Abstract

Purpose

Noninvasive cell-type-specific manipulation of neural signaling is critical in basic neuroscience research and in developing therapies for neurological disorders. Magnetic nanotechnologies have emerged as non-invasive neuromodulation approaches with high spatiotemporal control. We recently developed a wireless force-induced neurostimulation platform utilizing micro-sized magnetic discs (MDs) and low-intensity alternating magnetic fields (AMFs). When targeted to the cell membrane, MDs AMFs-triggered mechanoactuation enhances specific cell membrane receptors resulting in cell depolarization. Although promising, it is critical to understand the role of mechanical forces in magnetomechanical neuromodulation and their transduction to molecular signals for its optimization and future translation.

Methods

MDs are fabricated using top-down lithography techniques, functionalized with polymers and antibodies, and characterized for their physical properties. Primary cortical neurons co-cultured with MDs and transmembrane protein chemical inhibitors are subjected to 20 s pulses of weak AMFs (18 mT, 6 Hz). Calcium cell activity is recorded during AMFs stimulation.

Results

Neuronal activity in primary rat cortical neurons is evoked by the AMFs-triggered actuation of targeted MDs. Ion channel chemical inhibition suggests that magnetomechanical neuromodulation results from MDs actuation on Piezo1 and TRPC1 mechanosensitive ion channels. The actuation mechanisms depend on MDs size, with cell membrane stretch and stress caused by the MDs torque being the most dominant.

Conclusions

Magnetomechanical neuromodulation represents a tremendous potential since it fulfills the requirements of negligible heating (ΔT < 0.1 °C) and weak AMFs (< 100 Hz), which are limiting factors in the development of therapies and the design of clinical equipment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12195-023-00786-8.

Keywords: Magnetic nanomaterials, Control of biological signaling, Alternating magnetic fields, Nanomagnetic actuation

Introduction

Noninvasive cell-type-specific manipulation of neural signaling is critical in basic neuroscience research and in developing therapies for neurological disorders and psychiatric conditions. Despite three decades of research, the spatial extent and cell-type specificity of neuromodulation through noninvasive drug-free technologies such as transcranial repetitive magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) remains elusive [1, 58, 73]. Both rTMS and tDCS are implemented in clinical settings for brain stimulation to treat various neurological disorders using frequencies between 10 and 20 Hz for rTMS [4, 13, 17, 27, 31, 45, 63, 68, 79], and currents ranging from 1 to 2 mA for tDCS [15, 33, 46]. Noninvasive neuromodulation through transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) has emerged as a promising approach with higher spatial resolution than rTMS and tDCS, allowing the stimulation of deep brain structures [87]. Still, the tFUS radius of action is ample (millimeters to centimeters [28, 44]) in comparison with neural circuits (microns [23, 67, 88]) which results in undesired cell stimulation and ablation of brain healthy tissues.

To achieve noninvasive neuromodulation with higher spatial control, magnetic, electric, or focused ultrasound stimulation can be coupled with nanotransducers. For instance, nanotransducers such as magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) [7, 37] and plasmonic nanostructures [5, 86] can convert external magnetic and light stimuli, respectively, into heat. Localized heat dissipation of these nanotransducers has been studied for the wireless control of neural signaling. The weak magnetic properties and low electrical conductivity of tissues allow alternating magnetic fields (AMFs) to reach deep into the body [21, 35, 75], making hysteresis heating of MNPs particularly promising for applications that could involve stimulation of deep brain structures. Both, bulk and nanoscale heating of MNPs have been reported to evoke activity in neurons [7, 37]. Still, this magnetothermal transduction approach is limited for heat-sensitive neurons or requires transgenes to sensitize neurons to heat. Moreover, potential off-target heating effects and challenges in scaling high-frequency (104–106 Hz) AMFs coils impede the universal adoption of magnetic hyperthermia technologies in biomedical research and clinical practices.

Nanoparticle-assisted mechanotransduction has also been suggested for controlling biological signaling. For instance, in sono-optogenetics (a wireless version of optogenetics), zinc sulfite-based nanoparticles are utilized to transduce mechanical forces from ultrasound into optical energy. [65, 83]. The localized light produced by these nanotransducers is utilized to trigger the response of neurons genetically modified to express light-sensitive transmembrane channels. Transgene-free mechanotransduction approaches are achieved by engineering magnetic nano and microtransducers to produce mechanical forces greater than 0.2 pN (the threshold to trigger biological signaling) [53]. For magnetomechanical torque, magnetic transducers must possess high saturation magnetization and magnetic anisotropy energy dominated by Brownian relaxation over Néel magnetization relaxation. The coercive field of magnetic nanotransducers can be increased by engineering composition (magnetocrystalline anisotropy) and shape (shape anisotropy) [71]. For instance, magnetic nanoactuators fabricated by assembling octahedral iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles are used to transduce rotating static magnetic fields into mechanical torques and precisely stimulate neuronal activity in mechanosensitive neurons with high spatial accuracy and long working distance [43].

Mechanotransduction can be also realized in magnetic nanotransducers with unique spin configurations such as magnetic vortex ground state [20, 56, 57]. Magnetic vortex state (zero net magnetic moments at remanence) is achieved in low aspect-ratio structures like disc-shaped nano or microsized magnetic discs (MDs). When low-frequency low-amplitude AMFs are applied, MDs rotate to align their magnetic moments with the field direction, transducing AMFs into mechanical forces. Mechanotransduction using MDs has been applied to kill cancer cells via the disruption of cell membranes caused by high exerted forces [41]. If the actuation forces are regulated, such as in magnetite MDs, it is possible to utilize the produced forces to control mechano-sensory cells remotely [30]. However, poor batch-to-batch consistency in magnetite MDs chemical synthesis, as well as their low magnetic moments limit their efficiency [6, 30, 84, 85]. Direct writing laser lithography and physical vapor deposition have been reported for the cost-effective mass production of MDs with high magnetic moment [60, 61, 64]. Utilizing these techniques to fabricate 4 μm in diameter Nickel-Iron permalloy (Ni80Fe20) MDs coated with gold (Au) and utilizing low-intensity AMFs, we recently reported a wireless force-induced neurostimulation platform [12]. In addition to eliminating batch-to-batch production variations, Ni80Fe20-Au MDs allowed us to improve mechanotransduction efficiency by 1000× over chemically synthesized magnetite MDs. Magnetomechanical transduction using MDs represents a tremendous potential for transgene-free, noninvasive, cell-type-specific neurostimulation since it fulfills the requirements of low frequency and small magnetic fields, which are limiting factors in the development of therapies and the design of clinical equipment.

Despite its unique capabilities, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of magnetomechanical neuromodulation have not been elucidated. Although magnetic hyperthermia has been discarded in earlier investigations [12, 30], magnetomechanical transduction mediated by MDs could produce different types of mechanical forces. This includes torque, shear stress, and membrane stretch that can be coupled to channel proteins. Understanding the role of each type of mechanical force in magnetomechanical neuromodulation and their transduction to molecular signals in neurons is critical for the optimization and future translation of this promising technology. Here, we describe a comprehensive study of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of magnetomechanical neuromodulation mediated by MDs in primary cortical neurons and the influence of MDs size on governing actuation mechanisms. Using calcium fluorescent imaging and immunochemistry, we first study MDs co-localization and actuation on primary cortical neurons to modulate neural activity on-demand. Then, by calcium fluorescence imaging and chemical inhibition we unveil the specific mechanical actuation mechanisms of MDs that induce neural activity in magnetomechanical neuromodulation. We find that the torque produced by large MDs triggers the response of multiple types of mechanosensitive ion channels, while smaller MDs actuate through shear stress specifically on Piezo1 and/or TRPC1 ion channels. These results provide mechanistic insights of AMFs-triggered MDs actuation on primary cortical neurons, which is of critical importance for the development of magnetomechanical neuromodulation therapies.

Results and Discussion

MDs Characterization and Surface Functionalization

In our previous work, we demonstrated force-induced neural stimulation mediated by 4 μm MDs [12]. Although magnetomechanical stimulation was efficient, we believe MDs with submicrometer size are more appropriate to facilitate particle – tissue interactions [18]. Here, we utilize Ni80Fe20 MDs coated with gold fabricated by interference laser lithography with diameters of 700 and 300 nm and thickness of 100 nm. The homogeneity of permalloy MDs arrays, morphology, and dimensions were verified by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Figures 1a and c show representative SEM images. The patterning of both 700 and 300 nm diameter wide MDs is very homogenous as expected from their fabrication technique. The insets in Fig. 1a and c show a representative SEM image of higher magnification with a single MD. As observed from the SEM images, the morphology of MDs is not perfectly circular. Although the magnetomechanical properties of MDs are not affected by circularity but by their aspect ratio, we calculated circularity for reference, in which circularity = 1 indicates a perfect circle. The 700 nm MDs display a circularity of 0.4 ± 0.08, while 300 nm circularity is of 0.65 ± 0.02. The magnetic characterization of the MDs is depicted in Fig. 1b and d. The figures show the hysteresis loop of square arrays of 700 and 300 nm MDs. The 9 mm2 sample was cut from a 4-inch wafer after photoresist liftoff. The pinched shape of the hysteresis loops and the lack of magnetic moment at remanence indicates that 700 and 300 nm MDs develop a vortex state when the external field is off, which allows for on-demand mechanoactuation. A magnetic moment per disc was estimated from the saturation magnetization and the number of discs in the sample's area. The 700 nm MDs display a magnetic moment of 2.9 × 10−11 emu disc−1, and the 300 nm MDs of 1.4 × 10−11 emu disc−1. Higher magnetic moment is observed in larger discs, including our previously reported 4 μm MDs (9.8 × 10–10 emu disc–1). Still, the magnetic moment of MDs fabricated here is 100× higher than that of chemically synthesized 226 nm magnetite nanodisc (6.7 × 10–13 emu disc–1) [30], confirming once again that fabrication through lithography methods overcomes stacking resulting in MDs with enhanced magnetic moment. MDs hysteresis heat dissipation at the AMFs conditions of 18 mT and 6 Hz was measured for 100 µg of MDs in Tyrode solution. Consistent with our previous report on 4 μm MDs of the same chemical composition [12], no increase in the temperature was observed, neither for 300 nm or for 700 nm MDs solutions, nor for water alone.

Fig. 1.

MDs characterization. a SEM image of 700 nm MDs on the Si wafer. Inset image of a single MD. Scale bar = 1 µm; b Hysteresis loop of a square array of 700 nm MDs after photoresist liftoff and before release from the Si wafer; c SEM image of 300 nm MDs on the Si wafer. Inset image of a single MD. Scale bar = 1 µm; and d Hysteresis loop of a square array of 300 nm MDs after photoresist liftoff and before release from the Si wafer

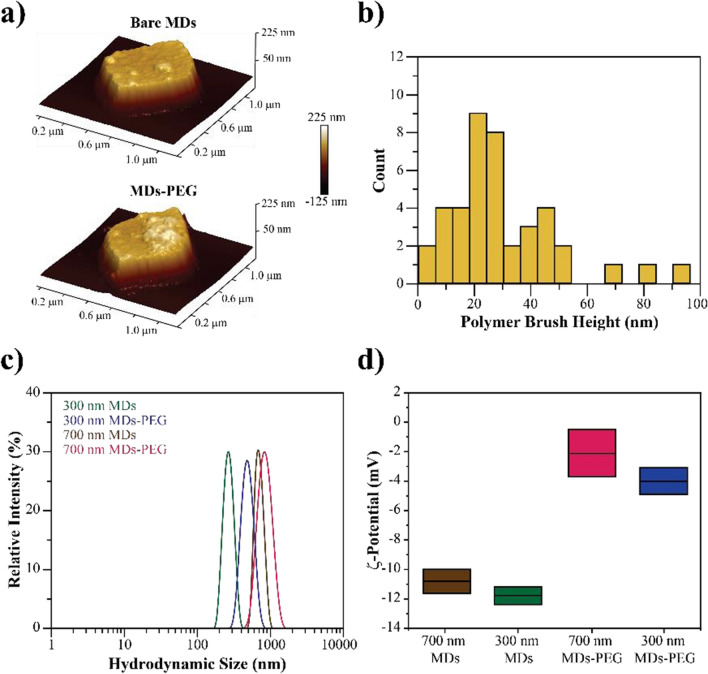

Although zero-remanence MDs are highly stable in water, we surface engineered them with polymer brushes to neutralize their charge, enhance their biological fluids' stability, avoid nonspecific interactions, and endow biorecognition functions. Polymer brushes are commonly used in surface chemistry to stabilize suspensions of colloidal particles. When polymer brushes are grafted onto particles’ surface, the entropy gain and the repulsion between polymer chains, promote steric and/or electrostatic colloidal stability [32]. First, the heterobifunctional amine-poly (ethylene glycol)-thiol (NH2-PEG-SH) and carboxylic acid-poly (ethylene glycol)-thiol (COOH-PEG-SH) were used for functionalization. NH2-PEG-SH was used for fluorescence labeling with either Rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RhdB) or Eosin isothiocyanate. The NH2 from PEG was covalently coupled to the isothiocyanate group from RhdB or Eosin, yielding Fluorescent PEG (F-PEG-SH). Similarly, COOH-PEG-SH was conjugated to anti-microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) antibody following carbodiimide chemistry between the COOH group from PEG and the NH2 groups from residual lysins in anti-MAP2 antibody, forming MAP2-PEG-SH. Then, functionalized PEG brushes were grafted to the surface of MDs through well-established thiol-gold chemistry [48, 66]. A mixture of 1:1 F-PEG-SH and MAP2-PEG-SH was used for MDs surface functionalization. The sulfur from SH functional group in both PEGs was absorbed onto the MDs gold surface forming PEG coated MDs (MDs-PEG) with fluorescence and antibody biorecognition functionalities. Figure S1a and S1b show representative fluorescent images of 700 and 300 nm MDs arrays after surface functionalization with PEG brushes. The observed fluorescence of the RhdB labeled polymer is consistent with the localization of MDs in the array. The adsorption of SH-PEGs on a gold planar surface was followed using QCM-D (Fig. S1c). The observed mass change after PEG surface functionalization was 192 ± 10 ng cm−2. MDs surface functionalization with PEG brushes was also characterized through AFM. Figures 2a and 2b show the AFM height images and height profiles for 700 nm MDs bare and coated with PEG brushes. AFM measurements show a rather smooth surface for bare MDs. After functionalization with PEG brushes an increase in surface roughness was observed along with the presence of high peaks corresponding to the polymer coating. The average thickness for PEG brushes coatings on MDs measured by AFM is of 30 ± 3 nm. The measured thickness for PEG brushes on MDs surface is consistent with previously reported values using 5 kDa PEG chains [50].

Fig. 2.

MDs surface functionalization. a AFM three-dimensional height images of bare and PEG functionalized 700 nm MDs; b Particle height distribution calculated using Nanoscope software; c Hydrodynamic size distribution of MDs before and after surface functionalization with PEG brushes; and d ζ-Potential of MDs before and after functionalization with PEG brushes

After functionalization, MDs-PEG were released from the Si wafer to obtain partially coated MDs in solution. MDs-PEG hydrodynamic size was characterized by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) in Tyrode's solution. Figure 2c shows the hydrodynamic size distribution of 700 and 300 nm MDs before and after PEG functionalization. MDs display narrow hydrodynamic size distributions with a mean diameter of 695 ± 19 nm (PDI = 0.031) for the 700 nm MDs, and 290 ± 34 nm (PDI = 0.082) for the 300 nm MDs. MDs sizes measured by SEM and DLS are consistent with each other for both, 700 and 300 nm MDs diameter. The hydrodynamic size distribution of MDs after PEG coating slightly increased to a mean diameter of 810 ± 32 nm (PDI = 0.193) for the 700 nm MDs-PEG, and of 410 ± 33 nm (PDI = 0.195) for the 300 nm MDs-PEG. The average diameters obtained from DLS for MDs-PEG are considerably higher compared to the sizes measured for bare MDs and the polymer coating thickness measured by AFM. These differences can be assigned to the nature of the measurements. Water molecules attached to PEG chains on MDs surface coating contribute to the hydrodynamic diameter measured by DLS but they cannot be detected by AFM. It is also well known that DLS utilizes particle diffusion coefficient to infer colloidal particle size via Stokes-Einstein relation [22]. MDs surface modification with functional PEG brushes was also confirmed by ζ-potential measurements, as shown in Fig. 2d. The surface charge of MDs is − 10.8 ± 0.8 mV for 700 nm MDs and − 11.8 ± 0.6 mV for 300 nm MDs. After grafting PEG to the MDs surface, the ζ-potential is neutralized to − 2.1 ± 1.6 mV for 700 nm MDs-PEG and to − 4 ± 0.9 mV for 300 nm MDs-PEG. Together, these results suggest the formation of a nanometer thick functional PEG coating on MDs surfaces.

MDs Co-localization

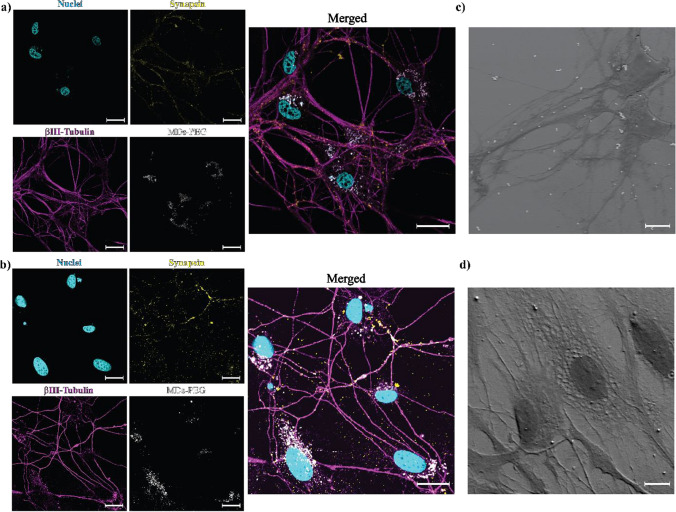

As described above, MDs-PEG are functionalized with anti-MAP2 antibody to endow MDs with a biorecognition function. In our previously reported magnetomechanical neurostimulation work [12], we observed that untargeted 4 μm MDs randomly colocalized in the cell membrane of neurons, either around the cell body or the axons. Here, we aimed to control MDs co-localization through the specific biorecognition of anti-MAP2 antibody in the cytoplasm and cytoskeleton of neurons. We investigated the co-localization of functional MDs-PEG within primary cortical neural networks. Figures 3a and 3b show representative confocal microscopy images of 700 and 300 nm MDs-PEG within cortical neurons, respectively. Cortical neurons were labeled with anti-Tubulin β-III (magenta) to identify neuronal cytoskeleton microtubular networks, with synaptophysin antibody (yellow) as a marker of presynaptic vesicles in mature neurons, and with DAPI (cyan) for nuclei identification. Eosin labeled MDs-PEG are shown in white color. We also studied MDs-PEG colocalization on the surface of neurons. Figures 3c and 3d display SEM images of cortical neurons exposed to 700 and 300 nm MDs-PEG, respectively. The 700 nm MDs-PEG are found to be colocalized mainly in the cell membrane of cortical neurons, either in the cell body or the axons (Fig. 3c). Few 700 nm MDs-PEG can internalize the cell (Fig. 3a). Oppositely, the 300 nm MDs-PEG are found to be colocalized mainly inside cortical neurons, either in the cytoplasm or cytoskeleton (Fig. 3b). Few 300 nm MDs-PEG are found in the cell membrane of cortical neurons (Fig. 3d). Small aggregations of MDs-PEG are observed in both confocal microscopy and SEM images. The aggregates are attributed to the treatment of the samples for imaging, which includes exposure to surfactants, vacuum, mechanical shaking, multiple washes with different solvents, among others. Our results clearly show the MDs size dependence on cellular uptake, which has been reported previously for different nanoparticle types [3, 18].

Fig. 3.

MDs co-localization within primary cortical neural networks. Confocal images of cortical neurons co-cultured with: a 700 nm MDs, and b 300 nm MDs. Cell cytoskeleton microtubules are stained with anti-Tubulinβ-III (magenta), presynaptic vesicles are labeled with synaptophysin antibody (yellow), nuclei counterstaining was performed with DAPI (cyan), MDs were stained with eosin isothiocyanate (white). SEM image of cortical neural networks exposed to: c 700 nm MDs, and d 300 nm MDs. Scale bar = 10 µm

On-demand Excitation of Primary Rat Cortical Neurons Mediated by MDs and AMFs

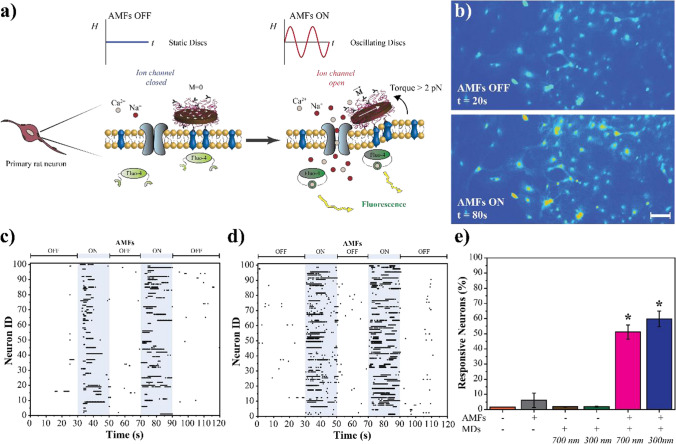

In our previous work, we studied transgene-free force-inducing neural stimulation mediated by 4 μm MDs in primary cortical neurons [12]. We utilized primary rat cortical neural cultures as they are well known to express different mechanosensitive ion channels endogenously, including TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV4, Piezo1, TRPC1, TRPM7 TRPP1/2 complex, and indirectly actuated G-protein coupled receptors [10, 54]. Here, we build upon previous work to demonstrate the on-demand control of cortical neural activity triggered by mechanoactuation of 700 and 300 nm functional MDs under applied AMFs (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows calcium images from a representative video of cortical neurons subjected to magnetomechanical stimulation mediated by 700 nm MDs. The calcium imaging video was recorded for 2 min at a frame rate of 4 frames per second. The AMFs stimulation was applied in two cycles of 20 s ON–20 s OFF, allowing the first 30 s to serve as a baseline.

Fig. 4.

Magnetomechanical stimulation of primary cortical neurons mediated by MDs. a An overview of the experimental scheme. Functionalized MDs in co-culture with primary rat neurons. Upon exposure to AMFs, the torque produced by MDs triggers the response of specific ion channels located in the cell membrane. This response gates calcium ion influx detectable through the dynamic fluorescence of Fluo-4; b Calcium fluorescence images from a representative video of cortical neurons subjected to magnetomechanical stimulation in 20 s pulses mediated by 700 nm MDs at the AMFs conditions of 18mT and 6 Hz. Scale bar = 50 µm; Raster plot tracking the activity of 100 random neurons co-cultured with: c 700 nm MDs, and d 300 nm MDs, and exposed to AMFs. The blue shadowed area indicates the exposure to AMFs; e Percent response was determined by dividing the number of neurons that were active during AMFs exposure by the total number of neurons in the field of view. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 5 samples per condition). ANOVA and the post-hoc Tukey test (α = 0.05) was performed to determine statistical significance. * Indicates statistical difference with Negative Control (neurons in the absence of AMFs and MDs)

MDs mechanoactuation on cortical neurons results in the enhancement of transmembrane channels that lead to an influx of calcium ions in the cell. The calcium images illustrate this increase in fluorescence intensity of intracellular calcium. Representative videos for magnetomechanical stimulation of cortical neurons mediated by both 700 and 300 nm MDs are shown in the Supporting Information Video S1 and Video S2. The recorded videos were analyzed for intracellular calcium fluorescence over time to quantify cell activity. A custom MATLAB code was created and used to subtract the background and randomize the results presented here (code available in Supporting Information). In our results, a threshold relative to three times the standard deviation from the background was set to distinguish active cells from inactive cells. Figure 4c and d display the activity of 100 random neurons during magnetomechanical stimulation mediated by 700 and 300 nm MDs, respectively. In both figures, the blue shadowed areas indicate the two 20 s cycles of exposure to AMFs. Figure 4e summarizes the percentage of responsive cortical neurons quantified from five different samples in each condition. Cortical neurons in the absence of AMFs and MDs were used as a negative control. Representative raster plots and the percentage of active neurons of 100 random neurons for the controls are shown in Fig. S2.

Regardless of the MDs size, we were able to detect neural activity in cortical cultures within seconds of applying AMFs stimulus. During the recovery time (20 s of AMFs OFF) minimal cell activity was detected. These results suggest that neural activity in magnetomechanical stimulation can be controlled on-demand through AMFs exposure. The applied 20 s of AMFs was sufficient for both 700 and 300 nm MDs to evoke neural activity through magnetomechanical transduction. When mediated by 700 nm MDs, ~ 50% of cortical neurons were responsive to the treatment while a higher percentage of responsive neurons (> 60%) was observed when treatment was mediated by 300 nm MDs. Although the difference is not statistically significant, one can infer that as 300 nm MDs are lighter than 700 nm MDs, they can oscillate faster to align with the magnetic field. Faster response to AMFs stimulus results in better transduction into mechanical forces, thus better mechanoactuation on the cells. Neural activity was significantly higher in cortical neurons co-cultured with MDs (700 or 300 nm) and exposed to AMFs in comparison to the controls.

Elucidating Mechanotransduction Processes During Neurostimulation Mediated by MDs and AMFs

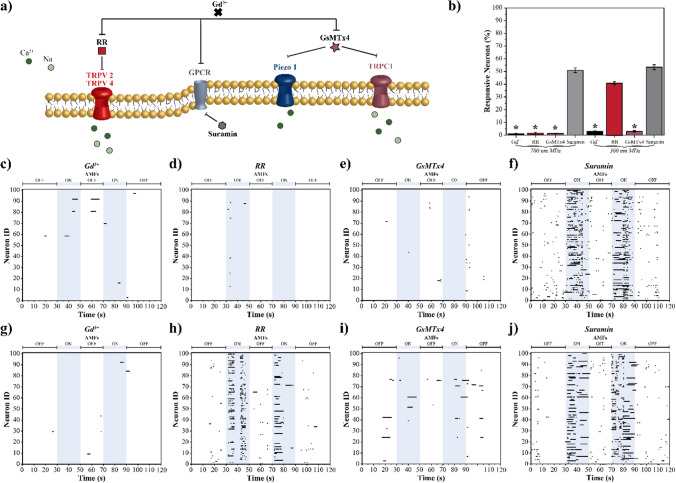

The hypothesis of this work is that AMFs-triggered actuation of MDs on neurons excites activity through the activation of mechanosensitive ion channels. Thus, we investigated the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of this magnetomechanical neuromodulation approach. It is well known that primary cortical neurons endogenously express different mechanosensitive ion channels. To determine which channels are involved, we chemically block subsets of mechanosensitive ion channels prior to magnetomechanical neuromodulation treatment as shown in Fig. 5a. The dose of ion channel chemical inhibitors was carefully chosen to avoid altering neural activity by blocking non-mechanosensitive channels. First, we treated primary cortical neurons with gadolinium (III) (Gd3+), which is a well-studied general inhibitor for mechanosensitive channels that acts by modifying the deformability of the lipid bilayer [8]. In the presence of Gd3+, the evoked activity in cortical neurons co-cultured with either 700 or 300 nm MDs and exposed to AMFs was significantly reduced, almost 100% reduction in comparison with their respective controls (Fig. 5c and g). These results confirmed that mechanosensitive channels are involved in MDs transduction mechanism.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of mechanosensitive ion channels during magnetomechanical stimulation of primary cortical neurons mediated by MDs. a An overview of the experimental scheme. Different chemical inhibitors were used to block subsets of mechanosensitive ion channels prior to magnetomechanical neurostimulation; b Percent of responsive neurons determined by dividing the number of neurons that were active during AMFs exposure by the total number of neurons in the field of view. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 5 samples per condition). ANOVA and the post-hoc Tukey test (α = 0.05) was performed to determine statistical significance. * Indicates statistical difference with Positive Control (neurons in the presence of AMFs and MDs); Raster plot tracking the activity of 100 random neurons inhibited with Gd3+ and co-cultured with: c 700 nm MDs, and g 300 nm MDs; pretreated with RR and co-cultured with: d 700 nm MDs, and h 300 nm MDs; pretreated with GsMTx4 and co-cultured with: e 700 nm MDs, and i 300 nm MDs; pretreated with Suranim and co-cultured with: f 700 nm MDs, and j 300 nm MDs. The blue shadowed areas indicates the exposure to AMFs

Then, we used selective chemical blockers to inhibit distinct subsets of mechanosensitive ion channels. We used ruthenium red (RR) to block TRPV2 and TRPV4 channels [81]. TRPV2 is sensitive to membrane stretch, TRPV4 to fluid shear stress and both are to hypotonic cell swelling [62]. For 700 nm MDs, pre-treatment with RR significantly reduced the evoked activity in cortical neurons, suggesting that TRPV2 and TRPV4 are involved in magnetomechanical transduction (Fig. 5d). In contrast, the resulting evoked neural activity when using 300 nm MDs (Fig. 5h) was not significantly different from stimulation in the absence of RR (positive control, Fig. 4d), suggesting that these channels are not involved in the mechanotransduction mechanism of 300 nm MDs. RR blockage results indicate that mechanotransduction through the activation of TRPV2 and TRPV4 is dependent on MDs size. The forces exerted by 700 nm MDs may be larger than those exerted by 300 nm MDs in the presence of AMFs. Larger forces are needed to modify the cell membrane stretch and fluid shear stress which results in TRPV2 and TRPV4 activation. Next, we tested the role of the Piezo1 and TRPC1 channels. While TRPC1 is sensitive to membrane stretch [52], Piezo1 is sensitive to intracellular and extracellular radial pressure, membrane stretching, compression, shear stress, matrix stiffness, and osmotic pressure [2, 47]. To inhibit both Piezo1 and TRPC1, we pretreated cortical neurons with GsMTx4 peptide, which works by inserting into the stressed cell membrane to distort tension near Piezo and TRPC1 [29, 76]. Cortical neurons pretreated with GsMTx4 showed a significant reduction in responsiveness to magnetomechanical neuromodulation mediated by either 700 nm (Fig. 5e) or 300 nm MDs (Fig. 5i). This indicates that Piezo1 and/or TPRC1 channels are involved in magnetomechanical neuromodulation. Finally, we study the involvement of indirectly actuated G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) in magnetomechanical neuromodulation. GPCR are sensitive to fluid shear stress and cell stress [82]. We used suramin to block GPCR signaling via GDP release inhibition [25]. Cortical neurons pretreated with suramin showed no significant change in their response to magnetomechanical neuromodulation mediated by either 700 nm (Fig. 5f) or 300 nm MDs (Fig. 5j) in comparison to their respective controls (Fig. 4c and d, respectively), suggesting that GPCRs are not involved in MDs mechanotransduction. Figure 5b summarizes the percentage of responsive cortical neurons quantified from five different samples in each chemical inhibition condition. Cortical neurons subjected to magnetomechanical treatment with either 700 or 300 nm MDs were used as a positive control. Combinations of chemical blockers were not tested as it has been suggested that their combination could potentially disturb cell viability and excitability [87]. From these results, it is possible to infer that specificity in the mechanisms of MDs mechanoactuation is dependent on size and therefore in MDs co-localization within the cell. The 700 nm MDs largely co-localize in the cell membrane, thus magnetomechanical actuation is on a combination of channels (TRPV2, TRPV4, Piezo1 and TRPC1). Contrary, the 300 nm MDs mainly co-localize inside the cell and actuate only on Piezo1 and TRPC1 channels. None of the chemical blockers we utilized delayed neural activity response to magnetomechanical neuromodulation treatment. Future studies will pursue the genetic knockdown of TRPV1, TRPV4, Piezo1 and TRPC1 to further elucidate the specific contributions of each channel.

Biological Impact of Magnetomechanical Neurostimulation Mediated by MDs

We evaluated the impact of magnetomechanical neurostimulation on cortical neurons. In all tests we utilized 700 nm MDs as per prior findings in co-localization and inhibition studies that suggest larger MDs to be more influential in cell responses. We first investigated whether the forces exerted by MDs under applied AMFs are able to damage the cell membrane through perforation. Intact cortical neuronal cultures and cultures exposed to magnetomechanical neurostimulation treatment were stained with Propidium Iodide and imaged to visualize potential cell membrane damages [14]. Images were analyzed to quantify the number of cells stained with Propidium Iodide (Fig. S3). No statistical difference was detected in cell membrane damage between intact cortical neurons and neurons exposed to magnetomechanical treatment (both < 3%), suggesting that the forces exerted by MDs on the cells do not perforate neural cell membrane.

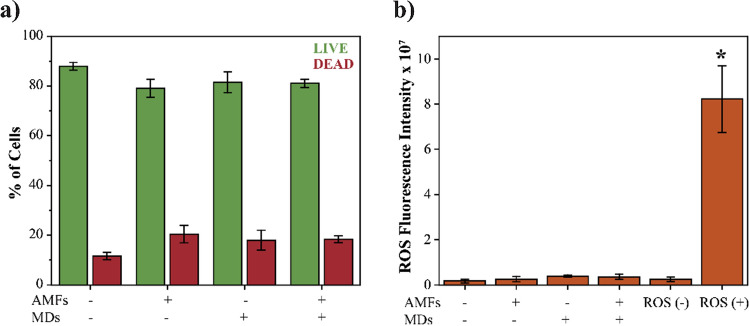

The cell viability of magnetomechanical neurostimulation was studied by LIVE/DEAD assay using flow cytometry for quantification. Figure 6a displays cell viability in terms of percentage of live and dead cells for all the tested groups. There is no statistical significance between the percentage of live and dead cells from intact cortical neurons (AMFs (−) MDs (−), negative control) and the other tested groups including cortical neurons exposed to magnetomechanical treatment (AMFs (+) MDs (+)). These results indicate the non-cytotoxic nature of magnetomechanical neurostimulation platform. Although there is not enough evidence of the detrimental properties of AMFs, MDs or mechanotransduction, it has been suggested that nanotechnologies could disrupt reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radical production [55], thus we evaluated the magnetomechanical neurostimulation for ROS production (Fig. 6b). No statistical difference was found in the level of ROS production by intact cortical neurons (AMFs (−) MDs (−)) and the other tested groups including cortical neurons exposed to magnetomechanical treatment (AMFs (+) MDs (+)) and the ROS negative control of the assay (ROS (−)). Higher levels of ROS production were only detected in the assay positive control (ROS (+)).

Fig. 6.

Biological impact of magnetomechanical neurostimulation mediated by MDs. a LIVE/DEAD assay; and b ROS assay of primary cortical neurons exposed to magnetomechanical neurostimulation and respective control groups. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 4 samples per condition). ANOVA and the post-hoc Tukey test (α = 0.05) were performed to determine statistical significance. * Indicates statistical difference with the control of intact cells (AMF (−) MDs (−))

Conclusion

The results of this study provide a detailed biophysical and molecular description of the mechanisms by which magnetomechanical neuromodulation mediated by MDs can evoke activity in primary cortical neurons. The use of primary cortical neurons as a model system and chemical inhibition of mechanosensitive ion channels allowed us to unveil the mechanisms of magnetomechanical neurostimulation in detail. The actuation of MDs on the cells when exposed to AMFs is driven by mechanical interactions, which trigger the opening of specific mechanosensitive calcium ion channels. It was found that mechanoactuation of MDs is size-dependent. While magnetomechanical neurostimulation with 700 nm MDs triggers the response of TRPV2, TRPV4, Piezo1 and TRPC1, 300 nm MDs actuate only through the response of Piezo1 and/or TRPC1. The observed MDs size dependence on magnetomechanical neurostimulation mechanism is correlated with MDs co-localization within the cell. Magnetomechanical stimulation of cortical neurons can be controlled on-demand by AMFs exposure. Nor MDs, AMFs or the magnetomechanical neurostimulation treatment are cytotoxic or cause detrimental effects on neurons.

Several questions remain open for further study. In general, our inhibition experiments suggest that magnetomechanical neurostimulation results from mechanical stretch and stress of the cell membrane. However, the precise forces and nanoscale deformations caused by MDs under applied AMFs remain elusive. Theoretical calculations accompanied biophysical techniques to measure nanoscale forces must be studied [16, 26, 89]. Here we identified TRPV2, TRPV4, Piezo1 and TRPC1 as mechanosensitive ion channels involved in magnetomechanical neurostimulation, however, we must decouple the contribution of each channel through their genetic knockdown. Magnetomechanical neuromodulation needs to be further investigated in different neural populations to gain knowledge about the impact on mechanosensitive ion channel expression levels. Future research will also include the translation of this technology to in vivo models, which will require surface engineering MDs with specific recognition functions to bypass the blood-brain barrier and enhance co-localization in the brain, as well as investigating noninvasive delivery pathways and optimizing magnetomechanical neurostimulation in specific animal disease models. Although AMFs can penetrate deep into biological matter, it is critical to ensure MDs torque performance at viscosities relevant to biological tissues. Recent work supports the translation of magnetomechanical treatments into 3D tissue models. Magnetomechanical neuromodulation using magnetic microclusters as transducers has been demonstrated in organoid [24] and in mice [39, 43] models, while the efficiency of MDs magnetomechanical forces to destroy gliomas has been shown in a glioma mouse model [9]. These in vivo studies rely on intracranial particle administration, which is invasive and will limit the potential clinical translation of magnetomechanical treatments. Thus, noninvasive administration alternatives to the brain need to be developed. For instance, intravenous administration of magnetic particles can be combined with photodynamic therapy [51, 77], magnetic hyperthermia [78], focused ultrasound [11] or transcranial magnetic stimulation [80] to enhance BBB permeability and co-localization of particles into the brain.

Furthermore, the on-demand magnetomechanical modulation of mechanosensitive ion channels shown in this work has the potential to be applied in cancer research and regenerative medicine. Recent reports have shown Piezo1 modulation as an alternative pathway to treat cancer tumors. Piezo1 is involved in tumor angiogenesis, metastasis, survival and apoptosis, and its inhibition has been investigated to hamper these processes [19, 59]. Piezo1 also has been reported as sensitizer of the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) pathway and its activation with Yoda1 (agonist) enhances TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in glioblastoma cells [36, 42]. Activation of the mechanosensitive potassium ion channel TREK1 has been reported to initiate different cell membrane stress processes that lead to the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to osteocytes [34, 38, 40] and of neuroblastoma cells to neurons [72].

We foresee that the mechanistic insights obtained in this study may serve to move forward magnetomechanical neurostimulation mediated by MDs, facilitating the wireless control of biological signaling in basic neuroscience research. Magnetomechanical stimulation using MDs is compatible with the scalability of AMFs setups which is anticipated to accelerate the development and clinical translation of noninvasive therapies for brain disorders.

Experimental Section/Methods

MDs Fabrication and Characterization

Permalloy (Ni80Fe20) MDs were fabricated using top-down lithography techniques. A four-inch silicon (Si) wafer was spin-coated with photoresist. A Lloyd’s mirror interference lithography setup with a He-Cd laser (wavelength = 325 nm) was used for resist patterning. A double exposure yields square arrays of quasi-circular holes after developing. Then, a multilayer structure was deposited by electron beam evaporation in a high vacuum. Aluminum (20 nm)/Gold (5 nm)/Ni80Fe20 (100 nm)/Gold (5 nm) layers were consecutively evaporated on the resist template. A liftoff process removed the resist leaving MDs attached to the Si wafer. Prior to detachment of the MDs, small pieces of the wafer were cut to study morphology and size by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S5500). SEM images were analyzed in ImageJ for size and circularity. First, the images were set to a threshold that divided the pixels of the MDs and the background. Then MDs were analyzed for size and circularity using the “Analyze Particles” plugin. For MDs size, the measurement for the major axis was used and reported as mean size ± standard error. Circularity was calculated in ImageJ by: , being 1 if a perfect circle. The threshold was adjusted to ensure that only MDs were considered in the analysis.

The magnetic properties of MDs were characterized using a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM, VersaLab Quantum Design). The samples were measured prior detachment at a frequency of 40 Hz and temperature of 300 K. MDs hysteresis heat dissipation was characterized from calorimetry measurements using a custom magnetic system composed of a 50 mm copper varnished wire solenoid driven by a DC-300 amplifier with an input signal of 5 V. MDs at 100 µg mL–1 in water were exposed to 60 seconds of an AMFs of 18 mT and 6 Hz. A thermocouple (Qualitrol Neoptix) was inserted into the solution during the measurement to monitor and record the temperature changes.

MDs Surface Functionalization

MDs were functionalized while attached to the Si-wafer. First, bifunctional amine-poly (ethylene glycol)-thiol (NH2-PEG-SH, Layson Bio.) was fluorescently labeled with either rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RhdB) or eosin isothiocyanate (Sigma Aldrich). Briefly, NH2-PEG-SH (5 mg mL−1) and RhdB or eosin isothiocyanate (10 μM) were dissolved in phosphate buffer at pH 8.6. The reaction was carried out overnight at room temperature. Then, the resulting polymers were dialyzed (3000 Da membrane from Spectrum Laboratories) against millipore water at 4 °C for 24 h. Purified labeled polymer was lyophilized (Labconco freeze dryer).

Then, bifunctional carboxylic acid-poly (ethylene glycol)-thiol (COOH-PEG-SH) was conjugated to anti-microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) antibody following carbodiimide chemistry. COOH-PEG-SH and anti-MAP2 antibody were mixed at a final concentration of 10 mM in millipore water. After 30 min of incubation the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8.6. The reaction was carried out at 4 °C for 48 h after which the polymer was dialyzed and lyophilized.

Finally, both polymers, fluorescently labeled PEG-SH and antiMAP-PEG-SH, were dissolved in absolute ethanol (Sigma Aldrich) at a 1:1 mass ratio. The polymer solution was added to the MDs attached to the Si-wafer for functionalization through the reaction of SH from the polymers with the gold surface of MDs. The reaction was carried out under vortex for 48 h, after which the wafers were washed thoroughly with millipore water.

Functionalized MDs were detached from the aluminum sacrificial layer using a 1 M potassium hydroxide (KOH, Sigma Aldrich) solution in an ultrasonication bath. Following detachment, MDs were aggregated together by using a neodymium magnet, washed three times with Millipore water and resuspended by ultrasonication each time. Detached MDs were characterized for size and ζ-potential in Tyrode’s solution by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS, Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS). Fluorescent labeling was confirmed through confocal microscopy imaging (Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope with Nikon A1 confocal microscope). The number of MDs in solution was approximated from particle counting (BD Accuri C6 Plus).

Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D)

QCM-D was performed to confirm the surface chemistry protocol. Measurements were performed on a QSense Explorer microbalance with a single channel (Biolin Scientific). A 14 mm diameter gold-coated quartz crystal with a fundamental frequency of 5 MHz was used as a sensor (QSX 301, Biolin Scientific). First, a baseline of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was recorded. Then, ethanol was injected into the QCM-D flow module. Following, 1 mg mL−1 of RhdB-PEG-SH in absolute ethanol was injected and incubated overnight. Excess of RhdB-PEG-SH was removed through a wash with ethanol. Finally, PBS was injected in the flow module. The QCM-D frequency and dissipation were recorded for seven odd overtones (1st–13th). Changes in resonance frequency (ΔF) and dissipation (ΔD) were monitored throughout the experiments. The relationship between DF monitored by QCM-D and adsorbed mass was calculated using Sauerbrey Equation [69, 74]:

with the mass sensitivity constant of the crystal and i the overtone number.

The ratio of dissipation and normalized frequency shifts, , were smaller than 0.4 × 10−6 Hz−1 [70], fulfilling the conditions to use Sauerbrey equation [69].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

For AFM measurements, 700 nm bare MDs and PEG functionalized MDs were used. Images were collected in tapping mode with a Bruker MultiMode 8 AFM equipment using MLCT-BIO cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of 0.6 N m−1 and resonant frequency in the range of 90 to 160 kHz (Bruker AFM Probes). All measurements were performed in PBS.

Isolation and Maintenance of Primary Rat Cortical Neurons

Sprague Dawley rat pups 1–2 days old, male and female, were euthanized as per the UTSA Institutional Animal Care Program (IACUC) guidelines. Primary cortical neurons were extracted from the brains of newborn rat pups, isolated, and cultured as per literature protocols [49]. Briefly, cortical neurons were isolated using an enzymatic solution containing papain (Sigma-Aldrich) and DNAase1 (Sigma-Aldrich) to digest the connective tissues. After 25 min, an inactivation solution was added to stop enzymatic digestion. Next, the tissues were triturated carefully to isolate individual cortical cells. Isolated cells were filtered and collected by centrifugation for 7 min at 4000 rpm. Cell density was determined using a cell counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 350,000 cells were seeded into 35 mm glass bottom petri dishes coated with Poly-D-Lysine (Mattek). Neurons were cultured in neurobasal media supplemented with 2% B27, 1% Glutamax-I, and 1% Pen-Strep (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 24 h, half of the culture media of each dish was replaced. After 3 days, 50 μL of FUDR solution (Sigma Aldrich, 400 μL of FUDR stock and 3.6 mL of culture media) was added to inhibit glial cell growth. Half of the culture media was replaced weekly for maintenance of the cultures. Healthy neural cultures 2–3 weeks old from the date of extraction were used for the stimulation experiments.

Immunochemistry

Fluorescent staining of primary cortical neurons cytoskeleton microtubules, presynaptic vesicles, and cell nucleus was performed on cell cultures exposed to magnetomechanical neurostimulation and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing 3 times with washing solution (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (BP337, Fisher Bioreagents)), cells were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 (T8787, Sigma Aldrich) for 10 min followed by 3 cycles of rinsing with washing solution. Then, 1% of bovine serum albumin (0332, VWR) in PBS was incubated for 1 hour for blocking. The blocking solution was removed and anti-Tubulinβ-III antibody (clone TU-20, Alexa Fluor555 Conjugate, CBL412A5 from Sigma Aldrich) and mouse monoclonal synaptophysin antibody (Alexa Fluor647 Conjugate, NBP147483AF647 from Novus Biologicals) were diluted in blocking solution, added to the samples, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, samples were washed 3 times and incubated with DAPI in PBS for 5 min (Sigma Aldrich). Finally, samples were washed and kept in PBS before imaging in a Nikon A-1 confocal microscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Imaging of Neurons

Previously fixed samples of primary cortical neurons exposed to magnetomechanical neurostimulation were washed with PBS. Then, the cells were gradually dehydrated in a series of ethanol dilutions (0%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 35%, 50%, 65%, 75%, 90%, 100%) in millipore water for 5 min each, finishing with an overnight incubation at 4 ℃ in 100% ethanol. The glass bottom from the petri dish was removed and subjected to critical point drying with CO2 (Leica EM CPD300). The samples were mounted on aluminum pin stubs using double-sided carbon tape and coated with gold (PELCO SC-7 Sputter Coater) before SEM imaging (Zeiss Crossbeam 340).

Magnetomechanical Neurostimulation and Fluorescence Calcium Imaging

MDs were co-cultured with primary cortical neurons at a rate of ~ 35 MDs per cell. Neurons were then stained with the fluorescent calcium indicator Fluo-4 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer‘s protocols. Magnetomechanical stimulation of neural cultures was recorded through calcium fluorescence imaging in Tyrode‘s solution. Exposure to the alternating magnetic fields (AMFs) took place in a custom sample holder designed to hold a 35 mm petri fitting into a 50 mm copper varnished wire solenoid driven by a DC-300 amplifier with an input signal of 5 V. Each sample was exposed to the magnet for 2 min in two AMFs cycles of 20 s ON–20 s OFF. A fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica M205 FCA) equipped with 2× and 5× Plan Apo objectives, and a sCMOS camera (Leica DFC9000) were used to record calcium cell activity during stimulation. Five videos of the following groups were recorded: AMFs (−) MNDs (−), AMFs (+) MNDs (−), AMFs (−) 700 nm MNDs (+), AMFs (−) 300 nm MNDs (+), AMFs (+) 700 nm MNDs (+), and AMFs (+) 300 nm MNDs (+).

Inhibition of Mechanosensitive Ion Channels During Magnetomechanical Neurostimulation

Inhibition experiments were carried out following the same protocol described above but using primary cortical neural cultures pretreated with different chemical inhibitors. The concentration and incubation period for each ion channel inhibitor was chosen based on previous literature for mechanosensitive ion channel inhibition in primary cortical neurons [87]. Gadolinium III chloride (Gd3+, Sigma Aldrich) was applied to cells at a final concentration of 20 μM in Tyrode’s solution. Technical grade ruthenium red (RR, Sigma Aldrich) was applied to cells at 1 μM in Tyrode’s solution. Suramin (Millipore) at 60 μM in neurobasal media was incubated with cells for 1 h prior to stimulation. GsMTx4 (Abcam) was incubated for 2 h at 2.5 μM in neurobasal media prior to stimulation. Five videos of the following groups were recorded: Gd3+ (+) 700 nm MNDs (+), Gd3+ (+) AMFs (+) 300 nm MNDs (+), RR (+) 700 nm MNDs (+), RR (+) AMFs (+) 300 nm MNDs (+), GsMTx4 (+) 700 nm MNDs (+), GsMTx4 (+) AMFs (+) 300 nm MNDs (+), Suramin (+) 700 nm MNDs (+), and Suramin (+) AMFs (+) 300 nm MNDs (+).

Analysis of Calcium Imaging

Videos were analyzed by using previously established protocol for data analysis on Fluorescence Calcium Imaging [12]. First, the videos were extracted as mp4 files calibrated for brightness and contrast in Adobe Photoshop and exported as image sequence files. Using ImageJ, optical drifting was corrected using the image stabilizer plugin. Once stabilized, the fluorescence intensity trace for every distinct neuron in the video was extracted using time series analyzer plugin. A total of 200–400 neurons were selected per video. The five different videos per group tested were analyzed together in an automatic MATLAB code (Supplementary Note). The MATLAB code subtracted the baseline of each trace, determined a threshold to differentiate regular neural activity from evoked neural activity and present the results for 100 random neurons. These output data were used to represented neural activity.

Cell Viability

Primary cortical neurons were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 10,000 cells per well to study cell viability following magnetomechanical neurostimulation. The following groups were tested in four replicates: AMFs (−) 700 nm MNDs (−), AMFs (+) 700 nm MNDs (−), AMFs (−) 700 nm MNDs (+), and AMFs (+) 700 nm MNDs (+). The Live Dead Assay kit by Invitrogen was used with a flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6 Plus) for quantification. Each sample was washed with 100 μL of PBS, then the cells were detached using 50 μL of TrypleE (Gibco) and suspended in FACS solution. The cell suspension was stained with Calcein (0.1 μL from a 4 × 10−3 M stock) and Sytox (0.1 μL from a 2 × 10−3 M stock) and immediately measured. Additionally, sample cells stained with Calcein only or Sytox only and unstained cells were used for color compensation.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

Production of ROS was measured using the DCFDA / H2DCFDA - Cellular ROS Assay Kit by Abcam. Primary cortical neurons were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 10,000 cells per well and maintained according to the previously described protocols. Prior to treatment, cells were washed and stained following the procedure by the manufacturer. The following treatment groups were tested in replicates of four: AMFs (−) 700 nm MNDs (−), AMFs (+) 700 nm MNDs (−), AMFs (−) 700 nm MNDs (+), and AMFs (+) 700 nm MNDs (+). Additionally, cells subjected to ROS positive and ROS negative control treatments and untreated were tested. Each well was imaged in a Nikon A-1 confocal microscope. Standardized analysis of fluorescence for each sample was processed in ImageJ using Auto Threshold and then measuring the integrated density of the pixels in the image.

Cell Membrane Damage

Cell membrane damage was determined by following the methods described by Corrotte et al. [14] to measure the influx of Propidium Iodide into cortical neurons after magnetomechanical neurostimulation. The neurons were incubated with ice-cold Propidium Iodide (Alfa Aesar) for 5 min, washed with PBS, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After fixing, 300 nM of DAPI (Sigma) was added to the cells to stain the nuclei and washed with PBS. Immediately after staining, cells were imaged in a Nikon A-1 confocal microscope to capture triplicate images of each dish with approximately 700 neurons per image. Quantification was performed by counting the total number of DAPI and Propidium Iodide-stained cells in ImageJ.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), Grant R56EB031848. Rafael Morales and Carolina Redondo acknowledge funding support from the EU Horizon 2020 MSCA grant agreement No 734801, grant No PID2019-104604RB-C33/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and the Basque Country grant No IT1491-22. Amanda Gomez thanks the National Science Foundation for their support under the Graduate Research Fellowship Program (Award 1000317285).

Gabriela Romero

is a Klesse Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Chemical Engineering at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). Dr. Romero received her B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi, Mexico in 2007, a M.S. in Advanced Materials Engineering in 2009, and a Ph.D. in Applied Chemistry and Polymer Science in 2012 from the Universidad del Pais Vasco, Spain. After completing her graduate studies, she held postdoctoral positions at the University of Kentucky (2012–2013) in the group of Prof. Brad Berron, and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013–2015) in the group of Prof. Polina Anikeeva. Prior to joining UTSA, she worked for two years as a Senior Scientist at Poseida Therapeutics. Dr. Romero’s primary research interests involve the investigation of biomedical soft materials and hybrid platforms as therapeutic tools for the treatment of brain diseases. Dr. Romero’s research has been funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and the National Science Foundation, including the NSF CAREER award. Dr. Romero’s academic career philosophy is capitalized in supporting her continued development as an advocate for minority participation in advanced science and engineering education, particularly the participation and mentoring of Latinas in Engineering.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed and approved by the appropriate institutional committees.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Allenby C, et al. Transcranial direct current brain stimulation decreases impulsivity in ADHD. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(5):974–981. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagriantsev SN, Gracheva EO, Gallagher PG. Piezo proteins: regulators of mechanosensation and other cellular processes*. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289(46):31673–31681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.612697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, et al. Role of nanoparticle size, shape and surface chemistry in oral drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2016;238:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlim MT, Neufeld NH, Van den Eynde F. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD): an exploratory meta-analysis of randomized and sham-controlled trials. J. Psychiatric Res. 2013;47(8):999–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho-de-Souza JL, et al. Photosensitivity of neurons enabled by cell-targeted gold nanoparticles. Neuron. 2015;86(1):207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, et al. Continuous shape- and spectroscopy-tuning of hematite nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49(18):8411–8420. doi: 10.1021/ic100919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen R, et al. Wireless magnetothermal deep brain stimulation. Science. 2015;347(6229):1477–1480. doi: 10.1126/science.1261821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, et al. The events relating to lanthanide ions enhanced permeability of human erythrocyte membrane: binding, conformational change, phase transition, perforation and ion transport. Chemico-biol. Interact. 1999;121(3):267–289. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(99)00109-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Y, et al. Rotating magnetic field induced oscillation of magnetic particles for in vivo mechanical destruction of malignant glioma. J. Control. Release. 2016;223:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen AP, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8(7):510–521. doi: 10.1038/nrn2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu P-C, et al. Focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening: association with mechanical index and cavitation index analyzed by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic-resonance imaging. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):33264. doi: 10.1038/srep33264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collier C, et al. Wireless force-inducing neuronal stimulation mediated by high magnetic moment microdiscs. Adv. Healthc Mater. 2022;11(6):2101826. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202101826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coppola G, et al. Clinical neurophysiology of migraine with aura. J. Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):42–42. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0997-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrotte M, et al. Approaches for Plasma Membrane wounding and Assessment of Lysosome-Mediated Repair Responses. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 139–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costanzo F, et al. New treatment perspectives in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: the efficacy of non-invasive brain-directed treatment. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018;12:133. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deo C. Hybrid fluorescent probes for imaging membrane tension inside living cells. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6(8):1285–1287. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinur-Klein L, et al. Smoking cessation induced by deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal and insular cortices: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;76(9):742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolai J, Mandal K, Jana NR. Nanoparticle size effects in biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021;4(7):6471–6496. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c00987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dombroski JA, et al. Channeling the force: piezo1 mechanotransduction in cancer metastasis. Cells. 2021;10(11):2815. doi: 10.3390/cells10112815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumas RK, et al. Temperature induced single domain–vortex state transition in sub-100nm Fe nanodots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91(20):202501. doi: 10.1063/1.2807276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duyn JH. Studying brain microstructure with magnetic susceptibility contrast at high-field. NeuroImage. 2018;168:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Einstein A. Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen. Annal. Phys. 1905;322(8):549–560. doi: 10.1002/andp.19053220806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endo M, Maruoka H, Okabe S. Advanced technologies for local neural circuits in the cerebral cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 2021;15:757499. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2021.757499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fattah, A.R.A., et al., Local actuation of organoids by magnetic nanoparticles. bioRxiv, 2022: p. 2022.03.17.484696.

- 25.Freissmuth M, et al. Suramin analogues as subtype-selective G protein inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49(4):602–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García-Calvo J, et al. Fluorescent membrane tension probes for super-resolution microscopy: combining mechanosensitive cascade switching with dynamic-covalent ketone chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142(28):12034–12038. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George MS, Taylor JJ, Short B. Chapter 33 - Treating the depressions with superficial brain stimulation methods. In: Lozano AM, Hallett M, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghanouni P, et al. Transcranial MRI-guided focused ultrasound: a review of the technologic and neurologic applications. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015;205(1):150–159. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gnanasambandam R, et al. GsMTx4: mechanism of inhibiting mechanosensitive ion channels. Biophys. J. 2017;112(1):31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregurec D, et al. Magnetic vortex nanodiscs enable remote magnetomechanical neural stimulation. ACS Nano. 2020;14(7):8036–8045. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guhn A, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex stimulation modulates the processing of conditioned fear. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8:44. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guntnur RT, et al. Phase transition characterization of poly(oligo(ethylene glycol)methyl ether methacrylate) brushes using the quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Soft Matter. 2021;17(9):2530–2538. doi: 10.1039/D0SM02169E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heeren A, et al. Impact of transcranial direct current stimulation on attentional bias for threat: a proof-of-concept study among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017;12(2):251–260. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henstock JR, et al. Remotely activated mechanotransduction via magnetic nanoparticles promotes mineralization synergistically with bone morphogenetic protein 2: applications for injectable cell therapy. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014;3(11):1363–1374. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho DN. Chapter 15 - Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Alternating Magnetic Fields. In: Chen X, Wong S, editors. Cancer Theranostics. Oxford: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hope JM, et al. Activation of Piezo1 sensitizes cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis through mitochondrial outer membrane permeability. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(11):837. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang H, et al. Remote control of ion channels and neurons through magnetic-field heating of nanoparticles. Nat Nano. 2010;5(8):602–606. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes S, et al. Selective activation of mechanosensitive ion channels using magnetic particles. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2008;5(25):855–863. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong S, et al. Hydrogel magnetomechanical actuator nanoparticles for wireless remote control of mechanosignaling in vivo. Nano Lett. 2023;23(11):5227–5235. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c01207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanczler Janos M, Magnay Julia SHS, David G, Oreffo Rechard O, Dobson Jon P, El Haj Alicia J. Controlled differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells using magnetic nanoparticle technology. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2010;16(10):3241–3250. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D-H, et al. Biofunctionalized magnetic-vortex microdiscs for targeted cancer-cell destruction. Nat. Mater. 2010;9(2):165–171. doi: 10.1038/nmat2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knoblauch SV, et al. Chemical activation and mechanical sensitization of piezo1 enhance TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in glioblastoma cells. ACS Omega. 2023;8(19):16975–16986. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c00705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J-U, et al. Non-contact long-range magnetic stimulation of mechanosensitive ion channels in freely moving animals. Nat. Mater. 2021;20(7):1029–1036. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-00896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Legon W, et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of the human primary motor cortex. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):10007. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levkovitz Y, et al. Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation over the prefrontal cortex: evaluation of antidepressant and cognitive effects in depressive patients. Brain Stimul. 2009;2(4):188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin Y, Zhang C, Wang Y. A randomized controlled study of transcranial direct current stimulation in treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(2):403. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H, et al. Piezo1 channels as force sensors in mechanical force-related chronic inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:816149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.816149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Love JC, et al. Self-assembled monolayers of thiolates on metals as a form of nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2005;105(4):1103–1170. doi: 10.1021/cr0300789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luana L, Rego AC. Isolation and maintenance of striatal neurons. Bio-protocol. 2018;8:8. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma Z, et al. TCR triggering by pMHC ligands tethered on surfaces via poly(ethylene glycol) depends on polymer length. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madsen SJ, et al. Photodynamic therapy of newly implanted glioma cells in the rat brain. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006;38(5):540–548. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maroto R, et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(2):179–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matthews BD, et al. Ultra-rapid activation of TRPV4 ion channels by mechanical forces applied to cell surface β1 integrins. Integr. Biol. 2010;2(9):435–442. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00034e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matyas F, et al. Motor control by sensory cortex. Science. 2010;330(6008):1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1195797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meiser J, Weindl D, Hiller K. Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mejía-López J, et al. Vortex state and effect of anisotropy in sub-100-nm magnetic nanodots. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100(10):104319. doi: 10.1063/1.2364599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mejía-López J, et al. Development of vortex state in circular magnetic nanodots: theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;81(18):184417. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.184417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mendonca ME, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation combined with aerobic exercise to optimize analgesic responses in fibromyalgia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:68. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Momin A, et al. Channeling force in the brain: mechanosensitive ion channels choreograph mechanics and malignancies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021;42(5):367–384. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mora B, et al. Cost-effective design of high-magnetic moment nanostructures for biotechnological applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10(9):8165–8172. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morales R, et al. Ultradense arrays of sub-100 nm Co/CoO nanodisks for spintronics applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020;3(5):4037–4044. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.0c00052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Neil RG, Heller S. The mechanosensitive nature of TRPV channels. Pflüg. Arch. 2005;451(1):193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Papakostas GI, Ionescu DF. Towards new mechanisms: an update on therapeutics for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20(10):1142–1150. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peixoto L, et al. Magnetic nanostructures for emerging biomedical applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020;7(1):011310. doi: 10.1063/1.5121702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peng D, et al. A ZnS/CaZnOS heterojunction for efficient mechanical-to-optical energy conversion by conduction band offset. Adv. Mater. 2020;32(16):1907747. doi: 10.1002/adma.201907747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pensa E, et al. The chemistry of the sulfur-gold interface: in search of a unified model. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45(8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1021/ar200260p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perin R, Berger TK, Markram H. A synaptic organizing principle for cortical neuronal groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(13):5419–5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016051108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raij T, et al. Prefrontal Cortex Stimulation Enhances Fear Extinction Memory in Humans. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramos JI, Moya SE. Effect of the density of ATRP thiol initiators in the yield and water content of grafted-from PMETAC brushes. A study by means of QCM-D and spectroscopic ellipsometry combined in a single device. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2012;213(5):549–556. doi: 10.1002/macp.201100501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reviakine I, Johannsmann D, Richter RP. Hearing what you cannot see and visualizing what you hear: interpreting quartz crystal microbalance data from solvated interfaces. Anal. Chem. 2011;83(23):8838–8848. doi: 10.1021/ac201778h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romero G, et al. Modulating cell signalling in vivo with magnetic nanotransducers. Nat.Rev. Methods Primers. 2022;2(1):92. doi: 10.1038/s43586-022-00170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rotherham M, et al. Magnetic activation of TREK1 triggers stress signalling and regulates neuronal branching in SH-SY5Y cells. Front. Med. Technol. 2022;4:1. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.981421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarkar A, Dowker A, Cohen Kadosh R. Cognitive enhancement or cognitive cost: trait-specific outcomes of brain stimulation in the case of mathematics anxiety. J Neurosci. 2014;34(50):16605–16610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3129-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sauerbrey G. Verwendung von Schwingquarzen zur Wägung dünner Schichten und zur Mikrowägung. Zeitsch. Phys. 1959;155(2):206–222. doi: 10.1007/BF01337937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shen Y, et al. Elongated nanoparticle aggregates in cancer cells for mechanical destruction with low frequency rotating magnetic field. Theranostics. 2017;7(6):1735–1748. doi: 10.7150/thno.18352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spassova MA, et al. A common mechanism underlies stretch activation and receptor activation of TRPC6 channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(44):16586–16591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606894103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stummer W, et al. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme utilizing 5-ALA-induced porphyrins: a prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J. Neurosurg. 2000;93(6):1003–1013. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tabatabaei SN, et al. Remote control of the permeability of the blood–brain barrier by magnetic heating of nanoparticles: a proof of concept for brain drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2015;206:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trevizol AP, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. ECT. 2016;32:4. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vazana U, et al. Glutamate-mediated blood-brain barrier opening: implications for neuroprotection and drug delivery. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(29):7727–7739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vriens J, Appendino G, Nilius B. Pharmacology of vanilloid transient receptor potential cation channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75(6):1262–1279. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.055624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wilde C, et al. Translating the force—mechano-sensing GPCRs. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022;322(6):1047–1060. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00465.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu X, et al. Sono-optogenetics facilitated by a circulation-delivered rechargeable light source for minimally invasive optogenetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116(52):26332–26342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914387116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang Y, et al. Orientation mediated enhancement on magnetic hyperthermia of Fe3O4 Nanodisc. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015;25(5):812–820. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201402764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang Y, et al. Size-dependent microwave absorption properties of Fe3O4 nanodiscs. RSC Adv. 2016;6(30):25444–25448. doi: 10.1039/C5RA28035D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yoo S, et al. Electro-optical neural platform integrated with nanoplasmonic inhibition interface. ACS Nano. 2016;10(4):4274–4281. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoo S, et al. Focused ultrasound excites cortical neurons via mechanosensitive calcium accumulation and ion channel amplification. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):493. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28040-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoshimura Y, Dantzker JLM, Callaway EM. Excitatory cortical neurons form fine-scale functional networks. Nature. 2005;433(7028):868–873. doi: 10.1038/nature03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao B, et al. Quantifying tensile forces at cell-cell junctions with a DNA-based fluorescent probe. Chem. Sci. 2020;11(32):8558–8566. doi: 10.1039/D0SC01455A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.