Abstract

Ensuring site-selectivity in covalent chemical modification of proteins is one of the major challenges in chemical biology and related biomedical disciplines. Most current strategies either utilize the selectivity of proteases, or are based on reactions involving the thiol groups of cysteine residues. We have modified a pair of heterodimeric coiled-coil peptides to enable the selective covalent stabilization of the dimer without using enzymes or cysteine moieties. Fusion of one peptide to the protein of interest, in combination with linking the desired chemical modification to the complementary peptide, facilitates stable, regio-selective attachment of the chemical moiety to the protein, through the formation of the covalently stabilized coiled-coil. This ligation method, which is based on the formation of isoeptide and squaramide bonds, respectively, between the coiled-coil peptides, was successfully used to selectively modify the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Covalent stabilization of the coiled-coil also facilitated truncation of the peptides by one heptad sequence. Furthermore, selective addressing of individual positions of the peptides enabled the generation of mutually selective coiled-coils. The established method, termed Bind&Bite, can be expected to be beneficial for a range of biotechnological and biomedical applications, in which chemical moieties need to be stably attached to proteins in a site-selective fashion.

A pair of heterodimeric coiled-coil peptides was modified to enable covalent stabilization of the dimer without using enzymes or cysteine. Fusion of the peptides to a protein and a chemical moiety, respectively, facilitates site-selective protein modification.

Introduction

The development of methods for the site-selective chemical modification of proteins represents one of the hallmark accomplishments in protein research and chemical biology.1 Applications of such chemically modified proteins are highly diverse and include the in vivo tracking of fluorophore-labelled proteins,2 PEGylation3–6 of therapeutic proteins, as well as the covalent immobilization of proteins on surfaces.7 Ideally, the modification reaction should proceed rapidly, completely, and in bio-compatible media. Furthermore, the starting material should be stable and easily accessible through chemical, biochemical or biosynthetic methods that are feasible in standard laboratories.

Most current strategies for chemical protein modification achieve site-selectivity by utilizing either the unique chemical properties of selectively introduced cysteine and lysine residues, respectively, or the substrate-selectivity of proteases. These methods have been reviewed expertly and extensively.8–11 A complementary method of chemo-selective ligation is based on pairs of peptide adapter domains, which selectively recognize each other, forming heterodimers. Linking these peptide adapters to the protein and the desired chemical moiety, respectively, in conjunction with covalent stabilization of the peptide heterodimer, enables a perfectly site-selective chemical protein modification. Among these peptide adapter domains, heterodimeric α-helical coiled coils are particularly appropriate for chemical ligation reactions, as their sequences are fairly short, i.e. less than 50 amino acids, and they bind to each other with high affinity and selectivity.12,13 The sequences of coiled-coil peptides are typically presented as three to five heptad repeat fragments, i.e. they are 21 to 35 amino acids long.14 Their interaction is driven by the formation of an intermolecular hydrophobic core involving leucine and isoleucine residues, and stabilized by salt bridges between positively (arginine and lysine) and negatively (glutamate and aspartate) charged residues.15,16 Covalent stabilization of coiled-coils has thus far been achieved through sophisticated reactions involving additional cysteine residues flanking the coiled-coil sequences,17 in conjunction with the use of a hetero-bivalent cross-linker18 and native chemical ligation (NCL) using coiled-coils as tag-carriers,19–21 respectively. Here, we set out to explore the feasibility of covalently stabilizing coiled-coils through isopeptide bonds bridging the side chains of glutamate and lysine residues. This setup eliminates the need to introduce cysteine residues, which typically bear the risk of engaging in disulfide shuffling with cysteine residues in the protein, as well as other side reactions.22,23 The principal challenge here was to maintain the selectivity of the interaction, as glutamate and lysine residues are present not only in coiled-coil peptides, but also abundant in proteins, which may give rise to covalent peptide homodimerization, -cyclization or unselective cross-linking with the protein. In order to facilitate chemical synthesis and minimize potential immunogenicity, we selected for this study a pair of relatively short (21 amino acids) coiled-coil peptides, which had been reported to assemble into a parallel heterodimer with high affinity and selectivity.16,24

Results and discussion

Bind&Bite: covalent stabilization of a coiled-coil heterodimer

The coiled-coil selected for this study is formed by interaction of an acidic peptide (PepE, net charge −3) with a complementary basic peptide (PepK, net charge +3) (Fig. 1A). As the covalent stabilization of the peptide heterodimer was intended to be accomplished through the formation of isopeptide bonds between glutamate residues in PepE and lysine residues in PepK, the lysine residues in PepE were replaced with arginine, in order to prevent intramolecular acylation by activated glutamates.18,25 The guanidine group of arginine is expected to be largely protonated at the relevant pH range (7–8) used for the reaction, impeding acylation by an activated carboxylic acid.

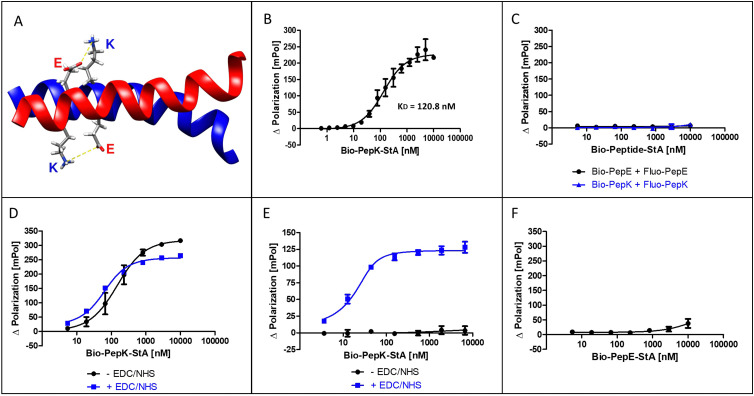

Fig. 1. The Bind&Bite reaction. (A) Structure of the parallel, heterodimeric coiled-coil (pdb code 1u0i). (B) Formation of the non-covalent heterodimer. (C) Lack of non-covalent homodimer formation. (D) Activation of Fluo-PepE does not affect the formation of the heterodimer. (E) Covalent heterodimer is stable in GdnHCl. (F) Lack of covalent homodimer formation. See Experimental section for details.

The interaction of the two coiled-coil peptides was assessed in a binding assay based on fluorescence polarization (Flupol) measurement, for which PepE was fluoresceinylated (Fluo-PepE), and PepK was biotinylated (Bio-PepK, see Table 1 for peptide sequences). Binding of Bio-PepK to streptavidin generated a far larger ligand molecule (Bio-PepK-StA),26 which in initial experiments served as a surrogate for PepK-fusion proteins in later applications of the method. After validating the assay by reproducing the reported affinity of the peptide heterodimer (Fig. 1B), as well as the selectivity, i.e. the lack of homodimerization (Fig. 1C), the heterodimer was covalently stabilized by pseudopeptide bonds. The formation of this covalent crosslink was enabled via activation of the glutamate carboxylic acids by addition of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) to the Fluo-PepE solution, prior to incubation with Bio-PepK-StA. The respective binding curves (with and without EDC/NHS) show a high similarity (Fig. 1D), indicating that pre-activation of Fluo-PepE does not adversely affect its interaction with Bio-PepK-StA. On the other hand, while the non-activated interaction was completely abrogated by addition of the denaturant guanidinium hydrochloride (GdnHCl), the interaction in the presence of EDC/NHS was largely stable at 2 M GdnHCl (Fig. 1E). This fact strongly indicates a covalent stabilization of the heterodimer through isopeptide bonds between the two peptides. Notably, the selectivity of heterodimerization was largely preserved in the presence of EDC/NHS, as homodimerization was detected only at peptide concentrations >5 μM (100-fold molar excess) (Fig. 2F).

Coiled-coil peptide variants.

| Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Bio-PepK | Bioa-Aoab-KIAALKEKIAALKEKIAALKE-NH2 |

| Bio-PepE | Bio-Aoa-EIAALEKEIAALEKEIAALEK-NH2 |

| Fluo-PepE | Fluoc-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREIAALER-NH2 |

| Fluo-PepK | Fluo-Aoa-RIAALRERIAALRERIAALRE-NH2 |

| PepE-Bio | Ac-EIAALEREIAALEREIAALER-Aoa-Aoa-Lys(Bio)-NH2 |

| PepK(K13) | Bio-Aoa-RIAALRERIAALKERIAALRE-NH2 |

| PepK(K6) | Bio-Aoa-RIAALKERIAALRERIAALRE-NH2 |

| PepE(-1C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREIAALE-NH2 |

| PepE(-2C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREIAAL-NH2 |

| PepE(-3C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREIAA-NH2 |

| PepE(-4C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREIA-NH2 |

| PepE(-5C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALEREI-NH2 |

| PepE(-6C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALERE-NH2 |

| PepE(-7C) | Fluo-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALER-NH2 |

| PepE(ARS8) | NBDd-Sare-Aoa-EIAALER-Dapf(EDCBg)-IAALEREIAALER-NH2 |

| PepE(ARS15) | NBD-Sar-Aoa-EIAALEREIAALER-Dap(EDCB)-IAALER-NH2 |

Bio, biotin.

Aoa, 8-amino-3,6-dioxa-octanoic acid.

Fluo, fluorescein.

NBD, 7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl.

Sar, sarcosine.

Dap, 2,3-diaminopropionic acid.

EDCB, 2-ethoxy-3,4-dioxocyclobut-1-en-1-yl.

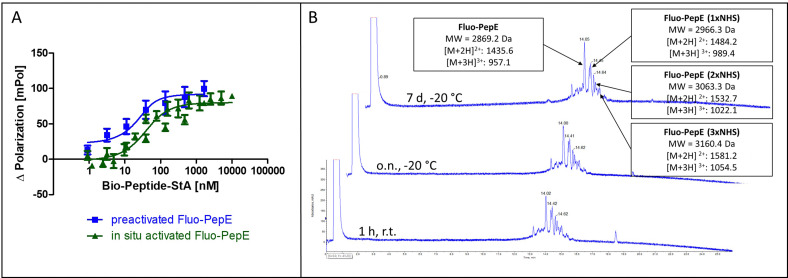

Fig. 2. Reactivity and stability of pre-activated, purified PepE. (A) Covalent interaction of in situ activated Fluo-PepE and pre-activated, purified Fluo-PepE with Bio-PepK-StA (Flupol binding assay, binding curves after treatment with GdnHCl). (B) LC-MS chromatogram of pre-activated, purified Fluo-PepE in acidic solution (0.1% TFA in 50% water/acetonitrile) after 1 hour at room temperature (bottom), as well as after overnight (center) and seven days (top) storage at −20 °C. See Experimental section for details.

In order to achieve complete activation of glutamates in PepE, the required EDC/NHS concentration resulted in a very large molar excess over the peptides, which, in ligation reactions involving PepK fused to a protein, may give rise to activation of glutamate residues in the protein, resulting in undesired intramolecular cross-linking of the protein. Therefore, we assessed the feasibility of purifying the pre-activated Fluo-PepE NHS ester by preparative HPLC. Interestingly, the Fluo-PepE NHS ester turned out to be sufficiently stable, as long as it was kept in acidic solution (pH < 4). The storage stability was demonstrated by the interaction with Bio-PepK-StA, which proceeded similar to the reaction of in-situ activated Fluo-PepE (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that the reaction of Fluo-PepE with EDC/NHS does not yield a completely activated peptide in which all six glutamates are present as NHS esters. In fact, the pre-activated Fluo-PepE is present as a mixture of peptides containing up to three NHS esters, or none at all, which could be separated and detected by LC-MS analysis (Fig. 2B). This heterogeneity, however, does not appear to affect the reactivity of the peptide (Fig. 2A), as even one NHS ester, yielding a single isopeptide bond with PepK, is sufficient to covalently stabilize the coiled-coil. In the mass spectrum of the product of the reaction of pre-activated PepE-Bio with Bio-PepK, we identified the masses of the ligation products containing one and two isopeptide bonds, respectively (Fig. S3, ESI†). The remaining free glutamate carboxylates in the activated PepE may even facilitate the selective interaction with PepK, as they are still available for salt bridges with the complementary lysine residues in PepK. Furthermore, the pre-activated Fluo-PepE NHS ester was shown to be stable at acidic pH at −20 °C for at least one week (Fig. 2B), illustrating the robustness of the developed method.

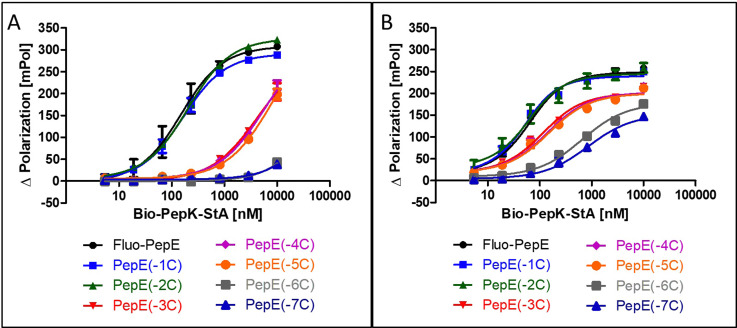

Truncation of coiled-coil peptides

Although the sequences of the coiled-coil peptides used for this study are relatively short, i.e. 21 amino acids, they are still long enough to be potentially immunogenic, in particular when linked to a protein. Therefore, we set out to explore the scope of possible sequence truncation, by evaluating the behaviour of PepE variants upon stepwise, C-terminal truncation. These shortened variants were tested against full-length PepK. Interestingly, PepE tolerates C-terminal truncation by one or two amino acids (PepE(-1C) and PepE(-2C)) in the non-covalent interaction with full-length PepK, as the affinities of these interactions are very similar to full-length PepE (Fig. 3A). Deletion of up to three more amino acids (PepE(-3C), PepE(-4C) and PepE(-5C)), on the other hand, causes a drop in affinity by approximately 40-fold. Further truncation (PepE(-6C) and PepE(-7C)) resulted in complete loss of binding, which, however, could be counteracted by covalently stabilizing the coiled-coils using the Bind&Bite method (Fig. 3B). Using this method, PepE truncated by up to seven residues (PepE(-7C)), i.e. a complete heptad, still binds to full-length PepK at submicromolar concentrations. In conclusion, the Bind&Bite method to covalently stabilize the coiled-coils, facilitated truncation of the PepE sequence by one heptad, which was not possible for the non-covalent coiled-coil.

Fig. 3. Effect of C-terminal truncation of Fluo-PepE on its non-covalent (A) and covalent (B) interaction with Bio-PepK-StA (Flupol binding assay). See Experimental section for details.

Chemical modification of HIV-1 envelope protein

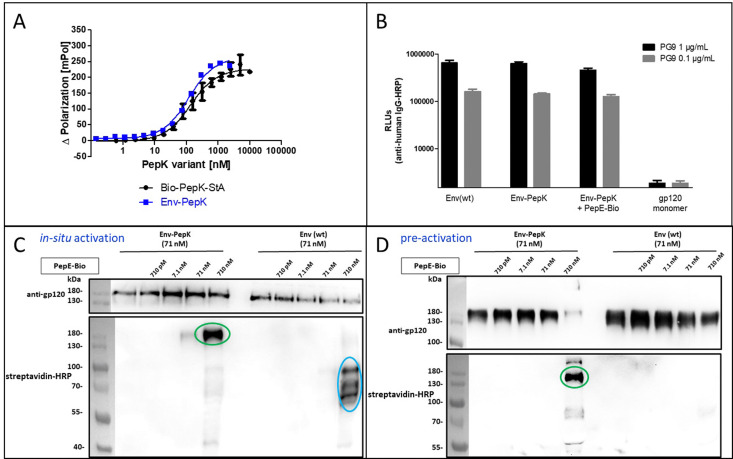

The HIV-1 envelope protein (Env) presents a perfect target for chemical modification, as such modifications can be used to anchor the protein to liposome membranes or other carriers for the generation of vaccines.27–29 The limited scope of strategies for the covalent immobilization/modification of this viral protein poses a significant bottleneck in the generation of such vaccines. To circumvent this limitation in the context of HIV-1, trimeric BG505 NFL2P HIV-1 envelope protein (Env) with a C-terminal His tag30 was used as a model protein to test the Bind&Bite method. The C-terminal His tag of Env was replaced by two additional G4S linkers and the PepK sequence, in order to ensure sufficient flexibility of the coiled-coil peptide, correct presentation, as well as to maintain correct folding of Env into a homotrimer. The fusion protein Env-PepK was expressed in HEK 293-FT cells. Using the Flupol binding assay, it could be shown that the Bind&Bite reaction was well preserved in the interaction of Fluo-PepE with the Env-PepK fusion protein (Fig. 4A), demonstrating that PepK is sterically available for interaction with PepE also when fused to a protein.

Fig. 4. Covalent labeling of Env-PepK with in situ activated and pre-activated PepE. (A) Interaction of Fluo-PepE with Bio-Pep-StA and Env-PepK, respectively (Flupol binding assay). (B) Interaction of the Env trimer specific mAb PG9 with Env(wt), Env-PepK, Env-PepK upon reaction with pre-activated, purified PepE-Bio, as well as monomeric gp120. (C) and (D), reaction of in-situ activated PepE-Bio (C) and pre-activated, purified PepE-Bio (D) with Env-PepK and Env(wt) in DMEM containing 10% FCS. Blots were probed with streptavidin-peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (lower panel), and gp120 antiserum (upper panel). See Experimental section for details.

Addressing the question whether addition of the PepK tag to the Env sequence, and the subsequent reaction with activated PepE, respectively, affects the functional integrity of the protein, the interaction of the modified proteins (Env-PepK and Env-PepK + PepE-Bio) with mAb PG9 was compared to wt protein (Env(wt). PG9 is an antibody that selectively recognizes a conformational epitope formed by gp120 subunits of the functional Env trimer.31 As shown in Fig. 4B, all three Env variants were recognized by PG9, clearly demonstrating preservation of the conformation of Env-PepK prior to, as well as after reaction with pre-activated PepE-Bio. As a negative control, monomeric gp120 was not recognized by PG9.

The selectivity of this interaction of Env-PepK with activated PepE was then probed in a more complex system. Cell culture medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) was spiked with purified Env-PepK and Env(wt), respectively, at 71 nM. Upon addition of in situ activated (Fig. 4C) and pre-activated (Fig. 4D) PepE-Bio, respectively, no reaction of PepE-Bio, regardless of the mode of activation (in situ or pre-activated), with Env(wt) could be detected, demonstrating a selective reaction of activated PepE with lysine residues in the PepK tag of Env-PepK (green marks). Upon incubation of in situ activated PepE-Bio with Env(wt), though, considerable off-target reaction was evident by the presence of additional bands that were detected with streptavidin-HRP (Fig. 4C, blue marks), indicating reaction of activated glutamate residues in PepE-Bio with nucleophiles in other components of the highly complex medium (FCS/DMEM). Such off-target reactions, however, were largely eliminated when using pre-activated, purified PepE-Bio, (Fig. 4D). These results clearly highlight the benefit of using pre-activated, purified PepE for the ligation reaction, as compared to in situ activation, in particular for reactions in solution. For the interaction of PepK fusion proteins with PepE immobilized on particles or surfaces, on the other hand, in situ activation may still be useful. In that setup, which is potentially useful for the purification of proteins from highly complex mixtures, the excess EDC/NHS can be readily removed by washing the particles/surfaces after the activation step, prior to incubation with the PepK fusion protein.

Positionally encoded selectivity

A particular challenge in chemo-selective protein ligation is posed by the need for site-selective modification at more than one site of the protein, as well as the simultaneous, selective labelling of two proteins. Such selectivity can be achieved by using two independent, mutually selective ligation reactions, which can be associated with chemical pitfalls.32,33 An alternative route to achieve selectivity is to use the same ligation method in conjunction with orthogonal adapter molecules, which selectively react only with their designed complementary peptide. This concept has recently been demonstrated by using two orthogonal sets of coiled-coils as templates for the transfer of fluorophores from thioester-linked peptides to the cysteine-modified complementary peptides fused to the proteins of interest.19–21

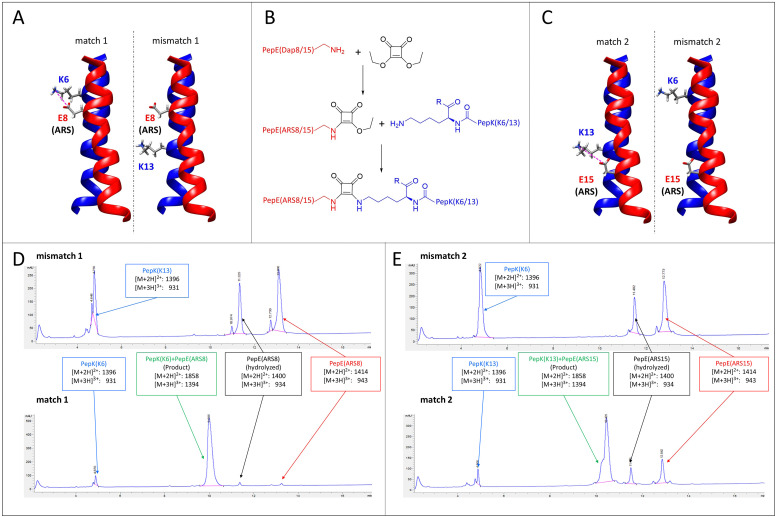

Here, we explore the possibility of designing mutually selective peptide adapters used for the Bind&Bite method, based on the same pair of coiled-coil peptides. This concept utilizes the proximity, provided by spatial arrangement of the coiled-coil, of the glutamate and lysine residues that are linked by pseudopeptide bonds in the Bind&Bite method. Eliminating five of the six possible isopeptide bonds between PepE and PepK was thought to enable the generation of mutually selective peptide pairs featuring single isopeptide bonds at different positions of the coiled-coil. This was achieved by replacing an individual glutamate in PepE with an amine-reactive site (ARS), and preserving only the complementary lysine in PepK. The remaining five lysines in PepK were replaced with arginine, which can still engage in ionic interactions with glutamates in PepE, but is not sufficiently reactive for a covalent reaction with the ARS in PepE (see Table 1 for peptide sequences). The ARS was introduced by first coupling β-Alloc-protected diaminopropionic acid (Dap(Alloc)), which, after selective removal of the Alloc group, was alkylated with squaric acid diethyl ester (SADE). The resulting 2-ethoxy-3,4-dioxocyclobut-1-en-1-yl moiety could then react with the single lysine in PepK, generating a squaramide (Fig. 5B). This reaction, however, was expected to proceed only when the single lysine in PepK was placed in the correct position, i.e. juxtapositioned to the ARS in PepE. In order to probe this selectivity, PepE with the ARS at position 8 and 15, respectively, was reacted with PepK presenting the single lysine at positions 6 and 13, respectively. Essentially no product could be detected for the reaction of PepE(ARS8) with PepK(K13), in which mismatched positions were modified (Fig. 5A, mismatch 1, Fig. 5D, top and Fig. S2, ESI†). In contrast, for the reaction of PepE(ARS8) with PepK(K6), the reactive positions were placed correctly, i.e. in close proximity within the coiled-coil. In this case the ligation provided >90% yield after overnight reaction (Fig. 5A, match 1, Fig. 5D, bottom and Fig. S2, ESI†). On the other hand, PepK(K13) was able to react with PepE(ARS15) (Fig. 5C, match 2, Fig. 5E, bottom and Fig. S2, ESI†), while no product was generated upon combination of PepK(K6) with PepE(ARS15) (Fig. 5C, mismatch 2, Fig. 5E, top and Fig. S2, ESI†). Thus, we have generated two pairs of mutually selective pairs of peptides, i.e. PepK(K6) and PepE(ARS8), as well as PepK(K13) and PepE(ARS15), based on the same original pair of coiled-coil peptides. This excellent selectivity can be expected to enable the simultaneous labelling of two or more proteins with different chemical entities.

Fig. 5. Mutually selective coiled-coils. (A) and (C), illustration of the location of individual lysine residues in PepK and ARS in PepE in the pairs of peptides (structure: pdb code 1u0i). (B) Scheme of the ligation reaction. (D) and (E), HPLC chromatograms (UV absorbance at 220 nm) of the products of the reaction of PepE(ARS8) with PepK(K13) (mismatch 1, D top) and PepK(K6) (match 1, D bottom), as well as of PepE(ARS15) with PepK(K6) (mismatch 2, E top) and PepK(K13) (match 2, E bottom). The shoulder in the product peak of match 2 corresponds to the peptide containing biotin sulfoxide. See Experimental section for details.

It should also be noted that the chemical nature of the ARS is not limited to the squaramide used here, but can be extended to moieties such as isothiocyanates, fluorinated nitroaromates, and aza-Michael acceptors (e.g. sulfonylacrylates). The varying degree of reactivity of these groups enables the fine-tuning of the relationship between speed of reaction and stability (speed of hydrolysis). This flexibility may also enable application of the Bind&Bite method in cells, by using an ARS that is sufficiently stable in biological media, while still being reactive enough to react with the PepK tag attached to proteins.

Experimental

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized as C-terminal amides by Fmoc/tBu-based solid-phase synthesis using an automated multiple peptide synthesizer (ResPep from INTAVIS Bioanalytical Instruments AG, Köln, Germany), as previously described.34 Protected amino acids were obtained from Iris Biotech GmbH, Marktredwitz, Germany). After the final amino acid coupling, the N-terminal amino groups were either acetylated with a mixture of acetic anhydride/pyridine/DMF (1 : 2 : 3) for 30 min, biotinylated (3 eq. biotin, DIC and Oxyma pure (R) in NMP), or fluoresceinylated by coupling of 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (3 eq. 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein, DIC and Oxyma pure (R) in DMF) over night. Peptides were cleaved from the resin by use of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/water/phenol/thioanisole/triisopropylsilane 80 : 5 : 5 : 5, precipitated in cold tert-butyl methyl ether, extracted with water, and lyophilized. Peptides were purified by preparative HPLC (Phenomenex Kinetex C18 column, 100 × 21.2 mm, flow rate 30 mL min−1, gradient of acetonitrile in water (both containing 0.1% TFA, 25–60% over 10 min). Stock solutions of purified peptides were prepared at 2.5 mM in 50% acetonitrile in water. Analytical data (LC-MS) of purified peptides are shown in Fig. S1 (ESI†).

PepE(ARS8) and PepE(ARS15)

At position 8 and 15, respectively, of PepE, Fmoc-Dap(Alloc)-OH was coupled instead of Fmoc-Glu(tBu)-OH. The amino group of the N-terminal sarcosine was arylated by incubating the peptide resin twice for 20 min with NBD-Cl (4-chloro-7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazol, 10 eq., 250 μmol, 49.9 mg) in 0.5 mL DMF, to which DIPEA (10 equiv. 250 μmol, 45.1 μL) was added. NBD was used as a fluorescent identification tag, which is inert to reaction with the ARS. After washing with DMF, the Alloc group was removed from Dap by treating the peptide resin for three hours with a solution of Pd(PPh3)4, (8.6 mg mL−1) and 1,3-dimethylbarbituric acid (13 mg mL−1) in DMF under argon, followed by washing the resin with DCM, DMF, sodium diethyldithiocarbamate trihydrate (4 mg mL−1 in DMF), and DCM. The ARS group was then introduced by overnight coupling of SADE (5 equiv., 125 μmol, 18.5 μL in in 0.5 mL DMF) and NMM (10 equiv., 250 μmol, 27.5 μL). The peptide was cleaved from the resin and purified as described above.

Pre-activated and purified PepE peptides

Fluo-PepE and PepE-Bio, respectively, were dissolved at 500 μM in a mixture containing 30% acetonitrile, 35% 2 M aqueous EDC and 35% aqueous 1.25 M NHS (v/v/v), and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, purified by preparative HPLC, and lyophilized. The dry powder was stored at 4 °C under airtight and moisture-free conditions.

Fluorescence polarization (Flupol) assay

All Flupol assays were carried out using Corning low-volume, black 384 well plates. 5 μL of Fluo-PepE, truncated variants thereof (Fig. 3 and Fluo-PepK (Fig. 1C), respectively (50 nM in water) were mixed with 5 μL of the Bio-PepK-StA, Bio-PepE-StA (Fig. 1C and F), or Env-PepK (Fig. 4A) solutions at serial dilutions, starting at 20 μM, and fluorescence polarization was measured after 30 min using a plate reader (Tecan Infinite F200) equipped with a dual, orthogonal polarized filter set consisting of 485 nm (bandwidth: 20 nm) excitation and 535 nm (bandwidth: 25 nm) emission filters. The readout of the assay was the difference in Flupol values (Δ Polarization) between the samples with and without biotinylated peptide/streptavidin.

Bind&Bite reaction

In situ activation

Activation solution (250 μL) containing EDC (23.8 mg mL−1) and NHS (35.9 mg mL−1) in water was incubated for 30 min with Fluo-PepE (Fluo-PepK in Fig. 1F), final concentration 5 μM. After dilution with 12.25 mL water, 5 μL of the diluted activated Fluo-PepE solution (100 nM) was used for the Flupol assay described above.

Pre-activation

5 μL of purified Fluo-PepE NHS ester solution (100 nM in water) was used for the Flupol assay described above.

For the experiments shown in Fig. 1E and 2A, 5 μL of 6 M GdnHCl was added prior to measuring fluorescence polarization.

Ligation reactions

2.5 μL of 2.5 mM stocks of PepE variants in 50% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA, were mixed with 47.5 μL of 131.6 μM PepK variants in HEPES (0.1 M, pH 7.4). The final concentration of all peptides was 125 μM. After overnight reaction at room temperature, the reaction was quenched by addition of 25 μL of 12% TFA in acetonitrile, followed by centrifugation prior to analysis by LC-MS.

Plasmids

The pcDNA3.1 vector encoding for BG505 NFL2P gp14030 comprising a C-terminal G4S linker and His-Tag was used for stabilized Env trimer expression and purification. A BamHI restriction site was introduced between the G4S linker and the His-Tag. By restriction digestion using the restriction enzymes BamHI and HindIII, the C-terminal His-Tag was replaced by a sequence encoding for two G4S linkers and PepK (…ALDGGGGSGGGGSGGGGSKIAALKEKIAALKEKIAALKEStop).

Protein expression and purification

BG505 NFL2P gp140 trimers (Env(wt)) and BG505 NFL2P gp140 trimers comprising C-terminally fused PepK (Env-PepK) were produced by transfection of FreeStyle™ 293-F cells at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells per mL with the plasmid (1 μg mL−1 DNA) encoding for Env(wt) or Env-PepK, respectively. As transfection reagent, linear polyethylenimine (PEI, Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) in a threefold excess compared to the mass of DNA was used. The transfection mixture was prepared in OPTI-MEM Reduced Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany). Six hours after transfection, the cell culture medium was changed. Three days post-transfection, supernatants were collected, sterile-filtered through a 0.2 μm Minisart filter (Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen) and purified via lectin affinity column chromatography using agarose-bound lectin from Galanthus nivalus (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Elution of the Env trimers was performed using 1M methyl-α-D-mannopyranoside (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), followed by concentration of the purified protein via an Amicon Centrifugal Filter with a 10 kDa cut-off (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Protein concentration was determined by photometric measurement (absorbance at 280 nm) using the ND100-NanoDrop® (peQlab, Erlangen, Germany). Env abundance was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot.

Preparation of protein solutions

Purified Env-PepK and Env(wt) were added to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) yielding a protein solution with a final Env concentration of 10 μg mL−1.

Bind&Bite reaction with Env

In situ activation

PepE-Bio stock solution was prediluted to a concentration of 7.1 μM in water, containing EDC (71 μM) and NHS (177.5 μM). After a 30 minute incubation at room temperature, 10 μL of the activated PepE-Bio was added to 90 μL of Env-K and Env(wt), respectively, resulting in a final Env concentration of 71 nM (equivalent to 10 μg mL−1) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS (equivalent to a protein concentration of 2.5 mg mL−1). The final concentration of PepE-Bio in the protein solution was 710 nM, 71 nM, 7.1 nM and 0.71 nM, respectively. The reaction mixtures were then incubated for 30 minutes at RT and analyzed later with SDS-PAGE and Western Blot.

Pre-activation

Pre-activated and purified PepE-Bio was prediluted to a concentration of 7.1 μM in water, and 10 μl was added to Env-K and Env(wt), respectively, resulting in a final concentration of 71 nM in DMEM/10% FCS. The final concentration of PepE-Bio in the protein solution was 710 nM, 71 nM, 7.1 nM and 0.71 nM, respectively. The reaction mixtures were then incubated for 30 minutes at RT and analysed later with SDS-PAGE and Western Blot.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

For antigen-specific immunoblotting of Env, the reaction mixtures of the Bind&Bite reactions of in situ activated PepE-Bio with Env-PepK and Env(wt), respectively, were mixed with reducing SDS sample buffer, heat-inactivated and loaded on a 10% SDS gel. After gel electrophoresis, protein transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane by semi-dry blotting was performed. Subsequently, the nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween (PBS-T). After washing, the blocked membranes were incubated with polyclonal goat anti-gp120 antibody (Acris Antibodies GmbH, Herford, Germany), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated streptavidin (ABIN376335, antibodies-online.com) for the reaction with PepE-Bio, respectively. Bound polyclonal goat anti-gp120 was detected with HRP-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). Development of the nitrocellulose membranes was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence solution (ECL solution) comprising luminol sodium salt solution, 0.1 M Tris-HCl solution, p-coumaric acid and H2O2, and luminescence was measured using an Advanced Fluorescence Imager (INTAS, Göttingen, Germany).

PG9 binding assay

White, 96-well high-binding plates were coated with 100 ng of mannose-binding Lectin (Galanthus nivalis; Sigma Aldrich L8275) in coating buffer (1 L distilled H2O + 1.58 g Na2CO3 + 2.94 g NaHCO3 pH 9.6) overnight at room temperature (RT). Plates were then washed three times with PBS-T (PBS + 0.1% Tween20) and blocked for 1 hour at RT with 5% skimmed milk in PBS-T followed by addition of 100 μL of Env(wt), Env-PepK, Env-PepK + PepE-Bio and gp120, respectively at 5 μg mL−1 and incubated for 1 hour at RT. After three washes with PBS-T, 100 μL of PG9 (from hivreagentprogram.org, Cat-No. ARP-12149) in 2% skimmed milk was added to all wells at final concentrations of 1 and 0.1 μg mL−1, respectively, and incubated for 1 hour at RT. Plates were washed three times with PBS-T and developed with 100 μL of anti-human IgG-HRP from Dianova (1 : 5000 in 2% skimmed milk) for 1 hour at RT. After washing three times each with PBS-T and PBS, ECL substrate was added and luminescence was read using a Victor X4 plate reader.

Generation of Env-PepK + PepE-Bio

5 μL of pre-activated and purified PepE-Bio (90 μM in water) were added to 45 μL Env-PepK (4.95 μM), resulting in a final Env concentration of 4.5 μM (Env-PepK) and 9 μM (PepE-Bio) in 0.1 M PB pH 7.5. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 minutes at RT, and excess of activated PepE-Bio was removed by centrifugation with Amicon Centrifugal Filters with 30 kDa cut-off (Merck, Darmstadt).

Conclusions

Using a pair of heterodimeric coiled-coil peptides, we have developed a method for the regio-selective chemical modification of proteins that does not require the use of cysteine residues, or enzymes. The method is based on fusing the coiled-coil peptides to the protein, and to the chemical moiety, respectively, in conjunction with covalent stabilization of the heterodimeric coiled-coil through isopeptide bonds. Using the envelope protein of HIV-1, the application of pre-activated, purified peptide precursors was shown to be a key feature of the Bind&Bite method in solution, as it prevents unspecific cross-linking associated with in situ activation of the peptide – protein complex.

Furthermore, using the Bind&Bite method, the PepE sequence could be truncated by up to seven amino acid, which was not possible for the non-covalent coiled-coil.

A specific hallmark of the Bind&Bite method is the possibility of generating mutually selective pairs of peptide adapters based on the same original pair of coiled-coil peptides, by individually addressing matching glutamate-lysine pairs, for the selective formation of individual isopeptide and squaramide bonds, respectively.

Based on these beneficial and unique features, the Bind&Bite method can be considered a novel and highly useful addition to the growing repertoire of methods for the site-selective chemical modification of proteins.

Ongoing research is directed at utilizing the Bind&Bite method for a range of biomedical applications, as well as at exploring the scope of its selectivity for the parallel, concurrent chemical modification of more than one protein with more than one chemical entity.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J. B., K. Ü., J. E.; methodology, J. B., P. T., R. D. V., K. Ü., J. E.; validation, J. B., P. T., R. D. V., K. Ü., J. E.; formal analysis, J. B., P. T., R. D. V., K. Ü., J. E.; investigation, J. B., P. T., R. D. V.; resources, T. S., K. Ü., J. E.; data curation, J. B., P. T., R. D. V., K. Ü., J. E.; writing – original draft preparation, J. B., J. E.; writing – review and editing, J. B., P. T., T. S., K. Ü., J. E.; supervision, T. S., K. Ü., J. E.; project administration, T. S., K. Ü., J. E.; funding acquisition, T. S., K. Ü., J. E.

Conflicts of interest

J. B. and T. S. are employees of Institut Virion-Serion GmbH. P. T., R. D. V., K. Ü. and J. E. declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Part of this research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant 401821119/GRK 2504, projects C1 and C5), as well as by Bayerische Forschungsstiftung (project DeeP-CMV). mAb PG9 was obtained through the NIH HIV Reagent Program.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cb00122a

References

- Boutureira O. Bernardes G. J. L. Advances in chemical protein modification. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:2174–2195. doi: 10.1021/cr500399p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crivat G. Taraska J. W. Imaging proteins inside cells with fluorescent tags. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran V. B. Fee C. Protein PEGylation: An overview of chemistry and process considerations. Eur. Biopharm. Rev. 2010;15:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nischan N. Hackenberger C. P. R. Site-specific PEGylation of proteins: recent developments. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:10727–10733. doi: 10.1021/jo502136n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddi R. N. Rogel A. Resnick E. Gabizon R. Prasad P. K. Gurwicz N. Barr H. Shulman Z. London N. Site-Specific Labeling of Endogenous Proteins Using CoLDR Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:20095–20108. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamshen K. Wang Y. Jamieson S. M. F. Perry J. K. Maynard H. D. Genetic Code Expansion Enables Site-Specific PEGylation of a Human Growth Hormone Receptor Antagonist through Click Chemistry. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020;31:2179–2190. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldal M. Schoffelen S. Recent advances in covalent, site-specific protein immobilization. F1000Research. 2016;5:2303. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9002.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberger C. P. R. Schwarzer D. Chemoselective ligation and modification strategies for peptides and proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:10030–10074. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A. L. Hackenberger C. P. R. Modern Ligation Methods to Access Natural and Modified Proteins. Chimia. 2018;72:802–808. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2018.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish J. A. DeForest C. A. Site-Selective Protein Modification: From Functionalized Proteins to Functional Biomaterials. Matter. 2020;2:50–77. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2019.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M. S. Kong T. W. S. Khoo J. Y. X. Loh T.-P. Recent developments in chemical conjugation strategies targeting native amino acids in proteins and their applications in antibody-drug conjugates. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:13613–13647. doi: 10.1039/D1SC02973H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley E. H. C. Channon K. J. Alpha-helical peptide assemblies giving new function to designed structures. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011;103:231–275. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415906-8.00001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolfson D. N. Coiled-Coil Design: Updated and Upgraded. Subcell. Biochem. 2017;82:35–61. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-49674-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson C. Dånmark S. Zhou F. Öberg P. Enander K. Su H. Aili D. Self-sorting heterodimeric coiled coil peptides with defined and tuneable self-assembly properties. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14063. doi: 10.1038/srep14063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle A. L., in Peptide applications in biomedicine, biotechnology and bioengineering, ed. S. Koutsopoulos, Woodhead Publishing, Oxford, 2017, pp. 51–86 [Google Scholar]

- Lindhout D. A. Litowski J. R. Mercier P. Hodges R. S. Sykes B. D. NMR solution structure of a highly stable de novo heterodimeric coiled-coil. Biopolymers. 2004;75:367–375. doi: 10.1002/bip.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. Liu J. Zheng Q. Li Q. Kallenbach N. R. Lu M. A heterospecific leucine zipper tetramer. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:908–919. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano Y. Furukawa N. Ono S. Takeda Y. Matsuzaki K. Selective amine labeling of cell surface proteins guided by coiled-coil assembly. Biopolymers. 2016;106:484–490. doi: 10.1002/bip.22715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavins G. C. Gröger K. Reimann M. Bartoschek M. D. Bultmann S. Seitz O. Orthogonal coiled coils enable rapid covalent labelling of two distinct membrane proteins with peptide nucleic acid barcodes. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021;2:1291–1295. doi: 10.1039/D1CB00126D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf P. Mohr A. Gavins G. Behr V. Mörl K. Seitz O. Beck-Sickinger A. G. Orthogonal Peptide-Templated Labeling Elucidates Lateral ETA R/ETB R Proximity and Reveals Altered Downstream Signaling. ChemBioChem. 2022;23:e202100340. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202100340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavins G. C. Gröger K. Bartoschek M. D. Wolf P. Beck-Sickinger A. G. Bultmann S. Seitz O. Live cell PNA labelling enables erasable fluorescence imaging of membrane proteins. Nat. Chem. 2021;13:15–23. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-00584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Xue. Longo Liam M. Blaber Michael. Mutation Choice to Eliminate Buried Free Cysteines in Protein Therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;104:566–576. doi: 10.1002/jps.24188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino S. M. Gladyshev V. N. Cysteine Function Governs Its Conservation and Degeneration and Restricts Its Utilization on Protein Surfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;404:902–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litowski J. R. Hodges R. S. Designing Heterodimeric Two-stranded α-Helical Coiled-coils. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:37272–37279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madler S. Bich C. Touboul D. Zenobi R. Chemical cross-linking with NHS esters: a systematic study on amino acid reactivities. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009;44:694–706. doi: 10.1002/jms.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.-W. Jo B.-G. deMello A. J. Choo J. Kim H. Y. Streptavidin-triggered signal amplified fluorescence polarization for analysis of DNA-protein interactions. The Analyst. 2016;141:6499–6502. doi: 10.1039/C6AN01671E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingale J. Stano A. Guenaga J. Sharma S. K. Nemazee D. Zwick M. B. Wyatt R. T. High-Density Array of Well-Ordered HIV-1 Spikes on Synthetic Liposomal Nanoparticles Efficiently Activate B Cells. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1986–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale S. Goebrecht G. Stano A. Wilson R. Ota T. Tran K. Ingale J. Zwick M. B. Wyatt R. T. Covalent Linkage of HIV-1 Trimers to Synthetic Liposomes Elicits Improved B Cell and Antibody Responses. J. Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokatlian T. Kulp D. W. Mutafyan A. A. Jones C. A. Menis S. Georgeson E. Kubitz M. Zhang M. H. Melo M. B. Silva M. Yun D. S. Schief W. R. Irvine D. J. Enhancing Humoral Responses Against HIV Envelope Trimers via Nanoparticle Delivery with Stabilized Synthetic Liposomes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16527. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34853-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. K. de Val N. Bale S. Guenaga J. Tran K. Feng Y. Dubrovskaya V. Ward A. B. Wyatt R. T. Cleavage-Independent HIV-1 Env Trimers Engineered as Soluble Native Spike Mimetics for Vaccine Design. Cell Rep. 2015;11:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. Phogat S. K. Chan-Hui P.-Y. et al., Broad and Potent Neutralizing Antibodies from an African Donor Reveal a New HIV-1 Vaccine Target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W. Luo J. Popik V. V. Workentin M. S. Dual-Bioorthogonal Molecular Tool: “Click-to-Release” and “Double-Click” Reactivity on Small Molecules and Material Surfaces. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019;30:1140–1149. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems Lianne I. Li Nan. Florea Bogdan I. Ruben Mark. van der Marel Gijsbert A. Overkleeft Herman S. Triple Bioorthogonal Ligation Strategy for Simultaneous Labeling of Multiple Enzymatic Activities. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4431–4434. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weißenborn L. Richel E. Hüseman H. Welzer J. Beck S. Schäfer S. Sticht H. Überla K. Eichler J. Smaller, Stronger, More Stable: Peptide Variants of a SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Miniprotein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:6309. doi: 10.3390/ijms23116309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.