Abstract

Background

The effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and advanced kidney disease (AKD) has not been fully established.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety related to pooled or specific DOACs to that with warfarin in patients with AF and AKD.

Methods

Patients with AF and AKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min) who received DOAC or warfarin from July 2011 to December 2020 were retrospectively identified in a medical center in Taiwan. Primary outcomes were hospitalized for stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding. Secondary outcomes included any ischemia and any bleeding.

Results

A total of 1,011 patients were recruited, of whom 809 (80.0%) were in the DOACs group (15.3% dabigatran, 25.4% rivaroxaban, 25.2% apixaban, and 14.1% edoxaban), and 202 (20.0%) in the warfarin group. DOACs had considerably lower risks of stroke/systemic embolism (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.29; 95% CI, 0.09–0.97) and any ischemia (aHR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22–0.79), but had comparable risks of major bleeding (aHR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.34–2.92) and any bleeding (aHR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.50–1.09) than warfarin. Apixaban was linked to considerably lower risks of any ischemia (aHR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04–0.48) and any bleeding (aHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.28–0.99) than warfarin.

Conclusion

Among patients with AF and AKD, DOACs were linked to a lower risk of ischemic events, and apixaban was linked to a lower risk of any ischemia and any bleeding than warfarin.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11239-023-02859-x.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation (AF), Chronic kidney disease (CKD), Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), Warfarin, Thrombosis, Hemorrhage

Highlights

The effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced kidney disease has not been fully established.

DOACs were linked to lower risks of ischemic events compared with warfarin in patients with AF and AKD.

Apixaban was linked to a lower risk of any ischemia and any bleeding than warfarin in patients with AF and AKD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11239-023-02859-x.

Introduction

The global health incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) is rising rapidly, and AF is highly prevalent in CKD patients (13–27%) and those on long-term dialysis (18%) [1–3]. Moreover, the presence of CKD is linked with an additional risk of thromboembolism and bleeding in patients with AF, and vice versa [4]. As a result, it is crucial to pursue the most adequate oral anticoagulant (OAC) to strike the balance between preventing ischemic stroke and mitigating bleeding events in AF patients with CKD.

Warfarin has been the mainstay of treatment in patients with AF and renal impairment for decades. However, warfarin has several limitations, including a narrow therapeutic window for safety, constant monitoring requirements, numerous diet, and drug-drug interactions [5]. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are relatively new agents, including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, which have been demonstrated to be superior or not inferior to warfarin in AF for efficiency and safety [6–10]. Furthermore, DOACs have fixed dosing regimens, which enhance the compliance and persistence with oral anticoagulant therapy. As a result, with the availability of DOACs, the prescription volumes of warfarin have decreased globally [11–15].

However, few randomized controlled trials of oral anticoagulants comprised patients with advanced kidney disease (AKD), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min. Although several regulatory agencies have authorized DOACs (except dabigatran) for patients with an eGFR above 15 mL/min on the basis of pharmacokinetic data, and a meta-analysis has validated the efficacy and safety of DOACs in this population, [16] the evidence of efficacy and safety between DOACs and warfarin remains low, particularly in comparisons between different DOACs. The disparities in efficacy and safety among DOACs in patients with AKD patients may be influenced by differences in their pharmacokinetic profiles. Existing studies mostly contrasted single DOAC (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban) [17–19] or pooled DOACs [20, 21] with warfarin, with less data on edoxaban or simultaneous comparison of the four DOACs individually with warfarin in AF patients with AKD. Therefore, this retrospective cohort study sought to assess the outcomes linked to pooled or specific DOACs compared with warfarin in patients with AF patients with AKD.

Methods

Data source & study design

We undertook a retrospective cohort study at Taipei Veterans General Hospital (TPEVGH), one of the largest medical centers in Taiwan, which allows more than 2.5 million outpatient visits for 1.1 million patients each year. This study was partially based on data from the Big Data Center, TPEVGH, and was authorized by the Institutional Review Board of TPEVGH (IRB-TPEVGH NO.: 2021-09-020BC). Informed consent was swayed due to the use of deidentified data and retrospective design.

Outpatients aged over 20 years and prescribed any oral anticoagulation between July 1, 2011, and December 31, 2020, were recruited. The cohort entry date was described as the date of initiation of treatment, and the date of OAC prescription plus eGFR < 30 mL/min constituted the index date. CrCl was measured according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula [22]. We exempted patients with (1) no visits or only one visit with a diagnosis of AF within 1 year before the OAC prescription; (2) eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min throughout the study period or unknown; (3) proof of anticoagulant prescription, knee/hip replacement surgery or venous thromboembolic events within 6 months before the cohort entry date (i.e., washout period); (4) history of valve surgery, mitral stenosis, or kidney transplant (see Table S1–S4 for codes).

Follow-up initiated the day after index date until the discovery of the outcomes, diversifying to other study drugs, discontinuation of anticoagulation prescription or > 30-day gap between new prescriptions, unknown/recovery of renal function (eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min) for over 6 months, withdrawal from valve surgery, kidney transplantation, or mitral stenosis, death, or study end (December 31, 2020), whichever came first (see Figure S1 for details).

Ascertainment of exposure and outcome

All qualified participants were categorized into two groups: DOACs and the warfarin group. Warfarin was employed as an active comparator to enhance the study’s validity by mitigating measured and unmeasured differences between the study groups [23].

We analyzed hospitalization events using inpatient claims in the primary or secondary diagnosis position or relevant procedure codes (see Table S5–S7 for codes). First, two primary outcomes were admissions due to stroke/systemic embolism (stroke/SE) and major bleeding. Major bleeding was identified as hemorrhagic events that led to hospitalization. Second, the secondary effectiveness outcome was any ischemia, a composite of stroke/SE, venous thromboembolism, acute myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral vascular disease. Finally, the secondary safety outcome was any bleeding, characterized as all bleeding events in inpatient and outpatient claims, whichever occurred first.

Ascertainment of baseline covariates

We determined potential baseline confounders within one year before the index date. The covariates included demographic data, other medical comorbidities, and concomitant medications (see Table 1 for the list of covariates and Table S8–S12 for codes).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population before and after inverse probability of treatment weighting

| Before Weighting | After Weighting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | DOACs (N = 809) |

Warfarin (N = 202) |

Absolute standardized difference |

DOACs (N = 503) |

Warfarin (N = 508) |

Absolute standardized difference |

||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 84.1 (7.4) | 78.2 (10.3) | 0.66 | 83.1 (6.6) | 82.5 (12.6) | 0.06 | ||

| Female sex, No. (%) | 345 (42.7) | 85 (42.1) | 0.01 | 215 (42.7) | 221 (43.6) | 0.02 | ||

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 58.0 (11.1) | 60.7 (12.1) | 0.23 | 58.5 (8.8) | 58.7 (17.5) | 0.02 | ||

| eGFR, No. (%) | 0.82 | 0.02 | ||||||

| 15–29 mL/min | 779 (96.3) | 135 (66.8) | 459 (91.3) | 460 (90.7) | ||||

| < 15 mL/min, including dialysisa | 30 (3.7) | 67 (33.2) | 44 (8.7) | 48 (9.4) | ||||

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | ||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.7) | 0.04 | 4.5 (1.1) | 4.6 (2.3) | 0.02 | ||

| HAS-BLED score, mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.3) | 0.25 | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.8) | 0.02 | ||

| Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.1) | 0.14 | 2.8 (1.8) | 2.8 (3.5) | 0.01 | ||

| Anemia | 108 (13.4) | 36 (17.8) | 0.12 | 70 (13.9) | 58 (11.5) | 0.07 | ||

| Asthma | 53 (6.6) | 11 (5.5) | 0.05 | 32 (6.3) | 27 (5.4) | 0.04 | ||

| Cancers | 161 (19.9) | 29 (14.4) | 0.15 | 95 (19.0) | 100 (19.8) | 0.02 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 270 (33.4) | 64 (31.7) | 0.04 | 165 (32.8) | 182 (35.8) | 0.06 | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 394 (48.7) | 95 (47.0) | 0.03 | 245 (48.8) | 246 (48.6) | 0.00 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 33 (4.1) | 20 (9.9) | 0.23 | 23 (4.7) | 25 (5.0) | 0.01 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 34 (4.2) | 17 (8.4) | 0.17 | 24 (4.9) | 19 (3.7) | 0.05 | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder | 148 (18.3) | 36 (17.8) | 0.01 | 98 (19.5) | 80 (15.8) | 0.10 | ||

| Diabetes | 273 (33.8) | 87 (43.1) | 0.19 | 182 (36.2) | 200 (39.4) | 0.07 | ||

| Gastrointestinal ulcer | 134 (16.6) | 34 (16.8) | 0.01 | 85 (17.0) | 66 (13.0) | 0.11 | ||

| Hypertension | 629 (77.8) | 162 (80.2) | 0.06 | 396 (78.7) | 410 (80.8) | 0.05 | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 215 (26.6) | 69 (34.2) | 0.17 | 144 (28.6) | 152 (30.0) | 0.03 | ||

| Liver disease | 65 (8.0) | 22 (10.9) | 0.10 | 42 (8.3) | 45 (8.9) | 0.02 | ||

| Prior bleedingb | 203 (25.1) | 44 (21.8) | 0.08 | 122 (24.3) | 112 (22.1) | 0.05 | ||

| Smoking | 0.13 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Current non-smoker | 756 (93.4) | 191 (94.5) | 474 (94.1) | 484 (95.4) | ||||

| Current smoker | 19 (2.4) | 7 (3.5) | 11 (2.2) | 9 (1.8) | ||||

| Unknown | 34 (4.2) | 4 (2.0) | 18 (3.7) | 15 (2.8) | ||||

| Thyroid Disease | 64 (7.9) | 18 (8.9) | 0.04 | 43 (8.5) | 52 (10.3) | 0.06 | ||

| Venous thromboembolism | 16 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.04 | 10 (2.1) | 18 (3.5) | 0.09 | ||

| Medication use, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Antianxiety agents | 220 (27.2) | 65 (32.2) | 0.11 | 143 (28.3) | 131 (25.7) | 0.06 | ||

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 220 (27.2) | 65 (32.2) | 0.11 | 140 (27.8) | 142 (28.1) | 0.01 | ||

| Anti-depressants | 92 (11.4) | 21 (10.4) | 0.03 | 60 (12.0) | 68 (13.4) | 0.04 | ||

| Antiplatelets | 290 (35.9) | 88 (43.6) | 0.16 | 185 (36.8) | 184 (36.3) | 0.01 | ||

| Anti-hyperlipidemics | 252 (31.2) | 78 (38.6) | 0.16 | 171 (33.9) | 195 (38.5) | 0.09 | ||

| ACEi / ARB | 464 (57.4) | 133 (65.8) | 0.18 | 297 (59.1) | 305 (60.0) | 0.02 | ||

| β-Blockers | 442 (54.6) | 116 (57.4) | 0.06 | 276 (54.8) | 284 (56.0) | 0.02 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 546 (67.5) | 142 (70.3) | 0.06 | 336 (66.8) | 351 (69.2) | 0.05 | ||

| Diuretics | 512 (63.3) | 132 (65.4) | 0.04 | 326 (64.7) | 352 (69.3) | 0.10 | ||

| Other anti-hypertensives | 104 (12.9) | 45 (22.3) | 0.25 | 67 (13.3) | 61 (12.0) | 0.04 | ||

| Insulins | 79 (9.8) | 39 (19.3) | 0.27 | 57 (11.4) | 60 (11.8) | 0.01 | ||

| Antidiabetics | 200 (24.7) | 64 (31.7) | 0.16 | 132 (26.3) | 157 (30.9) | 0.10 | ||

| NSAIDs | 198 (24.5) | 40 (19.8) | 0.11 | 122 (24.3) | 133 (26.2) | 0.04 | ||

| Proton pump inhibitors | 140 (17.3) | 48 (23.8) | 0.16 | 93 (18.4) | 99 (19.4) | 0.03 | ||

Abbreviations: ACEIs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-Inflammatory drugs

a Three (0.6%) patients in the DOACs group and 13 (2.6%) patients in the warfarin group received hemodialysis

b Prior bleeding included gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and other major bleeding, e.g., hematuria, epistaxis, and hemoptysiss

Statistical analysis

We report the trends in oral anticoagulation prescriptions in the research population. For analysis, we applied the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) technique to balance the differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups. All covariates were applied in a multivariate logistic regression model to forecast the probability of receiving DOACs versus warfarin. We weighted the patients by the inverse of this probability and stabilized the weights by multiplying by the number of patients in the treatment groups [24].

We utilized descriptive statistics in the study population before and after adopting IPTW, and the absolute standardized difference (ASD) ≥ 0.1 was interpreted as a potentially significant imbalance [25]. Survival free of an event in the weighted DOAC and warfarin cohorts was expressed with Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank testing. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models weighted with IPTW were employed to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% CIs. Variables that were significant (ASD ≥ 0.1) and clinically relevant confounders (i.e., age, sex, CHA2DS2-VASc/HAS-BLED score, smoking status, prior bleeding, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, antiplatelets, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) were included in the multivariate model. For the sub-analysis, we segmented the DOACs group in the main analysis into four cohorts: the dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban cohorts, and compared with warfarin, respectively.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

A series of sensitivity analysis was conducted to validate the results. Specifically, we (1) excluded unreasonable doses of DOACs; (2) only included warfarin users with time in the therapeutic range (TTR) ≥ 70% of their international normalized ratio (INR) readings between 1.5 and 3.0;[26–29]. (3) utilized the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation to calculate GFR;[30]. (4) restricted the follow-up period to only 1 year; (5) removed patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min only once.

Furthermore, subgroup analysis was conducted to address the potential prevalent user bias. To maximize our sample size, we included the prevalent users in this research. Thus, new users were regarded as the initiation of treatment at eGFR < 30 mL/min, whereas prevalent users started treatment at eGFR ≧ 30 mL/min. We performed a subgroup analysis to reveal whether the connection between these groups was coherent. We employed Cochran’s Q heterogeneity statistic in the sensitivity and subgroup analysis to detect interactions.

All data management and analysis were carried out using Statistical Analysis System, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R Statistical Software version 4.1.3 (Foundation for Statistical Computing). Two-sided P < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

We recruited 1,011 patients with AF and eGFR less than 30 mL/min. Among them, 809 (80.0%) were in the DOACs group, with 19.2% (n = 155) prescribed dabigatran, 31.8% (n = 257) prescribed rivaroxaban, 31.5% (n = 255) prescribed apixaban, 17.6% (n = 142) prescribed edoxaban (see Table S13 for details). The remaining 202 patients (20.0%) were in the warfarin group, with a mean TTR of 39.5% (see Table S14 for TTR details). The flow chart for the enrollment of the study population is depicted in Figure S2.

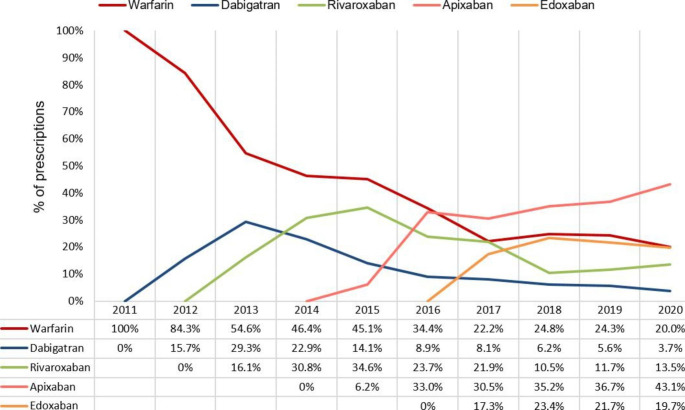

Trends of OAC prescription

The trends in OAC prescription in the study population are depicted in Fig. 1. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban were previously prescribed in 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2017, respectively. After the development of DOACs, the percentage of warfarin decreased markedly over the period (100% in 2011 and 20% in 2020). Similarly, a downward tendency can be observed in dabigatran and rivaroxaban, after a rapid elevation to a peak of 29.3% in 2013 and 34.6% in 2015, respectively. In contrast, the percentage of apixaban gradually increased and apixaban use (30.5%) exceeded warfarin use (22.5%) in 2017. By 2020, apixaban use was still prevalent (43.1%). The percentage of edoxaban was constant at around 20% between 2017 and 2020.

Fig. 1.

Changes in oral anticoagulant prescriptions among patients with advanced kidney disease and atrial fibrillation (AF) throughout the research (2011–2020)

Baseline patient characteristics

Prior to implementing IPTW, DOACs users were older (84.1 versus 78.2 years), had lower body weight (58.0 versus 60.7 kg), a lower proportion of patients with eGFR < 15 mL/min (3.7 versus 33.2%), a lower HAS-BLED score (3.3 versus 3.6), and a lower Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (2.7 versus 3.0) compared to warfarin users. The mean scores for CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED were 4.5 ± 1.4, 4.5 ± 1.7 and 3.3 ± 1.3, 3.6 ± 1.3, respectively, validating that these patients tend to thrombosis and hemorrhage. IPTW successfully achieved balance in all baseline characteristics, except for COPD, GI ulcer, use of diuretics, and use of antidiabetics.

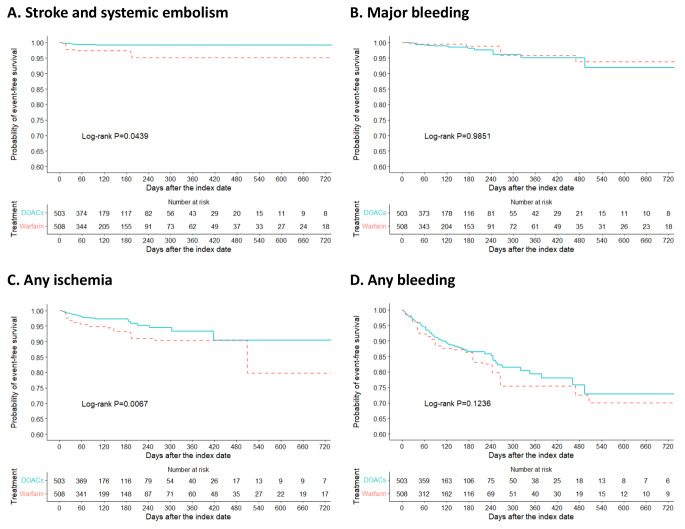

Clinical outcomes

The incidence rates and aHRs of outcomes are expressed in Table 2, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves of outcomes after integrating IPTW are depicted in Fig. 2 (see Table S15 and Figure S3 for unweighted results). The incidence rate of stroke/SE was 2.25 and 6.54 per 100 patient-years for the DOACs and warfarin groups with a considerably lower risk of stroke/SE between the groups (log-rank P = 0.0439). In multivariate Cox regression analysis after IPTW, the aHR for DOACs versus warfarin was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.09–0.97; P = 0.0439) for stroke/SE. No substantial difference between the two groups was found for major bleeding (4.33 and 2.74 per 100 patient-years for DOACs and warfarin, respectively) with a non-significant association estimate (aHR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.34–2.92; P = 0.9851). Furthermore, DOACs were linked to a significantly lower risk of any ischemia (aHR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22–0.79; P = 0.0067). Finally, there was a non-significant trend toward less bleeding in the DOACs group (aHR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.50–1.09; P = 0.1236). The reasons for the censorship are presented in Table S16.

Table 2.

Incidence rates and hazard ratios of outcomes after inverse probability of treatment weighting

| Outcome | DOACs group (n = 503) | Warfarin group (n = 508) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | PY | Rate (95%CI)a | Events | PY | Rate (95%CI)a | |||

| Stroke/SE | 5 | 208 | 2.25 (0.91–5.56) | 17 | 259 | 6.54 (4.06–10.53) | 0.29 (0.09–0.97) | |

| Major bleeding | 9 | 208 | 4.33 (2.25–8.33) | 7 | 257 | 2.74 (1.31–5.74) | 0.99 (0.34–2.92) | |

| Any ischemia | 17 | 202 | 8.27 (5.12–13.34) | 35 | 248 | 14.18 (10.18–19.74) | 0.42 (0.22–0.79) | |

| Any bleeding | 55 | 194 | 28.38 (21.80-36.95) | 65 | 202 | 32.31 (25.33–41.20) | 0.74 (0.50–1.09) | |

a Incidence rate, per 100 person-years

b Weighted with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) and adjusted for age, sex, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal ulcer, diuretics, antidiabetics, CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, smoking status, prior bleeding, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, antiplatelets, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Abbreviations: DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; PY person-years; SE systemic embolism

Fig. 2.

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) Kaplan-Meier survival curves in patients with advanced kidney disease and atrial fibrillation (AF). (A) Stroke/systemic embolism. (B) Major bleeding. (C) Any ischemia. (D) Any bleeding. DOACs indicates direct oral anticoagulants

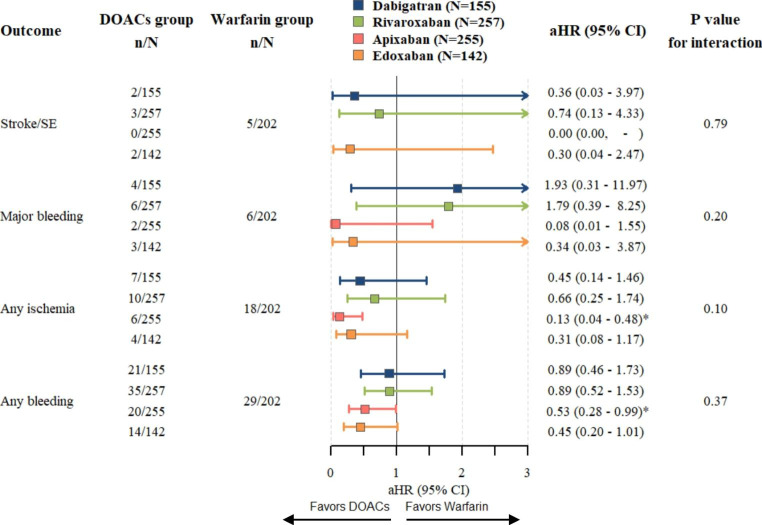

DOAC-specific analyses

The sub-analysis (Fig. 3) demonstrated that each specific DOAC may be linked to lower risks in stroke/SE, any ischemia, and any bleeding. Each DOAC (except apixaban, as no event was observed and HR could not be calculated) indicated a comparable but not significant trend in stroke/SE. The risks of major bleeding were inconsistent with each DOAC. While dabigatran (aHR, 1.93; 95% CI, 0.31–11.97; P = 0.4806) and rivaroxaban (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 0.39–8.25; P = 0.4546) may be linked to a higher risk of major bleeding, apixaban (aHR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01–1.55; P = 0.0942) and edoxaban (aHR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.03–3.87; P = 0.3818) may lower the risks of major bleeding, compared with warfarin. Apixaban was related to a significant reduction in the risk of any ischemia (aHR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04–0.48; P = 0.0021) and any bleeding (aHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.28–0.99; P = 0.0470) than warfarin. Edoxaban also exhibited a comparable but not significant trend (aHR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.08–1.17; P = 0.0831 in any ischemia; aHR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.20–1.01 in any bleeding).

Fig. 3.

DOAC-specific sub-analysis compared with warfarin and P value for interaction. Hazard ratios and 95% CIs are derived from Cox regression analyses weighted with IPTW and adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, and comedications. DOACs indicates direct oral anticoagulants; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; n, number in group with the outcome; and N, total number in group

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

We did not discover any significance in the sensitivity and subgroup analysis (see Table S17 and Fig. 4 for details), except for any bleeding in the sensitivity analysis of only including warfarin users with TTR ≥ 70% (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.69–5.19; P for interaction = 0.09).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, we discovered that the use of DOACs elevated with a corresponding decline in warfarin in patients with AF and AKD. DOACs substantially decreased the risk of stroke/SE and any ischemia in patients with AF and AKD compared with warfarin. In the sub-analysis of each DOAC, apixaban was linked to a significant reduction in the risk of any ischemia and any bleeding compared with warfarin.

Trends of OAC prescription

In the current study, we observed that the percentage of DOAC use in patients with AF and AKD has consistently increased in the last decade, with a corresponding decline in warfarin. A similar trend was found in the other studies of AF patients with chronic renal disease [12, 31–34]. We discovered that rivaroxaban and apixaban were the two most prevalently prescribed DOACs, which is coherent with prior studies in AF patients [35, 36]. The increasing use of DOACs highlights the importance of their use in AKD populations to assess efficacy and safety, necessitating the need for additional evidence.

Clinical outcomes

Based on our findings, DOACs seem to be more efficient than warfarin in preventing ischemic stroke/systemic embolism and any ischemia events among patients with AF patients with AKD. A multicentre retrospective cohort study, also undertaken in Taiwan, revealed similar results [20]. A systematic review and meta-analysismerging data from various observational studies of this population discovered similar outcomes. [16].

In the present study, we observed a significant disparity in the distribution of individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD, eGFR < 15 mL/min with or without dialysis) between DOACs and warfarin (DOACs 3.7% versus warfarin 33.2%). This finding aligns with the results reported by Betra et al., indicating that warfarin remains the preferred OAC choice for patients with ESRD [31]. Previous meta-analyses comparing DOACs with warfarin in the ESRD population, primarily focusing on dialysis patients, have yielded inconsistent outcomes. See et al. reported no significant difference in effectiveness and safety outcomes between DOACs and warfarin in AF patients on dialysis [37]. In contrast, Elfar et al. demonstrated that DOACs were associated with higher rates of systemic embolization, minor bleeding, and death compared to warfarin [38]. Conversely, Li et al. found that DOACs were associated with a reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding [39]. Furthermore, none of the studies have specifically examined ESRD patients without dialysis. Therefore, further studies are needed to validate OAC selection for the AF patients with ESRD.

A previous study demonstrated a progressive increase in the incidence of net adverse clinical events (including death, ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding) as renal function deteriorated [40]. The benefit of anticoagulation therapy varies among patients with different stages of CKD. In our study, the primary population consisted of individuals in CKD stage 4, and the findings may not be generalizable to stage 5. Furthermore, the disparities in the percentage of each DOAC item between studies have restricted the interpretation and applicability of these results. Therefore, direct head-to-head comparisons using individual-level data are required to fully determine the comparative effects of DOACs.

DOAC-specific analyses

In the DOAC-specific analyses, we observed that apixaban was the only DOAC that markedly reduced the risks of any ischemia and bleeding compared with warfarin. Prior studies have also supplemented the application of apixaban in AKD patients to mitigate the risk of major bleeding and have the potential to lower the risk of ischemic events [18, 33, 41]. The varying proportion of renal elimination could partially explain the irregularity in embolic and bleeding outcomes among DOACs. Apixaban is less dependent on renal elimination than the other DOACs, [42] and is the only DOAC authorized for application in hemodialysis based on pharmacokinetic data [43].

The available evidence on the use of edoxaban in patients with advanced kidney disease is limited. A 12-week phase 3 study conducted in Japanese AF patients with an eGFR of 15–29 mL/min showed that a once-daily dose of 15 mg of edoxaban had a safety and pharmacokinetic profile similar to the 30 and 60 mg doses in patients with normal renal function [44]. Additionally, a small retrospective study reported that the use of edoxaban in AF patients with an eGFR of 15–29 mL/min were not observed major bleeding or thrombotic events [45]. Our findings indicate that edoxaban may be linked to a decreased risk of embolic and bleeding events. Although our results did not reach statistical significance, there is a trend suggesting a lower risk of both embolic and bleeding events compared to warfarin.

These findings from DOAC-specific analyses support the hypothesis that the bleeding and ischemic risks associated with DOACs may differ in patients with advanced kidney disease, highlighting the potential for personalized drug selection in real-world scenarios.

Study strengths and limitations

The current study has multiple main strengths. First, we applied comprehensive laboratory data (e.g., serum creatinine, weight, height, etc.) instead of diagnostic codes to specifically capture our study population. Second, we highlighted the effectiveness and safety of the four DOACs separately in this special population. Finally, we examined the effect of different scenarios in the sensitivity analyses and dealt with the prevalent user bias properly in the subgroup analysis to evaluate our study outcomes.

Despite these strengths, this research has the following limitations. First, as the retrospective observational study design, we could not access all residual confounders (e.g., drug adherence), although we controlled for age, sex, comorbidities, medications, CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, and smoking status in Cox regression models. Second, since our data are obtained from a single center, we may unavoidably underestimate dialysis recipients and lethal outcomes, and also have lower external validity to other ethnic groups. Third, the primary population consisted of individuals in CKD stage 4, and the findings may not be generalizable to stage 5. Finally, given the limitations in sample size, there may have been insufficient statistical power to compare certain individual direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) with warfarin. However, these findings have the potential to support the feasibility of personalized drug selection in real-world settings.

In conclusion, the application of DOACs was linked to lower risks of ischemic events compared with warfarin in patients with AF and AKD. Among DOACs, apixaban was connected to a substantial reduction in the risk of any ischemia and any bleeding compared with warfarin.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shang-Liang Wu from Biostatistics Task Force, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, for statistical assistance.

Author contributions

CC Hsu and CC Chen contributed equally. CC Hsu, CC Chen, CY Chou, and YL Chang formulated the study concept and design. CC Hsu and CC Chen performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion; reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript; and agreed to submission.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and publication of this article. This study was funded by a research grant from National Science and Technology Council (MOST111-2635-B-075-001) and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V111B-043, V111EA-017, V111C-234, V112C-229) in Taiwan. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, result interpretation, publication decision, or manuscript preparation.

Declarations

of Conflicting Interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Diseases GBD, Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Go AS, Xie D, Lash JP, Rahman M, Ojo A, Teal VL, Jensvold NG, Robinson NL, Dries DL, Bazzano L, Mohler ER, Wright JT, Feldman HI, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study G Chronic kidney disease and prevalent atrial fibrillation: the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) Am Heart J. 2010;159:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinecke H, Brand E, Mesters R, Schabitz WR, Fisher M, Pavenstadt H, Breithardt G. Dilemmas in the management of atrial fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:705–711. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, Hommel K, Kober L, Lane DA, Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:625–635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutescu EA, Burnett A, Fanikos J, Spinler S, Wittkowsky A. Erratum to: pharmacology of anticoagulants used in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42:296–311. doi: 10.1007/s11239-016-1363-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Spinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM, Investigators EA-T. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, Camm AJ, Weitz JI, Lewis BS, Parkhomenko A. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joy M, Williams J, Emanuel S, Kar D, Fan X, Delanerolle G, Field BC, Heiss C, Pollock KG, Sandler B, Arora J, Sheppard JP, Feher M, Hobbs FR, de Lusignan S. Trends in direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) prescribing in English primary care (2014–2019) Heart. 2023;109:195–201. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-321377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campitelli MA, Bronskill SE, Huang A, Maclagan LC, Atzema CL, Hogan DB, Lapane KL, Harris DA, Maxwell CJ. Trends in Anticoagulant use at nursing home admission and variation by Frailty and chronic kidney Disease among older adults with Atrial Fibrillation. Drugs Aging. 2021;38:611–623. doi: 10.1007/s40266-021-00859-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weitz JI, Semchuk W, Turpie AG, Fisher WD, Kong C, Ciaccia A, Cairns JA (2015) Trends in Prescribing Oral Anticoagulants in Canada, 2008–2014. Clin Ther. ; 37: 2506-14 e4. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Alalwan AA, Voils SA, Hartzema AG. Trends in utilization of warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants in older adult patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J health-system pharmacy: AJHP : official J Am Soc Health-System Pharmacists. 2017;74:1237–1244. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjerpeseth LJ, Ellekjaer H, Selmer R, Ariansen I, Furu K, Skovlund E. Trends in use of warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation in Norway, 2010 to 2015. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:1417–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee TM, Lee SR, Choi EK, Oh S, Lip GYH. Efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulants for Atrial Fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:885548. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.885548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman CI, Kreutz R, Sood NA, Bunz TJ, Eriksson D, Meinecke AK, Baker WL. Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and severe kidney disease or undergoing hemodialysis. Am J Med. 2019;132:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanifer JW, Pokorney SD, Chertow GM, Hohnloser SH, Wojdyla DM, Garonzik S, Byon W, Hijazi Z, Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Wallentin L, Granger CB. Apixaban Versus Warfarin in patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Advanced chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1384–1392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weir MR, Ashton V, Moore KT, Shrivastava S, Peterson ED, Ammann EM. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and stage IV-V chronic kidney disease. Am Heart J. 2020;223:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang SH, Wu CV, Yeh YH, Kuo CF, Chen YL, Wen MS, See LC, Huang YT. Efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulants in patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Stages 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:1335–43e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makani A, Saba S, Jain SK, Bhonsale A, Sharbaugh MS, Thoma F, Wang Y, Marroquin OC, Lee JS, Estes NAM, Mulukutla SR. Safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in patients with chronic kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida K, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Active-comparator design and new-user design in observational studies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:437–441. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, Shetterly S, Blanchette C, Smith D. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health. 2010;13:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krittayaphong R, Kunjara-Na-Ayudhya R, Ngamjanyaporn P, Boonyaratavej S, Komoltri C, Yindeengam A, Sritara P, Lip GYH. For the Cool-Af I. Optimal INR level in elderly and non-elderly patients with atrial fibrillation receiving warfarin: a report from the COOL-AF nationwide registry in Thailand. J Geriatric Cardiol. 2020;17:612–620. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T, Hui J, Hou YY, Zou Y, Jiang WP, Yang XJ, Wang XH. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of low-intensity warfarin therapy for east asian patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL, Group ESCSD. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lip GYH, Banerjee A, Boriani G, Chiang CE, Fargo R, Freedman B, Lane DA, Ruff CT, Turakhia M, Werring D, Patel S, Moores L. Antithrombotic therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154:1121–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batra G, Modica A, Renlund H, Larsson A, Christersson C, Held C (2022) Oral anticoagulants, time in therapeutic range and renal function over time in real-life patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. Open Heart 9. 10.1136/openhrt-2022-002043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Chan KE, Edelman ER, Wenger JB, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Dabigatran and rivaroxaban use in atrial fibrillation patients on hemodialysis. Circulation. 2015;131:972–979. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, Bhave N, Schaubel DE, He K, Tilea A, Stack AG, Balkrishnan R, Yao X, Noseworthy PA, Shah ND, Saran R, Nallamothu BK. Outcomes Associated with Apixaban Use in patients with end-stage kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation in the United States. Circulation. 2018;138:1519–1529. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wetmore JB, Roetker NS, Yan H, Reyes JL, Herzog CA. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in Medicare patients with chronic kidney Disease and Atrial Fibrillation. Stroke. 2020;51:2364–2373. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.028934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afzal S, Zaidi STR, Merchant HA, Babar ZU, Hasan SS. Prescribing trends of oral anticoagulants in England over the last decade: a focus on new and old drugs and adverse events reporting. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;52:646–653. doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02416-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau WCY, Torre CO, Man KKC, Stewart HM, Seager S, Van Zandt M, Reich C, Li J, Brewster J, Lip GYH, Hingorani AD, Wei L, Wong ICK. Comparative effectiveness and safety between Apixaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban, and Rivaroxaban among patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a multinational Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1515–1524. doi: 10.7326/M22-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.See LC, Lee HF, Chao TF, Li PR, Liu JR, Wu LS, Chang SH, Yeh YH, Kuo CT, Chan YH, Lip GYH. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in an Asian Population with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Dialysis: a Population-Based Cohort Study and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2021;35:975–986. doi: 10.1007/s10557-020-07108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elfar S, Elzeiny SM, Ismail H, Makkeyah Y, Ibrahim M. Direct oral anticoagulants vs. Warfarin in Hemodialysis patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:847286. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.847286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Zhou Y, Chen S, Zeng D, Zhang H. Use of non-vitamin K antagonists oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients on dialysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1005742. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1005742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho MS, Choi HO, Hwang KW, Kim J, Nam GB, Choi KJ. Clinical benefits and risks of anticoagulation therapy according to the degree of chronic kidney disease in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23:209. doi: 10.1186/s12872-023-03236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan YH, Lee HF, See LC, Tu HT, Chao TF, Yeh YH, Wu LS, Kuo CT, Chang SH, Lip GYH. Effectiveness and safety of four direct oral anticoagulants in asian patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2019;156:529–543. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.04.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ingrasciotta Y, Crisafulli S, Pizzimenti V, Marcianò I, Mancuso A, Andò G, Corrao S, Capranzano P, Trifirò G. Pharmacokinetics of new oral anticoagulants: implications for use in routine care. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14:1057–1069. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2018.1530213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Tirucherai G, Marbury TC, Wang J, Chang M, Zhang D, Song Y, Pursley J, Boyd RA, Frost C. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of apixaban in subjects with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56:628–636. doi: 10.1002/jcph.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koretsune Y, Yamashita T, Kimura T, Fukuzawa M, Abe K, Yasaka M. Short-term safety and plasma concentrations of Edoxaban in japanese patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and severe renal impairment. Circ J. 2015;79:1486–1495. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fazio G, Dentamaro I, Gambacurta R, Alcamo P, Colonna P. Safety of Edoxaban 30 mg in Elderly patients with severe renal impairment. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:1023–1030. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.