted using the same workflow as the PBMC data. We computed a per-cell erythroid module score using 99 genes (for example, GATA1, ALAS2 and HBB) highly upregulated in erythropoiesis from our previous bulk transcriptomic atlas of cells from this in vitro system31 using the AddModuleScore function in Seurat with the default parameters.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Deletion and heteroplasmy estimation using mgatk-del.

(a) Schematic of mgatk-del pipeline, which utilizes the outputs of CellRanger-ATAC. Two critical steps of base-resolution deletion calling (‘find’) and estimation of single-cell heteroplasmy (‘quantify’) are illustrated. (b) Output of mgatk-del ‘find’ for Pearson syndrome deletion 1 (PS1). The red vertical lines represent the called deletion breakpoints where the regions were joined (blue arc) via a secondary alignment (‘SA’ tag in.bam file). (c) Schematic of the simulation framework. Synthetic cells with known heteroplasmy were generated via mixtures of reference and PS mtDNA for all previously reported deletions. (d) Summary of results from a 50% mix showing the heteroplasmy as estimated from the ratio of clipped to unclipped reads. Parameters ‘innerparam’ and ‘outer-param’ define the number of bases that are discarded on the read when estimating the overall heteroplasmy per cell. (e) Results of exhaustive simulation for three mtDNA deletions used in the cell mixing experiment. The minimum value of the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the estimated and true heteroplasmy is noted with an asterisk over the grid search. (f) Difference in mean estimated heteroplasmy (RMSE) in optimal and default parameters across a variety of settings indicating the stability. (g) Decomposition of variance using a permuted model. Black shows the observed variance whereas green shows the spread under a permuted (null) model. The percent of the variance explained by this null model is shown. (h) Single-cell correlation of clipped (Fig. 1d) versus coverage-based (Fig. 1e) heteroplasmy estimates for valid deletions per indicated deletion/donor. The Pearson correlation for the three deletions is indicated. (i) % of cells with non-zero heteroplasmy for different deletions at different coverages using indicated methods. The left panel assesses sensitivity where the true proportion of cells with the deletion is 100%. The right panel assesses specificity where the true proportion of cells with the deletion is 0%. For both plots, detection of the deletion requires ≥1% heteroplasmy. ( j) The mean absolute error in heteroplasmy at 50x coverage is indicated by the value shown on the graph for two methods of heteroplasmy estimation, as in (i).

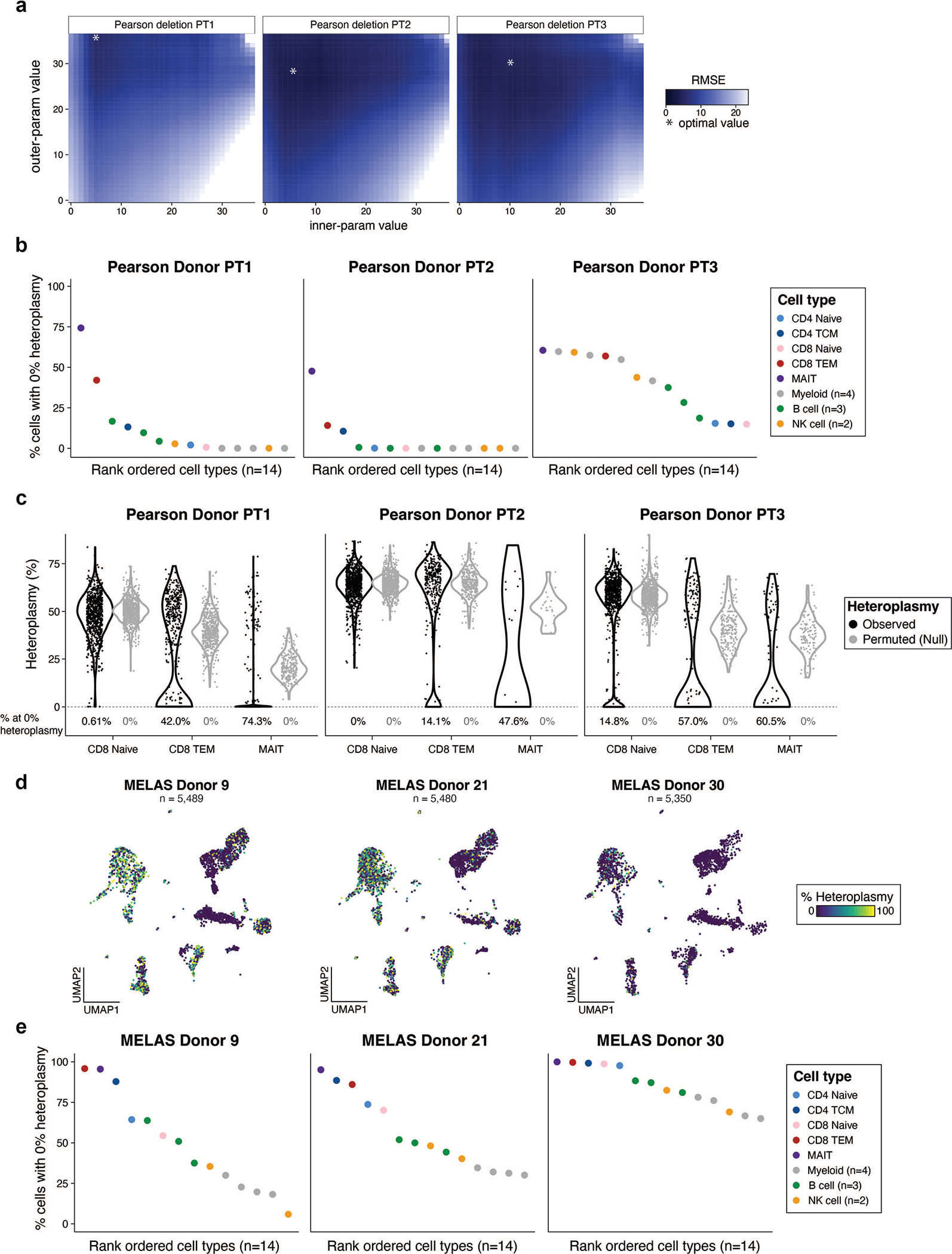

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Supporting information for PS PBMC mtscATAC-seq analyses.

(a) Result of mgatk-del hyperparameter optimization via a simulation framework. The minimum value of the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the estimated and true heteroplasmy is noted with an asterisk over the grid search. (b) Summary of % of cells with 0% heteroplasmy across all hematopoietic cells for the three PS donors. (c) Violin plots of each respective mtDNA deletion for all three patients in selected T cell populations. Black indicates the observed data. Gray represents heteroplasmy under a null model of one mean and the variation attributed to differences in coverage per cell. CD8.TEM and MAIT cells have a bimodal distribution (indicating purifying selection) whereas CD8+ naive cells have a distribution that is more consistent with a single mode of heteroplasmy. The percentage of cells with 0% heteroplasmy under observed and null settings are noted for each population below the violins. (d) UMAP visualization of MELAS bridge reference projection across three donors previously reported. (e) Summary of % of cells with 0% heteroplasmy across all hematopoietic cells for the three MELAS donors10 with refined cell type annotations from the bridge reference projection.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Supporting analyses for primary PS T cell cultures.