Abstract

Background and purpose

Flow diversion has established as standard treatment for intracranial aneurysms, the Surpass Streamline is the only FDA-approved braided cobalt/chromium alloy implant with 72-96 wires. We aimed to determine the safety and efficacy of the Surpass in a post-marketing large United States cohort.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective multicenter study of consecutive patients treated with the Surpass for intracranial aneurysms between 2018 and 2021. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, and aneurysm characteristics were collected. Efficacy endpoint included aneurysm occlusion on radiographic follow-up. Safety endpoints were major ipsilateral ischemic stroke or treatment-related death.

Results

A total of 277 patients with 314 aneurysms were included. Median age was 60 years, 202 (73%) patients were females. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity in 156 (56%) patients. The most common location of the aneurysms was the anterior circulation in 89% (279/314). Mean aneurysm dome width was 5.77 ± 4.75 mm, neck width was 4.22 ± 3.83 mm, and dome/neck ratio was 1.63 ± 1.26. Small-sized aneurysms were 185 (59%). Single device was used in 94% of the patients, mean number of devices per patient was 1.06. At final follow-up, complete obliteration rate was 81% (194/239). Major stroke and death were encountered in 7 (3%) and 6 (2%) cases, respectively.

Conclusion

This is the largest cohort study using a 72–96 wire flow diverter. The Surpass Streamline demonstrated a favorable safety and efficacy profile, making it a valuable option for treating not only large but also wide-necked small and medium-sized intracranial aneurysms.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage, interventional, flow diverter

Introduction

Flow diverters (FDs) have consolidated as a strong alternative in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. While initially indicated for the treatment of large wide-necked aneurysms found in the more proximal segments of the internal carotid artery (ICA), 1 FDs have gained greater recognition and have expanded their use over the years. 2 With positive occlusion rates and favorable clinical outcomes, FDs have demonstrated to be effective and safe for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms.3–5

More than ten types of FDs are used in clinical practice, each with a different design and configuration. 6 A distinction among available FDs resides in their composition between either cobalt/chromium or nitinol, which is the primary determinant of its physical properties and behavior at the time of delivery. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has currently approved the Pipeline Embolization Device (PED, Covidien, Irvine, CA), the Surpass Streamline (SS, Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA), and the Surpass Evolve (SE, Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA) all of which are made up of cobalt/chromium, and the Flow Re-direction Endoluminal Device (FRED, MicroVention, Aliso Viejo, CA) which is built of nitinol.

The SS is the flow diverter (FD) with the largest number of wires (between 72–96 wires) in the market. It is a braided cobalt/chromium alloy stent with a braid angle design that preserves structural integrity.7,8 The number of wires increases with device diameter to achieve a consistent mesh density across the aneurysm neck. Mesh density ranges from 21–32 pores/mm2. It comes preloaded in a 0.040-inch delivery microcatheter 8 and has an over-the-wire delivery system, in which a 0.014-inch microwire passes through for support and navigation. 7

The Surpass Intracranial Aneurysm Embolization System Pivotal Trial to Treat Large or Giant Wide Neck Aneurysms (SCENT) study was a large, prospective, multicenter trial to measure the safety and efficacy of the SS for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. At the final 12-month follow-up, 62.8% of the patients achieved complete aneurysm occlusion in the absence of significant (>50%) parent artery stenosis and no retreatment. 7 The results of this study evaluated the performance of this newly designed device (higher number of wires) to safely treat large and giant wide-necked aneurysms (mean aneurysm dome diameter of 12 mm) located in the ICA up to its terminus. 7 Furthermore, the reported findings were pivotal for its FDA approval in 2018.

Despite the recent release of the SE, the unique design of the SS makes it a valuable option in the neuro-interventionalist armamentarium, especially for patients with aneurysms that require long devices or dysplastic vessels that require larger diameter FDs. After three years in the market, the objective of this study was to determine the post-marketing safety and efficacy of the SS in a widely variable cohort of patients and aneurysms amongst multiple high-volume centers in the United States. We specifically aimed to evaluate the rates of complete aneurysm occlusion and the neurologic morbidity and mortality of consecutive patients treated with the SS.

Methods

Study design

This is a retrospective, multicenter observational cohort study evaluating consecutive patients treated with the SS for intracranial aneurysms between January 2018 and June 2021. All the centers that participated were high-volume centers with experienced neuro-interventionalists (≥25 cases treated with SS) in the United States. Interventionalists from participating centers exclusively used the SS during the study period. The criteria for eligibility and inclusion of subjects were: (1) adults (≥ 18 years) and (2) intracranial aneurysms treated with the SS.

All sites instituted and maintained locally approved Institutional Review Board compliant databases that allowed data collection. The REDCap (Vanderbilt University, TN) software which is a secure Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant web-based platform, was selected for the data collection. 9

Data collection and clinical variables

A standardized REDCap dataset form and data dictionary was created and employed after consensus from the participating centers. Clinical and radiographic variables from each participating center were shared with the coordinating center through a secured Citrix ShareFile Portal (Citrix Systems, Fort Lauderdale, FL). The coordinating center verified data integrity and quality. The data were merged into the main database if minimum standards were met. Collected variables included baseline demographic information, medical history, comorbidities, prescription drug use, and pre-procedural level of functionality using the modified Rankin scale (mRS). Radiographic information included aneurysm location, dimensions, rupture history, and prior treatment. Aneurysm size classification was determined according to previously described literature. 10 Technical information included device size and length, use of ancillary devices during delivery, and device-related complications. Procedural information included procedure duration, platelet function test prior to the procedure, vascular access site, adjunctive drugs used, and post-procedural antiplatelet regimen.

Technical procedure

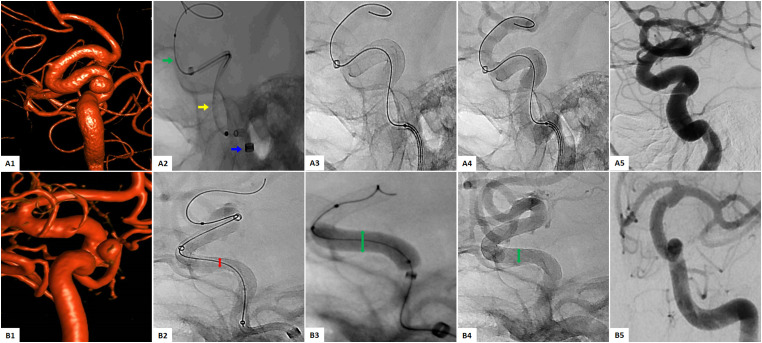

All the procedures were performed according to the treating center’s protocol, with subtle differences between centers. Elective patients were pretreated (5–7 days prior to procedure) with a dual-antiplatelet therapy regimen (the treating physician selected the specific pharmacological agents). In most cases, the same dual-antiplatelet therapy regimen was maintained for at least six months after the procedure. Platelet function assay was performed according to each center’s protocol. During the procedure, patients underwent general anesthesia. Access site was selected between radial and femoral (interventionalist preference). The proceduralist determined intraoperative heparin and/or IIb/IIIa inhibitor use. To reach the targeted intracranial vessel, roadmap fluoroscopic guidance was employed. A tri-axial system composed of an Infinity Long Plus AXS LS (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA) sheath over a Catalyst 5 AXS or AXS Vecta 71 (both Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA) intermediate catheter, both catheters over an offset microcatheter and a Synchro 2 Guidewire (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA) or a standard microcatheter, were introduced. The system was navigated across the aneurysm neck, and the microcatheter was replaced by the SS. At this point, the device was unsheathed across the landing zone. After unsheathing approximately 50%, a control digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed to verify anatomical placement and wall apposition. The device was resheathed and redeployed in the desired position if repositioning was needed. The implant was completely deployed if the anatomical target was achieved (complete coverage of the aneurysm neck). Post-deployment DSA was performed to confirm complete wall apposition of the FD and ideally, aneurysm flow stagnation.7,11 In cases where wall apposition was suboptimal, microwire manipulation and/or balloon-assisted angioplasty were used (at the discretion of the proceduralist). In addition, balloon-assisted angioplasty was performed routinely by the selection of the proceduralist in the cases where the FD was deployed in vessels with dysplastic configuration or the anatomic location of the aneurysm was concerning for potential FD malposition. Finally, if the FD did not achieve complete wall apposition at its proximal or distal end after balloon-assisted angioplasty, an adjunctive stent was used to completely oppose the device to the vessel wall. In Figure 1, two illustrative cases are presented showing a routine deployment case (A1–5) and a case where balloon-assisted angioplasty was performed (B1–5).

Figure 1.

(A1-5) Illustrative case 1: Flow diversion of a right ICA cavernous segment aneurysm with the SS. (A1) Preoperative 3-D reconstruction. (A2) SS delivery system: Infinity intermediate catheter (blue arrow), Cat 5 distal access catheter (yellow arrow), Streamline catheter containing the SS over synchro microwire 0.014 inch (green arrow). (A3) Full deployment of the SS. (A4) Optimal vessel wall apposition. (A5) DSA showing complete occlusion at 6 months. (B1-5) Illustrative case 2: Flow diversion with balloon-assisted angioplasty of a left ICA paraopthalmic saccular aneurysm. (B1) Preoperative 3-D reconstruction. (B2) Sub-optimal wall apposition in the midsegment (red arrow). (B3) Balloon-assisted angioplasty (green arrow). (B4) Post angioplasty image with showing improved FD aperture. (B5) DSA showing complete occlusion at 6 months.

Clinical and radiological outcomes

According to the treating center's protocol, clinical and radiological follow-up data were collected at different time points and encounters. A typical follow-up schedule was done at 1–3-months, 6–12-months, and >12-months.

The primary efficacy composite endpoint was defined by the percentage of patients that achieved total aneurysm occlusion in the absence of significant (>50%) parent vessel stenosis and target aneurysm retreatment at final follow-up (>12-months). Initial evaluation of the primary efficacy endpoint was completed between 6- to 12-months.To evaluate aneurysm obliteration, each patient had a 3-point Raymond-Roy scale classification (Raymond-Roy) of their follow-up DSA image, where Raymond-Roy Class I was complete obliteration. 12

The primary safety endpoint was determined by the percentage of patients who experienced treatment-related death or major ipsilateral ischemic stroke from the date of procedure to the first follow-up. Major ipsilateral ischemic stroke was defined as an increase of ≥4 points in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). The secondary safety endpoint was determined by the percentage of minor stroke or target aneurysm rupture during the same time frame as the primary endpoint. Minor ischemic stroke was defined as an increase of <4 points in the NIHSS. Data for the safety outcomes was collected during the procedure, in the periprocedural period (up to 30 days post-procedure), and up to the final follow-up (≥30 days after the intervention).

Clinical and procedural complications were collected during the hospital stay and at clinical follow-ups. Procedure-related complications included vessel perforation, dissection, vasospasm, and acute in-stent thrombosis or stenosis. Clinical complications included cerebral hypoperfusion, contrast neurotoxicity, and spontaneous non-aneurysmal intracranial hemorrhage. Finally, mortality within the study period related or unrelated to the flow diversion procedure was assessed and reported.

Statistical analysis

All analyzes were performed using R software (version 4.1.0) for Windows and reported p-values were 2-sided, with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant. Based on data distribution, continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation or median with the interquartile range as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The normality of distributions was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test

Clinical and radiological predictors of complete occlusion, major stroke, and/or death were screened using univariate Chi-squared tests and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. A multivariable logistic model was selected using a stepwise backward variable selection algorithm. Because of clinical relevance, balloon-assisted angioplasty, neck width, and hypertension were kept at each step of the selection procedure. The other variables selected for the stepwise regression included the following: (1) all significant variables in the univariate analysis (p ≤ 0.05), (2) baseline characteristics such as demographics, risk factors, comorbid conditions, clinical presentation, and aneurysm attributes (dome height, neck width, history of rupture), and (3) procedural characteristics (number of devices used, implantation success and use of adjunctive stents). Finally, an adjustment for high-volume centers (≥25 treated cases/center) was performed. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates were obtained by applying a logistic regression fit to the chosen model.

Results

Baseline demographics and aneurysm characteristics

A total of 277 patients with 314 aneurysms were included in the study (Tables 1 and 2). The median age was 60 years (interquartile range: 50–68), and 202 patients (72%) were female. Hypertension in 156 (57%) patients and hyperlipidemia in 77 (28%) were the most common comorbidities. A history of smoking was observed in 118 (43%) patients. In 122 (44%) individuals, the aneurysm was found incidentally. Headache was the most common symptomatic presentation in 63 (23%) patients, followed by cranial nerve deficit in 23 (8%). A baseline mRS score of 0–2 was seen in 267 (96%) patients. Two hundred and forty-six (89%) patients presented with one aneurysm. Left and right-side aneurysms were 150 (48%) and 148 (47%), respectively. There were 279 (89%) anterior circulation aneurysms; of these, the most common location was ICA paraophthalmic in 131 (42%) cases, and posterior circulation aneurysms were diagnosed in 35 (11%) patients. Saccular type aneurysms were the most common morphology in 267 (85%) cases, followed by fusiform in 29 (9%). Mean aneurysm dimensions were the following: dome height 5.87 ± 5.52 mm, dome width 5.77 ± 4.75 mm, neck width 4.22 ± 3.83 mm, and dome/neck ratio 1.63 ± 1.26 mm. One-hundred and eighty-five aneurysms (59%) were small-sized (<5 mm dome width), followed by 88 (28%) medium-sized (>5–10 mm dome width). Previous treatment was seen in 31 (10%) aneurysms, of which coiling was the most common in 17 (5%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of aneurysms | 314 |

| No. of patients | 277 |

| No. of procedures | 283 |

| Patient demographics | |

| Median age, y (interquartile range) | 60 (50-68) |

| Female, n (%) | 202 (72.9) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 157 (56.7) |

| Hispanic | 55 (19.9) |

| Black | 48 (17.3) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 156 (56.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 77 (27.8) |

| Diabetes | 52 (18.8) |

| Anxiety | 39 (14.0) |

| Stroke, TIA | 40 (14.4) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| No | 158 (57.0) |

| Yes | 118 (42.6) |

| Clinical Presentation, n (%) | |

| Incidental/asymptomatic | 122 (44.0) |

| Headache | 63 (22.7) |

| Cranial nerve deficit/mass | 23 (8.3) |

| Recurrent after coiling/stent coiling | 15 (5.4) |

| SAH | 10 (3.6) |

| Other a | 29 (10.5) |

| Baseline mRS, n (%) | |

| 0–2 | 267 (96.4) |

| 3–5 | 10 (3.9) |

| Aneurysms per patient, n (%) | |

| 1 aneurysm | 246 (88.8) |

| 2 aneurysms | 27 (9.8) |

| 3 or 4 aneurysms | 4 (1.4) |

Vertigo, dizziness, syncope, pain.

Table 2.

Aneurysm, technical and procedural characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Aneurysm characteristics | |

| Mean aneurysm dimensions, mm (SD) | |

| Dome height | 5.87 (5.52) |

| Dome width | 5.77 (4.75) |

| Neck width | 4.22 (3.83) |

| Dome/neck ratio | 1.63 (1.26) |

| Side, n (%) | |

| Left | 150 (47.8) |

| Right | 148 (47.1) |

| Other a | 16 (5.1) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| ICA – paraopthalmic | 131 (41.7) |

| ICA – petrocavernous | 72 (22.9) |

| ICA – supraclinoid (PCoA, AChA) | 67 (21.3) |

| Basilar trunk | 14 (4.5) |

| Vertebral | 13 (4.1) |

| ICA – terminus, MCA, ACA, PICA b | 12 (3.8) |

| SCA | 4 (1.3) |

| PCA | 1 (0.3) |

| Morphology, n (%) | |

| Saccular | 267 (85.0) |

| Fusiform | 29 (9.2) |

| Pseudoaneurysm, blister, dissecting | 22 (7.0) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | 31 (9.9) |

| Coil | 17 (5.4) |

| Stent or stent + coil | 12 (3.8) |

| Microsurgery/clipping or endovascular + extravascular | 2 (0.6) |

| Technical characteristics | |

| SS used per aneurysm, mean (range) | 1.06 (1-3) |

| Mean SS length, mm (SD) | 25.6 (9.2) |

| Mean SS diameter, mm (SD) | 4.0 (0.6) |

| Aneurysms treated with ≥ 1 SS, n (%) | 21 (6.7) |

| Total technical success, n (%) | 313 (99.7) |

| Procedural characteristics | |

| Platelet aggregation assay therapeutic, n (%) c | 228 (82.3) |

| Intraprocedural heparin use, n (%) | 273 (98.6) |

| Access, n (%) | |

| Femoral artery | 244 (88.1) |

| Radial artery | 32 (11.6) |

| Carotid artery cutdown | 1 (0.4) |

| Intraprocedural adjunctive techniques, n (%) | |

| Balloon-assisted angioplasty | 110 (39.7) |

| Stent | 30 (10.8) |

| Coil | 21 (7.6) |

| Postprocedural antiplatelet regimen, n (%) | |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel | 242 (87.4) |

| Aspirin + ticagrelor | 22 (7.9) |

| Other d | 13 (6) |

| Intraprocedural technical complications, n (%) | |

| Fish-mouthing of the distal end of the SS | 17 (6.1) |

| Poor wall apposition | 21 (7.6) |

| Foreshortening | 3 (1.1) |

| Procedural clinical complications, n (%) | |

| Contrast neurotoxicity | 5 (1.8) |

| Vessel dissection | 3 (1) |

| Vessel spasm | 2 (1) |

| Vessel perforation | 1 (0.4) |

SD = standard deviation; PCoA = posterior communicating artery; AchA = anterior choroidal artery; SCA = superior cerebellar artery; ACA = anterior cerebral artery; PCA = posterior cerebral artery; SS = surpass streamline.

Basilar, unknown; b 3 cases in each location respectively; c Therapeutic value was defined by each center; d 10 cases received aspirin + prasugrel and 3 cases received postprocedural eptifibatide for one day followed by aspirin + clopidogrel.

Technical and procedural characteristics

A total of 334 devices were implanted in 314 aneurysms (Table 2). Technical success was achieved in 313 (99%) cases. In 244 (88%) cases, femoral access was selected, while radial was used in 32 (12%) cases. Intraprocedural heparin was administered in 273 (99%) patients. The mean number of implanted FDs per aneurysm was 1.06 (range 1–3). The mean device diameter was 4.0 ± 0.6 mm and length 25.6 ± 9.2 mm.

A therapeutic preprocedural platelet aggregation assay was performed in 228 (82%) cases. Balloon-assisted angioplasty was employed in 110 (40%) procedures, stenting in 30 (11%), and coiling in 21 (8%). The treating centers selected a post-procedural antiplatelet regimen. The most common regimen was aspirin plus clopidogrel in 242 (87%), followed by aspirin plus ticagrelor in 22 (8%) cases. Intraprocedural technical complications were seen in 41 (14%) of the 282 procedures. Fish mouthing of the distal end occurred in 17 (6%), poor wall apposition in 21 (8%), and foreshortening in 3 (1%) cases. The most common intraprocedural clinical complication was contrast neurotoxicity in 5 (2%) patients, followed by vessel dissection and vessel spasm in 3 (1%) cases, respectively (patients were asymptomatic). Vessel perforation was encountered in 1 (0.4%) case.

Clinical and radiographic outcomes

Clinical and radiological outcomes are displayed in Table 3. Final follow-up at >12 months was completed in 239 (86%) patients; of these, Raymond-Roy Class I was observed in 194 (81.2%), Raymond-Roy Class II in 21 (9%), and Raymond-Roy Class III in 27 (11%). The primary efficacy composite endpoint was achieved in 191 (80%) patients; these patients did not present significant (>50%) parent vessel stenosis and target aneurysm retreatment up to 12 months following the procedure. The first follow-up was completed at a median time of 6 months (interquartile range: 3–7 months). Initial follow-up between 6 to 12-months was obtained in 228 (82%) patients. Complete occlusion (Raymond-Roy Class I) was achieved in 166 (73%) patients, while Raymond-Roy Class II was observed in 29 (13%) and Raymond-Roy Class III in 33 (15%). Follow-up complications identified were the following: significant (>50%) parent vessel stenosis in 6 (3%) cases, target aneurysm retreatment in 8 (3%), in-stent thrombosis in 10 (4%) (none of the patients required medical or procedural management), device migration in 5 (2%), and spontaneous non-aneurysmal intracerebral hemorrhage in 3 (1%).

Table 3.

Safety and efficacy endpoints.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Primary efficacy composite endpoint a | 191 (80.0) |

| Raymond-Roy occlusion scale rates, n (%) | |

| 6-12-month b | |

| Raymond-Roy Class I | 166 (72.8) |

| Raymond-Roy Class II | 29 (12.7) |

| Raymond-Roy Class III | 33 (14.5) |

| >12-month a | |

| Raymond-Roy Class I | 194 (81.2) |

| Raymond-Roy Class II | 21 (8.8) |

| Raymond-Roy Class III | 27 (11.3) |

| Primary safety endpoint, n (%) | |

| Major ischemic stroke | 7 (2.5) |

| Treatment-related deaths | 2 (0.8) |

| Total mortality | 6 (2.2) |

| Secondary safety endpoint, n (%) | |

| Minor ipsilateral ischemic stroke | 15 (5.4) |

| Target aneurysm rupture/SAH | 3 (1.1) |

| Follow-up complications, n (%) a | |

| Significant (> 50%) parent vessel stenosis | 6 (2.5) |

| Target aneurysm retreatment | 8 (3.3) |

| In-stent thrombosis | 10 (4.2) |

| Device migration | 5 (2.1) |

| Spontaneous non-aneurysmal ICH | 3 (1.3) |

ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage.

239 patients completed a > 12-month imaging follow-up. b 228 patients completed a 6-12-month imaging follow-up.

The primary safety endpoint determined by major ipsilateral ischemic stroke was reported in 7 (3%) cases, and treatment-related deaths occurred in 2 (1%) cases. These patients expired during the target aneurysm flow diversion procedure hospitalization due to a major ipsilateral stroke; one occurred on day 3 of hospitalization, while the other presented on day 5. Secondary safety endpoint determined by minor ipsilateral ischemic stroke presented in 15 (5%) patients, five cases presented in the first day following the procedure. Of note, all the patients recovered completely without residual deficits. There were no intraprocedural thrombotic complications. Target aneurysm rupture/subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) was reported in 3 (1%) cases. Finally, four patients expired more than 100 days after successful flow diversion procedures of causes unrelated to the target aneurysm (subdural hematoma, stroke, medical reasons).

The multivariable logistic regression model indicated that the odds of complete aneurysm occlusion (Raymond-Roy Class I) were lower among patients with a history of carotid artery disease (OR: 0.26; CI: 0.68–1.00; p = .050), hypertension (OR: 0.29; CI: 0.12–0.68; p = .048) and patients with wide-necked aneurysms (OR: 0.90; CI: 0.82–0.98; p = .015) (Table 4 and Supplementary material Table S1). Due to the low percentage of death and major stroke encountered, a multivariable logistic regression could not be performed to explore the variables associated with the primary safety endpoint.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of factors associated with complete aneurysm occlusion.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 4.61 | 0.93–22.93 | 0.061 |

| Carotid artery disease | 0.26 | 0.68–1.00 | 0.050* |

| Hypertension | 0.29 | 0.12–0.68 | 0.005* |

| Smoking history positive | 1.91 | 0.86–4.25 | 0.112 |

| Stroke clinical presentation | 0.05 | 0.00–1.51 | 0.086 |

| Other symptoms at clinical presentation a | 2.22 | 0.76–6.50 | 0.148 |

| Neck width | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 | 0.015* |

| Balloon-assisted angioplasty and/or adjunctive stent | 0.92 | 0.42–2.00 | 0.825 |

Vertigo, dizziness, syncope, pain.

* Statistical significance at p ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

SESSIA is the first multicenter retrospective cohort study demonstrating that a 72 to 96 wire FD with a braided angle design technology is effective in treating a population of patients with predominantly wide-necked small and medium-sized aneurysms. At the first follow-up (between 6 to 12-months), the complete occlusion rate was 73%. Interestingly at the final follow-up (after 12-months), an incremental 81% complete obliteration rate was encountered. Despite its increased metal surface and mesh density, the SS maintained low rates of morbidity, mortality, and retreatment when compared to other 48 wire cobalt/chromium alloy FDs. 6 Hence, our findings suggest that in addition to microsurgery, FDs, including the SS can be considered as a safe and effective treatment option for the management of intracranial aneurysms.3,4,7,8,13–19

Our findings align with previously reported flow diversion studies evaluating similar outcomes.3,4,7,8,13–19 First, when compared to the SCENT study, in which the same implant was used, our study reported higher rates of complete obliteration at one-year follow-up (81% vs. 66%). 7 While demographics were similar, the size of aneurysms treated in SESSIA was smaller. The mean aneurysm diameter was 5.87 mm, while in the SCENT was 12 mm. 7 Previously reported literature shows that smaller aneurysm diameter has been associated with greater occlusion rates.20–22 Interestingly, small and anatomically simple aneurysms have a decreased risk of rupture.23,24 Therefore, the rationale for treatment over conservative therapy remains a challenging decision where factors such as medical comorbidities, family history of aneurysm rupture, and patient-specific variables (age, tobacco use, anxiety of rupture, antiplatelet therapy candidacy) need to be carefully assessed prior to offering treatment. 2

On further evaluation of studies that specifically included medium and small-sized aneurysms, the occlusion rates we observed are consistent with the Prospective Study on Embolization of Intracranial Aneurysms with the Pipeline Device (PREMIER) results, where the treated aneurysms had a smaller diameter (mean 5 mm) with an observed occlusion rate of 76.8% at 12 months. 2 We also report similar safety and procedural details. Furthermore, the PUFS trial reported a complete occlusion rate of 86.8% at 1-year follow-up in 108 patients with aneurysms ≤12 mm in size using three telescoping FDs in average, which is more than the average we reported (1.06 devices per aneurysm). 1

Bonafe et al. presented the largest prospective study evaluating the efficacy and safety of the p64 (Phenox, Bochum, Germany) FD in 420 patients with a mean aneurysm dome width of 6.99 ± 5.28 mm, they showed an 83.7% complete aneurysm occlusion rate at 375 ± 73 days. 25 These results are comparable to our complete occlusion rate finding considering that the aneurysms in our sample were also predominantly medium and small. Similarly, Briganti et al. studied the same outcomes and FD in 50 aneurysms (most of them small size) located in the ICA and found that the rate of complete aneurysm occlusion increased with time (60% of the aneurysms completely occluded at 3-months, 82% at 6-months, and 88% at 12-months). 14 Our findings also demonstrate an incremental efficacy with higher rates of complete aneurysm obliteration observed at later imaging follow-ups. Moreover, it opens a debate about the optimal time length in which non-occluded aneurysms should be followed before deciding to retreat. Finally, our multivariable regression analysis corroborated previously reported findings that show that the neck width remains as the main predictor of aneurysm obliteration, even in small-sized aneurysms. 21

In SESSIA, 93.3% of the patients were treated with a single device. The mean number of devices implanted per patient was 1.06. These results are consistent with the European FRED (EuFRED), SCENT, and PREMIER trials which reported single device usage for 96.4%, 88.3%, and 92.9% procedures, respectively.2,7,19 The SS maintains a constant pore density across the aneurysm neck by increasing the number of wires according to the diameter of the selected implant. A 3-mm SS has 48 wires, whereas a 5-mm SS has 96 wires. 26 In contrast to the Aneurysm Study of Pipeline In an observational Registry (ASPIRe) trial, where a higher number of patients (18.8%) were treated with multiple Pipeline devices, which might reflect the difference in the number of wires per device. For instance, the Pipeline FD has a construction of 48 wires regardless of diameter (which translates into larger diameter devices having a lower pore density).16,26 In our sample, a small group of 21 (6.7%) aneurysms were treated with more than one device. Only one aneurysm was treated with three devices. The advantage of avoiding using multiple stents in a randomly located telescoping fashion is the consistent control of device porosity, decreasing the risk of a side branch or perforator occlusion and associated ischemic complications. 26 As shown in experimental reports, the SS has the capability of maintaining a constant pore density throughout the entire aneurysm neck, which translates into increased flow diversion efficacy and aneurysm occlusion. 27

Parent artery stenosis identified months after FD treatment has been reported in 2 to 14% of the procedures. 28 This is influenced by factors such as intrinsic thrombogenicity of the endoluminal construct, the effectiveness of dual-antiplatelet therapy regimen (drug dosing and response), intrinsic coagulopathic disposition of the patient, degree of stenosis in the parent vessel, and the state of the blood flow through the construct relative to the alternative collateral vascular territories. 29 In our study, significant parent vessel stenosis was observed in around 3%, none of the patients required therapeutic management. Furthermore, this percentage did not increase over time despite the high mesh density of the implant.

Safety is considered a critical factor in the selection of flow diversion devices. 30 Ischemic strokes and intracranial hemorrhage are the adverse events that cause the highest morbidity and mortality to patients undergoing flow diversion procedures. We observed similar mortality rates (2%) to the previously published meta-analysis in flow diversion (2.8%) and decreased mortality in comparison to the SCENT study (all-cause mortality was 4%).3,7,15 The lower mortality rates in our study might reflect the smaller aneurysm size and decreased morphologic complexity. Moreover, it should be accounted that the more extended market availability of the device increases the interventionalists familiarity with the procedure (device performance, delivery system, and technique), which ultimately can dimmish the known associated procedural and periprocedural risks. 7 Furthermore, the lack of aneurysmal anatomical complexity in the treated lesions favors an increased procedural safety.

We encountered a 3% rate of major ipsilateral ischemic stroke, which is consistent with the 3.7% reported in a large, pooled population study, including the International Retrospective Study of Pipeline Embolization Device (IntrePED), Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms (PUFS), and ASPIRe trials. 17 In addition, the 5% rate of minor ischemic stroke was comparable to what has been reported in the PUFS, ASPIRe, SCENT, and IntrePED studies.1,7,16,18 Even though the selection of patients for treatment in clinical trials is more stringent, our data showed a low risk of thromboembolic events, which can be attributed to the high safety profile encountered at high volume centers with experienced neuro-interventionalists who have incremental experience in procedure performance, device selection, and aneurysmal characteristics. 31

In our study, we observed both poor wall apposition and fish mouthing of the distal end in a combined 13.7% of the cases. This finding is consistent with the 15.6% incomplete wall apposition reported in the PREMIER study. 2 Implant malposition during endovascular procedures is a technical complication associated with severe adverse events (thromboembolic complications and FD migration) that can lead to failure of the flow diversion procedure and, more importantly, an increased risk of life-threatening aneurysmal rupture or major ischemic events. 31 Clear guidelines to manage inadequate wall apposition are non-existent. 31 We noted a 40% rate of balloon-assisted angioplasty of the FD, which included the cases with suboptimal wall apposition (evidenced on the post-deployment DSA) and the cases with dysplastic vessels or complex anatomy. In both scenarios, angioplasty was performed to ensure optimal wall apposition. 11 This finding is higher than the 22% balloon angioplasty reported in PREMIER. 2 Our group also reported a similar study comparing SS with Pipeline and Pipeline Flex, where balloon-assisted angioplasty usage was more frequent in patients with SS to optimize the implant’s wall apposition. 32 The rate of adjuvant balloon-assisted angioplasty encountered can be explained by the limited self-expandability of SS due to a theoretical increase in the construct stiffness caused by its higher number of wires when compared to other devices (48 Pipeline vs. 72–96 SS) and also due to the proportion of cobalt to platinum in the chromium alloy construct. 33

Limitations

Even though this is a large, multicenter registry, there are several limitations inherent to the observational and pragmatic nature of the study, the most remarkable of them being its retrospective design. First, the study included different centers, interventionalists, and treatment protocols; therefore, selection bias based on vascular anatomy and aneurysm location should be considered. Second, the aneurysm size we included was < 10 mm, which differs from the SCENT study and does not allow for a direct comparison. The follow-up timing was not precisely scheduled for all the patients, and a 11% (30/277) of the sample was lost to follow-up. Furthermore, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic introduced significant challenges in standardizing the follow-up protocols. During the pandemic, most centers adjusted their protocols to decrease patient exposure risk. Even though the preferred clinical, surgical, and antiplatelet regimen protocols to treat the aneurysms were defined by the treating center, the heterogeneity in the management of the flow diversion procedures encountered offers data from a real-world experience. In addition, the antiplatelet regimens were not standardized, which could represent a confounder in the cases that presented hemorrhagic and thromboembolic complications. Finally, the coordinating center evaluated the validity and accuracy of the data. The primary and secondary endpoint data were collected retrospectively without core-lab adjudication; this can potentially account for underreporting bias of clinical events.

Conclusion

SESSIA represents the largest cohort study assessing the safety and efficacy of a braided cobalt/chromium alloy implant with 72–96 wires in a heterogenous United States population with predominantly small intracranial aneurysms. Our findings provide similar evidence of high procedural success, effective complete aneurysm occlusion, and low morbidity and mortality than previously published landmark trials after the treatment of small and medium-sized wide-necked aneurysms with a single SS FD in the majority of cases. The flow diversion field is rapidly evolving towards low-profile delivery systems that optimize flow dynamics and adapt to a wide variety of patient and aneurysm characteristics.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ine-10.1177_15910199221118148 for Safety and efficacy of the surpass streamline for intracranial aneurysms (SESSIA): A multi-center US experience pooled analysis by Juan Vivanco-Suarez, Alan Mendez-Ruiz, Mudassir Farooqui, Kimon Bekelis, Justin A Singer, Kainaat Javed, David J Altschul, Johanna T Fifi, Stavros Matsoukas, Jared Cooper, Fawaz Al-Mufti, Bradley Gross, Brian Jankowitz, Peter T Kan, Muhammad Hafeez, Emanuele Orru, Andres Dajles, Milagros Galecio-Castillo, Cynthia B Zevallos, Ajay K Wakhloo and Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez in Interventional Neuroradiology

Acknowledgements

Rita Rabinovich and Sarah Newman for the help with data collection and patient follow-ups.

Footnotes

Authors' note: Muhammad Hafeez is from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, United States and Emanuele Orru is from Department of Interventional Neuroradiology, Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, MA, United States and Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States.

- Juan Vivanco-Suarez: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Alan Mendez-Ruiz: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Mudassir Farooqui: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Kimon Bekelis: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Justin A. Singer: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Kainaat Javed: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- David J. Altschul: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Johanna T. Fifi: Writing – review & editing

- Stavros Matsoukas: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Jared Cooper: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Fawaz Al-Mufti: Writing – review & editing

- Bradley Gross: Writing – review & editing

- Brian Jankowitz: Writing – review & editing

- Peter T. Kan: Writing – review & editing

- Muhammad Hafeez: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Emanuele Orru: Data curation, Writing – review & editing

- Andres Dajles: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Milagros Galecio-Castillo: Writing – review & editing

- Cynthia B. Zevallos: Writing – review & editing

- Ajay K. Wakhloo: Writing – review & editing

- Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Conflicts of interest statement: Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez is a consultant for Medtronic and Stryker Neurovascular: modest Justin A. Singer is consultant, proctor, spears bureau, grant support, and site PI (Evolve Trial) for Stryker Neurovascular; consultant and speakers bureau for Medtronic; part of the clinical events committee for Cerenovus. Fawaz Al-Mufti is consultant for Stryker, Penumbra and Cerenovus. Peter T. Kan is consultant for Stryker Neurovascular. Ajay K. Wakhloo is a consultant for Stryker Neurovascular: significant; Cerenovus JNJ: modest; receives research support from Philips Medical and a fellowship grant from Medtronic, co-founder and major stockholder in InNeuroCo, Deinde, and Neurofine. Stocks in ThrombX, RIST, NovaSignal. Analytics 4Life, Microbot. Johanna T Fifi is consultant for Stryker Neurovascular.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Stryker Neurovascular, (grant number 2020-HEM-006).

IRB approval number: 202005349

ORCID iDs: Juan Vivanco-Suarez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5326-1907

Kainaat Javed https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1328-7069

David J Altschul https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5130-1378

Stavros Matsoukas https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5902-0637

Jared Cooper https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4737-3026

Fawaz Al-Mufti https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4461-7005

Muhammad Hafeez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8631-4227

Cynthia B Zevallos https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8715-240X

Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3408-1297

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Becske T, Kallmes DF, Saatci I, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology 2013; 267: 858–868. 2013/02/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanel RA, Kallmes DF, Lopes DK, et al. Prospective study on embolization of intracranial aneurysms with the pipeline device: the PREMIER study 1 year results. J Neurointerv Surg 2020; 12: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrese I, Sarabia R, Pintado R, et al. Flow-diverter devices for intracranial aneurysms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 193–199. discussion 199-200. 2013/04/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters. Stroke 2013; 44: 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan TT, Chan KY, Pang PK, et al. Pipeline embolisation device for wide-necked internal carotid artery aneurysms in a hospital in Hong Kong: preliminary experience. Hong Kong Med J 2011; 17: 398–404. 2011/10/08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandapat S, Mendez-Ruiz A, Martínez-Galdámez M, et al. Review of current intracranial aneurysm flow diversion technology and clinical use. J Neurointerv Surg 2021; 13: 54–62. 2020/09/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers PM, Coon AL, Kan PT, et al. SCENT Trial. Stroke 2019; 50: 1473–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakhloo AK, Lylyk P, de Vries J, et al. Surpass flow diverter in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: a prospective multicenter study. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2015; 36: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. 2008/10/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merritt WC, Berns HF, Ducruet AF, et al. Definitions of intracranial aneurysm size and morphology: a call for standardization. Surg Neurol Int 2021; 12: 506–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eller JL, Dumont TM, Sorkin GC, et al. The pipeline embolization device for treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Expert Rev Med Devices 2014; 11: 137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raymond J, Roy D. Safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured aneurysms. Neurosurgery 1997; 41: 1235–1245. discussion 1245-1236. 1997/12/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender MT, Jiang B, Campos JK, et al. Single-stage flow diversion with adjunctive coiling for cerebral aneurysm: outcomes and technical considerations in 72 cases. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 843–850. 2018/05/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briganti F, Leone G, Ugga L, et al. Mid-term and long-term follow-up of intracranial aneurysms treated by the p64 flow modulation device: a multicenter experience. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briganti F, Napoli M, Tortora F, et al. Italian Multicenter experience with flow-diverter devices for intracranial unruptured aneurysm treatment with periprocedural complications--a retrospective data analysis. Neuroradiology 2012; 54: 1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W, Boccardi E, et al. Aneurysm study of pipeline in an observational registry (ASPIRe). Interv Neurol 2016; 5: 89–99. 2016/05/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W, Cekirge S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the pipeline embolization device for treatment of intracranial aneurysms: a pooled analysis of 3 large studies. J Neurosurg 2017; 127: 775–780. 2016/10/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallmes DF, Hanel R, Lopes D, et al. International retrospective study of the pipeline embolization device: a multicenter aneurysm treatment study. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2015; 36: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Killer-Oberpfalzer M, Kocer N, Griessenauer CJ, et al. European Multicenter study for the evaluation of a dual-layer flow-diverting stent for treatment of wide-neck intracranial aneurysms: the European flow-redirection intraluminal device study. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2018. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adeeb N, Moore JM, Wirtz M, et al. Predictors of incomplete occlusion following pipeline embolization of intracranial aneurysms: is it less effective in older patients? American Journal of Neuroradiology 2017; 38: 2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J-X, Lai L-F, Zheng K, et al. Influencing factors of immediate angiographic results in intracranial aneurysms patients after endovascular treatment. J Neurol 2015; 262: 2115–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender MT, Colby GP, Lin LM, et al. Predictors of cerebral aneurysm persistence and occlusion after flow diversion: a single-institution series of 445 cases with angiographic follow-up. J Neurosurg 2018; 130: 259–267. 2018/03/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mocco J, Brown RD, Jr., Torner JC, et al. Aneurysm morphology and prediction of rupture: an international study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms analysis. Neurosurgery 2018; 82: 491–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiebers DO. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. The Lancet 2003; 362: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonafe A, Perez MA, Henkes H, et al. Diversion-p64: results from an international, prospective, multicenter, single-arm post-market study to assess the safety and effectiveness of the p64 flow modulation device. J Neurointerv Surg 2021. neurintsurg-2021-017809. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vries J, Boogaarts J, Van Norden A, et al. New generation of flow diverter (surpass) for unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a prospective single-center study in 37 patients. Stroke 2013; 44: 1567–1577. 20130516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadasivan C, Cesar L, Seong J, et al. An original flow diversion device for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: evaluation in the rabbit elastase-induced model. Stroke 2009; 40: 952–958. 20090115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macdonald IR, Shankar JJS. Delayed parent artery occlusions following use of SILK flow diverters for treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potts MB, Shapiro M, Zumofen DW, et al. Parent vessel occlusion after pipeline embolization of cerebral aneurysms of the anterior circulation. Journal of Neurosurgery JNS 2017; 127: 1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierot L, Spelle L, Berge J, et al. SAFE Study (safety and efficacy analysis of FRED embolic device in aneurysm treatment): 1-year clinical and anatomical results. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kühn AL, Rodrigues KM, Wakhloo AK, et al. Endovascular techniques for achievement of better flow diverter wall apposition. Interv Neuroradiol 2019; 25: 344–347. 2018/11/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feigen CM, Vivanco-Suarez J, Javed K, et al. Pipeline embolization device and pipeline flex vs surpass streamline flow diversion in intracranial aneurysms: a retrospective propensity-score matched study. World Neurosurg 2022. 20220210. DOI: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jee TK, Yeon JY, Kim KH, et al. Early clinical experience of using the surpass evolve flow diverter in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2022; 64: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ine-10.1177_15910199221118148 for Safety and efficacy of the surpass streamline for intracranial aneurysms (SESSIA): A multi-center US experience pooled analysis by Juan Vivanco-Suarez, Alan Mendez-Ruiz, Mudassir Farooqui, Kimon Bekelis, Justin A Singer, Kainaat Javed, David J Altschul, Johanna T Fifi, Stavros Matsoukas, Jared Cooper, Fawaz Al-Mufti, Bradley Gross, Brian Jankowitz, Peter T Kan, Muhammad Hafeez, Emanuele Orru, Andres Dajles, Milagros Galecio-Castillo, Cynthia B Zevallos, Ajay K Wakhloo and Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez in Interventional Neuroradiology