Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cranial radiotherapy (CRT) is an important treatment modality for malignancies of the central nervous system. CRT has deleterious effects that are commonly classified into acute, early delayed, and late delayed. Late-delayed effects include weakening of the cerebral vasculature and the development of structurally abnormal vasculature, potentially leading to ischemic or hemorrhagic events within the brain parenchyma. Such events are not well reported in the pediatric population.

OBSERVATIONS

The authors present the case of a 14-year-old patient 8.2 years after CRT who experienced intracerebral hemorrhage. Autopsy demonstrated minimal pathological change without evidence of vascular malformation or aneurysm. These findings were unexpected given the degree of hemorrhage in this case. However, in the absence of other etiologies, it was believed that late-delayed radiation effect was the cause of this patient’s fatal hemorrhage.

LESSONS

Although not all cases of pediatric spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage will have a determined etiology, the authors’ patient’s previous CRT may represent a poorly defined risk for late-delayed hemorrhage. This correlation has not been previously reported and should be considered in pediatric patients presenting with spontaneous hemorrhage in a delayed fashion after CRT. Neurosurgeons must not be dismissive of unexpected events in the remote postoperative period.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, cranial radiotherapy, late-delayed effects of radiotherapy, death, pediatric

ABBREVIATIONS: CRT = cranial radiotherapy, CT = computed tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

Cranial radiotherapy (CRT) is a common therapeutic modality for the primary and adjuvant treatment of central nervous system malignancies, and while it is effective, its use comes with consequences. The deleterious effects of CRT are well documented in the literature and can be classified as acute, early delayed, and late delayed.1 Late-delayed effects are mediated by damage to the vascular endothelium via radiation injury, causing upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and proangiogenic molecules. This leads to vascular compromise and the subsequent development of vascular malformations such as cavernoma, microbleeding, telangiectasia, moyamoya syndrome, and other conditions, including aneurysm formation.2–4

Following a review of the literature and a PubMed database search with the keywords “late-delayed,” “cranial radiation,” “radiotherapy,” “intracerebral hemorrhage,” and “death,” we present what we believe is a unique case in which a fatal hemorrhage occurred within the radiation field 8 years after CRT. Autopsy results are presented and do not demonstrate the expected severity of changes consistent with this patient’s presentation of intracerebral hemorrhage.

Illustrative Case

A 6-year-old female presented to our children’s hospital with symptoms of nausea and vomiting for 2 months. Neurological examination was nonfocal. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a fourth ventricular midline mass with extension into the foramen of Magendie and associated obstructive hydrocephalus (Fig. 1A and B). The patient was started on a course of dexamethasone, and her condition improved.

FIG. 1.

Preoperative axial post–gadolinium T1-weighted MRI (A) demonstrating a fourth ventricular avidly enhancing mass. Preoperative sagittal post–gadolinium T1-weighted MRI (B) demonstrating a fourth ventricular enhancing mass protruding through the foramen of Magendie. Six-month postoperative axial (C) and sagittal (D) post–gadolinium T1-weighted MRI demonstrating gross-total resection of the fourth ventricular enhancing mass.

Suboccipital craniectomy with C1 laminectomy was performed. The tumor presented in the midline through the foramen of Magendie, and resection was performed in an inferior to superior direction, splitting the vermis as appropriate. Gross-total resection of the tumor was achieved (Fig. 1C and D). The surgical procedure was uncomplicated, and at no time during resection was vascular injury appreciated. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7 with a nonfocal neurological exam. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion was not necessary. Pathology was consistent with classic ependymoma.

Radiotherapy was initiated 7 weeks postoperatively as follows. The posterior fossa received 23.4 Gy through parallel opposed lateral fields via 6-MV photons at 1.8 Gy per fraction. An additional 3.6-Gy boost was directed at the tumor bed through a 3-field setup of parallel opposed lateral fields and a vertex field. This was achieved via a combination of 6- and 18-MV photons at 1.8 Gy per fraction. In total, the patient received 54 Gy, with treatment lasting approximately 6 weeks.

Upon completion of the treatment, the patient was followed by neurosurgery and oncology with interval MRI surveillance to monitor for disease recurrence. Initially, routine follow-up with MRI was performed every 4 months and then at intervals of every 6 months during postoperative years 1–7. Neuroimaging remained stable without evidence of recurrence or vascular pathology in the observed period (Fig. 2). During the observed period, the patient demonstrated no sign of neurological or neurocognitive deficits.

FIG. 2.

Axial (left) and sagittal (right) post–gadolinium T1-weighted MRI performed 7.8 years post-CRT, showing stable postoperative change without vascular abnormality.

At 14 years of age, 8.2 years postradiation, the patient presented with headache, rapid neurological decline to coma, and respiratory arrest at an outside hospital. Head CT demonstrated hemorrhage in the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles as well as the medial right cerebellum (Fig. 3); diffuse cerebral edema and obstructive hydrocephalus were present. The patient was intubated, resuscitated, and stabilized. The patient was transferred to our children’s hospital. Neurological exam demonstrated fixed midposition pupils. Corneal reflexes, oculocephalic reflexes, gag, and cough were absent. The patient possessed intermittent spontaneous respirations. Chest radiography demonstrated florid neurogenic pulmonary edema (Fig. 4). With the continued need for aggressive resuscitation and significant pressor support, a do-not-resuscitate order was put in place. The patient was allowed to progress and subsequently died.

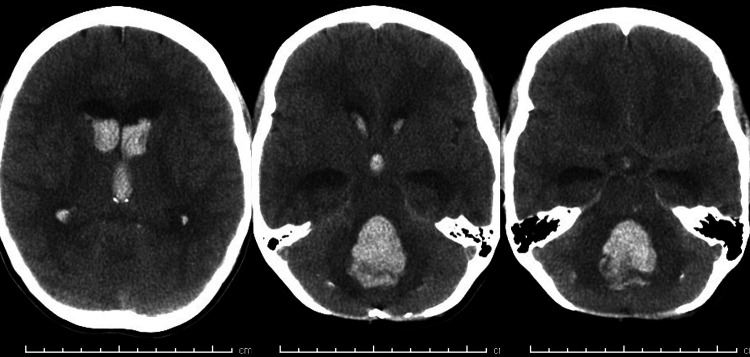

FIG. 3.

Noncontrast CT demonstrating intraparenchymal hemorrhage with extensive dissemination throughout the ventricular system occurring 8.2 years after CRT.

FIG. 4.

Chest radiograph demonstrating bilateral consolidations within the apices of the lung, consistent with neurogenic pulmonary edema occurring 8.2 years after CRT.

Autopsy examination demonstrated intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the pons and cerebellum without gross evidence of aneurysm or other vascular malformation. On microscopic examination, there was no evidence of vascular malformation, vasculitis, aneurysm, or tumor recurrence. Additional microscopic findings included a mild degree of demyelination by Luxol Fast Blue stains, mild hyalinization of vessels, mild gliosis, and mild macrophage infiltration in the cerebellar areas surrounding the fourth ventricle. These changes were believed to be associated with radiation effect, and in this case were minimal.

Discussion

Observations

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in children is a rare event, reported to occur in 0.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.5 The majority of intracerebral hemorrhages in children are associated with vascular pathologies such as arteriovenous malformation and cerebral aneurysm, accounting for 48% of cases. Tumor is associated with 9% of cases, and in 19% of cases no identifiable cause was determined. Medical causes of intracerebral hemorrhage include thrombocytopenia, coagulopathies, and infection—in total accounting for 23% of cases.6 Our patient represents an undefined risk of remote CRT while having found no evidence of vascular abnormalities, recurrent tumor, or severe radiation changes on autopsy.

Previously established late-delayed complications of CRT include radiation necrosis and cerebrovascular disease. The underlying pathophysiology between the two are seemingly indistinct: both beginning with endothelial damage and subsequent upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1) causing breakdown of the blood–brain barrier. Radiation necrosis manifests primarily as oligodendrocyte death, axonal demyelination, and liquefactive necrosis of the white matter. In contrast, cerebrovascular disease secondary to CRT affects the arterial vessels and capillaries of the brain, manifesting as acquired vascular malformation, structural weakness, and vascular occlusion.2,7 Their clinical presentations are grossly distinct. Radiation necrosis typically presents with neurological deficits and progressive neurocognitive decline, and the latter is demonstrated by a declining IQ in the years following the development of radiation necrosis.8 The late-delayed cerebrovascular complications result in structural and functional vascular changes such as cavernoma, microbleeding, telangiectasia, moyamoya syndrome, aneurysm, as well as vaso-occlusive and stenotic disease similar to atherosclerosis. These cerebrovascular complications can lead to devasting ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

Hemorrhage has a proven association with CRT, although the incidence remains unclear. Bowers et al.,9 Campen et al.,10 and Waxer et al.11 all reported a statistically significant increased risk of stroke in pediatric patients following CRT; however, their work did not differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic events, so we are unable to extrapolate a true or approximate risk of intracerebral hemorrhage as a result of CRT. Death associated with intracerebral hemorrhage following CRT in the pediatric population is rare. In a review of the literature, we found few reports of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage12,13 and only two references documenting a pediatric death from spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage.13,14 Chung et al.12 published a case report in 1992 that was believed to be the first documented case of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in a pediatric patient occurring 4.5 years following CRT; however, follow-up MRI 5 months later demonstrated that the hemorrhage had fully resolved. In 1995, Poussaint et al.14 performed a retrospective study of hemorrhagic vasculopathy in patients with a history of CRT for malignancy during childhood. This study identified 20 patients with evidence of intracerebral hemorrhage, 10 of whom had a history of primary brain tumor; only a single patient died due to intracerebral hemorrhage. Additionally, in another study, Haddy et al.15 investigated the relationship between the dose of radiation received and cerebrovascular mortality in an effort to predict the long-term risk of cerebrovascular mortality following CRT. Their study found 23 cerebrovascular deaths, 12 of which were from intracranial hemorrhage. In those 12 cases, the average age of death was 31.75 years; the only pediatric death occurred in a patient 11 years of age.

In comparing our case with the literature, we believe it to be the third reported case of death due to intracerebral hemorrhage associated with CRT in a pediatric patient. It is the first reported case of a late-delayed post-CRT spontaneous hemorrhage with a documented absence of vascular malformation or aneurysm. The patient reported by Poussaint et al.14 had a history of medulloblastoma treated with resection, radiation (total dose: 53.9 Gy), and chemotherapy. This patient and our patient received similar radiation doses, and both patients’ hemorrhages occurred within the pons. Histopathology was unavailable for Poussaint et al.’s case, so we are unable to comment on the etiology of the hemorrhage. In their 2011 study, Haddy et al.15 reported a single pediatric death due to intracerebral hemorrhage. This patient had a malignant glioma of the optic chiasm, which was treated with CRT. Again, similar radiation doses were administered; however, the cause of this patient’s intracerebral hemorrhage was due to a ruptured aneurysm. As previously mentioned, our patient did not have evidence of vascular malformation or aneurysm. All three patients were treated with similar radiation doses, with death occurring at a similar postradiation interval.

Additionally, in a review of the literature, several factors were found to increase the risk of radiation-induced cerebrovasculopathy and intracerebral hemorrhage, including radiation to the circle of Willis,16,17 radiation to the prepontine cistern,15 and a radiation dose >50 Gy.9 While our patient fell into all three high-risk categories, autopsy changes were minimal and inconsistent with the expected degree of radiation change. However, there were no alternative etiologies identified, so it was believed that the postradiation changes were indeed the cause of our patient’s intracerebral hemorrhage.

Finally, lifestyle and environmental factors such as smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension are also hypothesized to play a role in the development of post-CRT cerebrovascular disease.18 This patient’s hemorrhage occurred during adolescence without lifestyle or environmental factors present.

Lessons

In summary, we present the third documented case of a fatal intracerebral hemorrhage following CRT in a pediatric patient and the first case with the documented absence of vascular pathology. This is a unique case that would certainly not alter standard management or practice; however, it may represent a poorly defined late risk of CRT in the pediatric population and a potential avenue for further investigation. Furthermore, the case illustrates that the neurosurgeon must remain open to the possibility of unexpected events in the remote postoperative period and continue to participate in the care of these patients.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Farmer, Dilustro. Acquisition of data: Farmer, Dilustro. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the article: Farmer, Dilustro. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of the manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Conley. Administrative/technical/material support: Farmer. Study supervision: Dilustro.

References

- 1. Leibel SA, Sheline GE. Radiation therapy for neoplasms of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1987;66(1):1–22. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy ES, Xie H, Merchant TE, Yu JS, Chao ST, Suh JH. Review of cranial radiotherapy-induced vasculopathy. J Neurooncol. 2015;122(3):421–429. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris B, Partap S, Yeom K, Gibbs IC, Fisher PG, King AA. Cerebrovascular disease in childhood cancer survivors: a Children’s Oncology Group report. Neurology. 2009;73(22):1906–1913. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c17ea8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Passos J, Nzwalo H, Marques J, et al. Late cerebrovascular complications after radiotherapy for childhood primary central nervous system tumors. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;53(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fullerton HJ, Wu YW, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Risk of stroke in children: ethnic and gender disparities. Neurology. 2003;61(2):189–194. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078894.79866.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lo WD. Childhood hemorrhagic stroke: an important but understudied problem. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(9):1174–1185. doi: 10.1177/0883073811408424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rahmathulla G, Marko NF, Weil RJ. Cerebral radiation necrosis: a review of the pathobiology, diagnosis and management considerations. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(4):485–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Radcliffe J, Packer RJ, Atkins TE, et al. Three- and four-year cognitive outcome in children with noncortical brain tumors treated with whole-brain radiotherapy. Ann Neurol. 1992;32(4):551–554. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bowers DC, Liu Y, Leisenring W, et al. Late-occurring stroke among long-term survivors of childhood leukemia and brain tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5277–5282. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campen CJ, Kranick SM, Kasner SE, et al. Cranial irradiation increases risk of stroke in pediatric brain tumor survivors. Stroke. 2012;43(11):3035–3040. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.661561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waxer JF, Wong K, Modiri A, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular events among childhood and adolescent patients receiving cranial radiation therapy: a pediatric normal tissue effects in the clinic normal tissue outcomes comprehensive review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;114(3S):E486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung E, Bodensteiner J, Hogg JP. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a very late delayed effect of radiation therapy. J Child Neurol. 1992;7(3):259–263. doi: 10.1177/088307389200700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JK, Chelvarajah R, King A, David KM. Rare presentations of delayed radiation injury: a lobar hematoma and a cystic space-occupying lesion appearing more than 15 years after cranial radiotherapy: report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(4):1010–1014. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000114868.82478.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poussaint TY, Siffert J, Barnes PD, et al. Hemorrhagic vasculopathy after treatment of central nervous system neoplasia in childhood: diagnosis and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16(4):693–699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haddy N, Mousannif A, Tukenova M, et al. Relationship between the brain radiation dose for the treatment of childhood cancer and the risk of long-term cerebrovascular mortality. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 5):1362–1372. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aizer AA, Du R, Wen PY, Arvold ND. Radiotherapy and death from cerebrovascular disease in patients with primary brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2015;124(2):291–297. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Fayech C, Haddy N, Allodji RS, et al. Cerebrovascular diseases in childhood cancer survivors: role of the radiation dose to Willis circle arteries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(2):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mueller S, Fullerton HJ, Stratton K, et al. Radiation, atherosclerotic risk factors, and stroke risk in survivors of pediatric cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]