Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cervical spine injuries in neonates are rare and no guidelines are available to inform management. The most common etiology of neonatal cervical injury is birth-related trauma. Management strategies that are routine in older children and adults are not feasible due to the unique anatomy of neonates.

OBSERVATIONS

Here, the authors present 3 cases of neonatal cervical spinal injury due to confirmed or suspected birth trauma, 2 of whom presented immediately after birth, while the other was diagnosed at 7 weeks of age. One child presented with neurological deficits due to spinal cord injury, while another had an underlying predisposition to bony injury, infantile malignant osteopetrosis. The children were treated with a custom-designed and manufactured full-body external orthoses with good clinical and radiographic outcomes. A narrative literature review further supplements this case series and highlights risk factors and the spectrum of birth-related spinal injuries reported to date.

LESSONS

The current report highlights the importance of recognizing the rare occurrence of cervical spinal injury in newborns and provides pragmatic recommendations for management of these injuries. Custom orthoses provide an alternate option for neonates who cannot be fitted in halo vests and who would outgrow traditional casts.

Keywords: cervical spine injury, orthoses, neonate

ABBREVIATIONS: CT = computed tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, OTS = off-the-shelf, SCI = spinal cord injury

Neonatal spine injury is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 29,000.1 Furthermore, injury to the spinal cord was identified in 10% of perinatal neonatal deaths or stillbirths at autopsy.2 Birth-related spinal cord injury (SCI) is thought to occur secondary to excessive extraction, rotation, or hyperextension of the neck during delivery; as such, shoulder dystocia, breech position, and forceps or vacuum assistance have emerged as risk factors for neonatal SCI. The clinical manifestation of SCI in this population can be significant, with a ranging spectrum of sensorimotor deficits and sometimes apnea, necessitating ventilation.1 Neonates are at higher risk of upper cervical spine injuries because of underdeveloped muscles and ligaments, relative craniocervical size mismatch, and incomplete mineralization of the vertebrae.3 Based on existing literature, the prognosis of birth-related SCI in neonates is poor, with a high mortality rate and long-term neurological morbidity among surviving patients.1,4,5

SCI in the pediatric population can be classified based on the radiographic appearance: fracture, fracture with subluxation, subluxation alone, and SCI without radiographic abnormality.6 Treatment is centered around providing appropriate immobilization, reduction, and stabilization in order to achieve spinal stability while mitigating permanent neurological deficits and long-term sequelae, including joint contractures, fractures, and scoliosis.2,7,8 Current treatment modalities include surgical stabilization and external immobilization systems.9 Surgery is particularly challenging in newborns due to their unique anatomy, the potential impact on growth, and difficulty achieving adequate internal fixation given bone immaturity.6 Patient factors in favor of orthotic treatment in the current literature include the absence of neurological abnormalities, absence of spinal deformity, young age with mild or moderate dynamic instability, and lesion of a single spinal level.9 Various types of external orthoses have been designed to stabilize the craniovertebral junction, most of which are not suited to the neonatal population.3 Halo immobilization, for example, carries inherent risks such as pin penetration due to thin bone, deformation of the skull, infection, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and pin loosening.10 Noninvasive immobilizers such as cervical-thoraco-lumbo-sacral are often not useful for neonatal SCI due to the patients’ small size and unique stature, often necessitating custom orthoses.

To date, there are no established guidelines describing the ideal management of neonatal spinal column injury and the existing literature primarily reports severe SCI phenotypes.4,11 Moreover, the evidence on the use of custom-fabricated cervical-thoraco-lumbo-sacral orthoses immobilizers in neonates is sparse. The duration of nonoperative treatment of neonatal SCI remains nonstandardized. The following case series describes the use of custom orthoses to successfully treat complex upper cervical spinal injuries in a series of newborns at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. We further present results of a narrative literature review focused on cervical birth–related SCI in neonates.

A 5-year retrospective database search of the period from January 1, 2017, to July 31, 2022, at the Hospital for Sick Children was performed for the diagnostic code of SCI and an injury date of less than 4 weeks of life to specify a neonatal population. For each record identified, demographic details, radiographic information, treatment specifics, and follow-up information were extracted.

Upon referral for custom orthosis, the orthotist with the neurosurgery team seeks to clarify the specific details pertaining to the child and their injury to determine if an off-the-shelf (OTS) device is appropriate. When treating newborns and infants, OTS devices available on the market do not reflect the general anatomy and a custom device is universally needed in our experience.

In considering the design of the orthosis, several factors are considered (Table 1). These relate to the presumed level and extent of instability, associated injuries, age of the child (specifically overall growth and hip stabilization with diaper use), as well as the expected length of time that the orthosis will be worn (with respect to selection of pressure-sensitive materials, positional plagiocephaly, and child hygiene).

TABLE 1.

Considerations for the design of custom orthoses in neonates

| Considerations | |

|---|---|

| Extent of instability |

|

| Associated injuries |

|

| Age of child |

|

| Overall growth (vol & height) |

|

| Hip stabilization w/ diaper use |

|

| Expected length of wear |

|

| Pressure-sensitive materials |

|

| Hygiene |

|

| Plagiocephaly |

In collaboration with the neurosurgical team, the orthotist creates the form to fabricate the custom device based on measurements obtained from the patient. The form is created using computer-aided design and is then carved out of foam. The device is fabricated with high-temperature thermoplastic molded over a liner made of several layers of pressure-sensitive ethylene-vinyl acetate foam (Fig. 1). Additional padding is added at the apex of the occiput to reduce risk of a pressure ulcer developing. The liner can be adjusted for growth by removing layers of foam as the patient increases in weight and height.

FIG. 1.

Custom neonate-sized cervical-thoraco-lumbo-sacral orthoses. Orthotics are designed as outlined with considerations for stability, age, and expected length of wear.

The occipital piece with temporal flanges is connected to the torso section by a rigid metal bar, which allows for adjustments to the alignment of the neck and head. The entire brace is lined with a removable fabric liner to allow for frequent cleaning of the brace. The chest piece acts as a point of stabilization, as well as an attachment point for the straps. The head strap is anchored on the head by using a silicone-style pad. The hip straps, with the use of a wide pelvic suspension pad, prevent distal translation of the patient out of the brace. The torso section is extended past the gluteal/diaper region to maintain a neutral pelvis with respect to the torso.

We additionally used a combination approach of bibliographic review and narrative literature review using PubMed database searching. Nonsystematic methods were used; advanced searches using Boolean operators specifying neonatal age demographic and traumatic or birth-related SCI yielded included articles. Due to differing imaging modality availability and clinical decision making, the decision was made to include studies from January 2000 to August 2022.

Illustrative Cases

Over a 5-year period, 3 neonates with suspected neonatal birth trauma presented to the attention of the neurosurgical service with cervical spine injury and suspected instability requiring custom-fabricated external orthotics (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of neonatal cervical spine injuries treated with custom orthoses

| Factor | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation |

8 hrs |

6 hrs |

7 wks |

| Presumed etiology |

Birth related |

Birth related |

Birth related |

| Underlying condition |

None |

None |

Infantile malignant osteopetrosis |

| Injury type |

Occipito-cervical ligamentous injury |

Cervical ligamentous injury & C1 fracture |

C2 bilat fracture of pars interarticularis |

| Spinal cord injury |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Duration in orthosis |

3 mos |

4 mos |

2 mos |

| Final alignment |

Maintained |

Maintained |

Maintained |

| Complication | None | Plagiocephaly | None |

Case 1

The first neonate presented to neurosurgical attention 8 hours after birth. He was born at 40 + 2 weeks’ gestation by vaginal delivery, requiring 2 attempts of vacuum and 1 attempt at forceps extraction. The newborn had meconium staining, intermittent apneic events, and suspicion of seizure activity, with significant subgaleal swelling. His birth weight was 2700 g. His neurological examination was nonfocal with initially general hypotonia that quickly improved.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a subgaleal hematoma and retroclival hematoma with associated STIR (short tau inversion recovery) hyperintensity posterior to the occiput and C1–2 concerning for possible occipitocervical ligamentous injury (Fig. 2).

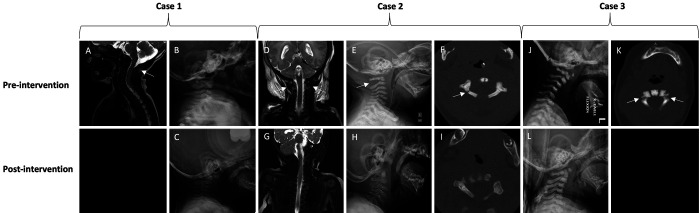

FIG. 2.

Case 1. Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) MRI (A) demonstrating signal suggestive of ligamentous injury. Initial radiograph (B) demonstrating no fractures and stable alignment. Six-month radiograph (C) after completing treatment. Case 2. STIR MRI (D) demonstrating signal suggestive of ligamentous injury. Initial radiograph (E) demonstrating widening of C1–2 posteriorly (arrow). Initial CT (F) demonstrating right posterior arch fracture (arrow). Four-month imaging (G–I) after completion of treatment. Case 3. Initial radiograph (J) demonstrating kyphosis and mild anterolisthesis of C1 on C2. CT (K) demonstrating bilateral pars interarticularis fracture. Two-month radiograph (L) after completing treatment.

He was maintained flat in bed and fitted with a custom orthosis for cervical immobilization. Follow-up radiographs after fitting of the orthotic demonstrated adequate alignment in the brace. The brace was worn for 3 months, after which delayed imaging showed stable alignment and it was discontinued. At 6-month follow-up, the patient continued to remain neurologically intact with excellent neck and head control.

Case 2

The second child presented to neurosurgical attention 6 hours after birth. He was born at 41 + 0 weeks’ gestation with a birth weight of 3440 g. Antenatal care revealed suspected maternal immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Delivery was further complicated by failure to progress with an abnormal fetal heart rate tracing requiring attempts at vacuum assistance and forceps delivery, which were unsuccessful, prompting an emergency cesarian delivery. The newborn was apneic and hypotonic, requiring intubation and fluid resuscitation. On examination, he was noted to have weak grasp reflex bilaterally, mild right upper and lower extremity weakness, and generalized hypotonia. Cooling was initiated and the child required multiple transfusions for coagulopathy and treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a nondisplaced fracture of the right posterior arch of C1, and MRI confirmed ligamentous injury in addition to a high cervical spinal cord injury (Fig. 2). In addition, intracranial imaging revealed hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, subgaleal hemorrhage, bilateral subdural collections, caput succedaneum, and a cephalohematoma.

Initial cervical spine precautions were maintained with gel rolls and bolsters until the custom orthosis was fabricated. Radiography in the orthosis indicated adequate cervical spine alignment, and delayed MRI 4 months following the initial insult demonstrated significant improvement in cord signal change and soft tissue edema. His brace was discontinued at 4 months. One year after initial injury, the child made a good neurological recovery and follow-up radiographs demonstrated stable cervical spine alignment. His treatment course was complicated by notable positional plagiocephaly when the orthosis was discontinued, which had improved significantly at the time of last follow-up. At follow-up, his strength and tone were normal on the left with mild right lower extremity weakness greater than upper extremity weakness and right-sided hyperreflexia. It is difficult to attribute the neurological findings to either the hypoxic brain injury or the high cervical cord injury, although they may reflect a combination of etiologies.

Case 3

The third child was brought to neurosurgical attention at 7 weeks of age following investigations for suspected infantile malignant osteopetrosis. As part of his workup, a dedicated cervical spine CT was acquired, which incidentally demonstrated bilateral fractures of the pars interarticularis of C2 with resultant translation-rotation of C1 over C2 and superior displacement of the anterior arch of C1 (Fig. 2). While there was no clear history of birth-related trauma, his injuries were suspected to have occurred at the time of birth. On examination, he was neurologically intact.

He was similarly fitted in a custom orthosis to maintain alignment and support healing. His orthosis was discontinued after 8 weeks when repeat radiography demonstrated stable alignment and healing of the C2 fracture. He remained clinically stable with no neurological deficits and proceeded to bone marrow transplant as primary treatment of his condition.

Discussion

Observations

Cervical SCI in neonatal populations is rare and there are no guidelines available to inform their management. There will likely be a continual increase in the rate of diagnosis due to the availability of MRI, which further underscores the importance of developing management approaches. Here we present a contemporary institutional series of neonates treated using custom external orthoses for neonatal upper cervical SCI. Pragmatic design and fabrication criteria are described to facilitate the treatment of this particularly vulnerable and understudied patient population.

The literature pertaining to neonatal cervical SCI is skewed to severe injuries, with sparse reporting of bracing techniques, duration, and approaches. Our narrative literature review identified 11 studies reporting 19 cases of perinatal cervical SCI (Table 3).1,2,4,5,12–18 This review corroborated previous risk factors of breech position, shoulder dystocia, vacuum/forceps assistance, and fetal macrosomia for perinatal cervical SCI. In our series, we identified forceps and vacuum assistance but did not report either macrosomia or fetal presentation risk factors. Most of these patients had severe clinical symptoms, with 10 requiring mechanical ventilation, and there were 5 neonatal mortalities reported. Only 1 patient with a C4/5 spondyloptosis with cord compression and bilateral C5 pedicle fractures underwent anterior and posterior surgical stabilization with autologous rib grafting and orthotic bracing. No groups reported custom orthosis use as the primary means of stabilization and treatment. Unlike previously reported cases demonstrating major neurological morbidity, the 3 cases highlighted in this series had favorable neurological findings and outcomes despite their cervical injuries and were successfully managed with custom orthosis. To the best of our knowledge, this case series is the first to detail the orthotic considerations, fitting, and usage of these custom orthotics in neonates for cervical SCI.

TABLE 3.

Narrative review results detailing operative and nonoperative management of neonatal perinatal cervical spinal cord injury with reported outcomes from January 2000 to August 2022

| Authors & Year | No. of Pts | Sex | Presentation | Pregnancy Details/Birth Weight | Delivery History | Cervical Injury | Clinical Presentation | Outcome/Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 20201 |

1 |

M |

Cephalic |

37 & 3/7 wks, 3220 g, regular antepartum exams |

Vaginal delivery w/ no instrument assistance |

12 × 2 × 1-mm hemorrhage at C2 level |

Mechanical ventilation, decreased muscle power of upper, voice hoarseness, feeding difficulty, & hypercapnia |

3 wks of steroid Tx & ventilator support; discharged at 2 mos; at 4-mo FU, pt had good movement of 4 limbs but mild hypertonia of limbs w/ clonus |

| Caird et al., 20052 |

1 |

M |

Breech |

Term delivery, 3940 g; mother did not attend all prenatal visits |

Patient presented in labor, forceps-assisted breech delivery w/ head entrapped for ∼25 mins |

C5–6 pst dislocation; MRI showed spinal cord edema from C1–6 |

Mechanical ventilation; no spontaneous respiration or movement; poor rectal tone; no DTR |

Mechanical ventilation; methylprednisolone & antibiotics; mortality in neonatal period |

| Vialle et al., 20074 |

6 |

M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

Cephalic (n = 3), breech (n = 2), face (n = 1) |

Uneventful pregnancies; mean weight 3333 g; term pregnancies, mean 38 wks |

Entrapment of head (n = 2), forceps extraction (n = 2), uneventful (n = 1) & pulled by arms (n = 1); there was 1 case of shoulder dystocia |

C1–2 dislocation w/ cord contusion (n = 1), C4–5 dislocation w/ cord contusion (n = 1), C2–3 contusion w/ out bony injury (n = 1), C6 vertebral body fracture w/ C5–7 contusion (n = 1), C6–7 section w/ epidural hematoma (n = 1), C1–2 ischemic change w/ out bony injury |

Flaccid tetraplegia (n = 3), flaccid tetraplegia w/ ventilator dependence, partial tetraparesis (n = 1), respiratory difficulty w/ rt upper monoplegia (n = 1) |

No demonstrated neurological improvement in all cases (n = 6); death in neonatal period due to respiratory complications (n = 1), death from delayed respiratory complications in childhood (n = 2), alive at last FU (n = 3) |

| Saleh et al., 20185 |

1 |

M |

NS |

38 wks, no specified birth weight |

Abdominal dystocia, requiring substantial force to head & neck for extraction; use of forceps NS |

C4–5 spondyloptosis w/ cord compression, bilat C5 pedicle fractures; delayed diagnosis due to hypotonia & postnatal focus on repairing abdominal dystocia (hydronephrosis w/ kidney rupture & ascites) |

Mechanical ventilation, absent hand movement, 1–2/5 power in proximal upper extremities & triple flexion in lower extremities bilaterally; absent extremity sensation |

Sandbag immobilization followed by attempted closed reduction & bracing (unsuccessful). Subsequent ant C5 corpectomy & C4–6 fusion w/ C2–7 pst fusion using autologous rib grafts. Custom Minerva orthosis used postoperative for 8 mos. Tracheostomy eventually decannulated by 9 mos of life. By 3 years the patient was walking independently, w/ ongoing asymmetrical upper extremity weakness. |

| Habek, 202112 |

1 |

M |

Cephalic |

Unknown maternal diabetes, 6100 g (macrosomia); term pregnancy, 40 wks |

Vaginal, vacuum w/ Kristeller’s expression, eventual shoulder dystocia & Barnum maneuver |

Findings of cervical cord laceration, dislocation of C6/7 & rupture of ant longitudinal ligament |

Severe peripartum asphyxia, flaccid tetraplegia |

None; mortality in neonatal period |

| Mills et al., 200113 |

4 |

NS |

Cephalic (n = 4) |

Term deliveries (n = 4); no birth weights; uncomplicated pregnancies |

Forceps use (n = 4) for deep transverse arrest in all cases |

Cervicomedullary hemorrhage & edema w/ extension to subaxial cervical spine (n = 3); postmortem finding of cord transection (n = 2), necrosis & hemorrhage (n = 1). In 1 neonate, there was cervical T2 hyperintensity most pronounced at C3. |

All cases had areflexia, flaccidity, reduced respiratory drive requiring mechanical ventilation. |

Mortality in n = 3 cases w/ out any specific management. In the neonate w/ edema at C3, there was progressive improvement leading to extubation at 7 days & was neurologically normal at 6 mos. |

| Morgan & Newell, 200014 |

1 |

M |

Cephalic |

Term + 11 days induction, variable decelerations led to C-section delivery, 4300 g |

C-section, uncomplicated |

C4–5 spinal cord discontinuity & C5–7 fluid attenuation w/ evidence of inferior spinal cord atrophy |

Mechanical ventilation dependent, severe hypotonia, absent DTR, withdrawal of lower limbs to touch |

None; mortality in neonatal period |

| Goetz, 201015 |

1 |

M |

Cephalic |

Term, unremarkable prenatal period |

Vaginal delivery w/ no instrument assistance |

Foramen magnum hematoma |

Bilat flaccid paralysis of upper extremities, DTR absent in upper extremities |

No specific treatment. Slow improvement in functioning of rt upper extremity & minimal in lt upper extremity at FU. |

| Ul Haq & Gururaj, 201216 |

1 |

F |

Cephalic |

39 & 6/7 wks, unremarkable prenatal period, 3520 g |

Vaginal delivery w/ shoulder dystocia w/ hyper-extension of neck during labor |

C7-T1 dorsal hyperintensity w/ atrophy, cystic change & fibrotic bands; repeat MRI at 4 mos demonstrated near-total spinal cord transection at C7-T1 |

Hyporeflexia in all 4 limbs, weakness in upper extremities, bilat lower limb flaccidity & decreased power, axial hypotonia |

Treated w/ steroids for 1 wk. At 10-mo follow-up, no upper extremity weakness, sitting unsupported, improved lower motor power. |

| Fazzi et al., 201617 |

1 |

M |

Cephalic |

38 + 5/7 wks, 3460 g, uncomplicated pregnancy |

C-section, uncomplicated |

C3-T1 hyperintense signal in keeping w/ ischemia |

Bilat upper extremity hypotonia, absent DTR |

Tx w/ steroids. At 7 mos of age the infant presented w/ flaccid paralysis of upper extremities w/ marked muscular atrophy despite physical therapy. |

| Fenger-Gron et al., 200718 | 1 | NS | Breech | Term | C-section, uncomplicated | C1 pst arch displacement w/ medullary compression, thought to have occurred prepartum | Mechanical ventilation, severe hypotonia w/ no spontaneous respiratory effort | No specific Tx; mortality in neonatal period |

ant = anterior; FU = follow-up; DTR = deep tendon reflex; Pts = patients; NS = not specified; Tx = treatment; pst = posterior.

Fundamentally, SCI in neonates differs from that observed in older children and adults due to differences in anatomy that warrant special considerations in management. Surgical treatment is often considered for individuals with markedly unstable injuries, irreducible dislocations, and incomplete injuries associated with progressive neurological symptoms.9 In patients with unstable fractures but normal spinal cord alignment, conservative management has been shown to be effective.9,19 In the neonatal population, surgical treatment is challenging, as instrumentation is not suitable and bony fusion with an autograft or allograft also requires immobilization for arthrodesis. Custom orthoses present an attractive alternative to facilitate healing and may be sufficient in this patient population for most injury types.

Lessons

We present pragmatic guidelines for the design of custom orthotics. Design considerations depend on the patient’s age, the severity and level of injury, the degree of neurological compromise, and the presence of associated injuries. The injury patterns sustained in our patients included both fractures and ligamentous injury. The orthoses were constructed from thermoplastic compounds molded to the child and anchored with straps, providing an alternate option for neonates who cannot be fitted in halo vests and who would outgrow traditional casts. Although 1 neonate developed positional plagiocephaly, none of the patients displayed functional restrictions of the cervical spine mobility at follow-up and all fractures healed in good alignment. Importantly, no new neurological deficits were encountered.

Although orthotics have several benefits, it is important to recognize the potential negative implications, such as difficulties with hygiene, skin breakdown, impact of immobilization on developmental progress, and stress on caregivers. Close observation of these patients through a strong interdisciplinary team can help mitigate preventable complications. The current work presents a consecutive institutional series with favorable outcomes, but the generalizability of these findings is limited by the small number of children included and retrospective nature of our study design.

Cervical spine injuries in neonates are rare and management algorithms are not standardized. Although injuries of this nature are associated with high mortality and morbidity in neonates, our cases highlight the importance of nonoperative management in select patients. Because of potentially adverse outcomes of an untreated injury, it is necessary to carefully manage these injuries to prevent neurological compromise. Management strategies that are routine in older children and adults are not feasible due to the unique anatomy of neonates. In this series, we present 3 neonates with varying degrees of cervical spine injuries all of which were treated successfully using custom-fabricated orthoses. Although custom devices can be challenging to develop and implement, a careful collaborative approach can lead to successful outcomes.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Ibrahim, Breitbart. Acquisition of data: Ibrahim, Karthikeyan, Breitbart, Fung, Short, Schmitz. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ibrahim, Karthikeyan, Fung, Lebel. Drafting of the article: Karthikeyan, Breitbart, Malhotra, Fung, Short, Schmitz, Lebel. Critically revising the article: Ibrahim, Karthikeyan, Breitbart, Malhotra, Fung, Short, Lebel. Reviewed submitted version of the manuscript: Karthikeyan, Breitbart, Malhotra, Fung, Lebel. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Ibrahim. Administrative/technical/material support: Lebel. Study supervision: Ibrahim.

References

- 1. Lee CC, Chou IJ, Chang YJ, Chiang MC. Unusual presentations of birth related cervical spinal cord injury. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:514. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caird MS, Reddy S, Ganley TJ, Drummond DS. Cervical spine fracture-dislocation birth injury: prevention, recognition, and implications for the orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(4):484–486. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000158006.61294.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexiades NG, Parisi F, Anderson RCE. Pediatric spine trauma: a brief review. Neurosurgery. 2020;87(1):E1–E9. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vialle R, Piétin-Vialle C, Ilharreborde B, Dauger S, Vinchon M, Glorion C. Spinal cord injuries at birth: a multicenter review of nine cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(6):435–440. doi: 10.1080/14767050701288325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saleh S, Swanson KI, Bragg T. Successful surgical repair and recovery in a 2-week-old infant after birth-related cervical fracture dislocation. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018;21(1):16–20. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.PEDS17105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Proctor MR. Spinal cord injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S489–S499. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kapapa T, Tschan CA, König K, et al. Fracture of the occipital condyle caused by minor trauma in child. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(10):1774–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Badman BL, Rechtine GR. Spinal injury considerations in the competitive diver: a case report and review of the literature. Spine J. 2004;4(5):584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duhem R, Tonnelle V, Vinchon M, Assaker R, Dhellemmes P. Unstable upper pediatric cervical spine injuries: report of 28 cases and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24(3):343–348. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Middendorp JJ, Slooff WB, Nellestein WR, Oner FC. Incidence of and risk factors for complications associated with halo-vest immobilization: a prospective, descriptive cohort study of 239 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):71–79. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shin JI, Lee NJ, Cho SK. Pediatric cervical spine and spinal cord injury: a national database study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41(4):283–292. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Habek D. Fatal neonatal spinal cord injury during shoulder dystocia. Childs Nerv Syst. 2022;38(1):5–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-021-05387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mills JF, Dargaville PA, Coleman LT, Rosenfeld JV, Ekert PG. Upper cervical spinal cord injury in neonates: the use of magnetic resonance imaging. J Pediatr. 2001;138(1):105–108. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgan C, Newell SJ. Cervical spinal cord injury following cephalic presentation and delivery by Caesarean section. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(4):274–276. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goetz E. Neonatal spinal cord injury after an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Pediatr Neurol. 2010;42(1):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ul Haq I, Gururaj AK. Remarkable recovery in an infant presenting with extensive perinatal cervical cord injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012007533. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fazzi A, Messner H, Stuefer J, Staffler A. Neonatal spinal cord injury after an uncomplicated caesarean section. Case Rep Perinat Med. 2016;5(1):73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fenger-Gron J, Kock K, Nielsen RG, Leth PM, Illum N. Spinal cord injury at birth: a hidden causative factor. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(6):824–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomaszewski R, Sesia SB, Studer D, Rutz E, Mayr JM. Conservative treatment and outcome of upper cervical spine fractures in young children: a STROBE-compliant case series. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100(13):e25334. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]