Abstract

The in vitro activities of new organometallic chloroquine analogs, based on 4-amino-quinoleine compounds bound to a molecule of ferrocene, were evaluated against chloroquine-susceptible, chloroquine-intermediate, and chloroquine-resistant, culture-adapted Plasmodium falciparum lineages by a proliferation test. One of the ferrocene analogs totally restored the activity of chloroquine against chloroquine-resistant parasites. This compound, associated with tartaric acid for better solubility, was highly effective. The role of the ferrocene in reversing chloroquine resistance is discussed, as is its potential use for human therapy.

The ideal antimalarial drug is a cheap molecule that shows rapid curative activity in the absence of toxicity to the host. Except in regions where chloroquine-resistant isolates are endemic, chloroquine is still the favored treatment both for chemotherapy and for chemoprophylaxis because of its low cost, efficacy, and relative tolerance. Quinine is the drug of choice for severe chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and halofantrine are both used as alternative antimalarial agents after treatment failure with chloroquine. Nevertheless, treatment against severe malaria still remains a problem because of drug resistance in many parts of the world. The search for new compounds for the treatment of malaria has been extensive, but the yield has been very low, as demonstrated by the program of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (less than 10 promising compounds among the 350,000 compounds tested) (35). There is still confusion and doubt about the mechanism of action of chloroquine (36).

Two approaches have been proposed for drug design. The first is the identification of drugs that do not possess any intrinsic antimalarial activity when used alone but that potentiate the effect of antimalarial drugs (e.g., verapamil and desferrioxamine). The second is the development of original antimalarial drugs with enhanced activity and low toxicity (e.g., halofantrine and mefloquine) (1).

We postulated that given the avidity of Plasmodium for free iron (20, 33), an effective way of removing the chloroquine resistance of parasites might be by the addition of iron to a chloroquine molecule. By following this hypothesis, some new organometallic compounds based on chloroquine with a ferrocene nucleus (dicyclopentadienyl iron) localized at different sites were synthesized (2, 4). The present work describes the investigation of the potential activities of these new compounds against P. falciparum parasites by using an in vitro model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of ferrocene-chloroquine analogs.

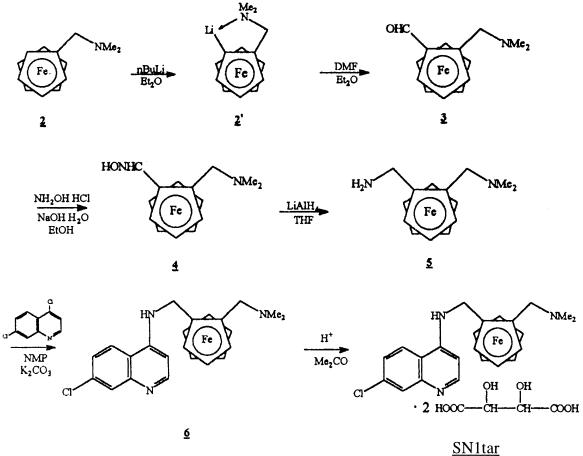

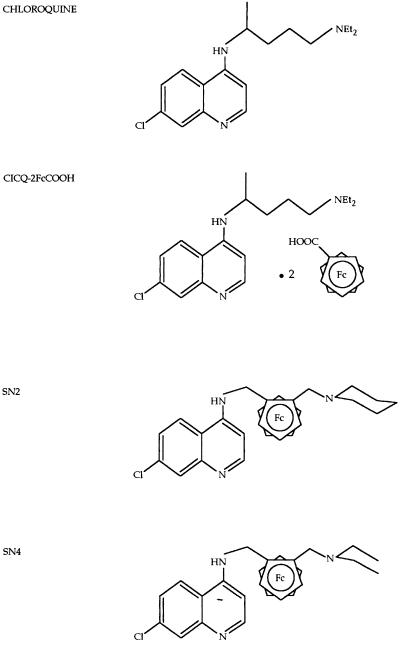

Ferrocene-chloroquine analogs were synthesized by the Laboratoire de Chimie Organométallique, J. Brocard, Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille (2). The synthesis of SN1tar is illustrated in Fig. 1. The dimethylaminomethylferrocene (compound 2; 2.43 g; 10 mM) was metalated with n-butyllithium (5 ml; 12.5 mM) in anhydrous ether under a nitrogen atmosphere. The lithium derivatives were condensed with N,N-dimethylformamide (0.8 ml; 12.5 mM) at room temperature to the resulting 2-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocenylcarboxaldehyde in respectable yields (70%). The aldehyde (compound 3; 1 g; 3.7 mM) was converted to the corresponding oxime by the addition of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.42 g; 6 mM) and sodium hydroxide (0.48 g; 12.2 mM) in ethanol under reflux. Condensation of compound 5 (0.55 g; 2 mM) with 4,7-dichloroquinoline (1.98 g; 10 mM) in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (135°C; 4 h) under a nitrogen atmosphere gave 7-chloro-4{[2-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)]-N-methylferro- cenylamino}quinoline (compound 6) in respectable yields (60%) after purification by chromatography. Conversion of the amine (compound 6; 0.21 g; 0.5 mM) to the ammonium SN1tar was achieved by acidification with two equivalents of l-(+)-tartaric acid (0.15 g; 1 mM) from acetone. The free base (compound 6) was characterized on the basis of elemental analysis, molecular weight determination, UV and infrared spectra, and magnetic measurement (2). The other 7-chloro-4{[2-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)]-N-methylferrocenylamino}quino- line derivatives (compounds SN2 and SN4) are based on the same chemical structure but with another radical at the side chain. SN1 is the same molecule as SN1tar but without the tartaric acid. CICQ-2FcCOOH is a chloroquine molecule with a ferrocene-tartaric acid without covalent binding (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Synthesis of SN1tar (molecular weight of SN1 = 434.5; molecular weight of SN1tar = 733.5) (2). NMe2, N,N,dimethylamino; Me2, dimethyl; Et2O, ethanol; DMF, dimethylformamide; EtOH, ethanol; THF, tetrahydrofuran; NMP, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone; Me2CO, dimethyl cetone.

FIG. 2.

Chemical structures of chloroquine and the 7-chloro-4{[2-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)]-N-methylferrocenylamino}quinoline derivatives (2) (molecular weight of chloroquine diphosphate = 515.9; molecular weight of CICQ-2FcCOOH = 779.5; molecular weight of SN2 = 474.5; molecular weight of SN4 = 462.5). NEt2, diethyl amine; Fc, ferrocene.

Preparation of drugs for in vitro tests.

The control drug, chloroquine diphosphate, was supplied by Sigma (Strasbourg, France). Aqueous insoluble agents (SN1, SN2, and SN4) were dissolved in 20 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then in 80 μl of a 60% ethanol–40% water mixture with 1 mg of product. The aqueous soluble compounds (chloroquine diphosphate, SN1tar, and CICQ-2FcCOOH) were directly dissolved in 100 μl of a 60% ethanol–40% water mixture with 1 mg of product. Stock solutions were diluted to 1 mg/ml in sterile water and were stored at 4°C in the dark. The final dilution in culture contained less than 0.07% ethanol and 0.02% DMSO, which had no measurable effect on the parasites in our system.

Culture-adapted strains of P. falciparum.

Six culture-adapted lineages or clones of P. falciparum were maintained in continuous culture by a method modified from that of Trager and Jensen (38). The chloroquine-susceptible lineages were SGE2/Zaire (5), FG2, and FG4, the semi-chloroquine-resistant lineage was FG3, and the chloroquine-resistant clones were FCM17/Thailand, FCM6/Thailand (24), and FG1 (uncloned isolated lineage). FG1, FG2, FG3, and FG4 were isolated in our laboratory from Gabonese patients (10). Stock cultures were grown in 90-mm-diameter petri dishes with type O-positive European human erythrocytes (CNTS, Paris, France) at 5% hematocrit in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) with 25 mM HEPES buffer supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated type AB-positive serum (CNTS) and 0.2% glucose (RPMI-c) but without antimicrobial agents. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a candle jar and were monitored daily by taking thin blood smears and counting the relative percentages of rings, old trophozoites, and schizonts on Giemsa-stained slides. The cultures were used in proliferation assays when more than 80% ring stages were obtained.

Proliferation tests.

The drug susceptibilities of each lineage were evaluated by using a modification of the proliferation test described by Desjardins et al. (9), based on the level of hypoxanthine incorporation. A suspension of parasitized erythrocytes (PRBCs) in RPMI-c (100 μl/well, 20% hematocrit, 1% parasitemia) was distributed in 96 round-bottom wells predosed with 100 μl of drugs in RPMI-c. The final concentrations of the compounds ranged from 0.001 to 10 μg/ml, with three or six replicates used for each concentration, after which the values were transformed into nanomoles for easy comparison. The results describing the activities of the compounds were compared to the results obtained for untreated parasitized erythrocytes (untreated PRBCs) and PRBCs treated with the solvents used for the drug (ethanol and DMSO). The plates were incubated at 37°C in a candle jar for 48 h. The [G-3H]hypoxanthine (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) was added (2.5 μCi/well) for the final 18 h to assess parasite growth. At the end of the second incubation period, the contents of one well with untreated PRBCs were used to make a Giemsa-stained slide as a control for schizont development, and the plates were stored by freezing and thawing to lyse the erythrocytes. The contents of each well were collected with a cell harvester (Skatron Instruments). The amount of radioactivity incorporated by the schizonts was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman). For each experiment a series of controls were used: slides at the end of the culture, uptake of [G-3H]hypoxanthine by untreated PRBCs, solvent-treated PRBCs, and nonparasitized erythrocytes. With the aim of comparing the activities of the drugs, the IC50 was defined as the concentration of drug that resulted in 50% inhibition. The IC50 was calculated from extrapolation of the regression line by projection of a straight line through the mean disintegrations per minute (radioactivity level) between the maximum and the minimum values. In view of the results obtained under our experimental conditions, we designated the strains chloroquine susceptible if the IC50 was lower than 1,000 nM and chloroquine resistant if the average IC50 was greater than 1,000 nM. The high level of the IC50 is due to the elevation of the hematocrit to 10%.

RESULTS

Antimalarial activities of ferrocene-chloroquine compounds against reference strains.

The activities of the organometallic analogs (SN1, SN2, and SN4) were evaluated by using the chloroquine-susceptible strain SGE2 and the chloroquine-resistant clones FCM6 and FCM17 (Table 1). Against chloroquine-resistant parasites, the new drugs were more effective than chloroquine. Their activities were the same against all parasite strains. However, SN1 was active against the three strains at a lower concentration.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of resistant and nonresistant strains to ferrocene analogs compared to susceptibility to chloroquinea

| Drug | IC50 (nM)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SGE2 | FCM6 | FCM17 | |

| Chloroquine | 287 ± 264 | 4,365 ± 3,301 | 4,555 ± 4,113 |

| SN1 | 196 ± 140 | 230 ± 163 | 373 ± 244 |

| SN2 | 807 ± 310 | 702 ± 478 | 1,026 ± 101 |

| SN4 | 554 ± 292 | 971 ± 292 | 1,003 ± 229 |

Values are the arithmetic mean IC50 ± standard deviation (n = 4 to 12). The compounds were tested in triplicate at five concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 10 μg/ml, after which the results were transformed into nanomolar units.

Antimalarial activities of the tartaric acid forms of the chloroquine analogs against strains SGE2 and FCM17.

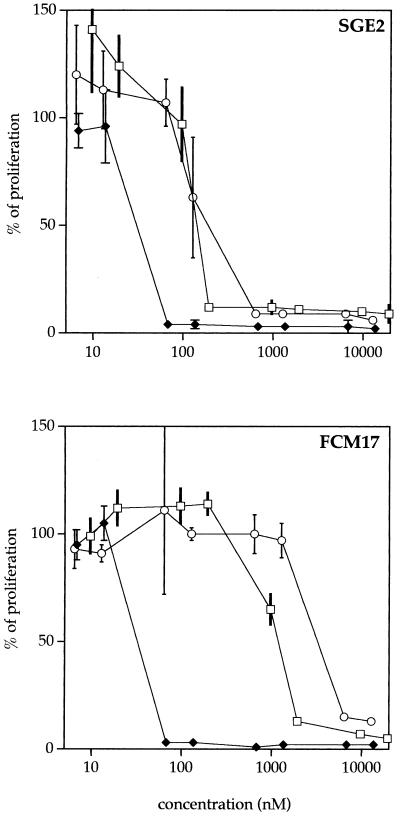

The first analysis allowed us to identify the SN1 compound as the most active ferrocene analog. A tartaric acid form of SN1 (denoted SN1tar) was synthesized. To investigate whether ferrocene must be associated with chloroquine, a ferrocene tartaric acid of chloroquine (CICQ-2FcCOOH) was synthesized and was tested against SGE2 and FCM17. Proliferation curves for the lineages treated with chloroquine, SN1tar, and the tartaric acid control compound are represented in Fig. 3. As demonstrated above with SN1, the SN1tar compounds were more efficient than chloroquine against the chloroquine-resistant strain. On the contrary, the CICQ-2FcCOOH compound was found to show less efficacy than the chloroquine salts.

FIG. 3.

Proliferation curves for SGE2 and FCM17 treated with chloroquine (□), SN1tar (⧫), and CICQ-2FcCOOH (○). The compounds were tested at eight concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 10 μg/ml, with six replicates per concentration, and values were transformed into nanomolar units. The invisible standard deviations are less than 1%.

Antimalarial activity of SN1tar against culture-adapted lineages.

With the intention of comparing chloroquine activity with P. falciparum susceptibility to SN1tar, we classified the lineages according to their chloroquine resistance levels as described above. The standard deviation of the SN1tar IC50 was very low, indicating that this compound is equally active against susceptible and resistant strains (124 ± 74 nM without discrimination of the susceptibility or resistance of the lineage) (Table 2). It also has the same IC50 range as that of chloroquine for chloroquine-susceptible parasites (262 ± 235 nM). For chloroquine-resistant parasites, the IC50s of chloroquine were approximately 30 times greater than those of SN1tar, also without discrimination of the susceptibility or resistance of the lineage (3,774 ± 2,692 and 124 ± 74 nM, respectively).

TABLE 2.

IC50 of chloroquine for each chloroquine-resistant group confronted with SN1tara

| Strain | IC50 (nM)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine | SN1tar | |

| FCM6 | ||

| FCM17 | 3,774 ± 2,692 (17) | |

| FG1 | ||

| FG3 | 971 ± 269 (3) | 124 ± 74 (32) |

| SGE2 | ||

| FG2 | 262 ± 235 (15) | |

| FG4 | ||

Values are the arithmetic mean IC50 ± standard deviation of the mean for the number of isolates (in parentheses). For chloroquine, values are the mean for each group (FCM6, FCM17, and FG1 for chloroquine-resistant strains; SGE2, FG2, and FG4 for chloroquine-susceptible strains; and FG3 for intermediate). For SN1tar, the value is the mean for all strains. Compounds were tested in triplicate at five concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 10 μg/ml, after which the results were transformed into nanomolar units.

DISCUSSION

Among the ferrocene analogs, SN1 and its tartaric acid form, SN1tar (which is soluble in aqueous solution), are effective against all parasites at a low concentration when compared to the efficacy of chloroquine tested against chloroquine-susceptible strains. Because the IC50s of these two compounds are similar, the aqueous solubility does not seem to have an influence on the in vitro antimalarial activity but makes its use easier. This aspect could be advantageous for in vivo use.

With the CICQ-2FcCOOH compound, we have demonstrated that the ferrocene molecule needs to be bound covalently to the chloroquine to inhibit the resistance of the parasites. Thus, the ferrocene by itself does not have an antimalarial activity but enhances the effectiveness of chloroquine when it is enclosed inside the molecule.

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential benefits of the chloroquine side chain modifications. Some compounds with different numbers of carbons (more than eight or less than four) between the two nitrogens on the side chain are more effective than chloroquine against chloroquine-resistant strains (7, 32). In the case of ferrocene analogs, we cannot consider that we increased the length of the side chain by inserting ferrocene because the number of carbons was unchanged, and thus, their effect is not related to an increase in the length of the side chain. On the contrary, both the closely related structures of the chloroquine and ferrocene analogs and the effectiveness of SN1, SN2, and SN4 against all of the strains favor the hypothesis that ferrocene is responsible for the activities of the analogs. This is particularly displayed by SN4, which has a structure closest to that of chloroquine. Nevertheless, SN1 seems to be best disposed toward the inhibition of chloroquine-resistant strains. Although it was not demonstrated, it is likely that the ferrocene iron is involved in the activity of ferrocene analogs.

At the intraerythrocytic stage, malaria parasites ingest the cytosol of their host cell and digest most of the hemoglobin inside the acid food vacuole of the host cell. Proteolysis of hemoglobin releases a toxic free heme (18, 39), the lethality of which is inhibited by the parasite by the formation of hemozoin, a polymerization product. The most convincing explanation of the activity of chloroquine lies in its capacity to inhibit the polymerization of the free heme by the formation of a toxic heme-chloroquine complex (12). In view of their closely related structures, the modes of action of ferrocene analogs and chloroquine could be identical. It could be possible that the affinity of SN1tar for free heme is greater than that of chloroquine, but this explanation is not completely satisfying. This theory of the mechanism of action of chloroquine has not been widely accepted, mainly because the affinities of both quinine and mefloquine for free heme are between 103- and 104-fold lower than that of chloroquine (6). An alternative theory has suggested that the release of iron from hemoglobin is essential for the supply of iron for the parasite’s anabolism (15); however, investigators have surmised that another possible function of chloroquine is its action of depriving the parasite of iron, since chloroquine inhibits the release of iron from hemoglobin (16). Desferrioxamine, an iron chelator, also has an antiplasmodial activity, but it seems that this is a direct effect against the parasite rather than a change in the body’s iron status (19, 21, 30). Because parasites must obtain iron from endogenous sources, it has been suggested that parasites obtain iron through transferrin receptors localized in the host cell membrane (20, 33), although the parasites grow normally in transferrin-depleted serum (34). Pollack (31) could not display a transferrin receptor in the host cell membrane, but he observed a nonspecific liaison between transferrin and the erythrocytic membrane. On the other hand, clinical reports suggest that iron supplementation is definitely contraindicated because it would increase a person’s susceptibility to infection with the malaria parasite (29). In contrast, another study has shown that iron supplementation is not associated with an increased prevalence of malaria (40). The role of iron in malaria remains unclear.

In rats, three ferrocene compounds were used at high concentrations to produce an experimental iron overload. This was used as an animal model of severe hepatocellular iron in humans (28). In contrast to ferrocene alone, iron from 3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl ferrocene (TMH-ferrocene) was completely released from the hydrocarbon moiety within the liver. In the case of ferrocene-chloroquine, the iron is assumed to be accessible to the cells, but we cannot insist that this is so because iron is very strongly attached to the ferrocene, as is ferrocene to the chloroquine analog.

Given the present incomplete knowledge of the iron-malaria interactions and the pharmacology of ferrocene, the manner in which ferrocene from SN1tar increases the activity of chloroquine is still a matter of conjecture. Our results, however, suggest that ferrocene acts as an inhibitor of chloroquine resistance, yet without increasing the activity of chloroquine. Against all lineages, the IC50 of SN1tar is the same as that of chloroquine against the chloroquine-susceptible strains. Hence, we assume that SN1tar inhibits the resistance of parasites. We observed a similar effectiveness of the synergistic effect of SN1tar and calcium channel inhibitors like verapamil (26). However, the ferrocene has no effect when it is used with chloroquine without covalent binding, as we demonstrated with the compound CICQ-2FcCOOH. Ferrocene probably has a mode of action different from that verapamil on the mechanism of resistance of the parasite. The basis of chloroquine resistance is not fully understood. It is known that chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strains accumulate less chloroquine than sensitive parasites (13, 14, 41). According to Krogstad et al. (22, 23), this difference is a consequence of an efflux of chloroquine from resistant parasites, which is an ATP-dependent and pH-independent phenomenon. This efflux could be an effect of the localization of permeases in the membrane of the digestive vacuole of the parasite (42). SN1tar could inhibit its efflux due to the permease being maladjusted to the modified chloroquine. On the other hand, following the hypothesis of the food vacuole pH (17), ferrocene could prevent its release by remaining in the protonated form at a less acidic pH in the food vacuoles of resistant parasites. Indeed, protonated chloroquine becomes deprotonated at low acid pH, and this is thought to be the only form which can freely be released from the food vacuole (8). Nevertheless, even if the efflux hypothesis seems to be the more consistent one, the work of some other investigators is not in agreement with that hypothesis (3, 11). This lack of knowledge does not allow us to explain clearly the mechanism of action of SN1tar. In order to understand how SN1tar works, it will be essential to compare the efflux of SN1tar and chloroquine from chloroquine-resistant strains. The lack of efflux of SN1tar from resistant parasites could explain the mechanism of inhibition of chloroquine resistance by SN1tar and support the hypothesis of efflux as a mechanism of resistance.

We hypothesize that we have circumvented the chloroquine resistance of parasites by inhibition of the efflux as a result of the addition of iron to chloroquine. The tartaric acid form, being soluble in an aqueous solution, can favor the bioavailability of the drug. From an in vivo use perspective, it is possible that continuous or repeated drug pressure would decrease the susceptibilities of P. falciparum to SN1tar because parasites may develop a mechanism of resistance such as that which already exists against chloroquine. Some reports suggest caution with regard to iron refeeding, which could breed malaria in patients in areas where malaria is endemic (27, 29). Considering the weak contribution of iron in ferrocene-chloroquine, it is unlikely that this drug may favor a significant increase in blood iron levels and thus the likelihood of developing patent malaria. Furthermore, only 25% of the iron from ferrocene is usable in humans (37). On the other hand, if ferrocene-chloroquine is metabolized in the liver, as seen with TMH-ferrocene, the drug will probably lose its properties. Toxicological tests are evidently necessary to secure the low incidence and severity of adverse effects for therapy and prophylactic use. Leung et al. (25) have studied the acute toxicity of three substituted ferrocenes [acetylferrocene, ethylferrocene, and 2,2-bis(ethylferrocenyl)propane] in monkeys. Acetylferrocene was found to be the most toxic, with an oral lethal dose of between 10 and 100 mg/kg of body weight, which is greater than the dose of SN1tar that would be used for normal treatment on the basis of chloroquine treatment (500 mg/day for an adult). The chronic toxicity of ferrocene in dogs was investigated by Yeary (43). No significant evidence of toxicity was detectable following oral administration of 30 mg/kg daily for a 6-month period.

Many antimalarial drugs have been synthesized and tested, but drug resistance is often associated with chloroquine resistance and their toxicities are sometimes greater than that of chloroquine (1). The concept behind ferrocene analogs is new, with the aim of improving the pharmacokinetics rather than activity. SN1tar could be a drug with real effectiveness for both therapy and prophylaxis against malaria at a low cost and would be of interest to countries where chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum is widespread.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Williams for reading the manuscript and P. Deloron for the gifts of FCM6 and FCM17.

The Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville is supported by the government of Gabon, Elf Gabon, and Ministère de la Coopération Française.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

In all studies in which these molecules are to be used, the following nomenclature will apply: SN1, JB QN 4; SN2, JB CQ 6; SN4, JB CQ 5; CICQ2Fc-COOH, JB CQ 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basco L K, Ruggeri C, Le Bras J. Molécules antipaludiques. Paris, France: Masson; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biot C, Glorian G, Maciejewski L A, Domarle O, Millet P, Abessolo H, Dive D, Georges A J G, Abessolo H, Dive D, Lebibi J, Brocard J S. Synthesis and antimalarial activity in vitro and in vivo of a new ferrocene-chloroquine analogue. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3715–3718. doi: 10.1021/jm970401y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray P G, Howells R E, Ritchie G Y, Ward S A. Rapid chloroquine efflux phenotype in both chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. A correlation of chloroquine sensitivity with energy-dependent drug accumulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90532-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocard, J., J. Lebibi, and L. A. Maciejewski. 1995. Brevet d’invention no. 9505532 du 10/05/95; Brevet international no. PCT/FR96/00721 du 10/05/96.

- 5.Chizzolini C, Dupont A, Akue J P, Kauffman M H, Verdini A S, Pessi A, Del Giudice G. Natural antibodies against three distinct and defined antigens of Plasmodium falciparum in residents of a mesoendemic area in Gabon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:150–156. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou A C, Chevli R, Fitch C D. Ferriprotoporphyrin IX fulfills the criteria for identification as the chloroquine receptor of malaria parasites. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1543–1549. doi: 10.1021/bi00549a600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De D, Krogstad F M, Cogswell F B, Krogstad D J. Aminoquinolines that circumvent resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:579–583. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Duve C, De Barsy T, Poole B, Trouet A, Tulkens P, Van Hoof F. Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:2495–2531. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desjardins R E, Canfield C J, Haynes J D, Chulay J D. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:710–718. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domarle O, Ntoumi F, Belleoud D, Sall A, Georges A J, Millet P. Plasmodium falciparum: adaptation in vitro of isolates from symptomatic individuals in Gabon: polymerase chain reaction typing and evaluation of chloroquine susceptibility. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:208–209. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrari, V., and D. J. Cutler. 1991. Simulation of kinetic data on the influx and efflux of chloroquine by erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Evidence for drug-importer in chloroquine-sensitive strains. Biochem. Pharmacol. 42(Suppl.):S167–S179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fitch C D. Antimalarial schizonticides: ferriprotoporphyrin IX interaction hypothesis. Parasitol Today. 1986;2:330–331. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(86)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitch C D. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum: difference in the handing of 14C-amodiaquin and 14C-chloroquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973;3:545–548. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.5.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitch C D. Plasmodium falciparum in owl monkeys: drug resistance and chloroquine binding capacity. Science. 1970;169:289–290. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3942.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabay T, Ginsburg H. Hemoglobin denaturation and iron release in acidified red blood cell lysates—a possible source of iron for intraerythrocytic malaria parasites. Exp Parasitol. 1993;77:261–272. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabay T, Krugliak M, Shalmiev G, Ginsburg H. Inhibition by anti-malarial drugs of haemoglobin denaturation and iron release in acidified red blood cell lysates—a possible mechanism of their anti-malarial effect? Parasitology. 1994;108:371–381. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginsburg H. Antimalarial drugs: is the lysosomotropic hypothesis still valid? Parasitol Today. 1990;6:334–337. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginsburg H, Demel R A. The effect of ferriprotoporphyrin IX and chloroquine on phospholipid monolayers and the possible implication to antimalarial activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;732:316–319. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(83)90219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordeuk V R, Thuma P E, Brittenham G M, Biemba G, Zulu S, Simwanza G, Kalense P, M’Hango A, Parry D, Poltera A A, Aikawa M. Iron chelator as a chemotherapeutic strategy for falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:193–197. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haldar K, Henderson C L, Cross G A M. Identification of the parasite transferrin receptor of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes and its acylation via 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8565–8569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershko C, Peto T E A. Deferoxamine inhibition of malaria is independent of the host iron status. J Exp Med. 1988;168:375–387. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogstad D J, Gluzman I Y, Herwaldt B L, Schlesinger P H, Wellems T E. Energy dependence of chloroquine and chloroquine efflux in Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogstad D J, Gluzman I Y, Kyle D E, Oduola A M, Martin S K, Milhous W K, Schlesinger P H. Efflux of chloroquine from Plasmodium falciparum: mechanism of chloroquine resistance. Science. 1987;238:1283–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.3317830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Bras J, Deloron P. In vitro study of drug sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum: evaluation of a new semi-micro test. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:447–451. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung H W, Hallesy D W, Shott L D, Murray F J, Paustenbach D J. Toxicological evaluation of substituted dicyclopentadienyliron (ferrocene) compounds. Toxicol Lett. 1987;38:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(87)90117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin S K, Oduola A M J, Milhous W K. Reversal of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum by verapamil. Science. 1987;235:899–901. doi: 10.1126/science.3544220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray M J, Murray A B, Murray N J, Murray M B. Refeeding-malaria and hyperferraemia. Lancet. 1975;ii:653–654. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen P, Heinrich H C. Metabolism of iron from (3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl) ferrocene in rats. A dietary model for severe iron overload. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oppenheimer S J. Iron and malaria. Parasitol Today. 1989;5:77–79. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(89)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peto T E A, Thompson J L. A reappraisal of the effects of iron and desferrioxamine on the growth of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro: the unimportance of serum iron. Br J Haemotol. 1986;63:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb05550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollack S. Plasmodium falciparum iron metabolism. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;313:151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridley R G, Hofheinz W, Matile H, Jaquet C, Dorn A, Masciadri R, Jolidon S, Richter W F, Guenzi A, Girometta M A, Urwyler H, Huber W, Thaithong S, Peters W. 4-Aminoquinoline analogs of chloroquine with shortened side chains retain activity against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1846–1854. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez M H, Jungery M. A protein on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes functions as a transferrin receptor. Nature. 1986;324:388–391. doi: 10.1038/324388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Lopez R, Haldar K. A transferrin-independent iron uptake activity in Plasmodium falciparum-infected and uninfected erythrocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;55:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90122-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuster B G, Milhous W K. Reduced resources applied to antimalarial drug development. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:167–168. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slater A F. Chloroquine: mechanism of drug action and resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;57:203–235. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90056-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens A R., Jr . Iron in clinical medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trager W, Jensen J B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vander Jagt D L, Hunsaker L A, Campos N M. Characterization of a hemologin-degrading, low molecular weight protease from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;18:389–400. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hensbroek M B, Morris Jones S, Meisner S, Jaffar S, Bayo L, Dackour R, Phillips C, Greenwood B M. Iron, but not folic acid, combined with effective antimalarial therapy promotes haematological recovery in African children after acute falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:672–676. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verdier F, Le Bras J, Clavier F, Hatin I, Blayo M C. Chloroquine uptake by Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes during in vitro culture and its relationship to chloroquine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:561–564. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warhurst D C. Mechanism of chloroquine resistance malaria. Parasitol Today. 1988;4:211–213. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeary R A. Chronic toxicity of dicyclopentadienyl iron (ferrocene) in dogs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1969;15:666–676. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(69)90067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]