Abstract

BACKGROUND

Recurrent cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm syndrome (RCICVS) causes cerebral infarction, ocular symptoms, and occasionally chest pain accompanied by coronary artery vasospasm. The etiology and optimal treatment remain unclear.

OBSERVATIONS

The authors report a patient with drug-resistant RCICVS who underwent carotid artery stenting (CAS). Magnetic resonance angiography revealed recurrent vasospasm in the cervical segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA). Vessel wall imaging during an ischemic attack revealed vascular wall thickening of the ICA, similar to that in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. The superior cervical ganglion was identified at the anteromedial side of the stenosis site. Coronary artery stenosis was also detected. After CAS, the symptoms of cerebral ischemia were prevented for 2 years, but bilateral ocular and chest symptoms did occur.

LESSONS

Vessel wall imaging findings suggest that RCICVS is a sympathetic nervous system-related disease. CAS could be an effective treatment for drug-resistant RCICVS to prevent cerebral ischemic events.

Keywords: recurrent cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm syndrome, carotid artery stenting, vessel wall imaging

ABBREVIATIONS: 3D = three-dimensional, CAS = carotid artery stenting, CT = computed tomography, DANTE = delay alternating with nutation for tailored excitation, DSA = digital subtraction angiography, FDG-PET = fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography, ICA = internal carotid artery, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, PTA = percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, RCICVS = recurrent cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm syndrome, RCVS = reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, SCG = superior cervical ganglion

Recurrent cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm syndrome (RCICVS) is a rare disease characterized by paroxysmal vasospasm of the cervical segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA). This syndrome causes ocular symptoms, cerebral infarction, and occasionally chest pain accompanied by coronary artery vasospasm.1–3 However, its etiology and optimal treatment remain unclear. We reported a case of drug-resistant RCICVS in a patient who underwent carotid artery stenting (CAS). We also evaluated the findings of the vessel wall imaging of RCICVS to understand the pathomechanisms better. To our knowledge, this is the first vessel wall imaging study on RCICVS.

Illustrative Case

An 18-year-old male was admitted for recurrent symptoms such as headache, bruits in the left side of the neck, transient left amaurosis, and right hemiparesis. The patient had had these episodes since the age of 15 years, with attacks recurring once every 2 or 3 months. The patient had no vascular risk factors or family history of stroke.

Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the age of 16 years revealed a cerebral infarction in the left frontal lobe and severe stenosis of the ICA (Fig. 1A and B). Examination of known blood markers for thrombophilia, vasculitis, and collagen disease revealed no abnormalities. During each ischemic attack, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed severe stenosis of the cervical segment of the left ICA and the stenosis site was the same at each attack (Fig. 1C), whereas it showed no stenosis during the remission intervals (Fig. 1D). Three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) angiography during ischemic attack showed stenosis at the C1–2 level of the left cervical ICA. Transient stenosis at the cervical portion of the contralateral ICA was also asymptomatically detected, and coronary CT angiography showed mild stenosis with calcification at the proximal parts of the left anterior descending artery and the first diagonal artery. During the attacks, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) showed no uptake at the stenosis site. Vascular wall imaging during the attacks, as examined by delay alternating with nutation for tailored excitation (DANTE)-prepared MRI sequences, revealed vascular wall thickening with mild enhancement from the bifurcation over the petrous portion of the ICA, including the C1–2 level stenosis of the left cervical ICA (Fig. 2A and B). However, no vascular wall alteration suggestive of spasm, atherosclerotic plaque, intimal flap, or intramural hematoma was observed during the remission interval (Fig. 2C). The superior cervical ganglion (SCG) was identified at the anteromedial side of the stenosis site (Fig. 2D).4

FIG. 1.

MRI performed during an attack at the age of 16, revealing cerebral infarction in the left frontal lobe (A), with MRA showing severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery (B). MRA (C) during the attack showed severe stenosis at the cervical segment of the left ICA. The stenosis site is the same at each attack (white arrow). D: MRA performed during the remission interval, showing no stenosis at the left ICA.

FIG. 2.

During the attack, the DANTE-prepared MRI sequences reveal vascular wall thickening with mild enhancement (white double arrows, A and B) in the long segment of the ICA, from the bifurcation over the petrous portion (white arrows), including the stenosis (A, plain; B, enhancement by a contrast medium). During the remission interval, no vascular wall thickening is observed (C). Axial image (D) during the attack reveals that the stenosis site of the ICA (asterisk) is located just behind the superior cervical ganglion (arrowhead) and in front of the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve (double arrowheads).

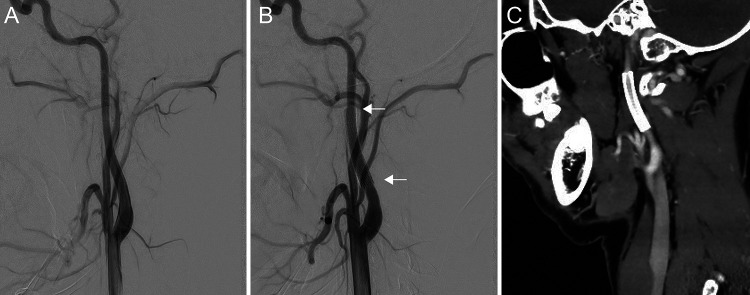

Ischemic attacks and ICA stenosis continuously occurred despite medication (calcium blockers and antiplatelet therapy). CAS was performed when the patient was 20 years old. Although digital subtraction angiography (DSA) before stenting showed no stenosis in the cervical segment of the left ICA (Fig. 3A), the stenosis site was confirmed by the findings of repeated MRA and 3D-CT angiography. Therefore, a self-expandable stent (6 × 30 mm; Precise, Cordis) was placed from the C1 to the C2 level of the left cervical ICA, with distal protection using FilterWire EZ (Boston Scientific). Postoperative DSA and 3D CT angiography indicated that the stent was deployed in the proper position (Fig. 3B and C). No cerebral ischemia was detected for 2 years after CAS, but bilateral ocular and chest symptoms did occur.

FIG. 3.

A: Left ICA angiography, lateral view, shows no stenosis before CAS. B: The stent is placed covering the stenosis region (white arrows, edges of the stent). C: Postoperative 3D-CT angiography demonstrates no stenosis and patency of the left ICA.

Discussion

Observations

RCICVS causes transient and recurrent headaches, cerebral ischemia, and ocular symptoms. From previous reports,1–3,5 repeated stenosis of the cervical portion of the ICA, especially at the level of C1–2, was only detected during the attacks, and in 69% of patients, stenosis occurred bilaterally.1 In addition, the coronary artery stenosis was occasionally detected in patients with RCICVS.1,6 As for the present case, amaurosis fugax and hemiparesis after vascular bruits and/or headache repeatedly occurred, and ipsilateral ICA stenosis was repeatedly detected solely during the attacks. Contralateral extracranial ICA stenosis occasionally occurred and coronary artery stenosis was detected. The imaging findings of the present case during the attack were similar to those of vasculitis, atherosclerotic plaque, and vascular dissection but could be differentiated from such diseases by the absence of stenosis or wall changes during the remission interval. The results of blood test and FDG-PET also showed no findings suggestive of vasculitis. Thus, RCICVS was diagnosed.

The treatment for RCICVS has not yet been established. Calcium blockers, antiseizure medications, antiplatelet therapy, or steroids do not completely prevent ischemic attacks in all patients.3 To our knowledge, endovascular treatment was performed in eight drug-resistant cases, including our case (Table 1).1,2,7–9 Three patients underwent percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) alone, and five patients underwent CAS. In two of the three patients who underwent PTA, ischemic symptoms occurred repeatedly.9 In the third case, no follow-up data were documented.7 On the contrary, in all five patients with stenting, there was no recurrence of cerebral ischemic episodes related to the lesion side, regardless of the stent type.1,2,8 Thus, stenting may be effective for drug-resistant cases to prevent cerebral ischemia. However, in two cases, including our case, ocular symptoms continued.2 Four of five patients,1,2,8 including our case, underwent CAS during the remission interval, whereas one patient underwent CAS during the attack due to severe ischemic symptoms. In a previous case of RCICVS,10 ocular symptoms by spasms of the ophthalmic artery were repeatedly induced by stimulation of catheter insertion. CAS during the remission interval may be suitable unless there are severe cerebral ischemic symptoms; however, further case accumulation will be necessary.

TABLE 1.

The summary of cases of recurrent idiopathic cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm with endovascular treatment

| Authors & Year | Age (yrs), Sex | Preoperative Symptoms | Affected Side | Location | Medication Before Endovascular Tx | Endovascular Tx (stent) | Cerebral Ischemia After Endovascular Tx (FU in mos) | Ocular Sx After Endovascular Tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dembo & Tanahashi, 20127 |

24, F |

Headache, ocular symptoms, hemiparesis |

Rt |

Rt ICA, C2 level |

Calcium antagonist, beta blocker |

PTA |

NA |

NA |

| Fujimoto et al., 20138 |

47, F |

Dysarthria, hemiparesis |

Rt |

Rt ICA, C1 level |

Dual antiplatelet therapy, calcium antagonist |

CAS (Wallstent) |

No (24) |

No |

| |

46, F |

Aphasia, ocular symptoms, hemiparesis |

Lt |

Lt ICA, C1–2 level |

Dual antiplatelet therapy, calcium antagonist |

CAS (Precise) |

No (24) |

No |

| Yoshimoto et al., 20141 |

40, F |

Aphasia, ocular symptom, hemiparesis |

Lt |

Lt ICA, C1–2 level |

Anticoagulant, calcium antagonist |

CAS (Wallstent) |

No (24) |

No |

| Takahira et al., 20172 |

40, M |

Bruits, headache, ocular symptom, hemiparesis |

Rt (occasionally lt) |

Bilat ICA, cervical portion |

Dual antiplatelet therapy, steroid, calcium antagonist, antiseizure medication |

CAS (Precise) |

No (6) |

Yes |

| Kim et al., 20209 |

18, M |

Headache, ocular symptom, hemiparesis |

Rt (occasionally lt) |

Bilat ICA, cervical portion |

Single antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulant, steroid |

PTA |

Yes (NA) |

Yes |

| |

22, M |

Ocular symptom, hemiparesis |

Rt (occasionally lt) |

Bilat ICA, cervical portion |

No medication |

PTA |

Yes (18) |

Yes |

| Present case | 20, M | Bruits, headache, ocular symptom, hemiparesis | Lt c(occasionally rt) | Bilat ICA, C1 level | Dual antiplatelet therapy, calcium antagonist | CAS (Precise) | No (24) | Yes |

NA = not available; Sx = symptom; Tx = treatment.

The etiology of RCICVS remains unknown. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system has been implicated because sympathetic activation by cold and mechanical stimuli induces ICA stenosis.11 In the present case, FDG-PET showed no uptake at the stenosis site. A meta-analysis showed that FDG-PET has high sensitivity (87%) and specificity (73%) for the diagnosis of large-vessel inflammation.12 However, in a previous study of FDG-PET and MRI in Takayasu’s arteritis, vessel wall thickness was occasionally negative on PET and positive on MRI.13 Thus, to explore the etiology of RCICVS, vessel wall imaging by MRI becomes important. In the present case, vessel wall imaging by MRI showed vessel wall thickening along the long segment of the ICA, with mild enhancement. These findings are similar to those of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS); the pattern of diffuse uniformity with or without mild enhancement was continuous throughout the entire wall of the diseased vessel.14 On the contrary, vasculitis shows vessel wall thickening in the short segments with concentric or eccentric enhancement.14 Intracranial atherosclerotic disease often shows areas of T2-weighted imaging hyperintensity in vessel wall imaging, whereas both RCVS and vasculitis rarely show these.15 Intracranial atherosclerotic disease also has eccentric wall thickening on T1-weighted imaging.15 In intracranial arterial dissections, the vessel wall imaging findings are characterized by an intimal flap and thrombus within the false lumen of dissection.16 The findings of vessel wall imaging in the present case were not similar to those in vasculitis, atherosclerotic disease or dissection, even during the attack. These results suggest that RCICVS has a pathogenesis more similar to RCVS than to other vascular diseases.

Additionally, the SCG was identified just anterior to the stenosis site by MRI. The SCG is usually located around the C2 level,4 and the proximity between the SCG and stenosis site may be relevant to why vasospasm mainly occurs at the C1–2 levels in RCICVS.3,5 As in the present case, ocular symptoms in RCICVS sometimes persist even after CAS.2 The SCG branch supplies the ICA,17 and autonomic nerves from the internal carotid plexus continue to the adventitia of the ophthalmic artery.18 In a case report of DSA,10 simultaneous vasospasm of the cervical portion of the ICA and ophthalmic artery repeatedly occurred during catheter insertion into the cervical portion of the ICA. This case report reinforces the connection between the ICA and the ophthalmic artery. The connection between the SCGs and the ophthalmic artery may be responsible for residual ocular symptoms even after CAS. Coronary artery stenosis is occasionally found in RCICVS, as in the present case.1,6 The fact that the SCGs also have a cardiovascular branch17 may be the cause of coronary artery vasospasm. Thus, these findings suggest that the etiology of RCICVS may be related to the sympathetic nervous system.

Lessons

The findings of the vascular wall imaging support the hypothesis that the etiology of RCICVS may be related to the sympathetic nervous system, especially the SCGs. Stenting may be an effective treatment for drug-resistant RCICVS to prevent cerebral ischemic events; however, not all symptoms were prevented by stenting, and additional case studies are required.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Grinstead and Sinyeob Ahn for the DANTE-prepared MRI.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Tokunaga, Yamao, Maki. Acquisition of data: Tokunaga, Yamao, Maki, Miyake, Yasuda. Fushimi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Tokunaga, Yamao, Maki. Critically revising the article: Tokunaga, Yamao, Maki, Ishii, Abekura, Okawa, Kikuchi, Fushimi, Yoshida, Miyamoto. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Tokunaga, Yamao, Maki. Study supervision: Ishii, Yoshida, Miyamoto.

Supplemental Information

Previous Presentations

This research was presented as an e-poster at the 81st annual meeting of the Japan Neurosurgical Society, Yokohama, Japan, September 28–October 1, 2022.

References

- 1. Yoshimoto H, Asakuno K, Matsuo S, et al. Idiopathic carotid and coronary vasospasm: a case treated by carotid artery stenting. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(12) suppl 12:S461–S464. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.143721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahira K, Kataoka T, Ogino T, et al. Treatment of idiopathic recurrent internal carotid artery vasospasms with bilateral carotid artery stenting: a case report. J Neuroendovascular Ther. 2017;11(5):246–252. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graham E, Orjuela K, Poisson S, Biller J. Treatment challenges in idiopathic extracranial ICA vasospasm case report and review of the literature. eNeurologicalSci. 2020;22:100304. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2020.100304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yokota H, Mukai H, Hattori S, Yamada K, Anzai Y, Uno T. MR imaging of the superior cervical ganglion and inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve: structures that can mimic pathologic retropharyngeal lymph nodes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(1):170–176. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huisa BN, Roy G. Spontaneous cervical internal carotid artery vasospasm: case report and literature review. Neurol Clin Pract. 2014;4(5):461–464. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takeuchi M, Saito K, Kajimoto K, Nagatsuka K. Successful corticosteroid treatment of refractory spontaneous vasoconstriction of extracranial internal carotid and coronary arteries. Neurologist. 2016;21(4):55–57. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dembo T, Tanahashi N. Recurring extracranial internal carotid artery vasospasm detected by intravascular ultrasound. Intern Med. 2012;51(10):1249–1253. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fujimoto M, Itokawa H, Moriya M, Okamoto N, Tomita Y, Kikuchi N. Treatment of idiopathic cervical internal carotid artery vasospasms with carotid artery stenting: a report of 2 cases. J Neuroendovascular Ther. 2013;7:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim JT, Won SY, Kang K, et al. ACOX3 dysfunction as a potential cause of recurrent spontaneous vasospasm of internal carotid artery. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11(5):1041–1051. doi: 10.1007/s12975-020-00779-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shim DH, Cha JK, Kang MJ, Choi JH, Nah HW. Vasospastic amaurosis fugax diagnosed by cerebral angiography. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(11):e323–e325. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moeller S, Hilz MJ, Blinzler C, et al. Extracranial internal carotid artery vasospasm due to sympathetic dysfunction. Neurology. 2012;78(23):1892–1894. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f7ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soussan M, Nicolas P, Schramm C, et al. Management of large-vessel vasculitis with FDG-PET: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(14):e622. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clemente G, de Souza AW, Leão Filho H, et al. Does [18F]F-FDG-PET/MRI add metabolic information to magnetic resonance image in childhood-onset Takayasu’s arteritis patients? A multicenter case series. Adv Rheumatol. 2022;62(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s42358-022-00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Obusez EC, Hui F, Hajj-Ali RA, et al. High-resolution MRI vessel wall imaging: spatial and temporal patterns of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and central nervous system vasculitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35(8):1527–1532. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mossa-Basha M, Hwang WD, De Havenon A, et al. Multicontrast high-resolution vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging and its value in differentiating intracranial vasculopathic processes. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1567–1573. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alexander MD, Yuan C, Rutman A, et al. High-resolution intracranial vessel wall imaging: imaging beyond the lumen. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(6):589–597. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitsuoka K, Kikutani T, Sato I. Morphological relationship between the superior cervical ganglion and cervical nerves in Japanese cadaver donors. Brain Behav. 2016;7(2):e00619. doi: 10.1002/brb3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruskell GL. Access of autonomic nerves through the optic canal, and their orbital distribution in man. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;275(1):973–978. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]